ABSTRACT

Background: Despite knowledge about the extensive and often long-lasting consequences of sexual assault, many survivors remain underserved by formal support systems (e.g. medical, mental health and criminal justice systems). Reasons for underutilizing services are as diverse as the survivors themselves, and little is known about which survivors are most underserved and why they are underserved.

Objective: To help organize existing findings on this topic, a systematic scoping review was conducted to identify adult survivors of sexual assault, who may be particularly underserved when attempting to obtain services in Western countries.

Method: Five databases (PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus and CINAHL) were systematically searched for studies published in English from 2000 onwards using terms such as ‘sexual assault’, ‘help seeking’, ‘formal support’, ‘barriers’ and variations thereof.

Results: A total of 41 studies were included in the present scoping review, resulting in seven main categories of underserved survivors: Ethnic and cultural minorities, Disabilities, Financial vulnerability, Sexual and gender minorities, Mental health conditions, Problematic substance use, and Older age. Barriers encountered by survivors with these characteristics included limited access to formal supports and insufficient training and awareness among service providers about how to best support survivors.

Conclusions: Recommendations include the need for more survivor-centred, culturally appropriate and trauma-informed services and more attention to survivors belonging to underserved groups in policy, practice and research.

KEYWORDS: Rape, sexual assault, help seeking, service utilization, service provision, formal supports, mental health services, criminal justice systems, diversity, underserved

HIGHLIGHTS

• We found: Survivors of sexual assault from historically marginalized groups face numerous barriers to service utilization.

• This means: A more survivor-centered, culturally appropriate and trauma-informed approach to sexual assault service delivery is needed.

Abstract

Antecedentes: A pesar del conocimiento acerca de las consecuencias extensas y a menudo duraderas de la agresión sexual, muchos sobrevivientes permanecen desatendidos por los sistemas de apoyo formales (ej., sistemas médicos, salud mental y de justicia criminal). Las razones para la subutilización de los servicios son tan diversas como los propios sobrevivientes, y se conoce poco acerca de qué sobrevivientes son los más desatendidos y las razones de por qué lo son.

Objetivo: Para ayudar a organizar los hallazgos existentes en este tema, se realizó una revisión sistemática del alcance para identificar, en países occidentales, a sobrevivientes adultos de agresión sexual, quienes pueden ser particularmente desatendidos cuando intentan obtener apoyo.

Método: Se buscó sistemáticamente en cinco bases de datos (PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus y CINHAL) estudios publicados en Inglés desde el 2000 en adelante, usando los términos ‘agresión sexual’, ‘búsqueda de ayuda’, ‘apoyo formal’, ‘barreras’ y variaciones de los mismos.

Resultados: Se incluyó un total de 41 estudios en la presente revisión del alcance, resultando en siete categorías principales de sobrevivientes desatendidos: Minorías étnicas y culturales, Discapacidades, Vulnerabilidad económica, Minorías sexuales y de género, Condiciones de salud mental, Uso problemático de sustancias y mayor edad. Las barreras encontradas por los sobrevivientes con estas características fueron acceso limitado a los apoyos formales e insuficiente entrenamiento y conocimiento entre los proveedores de los servicios acerca de cuál es la mejor forma de apoyar a los sobrevivientes.

Conclusiones: Las recomendaciones incluyen la necesidad de servicios más centrados en el sobreviviente, adecuados culturalmente e informados en trauma y mayor atención a los sobrevivientes que pertenecen a los grupos desatendidos en relación a las políticas, práctica clínica e investigación.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Violación, agresión sexual, búsqueda de ayuda, utilización de servicios, prestación de servicios, apoyos formales, servicios de salud mental, sistema judicial criminal, diversidad, desatendidos

Abstract

背景: 尽管已知性侵犯广泛且往往长期存在的后果, 但许多幸存者仍然没有得到正式的支持系统 (例如, 医疗, 心理健康和刑事司法系统) 的服务。未得到充分服务的原因与幸存者本身一样多种多样, 对于哪些幸存者最未得到服务以及为什么他们得不到充分服务知之甚少。

目的: 为帮助组织此主题相关的现有发现, 进行了系统范围综述, 以识别出西方国家中试图寻求服务而未得到充分服务的成年性侵犯幸存者。

方法: 系统地在五个数据库 (PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus和CINAHL) 搜索了自2000年以来使用了‘性侵犯’, ‘寻求帮助’, ‘正式支持’, ‘障碍’及其变体的英文发表研究。

结果: 本范围综述中总共纳入了41项研究, 导致未得到充分服务的幸存者主要分为七类:少数民族和文化少数群体, 残疾人, 经济脆弱者, 性少数和性别少数群体, 心理健康疾病患者, 有问题的物质使用人群和老年人。具有这些特征的幸存者遇到的障碍包括获得正式支持的机会有限以及服务提供者关于如何最好地支持幸存者的培训和意识不足。

结论: 建议包括需要更多以幸存者为中心, 在文化适当和创伤知情的服务, 以及在政策, 实践和研究中更多关注未得到充分服务人群的幸存者。

关键词: 强奸, 性侵犯, 帮助寻求, 利用服务, 提供服务, 正式支持, 心理健康服务, 刑事司法系统, 多样性, 未得到充分服务的

The service needs of survivors of sexual assault (SA) are extensive, encompassing a wide variety of physical, psychological, social and legal needs (Koss, Hansen, Anderson, Hardeberg-Bach, & Holm-Bramsen, 2020). Although various services are accessed by survivors, specialized SA services, such as Sexual Assault Referral Centers (SARCs), are the first point of contact with formal support systems for many survivors. SARCs provide forensic examination, acute medical care, advocacy and short-term counselling in healthcare facilities in some parts of the US, Canada, Australia, and Europe (Walby et al., 2015). Several studies have indicated that these multidisciplinary and coordinated support models have positive effects in terms of promoting recovery and improving legal outcomes (e.g. Campbell, Patterson, & Lichty, 2005; Oosterbaan, Covers, Bicanic, Huntjens, & De Jongh, 2019). Not all survivors choose to reach out for help, however, and not all survivors have access to such services (Ullman, 2007). Research conducted in the US indicates that most survivors served in the formal support system are characterized as white, urban, non-elderly, English speaking women without disabilities (Koss, White, & Lopez, 2017). Thus, members of historically marginalized groups seem less likely to utilize formal support systems (e.g. medical, mental health and criminal justice systems (CJS) (Armstrong et al., 2019; Bryant-Davis, Chung, & Tillman, 2009; Ullman, 2007). Possible explanatory reasons for these disparities include structural barriers to service use (such as cost-barriers), resulting in decreased accessibility of services for some survivors. Additional examples of barriers to help-seeking include shame and stigma, fear of retaliation from the perpetrator or community, lack of services, and discrimination and victim-blaming treatment from services providers (Kennedy et al., 2012; Tillman, Bryant-Davis, Smith, & Marks, 2010; Ullman, 2007).

Unfortunately, services are not always experienced as helpful by those who manage to access them, and not all survivors receive the same level of services (Ullman, 2007). According to Koss et al. (2017), this may be particularly true for those belonging to marginalized groups. This is problematic, as survivors from marginalized and potentially underserved groups may have increased and/or diversified support needs, due to co-occurring difficulties and inequalities, that may also compound the consequences of sexual victimization. For example, ethnic minority survivors may also be affected by societal trauma that predates the trauma of sexual assault (e.g. racism) (Bryant-Davis et al., 2009; Kennedy et al., 2012). At the same time, individuals who are low-income, differently-abled, gender and sexual minority, and/or ethnic and cultural minority, may be at an increased risk of sexual victimization and re-victimization (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Conroy & Cotter, 2014; Luce, Schrager, & Gilchrist, 2010; Rothman, Exner, & Baughman, 2011; Ullman & Najdowski, 2011). Thus, concerns about the adequacy and equity of existing support models have been raised by some academics and advocates (e.g. Koss et al., 2017; White, Sienkiewicz, & Smith, 2019).

In sum, some survivors of SA may face greater or unique barriers to accessing and benefitting from services, and, as a result, remain particularly underserved by formal support systems. Understanding who is underserved and why they are underserved is thus of great importance for the field. To date, minimal research efforts have been made to systematically synthesize the available evidence pertaining to these issues. Therefore, the present literature review aims to identify characteristics of survivors who may be particularly underserved by formal support systems following SA. A greater understanding of the person-level factors that may decrease these survivors’ access to, and satisfaction with, formal support systems may lead to knowledge that can be used to improve service delivery for underserved survivors. Due to the nature of the research aim, the present literature review is conducted as a scoping review. Since women are the main consumers of SA services, this review is focused on the experience of individuals who identify as women.

1. Method

The following sections are structured according to the five stages for conducting scoping reviews delineated by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and further developed by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (2010).

1.1. Stage 1 and stage 2: identifying the research question and identifying relevant studies

The research question guiding the present scoping review is: What characterizes survivors who may be particularly underserved by formal support systems when attempting to obtain help following a sexual assault, and why are they underserved?

First, a review protocol was developed according to the guidelines provided in the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., 2018). During this stage, a series of informal and preliminary searches were conducted in PROSPERO and other databases to avoid overlap, refine the initial research question, and identify relevant search terms (text words and index terms). Second, a systematic search was conducted in the following databases in January of 2019 and repeated in March of 2020: Embase, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Scopus. The search string included more than 100 terms and was organized into three facets/blocks (see Supplementary Material). Facet 1 contained variations of the term sexual assault (e.g. sexual assault OR sexual violence OR rape). Facet 2 contained terms related to ‘underserved’ (e.g. underserv* OR marginaliz* OR barrier* OR disparit*). Facet 3 contained terms related to formal support systems (e.g. formal support OR help seek* OR rape crisis cent* OR medical care OR criminal justice).

1.2. Stage 3: study Selection

1.2.1. Study selection process

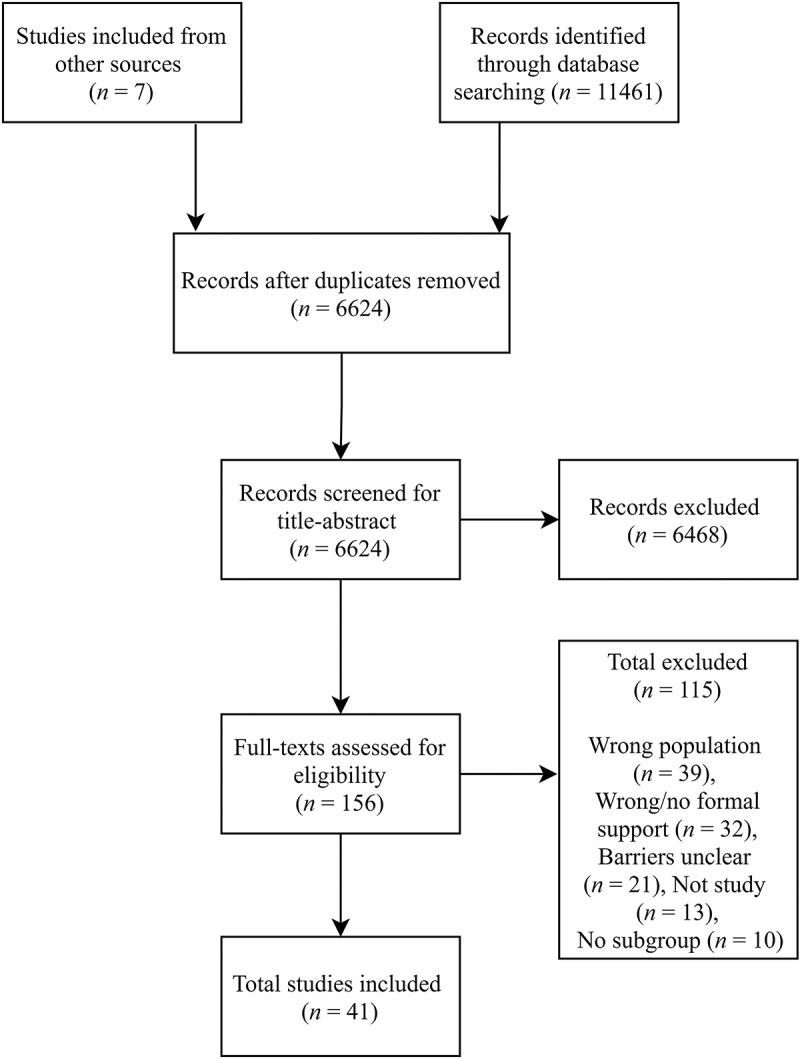

Figure 1 provides an overview of the selection of studies. In total, 10,214 records were retrieved from the database searches. After duplicate removal, 5,940 remained for screening. Title-Abstract screening was performed independently by the first and fifth author (see eligibility criteria below). Disagreements were discussed and resolved by the same authors, and 547 studies remained. At this stage, the eligibility criteria were re-evaluated based on increased familiarity with the existing literature and further restricted, as is common for scoping reviews (Levac et al., 2010). A second round of Title-Abstract screening was performed by the first and fourth author, resulting in 124 studies for full-text assessment, of which 27 were found eligible for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by the same authors. The search was repeated in March 2020 to identify studies published since the original search date. In total, 1,247 new records were retrieved, of which 677 remained after duplicate removal. Screening was performed independently by the first and fourth author, and 25 potentially relevant studies remained for full-text screening of which seven studies were included. Finally, seven additional studies not identified through the database searches were retrieved from other sources (e.g. screening the reference lists of papers that met inclusion criteria).

Figure 1.

Flow chart

1.2.2. Eligibility criteria

Empirical studies published in scientific journals or grey literature in English since 2000 were included if they reported on a) women aged 15+, who utilized or attempted to utilize formal support systems in Western countries in response to adult SA or b) experts or service providers working with this group. The year 2000 was chosen to ensure comprehensiveness yet reflect current models of service provision. We applied a broad definition of ‘women’ and thus studies on trans women and non-binary people were included. Studies including trans men were also eligible if clustered together with trans women. Studies of males, children, child sexual abuse only, unknown victimization status, and those focused exclusively on transgender men were excluded.

Since we were interested in survivor-system interactions, the studies also had to include ‘formal support systems’, which was defined as public or private institutions that cater to survivors of SA (e.g. police, emergency departments, SARCs, Rape Crisis Centers (RCCs)). Services that were, by definition, restricted to only certain subpopulations (e.g. campus services, military services) or focused on attrition and conviction rates in SA cases were excluded, however. Following Merriam-Webster’s dictionary (2020), ‘underserved’ was defined as ‘provided with inadequate service’, which was conceptualized to include the quality and not only quantity of services received. Studies were therefore included if the results indicated that a given subpopulation of survivors encountered additional or unique barriers to accessing and benefitting from services; studies that did not identify potentially underserved survivors based on these criteria were thus excluded from the present review. Thus, person-level factors such as demographics and how they potentially relate to systemic barriers were of interest (e.g. how financial vulnerability relates to characteristics of services used, such as costs). Survivors who did not attempt to access services for unknown reasons or due to intrapsychic barriers alone were therefore not eligible for inclusion. While intrapsychic factors such as shame, not labelling the event as sexual assault, and other emotional and cognitive concerns might very well keep survivors from reaching out to services in the first place, the current review sought to fill a different gap in the literature by focusing specifically on ways that service-seeking survivors may still be underserved. For the purpose of this review, assault characteristics were not considered person-level factors.

1.3. Stage 4 and 5: charting the data and reporting the results

As can be seen in Table 1, data about the origin, aim, population, method, and conclusions was extracted from each study. Data extraction was conducted by the first author and verified by the fourth author. Finally, a narrative synthesis of the included studies is presented in the results section.

Table 1.

Overview of studies included in the current review (N = 41)

| Authors, yr. & origin | Aim | Population | Method | Findings relevant to review | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abavi et al., 2020. Canada. | To explore barriers to accessing counselling for sexual assault (SA). |

52 adult female survivors (age N/A) of SA | Qualitative (online forum) | Some survivors reported being unable to afford counselling. | 3 |

| Ackerman et al., 2006. USA. | To identify characteristics associated with return visits among women presenting for post-assault care. | 812 female survivors of SA 15+ | Quantitative (medical records) |

Homelessness, psychiatric diagnosis & older age (50 y+) was associated with significantly less follow-up visits. | 3, 5, 7 |

| Akinsulure-Smith, 2014. USA. | To explore barriers faced by migrants seeking counselling for conflict related sexual violence (SV). | 1 counsellor, displaced African female survivors of conflict-related SV (N = N/A, age N/A) | Qualitative (case studies, clinical experience) | Western models of intervention alone may not be appropriate or adequate to meet the needs of forced migrants. | 1 |

| Alvidrez et al., 2011. USA. | To examine ethnic differences in follow up among women presenting at a hospital for post-assault care. | 104 female survivors of SA (18+) | Quantitative (clinical interview and clinic charts) | Despite higher treatment needs, Black women were significantly less likely than White women to engage in treatment. | 1 |

| Anderson & Overby, 2020. USA. | To explore barriers to formal support faced by service providers, who are also survivors of SV. | 19 female and gender nonconforming (GNC) survivors of SV |

Qualitative (interviews) | Participants identified the cost/perceived costs of services as a barrier to accessing support. | 3 |

| Bailey & Barr, 2000. UK. | To investigate the use of policies on conducting investigations of sex crimes against people with LD. | 24 police forces | Quantitative (survey) | Policies for sexual crimes against people with disabilities were lacking (70% police forces did not have one (n = 17)). | 2 |

| Bows, 2018. UK. | To explore practitioner views on supporting older survivors of sexual abuse (60+). | 23 practitioners working with older survivors of sexual abuse | Qualitative (interviews) | Age-related factors complicated service utilization and provision. Gaps in service provision were identified (e.g. a lack of collaboration across sectors). | 7, 1 |

| Brooker & Durmaz, 2015. UK. | To survey SARCs about their work in relation to mental health. | 25 SARCs | Quantitative (survey) | 40% of clients are already known to mental health services (N = 14). Almost two-thirds of SARCs report problems in referring on to mental health services (N = 24). | 5 |

| Burgess & Hanrahan, 2004. USA. | To investigate issues in the management of elder sexual abuse. | Experts (e.g. investigators) with experience with older SA survivors (N = N/A) | Qualitative (125 case studies of elder sexual abuse) | Participants believe older survivors of SV receive inadequate evidentiary exams, treatment and services. | 7 |

| DeLeon, 2017. USA. | To explore barriers to mental health service use experienced by black college-aged SA survivors. | 20 campus- and community-based mental health providers working with SA | Qualitative (interviews) | Black college-aged SA survivors experience cultural barriers to treatment and reporting (e.g. lack of diverse staff). | 1 |

| Du Mont et al., 2011. Canada. | To investigate health care providers perceptions of challenges to maintaining an HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) programme for SA survivors. | 132 providers working with survivors of SA | Mixed methods (survey and interviews) | A lack of accommodation to client needs was identified, including 1) administering PEP to aboriginal and remote clients 2) servicing clients who have low reading skills and non-English speakers. | 1 |

| Du Mont, Kosa, Abavi et al., 2019. Canada. | To evaluate SA centres responses to transgender survivors of SA. | 27 SA programme leaders | Quantitative (questionnaire) | Barriers to providing trans-affirming care was identified and all 27 programme leaders felt that the staff would benefit from training in the care of transgender persons. | 4 |

| Du Mont, Kosa, Solomon et al., 2019. Canada. | To evaluate the level of competence among nurses engaged in the care of transgender persons in SA centres. | 95 nurses in SA centres | Quantitative (questionnaire) | 73.1% of nurses reported having little or no expertise in caring for transgender clients (N = 93, n = 68). | 4 |

| Frantz et al., 2006. USA. | To evaluate rape crisis, SA, and domestic violence services’ compliance with Americans with Disabilities Act. |

Surveys of physical accessibility (N = 65) and programmatic accessibility (N = 54) at services | Quantitative (surveys) | Although great variability existed between services, all programmes fell short of full compliance. | 2 |

| Fraser-Barbour, 2018. Australia. | To identify ways to effectively support people with intellectual disabilities (ID) who are experiencing sexual and/or physical abuse. | 7 professionals working across disability and violence sectors1 | Qualitative (interviews) | Barriers to utilization of mainstream violence services for people with ID included unavailable services and limited knowledge about ID among staff working within these organizations. | 2 |

| Fraser-Barbour et al., 2018. Australia. | To identify ways to effectively support people with ID who are experiencing sexual and/or physical abuse. | 7 professionals working across disability and violence sectors1 | Qualitative (interviews) | Participants reported that professionals lack awareness of ways to effectively support people with ID. Participants also perceived people with ID to have little or limited autonomy after reporting the abuse. | 2 |

| Hawkins et al., 2009. Canada. | To explore formal help-seeking among Aboriginal women with HIV/AIDS and SV victimization histories. | 20 aboriginal women (18+) with HIV/AIDS and experience of SV | Qualitative (interviews) | Participants reported experiences of stigma and discrimination in health care settings based on their cultural identity and HIV-status. | 1, 3 |

| Hendriks et al., 2018. Belgium. | To asses 15 hospital-based health services for survivors of SA. | 60 professionals caring for SA survivors2 | Qualitative (interview/survey) | Only a minority of clinics (n = 3) tune their protocols based on the survivor’s gender identity and sexual orientation. | 4 |

| Holly & Horvath, 2012. UK. | To report the initial findings from a project seeking to increase support for survivors of domestic and SA with a dual-diagnosis. | Service leads were interviewed in 3 focus groups (N = N/A) and surveyed (N = N/A). | Mixed methods (surveys and interviews) | Mechanisms for sharing information between organizations (mental health, substance use and violence sector) and making appropriate referrals appears unnecessarily complicated and very restrictive. | 5, 6 |

| Goodfellow et al., 2003. Australia. | To explore access to justice among survivors of SA with cognitive impairment. | 200 SA workers and people involved in the CJS including police | Qualitative (interviews) | Participants believe the CJS fails to meet the needs of survivors with cognitive impairments. | 2 |

| Jancey et al., 2011. Australia. | To explore professionals’ perceptions of SA management practices in a healthcare setting. | 27 professionals | Mixed methods (questionnaires) | All participants agreed that there was a lack of appropriate services available to indigenous and culturally and linguistically diverse groups. | 1 |

| Jordan et al., 2019. USA. | To identify barriers to service use for transgender people accessing domestic violence/SV programmes. | 10 transgender advocates in domestic violence/SV programmes | Qualitative (interviews) | Several barriers to service use for trans survivors were identified including ‘trans-exclusionary’ policies at services. | 4 |

| Kalmakis, 2011. USA | To report the experiences of women who were sexually assaulted and struggled with substance misuse. | 8 female SA survivors (18+) with substance misuse issues | Qualitative (interviews) | Participants felt unable to access needed support. | 6 |

| Kattari, Walls, & Speer, 2017. USA. | To examine experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender and GNC individuals. | 2,424 adult (18+) transgender individuals at rape crisis centres (RCCs)3 | Quantitative (secondary analysis) | Disability and lower annual income were significantly associated with discrimination at RCC. | 2, 3, 4 |

| Kattari, Walls, Whitfield et al., 2017. USA. | To examine experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender and GNC individuals. | 2424 adult (18+) transgender individuals accessing RCCs3 | Quantitative (secondary analysis) | Significantly higher rates of discrimination were experienced by transgender People of Colour and Latino transgender individuals compared to their white counterparts. | 1, 4 |

| Keilty & Connelly, 2001. Australia. | To explore barriers to reporting sexual abuse to police among women with ID. | 27 SA workers, 13 police officers | Qualitative (interviews) | Police require additional skills on how to effectively engage with survivors with ID. Police are not always compliant with guidelines on working with these survivors. | 2 |

| Lievore, 2005. Australia. | To explore help-seeking and survivor decision-making. | 36 female survivors of SA (19+), 55 SA service providers, 65 representatives of services. | Qualitative (interviews and “consultations”) | Individuals with disabilities, non-English speakers and indigenous women face distinct barriers to formal support (e.g. due to lack of appropriately trained interpreters). | 1, 2 |

| Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010. USA. | To explore agency directors’ opinions about effective service delivery for survivors of SA or domestic violence. | 14 domestic violence and SA agency directors4 | Qualitative (interviews) | There is a lack of bilingual staff/services and few affordable transportation options. Additional challenges were discussed (e.g. uncertainties about supporting survivors with co-occurring substance abuse and/or mental health issues). | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| Macy, Giattina, Parish et al., 2010. USA. | To investigate the challenges faced by domestic violence/SA agencies. |

14 domestic violence and SA agency directors4 | Qualitative (interviews) |

Challenges included providing welcoming services to survivors of diverse backgrounds and supporting survivors with co-occurring substance abuse and/or mental health issues. | 1, 5, 6 |

| Olsen & Carter, 2016. UK. |

To explore how SA support services respond to women with learning disabilities (LD). | 4 researchers and 8 adult women (age N/A) with LD and SV victimization | Qualitative (case study, action learning) | Survivors with LD experience barriers to obtaining support, including communication difficulties. | 2 |

| Peters, 2019. USA. |

To explore the impact of medical neoliberalism in RCCs. | 6 RCC clinicians (24+) | Qualitative (interview) | All participants wanted RCCs to be more accessible for marginalized and underserved survivors (e.g. LGBTQs), and identified barriers to achieving this goal (e.g. a lack of diverse staff). | 1, 4 |

| Scannell, 2018. USA. |

To investigate factors associated with completion of PEP. | 246 female survivors (18+) | Quantitative (medical records) | Lack of insurance was associated with significantly lower completion rates. | 3 |

| Seelman, 2015. USA. | To study discrimination against transgender and GNC individuals in health settings. | Transgender and GNC people (18+) in RCCs (N = 2424)3 | Quantitative (secondary analysis) | 4,9% of transgender/GNC individuals experience unequal treatment at RCCs (n = 104). Those who are low-income, not U.S. citizens or have sex work histories are significantly more likely to experience unequal treatment. | 1, 3, 4 |

| Sit & Stermac, 2017. Canada. | To explore how help seeking can be improved for SV survivors living in poverty. | 15 female survivors of SA (18+) living in poverty | Qualitative (interviews) | Barriers to service use included costs and prejudicial attitudes towards people living in poverty among providers. | 3 |

| Smele et al., 2019. Canada. | To examine how police respond to survivors of SA with developmental disabilities (LD). | 7 police officers/SA investigators, 8 workers at victim crisis services | Qualitative (Interviews) | Policies are not always followed and police officers lack training on SA cases involving survivors with LD. | 2 |

| Ullman & Townsend, 2007. USA. | To explore barriers to service provisions experienced by workers at RCCs. | 25 rape victim advocates working in RCCs | Qualitative (interviews) | Stereotypical views about people with disabilities, the elderly, sexual minority individuals, mental illness, and sex workers and racism against people of colour is a barrier affecting advocates’ work. There is a lack of bilingual services and services disabled survivors. Cost-barriers affect some survivors. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 |

| Vandenberghe et al., 2018. Belgium. | To evaluate the care provided to survivors of SA in 15 hospitals. | 60 health professionals caring for SA survivors2 | Qualitative (survey/interview) | Professionals had limited knowledge about care for “vulnerable groups” (defined as LGBTs, migrants and disabled people). | 1, 2, 4 |

| Vik et al., 2020. Norway. | To investigate differences in police investigations between cases of SA against women with and without vulnerability factors. |

223 female survivors (16+) | Quantitative (merged police files and medical records) | “Vulnerable victims” (mental health issues, disability or substance abuse) received borderline significant lower quality investigation compared to survivors without vulnerability. | 2, 5, 6 |

| White et al., 2019. USA. | To discuss future directions in formal responses to survivors of SA and domestic violence. | 72 leaders in the domestic violence and SA field | Qualitative (“discussions”) | There is a lack of adequate services for underserved, marginalized, and culturally specific survivors (e.g. people with disabilities, LGBTQs and members of various racial and ethnic groups). Micro-loans and substance abuse services are needed. | 1, 3, 4, 6 |

| Zweig et al., 2002. USA. | To evaluate if domestic violence and SA services focus on women facing multiple barriers. | Staff from 20 programmes focused on multibarriered women (N = N/A) | Qualitative (interviews) | Few programmes focus on survivors facing multiple barriers. The system blames multibarriered women more and takes them less seriously. | 2, 5, 6 |

| Zweig et al., 2014. USA. | To examine barriers to the medical forensic examination for survivors of SA. | 47 representatives from SA coalitions, 409 providers, American Indian survivors (N = N/A, age = N/A) | Mixed methods (surveys, interviews and “meetings”) | 78% of coalitions (N= 47) and 57% providers (N = 409) considered non-English-speaking survivors to have a somewhat or harder time obtaining exams than English-speaking survivors). | 1 |

Superscript is used to indicate studies that appear to use the same sample.

2. Results

Of the 41 studies included in the present review, 34 were published as research articles, four were reports and three were doctoral dissertations. The 41 studies included in the present review were based on 37 samples (since some studies used the same sample – see Table 1) and sample sizes ranged from six to 2,424 (but N was not always stated). Most samples consisted of SA service providers/experts alone (n = 26), while the remaining studies included survivors directly (n = 15). The majority of studies focused on community, mental health and/or medical services (n = 23), five studies focused on the CJS, and the remaining studies included both settings (n = 13). Most studies used qualitative research methods (n = 25), whereas 12 studies used a quantitative research design, and four studies adopted a mixed-methods approach. A total of 21 studies were conducted in the US, seven in Canada, six in Australia, four in the UK, two in Belgium and one in Norway. The results of the studies are divided into the following seven categories, characterizing survivors who appear to be especially underserved in the formal support systems: Ethnic and cultural minorities, Disabilities, Financial vulnerability, Sexual and gender minorities, Mental health conditions, Problematic substance use, and Older age. Of note, the terminology used in the original studies (e.g. type of disability, ethnic group) is used to report the results.

2.1. Category 1: ethnic and cultural minorities

Seventeen of the studies in the present review suggested that SA survivors from different ethnic and cultural minority groups encounter distinct or additional barriers to service utilization.

2.1.1. Survivors with language barriers

This first theme in the ethnic and cultural minority category was investigated in nine studies. Zweig, Newmark, Raja, and Denver (2014) found that SA coalitions and service providers believed that non-English-speaking survivors in the US had a somewhat or much harder time obtaining the medical forensic exam compared to English-speaking survivors. Language barriers to service utilization were also evident in other studies (e.g. insufficient bilingual services and trained interpreters) (Akinsulure-Smith, 2014; Lievore, 2005; Macy, Giattina, Montijo, & Ermentrout, 2010; Ullman & Townsend, 2007; White et al., 2019). Relatedly, Du Mont, Macdonald, Myhr, and Loutfy (2011) suggested that the literacy level required to read client handouts is inappropriate for non-English speakers. In addition to these issues, health care providers at SA services may have limited knowledge about sexual violence against migrants and refugees (Akinsulure-Smith, 2014; Vandenberghe, Hendriks, Peeters, Roelens, & Keygnaert, 2018). Furthermore, in a study of transgender individuals, migrants were almost three times more likely than US citizens to report discrimination when accessing RCCs (Seelman, 2015).

2.1.2. People of colour

The second theme of this category was investigated in eight studies from the US. Despite equivalent or higher need for services based on questionnaire scores, Black women utilized significantly fewer follow-up services compared to White women in the first year following the SA (Alvidrez, Shumway, Morazes, & Boccellari, 2011). Furthermore, the results appeared to be affected by whether the survivor and the caseworker were ethnically matched, as matched survivors were more likely to utilize services compared to those not matched. A lack of diverse staff was also perceived to be a barrier to serving SA survivors of colour among service providers interviewed in other studies (DeLeon, 2017; Peters, 2019). In particular, ethnic minority women may be reluctant to seek services from White, middle-class women who may be unable to understand their concerns (Ullman & Townsend, 2007). Racism against people of colour was perceived to be a related barrier to service utilization (Ullman & Townsend, 2007). The Kattari, Walls, Whitfield, and Magruder (2017) study of transgender people accessing RCCs also suggests that individuals of colour, multiracial individuals and Latino individuals experience significantly higher rates of discrimination from service providers compared to their White counterparts. The need for culturally appropriate services for survivors from various racial and ethnic groups was thus highlighted by service providers, leaders and directors in the domestic violence and SA field (Bows, 2018; Macy, Giattina, Parish, & Crosby, 2010; White et al., 2019).

2.1.3. Indigenous people

The final theme in this category was investigated in four studies. American Indian women exposed to SA may encounter barriers to accessing the forensic medical exam (Zweig et al., 2014). Barriers included long distances to services, lack of staff training in serving this population and racism against the American Indian community (Zweig et al., 2014). Health professionals in Australia also agreed that there is a lack of culturally appropriate SA services available to indigenous and linguistically diverse groups (Jancey, Meuleners, & Phillips, 2011). Similarly, Hawkins, Reading, and Barlow (2009) suggested that aboriginal women seeking health services for SA and HIV in Canada experience discrimination, and another Canadian study exposed challenges to administering HIV post-exposure prophylaxis to aboriginal clients residing in remote communities (Du Mont et al., 2011).

2.2. Category 2: disabilities

Fifteen of the studies in the present review suggested that survivors of SA with disabilities encounter distinct or additional barriers to service utilization. The referenced disabilities included various forms of physical disabilities and cognitive impairments. Three unique themes emerged in the disability category:

2.2.1. Availability and accessibility of services for survivors with disabilities

This first theme in the disability category was investigated in six studies. This theme included concerns about the accessibility of services for survivors with disabilities. For example, Frantz, Carey, and Bryen’s (2006) study of US violence agencies indicated that although most agencies had some common accessibility structures in place (e.g. ramps), all agencies fell short of full compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (e.g. having materials available in large print and in audio). Transportation also emerged as a key need for survivors with disabilities (Fraser-Barbour, 2018; Fraser-Barbour, Crocker, & Walker, 2018; Ullman & Townsend, 2007), but services are generally unable to accommodate clients with transportation needs (Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010). Barriers to service utilization specific to survivors with intellectual disabilities were also identified. For example, Fraser-Barbour (2018) argued that mainstream violence support services are often inaccessible to people with intellectual disabilities who disclose SA. Correspondingly, Olsen and Carter (2016) found that some survivors with learning disabilities never reported their rape to formal support systems due to communication difficulties (e.g. failing to operate automated telephone services, use of overly technical language in written material).

2.2.2. Appropriateness and adequacy of services for survivors with disabilities

Seven of the studies that discussed service needs for survivors with disabilities focused on the adequacy of care. Service providers across studies agreed that challenges in supporting people with learning disabilities in violence organizations often lay in inadequate knowledge about people with disabilities (Fraser-Barbour, 2018; Vandenberghe et al., 2018; Zweig, Schlichter, & Burt, 2002). In addition, service providers were concerned that mandatory police reporting of sexual abuse against people with cognitive impairments often robs survivors of autonomy and control over what happens after disclosing SA (Fraser-Barbour, 2018; Fraser-Barbour et al., 2018; Goodfellow & Camilleri, 2003; Lievore, 2005; Smele, Quinlan, & Fogel, 2019). Survivors with disabilities may also experience increased rates of discrimination. Among transgender individuals seeking services from RCCs, people with learning disabilities or multiple disabilitieswere almost four times more likely to report discrimination from staff, compared to those without disabilities (Kattari, Walls, & Speer, 2017). Higher rates of discrimination may also be experienced by survivors with disabilities who also belong to one or more other underserved groups. For example, Zweig et al. (2002) reported that the system blames ‘multibarriered women’ more (i.e. women with disabilities, mental health issues and/or prostitution), takes them less seriously and deems them less credible compared to women without such co-occurring problems.

2.2.3. Criminal justice responses to sexual abuse against people with cognitive impairments

This final theme was investigated in nine studies. These studies suggest that criminal justice personnel may hold stereotypical and inaccurate beliefs about people with cognitive disabilities (Keilty & Connelly, 2001), leading criminal justice personnel to disbelieve these survivors (Goodfellow & Camilleri, 2003). A lack of disability awareness training in the CJS was also noted in several studies (Fraser-Barbour et al., 2018; Goodfellow & Camilleri, 2003; Keilty & Connelly, 2001; Smele et al., 2019). These studies also suggest that the ability of criminal justice personnel to respond to survivors adequately may be further hampered by a lack of clear policies on conducting investigations of sexual crimes committed against people with learning disabilities (Bailey & Barr, 2000). For example, police investigators interviewed by Smele et al. (2019) reported that there was not a standardized method in place to determine if a survivor has a developmental disability. Even when guidelines are in place, police officers are not always compliant with existing guidelines, and support during police interviews is minimal and inconsistent (Keilty & Connelly, 2001; Lievore, 2005; Smele et al., 2019). Finally, a Norwegian study indicated that survivors with physical or intellectual disabilities may receive lower quality investigations compared to survivors without ‘vulnerability factors’ (Vik, Rasmussen, Schei, & Hagemann, 2020). Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that survivors with disabilities may be particularly underserved by the CJS.

2.3. Category 3: financial vulnerability

Eleven studies included in the present review suggested that survivors of SA who are financially vulnerable encounter distinct or additional barriers to service utilization. These studies indicated that access to support is decreased by the unaffordability of services (Abavi, Branston, Mason, & Du Mont, 2020; Anderson & Overby, 2020; Sit & Stermac, 2017; Ullman & Townsend, 2007). Survivors with limited resources residing in areas where there is a shortage of low-cost transportation systems may, furthermore, be unable to access services (Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010). In a US sample of survivors seeking post-assault care, homelessness was associated with significantly fewer return-visits to a hospital-based SA clinic (Ackerman, Sugar, Fine, & Eckert, 2006). Similarly, a lack of health insurance was associated with significantly lower completion rates of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis following SA (Scannell, 2018). In addition to decreased accessibility of services, survivors experiencing financial vulnerability may not receive the support needed, such as enhanced accommodation of basic needs (e.g. food, shelter and micro-loans) (Hawkins et al., 2009; White et al., 2019). Finally, survivors affected by financial vulnerability may experience increased rates of discrimination from service providers (Kattari, Walls, & Speer, 2017; Seelman, 2015; Sit & Stermac, 2017). For example, lower income was associated with unequal treatment among transgender individuals accessing RCCs (Kattari, Walls, & Speer, 2017; Seelman, 2015).

2.4. Category 4: sexual and gender minorities

Eleven studies in the present review suggested that SA survivors identifying as sexual minorities (e.g. lesbian, bisexual queer) and SA survivors identifying as gender minorities (e.g. transgender, non-binary, two-spirit) encounter distinct and/or additional barriers to service utilization. For example, access for transgender survivors may be limited by ‘trans-exclusionary’ policies at domestic and sexual violence advocacy organizations (Jordan, Mehrotra, & Fujikawa, 2019). When services are accessed, they may not be appropriate. A lack of knowledge about gender and sexual minorities seemingly hampered service delivery in SA clinics in Belgium (Hendriks, Vandenberghe, Peeters, Roelens, & Keygnaert, 2018; Vandenberghe et al., 2018) and Canada (Du Mont, Kosa, Abavi, Kia, & Macdonald, 2019; Du Mont, Kosa, Solomon, & Macdonald, 2019). Other studies also suggested that increased cultural sensitivity towards gender and sexual minorities is needed at services (Peters, 2019; Ullman & Townsend, 2007; White et al., 2019). For example, a sizable portion of transgender individuals experience discrimination based on their gender expression or identity at RCCs (Kattari, Walls, & Speer, 2017; Kattari, Walls, Whitfield et al., 2017; Seelman, 2015) and in the CJS (Jordan et al., 2019).

2.5. Category 5: mental health conditions

Eight studies in the present review suggested that SA survivors with post-assault or pre-existing mental health conditions encounter distinct or additional barriers to service utilization. The Brooker and Durmaz (2015) study of UK SARCs estimated that 40% of clients were already known to mental health services at intake (based on responses from SARCs that kept records hereof). According to Brooker and Durmaz (2015), clients with pre-existing mental health conditions need to receive a thorough assessment and often require specialized follow up care. Unfortunately, mental health screening is not routinely conducted and referring clients on to mainstream mental health services for needed follow-up appears unnecessarily complex (Brooker & Durmaz, 2015; Holly & Horvath, 2012). Similar issues were reported in the US. Interviews with agency directors identified uncertainties about how to best support survivors with mental health issues, due to a lack of best practices and limited financial resources (Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010; Macy, Giattina, Parish et al., 2010). Survivors with a major psychiatric diagnosis also had significantly fewer return visits to a SA clinic compared to those without (Ackerman et al., 2006). Furthermore, service providers across systems (i.e. criminal justice, medical, mental health) may have stereotypical views about survivors with mental illness, potentially impacting the quality of care provided (Ullman & Townsend, 2007; Vik et al., 2020; Zweig et al., 2002).

2.6. Category 6: problematic substance use

Seven studies in the present review suggested that survivors of SA with problematic substance use face distinct or additional barriers to service utilization. White et al. (2019) revealed that resources requested by survivors include substance abuse treatment options, indicating that survivors with co-occurring substance abuse do not always receive needed support. Indeed, women with substance misuse and histories of sexual victimization expressed feeling marginalized by the health care system and incapable of attaining the services desired (Kalmakis, 2011). A lack of refuges willing to accept survivors with active substance misuse was also identified in the UK (Holly & Horvath, 2012). When services are accessed, survivors with problematic substance use may not receive adequate and holistic support (Zweig et al., 2002). For example, uncertainties remain about how to best support survivors with substance abuse issues (Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010; Macy, Giattina, Parish et al., 2010). A Norwegian study also indicated that survivors with present or former substance abuse are not provided with the same level of services in the CJS as survivors without ‘vulnerability factors’ (Vik et al., 2020). Finally, a US study suggested that compared to women who did not disclose illicit substance use, women who self-reported cocaine use were significantly less likely to complete treatment at a hospital-based SA clinic.

2.7. Category 7: older age

Four studies in the present review suggested that SA survivors of older age encounter distinct or additional barriers to service utilization. Numerous challenges to supporting older survivors were identified in interviews with staff at RCCs and SARCs working with this group (e.g. supporting older survivors in counselling with age-related conditions such as dementia or mobilizing support for older survivors belonging to minority groups) (Bows, 2018; Ullman & Townsend, 2007). Furthermore, a lack of collaboration between sexual violence services and age-related organizations was believed to hamper service delivery for this population (Bows, 2018). As a result of these challenges, staff working with this population believed that elderly individuals are less likely to complete a forensic examination and receive adequate treatment following SA (Burgess & Hanrahan, 2004). Older women may also be less likely to sustain contact with formal supports. For example, Ackerman et al. (2006) found that women aged 50–79 were significantly less likely to seek follow-up care at a SA clinic compared to women aged 15–19.

3. Discussion

The present review sought to identify characteristics of support-seeking survivors of SA who may be underserved by formal support systems in Western countries. Through a systematic literature search of five databases, 41 eligible studies were identified, resulting in seven main categories that characterize underserved survivors: Ethnic and cultural minorities, Disabilities, Financial vulnerability, Sexual and gender minorities, Mental health conditions, Problematic substance use and Older age. Similar barriers to service utilization were identified across the seven categories. These barriers included limited access to formal support, inadequate service delivery, insufficient training and awareness, inappropriate or discriminatory responses to a group’s characteristics and uncertainty about how to best support survivors from specific populations.

Intersectional theory may provide a useful framework to interpret the findings of the present review. According to an intersectional perspective, each person occupies a social position made up of multiple and intersecting identities, resulting in different privileges and constraints (Crenshaw, 1991). As illustrated by the findings of the present review, an individual’s access to support and the type of support needed may thus be determined by factors such as ability, culture and class, to name a few. Several of the included studies, furthermore, illustrated how an individual may experience multiple oppressions concurrently (e.g. the study of aboriginal women seeking services for SA and HIV, in which many survivors reported using alcohol or drugs to deal with trauma and engaging in sex work to meet basic needs (Hawkins et al., 2009)). As such, and in accordance with intersectional theory, the categories of potentially underserved survivors identified in the present review are best understood as interrelated and overlapping in several important ways. This may also explain why the barriers to service utilization experienced by survivors were similar across the categories. Furthermore, the included studies indicate that individuals with multiple marginalized identities face the greatest barriers to service utilization. This point was underlined in the Bows (2018) study in which older survivors who also belonged to a minority group encountered more barriers to service use. At the same time, an intersectional perspective suggests that an individual may experience both privilege and oppression (i.e. an individual could be marginalized by ability but not by class) (Crenshaw, 1991). For this reason, an individual experiencing one of the characteristics identified in the present review may not necessarily be underserved following SA. Instead, service utilization is a complex phenomenon influenced by multiple and interacting factors.

Andersen’s behavioural model of health service use may also help to further explain survivors’ service utilization. According to the widely used model, service use is determined by factors that either predetermine, enable or suggest need of services (Andersen, 1995). Most of the barriers identified in the present review are also featured in Andersen’s (1995) model. For example, the present review indicated that financial vulnerability is a barrier for service utilization. Correspondingly, Andersen’s model suggests that an individual’s financial situation is a predisposing factor for service use. Furthermore, the model highlights that contextual and organizational factors further predispose service use (e.g. availability of services in the community, affordability of services, means of transportation). As such, barriers to SA services largely appear similar to barriers to health services in general.

3.1. Implications and recommendations

As the categories identified in the present review are interrelated, it is unlikely that the problems identified within each category can be solved individually (e.g. by creating more services designated for a specific subgroup of survivors only). Instead, formal support systems must be universally accessible to all survivors served, especially those from marginalized groups. Based on the findings from the present review and insights from intersectionality, general recommendations for future endeavours in policy, practice and research are provided.

First, a need for more ‘survivor-centered’ responses was identified across formal support systems in the present review. Being survivor-centred means listening to survivors and responding to the priorities and concerns of all served (Koss et al., 2017). However, the studies included in the present review indicate that the needs of some survivors are not being met. As such, survivors belonging to marginalized and underserved groups should be involved in the development and evaluation of services and be included in research (e.g. by using participatory methods as seen in the study by Olsen and Carter (2016), where survivors with learning disabilities collaborated in the development of an easy-read flyer).

Second, and following from this, a need for more culturally appropriate services was identified in the present review. ‘Cultural humility’/”cultural competency” involves a commitment among professionals to reflect on their own biases to better meet the needs of individuals of diverse cultural identities (Greene-Moton & Minkler, 2020; Schnyder et al., 2016; White et al., 2019). This may involve moving beyond traditional western notions of therapy by including elements from various religious and cultural practices (e.g. prayer), as suggested in several of the included studies (e.g. Akinsulure-Smith, 2014; Hawkins et al., 2009). As underscored by the findings of the present review, language used at services should be inclusive and accessible to all survivors served (e.g. by avoiding overly technical or offensive language, acquiring bilingual services and providing information in alternative formats). Furthermore, the organization should reflect the diversity of those served by hiring diverse staff at every level (Gentlewarrior, 2009), as a lack of diverse staff was cited in several of the included studies (Alvidrez et al., 2011; DeLeon, 2017; Jancey et al., 2011; Peters, 2019; Ullman & Townsend, 2007).

Third, according to the present review, the responses to survivors should be more ‘trauma-informed’. Trauma-informed care can be defined as responding to survivors in accordance with knowledge about the impacts of trauma (Reeves, 2015). Given the diverse needs and histories of survivors illustrated by the findings of the present review, formal sources of support should not only assess for sexual violence but also provide holistic and integrated services that adequately address co-occurring oppressions and psychosocial needs (Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010). However, few services seem to tailor interventions to survivors and many of the included studies suggested that referring clients on for needed follow-up was difficult (Brooker & Durmaz, 2015; Holly & Horvath, 2012; Zweig et al., 2002). This finding is in line with other recent reviews of the literature, which identified wide variations in the provision of mental health and substance abuse services at SA centres (Stefanidou et al., 2020), and found that pathways from SA services to mental health services are often difficult (Brooker, Hughes, Lloyd-Evans, & Stefanidou, 2019). In addition, psychotherapy alone may be insufficient to adequately support survivors with multiple needs as highlighted by Akinsulure-Smith (2014). Increased collaboration and coordination within the violence sector and with other agencies of importance outside the violence sector is therefore also necessary to solve the problems identified in the review (e.g. disability sector and eldercare) (White et al., 2019).

Finally, the remaining barriers discussed in the review should also be addressed in order to secure equal access for all survivors. In particular, cost barriers should be removed, survivors with transportation needs should be accommodated and all buildings must be physically accessible While a lack of funding is a constant challenge affecting agencies’ ability to remove these barriers (Koss et al., 2017; Macy, Giattina, Montijo et al., 2010; White et al., 2019), doing so should nonetheless remain a goal.

3.2. Methodological considerations

Most studies screened treated survivors of SA as a singular group and thus failed to account for potential in-group differences in service utilization. Most of the included studies were conducted through the views of service providers and, therefore, did not include survivors themselves. Together, this suggests that the survivors identified in present review are not only underserved but also under-researched. While studies conducted on service providers are valuable, the voices of women facing (multiple) disadvantage should be consulted much more in future research.

Interpretation of evidence from the included studies was complicated by numerous factors related to the quality of these studies, including lack of clear definitions. Also, most of the studies used small samples and/or recruited participants from a limited number of agencies and did not directly compare survivors’ access to or satisfaction with services. In addition, most of the studies were conducted in the US. The barriers discussed in the present review may, therefore, be more salient in some communities and countries compared to others (e.g. a financially vulnerable individual may be more likely to be underserved following SA in countries without universal health coverage). The generalizability of the findings from the present review is thus limited and cannot be used to provide estimates of the extent of the problem.

Determining which survivors are underserved also proved challenging. First, it was not easy to construct an appropriate search strategy. The goal of the study was to identify which groups of survivors are underserved; to do so, we could not use search terms such as ‘ethnic minority’ because this would be making an a priori assumption about which groups are underserved. Instead, we had to search for ‘underserved’ and variations thereof. Second, and related to this, it was difficult to develop objective eligibility criteria because the term ‘underserved’ lacks a comprehensive definition. As a result, the survivors that are considered to be underserved in the present review may not be considered to be underserved in all studies. Male survivors were excluded from this review, but male survivors may very well be underserved by existing services. Other survivor characteristics that have yet to be identified in existing research may also lead some survivors to be underserved. Future research is therefore needed to help more clearly define what is meant by the term underserved (e.g. when should a service be considered (in)adequate?) and to confirm current findings.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the scoping review indicated that survivors of SA belonging to various historically marginalized groups encounter multiple barriers to service utilization and, as a result, are underserved. In order to ensure equal access to high-quality services for all survivors served in the formal support system, service delivery should be improved. Based on the findings of the present review and insights from intersectional theory, universal recommendations for service provision were provided. Responses to survivors of SA need to be more survivor-centred, culturally appropriate and trauma-informed. It was, therefore, apparent from the findings that much more empirical work is needed about survivors belonging to marginalized and underserved groups to facilitate a deeper understanding of the help-seeking experiences and service needs of these survivors.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to thank The Council of The Danish Victims fund for their support. We would also thank Rikke Holm Bramsen for her valuable contributions to the research project.

Funding Statement

These materials have received financial support from The Council of The Danish Victims Fund (as part of a larger research project under grant no. 2017/2). The authors are responsible of the execution, content, and results of the materials. The analysis and viewpoints that have been made evident from the materials belong to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Danish Victims Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- Abavi, R., Branston, A., Mason, R., & Du Mont, J. (2020). An exploration of sexual assault survivors’ discourse online on help-seeking. Violence and Victims, 35(1), 126–15. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-18-00148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, D. R., Sugar, N. F., Fine, D. N., & Eckert, L. O. (2006). Sexual assault victims: Factors associated with follow-up care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 194(6), 1653–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinsulure-Smith, A. M. (2014). Displaced African female survivors of conflict-related sexual violence. Violence Against Women, 20(6), 677–694. doi: 10.1177/1077801214540537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez, J., Shumway, M., Morazes, J., & Boccellari, A. (2011). Ethnic disparities in mental health treatment engagement among female sexual assault victims. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 20(4), 415–425. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.568997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 1. doi: 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G. D., & Overby, R. (2020). Barriers in seeking support: Perspectives of service providers who are survivors of sexual violence. Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 1564–1582. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, H., Morgan, G., Evans, V., Fitzpatrick, S., Larasi, M., Narwal, J., & Williamson, D. (2019). Breaking down the barriers: Findings of the national commission on domestic and sexual violence and multiple disadvantage. Retrieved from https://avaproject.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Breaking-down-the-Barriers-full-report-.pdf

- Bailey, A., & Barr, O. (2000). Police policies on the investigation of sexual crimes committed against adults who have a learning disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4(2), 129–139. doi: 10.1177/146900470000400204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bows, H. (2018). Practitioner views on the impacts, challenges, and barriers in supporting older survivors of sexual violence. Violence Against Women, 24(9), 1070–1090. doi: 10.1177/1077801217732348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, C., & Durmaz, E. (2015). Mental health, sexual violence and the work of Sexual Assault Referral centres (SARCs) in England. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 31, 47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, C., Hughes, E., Lloyd-Evans, B., & Stefanidou, T. (2019). Mental health pathways from a sexual assault centre: A review of the literature. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 68, 101862. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.101862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis, T., Chung, H., & Tillman, S. (2009). From the margins to the center. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 330–357. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, A. W., & Hanrahan, N. P. (2004). Issues in elder sexual abuse in nursing homes. Nursing and Health PolicyReview, 3(1), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R., Patterson, D., & Lichty, L. F. (2005). The effectiveness of Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) programs. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(4), 313–329. doi: 10.1177/1524838005280328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen, C. C., Palesh, O. G., & Aggarwal, R. (2005). Sexual revictimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 6(2), 103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, S., & Cotter, A. (2014). Self-reported sexual assault in Canada. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/14842-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. doi: 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon, P. (2017). Campus- and Community- Based Administrators and Mental Health Providers Perspectives on Sexual Assault among College-Age Women. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Cincinatti. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/ [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont, J., Kosa, S. D., Abavi, R., Kia, H., & Macdonald, S. (2019). Toward affirming care: An initial evaluation of a sexual violence treatment network’s capacity for addressing the needs of trans sexual assault survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051988994. doi: 10.1177/0886260519889943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont, J., Kosa, S. D., Solomon, S., & Macdonald, S. (2019). Assessment of nurses’ competence to care for sexually assaulted trans persons: A survey of Ontario’s Sexual Assault/Domestic Violence Treatment Centres. BMJ Open, 9(5), e023880. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont, J., Macdonald, S., Myhr, T., & Loutfy, M. R. (2011). Sustainability of an HIV PEP program for sexual assault survivors: “Lessons learned” from health care providers. The Open AIDS Journal, 5(1), 102–112. doi: 10.2174/1874613601105010102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz, B. L., Carey, A. C., & Bryen, D. N. (2006). Accessibility of Pennsylvania’s victim assistance programs. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 16(4), 209–219. doi: 10.1177/10442073060160040201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser-Barbour, E. F. (2018). On the ground insights from disability professionals supporting people with intellectual disability who have experienced sexual violence. The Journal of Adult Protection, 20(5/6), 207–220. doi: 10.1108/JAP-04-2018-0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser-Barbour, E. F., Crocker, R., & Walker, R. (2018). Barriers and facilitators in supporting people with intellectual disability to report sexual violence: Perspectives of Australian disability and mainstream support providers. The Journal of Adult Protection, 20(1), 5–16. doi: 10.1108/JAP-08-2017-0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentlewarrior, S. (2009). Culturally competent service provision to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survivors of sexual violence. National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women. Retrieved from https://vawnet.org/material/culturally-competent-service-provision-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-survivors [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, J., & Camilleri, M. (2003). Beyond belief, beyond justice: The difficulties for victim/survivors with disabilities when reporting sexual assault and seeking justice. Disability Discrimination Legal Service. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/12155689 [Google Scholar]

- Greene-Moton, E., & Minkler, M. (2020). Cultural competence or cultural humility? Moving beyond the debate. Health Promotion Practice, 21(1), 142–145. doi: 10.1177/1524839919884912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, K., Reading, C., & Barlow, K. (2009). A qualitative study of the role of sexual violence in the lives of aboriginal women living with HIV/AIDS. Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network. Retrieved from http://librarypdf.catie.ca/ATI-20000s/26290.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, B., Vandenberghe, A. M.-J. A., Peeters, L., Roelens, K., & Keygnaert, I. (2018). Towards a more integrated and gender-sensitive care delivery for victims of sexual assault: Key findings and recommendations from the Belgian sexual assault care centre feasibility study. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 152. doi: 10.1186/s12939-018-0864-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holly, J., & Horvath, M. A. H. (2012). A question of commitment – Improving practitioner responses to domestic and sexual violence, problematic substance use and mental ill‐health. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 5(2), 59–67. doi: 10.1108/17570971211241912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jancey, J., Meuleners, L., & Phillips, M. (2011). Health professionals’ perceptions of sexual assault management. Health Education Journal, 70(3), 249–259. doi: 10.1177/0017896911406970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, S. P., Mehrotra, G. R., & Fujikawa, K. A. (2019). Mandating inclusion: Critical trans perspectives on domestic and sexual violence advocacy. Violence Against Women, 26(6–7), 531–554. doi: 10.1177/1077801219836728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmakis, K. A. (2011). Struggling to survive: The experiences of women sexually assaulted while intoxicated. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 7(2), 60–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2011.01100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, E. N., Whitfield, D. L., & Magruder, L. L. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing social services among transgender/gender-nonconforming people. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 26(3), 217–235. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2016.1242102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., & Speer, S. R. (2017). Differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing social services among transgender/gender nonconforming individuals by (dis)ability. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 16(2), 116–140. doi: 10.1080/1536710X.2017.1299661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilty, J., & Connelly, G. (2001). Making a statement: An exploratory study of barriers facing women with an intellectual disability when making a statement about sexual assault to police. Disability & Society, 16(2), 273–291. doi: 10.1080/09687590120035843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, A. C., Adams, A., Bybee, D., Campbell, R., Kubiak, S. P., & Sullivan, C. (2012). A model of sexually and physically victimized women’s process of attaining effective formal help over time: The role of social location, context, and intervention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9494-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss, M. P., Hansen, M., Anderson, E. J., Hardeberg-Bach, M., & Holm-Bramsen, R. (2020). Sexual assault. In Cheung F. M. & Halpern D. F. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the international psychology of women. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koss, M. P., White, J. W., & Lopez, E. C. (2017). Victim voice in reenvisioning responses to sexual and physical violence nationally and internationally. American Psychologist, 72(9), 1019–1030. doi: 10.1037/amp0000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievore, D. (2005). No longer silent. A study of women’s help-seeking decisions and service responses to sexual assaultle: A report prepared by the Australian Institute of Criminology for the Australian Government’s Office for Women. Retrieved from https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/archive/archive-134

- Luce, H., Schrager, S., & Gilchrist, V. (2010). Sexual assault of women. American Family Physician, 81(4), 489–495. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20148503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy, R. J., Giattina, M. C., Montijo, N. J., & Ermentrout, D. M. (2010). Domestic violence and sexual assault agency directors’ perspectives on services that help survivors. Violence Against Women, 16(10), 1138–1161. doi: 10.1177/1077801210383085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy, R. J., Giattina, M. C., Parish, S. L., & Crosby, C. (2010). Domestic violence and sexual assault services. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(1), 3–32. doi: 10.1177/0886260508329128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary . (2020). Underserved. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/underserved

- Olsen, A., & Carter, C. (2016). Responding to the needs of people with learning disabilities who have been raped: Co-production in action. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 21(1), 30–38. doi: 10.1108/TLDR-04-2015-0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbaan, V., Covers, M. L. V., Bicanic, I. A. E., Huntjens, R. J. C., & De Jongh, A. (2019). Do early interventions prevent PTSD? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of early interventions after sexual assault. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1682932. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1682932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, S. (2019). The double-edged sword of diagnosis: Medical neoliberalism in rape crisis center counseling. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umb.edu/doctoral_dissertations/432/ [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, E. (2015). A synthesis of the literature on trauma-informed care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(9), 698–709. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1025319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, E. F., Exner, D., & Baughman, A. L. (2011). The prevalence of sexual assault against people who identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual in the USA: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(2), 55–66. doi: 10.1177/1524838010390707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, M. (2018). Exploring the issues of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis and sexually assaulted individuals. Massachusetts: Northeastern University Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder, U., Bryant, R. A., Ehlers, A., Foa, E. B., Hasan, A., Mwiti, G., … Yule, W. (2016). Culture-sensitive psychotraumatology. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 31179. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.31179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seelman, K. L. (2015). Unequal treatment of transgender individuals in domestic violence and rape crisis programs. Journal of Social Service Research, 41(3), 307–325. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2014.987943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sit, V., & Stermac, L. (2017). Improving formal support after sexual assault: Recommendations from survivors living in poverty in Canada. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, 088626051774476. doi: 10.1177/0886260517744761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smele, S., Quinlan, A., & Fogel, C. (2019). Sexual assault policing and justice for people with developmental disabilities. Violence and Victims, 34(5), 818–837. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-18-00041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanidou, T., Hughes, E., Kester, K., Edmondson, A., Majeed-Ariss, R., Smith, C., … Lloyd-Evans, B. (2020). The identification and treatment of mental health and substance misuse problems in sexual assault services: A systematic review. Plos One, 15(4), e0231260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman, S., Bryant-Davis, T., Smith, K., & Marks, A. (2010). Shattering silence: Exploring barriers to disclosure for African American sexual assault survivors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11(2), 59–70. doi: 10.1177/1524838010363717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. E. (2007). Mental health services seeking in sexual assault victims. Women & Therapy, 30(1–2), 61–84. doi: 10.1300/J015v30n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. E., & Najdowski, C. J. (2011). Vulnerability and protective factors for sexual assault. In Violence against women and children: Vol 1. Mapping the terrain (pp. 151–172). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/12307-007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. E., & Townsend, S. M. (2007). Barriers to working with sexual assault survivors. Violence Against Women, 13(4), 412–443. doi: 10.1177/1077801207299191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe, A., Hendriks, B., Peeters, L., Roelens, K., & Keygnaert, I. (2018). Establishing Sexual Assault Care Centres in Belgium: Health professionals’ role in the patient-centred care for victims of sexual violence. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 807. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3608-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik, B. F., Rasmussen, K., Schei, B., & Hagemann, C. T. (2020). Is police investigation of rape biased by characteristics of victims? Forensic Science International: Synergy, 2, 98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.fsisyn.2020.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walby, S., Olive, P., Towers, J., Francis, B., Strid, S., Krizsán, A., … Armstrong, J. (2015). Stopping rape. Bristol: Police Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, J. W., Sienkiewicz, H. C., & Smith, P. H. (2019). Envisioning future directions: Conversations with leaders in domestic and sexual assault advocacy, policy, service, and research. Violence Against Women, 25(1), 105–127. doi: 10.1177/1077801218815771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J., Newmark, L., Raja, D., & Denver, M. (2014). Accessing sexual assault medical forensic exams: Victims face barriers. Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/accessing-sexual-assault-medical-forensic-exams [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, J., Schlichter, K. A., & Burt, M. R. (2002). Assisting women victims of violence who experience multiple barriers to services. Violence Against Women, 8(2), 162–180. doi: 10.1177/10778010222182991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.