Abstract

Background

Smell dysfunction has been recognized as an early symptom of SARS-CoV-2 infection, often occurring before the onset of core symptoms of the respiratory tract, fever or muscle pain. In most cases, olfactory dysfunction is accompanied by reduced sense of taste, is partial (microsmia) and seems to normalize after several weeks, however, especially in cases of virus-induced complete smell loss (anosmia), there are indications of persisting deficits even 2 months after recovery from the acute disease, pointing towards the possibility of chronic or even permanent smell reduction for a significant part of the patient population. To date, we have no knowledge on the specificity of anosmia towards specific odorants or chemicals and about the longer-term timeline of its persistence or reversal.

Methods

In this longitudinal study, 70 participants from a community in Lower Austria that had been tested positive for either IgG or IgM SARS-CoV-2 titers in June 2020 and a healthy control cohort (N = 348) underwent smell testing with a 12-item Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT), based upon items from the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT). The test was performed in October 2020, i.e. 4 months after initial diagnosis via antibody testing. Results were analyzed using statistical tests for contingency for each smell individually in order to detect whether reacquisition of smell is dependent on specific odorant types.

Results

For all odorants tested, except the odor “smoke”, even 4 months or more after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, participants with a positive antibody titer had a reduced sense of smell when compared to the control group. On average, while the control cohort detected a set of 12 different smells with 88.0% accuracy, the antibody-positive group detected 80.0% of tested odorants. A reduction of accuracy of detection by 9.1% in the antibody-positive cohort was detected. Recovery of the ability to smell was particularly delayed for three odorants: strawberry (encoded by the aldehyde ethylmethylphenylglycidate), lemon (encoded by citronellal, a monoterpenoid aldehyde), and soap (alkali metal salts of the fatty acids plus odorous additives) exhibit a sensitivity of detection of an infection with SARS-CoV-2 of 31.0%, 41.0% and 40.0%, respectively.

Conclusion

Four months or more after acute infection, smell performance of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients with mild or no symptoms is not fully recovered, whereby the ability to detect certain odors (strawberry, lemon and soap) is particularly affected, suggesting the possibility that these sensitivity to these smells may not only be lagging behind but may be more permanently affected.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Smell and taste dysfunction, Anosmia, Microsmia, Dysgeusia, Smell test

1. Introduction

Following an accumulation of publications in 2020, it has become widely accepted that complete (anosmia) or partial (hyposmia or microsmia) loss of olfaction as well as the loss of taste (ageusia) are common symptoms induced by SARS-CoV-2 ([1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]). Due to its early onset during the disease course, it was proposed that olfactory testing be implemented as an early screening measure ([11], [12], [13], [14], [15]). The data on prevalence of olfactory dysfunction (OD) among COVID-19 patients varies considerably from study to study, ranging from 5.0% to 98.0% (16). This variation may be explained by the heterogeneity of patient cohorts (severely, mildly affected or asymptomatic) but also due to the fact that in most studies smell function was assessed through self-reporting or questionnaire-based surveys both of which are prone to recall and other biases (17,18). Indeed, individuals consistently underestimate the extent of their hyposmia through self-reporting (19,20). In a recent meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence estimate of smell loss was 45.0% when assessed with subjective measurements (questionnaire/survey), and was 77.0% when assessed through objective measurements (16).

One of the highly validated smell tests is the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) (21), a 40-odorant test, which showed, in an Iranian cohort, that 98.0% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients exhibited smell dysfunction and 25.0% were fully anosmic, whereas age and sex matched controls did not exhibit these deficiencies (18). Another study found 85.0% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients to be impacted by ansomia/hyposmia (22). The validated Connecticut Chemosensory Clinical Research Center orthonasal olfaction test (23) was applied in a hospital setting and revealed that 73.6% of inpatient patients reported chemo sensitive disorders (24), while the same test was self-administered at home by a mildly affected home-quarantined small cohort of 33 patients revealed OD dysfunction in 63.6% of patients (9). Taken together, relatively few published studies are based on validated smell tests, and even less focus on mildly affected or asymptomatic patients despite studies indicating a higher prevalence of olfactory dysfunction among this subgroup. There is evidence towards an inverse correlation of disease severity and prevalence of OD. Thus, admission for COVID-19 was associated with intact sense of smell and taste, increased age, diabetes, as well as respiratory failure (25,26). Within a hospitalized patient cohort, a lower number of 52.5% of patients experienced either smell or taste dysfunction (27). In another study, the younger lesser affected patient population as well as females seemed to be more severely affected by OD (13,14,28). Lechien et al. also determined a lesser incidence of OD in hospitalized cases compared to mild-moderate cases (29). However, not all studies could confirm such an inverse correlation between disease severity and prevalence of OD (30). Therefore, there is a need to perform standardized smell tests in the mildly affected or even otherwise asymptomatic patient population.

One interesting aspect that is still understudied is the duration of OD after infection. Recovery of smell loss has been assessed primarily through self-reporting and, like with prevalence reports, there is variation between reports. One study reported that 74.0% of patients experienced a resolution of anosmia at recovery (25) or within 1–3 weeks after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms ([31], [32], [33]). An approximately 80.0% recovery rate was found within 4 weeks of symptom onset (2). Another study found that the average olfactory score improved rapidly, but moderate hyposmia values were reported for 35 days (30). The consensus from these questionnaire-based reports is that olfactory function in hospitalized patients generally normalizes after 2 weeks (17). Interestingly, total recovery was seen more frequently in COVID-19 patients with sudden hyposmia than the ones with sudden anosmia (33,34). In a study using the UPSIT, a 40-odorant psychophysical smell test, it was determined that 8 weeks after symptom-onset, 61.0% patients had regained normal function, and that in 39.0% of cases, a degree of microsmia was retained (17). After 6 weeks of onset of OD the average UPSIT scores remained below those of age- and sex-matched normal controls indicating that the timeline for full recovery may be indeed longer than presumed or that there may be a permanent reduction in olfactory performance in at least a subset of patients (17).

Another aspect that has not been evaluated is the question of specificity, whether OD is general or specific towards certain odorants or tastes. Overall, this does not seem to be the case since deficits were evident for all test odors (18). However, it is nevertheless possible that the ability to perceive certain odorants is recovered less efficiently than others. Our study therefore aimed at determining whether microsmia is chronically persistent and whether this may be linked to specific smells. To achieve this, we performed a reduced version of the UPSIT test on non-hospitalized, either mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic patients that had recovered from the acute infection at least 4 months before testing.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and smell tests

On June 20, 2020, 418 people in the community of Weissenkirchen in Lower Austria (Wachau) volunteered for antibody testing (IgG und IgM ELISA, Bioscientia Healthcare GmbH). Of the cohort of 166 women [39.7%] and 252 men [60.3%] no one exhibited COVID-19-like symptoms such as fever, muscle pain or breathing difficulties at the time of testing. We identified 70 positive cases (30 women [44.1%] and 40 men [58.8%]) with an average age of 49.8 years that had a positive IgA and/or IgG titer. All volunteers (that tested positive or negative in the antibody test) were asked to perform a standardized smell test (CC-SIT), a 12-item self-administered encapsulated odorant test in booklet form (35), acquired from Burghart Messtechnik (Wedel, Germany) on Oct 17th 2020. Tests were performed according to manufacturer's instructions by participants at their homes while being guided through the test by medical students via videocall. Participants were also demographically assessed through a patient questionnaire and questioned about comorbidities and life-style parameters such as smoking or alcohol consumption.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was done by SPSS, Version 26.0. The statistical tests are mainly the Likelihood-Ratio-Chi-square, the level of significance was set to 5.0%. The test-epidemiological characteristics of sensitivity and specificity are analyzed using the common formulars.

3. Results

3.1. Description of cohort

Since the initial aim of this study was to monitor IgG/IgA prevalence in a hotspot of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Lower Austria and to observe changes in antibody titers over time, our cohort was not evenly distributed among antibody-negative (N = 348) and antibody-positive participants who will be termed “recovered group” in the text, tables and figures (N = 70) (Table 1 ). The gender distribution was comparable, with 39.0% and 43.0% females in control and recovered groups, respectively. Of the recovered group the self-reported health status was predominantly “very good or good”, comparable to that of the control group. 18 of the 70 participants in the recovered group had previously been tested positive in a PCR test for SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample.

| Number (%) of patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Control Group | % | Recovered | % | ||

| Number | 418 | 348 | 83.3 | 70 | 16.7 | |

| Age (yr), median | 33.5 | 49.9 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 166 | 136 | 39.1 | 30 | 42.9 |

| Male | 252 | 212 | 60.9 | 40 | 57.1 | |

| Antibody tests | ||||||

| IgG positive | June 2020 | – | – | 47 | 67.1 | |

| October 2020 | – | – | 34 | 48.6 | ||

| IgA positive | June 2020 | – | – | 50 | 71.4 | |

| October 2020 | – | – | 44 | 62.9 | ||

| IgG + IgA positive | June 2020 | – | – | 34 | 48.6 | |

| October 2020 | – | – | 33 | 47.1 | ||

| Self-assessment health status | Very good | 190 | 54.6 | 37 | 52.9 | |

| Good | 120 | 34.5 | 30 | 42.9 | ||

| Tired | 36 | 10.3 | 3 | 4.3 | ||

| Ill | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Previous illness in the last 6 month | No | 234 | 67.2 | 50 | 71.4 | |

| Yes | 114 | 32.8 | 20 | 28.6 | ||

| Connected to | ||||||

| SARS-CoV2 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 25.7 | ||

| Influenca | 4 | 1.1 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Streptococci | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Not tested | 340 | 97.7 | 51 | 72.9 | ||

| Others | 4 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Actual symptoms | No | 260 | 74.7 | 58 | 82.9 | |

| Yes | 88 | 25.3 | 12 | 17.1 | ||

| Temperature | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Rhinorrhea | 30 | 8.6 | 5 | 7.1 | ||

| Diarrhea | 3 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Fatigue | 40 | 11.5 | 6 | 8.6 | ||

| Shortness of breathe | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Headache | 11 | 3.2 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Cough | 22 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Angina | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Pharyngitis | 3 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Cough sputum | 5 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Muscle pain | 7 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Nausea | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Self-reported reduction in | Olfactory function | 10 | 2.9 | 12 | 17.1 | |

| Gustatory function | 10 | 2.9 | 9 | 12.9 | ||

| Others | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Reported health problems | None | 253 | 72.7 | 52 | 74.3 | |

| Allergies | 77 | 22.1 | 9 | 12.9 | ||

| Coronary heart diseases | 3 | 0.9 | 5 | 7.1 | ||

| Alzheimer | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Asthma | 12 | 3.4 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Traumatric brain insury | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Parkinson | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Nasal polyps | 6 | 1.7 | 2 | 2.9 | ||

| Kidney insufficiency | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Apoplex | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Cancer | 3 | 0.9 | 2 | 2.9 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.4 | ||

| Diabetes | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 4.3 | ||

| Smoking | Yes | 65 | 18.7 | 8 | 11.4 | |

| No | 283 | 81.3 | 62 | 88.6 | ||

| Alcohol | Yes | 277 | 79.6 | 53 | 75.7 | |

| AU/week (average) | 6.6 | 6.8 | ||||

| No | 71 | 20.4 | 17 | 24.3 | ||

| Drugs | Yes | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| No | 347 | 99.7 | 70 | 100.0 | ||

| Environmental influences | Yes | 25 | 7.2 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| No | 323 | 92.8 | 66 | 94.3 | ||

| Spicy food | Yes | 151 | 43.4 | 21 | 30.0 | |

| No | 197 | 56.6 | 49 | 70.0 | ||

| Odor book | Correct from 12 odors (average) | 10.5 | 87.5 | 9.6 | 80.0 | |

Comorbidities in the two groups were comparable for most conditions, except for allergies and asthma which were higher in the control group. 12.9% of members of the recovered group and 22.1% of the control group reported allergies, and 1.4% of members of the recovered group had asthma compared to 3.4% in the control group (Table 1).

Interestingly, 18.7% of members of the control group and only 11.4% in the recovered group are smokers, in line with previous observations of smokers being underrepresented in COVID-19 patients cohorts (36).

17.1% and 12.9% of the antibody-positive group reported a reduction in olfactory and gustatory function, respectively. In contrast, 2.9% in the control group indicated either olfactory and gustatory dysfunction.

3.2. Smell test CC-SIT

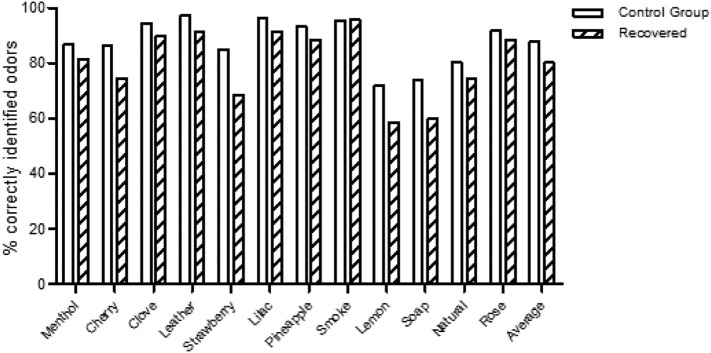

In the CC-SIT, SARS-CoV-2 positive participants showed a reduced sense of smell and correctly detected 80.0% of the samples compared to control group which on average 88.0% of the tested smells (Fig. 1 ). It is of note that in all the odor groups except smoke the recovered group showed a reduced capacity of detection. The biggest differences occurred with 3 smells, strawberry, lemon and soap, for which the ability to detect was reduced by 20.0%, 18.04% and 19.0% respectively (Fig. 1, Table 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the percentage of correctly identified different odors from the standardized smell test (CC-SIT-Burghart Messtechnik; Wedel, Germany).

Table 2.

Results obtained from the standardized smell test (CC-SIT-Burghart Messtechnik; Wedel, Germany) of the probands. The test kit is a 12-item self-administered encapsulated odorant test in booklet form. The odors lemon, soap, strawberry and natural gas were the most incorrect identified odors in both groups.

| Odor | Control group | % | Recovered | % | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menthol | Correct | 302 | 86.8 | 57 | 81.4 | 359 |

| Not correct | 46 | 13.2 | 13 | 18.6 | 59 | |

| Cherry | Correct | 300 | 86.2 | 52 | 74.3 | 352 |

| Not correct | 48 | 13.8 | 18 | 25.7 | 66 | |

| Clove | Correct | 329 | 94.5 | 63 | 90.0 | 392 |

| Not correct | 19 | 5.5 | 7 | 10.0 | 26 | |

| Leather | Correct | 338 | 97.1 | 64 | 91.4 | 402 |

| Not correct | 10 | 2.9 | 6 | 8.6 | 16 | |

| Strawberry | Correct | 296 | 85.1 | 48 | 68.6 | 344 |

| Not correct | 52 | 14.9 | 22 | 31.4 | 74 | |

| Lilac | Correct | 335 | 96.3 | 64 | 91.4 | 399 |

| Not correct | 13 | 3.7 | 6 | 8.6 | 19 | |

| Pineapple | Correct | 324 | 93.1 | 62 | 88.6 | 386 |

| Not correct | 24 | 6.9 | 8 | 11.4 | 32 | |

| Smoke | Correct | 332 | 95.4 | 67 | 95.7 | 399 |

| Not correct | 16 | 4.6 | 3 | 4.3 | 19 | |

| Lemon | Correct | 250 | 71.8 | 41 | 58.6 | 291 |

| Not correct | 98 | 28.2 | 29 | 41.4 | 127 | |

| Soap | Correct | 258 | 74.1 | 42 | 60.0 | 300 |

| Not correct | 90 | 25.9 | 28 | 40.0 | 118 | |

| Natural gas | Correct | 279 | 80.2 | 52 | 74.3 | 331 |

| Not correct | 69 | 19.8 | 18 | 25.7 | 87 | |

| Rose | Correct | 319 | 91.7 | 62 | 88.6 | 381 |

| Not correct | 29 | 8.3 | 8 | 11.4 | 37 |

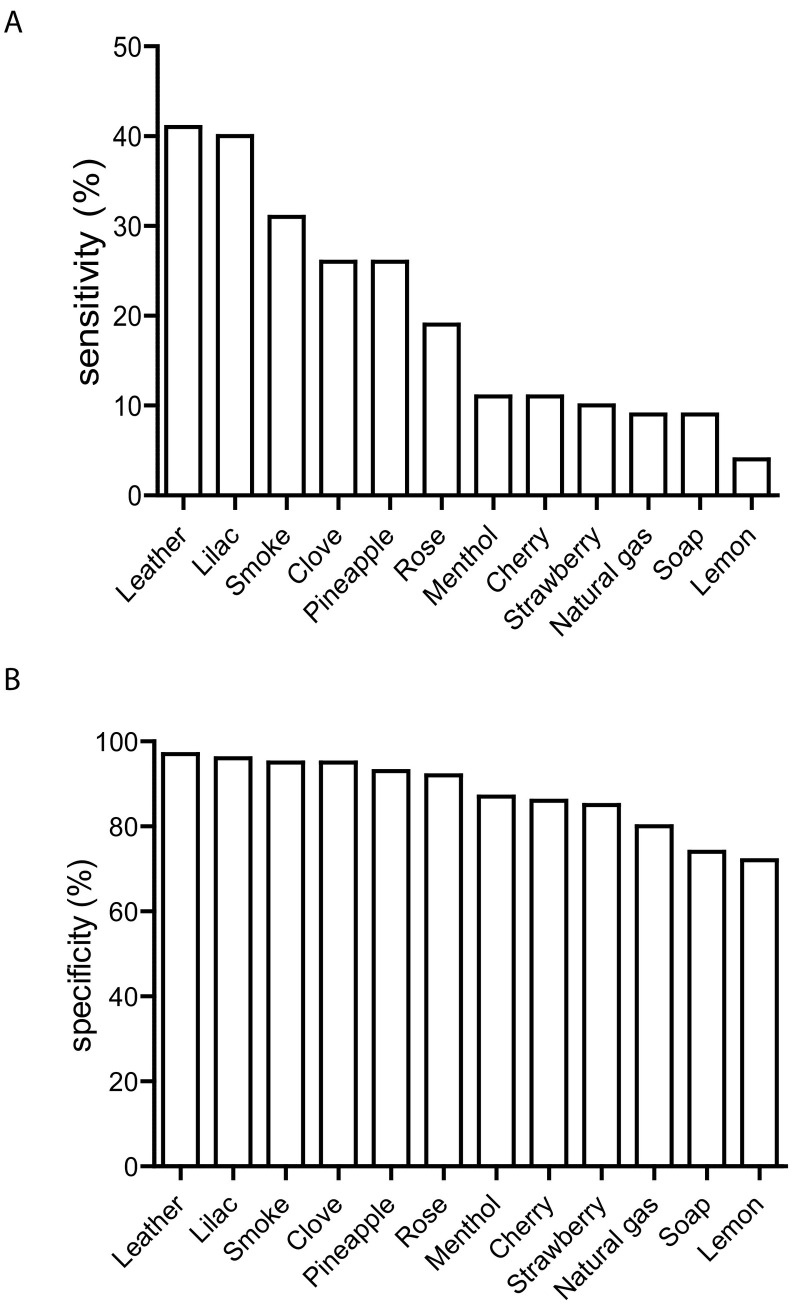

We used an epidemiological approach to calculate sensitivity and specificity values for each odorant. In our setting, sensitivity signifies the probability that an antibody-positive person cannot detect a specific odorant. Again, the three odorants lemon, soap and strawberry are on top of the list (Table 3A), with sensitivities of 41.1%, 40.0% and 31.4% respectively (Fig. 2A, Table 3A). Odorants with the lowest sensitivities are leather, lilac and smoke, with values of 8.6%, 8.6% and 4.3%, respectively. Specificity values which describe the probability that a healthy, antibody-negative person identifies a smell correctly, are highest for the odors leather (97.1%), lilac (96.3%) and smoke (95.4%) while strawberry (85.1%), soap (74.1%) and lemon (71.8%) rank lowest (Fig. 2B, Table 3B).

Table 3.

Odors ranked by the sensitivity (A) and specificity (B). Sensitivity signifies the probability that an antibody positive-person cannot detect a specific odorant and specificity values describe the probability that a healthy, antibody-negative person identifies a smell correct.

| A | |

|---|---|

| Odor | Sensitivity % |

| Lemon | 41.4 |

| Soap | 40.0 |

| Strawberry | 31.4 |

| Cherry | 25.7 |

| Natural gas | 25.7 |

| Menthol | 18.6 |

| Pineapple | 11.4 |

| Rose | 11.4 |

| Clove | 10.0 |

| Leather | 8.6 |

| Lilac | 8.6 |

| Smoke | 4.3 |

| B | |

|---|---|

| Odor | Specificity % |

| Leather | 97.1 |

| Lilac | 96.3 |

| Smoke | 95.4 |

| Clove | 94.5 |

| Pineapple | 93.1 |

| Rose | 91.7 |

| Menthol | 86.8 |

| Cherry | 86.2 |

| Strawberry | 85.1 |

| Natural gas | 80.2 |

| Soap | 74.1 |

| Lemon | 71.8 |

Fig. 2.

Odors ranked by the sensitivity (A) and specificity (B), as also shown in Table 3. Sensitivity signifies the probability that an antibody positive-person cannot detect a specific odorant and specificity values describe the probability that a healthy, antibody-negative person identifies a smell correct.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that after a period of 4–7 months after acute mild or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, the ability for a subgroup of 9.1% of patients (the difference between the percentage of correctly smelling control group members, set to 100.0%, minus the percentage of correctly smelling recovered patients which equals 9.1%) to smell most odors (except for “smoke”) is still reduced. Especially, lemon and soap show a sensitivity of 40.0% or more, suggesting that the ability to perceive these odorants is difficult to reacquire or may be more permanently affected than others. However, these smells are also among the odorants that show the least specificity, pointing towards a larger variability in the capacity to smell these odors also in healthy adults.

The design of our longitudinal study does not allow us to pinpoint when the acute infection of our antibody positive cohort had taken place, since in our study no PCR testing was performed and only 18 out of 70 participants had been aware of their previous infection. Attribution to antibody positive (“recovered”) or antibody negative (“control”) groups were made based on measuring IgA and IgG titers at two time points, in June and October 2020. IgA antibodies were shown to be the first antibodies generated to mount the SASR-Cov2 specific humoral response and while serum concentrations drop after one month, they remain present for long periods, i.e. over months (37). IgG antibodies are detectable after 1 week and maintain at a high level for a long period (38). In our cohort, levels slightly decay of both antibody species, by 27.6% for IgG and by 11.9% for IgA within the period of 4 months (unpublished data). The fact that IgGs did not increase in this period indicates that on average the peak of infection within our cohort most probably dates back to the first wave of infections in Lower Austria, in March 2020. This also implies that the olfactory deficit may persist for odors such as lemon and soap for seven or more months and raises the question whether long-lasting damage to the olfactory tract and/or the central nervous system may underlie the phenotype. Deciphering mechanistically how OD is caused and re-acquired is still an unmet task.

To date, it is ruled out that changes in nasal airflow are the cause of OD since patients with smell loss who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 do not suffer from nasal obstruction and reduced air flow as caused by the swelling of the mucosa. One study reported that only 4.0% of patients with olfactory function loss present with additional nasal obstruction (13,39) indicating that olfactory loss is caused not by rhinitis but by damage to either the peripheral and/or central components of the olfactory system. When patients with a blocked nose were excluded from analysis, the symptom “sudden smell loss” yielded a high specificity (97.0%) with a positive predictive value of 63.0% and negative predictive value of 97.0% for COVID-19 (14). Since other coronaviruses have been shown to be neuroinvasive, the question arises if SARS-CoV-2 uses the nasal epithelium as a port of entry to the brain, causing olfactory dysfunction through action on the peripheral or the central components of the olfactory system. SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid in humans (40,41) and in animal models (42,43) and although the nasal epithelium is clearly infiltrated by virus, it is unclear whether it is the entry point to central brain regions.

In support of a more direct action of the virus on the olfaction apparatus, it has been demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 virus can be detected in the hamster olfactory epithelium, where not olfactory neurons but sustentacular cells were attained (44). Sustentacular cells maintain the structural integrity of the olfactory epithelium and allow proper cilia development and functioning of olfactory neurons, therefore being crucial for efficient functioning of neurons (44). The expression of the two entry proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in sustentacular cells in the rodent olfactory epithelium supports the implication of these cells in virus-mediated damage (45). Because regeneration of sustentacular cells occurs much faster than that of olfactory neurons, it has been proposed that recovery of olfactory function, usually within 3 weeks after symptom onset, may coincide with recovery of sustentacular cells (40,44). Due to the fast recovery of sustentacular cells, we reason that they may not be the cells mediating long-lasting hyposmia but that a more profound damage to the nasal epithelium including olfactory neuron loss may be involved. While it was shown that epithelial destruction varied in both the human and animal studies (44) not enough data have been collected to better understand the underlying defects.

Our study further opens the question of odorant specificity: We found that the ability to detect certain odorants, especially strawberry, lemon and soap, is particularly difficult to reacquire or may for a subset of patients be permanently reduced. Since during the acute phase of infection, a loss of olfaction towards these (or other) specific odorants has not been reported (1,18), we believe the more likely explanation may imply a mechanism whereby specific olfactory neurons tasked with the recognition of certain odorants are more difficult or slower to regenerate.

In conclusion, our study of 70 SARS-CoV-2 antibody-positive and 348 control participants corroborates the finding that smell dysfunction is long-lasting (at least 4 months) or possibly permanent for a subset of mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 cases and that certain odors are particularly affected.

This knowledge could be exploited in cost-effective and fast specific smell tests the ENT clinic to monitor the recovery of olfactory function after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and financed by the Lower Austrian Provincial Government – Department K3 “Science and Research”.

The authors would like to thank Drs. R. Braun and D. Ladage for sharing unpublished data.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was conducted after obtaining the approval DPU-EK/002.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

References

- 1.Lechien J.R., Cabaraux P., Chiesa-Estomba C.M., Khalife M., Hans S., Calvo-Henriquez C., et al. Objective olfactory evaluation of self-reported loss of smell in a case series of 86 COVID-19 patients. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1583–1590. doi: 10.1002/hed.26279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins C., Surda P., Whitehead E., Kumar B.N. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic - an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melley LE, Bress E, Polan E. Hypogeusia as the initial presenting symptom of COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Rebholz H., Braun R.J., Ladage D., Knoll W., Kleber C., Hassel A.W. Loss of olfactory function-early indicator for Covid-19, other viral infections and neurodegenerative disorders. Front Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.569333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lechien JR C-EC, Hans S, Barillari MR, Jouffe L, Saussez S. Loss of smell and taste in 2013 European patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. Ann Intern Med (2020): 10.7326/M20-2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Carignan A., Valiquette L., Grenier C., Musonera J.B., Nkengurutse D., Marcil-Heguy A., et al. Anosmia and dysgeusia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an age-matched case-control study. CMAJ. 2020;192(26):E702–E707. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vargas-Gandica J., Winter D., Schnippe R., Rodriguez-Morales A.G., Mondragon J., Escalera-Antezana J.P., et al. Ageusia and anosmia, a common sign of COVID-19? A case series from four countries. J Neurovirol. 2020;26(5):785–789. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00875-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joffily L., Ungierowicz A., David A.G., Melo B., Brito C.L.T., Mello L., et al. The close relationship between sudden loss of smell and COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86(5):632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaira L.A., Salzano G., Petrocelli M., Deiana G., Salzano F.A., De Riu G. Validation of a self-administered olfactory and gustatory test for the remotely evaluation of COVID-19 patients in home quarantine. Head Neck. 2020;42(7):1570–1576. doi: 10.1002/hed.26228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaye R., Chang C.W.D., Kazahaya K., Brereton J., Denneny J.C., 3rd. COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):132–134. doi: 10.1177/0194599820922992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iravani B., Arshamian A., Ravia A., Mishor E., Snitz K., Shushan S., et al. Relationship between odor intensity estimates and COVID-19 prevalence prediction in a Swedish population. Chem Senses. 2020;45(6):449–456. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson P., Rabold E.M., Laws R.L., Conners E.E., Gharpure R., Yin S., et al. Loss of taste and smell as distinguishing symptoms of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;72(4):682–685. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltran-Corbellini A., Chico-Garcia J.L., Martinez-Poles J., Rodriguez-Jorge F., Natera-Villalba E., Gomez-Corral J., et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1111/ene.14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haehner A., Draf J., Drager S., de With K., Hummel T. Predictive value of sudden olfactory loss in the diagnosis of COVID-19. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2020;82(4):175–180. doi: 10.1159/000509143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitcroft K.L., Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: diagnosis and management. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2512–2514. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannum M.E., Ramirez V.A., Lipson S.J., Herriman R.D., Toskala A.K., Lin C., et al. Objective sensory testing methods reveal a higher prevalence of olfactory loss in COVID-19-positive patients compared to subjective methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Senses. 2020;45(9):865–874. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjaa064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moein S.T., Hashemian S.M., Tabarsi P., Doty R.L. Prevalence and reversibility of smell dysfunction measured psychophysically in a cohort of COVID-19 patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(10):1127–1135. doi: 10.1002/alr.22680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moein S.T., Hashemian S.M.R., Mansourafshar B., Khorram-Tousi A., Tabarsi P., Doty R.L. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(8):944–950. doi: 10.1002/alr.22587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soter A., Kim J., Jackman A., Tourbier I., Kaul A., Doty R.L. Accuracy of self-report in detecting taste dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(4):611–617. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318161e53a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams D.R., Wroblewski K.E., Kern D.W., Kozloski M.J., Dale W., McClintock M.K., et al. Factors associated with inaccurate self-reporting of olfactory dysfunction in older US adults. Chem Senses. 2017;42(3):223–231. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjw108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doty R.L., McKeown D.A., Lee W.W., Shaman P. A study of the test-retest reliability of ten olfactory tests. Chem Senses. 1995;20(6):645–656. doi: 10.1093/chemse/20.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hornuss D., Lange B., Schroter N., Rieg S., Kern W.V., Wagner D. Anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(10):1426–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cain W.S., Gent J., Catalanotto F.A., Goodspeed R.B. Clinical evaluation of olfaction. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4(4):252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(83)80068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaira L.A., Deiana G., Fois A.G., Pirina P., Madeddu G., De Vito A., et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1252–1258. doi: 10.1002/hed.26204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan C.H., Faraji F., Prajapati D.P., Boone C.E., DeConde A.S. Association of chemosensory dysfunction and Covid-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(7):806–813. doi: 10.1002/alr.22579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luers JC, Klussmann JP, Guntinas-Lichius O. [The Covid-19 pandemic and otolaryngology: what it comes down to?]. Laryngorhinootologie. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Giacomelli A., Pezzati L., Conti F., Bernacchia D., Siano M., Oreni L., et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):889–890. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Speth M.M., Singer-Cornelius T., Oberle M., Gengler I., Brockmeier S.J., Sedaghat A.R. Olfactory dysfunction and sinonasal symptomatology in COVID-19: prevalence, severity, timing, and associated characteristics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):114–120. doi: 10.1177/0194599820929185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lechien JRD, M.; Place, S.; Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Khalife, M.; De Riu, G.; Vaira, L.A.; de Terwangne, C.; Machayekhi, S.; Marchant, A.; Journe, F.; Saussez, S. The Prevalence of SLS in Severe COVID-19 Patients Appears to be Lower Than Previously Estimated in Mild-to-moderate COVID-19 Forms. 2020:9(8): 627.

- 30.Vaira LA SG, Deiana G, De Riu G. In Response to Anosmia and Ageusia: Common Findings in COVID-19 Patients. Laryngoscope. 2020: 10.1002/lary.28753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bocksberger S., Wagner W., Hummel T., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Hoelscher M., et al. Temporary hyposmia in COVID-19 patients. HNO. 2020;68(6):440–443. doi: 10.1007/s00106-020-00891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klopfenstein T., Kadiane-Oussou N.J., Toko L., Royer P.Y., Lepiller Q., Gendrin V., et al. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50(5):436–439. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amer M.A., Elsherif H.S., Abdel-Hamid A.S., Elzayat S. Early recovery patterns of olfactory disorders in COVID-19 patients; a clinical cohort study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(6):102725. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kosugi E.M., Lavinsky J., Romano F.R., Fornazieri M.A., Luz-Matsumoto G.R., Lessa M.M., et al. Incomplete and late recovery of sudden olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86(4):490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doty R.L., Marcus A., Lee W.W. Development of the 12-item cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT) Laryngoscope. 1996;106(3 Pt 1):353–356. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199603000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usman M.S., Siddiqi T.J., Khan M.S., Patel U.K., Shahid I., Ahmed J., et al. Is there a smoker’s paradox in COVID-19? BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterlin D, Mathian A, Miyara M, Mohr A, Anna F, Claer L, et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(577). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Hou H., Wang T., Zhang B., Luo Y., Mao L., Wang F., et al. Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Transl Immunology. 2020;9(5) doi: 10.1002/cti2.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xydakis M.S., Dehgani-Mobaraki P., Holbrook E.H., Geisthoff U.W., Bauer C., Hautefort C., et al. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1015–1016. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meinhardt J., Radke J., Dittmayer C., Franz J., Thomas C., Mothes R., et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paniz-Mondolfi A., Bryce C., Grimes Z., Gordon R.E., Reidy J., Lednicky J., et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):699–702. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang R.D., Liu M.Q., Chen Y., Shan C., Zhou Y.W., Shen X.R., et al. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 in transgenic mice expressing human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Cell. 2020;182(1):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.027. [e8] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun S.H., Chen Q., Gu H.J., Yang G., Wang Y.X., Huang X.Y., et al. A mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28(1):124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.020. [e4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryche B., St Albin A., Murri S., Lacote S., Pulido C., Ar Gouilh M., et al. Massive transient damage of the olfactory epithelium associated with infection of sustentacular cells by SARS-CoV-2 in golden Syrian hamsters. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bilinska K JP, Von Bartheld CS, Butowt R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in cells of the olfactory epithelium: identification of cell types and trends with age. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020:11( ):1555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]