Abstract

High school peer crowds are fundamental components of adolescent development with influences on short-and long-term life trajectories. This study provides the perspectives of contemporary college students regarding their recent high school social landscapes, contributing to current research and theory on the social contexts of high school. This study also highlights the experiences of college-bound students who represent a growing segment of the adolescent population. 61 undergraduates attending universities in two states participated in 10 focus groups to reflect on their experiences with high school peer crowds during the late 2010s. Similar to seminal research on peer crowds, we examined crowds and individuals along several focal domains: popularity, extracurricular involvement, academic orientation, fringe media, illicit risk taking, and race-ethnicity. We find that names and characteristics of crowds reflect the current demographic and cultural moment (i.e., growing importance of having a college education, racial-ethnic diversity) and identify peer crowds that appear to be particularly salient for college-bound youth. Overall, this study illuminates how the retrospective accounts of college-bound students offer insight into high school social hierarchies during a time of rapid social change.

High school peer crowds, reputation-based clusters of youth thought to share similar values, behaviors, and interests (Brown, 1989; Rubin et al., 2008), are hallmarks of the U.S. adolescent experience, coloring how students view high school, interact with peers, form their identities, and embark on different socioemotional and educational trajectories (Barber, Eccles, & Stone, 2001; Brown & Larson, 2009; Coleman, 1961; Crosnoe, 2011). Peer crowds, broader than students’ intimate friendships but more proximate than the entire student body, play an important role in how adolescents develop and help explain the lasting impact school experiences have on young people (Brown & Larson, 2009). The existence and evolution of peer crowds have been well-documented in the sociological and public health literature (Sussman et al., 2007) as well as in popular media (e.g., television shows and films like Glee, Mean Girls, and The Breakfast Club). Although research identifies continuities in peer crowds over time, crowds also evolve in ways consistent with demographic and cultural change. Thus, our conceptions of peer crowds must be updated to keep up with the changing meaning of adolescent life. With today’s diverse youth coming of age when the pressure to obtain a college degree is at an all-time high (Lemann, 2000; Taylor, Fry, and Oates, 2014), we aim to understand the peer crowd landscape of the increasing numbers of students with college aspirations, particularly with the increase of students of color in the U.S. school system.

Although the presence of peer crowds is undisputed, adolescents may view the peer crowd landscape differently based on their own crowd affiliations. Past crowds literature often documented the crowd experiences of a broad swath of adolescents rather than focusing on the perspectives of students from one particular crowd (for an exception, see Schwartz et al., 2017). Although the two approaches are complementary, more of the latter is needed for two reasons. First, by considering peer crowd landscapes generally, scholars may overlook more nuanced distinctions within subsets of crowds that may not be evident to non-members. In other words, greater peer crowd heterogeneity may exist within certain segments of the adolescent population (Brown & Larson, 2009). Second, researchers may miss important differences in how members of particular crowds view and rank other crowds in the high school landscape. For example, Horn (2003) found that adolescents described their own crowds more favorably and less stereotypically than other crowds. Focusing on how particular subgroups see the peer crowd landscape may illuminate important in-group/out-group perspectives (Rubin & Badea, 2007).

In this spirit, we conducted focus groups with a racially-ethnically diverse sample of college students at two universities, asking participants to reflect on their recent high school experiences. Participants’ descriptions informed our understanding of contemporary peer crowds. The unique composition of our sample, college students, offers a retrospective perspective about the high school landscapes experienced by college-bound students, a population that has more than doubled over the past several decades and continues to grow (Bound, Hershbein, & Long, 2009). By focusing on this subset of adolescents, our sample offers an in-group lens on college-bound students’ perspectives of high school crowds and an out-group lens on the experiences of non-college-bound students. By conducting a racially-ethnically diverse set of focus groups within this college-bound subgroup, we also gained insights into in-group and out-group perspectives on race-ethnicity that overlay both college-bound and non-college-bound crowds. Our results speak to the enduring nature of some key peer crowds, but also new crowd distinctions gleaned from the perspectives of college-bound adolescents.

Past Conceptualizations of Peer Crowds

This study is grounded in an extensive literature review to situate the novel perspectives of contemporary college students, formerly college-bound high schoolers, within the context of past crowd research. As shown in Appendix A, we organized the literature into: (a) conventional crowds related to three focal domains: popularity, extracurricular involvement, and academic orientation; (b) counterculture crowds related to two domains: fringe media and illicit risk taking; (c) racial-ethnic crowds; and (d) individuals that exist apart from any one crowd.

Conventional, counterculture, and racial-ethnic peer crowds.

Conventional and counterculture peer crowds have consistently been contrasted across past studies (Coleman, 1961; Eckert, 1989; Moran, Murphy, & Sussman, 2012; Rigsby & McDill, 1972), with conventional crowds embracing the values typically rewarded by the U.S. educational system and counterculture crowds opposing and/or providing alternatives to them. In a meta-analysis of peer crowd studies, Sussman and colleagues (2007) found that 37 out of 44 studies identified crowds that had oppositional beliefs toward academics (i.e., caring less about school and future careers) and school involvement (i.e., being less inclined to participate in extracurricular activities). Other studies have similarly pitted conventional and counterculture crowds against one another using different labels (mainstream versus non-mainstream; Moran et al., 2017), often drawing distinctions between deviant and non-deviant groups (e.g., Leathers vs. Collegiates and Intellectuals; Deviants as a separate crowd; Riester & Zucker, 1968; Sussman et al., 2007).

Past studies can be further organized with respect to how they differentiate conventional crowds by their focus on popularity, extracurricular involvement, and academic achievement. Crowds organized along these foci are quite stable in terms of their characteristics, such as academic-focused crowds being consistently defined by their academic achievement and Jocks by their sports involvement. These crowds have occupied similar locations in the social hierarchy over time, including the popularity-focused crowds who have sat atop the hierarchy for decades.

Our review of the crowd literature also divided counterculture crowds along two core domains: fringe media (e.g., oppositional, non-mainstream artistic genres; Arnett, 1991; Selfhout et al., 2009; Sussman et al., 2007) and illicit risk taking (e.g., drugs, violence). Although conventional crowds may engage with certain forms of media (e.g., Pop music) and participate in illicit risk-taking (e.g., alcohol consumption among Jocks; Miller et al., 2003), these factors define counterculture crowds. The illicit risk-taking crowds in past research include the Leathers known for drinking and fighting (Reister & Zucker, 1968), the Criminals known for their illegal activities (Eccles & Barber, 1999), and the Druggie/Stoners known for their affinity to marijuana and other drugs (Moran, Murphy, & Sussman, 2012). Fringe media crowds include Hippies (Riester & Zucker, 1968), Punk Rockers (Kinney, 1993), Emo/Goths and Alternatives (Urberg et al., 2000), and Hip Hops (Lee et al., 2014).

In addition to the conventional and counterculture themes, the proliferation and diversity of racial-ethnic crowds in the peer crowd literature reflect the changing demographics of the school age population (Brown, Herman, Hamm, & Heck, 2008). The placement of racial-ethnic crowds in the peer crowd landscape is, however, complex because these crowds may sometimes be seen as encompassing a domain of their own, in which race-ethnicity is the defining characteristic, but other times may overlap with conventional or counterculture domains. Race-ethnicity’s role as a salient, defining crowd characteristic may also depend on the demographic characteristics of the school and respondents. For example, if participants attend an exclusively non-Hispanic White (hereafter, White) school, then race-ethnicity would be unlikely to define crowd membership. Conversely, White students in a multiethnic high school may group classmates based solely on their race-ethnicity, while classifying White peers into crowds based on abilities, popularity, and interests (Brown et al., 2008).

Racial-ethnic crowds in the existing literature reflect this complexity. Some have been defined by salient racial-ethnic and generational (e.g., first or second generation) markers in multiethnic schools (e.g., Mexicans, Blacks, FOBs; Brown et al., 2008; Pyke & Dang, 2003; Nguyen & Brown, 2010). Others have recognized crowd heterogeneity within race-ethnicity (Matute-Bianchi, 1986; Lee et al., 2014). For example, Lee and colleagues (2014) identified several peer crowds among Black youth, including a counterculture, fringe media-based Hip Hop crowd and conventional Preppy and Mainstream crowds.

Individuals.

Past research also identified youth who were not members of specific peer crowds. Although recognizable and important to their school landscapes, these groups of individuals have not been considered crowds because they either fell outside of the high school peer crowd structure, blended into the background, or floated among multiple peer crowds. Some such individuals had conventional orientations toward school, and others countercultural. Those with conventional orientations but no acknowledged peer crowd have been referred to as Leftovers, Averages, Nobodies, or Normals. Individuals with counterculture orientations have been referred to as Loners (Clasen & Brown, 1985; Brown et al., 1993; Durbin et al., 1993), Outcasts (Clasen & Brown, 1985; Brown & Lohr, 1987), and Misfits (Moran et al., 2012). Some of these students were solitary by choice, but others were socially excluded and labeled by peers in derogatory ways. A last group of individuals, Floaters, moved among peer crowds. Although not primary members of any crowd, Floaters may have served an important bridging function between crowds and, thus, enjoyed a considerable amount of popularity.

Considering the Peer Crowds of Contemporary College-Bound Students

Despite the consistency in peer crowds over time, macro-level demographic trends change the high school landscape, which influences the emergence, disappearance, or changing characteristics of crowds (Crosnoe, 2011; Milner, 2006). One such trend is the growing importance of a college education. The increasing credentialization of U.S. society, along with the decline of blue collar industries and associated well-paying jobs for those without a college degree, has led to more students attending college than ever before (McFarland et al., 2018). College, while previously reserved for the elite, is now widespread and expected across demographic segments of young people (Lemann, 2000; Taylor, Fry, & Oates, 2014).

Another macro-level trend influencing adolescents’ high school experiences is the growing racial-ethnic diversity in the U.S. high school population. Roughly one half of students in U.S public schools identify as non-White, compared to 41% two decades ago, a figure that is projected to increase over coming decades (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). In response to growing diversity and rising inequality between those with and without a college degree (Taylor, Fry, & Oates, 2014), great efforts have been made to ensure that more adolescents, especially students of color, attend college (Tienda, 2013). Perhaps, as a result, the composition of college-bound students is more racially-ethnically heterogeneous than ever before (McFarland et al., 2018; Tienda, 2013), pointing to the importance of understanding the experiences of an expanding and increasingly diverse college-bound adolescent population.

Our approach complements prior studies by drawing on a racially-ethnically diverse set of focus groups with college students to gain insights into their recent experiences as college-bound high schoolers. Our review identified just one explicitly Collegiate crowd, and it reflected the 1960s context of elite college attendance (Riester & Zucker, 1968). We anticipate that today’s college-bound youth will span socio-economic and racial-ethnic strata and that their salient peer crowds will intersect the conventional domains of academics, extracurricular involvement, and popularity. Academics may combine with extracurricular participation among today’s college-bound youth, since college admissions typically emphasize well-rounded students who excel across a range of characteristics (Bound, Hershbein, & Long, 2009). Among college-bound students, those who excel across these areas will also likely occupy high positions in the social hierarchy perceived by college-bound students (Goldin & Katz, 2009).

College-bound youth may also describe crowds in ways that reflect their unique perspectives, suggesting greater peer crowd heterogeneity from in-group perspectives (Schwartz et al., 2017). For instance, college-bound youth may have insights into the pressures Athletes and Brains face as they strive to gain admittance into competitive colleges (Ryan et al., 2007; Rubin & Badea, 2007). From an out-group perspective, we may find that college-bound youth perceive peer crowds to which they do not belong less favorably and more stereotypically. College-bound youth may have less positive views of non-college-bound peers, including those within conventional crowds who do not excel academically or in a specific extracurricular activity. Counterculture crowds may also be a part of the out-group, since they often oppose the mainstream reward system to which college-bound students ascribe. Fringe media consumption has also been indirectly linked to lower academic achievement (Katz et al., 1974; Roe, 1995), further suggesting separation of this crowd from college-bound students, who emphasize the academic credentials necessary for college admittance.

In addition to general in-and out-group perspectives across college-bound youth, we also anticipate an overlay of racial-ethnic perspectives. Diversity may affect both how college-bound students of color see themselves within peer crowd structures and how White college-bound students view the high school landscape (Garner et al., 2006; Milner, 2006). In this context, out-group bias may lead to perceiving those from other racial-ethnic groups in monolithic, stereotypical ways while at the same time perceiving greater within-group heterogeneity.

Aims and Research Questions

Stemming from this synthesis of the literature (for a more detailed literature review see Appendix A) and the current importance of studying the college-bound high school landscape, this study poses two research questions: (a) How many and what types of crowds predominate in contemporary U.S. high schools from the retrospective perspective of a diverse set of college-bound students? (b) How do these crowds compare with those evident in past literature?

Method

In 10 focus groups, 61 undergraduate students at two universities described the peer crowds in their high schools. Local institutional review boards approved the study protocol.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from nine undergraduate classes offered by sociology, psychology, and kinesiology departments at two large public universities located in big cities in the Midwest and Southwest. Interested students completed a screener, reporting their birth year, race-ethnicity, gender, and the size and location of their high school. We included students who attended high school in the U.S and were born between 1990 and 1997. Most participants were between the ages of 19 and 22. Of the 400 students who completed the screener, those selected received an email with the time and location of their scheduled focus group. Nearly half of those selected participated (48%); nonparticipants primarily cited scheduling conflicts. Students received a $50 cash incentive at one site; $20 at the other.

We used implicit stratification to create focus groups with the desired characteristics shown in Table 1. Lists were first randomly ordered, and then the first listed student with each targeted combination of characteristics was selected. For instance, in Group 1, we selected the first-listed White, Black, Latinx, and Asian/American Indian/Alaska Native/Other student of each gender in the Midwest who had attended a large high school (800+ students). We continued down the randomly-ordered list to comprise the next groups in similar fashion. We first created four racially-ethnically heterogeneous and gender-balanced groups in the Midwest location. Three groups had students from large high schools, and the fourth had students from small and medium size schools (< 400; 400–800 students). In the Southwest, groups were comprised of students who all had attended small or medium/large schools. Given emergent themes related to race-ethnicity, we designed one of four Southwest focus groups to be all Latinx, and, we added two racially homogenous (all White; all Black) groups in the Midwest location. In all cases, we invited eight students to participate, but from four to eight attended due to no-shows.

Table 1.

Description of Focus Groups

| Number of Participants |

School Size | Race-Ethnicity | Sex/Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | ||||

| Group 1 | 6 | Large | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 2 | 7 | Large | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 3 | 8 | Small/Medium | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 4 | 7 | Large | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 9 | 6 | Large | White | Male and Female |

| Group 10 | 4 | Large | Black | Male and Female |

| Southwest | ||||

| Group 5 | 5 | Large | Heterogeneous | Male, Female, Non-binary |

| Group 6 | 6 | Small | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 7 | 8 | Medium/Large | Heterogeneous | Male and Female |

| Group 8 | 4 | Medium/Large | Latina | Female |

Note. Small refers to students who attended high schools with less than 400 students. Medium refers to students who attended high schools with 400 – 800 students. Large refers to students who attended high schools with 800+ students. Respondents were given the option to choose Male, Female or Other on the recruitment screener. Eight participants were recruited for each focus group; however, the varying number of participants reflects respondents who did not show up for their focus group. Heterogeneous focus groups consisted of a mix of students who may have identified as any of the following: Black/African American, Latinx, Asian/Asian America, White, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Other. Groups are numbered in the order we conducted each focus group.

Procedures

A graduate student previously unknown to participants moderated each focus group. One or two additional graduate students took notes. Most groups took place on weekday afternoons in university classrooms; one was on a weekday evening. Each session lasted approximately 90 minutes. The moderator followed a semi-structured guide consisting of three main parts: 1) naming peer crowds, 2) describing peer crowds, and 3) ranking peer crowds by status position. The moderator first defined peer crowds to students saying, “A ‘crowd’ or ‘clique’ is a group of students that you would describe by a label; they may act similar and do the same sorts of things, even if they don’t always spend a lot of time together,” a definition in line with Brown (1989). Students then independently brainstormed the peer crowds present in their high schools on post-it notes. The moderator next placed these post-its on a board, while participants discussed each crowd’s characteristics. Participants then identified and grouped similar crowds, typically between five and ten, with crowd members’ characteristics (e.g., race-ethnicity, gender, income, grades, health, activities) and social status rankings discussed next (see Appendix B for the full moderator guide). The groups concluded with students sharing final thoughts.

Suitability of Approach

The study builds on the seminal Social Type Ratings approach developed by Brown (1989) and adapts this approach for college students, as inspired by Milner (2006). Brown’s approach had small groups of high schoolers brainstorm their school’s crowds before coming to consensus on major crowds and leaders. Complementing this approach, our adaptation to college students not only captured the perspective of an important subset of contemporary high schools (college-bound students), but also engaged with students who attended different high schools. In addition, distance and maturity may inform the perspectives of college students. The focus group context stimulated memories and conversations, allowing participants to build on each other’s perspectives and identify points of consensus and divergence in real time (Halcomb et al., 2007; Kitzinger, 1994; Krueger & Casey, 2000). Collective memory prompting was especially useful since participants were several years out of high school, rather than immediately immersed in the experience, making hearing others’ descriptions especially useful. Relative to individual interviews, the focus group context also facilitated reflection because multiple participants took turns speaking, giving participants more time to think and listen to others than in dyadic turn taking (Morgan & Krueger, 1993) and mirrored other informal contexts where adolescents discuss crowds. We used multiple strategies to elicit engagement, such as brainstorming on post-it notes and encouraging contributions (Colucci, 2007; Kitzinger, 1994), so that each participant had a chance to share, ask clarifying questions, and challenge notions of certain crowds.

Coding and Analysis Plan

We thematically analyzed the focus group data (Braun & Clarke, 2013; Kreuger & Casey, 2000; Massey, 2011) using three deductive and inductive approaches (Ansay, Perkins, & Nelson, 2004; Greenbaum, 2000). We first identified articulated themes by coding direct responses to questions and prompts from the discussion guide (e.g., what kinds of clothes did students in certain peer crowds wear, how well did they do in school; see Appendix B). We then coded attributional themes, which we had brought to the study (e.g., our expectations that academically ambitious students might have elevated status). Finally, we identified emergent themes that contributed to new insights and hypothesis formation (e.g., specific in-and out-group perceptions of racial-ethnic crowds). The focus group was the primary unit of analysis, consistent with the perspective that focus group participants express their thoughts within a larger social context (Hollander, 2004). The voices of the individual participants were heard as well through their quotes describing crowds. We also attended to counter themes and alternative perspectives (Hyden & Bülow, 2003; Kitzinger, 1994; Massey, 2011). For example, one participant in a racially-ethnically heterogeneous group acknowledged that, “it’s totally not ok” to define crowds by race-ethnicity (Group 7).

To implement this analytical strategy, research team members audio-recorded the focus group discussions, which were then professionally transcribed by an outside service. After the final focus group, three graduate students performed thematic analysis of the qualitative data, using MAXQDA (Version 12.1.3). In line with a consensus coding approach, two of the three students initially coded each transcript, applying the articulated, attributional, and emergent themes, while also flagging statements that contradicted them. The emergent themes were discussed collectively for possible inclusion. In the final coding round, the third student resolved coding discrepancies and reviewed each transcript for completeness, including the application of any new codes that had emerged since that transcripts had originally been coded.

Results

Number and Types of Crowds

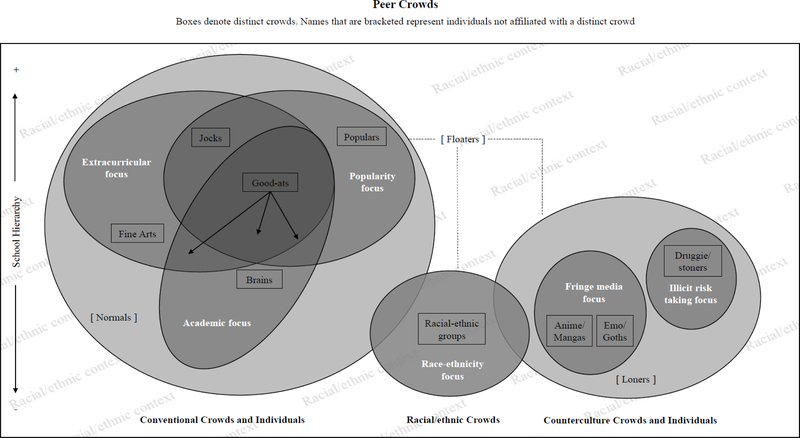

Overall, focus group participants identified nine peer crowds and three types of individuals without crowds. As visually depicted in Figure 1 and summarized in Table 2, these crowds and individuals were classified based on their adherence to conventional or counterculture norms and values, as well as race-ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Peer Crowd Landscape According to Contemporary College Students

Table 2.

Peer Crowd Descriptions

| Name | Number of Focus Groups Identifying Listed Crowd |

Position in Hierarchy |

Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | |||

| Populars | 9 | Top | Rich and/or attractive students; well-known and known to party |

| Jocks | 6 | Top | Affiliated with a sports team; well-known and known to party |

| Good-Ats | 6 | Near Top | Well-rounded and well-liked |

| Fine Arts | 10 | Middle | Skilled in an artistic endeavor |

| Brains | 8 | Middle/Bottom | Excel academically and take advanced classes |

| Floaters* | 3 | Top | Float between groups |

| Normals* | 2 | Middle/Bottom | Unknown, invisible |

| Counterculture | |||

| Druggie/Stoners | 7 | Middle/Bottom | Use (and sometimes distribute) marijuana |

| Emo/Goths | 5 | Bottom | Dark dress; Screamo Music |

| Anime/Manga | 5 | Bottom | Love Anime/Manga (Japanese video games and graphic novels) |

| Loners* | 4 | Bottom | Keep to themselves; low self esteem |

| Race-Ethnicity | 9 | Bottom | Members of a non-White racial-ethnic group |

Note.

denotes individuals

We classified five crowds (Populars, Jocks, Good-Ats, Fine Arts, and Brains) and one set of individuals (Normals) as conventional. Several of these crowds mirrored prior studies, such as the labelling of Elites (i.e., Populars), Academics (i.e., Brains), and Athletes (i.e., Jocks) as “mainstream” crowds (Moran, Murphy, & Sussman, 2012; Sussman et al., 2007). Because Fine Arts and Good-Ats students were described as participating in school-sanctioned extracurricular activities, reflecting values and activities rewarded by schools, we also considered them conventional crowds. Normals were classified as conventional because they avoided deviant activities and conformed to adult standards (Dolcini & Adler, 1994). They were also considered individuals, consistent with prior studies (Brown et al., 1993; Nichols & White, 2001), because they lacked a distinctive focal crowd characteristic.

The counterculture crowds included Druggie/Stoners, Anime/Mangas, and Emo/Goths. Our classification was consistent to prior literature, finding non-mainstream groups consisting of crowds that were deviant (i.e., Druggie/Stoners; Sussman et al., 2007) or non-conforming to school-rewarded values like achievement and popularity (i.e., Anime/Manga, Emo/Goths; Moran, 2009) (Moran, Murphy, and Sussman 2012). We considered Loners as counterculture individuals because of their low attachment to school, subpar academic performance, and non-group nature (Demuth, 2004; Parker & Asher, 1987). Focus group participants described counterculture members as clustered at the bottom of the social hierarchy, although Druggie/Stoners were described closer to the middle because of their connections to the Populars as occasional suppliers of marijuana. The Emo/Goths and Anime/Mangas were defined by their affiliations with fringe media, with the former listening to Screamo music and emulating these musicians’ dark aesthetic, and the latter admiring and consuming Japanese animation. Finally, focus group participants described Loners as keeping to themselves and having low self-esteem. Loners were described as the “kinda kids that would shoot up a school” (Group 5), suggesting that Loners were also sometimes feared by other students.

As anticipated, focus group participants described racial-ethnic crowds in complex ways that were both separate from and overlapping with conventional and counterculture domains. These racial-ethnic crowd descriptions differed by the race-ethnicity of the focus group members discussing them. While White focus group participants often described race-ethnic crowds as catch-all groups (e.g., the Black kids, the Hispanics), Black and Latinx participants referred to racial-ethnic-based groups as a home base for students that were also involved in other crowds. Students of color also saw richer diversity regarding both conventional and counterculture peer crowds within racial-ethnic identity groups.

The final group of individuals, Floaters, was identified by focus group participants as a set of highly regarded students that had multiple crowd affiliations (Dolcini & Adler, 1994; Nichols & White, 2001) across conventional, counterculture, and racial-ethnic domains. Floaters were described as defying the rigid confines of a single peer crowd while concurrently being enmeshed in many of them. The ability of Floaters to move freely among crowds, while maintaining high status among their peers, highlighted Floaters as bridging ties, connecting crowds and individuals (Burt, 2004).

Comparing Crowds to Past Literature

The crowds described by our focus groups of college students reflected both continuity with and distinction from previous studies as well as the anticipated in-and out-group perspectives.

Conventional crowds.

Good-Ats’ presence (identified in six of ten focus groups) and high social status were consistent with our expectation that college-bound students’ in-group perspective would elevate the intersection of all three conventional strands of academics, extracurricular involvement, and popularity. Although similar to Coleman’s (1961) Athlete-Scholars and Beautiful Brains, the Good-Ats, described by focus group participants not only excelled in academics and sports but were also leaders in extracurricular activities. This well-rounded quality and accompanying popularity may have resulted from our sample recognizing the value that universities place on students who excel in both academic and non-academic pursuits (Kaufman & Gabler, 2004; Swanson, 2002).

In addition to this newly identified Good-Ats crowd, the Fine Arts crowd was more prevalent (identified by every focus group) and higher in status than the Music-Drama, Performers, and Special Interests crowds noted in prior studies (Adderley, Kennedy, & Berz, 2003; Clasens & Brown, 1985; Cusick, 1973; Morrison, 2001), suggesting the broad importance of involvement in extracurricular activities for attending college (Eccles & Barber, 1999). Of note is that the Fine Arts crowd was often subdivided by type of art (e.g., band, choir, visual art, dance), with one focus group participant remarking that “the theatre kids hung out with the theatre kids [and] the band kinds hung out with the band kids” (Group 7). Our college student sample may have recognized these distinctions given the value of excelling in a specific pursuit for college applications. One participant noted that peers in the Fine Arts crowd were “those…kids that were gonna go to college” (Group 6).

Brains’ characteristics and status were also consistent with the prior literature, although focus group participants described Brains as experiencing amplified academic-related anxiety relative to prior studies (Doornwaard et al., 2012; Randall, Bohnert, & Travers, 2015). One focus group participant suggested that “[the Brains] were mentally less healthy…because they were stressed from doing so much work all the time” (Group 5). Particularly novel was that parents’ expectations spurred such anxiety. Focus group participants described Brains as fearing “piss[ing] off [their] parents” (Group 9) in school or in their social lives, potentially reflecting the increasing competitiveness of admittance into top colleges, which would be especially salient in our sample.

Similar to prior studies, our sample of college students placed Populars and Jocks at the top of the social hierarchy. According to a Group 5 discussion:

Interviewer 1: : Who would be at the top?

Interviewee 1: : Popular?

Interviewee 2: : Jocks.

Interviewee 4: : Popular and jocks.

Interviewee 2: : They go together, yeah.

Also consistent were views about the Populars’ and Jocks’ social activities, such as partying, having parents who paid for their children’s new clothing, cars, and “alcohol for their kids for parties” (Group 6) and who “lived their own dreams through their kids” (Group 5). Popular and Jocks’ social domination through bullying also continued, as the following quote exemplifies between the [Populars, Jocks] to Anime. It wasn’t outwardly mean. It was a lot of passive aggressive turning into aggressive, aggressive. Every time someone would get close to them. If an Anime kid got too close to a [Popular or a Jock] it would be like…they knew better…” (Group 8)

Yet, focus group participants also described how technology has shifted bullying. Populars and Jocks interacted with other groups using social media “as a wall” (Group 5) to hide behind when engaging in bullying and to showcase their popularity. For example, reflecting their higher status, Populars and Jocks were said to be known in school as “those names you see on Facebook and Instagram” (Group 6), the students that “have probably the most [Instagram] followers” (Group 9), and the students about whom “everyone knew all [their] business” (Group 2).

Counterculture crowds.

Our college student participants’ descriptions of counterculture crowds and individuals reflected contemporary culture, although each crowd demonstrated parallels with past studies. The fringe media-focused counterculture crowds, Emo/Goths and Anime/Mangas, reflected modern oppositional music, art, and use of the Internet, with “ideas coming from social media” (Group 9). Like past counterculture crowds, such as Burnouts, Basket Cases, and Freaks, the Emo/Goths were defined by their obsession with “screamo” music in addition to the darker elements of their appearances and personalities. Focus group participants described them as “wearing black all the time” (Group 1), being dark “Halloween types kinda...think cemeteries” (Group 4), and as “glorifying the low confidence thing… doing self-harming things, definitely cutting… and [having] eating disorders” (Group 4). Focus group participants described how this counterculture crowd used social media “as an outlet to express themselves” (Group 9), consistent with recent evidence of blogging and participating in online forums related to methods of self-injury, justifications for such behavior, as well as experiences of peer victimization (Phillipov, 2010).

Focus group participants described Anime/Mangas as being unattractive, outlandish, and socially awkward, “They probably wear clothing that represents video games and Anime,” said one participant. Another participant in the same focus group added, “Yeah, a lot of fandom stuff and cosplays [dressing as Anime characters]. Colored hair. …You have to have weird colored hair and headphones” (Group 4). Although Anime/Mangas were not identified in prior studies, they resembled Geeks, Dorks, Nerds, and Dweebs in past U.S.-based studies as well as the Computer Geek crowd reported among Singapore youth (Sim & Yeo, 2010), given their interests in computers and fringe media like “video games, comic books, and Manga” (Group 4). The presence of the Anime/Manga crowd demonstrates how contemporary youth can use technology and social media to share and consume cultures across countries. For example, one focus group participant referred to Anime/Mangas as “people who tend to watch Pokémon or Japanese types of shows [and] read Japanese comics” (Group 5). Another explained that Anime/Mangas’ “social life is online rather than [at] the mall or the movies” (Group 7).

Druggie/Stoners were placed mid-level in the social hierarchy, being connected to and benefitting socially from interaction with crowds nearer the top (i.e., Populars and Jocks). The higher-status peer crowds “[had] money to buy [drugs]” (Group 5) and often befriended Druggie/Stoners who provided drugs, perhaps contributing to their popularity. At the same time, focus group participants explicitly stated that the Populars were “customers…[and] weren’t necessarily hanging out with [the Druggie/Stoners]… just inviting them” (Group 7) and that they “wouldn’t say Stoners are like popular kids, but the Stoners were kind of popular” (Group 10). These connections of Druggie/Stoners to higher-status groups is consistent with some prior research (Kinney, 1993), but not others (Garner et al., 2006; Schwartz et al., 2017).

Racial-ethnic crowds.

As anticipated, discussions of racial-ethnic crowds were complex and varied depending on the racial-ethnic composition of the focus groups (Brown et al., 2008; Garner et al., 2006). On the one hand, some participants described the absence of race-ethnicity as a salient crowd characteristic, due to their schools’ racial-ethnic homogeneity. One student explained how her high school “was so, so, so, so white” (Group 10) and another that her school was “all Hispanic” (Group 8). Another focus group participant explained that, even though other participants described students that partied on the weekends to be primarily White, he “came from a primarily minority school, so [he] wouldn’t say [that students that party] are White” (Group 6).

In other cases, racial-ethnic characteristics were attached to crowds, but the content and tone depended on focus group participants’ race-ethnicity. Suggesting out-group homogeneity bias (Ryan et al., 2007; Rubin & Badea, 2007), White participants described monolithic racial-ethnic crowds defined by stereotypes, consistent with previous research (Larkin, 1979). A Black participant in a racially heterogeneous focus group brought attention to this phenomenon, exclaiming at one point, “Where [do] the White kids go?” (Group 3) as his White peers generated racially homogenous crowds. For example, White participants described young women in the Latinx crowd stereotypically as “sassy” (Group 4), wearing heavy make-up and tight clothes. White focus group respondents also used racially coded language to describe Black students as “ghetto” (Groups 5, 7, 10) and “baby mommas and baby daddies” (Group 5) and presumed their affiliations with gangs and guns. Consistent with a discourse of difference (Bonilla-Silva & Forman, 2000), White participants stated very clear beliefs about racial-ethnic groups despite admitting that they did not pay much attention to them. Placing racial-ethnic crowds at the bottom of the social hierarchy, White participants blamed students in these groups for isolating themselves from the rest of the student body. One focus group participant noted: “if you purposefully go with a certain group ethnicity or race group, then people look down on it more like, ‘Oh look at them’” (Group 7). White participants also engaged in in-group bias when they consistently described those located at the top of the social hierarchy, such as the Populars and the Brains, as primarily White and placed racial-ethnic groups towards the bottom of the social hierarchy.

This stereotyping process by White respondents was especially striking when compared to conversations within the solely Black and Latinx focus groups, again demonstrating the in-group/out-group homogeneity phenomenon (Ryan et al., 2007; Rubin & Badea, 2007). Black and Latinx focus group members reported greater within-group heterogeneity. For instance, a Black focus group participant struggled to define a Black crowd when she explained, “there’s so much variation. You have good-looking Black people. You have not good-looking Black people. You have smart Black people and not so smart, you have healthy and then not healthy” (Group 6). When students of color identified racial-ethnic crowds, they saw them as home bases to which they were automatically members, in a positive way. One focus group participant described how a student of color could not be “completely in another group because they were in [a racial-ethnic] community by default [because] that’s just who they are” (Group 6).

Discussion

This study extends the literature on adolescent social contexts by providing insights from a diverse set of college students on their recent high school peer crowd landscapes. The growth in the proportion of young people who are college-bound and the centrality of a college degree to upward mobility in contemporary U.S. society highlight the importance of these perspectives. Our findings reveal commonality and difference in relation to seminal crowd research in terms of conventional, counterculture, and racial-ethnic crowds as well as individuals who are apart from or float across them. We group our discussion around three themes: (a) crowds identified in our study that seem especially salient to college-bound students (Good-Ats, Fine Arts), (b) other conventional and counterculture crowds, as seen through the lens of college students, and (c) the importance of in-group and out-group perspectives in discussing race-ethnicity.

Reflecting on their experiences as college-bound high schoolers, our focus group participants identified a novel crowd, the Good-Ats. Focus group participants differentiated Good-Ats from the academically-focused Brains of the past and present. These multiply-involved Good-Ats crossed the academic and extracurricular foci within conventional crowds and reflected the need for college-bound students to appear “well-rounded” in college applications. Good-Ats’ high standing in the social hierarchy led to further intersection with the popularity domain, reflecting the in-group preferences of our college student sample. Given the increased value and growing rate of higher education today, future studies might see if this crowd replicates and holds a high-status position, especially among non-college-bound students.

The Fine Arts crowd identified by our participants is not unique, but it is novel in its frequency, having been mentioned by all focus groups in this study. The prevalence of this group potentially reflects the high levels of extracurricular engagement of college-bound youth. Given these groups may be reflected in, and reinforced by, popular culture (e.g., Glee, High School Musical), probing their existence and descriptions would be valuable in future samples, including replicating our design with other groups of young adults (e.g., those attending community colleges, private four-year colleges, or directly entering the labor market) or using traditional designs with current high school students but talking with college-and non-college-bound students separately.

Our study also explored how a college-bound sample differentiates out-group conventional and counterculture groups. Many crowds and their characteristics were consistent with prior studies, in their location on the social hierarchy, appearance, and activities but updated to contemporary times. Our sample placed the conventional crowds above the counterculture crowds in the social hierarchy, not surprising given that conventional activities aligned with school values and increased chances of college acceptance. Jocks and Populars held their place at the top of the social hierarchy, even in our college sample. Consistent with some prior research, the Druggie/Stoner crowd sat in a middle position, as they were described as supplying drugs to the higher status crowds. We encourage future studies to continue to probe in-and out-group perspectives, especially of Druggie/Stoners, given that our results are consistent with some prior studies (Kinney, 1993) but not all (Garner et al., 2006; Schwartz et al., 2017), and in light of declining trends in drug use among teenagers in recent years (Johnston et al., 2018).

Focus group participants identified that some students, such as Normals and Loners, did not benefit from extracurricular opportunities (Mahoney, Harris, & Eccles, 2006; U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Other crowds were centered around non-school based interests related to fringe media and technology, however these interests were rewarded at school less. Anime/Mangas demonstrated a unique attribute of the current historical moment, finding niche hobbies outside of their schools that connected them to other cultures via social media and video games. Similarly, Emo/Goths embraced oppositional musical genres, which are widely accessible through streaming platforms like YouTube or Spotify, and whose themes are discussed on blogs and online forums. These findings reinforce the importance of scholars continuing to evaluate the role of technology, popular culture, and fringe culture on peer crowds.

The continued racial-ethnic diversification of the U.S. student population was also revealed in complex ways as focus group participants described racial-ethnic crowds. The difference in White participants’ and participants’ of color descriptions of racial-ethnic groups suggests another way that students may experience peer crowds differently based on in-group and out-group identity. White focus group participants defined monolithic racial-ethnic crowds, while participants of color noted diversity. When students of color described racially-ethnically specific peer crowds, they identified them as sources of familiarity within predominantly White spaces. Future research should examine whether these results replicate in other samples, how crowds, their names, and their characteristics differ between in-and out-groups, and continue understanding the ways certain crowds remain mired in racial-ethnic stereotypes.

Our adaptation of Brown’s Social Type Rating process offers a new way for researchers to understand peer crowds. By bringing together college students, we gained insight from a variety of high schools while potentially creating an open space to discuss peer crowds, as students were no longer in the high school environment. At the same time, our study has several limitations. First, our focus on the college-bound segment of the high school landscape means that our results do not generalize to all high schoolers. Our sample of students at two large public universities means our slice of the college-bound population is limited and may not generalize to students at other universities, particularly those in other regions of the U.S. Retrospective reports about high school crowds may also differ from contemporaneous reports. Second, the group dynamic of focus groups may privilege the perspectives of participants who vocalized their thoughts more than others, even though moderators were trained to encourage robust participation. Individuals may have agreed with the group consensus or failed to share contradictory thoughts. Although participants first wrote down thoughts individually before discussing with the group and our moderators attempted to draw out divergent perspectives, we may have over or underemphasized themes to the extent that students felt social pressure to follow group consensus.

In sum, we conducted focus groups with a diverse set of college students at two universities to understand the peer crowds they perceived as recent college-bound high schoolers. Participants offered some novel insight, but also continuities in relation to past literature. Future research can build on these findings by intensively examining peer crowds from the unique vantage point of other segments of the high school and young adult populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under award number R01HD081022. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Rowena Crabbe, Virginia Tech.

Lilla K. Pivnick, University of Texas at Austin

Julia Bates, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Rachel A. Gordon, University of Illinois at Chicago

Robert Crosnoe, University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Adderley C, Kennedy M, & Berz W (2003). “A home away from home”: The world of the high school music classroom. Journal of Research in Music Education, 51(3), 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ansay SJ, Perkins DF, & Nelson CJ (2004). Interpreting outcomes: Using focus groups in evaluation research. Family Relations, 53(3), 310–16. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J (1991). Heavy metal music and reckless behavior among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 20(6), 573–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BL, Eccles JS, & Stone MR (2001). Whatever happened to the jock, the brain, and the princess? Young adult pathways linked to adolescent activity involvement and social identity. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16(5), 429–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E, & Forman TA (2000). “I am not a racist but…”: Mapping white college students’ racial ideology in the USA. Discourse & Society, 11(1), 50–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, Hershbein B, & Long BT (2009). Playing the admissions game: Student reactions to increasing college competition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 119–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB (1989). The role of peer groups in adolescents’ adjustment to secondary school. In Berndt TJ & Ladd GW (Eds.), Peer relationships in child development (1st ed.). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Herman M, Hamm JV, & Heck DJ (2008). Ethnicity and image: Correlates of crowd affiliation among ethnic minority youth. Child Development, 79(3), 529–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Larson J (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In Lerner R& Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Lohr MJ (1987). Peer-group affiliation and adolescent self-esteem: An integration of ego-identity and symbolic-interaction theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, & Steinberg L (1993). Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development, 64(2), 467–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt R (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. American Journal of Sociology, 110(2), 349–99. [Google Scholar]

- Clasens DR, & Brown BB (1985). The multidimensionality of peer-pressure in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14(6), 451–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS (1961). The adolescent society: The social life of the teenager and its impact on education. Glencoe, IL: Free Press of Glencoe. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci E (2007). “Focus groups can be fun”: The use of activity-oriented questions in focus group discussions. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2011). Fitting in, standing out: Navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education (1st ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cusick PA (1973). Inside high school: The student’s world. New York, NY: Hold, Rinehard, and Winston, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth S (2004). Understanding the delinquency and social relationships of loners. Youth & Society, 35(3), 366–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, & Adler NE (1994). Perceived competencies, peer group affiliation, and risk behavior among early adolescents. Health Psychology, 13(6), 496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornwaard SM, Branje S, Meeus W, & ter Bogt T (2012). Development of adolescents’ peer crowd identification in relation to changes in problem behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1366–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin DL, Darling N, Steinberg L, & Brown BB (1993). Parenting style and peer group membership among European-American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 3(1), 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Barber BL (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(1), 10–43. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert P (1989). Jocks and burnouts: Social categories and identity in the high school. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garner R, Bootcheck J, Lorr M, & Rauch K (2006). The adolescent society revisited: Cultures, crowds, climates, and status structures in seven secondary schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(6), 1023–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C, & Katz LF (2009). The future of inequality: The other reason education matters so much. Aspen Institute Congressional Program, 24(4): 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum TL (2000). Moderating focus groups: A practical guide for group facilitation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Halcomb EJ, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, & Davidson PM (2007). Literature review: Considerations in undertaking focus group research with culturally and linguistically diverse groups. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(6), 1000–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JA (2004). The social contexts of focus groups. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 33(5), 602–37. [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS (2003). Adolescents’ reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyden LC, & Bülow PH (2003). Who’s talking: Drawing conclusions from focus groups—some methodological considerations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(4), 305–21. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Blumler JG, & Gurevitch M (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In Blumer JG, and Katz e. (eds) The Use of Mass Communications. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, & Gabler J (2004). Cultural capital and the extracurricular activities of girls and boys in the college attainment process. Poetics, 32(2), 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney DA (1993). From nerds to normals: The recovery of identity among adolescents from middle school to high school. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J (1994). The methodology of focus groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health & Illness, 16(1), 103–21. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, & Casey MA (2000). Focus groups. A practical guide for applied research, 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin R (1979). Suburban youth in cultural crisis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YO, Jordan JW, Djakaria M, & Ling PM (2014). Using peer crowds to segment Black youth for smoking intervention. Health Promotion Practice, 15(4), 530–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemann N (2000). The big test: The secret history of American meritocracy. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Massey OT (2011). A proposed model for the analysis and interpretation of focus groups in evaluation research. Evaluation and Program Planning, 34(1), 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JL, Harris AL, & Eccles JS (2006). Organized activity participation, positive youth development, and the over-scheduling hypothesis. SRCD Social Policy Report. (Vol. 20). Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED521752. [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bianchi ME (1986). Ethnic identities and patterns of school success and failure among Mexican-descent and Japanese-American students in a California high school: An ethnographic analysis. American Journal of Education, 95(1), 233–55. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland J, Hussar B, Wang X, Zhang J, Wang K, Rathbun A, Barmer A, Forrest Cataldi E, and Bullock Mann F (2018). The Condition of Education 2018. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Hoffman JH, Barnes GM, Farrell MP, Sabo D, & Melnick MJ (2003). Jocks, gender, race, and adolescent. Journal of Drug Education, 33(4), 445–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner M (2006). Freaks, geeks, and cool kids: American teenagers, schools, and the culture of consumption (1st ed.). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moran MB, Murphy ST, & Sussman S (2012). Campaigns and cliques: Variations in effectiveness of an antismoking campaign as a function of adolescent peer group identity. Journal of Health Communication, 17(10), 1215–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MB, Walker MW, Alexander TN, Jordan JW, & Wagner DE (2017). Why peer crowds matter: Incorporating youth subcultures and values in health education campaigns. American Journal of Public Health, 107(3), 389–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL, & Krueger A (1993). When to use focus groups and why. In Morgan DL (Ed.), Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ (2001). The School Ensemble: A Culture of Our Own. Music Educators Journal, 88(2), 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols JD, & White J (2001). Impact of peer networks on achievement of high school algebra students. The Journal of Educational Research, 94(5), 267–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J, & Brown BB (2010). Making meanings, meaning identity: Hmong adolescent perceptions and use of language and style as identity symbols. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(4), 849–68. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, & Asher SR (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102(3), 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipov M (2010). ‘Generic misery music’? Emo and the problem of contemporary youth culture. Media International Australia, 136(1), 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke K, & Dang T (2003). “FOB” and “whitewashed”: Identity and internalized racism among second generation Asian Americans. Qualitative Sociology, 26(2), 147–72. [Google Scholar]

- Randall ET, Bohnert AM, & Travers LV (2015). Understanding affluent adolescent adjustment: The interplay of parental perfectionism, perceived parental pressure, and organized activity involvement. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riester AE, & Zucker RA (1968). Adolescent social structure and drinking behavior. Journal of Counseling & Development, 47(4), 304–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rigsby LC, & McDill EL (1972). Adolescent peer influence processes: Conceptualization and measurement. Social Science Research, 1(3), 305–21. [Google Scholar]

- Roe K (1995). Adolescents’ use of socially disvalued media: Towards a theory of media delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 24(5), 617–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M, & Badea C (2007). Why do people perceive in-group homogeneity on in-group traits and out-group homogeneity on out-group traits? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(1), 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Bukowski WM, Parker JG, & Bowker JC (2008). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In Damon W, Lerner RM, Kuhn D, Siegler RS, & Eisenberg N (Eds.), Child and Adolescent Development: An Advanced Course (pp. 141–71). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CS, Hunt JS, Weible JA, Peterson CR, & Casas JF (2007). Multicultural and colorblind ideology, stereotypes, and ethnocentrism among Black and White Americans. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(4), 617–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Hopmeyer A, Luo T, Ross A, Fischer J (2017). Affiliation with antisocial crowds and psychosocial outcomes in a gang-impacted urban middle school. Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(4), 559–586. [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout MH, Branje SJ, ter Bogt TF, & Meeus WH (2009). The role of music preferences in early adolescents’ friendship formation and stability. Journal of Adolescence, 32(1), 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim TN, & Yeo GH (2012). Peer crowds in Singapore. Youth and Society, 44(2), 201–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Ashmore RD, & Brown BB (2007). Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 32(8), 1602–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson CB (2002). Spending time or investing time? Involvement in high school curricular and extracurricular activities as strategic action. Rationality and Society, 14(4), 431–471. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Fry R, & Oates R (2014). The rising cost of not going to college. Pew Research. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda M (2013). Diversity≠ inclusion: Promoting integration in higher education. Educational Researcher, 42(9), 467–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Değirmencioğlu SM, Tolson JM, & Halliday-Scher K (2000). Adolescent social crowds: Measurement and relationship to friendships. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(4), 427–45. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2014). Nearly 6 out of 10 children participate in extracurricular activities (Census Bureau Reports). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Common Core of Data (CCD). Retrieved July 12, 2017, from https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/pubschuniv.asp

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.