Abstract

Explants are three-dimensional tissue fragments maintained outside the organism. The goals of this article are to review the history of fish explant culture and discuss applications of this technique that may assist the modern zebrafish laboratory. Because most zebrafish workers do not have a background in tissue culture, the key variables of this method are deliberately explained in a general way. This is followed by a review of fish-specific explantation approaches, including presurgical husbandry, aseptic dissection technique, choice of media and additives, incubation conditions, viability assays, and imaging studies. Relevant articles since 1970 are organized in a table grouped by organ system. From these, I highlight several recent studies using explant culture to study physiological and embryological processes in teleosts, including circadian rhythms, hormonal regulation, and cardiac development.

Keywords: cell culture, explant, media, organ culture, organoid, slice culture, tissue culture

Introduction

The aims of this article are to review the history of fish explant culture and to discuss techniques that will assist current researchers. Assuming little or no prior knowledge of in vitro work, the text is designed to aid the investigator just starting such a project. After this review, the reader should be better equipped to grasp the existing literature on the subject and will have the advantage of the references herein. I begin with the first documented studies on fish cells in vitro, and conclude with several recent articles using explant approaches to investigate fish biology—a span of approximately 50 years. In between, I attempt to answer the following questions: What are explants, and how are they useful? What culture methods are available and how successful are they? Finally, what types of experiments can be conducted on explants, and what is the best way to carry out and report such experiments?

Although the detailed facets of in vitro culture may first seem laborious, several fish-specific factors simplify this approach. Medium formulas are available that are pH balanced in air, meaning that no carbon dioxide (CO2) incubators or gas canisters are required. Warm-water fish tissues can be incubated on the bench, and cold-water fish tissues in a refrigerator. These lower incubation temperatures minimize bacterial growth and decrease the frequency of medium changes. Finally, the risk of zoonotic transfer from fish cells to researchers is low. Taken together, these factors make the culture of fish tissues convenient and safe for any laboratory, maximizing opportunities for both in vivo and in vitro work.

Explants: definitions, advantages, and imperfections

In the literature, “explant culture” and “organ culture” are used nearly interchangeably. The term “explant” is used in this review to refer to the native piece of tissue removed from the animal (Fig. 1). Historically, explant culture has had one of two goals: to establish a cell line from the explant or to maintain the explant as a representative subsection of a living organ. The advantages of explants are well stated by previous workers. Appropriate culture conditions “permit the in vitro maintenance of whole organs or fragments in a viable, organized, and differentiated condition.”1 Given adequate support, these cells can maintain a broad spectrum of biochemical signaling with their natural neighbors. At the same time that explant culture preserves the local junctions or “neighborhood” of the cell, it removes higher-tier connections such as neural, hormonal, or metabolic influences, enabling “part of a complicated problem to be isolated from the general confusion of the body.”2 As such, explants are a powerful test of tissue autonomy. For example, Anderson et al. isolated spleen and head kidney from rainbow trout and immunized individual explants by injecting bacterial toxins.3 They demonstrated that each organ was competent to produce its own antibodies, independent of any other stimuli. Similarly, Tyler et al. showed that isolated, washed, and denuded trout ovarian follicles in vitro could sequester the major yolk protein vitellogenin (VTG) from a chemically defined medium at rates similar to in vivo follicles,4 making it likely that VTG uptake is solely oocyte controlled. Finally, the entire system of in vitro culture provides excellent experimental accessibility and physical control, which explains its perennial place in the scientific record.

FIG. 1.

Pathways from in vivo to in vitro. Starting with a fish, a tissue explant or slice is prepared. Historically, the purpose of the explant was to outgrow primary cells. Surviving cells were then passaged repeatedly, establishing permanent or “immortal” cell lines. Although convenient to manipulate, immortal cells may differ phenotypically and genetically from in vivo or primary cells, and represent only a fraction of the explant from which they were derived. 3D, three dimensional.

Why, then, are explant cultures not more used? An obvious reason is that the dominant laboratory species, the zebrafish, is so useful for studies in vivo. A related concern is that culture conditions are artificial and imperfect, leading to what some consider less-than-useful data. Finally, investigators might perceive that the necessary procedures are time-consuming and costly additions to existing laboratory routines.

In vivo versus in vitro

Only a small part of the zebrafish life cycle is small, transparent, and accessible. This stage is developmentally immature and does not have fully functional immune, endocrine, or reproductive systems. In contrast, explant culture is frequently applied to juveniles or adults of larger commercial species such as cod, salmon, trout, and tilapia, and investigators working with these fishes have pioneered many organ-specific techniques that might be more widely used (Table 1). Therefore explants can effectively expand the developmental range that can be studied and provide additional insights into the function of mature or senescent tissues.

Table 1.

Selected Explant Culture Articles (1970–Present) Using Teleost Tissues

| Cartilage and bones | |

| Langille (1988)122 | Medaka |

| Duan (1990)123 | Eel |

| Miyake (1994)79 | Zebrafish, medaka |

| Ng (2001)124 | Tilapia |

| Central nervous system | |

| Pituitary | |

| Sage (1968)125 | Swordtail |

| Sage (1968)126 | Swordtail |

| Baker (1975)127 | Salmon, eel |

| Yada (1995)128 | Trout |

| Kakizawa-Kubiak (1997)129 | Trout |

| Kalamarz (2011)130 | Stickleback, goby |

| Bloch (2014)118 | Tilapia |

| Pineal | |

| Gern (1988)131 | Trout |

| Kezuka (1989)132 | Goldfish |

| Iigo (1991)133 | Goldfish |

| Thibault (1993)134 | Trout |

| Bolliet (1994)62 | Pike |

| Yanez (1996)135 | Trout |

| Cahill (1997)136 | Zebrafish |

| Iigo (1998)137 | Salmon |

| Takemura (2006)138 | Rabbitfish |

| Embryo | |

| Laale (1981)139 | Zebrafish |

| Laale (1984)140 | Zebrafish |

| Bingham (2005)141 | Zebrafish |

| Fins | |

| Uwa (1987)52 | Medaka |

| Cardona-Costa (2006)142 | Zebrafish |

| Gills | |

| McCormick (1989)143 | Salmon |

| Stadtländer (1990)1 | Salmon |

| Shrimpton (1999)144 | Trout |

| Bury (1998)145 | Tilapia |

| Holland (1998)146 | Trout |

| Nematollahi (2003)147 | Trout |

| Mazon (2004)148 | Trout |

| Kiilerich (2007)149 | Salmon |

| Lazado (2020)35 | Salmon |

| Gonads | |

| Ovary | |

| Tyler (1990)4 | Trout |

| Pankhurst (2000)150 | Flounder |

| Todo (2008)151 | Wrasse |

| Ogiwara (2010)152 | Medaka |

| Tsai (2010)153 | Zebrafish |

| Wang (2020)154 | Sterlet |

| Testis | |

| Bonnin (1975)155 | Goby |

| Miura (1991)156 | Eel |

| Amer (2001)157 | Huchen |

| Bouma (2003)158 | Trout |

| Bouma (2005)159 | Trout |

| Iwasaki (2009)160 | Medaka |

| Leal (2009)33 | Zebrafish |

| Skaar (2011)161 | Zebrafish |

| Kang (2019)162 | Medaka |

| Ovary and testis | |

| de Clercq (1977)163 | Goldfish |

| Sakai (2008)164 | Tilapia |

| Beitel (2014)165 | Pike, sucker, walleye |

| Gut | |

| Sundell, (1988)166 | Cod |

| Ringo (2004)167 | Salmon |

| Jirillo (2007)168 | Trout |

| Barato (2016)169 | Tilapia |

| Vasquez-Machado (2019)170 | Tilapia |

| Coccia (2019)171 | Trout |

| Heart | |

| Kitambi (2012)172 | Zebrafish |

| Pieperhoff (2014)121 | Zebrafish |

| Yue (2015)119 | Zebrafish |

| Cao (2016)120 | Zebrafish |

| Rastgar (2019)173 | Grass carp |

| Yip (2020)96 | Zebrafish |

| Kidney | |

| Trump (1977)174 | Flounder |

| de Ruiter (1981)175 | Stickleback |

| Jones (1982)87 | ? |

| Anderson (1986)3 | Trout |

| Lens | |

| Uga (1986)176 | Trout |

| Laycock (2000)177 | Trout |

| Bantseev (2004)178 | 9 Species |

| van Doorn (2005)179 | Trout |

| Schartau (2010)116 | Blue acara |

| Liver | |

| Santos (2000)180 | Eel |

| Schmieder (2000)34 | Trout |

| Oliveira (2003)181 | Eel |

| Yu (2008)182 | Grouper |

| Nichols (2009)183 | Trout |

| Gerbron (2010)36 | Roach |

| Lemaire (2011)184 | Salmon |

| Eide (2014)185 | Cod |

| Beitel (2015)186 | 4 Species |

| Doering (2015)187 | Sturgeon |

| Harvey (2019)188 | Salmon |

| Muscle | |

| Negatu (1995)38 | Killifish |

| Funkenstein (2006)189 | Bream |

| Lazado (2014)117 | Cod |

| Retina | |

| Landreth (1976)40 | Goldfish |

| Johns (1978)190 | Hogchoker, catfish |

| Murakami (1982)191 | Carp |

| Murakami (1987)192 | Carp |

| Takahashi (1992)55 | Goldfish |

| Mack (1993)193 | Goldfish |

| Boucher (1998)78 | Goldfish |

| Pancreas | |

| Tilzey (1985)194 | Trout |

| Scales | |

| Zylberberg (1988)195 | Goldfish |

| Koumans (1996)88 | Cichlid |

| Pasqualetti (2012)196 | Zebrafish |

| Skin | |

| Eriksson (1985)197 | Killifish |

| McCormick (1990)198 | Tilapia |

| Marshall, (1992)199 | Trout |

| Lamche (2000)16 | Trout |

| Uchida-Oka (2001)200 | Medaka |

| Spleen | |

| Anderson (1986)3 | Trout |

| Tooth | |

| Van der Heyden (2005)201 | Cichlid, zebrafish |

| Thyroid | |

| Bonnin (1971)202 | Goby |

| Grau (1986)203 | Parrotfish |

| Swanson (1988)204 | Parrotfish |

Entries are grouped by organ system, then chronologically. Only first authors' names are listed.

Ex vivo = artificial

All experiments introduce artificiality. Laboratory animals are not in the same environment as wild animals and have different genetics, diet, stresses, and pathogen exposure. This artificiality does not prevent us from maintaining colonies of fish or mice and attempting to use them to model human disease. Likewise, all cells respond to ex vivo conditions by changing gene expression or behavior. As this is unavoidable, it must be handled the same way as any other scientific pursuit, using appropriate internal controls and in vivo benchmarks.

Time and cost

It has been known for the last 50 years that keeping fish cells in culture is in fact “rather simple, largely due to the ability of poikilothermic tissue to grow at room temperature in an air-equilibrated nutrient medium and in the presence of an effective antibiotic.”5 The unique properties of fish cells in comparison to their mammalian counterparts will be explained below. Overall, these features allow any motivated fish worker to pilot explant culture rapidly, without great trouble or expense.

In summary, a naive view of scientific progress would assume that all in vitro work is secondary to in vivo approaches. However, a fresh look at explant culture is now advisable. Explant culture conditions are already well established for various kinds of fish organs, and the scope and sophistication of these endeavors continue to grow. In vitro culture is also the foundation for mammalian stem cell and regenerative medicine, using patient-derived, reprogrammed pluripotent stem cells to create “organoids” or “organs on a chip” (review by Al-Lamki et al.6). These assemblies, it is hoped, might pave the way for re-implantation into human hosts, restoring the functions of older or damaged organs.

Scope and limits of review

As the title states, the review period is the last half century (1970–2020). After a brief history of fish cell lines, the article emphasis is on explant culture, meaning blocks or slices of organs rather than outgrowths from them. No attempt has been made to cite every article. Rather, the bibliography is curated to highlight both variety of approaches and the earliest or “foundation” articles of each organ system. This leaves out articles that re-use prior methods or build on them only marginally. The most important criterion is clear and complete documentation of the critical variables of in vitro technique. As a guide to future investigators, recommendations for good reporting are summarized in Table 2, “Minimum Description of Explant Culture Experiments.”

Table 2.

Minimum Description of Explant Culture Experiments, with Suggested Language by Section

| Number of fish used |

| “Six fish were used for these experiments. The explants were prepared such that tissue from each fish was evenly distributed in each of the treatments.” |

| Dissection, washing, and anti-infection technique |

| “Adult fish were anesthetized in 0.01% tricaine (MS-222) and placed on a sterile drape in a tissue culture hood. A small area was rubbed with dilute iodine and then individual scales were removed with flame-sterilized forceps.” |

| Contents, geometry, and dimensions of explants |

| “Skin was reduced to small rectangular pieces (1 × 1 × 2 mm) freed of muscle and fat.” |

| “The isolated pancreatic lobes were roughly spherical with an approximate radius of 500 microns.” |

| “Each vibratome brain slice was 300 um thick.” |

| Format and volume of culture vessel |

| “Explant culture was performed in a 96-well microplate with 100 uL of medium per well and gentle agitation at 50 rpm.” |

| Composition of culture media |

| “Medium was Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (Gibco #999) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin.” |

| “Tissues were cultured in 0.83x L-15 (Sigma Chemical #999) with 25 mM HEPES, 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 50 ug/mL kanamycin.” |

| Incubation conditions, including pH, osmolarity, temperature, and gas environment |

| “Culture was for 24, 48, or 72 hours at 28°C under 95% O2: 5% CO2 in a humidified, water-jacketed incubator.” |

| “Cultures were incubated on the bench for 3 days in normal air. Temperature, pH, and osmolarity were measured daily and stayed within +/-5% of target values (temperature = 22°C, pH = 7.8, and osmolarity = 305 mOsm).” |

| Schedule and volume of medium changes |

| “Twenty four hours after plating, the cultures were cleared of cellular debris and 50% (1 mL) of the medium exchanged. Explants were cultured an additional 48 hours without medium changes and then harvested for analysis.” |

| “Cultures were monitored daily and 30% (500 uL) of the medium was replaced three times per week.” |

| Number of explants attempted, and number analyzed vs. discarded |

| “In this study, we established 27 independent explants in vitro. Two of these were discarded for contamination, and 1 for nonviability. The remaining 24 were processed at the endpoint as described.” |

| Assessment of cell morphology and viability |

| “The following three assays were used to evaluate the effects of long-term culture under various conditions: Trypan Blue exclusion, LDH cytotoxicity assay, and H&E staining of paraffin sections. Each of these assays is now described.” |

| “Three criteria were set to ensure the quality and reproducibility of results: X, Y, and Z. If any of these criteria was not met for a particular explant, the data were discarded.” |

History of fish cells in vitro

At about the same time that the zebrafish was launched as a model organism for in vivo studies of vertebrate development (reviews by Grunwald and Eisen7 and Meunier8), the first fish cell lines were established in vitro.9,10 The reason was viral infections of farmed juvenile trout.11 To find the pathogen and its biological niche, aquarists isolated the organs of infected fish and grew out cell layers. This led to the discovery of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), which remains one of the most dangerous pathogens of fishes worldwide.12

In the following decades, the culture techniques developed for necrosis virus isolation remained valuable and allowed new questions. What were the biological properties of cultured fish cells? What were their physiologic responses to changing conditions? Building on the in vitro approach, it became possible to study the effects of chemical carcinogens, heat shock, or ionizing radiation. For these investigations, many workers chose easily accessible tissues such as the gills,13 fins,14,15 skin,16,17 and scales,18 all of which form rapid outgrowths of primary cells. Excellent summaries of fish-derived cell lines are available.9,11,18–22 Bols and Lee is particularly recommended because the references are organized by tissue type such as kidney, gonads, peripheral blood, and other sources.21

Tools and techniques of explant culture

As noted above, explants preserve a fragment of three-dimensional organ architecture seen in vivo, while also allowing improved access and experimental control. The challenge for the culturist, then, is to maintain the organization and function of the explant as faithfully as possible for the duration of the experiment. The tools and techniques of explant culture overlap with those of cell culture and have been developed in parallel. Therefore, it is valuable to access key textbooks and manuals of cell culture,23 as well as individual review articles on cell culture24–29 and explant culture methods.30,31 In the following sections, I describe a general workflow for explant culture from fish tissue, including presurgical husbandry, aseptic dissection technique, media and additives, and incubation conditions. Experimental details are within the articles cited. In this article, Box 1 provides a protocol and medium recipes that may be a convenient starting point for the explant-interested zebrafish laboratory.

Box 1. A Serum-Free, Air-Equilibrated, Fish-Friendly Culture Medium

This recipe derives from Koumans and Sire, who tested combinations of L-15, with numerous additives, on the regeneration of adult fish scales in vitro.88 Their preferred formula was called “L-15 prep” (pH ∼7.4). It was L-15 + glutamine with 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (for pH control), 1× Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) amino acids (contains proline, which L-15 supposedly lacks), and 10–100 nM dexamethasone (a synthetic glucocorticoid, with anti-inflammatory properties). They also used low bicarb—1 mM NaHCO3 (not for buffering, but as an “essential element”)—and 150 μg/mL ascorbic acid (for collagen synthesis). The L-15 that follows is further modified by being used at 0.88× , not 1× , which is estimated to be about ∼295 mOsmol, close to plasma osmolarity for zebrafish.

Reagents (All from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted)

| • L-15 powder, w/glutamine | L4386 | store bottle at 4°C |

| • HEPES 1 M solution (pH 7.4–7.8) | H0887-20ML | aliquot and freeze at −20°C |

| • Penicillin/streptomycin solution, 1000 × | P4333-100ML | aliquot and freeze at −20°C |

| • RPMI amino acid solution, 50 × | R7131-100ML | aliquot and freeze at −20°C |

| • Dexamethasone | D4902-25MG | resuspend in 100% EtOH, store at 4°C |

| • L-ascorbic acid, cell culture grade | A4544-100G | store stock at 4°C |

Working Solutions

1× L-15 is 13.8 g of powder per liter of water (this is printed on the bottle). 0.88× L-15 is therefore 12.1 g/L. To make 100 mL of 0.88× L-15, mix the following:

0.88× L-15 washing solution (100 mL)

Put 1.21 g of L-15 powder in a clean beaker, add 90 mL water, and stir to dissolve.

Add antimicrobials as desired:

○ 500 μL 1000× pen-strep (final concentration is 50 U penicillin and 0.050 mg streptomycin/mL)

Stir well and pH to 0.2 U above desired level (7.6).

Add H2O up to final volume (100 mL).

Filter-sterilize into a sterile container through a 0.2 μM filter. pH will drop slightly and the solution color should be orange-red. Store sterile media at 4°C for 1–2 weeks, discarding if it changes color or turns cloudy.

0.88× L-15 incubation solution (100 mL)

Put 1.21 g of L-15 powder in a clean beaker, add 90 mL water and stir to dissolve.

Add the desired media additives:

○ 2 mL 50× RPMI amino acids (final concentration is 1×)

○ 100 μL 1000× pen-strep (final concentration is 10 U penicillin and 0.010 mg streptomycin/mL)

○ 1 mL 1 M HEPES (stock is 1000 mM, final concentration is 10 mM)

○ 4 μL dexamethasone (stock = 1 mg/mL = 2.55 mM; final concentration is 100 nM)

Stir well, adjust pH, filter, and store as above.

Stock Solutions

Dexamethasone (25,000 × )

Measure 10 mg of powder (0.010 g).

Add 10 mL 100% EtOH to make a 1 mg/mL stock ( = 2.25 nM).

Store at 4°C in 500 μL aliquots.

To use, dilute 1:25,000 (yes, this is very dilute). If you put 2 μL in 50 mL of media you get a final concentration of 100 nM. Working concentration is 10–100 nM.

Ascorbic acid (1000 × )

Put 1 g in 17.3 mL of H2O to yield a 200 mM stock solution.

Filter-sterilize and aliquot into sterile tubes.

Store at −20°C in the dark for up to 6 months.

Adding 100 μL of stock to 100 mL of media makes a 200 mM final concentration.

Tissue Preparation

Danio rerio reared to 2–3 days were killed by overdose of MS-222 in egg water.

Embryos were decapitated at the head just anterior to the yolk (see Fig. 1B; Van der Heyden et al.201).

Control tissue is fixed immediately, to mark condition at the time of dissection.

Tissue for in vitro work is washed two times for 3 min each in Washing Solution.

Explants are transferred to 24-well culture plates with 500 μL Incubation Solution.

Incubation Conditions

Incubate at 25°C–27°C in a humidified air incubator.

Change 50% of medium every 2–3 days.

Rinse in 1 × Ringer's saline to remove L-15.

Fix as desired for downstream application.

Fish husbandry, water quality, surgical preparation, and dissection technique

Reducing contamination begins with fish husbandry practices planned days or weeks before the experiment. These include limiting food, transferring to sterile water with or without antimicrobials, disinfecting animals and explants, and maintaining a clean surgical area.

The most likely contaminants of fish explant culture are the gut and skin microbiota and, by extension, the aquarium water that bathes them. To reduce the gut load, isolate experimental fish and reduce or withhold food for one to several days before tissue extraction. To reduce the skin load, transfer experimental fish to a new tank of well-aerated, autoclaved system water for several hours. Strong circulation in this tank will thin the animals' external mucous layer and dilute any microbes released. Fish in this treatment should never be crowded, as the microbial dilution will be proportional to the volume of water used. At this point, you could also add some broad-spectrum antimicrobials.

Once euthanized, fish can be rinsed again in sterile system water, and then immersed in or wiped with a surface decontaminant. For this step, researchers have used dilutions of ethanol, iodine, hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite, or potassium permanganate, among others.32 A spray bottle of hydrogen peroxide from the local pharmacy is a cheap and convenient option. Dissect the fish in a precleaned surgical area such as a ultraviolet-sterilized containment hood, an autoclaved dissecting pan, or a clean bench covered with a sterile drape. Autoclaved or flame-sterilized instruments are advisable. Finally, when dissecting in the abdominal cavity, avoid puncturing the gut unless these tissues are the goal. After the desired tissue is obtained, some researchers take the additional step of dunking the dissected explant into diluted ethanol, bleach, or other decontaminant, followed by rinsing.33

A capillary network provides a natural set of channels for diffusion through an explant. However, when packed with clotted fibrin or damaged erythrocytes, this effect is lost. Removing blood before culture may increase explant permeability and eliminate potential toxins. If the animal is large, the entire body can be perfused with sterile saline, with or without heparin, before dissection.34 Postdissection, isolated organs can be perfused before cutting and culturing further, as described for the gill35 or the liver.36 Alternatively, individual explants can be “preincubated” in sterile media, with agitation, for several hours.37 This short bath removes blood products, after which the explant is transferred to a fresh culture vessel.

Explant size

When explanting from a larger organ, tissue blocks or strips are typically quite small, perhaps 1–2 mm in largest dimension. Most are cut manually, although multiple groups report using mechanical tissue choppers.34,38–40 These instruments can produce finely-calibrated slices of several hundred microns (review by Parrish et al.41). By rotating the tissue 90° between such slices, Landreth and Agranoff40 produced precise 500-micron squares of goldfish retina that were then laid on collagen-coated culture dishes. Compared to manual dissection, this approach produced more consistent fragments faster and with less cellular damage.

Some tissues may be more appropriate for explantation than others. For example, epidermis, cartilage, and retina are naturally avascular. Having no endogenous blood vessels, they get their nutrients and gases by diffusion from capillaries elsewhere and so may live in a culture dish more happily. Even then, cells at the center of the explant may over time be less healthy or less active than those at the margins as judged by morphology, mitotic activity, RNA synthesis, or other indicators. These size limitations can be overcome if the tissue selected is highly permeable (gill filaments), thin in one dimension (scales), or has naturally occurring fluid-filled channels (gut tubes or heart chambers). In the absence of such features, frequent medium changes or constant, gentle agitation may improve explant viability and lifespan.

Nutrient or growth media

Once you have selected the species, organ, and explant size, the most perplexing decision is selecting a culture medium. Many are available, but which to choose is rarely explained. Thus, it is said that tissue culture has “at least some characteristics of a cult, and as such, some of the rituals are never questioned, but copied from one generation to the next.”9 When asked “Why did you choose medium X?,” the responses “My advisor told me to” or “I read it in this paper” are cultish and ritual answers. A scientific answer will include a reasoned choice of several key variables. In this section, I will cover the choice of culture media for explants of fish tissue, discussing the major variables of gas concentration, acid/base balance, and osmolarity.

Gases, acids, and bases: the ectotherm/endotherm divide

To understand the requirements of fish cells in culture, a review of water-breathing ectotherms versus air-breathing endotherms is in order. This distinction is important because there is a massive and inalterable difference in the concentrations of two key physiologic gases—CO2 and O2—in these animals' tissues. The principles reviewed in this article are discussed at greater length and lucidity by Dejours, a copy of whose work should sit on every aquarist's bookshelf.42,43

The air you inhale carries low CO2, ∼0.04%. However, the air in a CO2 incubator delivers this gas at a concentration 100 times higher (∼5%). So if mammals inhale low CO2, why do we offer their cells high CO2? The answer is that the high CO2 pumped in from the gas cylinder mimics the blood gases within endothermic vertebrates. Because endotherms consume so much oxygen per gram, their cells produce substantial quantities of tissue CO2. This gas leaves the cells and enters the blood. Therefore, high blood CO2 is caused by high tissue CO2, which is caused by high oxygen consumption. And this is the gas status of the endothermic air-breather, which is why the CO2 in the cell culture incubator is high.

High CO2 presents a problem. This gas when dissolved becomes carbonic acid, lowering pH (for chemistry, see Box 2). To counteract the acid produced, endothermic vertebrates have evolved a robust bicarbonate-based blood-buffering system. Specifically, each molecule of bicarbonate (NaHCO3) dissociates into one sodium cation (Na+) and one hydrogen carbonate anion (HCO3−). The latter is alkaline, counteracting the acidity of CO2 in water. For this same reason, mammalian culture media often contain abundant bicarbonate, although this chemical alone is not ideal. This is because the pKa of NaHCO3 is ∼6.1, which means that a purely bicarbonate-buffering system sits below the preferred physiological range of most cells (e.g., pH 7.3–7.4). Therefore, in vitro, other buffering agents with a different pKa have been used.44 And this is the acid/base status of the endothermic cell in vivo, and also in the CO2 incubator.

Box 2. Bicarbonate Buffer Chemistry

Equation 1. What happens to carbon dioxide in water?

| 1 |

Translation left to right: “Carbon dioxide in water makes carbonic acid, which adds H+, lowering pH.”

Translation right to left: “Adding bicarbonate captures H+, raising pH.”

Equation 2. What determines blood pH?

| 2 |

where

[HCO3−] = the concentration of bicarbonate ion in the blood, in mmol/L

pCO2 = the partial pressure of carbon dioxide, in mmHg

0.03 = a constant reflecting the solubility of carbon dioxide in water. Units are [(mmol/L)/mmHg].

Having established that this incubator is a device to maintain mammalian cells under their physiologic conditions of high temperature, high oxygen consumption, high CO2 production, and high buffering capacity, it must now be realized that the exact opposite conditions pertain to fish cells (Table 3). Fish oxygen consumption is low, so their CO2 production is low. Because O2 levels in water are ∼1/30th that of air, fish hyperventilate to obtain it, thus ridding themselves of most of the CO2 they produce. Therefore “…the lowest pCO2 values in blood are observed in water-breathers; the highest in air-breathers.”42,43 Because their blood has less CO2, fish have less acid to combat and so their buffering system is minimal.45–48 Thus, “air alone can be a suitable gas mixture because of the naturally lower CO2 in fish.”49

Table 3.

Normal Arterial Blood Values for Man, Salmon, and Trout

Curiously, many laboratories have chosen to culture fish cells in a high-CO2 incubator, possibly because this is what is available from their colleagues down the hall. And indeed, such a system can “work” to keep fish cells alive. However, fish cells under high CO2 are exposed simultaneously to the high carbonic acid pumped in from the gas cylinder and the high dissolved bicarbonate added to the medium. The fact that these two conditions chemically counteract each other, maintaining a neutral pH, does not make either one typical for the organism. And no fish maintains its cells this way, because it does not have to. The fact that fish cells can be cultured successfully under mammalian physiological conditions shows that overall pH stability, rather than a particular concentration of CO2, is the critical factor for cell survival. A demonstration of this is that one can completely reverse the culture conditions and grow mammalian cells under low CO2 and low bicarbonate for long periods of time. Indeed, several vendors now market CO2-independent media to mammalian cell culturists, making gas cylinders and pressurized incubators unnecessary. This shows that cells of various species' origins can adapt to either high or low CO2 as long as pH is within range.

Having established that multiple media can be used for fish tissues, which medium is best? The published range is bewildering and follows the broad use of diverse medium recipes in mammalian cell culture. Table 4 lists the choices that appear in the articles referenced in this paper. However, this list is neither authoritative nor exhaustive as other media might equally be used. The major differences between these formulations are the relative levels of salts, buffers, vitamins, and amino acids. Fortunately for the fish culturist, these media are now mass produced in great quantity and many excellent technical references are given by the manufacturers (e.g., Gibco). For a complete list of what is in each medium, you are referred to the historical record of its development,50,51 as well as the current supplier of the product you intend to use.

Table 4.

Base Media Used to Culture Fish and Other Species' Cells

| Abbreviation | Name and References | Year | Original cell type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMRL-1066 | Connaught Medical Research Laboratories 1066206 | 1961 | Mouse fibroblast |

| DMEM | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium71 | 1959 | Embryonic mouse cells |

| Eagle's MEM | Eagle's Minimal Essential Medium207,208 | 1959 | Mouse fibroblast, human carcinoma |

| Ham's F12 | Ham's F1272 | 1965 | Mouse and hamster cell lines |

| L-15 | Leibovitz-1553,54 | 1963 | Monkey kidney, human carcinoma |

| M199 | Medium 199209 | 1950 | Chick embryo fibroblasts |

| RPMI 1640 | Roswell Park Memorial Institute 164090,210 | 1967 | Human leukocytes |

| WME | Williams' Medium E211 | 1974 | Adult rat liver epithelium |

By 1987, the most commonly used media for fish cells were Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM) and Leibovitz-15 (L-15; reviewed by Nicholson11). Uwa and Iwata compared the performance of MEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), L-15, Medium 199 (M199), and Connaught Medical Research Laboratories 1066 (CMRL-1066) in fin explant cultures from female medaka.52 For these tissues, they observed better growth using L-15, M199, and CMRL-1066, and noted that these contain “more amino acids, vitamins, nucleic acid components, and intermediary metabolites than MEM and DMEM” (p. 206). However, the number of studies conducted using MEM, DMEM, or similar formulas remains quite large.

Given what has already been said about CO2 concentrations, the medium L-15 deserves mention. L-15 is a solution of calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium salts fortified with 15 amino acids, 8 vitamins, and 10 mM glucose.53,54 It does not contain bicarbonate, but derives its buffering capacity from its amino acid profile and is pH stable in air (∼7.6). This provides a much closer match to the physiologic conditions of fish tissue and does not require pressurized incubators or gas supplies. If more stringent pH control is necessary, L-15 can be further adjusted with minimal bicarbonate, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), or Tris.55

Osmolarity

Having dissected the role of gases and buffers, we now turn to osmolarity. This variable is important because cells are eternally bathed not only in dissolved gases but also in dissolved salts. By definition, one osmole (Osm) is equivalent to one mole (6.023 × 1023) of osmotically active particles in solution. For example, 1 M NaCl has an osmolarity of 2 because each mole of salt dissolves into one mole of Na+ and one mole of Cl− simultaneously present. Two similar terms describe this contribution, which are often confused. Osmolality refers to the number of particles per weight of solution (Osm/kg), whereas osmolarity refers to the number of particles per volume (Osm/L). Because it is more convenient to measure fluids by volume, not weight, osmolarity will be the most common unit used.

A fish has both an outside and an inside osmolarity. Outside values vary a lot, depending on the species' habitats being freshwater, brackish, or marine (range = ∼0 mOsm/L to >1000 mOsm/L). Inside values vary less. For freshwater fishes, ∼300 mOsm/kg is a reasonable start and reference texts can provide more precise values for particular species or groups.56–59 Note that in a hypertonic solution, cells lose physiological water; therefore, a medium either isotonic or slightly hypotonic to the tissue is preferred.

Osmolarity can vary significantly between medium types, and also from lot to lot within a given medium. Adding serum, antimicrobials, and other compounds can further shift this value. So it is advisable to verify not only the osmolarity of the base medium but also the final, working medium in the culture dish within the incubator. Unlike pH, which can be monitored easily with colored indicators, osmolarity remains invisible. So it is usually both unmeasured and unreported. Measuring it at least once is a valuable training exercise, and will build confidence that your culture conditions are well controlled and appropriate to the species used. Indeed, osmolarity alone can be a stimulus for transcriptional and translational changes in cultured organs. Therefore, it should be monitored and maintained just as stringently as dissolved oxygen, pH, or temperature.

Incubation temperature

Unlike endothermic vertebrates, fishes have a wider range of body temperatures corresponding to their typical environments. A tilapia in Zimbabwe, for example, might experience water temperatures from 15°C to 40°C annually.60 Zebrafish, in fact, have one of the largest natural temperature ranges, reported to be from 6°C to 35°C in their South Asian habitats.61 The “optimal” incubation temperature for an explant will therefore vary by species, and will range more widely than a similar explant from mammalian tissue. In a study on freshwater pike, Bolliet et al. varied pineal gland explant culture conditions from 10°C to 30°C, consistent with the species' habitat temperatures.62 Unsurprisingly, this had a major effect on some physiological reactions. Your preliminary work should therefore establish what the desired range of temperatures is, and how to balance temperature's physiological effects with its other effects in vitro. All things being equal, low temperatures minimize bacterial/fungal growth and allow fewer medium changes, both of which can be of practical importance.

Medium additives

Second only to the choice of medium itself, medium supplementation can be bewildering. Viewed optimistically, medium supplements can boost explant performance above and beyond what the basal medium provides. Viewed pessimistically, they are elixirs of hope whose only effect is to add money to the experiment. Some compounds do have a place and may be valid choices if tested and optimized. Choosing three important classes to consider, I will describe animal sera, antimicrobials, and anti-inflammatories.

Animal sera

In the 1960s, several key articles established that calf serum increased mitotic rate in murine cell lines that were previously density-limited.63,64 That is, serum addition boosted RNA synthesis, protein production, and cell density in crowded conditions, increasing the carrying capacity of the culture vessel. This launched a major effort to analyze serum constituents and their effects.65,66 Briefly, serum contains nutrients, vitamins, and steroid hormones that cells can take in, as well as ligands they can detect through cell-surface receptors. However, it has long been recognized that the practical advantage of serum comes with the operational disadvantage of not knowing precisely what the active molecules are and how many are present. Therefore, a parallel scientific effort has been to develop serum substitutes67 or chemically defined media.68–70 The reviews by Higuchi,70 Barnes and Sato,68 and Taub69 are particularly recommended as they show a scientific debate stretching over decades on the culturist's key question: what is necessary to keep cells alive?

Despite great progress in defining cell requirements chemically, most prior studies have used serum and so you may be inclined to use it as well. However, realize that the effect of serum supplementation, and of medium recipes in general, is to encourage the exponential division of tumor-like cells in vitro—an advantage for the impatient bench scientist or the industry requiring large batches (>10,000 liters per bioreactor). Users of DMEM may perhaps not realize that the principal modification of Eagle's recipe was to increase all the vitamin supplements by a factor of four so that these would not become limiting in culture.71 So the DMEM in the bottle contains vitamins quadruple the concentrations normal to human plasma and as such may contribute certain artifacts to the gene expression and metabolism of cells cultured therein. Even totally synthetic media lacking serum have been formulated with the same aim. For example, Ham's F12 (1964) was made for expanding a specific transformed cell line—Chinese hamster ovary cells—in the context of single-cell inocula.72 Hence, the requirement for this lone cell to multiply quickly, and achieving this is viewed as a success. However, the same runaway mitotic rates, if detected in an explant, would be viewed as a failure because the goal is to maintain a differentiated tissue in a stable condition.

The significant deviations of many historical media, with their highly concentrated cocktails of nutrients and energy sources, from in vivo physiological levels have been recently summarized in a comprehensive chart,73 and there is exciting new work seeking to reformulate media more aligned with normal organs74,75 (e.g., Plasmax™ and Human Plasma-Like Medium). However, currently, these alternatives are not widely available and the default setup seems to be that most cell lines and explants are grown using similar medium recipes, most of which include serum supplementation.

If serum is to be used, from which species should it be derived? “The widespread use of fetal bovine serum (FBS) is almost traditional in lower vertebrate cell culture, and it is based, in part, on the fact that it has almost universally given satisfactory results. Undoubtedly, inertia is also a factor, for a majority of cell culturists have been reluctant to explore the feasibility of using serum from other animals.”76 Although evolutionary logic would seem to dictate a fish serum component, hundreds of in vitro studies show that mammalian serums—specifically FBS or its less-expensive variant, bovine calf serum (BCS)—perform just as well. Bovine serums work because their constituent growth factors are well conserved in vertebrate organisms. Fish cells have receptors for most, and so will happily accept these gifts from a cow or a goat.77 Boucher and Hitchcock discuss this issue and provide a mini-review of heterologous assays combining mammalian growth factors and cultured fish cells.78 In rare instances, some serums appear toxic to fish tissues, as reported for horse serum.79 However, these few reports must be interpreted carefully, as animal sera today are far more regulated, tested, and refined than they were in prior decades.

Because FBS and BCS are used so frequently in mammalian cell culture, these extracts are common, pure, and much less costly than fish serum. In contrast, “a reliable supply of fish serum of the same quality as mammalian serum is often difficult to obtain because fish blood volume is small and serum must be pooled from different animals.”49 This variation in quality may explain several reports of adverse results when fish-specific serums are used.80 However, reports of fish serum extraction are rare,27,81 and almost never repeated by more than one laboratory. In contrast, the use of FBS/BCS is so widespread that it presents a de facto gold standard for the culture of animal cells.

Antimicrobials and anti-inflammatories

In addition to applying antimicrobial compounds at the time of explantation, it is traditional to add them also to the explant in culture. At this point, strict old-school culturists will cringe. Many of us were taught that these compounds mask faulty technique and should not be used. Also, if the research question involves any aspect of the resident microbiota, antimicrobials defeat the purpose. For these reasons, some laboratories abstain. In general practice, however, most accept that technique is not always perfect. It is prudent to set a net in case the acrobat slips.

In contrast to the antimicrobial, which counters other creatures, the anti-inflammatory counters host responses. When a tissue fragment is cut from the animal, it reacts like a wound. At the morphological level, this involves cell death, secretion of adherent extracellular matrix onto nearby surfaces, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and migration of cells out of the explant. At the molecular level, wounded tissue emits damage-associated signals such as hydrogen peroxide,82 and proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factors and interleukins.83,84 In addition, all tissue fragments contain resident immune cells, which respond to these factors and secrete their own.85,86 For these reasons, an anti-inflammatory might be used immediately after dissection and for a short time in culture to reduce acute stress and improve explant outcomes.

In contrast to the nearly universal application of antimicrobials, instances of anti-inflammatory treatments in fish explant culture are quite rare. Exceptions are hydrocortisone16,87 and dexamethasone.88 Beyond this, the drug category seems largely unexplored. However, these agents have wide medical use and so small quantities in high purity are available cheaply. If physiological homeostasis is the goal, damping acute inflammation may restore tissue function more quickly and contribute to long-lived, stable explants. Therefore, judicious use of anti-inflammatories should be investigated, always with appropriate controls.

The role of fresh medium

If new medium is presumed clean and old medium dirty, frequent changes would seem ideal. Remember that endothermic vertebrates have high O2 consumption, high CO2 production, and high carbonic acid release. To absorb the acid, there is an opposing base—the bicarbonate ion—which becomes saturated eventually. Enter the culturist who rushes in to change the medium, avoiding toxic drops in pH. Or, as stated by my postdoc advisor, “The last step in the Krebs cycle is you with a pipette.” In contrast, ectothermic water-breathers have low O2 consumption, low CO2 production, and minimal acid to absorb. Also, the lower incubation temperatures for these species (25°C for warm-water fishes and 5°C–15°C for cold-water ones) keep antibiotics active and retard microbial growth. So the need for medium changes on fish cells is naturally reduced.

Interestingly, some authors report that long periods in unchanged medium support healthier explants with better morphology and histology. For example, 9-day cultures of mouse organs were improved by adding concentrated glucose and bicarbonate every 3 days rather than changing the medium entirely.89 But how can this be? One answer is that explants “self-medicate” by secreting steroid hormones, paracrine growth factors, and innate immune proteins into their surroundings. This makes the “conditioned” media prepared by the explant more suitable than the “unconditioned” media prepared by the researcher. If the researcher now rushes in to make an exchange, the explant-derived factors are drawn off and the tissue suffers. This observation has a long history and was emphasized by the formulators of the Roswell Park Memorial Institute media series, a set of over 1500 different recipes: “The constant flow-through of fresh medium is expensive and still does not provide a balanced ecology since cell products and other unidentified growth substances are lost.”90 Rather, the optimal schedule and intensity of medium changes (e.g., a 10% change vs. a 50% change) must be determined empirically. Finally, the method of medium exchange should not damage the tissue or cause unwanted changes in orientation.

Explant orientation and support

To identify the host niche for IPNV, researchers sought to culture monolayers of fish cells derived from various tissues. So the emphasis was on a strong attachment of the explant to the culture vessel, encouraging an adherent outgrowth. Classically, delicate explants have been stabilized by a clot of freshly prepared blood91 or a blob of nutrient agar.92 Other attachment substrates include layers of gelatin, laminin, or collagen. At the other extreme, nonattachment methods attempt to keep the explant edges free and exposed to the medium on all sides. Examples are agitated culture plates, shaking flasks, and rotating vials. The advantage of agitation is improved diffusion, but at some risk of tissue damage. Therefore, in the realm of static culture systems, there have been designed filters, grids, mesh bags, hanging-drops, or flow-through chambers. A frequently-cited advance was provided by Trowell,89,93 which paved the way for other techniques still in use.30 A recent adaptation adds a silicone ring on a glass coverslip, allowing real-time imaging of the explant by confocal microscopy.94,95 These and other key designs are shown in Figure 2, “Selected Explant Culture Supports.”

FIG. 2.

Selected explant culture supports. For clarity, components are not necessarily shown to scale.

You will notice that most of these successful blueprints position the explant projecting well into the gas phase and covered by medium only minimally. And why is this so? The reason is access to oxygen. Although fish cells are naturally less oxygen demanding, a steep concentration gradient is needed to supply it, particularly to the center of a solid explant. Oxygen is far less soluble in water (∼5 ppm, or 0.005%) than is available in air (∼200,000 ppm, or 20%). Therefore, the classic culturists discovered early that additional oxygen was best supplied by the gas phase.89 Thanks to the steady miniaturization of pumps and sensors, there are now sophisticated microfluidic systems that provide dynamic perfusion of medium formulations and real-time measurements of variables such as glucose and oxygen, further improving the conditions in the culture vessel.96–98

Viability assays

Even though situated in the best media with appropriate additives and optimal physical support, every explant has a limited lifespan. It is the obligation of the investigator to assess both the quantity and quality of explant life and to report these objectively. Sadly, many articles provide incomplete descriptions of explant health and fail to report clear criteria for inclusion in the experiment. This is unhelpful for all, but particularly for new culturists such as you, who need to estimate how many of your explants might prove viable. In clinical research, it is necessary to report how many patients participated in the trial, how many took their medication, and how many dropped out of the study. The remaining patients are then analyzed. If these percentages are never reported, it is unclear what efficiencies are expected and what sample sizes are necessary for the work. Therefore, explant culturists must testify with similar rigor. In this section, I discuss some qualitative and quantitative approaches to explant viability, some combination of which should be included in the monitoring and documentation of any experiment.

Visual appearance

Before the dawn of molecular biology, culture viability was most often assessed by eye. Thankfully, this check is still the fastest and easiest type of monitoring to perform. Just as a perceptive physician will note the patient's appearance, you will soon be aware of key visual signs. A “good” culture will have clear medium and few or no loose cells. The edges of the explant will be smooth or rounded, not ragged or necrotic. Healthy tissue looks compact and translucent, whereas dead tissue appears fluffy and opaque. In addition to providing an adequate scientific description, you should photograph your explants and include representative color figures in your report.35

Paraffin and plastic histology

The pathologist uses tissue architecture to diagnose health or disease. So if the goal of explant culture is to maintain healthy tissue, checking explant histology would be an excellent monitoring approach. Fifty years ago, this was the default expectation as stated by Fell: “Careful histological examination of organ culture is essential, and its importance can hardly be overemphasized.”2 The advantage of histological analysis is the density of information it provides on the entirety of the explant, with even the simplest histological stains providing vivid microscopic detail. The disadvantage is that sectioning is laborious and expensive. However, it can be well worth the effort to produce quality sections using paraffin99–103 or plastic techniques.104–106

Scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy

In the spectrum of microcopy techniques, these provide the highest resolution of cellular and subcellular structures. When used in conjunction with traditional histology, they are powerful assays to compare cells in vitro and in vivo. For example, Lamche and Burkhardt-Holm used paraffin sections, scanning electron microscopy, and transmission electron microscopy to validate long-term explants of rainbow trout epidermis, demonstrating that the fragments maintained epidermal tight junctions and actin-rich microridges.16 These are valuable data on the condition of cultured cells; the notable disadvantages are again the specialized equipment, training, and cost. For these techniques, a core facility will certainly be necessary.

Biochemical assays

As taught by Virchow, any anatomical change necessarily requires a chemical one. This leads to sampling the culture for the chemical signatures of physiological health or cytotoxicity. For example, damaged cells release lactate dehydrogenase and the supernatant concentration of this marker can be measured with a colorimetric indicator.107 Other methods examine the explant itself and the sampling thereof can be termed destructive or nondestructive depending on whether the explant is consumed by the assay.

For a catalog of common viability assays used in the in vitro drug testing, ecotoxicology, and tissue-engineering fields, the reader is referred to recent and historical technical reviews.108–111 The choice of assay depends on the organ explanted, physiological process being studied, explant size, and type of culture vessel. Note that most commercial kits are designed for monolayer cultures and must be adapted for explant use.112 Every assay has a detection limit, and a large dish with a small explant may not provide as many signal molecules as the same dish populated by a rapidly dividing cell line. Overall, the advantage of chemical indicators is that they can be measured more rapidly, more objectively, and in much larger throughput than histological or ultrastructural indicators. The disadvantage is that single chemicals lack breadth. Even so, the precision and economy of such methods give them a valuable place in the culturist's repertoire.

Optimization techniques

At this point, you will appreciate that there are many variables to optimize. However, most publications never indicate why specific culture conditions were chosen. Reading an article that includes only one set of conditions and no explanation as to why tempts one to walk the same road. To counteract this inertia it is recommended to read articles that include the authors' optimization attempts and report these in detail.13,14,16,52,55,79,81 Some of these articles use cell culture; others use organ culture. The common theme is a systematic study of experimental conditions and empirical outcomes. The reward will be an improved understanding of your culture system and a ready answer to the reviewer's question: “Why were these conditions used?”

Imaging

Most zebrafish laboratories already have effective mounting techniques for embryos and larvae, as well as access to high-quality imaging facilities. Therefore, applying similar techniques to a similarly-sized explant can be accomplished with very little new training or increased cost. For a menu of current methods, you are referred to the extensive literature on advanced microscopy for both living and fixed cells.113–115 One interesting application in this regard was a system to culture the lenses of blue acara (Aequidens pulcher) in custom acrylic chambers filled with optically clear media. The sides of each chamber were fitted with microscope cover glasses to provide a light path. The lenses in vitro were then tested by laser scanning to determine their optical properties under different temperature and osmolarities.116

Highlights of the Recent Literature

The cellular mechanisms responsible for health and disease can be approached in vitro in ways not always possible in vivo. The popularity of this approach is borne out by perennial advances in culture technology, viability assays, and imaging studies. In this section, I review three different works illustrating the use of explant culture in conjunction with other measurement techniques including gene expression, electrophysiology, and cell migration.

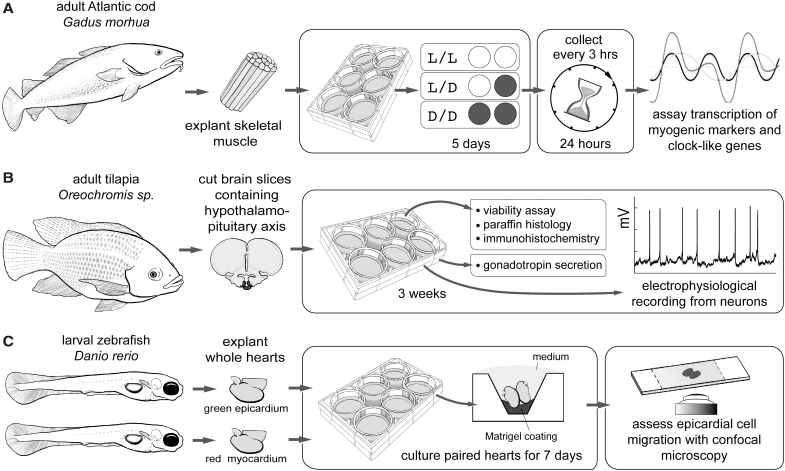

A circadian clock for cod mucle

Can peripheral organs maintain clock-like patterns of messenger RNA expression without eyes or a brain? Lazado et al. investigated the question of peripheral circadian oscillators in fish muscle tissue, a phenomenon important for the growth of individual fish and the production of aquaculture biomass.117 To do this, they used both muscle cell culture and muscle explant culture from a cold-water species, the Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Muscle blocks were isolated, washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline, and then rinsed in sterile DMEM with antibiotics (Fig. 3A). The final explant size was 4 × 4 × 1–2 mm. For stability, fragments were allowed to attach to a laminin-coated multiwell plate before medium addition. Explants were maintained in DMEM +15% FBS at 15°C in air. The medium was changed daily for 5 days, during which time, the explants were exposed to different photoperiods (light/light, light/dark, and dark/dark). At regular intervals, the tissue was collected to assay gene and protein expression. Although present initially, the expected circadian oscillation of key clock-like genes was lost in the cultured muscle explants. This result shows lack of autonomy in muscle tissue ex vivo, suggesting a “master” endocrine clock is necessary for circadian control.

FIG. 3.

Adventures in fish explant culture. (A) Lazado et al.117 (B) Bloch et al.118 (C) Yue et al.119 For descriptions, see text.

Endocrine activity of tilapia brain slices

In this work, Bloch et al. examined the hypothalamic/pituitary axis in tilapia, an important aquaculture species.118 Specifically, they wished to know how hypothalamic production of gonadotropin-releasing hormone induced the secretion of key pituitary hormones (luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone). This hormonal cascade is necessary for tilapia maturation and reproduction. So the investigators prepared brain slices “to preserve the basic structural and connective organization of the various cell types.” Freshly cut, 300-micron slices of tilapia brain—including both the hypothalamus and pituitary—were maintained in six-well plates on porous filter inserts (Fig. 3B). The medium was L-15 with 10% HEPES and 0.5% BSA, with changes every 2 days. Incubation was at 26.5°C and 5% CO2. Under these conditions, brain preparations could be maintained for up to 3 weeks as assessed by cell viability staining (propidium iodide), paraffin histology (hematoxylin and eosin stain), and electrophysiologic recording (patch-clamp technique). Extending the brain-slice method, investigators were able to perturb the system by applying hormone-supplemented culture media, and then measuring, using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, secretory products in the supernatant. The authors concluded that “organotypic hypothalamo-pituitary slice cultures conserve important neuroendocrine characteristics, such as cell organization, electrical activity, and hormone release” for several weeks in vitro.

Zebrafish cardiac co-cultures

Cell–cell interactions are necessary for the function of whole organs. In the heart, the epicardium interacts with the adjacent myocardium. In this experiment, Yue et al. wanted to observe zebrafish epicardial cells migrating over myocardial cells under different conditions.119 To do this, they isolated hearts from late-stage embryos (4–5 days postfertilization) of different transgenic strains and placed them pairwise in Matrigel-coated 60-well culture dishes such that ventricles were touching (Fig. 3C). Donor hearts were genetically labeled with either red (epicardial) or green (myocardial) fluorescent proteins for cell identity and tracking. Culture medium was L-15 with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin, with daily changes. Incubation was at 28°C with 5% CO2. Although “questionable” samples were discarded, some heart cultures remained healthy for up to 7 days. Over this interval, migratory behavior and gene expression were assessed by standard assays, including confocal microscopy and immunohistochemistry. In related experiments, both mutant and morpholino-treated heart tissues were investigated. Several other recent articles use adult hearts of this species,96,120,121 demonstrating the rich prospects for in vitro investigations of cardiac development, function, and regeneration.

Prospects and Challenges

In summary, fish explant cultures have a long history and established methodology. Classic culture techniques combined with novel molecular and microscopic approaches are not to be missed in the arsenal of discovery. The equipment and ingredients are both low cost and widespread, making this an important experimental platform for the creative fish worker. Recent studies show the potential of this work to analyze multiple teleost organ systems, bridging the single-cell and whole-organism perspectives. However, several challenges remain:

There has been little progress in developing media or supplements designed to support physiological homeostasis of the differentiated state versus high rates of cell division. Rather, media designed for the latter are applied to the former basically unchanged. In this respect, almost nothing has altered in the last half century and the words of Moore and Woods still apply: “Media that provide vigorous cell reproduction—too often the major goal of biologists in the past—may suppress cell differentiation. Furthermore, no single medium can be optimal for cells of different types and from different species. Most media, including those described in this report, are too much alike. A spectrum of very different media is needed.”90 There is also substantial room for improvement on live imaging and biochemical monitoring of explants in culture. Most viability assays are intended for monolayers and need to be adapted and validated for explant use. Finally, in vitro work should not be an isolated sect or scientific cul-de-sac. Fish laboratories should span these realms effectively, using the strengths and weaknesses of each method.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the staff of DePaul University Libraries for their efficient retrieval of many references herein. Drs. Jason Bystriansky and Jorge Cantú provided initial peer review.

Disclosure Statement

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Funding Information

Current research in the LeClair Lab is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R15-GM120664).

References

- 1. Stadtländer C, Kirchhoff H. Gill organ culture of rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri Richardson: an experimental model for the study of pathogenicity of Mycoplasma mobile 163 K. J Fish Dis 1990;13:79–86 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fell HB. The role of organ cultures in the study of vitamins and hormones. Vitam Horm 1964;22:81–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson DP, Dixon OW, Lizzio EF. Immunization and culture of rainbow trout organ sections in vitro. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 1986;12:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tyler C, Sumpter J, Bromage N. An in vitro culture system for studying vitellogenin uptake into ovarian follicles of the rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. J Exp Zool 1990;255:216–231 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landreth GE, Agranoff BW. Explant culture of adult goldfish retina: a model for the study of CNS regeneration. Brain Res 1979;161:39–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Al-Lamki RS, Bradley JR, Pober JS. Human organ culture: updating the approach to bridge the gap from in vitro to in vivo in Inflammation, cancer, and stem cell biology. Front Med 2017;4:148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grunwald DJ, Eisen JS. Headwaters of the zebrafish—emergence of a new model vertebrate. Nat Rev Genet 2002;3:717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meunier R. Stages in the development of a model organism as a platform for mechanistic models in developmental biology: zebrafish, 1970–2000. Stud History Philos Sci C 2012;43:522–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolf K, Quimby M. Established eurythermic line of fish cells in vitro. Science 1962;135:1065–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolf K, Quimby M, Pyle E, Dexter R. Preparation of monolayer cell cultures from tissues of some lower vertebrates. Science 1960;132:1890–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nicholson B. Fish cell cultures: an overview. In: Invertebrate and Fish Tissue Culture: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Inveterbrate and Fish Tissue Culture, Japan, 1987. Kuroda Y, Kurstak E, Maramorosch K (eds), pp. 191–194, Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, Japan, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munro ES, Midtlyng PJ. Infectious pancreatic necrosis and associated aquatic birnaviruses. Fish Dis Disord 2006;3:1–65 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mothersill C, Lyng F, Lyons M, Cottell D. Growth and differentiation of epidermal cells from the rainbow trout established as explants and maintained in various media. J Fish Biol 1995;46:1011–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mauger P-E, Le Bail P-Y, Labbé C. Cryobanking of fish somatic cells: optimizations of fin explant culture and fin cell cryopreservation. Comparat Biochem Physiol B 2006;144:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chenais N, Lareyre JJ, Le Bail PY, Labbe C. Stabilization of gene expression and cell morphology after explant recycling during fin explant culture in goldfish. Exp Cell Res 2015;335:23–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lamche G, Burkhardt-Holm P. Changes in apoptotic rate and cell viability in three fish epidermis cultures after exposure to nonylphenol and to a wastewater sample containing low concentrations of nonylphenol. Biomarkers 2000;5:205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald TM, Pascual AS, Uppalapati CK, Cooper KE, Leyva KJ, Hull EE. Zebrafish keratocyte explant cultures as a wound healing model system: differential gene expression & morphological changes support epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Exp Cell Res 2013;319:1815–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rakers S, Klinger M, Kruse C, Gebert M. Pros and cons of fish skin cells in culture: long-term full skin and short-term scale cell culture from rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Eur J Cell Biol 2011;90:1041–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bols N, Lee L. Technology and uses of cell cultures from the tissues and organs of bony fish. Cytotechnology 1991;6:163–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wolf K, Mann JA. Poikilotherm vertebrate cell lines and viruses: a current listing for fishes. In Vitro 1980;16:168–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fryer JL, Lannan C. Three decades of fish cell culture: a current listing of cell lines derived from fishes. J Tissue Cult Methods 1994;16:87–94 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hightower LE, Renfro JL. Recent applications of fish cell culture to biomedical research. J Exp Zool 1988;248:290–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Freshney RI. Culture of Animal Cells: A Manual of Basic Technique and Specialized Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swain P, Nanda P, Nayak S, Mishra S. Basic techniques and limitations in establishing cell culture: a mini review. Adv Anim Vet Sci 2014;2(4S):1–10 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sassen WA, Lehne F, Russo G, Wargenau S, Dübel S, Köster RW. Embryonic zebrafish primary cell culture for transfection and live cellular and subcellular imaging. Dev Biol 2017;430:18–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choorapoikayil S, Overvoorde J, den Hertog J. Deriving cell lines from zebrafish embryos and tumors. Zebrafish 2013;10:316–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Collodi P, Kame Y, Ernst T, Miranda C, Buhler DR, Barnes DW. Culture of cells from zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) embryo and adult tissues. Cell Biol Toxicol 1992;8:43–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lannan C. Fish cell culture: a protocol for quality control. J Tissue Cult Methods 1994;16:95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wolf K, Quimby M. Fish cell and tissue culture. Fish Physiol 1969;3:253–305 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Randall KJ, Turton J, Foster JR. Explant culture of gastrointestinal tissue: a review of methods and applications. Cell Biol Toxicol 2011;27:267–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Resau JH, Sakamoto K, Cottrell JR, Hudson EA, Meltzer SJ. Explant organ culture: a review. Cytotechnology 1991;7:137–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mainous ME, Smith SA. Efficacy of common disinfectants against Mycobacterium marinum. J Aquat Anim Health 2005;17:284–288 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leal MC, de Waal PP, Garcia-Lopez A, Chen SX, Bogerd J, Schulz RW. Zebrafish primary testis tissue culture: an approach to study testis function ex vivo. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2009;162:134–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmieder P, Tapper M, Linnum A, Denny J, Kolanczyk R, Johnson R. Optimization of a precision-cut trout liver tissue slice assay as a screen for vitellogenin induction: comparison of slice incubation techniques. Aquat Toxicol 2000;49:251–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lazado CC, Voldvik V. Temporal control of responses to chemically induced oxidative stress in the gill mucosa of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 2020;205:12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerbron M, Geraudie P, Rotchell J, Minier C. A new in vitro screening bioassay for the ecotoxicological evaluation of the estrogenic responses of environmental chemicals using roach (Rutilus rutilus) liver explant culture. Environ Toxicol 2010;25:510–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Siharath K, Nishioka RS, Bern HA. In vitro production of IGF-binding proteins (IGFBP) by various organs of the striped bass, Morone saxatilis. Aquaculture 1995;135:195–202 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Negatu Z, Meier AH. In vitro incorporation of [14C] glycine into muscle protein of Gulf killifish (Fundulus grandis) in response to insulin-like growth factor I. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1995;98:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Inui Y, Ishioka H. Effects of insulin and glucagon on the incorporation of [14C] glycine into the protein of the liver and opercular muscle of the eel in vitro. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1983;51:208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Landreth GE, Agranoff BW. Explant culture of adult goldfish retina: effect of prior optic nerve crush. Brain Res 1976;118:299–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parrish AR, Gandolfi AJ, Brendel K. Precision-cut tissue slices: applications in pharmacology and toxicology. Life Sci 1995;57:1887–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dejours P. Respiration in Water and Air: Adaptations-Regulation-Evolution. p. 179, Elsevier, New York, NY, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dejours P. Carbon dioxide in water- and air-breathers. Respir Physiol 1978;33:121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shipman C. Control of culture pH with synthetic buffers. In: Tissue Culture: Methods and Applications. Kruse P, Patterson M (eds), pp. 709–712, Academic Press, New York, NY, 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Heisler N: Chapter 6: Acid-base regulation in fishes. In: Fish Physiology. Hoar WS, Randall DJ (eds), pp. 315–401, Academic Press, Orlando, FL, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heisler N: Regulation of the acid-base status in fishes. In: Environmental Physiology of Fishes. Ali MA (ed), pp. 123–162, Springer, Boston, MA, 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ultsch GR, Jackson DC. pH and temperature in ectothermic vertebrates. Bull Alabama Mus Nat Hist 1996;18:1–41 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reeves RB. The interaction of body temperature and acid-base balance in ectothermic vertebrates. Ann Rev Physiol 1977;39:559–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Avella M, Berhaut J, Payan P. Primary culture of gill epithelial cells from the sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 1994;30:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Morton HJ. A survey of commercially available tissue culture media. In Vitro 1970;6:89–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yao T, Asayama Y. Animal-cell culture media: history, characteristics, and current issues. Reprod Med Biol 2017;16:99–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Uwa H, Iwata A: Growth and maintenance of ethisterone-induced anal-fin processes of a ricefish, Oryzias latipes, in vitro. In: Invertebrate and Fish Tissue Culture: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Inveterbrate and Fish Tissue Culture, Japan, 1987. Kuroda Y, Kurstak E, Maramorosch K (eds), pp. 203–206, Japan Scientific Societies Press, Tokyo, Japan, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Leibovitz A. Preparation of medium L-15. TCA Manual Tissue Cult Assoc 1977;3:557–559 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Leibovitz A. The growth and maintenance of tissue-cell cultures in free gas exchange with the atmosphere. Am J Hygiene 1963;78:173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Takahashi K, Copenhagen D. APB suppresses synaptic input to retinal horizontal cells in fish: a direct action on horizontal cells modulated by intracellular pH. J Neurophysiol 1992;67:1633–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Groff JM, Zinkl JG. Hematology and clinical chemistry of cyprinid fish: common carp and goldfish. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract 1999;2:741–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wolf K. Physiological salines for fresh-water teleosts. Progr Fish Cult 1963;25:135–140 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Griffith RW. Composition of the blood serum of deep-sea fishes. Biol Bull 1981;160:250–264 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nordlie FG. Environmental influences on regulation of blood plasma/serum components in teleost fishes: a review. Rev Fish Biol Fish 2009;19:481–564 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kime DE, Hyder M. The effect of temperature and gonadotropin on testicular steroidogenesis in Sarotherodon (Tilapia) mossambicus in vitro. Gen Comp Endocrinol 1983;50:105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Spence R, Gerlach G, Lawrence C, Smith C. The behaviour and ecology of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2008;83:13–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bolliet V, Begay V, Ravault JP, Ali MA, Collin JP, Falcon J. Multiple circadian oscillators in the photosensitive pike pineal gland: a study using organ and cell culture. J Pineal Res 1994;16:77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Holley RW, Kiernan JA. “Contact inhibition” of cell division in 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1968;60:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Todaro GJ, Lazar GK, Green H. The initiation of cell division in a contact-inhibited mammalian cell line. J Cell Comp Physiol 1965;66:325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dulbecco R. Topoinhibition and serum requirement of transformed and untransformed cells. Nature 1970;227:802–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Antoniades HN, Stathakos D, Scher CD. Isolation of a cationic polypeptide from human serum that stimulates proliferation of 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1975;72:2635–2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shea TB, Berry ES. A serum-free medium that supports the growth of piscine cell cultures. In Vitro 1983;19:818–824 [Google Scholar]

- 68. Barnes D, Sato G. Serum-free cell culture: a unifying approach. Cell 1980;22:649–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Taub M. The use of defined media in cell and tissue culture. Toxicol In Vitro 1990;4:213–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Higuchi K. Cultivation of animal cells in chemically defined media, a review. Adv Appl Microbiol 1973;16:111–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dulbecco R, Freeman G. Plaque production by the polyoma virus. Virology 1959;8:396–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ham RG. Clonal growth of mammalian cells in a chemically defined, synthetic medium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1965;53:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ackermann T, Tardito S. Cell culture medium formulation and its implications in cancer metabolism. Trends Cancer 2019;5:329–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leney-Greene MA, Boddapati AK, Su HC, Cantor JR, Lenardo MJ. Human plasma-like medium improves T lymphocyte activation. iScience 2020;23:100759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Voorde JV, Ackermann T, Pfetzer N, et al. Improving the metabolic fidelity of cancer models with a physiological cell culture medium. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau7314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]