Abstract

MXene (e.g., Ti3C2) represents an important class of two‐dimensional (2D) materials owing to its unique metallic conductivity and tunable surface chemistry. However, the mainstream synthetic methods rely on the chemical etching of MAX powders (e.g., Ti3AlC2) using hazardous HF or alike, leading to MXene sheets with fluorine termination and poor ambient stability in colloidal dispersions. Here, we demonstrate a fluoride‐free, iodine (I2) assisted etching route for preparing 2D MXene (Ti3C2Tx, T=O, OH) with oxygen‐rich terminal groups and intact lattice structure. More than 71 % of sheets are thinner than 5 nm with an average size of 1.8 μm. They present excellent thin‐film conductivity of 1250 S cm−1 and great ambient stability in water for at least 2 weeks. 2D MXene sheets with abundant oxygen surface groups are excellent electrode materials for supercapacitors, delivering a high gravimetric capacitance of 293 F g−1 at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1, superior to those made from fluoride‐based etchants (<290 F g−1 at 1 mV s−1). Our strategy provides a promising pathway for the facile and sustainable production of highly stable MXene materials.

Keywords: etching, iodine, MXene, stability, two-dimensional materials

An iodine‐assisted method has been developed for etching bulk Ti3AlC2 in anhydrous acetonitrile (CH3CN), resulting in 2D MXene sheets (Ti3C2Tx, T=O, OH) with intact lattice, high yield (71 %), large size (1.8 μm) and ultimate thickness (<5 nm). 2D MXene sheets present great ambient stability in water for at least 2 weeks and high gravimetric capacitances of 293 F g−1 at 1 mV s−1 when serving as electrode materials for supercapacitors.

Two‐dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides, nitrides or carbonitrides (MXenes) are the latest additions to the family of 2D materials. [1] Their general formula is written as Mn+1Xn T x (n=1–3), where M stands for transition metal (e.g., Ti, Nb, Mo, V, etc.), X is C and/or N, and T x refers to surface terminations such as hydroxyl, oxygen or fluorine, depending on the synthetic conditions and/or the subsequent delamination procedures. Among dozens of experimentally available MXenes, titanium carbide (Ti3C2) is the most popular one, and it has enabled a broad range of applications, including energy storage and conversion,[ 1c , 2 ] electromagnetic interference shielding, [3] water purification, [4] gas‐ and bio‐sensors, [5] lubricants, [6] and catalysts, [7] due to its metallic conductivity [3] and tunable surface functionalities. [8]

To date, chemical etching of Ti3AlC2 (a MAX phase) with fluoride‐based acids or salts (such as HF, LiF/HCl) represents a straightforward approach to prepare 2D Ti3C2Tx (T=O, OH, F). These classic etching agents can react selectively with Al layer and remove the resulting AlF3 efficiently from the interlayer spacing. [9] This is a key step for the subsequent diffusion of etchants and the complete corrosion of Al layers.[ 9a , 10 ] However, the harsh etching reactions and the dissolved oxygen gas in aqueous etchants induce extra structural defects to MXene sheets and promote their degradation into TiO2. [11] Moreover, the acute toxicity of fluoride etchants impedes the sustainable upscaling production of MXene sheets. Although fluoride‐free etching methods, including electrochemical anodic oxidation with NH4Cl or HCl,[ 10b , 12 ] can tackle the safety issues, the prolonged etching reactions (>3 hours) in aqueous solutions are detrimental to achieving high‐quality MXenes. In this regard, a non‐aqueous route was recently developed to etch MAX powders (e.g., Ti3SiC2) in CuCl2 molten salts.[ 8a , 13 ] Apparently, the required high temperature (up to 750 °C) sets an obstacle for the practical production and applications.

Herein, we demonstrate a novel protocol for the synthesis of fluoride‐free MXene using iodine etching (IE) in anhydrous acetonitrile (CH3CN) followed by the delamination in HCl solution. The etching reaction at 100 °C enables the formation of Ti3C2Ix, which can be further transformed into Ti3C2Tx (T=O, OH) flakes (hereinafter referred as IE‐MXene) with moderate sizes (ca. 1.8 μm) and high oxygen content (18.7 wt %). More than 71 % of flakes are thinner than 5 nm, and they are stable in dispersions for at least 2 weeks. Moreover, the filtrated IE‐MXene film presents a high electrical conductivity (1250 S cm−1), comparable with those prepared by fluoride etchants (e.g., 1500 S cm−1). [14] When utilized as electrodes in a supercapacitor, such fluoride‐free, oxygen‐rich MXene electrodes deliver a remarkable gravimetric capacitance of 293 F g−1 at 1 mV s−1, outclassing those of reported fluoride‐terminated MXenes (i.e., F‐MXene, 50–290 F g−1).

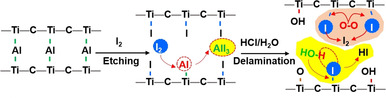

Figure 1 a,b, and Figure S1 show a schematic illustration of the iodine‐assisted synthetic process. MAX powders were immersed into an I2‐CH3CN mixture where the molar ratio of Ti3AlC2:I2 was 1:3. Given that Ti‐Al bonds are more reactive than Ti−C bonds, iodine can remove Al layers selectively from Ti3AlC2, because of its moderate redox potential (E ⊖(I2/I−)=0.54 eV) (Figure S2, 3). The layered etched materials were collected for further delamination. Note that, the accordion‐like structure blocked a small amount of AlI3 particles between the layers, which were difficult to wash away even after repeatedly rinsing with acetonitrile. Therefore, I2‐etched MAX powders were transferred into a 1.0 M HCl aqueous solution to dissolve the remaining AlI3 and delaminate multilayer MXene. We found that manual shaking in HCl solution was efficient enough to separate 2D IE‐MXene sheets, and disperse them in water for further studies. Since the reaction between Al and I2 is thermodynamically dominated, [15] the reaction temperature plays a crucial role (Figure S4). For example, at room temperature (25 °C), the etching reaction did not occur even after 2 weeks. Increasing the temperature to 60 °C enabled a decreasing Al content from 16.7 wt % in the MAX phase to 2.5 wt % in the iodine‐etched samples collected after the delamination in HCl. At 100 °C, the residual amount of Al in such samples was greatly reduced to 0.9 wt % (Table S1).

Figure 1.

a,b) The iodine‐assisted etching and delamination of Ti3AlC2 towards 2D MXene sheets.

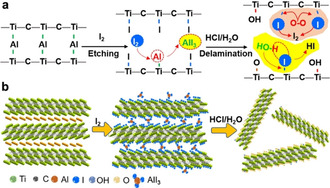

To uncover the mechanism of etching/delamination processes, I2‐etched MAX and 2D IE‐MXene were, respectively collected and characterized. Based on the X‐ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Figure 2 a), the characteristic (104) peak of Ti3AlC2 (2θ=39°) disappears, and the (002) peak (2θ=9.8°) shifts to a lower angle (2θ=6.1°), indicating the expansion of interlayer spacing from 9.3 to 14.4 Å, due to the successful Al etching. AlI3 did not introduce additional peaks to I2‐etched MAX due to its relatively poor crystallinity and small amount. The subsequent washing and delamination of I2‐etched MAX in HCl solution enables further shifting of (002) peak towards an even lower angle (2θ=5.2°), corresponding to an interlayer spacing of 17.4 Å. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (Figure 2 b–d) clearly revealed the morphological changes. Compared with the compact layered bulk Ti3AlC2, I2‐etched MAX had an obvious expansion owing to the introduction of iodide terminated groups (Figure S5), consistent with the XRD results. Energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping was deployed to understand the changes in their chemical structures (Figure S6, 7). Five characteristic elements, including Ti, C, Al, I, and O were detected from I2‐etched MAX, in which Al atoms (3.2 wt %) mainly come from residual AlI3 in interlayer spacing. After AlI3 was removed in the delamination process, only three main elements (Ti, C, and O) were identified from the overview EDS spectrum in 2D IE‐MXene. The iodine content was negligible, but oxygen content had a visible improvement from 6.6 wt % (in the etched MAX) to 18.7 wt % (in 2D IE‐MXene sheets), which is much higher than F‐MXenes (10.8 wt %, Figure S8). In theory, the bond energies of Ti‐I, Ti‐F, and Ti‐O are 310±42, 569±33, and 666.5±5.6 kJ mol−1, respectively. [16] Ti−I bond of Ti3C2Ix is much weaker than Ti−F bond of F‐MXenes; therefore, it undergoes spontaneous substitution reactions with water and oxygen, resulting in the replacement of I with O and OH groups.

Figure 2.

The etching and delamination of Ti3AlC2. a) XRD patterns and SEM images of b) MAX phase, c) I2‐etched MAX, and d) 2D IE‐MXene flakes. e–g) High‐resolution XPS spectra of Ti 2p, I 3d, and C 1s, respectively, in the I2‐etched MAX and IE‐MXene. h) ELF plots for the mechanism of the etching process.

Furthermore, we have examined the formation of AlI3 in the etching process (Figure S9). The obvious color change from brown to dark brown in solution was observed owing to the dissolved AlI3. The brown powder collected from the etching solution shows two weak XRD peaks at 25.5° and 29.1° indexed to AlI3, which was further evidenced by ultraviolet‐visible spectroscopy (UV/Vis) where the etching solution has similar absorption peaks in comparison to pure AlI3 dissolved in acetonitrile. [17] In addition, the overview X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of I2‐etched MAX (Figure 2 e–g) presents five major peaks assigned to O 1s, Ti 2p, C 1s, Al 2p, and I 3d, respectively. High resolution Ti 2p and I 3d bands confirms the presence of Ti‐I bonds as surface groups. As expected, the survey spectrum of 2D IE‐MXene sheets shows three major bands corresponding to O 1s, Ti 2p, C 1s, and negligible Al 2p band (Figure S10). However, no iodine group was detected in the final product, which suggested a complete substitution of iodide. The peak fitting of C 1s and Ti 2p bands reveals the presence of C−O and Ti−O bonds, [18] resulting from the oxygen‐terminated functional groups of 2D IE‐MXene flakes.

According to the achieved experimental results, the mechanism of the synthetic process is proposed as below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Reaction (1) is essential to remove Al layers from the parent Ti3AlC2. Then, reactions (2) and (3) result in ‐O and ‐OH termination of 2D IE‐MXene.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculation was performed to elucidate the bond breaking and reformation between I, Al, and Ti to gain a comprehensive understanding of the etching mechanism by electron localization function (ELF). [19] As shown in Figure 2 h and Figure S11, the MAX phase was modeled with stronger Ti−C (ELF=0.8–0.9) and weaker Ti−Al bonds (ELF=0.4–0.6). To simulate the process, I2 molecules were introduced to the edge of the MAX phase one by one, and the Ti, Al, and C atoms at the bottom edge were fixed while all other atoms were fully relaxed (Figure S12). The etching reaction started with the dissociation of I2 into two reactive I atoms, followed by their adsorption and integration with Ti1 and Ti2 atoms at the edge. Afterwards, the insertion of the second I2 resulted in the spontaneous termination of both Ti1 and Ti2 atoms and sharply reduced Al1‐Ti bonds strength (ELF≈0.1). Then, I atoms from the third I2 molecule bond with the Al1 atom at the edge of the positively charged Ti3AlC2. The addition of a fourth I2 led to the formation of AlI3 (ELF=0.7–0.8) and filled the vacancy by the termination with Ti (ELF=0.5–0.6). Consequently, opening the grain boundaries was favorable for the further penetration of I2, which further weakens Ti‐Al bonding and extracts Al atoms from the MAX phase.

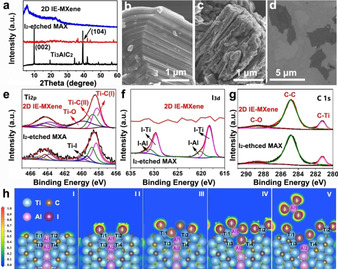

The morphology of the 2D IE‐MXene flakes was elucidated by transmission electron microscope (TEM, Figure 3 a–c), and atomic force microscopy (AFM, Figure 3 d). TEM image displays a typical MXene flake with a thin and flexible feature. Furthermore, the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern indicates a hexagonal symmetry and high crystallinity of the MXene sheets. [20] High‐resolution TEM images (HR‐TEM) collected from different positions (Figure S13) demonstrates the structural integrity of 2D IE‐MXene without showing defective lattices thanks to the mild etching in non‐aqueous solvents. According to AFM images collected from 132 different flakes, the thickness of most flakes (>71 %) was smaller than 5 nm (Figure 3 e,f). Moreover, based on the statistical analysis of 187 individual sheets, the average lateral size of 2D IE‐MXene sheets is 1.8 μm, larger than the MXenes prepared by HF etching (<500 nm).[ 4b , 21 ] The large and thin nature of flakes made it easy to prepare MXene film by filtration of MXene dispersion. The stacked thin films exhibited a high electrical conductivity of 1250 S cm−1, comparable with F‐MXenes (e.g. 1500 S cm−1). [14]

Figure 3.

Structural characterization of the 2D IE‐MXene flakes. a) TEM image, b) high‐resolution TEM image, and c) SAED pattern. d) AFM image, e) the corresponding height profile, and f) statistical thickness distribution (inset: size distribution) of the 2D IE‐MXene flakes.

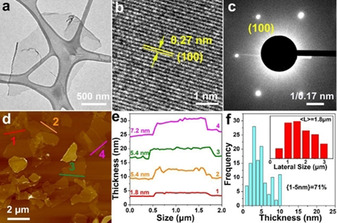

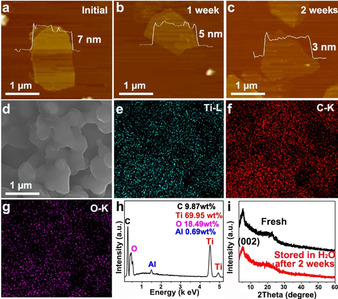

Interestingly, the as‐prepared fluoride‐free IE‐MXene exhibits an enhanced ambient stability compared with F‐terminated MXenes (Table S2). According to our observation and literature work, F‐terminated MXene dispersed in water presented a dramatic change in its morphology and composition and they would transform into TiO2 nanoparticles within two weeks (Figure S14,15). [22] By contrast, the shape and structure of IE‐MXene sheets remain unchanged and well‐defined under the same conditions (Figure 4, Figure S16,17). It has been concluded that the ambient stability of MXene sheets is highly relevant to the density of oxygen functional groups [23] and structural defects. [24] Therefore, the abundant oxide groups as well as crystalline structure are both helpful to extend the ambient lifetime of IE‐MXene sheets.

Figure 4.

The ambient stability of 2D IE‐MXene. a–c) AFM images of the MXene sheets after exposure in water for 1 and 2 weeks, respectively. d) SEM image and e–h) EDS elemental mapping of multiple IE‐MXene sheets after keeping in water for 2 weeks. i) XRD patterns of fresh and ageing IE‐MXene flakes.

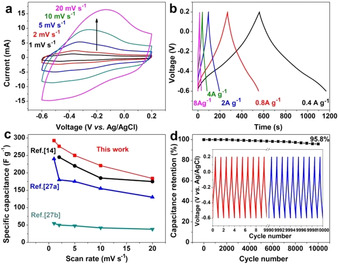

It was reported that the oxygen‐rich MXene has higher capacitance than fluoride‐terminated MXenes because oxygen functional groups can act as active sites to uptake hydrogen ions in supercapacitors. [25] Therefore, the achieved 2D IE‐MXene was investigated to fabricate supercapacitors using a standard three‐electrode system in the 1.0 M H2SO4 aqueous electrolyte. Figure 5 a presented the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves at various scan rates from 1 to 20 mV s−1. The shape of CV curves was similar to F‐MXene, because the capacitance mainly comes from the variation of Ti oxidation state. [25a] The pseudocapacitive behavior was also studied through galvanostatic charge‐discharge (GCD) measurements between −0.6 and 0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at current densities from 0.4 to 8 A g−1 (Figure 5 b). It reveals a typical pseudocapacitive character according to the GCD curves. [26] Remarkably, the gravimetric capacitances calculated from the CV curves is 293 F g−1 at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 (Figure 5 c). This value is superior to previously reported F‐MXene materials, which are generally lower than 290 F g−1 at 1 mV s−1 (Table S3). The great electrochemical performance of IE‐MXene is attributable to the abundant oxygen‐rich surface groups (i.e., O and OH).[ 14 , 27 ] Based on the repeating GCD test at 4 A g−1, the MXene electrode demonstrates an excellent cycling stability with 95.8 % capacitance retention after 10000 cycles (Figure 5 d), which is well comparable with the previously reported MXene‐based electrode materials (Table S3). We also performed the CV scanning of the electrodes after keeping them in water for one and two weeks (Figure S18). No apparent changes in the capacitance were observed even after 2 weeks, further highlighting the excellent ambient stability of IE‐MXene.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical performance of 2D IE‐MXene electrodes including a) CV curves at scan rates of 1–20 mV s−1, b) GCD curves at current densities of 0.4‐8 A g−1. c) Gravimetric capacitances calculated from CV curves as a function of scan rates and d) Cycling stability at a current density of 4 A g−1 (Inset shows the first and last ten GCD curves).

In conclusion, we have developed a novel iodine assisted etching strategy towards 2D fluoride‐free MXene Ti3C2Tx (T=O, OH). The complete removal of Al layer from Ti3AlC2 enables a facile delamination of I2‐etched MAX in HCl solution, leading to oxygen‐rich MXene sheets with high yield (71 %), large size (1.8 μm), and ultimate thickness (<5 nm). Thanks to the non‐aqueous etching process, 2D IE‐MXene sheets exhibit high structural integrity, and they are stable in water for at least 2 weeks, superior to fluoride‐terminated MXenes made from classic etching techniques. The exfoliated IE‐MXene sheets with abundant oxygen surface groups allow for the fabrication of supercapacitors with high gravimetric capacitances of 293 F g−1 and excellent cycling stability, surpassing most of previously reported MXene materials. Our etching strategy is promising for the future development of other types of MXenes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MX‐OSMOPED project), ERC Consolidator Grant on T2DCP, M‐ERA‐NET project HYSUCAP, SPES3 project funded by German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) under Forschung für neue Mikroelektronik (ForMikro) program and GrapheneCore3 881603. The authors thank Davood Sabaghi (TUD), Dr. Markus Löffler (TUD), and Junjie Wang (TUD) for helpful discussions and characterizations. They also acknowledge the cfaed (Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden), the Dresden Center for Nanoanalysis (DCN), and High‐Performance Computing Center (Nanjing Tech University). Yuping Wu appreciates the financial support from NSFC (Distinguished Youth Scientists Project of 51425301) and State Key Lab Research Foundation (ZK201805). H.S. thanks China Scholarship Council (CSC) for financial support. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

H. Shi, P. Zhang, Z. Liu, S. Park, M. R. Lohe, Y. Wu, A. Shaygan Nia, S. Yang, X. Feng, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 8689.

Contributor Information

Dr. Ali Shaygan Nia, Email: ali.shaygan_nia@tu-dresden.de.

Dr. Sheng Yang, Email: s.yang@fkf.mpg.de.

Prof. Xinliang Feng, Email: xinliang.feng@tu-dresden.de.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Naguib M., Gogotsi Y., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 128–135; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Naguib M., Mochalin V. N., Barsoum M. W., Gogotsi Y., Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 992–1005; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Anasori B., Lukatskaya M. R., Gogotsi Y., Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16098. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Lukatskaya M. R., Mashtalir O., Ren C. E., Dall'Agnese Y., Rozier P., Taberna P. L., Naguib M., Simon P., Barsoum M. W., Gogotsi Y., Science 2013, 341, 1502–1505; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Zhang Z., Yang S., Zhang P., Zhang J., Chen G., Feng X., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2920; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Li H., Hou Y., Wang F., Lohe M. R., Zhuang X., Niu L., Feng X., Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601847. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shahzad F., Alhabeb M., Hatter C. B., Anasori B., Hong S. M., Koo C. M., Gogotsi Y., Science 2016, 353, 1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Xie X., Chen C., Zhang N., Tang Z.-R., Jiang J., Xu Y.-J., Nat. Sustainability 2019, 2, 856–862; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Ding L., Wei Y., Wang Y., Chen H., Caro J., Wang H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1825–1829; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 1851–1855. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen Z., Hu Y., Zhuo H., Liu L., Jing S., Zhong L., Peng X., Sun R.-c., Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3301–3312. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xue M., Wang Z., Yuan F., Zhang X., Wei W., Tang H., Li C., RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 4312–4319. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang H., Wu Y., Yuan X., Zeng G., Zhou J., Wang X., Chew J. W., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Kamysbayev V., Filatov A. S., Hu H., Rui X., Lagunas F., Wang D., Klie R. F., Talapin D. V., Science 2020, 369, 979–983; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Shi S., Qian B., Wu X., Sun H., Wang H., Zhang H.-B., Yu Z.-Z., Russell T. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18171–18176; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 18339–18344. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Naguib M., Kurtoglu M., Presser V., Lu J., Niu J., Heon M., Hultman L., Gogotsi Y., Barsoum M. W., Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4248–4253; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Lipatov A., Alhabeb M., Lukatskaya M. R., Boson A., Gogotsi Y., Sinitskii A., Adv. Electron. Mater. 2016, 2, 1600255. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Feng A., Yu Y., Jiang F., Wang Y., Mi L., Yu Y., Song L., Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 6322–6328; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Yang S., Zhang P., Wang F., Ricciardulli A. G., Lohe M. R., Blom P. W., Feng X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15491–15495; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 15717–15721. [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Zhang C. J., Pinilla S., McEvoy N., Cullen C. P., Anasori B., Long E., Park S.-H., Seral-Ascaso A., Shmeliov A., Krishnan D., Morant C., Liu X., Duesberg G. S., Gogotsi Y., Nicolosi V., Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4848–4856; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Habib T., Zhao X., Shah S. A., Chen Y., Sun W., An H., Lutkenhaus J. L., Radovic M., Green M. J., npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2019, 3, 8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pang S.-Y., Wong Y.-T., Yuan S., Liu Y., Tsang M.-K., Yang Z., Huang H., Wong W.-T., Hao J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9610–9616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li Y., Shao H., Lin Z., Lu J., Liu L., Duployer B., Persson P. O. Å., Eklund P., Hultman L., Li M., Chen K., Zha X.-H., Du S., Rozier P., Chai Z., Raymundo-Piñero E., Taberna P.-L., Simon P., Huang Q., Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghidiu M., Lukatskaya M. R., Zhao M.-Q., Gogotsi Y., Barsoum M. W., Nature 2014, 516, 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bergeron D., A. Castleman, Jr. , Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003, 371, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim D., Ko T. Y., Kim H., Lee G. H., Cho S., Koo C. M., ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13818–13828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramadan A. A., Mandil H., Sabouni J., Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 7, 427–433. [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Kang R., Zhang Z., Guo L., Cui J., Chen Y., Hou X., Wang B., Lin C.-T., Jiang N., Yu J., Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9135; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Zhang X., Lv R., Wang A., Guo W., Liu X., Luo J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15028–15033; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 15248–15253. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Becke A. D., Edgecombe K. E., J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ding L., Wei Y., Li L., Zhang T., Wang H., Xue J., Ding L.-X., Wang S., Caro J., Gogotsi Y., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin H., Wang X., Yu L., Chen Y., Shi J., Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Natu V., Hart J. L., Sokol M., Chiang H., Taheri M. L., Barsoum M. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12655–12660; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 12785–12790; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Zhao X., Vashisth A., Prehn E., Sun W., Shah S. A., Habib T., Chen Y., Tan Z., Lutkenhaus J. L., Radovic M., Green M. J., Matter 2019, 1, 513–526. [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Fu Z., Zhang Q., Legut D., Si C., Germann T., Lookman T., Du S., Francisco J., Zhang R., Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 104103; [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Lee Y., Kim S. J., Kim Y.-J., Lim Y., Chae Y., Lee B.-J., Kim Y.-T., Han H., Gogotsi Y., Ahn C. W., J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xia F., Lao J., Yu R., Sang X., Luo J., Li Y., Wu J., Nanoscale 2019, 11, 23330–23337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Lukatskaya M. R., Bak S. M., Yu X., Yang X. Q., Barsoum M. W., Gogotsi Y., Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500589; [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Zhang P., Wang F., Yu M., Zhuang X., Feng X., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 7426–7451; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25c. Tang J., Mathis T. S., Kurra N., Sarycheva A., Xiao X., Hedhili M. N., Jiang Q., Alshareef H. N., Xu B., Pan F., Gogotsi Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17849–17855; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 18013–18019. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yan J., Ren C. E., Maleski K., Hatter C. B., Anasori B., Urbankowski P., Sarycheva A., Gogotsi Y., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701264. [Google Scholar]

- 27.

- 27a. Yoon Y., Lee M., Kim S. K., Bae G., Song W., Myung S., Lim J., Lee S. S., Zyung T., An K.-S., Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703173; [Google Scholar]

- 27b. Wang J., Tang J., Ding B., Malgras V., Chang Z., Hao X., Wang Y., Dou H., Zhang X., Yamauchi Y., Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary