Dear Editor,

Survivors of COVID-19-associated pneumonia may experience a long-term reduction in functional capacity, exercise tolerance, and muscle strength, regardless of their previous health status or disabilities.1, 2, 3 Telerehabilitation (TR) programs have proven effective in several conditions,4, 5, 6 and have been also suggested for patients after COVID-19.7 To date, however, no study has investigated whether early telerehabilitation after hospitalization for COVID-19-associated pneumonia is effective. We report a pilot study investigating the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of a 1-month TR program in individuals discharged after recovery from COVID-19 pneumonia [Ethical Committee approval 2440CE].

The study was conducted from April 1 to June 30, 2020 at the ICS Maugeri Institute of Lumezzane, Italy, a referral centre for pulmonary rehabilitation with a dedicated COVID-19 Unit. Inclusion criteria were: clinical stability; resting hypoxaemia or exercise-induced desaturation (EID) [≥4% decrease in SpO2 at the 6-min Walking Test (6MWT)8], or exercise limitation (6MWT: <70% of predicted), availability of home internet and ability to use technologies. Patients with cognitive deficits, severe comorbidities or physical impairment preventing exercise without medical supervision were excluded.

On admission to the program, patients received a pulse oximeter, a brochure illustrating exercises, a diary to record daily activities, and instructions for home exercises. The one-month program consisted of one hour daily of aerobic reconditioning and muscle strengthening and healthy lifestyle education. Twice a week, a physiotherapist (PT) contacted the patient—by video-call via a dedicated platform—to monitor progress. Exercise intensity was based on the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)9 test and EID and was divided into 4 arbitrary levels (1 = lowest intensity, 4 = highest intensity). Patients with SPPB < 10 or EID were included in the levels 1–2 and performed low-intensity aerobics (walking, free-body exercise, sit-to-stand) and balance exercises. Patients with SPPB ≥ 10 and no EID were included in the levels 3–4 and performed walking session with pedometer, aerobics with cycle ergometer or leg/arm crank, and strengthening exercises with a lightweight band. The intensity of the exercise session was progressively increased according to symptoms and cardio-respiratory parameters evaluation. Programs could be changed only under strict PT control. Chest physiotherapy exercises (lung expansion, strengthening of the respiratory muscles) could be added, if necessary. In addition to physiotherapy monitoring, for the first two weeks nurses tele-monitored patients daily to check their clinical needs; subsequently, patients received one weekly telephone/video call. If any symptoms/problems emerged, patients could always contact nurses (7/7 days) or physicians for a second-opinion consultation.

On admission to TR, anthropometrics, clinical status and lung function were collected ( Table 1 ). On admission and discharge, 6MWT,8 1 min Sit-to-Stand (1MSTS),10 and Barthel Dyspnoea Index11 were assessed. Program adherence (i.e. number of performed/scheduled video-calls) was assessed. “Pre” to “post” program differences were analyzed by paired t- or Pearson Chi-square test. The percentage of patients reaching the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the measures was evaluated. Pearson correlation analysis assessed the change in outcome measures (observed in video calls) from baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, physiological and clinical characteristics of patients at the start of the TR program. Data as mean ± SD or number (%).

| Characteristics | Measure |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 11 (45.8) |

| Age, years | 66.0 ± 8.7 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.1 ± 5.6 |

| SpO2, % | 95.4 ± 2.3 |

| FiO2, % | 23.5 ± 4.3 |

| Oxygen therapy at rest, n (%) | 6 (20.8) |

| CIRS1, score | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| SPPB, score | 7.1 ± 4.3 |

| FEV1, % pred. | 84.6 ± 19.0 |

| FVC, % pred. | 77.9 ± 18.3 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 89.9 ± 13.1 |

| MIP, cmH2O | 76.1 ± 28.8 |

| MIP, % pred. | 82.2 ± 22.9 |

| MEP, cmH2O | 86.7 ± 31.7 |

| MEP, % pred. | 49.2 ± 13.7 |

| Clinical History, n (%) | |

| Invasive Mechanical Ventilation | 12 (50.0) |

| CPAP | 17 (70.8) |

| Tracheostomy | 7 (29.2) |

| Oxygen Therapy | 24 (100.0) |

| 6MWT, meters | 298.4 ± 111.7 |

| 6MWT, % predicted | 55.1 ± 21.6 |

| 1MSTS, number of sit-to-stand rises | 18.0 ± 8.1 |

| 1MSTS, % predicted | 52.6 ± 26.4 |

| Barthel dyspnoea, score | 11.7 ± 9.0 |

CIRS1 = Cumulative Illness Rating Scale 1, BMI = Body-Mass Index, SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery, SpO2 = pulse oxymetry, FiO2 = Inspired Oxygen Fraction, FEV1 = Forced Expiratory Volume at first second, FVC = Forced Vital Capacity, MIP = Maximal Inspiratory Pressure, MEP = Maximal Expiratory Pressure, CPAP = Continuous Positive Airways Pressure, 6MWT = 6-Min Walk Test, 1MSTS = 1 min Sit-to-Stand.

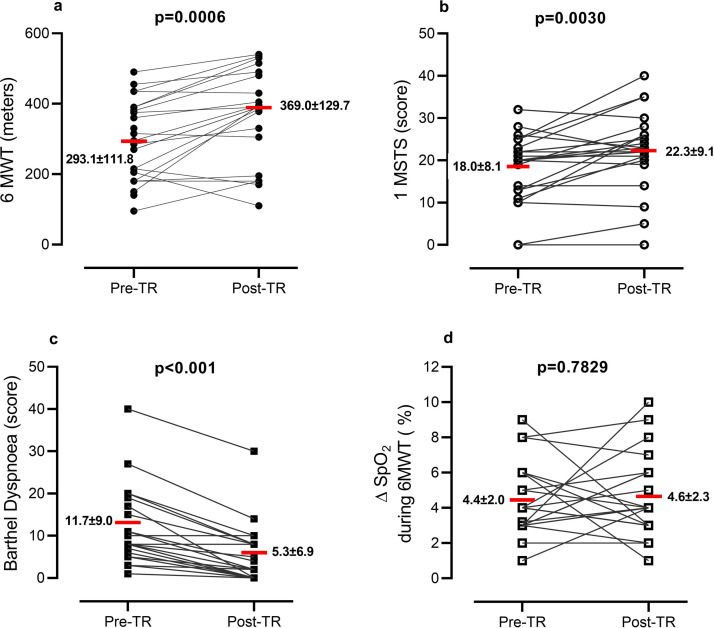

Out of 25 consecutive patients, 24 completed the program. Patients attended 7.2 ± 1.7 out of 8 video-calls scheduled and nurses made 13.4 ± 2.1 phone calls. Patients reported fatigue (70.8%), muscle pain (50.0%), exercise induced dyspnoea (50.0%), and sleep disorders (41.7%). No need for hospitalization or emergency room visits occurred. TR allowed patients to change their exercise capacity passing from an initial intensity level of 1.2 ± 2.1 to a final level of 3.1 ± 1.3. No adverse effect was reported. Fig. 1 shows the changes in outcome measures. Exercise capacity and Barthel dyspnoea significantly improved. The percentage of patients with EID at 6MWT was 62.5% at admission and 66.7% at discharge (P = 0.6624), while at 1MSTS it was 50.0% at admission and 41.6% at discharge (P = 0.6735).

Figure 1.

Individual changes in outcome measures between admission (pre-TR) and discharge from (post-TR) the program. Red bar represents the mean data.

Legend: 6MWT = 6 min Walking Distance; 1MSTS = 1 min Sit-to-Stand.

At the end of the program, distance walked in 6MWT increased in 75.0% of patients, remained stable in 4.2%, and decreased in 20.8% of patients; 17 patients (70.8%) improved 6MWT above the MCID (30 m).8

The number of sit-to-stands increased in 62.5%, remained stable in 16.6%, and decreased in 20.8% of patients; 12 patients (50.0%) improved 1MSTS above the MCID (3 rises).10 Barthel dyspnoea improved in 83.3%, remaining unchanged in 16.7% of patients; in 50% of patients, the dyspnoea decrease was 6.5 points above the MCID.11

This preliminary report, although limited by the small sample size and absence of a control group, confirms the feasibility and safety of a dedicated TR program for survivors of COVID-19 pneumonia. After one month of TR, patients improved exercise tolerance and dyspnoea. However, approximately 20% of patients were non-responders. No adverse events were found. As with chronic cardio-pulmonary diseases, telerehabilitation may help to avoid a gap in service delivery following hospital discharge of COVID-19 patients and should be integrated into their follow-up. Further randomized control trials are needed.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Ricerca Corrente” Funding scheme of the Ministry of Health, Italy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Paneroni M., Simonelli C., Saleri M., Bertacchini L., Venturelli M., Troosters T., et al. Muscle strength and physical performance in patients without previous disabilities recovering from COVID-19 Pneumonia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;100(2):105–109. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zampogna E., Paneroni M., Belli S., Aliani M., Gandolfo A., Visca D., et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation in patients recovering from COVID-19. Respiration. 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000514387. Online ahead of print. Mar 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambrosino N., Vitacca M., Dreher M., Isetta V., Montserrat J.M., Tonia T., et al. Tele-monitoring of ventilator-dependent patients: a European Respiratory Society Statement. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):648–663. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01721-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelucci A., Aliverti A. Telemonitoring systems for respiratory patients: technological aspects. Pulmonology. 2020;26(4):221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scalvini S., Bernocchi P., Zanelli E., Comini L., Vitacca M., Maugeri Centre for Telehealth and Telecare (MCTT) Maugeri centre for telehealth and telecare: a real-life integrated experience in chronic patients. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):500–507. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17710827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox N.S., Scrivener K., Holland A.E., Jolliffe L., Wighton A., Nelson S., et al. A brief intervention to support implementation of telerehabilitation by community rehabilitation services during COVID-19: a feasibility study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.12.007. S0003-9993(20)31380-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puente-Maestu L., Palange P., Casaburi R., Laveneziana P., Maltais F., Neder J.A., et al. Use of exercise testing in the evaluation of interventional efficacy: an official ERS statement. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):429–460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00745-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guralnik J.M., Simonsick E.M., Ferrucci L. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook S., Büsching G., Schultz K., Lehbert N., Jelusic D., Keusch S., et al. A multicentre validation of the 1-min sit-to-stand test in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1601871. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01871-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vitacca M., Malovini A., Balbi B., Aliani M., Cirio S., Spanevello A., et al. Minimal Clinically important difference in Barthel index dyspnea in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2020;15:2591–2599. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S266243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]