Abstract

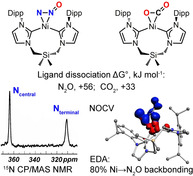

A nickel complex incorporating an N2O ligand with a rare η2‐N,N′‐coordination mode was isolated and characterized by X‐ray crystallography, as well as by IR and solid‐state NMR spectroscopy augmented by 15N‐labeling experiments. The isoelectronic nickel CO2 complex reported for comparison features a very similar solid‐state structure. Computational studies revealed that η2‐N2O binds to nickel slightly stronger than η2‐CO2 in this case, and comparably to or slightly stronger than η2‐CO2 to transition metals in general. Comparable transition‐state energies for the formation of isomeric η2‐N,N′‐ and η2‐N,O‐complexes, and a negligible activation barrier for the decomposition of the latter likely account for the limited stability of the N2O complex.

Keywords: back bonding, carbon dioxide, N-heterocyclic carbenes, nickel, nitrous oxide

The characterization of η2‐N,N′‐N2O and CO2 complexes of nickel and the associated computational study reveal that the bonding ability of N2O to nickel is intermediate between that of CO2 and that of H2C=CH2. It is shown that in general, N2O η2‐binds to metals comparably to or stronger than CO2, indicating that the rarity of η2‐N2O metal complexes is due mostly to its oxidizing character and not to its weak σ‐donating and π‐accepting properties.

Among the numerous oxides of nitrogen, nitrous oxide (N2O) is most intimately intertwined with modern human activities. It figures on the WHO's List of Essential Medicines for use in pain management, [1] and it also has a long history as a recreational drug dubbed “laughing gas”. [2] It is used as an oxidant (“nitrous”) in racing engines and is a suitable propellant in rockets, [3] as well as in whipped cream and cooking oil canisters. Industrially, N2O is an important by‐product in nitric acid and adipic acid manufacturing. [4] Although industrial pollutants are not to be neglected, natural, enzymatic denitrification processes [5] are the main source of N2O in the environment and for this reason the gas was proposed to be part of the biosignature of life on exoplanets. [6] The widespread use of nitrogen fertilizers led to an enhancement of denitrification processes and N2O rose to prominence as a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than CO2, and “the dominant ozone‐depleting substance emitted in the 21st Century”. [7] Although its decomposition into elements is thermodynamically favorable (Δf H°gas 82.1 kJ mol−1), the high activation barrier (250 kJ mol−1) [8] associated with this process means that N2O persists in the atmosphere for an average of 117(8) years. [9] Consequently, interest towards using N2O as a synthon, [10] as well as towards catalyzing its decomposition into elements has increased in recent years, [11] in turn prompting investigations meant to elucidate the interaction of this prominent small molecule with metals.

N2O reacts readily with numerous metal complexes and organic substrates, mostly as an oxidant but also as a nitrogen atom donor,[ 4 , 10 ] and can be trapped by frustrated Lewis pairs [12] and N‐heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs). [13] Its reactivity involving insertion into M−C and M−H bonds is well documented.[ 10 , 14 ] In contrast to its isoelectronic counterpart CO2, which has a rich coordination chemistry, [15] N2O has been generally described as a poor, or exceedingly poor ligand due to its weak σ‐donating and π‐accepting properties, low polarity, and oxidizing character.[ 8b , 16 ]

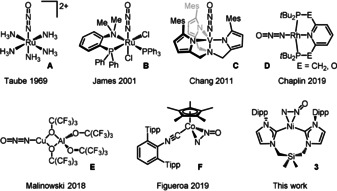

Extensive investigations of ruthenium derivative A (Figure 1), which remained for more than three decades the only known metal complex of nitrous oxide, revealed that N2O coordinated in a linear fashion via the terminal nitrogen and was a poor ligand susceptible to reduction and displacement. [17] These conclusions were supported by computational studies,[ 17c , 18 ] the spectroscopic characterization of complex B, [19] as well as the NMR characterization of surface‐coordinated N2O. [20] Confirmation of these findings was provided over the last decade by the comprehensive characterization of discrete, end‐on bonded complexes C, D and E (Figure 1).[ 21 , 22 , 23 ] The rich coordination chemistry of CO2 suggests that the isoelectronic N2O molecule should also be able to adopt a bent, N,N′‐side‐on coordination mode, which had been probed computationally for surface binding. [24] Linear N2O bound at the [4Cu:2S] active site of nitrous oxide reductase has been shown to display long, side‐on Cu⋅⋅⋅N contacts. [25] Ultimately, the first η2‐N,N′‐N2O complex F, which was persistent below −25 °C, was recently characterized and the π‐basicity of the metal was shown to be key to its isolation. [26]

Figure 1.

Transition metal complexes of N2O.

We reported on a bis(NHC)2Ni0‐GeCl2 complex incorporating a siloxane‐linked (NHC)2Ni0 fragment with a bent L2M geometry. [27] Computational studies indicated that this fragment featured the frontier orbitals necessary for efficient η2‐interactions with π‐acidic ligands.[ 18c , 28 ] Thus, we hypothesized that a bis(NHC)2 supported Ni0 would be an excellent candidate for stabilizing side‐on, η2‐N2O complexes, especially taking into account the resilience of NHC ligands to oxidation. Design of ligand 1, incorporating a shorter silane linker, aimed to impose a narrow CNHC‐Ni‐CNHC angle and increase the π‐basicity of the metal. [29] This allowed us to characterize analogous η2‐bound Ni0 complexes of N2O and CO2 and to assess the relative binding ability of the two ligands for the first time.

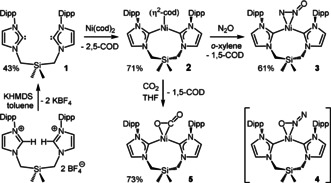

Prepared by deprotonation of its bis(imidazolium) precursor, ligand 1 reacted with Ni(cod)2 to yield (1)Ni(η2‐cod), 2 (Scheme 1). Solution 1H NMR analysis of 2 revealed a broad, complex spectrum denoting C 1 symmetry, reflected in the 13C NMR spectrum by the presence of two resonances for the coordinated carbene carbons (200.4 and 208.4 ppm). Reduced conformational fluxionality in complexes containing bis(NHC)Ni fragments was shown to lead to broad, poorly resolved resonances in the solution NMR spectra, as well as lowering of the expected time‐averaged symmetry. [27] An X‐ray diffraction experiment on 2 confirmed chelation of the ligand to Ni in a bent geometry (C1‐Ni1‐C8 107.9(1)°) (Figure S28) and the η2‐coordination of 1,5‐cyclooctadiene.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1–3 and 5, and the postulated, fleeting η2‐N,O‐isomer 4. Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl.

In solution, complex 2 reacted with 1 atm of N2O at room temperature to yield 3, which was isolated as a yellow crystalline solid. The low solubility of 3 precluded its characterization in solution. As a solid, it can be stored for months at −78 °C and handled at room temperature in vacuum or under an inert atmosphere, but partial decomposition is apparent after 12 hours at room temperature (by IR). Heating to 70 °C in THF leads to dissolution upon N2 development (Figure S3). The 13C CP‐MAS NMR spectrum of 3 (Figure S19) features two resonances corresponding to the coordinated carbene carbons at 183.7 and 192.5 ppm, similar to the values measured in solution for 2.

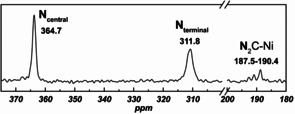

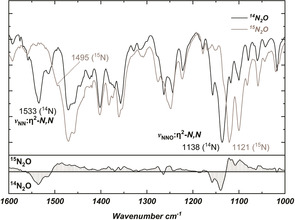

The 15N CP‐MAS NMR resonances for bound N2O in an isotopically enriched sample of 3 were observed at 365 and 312 ppm (Figure 2), corresponding to the central and terminal nitrogen atoms in N2O, respectively (vs. the gas phase computed values of 395 and 313 ppm). These values are significantly deshielded compared to those observed in the κ1‐N‐N2O and the η2‐N,N′‐N2O complexes, as well as those for free N2O (Table 1). Resonances corresponding to the naturally abundant nitrogen atoms in the imidazole rings appear between 187.5–190.4 ppm, matching literature data for NHC ligands. [30] Infrared spectroscopy suggests that N2O is side‐on, η2‐N,N′‐coordinated in 3. The observed ν NN stretching and ν NNO bending vibrations (Figure 3) at 1533 and 1138 cm−1, respectively (vs. the gas phase computed values of 1725 and 1243 cm−1, and the experimental values for F of 1624 and 1131 cm−1) shift to lower frequencies (1495 and 1121 cm−1) in 15N‐enriched samples of 3. The ν NN stretching vibration measured in 3 is the lowest value observed in N2O metal complexes, both κ1‐N‐N2O (2234–2303 cm−1 for ν NN and 1150–1337 cm−1 for ν NO in A–E) and η2‐N,N′‐N2O (1624 cm−1 for ν NN and 1131 cm−1 for ν NNO in F), in agreement with the high π‐basicity of the (1)Ni0 fragment and its strong interaction with the π* system of N2O.

Figure 2.

15N CP‐MAS NMR spectrum of 3 containing 33 % 15N2O, the latter prepared using an original method (see Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Selected 15N NMR resonances for free and bound N2O.

|

Cpd. |

N2O [26] |

B [19] |

D [a], [22] |

D [b], [22] |

F [26] |

3 |

3 [c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Solv. |

tol‐d 8 |

CD2Cl2 |

DFB[d] |

DFB[d] |

tol‐d 8 |

solid |

gas |

|

δNterm |

135 |

126 |

109 |

103 |

159 |

312 |

313 |

|

δNcent |

218 |

|

245 |

246 |

309 |

365 |

395 |

[a] E=CH2. [b] E=O. [c] Computed. [d] DFB=1,2‐F2C6H4.

Figure 3.

Overlaid FT‐IR spectra for 3 and 3‐(15N2O) (99 % isotopically enriched) with spectral difference below.

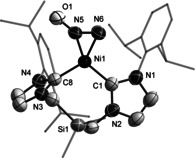

X‐ray crystallography revealed for 3 the expected, bent (1)Ni fragment (∡CNC 104.47(13)°) with the side‐on, η2‐N,N′‐coordinated N2O ligand completing the coordination sphere of nickel (Figure 4). The metric parameters characterizing the N2O moiety (N5−N6 1.225(4) Å and N5−O1 1.276(4) Å) are consistent with the calculated values and compare well with the N−N bond length measured in F (1.212(8) Å). The dihedral angle formed by the N2O and CNHCNiCNHC planes measures only 8.4(3)°.

Figure 4.

Solid‐state structure of one of the two independent molecules of 3 with 50 % thermal ellipsoids, and hydrogen atoms omitted. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] with [calculated values]: N5–N6 1.225(4) [1.210], N5–O1 1.276(4) [1.239], Ni1–N5 1.803(3) [1.821], Ni–N6 1.926(3) [1.910], Ni1–C1 1.901(3) [1.934], Ni1–C8 1.893(3) [1.919]; N5‐N6‐O1 134.7(3) [138.4], C1‐Ni1‐C8 104.47(13) [107.7].

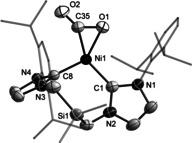

Aiming to provide a comparison for 3, its CO2 analog 5 was prepared by reaction of 2 with 1 atm of CO2 in THF. The product was stable under an inert atmosphere and did not dissolve in hydrocarbon or ethereal solvents. The solid‐state 13C NMR spectrum of 5 (Figure S21) is very similar to the spectrum of 3, featuring two carbene resonances (188.2 and 192.2 ppm) and a resonance corresponding to the CO2 ligand (167.3 ppm). A characteristic ν CO stretching vibration is observed in the IR spectrum of 5 at 1695 cm−1 (vs. the gas phase computed value of 1855 cm−1). The solid‐state structure of 5 (Figure 5) is very similar to that of 3. The bond angles in the coordinated CO2 and N2O match closely (∡NNO 134.7(3)° in 3 vs. ∡OCO 135.0(2)° in 5) but differences are apparent in the bond distances to their terminal atoms (N5−O1 1.275(3) Å in 3 vs. C35−O2 1.217(3) Å in 5).

Figure 5.

Solid‐state structure of 5 with 50 % thermal ellipsoids, and hydrogen atoms omitted. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] with [calculated values]: O1–C35 1.283(4) [1.264], C35–O2 1.218(4) [1.206], Ni1–O1 1.949(2) [1.937], Ni–C35 1.828(3) [1.839], Ni1–C1 1.973(3) [1.964], Ni1–C8 1.866(2) [1.856]; O1‐C35‐O2 134.6(3) [137.5], C1‐Ni1‐C8 106.95(10) [109.4].

A DFT comparison of the binding energies of L in (1)Ni(L) (with ΔG° in parenthesis) yielded values of 87 (33) and 110 (56) kJ mol−1 for L=CO2 and N2O, respectively, while for a hypothetical complex of (1)Ni with the classic π‐acceptor ethylene, the energies are even greater, at 129 (74) kJ mol−1. Furthermore, an energy decomposition analysis with ETS‐NOCV revealed that the instantaneous interaction energies of L in (1)Ni(L) follow a similar trend, largely owing to the significantly stronger orbital interactions (in parathesis): −401 (−643) and −415 (−709) kJ mol−1 for L=CO2 and N2O, respectively. The total orbital interaction term can further be decomposed using NOCV, showing a dominant contribution (83 % for 3 and 84 % for 5) involving donation from the metal to the π* system of the ligand. Taken as a whole, the results of DFT calculations indicate that N2O binds to (1)Ni0 slightly stronger than CO2 due to stronger orbital interactions in 3. To probe whether the observed energetic trend is more general, the equilibrium TM‐CO2 + N2O TM‐N2O + CO2 (TM=transition metal fragment) was analyzed computationally for 12 crystallographically characterized η2‐C,O‐CO2 complexes and their hypothetical N2O analogues. The data (Table S2) showed stronger binding for N2O in 9 systems (up to 26 kJ mol−1) demonstrating that when bound in η2‐fashion, N2O is a comparable or slightly better π‐acceptor than CO2. However, it needs to be stressed that N2O is oxidizing whereas CO2 is not, for which reason the increased binding energy in the hypothetical N2O systems considered above is unlikely to stabilize η2‐N,N‐N2O complexes over metal or ligand oxidation.

The energy landscape for the formation of 3 from (1)Ni0 and N2O was also probed with computational methods (Figure S31). The results revealed that the formation of 3 involves a modest barrier (ΔG ≠=38 kJ mol−1), with ΔG°=−56 kJ mol−1. The formation of the η2‐O,N‐N2O isomer, 4, though not observed experimentally, was found to involve a greater barrier (ΔG ≠=70 kJ mol−1) and a minute ΔG° of −2 kJ mol−1. However, 4 appears to be a metastable species and readily converts to (1)NiO(N2) almost without a barrier. Barrierless decomposition of η2‐O,N‐N2O bound to iron has been investigated computationally and matched experimental observations. [31] Thus, at a relative energy of −63 kJ mol−1, (1)NiO(N2) represents the lowest energy point on the potential energy surface and confirms that metal‐oxo formation is thermodynamically favored over η2‐N,N‐N2O complex formation, albeit only by 7 kJ mol−1. As suggested by the calculated energy landscape, 3, unlike 5, is a kinetic, not a thermodynamic, product, in agreement with its limited stability. Similarly, decomposition of F was reported to proceed via formation of a reactive metal‐oxo species and transfer of oxygen to the ancillary isocyanide ligand. [26]

To summarize, employing the π‐basic fragment (1)Ni, we isolated 3 by reaction of 2 with N2O. The rare η2‐N,N′‐coordination mode of the N2O ligand in 3 was proved by single‐crystal X‐ray crystallography, as well as 15N CP‐MAS NMR and IR spectroscopy aided by 15N isotopic enrichment. The isostructural, η2‐CO2 complex 5 was also synthesized, allowing a direct comparison of the metal binding properties of the two isoelectronic small molecules of environmental relevance. Computational studies indicate that π‐acceptance is the main contributor to N2O binding in 3, and place the η2‐N,N′‐metal binding ability of this ligand to the (1)Ni fragment in‐between that of CO2 and ethylene. In general, the η2‐N,N′‐binding ability of N2O to transition metals is found to be comparable to, or slightly better than that of CO2. This demonstrates that the need for a strongly π‐basic metal fragment comes not so much from the frequently invoked “poor σ‐donating and π‐accepting properties” of N2O, but from the need to stabilize η2‐N,N′‐coordination over the thermodynamically more favorable metal‐oxo formation. The well‐known oxidizing character of N2O may be mostly, if not entirely responsible for the scarcity of η2‐metal complexes employing this ligand, and more of such complexes are expected to be in reach in designs featuring the right balance of π‐basicity and resilience to oxidation at the metal center and associated ligands.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the Universities of Calgary, Jyväskylä, and Alberta, as well as the NSERC of Canada in the form of Discovery Grants #2019‐07195 to R.R. and #2019‐06816 to R.E.W. The project received funding from the European Research Council under the EU's Horizon 2020 programme (grant #772510 to H.M.T). R.E.W. acknowledges the CFI and the Government of Alberta for NMR Facilities support. Computational resources were provided by the Finnish Grid and Cloud Infrastructure (persistent identifier urn:nbn:fi:research‐infras‐2016072533) and the University of Calgary.

B. M. Puerta Lombardi, C. Gendy, B. S. Gelfand, G. M. Bernard, R. E. Wasylishen, H. M. Tuononen, R. Roesler, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7077.

In memory of Professor Suning Wang

Contributor Information

Prof. Heikki M. Tuononen, Email: heikki.m.tuononen@jyu.fi.

Prof. Roland Roesler, Email: roesler@ucalgary.ca.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. 2019 Geneva: World Health Organization.

- 2. Laing M., S. Afr. J. Sci. 2003, 99, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zakirov V., Sweeting M., Lawrence T., Sellers J., Acta Astronautica 2001, 48, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parmon V. N., Panov G. I., Uriarte A., Noskov A. S., Catal. Today 2005, 100, 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Lehnert N., Dong H. T., Harland J. B., Hunt A. P., White C. J., Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Grenfell J. L., Phys. Rep. 2017, 713, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravishankara A. R., Daniel J. S., Portmann R. W., Science 2009, 326, 123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Chang A. H. H., Yarkony D. R., J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 6824–6831; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Trogler W. C., Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 187, 303–327. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prather M. J., Hsu J., DeLuca N. M., Jackman C. H., Oman L. D., Douglass A. R., Fleming E. L., Strahan S. E., Steenrod S. D., Søvde O. A., Isaksen I. S. A., Froidevaux L., Funke B., J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 5693–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Severin K., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6375–6386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Konsolakis M., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6397–6421. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a. Otten E., Neu R. C., Stephan D. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9918–9919; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Neu R. C., Otten E., Lough A., Stephan D. W., Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 170–176; [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Kelly M. J., Gilbert J., Tirfoin R., Aldridge S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 14094–14097; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 14344–14347. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Tskhovrebov A. G., Solari E., Wodrich M. D., Scopelliti R., Severin K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 232–234; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 236–238; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Tskhovrebov A. G., Vuichoud B., Solari E., Scopelliti R., Severin K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9486–9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Vaughan G. A., Rupert P. B., Hillhouse G. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5538–5539; [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Vaughan G. A., Sofield C. D., Hillhouse G. L., Rheingold A. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 5491–5493. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a. Pastor A., Montilla A., Galindo F., Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2017, 68, 1–91; [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Paparo A., Okuda J., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 334, 136–149. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tolman W. B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1018–1024; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Armor J. N., Taube H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1969, 91, 6874–6876; [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Bottomley F., Brooks W. V. F., Inorg. Chem. 1977, 16, 501–502; [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Paulat F., Kuschel T., Näther C., Praneeth V. K. K., Sander O., Lehnert N., Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 6979–6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Tuan D. F.-T., Hoffmann R., Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 871–876; [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Yu H., Jia G., Lin Z., Organometallics 2008, 27, 3825–3833; [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Andino J. G., Caulton K. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12576–12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pamplin C. B., Ma E. S. F., Safari N., Rettig S. J., James B. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 8596–8597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.

- 20a. Hu S., Apple T. M., J. Catal. 1996, 158, 199–204; [Google Scholar]

- 20b. Mastikhin V. M., Mudrakovsky I. L., Filimonova S. V., Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 149, 175–179; [Google Scholar]

- 20c. Mastikhin V. M., Mudrakovsky I. L., Filimonova S. V., Zeolites 1990, 10, 593–597. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Piro N. A., Lichterman M. F., Harman W. H., Chang C. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2108–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gyton M. R., Leforestier B., Chaplin A. B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15295–15298; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 15439–15442. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhuravlev V., Malinowski P. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 11697–11700; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 11871–11874. [Google Scholar]

- 24.

- 24a. Hu C.-L., Chen Y., Li J.-Q., Zhang Y.-F., Chem. Phys. Lett. 2007, 438, 213–217; [Google Scholar]

- 24b. Heyden A., Peters B., Bell A. T., Keil F. J., J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 1857–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pomowski A., Zumft W. G., Kroneck P. M. H., Einsle O., Nature 2011, 477, 234–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mokhtarzadeh C. C., Chan C., Moore C. E., Rheingold A. L., Figueroa J. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15003–15007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gendy C., Mansikkamäki A., Valjus J., Heidebrecht J., Hui P. C.-Y., Bernard G. M., Tuononen H. M., Wasylishen R. E., Michaelis V. K., Roesler R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 154–158; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 160–164. [Google Scholar]

- 28.

- 28a. Ziegler T., Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 1547–1552; [Google Scholar]

- 28b. Wolters L. P., Bickelhaupt F. M. in Structure and Bonding (Eds.: Eisenstein O., Macgregor S.), Springer, Berlin, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.

- 29a. Massera C., Frenking G., Organometallics 2003, 22, 2758–2765; [Google Scholar]

- 29b. Hering F., Nitsch J., Paul U., Steffen A., Bickelhaupt F. M., Radius U., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1426–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arduengo A. J., Harlow R. L., Kline M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 361–363. [Google Scholar]

- 31.

- 31a. Armentrout P. B., Halle L. F., Beauchamp J. L., J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 2449–2457; [Google Scholar]

- 31b. Zhao L., Wang Y., Guo W., Shan H., Lu X., Yang T., J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 5676–5683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary