Abstract

Background

Low/middle-income countries (LMICs) face triple burden of malnutrition associated with infectious diseases, and non-communicable diseases. This review aims to synthesise the available data on the delivery, coverage, and effectiveness of the nutrition programmes for conflict affected women and children living in LMICs.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO databases and grey literature using terms related to conflict, population, and nutrition. We searched studies on women and children receiving nutrition-specific interventions during or within five years of a conflict in LMICs. We extracted information on population, intervention, and delivery characteristics, as well as delivery barriers and facilitators. Data on intervention coverage and effectiveness were tabulated, but no meta-analysis was conducted.

Results

Ninety-one pubblications met our inclusion criteria. Nearly half of the publications (n=43) included population of sub-Saharan Africa (n=31) followed by Middle East and North African region. Most publications (n=58) reported on interventions targeting children under 5 years of age, and pregnant and lactating women (n=27). General food distribution (n=34), micronutrient supplementation (n=27) and nutrition assessment (n=26) were the most frequently reported interventions, with most reporting on intervention delivery to refugee populations in camp settings (n=63) and using community-based approaches. Only eight studies reported on coverage and effectiveness of intervention. Key delivery facilitators included community advocacy and social mobilisation, effective monitoring and the integration of nutrition, and other sectoral interventions and services, and barriers included insufficient resources, nutritional commodity shortages, security concerns, poor reporting, limited cooperation, and difficulty accessing and following-up of beneficiaries.

Discussion

Despite the focus on nutrition in conflict settings, our review highlights important information gaps. Moreover, there is very little information on coverage or effectiveness of nutrition interventions; more rigorous evaluation of effectiveness and delivery approaches is needed, including outside of camps and for preventive as well as curative nutrition interventions.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019125221.

Keywords: nutrition, child health

Key questions.

What is already known?

Women and children affected by conflict suffer from high burden of malnutrition and poor nutritional outcomes.

In recent decades, conflict related deaths resulting from malnutrition and other health problems have increased significantly to the extent where they are now being considered a public health problem.

What are the new findings?

General food distribution was the most common intervention provided in the included studies.

Most of the intervention were delivered to refugee populations in camp settings and through community-based approaches.

Very few studies reported on coverage and effectiveness of the nutritional interventions.

Key delivery facilitators included community advocacy and social mobilisation, effective monitoring and the integration of nutrition and other sectoral interventions and services.

Key delivery barriers included insufficient resources, nutritional commodity shortages, security concerns, poor outcome reporting, limited cooperation and difficulty accessing and following-up of beneficiaries.

What do the new findings imply?

Studies and research should be conducted to generate and strengthen evidence on coverage, access and improvement in delivery of nutritional interventions in context to conflict setting with rigorous and improved assessment methods.

Studies should also study on multi-sectoral programming approach and its integration with early childhood development and mental health, which is an emerging issue.

Introduction

Armed conflict is defined as ‘a political conflict in which armed combat involves the armed forces of at least one state (or one or more armed factions seeking to gain control of all or part of the state), and in which people have been killed by the fighting during the course of the conflict’.1 It originates due to social, individual and cultural differences, which leads to poverty, violence, malnutrition and mortality.2

Globally, 136 million people are in need of assistance due to conflict, while 52 million children suffer from acute malnutrition where disease epidemics are a global threat.3 4 Low/middle-income countries (LMICs) face triple burden of malnutrition,5 which is more complicated where there is increase in protracted and recidivist conflict, population displacement and urban warfare.6

According to a recent systematic review by Blanchet et al,7 several nutritional programmes have been implemented by humanitarian organisations to aid vulnerable populations during emergency settings.8 According to recent Sphere guidance, although food insecurity is one cause of malnutrition, providing food assistance to vulnerable population is unlikely to contribute to a long lasting solution.9 Thus, a multi-sectoral approach to food and nutrition response in conflict settings has been advocated. Successful nutrition interventions in non-conflict nutrition settings are characterised by a combination of political commitment, multi-sectoral collaboration, community engagement, community-based service delivery platform, and wider programme coverage and compliance.10 In conflict settings, consensus on specific guidelines uptake is still obscure, hence, stronger scientific evidence of implementing effective nutrition interventions is required.

In this review we aimed to synthesise the data and information currently available on how nutrition interventions for women and children have been delivered in conflict settings, and the reported barriers and facilitators of programme delivery. We also aimed to synthesise the available data on the coverage of nutrition programmes for women and children in such settings and their effectiveness.

Methods

This systematic review on nutritional interventions is a part of series of reviews in conflict settings which includes delivery of mental health, sexual and reproductive health and other interventions in conflict settings.11–18 This review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (online supplemental appendix 1),19 and its protocol is registered with PROSPERO (the international prospective register of systematic reviews, www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

bmjgh-2020-004897supp001.pdf (255.6KB, pdf)

Search strategy and selection criteria

We systematically searched MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO online databases for indexed journal articles published between 1 January 1990 and 31 March 2018 using search terms relating to women, children or adolescents accessing or receiving nutrition-specific interventions in conflict or post-conflict settings in LMICs (online supplemental appendix 2). In addition to the indexed literature, we also searched grey literature published between 1 January 2013 and 30 November 2018 on the websites of 10 major humanitarian organisations who are actively involved in responding to or researching conflict situations: Emergency Nutrition Network, International Committee of the Red Cross, International Rescue Committee, Médecins Sans Frontières, Save the Children, United Nations Population Fund, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNICEF, Women’s Refugee Commission and World Vision. We used broad terms for conflict and health interventions tailored to the search functionality of each website.

We deduplicated all retrieved indexed records using Endnote X7 software,20 and then imported unique records into Covidence software,21 where two reviewers independently conducted screening of each title and/or abstract for relevance. Discrepancies between reviewers’ decisions were resolved via discussion, or by a third reviewer if necessary. A single reviewer then assessed the full text of each potentially relevant publication to determine eligibility for the review. An eligible publication needed to describe a nutrition-specific intervention being delivered during or within five years of cessation of armed conflict to neonates, children, adolescents or women of reproductive age. Same approach was used for assessing grey literature.

For both indexed and grey literature, we excluded case reports of single patients; studies reporting on military personnel, refugee populations in high-income countries, surgical techniques or economic or mathematical modelling; editorials and opinion pieces; guidelines; and reviews.

Data extraction

We extracted relevant qualitative and quantitative information from eligible publications using a structured, pilot tested data abstraction tool in REDCap software in duplicate.22 Discrepancies between reviewers’ data were resolved via discussion, or by a third reviewer if necessary.

Data analysis and synthesis

We descriptively analysed the key characteristics of the included publications, focal populations and reported interventions, including their delivery characteristics, and we tabulated reported estimates of intervention coverage and effectiveness. We compared reported nutrition treatment intervention coverage and effectiveness estimates with key indicators outlined in the Sphere Handbook9 of minimum standards in humanitarian response. We narratively synthesised information on delivery barriers and facilitators retrieved from our included publications. The effectiveness measures included the proportions of those discharged from a malnutrition treatment programme who recovered, defaulted or died.

Results

Characteristics of the included literature

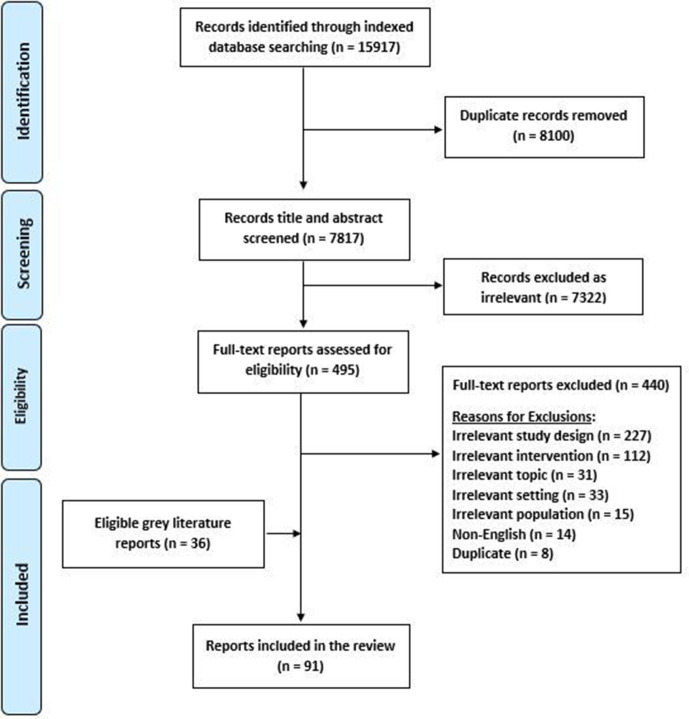

We retrieved a total of 7817 unique citations from our indexed database search, and ultimately assessed 5523–77 of these as eligible for the review (figure 1). An additional 3678–113 eligible publications were identified from the grey literature and from the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews, resulting in a total of 91 publications being included in this review (online supplemental appendix 3).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Nearly half of the included publications (n=43, 47%) reported on nutrition interventions delivered in conflict-affected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and about one-third (n=31, 34%) in the Middle East and North African region (table 1). The country-level distribution of the included publications is illustrated in figure 2. Most publications (n=58, 64%) reported on interventions targeting children under 5 years of age, while 30% (n=27) reported on those targeting pregnant and lactating women. Refugee populations were the most targeted (n=53, 58%), while about one-third reported on internally displaced persons (IDPs) (n=33, 36%) and only about 16% (n=15) reported on intervention delivery among those not displaced. Intervention delivery was reported to occur in camp settings in two-thirds (n=63, 69%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications (n=91)

| Geographic region*† | n |

| East Asia and Pacific | 3 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 5 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 1 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 31 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 43 |

| South Asia | 9 |

| Publication type | n |

| Non-research report | 53 |

| Observational study | 32 |

| Quasi-experimental study | 2 |

| Randomised controlled trial | 4 |

| Target population type† | n |

| All/general population | 29 |

| All women | 4 |

| Women of reproductive age | 4 |

| Pregnant and lactating women | 27 |

| Adolescents | 10 |

| Children under 5 years of age | 58 |

| Displacement status of beneficiary population† | n |

| Refugees | 53 |

| IDPs | 33 |

| Non displaced | 15 |

| Returning refugees | 2 |

| Host | 10 |

| Unreported | 5 |

| Setting of displaced population† | n |

| Camp | 63 |

| Dispersed | 45 |

| Unreported | 2 |

*World Bank regions.

†Individual publications may contribute to multiple categories.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of included publications.

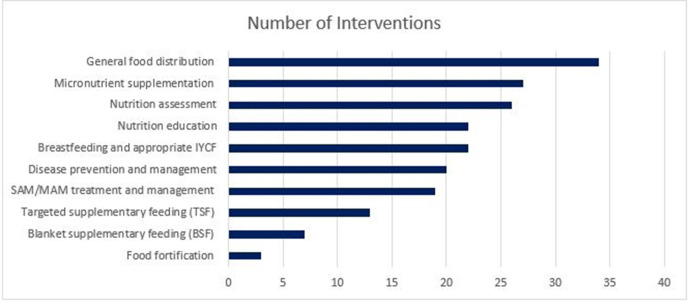

Nutrition intervention delivery

Figure 3 presents the relative frequency of the various nutrition interventions captured in the included literature. Nutrition-specific interventions were implemented either alone, or in combination with other nutrition-specific or nutrition-sensitive interventions or activities. General food distribution (GFD) was the most frequently reported intervention, followed by micronutrient supplementation, nutrition assessment, nutrition education, breast feeding and appropriate feeding, disease prevention and management, supplementary feeding, severe acute malnutrition/moderate acute malnutrition (SAM/MAM) treatment, and food fortification.

Figure 3.

Reported nutrition interventions delivered to conflict-affected women and children. IYCF, infant and young child feeding.

We classified the individual interventions reported in the literature into broader categories, and we synthesise their components and delivery characteristics below.

Nutrition assessment

Twenty-six publications reported on mass screening for malnutrition as a component of other nutrition interventions.23 25 27 29 32 49 51 53 69 73 77 79 83 84 87 88 92 96 100–102 104 107–109 111 Of these, four were published between years 1990 and 2000,23 29 32 77 one between 2001 and 201051 and 21 between 2011 and 2018.25 27 49 53 69 73 79 83 84 87 88 92 96 100–102 104 107–109 111 Ten studies conducted assessment in either hospitals or clinic or both,27 29 32 83 84 101 102 104 108 109 nine studies conducted assessments in mobile clinics which were established by government, non-government organisations (NGO), and United Nations (UN) agencies,25 47 49 79 87 88 96 100 111 four studies conducted assessment at home23 51 53 107 and three studies failed to report on it.33 69 77 Majority of the assessments were conducted at by NGO/UN staff.

Breastfeeding and appropriate infant and young child feeding

We found 22 publications reporting on the delivery of interventions to promote or support breast feeding or other infant and young child feeding (IYCF) interventions.25 28 40 43 47 49 64 65 67 68 78 80 83 86 88 92 98 101 104 105 107 110 Of these, five were published between years 2001 and 2010,28 40 64 65 67 and 17 between 2011 and 2018.25 43 47 49 68 78 80 83 86 88 92 98 101 104 105 107 110 Most commonly, breast feeding was promoted using an outreach approach of home visits conducted by health workers within camp settings.49 64 65 78 98 105 107 In reports on nutrition intervention delivery in Pakistan,25 Jordan92 and Somalia,88 mobile clinics were established by government and UN agencies in collaboration to promote breast feeding and sensitise refugee/internally displaced mothers on safe IYCF practices in and outside camp settings. Four publications reported on IYCF-related educational activities conducted among expectant/new mothers within hospital or clinic settings by community health workers (CHWs) or NGO/UN agency staff.40 68 83 104 In Macedonia, complementary foods were distributed through establishment of a food pipeline—a means to receive, store, and transport all donated food by multiple stakeholders.28 Among refugees and host populations in Jordan, the use of IYCF ‘caravans’80 and ‘safe havens’110 set up by NGOs to provide safe spaces for mothers to breastfeed infants was reported, as well as the distribution of breastfeeding shawls to lactating mothers to provide privacy.80

Disease prevention and management

Twenty publications reported on the delivery of interventions to either prevent and/or manage communicable disease among children under 5 years of age.25 26 29 32 34 40 44 46 49 52 53 62 64–67 73 76 107 108 Of these, six were published between years 1990 and 2000,29 32 34 44 62 76 nine between 2001 and 201025 26 40 46 52 64–67 and five between 2011 and 2018.49 53 73 107 108 Some were conducted along with supplementary feeding as a part of nutrition rehabilitation programmes among refugee or internally displaced children under 5 years of age residing in camps or dispersed among local host populations in conflict settings.25 26 29 32 34 40 44 46 49 53 64–66 76 Seven publications reported on measles or cholera vaccination for children under-five in sub-Saharan African countries,29 32 34 53 66 73 76 delivered mostly at clinics/feeding centres by government or NGO/UN health workers. In India, vaccination was conducted by NGO/UN health workers as part of a measles outbreak response, using an outreach approach.52 Only one publication reported treatment of pregnant refugee women in Rwanda for malaria during antenatal care at UN/NGO clinic.44 Only one publication reported on the delivery of oral rehydration solution or zinc by CHWs to malnourished children under-five with diarrhoea, in a field-based trial among Afghan refugees residing along the border camps.62 Another publication reported on therapeutic treatment of diarrhoea in a hospital setting in Uganda among children under 2 years old.108 Deworming was delivered to children from 12 to 59 months of age as a part of facility/community-based nutrition rehabilitation programmes implemented in camps for refugees and IDPs by government health workers in Nepal, Sri Lanka and Yemen.26 49 107

Food fortification

Food fortification in conflict settings was not very commonly reported in the included literature. Only three publications reported on food fortification of which two were published between 2001 and 2010,70 75 and one between 2011 and 2018.36 Two reported on locally produced and milled wheat or maize flour fortification, distributed by NGO/UN staff within the food baskets for camp-based refugees in Afghanistan and Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).70 75 One recently published research study in Palestine reported the implementation of a fortification programme in the West Bank and Gaza, but how such fortified foods were delivered to women, children or households was not described.36

Micronutrient supplementation

Twenty-seven publications reported on the delivery of micronutrient supplementation interventions to women or children in conflict settings.26 30 31 34 36 37 40 44 49 50 52 55 56 58 59 63–65 71 72 74 79 83 100 101 107 108 Of which five were published between years 1990 and 2000,31 34 44 58 74 10 between 2001 and 201037 40 52 55 56 59 64 65 72 79 and 12 between years 2011 and 2018.26 30 36 49 50 63 71 83 100 101 107 108 Micronutrient supplementation in the form of powders was observed from year 2011 and onwards.26 63 107 108 We found six publications reporting iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation being provided to pregnant or lactating women, among camp-based refugees or IDPs in Thailand,30 Rwanda,44 Palestine,56 Jordan,79 Lebanon100 and Yemen.107 IFA supplementation was delivered as part of routine antenatal care by health workers in the community-based primary health clinic/mobile clinics run by NGOs and/or local government. Two publications reported on thiamine supplementation for pregnant women living in camps along the Thai-Burma border30 and visiting antenatal clinics of Shoklo Malaria Research Unit.59 In Tanzania, camp-based refugees were provided with stainless steel cooking pots at community-based distribution points in a study to evaluate their effectiveness in reducing iron deficiency anaemia.72

Vitamin A supplementation for non-displaced/IDP/refugee children under-five living in West Bank and Gaza,36 56 Guinea Bissau,59 65 Nepal,26 India52 and Thailand71 was reported in seven publications, sometimes delivered as a part of measles treatment protocol implemented at outreach level by health workers.52 64 65 71 The delivery of multiple micronutrient (MMN) supplements for non-displaced/IDP/refugee women and children residing in Guinea Bissau,59 64 Afghanistan,37 Malawi,58 Nepal,26 Lebanon,100 Uganda108 and Yemen107 was reported in eight publications, distributed most commonly in powder, ready-to-use spread or cereal form through primary health centres or clinics. One publication reported on a randomised controlled trial in which pregnant women were provided with MMN tablets in Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya.50 Two publications reported on vitamin C supplementation interventions for refugee children in Ethiopia,31 and non-displaced children and adults in Afghanistan,37 although delivery modes were unreported. One publication reported on mass vitamin B complex supplementation provided to the general population by UN agencies in collaboration with local government as an emergency response to a pellagra outbreak in Malawi; where delivery site was unreported.58 Two publications reported on the delivery of micronutrient supplementation while providing nutrition rehabilitation through primary healthcare facilities to non-displaced children in Syria101 and refugee children in Lebanon.83

General food distribution

Thirty-four publications reported on GFD in conflict settings either through take home rations or hot cooked meal provision, or through cash or vouchers for food.23 27–30 32 33 41–44 46 54 55 57–59 61 63 69 71 75 77 81 82 90 91 93–95 97 106 112 113 Of these, eight were published between years 1990 and 2000,23 29 32 33 44 54 58 77 five between 2001 and 201028 46 55 59 75 and 21 between 2011 and 2018.27 30 41–43 57 61 63 69 71 81 82 90 91 93–95 97 106 112 113 GFD in form of food vouchers/cash assistance was given from the year 2011 onwards.27 41 43 82 91 95 106 112 113 Four publications reported on specific food rations for pregnant women to meet extra nutrient requirements,30 44 59 71 delivered by staff from UN agencies. Six publications reported on food distribution interventions targeted at children under-five years of age,23 27 31 32 46 64 and one targeted at women of reproductive age,63 with food rations distributed at health centres, supplementary feeding centres or distribution points in the market. One publication reported on food rations delivered to everyone over the age of 15 years by NGO/UN staff in Uganda,69 but the delivery mode was unreported.

In publications describing those GFD interventions where food rations were provided to households, the delivery personnel involved were either NGO staff28 41 61 or were either not reported.32 In rural areas of northern Lebanon, community volunteers delivered hot meals multiple times per week to Syrian refugees through community kitchens.81 Two studies reported on delivering food rations to survivors of sexual and gender based violence, one study also provided ‘safe shelter boundaries’ during conflict to survivors of sexual and gender based violence.78 94 Only one record was found where military personnel distributed food rations, in Iraq, but delivery mode was unreported.33

The provision of food through cash or voucher distribution was reported in 10 publications.27 42 43 82 91 95 97 106 112 113 These included IDPs or refugees living in camps/dispersed settings in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan, Syria, Central African Republic, Kenya and South Sudan and delivered by NGO/UN through print or electronic media (via mobile app/market-based ATMs) at homes/market/NGO clinics.

SAM/MAM treatment and management

A total of 19 publications reported on interventions to treat acute malnutrition on an inpatient basis.24 25 40 49 60 66 73 79 80 83 85 89 98 100–102 104 109 111 Of these publications, only two were published between 2001 and 2010,40 66 and 17 between 2011 and 2018.24 25 49 60 73 79 80 83 85 89 98 100–102 104 109 111 All nutrition interventions were conducted by local Ministry of Health (MOH) in collaboration with UN agencies/NGOs. The majority of the SAM treatment interventions included a combination of inpatient and community-based care of under-five children depending on the severity of malnutrition.25 66 73 79 83 85 102 104 111 SAM patients with complications were given inpatient care either in hospitals or therapeutic feeding centres, followed by provision of ready to use therapeutic food (RUTF), BP100 Plumpy nuts or F100 milk retrieved periodically from outpatient clinics in some cases, and onsite feeding at supplementary/outpatient therapeutic feeding centres in other cases.25 49 60 66 80 83 One study reported on mixing of RUTF with nutrient dense product (NRG-5) with milk or juice to mask up the foul taste of RUTF.83 The four main elements of the community-based management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programme were management of MAM, management of SAM, inpatient management for SAM with medical complications and community outreach.79 85 104 The studies on CMAM programme were mostly published after the year 2015. In some conflict settings where pre-existing healthcare system was absent or unable to respond, temporary services and structures were established by UN agency/NGOs such as inpatient stabilisation centres for IDPs in South Sudan.102

Supplementary feeding

Twenty publications reported on supplementary feeding of which three were published between years 1990 and 2000,31 74 76 four between 2001 and 201037 56 64 65 and 13 between 2011 and 2018.26 49 73 79 80 83 89 93 99 101 102 104 109 Seven included publications reported on the delivery of blanket supplementary feeding (BSF) interventions in conflict settings to prevent acute malnutrition.31 37 49 74 93 99 101 BSF was provided in addition to general food rations in three publications,37 49 93 while one publication reported on distribution of healthy baked snacks as thyme rolls and almond muffins,99 and one more publication reported on blanket distribution of ready to use supplementary food (RUSF) to internally displaced under five children as well as postnatal mothers in Syria through community-based clinics.101 Nearly all BSF programmes targeted children aged 6–59 months, predominantly in camp settings, but two publications reported BSF targeted at school-aged refugee children residing outside of camps and from the host community, in Somalia93 and Lebanon.99

Thirteen included publications reported on targeted supplementary feeding (TSF) interventions, aimed at treating MAM and preventing SAM.26 56 64 65 73 76 79 80 83 89 102 104 109 TSF was provided as a part of programme102 104 or as a standalone provision of RUSF,83 89 fortified local food80 or Super Cereal Plus.80 109 Most TSF interventions also focused on children aged 6–59 months in camp settings.

The majority of both blanket and TSF interventions were delivered either in supplementary feeding centre (SFC), in health centres or at distribution points in markets,26 31 37 49 56 64 65 76 79 80 83 102 mostly by CHWs and/or formal health workers,26 37 49 56 64 65 73 76 83 104 or by NGO/UN staff.74 80 93 99 101 109

Nutrition education

Twenty two publications reported on nutrition-focused education delivered alone or as a component of other nutrition interventions in conflict settings.34 37 38 40 43 56 62 67 68 80 83 86 89 92 98 99 101 104 105 107 110 111 Of these, two studies were published between years 1990 and 2000,34 62 four between 2001 and 2010,37 40 56 67 and 16 between 2011 and 2018.38 43 68 80 83 86 89 92 98 99 101 104 105 107 110 111 The majority of education initiatives focused on infant formula use, IYCF practices, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) promotion or on continued feeding of children during illness.37 40 43 56 62 67 68 80 83 86 89 92 98 99 101 104 105 107 110 111 One publication reported on educating women about infectious disease management among under-five children,34 and another on an emergency response during konzo outbreak where food safety-related education was provided.38 All nutrition education interventions were conducted in hospitals, health centres or NGO clinics by NGO staff, health workers or CHWs.

Nutrition intervention coverage and effectiveness

Only eight publications23 26 49 64 73 76 89 100 reported on the coverage23 26 49 64 76 (table 2) or the effectiveness49 64 73 76 89 100 (table 3) of delivered nutrition interventions. Further 11 publications failed to report data on coverage and provided data in numbers only.34 46 83 86 88 90–92 102 104 106 Two publications reported on the outcomes of treatment programmes for SAM, reporting only on performance indicators from Yemen, and Lebanon based therapeutic feeding programmes.89 100 When we compared the results with Sphere recommendations, we found SFP conducted from March to September 1994 in Burundi based SFCs reported lower coverage (29.6%) than the recommended (>50%).76 The SAM treatment performance indicators also reported lower recovery rates (66.8%) than the recommended (>75%).76 Defaulters were also noted higher in proportion (29.2%) than the recommended (<15%) in Burundi.76 The same SFP reported coverage in Liberia, and DRC more than the minimum standard.76 The Bandim health project and humanitarian assistance in Guinea Bissau during 1998 and 1999 treated SAM children through community, and outreach approach.64 They also achieved almost minimum coverage (57%), and recovery rate (59.9%), while the defaulters were reported higher than the minimum (32%).64 Another reported coverage of similar programme in 1998 among refugees and non-displaced residents of Guinea Bissau23 and showed 87% coverage among refugees and 91% among residents.23 The same study reported on food distribution, which reported higher coverage among refugees (41%) as compared with non-displaced residents (16%).23 A camp based BSF and MNS programme implemented during 2008 and 2010 in Nepal reported above minimum coverage ranged between 95% and 98%.26 A large scale community-based nutritional status assessment at mobile clinics during the Nutrition Rehabilitation Programme in Sri Lanka also achieved high coverage (97.3% in camps; 86% in urban and rural areas) than the Sphere recommendations.49 This programme also reported higher recovery rate for SAM treatment using TSF alone (90%) and in combination of RUTF (94%) as compared with the treatment with only RUTF (42.5%).49 All these three treatments when used to treat MAM children, recovery rates were noted lower ranged between 32% and 50%.49 When all three SAM treatments were compared, the proportion of defaulters were noted lowest (0.9%) in the combined treatment with TSF and RUTF.49 The default rate for MAM treatment was unreported.49 Another large scale camp based feeding programme at SFCs in Tanzania and Kenya treated SAM children with recovery rates of 75%, and 78%, respectively.73 While the MAM recovery rates were reported as 76% in Tanzania, and 92% in Kenya.73 Within Yemen based TFP, the increase in recovery rates and transfers to OTP was likely due to the improved quality of care brought about by the training programme.89

Table 2.

Reported coverage of nutrition interventions targeted to children under-five in conflict settings

| Programme type; country (programme duration) |

Intervention component for which coverage was measured | Delivery sites | Delivery personnel | Setting | Year coverage measured | Target population (N) | % (n) of target population covered |

| District Nutrition Rehabilitation Programme; Sri Lanka (2007–2009)49 |

Nutritional status assessment of children aged 6–59 months | Health clinics, weighing posts | Health workers | Camp | 2007 | 3638 | 97.3 (3538) |

| Camp, non-camp | 2007 | 38 953 | 85.9 (33 461) | ||||

| Camp, non-camp | 2008 | 43 221 | 85.8 (37 090) | ||||

| Refugee Nutrition Programme; Nepal (2008–2010)26 |

Micronutrient powder for home fortification (Vita-Mix-It) | Health centre/clinic | Health and nutrition workers | Camp | 2010 | 569 | 97.2 (557) |

| Vitamin A supplements | Camp | 2010 | 569 | 97.7 (556) | |||

| Deworming | Camp | 2010 | 569 | 95.1 (541) | |||

| Supplementary Feeding Programme; Liberia (1993–1994)76 |

Targeted supplementary feeding | Facility-based supplementary feeding centres | Community health workers | Non-camp | 1994 | – | 69.9 |

| Supplementary Feeding Programme; Burundi (March–September 1994)76 |

Targeted supplementary feeding | Facility-based and community-based supplementary feeding centres | Community health workers | Non-camp | 1994 | – | 29.6 |

| Supplementary Feeding Programme; DRC (1994–1995)76 |

Targeted supplementary feeding | Community-based supplementary feeding centres | Community health workers | Camp | 1994 | – | 93.7 |

| The Bandim Health Project; Guinea-Bissau (1998–1999)64 |

Targeted supplementary feeding, micronutrient supplementation | Health centres, households | Health workers | Rural | 1999 | 433 | 57 (247) |

| International Committee for the Red Cross Food Distribution; Guinea-Bissau (June 1998)23 |

Targeted supplementary feeding to refugees | Households | NGO staff | Non-camp | 1998 | 299 | 41 (123) |

| Targeted supplementary feeding to residents (not displaced) | 99 | 16 (16) | |||||

| The Bandim Health Project; Guinea-Bissau (July and August 1998)23 |

Targeted supplementary feeding to refugees | Households | NGO staff | Non-camp | 1998 | 98 | 87 (85) |

| Targeted supplementary feeding to residents (not displaced) | 267 | 91 (243) |

DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; NGO, non-governmental organisation.

Table 3.

Reported effectiveness of treatment interventions for acute malnutrition among children under-five in conflict settings

| Outcome | Country | Setting | Intervention components | Delivery personnel | Delivery site |

Children treated N |

Recovered n (%) |

Defaulted n (%) |

Died n (%) |

| SAM treatment | Sri Lanka49 | Camp | Therapeutic feeding including F75, F100 and RUTF (BP-100) in hospital and RUTF (BP-100) as outpatient; deworming; vitamin A supplementation | Paediatricians, health workers | Hospital, health centre | 230 | 216 (93.9) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| Sri Lanka49 | Camp, non-camp | Targeted supplementary feeding (HEBs) | 1065 | 958 (89.9) | 51 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |||

| Sri Lanka49 | Camp, non-camp | Blanket supplementary feeding (CSB) (no therapeutic or targeted supplementary feeding) | 306 | 130 (42.5) | 86 (28.1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Kenya73 | Camps | Therapeutic feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 3014 | 2351 (78) | 151 (5) | 181 (6) | |

| Tanzania73 | Camps | Therapeutic feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 403 | 303 (75) | 41 (10) | 17 (4) | |

| Yemen89 | Camps, rural | Therapeutic feeding | Doctors, nurses, medical students | Hospital-based therapeutic feeding centre | 1103 | 78 (7.1) | 196 (18) | 60 (5.4) | |

| MAM treatment | Sri Lanka49 | Camp | Targeted supplementary feeding (HEBs), blanket supplementary feeding (CSB) | Health workers | Health centre | 753 | 380 (50.5) | NR | 0 (0) |

| Sri Lanka49 | Camp, non-camp | Targeted supplementary feeding (HEBs), blanket supplementary feeding (CSB) | 6970 | 3110 (44.6) | NR | 0 (0) | |||

| Sri Lanka49 | Camp, non-camp | Blanket supplementary feeding (no targeted supplementary feeding) | 4857 | 1571 (32.3) | NR | 0 (0) | |||

| Kenya73 | Camps | Targeted supplementary feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 37 741 | 34 722 (92) | 1737 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Tanzania73 | Camps | Targeted supplementary feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 2158 | 1641 (76) | 195 (9) | 0 (0) | |

| GAM treatment | Guinea Bissau64 | Camps | Targeted supplementary feeding | Health workers | Health centre | 247 | 148 (59.9) | 70 (32) | 2 (0.9) |

| Lebanon100 | Camps, rural | Therapeutic feeding | Doctors, nurses, CHWS | Hospital, health centre |

519 | 412 (79.2) | 24 (4.6) | NR | |

| Liberia76 | Rural | Targeted supplementary feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 12 259 | 9967 (81.3) | 1923 (15.7) | 50 (0.4) | |

| Burundi76 | Rural | Targeted supplementary feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 9197 | 6144 (66.8) | 2682 (29.2) | 63 (0.7) | |

| DRC76 | Camps | Targeted supplementary feeding | CHWs | SFCs | 18 767 | 14 826 (79) | 2139 (11.4) | 33 (0.2) |

CHWs, community health workers; CSB, corn–soya blend; GAM, global acute malnutrition; HEBs, high-energy biscuits; MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; RUTF, ready to use therapeutic food; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; SFCs, supplementary feeding centres.

Barriers to and facilitators of nutrition intervention delivery

Specific delivery barriers that we identified from the literature are presented in table 4. Insufficient resources and ongoing insecurity were key barriers recurring in the literature. Multiple publications reported on supply shortages of important commodities, especially of RUTF and micronutrient supplements, as well as insufficient human resources and limited funding. Humanitarian actors faced multiple security and accessibility issues due to ongoing conflict, collapsed healthcare systems, and damaged infrastructure, while limited inter-cluster coordination and lack of coordination between humanitarian partners posed additional delivery challenges. Population movements in and out of camps made it difficult to reach vulnerable populations and provide follow-up care. Gender bias and negative sociocultural practices (genital mutilation, early marriages, child labour) also hindered in intervention delivery. Outcome assessment by unskilled staff, security concerns, reporting errors, small sample size, and less rigorous methods resulted in poor reporting of coverage and effectiveness outcomes in the included studies.

Table 4.

Nutrition intervention barriers and facilitators

| Themes | Specific examples | Countries | Interventions | |

| Barriers | Insufficient coordination | Limited inter-cluster coordination88 102 106 108 Lack of cross border cooperation67 |

Kenya,106 Somalia,88 South Sudan,102 Tanzania,67 Uganda108 | Nutrition assessment,67 88 102 108 breast feeding and appropriate IYCF,67 88 disease prevention and management,67 108 micronutrient supplementation,108 general food distribution,106 SAM/MAM treatment,102 supplementary feeding102 |

| Insufficient resources | Inadequate/irregular supplies of commodities39 41 48 49 77 82 83 98 101 112 Logistical constraints29 79 99 100 112 Limited human resources83 89 Limited funding42 51 54 60 78 91 95 |

Burundi,48 Somalia,39 Jordan,41 51 79 95 Syria,41 42 101 Sri Lanka,49 Bosnia and Herzegovina,54 77 Lebanon,82 83 91 99 100 Yemen,89 South Sudan,98 112 Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC),29 Uganda,60 Palestine78 | Nutrition assessment,29 49 51 77 79 83 100 101 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,48 49 78 98 disease prevention and management,29 39 49 100 micronutrient supplementation,49 83 general food distribution,29 41 42 54 77 82 91 95 112 SAM/MAM treatment,49 60 79 83 89 100 101 supplementary feeding,49 79 83 89 99 101 nutrition education83 89 98 99 101 |

|

| Ongoing conflict situation | Security and access concerns29 41 60 80 84 89–91 94 101 102 | Lebanon,91 South Sudan,102 Yemen,89 Afghanistan,84 Syria,101 Jordan,41 80 DRC,29 Uganda,60 Colombia94 | Nutrition assessment,29 84 101 102 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,80 disease prevention and management,29 micronutrient supplementation,101 general food distribution,29 41 91 94 SAM/MAM treatment,60 80 89 101 102 supplementary feeding,89 101 102 nutrition education80 89 101 | |

| Limited population adherence | Limited cooperation from beneficiaries63 80 86 92 93 107 110 111 Population movement76 102 Gender bias or negative socio-cultural practices93 |

South Sudan,102 Jordan,80 92 Lebanon,86 110 DRC,76 102 Somalia,93 Burundi,76 Liberia,76 Kenya,63 Yemen107 | Nutrition assessment,92 102 107 111 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,80 86 92 110 disease prevention and management,76 107 micronutrient supplementation,63 107 general food distribution,63 93 SAM/MAM treatment,80 102 111 supplementary feeding,80 93 102 nutrition education80 86 92 107 110 111 |

|

| Poor outcome reporting | Unskilled staff38 Reporting errors62 73 Small sample size/Sampling bias42 53 Security issues42 |

Cameroon,38 Kenya,73 Pakistan,62 Nigeria,53 Syria,42 Tanzania73 | Nutrition assessment,53 73 disease prevention and management62 73 general food distribution,42 SAM/MAM treatment,73 supplementary feeding,73 nutrition education38 62 | |

| Facilitators | Effective monitoring system | Established nutrition surveillance system64 65 83–85 101 109 112 | Lebanon,83 Sudan,85 Kenya,64 Guinea-Bissau,64 65 Afghanistan,84 Syria,101 Jordan,109 South Sudan112 | Nutrition assessment,83 84 101 109 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,64 65

micronutrient supplementation,64 65 83 101

general food distribution,64 112 SAM/MAM treatment,83 85 101 109 supplementary feeding,65 83 101 109 nutrition education83 101 |

| Multi-sector programming | Inter-Cluster Coordination Group (ICCG Somalia)88 Nutrition cluster in partnership with the health and WASH clusters25 88 Integration of services through public primary healthcare (PHC) centres31 39 40 48 49 66 Nutrition services integration into public education system99 |

Burundi,48 Somalia,39 88 Sri Lanka,49 Pakistan,25 Ethiopia,31 Guinea-Bissau,40 DRC,66 Lebanon99 | Nutrition assessment,25 49 88 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,25 48 49 66 88 disease prevention and management,25 39 40 49 micronutrient supplementation,31 40 49 66 SAM/MAM treatment,25 40 49 supplementary feeding,31 49 66 99 nutrition education40 99 | |

| Adoption of guidelines/evidence-based approaches | National plan for scaling up CMAM79 85 104 ‘Scaling Up Nutrition’ movement43 |

Jordan,79 Sudan,85 Ethiopia,85 104 Central African Republic43 | Nutrition assessment,79 104 micronutrient supplementation,79 general food distribution,43 SAM/MAM treatment,79 85 104 supplementary feeding,79 104 nutrition education43 104 | |

| Advocacy and social mobilisation | Established village development committees108 Community networking47 92 Community mobilisation38 70 75 79 86 87 100 105 Communication for Development (C4D) approach103 |

Uganda,108 Jordan,47 79 92 Cameroon,38 Zambia,70 75 Angola,75 Afghanistan,75 Lebanon,86 87 100 South Sudan,105 Mali103 | Nutrition assessment,79 87 92 100 108 breastfeeding and appropriate IYCF,47 86 92 105 disease prevention and management,100 108 food fortification,70 75 micronutrient supplementation,79 100 108 general food distribution,75 SAM/MAM treatment,79 100 supplementary feeding,79 nutrition education38 86 92 105 | |

| Capacity building of workforce | Task shifting/sharing85 Training of trainers68 85 89 |

Sudan,85 Yemen,89 South Sudan68 | SAM/MAM treatment,85 89 supplementary feeding,89 nutrition education68 89 | |

| Innovative technology use | Biometric technology for mobile phone cash transfer (M-PESA)91 95 | Lebanon,91 Jordan95 | Food vouchers/cash provision91 95 |

CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; SAM/MAM, severe acute malnutrition/moderate acute malnutrition; WASH, water, sanitation and hygiene.

Effective social mobilisation, monitoring and surveillance, and integration of nutrition services into other sectors were key delivery facilitators (table 4). Local community members, religious leaders and established community networks were leveraged to effectively deliver nutrition interventions. The establishment of nutrition surveillance systems was found to be effective in strengthening local monitoring systems. A multi-sectoral programming approach was reported in multiple instances, with the nutrition cluster collaborating with the health and WASH clusters to facilitate delivery of comprehensive nutrition-specific and sensitive interventions, and interventions being integrated into local healthcare systems. Some national-level programmes adopted evidence-based guidelines to scale up nutrition interventions through community-based approaches, especially for the acute malnutrition. There were several examples of intensive training and capacity building of workers, as well as task shifting, implemented to improve coverage of acute malnutrition and IYCF interventions.

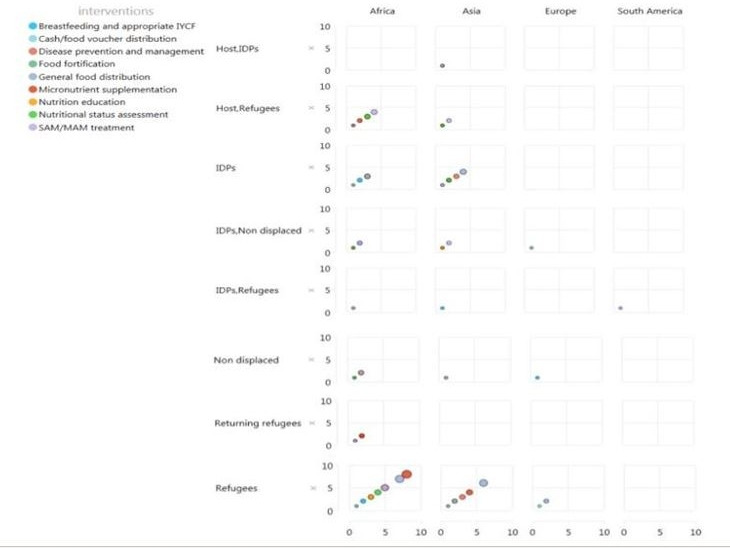

Discussion

We identified 91 publications from 1990 and 2018 that described the delivery of nutrition interventions to women and children affected by armed conflict in LMICs, mostly reported in African region. Less than half of the included publications reported on research findings, and nearly 40% were sourced from the grey literature. Studies published between year 1990 and 2000, majorly focused on GFD and disease prevention and management. Studies published between year 2001 and 2010 also focused on disease prevention and management and on micronutrient supplementation, and studies published after 2011 focused on nutrition assessment, GFD and SAM/MAM treatment. GFD, micronutrient supplementation and nutrition assessment were the most frequently reported interventions, with most publications reporting on intervention delivery to refugee populations in camp settings and using community-based approaches (figure 4).114 Limited data on intervention coverage or effectiveness were captured from the included literature, preventing inferences to be drawn about how these vary by different delivery approaches in conflict settings. Very rarely were quantitative estimates reported, but delivery mechanisms and barriers and facilitators were more comprehensively described in the grey compared with the indexed literature. Insufficient resources, including nutritional commodity shortages, security concerns due to ongoing conflict, limited inter-cluster coordination, and difficulty accessing and following beneficiaries up due to population movements and sometimes limited cooperation were key delivery barriers. Community advocacy and social mobilisation, effective monitoring, and integration of nutrition and other sector interventions and services were key delivery facilitators.

Figure 4.

Summary of evidence. IDP, internally displaced person; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; SAM/MAM, severe acute malnutrition/moderate acute malnutrition.

Our results yield important insights about the nutrition delivery and important gaps. It is evident that much of the documentation of nutrition interventions and programmes implemented in conflict and likely in emergency settings more generally, exists in the grey literature generated by UN agencies, NGOs and other humanitarian implementers actively working in the field rather than from government reports and indexed literature. Second, the limited number of included studies and variation in population behaviour and in context such as country, underlying health system, disease outbreak, and type and severity of conflict has curtailed us from studying the impact of nutrition intervention on women in conflict setting in greater depth.

In addition, much of the literature focused on nutrition interventions delivered to camp-based refugees, with relatively little reported on populations displaced or non-displaced populations. It is difficult to know whether the lack of reporting on non-camp and non-displaced populations reflects actual nutrition intervention delivery patterns on the ground, or rather a failure to document.

With respect to the types of interventions, the relatively higher frequency of reporting on food distribution and the management of acute malnutrition is understandable, given the high prevalence of food insecurity and the high morbidity and mortality burden of malnutrition. It was somewhat surprising to find relatively little on the delivery of IYCF interventions, though there were some examples of innovative practices to provide safe spaces for women to breast feed. Moreover, we captured just as many publications reporting on infant formula distribution as on breastfeeding promotion interventions.

We also found that many publications reported on nutrition intervention delivery at household level or through outreach approaches. We also note that the CMAM has been adopted as national policy by several governments including Ethiopia, Jordan and Sudan. Given these experiences, the humanitarian nutrition sector may be particularly well-placed to further innovate and test community-based approaches that might overcome or circumvent the specific implementation challenges across sectors.

In context to barriers of delivery; destruction of health facilities, targeted attacks on facilities and health workers, as well as disruption of supply chains were key issues, which further added to the existing weak governance and healthcare system infrastructure. Thus, the actors should identify effective strategies for delivering interventions through planning which must addresses the security concerns of health service providers and beneficiaries. Moreover, gathering support and acceptance from local influencers and communities, including local authorities, appears to be critical, while maintaining the perception of their impartiality and neutrality.

Finally, literature reports on multi-sectoral programming approach with the nutrition cluster collaborating with the health and WASH clusters, but has failed to report its integration with early childhood development and mental health, which is an emerging issue. Moreover, there is no data on gender equality and social inclusion. Thus, future studies should untake gender analyses, to investigate the gendered differences in access, needs and uptake of healthcare services.

This systematic review of the literature is the first, to our knowledge, to focus on the delivery of nutrition interventions in armed conflict settings, and thus makes a novel and important contribution to the field. However, in addition to the limitations inherent in the existing literature itself, discussed above, we must also acknowledge that by restricting our review only to publications published in English, and by undertaking a comprehensive but not exhaustive search of the grey literature, we have inevitably excluded other relevant publications that may have provided different information from what we have captured presently.

Conclusion

There is very little information on achieved coverage or effectiveness of nutrition interventions delivered in conflict settings; more (and more rigorous) evaluation of different delivery approaches is needed, including outside of camps and for preventive as well as curative nutrition interventions. The humanitarian nutrition sector may be particularly well-placed to advance the field with respect to community-based intervention delivery in conflict contexts, and has effective, existing networks to widely disseminate the important evidence that it could generate.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @fjsepi

Contributors: All authors contributed in writing this manuscript.

Funding: Aga Khan University has received funding from the Family Larsson Rosenquist Foundation. As coordinator of the Bridging Research & Action in Conflict Settings for the Health of Women & Children (BRANCH) Consortium, the SickKids Centre for Global Child Health has received funding for research activities from the International Development Research Centre (108416-002 and 108640-001), the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) (QZA-16/0395), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1171560) and UNICEF (PCA 20181204).

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request. Data extracted from publications retrieved from the indexed and grey literature are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was not required, as this paper is a systematic review of publically available, published literature.

References

- 1.Ploughshares P. Armed conflict 2016, 2018. Available: http://ploughshares.ca/armed-conflict/defining-armed-conflict/

- 2.O'cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008;13:92–8. 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Communicable diseases and severe food shortage: who technical note, October 2010: World Health organization, 2010. Available: https://www.usaid.gov/global-health/health-areas/nutrition/technical-areas/nutrition-emergencies-technical-guidance-brief [PubMed]

- 4.OCHA . Global humanitarian overview United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affair; 2018. https://www.unocha.org/publication/global-humanitarian-overview/global-humanitarian-overview-2018 [Accessed 13 July 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF . UNICEF’s approach to scaling up nutrition United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). New York: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2015. https://sites.unicef.org/nutrition/files/Unicef_Nutrition_Strategy.pdf [Accessed 20 August 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffey MF, Waldman RJ, Blanchet K, et al. Delivering health and nutrition interventions for women and children in different conflict contexts: a framework for decision making on what, when, and how. The Lancet 2021;397:543–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00133-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchet K, Sistenich V, Ramesh A. An evidence review of research on health interventions in humanitarian crises. London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Harvard School of Public Health, Overseas Development Institute, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts B, Guy S, Sondorp E, et al. A basic package of health services for Post-Conflict countries: implications for sexual and reproductive health services. Reprod Health Matters 2008;16:57–64. 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31347-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sphere Association . The sphere Handbook: humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. Geneva, Switzerland: Sphere Association; 2018. www.spherestandards.org/handbook [Accessed 13 December 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain M, Choudhury N, Adib Binte Abdullah K, Abdullah K, et al. Evidence-Based approaches to childhood stunting in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2017;102:903–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamali M, Munyuzangabo M, Siddiqui FJ, et al. Delivering mental health and psychosocial support interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002014. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munyuzangabo M, Khalifa DS, Gaffey MF, et al. Delivery of sexual and reproductive health interventions in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002206. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aboubaker S, Evers ES, Kobeissi L, et al. The availability of global guidance for the promotion of women's, newborns', children's and adolescents' health and nutrition in conflicts. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002060. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Als D, Meteke S, Stefopulos M, et al. Delivering water, sanitation and hygiene interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002064. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain RP, Meteke S, Gaffey MF, et al. Delivering trauma and rehabilitation interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e001980. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meteke S, Stefopulos M, Als D, et al. Delivering infectious disease interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e001967. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munyuzangabo M, Gaffey MF, Khalifa DS, et al. Delivering maternal and neonatal health interventions in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2021;5:e003750 https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/Suppl_1/e003750 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah S, Munyuzangabo M, Gaffey MF, et al. Delivering non-communicable disease interventions to women and children in conflict settings: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e002047. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the prisma statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarivate . Endnote [program]. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khorram O, Khorram N, Momeni M, et al. Maternal undernutrition inhibits angiogenesis in the offspring: a potential mechanism of programmed hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;293:R745–53. 10.1152/ajpregu.00131.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaby P, Gomes J, Fernandes M, et al. Nutritional status and mortality of refugee and resident children in a non-cAMP setting during conflict: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau. BMJ 1999;319:878. 10.1136/bmj.319.7214.878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altmann M, Suarez-Bustamante M, Soulier C, et al. First wave of the 2016-17 cholera outbreak in hodeidah city, Yemen - ACF experience and lessons learned. PLoS Curr 2017;9. 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.5c338264469fa046ef013e48a71fb1c5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bile KM, Hafeez A, Kazi GN, et al. Protecting the right to health of internally displaced mothers and children: the imperative of inter-cluster coordination for translating best practices into effective participatory action. East Mediterr Health J 2011;17:981–9. 10.26719/2011.17.12.981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bilukha O, Howard C, Wilkinson C, et al. Effects of multimicronutrient home fortification on anemia and growth in Bhutanese refugee children. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:264–76. 10.1177/156482651103200312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilukha O, Jayasekaran D, Burton A. Nutritional status of women and child refugees from Syria — Jordan, April–May 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2014;63:638–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borrel A, Taylor A, McGrath M, Hormann E, et al. From policy to practice: challenges in infant feeding in emergencies during the Balkan crisis. Disasters 2001;25:149–63. 10.1111/1467-7717.00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callaghan MP, Immerman B. Phs mission to Goma, Zaire. Public Health Rep 1995;110:95–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrara VI SW, Lee SJ, et al. Longer exposure to a new refugee food ration is associated with reduced prevalence of small for gestational age: results from 2 cross-sectional surveys on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:1382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centre for Disease Control . International notes update: Health and nutritional profile of refugees - Ethiopia, 1989- 1990. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1990;39:707–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centre for Disease Control . Health and nutritional status of Liberian refugee children, 1990. Weekly Epidemiological Record 1991;40:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centre for Disease Control . Public health consequences of acute displacement of Iraqi Citizens—March-May 1991. JAMA 1991;266:633–4. 10.1001/jama.1991.03470050031003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Implementation of health initiatives during a cease-fire--Sudan, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1995;44:433–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charchuk R, Houston S, Hawkes MT. Elevated prevalence of malnutrition and malaria among school-aged children and adolescents in war-ravaged South Sudan. Pathog Glob Health 2015;109:395–400. 10.1080/20477724.2015.1126033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhry AB, Hajat S, Rizkallah N, et al. Risk factors for vitamin A and D deficiencies among children under-five in the state of Palestine. Confl Health 2018;12:13. 10.1186/s13031-018-0148-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung E, Mutahar R, Assefa F, et al. An epidemic of scurvy in Afghanistan: assessment and response. Food Nutr Bull 2003;24:247–55. 10.1177/156482650302400303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ciglenečki I, Eyema R, Kabanda C, et al. Konzo outbreak among refugees from central African Republic in eastern region, Cameroon. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011;49:579–82. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collins S, Myatt M, Golden B. Dietary treatment of severe malnutrition in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:193–9. 10.1093/ajcn/68.1.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colombatti R, Coin A, Bestagini P, et al. A short-term intervention for the treatment of severe malnutrition in a post-conflict country: results of a survey in guinea Bissau. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:1357–64. 10.1017/S1368980008003297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doocy S, Sirois A, Anderson J, et al. Food security and humanitarian assistance among displaced Iraqi populations in Jordan and Syria. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:273–82. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doocy S, Tappis H, Lyles E, et al. Emergency food assistance in northern Syria: an evaluation of transfer programs in Idleb Governorate. Food Nutr Bull 2017;38:240–59. 10.1177/0379572117700755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dozio E, Peyre L, Morel SO, et al. Integrated psychosocial and food security approach in an emergency context. Intervention 2016;14:257–71. 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duckett J. Guidelines for dietary supplementation of pregnant women in a Rwandan refugee cAMP. J R Army Med Corps 1996;142:13–14. 10.1136/jramc-142-01-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dzumhur Z, Zec S, Buljina A, et al. Therapeutic feeding in Sarajevo during the war. Eur J Clin Nutr 1995;49 Suppl 2:S40–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eltom AA. Internally displaced people—refugees in their own country. The Lancet 2001;358:1544–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06589-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fander G, Beck N, Johan H, et al. PS-319a xtremely low exclusive breast feeding (EBF) rate among the Syrian refugee communities In Jordan. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:A226.2–A226. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307384.618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fournier AS, Mason F, Peacocke B, et al. The management of severe malnutrition in Burundi: an NGO's perspective of the practical constraints to effective emergency and medium-term programmes. Disasters 1999;23:343–9. 10.1111/1467-7717.00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jayatissa R, Bekele A, Kethiswaran A, et al. Community-Based management of severe and moderate acute malnutrition during emergencies in Sri Lanka: challenges of implementation. Food Nutr Bull 2012;33:251–60. 10.1177/156482651203300405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kassim IAR, Ruth LJ, Creeke PI, et al. Excessive iodine intake during pregnancy in Somali refugees. Matern Child Nutr 2012;8:49–56. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00259.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khatib IM, Samrah SM, Zghol FM. Nutritional interventions in refugee camps on Jordan’s eastern border: assessment of status of vulnerable groups. East Mediterr Health J 2010;16:187–93. 10.26719/2010.16.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar V, Chaudhury L, Rathore R. An epidemiological analysis of outbreak of measles in a medical relief cAMP. Health and Population-Perspectives and Issues 2003;26:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leidman E, Tromble E, Yermina A, et al. Acute malnutrition among children, mortality, and humanitarian interventions in conflict-affected regions — Nigeria, October 2016–March 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:1332–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6648a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leus X. Humanitarian assistance: technical assessment and public health support for coordinated relief in the former Yugoslavia. World Health Statistics Quarterly 1993;46:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lopriore C, Guidoum Y, Briend A, et al. Spread fortified with vitamins and minerals induces catch-up growth and eradicates severe anemia in stunted refugee children aged 3–6 Y. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:973–81. 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magoni M, Jaber M, Piera R. Fighting anaemia and malnutrition in Hebron (Palestine): impact evaluation of a humanitarian project. Acta Trop 2008;105:242–8. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahomed Z, Moolla M, Motara F, et al. A Somalia mission experience. S Afr Med J 2012;102:659. 10.7196/SAMJ.5970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Malfait P, Moren A, Malenga G. Outbreak of pellagra among Mozambican refugees - Malawi, 1990. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 1991;40:209–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGready R, Simpson JA, Cho T, et al. Postpartum thiamine deficiency in a Karen displaced population. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:808–13. 10.1093/ajcn/74.6.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris J, Jones L, Berrino A, et al. Does combining infant stimulation with emergency feeding improve psychosocial outcomes for displaced mothers and babies? A controlled evaluation from Northern Uganda. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2012;82:349–57. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01168.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morseth MS, Grewal NK, Kaasa IS, et al. Dietary diversity is related to socioeconomic status among adult Saharawi refugees living in Algeria. BMC Public Health 2017;17:621. 10.1186/s12889-017-4527-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy HH, Bari A, Molla AM, et al. A field trial of wheat-based oral rehydration solution among Afghan refugee children. Acta Paediatr 1996;85:151–7. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb13982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ndemwa P, Klotz CL, Mwaniki D, et al. Relationship of the availability of micronutrient powder with iron status and hemoglobin among women and children in the Kakuma refugee cAMP, Kenya. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:286–91. 10.1177/156482651103200314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nielsen J, Valentiner-Branth P, Martins C, et al. Malnourished children and supplementary feeding during the war emergency in Guinea-Bissau in 1998–1999. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1036–42. 10.1093/ajcn/80.4.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nielsen J, Benn CS, Balé C, et al. Vitamin A supplementation during war-emergency in Guinea-Bissau 1998–1999. Acta Trop 2005;93:275–82. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Renzaho A, Renzaho C. In the shadow of the volcanoes: the impact of intervention on the nutrition and health status of Rwandan refugee children in Zaire two years on fromthe exodus. Nutrition & Dietetics 2003;60:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rutta E, Gongo R, Mwansasu A, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a refugee cAMP setting in Tanzania. Glob Public Health 2008;3:62–76. 10.1080/17441690601111924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sami S, Kerber K, Tomczyk B, et al. “You have to take action”: changing knowledge and attitudes towards newborn care practices during crisis in South Sudan. Reprod Health Matters 2017;25:124–39. 10.1080/09688080.2017.1405677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schramm S. Nutritional status among adults in a post-conflict area Northern Uganda: are humanitarian assistance programmes creating disparities in health? Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:S182. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Seal A, Kafwembe E, Kassim IAR, et al. Maize meal fortification is associated with improved vitamin A and iron status in adolescents and reduced childhood anaemia in a food aid-dependent refugee population. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:720–8. 10.1017/S1368980007001486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stuetz W, Carrara V, Mc Gready R, et al. Impact of food rations and supplements on micronutrient status by trimester of pregnancy: cross-sectional studies in the Maela refugee cAMP in Thailand. Nutrients 2016;8:66. 10.3390/nu8020066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Talley L, Woodruff BA, Seal A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of stainless steel cooking pots in reducing iron-deficiency anaemia in food aid-dependent populations. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:107–15. 10.1017/S1368980009005254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tappis H, Doocy S, Haskew C, et al. United nations high commissioner for refugees feeding program performance in Kenya and Tanzania: a retrospective analysis of routine health information system data. Food Nutr Bull 2012;33:150–60. 10.1177/156482651203300209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Toole MJ, Bhatia R. A case study of Somali refugees in Hartisheik a cAMP, eastern Ethiopia: health and nutrition profile, July 1988-June 1990. J Refug Stud 1992;5:313–26. 10.1093/jrs/5.3-4.313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van den Briel T, Cheung E, Zewari J, et al. Fortifying food in the field to boost nutrition: case studies from Afghanistan, Angola, and Zambia. Food Nutr Bull 2007;28:353–64. 10.1177/156482650702800312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vautier F, Hildebrand K, Dedeurwaeder M, et al. Dry supplementary feeding programmes: an effective short-term strategy in food crisis situations. Tropical Medicine and International Health 1999;4:875–9. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Watson F, Kulenovic I, Vespa J. Nutritional status and food securtiy: winter nutrition monitoring in Sarajevo1993-1994. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1995;49:S23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Abdulsalam W, Masri L. Ex-Post evaluation of UNICEF humanitarian action for children 2014-2015 in the state of Palestine UNICEF; 2016. https://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/files/Ex-Post_Evaluation_of_UNICEF_Humanitarian_Action_for_Children_2014-2015_in_the_State_of_Palestine.pdf [Accessed 29 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abu-Taleb R. Experiences of emergency nutrition programming in Jordan. Field Exchange 2015;48:93. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alsamman S. Managing infant and young child feeding in refugee camps in Jordan. Field Exchange 2014;48:85. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Barakat J. Community kitchens in Lebanon: cooking together for health. Nutrition Exchange 2017;8:9. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Battistin F. Impact evaluation of the multipurpose cash assistance programme Beirut: Lebanon Cash Consortium; 2016. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCCImpactEvaluationforMCAFebruary2016FINAL.PDF [Accessed 9 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berbari L, Ousta D, Asfahani F. Institutionalising acute malnutrition treatment in Lebanon. Field Exchange 2014;48:17. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chinjekure A, Shams DM, Qureshi DA. Screening for maternal and child malnutrition using sentinel-based national nutrition surveillance in Afghanistan. Field Exchange 2018;58:79. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Daniel T, Mekkawi T, Garelnabi H. Scaling up CMAM in protracted emergencies and low resource settings: experiences from Sudan. Field Exchange 2016;55:74. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Darjani P, Berbari L. Infant and young child feeding support in Lebanon:\ strengthening the national system. Field Exchange 2014;48:20. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Davidson J, Bethke C. Integrating community-based nutrition awareness into the Syrian refugee response in Lebanon. Field Exchange 2015;48:29. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Desie S. Somalia nutrition cluster: integrated famine prevention package. Field Exchange 2017:53–5. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dureab F, Jawaldeh DA, Abbas DL. Building capacity in inpatient treatment of severe acute malnutrition in Yemen. Field Exchange 2016;55:87. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Egendal R, Badejo A. WFP’s emergency programme in Syria. Field Exchange 2015;48:113. [Google Scholar]

- 91.El-Huni E. WFP e-voucher programme in Lebanon. Field Exchange 2015;48:36. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fänder G, Frega M. Responding to nutrition gaps in Jordan in the Syrian refugee crisis: infant and young child feeding education and malnutrition treatment. Field Exchange 2014;48:82. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Farah AI. School feeding: experiences from Somalia. Nutrition Exchange 2014;4:17. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Feldman S, Freccero J, Seelinger K. Safe Haven: Sheltering displaced persons from sexual and gender-based violence. Case study: Colombia. Geneva: Human Rights Center, University of California, Berkeley, in conjunction with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees; 2013. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/safe-haven-sheltering-displaced-persons-sexual-and-gender-based-violence [Accessed 10 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Giordano DK, Dunlop K, Gabay T, Sardiwal D. Evaluation synthesis of UNHCR’s cash based interventions in Jordan United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR); 2017. https://www.unhcr.org/5a5e16607.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hoetjes M, Rhymer W, Matasci-Phelippeau L. Emerging cases of malnutrition amongst IDPs in TAL Abyad district, Syria. Field Exchange 2015;48:133. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Inglis K, Vargas J. Experiences of the e-Food card programme in the Turkish refugee camps. Field Exchange 2014;48:145. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kozuki N, Van Boetzelaer E, Zhou A, Tesfai C . Enabling treatment of severe acute malnutrition in the community: study of a simplified algorithm and tools in South Sudan International Rescue Committee; 2018. https://www.rescue.org/report/enabling-treatment-severe-acute-malnutrition-community-study-simplified-algorithm-and-tools [Accessed 20 June 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Karagueuzian N. Healthy snacks and nutrition education: School feeding in Lebanon’s public schools. Nutrition Exchange 2017;8:10. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Karimova J, Hammoud J. Relief international nutrition and health programme in Lebanon. Field Exchange 2014;48:27. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Khudari H, Bozo M, Hoff E. Who response to malnutrition in Syria: a focus on surveillance, case detection and clinical management. Field Exchange 2015;48:118. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Laker M, Toose J. Nutrition programming in conflict settings: lessons from South Sudan. Field Exchange 2016;53:2. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Leonardi E, Arqués R. Real time evaluation of UNICEF’s response to the Mali crisis United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF); 2013. https://www.alnap.org/help-library/2013-mali-real-time-evaluation-of-unicef%E2%80%99s-response-to-the-mali-crisis [Accessed 27 April 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Murphy M, Abebe K, O’Mahony S. Management of acute malnutrition in infants less than six months in a South Sudanese refugee population in Ethiopia. Field Exchange 2017;55:70. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ndungu P, Tanaka J. Using care groups in emergencies in South Sudan. Field Exchange 2017;54:95–7. [Google Scholar]

- 106.O’Mahony A, MacAuslan I. Evaluation of post 2007 election violence recovery programme in Kenya. Field Exchange 2013;46:65. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sallam DF, Albably K, Zvandaziva C. Community engagement through local leadership: increasing access to nutrition services in a conflict setting in Yemen increasing access to nutrition services in a conflict setting in Yemen. Nutrition Exchange 2018;9:10 https://www.ennonline.net/nex/9nutserviceaccessyemen [Google Scholar]

- 108.Salse N, Salse N, Swarthout T, Xavier KF, Matsumoto A, Zahm C, James K, Grace OE, Palma P, De Clerck V, Casademont C, Roll S, Benassconi A . Effectiveness of nutritional supplementation (ready-to-use therapeutic food and multi micronutrient) in preventing malnutrition in children 6-59 months with infection (malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea) in Uganda27 April 201927 April 2019 MSF OCA; 2013. https://fieldresearch.msf.org/handle/10144/559079?show=fullhttps://fieldresearch.msf.org/handle/10144/559079?show=full [Accessed 27 April 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sebuliba H, El-Zubi F. Meeting Syrian refugee children and women nutritional needs in Jordan. Field Exchange 2015;48:74. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Seguin J. Challenges of IYCF and psychosocial support in Lebanon. Field Exchange 2014;48:24. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tchamba A. Alert and rapid response to nutritional crisis in DRC. Field Exchange 2017;54:3. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Van Der Merwe R. Impact of milling vouchers on household food security in South Sudan. Field Exchange 2014;47:7. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yunusu E, Markhan M. Cash-based programming to address hunger in conflict-affected South Sudan: a case study. South Sudan: World Vision; 2016. https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/World%20Vision%20Case%20Study%20South%20Sudan_cash.pdf [Accessed 18 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]