Abstract

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) express a need for additional psychotherapy; however, psychological support is not incorporated in the routine care of persons with IBD. This systematic review aims to assess the effect of psychotherapy on quality of life (QoL).

Methods

A systematic search was conducted on October 7, 2019, using Embase, Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar to collect all types of clinical trials with psychotherapeutic interventions that measured QoL in patients with IBD aged ≥18 years. Quality of evidence was systematically assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation criteria.

Results

Out of 2560 articles, 31 studies (32 articles) were included with a total number of 2397 patients with active and inactive IBD. Of the 31 eligible studies, 11 reported a significant positive effect and 6 had ambiguous results regarding the impact of psychotherapeutic interventions on QoL. Treatment modalities differed in the reported studies and consisted of cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, stress management programs, mindfulness, hypnosis, or solution-focused therapy. All 4 studies focusing on patients with active disease reported a positive effect of psychotherapy. Trials applying cognitive-behavioral therapy reported the most consistent positive results.

Conclusions

Psychotherapeutic interventions can improve QoL in patients with IBD. More high-quality research is needed before psychological therapy may be implemented in daily IBD practice and to evaluate whether early psychological intervention after diagnosis will result in better coping strategies and QoL throughout life.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, psychotherapy, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of anxiety and mood disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is high, and the prevalence of these disorders is increased compared with the general population.1-3 Factors influencing this emotional distress include loss of bowel control, feeling unclean, fatigue, impairment of body image, and social isolation.4 Previous research has underlined that anxiety and depression are higher during active disease compared to inactive disease, and quality of life (QoL) scores seem lower especially during a flare.5, 6 This psychological load adds to the physical burden of the disease and is associated with direct and indirect costs.7

Two studies showed that 30% to 50% of patients with IBD express a need for additional psychotherapy and that this need is associated with reduced QoL.8, 9 Screening patients with IBD for mood disorders has recently been shown to offer mental health benefits.10 However, psychological support is not routinely provided to people with IBD in outpatient settings, and no long-term evidence is available on the effect of providing this support to all patients with IBD directly after diagnosis to educate patients on coping strategies to manage their disease during life.7, 10 Even more important is to better estimate the effect of psychotherapy on QoL before implementing it in daily clinical practice.

To analyze the burden of IBD on a patient’s life and to determine the impact of psychotherapy, different outcome measures are used. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional measure that reflects the impact of IBD on a person’s physical and mental health and social functioning.4 This patient-reported outcome measure is an important endpoint in clinical trials according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicine Agency.11

Psychotherapy may affect QoL positively; however, most of the available systematic reviews and trials have focused on well-being in general and not specifically on QoL,12, 13 investigated different psychoeducational interventions,14 focused mainly on randomized controlled trials (RCTs),14, 15 investigated the effect on children as well,16 or were considered outdated.13, 16

The aim of this systematic literature review was to determine the effect of psychotherapy on the QoL of adult patients with IBD, regardless of study design or treatment modality, to enable the evaluation of the effect of every applied intervention.

METHODS

Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they (1) reported QoL as an outcome measure, (2) used a psychotherapeutic intervention, (3) included patients with IBD, (4) patients were aged ≥18 years, and (5) were written in English. All clinical trials meeting the inclusion criteria were considered for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria

Protocols, abstracts, and studies applying educational interventions only were excluded.

Systematic Search

A systematic search was conducted in the online databases: Embase, Medline (Ovid), PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar (100 top ranked) on October 7, 2019. The search strategy was made for Embase and adapted for the other databases. Reference lists were also searched to identify additional relevant studies. Details of the Embase search terms are shown in Supplementary Data 1.

Study Selection

The study selection was performed by I.B. (medical student) and E.P. (MD, PhD candidate) and checked by K.dB. (MD, PhD).

Quality Assessment

The quality of the evidence, including the risk of bias, of every included article was manually assessed by applying the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.17 Every study was graded from very low, low, moderate to high, and high, with high being the highest quality of evidence. Assessments were performed by the 2 primary reviewers (I.B. and E.P.).

Statistical Analysis

When possible, total scores of validated questionnaires were used to evaluate the effect of the intervention in the population. When a study used 2 questionnaires of which 1 showed significant improvements after the intervention, the overall effect was considered positive. When a questionnaire consisted of different domains and no total score could be obtained, the effect per domain was evaluated and results were considered mixed when not all domains showed improvement. Results were described with respective P values if available or when possible to calculate, with P < 0.05 being statistically significant. Means were provided for studies that were described in more detail.

RESULTS

Description of Included Studies

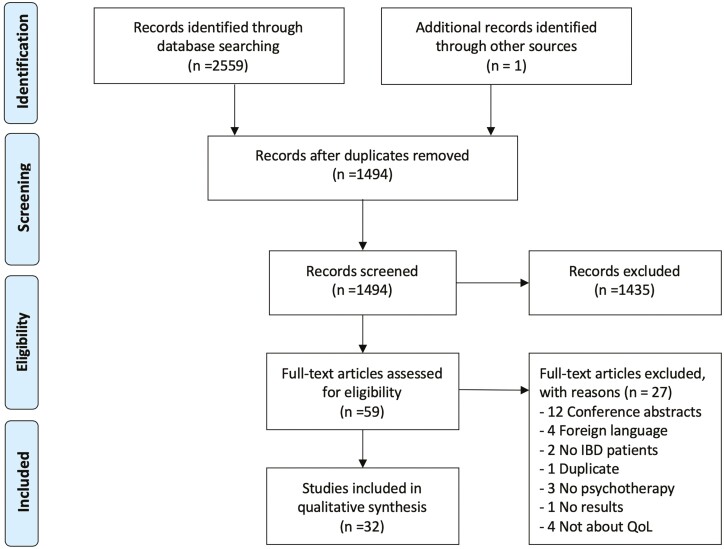

The literature search identified 2560 studies, of which 1494 remained after deduplication. There were 799 from Embase, 65 from Medline (Ovid), 108 from Cochrane, 331 from PsycInfo, 168 from Web of Science, 22 from Google Scholar, and 1 from reference list searching. After screening titles and abstracts, 59 were further assessed for eligibility. A total of 31 studies (32 articles) were included in the systematic review, with reasons for exclusion specified in Fig. 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of selection process.

Research Designs

Sample size

A total of 2397 patients with IBD were analyzed in the 31 studies included, of whom 1446 patients were included in the intervention group.

Outcome

Applied health-related QoL questionnaires are listed in Table 1. Fifty-five percent of studies used the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ),18-34 13% used its short version,35-38 and 1 study used the Spanish version.39 Twenty-three percent used the short-form health survey-36 (SF-36)19, 20, 23, 24, 30, 38, 40 and 10% used the short version of the SF-36.22, 25, 41 Other studies used the HRQL,42 the Assessment of Quality of Life-8D,10 the EuroQol Five Dimensions Health Questionnaire,23, 33 the German Quality-of-Life Questionnaire,43 the World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF,44 the Short Health Scale,45 or the 15D questionnaire.46 One study did not use a questionnaire but instead asked a multiple-choice question.47 All questionnaires but 1 were validated; for the German Quality-of-Life Questionnaire, evidence of validation was lacking.48

TABLE 1.

Applied Health-Related QoL Questionnaires

| Year | Instrument | Full Title | Condition | Main Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | IBDQ55 | Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | IBD | 32 questions on a 5-point Likert scale Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1999 | SIBDQ56 | Spanish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | IBD | 36 questions on a 5-point Likert scale Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1996 | sIBDQ57 | Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | IBD | 10 questions on a 5-point Likert scale Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1992 | SF-3658 | 36-item short-form health survey | Generic | 36 items with 2-6 answer options Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1996 | SF-1259 | 12-item short-form health survey | Generic | 12 items with 2-6 answer options Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1989 | QL48 | German Quality-of-Life questionnaire | Generic | 21 items Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1998 | WHOQoL-BREF60, 61 | World Health Organization–Quality of Life BREF | Generic | 26 items on a 5-point Likert scale Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 2006 | SHS62 | Short Health Scale | IBD | 4 items on a 100 mm visual analog scale Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 2001 | 15D questionnaire63 | 15D questionnaire | Generic | 15 questions scored on 5 ordinal levels Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 2014 | AQoL-8D64 | Assessment of Quality of Life-8D | Generic | 35 items scored on 4-5 ordinal levels Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

| 1990 | EQ-5D65 | EuroQol Five Dimensions Health Questionnaire | Generic | 14 questions scored on nominal and ordinal levels Higher scores implicate higher QoL |

Type of study

Concerning methodology, 23 studies were RCTs18-26, 28, 31, 32, 36, 39–43, 45 of whom 4 were pilot RCTs.27, 33, 34, 38 One study was partially randomized,30 6 studies were prospective observational studies,10, 29, 35, 37, 46, 47 and 1 prospective observational study used a control group.44

Quality according to GRADE criteria

No studies were graded as being of high quality. Eight studies were of moderate quality,18, 19, 21-23, 36, 41, 45 8 studies were of low quality,24, 25, 28, 32, 39, 40, 42, 43 and 15 studies were assessed as being of very low quality,10, 20, 26, 27, 29-31, 33-35, 37, 38, 44, 46, 47 according to the GRADE criteria.17

Main Findings of Effect of Psychotherapy

The 31 eligible studies are displayed in Table 2. Ten showed a significant positive effect regarding the impact of psychotherapeutic interventions on QoL,10, 18, 19, 23, 26, 31, 34, 36, 37, 46 and 1 study only reported raw data but showed, after statistical testing, a significant effect.47 Six studies reported mixed results;21, 25, 28, 30, 44, 39 1 study showed significant improvements in QoL scores in the intervention group but no significant difference compared with the control group,39 2 studies displayed significant effects in the per-protocol analysis but not in the intention-to-treat analysis,25, 28 2 studies reported improvement in only some domains,30, 44 and 2 studies concluded that improvements were only witnessed in a subgroup.21, 28 Thirteen studies were not able to show a significant effect from psychotherapy.20, 22, 24, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35, 40–43, 45 One study did not perform statistical testing because of a pilot setting and small sample size but did show a positive trend.38 Of the 8 studies that were rated as being of moderate quality, half showed a significant positive effect and are discussed in more detail in Supplementary Data 2.

TABLE 2.

Study Characteristics and Outcome Data of Included Studies

| Author (year) | Study Type | Quality of Evidence | Study Population | Dropout | Experimental Conditions | Instrument | Methods | Follow-Up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bennebroek Evertsz et al 2017 19 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 59 intervention group; n = 59 control group |

25.4%; 30.5% |

IBD patients with poor mental QoL | IBDQ, SF-36 | Eight 1-hr wkly sessions of IBD-specific CBT vs WLC | 1 and 3.5 mo | Significantly greater improvement in IBDQ and SF-36 mental score after 3.5 mo compared with control group (P < 0.01) |

| Berding et al 2017 41 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 105 intervention group; n = 102 control group |

20%; 6.9% |

IBD patients | SF-12 | 2 d group sessions of self-management patient education program with medical information and coping and self-management skills vs WLC | 3 mo | No significant difference between both groups regarding physical (P = 0.54) or mental (P = 0.18) HRQoL |

| Boye et al 2011 18 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 57 intervention group; n = 57 control group |

21.1%; 19.3% |

IBD patients with high chronic distress (PSQ ≥ 60) | IBDQ | Three 3 h group sessions psychoeducation in combination with CBT and 6-9 individual wkly CBT sessions with booster sessions at follow-up, at-home assignments of relaxation training and behavioral adjustments vs TAU | 6, 12, 18 mo | QoL improved from baseline to 18 mo in intervention group (P = 0.009). Significant differences only found in UC group, not in CD group. |

| Hunt et al 2019 36 | Parallel RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 70 intervention group; n = 70 control group |

41.4%; 51.4% |

IBD patients | sIBDQ | Self-help IBD-specified CBT workbook vs psychoeducational workbook | Wk 6, 3 mo | Significant improvement in sIBDQ score in intervention group from baseline to wk 6 (P < 0.01) and 3 mo (P < 0.05) and significant compared with control group at wk 6 (P < 0.05). QoL remained significantly improved compared with control group during flare. |

| Jedel et al 2014 21 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 27 intervention group; n = 28 control group |

3.7%; 3.6% |

UC patients in remission | IBDQ | MBSR program, 8 wkly 2.5 h group sessions, 6 d/week 45 min computer sessions vs. same time/attention mind-body medicine | Wk 8, 6 and 12 mo | No significant difference between intervention and control groups in 12 mo total IBDQ score (P = 0.07). Significantly better IBDQ total scores in intervention group with flare compared to control flare patients at 12 mo (P = 0.001). |

| Keefer et al 2013 22 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 26 intervention group; n = 29 control group |

11.5%; 3.4% |

UC patients in remission | IBDQ + SF-12 version 2 | 7 wkly 40 min gut-directed hypnotherapy sessions, home practice via audio hypnosis 5 times/wk vs education about mind-body connection | 8, 20, 36, 52 wk | Nonsignificant improvement in IBDQ scores in intervention group at 1 y compared to baseline and compared to attention control (control group that receives the same attention but no other elements of intervention)(P < 0.05). |

| Vogelaar et al 2014 23 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 49 intervention group; n = 49 control group |

2.04%; 0% |

IBD patients in remission with severe fatigue (CIS-fatigue ≥ 35) | IBDQ + SF-36 + EQ-5D | Six 1.5 h SFT plus psychoeducation sessions in first 3 mo, 1 booster session at 6 mo vs TAU | 3, 6, 9 mo | SFT was associated with significantly higher mean IBDQ total score compared with control group at 3 mo (P = 0.02), but effect declined at 6 (P = 0.241) and 9 months (P = 0.635). SF-36 scores not significantly improved. |

| Wynne et al 2019 45 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ | n = 61 intervention group; n = 61 control group |

39.3%; 31.1% |

IBD patients with psychosocial dysfunction plus inactive/stable mild disease | SHS | Eight 90 min wkly group sessions of ACT vs TAU | 8, 20 wk | No total scores reported. In PP only general well-being increased compared with control group, but not in ITT, and no evidential increase in other domains. |

| Berill et al 2014 28 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 33 intervention group; n = 33 control group |

45.5%; 51.5% |

IBD patients in remission with IBS symptoms or high stress levels | IBDQ | Six 40 min face-to-face multiconvergent mindfulness-based therapy vs TAU | 4, 8, 12 mo | PP analysis significant at 4 mo only (P = 0.038). No significant difference in improvement in IBDQ scores between groups at follow-up (all P > 0.05). IBS-type subgroup had higher IBDQ scores at 4 mo compared to control subgroup (P = 0.038). |

| Deter et al 2007 42 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 71 intervention group; n = 37 control group |

39.4%; 29.7% |

CD | HRQL | 20 h psychodynamic psychotherapy plus 10 autogenic training session relaxation treatment program, maximum of 1 year vs TAU | 12, 18, 24 mo | No significant changes in HRQoL between intervention and control groups. |

| Diaz-Sibaja et al 2009 39 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 33 intervention group; n = 24 control group |

45.5%; 41.7% |

IBD patients in remission | Spanish IBDQ | 10 wkly 2 h group sessions focused on coping, problem-solving, relaxation, and cognitive restructuring techniques vs. WLC | 10 wk; 3, 6, 12 mo | IBDQ scores of intervention group significantly improved at wk 10 and 3 mo (P < 0.01) but not at 6 mo (P = 0.20) and 12 mo (P = 0.06). No significant difference between mean scores of both groups pre- and posttreatment. |

| Keller et al 2004 43 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 71 intervention group n = 37 control group |

26.8%; 21.6% |

CD patients | QL | ≥10 individual/group verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy sessions (50-100 min) and ≥10 relaxation sessions (maximum 1 y) vs TAU | 12 mo, 24 mo | No evidential differences in QoL between or in-between groups found. |

| Langhorst et al 2007 24 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 30 intervention group; n = 30 control group |

0% 13.3% |

UC patients | IBDQ plus SF-36 | 60 h lifestyle modification program over 10 wk consisting of exercise, relaxation techniques, CBT, psychoeducation group therapy, and Mediterranean-type diet vs TAU | 3, 12 mo | No significant effect at 3 and 12 mo for IBDQ scales. At 3 mo only physical function scale had significantly improved (P = 0.0175), but after 12 mo no significant differences between groups. |

| McCombie et al 2016 25 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 131 intervention group n = 100 control group |

59.5%; 34.0% |

IBD patients | IBDQ plus SF-12 | 8 wk computerized CBT, 8 sessions vs TAU | 12 wk, 6 mo | ITT analysis showed no increase in IBDQ scores at 12 wk (P = 0.44) and 6 mo (P = 0.50); no increase in SF-12 mental and physical scores all P > 0.05. PP analysis showed greater increase in mean IBDQ score than in control patients (P = 0.01). Improvement in SF-12 mental scores significant at wk 12 (P = 0.03) but not SF-12 physical scores (P = 0.20). |

| Mikocka-Walus et al 2015 40 ; Mikocka-Walus et al 2017 49 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 92 intervention group; n = 84 control group |

65.2%; 46.4%; (at 24 months) |

IBD patients in remission or with mild disease | SF-36 | 10 wkly 2 h group sessions CBT (either face-to-face or online CBT) vs TAU | 6, 12, 24 mo | Significant improvement in mental QoL over 12 mo in CBT group in univariate analysis (P = 0.013) but at multivariate level no significant effect at 12 and 24 mo (P > 0.5). |

| Oxelmark et al 2007 32 | RCT | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ | n = 24 intervention group; n = 20 control group |

25%; 25% |

IBD patients in remission or with mild disease | IBDQ | Nine wkly 1.5 h group psychotherapy sessions focused on coping, stress management, diet, and lectures about IBD vs TAU | 6, 12 mo | No significant difference in IBDQ scores at 6 and 12 mo compared to baseline and between both groups. |

| Elsenbruch et al 2005 30 | Partial RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 15 intervention group; n = 15 control group |

6.7%; 0% |

UC patients in remission or with low disease activity | IBDQ + SF-36 | 10 wkly 6 h program mind-body therapy (stress management, diet, exercise, cognitive-behavioral techniques) vs WLC | 10 wk | No significant difference in improvement between groups for IBDQ total scores. The intervention group showed greater improvements in SF-36 Psychological Health Sum score (P < 0.05). |

| Gerbarg et al 2015 31 | RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 16 intervention group; n = 13 control group |

12.5%; 15.4% |

IBD patients | IBDQ | 2 d 9 h total breath, body, and mind workshop, daily 20 min breathing exercises with follow-up session vs 9 h educational seminar and educational lectures | 6, 26 wk | Significant improvement in IBDQ mean scores at wk 6 and 26 (both P = 0.01), significant improvement compared with control group at week 26 (P = 0.04). |

| Haapamäki et al 2018 46 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 142 intervention | 37.3% | IBD patients | 15D questionnaire | 10-12 d of group adaptation courses (lectures, exercise, relaxation, social, individual consult) divided into 2 periods separated by 4-6 mo | 12 d, 6, 12 mo | Significant increase in HRQoL at all time points (all P < 0.001). |

| Hou et al 2017 35 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 21 | 14.3% | IBD patients with co-occurring anxiety or depression | sIBDQ | 1 d (5 h) ACT plus IBD education group workshop | 3 mo | No significant improvement in sIBDQ scores (P = 0.08). |

| Jordan et al 2019 37 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 28 | 3.6% | IBD patients in remission or with mild disease with moderate to severe symptoms of anxiety and/or low mood | sIBDQ | 4-10 (mode 6) wkly 50 min sessions of CBT | 4-10 wk | Significant increase in sIBDQ scores compared to baseline (P < 0.001). |

| Keefer et al 2012 34 | Pilot RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 16 intervention group; n = 12 control group |

7.1% | CD patients in remission | IBDQ | 6 wkly 60 min sessions of “project management” based on cognitive-behavioral principles of health behavior change and social learning theory vs TAU |

6 wk | PP analysis showed more improvement in intervention group on IBDQ total score (P = 0.001). |

| Larsson et al 2003 20 | RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 49 intervention group; n = 17 control group |

46.9% | IBD patients with anxiety and depression (scored by HADS) | SF-36 + IBDQ | 8 sessions group-based patient education with information about IBD, nutrition, diet, stress management, adaptation, and coping strategies vs WLC |

6 mo | No significant difference in PP within-group analysis at follow-up for both questionnaires. |

| Lores et al 2019 10 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 91 | 22.0% | IBD patients with mental health issues (scored by HADS) | AQoL-8D | In-service or external CBT and ACT vs decliners (patients who scored above clinical cut-off scores on the mental health questionnaires but who declined psychological treatment) | 12 mo | Significant increase in HRQoL in intervention group from baseline (P < 0.001) and compared with decliners (P < 0.05). |

| Maunder and Esplen 2001 29 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 30 | 36.7% | IBD patients | IBDQ | 20 wkly 90 min supportive-expressive group therapy sessions | 20 weeks | PP analysis showed nonsignificant improvement in IBDQ score (P = 0.35). |

| Miller and Whorwell 2008 47 | Prospective observational study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 15 | 0% | IBD patients with refractory disease | Multiple choice question | 12 sessions of gut-focused hypnosis plus audio practice at home | 2 to 16 years (mean = 5.4 years) | At baseline 6.67% good/excellent QoL, after hypnotherapy 80% (calculated P = 0.003). |

| Mizrahi et al 2012 26 | RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 28 intervention group; n = 28 control group |

35.7%; 25.0% |

IBD patients with active disease | IBDQ | 5 wk individual 50 min relaxation training with guided imagery at 2 wk intervals, daily 15 min relaxation exercises at home vs WLC |

5 weeks | PP analysis showed significant difference in effect of intervention over time (P = 0.014) and within-patient improvements (P = 0.002) on general IBDQ scores. |

| Neilson et al 2016 44 | Non-RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 33 intervention group; n = 27 control group |

15.2%; 11.1% |

IBD patients | WHOQoL-BREF | 8 wkly 2.5 h and one 7 h mindfulness group session, 45 min daily home exercises vs TAU | 8 weeks, 32 weeks |

At wk 8, significantly greater improvements in intervention group compared with control group but only in psychological health (P < 0.01) and physical health (P < 0.01). At wk 32, no significant differences. |

| O’Connor et al 2019 38 | Pilot RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 10 intervention group; n = 13 control group |

0% | IBD patients in remission who reported fatigue | SF-36 + sIBDQ | 3 small-group 1 h psychoeducational sessions focusing on fatigue every 8 wk for 6 mon vs TAU | 6 months | SF-general health and SIBDQ greater improvement in intervention arm (no P stated). |

| Schoultz et al 2015 27 | Pilot RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 22 intervention group; n = 22 control group |

40.9%; 45.5% |

IBD patients | (adapted) IBDQ | 8 wkly 2 h group sessions on mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and 45 min home practice 6 d/wk vs IBD leaflet | 8 weeks, 6 months | No significant interaction between mindfulness-based cognitive therapy group and time on QoL scores (P = 0.437). |

| Vogelaar et al 2011 33 | Pilot RCT | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ | n = 9 PST group; n = 8 SFT group; n = 12 control group |

44.4%; 12.5%; 8.3% |

CD patients with high fatigue scores (CIS-fatigue > 35) but no depression (HADS < 10) | IBDQ + EQ-5D | 10 sessions PST in 3 mo vs 5 sessions SFT in 3 mo vs TAU | 6 months | No significant differences in EQ-5D and IBDQ total scores between intervention group and control group. |

ACT indicates acceptance and commitment therapy; CIS, checklist individual strength; EQ-5D, EuroQol Five Dimensions Health Questionnaire; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; ITT, intention to treat; MBSR, mindfulness-based stress reduction; n, population number; PP, per protocol; PSQ, perceived stress questionnaire; PST, problem-solving therapy; QL, German Quality-of-Life questionnaire; SFT, solution-focused therapy; SHS, Short Health Scale; sIBDQ, short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; SIBDQ: Spanish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; TAU, treatment as usual; WHOQoL-BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF; WLC, waitlist control patient.

+/–: corresponds with level of evidence.

IBD phenotype

Seven studies focused solely on ulcerative colitis (UC) patients21, 22, 24, 30 or published data on both UC and Crohn disease (CD) groups separately.18, 28, 32 In patients with UC, 3 studies found no significant effect22, 24, 32 and 3 described mixed results.21, 28, 30 One study reported a positive effect in UC patients only, with a mean difference in IBDQ total score of 28.9 (30.2) at an 18-month follow-up that was significantly different from that of the control group.18 Seven studies reported on patients with CD, of which 4 included CD patients only.33, 34, 42, 43 Only 1 study with CD patients observed significant improvement in QoL, with improved IBDQ total scores at week 6 (mean score from 153.8 [22.5] to 171 [18.1]; P = 0.001) and in comparison with the control group.34

Disease activity

Thirteen studies included IBD patients in remission or with very mild disease only, or described results when disease worsened: The overall effect reported on patients in remission was ambiguous, with 4 studies reporting a (temporarily) positive effect,23, 34, 36, 37 5 studies reporting no significant effect,21, 22, 32, 40, 45, 49 3 studies reporting mixed results,28, 30, 39 and 1 study that did not perform statistical testing because of the small sample size.38 Four studies focused on IBD patients with active disease only26, 47 or described the impact of psychotherapy during a flare,21, 36 and these 4 studies showed a significant positive effect of psychotherapy on QoL. Mizrahi et al26 showed in an RCT on stress management a significant difference in the effect of intervention over time in IBD patients compared with control patients after 5 weeks (P = 0.014; mean difference in IBDQ total score = 13.33 [15.45]; P = 0.002). In the small observational study of Miller and Whorwell,47 6,7% of the therapy-refractory IBD patients scored their QoL at baseline as good or excellent compared with 80% who scored their QoL similarly after hypnotherapy (calculated P = 0.003), with a mean follow-up of 5.4 years. During a flare, QoL in IBD patients remained significantly improved post-cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) treatment compared with control patients in an RCT conducted by Hunt et al,36 but no measures of the short IBDQ scores were reported. Jedel et al21 observed significantly better IBDQ total scores in patients with active disease in a mindfulness-based stress-reduction program compared with matched control patients at 12 months (mean difference mixed model = 0.15 [0.04-0.26];P = 0.001).

Intervention

All studies used a psychotherapy-based intervention program. Eight studies used mainly CBT,10, 18, 19, 25, 36, 37, 39, 40 4 used psychodynamic interventions,29, 38, 42, 43 and 2 primarily used acceptance and commitment therapy.35, 45 Nine studies used stress management programs as intervention,20, 24, 26, 30-32, 34, 41, 46 4 used mindfulness,21, 27, 28, 44 and 2 used hypnosis.22, 47 Solution-focused therapy was used in 2 studies by the same first author.23, 33

Of the 8 studies focusing on the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behavior through CBT, 5 studies showed significant positive effects,10, 18, 19, 36, 37 2 described mixed results,25, 39 and 1 reported no significant improvement in QoL.40, 49 When a significant effect of therapy was shown, QoL remained improved during the follow-up period, which differed in length from 10 weeks37 to 3.5 months,19 6 months,36 12 months,10 and 18 months, respectively.18

In stress management interventions focusing on relaxation, breathing, and coping, the results were split evenly with 4 studies reporting no significant effect,20, 24, 32, 41 4 studies reporting a positive effect,26, 31, 34, 46 and 1 showing mixed results.30 The significant effect of stress management interventions lasted during follow-up, with times that differed from a short period of 5 weeks26 and 6 weeks34 to 26 weeks31 and 12 months.46

In the mindfulness-based interventions, 3 study showed a mixed result21, 28, 44 and the others showed no significant impact.27 The 2 studies that focused mainly on acceptance and commitment therapy reported no significant results.35, 45 Two studies using hypnosis as intervention showed combined results, with 1 reporting a positive effect47 and one a nonsignificant improvement.22 In the psychodynamic interventions, no significant improvement was observed.29, 38, 42, 43 Solution-focused therapy in a pilot setting resulted in no significant effect,33 but in a larger trial a significant positive effect was reported, which declined during follow-up.23

Psychological condition

In order to be eligible, 12 studies specified that patients needed to have high mental distress,10, 18-20, 35, 37, 45 fatigue,23, 33, 38 or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms28 or they analyzed patients with and without distress separately.40, 49 Of 9 studies including patients with symptoms of anxiety or depression or high distress,10, 18-20, 28, 35, 37, 45, 40, 49 5 studies showed a significant effect.10, 18, 19, 37, 40, 49

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review focusing on QoL that has included all types of psychological approaches regardless of study type. The reviewed publications confirm that psychotherapeutic interventions may have a beneficial effect on the QoL of patients with IBD, but because of the variable results care should be taken when giving advice regarding the implementation of psychotherapy in daily practice. Some IBD patients may benefit more from an intervention than others; all 4 studies focusing on patients with active disease reported a positive effect of psychotherapy on QoL.21, 26, 47, 36 Therefore, psychotherapeutic interventions may be especially useful for IBD patients with (mild) active disease and could be provided in those periods when support is needed most. However, the definition of “active” disease differed among studies, and the effect of medication on QoL was not taken into account. When we assessed different types of interventions, we found that studies focusing on CBT reported the most consistent results, with 5 of 8 studies displaying positive effects.10, 18, 19, 36, 37 However, many interventions combine a variety of therapies, treatment forms, and lifestyle adaptations, making defining the most effective component even more difficult. No specific preference for a type of disease or psychological condition at baseline was found, so these studies did not distinguish between these patient characteristics in the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Overall, these results are in line with previous reviews and a meta-analysis investigating the effect of psychotherapy.12, 14, 15

When comparing the effectiveness of psychotherapy to other chronic autoimmune diseases, some research has found similar results in patients with psoriasis. A meta-analysis of 6 studies including 664 patients with psoriasis reported a significant but small positive effect of psychosocial and psychoeducational therapies on QoL (95% confidence interval, 0.04-0.51).50 For rheumatoid arthritis, a systematic review of reviews of psychological interventions for adults was published, but QoL was not included as an outcome measure in these studies, making it difficult to compare to IBD.51 A recent large RCT did study QoL in fatigued patients with rheumatoid arthritis and concluded that CBT had a beneficial effect on fatigue scores but not on QoL.52

As the primary outcome, QoL was chosen because it is a multidimensional measure that evaluates the impact of IBD on a person’s physical health, mental well-being, and social functioning and is easy to implement in daily practice. However, a limitation of this strategy could be that more specific needs for intervention such as coping and fatigue were underestimated. Psychotherapeutic interventions may facilitate improvements in more specific areas, as emerged from the trial of Berding et al,41 where a significant effect on coping was observed, and from the studies of Wynne et al45 and Vogelaar et al from 2014,23 where they reported positive effects on stress and fatigue, respectively. Therefore, the indication for psychotherapy needs to be carefully chosen to be able to match the intervention to patients and their needs.

Improving QoL is of clinical and social relevance but also of economic importance because patients with a better perceived QoL remain active, can participate in society, and seek less medical help, resulting in less direct and indirect costs. In addition, a recent study from Park et al53 also appointed mental health comorbidities as a crucial key cost driver and showed that costs of patients with mental health diagnoses were almost twice as high as those of patients without mental health issues.

Limitations and Implications

The main limitation of this review was the quality of evidence, with almost half of the studies being graded as very low. The top quartile was of moderate quality, which means that “it is very likely that further research will impact the estimate of the effect,” according to the GRADE criteria.17

No meta-analysis could be performed because of the heterogeneity of the population, design, implementation, and statistical analyses of the studies. More than two-thirds of the studies used the IBDQ and/or the SF-36 or their short versions to measure health-related QoL. As a result, most study outcomes were comparable, but the remaining questionnaires varied enormously. Interventions varied from officially registered CBT to a self-created program with different aspects of stress management and diverse durations. Time of follow-up also differed among studies, with a minimum of 12 days to a maximum of 2 years. The studied populations varied between trials, with patients experiencing high psychological distress at baseline, fatigue or a diagnosis of CD with quiescent disease at inclusion. In other studies patients were excluded for these reasons. Not all studies provided exact summary measures, and some just stated that there may or may not have been an effect of the intervention. Finally, there were diverse methods of handling missing data for patients who dropped out with respect to statistical approaches, which may have led to different conclusions. Therefore, data were not combined in a meta-analysis.

More than half of the studies experienced dropout or lost to follow-up rates of 25% or 62%.19, 20, 25-29, 32, 33, 36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49 Most studies reported that the time-consuming nature of the intervention was the main reason that patients dropped out of the intervention program, which needs to be considered when carrying out future trials or implementation of intervention in daily care/practice. Other reasons given for dropout were disease flares resulting in surgery, pregnancy, long distance to the facility, other expectations of the intervention, and researchers being unable to get in contact with patients at follow-up. As a result, in studies experiencing high dropout rates, different statistical approaches led to different conclusions.

Most studies did not blind participants, therapists, or investigators, thereby introducing a potential bias. Blinding in psychological interventions can be a challenge, but efforts must be made in blinding patients for the hypothesis and investigators when possible as seen in 4 of the included studies.18, 21, 22, 40 Most studies did not control for time and attention conditions, but nonspecific attention can have significant effects on the outcome and should thus be considered.

Future research in this area should thus focus on studies controlled for time and attention, with adequate sample sizes, considering different patient and disease characteristics. To compare interventions with each other as seen in pharmacological studies, researchers can also compare therapies head to head. In addition, whether standard early introduction of psychological care after diagnosis helps patients develop skills to cope with the disease, from which they can benefit throughout life, requires greater attention.

CONCLUSIONS

Psychotherapeutic interventions may improve QoL in IBD patients, but current evidence and efficacy outcomes are too ambiguous. Patients with active disease seem to benefit most from psychotherapy when compared to those in remission. More high-quality research is needed to provide tailored psychological therapy to adults with IBD and to investigate whether (early) intervention after diagnosis will result in better coping strategies and QoL throughout life.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Maarten F.M. Engel from the Erasmus MC Medical Library for developing and updating the search strategies.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

Supported by: C.J. van der Woude received grant support from Falk Benelux and Pfizer; received speaker fees from AbbVie, Takeda, Ferring, Dr. Falk Pharma, Hospira, and Pfizer; and served as a consultant for AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Celgene, Mundipharma, and Janssen. N.K.H. de Boer has served as a speaker for AbbVie and MSD; served as consultant and/or principal investigator for TEVA Pharma BV and Takeda; and received a (unrestricted) research grant from Dr. Falk Pharma, TEVA Pharma BV, and Takeda, all outside the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Walker JR, Ediger JP, Graff LA, et al. . The Manitoba IBD cohort study: a population-based study of the prevalence of lifetime and 12-month anxiety and mood disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Choi K, Chun J, Han K, et al. . Risk of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide, population-based study. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5):654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Byrne G, Rosenfeld G, Leung Y, et al. . Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017(7):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones JL, Nguyen GC, Benchimol EI, et al. . The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: quality of life. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2:S42–S48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leone D, Gilardi D, Corrò BE, et al. . Psychological characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease patients: a comparison between active and nonactive patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:1399–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knowles SR, Keefer L, Wilding H, et al. . Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses-part II. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lores T, Goess C, Mikocka-Walus A, et al. . Integrated psychological care reduces healthcare costs at a hospital-based inflammatory bowel disease service. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020. In press, uncorrected proof. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klag T, Mazurak N, Fantasia L, et al. . High demand for psychotherapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1796–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kutschera M, Waldhör T, Gröchenig HP, et al. . The need for psychological and psychotherapeutic interventions in Austrian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:S308–S309. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lores T, Goess C, Mikocka-Walus A, et al. . Integrated psychological care is needed, welcomed and effective in ambulatory inflammatory bowel disease management: evaluation of a new initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:819–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Guidance for industry 2009. Accessed May 22, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims

- 12. Torres J, Ellul P, Langhorst J, et al. . European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation topical review on complementary medicine and psychotherapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:673–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2704–2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCombie AM, Mulder RT, Gearry RB. Psychotherapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a review and update. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, et al. . Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Timmer A, Preiss JC, Motschall E, et al. . Psychological interventions for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan R, Hill S. How to GRADE the quality of the evidence. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group. December 2016. http://cccrg.cochrane.org/author-resources. Version 3.0.

- 18. Boye B, Lundin KE, Jantschek G, et al. . INSPIRE study: does stress management improve the course of inflammatory bowel disease and disease-specific quality of life in distressed patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease? A randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1863–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bennebroek Evertsz F, Sprangers MAG, Sitnikova K, et al. . Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on quality of life, anxiety, and depressive symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85:918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larsson K, Sundberg Hjelm M, Karlbom U, et al. . A group-based patient education programme for high-anxiety patients with Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jedel S, Hoffman A, Merriman P, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to prevent flare-up in patients with inactive ulcerative colitis. Digestion. 2014;89:142–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keefer L, Taft TH, Kiebles JL, et al. . Gut-directed hypnotherapy significantly augments clinical remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vogelaar L, van’t Spijker A, Timman R, et al. . Fatigue management in patients with IBD: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2014;63:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langhorst J, Mueller T, Luedtke R, et al. . Effects of a comprehensive lifestyle modification program on quality-of-life in patients with ulcerative colitis: a twelve-month follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:734–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCombie A, Gearry R, Andrews J, et al. . Does computerized cognitive behavioral therapy help people with inflammatory bowel disease? A randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mizrahi MC, Reicher-Atir R, Levy S, et al. . Effects of guided imagery with relaxation training on anxiety and quality of life among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Psychol Health. 2012;27:1463–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schoultz M, Atherton I, Watson A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease patients: findings from an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berrill JW, Sadlier M, Hood K, et al. . Mindfulness-based therapy for inflammatory bowel disease patients with functional abdominal symptoms or high perceived stress levels. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:945–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maunder RG, Esplen MJ. Supportive-expressive group psychotherapy for persons with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:622–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elsenbruch S, Langhorst J, Popkirowa K, et al. . Effects of mind-body therapy on quality of life and neuroendocrine and cellular immune functions in patients with ulcerative colitis. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74:277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gerbarg PL, Jacob VE, Stevens L, et al. . The effect of breathing, movement, and meditation on psychological and physical symptoms and inflammatory biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2886–2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oxelmark L, Magnusson A, Löfberg R, et al. . Group-based intervention program in inflammatory bowel disease patients: effects on quality of life. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vogelaar L, Van’t Spijker A, Vogelaar T, et al. . Solution focused therapy: a promising new tool in the management of fatigue in Crohn’s disease patients psychological interventions for the management of fatigue in Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keefer L, Doerfler B, Artz C. Optimizing management of Crohn’s disease within a project management framework: results of a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hou JK, Vanga RR, Thakur E, et al. . One-day behavioral intervention for patients with inflammatory bowel disease and co-occurring psychological distress. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1633–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hunt MG, Loftus P, Accardo M, et al. . Self-help cognitive behavioral therapy improves health-related quality of life for inflammatory bowel disease patients: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jordan C, Hayee B, Chalder T. Cognitive behaviour therapy for distress in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a benchmarking study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2019;26:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O’Connor A, Ratnakumaran R, Warren L, et al. . Randomized controlled trial: a pilot study of a psychoeducational intervention for fatigue in patients with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Díaz-Sibaja M, Moreno M, Hesse B, et al. Protocolized group psychological treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: Its Iipact on quality of life. Psychology in Spain, 2009;13:17-24. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, et al. . Cognitive-behavioural therapy has no effect on disease activity but improves quality of life in subgroups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berding A, Witte C, Gottschald M, et al. . Beneficial effects of education on emotional distress, self-management, and coping in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective randomized controlled study. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2017;1:182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deter HC, Keller W, von Wietersheim J, et al. ; German Study Group on Psychosocial Intervention in Crohn’s Disease . Psychological treatment may reduce the need for healthcare in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Keller W, Pritsch M, Von Wietersheim J, et al. ; German Study Group on Psychosocial Intervention in Crohn’s Disease . Effect of psychotherapy and relaxation on the psychosocial and somatic course of Crohn’s disease: main results of the German Prospective Multicenter Psychotherapy Treatment study on Crohn’s disease. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Neilson K, Ftanou M, Monshat K, et al. . A controlled study of a group mindfulness intervention for individuals living with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wynne B, McHugh L, Gao W, et al. . Acceptance and commitment therapy reduces psychological stress in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:935–945.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haapamäki J, Heikkinen E, Sipponen T, et al. . The impact of an adaptation course on health-related quality of life and functional capacity of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1074–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miller V, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a role for hypnotherapy? Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2008;56:306–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bullinger M. Forschungsinstrumente zur Erfassung der Lebensqualität bei Krebs -- ein Überblick. In: Verres R, Hasenbring M, eds. Psychosoziale Onkologie. Jahrbuch der medizinischen Psychologie, Vol 3. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, et al. . Cognitive-behavioural therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: 24-month data from a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24:127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zill JM, Christalle E, Tillenburg N, et al. . Effects of psychosocial interventions on patient-reported outcomes in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Prothero L, Barley E, Galloway J, et al. . The evidence base for psychological interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;82:20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hewlett S, Almeida C, Ambler N, et al. ; RAFT Study Group . Reducing arthritis fatigue impact: two-year randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural approaches by rheumatology teams (RAFT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:465–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park KT, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI, et al. . The cost of inflammatory bowel disease: an initiative from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. ; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. . A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:804–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. López-Vivancos J, Casellas F, Badia X, et al. . Validation of the Spanish version of the inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire on ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 1999;60:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA; WHOQOL Group . The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Harper A, Power M. Development of the World Health Organizatio n WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, et al. . The Short Health Scale: a valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1196–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sintonen H. The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33:328–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, et al. . Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7:85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. EuroQol G. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.