Abstract

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in persons with dementia (PWD) are common and can lead to poor outcomes, such as institutionalization and mortality, and may be exacerbated by sensory loss. Hearing loss is also highly prevalent among older adults, including PWD.

Objective

This study investigated the association between hearing loss and NPS among community dwelling patients from a tertiary memory care center.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Participants of this cross-sectional study were patients followed at the Johns Hopkins Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center who underwent audiometric testing during routine clinical practice between October 2014 and January 2017.

Outcome Measurements

Included measures were scores on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) and the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD).

Results

Participants (n = 101) were on average 76 years-old, mostly female and white, and had a mean MMSE of 23. We observed a positive association between audiometric hearing loss and the number of NPS (b = 0.7 per 10 dB; 95% CI: 0.2, 1.1; t = 2.86; p = 0.01; df = 85), NPS severity (b = 1.3 per 10 dB; 95% CI: 0.4, 2.5; t = 2.13; p = 0.04; df = 80), and depressive symptom severity (b = 1.5 per 10 dB; 95% CI: 0.4, 2.5; t = 2.83; p = 0.01; df = 89) after adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics. Additionally, the use of hearing aids was inversely associated with the number of NPS (b = −2.09; 95% CI −3.44, −0.75; t = −3.10; p = 0.003; df = 85), NPS severity (b = −3.82; 95% CI −7.19, −0.45; t = −2.26; p = 0.03; df = 80), and the number of depressive symptoms (b = −2.94; 95% CI: −5.93, 0.06; t = 1.70; p = 0.05; df = 89).

Conclusions

Among patients at a memory clinic, increasing severity of hearing loss was associated with a greater number of NPS, more severe NPS, and more severe depressive symptoms, while hearing aid use was associated with fewer NPS, lower severity, and less severe depressive symptoms. Identifying and addressing hearing loss may be a promising, low-risk, non-pharmacological intervention in preventing and treating NPS.

Keywords: Hearing loss, dementia, neuropsychiatric symptoms, hearing care, cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) such as depression, agitation, and apathy are associated with dementia, and are highly prevalent in community settings, with estimates ranging from 61-97%.1–3 Many studies have found that NPS are associated with multiple poor health outcomes in persons with dementia (PWD), including institutionalization, prolonged hospitalizations, higher care burden, morbidity, and mortality.4,5 NPS are also common among individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), with prevalence estimates ranging 35–85%, and have been associated with worse cognitive performance and functional disability.6 For caregivers, NPS are consistently one of the strongest contributors to caregiver burden and depression.7 A high financial burden compounds the physical and psychological toll of NPS, with a lifetime cost of care estimated at over $350,000 in 2020.8 However, management of NPS remains challenging, with limited effectiveness of pharmacological approaches, and non-pharmacological interventions serving as first-line treatments that can be difficult to implement.9,10

In conceptualizing potential non-pharmacological interventions for NPS, the unmet needs model depicts how neurodegeneration and multiple contributory factors related to the patient, caregiver, and environment may result in NPS.11,12 Age-related changes in sensory function, such as hearing loss, may worsen dementia progression and worsen NPS, as PWD face more difficulty in communicating their needs and interacting with their environment. However, hearing loss is underreported and undertreated among older adults generally, with over 20 million older adults in the United States with untreated hearing loss.13 Only one in seven with hearing loss use a hearing aid.14

Both hearing loss and dementia are associated with age, and, though prevalence data are limited, estimates of hearing loss among PWD range from 60% to over 90% among patients at memory clinics.15–18 Few studies have examined the relationship between hearing loss and NPS. These studies19–21 have generally been limited to small case studies, have used unvalidated measures of NPS, and/or relied upon subjective, self-reported hearing loss which may not accurately reflect the hearing of older adults.22 Objective, audiometric assessments of hearing for PWD have rarely been used, though several studies have demonstrated such data can be reliably collected from PWD, including through mobile, tablet-based technologies.23,24 Understanding the potential role of hearing loss in NPS management may provide an additional and complementary non-pharmacological approach to optimizing the health and well-being of older adults with cognitive impairment.

This study examines the association between objective, audiometric hearing loss and NPS. We assessed cross-sectionally the number of NPS, NPS severity, and depressive symptom severity in relationship to hearing status in patients presenting to a tertiary care memory clinic with varying degrees of cognitive impairment. We hypothesized that hearing loss is independently associated with the number and severity of NPS.

METHODS

Study Participants

This chart review was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute’s Institutional Review Board and complies with the Declarations of Helsinki. Participants were consecutive patients evaluated at the Johns Hopkins Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center between October 2014 and January 2017 who underwent audiometric and neurocognitive testing as part of routine clinical care. Demographic information, number of comorbidities, medications and psychotropic medications, memory disorder diagnosis, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, questionnaire data from the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q), and Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) are all recorded as part of routine clinical care and manually obtained from the electronic health record.

Audiometric Assessment

As part of a routine clinic visit, pure-tone audiometric testing was performed using either (1) insert earphones and a portable audiometer (Interacoustics AS608 Screening Audiometer; Denmark) from October 2014 to May 2015 or (2) TDH-50P supra-aural headphones (Telephonies; Farmingdale, NY) and a mobile, tablet-based audiometer (SHOEBOX™ Audiometry; Ottawa, ON) from October 2016 to January 2017.24 All audiometric testing was performed following American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards for maximum permissible noise levels using continuous ambient noise monitoring. Manual technician-administered protocols followed the Hughson-Westlake method using behavioral response. The two screening audiometers and associated protocol have been previously used to obtain thresholds in quiet environments with older adults with cognitive impairment25 and no differences between the cohorts were detected in sensitivity analyses based on audiometer type. Hearing loss was defined according to the speech-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) of hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear. The severity of hearing loss was categorized into binary and ordinal variables based on the World Health Organization criteria: “normal hearing” ≤ 25 dB, “any HL” ≥ 25 dB, “mild HL” = 25.0 – 39.9 dB, “moderate HL” 40 – 59.9 dB or “severe HL” ≥ 60.0 dB. For this study, the latter two categories were collapsed into “moderate or greater HL” due to the low number of participants (n=3) observed with severe HL.

Measures of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

The NPI-Q and CSDD were used to measure NPS. The NPI-Q measures the presence and severity of 12 neuropsychiatric symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, dysphoria/depression, anxiety, euphoria/elation, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behaviors, night-time behavioral disturbances and appetite/eating disturbances.26 An informant, generally a family caregiver for the patient, confirms the presence or absence of individual NPS and grades their corresponding severity on a three-point scale (mild, moderate, severe). Total NPI-Q scores range from 0 to 12 for the number of symptoms and 0 to 36 for total symptom severity, with higher scores representing more severe symptoms. Of the 101 participants in the study sample, 95 (94%) had complete information on number of NPS, while five informants did not complete the severity section of the questionnaire, resulting in 90 (89%) responses for severity.

Informants completed the CSDD, a 19-item measure of depressive symptom severity in five main domains: mood-related signs, behavioral disturbance, physical signs, cyclic functions, and ideational disturbance.27 Each item is rated from 0 to 2 (absent, mild to intermittent, or severe), with scores ranging from 0 to 38. A total score >18 indicates definite major depression, greater than 10 a probable major depression, and less than 6 the absence of significant depressive symptoms. Two informants were missing responses, resulting in a sample size of 99.

For participants with missing questionnaire data at the time of hearing screening, questionnaires completed within one year of the visit were used. For those with more than one questionnaire during a visit, questionnaires completed by the informant with the closest relationship to the subject per the clinic note were utilized. For questionnaire single items in which informants indicated “unable to evaluate” but completed other items on the form, a score of zero was assigned for the respective item for the purposes of analysis. Questionnaires with all items missing were treated as missing. For the NPI-Q, at most four zeros were imputed for symptoms (delusions and motor disturbances) with “unable to evaluate” responses. For CSDD, zeros were imputed for single items with “unable to evaluate” responses with imputations ranging from 6% to 29% of total observations for multiple physical complaints and diurnal variation in mood items, respectively. A more detailed description of the number of values imputed per item is shown in the supplement (Supplemental Table 1). No notable patterns of missingness were found during data abstraction and analysis.

Covariates

Covariates were selected for their known relationship with either hearing loss or NPS. Demographic characteristics, such as sex (male vs female), race/ethnicity (white vs black), and age were included given their established associations with hearing loss.28 The analytical cohort was restricted to those who self-identified as black or white given a small number of patients who identified as “Asian” or “other” (n=9). Current hearing aid use was also examined. Factors potentially associated with NPS included cognitive function as measured by Mini-Mental State Examination score (MMSE; by serial sevens), education (less than high school, high school or equivalent, more than high school), number of comorbidities as a proxy of general medical health (as listed on the clinic note on the day of hearing screening and during the initial history & physical), and a count of psychotropic medications (including SSRIs, non-SSRIs, typical and atypical antipsychotics, and benzodiazepines).29,30

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort stratified by hearing status, using Pearson’s chi-squared tests (for categorical variables) or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (for numerical variables). Multiple regression models were used to analyze the association between hearing loss and the number of NPS, total NPS severity, and individual NPS as measured by NPI-Q and depressive symptom severity as measured by total CSDD score.

All regression models were adjusted for demographic and clinical characteristics known to be associated with hearing loss and/or NPS, including age as a continuous variable, sex, race/ethnicity, education, number of comorbidities, hearing aid user, MMSE scores, and number of psychotropic medications.28–30 Regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (version 15.1, Stata Corp).

RESULTS

A total of 101 participants aged 49-93 years (mean: 76.3, SD: 8.7) had concurrent audiometric and questionnaire data available for analysis (Table 1). 66% of patients had clinically significant hearing loss: ranging from mild (44%) to moderate (20%) to severe (3%). 20% of the study participants were hearing aid users. Demographic characteristics between the three hearing loss groups (none, mild, and moderate or greater) were similar, including sex, race/ethnicity, and education, while greater hearing loss was observed among older participants. The distribution of cognitive functioning was similar between those with and without hearing loss, with an average MMSE of 23. The majority were diagnosed with either mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (27%, n = 27) or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) (52%, n = 53).

Table 1.

Demographics and health-related characteristics of participants by hearing status

| Hearing Loss | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | All (n = 101)a | None (n = 34) | Mild (n=44) | Moderate or greater (n = 23) | df | Diff. across HL groups p-valueb |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 76.3 (8.7) | 71.0 (6.8) | 76.6 (8.3) | 83.4 (6.6) | 2 | <0.001 |

| Age Categories, % (n) | ||||||

| <70 | 22.8 (23) | 44.1 (15) | 18.2 (8) | 0.0 (0) | 4 | <0.001 |

| 70-74 | 21.8 (22) | 29.4 (10) | 18.2 (8) | 17.4 (4) | ||

| ≥75 | 55.5 (56) | 26.5 (9) | 63.6 (28) | 82.6 (19) | ||

| Female, % (n) | 56.4 (57) | 61.8 (21) | 52.3 (23) | 56.5 (13) | 2 | 0.70 |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | ||||||

| White | 82.2 (83) | 82.4 (28) | 84.1 (37) | 78.3 (18) | 2 | 0.84 |

| Black | 17.8 (18) | 17.7 (6) | 15.9 (7) | 21.7 (5) | ||

| Education, % (n) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 11.9 (12) | 17.7 (6) | 4.6 (2) | 17.4 (4) | 6 | 0.28 |

| High school or equivalent | 22.8 (23) | 17.7 (6) | 29.6 (13) | 17.4 (4) | ||

| College or more | 65.4 (66) | 64.7 (22) | 65.9 (29) | 65.2 (15) | ||

| Hearing-Related | ||||||

| Degree of hearing loss (PTA), mean (SD)c | 31.4 (13.3) | 17.7 (4.7) | 32.1 (4.3) | 50.4 (8.3) | 4 | <0.001 |

| Hearing aid user, % (n) | 19.8 (20) | 5.9 (2) | 15.9 (7) | 47.8 (11) | 2 | <0.001 |

| Health-Related | ||||||

| Number of medical comorbidities, mean (SD) | 7.7 (3.9) | 7.0 (3.6) | 7.6 (3.5) | 8.9 (5.0) | 2 | 0.19 |

| Cerebrovascular accident, % (n) | 14.9 (15) | 14.7 (5) | 9.1 (4) | 26.1 (6) | 2 | 0.18 |

| Depression, % (n) | 35.6 (36) | 38.2 (13) | 43.2 (19) | 17.4 (4) | 2 | 0.10 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 20.8 (21) | 17.7 (6) | 13.6 (6) | 39.1 (9) | 2 | 0.04 |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 67.3 (68) | 55.9 (19) | 75.0 (33) | 69.6 (16) | 2 | 0.20 |

| MMSE scores, mean (SD) | 23.1 (4.4) | 24.1 (3.8) | 22.5 (4.6) | 22.7 (4.9) | 0.28 | |

| Cognitive Diagnosis | ||||||

| Mild cognitive impairment, % (n) | 26.7 (27) | 32.4 (11) | 27.3 (12) | 17.4 (4) | 4 | 0.17 |

| Alzheimer’s dementia or related dementias, % (n) | 52.5 (53) | 58.8 (20) | 43.2 (19) | 60.9 (14) | ||

| Other cognitive disorder, % (n) | 20.8 (21) | 8.8 (3) | 29.6 (13) | 21.7 (5) | ||

| Number of medications, mean (SD) | 9.3 (5.2) | 9.1 (6.2) | 9.3 (4.1) | 9.8 (5.8) | 2 | 0.13 |

| Number of psychotropic medications, mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.6) | 2 | 0.14 |

| SSRI usage, % (n) | 31.5 (35) | 35.9 (14) | 32.6 (15) | 23.1 (6) | 2 | 0.54 |

| Non-SSRI usage, % (n) | 13.5 (15) | 12.8 (5) | 19.6 (9) | 3.9 (1) | 2 | 0.17 |

| Typical antipsychotic usage, % (n) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| Atypical antipsychotic usage, % (n) | 7.2 (8) | 12.8 (5) | 4.4 (2) | 3.9 (1) | 2 | 0.24 |

| Benzodiazepine usage, % (n) | 9.9 (11) | 10.3 (4) | 13.0 (6) | 3.9 (1) | 2 | 0.45 |

| NPI-Q, mean (SD) d | ||||||

| Number of symptoms | 4.2 (2.8) | 4.2 (2.3) | 4.1 (3.0) | 4.7 (3.3) | 0.77 | |

| Severity | 7.3 (6.2) | 7.0 (5.4) | 7.3 (6.8) | 7.9 (6.5) | 0.88 | |

| CSDD, % (n)e, f | ||||||

| Definite major depression | 10.2 (10) | 9.4 (3) | 9.09 (4) | 13.6 (3) | 2 | 0.81 |

| Probable major depression | 32.7 (32) | 40.6 (13) | 31.8 (14) | 22.7 (5) | 2 | |

| Depressive symptoms | 30.6 (30) | 25.0 (8) | 29.6 (13) | 40.9 (9) | 2 | |

| Absence of significant symptoms | 27.3 (27) | 24.2 (9) | 29.6 (13) | 22.7 (5) | 2 | |

Abbreviations: PTA = pure-tone average, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, CSDD = Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia

The number of participants varies by the questionnaire. For the NPI-Q, there were 95 responses for symptoms and 90 for severity. For the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, there were 99 total responses.

Comparisons were conducted between the hearing loss groups using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA for continuous variables or Pearson’s chi-square tests categorical variables.

Degree of hearing loss was defined according to the speech-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) of hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear. Per WHO criteria, “no hearing loss” ≤ 25 dB, “mild hearing loss” = 25.0 – 39.9 dB, “moderate or greater HL” ≥ 40.0 dB.

Among the 95 respondents for the NPI-Q, five informants did not provide severity ratings, and thus there were 90 responses for severity.

There were 99 respondents for the CSDD.

A CSDD total score >18 indicates definite major depression, > 10 probable major depression, ≥ 6 depressive symptoms, and < 6 the absence of significant depressive symptoms. Two informants were missing responses, resulting in a sample size of 99.

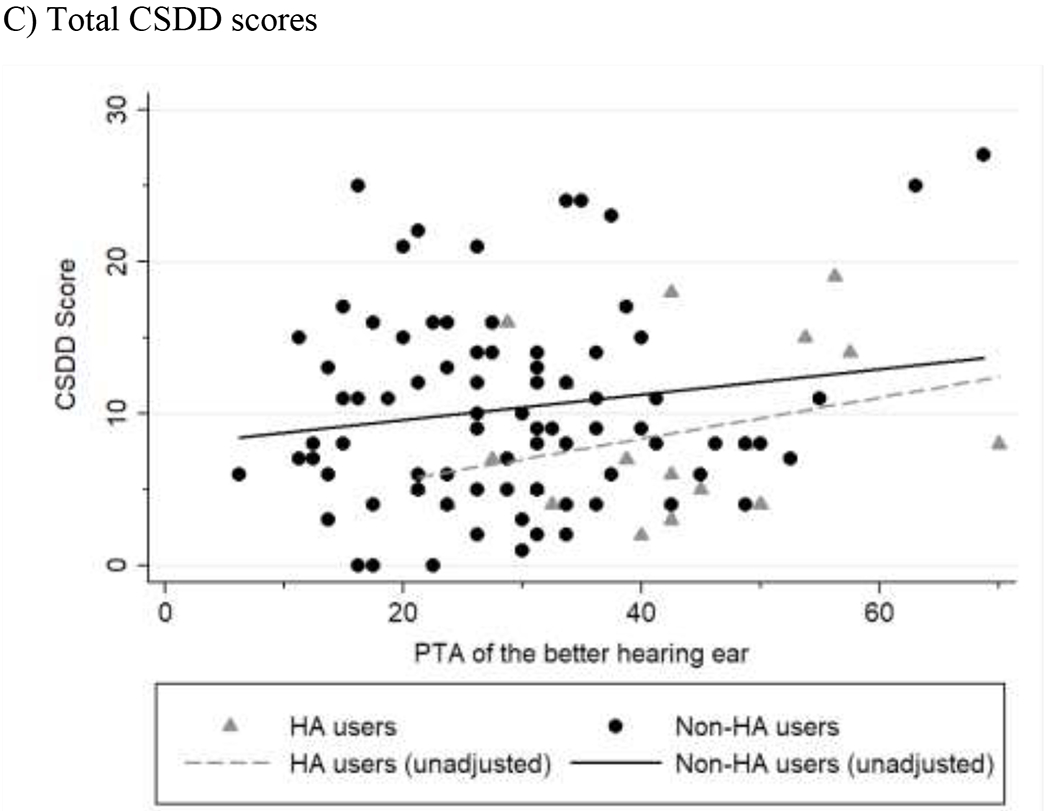

We graphically explored the relationship between hearing loss and the number of NPS, total NPS severity, and total CSDD scores without adjusting for covariates (Figure 1). All three variables were positively correlated with worse hearing. Hearing aid users generally experienced fewer NPS, less severe NPS, and less severe depressive symptoms than non-hearing aid users across all PTA levels.

Figure 1.

Associations between hearing loss and NPI-Q or CSDD scores.

Scatterplots for A) NPI symptoms, B) NPI severity, and C) CSDD scores are shown. Hearing aid users are displayed as gray triangles. Best fit lines were calculated for hearing aid users and non-users. The degree of hearing loss is calculated based on to the speech-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) of hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear.

We evaluated the association between hearing loss and NPS while adjusting for clinically relevant covariates (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, number of comorbidities, hearing aid use, MMSE scores, and number of psychotropic medications, hearing loss was positively associated with the number of NPS and severity of NPS. For every 10 dB increase in PTA (worse hearing), nearly an additional NPS and 1.3-point increase in severity were observed. Hearing aid use was inversely associated with both the number of NPS and total NPS severity. On average, hearing aid users reported two fewer symptoms and nearly 4 points lower total severity of NPS than non-users, while adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics, including degree of cognitive impairment. Associations between hearing loss and the presence of individual NPS were also calculated, and after adjustment were significant for hallucinations, agitation/aggression, euphoria, nighttime behavior, and appetite.

Table 2.

Association between hearing loss and number of NPS, severity of NPS, and depressive symptoms, adjusted

| Number of NPS (n = 95) | Severity of NPS (n = 90) | CSDD Score (n = 99) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | p valueb | Coefficient (95% CI) | p valueb | Coefficient (95% CI) | p valueb | |

| Degree of hearing loss (PTA)a | 0.07 (0.02, 0.11) | 0.005 | 0.13 (0.01, 0.25) | 0.04 | 0.15 (0.04, 0.25) | 0.006 |

| Age | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.01) | 0.07 | −0.13 (−0.29, 0.05) | 0.16 | −0.13 (−0.28, 0.02) | 0.08 |

| Female | −0.74 (−1.75, 0.26) | 0.15 | −1.65 (−4.13, 0.83) | 0.19 | −1.80 (−4.01, 0.39) | 0.11 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Black | 0.45 (−0.90, 1.80) | 0.51 | 0.88 (−2.41, 4.17) | 0.60 | 0.60 (−2.35, 3.55) | 0.69 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| High school or equivalent | 1.06 (−0.66, 2.78) | 0.22 | 1.26 (−2.87, 5.39) | 0.55 | 3.19 (−0.55, 6.93) | 0.09 |

| College or more | 0.46 (−1.10, 2.02) | 0.56 | 0.36 (−3.40, 4.12) | 0.85 | 0.90 (−2.47, 4.28) | 0.60 |

| Hearing aid user | −2.09 (−3.44, −0.75) | 0.003 | −3.82 (−7.19, −0.45) | 0.03 | −2.94 (−5.93, 0.06) | 0.05 |

| MMSE | −0.20 (−0.32, −0.08) | 0.001 | −0.34 (−0.63, −0.05) | 0.02 | −0.30 (−0.57, −0.04) | 0.03 |

| Number of psychotropic medications | 1.50 (0.85, 2.15) | <0.001 | 3.12 (1.56, 4.69) | <0.001 | 4.00 (2.56, 5.43) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: PTA = pure-tone average, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination, CSDD = Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia

Degree of hearing loss was defined according to the speech-frequency pure-tone average (PTA) of hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better-hearing ear. Per WHO criteria, “no hearing loss” ≥ 25 dB, “mild hearing loss” = 25.0 – 39.9 dB, “moderate or greater HL” ≤ 40.0 dB

P-value associated to the two-tailed t-statistic for the corresponding regressor, with 85, 80, and 89 degrees of freedom, respectively, for the number and severity of NPS and CSDD score.

We also evaluated whether hearing loss was independently associated with depressive symptoms as an individual NPS (Table 2). Utilizing a similar multiple regression model, we found a positive association between hearing loss and total CSDD scores, while adjusting for demographic and clinical covariates. Hearing aid users, on average, had a three point lower total CSDD score than non-users, after multivariable adjustment.

DISCUSSION

In this study of 101 older adults with cognitive impairment, audiometric hearing loss was independently associated with increased number of NPS and severity of NPS as well as increased depressive symptom severity after adjustment for demographic and health-related characteristics. Though many participants in this study had MCI or mild ADRD, as suggested by an overall mean MMSE of 23, over 90% exhibited at least one NPS. For every 10 dB increase in hearing loss severity, older adults with cognitive impairment were more likely to experience an additional neuropsychiatric symptom, 1.3-point increase in total NPS severity, and 1.5-point increase in depressive symptom severity. Moreover, hearing aid use was independently associated with over two fewer NPS, a 3.8-point decrease in total NPS severity, and 3-point decrease in depressive symptom severity. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association of NPS with audiometric data among older adults with cognitive impairment as compared to self- or proxy-reported hearing loss.21,31

Our findings contribute to the understanding of the role of hearing in NPS among PWD. One community-based study additionally found that among older adults who self-reported hearing loss, greater rates of NPS were observed among older adults with major neurocognitive disorders, though no association was found for those with mild neurocognitive disorders.21 Yamada et. al. reported nursing home residents with proxy-rated sensory loss had a significantly higher incidence of new behavioral symptoms at 12-month follow-up.31 Such studies depended on self- or proxy-reported hearing loss, versus audiometric data, though the reliability of self- and proxy-reported hearing difficulties have not been established for older adults with cognitive impairment. Self-reported measures of hearing loss may reflect the severity of cognitive impairment, as those with cognitive impairment may find communication difficult and mistakenly attribute it to hearing difficulties. Similarly, proxy-reported measures may be influenced by caregiver factors, such as communication strategies, that may also confound the relationship to NPS. The potential biases that arise from subjective measures are minimized with this study’s use of pure-tone audiometry. Regarding depression, our findings are consistent with findings among older adults in general, where audiometric hearing loss has been associated with depression.32–34 However, our understanding of the association between hearing loss and depression, as an individual NPS, among older adults with cognitive impairment is limited.

While limited, several studies have considered the use of hearing aids to manage NPS. An ongoing international prospective study has shown promising results with hearing and vision intervention in PWD, including modest improvements in behavioral disturbances.35 In a month-long pilot trial of providing older adults with cognitive impairment and hearing loss with an over-the-counter amplification device and accompanying communication strategies, mean changes in NPI-Q and CSDD scores improved but not significantly, though some individuals experienced significant improvement in NPS after treatment.36 Another small study of adults with dementia found reductions in caregiver-identified problem behaviors two months after hearing aid treatment.20 However, Adrait et. al. conducted a multicenter double-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial with a semi-crossover procedure over 12 months.37 The study found that hearing aids for older adults with hearing loss and dementia did not lead to significant improvements in NPS, though considerable limitations in methodology have been noted, including the lack of evidence-based hearing aid fitting protocol that did not ensure improved audibility for participants.38 Hearing aids have also been found to be protective against depressive symptoms in older adults in general.39,40Among PWD, Allen et. al. found no reduction in depression, as measured by CSDD, after 6 months of hearing aid use.41 The equivocal results of these studies, taken together with our findings, warrant further investigation.

Our study has several limitations. As a cross-sectional analysis, we cannot assess for a causal relationship between hearing loss and NPS. Study participants comprised a convenience sample at a tertiary academic center, limiting generalizability. Selection bias often results from sampling in a chart review. We also used a static imputation method for missing responses, rather than multiple imputation or other methodology that adjusts for the uncertainty of missing data. Though hearing aid users had fewer NPS symptoms, less severe NPS, and less severe depressive symptoms, hearing aid use may be a surrogate measure of other factors, such as an individual’s ability and willingness to access and use hearing care that may not have been accounted for in our analysis, including socioeconomic status and caregiver support. In addition, the ability to use hearing aids may reflect how hearing aid users may have been differentially affected by their dementia in ways not captured by our adjusted measures. Data regarding the consistency and duration of hearing aid use were unavailable and thus not explored in this study.

This study demonstrates an association between objective, audiometric hearing loss and the number and severity of NPS and suggests that hearing aid use may potentially mitigate these observed associations. Whether the reduction in the number and severity of NPS through sensory management, specifically hearing aids, can be reproduced and sustained in a randomized controlled trial remains to be seen. Sensory health, including hearing, may play a critical role in exacerbating NPS that has traditionally gone unrecognized and frequently unaddressed among PWD. Hearing care and other sensory management strategies may present promising low-risk, non-pharmacological interventions that can in-part address the unmet needs of older adults with cognitive impairment. These strategies may also facilitate the effectiveness of other non-pharmacological interventions to support the health and well-being of PWD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The present study explored the relationship between audiometric hearing loss and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) and severity among older adults at a tertiary care memory clinic with varying degrees of cognitive impairment.

Worse audiometric hearing was associated with increased number of NPS, more severe NPS, and more severe depressive symptoms. Hearing aid users experienced fewer NPS, less severe NPS, and fewer severe depressive symptoms.

Hearing loss may worsen NPS in older adults with cognitive impairment, and ensuring access to effective communication may be a low-risk intervention in managing NPS.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

CGL has received grant support (research or continuing medical education) from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Aging, Associated Jewish Federation of Baltimore, Weinberg Foundation, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Ortho-McNeil, Bristol-Myers, Novartis, the National Football League (NFL), Elan, Functional Neuromodulation, and the Bright Focus Foundation; he is a consultant or adviser for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Eisai, Novartis, Forest, Supernus, Adlyfe, Takeda, Wyeth, Lundbeck, Merz, Lilly, Pfizer, Genentech, Elan, the NFL Players Association, NFL Benefits Office, Avanir, Zinfandel, BMS, Abvie, Janssen, Orion, Otsuka, Servier, Astellas, Roche, Karuna, SVB Leerink, Maplight, and Axsome and he has received honorariums or travel support from Pfizer, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, and Health Monitor. FRL is a consultant to Boeringher-Ingelheim and Autifony Inc. FRL reports being a consultant to Frequency Therapeutics, speaker honoraria from Caption Call, and being the director of a research center funded in part by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear Ltd to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. FRL and CLN are board members of the nonprofit Access HEARS. CLN is a member of the board of trustees for the Hearing Loss Association of America. This study was supported in-part by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIA K23AG059900, CLN; NIA R01AG057725 and Roberts Family Fund, ESO; NIA P30AG066507, CGL; NIA K23DC016855 SKM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Front Neurol. 2012;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferri CP, Ames D, Prince M, 10/66 Dementia Research Group. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in developing countries. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16(4):441–459. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, et al. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Backhouse T, Camino J, Mioshi E. What Do We Know About Behavioral Crises in Dementia? A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2018;62(1):99–113. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clyburn LD, Stones MJ, Hadjistavropoulos T, Tuokko H. Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. JGerontolB Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55(1):S2–13. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.1.s2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monastero R, Mangialasche F, Camarda C, Ercolani S, Camarda R. A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2009;18(1): 11–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.2.p112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. Published online March 10, 2020. doi: 10.1002/alz.12068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, Yu J-T, Wang H-F, et al. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86(1): 101–109. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2020–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.36918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Algase DL, Beck C, Kolanowski A, et al. Need-driven dementia-compromised behavior: An alternative view of disruptive behavior. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 1996;11(6): 10–19. doi: 10.1177/153331759601100603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mamo SK, Nieman CL, Lin FR. Prevalence of Untreated Hearing Loss by Income among Older Adults in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1812–1818. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien W, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):292–293. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nirmalasari O, Mamo SK, Nieman CL, et al. Age-related hearing loss in older adults with cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(1): 115–121. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold M, Lightfoot LA, Hnath-Chisolm T. Hearing loss in a memory disorders clinic. A specially vulnerable population. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(9):922–928. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550090134019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011; 66(10): 1131–1136. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(9):879–886. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leverett M Approaches to Problem Behaviors in Dementia. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 1991;9(3-4):93–105. doi: 10.1080/J148V09N03_08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer CV, Adams SW, Bourgeois M, Durrant J, Rossi M. Reduction in caregiver-identified problem behaviors in patients with Alzheimer disease post-hearing-aid fitting. J Speech Lang Hear Res JSLHR. 1999;42(2):312–328. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4202.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiely KM, Mortby ME, Anstey KJ. Differential associations between sensory loss and neuropsychiatric symptoms in adults with and without a neurocognitive disorder. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(2):261–272. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiely KM, Gopinath B, Mitchell P, Browning CJ, Anstey KJ. Evaluating a dichotomized measure of self-reported hearing loss against gold standard audiometry: prevalence estimates and age bias in a pooled national data set. J Aging Health. 2012;24(3):439–458. doi: 10.1177/0898264311425088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uhlmann RF, Larson EB, Rees TS, Koepsell TD, Duckert LG. Relationship of hearing impairment to dementia and cognitive dysfunction in older adults. JAMA. 1989;261(13):1916–1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pletnikova A, Reed NS, Amjad H, et al. Identification of Hearing Loss in Individuals With Cognitive Impairment Using Portable Tablet Audiometer. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups. 2019;4(5):947–953. doi: 10.1044/2019_PERS-SIG8-2018-0018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, et al. Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2119–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steinberg M, Corcoran C, Tschanz JT, et al. Risk factors for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(9):824–830. doi: 10.1002/gps.1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferreira AR, Simões MR, Moreira E, Guedes J, Fernandes L. Modifiable factors associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing homes: The impact of unmet needs and psychotropic drugs. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;86:103919. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2019.103919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada Y, Denkinger MD, Onder G, et al. Impact of dual sensory impairment on onset of behavioral symptoms in European nursing homes: results from the Services and Health for Elderly in Long-Term Care study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015; 16(4): 329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shukla A, Reed N, Armstrong NM, Lin FR, Deal JA, Goman AM. Hearing Loss, Hearing Aid Use and Depressive Symptoms in Older Adults - Findings from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Neurocognitive Study (ARIC-NCS). J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. Published online October 19, 2019. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Association of Audiometric Age-Related Hearing Loss With Depressive Symptoms Among Hispanic Individuals. JAMA Otolaryngol-- Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2): 132–139. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gopinath B, Wang JJ, Schneider J, et al. Depressive symptoms in older adults with hearing impairments: the Blue Mountains Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1306–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02317.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adrait A, Perrot X, Nguyen M-F, et al. Do Hearing Aids Influence Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia and Quality of Life in Hearing Impaired Alzheimer’s Disease Patients and Their Caregivers? J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2017;58(1):109–121. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mamo SK, Palmer CV. Treatment of Age-Related Hearing Loss in Persons with Alzheimer’s Disease. Published online 2018. https://www.j-alz.com/content/treatment-age-related-hearing-loss-persons-alzheimers-disease [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mamo SK, Nirmalasari O, Nieman CL, et al. Hearing Care Intervention for Persons with Dementia: A Pilot Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leroi I, Simkin Z, Hooper E, et al. Impact of an intervention to support hearing and vision in dementia: The SENSE-Cog Field Trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatiy. 2020;35(4):348–357. doi: 10.1002/gps.5231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Acar B, Yurekli MF, Babademez MA, Karabulut H, Karasen RM. Effects of hearing aids on cognitive functions and depressive signs in elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011. ;52(3):250–252. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mener DJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, Chen D, Lin FR. Hearing loss and depression in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9): 1627–1629. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen NH, Burns A, Newton V, et al. The effects of improving hearing in dementia. Age Ageing. 2003;32(2): 189–193. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solheim J, Hickson L. Hearing aid use in the elderly as measured by datalogging and self-report. Int J Audiol. 2017;56(7):472–479. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1303201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.