Abstract

Heart rate variability (HRV) captures the change in timing of consecutive heart beats and is reduced in individuals with depression and anxiety. The present study investigated whether typically-developing children without clinically recognized signs of depression or anxiety showed a relationship between HRV and depressive or anxiety symptoms. Children aged 9-14 years (N=104) provided three minutes of cardiac signal during eyes closed rest and eyes open rest. The association between high frequency HRV, low frequency HRV, root mean square of the successive differences (RMSSD), and pNN20 versus depressive symptoms (NIH Toolbox and Child Behavior Checklist) was investigated. Results partially confirm our hypothesis, with pNN20 positively correlated with the self-reported depression measure of loneliness while controlling for age, sex, social status, and physical activity. The association was stronger in male participants. However, there is no consensus in the literature about which HRV measures are associated with depressive symptoms in healthy children. Additional studies are needed which reliably account for variables that influence HRV to establish whether certain HRV measures can be used as an early marker for depression risk in children.

Keywords: Heart rate variability, healthy children, depression, loneliness, pNN20, RMSSD

Introduction

Depression, left undiagnosed and untreated in adolescents, can lead to tragic results. In 2017, the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Kann et al., 2018) reported that over the previous 12 months, 22.1% of high school females and 11.9% of high school males had considered suicide. From that same report, 9.3% of females and 5.1% of males attempted suicide. With suicide being the second leading cause of death in people 10-24 years (Heron, 2018), it is imperative an objective, reliable measure of depression is discovered. As suicide rates across the country continue to increase (Stone et al., 2018), relying on self-report or waiting for children to speak up or act out is no longer tenable.

The primary cause of suicidality is clinical depression. Depression is prevalent in children, with 12.8% of adolescents between the ages of 12-17 diagnosed (Ahrnsbrak, 2017). Children with depression experience feelings of hopelessness, depressed mood, fatigue, and anhedonia (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). People with depression are at risk of suicide and also deal with physical symptoms associated with the disorder such as pain, digestive issues, and a change in the body’s inflammatory response (Bizik et al., 2014; Trivedi, 2004). With a significant portion of the population affected by depression, simple, objective diagnostic measures could be of use.

Alterations in heart rate variability (HRV) have been reported in a broad range of disorders including prematurely born infants (Javorka et al., 2017), and individuals with clinical depression (Kemp & Quintana, 2013), diabetes, and heart disease (Xhyheri, Manfrini, Mazzolini, Pizzi, & Bugiardini, 2012). HRV is defined as the difference in intervals between consecutive heartbeats and reflects the activity of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), specifically vagal nerve control of the parasympathetic nervous system (Porges, 1995). The ANS is comprised of two different branches, the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. Heart rate and blood pressure reduction and increases in digestive system activity are mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system response is commonly referred to as the “fight or flight” response because it is activated during physically or mentally stressful events. This response includes increases in heart rate, cardiac output, blood flow to muscles, pupil dilation and a decrease in digestive system activity (Clifford, 2002). The interaction between these two branches is responsible for the autoregulation of the cardiovascular system. In people with normal HRV, there is a balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system that allows the body to adapt to cognitive and environmental stressors (Thayer & Lane, 2000). Accordingly, HRV is indicative of the body’s flexibility to react to external events.

In a recent meta-analysis, Kemp et al. (2010) reported that reduced HRV is consistently associated with increased symptom severity in adults with clinical depression. It has been proposed that lower HRV identified in adults with depressive symptoms is caused by either decreased parasympathetic or increased sympathetic activity (Michels et al., 2013; Task Force, 1996), as well as the inability of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system to properly adapt to the environment (Porges, 2007). Furthermore, HRV is further implicated as an indicator of depressive symptoms based on the response to treatment in diagnosed patients (Chien, Chung, Yeh, & Lee, 2015).

As an important extension to the prior work, several cross-sectional studies in children have evaluated time- and frequency domain measures of HRV as a measure of vagal regulation. For example, inpatient adolescent females diagnosed with depression were found to have significantly lower time-domain HRV than the control group (Tonhajzerova et al., 2009). These findings were later replicated by the same group in an independent sample using time- and frequency domain measures such as root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) and high frequency HRV (HF-HRV) (Tonhajzerova et al., 2010). Results have been less consistent with non-clinical levels of depression. The review by Paniccia et al. (2017) reported that several cross-sectional studies found no significant correlations between self-reported depression symptoms and various measures of HRV. Whereas, Blood et al. (2015) reported a significant association between self-reported depression symptoms and frequency domain measures of HRV in a healthy sample of 127 adolescents aged 10-17 years. Vazquez et al. (2016) reexamined this same sample of healthy children a year later and found that the associations were still present among the 73 adolescents who remained in the study. From studies looking into the correlation between HRV and emotional regulation, HF-HRV appears to be one of the more sensitive indicators of depression.

The present study examined the association between spectral and time-domain HRV measures and depressive symptoms among typically-developing children 9-14 years of age who provided three minutes of artifact free resting heart rate data. The two spectral metrics of HRV were relative power of low and high frequency components. The time-domain measures used were the RMSSD and pNN20 (the proportion of the number of normal RR [peak to peak]-interval differences of successive normal RR-intervals greater than 20ms and divided by the total number of RR-intervals). The aim of the study was to determine if these HRV measures act as a correlate for depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that higher self-reported scores related to depression in healthy, typically-developing children would correlate with lower HRV measures.

Methods

Participants

Participants were a part of the Developmental Chronnectogenomics (“DevCog”) study, a large, longitudinal study about brain development in adolescents with the goal of recruiting 200 typically developing children aged 9-14 years of age. Children were recruited through events, such as farmers’ markets, science fairs, and school presentations and through Craigslist ads and a radio ad for the greater Albuquerque, NM metropolitan area. Parents provided written informed consent and children voluntarily participated in the study and provided formal assent. The protocol was approved by an accredited IRB in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We report on 104 children who had heart rate data collected at their baseline visit. Participants were excluded if parents reported that the child had a psychological or neurological condition or if the child was prenatally exposed to drugs or alcohol based on parental report. At the visit, artifact free heart rate data collected in a seated position and complete questionnaires were required for inclusion in this report. In the end, 93 of the 104 children, 47 males and 46 females, met these criteria. Each of the 93 participants provided three minutes of artifact-free heart rate data for both eyes closed rest and eyes open rest. Three participants were excluded because artifact free data could not be extracted from their visit. Another eight participants were excluded because they did not complete the self-report questionnaires. The order of data collection (eyes closed vs eyes open) was chosen based on the randomly generated participant number (odd = closed first, even = open first).

Measures

Cardiovascular Response

Heart rate was collected with the Elekta Neuromag VectorView magnetoencephalography (MEG) machine housed at The Mind Research Network (MRN). The electrocardiogram was collected with two bipolar leads located under the left and right collarbone. The electrode sites were rubbed with Nuprep abrasive scrub and then cleaned with an alcohol wipe. Quik-Gel electrolyte was placed on the electrodes and they were adhered to the skin using surgical tape. During MEG data collection 5 minutes of eyes open rest (view a fixation cross) and 5 minutes of eyes closed rest data were obtained. Bipolar ECG channel data was collected simultaneously with the MEG data and was extracted using a custom Python script which converted the ECG data to a text file. From the 5-minute segments, 3 minutes of ECG signal during eyes closed rest and 3 minutes of ECG signal during eyes open rest was extracted. The sampling rate was 1000 Hz.

The ECG text files were imported into the QRSTool software (Allen, Chambers, & Towers, 2007). Heartbeats were initially detected using the threshold tool. Afterwards, erroneously detected heartbeats were manually removed and missed heartbeats were manually corrected following the methodology described in the QRSTool manual. If heartbeats in the ECG channel were obscured due to movement, MEG channels from the temporal region (where heartbeat artifact in MEG data is most prominent) were referred to in order to identify the timing of the heartbeats. Heart rate artifact is often clearly visible in the temporal MEG channels (See Figure 1). The ECG channel was the main source of analysis, while the MEG channels provided supplemental information. Once the data were cleaned of all incorrectly detected heartbeats, interbeat intervals (IBIs) were extracted using the QRSTool software. Data with excessive movement artifact or ectopic beats were excluded. This limited the initial dataset to 101 participants. The IBI values were imported into the Kubios standard 3.0 software (Tarvainen, Niskanen, Lipponen, Ranta-Aho, & Karjalainen, 2014) which was used to derive the time domain and spectral measures of HRV. The time domain measures investigated were RMSSD and pNN20. Prior literature indicates that the pNN20 is more robust to confounds relative to the default pNN50 provided by the Kubios software (Mietus, Peng, Henry, Goldsmith, & Goldberger, 2002). The spectral measures investigated were low frequency (0.04 – 0.15 Hz) and high frequency (0.15 – 0.4 Hz) bands.

Figure 1.

MEG channels and ECG channel (bottom red channel) to demonstrate the clear presence of heart rate artifact in MEG channels during data collection. One event is highlighted by the vertical green line in the MEG channels (e.g. MEG 1533, MEG 1531, MEG1543, MEG 1541).

There were three participants whose data did not end up being usable. The analysis required three minutes of consecutive, artifact-free data for eyes closed and eyes open rest. If the electrode leads lost contact at any point during the rest task it corrupted the ECG readings. With heart rate being a peripheral measure of the DevCog study, MEG data collection was not paused if the ECG channel lost signal. There were times when heart rate was also not clearly discernable in the temporal MEG channels, which meant supplemental analysis for the three subjects was not possible. Figure 2 displays the number of participants excluded and the reason for the exclusion.

Figure 2.

Breakdown of participants excluded due to unusable data.

Emotional Measures

Children and their parents completed the NIH Emotion Toolbox (Salsman et al., 2013). The measures of interest for this study were Sadness and Loneliness. Sadness is assessed using an 8-item fixed-length self-report questionnaire and Loneliness contains 5-items. Each emotion is assessed using a 5-point scale ranging from “never” to “almost always”. The questionnaire is scored using item response theory (IRT) methods. Higher scores were indicative of increased sadness and loneliness in the child (Gershon et al., 2013).

Parents also completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991). We examined the anxious/depressed and the withdrawn/depressed scores. A high score on measures from the CBCL has been widely accepted as clinically meaningful, specifically for scores that are over 70 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The participants completed the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A) (K. C. Kowalski, Crocker, P. R., & Donen, R. M, 2004). The questionnaire asks children to recall their physical activity for the last 7 days. The summary score is derived from eight items, each on a 5-point scale, and provides an estimation of physical activity (K. C. Kowalski, Crocker, & Kowalski, 1997).

Data Analysis

IBM SPSS software (version 20, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) was used to complete analysis. The main study variables were the T-scores of the Sadness and Loneliness surveys, the spectral measures of HRV, HF and LF bands, and time domain measures, RMSSD and pNN20, collected during rest with eyes closed and eyes open. HRV measures were transformed using the natural logarithm to approximate normality. To examine the effects of age, sex, physical activity and eyes closed vs. eyes open an ANCOVA was performed where sex and eyes closed/open were included as between subject factors and age, SES and physical activity were included as covariates. A two tailed, bivariate correlation with the Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to examine correlations between HRV and emotional measures. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons correction.

Results

To verify the validity of utilizing MEG channel data to confirm the location of unclear heartbeats in the ECG channel, we performed HRV analysis on both ECG and MEG channels from 10 children (Supplementary Figure 1). As suggested from the similarity of results shown in Supplementary Figure 1, little variability was obtained between HRV using either ECG or MEG channel data. The average ICC value across the 10 subjects was 1.0. Results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Heart rate extracted from ECG and MEG channels of 10 different participants

| Participant | ECG HR | MEG HR |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 68.52 | 68.51 |

| P2 | 97.01 | 97.02 |

| P3 | 109.56 | 109.56 |

| P4 | 68.91 | 68.91 |

| P5 | 80.72 | 80.74 |

| P6 | 96.75 | 96.75 |

| P7 | 93.71 | 93.71 |

| P8 | 86.9 | 86.89 |

| P9 | 93.91 | 93.91 |

| P10 | 70.79 | 70.79 |

| ICC | 1.0 |

Note: Heart rate extracted from the ECG channel and one MEG channel of 10 different participants. QRS Tool only provides values estimated to two decimal places, so a more precise comparison was not possible. As shown, the heart rate taken from the same participant but from different channels, ECG vs. MEG, was highly congruent. The last row includes Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of heart rate extracted from the ECG and MEG channels.

Of the 104 participants who had an MEG scan, we were able to identify 6 minutes (3 minutes eyes closed and 3 minutes eyes open) of high quality heartbeat signal (from either the ECG or MEG channel) in 101 children. The age ranged from 9.09 to 14.93 years. The distribution across age demonstrated that there was no systemic difference in the quality of ECG signal with age. Mean scores for the study variables are included in Table 2. Signal quality was consistent across sexes with only 2 males and 1 female excluded due to poor signal quality.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for study variables

| Participant (N=101) variables | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 11.74 (1.80) |

| Sadness | 48.81 (11.06) |

| Loneliness | 51.91 (10.46) |

| Anxious/Dep. | 51.86 (6.37) |

| Withdrawn/Dep. | 53.15 (4.74) |

| Closed_LF | 44.24 (18.71) |

| Closed_HF | 55.62 (18.72) |

| Open_LF | 44.73 (17.64) |

| Open_HF | 55.11 (17.57) |

| Closed_RMSSD | 70.43 (37.35) |

| Open_RMSSD | 68.43 (38.17) |

| Closed_pNN20 | 67.15 (20.38) |

| Open_pNN20 | 66.69 (21.53) |

Note: LF=low frequency HRV; HF =high frequency HRV

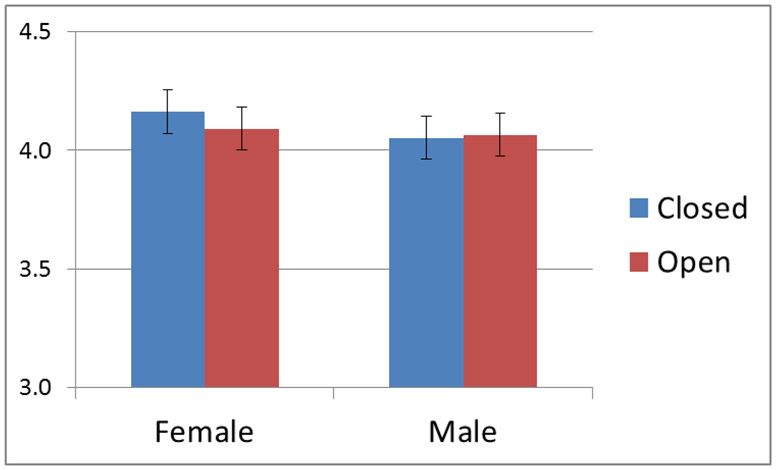

An ANOVA examining the effects of age, sex and order of rest paradigms revealed no significant correlation with age (p >0.1) for any of the study variables. A two-way analysis of variance for RMSSD yielded an interaction for eyes closed/open and sex, F(1) = 6.21, p = .015, such that the average RMSSD was higher for girls when eyes were closed and lower when girls had their eyes open. The interaction is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A plot of the interaction between sex and eyes closed/open with RMSSD.

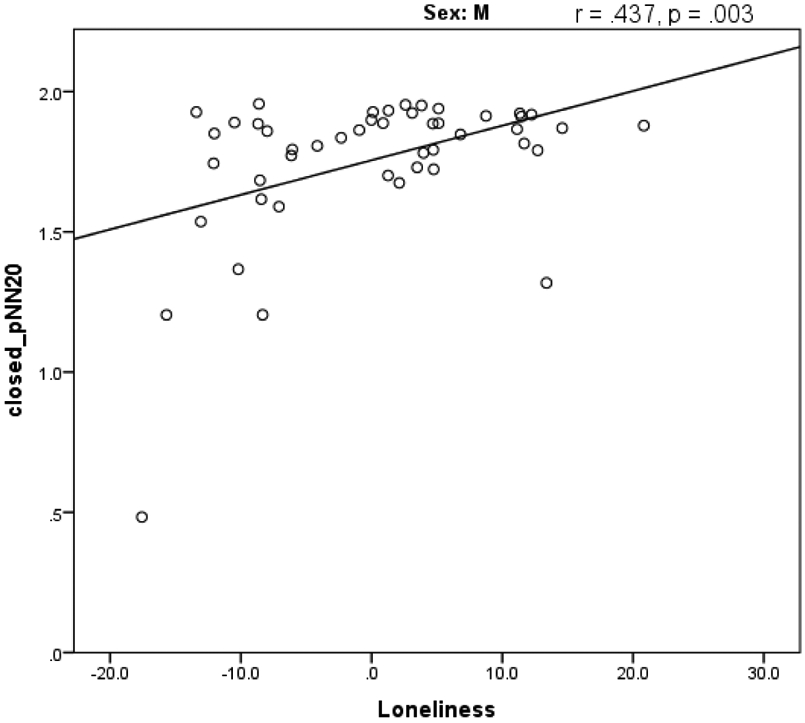

There was a significant positive correlation between the self-reported measure of loneliness and pNN20 for both eyes closed (Figure 4) and eyes open conditions. There was also a significant negative correlation between HF-HRV in the eyes closed condition and the self-reported withdrawn-depressed scores. Age, socioeconomic status (SES) and physical activity were included as covariates. We examined the correlation when the dataset was separated by sex with age, SES, and physical activity as covariates. There were no significant correlations for females but males had a significant (p =<.05) correlation between closed and open pNN20 and the loneliness measure (Table 4). The pNN20 and loneliness correlation in males remained present after using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 4.

A scatterplot of self-reported loneliness questionnaire t-scores and pNN20 during eyes closed rest for males.

Table 4.

The correlation values for pNN20 and loneliness when separated by sex

| Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| closed_ pNN20 (ms): | Correlation | .437 | .097 |

| Significance | .003* | .637 | |

| df | 42 | 40 | |

| open_ pNN20 (ms): | Correlation | .452 | .037 |

| Significance | .002* | .904 | |

| df | 42 | 40 |

Note: Significance was evaluated by Pearson’s r correlations 2-tailed tests.

significant after Bonferroni correction (p = <.05)

Discussion

We hypothesized that self-reported depression/loneliness scores would be negatively associated with HRV measures in typically-developing children aged 9-14 years. The results indicate an association between pNN20 and loneliness which was driven by a strong association in boys and no association between pNN20 and loneliness in girls. However, the direction of the association is the opposite of the original hypothesis with the pNN20 showing increased HRV with increased levels of loneliness. The correlation between pNN20 and loneliness remained significant after using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction between eyes closed/open and sex for the RMSSD measure, but no association between RMSSD and symptom severity. Finally, there was no relationship between age and HRV measures indicating that the HRV measures are relatively stable across the age range assessed.

Current studies of children diagnosed with depression are consistent with adult studies demonstrating reduced HRV in individuals with a clinical diagnosis of depression relative to controls (Kemp et al. 2010). For example, Tonhajzerova et al. (2010) reported significant group differences in multiple linear and nonlinear measures of HRV in medication naïve girls aged 15-18 years with major depressive disorder (MDD) relative to age- and sex-matched controls. Monk et al. (2001) also reported that children with diagnosed anxiety disorder have reduced HRV relative to controls at baseline. Similarly, Henje-Bloom et al. (2010) identified reduced HRV in adolescent girls with MDD relative to controls. However, antidepressant medication is also known to reduce HRV (Kemp et al., 2010) and it is unclear whether changes in HRV occur prior to the onset of clinically recognizable symptoms for depression. Examining HRV in a healthy population provides additional insights into the relationship between HRV measures and depressive symptoms.

The results of this investigation differ from the findings of Blood et al. (2015) and Vasquez et al. (2016) , who demonstrated that self-reported depression symptoms in healthy children were negatively associated with HF-HRV, similar to our original hypothesis. However, other cross-sectional studies by Pine (1998), McLaughlin (2014) and Huang and Wan (2013) did not find a significant association between self-reported depression symptoms and frequency domain HRV measures in healthy children. Huang and Wan (2013) found a nonsignificant positive correlation between cognitive-affective symptoms (e.g. worthlessness and sadness) and LF and HF HRV in 333 seventh grade students from Taiwan. Pine (1998) reported a significant negative correlation between RMSSD and the internalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) in a sample of 69 7-11 year old boys. However, there was no significant correlation between HF-HRV and the depression scores from the CBCL. One challenge in interpreting the current literature is the lack of consistency in what behavioral measures were obtained for these children. Therefore, the variability in results may be related to differences in what specific symptoms were assessed with each measure. For example, Bosch et al. (2009) found that associations with cardiac autonomic function differ depending on if the depressive symptoms are somatic or cognitive-affective, and their results showed a positive association between cognitive-affective symptoms and HRV and a negative association between somatic symptoms and HRV.

These studies all obtained a resting measure of HRV and compared it to self-report measures of depression. However, the difference in results across studies may still be due to varying methodology. For example, Pine (1998) recorded 20 minutes of rest HRV in the supine position, and had lab technicians present with the children to comfort them and prevent them from sleeping. We had the children in a seated position within the MEG, typically in the late afternoon after school (2 pm – 6pm) with some children scanned in morning (10 am – 12pm). The children were alone in a quiet magnetically shielded room and were instructed to fixate on a cross during eyes open rest. Bosch (2009) took heart rate measurements in a quiet room at the children’s school and encouraged participants to be quiet and still in the supine position while recording took place. Huang (2013), Blood et al. (2015), and Vazquez et al. (2016) did not describe the environment in which the HR recording was collected. HRV can be influenced by a variety of factors such as time of day, exercise, medication, pubertal status, etc. (Fatisson, Oswald, & Lalonde, 2016). We report within subject differences when comparing eyes open to eyes closed rest indicating that subtle differences in state may impact the association between HRV measures and depression scores. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies also did not correct for multiple comparisons, which may further contribute to variations across studies. The varied results underline the importance of accounting for these factors and describing the recording environment in future studies.

For this study we used loneliness as a proxy measure for depression based on the broader body of work describing HRV changes in individuals diagnosed with clinical depression. However, two additional studies also examined HRV measures directly associated with loneliness, as loneliness is specifically related to feelings of social isolation. A similar negative association between HF-HRV and loneliness as seen in depression was described in a population of newly arrived international students (Gouin et al. 2014). However, baseline HF-HRV (within three weeks of arrival to US) was not significantly associated with loneliness or social integration, and at the 2 and 5 month follow-up the relationship with social integration (increased HF-HRV with greater integration) was stronger than the negative association with loneliness with only the 2 month time point reaching significance. The results of a more recent study may provide additional insights into this tenuous relationship between loneliness and HRV; Brown et al. (2019) reported that young adults cardiac reactivity during a stressor event was only associated with loneliness for the public speaking stressor but not during the arithmetic task stressor. They concluded that while the cardiac response system may be reactive to acute stressors, the effect was dependent on the type of stressor. It remains surprising in the current study that the pNN20 effects revealed a positive association with loneliness, yet it is important to point out that this pattern was only revealed in males and the prior studies examining loneliness did not report on sex-specific effects. The results specific to loneliness further support the need to examine age- and sex- specific effects as well as cardiac reactivity vs. resting HRV to understand whether HRV measures can be used to identify children at risk of loneliness and perhaps subsequently depression in adolescents.

HRV was initially examined in cardiac studies to assess cardiovascular health (Kemp & Quintana, 2013). Reduced HRV is associated with poorer cardiovascular health outcomes and underlines the need to include cardiovascular indicators of heart health when assessing HRV. Additionally, children with depression or depressive symptoms are less likely to be involved in extra-curricular activities due to the symptom of depression that leads to social withdrawal and as a result develop cardiovascular risk factors (Gross et al., 2018) that may influence HRV. Pain is also a common symptom that accompanies depression again leading to reduced activity (Trivedi, 2004). Therefore, most HRV studies have included a physical activity assessment to address this confound. Our study included a physical activity questionnaire which was included as a covariate in the HRV analysis similar to the results obtained by Bosch (2009), Henje Blom (2010) and Michels (2013). However, Vazquez et al. (2016) reported that the lack of a physical activity measure is a limitation for their study. Accounting for cardiac health may be an important factor in determining whether HRV can be used to identify children at risk for depression within the healthy population.

There has been little work on examining sex differences in the association between HRV measures and depression. In addition, some prior studies included samples of only boys (Mezzacappa et al., 1997; Pine et al., 1998) or only girls (Henje Blom et al., 2010), eliminating the ability to examine this factor. However, Vazquez (2016) reported significant predictive power for sex and HF HRV only (with the remaining covariates dropping out of the model) relative to depression measured 1 year later, yet there was no discussion on how this association differed between boys and girls. In light of the persistent finding of greater rates of diagnosed depression in females in children (Breslau et al., 2017) and adults (Altemus, Sarvaiya, & Neill Epperson, 2014), it seems critical to examine sex-specific indicators for depression. Our current results support this by demonstrating a sex by condition interaction for RMSSD. However, RMSSD was not correlated with depressive symptoms in boys or girls, limiting our ability to use it as a biomarker for depression even when considering differences by sex. Greaves-Lord et al. (2007) also reported differences in the association between HRV measures and depression and/or anxiety measures depending on the sex of the child. While it is difficult to interpret the significant interaction in the current study, it provides additional evidence for the importance of considering sex as an important variable when examining HRV measures as a predictor of outcomes for depression in children.

Currently, depression in children is treated when parents notice emotional or physical symptoms or based on child self-report. Parents must then schedule a visit with their doctor and, if recommended, a mental health care professional. To help with a diagnosis of depression, the child and parents answer questionnaires and provide anecdotal information. The primary challenge with this approach is the reliance on parents or an adult noticing an issue with the child or self-disclosure. If the child is effective in masking emotional difficulties or lives in an environment in which adults are neglectful of the child’s emotional health, depression may go untreated. Comparing the proportion of children who have considered suicide (17.2% of high school students, 22.1% among female students) vs. the proportion of children who are receiving treatment for depression (11% of children) demonstrates the disparity between need and those who are actively being treated (Kann et al., 2018). With no consistent results across studies, it is important for further in-depth and controlled investigation into HRV, to determine if a brief 3-5 minute HRV measurement may be used as a viable clinical indicator for risk of depression in children.

Limitations of this study are primarily related to uncontrolled factors that have been shown to influence HRV in prior studies. We did not control for time of day, though 82% of the scans were performed in the afternoon after school given the school-aged population. Pubertal status was not obtained during the visit. However, we controlled for age, socioeconomic factors, and physical activity. Both socioeconomic factors and physical activity are known to affect cardiovascular health and have been implicated in mediating HRV in other studies (Claudel et al., 2018; Elfassy et al., 2019) and were included as covariates in the current analysis. However, there remains considerable variability as to which covariates are included in studies examining HRV and depressive symptoms in children and may explain some of the variability in results discussed above. Additionally, this study looked solely at HRV during rest, which provides a baseline measure but does not allow for assessment of a change in HRV between rest and a stressor condition. Prior studies in infants have assessed differences in HRV measures between baseline and stressor conditions to address stress reactivity (Oberlander et al., 2010) instead of obtaining baseline HRV measures alone. However, as mentioned above, our approach of measuring only baseline HRV is similar to the studies which examined HRV in school-aged children. Therefore, while it may be useful to examine stress reactivity in school-aged children, this limitation does not explain the difference in results across studies of the same age range. Regardless, adding a stressor may provide a more sensitive measure of psychopathology and should be considered for future studies.

In summary, recent studies have provided some evidence that HRV measures may provide an indication of depressive symptoms in children. However, the specific HRV measure that corresponds to depressive symptoms has not been independently replicated across study sites. This may indicate that the measures are not reliable, or it may instead indicate a need for more closely controlled measures of HRV to account for other variables that also influence HRV in children including physical exercise, time of day and other cardiac health indicators. Future studies are needed to better determine the cross-site reliability of these measures in healthy children.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

The correlation values for study variables in the full sample (males and females).

| RMSSD Closed |

RMSSD Open |

HF Closed |

HF Open |

LF Closed |

LF Open |

pNN20 Closed |

pNN20 Open |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | .181 | .173 | .036 | −.014 | −.089 | −.018 | .305** | .289** |

| Sadness | −.045 | −.040 | .053 | −.032 | −.075 | .022 | .055 | .036 |

| Anxious-Depressed | −.020 | −.019 | −.001 | −.070 | .012 | .043 | .023 | .059 |

| Withdrawn-Depressed | −.065 | −.054 | .208* | −.186 | .158 | .149 | −.035 | −.054 |

= significant after Bonferroni correction(p<.05);

=uncorrected (p<.05)

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science Foundation [grant number 1539067]

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Manual for The Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrnsbrak Rebecca; Bose Jonaki; Hedden Sara L.; Lipari Rachel N.; Park-Lee Eunice. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-united-states-results-2016-national-survey. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JJ, Chambers AS, & Towers DN (2007). The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: a pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Biol Psychol, 74(2), 243–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, & Neill Epperson C (2014). Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol, 35(3), 320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Depressive Disorders Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Bizik G, Bob P, Raboch J, Pavlat J, Uhrova J, Benakova H, & Zima T (2014). Dissociative symptoms reflect levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha in patients with unipolar depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 10, 675–679. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S50197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blood JD, Wu J, Chaplin TM, Hommer R, Vazquez L, Rutherford HJ, … Crowley MJ (2015). The variable heart: High frequency and very low frequency correlates of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. J Affect Disord, 186, 119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch NM, Riese H, Dietrich A, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, & Oldehinkel AJ (2009). Preadolescents' somatic and cognitive-affective depressive symptoms are differentially related to cardiac autonomic function and cortisol: the TRAILS study. Psychosom Med, 71(9), 944–950. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bc756b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Gilman SE, Stein BD, Ruder T, Gmelin T, & Miller E (2017). Sex differences in recent first-onset depression in an epidemiological sample of adolescents. Transl Psychiatry, 7(5), e1139. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien HC, Chung YC, Yeh ML, & Lee JF (2015). Breathing exercise combined with cognitive behavioural intervention improves sleep quality and heart rate variability in major depression. J Clin Nurs, 24(21–22), 3206–3214. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudel SE, Adu-Brimpong J, Banks A, Ayers C, Albert MA, Das SR, … Powell-Wiley TM (2018). Association between neighborhood-level socioeconomic deprivation and incident hypertension: A longitudinal analysis of data from the Dallas heart study. Am Heart J, 204, 109–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford Gari D B. (2002). Signal Processing Methods for Heart Rate Variability (Doctor of Philosophy), St. Cross College, England. Retrieved from http://web.mit.edu/~gari/www/papers/GDCliffordThesis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Elfassy T, Swift SL, Glymour MM, Calonico S, Jacobs DR Jr., Mayeda ER, … Zeki Al Hazzouri A (2019). Associations of Income Volatility With Incident Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality in a US Cohort. Circulation, 139(7), 850–859. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatisson J, Oswald V, & Lalonde F (2016). Influence diagram of physiological and environmental factors affecting heart rate variability: an extended literature overview. Heart Int, 11(1), e32–e40. doi: 10.5301/heartint.5000232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon RC, Wagster MV, Hendrie HC, Fox NA, Cook KF, & Nowinski CJ (2013). NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S2–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e5f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves-Lord K, Ferdinand RF, Sondeijker FE, Dietrich A, Oldehinkel AJ, Rosmalen JG, … Verhulst FC (2007). Testing the tripartite model in young adolescents: is hyperarousal specific for anxiety and not depression? J Affect Disord, 102(1-3), 55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AC, Kaizer AM, Ryder JR, Fox CK, Rudser KD, Dengel DR, & Kelly AS (2018). Relationships of Anxiety and Depression with Cardiovascular Health in Youth with Normal Weight to Severe Obesity. J Pediatr, 199, 85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.03.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henje Blom E, Olsson EM, Serlachius E, Ericson M, & Ingvar M (2010). Heart rate variability (HRV) in adolescent females with anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. Acta Paediatr, 99(4), 604–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01657.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron M (2018). Death: Leading Causes for 2016 National Vital Statistics Report (Vol. 67). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Huang HT, & Wan KS (2013). Heart rate variability in junior high school students with depression and anxiety in Taiwan. Acta Neuropsychiatr, 25(3), 175–178. doi: 10.1111/acn.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javorka K, Lehotska Z, Kozar M, Uhrikova Z, Kolarovszki B, Javorka M, & Zibolen M (2017). Heart rate variability in newborns. Physiol Res, 66(Supplementum 2), S203–S214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, … Ethier KA (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill Summ, 67(8), 1–114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp AH, & Quintana DS (2013). The relationship between mental and physical health: insights from the study of heart rate variability. Int J Psychophysiol, 89(3), 288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Gray MA, Felmingham KL, Brown K, & Gatt JM (2010). Impact of depression and antidepressant treatment on heart rate variability: a review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry, 67(11), 1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski KC, Crocker PRE, & Kowalski NP (1997). Convergent validity of the physical activity questionnaire for adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science, 9(4), 342–352. doi: Doi 10.1123/Pes.9.4.342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski KC, Crocker PR, & Donen RM (2004). The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) and Adolescents (PAQ-A) Manual. College of Kinesiology, University of Saskatchewan, 87(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Alves S, & Sheridan MA (2014). Vagal regulation and internalizing psychopathology among adolescents exposed to childhood adversity. Dev Psychobiol, 56(5), 1036–1051. doi: 10.1002/dev.21187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzacappa E, Tremblay RE, Kindlon D, Saul JP, Arseneault L, Seguin J, … Earls F (1997). Anxiety, antisocial behavior, and heart rate regulation in adolescent males. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 38(4), 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels N, Sioen I, Clays E, De Buyzere M, Ahrens W, Huybrechts I, … De Henauw S (2013). Children's heart rate variability as stress indicator: association with reported stress and cortisol. Biol Psychol, 94(2), 433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mietus JE, Peng CK, Henry I, Goldsmith RL, & Goldberger AL (2002). The pNNx files: re-examining a widely used heart rate variability measure. Heart, 88(4), 378–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk C, Kovelenko P, Ellman LM, Sloan RP, Bagiella E, Gorman JM, & Pine DS (2001). Enhanced stress reactivity in paediatric anxiety disorders: implications for future cardiovascular health. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 4(2), 199–206. doi: 10.1017/S146114570100236X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Jacobson SW, Weinberg J, Grunau RE, Molteno CD, & Jacobson JL (2010). Prenatal alcohol exposure alters biobehavioral reactivity to pain in newborns. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 34(4), 681–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01137.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniccia M, Paniccia D, Thomas S, Taha T, & Reed N (2017). Clinical and non-clinical depression and anxiety in young people: A scoping review on heart rate variability. Auton Neurosci, 208, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Wasserman GA, Miller L, Coplan JD, Bagiella E, Kovelenku P, … Sloan RP (1998). Heart period variability and psychopathology in urban boys at risk for delinquency. Psychophysiology, 35(5), 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW (1995). Orienting in a defensive world: mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage. A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology, 32(4), 301–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psychol, 74(2), 116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salsman JM, Butt Z, Pilkonis PA, Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Hendrie HC, … Cella D (2013). Emotion assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S76–86. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, Kegler SR, Yuan K, Holland KM, … Crosby AE (2018). Vital Signs: Trends in State Suicide Rates - United States, 1999-2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide - 27 States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 67(22), 617–624. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen MP, Niskanen JP, Lipponen JA, Ranta-Aho PO, & Karjalainen PA (2014). Kubios HRV--heart rate variability analysis software. Comput Methods Programs Biomed, 113(1), 210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force. (1996). Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J, 17(3), 354–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, & Lane RD (2000). A model of neurovisceral integration in emotion regulation and dysregulation. J Affect Disord, 61(3), 201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonhajzerova I, Ondrejka I, Javorka K, Turianikova Z, Farsky I, & Javorka M (2010). Cardiac autonomic regulation is impaired in girls with major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 34(4), 613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonhajzerova I, Ondrejka I, Javorka M, Adamik P, Turianikova Z, Kerna V, … Calkovska A (2009). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia is reduced in adolescent major depressive disorder. Eur J Med Res, 14 Suppl 4, 280–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH (2004). The link between depression and physical symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 6(Suppl 1), 12–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez L, Blood JD, Wu J, Chaplin TM, Hommer RE, Rutherford HJ, … Crowley MJ (2016). High frequency heart-rate variability predicts adolescent depressive symptoms, particularly anhedonia, across one year. J Affect Disord, 196, 243–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xhyheri B, Manfrini O, Mazzolini M, Pizzi C, & Bugiardini R (2012). Heart rate variability today. Prog Cardiovasc Dis, 55(3), 321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.