Abstract

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been used in a wide range of applications in the production of gene-edited animals and plants. Most efforts to insert genes have relied on homology-directed repair (HDR)-mediated integration, but this strategy remains inefficient for the production of gene-edited livestock, especially monotocous species such as cattle. Although efforts have been made to improve HDR efficiency, other strategies have also been proposed to circumvent these challenges. Here we demonstrate that a homology-mediated end-joining (HMEJ)-based method can be used to create gene-edited cattle that displays precise integration of a functional gene at the ROSA26 locus. We found that the HMEJ-based method increased the knock-in efficiency of reporter genes by eightfold relative to the traditional HDR-based method in bovine fetal fibroblasts. Moreover, we identified the bovine homology of the mouse Rosa26 locus that is an accepted genomic safe harbor and produced three live-born gene-edited cattle with higher rates of pregnancy and birth, compared with previous work. These gene-edited cattle exhibited predictable expression of the functional gene natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1 (NRAMP1), a metal ion transporter that should and, in our experiments does, increase resistance to bovine tuberculosis, one of the most detrimental zoonotic diseases. This research contributes to the establishment of a safe and efficient genome editing system and provides insights for gene-edited animal breeding.

Keywords: homology-mediated end joining (HMEJ), genomic safe harbors (GSHs), gene transfer, ROSA26, CRISPR/Cas9, infectious disease, tuberculosis, mammal, livestock

Abbreviations: BFFs, bovine fetal fibroblasts; bROSA26, bovine ROSA26; CB, cytochalasin B; COCs, cumulus–oocyte complexes; Cre, Cre recombinase; DSBs, double-strand breaks; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; GSHs, genomic safe harbors; HDR, homology-directed repair; HMEJ, homology-mediated end joining; KI, knock-in; HAs, homology arms; HR, homologous recombination; indels, inserts and/or deletions; MMEJ, microhomology-mediated end-joining; NHEJ, nonhomologous end-joining; NRAMP1, natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1; qPCR, quantitative real-time PCR; MDMs, monocyte-derived macrophages; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate dehydrogenase; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; SA, splice acceptor; SCNT, somatic cell nuclear transfer

Gene-edited livestock that relied on site-specific engineered endonucleases, especially, CRISPR/Cas9, has become an important resource for animal breeding and biomedical research (1, 2, 3, 4). A considerable part of the applications for the enhancement of disease resistance and the production of biomedical materials rely on functional gene knock-in (KI) (5, 6). Safe and efficient insertion and expression of functional gene are crucial for the practical application of genome editing technology in livestock.

CRISPR/Cas9-triggered DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) at target sites (7) can be typically repaired by nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway and the competing homologous recombination (HR) pathway (8). Moreover, microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) pathway has also been reported to be an alternative NHEJ pathway to repair DSBs (9, 10). In general, NHEJ repair pathway introducing small inserts and/or deletions (indels) at the DSB sites is often applied to endogenous gene knockout, while HR repair pathway contributes to the integration of exogenous DNA fragments flanked by homology arms (HAs) into host genome. However, since the HR pathway is mainly restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and has a lower frequency than NHEJ pathway (11, 12), the inefficiency of homology-directed repair HDR-mediated precise integration of a large DNA fragment limits the generation of gene-edited livestock. Currently, most studies have focused on enhancing the efficiency of HDR, such as optimizing parameters for targeting constructs (13), suppressing NHEJ repair pathway (14), or enhancing HR repair pathway (15). However, the efficiency of HDR remains low and its increase is only available for certain cell types. Three accessible strategies, HMEJ-, NHEJ-, and MMEJ-based methods, were proposed to mediate efficient exogenous gene KI at the expected locus in human cells (16, 17), mouse cells (18), monkey embryos (19, 20), and model organisms (21, 22, 23). By comparing the gene integration efficiency between the HDR-, HMEJ-, NHEJ-, and MMEJ-based methods, interestingly, different results were observed in different cell types or species (16, 20). To date, apart from the HDR-based method, it still remains unclear whether the other three methods can be employed to mediate high-efficiency KI in livestock.

Genomic safe harbors (GSHs) are intragenic or extragenic regions of the genome permitting sufficient expression of the inserted genes without adverse effects on the host cell or organism (24, 25). They are preferred genomic acceptor sites for genome editing. ROSA26 locus, an accepted GSH in mouse, has been targeted for the exogenous gene addition in human cells (26) and in mouse (27), rat (28), rabbit (29) and even sheep (30), and pig (31). It is ubiquitously expressed in adult tissues of above species and supports efficient integration of target sequences. Gene-edited cells and individuals showed strong and ubiquitous expression of inserted genes without apparent defects. Furthermore, the bovine ROSA26 (bROSA26) locus has been already identified and its locus tagged with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) using TALENs (32). However, major previous studies focused on insertion of reporter genes instead of functional genes.

Bovine tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis) is one of the most detrimental zoonotic diseases (33, 34), which leads to serious threat to global public health and agriculture (35). At present, the disease remains widespread and is not effectively controlled or eliminated in some less developed areas (36). We have reported Cas9 nuclease-mediated NRAMP1 gene KI cattle. The overexpression of bovine NRAMP1 gene provides the gene-edited cattle with increased resistance to tuberculosis (2). However, the low rates of pregnancy and birth limited the mass production of gene-edited cattle. In this study, we firstly identified bROSA26 locus and the optimal promoter that supported selected markers expression in bovine fetal fibroblasts (BFFs) for screening targeted colonies to perform somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Then we detected that the HMEJ-based method facilitated DNA integration and showed higher efficiency than the HDR-, MMEJ-, NHEJ-based methods in BFFs. Using the HMEJ-based method, we targeted to the bROSA26 locus to stimulate functional NRAMP1 gene KI and ultimately more effectively produced gene-edited cattle. These gene-edited cattle showed predictable expression and the ability to respond to M. bovis infection without off-target modification at potential off-target sites and without disturbance to nearby endogenous genes. Therefore, bROSA26 locus was identified as a potential GSH, allowing efficient HMEJ-based insertion of functional genes to produce cattle with increased resistance to tuberculosis, which will greatly accelerate the efficient production of gene-edited livestock.

Results

Identification of bROSA26 locus

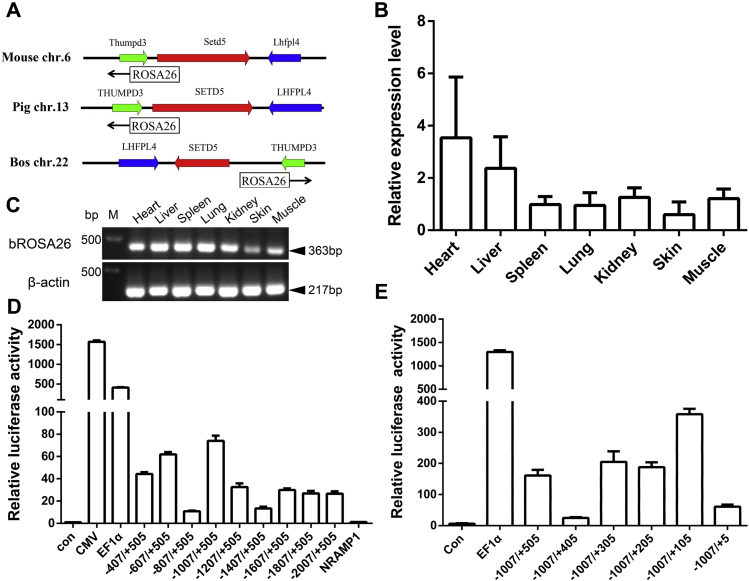

Mouse, human, rat, porcine, sheep, and rabbit data indicate that Rosa26 promoter region and exon 1 contained highly conserved sequences (29, 30, 31). The sequence of exon 1 of mouse Rosa26 transcript variant 2 plus putative promoter region was blasted against Bos taurus reference genomic sequence (taxid: 9913) in NCBI database, a highly conserved region (the highest degree of sequence similarity >84%) on bovine chromosome 22 was identified (Fig. S1). The sequence alignments of porcine ROSA26 promoter (1 kb upstream of exon 1) and exon 1 showed high sequence conservation (the highest degree of sequence similarity >92%) (Fig. S1). Sequences flanking this region contain the same genes to those in the Rosa26 locus of mouse and porcine (Lhfpl4, Setd5, and Thumpd3, Fig. 1A). We predicted the sequence of bROSA26 exon 1 from mouse Rosa26 exon 1 and designed a primer to perform 3ʹ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) analysis. One noncoding RNA product of at least 853 bp transcribed from the bROSA26 locus was identified (Fig. S2). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis reaction for exon 1 and exon 2 demonstrated that the noncoding RNA was expressed in various adult tissues (Fig. 1B). Similar expression patterns were observed using oligonucleotides that amplify a 363 bp product across the intron between exon 1 and exon 2 in a conventional RT-PCR reaction (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Identification, expression, and optimal promoter of the bovine ROSA26 (bROSA26) locus.A, schematic layout of the locations of mouse, pig, and bovine ROSA26 locus and the neighboring genes. Expression of bROSA26 gene in different adult tissues by qPCR (B) and RT-PCR (C). Bovine β-actin served as a control. Luciferase assays were performed to test the transcriptional activity of the ROSA26 promoters with different lengths of upstream sequence (−2007 to −407 bp) (D) and downstream sequence (+5 bp to +505 bp) (E). ROSA26 promoters with different lengths and internal reference vector were transfected into BFFs for 36 h. The relative luciferase activity was calculated by standardizing transfection efficiency. The CMV and EF1α promoters served as positive controls. Error bars represent the mean ± SD. Con, control; M, marker.

Identification of the optimal promoter of bROSA26 gene

Figure S1 shows high sequence conservation of Rosa26 promoter region among mouse, bovine, and pig. Mouse and pig share the same 5ʹ start of the Rosa26 transcript. Therefore, we assumed the corresponding site as the 5ʹ start of the bROSA26 transcript. Firstly, we amplified the proximal sequence from 2007 bp upstream to 505 bp downstream (relative to the putative start) using Holstein cattle genomic DNA as template. Then a series of eight reporter constructs with progressively larger deletions from the 5ʹ end of the promoter were generated. The effects of these modifications were evaluated upon transfection of the corresponding luciferase reporter plasmids into BFFs, and the results of these analyses were shown in Figure 1D. Luciferase assays revealed that pGL4.10-1007/+505 showed the highest transcriptional activity but lower than two common strong promoters (pGL4.10-CMV and pGL4.10-EF1α) (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, five reporter constructs with progressively larger deletions from the 3ʹ end of the promoter were generated. We observed that pGL4.10-1007/+105 showed the highest promoter activities (Fig. 1E). Taken together, these results indicated that the region from –1007 to +105 relative to the putative TSS acts as an optimal promoter with a moderate level for endogenous gene expression.

BROSA26 endogenous promoter-driven reporter genes expression in BFFs

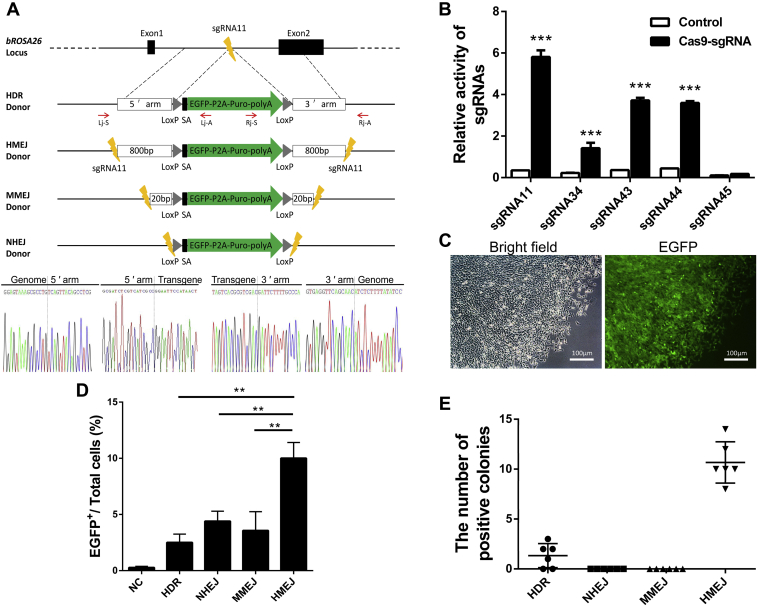

According to the result of 3ʹ RACE analysis, we designed five sgRNAs specific to the bROSA26 locus intron 1 (1512-bp) region between exon 1 and exon 2 on chromosome 22 (Fig. 2A). We constructed five SSA reporter plasmids containing designed target sites and five Cas9 expression plasmids containing 20-nt guide sequence and then cotransfected the corresponding SSA reporter plasmids and Cas9 expression plasmids into 293T cells. The activity of sgRNAs was screened with the luciferase assay as previously described (37). All the sgRNAs except the sgRNA 45 showed extremely significant activity and the sgRNA 11 showed the highest activity (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we chose target site 11 to achieve the insertion of the exogenous gene in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

BROSA26 endogenous promoter-driven reporter gene expression in BFFs.A, schematic overview of HDR-, HMEJ-, MMEJ-, and NHEJ-based gene targeting methods at the bROSA26 locus. 5ʹ arm/3ʹ arm, left/right homology arm; lightnings, sgRNA target sites; Lj-S/Lj-A, 5ʹ junction PCR forward/reverse primer; Rj-S/Rj-A, 3ʹ junction PCR forward/reverse primer; Black rectangles, splice acceptor. Gray triangles, LoxP site. Sanger sequencing confirming the precise insertion of the exogenous DNA. B, the activity of sgRNAs was measured by luciferase assay. SSA reporter plasmid, internal reference vector, and Cas9 expression plasmids containing 20-nt guide sequence or not containing (control) were transfected into 293T cells for 48 h. The relative luciferase activity was calculated by standardizing transfection efficiency. C, stably transfected BFFs by the HDR-based method after puromycin selection 10–12 days under a fluorescence microscope. D, comparison of the integration efficiency of the HDR-, HMEJ-, MMEJ-, and NHEJ-based methods. Each of the four types of donors, respectively, with Cas9/sgRNA11 were transfected into BFFs for 7 days, expanded, and subjected to FACS. Nontransfected cells were used for negative controls (NC). E, distribution of different KI patterns by four types of donors. BFFs were transfected with donors and Cas9/sgRNA via electroporation, and then the transfected colonies were counted following 10–12 days of puromycin selection. Positive colonies of the HDR groups (1.333 ± 1.211) and the HMEJ groups (10.67 ± 2.066) were confirmed by 5ʹ and 3ʹ junction PCR and sequence analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Student's t-test was used to evaluate the differences. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Given this broad expression of Rosa26 in adult tissues and the moderate activity of endogenous promoter, we were next interested in determining whether this locus could be targeted for selection of individual colonies. To evaluate whether bovine endogenous ROSA26 promoter can drive reporter genes expression in BFFs, a reporter vector pROSA26-SA-EGFP-Puro-HDR, expressing selected markers, was constructed as shown in Figures 2A and S3A. The vector contains a 5ʹ arm and a 3ʹ arm of homology, which together span 1578 bp of the bROSA26 locus. The vector overlaps with sequences of the intron 1 and the exon 2 of the bROSA26 locus. A splice acceptor (SA) sequence and a promoterless selected markers cassette separate the HAs and two LoxP sites. The selected markers cassette consists of the EGFP and puromycin resistance gene, which were fused by the porcine teschovirus-1 2A peptide sequence. The transcription of the selected markers was expected to mimic that of endogenous ROSA26 by SA sequence. The LoxP sites are positioned such that after expression of Cre recombinase (Cre), the selected markers cassette is removed after subsequent exogenous gene target for the production of marker-free gene-edited cattle.

Plasmids encoding Cas9 protein, Cas9/sgRNA11, were cotransfected with pROSA26-SA-EGFP-Puro-HDR (Fig. S3A) into BFFs to achieve stable genetic modification of cells that were targeted to bROSA26 locus through HDR. After screening with puromycin, drug-resistant colonies (Fig. 2C) were picked and analyzed by 5ʹ junction PCR for evidence of correct targeting (Fig. S3B). To rule out potential false-positives, we performed 3ʹ junction PCR on genomic DNA from 5ʹ junction PCR-positive colonies (Fig. S3B). Sequence analysis of the resulting 1824-bp (left homology arm) and 2833-bp (right homology arm) fragments of 5ʹ and 3ʹ junction PCR confirmed site-specific integration of the targeting vector into the bROSA26 locus (Fig. 3A). These results clearly demonstrated the ability of the endogenous bROSA26 promoter to drive the reporter genes expression for selecting individual colonies in BFFs.

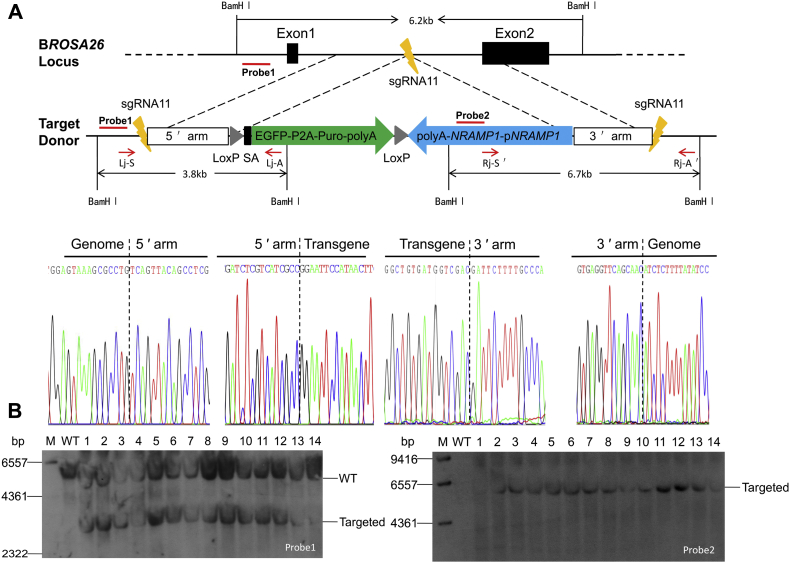

Figure 3.

HMEJ-mediated site-specific NRAMP1 insertion at bROSA26 locus.A, schematic overview of the screening of the individual colonies. Lj-S/Lj-A, 5ʹ junction PCR primer; Rj-Sʹ/Rj-Aʹ, 3ʹ junction PCR primer. Southern blot probes are shown as red lines and BamH I digestion was used in the southern blot analyses. Sanger sequencing confirming the precise insertion of the exogenous DNA. B, southern blot analyses of the donor cells used for SCNT. “WT” represents wild-type cells (nontransfected BFFs). A 3.8 kb band resulting from the targeted insertion of the NRAMP1 cassette was detected in addition to the 6.2 kb band from the endogenous ROSA26 locus allele when probe 1 was used. A 6.7 kb targeted band was also detected with probe 2. M, marker.

Optimization of strategies to target bROSA26 locus

Efficient KI of exogenous DNA is the key to generating a sufficient number of targeted colonies for SCNT. To test the feasibility and efficiency of HMEJ-, NHEJ-, or MMEJ-based methods in cattle, we constructed another three types of donors: an HMEJ donor (sgRNA target sites plus long ∼800 bp HAs), an MMEJ donor (sgRNA target sites plus short ∼20 bp HAs), and an NHEJ donor (only sgRNA target sites) (Fig. 2A). These donors can be cleaved at the sgRNA11 target site by Cas9/sgRNA11, which would cleave both genome and donor plasmid, to provide linear templates carrying HAs. At 7 days after cotransfecting each of the four types of donors, respectively, with Cas9/sgRNA11 in BFFs, we detected that the KI efficiency of the HMEJ-based method was significantly higher than that of the other methods by FACS (Fig. 2D).

To further clarify whether the HMEJ-based method facilitated DNA integration at a higher efficiency than other three strategies, we cotransfected each of the four types of donors, respectively, with Cas9/sgRNA11 into BFFs. Stably transfected colonies were identified following 10–12 days of puromycin selection. The HMEJ-based method had an approximate eightfold increase in the number of target colonies compared with the HDR-based method (Fig. 2E). Junction PCR and sequencing confirmed the correct joining between genome and donor plasmids in HMEJ and HDR groups (Figs. 2A and S4). These results suggested that the HMEJ-based method, which simultaneously introduced DSBs in genome and donors, was also able to induce precise integration of reporter genes at target sites in BFFs and showed the higher KI efficiency, compared with the HDR-based method. However, no target colonies were observed in NHEJ groups and MMEJ groups (Fig. 2E), which suggested that the NHEJ-based method and the MMEJ-based method may be inefficient for precise integration of reporter genes at bROSA26 locus in BFFs. Collectively, these data were consistent with the results observed by FACS analyses, and they clearly showed that HMEJ-based method was a highly desirable strategy for efficient KI of exogenous DNA.

HMEJ-mediated site-specific NRAMP1 insertion at bROSA26 locus

We constructed the gene-targeting vector, pROSA26-SA-EGFP-Puro-HMEJ-NRAMP1, by inserting the NRAMP1 gene and its original promoter sequence into pROSA26-SA-EGFP-Puro-HMEJ, directing NRAMP1 expression only in bovine macrophages and other dedicated phagocytes, as previously described (38). Subsequently, we introduced this targeting vector along with Cas9/sgRNA11 into BFFs and achieved the insertion of NRAMP1 gene (Fig. 3A).

Stably transfected cells (Fig. S5A), after selection with puromycin, were screened by 5ʹ -junction (1.824-bp) PCR, 3ʹ -junction (2261-bp) PCR and sequence analysis to confirm that gene-edited cassette was inserted into the intended specific site (Fig. S5, B and C and Fig. 3A). Then these targeted colonies were used for Southern blot analyses to further evaluate the insertion of gene-edited cassette. As expected, the integration of a single copy of the exogenous gene was confirmed by using an external of the genome homology region probe1 by showing a 6.2-kb band from the endogenous ROSA26 allele and a 3.8-kb band characteristic of the insertion (Fig. 3B). None of these targeted colonies showed random integration of the exogenous gene by the appearance of an expected single 6.7-kb band by using a probe specific for the NRAMP1 gene (Fig. 3B).

Somatic cell nuclear transfer to produce gene-edited cattle

SCNT was carried out to reconstruct bovine embryos by using the randomly picked seven heterozygous targeted colonies (Table 1). Then embryos were successfully reconstructed, and some reconstructed embryos were developed to blastocyst stage. Gene-edited blastocysts were transferred into the oviducts of 34 recipient heifers. Eleven (32.3%) surrogates were confirmed pregnant by ultrasound examination 1 month after the embryo transfer. Finally, three live calves were produced (Fig. 4A). For Cas9 nuclease-mediated KI cattle, HMEJ-based safe-harbor genome editing led to a dramatic increase in the rates of pregnancy and birth (32.3% and 8.8%), as compared with previous studies (12.7% and 2.3%) (2).

Table 1.

Animal production statistics

| Cell line | Embryos/recipients | Pregnant at day 30 | Pregnant at day 90 | Liveborn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0818 | 5/5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 0828 | 2/2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1123 | 4/4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1915 | 3/3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1932 | 3/3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2379 | 12/12 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 23121 | 5/5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 34/34 | 11/34 (32.3%) | 3/34 (8.8%) | 3/34 (8.8%) |

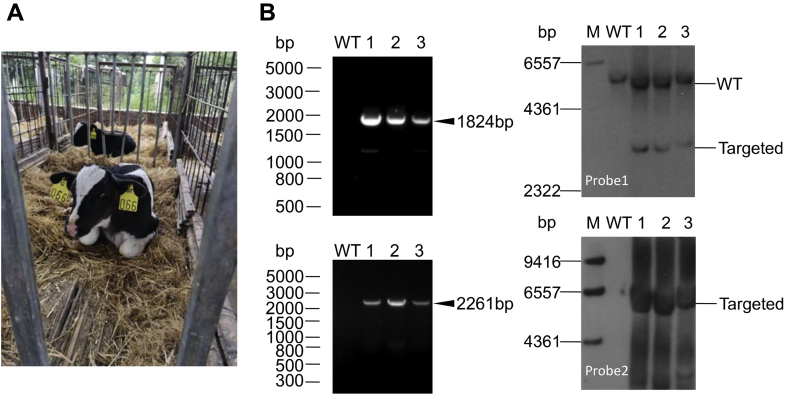

Figure 4.

Assessment of gene-edited cattle.A, photographs of a gene-edited calve that carried the NRAMP1 insertion. B, the 5′ (left, 1824-bp) (top) and 3′ junction (right, 2261-bp) (bottom) PCR analyses confirming the site-specific targeting in the gene-edited cattle. The templates for PCR were genomic DNA samples that were extracted from the tissues of cattle. C, southern blot analyses of the genomic DNA extracted from gene-edited cattle. “WT” represents wild-type cattle. M, marker.

To determine whether the exogenous NRAMP1 gene was precisely integrated at the target site, we performed 5ʹ junction PCR, 3ʹ junction PCR and Southern blot analyses to check the three gene-targeted calves. As expected, the gene-edited cattle were heterozygous for site-specific NRAMP1 KI at the target site (Fig. 4, B and C). Subsequently, we cloned eight main sgRNA11 potential off-target sites that were predicted based on sequence similarity to the target sequence from all gene-edited cattle genome. We did not detect any typical indels in all of the analyzed off-target sites (Fig. S6). These results demonstrated precise integration of the exogenous gene at bROSA26 locus without detected off-target modification.

Gene-edited cattle with increased resistance to tuberculosis

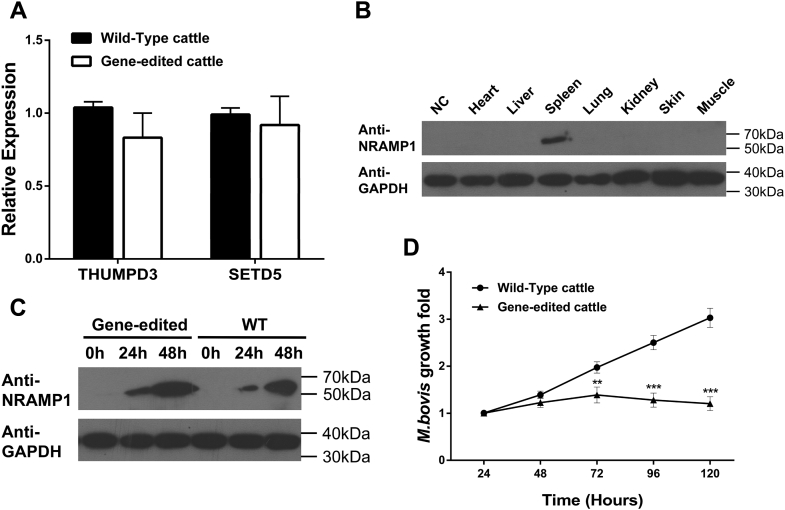

We isolated mononuclear cells from the peripheral blood of gene-edited cattle and wild-type cattle and induced them into macrophages. The monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) were separated from each animal individually and mixed for subsequent studies. To test whether bROSA26 locus can support predictable exogenous gene expression while minimizing the impact on the expression of nearby endogenous genes in gene-edited cattle. We extracted mRNA from the MDMs of gene-edited cattle and wild-type cattle and performed qPCR analysis. No significant difference was detected in the relative levels of expression of the nearby endogenous genes (SETD5 and THUMPD3) between the gene-edited and wild-type cattle (Fig. 5A). Note that no expression of LHFPL4 was detected between the gene-edited and wild-type cattle. Subsequently, we extracted protein from the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, skin, and muscle of the gene-edited cattle for western blot analyses using the goat anti-rabbit NRAMP1 polyclonal antibody. Previous promoter activity analysis did not detect significant difference between the NRAMP1 promoter groups and the control groups in BFFs, which suggested that donor cells could not express NRAMP1 gene in BFFs (Fig. 1D). Therefore, donor cells that were used for generating the gene-edited cattle served as negative control. We detected NRAMP1-specific bands in the spleen, whereas no reaction was observed in other tissues and negative control (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that the expression of NRAMP1 gene was only observed in the spleen as observed in conventional cattle and did not disrupt the adjacent genes.

Figure 5.

Assessment of the increased resistance of gene-edited cattle to tuberculosis.A, the relative expression levels of the nearby endogenous genes at the ROSA26 locus by qPCR. B, western blot analyses to detect NRAMP1 expression using the goat anti-rabbit NRAMP1 polyclonal antibody. The organs were obtained from a pool of dead gene-edited cattle. Donor cells were used for negative control (NC). C, the expression of NRAMP1 was highly activated in the gene-edited cattle following M. bovis infection. All the samples were mixed MDMs that were isolated from the blood of gene-edited cattle as a pool. “WT” represents wild-type cattle. D, multiplication of M. bovis in MDMs from wild-type cattle or gene-edited cattle in vitro. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Student's t-test was used to evaluate the differences. ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

We wonder whether the over-expression of NRAMP1 endowed the ability of gene-edited cattle to respond to M. bovis infection. We performed NRAMP1-specific western blot analyses and CFU assays on MDMs from gene-edited cattle and wild-type cattle after M. bovis infection. The NRAMP1 protein level of MDMs from gene-edited cattle and wild-type cattle both increased after infection as time went on. However, we observed a more remarkable robust expression of NRAMP1 in the gene-edited groups than wild-type groups that revealed the endogenous NRAMP1 protein expression level (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, compared with the wild-type cattle, the rate of M. bovis multiplication in the MDMs of gene-edited cattle was lower (Fig. 5D). These data clearly demonstrated that the over-expression of NRAMP1 endowed the ability of gene-edited cattle to respond to M. bovis infection and further demonstrated that insertion of the exogenous gene into ROSA26 locus can support predictable functional gene expression without disrupting the adjacent genes.

Discussion

Here we developed this approach by an HMEJ-based method to target bovine ROSA26 locus, identified as a potential GSH in cattle, for the production of gene-edited cattle with increased resistance to tuberculosis. We choosed bovine endogenous ROSA26 promoter to drive selected markers expression by adding SA sequence in the donor plasmid, which largely avoided problems caused by random integration; thus, the endogenous promoter could even further increase the ratio of positive cells than the exogenous promoter could. Otherwise, by using an inverted NRAMP1 gene expression cassette, we tried to eliminate potential problems due to “leaky” transcription driven by endogenous promoter. However, the ROSA26 promoter exhibited a moderate activity level, so that it could express the selected markers but weakly. In this study, low concentration of puromycin (1 μg/ml) enabled the reduction in death of positive cells during the selection process; hence, surviving cells may be not entirely targeted colonies. Otherwise, lucky off-target on a region following a promotor may also cause the existence of false-positive cells. The two hypotheses were consistent with the results of NHEJ-mediated reporter genes addition and HMEJ-mediated functional gene integration (Figs. S4 and S5, B and C).

ROSA26 locus provided an open chromatin structure and ubiquitously expressed (27, 39). Therefore, insertion of NRAMP1 gene in this region could avoid being silent due to chromatin inactivation. So far, several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of targeting ROSA26 locus intron 1 region in several species (26, 31). Here, we similarly targeted the intron 1 sequence of the bROSA26 locus and showed the efficient insertion and predictable expression of functional gene without toxicity to cells and hosts and without distraction to adjacent genes. This study indicated that bROSA26 locus might be a GSH in the bovine genome. To date, no definitive rules are available for predicting and detecting potential off-target effects, but several unbiased methods for genome-wide assessment of off-target effects have been proposed (40, 41). Although no off-target modifications were observed, more detections will be performed in an unbiased manner.

Because of the lack of pluripotent embryonic stem cells of livestock (42) and chimerism brought about by microinjection, SCNT technology is available for the production of gene-edited livestock, especially for monotocous cattle. Selecting efficiently targeted colonies with rapid growth is critical to subsequent SCNT. To the best of our knowledge, this is achieved by an HDR-based method for livestock. However, because of high costs and heavy work brought about by HDR-mediated low insertion efficiency of large DNA fragment, the HMEJ-based method provides a new strategy for the exogenous gene KI. In this study, the integration efficiency of reporter genes was systematically compared between HMEJ-, NHEJ-, MMEJ-, and HDR-based methods in BFFs using a promoterless donor reporter system. HMEJ-mediated gene integration is superior to the other three methods because of its high efficiency and precision, which is similar to previous reports (17, 20). Despite the fact that NHEJ-based method permits KI of a large DNA fragment in some human cell lines (16), it is not available for BFFs. The reason for different results is unclear. Concerning the ineffectivity of NHEJ in certain types of cells, we suspected that the directionless and more random integration was likely to reduce the observed KI efficiency due to lack of HA. Additionally, during the process of classical NHEJ repair, small indels are more likely to be introduced at the DSB sites, which leave the insertion of a large DNA fragment at a disadvantage.

Recent studies showed the generation of mCherry KI cynomolgus monkey via microinjection and HMEJ strategy (19). Here, we demonstrated the feasibility of the HMEJ-based method stimulating a functional gene efficient precise integration in cattle. In our study, the combination of the HMEJ-based method with SCNT technology drastically increased the rates of pregnancy and birth of NRAMP1 KI cattle. Previous studies showed the possibility of HMEJ as a new pathway that may involve in SSA pathway (17, 20). Because HMEJ-, unlike HDR-, mediated genome editing has been observed in dividing and nondividing cells (20). Moreover, in previous experiments, the efficiency of HMEJ was different in certain types of cells when they were treated with HR boosters or NHEJ inhibitors that both improve KI efficiency of HDR (20). Considering all factors, we recommend the use of HMEJ-based method for primary and established cell lines of livestock, especially when targeting occurs at heavily methylated or even inactivated regions or in nondividing cells. Therefore, it would be interesting to further improve the efficiency of precise integration based on HMEJ pathway. Some optimizations have been developed for HDR-based integration efficiency, including minimizing the replaced sequence surrounding the DSB (17), suppressing NHEJ pathway (14), and promoting HDR pathway (15). Similar optimizations are also applicable for the HMEJ pathway. Hence, the specific mechanism of HMEJ pathway should be further investigated. Previous studies suggested that CRISPR/Cas9 system could cleave both alleles of cattle genome (2, 4). With the improvement of HMEJ-based KI efficiency, it seems possible to produce homozygous KI livestock by one-step target. Otherwise, considering its inefficiency, targeted KI via HDR remains an issue in zygotes because selection markers are not available (43). The HMEJ-based method circumvents current bottleneck and provides a novel approach to facilitate powerful KI in livestock via microinjection. In addition, gene targeting with HMEJ-based method may be useful for the production of marker-free KI livestock via SCNT as well. In summary, we demonstrate that bROSA26 locus can be used as a potential GSH for the insertion of reporter or functional gene in cattle that show predictable expression and minimized disturbance to nearby endogenous genes. On the other hand, the significantly high percentage of a long functional gene fragment integrating into the locus suggests that the HMEJ-based method, superior to HDR-based method, can contribute to producing KI cattle with increased resistance to tuberculosis. HMEJ-based safe-harbor genome editing may become a new standard to generate precise KI livestock. Our study facilitates the establishment of a safe and efficient genome editing system in livestock and provides a valuable new path for agricultural production.

Experimental procedures

3ʹ RACE analysis

3ʹ RACE was performed using the SMARTer RACE 5'/3' Kit (Clontech), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Synthesized cDNAs were amplified using a universal primer A mix with 3ʹ RACE primer (primers shown in Fig. S2). Amplified cDNAs were cloned into the T-Vector pMD19 (Simple) (Clontech), and their sequences were confirmed.

QPCR and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from various adult tissues (tissue samples ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen) or macrophages using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Purified RNA was reverse-transcribed using a HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme Biotech). QPCR was performed with an ABI StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech). The comparative Ct method was used to calculate the relative quantity of the target gene mRNA, normalized to bovine β-actin, and was expressed as the fold change = 2−ΔΔCt. Primer sequences used for qPCR are listed in Table S1. Exon 1 and exon 2 cDNA by RT-PCR were detected using the following primer set: forward 5ʹ-GAGCGGAACTCTGGTG-3ʹ and reverse 5ʹ-TGGACTATTAAGAGGGTCA-3ʹ. PCR was performed using TransStart FastPfu DNA Polymerase (TransGen Biotec) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Construction of vectors

The promoter reporter vector pGL4.10-pROSA26-2007 was generated by inserting the promoter fragment into the luciferase reporter vector pGL4.10. Based on the pGL4.10-2007 vector, eight upstream truncated promoter reporter vectors were generated, including pGL4.10-1807/+505 (−1807/+505), pGL4.10-1607/+505 (−1607/+505), pGL4.10-1407/+505 (−1407/+505), pGL4.10-1207/+505 (−1207/+505), pGL4.10-1007 /+505 (−1007/+505), pGL4.10-807/+505 (−807/+505), pGL4.10-607/+505 (−607/+505), and pGL4.10-407/+505 (−407/+505). Based on the pGL4.10-1007/+505 vector, five downstream truncated promoter reporter vectors were constructed, including pGL4.10-1007/+405 (−1007/+405), pGL4.10-1007/+305 (−1007/+305), pGL4.10-1007/+205 (−1007/+205), pGL4.10-1007/+105 (−1007/+105), and pGL4.10-1007/+5 (−1007/+5). The NRAMP1 promoter fragment was inserted into the pGL4.10 vector to generate the pGL4.10-pNRAMP1. The strong promoter pGL4.10-pCMV and pGL4.10-pEF1α vectors served as positive controls, generated by the same way. The primers were shown as Tables S2 and S3. Sequences between –2007 and –407 were amplified with same reverse primers and sequences between +505 and +5 were amplified with same forward primers.

The SSA reporter plasmids (pSSA-sgRNA11, pSSA-sgRNA34, pSSA-sgRNA43, pSSA-sgRNA44, and pSSA-sgRNA45) were generated by respectively inserting five different target sites into the pSSA-1-3 reporter plasmid.

Cas9/sgRNA11-puro, Cas9/sgRNA34-puro, Cas9/sgRNA43-puro, Cas9/sgRNA44-puro, and Cas9/sgRNA45-puro were generated based on pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro (PX458, Addgene plasmid #48139) for selection of target sites and Cas9/sgRNA11 was generated based on pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (PX458, Addgene plasmid #48138) for electroporation by previous method (44). The primers used to clone each sgRNA are available in Table S4.

Cell culture

Primary BFFs were isolated from 35 to 40-day-old fetuses. The tissues were minced, plated on 60-mm Petri dishes (Corning Costar), and cultured with DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS at 38.5 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Then the cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution (Gibco) and frozen in 90% FBS and 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), for long-term storage and future use. When needed, BFFs were thawed and grown in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 38.5 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. 293T cells (ATCC) were cultured with DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco).

Transfection and luciferase assays

One day before transfection, BFFs were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate for assaying the promoter of bROSA26 gene. Approximately 0.5 μg of plasmids (0.4 μg for pGL4.10-promoter or empty vector pGL4.10 and 0.1 μg for pRL-TK) was cotransfected according to the protocol of FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). The pRL-TK plasmid vector was used as an internal reference vector for standardizing transfection efficiency.

One day before transfection, 293T cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well of a 24-well plate for assaying the activity of sgRNAs. Approximately 0.8 μg of plasmids (0.18 μg for SSA reporter plasmid and 0.6 μg Cas9 expression plasmids containing 20-nt guide sequence or pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro and 0.02 μg for pRL-SV40) was cotransfected according to the protocol of FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). The pRL-SV40 plasmid vector was used as an internal reference vector for standardizing transfection efficiency.

Cell lysates were collected 48 h posttransfection and prepared for luciferase activity analysis using the Double-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (TransGen Biotec) following the manufacturer's instructions. Relative luciferase activities were expressed as the ration of the luciferase value to the Renilla value.

Electroporation

Selection of individual colonies was achieved via electroporation. BFFs were thawed and grown in DMEM/F12 (Gibco) medium supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 38.5 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. At 70–80% confluency, cells (5 × 106) were trypsinized and resuspended in Opti-MEM (Gibco), mixed with 5 μg of donor plasmid and 5 μg of Cas9-encoding plasmid, and electroporated at 510 V with one pulses of 2-ms duration using the BTX Electro-cell manipulator ECM2001 (BTX Technologies). Electroporated cells were plated on 10-cm plates at 5 × 105 cells per plate. Individual colonies were selected and expanded after puromycin selection 10–12 days (1 μg/ml 9–11 days after 2 μg/ml 1–2 days) after electroporation.

Detection of individual colonies by PCR

Puromycin-resistant cell colonies derived from the transfected cell populations were collected by trypsinization, and 80% of these were plated in serum-containing culture medium and expanded. The remaining colonies were resuspended in 20 μl of PCR-compatible lysis buffer (40 mM of Tris-HCl, pH 8.8; 0.9% NP-40; 0.9% Trition X-100; 0.4 mg/ml of proteinase K) for PCR analysis. The lysates were incubated at 65 °C for 15 min and then at 95 °C for 10 min. To distinguish the targeted cell colonies, 5 μl of the DNA lysate was added to a PCR reaction with PCR primers for 5ʹ junction PCR and subjected to PCR with EmeraldAmp (Takara Bio) using standard methods. Subsequently, 3ʹ junction PCR was performed on the positive colonies to confirm the correct targeting events. The primers used for junction PCR were shown as Table S5.

FACS analyses

To determine the percentage of cells that are EGFP-positive (KI by HDR-, HMEJ-, MMEJ-, or NHEJ-based method), BFFs were seeded in 6-well plates, and approximately 2.5 μg of plasmids (1.25 μg for Cas9/sgRNA11 and 1.25 μg for one of four types of donors) was transfected according to the protocol of FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (Promega) as indicated the next day. Seven days after transfection, cells were sorted to purify EGFP-positive cells using an FACSAria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo data analysis software (FlowJo, LLC).

Southern blot analyses

PCR products were labeled with digoxigenin using the DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche Diagnostics). Genomic DNA was subjected to phenol/chloroform extraction and precipitated with isopropyl alcohol. BamHI-digested DNA was separated on 1% (wt/vol) agarose gels, transferred to a nylon membrane (GE Health-care), and hybridized with 3ʹ-end digoxigenin-labeled probes. The following procedures were performed using the DIG-High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Somatic cell nuclear transfer

Briefly, bovine oocytes were aspirated according to previously described methods (45). Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from 2 to 8 mm antral follicles. Only COCs with compact cumulus and evenly granulated cytoplasm were washed thrice in collection medium (M199; Gibco, BRL) supplemented with 10% (v) FBS and cultured in bicarbonate-buffered tissue culture medium 199 (TCM-199; Gibco, BRL) supplemented with 10% (v) FBS, 0.02 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, 0.075 IU/100 ml human menopausal gonadotropin, 2 μg/ml 17-estradiol, 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, and 10 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor and 0.1% (v/v) Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium for 18–20 h at 38.5 °C in 5% CO2 in air. Cumulus cells were stripped from COCs in in vitro operation medium (HM199 supplemented with 3 mg/ml BSA, 0.04 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, and 0.17% (v/v) glutamax) containing 0.1% bovine testicular hyaluronidase and incubated in in vitro operation medium containing 7.5 μg/ml cytochalasin B (CB) and 10 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 10 min prior to enucleation. Matured oocytes were enucleated by aspirating the PB (polar body) and a small amount of surrounding cytoplasm in microdrops of in vitro operation medium supplemented with 7.5 μg/ml CB and 20% FBS. The aspirated cytoplasm was examined under ultraviolet radiation to confirm that the nuclear material had been removed. Nuclear donor cells were induced in G0 phase of cell cycle by serum deprivation prior to use for SCNT. The disaggregated donor cell was injected into the perivitelline space of enucleated oocytes. The oocyte–cell couplet was sandwiched with a pair of platinum electrodes connected to the micromanipulator in microdrop of Zimmermann's fusion medium. A double electrical pulse of 32 V for 20 μs was applied for oocyte–cell fusion. Successfully reconstructed embryos were kept in mSOFaa for 3 h. Reconstructed embryos were activated in 5 μM ionomycin for 4 min, followed by exposure to 2 mM dimethylaminopyridine in mSOFaa medium for 4 h. Embryos were then cultured in mSOFaa medium supplemented with 6 mg/ml BSA in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 7% O2 and 90% N2 at 38.5 °C. The high-quality blastocysts were nonsurgically transferred (one embryo per recipient) to the uterine horn ipsilateral to the corpus luteum in recipients in the 7 days of standing oestrus. Pregnancy was detected by rectal palpation ultrasonography.

Off-target analyses

Potential off-target sites in the bovine genome were identified using the Cas-OFFinder (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/). We selected the eight sites with the highest risk of being edited. PCR products were obtained by amplification from every gene-edited calve genome and performed Sanger sequencing. The sequences of sgRNA11 potential off target sites were shown as Table S6. The primers were shown as Table S7.

Western blot analyses

Cells or liquid nitrogen grinded tissues were lysed in ice-cold RIPA cell buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Thermo Scientific). The proteins were separated with 12% acrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The primary antibody (1:500) used to detect NRAMP1 was from Abcam (Rockville, Catalogue No. ab59696) and the antibody for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was from Cell Signaling Technology (Cat# 2118L). Goat anti-rabbit HRP was used for secondary antibody for all the primary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #31460).

Isolation and differentiation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

PBMCs were isolated from blood of wild-type cattle or gene-edited cattle using Bovine Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Separation Fluid Kit (TBD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Macrophages used in this study were derived from PBMCs by stimulation with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor for 7 days.

CFU assay

Infection with M. bovis was performed according to previously described methods (2). In brief, a bacterial suspension (∼107 bacteria per 106 cells) was added to the medium and incubated at 37 °C and 5% (vol/vol) CO2 for 4 h. Cells then were washed extensively with PBS to remove noningested bacteria. At the time points indicated in the text after infection, bacterial CFU was quantitated by plating on 7H10 agar plates (Difco Laboratories).

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± SD and are derived from at least three independent experiments. Student's t-test was used to evaluate the differences between groups using Prism software. p-Value > 0.05 was considered as not significant (ns), 0.01 < p < 0.05 as significant and indicated with one asterisks ∗, 0.001 < p < 0.01 very significant and indicated with two asterisks ∗∗, 0.0001 < p < 0.001 extremely significant and indicated with three asterisks ∗∗∗.

Ethics approval

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines for the care and use of animals of Northwest A&F University. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care Commission of the College of Veterinary Medicine, Northwest A&F University. Every effort was made to minimize animal pain, suffering, and distress and to reduce the number of animals used.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supporting information, tables, or from the corresponding author upon request.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Tong Xu and Ruizhi Deng for carefully correcting the paper and the Keyuan Cloning Company for their assistance in the gene-edited cattle production. This work was supported by the National Major Project for Production of Transgenic Breeding (No. 2016ZX08007003).

Author contributions

M. Y., Y. G., and Y. Z. designed the study. M. Y., J. Z., Z. Y., Z. Z., and Y. W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. M. Y. wrote the article under the guidance of Y. Z. and Y. G. Y. G., Y. W., T. W., and J. H. revised and edited the article.

Edited by Qi-Qun Tang

Supporting information

References

- 1.Carlson D.F., Lancto C.A., Zang B., Kim E.S., Walton M., Oldeschulte D., Seabury C., Sonstegard T.S., Fahrenkrug S.C. Production of hornless dairy cattle from genome-edited cell lines. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:479–481. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao Y., Wu H., Wang Y., Liu X., Chen L., Li Q., Cui C., Liu X., Zhang J., Zhang Y. Single Cas9 nickase induced generation of NRAMP1 knockin cattle with reduced off-target effects. Genome Biol. 2017;18:13. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miao X. Recent advances in the development of new transgenic animal technology. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70:815–828. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1081-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niu D., Wei H.J., Lin L., George H., Wang T., Lee H., Zhao H.Y., Wang Y., Kan Y.N., Shrock E., Lesha E., Wang G., Luo Y.L., Qing Y.B., Jiao D.L. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2017;357:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma T., Tao J.L., Yang M.H., He C.J., Tian X.Z., Zhang X.S., Zhang J.L., Deng S.L., Feng J.Z., Zhang Z.Z., Wang J., Ji P.Y., Song Y.K., He P.L., Han H.B. An AANAT/ASMT transgenic animal model constructed with CRISPR/Cas9 system serving as the mammary gland bioreactor to produce melatonin-enriched milk in sheep. J. Pineal Res. 2017;63 doi: 10.1111/jpi.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanthalingam S., Tibary A., Beever J.E., Kasinathan P., Brown W.C., Srikumaran S. Precise gene editing paves the way for derivation of Mannheimia haemolytica leukotoxin-resistant cattle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:13186–13190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613428113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaj T., Gersbach C.A., Barbas C.F. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filippo J.S., Sung P., Klein H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:229–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061306.125255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McVey M., Lee S.E. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director's cut): Deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet. 2008;24:529–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nussenzweig A., Nussenzweig M.C. A backup DNA repair pathway moves to the forefront. Cell. 2007;131:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson S.P., Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shrivastav M., De Haro L.P., Nickoloff J.A. Regulation of DNA double-strand break repair pathway choice. Cell Res. 2008;18:134–147. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung C.J., Zhang J.L., Trenchard E., Lloyd K.C., West D.B., Rosen B., de Jong P.J. Efficient gene targeting in mouse zygotes mediated by CRISPR/Cas9-protein. Transgenic Res. 2017;26:263–277. doi: 10.1007/s11248-016-9998-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu V.T., Weber T., Wefers B., Wurst W., Sander S., Rajewsky K., Kuhn R. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song J., Yang D.S., Xu J., Zhu T.Q., Chen Y.E., Zhang J.F. RS-1 enhances CRISPR/Cas9-and TALEN-mediated knock-in efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X.J., Tan C.L., Wang F., Wang Y.F., Zhou R., Cui D.X., You W.X., Zhao H., Ren J.W., Feng B. Knock-in of large reporter genes in human cells via CRISPR/Cas9-induced homology-dependent and independent DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang J.P., Li X.L., Li G.H., Chen W.Q., Arakaki C., Botimer G.D., Baylink D., Zhang L., Wen W., Fu Y.W., Xu J., Chun N., Yuan W.P., Cheng T., Zhang X.B. Efficient precise knockin with a double cut HDR donor after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated double-stranded DNA cleavage. Genome Biol. 2017;18 doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bressan R.B., Dewari P.S., Kalantzaki M., Gangoso E., Matjusaitis M., Garcia-Diaz C., Blin C., Grant V., Bulstrode H., Gogolok S., Skarnes W.C., Pollard S.M. Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-assisted gene targeting enables rapid and precise genetic manipulation of mammalian neural stem cells. Development. 2017;144:635–648. doi: 10.1242/dev.140855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao X., Liu Z., Wang X., Wang Y., Nie Y.H., Lai L., Sun R.L., Shi L.Y., Sun Q., Yang H. Generation of knock-in cynomolgus monkey via CRISPR/Cas9 editing. Cell Res. 2018;28:379–382. doi: 10.1038/cr.2018.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao X., Wang X., Hu X.D., Liu Z., Liu J.L., Zhou H.B., Shen X.W., Wei Y., Huang Z.J., Ying W.Q., Wang Y., Nie Y.H., Zhang C.C., Li S.L., Cheng L.P. Homology-mediated end joining-based targeted integration using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Res. 2017;27:801–814. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z.Y., Wang F.Q., Cui Y., Liu Z.Z., Guo X.G., Zhang Y.Q., Deng Y., Zhao H., Chen Y.L. Heritable CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted integration in Xenopus tropicalis. FASEB J. 2015;29:4914–4923. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-273425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auer T.O., Duroure K., De Cian A., Concordet J.P., Del Bene F. Highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in in zebrafish by homology-independent DNA repair. Genome Res. 2014;24:142–153. doi: 10.1101/gr.161638.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ochiai H., Sakamoto N., Fujita K., Nishikawa M., Suzuki K.I., Matsuura S., Miyamoto T., Sakuma T., Shibata T., Yamamoto T. Zinc-finger nuclease-mediated targeted insertion of reporter genes for quantitative imaging of gene expression in sea urchin embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:10915–10920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202768109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadelain M., Papapetrou E.P., Bushman F.D. Safe harbours for the integration of new DNA in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papapetrou E.P., Schambach A. Gene insertion into genomic safe harbors for human gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:678–684. doi: 10.1038/mt.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irion S., Luche H., Gadue P., Fehling H.J., Kennedy M., Keller G. Identification and targeting of the ROSA26 locus in human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1477–1482. doi: 10.1038/nbt1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambrowicz B.P., Imamoto A., Fiering S., Herzenberg L.A., Kerr W.G., Soriano P. Disruption of overlapping transcripts in the ROSA beta geo 26 gene trap strain leads to widespread expression of beta-galactosidase in mouse embryos and hematopoietic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:3789–3794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi T., Kato-Itoh M., Yamaguchi T., Tamura C., Sanbo M., Hirabayashi M., Nakauchi H. Identification of rat Rosa26 locus enables generation of knock-in rat lines ubiquitously expressing tdTomato. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2981–2986. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang D.S., Song J., Zhang J.F., Xu J., Zhu T.Q., Wang Z., Lai L.X., Chen Y.E. Identification and characterization of rabbit ROSA26 for gene knock-in and stable reporter gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep25161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu M., Wei C., Lian Z., Liu R., Zhu C., Wang H., Cao J., Shen Y., Zhao F., Zhang L., Mu Z., Wang Y., Wang X., Du L., Wang C. Rosa26-targeted sheep gene knock-in via CRISPR-Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24360. doi: 10.1038/srep24360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X.P., Yang Y., Bu L., Guo X.G., Tang C.C., Song J., Fan N.N., Zhao B.T., Ouyang Z., Liu Z.M., Zhao Y., Yi X.L., Quan L.Q., Liu S.C., Yang Z.G. Rosa26-targeted swine models for stable gene over-expression and Cre-mediated lineage tracing. Cell Res. 2014;24:501–504. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M., Sun Z.L., Zou Z.Y., Ding F.R., Li L., Wang H.P., Zhao C.J., Li N., Dai Y.P. Efficient targeted integration into the bovine Rosa26 locus using TALENs. Sci. Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28502-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grange J.M. Mycobacterium bovis infection in human beings. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:71–77. doi: 10.1054/tube.2000.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thoen C., LoBue P., de Kantor I. The importance of Mycobacterium bovis as a zoonosis. Vet. Microbiol. 2006;112:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayele W.Y., Neill S.D., Zinsstag J., Weiss M.G., Pavlik I. Bovine tuberculosis: An old disease but a new threat to Africa. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2004;8:924–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waters W.R., Palmer M.V., Buddle B.M., Vordermeier H.M. Bovine tuberculosis vaccine research: Historical perspectives and recent advances. Vaccine. 2012;30:2611–2622. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhakta M.S., Segal D.J. The generation of zinc finger proteins by modular assembly. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;649:3–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-753-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hedges J.F., Kimmel E., Snyder D.T., Jerome M., Jutila M.A. Solute carrier 11A1 is expressed by innate lymphocytes and augments their activation. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4263–4273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giel-Moloney M., Krause D.S., Chen G., Van Etten R.A., Leiter A.B. Ubiquitous and uniform in vivo fluorescence in ROSA26-EGFP BAC transgenic mice. Genesis. 2007;45:83–89. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai S.Q., Joung J.K. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016;17:300–312. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsai S.Q., Nguyen N.T., Malagon-Lopez J., Topkar V.V., Aryee M.J., Joung J.K. CIRCLE-seq: A highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H., Wu Z. Genome editing of pigs for agriculture and biomedicine. Front. Genet. 2018;9:360. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimi K., Kunihiro Y., Kaneko T., Nagahora H., Voigt B., Mashimo T. ssODN-mediated knock-in with CRISPR-Cas for large genomic regions in zygotes. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D.A., Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cibelli J.B., Stice S.L., Golueke P.J., Kane J.J., Jerry J., Blackwell C., de Leon F.A.P., Robl J.M. Cloned transgenic calves produced from nonquiescent fetal fibroblasts. Science. 1998;280:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supporting information, tables, or from the corresponding author upon request.