Abstract

Background:

Early life antibiotics have been linked to childhood inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but data on adults is mixed—particularly for ulcerative colitis (UC)—and is based on smaller investigations that have not assessed risk among siblings with shared genetic/environmental risk factors. Our objective was to determine the association of antibiotic therapy and IBD in a large, population-based investigation.

Methods:

We conducted a population-based prospective case-control study of individuals aged ≥16 years in ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden), the Swedish Patient Register, and the Prescribed Drug Register to identify all consecutive cases of incident IBD (2007–2016) based on histology and ≥1 diagnosis code for IBD or its subtypes: UC and Crohn’s disease (CD). Cumulative antibiotic dispensations accrued until one year prior to the time of matching for both study cases and up to five general population controls matched on the basis of age, sex, county, and calendar year. We also included unaffected full siblings as a secondary control group. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Findings:

We identified 23,982 new IBD cases (15,951 UC, 7,898 CD, 133 IBD-unclassified), 28,732 siblings, and 117,827 controls. Prior use of antibiotics (never vs. ever) was associated with a nearly two-times increased risk of IBD after adjusting for several risk factors (aOR 1·94, 95% CI: 1·85–2·03). Compared to none, one (aOR 1·11, 95% CI: 1·07–1·15), two (aOR 1·38, 95% CI: 1·32–1·44) , and ≥three antibiotic dispensations (aOR 1·55, 95% CI: 1·49–1·61) were associated with increased odds of IBD compared to controls. Increased risk was noted for UC and CD with the highest estimates corresponding to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Notably, comparable, but attenuated results were observed when siblings served as the referent (aOR 1·35, 95% CI: 1·28–1·43).

Interpretation:

Higher cumulative exposure to systemic antibiotic therapy, particularly those with greater spectrum of microbial coverage, may be associated with an increase in risk for new-onset IBD and its subtypes. The association between antimicrobial treatment and IBD did not appear to differ when comparably predisposed siblings were used as the referent controls.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health; Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation

Keywords: colonic microflora, IBD clinical, pharmacotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Host genetics, environmental factors, and the gut microbiome are known to contribute to etiopathogenesis of IBD.1 While host genetics have been studied extensively, less clearly understood are the contributions of specific environmental determinants to an alarming rise in IBD, disproportionately affecting Europe, the U.S., and parts of the world undergoing rapid economic development.2,3 Consequently, increased sanitation and widespread use of anti-infectious agents4 have been proposed as reasons why this emerging disparity in disease burden is becoming more apparent—the so-called hygiene hypothesis. Prior large-scale efforts have demonstrated that individuals with IBD harbour greater numbers of facultative anaerobes (including Escherichia coli) and comparatively fewer obligate anaerobic producers of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) compared to individuals free of IBD.5 With growing appreciation for the richness and diversity of the gut microbiome and its role in maintaining human health, so too has concern that antibiotics may perturb and permanently alter these microbial communities, increasing risk for IBD and other disorders similarly characterized by dysregulated host/microbial interactions.

Despite expanded reliance on antimicrobial therapy being a leading suspected culprit contributing to this phenomenon, current studies are limited by small sample size,6–12 lack of histopathologic case ascertainment,6–8,10,12–17 and mainly address risk associated with paediatric IBD.13–18 Also, no studies have yet assessed whether risk related to antibiotics is modified within families already genetically predisposed to the development of IBD. Finally, careful assessment of pre-diagnostic antibiotic usage with an appropriate exclusionary/lead-in period (i.e. a period of time for which antibiotic dispensations just prior to an IBD diagnosis are not accrued) is necessary to limit the possibility of reverse causation, or therapy prescribed for symptoms related to undiagnosed IBD. This is particularly important for IBD, since the time to diagnosis may be delayed by four to nine months.19 Population-scale investigations with careful case ascertainment and an appropriate lead-in period are urgently needed to help settle this controversial and unsettled question.

Thus, to our knowledge, we conducted the single largest investigation assessing cumulative exposure to antibiotic therapy and incident IBD, conservatively assessed at least one year prior to disease diagnosis. We confirmed case status by requiring both compatible histopathology and medical diagnosis coding, using the first occurrence of either criterion as the date of diagnosis, and compared antibiotic usage for those afflicted to general population controls in a large, nationally representative case-control study. To minimize the confounding effect of childhood exposures and genetic susceptibility, we also compared IBD cases to their unaffected, full siblings.

METHODS

Study design and participants

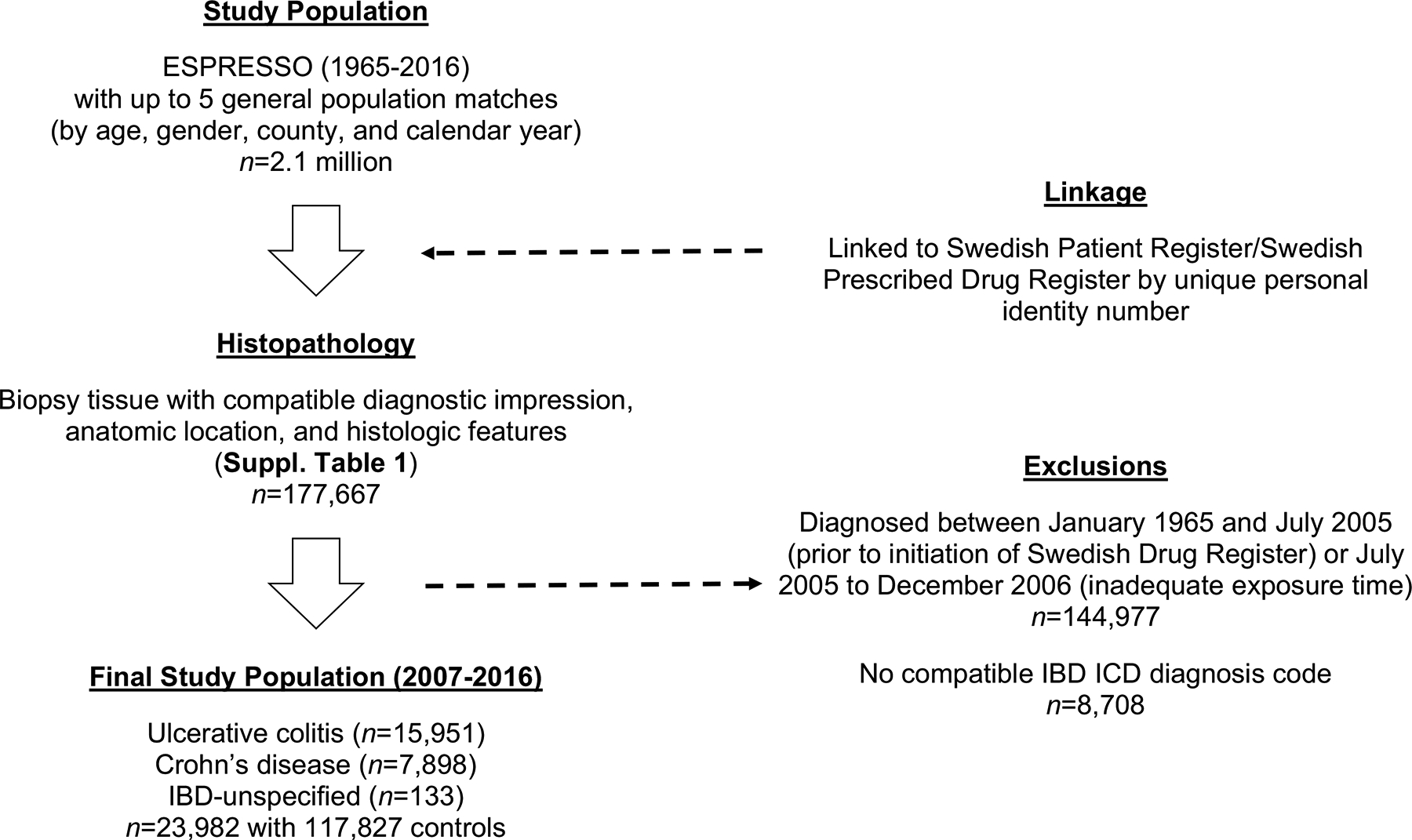

In Sweden, universal access to care is tax-funded and includes prescription medication coverage.20 The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare has collected patient-level data on hospital discharges nationally since 1987 using the Swedish Patient Register. Each patient record includes sex, date of birth, dates of hospital admission, as well as procedural and discharge diagnoses systematized by International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code (Fig. 1 and Appendix, p2). In 2001, this registry was expanded to outpatient specialty care, including visits to gastroenterology providers. The positive predictive value for most diagnoses in this register ranges between 85% and 95%.21 We further integrated this national registry data with the Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden (ESPRESSO) study.22 Briefly, the ESPRESSO study is an ongoing, comprehensive data harmonizing effort involving each of the 28 pathology laboratories in Sweden. This includes all computerized GI pathology reports generated for clinical care or research purposes between 1965 and 2016, encompassing more than 2.1 million unique individuals with detailed information on topography (i.e. the anatomic location of the obtained tissue), morphology, appearance, and the pathologist’s diagnostic impression. Finally, since July 2005, the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register has collected information on all medications, including antibiotics, prescribed to the entire Swedish population, as well as the date of redemption, amount dispensed, and dose allotted.20 Patient level data from the ESPRESSO cohort and two national registries (Patient Register and the Prescribed Drug Register) were linked by a unique personal identity number assigned at birth or at the time when permanent residence was established. Thus, our study encompasses all consecutive eligible patients for the period of overlap during which the National Patient Register, the ESPRESSO study, and the Prescribed Drug Register were each actively enrolling (July 1, 2005 to December 31, 2016). This investigation was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board (Protocol 2014/1287–31/4). Due to the strict registry-based nature of the study, informed consent was waived.

Figure 1:

Study overview

Ascertainment of outcomes

Using predefined anatomic and histologic criteria, as well as the attending pathologist’s diagnostic impression (Appendix, p2), we identified individuals in the ESPRESSO study with GI tract histopathology compatible with the diagnosis of new-onset IBD and its subtypes, UC and CD from 2005 to 2016. If a distinction between subtypes could not be made, cases were defined as (non-infectious) indeterminate colitis or IBD-unclassified (IBD-U). We then cross-referenced potential cases and the entirety of their inpatient and outpatient records in search of at least one ICD code consistent with IBD.

We first excluded those with IBD-compatible pathology or ICD diagnostic coding prior to our study baseline (2005). The date of IBD diagnosis was defined as the earliest between the date of relevant pathology findings and the first appearance of an IBD-related diagnosis code. In a random subset of individuals with both compatible histopathology and an ICD code for IBD, we were able to validate case status using manual chart review in 95 of 100 individuals22 yielding a positive predictive value of 95% (95% CI: 89–99%). To account for the possibility of reverse causation, or antibiotic therapy prescribed for symptoms related to undiagnosed IBD, we did not count antibiotic dispensations in the one year leading up to IBD diagnosis. Consequently, to conservatively ensure adequate at-risk exposure time (since antibiotics were not counted in the preceding 12 months), we excluded IBD cases diagnosed within the first 18 months of study baseline/initiation of the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (Appendix, p8).

At the time of ESPRESSO inclusion, individuals were paired with up to five reference controls from the general population, matched on the basis of age, sex, calendar year, and county. Controls with undiagnosed IBD at the time of matching were allowed to later become cases if they met the prespecified diagnostic criteria, and they were then subsequently matched to five other reference controls of their own. Additionally, to further assess the association between cumulative antibiotic usage and IBD among genetically related individuals, we also identified and enrolled unaffected full siblings of our index cases still living at the time of their siblings’ IBD diagnosis.22

Ascertainment of primary exposure and other covariates

Our primary exposure, cumulative antibiotic usage up to one year prior to IBD diagnosis, defined as the cumulative sum of antibiotic dispensations. This was assessed using the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register and categorized using established World Health Organization (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes for the therapeutic subgroup of antibacterials approved for systemic usage. To achieve adequate case balance, we collected information on number of dispensations (categorized into zero, one, two, and three or greater dispensations, corresponding with median/interquartile values for dispensations across the entire study population). We also collected information on the cumulative number of prescribed days, as well as the cumulative defined daily dose (cDDD). In secondary analyses to further define the relationship between antimicrobial coverage, dysbiosis, and risk of IBD, we assessed whether different ATC classes of antibiotics (penicillins, cephalosporins, macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, sulphonamides, and other) and spectrum of coverage (broad vs. narrow)23 influenced risk of disease (Appendix, p3).

When available, we obtained data on level of education (≤9 years, 10–12 years, ≥13 years, and unknown) from Statistics Sweden and the longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies, which since 1990 has annually updated administrative information from the labour market and educational and social sectors for all individuals aged 16 years or older. This information is available in more than 98% of all individuals aged 25–64 years.24 We also calculated the number of inpatient and outpatient encounters (continuous) for each participant during the study period up until the time of matching.

Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the association between antecedent antibiotic therapy and IBD, we performed conditional logistic regression between IBD cases and reference controls to estimate crude and multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) conditioned on matching factors (age, sex, calendar year, and county of residence) and further adjusted for potential confounding factors (education level and healthcare utilization, the latter defined as the number of inpatient and outpatient encounters during follow up). Tests for linear trend were calculated using the midpoint of each frequency category as a continuous variable. Two-sided p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

As a sensitivity analysis and to assess the robustness of our primary findings, we lengthened the lead-in period from one year in our primary analysis to a more conservative two years. We also performed subgroup analyses according to the spectrum of antibiotic coverage and class of antibiotic therapy prescribed. We conducted a joint association analysis to determine whether the number of combined broad or narrow-spectrum dispensations altered the association between antimicrobial therapy and IBD, in effect, a test of interaction between two risk factors. Finally, to minimize the influence of genetic predisposition and shared childhood exposures, we compared cases to their (unmatched) full siblings using logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, year of match, county, education level, and healthcare utilization. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.5.1 (Vienna, Austria).

Role of Funding Sources

Sponsors had no role in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, report writing, and the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

RESULTS

We identified 32,690 unique individuals aged ≥ 16 years in the ESPRESSO study with GI tract histopathology compatible with the diagnosis of new-onset IBD and its subtypes, UC and CD from 2005 to 2016. After excluding individuals with a compatible IBD ICD diagnosis code at or prior to baseline and individuals without adequate exposure time according to our prespecified lead-in period, we enrolled 23,982 cases of biopsy and diagnosis code-confirmed IBD between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2016 (15,951 UC, 7,898 CD, 133 IBD-U). Patients with IBD were comparable to their 117,827 matched controls by mean age (35 years), sex (52% male), education level, and region of residence, but tended to have more frequent engagement with inpatient and outpatient providers (Table 1 and Appendix, p5). Among these general population individuals, only 952 (0.8%) individuals would become cases themselves and were thus matched to their own reference individuals. We found a strong correlation between the presence of an IBD-compatible ICD code recorded in the inpatient setting with one in the outpatient setting (Spearman ρ for IBD, CD, and UC each > 0.62), which would suggest that either clinical setting (e.g. inpatient or outpatient) is suitable for valid case identification.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics at the time of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis and their matched general population controls, 2007–2016

| Cases n=23,982# |

Controls n=117,827 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis n=15,951 |

Crohn’s disease n=7,898 |

||

| Age, years | 36 [24–56] | 31 [19–51] | 35 [22–54] |

| <18 | 1,755 (11) | 1,686 (21) | 17,699 (15) |

| 18–24 | 2,552 (16) | 1,422 (18) | 20,421 (17) |

| 25–34 | 3,190 (20) | 1,343 (17) | 22,785 (19) |

| 35–44 | 2,233 (14) | 948 (12) | 15,843 (13) |

| 45–54 | 1,914 (12) | 790 (10) | 13,451 (12) |

| 55–64 | 2,072 (13) | 869 (11) | 13,487 (12) |

| ≥65 | 2,235 (14) | 840 (11) | 14,141 (12) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 8,543 (54) | 3,997 (51) | 62,010 (52) |

| Region of residence, n (%) | |||

| Northern Sweden | 1,417 (9) | 590 (7) | 9,926 (8) |

| Southeastern Sweden | 1,816 (11) | 923 (12) | 13,572 (12) |

| Southern Sweden | 3,030 (19) | 1,518 (19) | 22,390 (19) |

| Stockholm-Gotland | 3,071 (19) | 2,047 (26) | 25,229 (21) |

| Uppsala-Örebro | 3,489 (22) | 1,592 (20) | 25,216 (21) |

| Western Sweden | 3,026 (19) | 1,178 (15) | 20,922 (18) |

| Unknown | 102 (1) | 50 (1) | 572 (1) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| ≤9 years | 2,829 (18) | 1,540 (20) | 21,030 (18) |

| 10–12 years | 7,121 (45) | 3,473 (44) | 50,542 (43) |

| ≥13 years | 5,563 (35) | 2,430 (31) | 41,092 (35) |

| Unknown | 438 (3) | 455 (6) | 5,163 (4) |

| Number of encounters*, n | |||

| Inpatient | 2 [0–4] | 2 [0–4] | 1 [0–3] |

| Outpatient | 5 [2–11] | 6 [2–13] | 3 [1–9] |

| Calendar year | |||

| 2007–2009 | 4,786 (30) | 2,186 (28) | 34,449 (29) |

| 2010–2013 | 7,031 (44) | 3,570 (45) | 52,373 (44) |

| 2014–2016 | 4,134 (26) | 2,142 (27) | 31,005 (26) |

Values are median [IQR] or absolute figures (percentages). Polytomous variables may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and IBD-unclassified

calculated the number of inpatient and outpatient encounters (continuous) for each participant during the study period up until the time of matching/case diagnosis.

Prior use of antibiotics was associated with a nearly two-times increased risk of IBD after adjusting for several risk factors (multivariable OR 1·94, 95% CI: 1·85–2·03). Increased cumulative antibiotic use was associated with an increased risk for new-onset IBD and its two primary subtypes, UC and CD (Table 2). Inclusive of our matching criteria (age, sex, calendar year and county), education level, and number of prior inpatient and outpatient encounters, multivariable conditional logistic regression demonstrated a frequency-dependent relationship between increased antibiotic prescriptions and risk of IBD (P-trend <·0001). We found that three or more antibiotic dispensations at least one year prior to diagnosis was associated with a 55% increased risk for IBD (multivariable OR 1·55, 95% CI: 1·49–1·61) compared to no prior use. Due to significant collinearity in their measure, results were similar when cumulative antibiotic therapy was assessed by number of days prescribed or cDDD (data not shown). Risk estimates were slightly higher for CD compared to UC. Our estimates were not materially altered when a two-year, rather than one-year lead-in was employed (multivariable OR for ≥3 dispensations compared to never use 1·47, 95% CI: 1·41–1·53; P-trend<·0001). Results remained consistent when we removed controls who eventually became cases (data not shown).

Table 2.

Overall antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel disease comparing cases and their matched general population controls, 2007–2016

| Cumulative antibiotic use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No use | 1 dispensation | 2 dispensations | ≥3 dispensations | P-trend* | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)# | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 9,677 (40) | 4,813 (20) | 3,087 (13) | 6,405 (27) | |

| Controls, n (%) | 56,240 (48) | 24,864 (21) | 13,152 (11) | 23,571 (20) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI)† | 1·0 (ref) | 1·14 (1·10, 1·19) | 1·46 (1·40, 1·53) | 1·78 (1·71,1·84) | <·0001 |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI)‡ | 1·0 (ref) | 1·11 (1·07, 1·15) | 1·38 (1·32, 1·44) | 1·55 (1·49, 1·61) | <·0001 |

| Ulcerative colitis (UC) | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 6,587 (41) | 3,274 (21) | 2,004 (12) | 4,086 (26) | |

| Controls, n (%) | 37,642 (48) | 16,570 (21) | 8,656 (11) | 15,481 (20) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·16 (1·11, 1·22) | 1·39 (1·32, 1·47) | 1·63 (1·55, 1·71) | <·0001 |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·13 (1·08, 1·19) | 1·33 (1·25, 1·41) | 1·47 (1·40, 1·54) | <·0001 |

| Crohn’s disease (CD) | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 3,030 (38) | 1,521 (19) | 1,061 (14) | 2,286 (29) | |

| Controls, n (%) | 18,255 (47) | 8,152 (21) | 4,425 (11) | 7,986 (21) | |

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·18 (1·10, 1·26) | 1·56 (1·44, 1·69) | 1·94 (1·81, 2·07) | <·0001 |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·14 (1·06, 1·22) | 1·46 (1·35, 1·58) | 1·64 (1·53, 1·76) | <·0001 |

Cumulative dispensations accrued from study baseline up until one year prior to diagnosis/match

Abbreviations: OR - odds ratio, CI - confidence interval

Includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and IBD-unclassified

Conditional logistic regression matched for age, sex, calendar year, and county

Further adjusted for number of inpatient and outpatient encounters and education level

Calculated using the median of each category as a continuous variable.

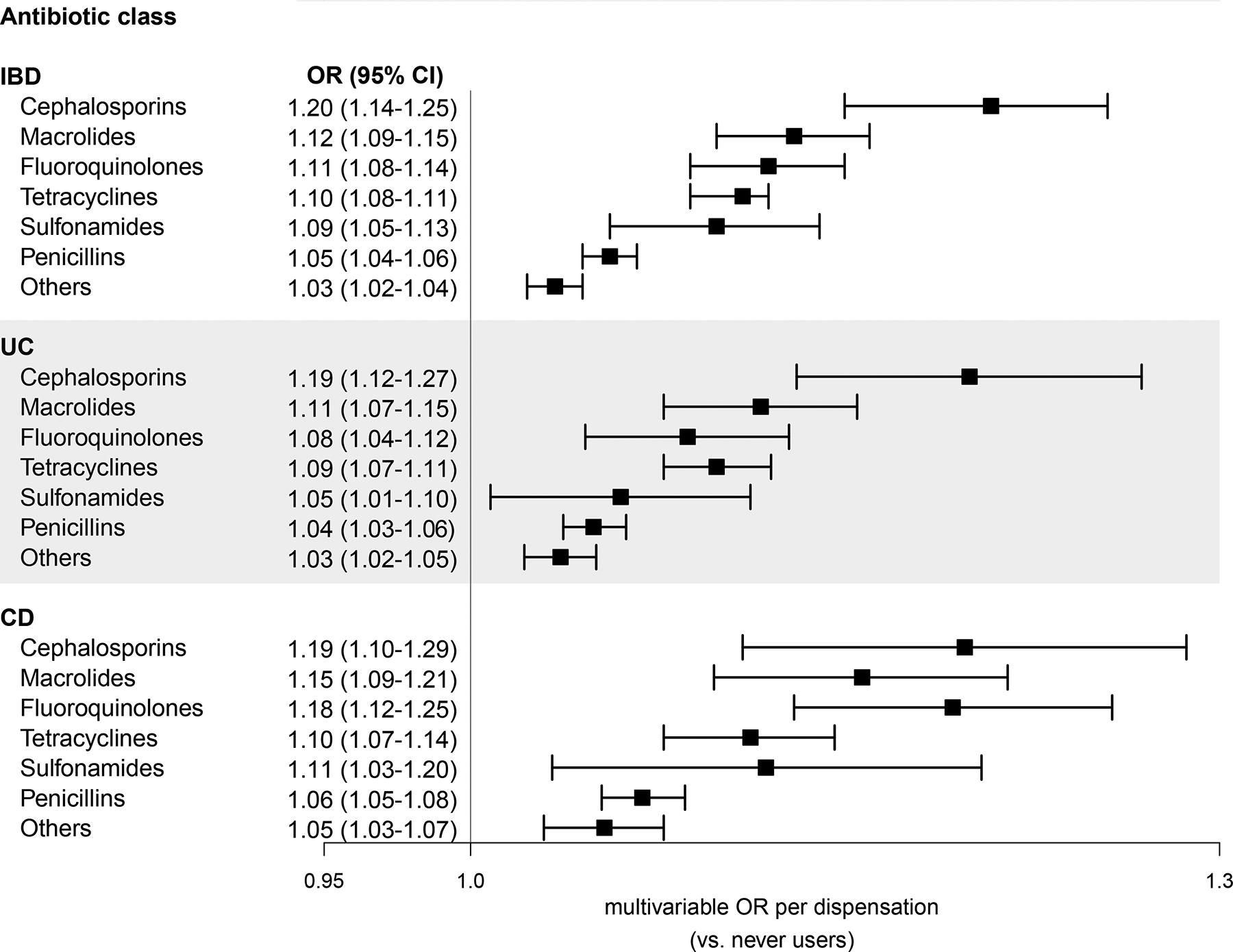

Subgroup analyses by spectrum of antibiotic coverage demonstrated an increased risk among patients reporting more frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics compared to narrow spectrum (Table 3). Heterogeneity in risk estimates appeared most pronounced for CD, though formal tests for interaction were highly significant for IBD, UC, and CD (all P-interaction <·0001). There was no clear synergistic effect between increasing frequency of combined broad and narrow-spectrum antimicrobial therapy (data not shown). Each class of antibiotic assessed, categorized by World Health Organization ATC subgroup, was associated with a statistically significant increase in risk per dispensation compared to never users (multivariable OR between 1·03–1·20; Fig. 2), highest for each dispensation of a cephalosporin class antibiotic (multivariable OR for IBD 1·20, 95% CI: 1·14–1·25). To further ensure our primary findings were not a consequence of infections related to undiagnosed IBD (i.e. confounding by indication), we compared the usage of a composite antibiotic, either ciprofloxacin or metronidazole—two commonly prescribed antibiotics for bacterial gastroenteritis—and found comparable results to our overall estimate (multivariable OR for IBD compared to never users of 1·15, 95% CI: 1·11–1·20). In general, we found consistent results between UC and CD. A stratified analysis by age group appeared to demonstrate a greater association among older individuals, perhaps suggesting that environmental exposures may play an outsized role in older onset IBD, while other factors may contribute to early-onset IBD, which tends to have a more dramatic disease course (Appendix, p6).

Table 3.

Spectrum of antibiotic coverage and inflammatory bowel disease comparing cases and their matched general population controls, 2007–2016

| Cumulative antibiotic use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No prior use | 1 prior dispensation | 2 prior dispensations | ≥3 prior dispensations | P-interaction | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)# | |||||

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | <0·0001 | ||||

| Cases, n (%) | 9,677 (57) | 3,690 (22) | 1,592 (9) | 2,040 (12) | |

| Controls, n (%) | 56,240 (66) | 16,302 (19) | 5,803 (7) | 6,620 (8) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI)‡ | 1·0 (ref) | 1·31 (1·25, 1·37) | 1·58 (1·48, 1·68) | 1·69 (1·59, 1·79) | |

| Narrow-spectrum antibiotics | |||||

| Cases n (%) | 9,677 (44) | 5,212 (24) | 2,797 (13) | 4,109 (19) | |

| Controls n (%) | 56,240 (52) | 25,023 (23) | 11,768 (11) | 15,134 (14) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·18 (1·13, 1·22) | 1·37 (1·30, 1·43) | 1·49 (1·43, 1·56) | |

| Ulcerative colitis (UC) | |||||

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | <0·0001 | ||||

| Cases n (%) | 6,587 (60) | 2,440 (21) | 1,015 (9) | 1,299 (11) | |

| Controls n (%) | 37,642 (66) | 10,934 (19) | 3,873 (7) | 4,465 (8) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·29 (1·22, 1·36) | 1·50 (1·38, 1·63) | 1·57 (1·45, 1·70) | |

| Narrow-spectrum antibiotics | |||||

| Cases n (%) | 6,587 (45) | 3,524 (24) | 1,779 (11) | 2,590 (18) | |

| Controls n (%) | 37,642 (52) | 16,571 (23) | 7,775 (11) | 9,750 (14) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·20 (1·15, 1·26) | 1·28 (1·21, 1·36) | 1·43 (1·35, 1·52) | |

| Crohn’s disease (CD) | |||||

| Broad-spectrum antibiotics | <0·0001 | ||||

| Cases n (%) | 3,030 (54) | 1,236 (22) | 587 (11) | 729 (13) | |

| Controls n (%) | 18,255 (66) | 5,277 (19) | 1,909 (7) | 2,130 (8) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·40 (1·29, 1·52) | 1·79 (1·60, 2·00) | 1·78 (1·59, 1·99) | |

| Narrow-spectrum antibiotics | |||||

| Cases n (%) | 3,030 (42) | 1,667 (23) | 1,003 (14) | 1,497 (21) | |

| Controls n (%) | 18,255 (51) | 8,310 (23) | 3,933 (11) | 5,317 (15) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·21 (1·13, 1·30) | 1·50 (1·37, 1·63) | 1·57 (1·44, 1·70) | |

Cumulative dispensations accrued from study baseline up until one year prior to diagnosis/match.

Abbreviations: OR - odds ratio, CI - confidence interval

Includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and IBD-unclassified

Conditional logistic regression matched for age, sex, and county. Referent group is no antibiotic use of any kind.

Further adjusted for number of inpatient and outpatient encounters and education level

Figure 2:

Antibiotic use by antibiotic class and inflammatory bowel disease comparing cases and their matched general population controls, 2007–2016. Conditional logistic regression matched for age, sex, and county and further adjusted for number of inpatient and outpatient encounters and education level. Referent group had no prior exposure to antibiotics of any kind at the time of matching. Cumulative dispensations accrued from study baseline up until one year prior to diagnosis/match. IBD includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and IBD-unclassified. Abbreviations: OR - odds ratio, CI - confidence interval, IBD - inflammatory bowel disease, UC - ulcerative colitis, CD - Crohn’s disease.

Finally, among individuals with a genetic predisposition to disease development and to partially account for shared but unspecified childhood exposures, we compared antimicrobial therapy rates among IBD cases and their full siblings, where available. Nearly 70% of cases (n=16,353) had at least one living sibling identified in our cohort, all of whom were captured by linkage to the National Patient Register. When comparing 28,732 full siblings free of IBD to their related cases, as expected, their mean age, region of residence, and education levels were all comparable (Appendix, p7). Notably, their number of inpatient and outpatient encounters were similarly elevated—like their case siblings—compared to unrelated reference individuals, suggesting similar childhood exposures, infections, predilection for chronic disease, and access to comparable childhood care. When siblings were used as the referent group, IBD risk estimates were only slightly attenuated compared to general population controls, with a multivariable OR of 1·35 (95%CI: 1·28–1·43; P-trend <·0001) when comparing three or greater antibiotic dispensations to none (Table 4). Estimates were comparable for both UC and CD.

Table 4:

Overall antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel disease comparing cases and their unaffected siblings, 2007–2016

| Cumulative antibiotic use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No prior use | 1 prior dispensation | 2 prior dispensations | ≥3 prior dispensations | P-trend | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)# | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 6,502 (40) | 3,407 (21) | 2,170 (13) | 4,274 (26) | |

| Siblings, n (%) | 12,688 (44) | 6,278 (22) | 3,341 (12) | 6,425 (22) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI)‡ | 1·0 (ref) | 1·06 (1·01, 1·12) | 1·32 (1·24, 1·41) | 1·35 (1·28, 1·43) | <0·0001 |

| Ulcerative colitis (UC) | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 4,428 (41) | 2,279 (21) | 1,392 (13) | 2,739 (25) | |

| Siblings, n (%) | 8,459 (45) | 4,209 (22) | 2,204 (11) | 4,160 (22) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·06 (0·99, 1·14) | 1·23 (1·13, 1·34) | 1·29 (1·20, 1·39) | <0·0001 |

| Crohn’s disease (CD) | |||||

| Cases, n (%) | 2,036 (38) | 1,117 (20) | 762 (14) | 1,514 (28) | |

| Siblings, n (%) | 4,073 (43) | 2,030 (21) | 1,111 (12) | 2,221 (24) | |

| Multivariable OR (95% CI) | 1·0 (ref) | 1·13 (1·02, 1·25) | 1·41 (1·26, 1·58) | 1·46 (1·23, 1·62) | <0·0001 |

Cumulative dispensations accrued from study baseline up until one year prior to case diagnosis.

Abbreviations: OR - odds ratio, CI - confidence interval

Includes ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and IBD-unclassified

Further adjusted for age, sex, county, number of inpatient and outpatient encounters, and education level

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study of nearly 24,000 unique IBD patients during a 10-year study period provided, we demonstrate a potential frequency-dependent relationship between the number of antibiotic dispensations and the development of UC and CD. This potential association appeared to be robust to adjustment for age, sex, level of education, and degree of healthcare utilization. Furthermore, this possible risk association appeared greater with more frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which supports the hypothesis linking greater excursions from the normal gut ecological state caused by antimicrobial therapy to elevated risk for chronic disease development.

To our knowledge, this is the largest investigation exploring the link between prior antimicrobial therapy and subsequent risk for IBD, which not only allowed for subgroup analyses that produced more confident risk estimates by WHO antibiotic class, but linked more frequent antibiotic therapy to risk of UC, a disease subtype for which prior, smaller investigations have produced mixed results. Moreover, in a secondary analysis among cases and their IBD-free siblings with whom they likely shared childhood exposures, as well as a genetic predilection for the development of IBD, we were able to show that risk associated with antibiotic use was only minimally attenuated when compared to tests against general reference individuals. This comparison among similarly predisposed persons provides further evidence to implicate cumulative antibiotic exposure as an independent risk factor in the etiopathogenesis of IBD, regardless of underlying genetic susceptibility.

Disentangling the environmental exposures that may culminate in the diagnosis of IBD is critically important, particularly as some data may suggest that risk of IBD due to antibiotics may be restricted to developed areas of the world.3 Globally, rates of IBD are rising, particularly in areas undergoing rapid economic development. Since these trends are unlikely to be explained by drastic, population-level changes in underlying genetic architecture, the widespread adoption of increased sanitation and pervasive use of anti-infectious agents have been implicated.25–28 Despite considerable progress in our understanding of IBD’s genetic and familial underpinnings, concordance rates among monozygotic, i.e. genetically identical, twins is still just 20–50%,29 highlighting the importance of considerable non-genetic determinants in new-onset IBD, such as antibiotic therapy.

Our primary findings are biologically plausible. While antibiotics have been widely beneficial for the maintenance of human health, they greatly impact the fragile ecology of human gut microbial communities, resulting in individualized and sometimes incomplete recovery from such insults, predisposing users to long-term chronic disease risk.30–33 The consequences of altering the taxonomic makeup and collective activities of the gut microbiome can influence IBD risk through several, interconnected mechanisms, including a change in vital metabolic functions, vitamin and nutrient production, as well as energy extraction. Most critically, gut microbial perturbations promote the onset of intestinal barrier dysfunction34,35, altered immune response,36,37 defective autophagy,38 and permissive pathogenic blooms39–41 that are typically viewed as inciting events as early as several years prior to the development of IBD. Notably, our group has previously linked early life antibiotic exposures to a more severe, paediatric form of the disease, adding credibility to the current findings.15

Epidemiologic evidence on the relationship between antimicrobial therapy and risk of IBD has been mounting, though it is possible that publishing bias may have resulted in comparatively fewer negative studies. The largest and most recent meta-analysis to date, encompassing 7,208 IBD patients from 11 separate investigations—cumulatively, approximately ⅓ the size of the present study—have noted similar findings with respect to antibiotic therapy and risk of CD and also observed heterogeneous risk estimates related to class of antibiotic therapy42 and included several studies in which no clear association was noted. However, Ungaro et al were unable to couple antibiotic use to an increase in risk for UC, possibly due to sample size considerations (collective number of UC patients, n= 2,935). More recently, a case-control study of 455 IBD patients by Aniwan et al demonstrated an association between antimicrobial therapy and risk of UC, albeit with much stronger risk estimates across IBD and its subtypes (adjusted OR for IBD 2.93, 95% CI: 2·40–3·58; for UC 2·94, 95% CI: 2·23–3·88).7 However, compared to our nationally representative, population-based study, they enrolled individuals from an ethnically and socioeconomically homogenous region of the U.S. Given our a priori hypothesis linking hygiene, economic development, and increased utilization of antibiotics to IBD, it is unclear how generalizable their findings may be. Additionally, Aniwan et al only excluded prescriptions in the three months prior to diagnosis, increasing the possibility of reverse causation, or therapy initiated for symptoms due to undiagnosed IBD, a disease for which the time to diagnosis may be delayed by months.19 Our study did not allow dispensations to accrue in the one year prior to IBD diagnosis/time of match, making it much less likely that antibiotics were masking symptoms of IBD that had already developed, and our estimates were not significantly attenuated when we employed an even stricter two-year lead-in period. Finally, comparable observational studies have helped elucidate the role of antibiotics in other GI conditions, such as colorectal cancer and its precursor lesions and celiac disease.

Strengths of this investigation include the enrolment of all consecutive, eligible patients with new-onset IBD from a population-based register over a ten-year study period, limiting selection bias. In Sweden, there is universal medication coverage with virtually complete information on all drug dispensations, including antibiotics, minimizing ascertainment bias (<0.3% of all prescriptions lack identifying information).43 To complement the use of a large, nationally representative sample, we employed stringent outcome ascertainment, requiring both compatible histopathologic findings and confirmatory ICD coding for adjudicating cases. With a positive predictive value of 95%, this validated method of case identification allowed us to confidently leverage and retain the power to detect even relatively modest risk increases among certain antibiotic classes, such as cephalosporins (multivariable OR 1.20 for IBD per dispensation) and penicillins (multivariable OR 1·05). Thus, we were able to demonstrate that all antimicrobial classes tested conferred additive—at times, modest—disease risk, strongly arguing for universal antibiotic stewardship and prescriber restraint.

We acknowledge several limitations. As with all large-scale pharmacoepidemiologic studies, medication dispensation ascertained through the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register may not capture any given patient’s actual usage. However, due to the short-term nature of most antibiotic courses and the presumption that most dispensations were attributable to positive symptoms suggestive of an infection, adherence was not likely a major issue. Furthermore, such bias would have resulted in attenuation towards the null from non-differential misclassification. The Prescribed Drug Register does not contain information on hospital administered drugs, though this could be partially accounted for in our multivariable models adjusting for number of hospitalizations over the follow-up period. Given the observational nature and epidemiologic scale of this investigation, the possibility of unmeasured confounding remains, and our case-control design did not allow estimates of incidence rates and absolute risks. Our results will need to be validated in other populations given Sweden’s elevated rates of IBD2,44,45 and lower antibiotic dispensation patterns compared to other nations.46,47 We did not have information on the type of infection/indication for antibiotics dispensed. We found a low rate of IBD-U during the study period, which may be a function of improved histopathologic criteria,48,49 our focus on adult-onset IBD,50,51 and a prolonged lead-in period which may not have allowed IBD-U to develop from presumed UC or CD cases.48,51 Finally, we cannot fully eliminate the possibility of reverse causation (therapy initiated for undiagnosed IBD) or confounding by indication (therapy initiated for GI infections related to IBD), though we attempted to minimize this in several ways. First, by only accounting for prescriptions at least one year prior to diagnosis, we can be more confident that antibiotic dispensations were not likely to be prescribed for undiagnosed IBD, a disease with a typical time to diagnosis between four and nine months.19 An even more stringent sensitivity analysis extended the lead-in period to two years, which demonstrated similar findings. We also demonstrated a consistent frequency-response relationship in our primary analysis and a secondary analysis for an elevated risk for broad-spectrum antibiotics that are more likely to adversely impact gut microbial communities. Lastly, we used an early, conservative date of diagnosis (at the time of either the earliest IBD-compatible histopathology or ICD coding) which minimizes the time period for which antibiotic dispensations could be attributable to symptoms of IBD.

In closing, we found that higher cumulative exposure to systemic antibiotic therapy in the past 10 years, particularly those with greater spectrum of microbial coverage, was associated with an increase in risk for new-onset IBD and its two main subtypes, UC and CD. The relationship between antimicrobial treatment and IBD was not materially altered when comparably predisposed siblings were used as the referent controls. Further studies are needed to investigate how antibiotics may permanently alter gut microbial communities, potentially culminating in disease development, and whether that risk may be reduced by probiotics to prevent expansive blooms of pathogenic bacteria in place of beneficial microbes affected by antibiotic treatment.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

Rates of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are increasing, particularly in Europe, the U.S., and other parts of the world undergoing rapid economic development, increased sanitation, and more frequent use of antibiotics. With growing appreciation for the gut microbiome’s role in maintaining human health, so too has concern that antibiotics may perturb and permanently alter these fragile microbial communities. We searched PubMed for articles published between January 1, 1990 and April 30, 2020, using the terms “inflammatory bowel disease” and “antibiotics”. Despite this compelling rationale, prior efforts to address this question have been conflicting—particularly in ulcerative colitis—and have been characterized by smaller-scale investigations with the most recent meta-analysis on the topic (with 11 prior studies and 7,208 IBD cases) disclosing a pooled odds ratio (OR) of 1.57 for risk of IBD, 1.74 for risk of Crohn’s disease, and was not significantly different for ulcerative colitis (OR 1.08; Ungaro et al, Am J Gastroenterol 2014). Thus, it remains controversial and unsettled as to whether or not antibiotic therapy is linked to new-onset IBD.

Added value of this study

Among 23,982 individuals with IBD matched to 117,827 controls, number of antibiotic dispensations was significantly associated with risk for both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in a frequency-dependent fashion. Risk appeared greater with more frequent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The positive association between antibiotic therapy and IBD remained observable even when cases were compared to their unaffected siblings with whom they likely shared genetic susceptibilities and childhood exposures, offering further support for the potential, independent role of antibiotics in IBD development.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings, if confirmed in longer-term prospective studies in humans or mechanistic pre-clinical investigations, suggest the need to further emphasize antibiotic stewardship to prevent the rise in dysbiosis-related chronic diseases, including IBD.

Funding & Grant Support:

National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants T32CA009001 (LHN), Loan Repayment Program (LHN), K07CA218377 (YC), R00CA215314 (MS); Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Research Fellowship Award (LHN) and Senior Investigator Award (ATC, HK); the American Gastroenterological Association Research Scholars Award (LHN), and the Massachusetts General Hospital Stuart and Suzanne Steele Research Scholars Award (ATC). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data, manuscript writing, or decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data and the final responsibility to submit for publication.

Declaration of Interests:

KS reports grants from AstraZeneca, Gelesis, and Takeda, personal fees from Shire, Boston Pharmaceuticals, and Arena, all unrelated to the scope of the submitted work. HK received unrelated grant funding and consulting fees from Pfizer and Takeda. JFL coordinates a separate study on behalf of the Swedish IBD quality register (SWIBREG).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12(4): 205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet (London, England) 2018; 390(10114): 2769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko Y, Kariyawasam V, Karnib M, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Environmental Risk Factors: A Population-Based Case-Control Study of Middle Eastern Migration to Australia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13(8): 1453–63 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein EY, Van Boeckel TP, Martinez EM, et al. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(15): E3463–E70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 2019; 569(7758): 655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Card T, Logan RF, Rodrigues LC, Wheeler JG. Antibiotic use and the development of Crohn’s disease. Gut 2004; 53(2): 246–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aniwan S, Tremaine WJ, Raffals LE, Kane SV, Loftus EV Jr. Antibiotic Use and New-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota: A Population-Based Case-Control Study. J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12(2): 137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN. Association between the use of antibiotics and new diagnoses of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(12): 2133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gearry RB, Richardson AK, Frampton CM, Dodgshun AJ, Barclay ML. Population-based cases control study of inflammatory bowel disease risk factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25(2): 325–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margolis DJ, Fanelli M, Hoffstad O, Lewis JD. Potential association between the oral tetracycline class of antimicrobials used to treat acne and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105(12): 2610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castiglione F, Diaferia M, Morace F, et al. Risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases according to the “hygiene hypothesis”: a case-control, multi-centre, prospective study in Southern Italy. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(3): 324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han DY, Fraser AG, Dryland P, Ferguson LR. Environmental factors in the development of chronic inflammation: a case-control study on risk factors for Crohn’s disease within New Zealand. Mutat Res 2010; 690(1–2): 116–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw SY, Blanchard JF, Bernstein CN. Association between the use of antibiotics in the first year of life and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105(12): 2687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virta L, Auvinen A, Helenius H, Huovinen P, Kolho KL. Association of repeated exposure to antibiotics with the development of pediatric Crohn’s disease--a nationwide, register-based finnish case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 175(8): 775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortqvist AK, Lundholm C, Halfvarson J, Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C. Fetal and early life antibiotics exposure and very early onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gut 2019; 68(2): 218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kronman MP, Zaoutis TE, Haynes K, Feng R, Coffin SE. Antibiotic Exposure and IBD Development Among Children: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Pediatrics 2012; 130(4): e794–e803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Troelsen FS, Jick S. Antibiotic Use in Childhood and Adolescence and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-Control Study in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hviid A, Svanstrom H, Frisch M. Antibiotic use and inflammatory bowel diseases in childhood. Gut 2011; 60(1): 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, et al. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18(3): 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wettergren B, Blennow M, Hjern A, Soder O, Ludvigsson JF. Child Health Systems in Sweden. J Pediatr 2016; 177S: S187–S202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludvigsson JF, Lashkariani M. Cohort profile: ESPRESSO (Epidemiology Strengthened by histoPathology Reports in Sweden). Clin Epidemiol 2019; 11: 101–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Haines C, Watson AJM, et al. Oral antibiotic use and risk of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom, 1989–2012: a matched case-control study. Gut 2019; 68(11): 1971–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olen O, Bruze G, Neovius M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019; 34(4): 423–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106(4): 563–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2015; 12: 205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kaplan GG, Ng SC. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017; 152(2): 313–21.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halfvarson J, Bodin L, Tysk C, Lindberg E, Jarnerot G. Inflammatory bowel disease in a Swedish twin cohort: a long-term follow-up of concordance and clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology 2003; 124(7): 1767–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108 Suppl 1: 4554–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palleja A, Mikkelsen KH, Forslund SK, et al. Recovery of gut microbiota of healthy adults following antibiotic exposure. Nature microbiology 2018; 3(11): 1255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langdon A, Crook N, Dantas G. The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med 2016; 8(1): 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrer M, Mendez-Garcia C, Rojo D, Barbas C, Moya A. Antibiotic use and microbiome function. Biochem Pharmacol 2017; 134: 114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 2016; 167(5): 1339–53 e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knoop KA, McDonald KG, Kulkarni DH, Newberry RD. Antibiotics promote inflammation through the translocation of native commensal colonic bacteria. Gut 2016; 65(7): 1100–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lochhead P, Khalili H, Ananthakrishnan AN, Richter JM, Chan AT. Association Between Circulating Levels of C-Reactive Protein and Interleukin-6 and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016; 14(6): 818–24.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Schaik FDM, Oldenburg B, Hart AR, et al. Serological markers predict inflammatory bowel disease years before the diagnosis. Gut 2013; 62(5): 683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Khider F, McDonald C. Links of Autophagy Dysfunction to Inflammatory Bowel Disease Onset. Digestive diseases 2016; 34(1–2): 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chavez F, et al. Microbiota-activated PPAR-gamma signaling inhibits dysbiotic Enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science 2017; 357(6351): 570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Becattini S, Littmann ER, Carter RA, et al. Commensal microbes provide first line defense against Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Exp Med 2017; 214(7): 1973–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rivera-Chavez F, Zhang LF, Faber F, et al. Depletion of Butyrate-Producing Clostridia from the Gut Microbiota Drives an Aerobic Luminal Expansion of Salmonella. Cell Host Microbe 2016; 19(4): 443–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ungaro R, Bernstein CN, Gearry R, et al. Antibiotics associated with increased risk of new-onset Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(11): 1728–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register--opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16(7): 726–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busch K, Ludvigsson JF, Ekstrom-Smedby K, Ekbom A, Askling J, Neovius M. Nationwide prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a population-based register study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39(1): 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Everhov AH, Halfvarson J, Myrelid P, et al. Incidence and Treatment of Patients Diagnosed With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases at 60 Years or Older in Sweden. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(3): 518–28 e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.CDC. Antibiotic Use in the United States, 2018 Update: Progress and Opportunities. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/pdf/stewardship-report-2018-508.pdf (accessed 5/1/2020 2020).

- 47.WHO. WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption: 2016–2018 early implementation. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277359/9789241514880-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 5/1/2020 2020).

- 48.Guindi M, Riddell RH. Indeterminate colitis. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57(12): 1233–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansoor E, Jin-Dominguez F, Cheema T, et al. Epidemiology of Indeterminate Colitis in the United States Between 2014 and 2019: A Population-Based National Study: 2922. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2019; 114. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prenzel F, Uhlig HH. Frequency of indeterminate colitis in children and adults with IBD — a metaanalysis. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis 2009; 3(4): 277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boruta MKR, Grand RJ, Kappelman MD. Natural History of Indeterminate Colitis. In: Mamula P, Markowitz JE, Baldassano RN, eds. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.