Abstract

Rationale:

MicroRNA-33 post-transcriptionally represses genes involved in lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis. Targeted inhibition of miR-33 increases plasma HDL cholesterol and promotes atherosclerosis regression, in part, by enhancing reverse cholesterol transport and dampening plaque inflammation. However, how miR-33 reshapes the immune microenvironment of plaques remains poorly understood.

Objective:

To define how miR-33 inhibition alters the dynamic balance and transcriptional landscape of immune cells in atherosclerotic plaques.

Methods and Results:

We used single cell RNA-sequencing of aortic CD45+ cells, combined with immunohistologic, morphometric and flow cytometric analyses to define the changes in plaque immune cell composition, gene expression and function following miR-33 inhibition. We report that anti-miR-33 treatment of Ldlr−/− mice with advanced atherosclerosis reduced plaque burden and altered the plaque immune cell landscape by shifting the balance of pro- and anti-atherosclerotic macrophage and T cell subsets. By quantifying the kinetic processes that determine plaque macrophage burden, we found that anti-miR-33 reduced levels of circulating monocytes and splenic myeloid progenitors, decreased macrophage proliferation and retention, and promoted macrophage attrition by apoptosis and efferocytotic clearance. scRNA-sequencing of aortic arch plaques showed that anti-miR-33 reduced the frequency of MHCIIhi “inflammatory” and Trem2hi “metabolic” macrophages, but not tissue resident macrophages. Furthermore, anti-miR-33 led to derepression of distinct miR-33 target genes in the different macrophage subsets: in resident and Trem2hi macrophages, anti-miR-33 relieved repression of miR-33 target genes involved in lipid metabolism (e.g., Abca1, Ncoa1, Ncoa2, Crot), whereas in MHCIIhi macrophages, anti-miR-33 upregulated target genes involved in chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation. Anti-miR-33 also reduced the accumulation of aortic CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Th1 cells, and increased levels of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in plaques, consistent with an immune-dampening effect on plaque inflammation.

Conclusions:

Our results provide insight into the immune mechanisms and cellular players that execute anti-miR-33’s atheroprotective actions in the plaque.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis regression, adaptive immunity, innate immunity, microRNA, atherosclerosis, inflammation

Subject Terms: Cellular Reprogramming, Metabolism, Vascular Biology

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Considerable evidence supports a pathogenic role for chronic inflammation in the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerotic inflammation is initiated by the accumulation of native and modified apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing lipoproteins in the arterial intima, which triggers innate and adaptive immune responses1, 2. Hyperlipidemia, a risk factor for atherosclerosis, is associated with an increase in myelopoiesis and circulating monocyte numbers in mice and humans, which can accelerate atherogenesis3–5. Monocyte-derived and tissue-resident macrophages contribute prominently to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis through their proliferation, retention and eventual death in the plaque6. These accruing macrophages elaborate pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that amplify the innate immune response and trigger the adaptive immune system, through the recruitment and expansion of dendritic cells, T cells, B cells and NK cells6, 7. While therapies directed at lowering levels of apoB-lipoproteins remain the pillar of atherosclerosis treatments, they have proven inadequate to substantially regress the plaque burden observed in the majority of patients with established atherosclerosis8, 9. Given the prominent role of chronic inflammation in atherogenesis, identifying therapeutic strategies to dampen plaque inflammation for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease has been an area of intense investigative focus.

MicroRNAs (miRNA) have emerged as key post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression that can act as rheostats of biological pathways. Binding of these small non-coding RNAs to the 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR) of mRNAs mediates translational repression and/or mRNA degradation. Notably, individual miRNAs can have multiple gene targets, often in related pathways, providing a mechanism to coordinately regulate gene expression. A prime example of this paradigm is miR-33, which provides a layer of post-transcriptional control over genes engaged in lipid homeostasis, nutrient sensing and energy regulation. Previous studies from our group and others have shown that miR-33 regulates genes involved in cholesterol mobilization and excretion (Abca1, Abcg1, Npc1, Osbpl6, Atp8b1, Abcb11)10–15, mitochondrial respiration (Prkaa1, Ppargc1a, Pdk4, Slc25a25)16, 17, fatty acid oxidation (Hadhb, Crot, Cpt1a, Sirt6)17–19, gluconeogenesis (Pck1, G6pc)20, autophagy (Atg5, Lamp1)15, 19, and adaptive thermogenesis (Dio2, Zfp516, Ppargc1a)21. In humans, miR-33a and miR-33b are located within introns of the SREBP2 and SREBP1 genes, whereas mice have a single copy of miR-33 present within the Srebf2 gene locus10, 17. Expression of miR-33 is co-regulated with its host genes in response to metabolic signals and NFkB activation10, 19, and thus integrates cellular metabolic responses with repression of key gene pathways.

Targeting of miR-33 in mice and monkeys promotes cholesterol efflux from hepatocytes and macrophages, increasing plasma levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL-C) and reverse cholesterol transport10–12, 22, 23, which is thought to protect from atherosclerosis. Indeed, atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− mice treated on chow diet with miR-33 antisense oligonucleotides for 4 weeks show an increase in plasma levels of HDL-C and regression of atherosclerosis23. However, not all of the anti-atherosclerotic effects of miR-33 inhibition can be attributed to increases in HDL-C and reverse cholesterol transport, as anti-miR-33 also inhibits atherosclerosis progression in Ldlr−/− mice during continued western diet feeding, which fails to increase HDL-C levels24, 25. The additional atheroprotective effects of miR-33 inhibition have been attributed, in part, to the ability of miR-33 to alter macrophage metabolism to favor glycolysis over fatty acid oxidation, which can direct macrophage inflammatory polarization24. Inhibition of miR-33 increases macrophage mitochondrial activity and fatty acid oxidation, which promotes a tissue reparative or M2-like macrophage phenotype16, 24. Further understanding of the mechanisms through which miR-33 silencing alters the immune cell functions in the atherosclerotic plaque may reveal key pathways that promote the resolution of atherosclerotic inflammation and tissue repair in the artery wall.

Technological advances in the last several years have facilitated more detailed analyses of plaque immune cell constituents. Specifically, single cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) of aortic immune cells has enabled a deeper understanding of the multiple leukocyte populations and their associated transcriptomes in the plaque26–29. This technique has unveiled the diversity of macrophage subsets in the plaque, and allowed new classification of these populations using mRNA signatures30. However, a current challenge in the field is integrating such scRNA-seq findings with macrophage phenotypes and functions in atherosclerotic plaques historically defined through histological staining and flow cytometry of protein markers. In the current study, we investigated how inhibition of miR-33 alters the dynamic balance and transcriptional landscape of immune cells in atherosclerotic plaques. Using scRNA-seq combined with monocyte-labeling techniques, immunohistological staining and flow cytometry we show that anti-miR-33 alters the dynamic balance of innate and adaptive immune cells in plaques to favor inflammation resolution and tissue repair. We demonstrate that anti-miR-33 reduces the frequency of the MHCIIhi “inflammatory” and Trem2hi “metabolic” macrophage subsets, CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Th1 cells in plaques, but increases numbers of immune-dampening regulatory T cells. Using macrophage subpopulations as an example, we correlate changes in macrophage kinetic processes with changes in the transcriptomic profiles of resident, MHCIIhi, and Trem2hi subsets, to unveil the distinct contributions of these plaque macrophage subtypes to anti-miR-33’s anti-atherosclerotic effects. Furthermore, we demonstrate distinct miR-33 target gene derepression in the various immune cell subsets of the plaque. Together, our findings connect the functional and transcriptional phenotypic changes of plaque macrophages and other immune cells upon miR-33 silencing to provide insight into the mechanisms underlying anti-miR-33’s atheroprotective actions in the plaque.

METHODS

Data, analytic methods (code), and research materials transparency.

RNA-sequencing data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE161494. Other data, analytic methods, and study materials are available to other researchers upon request from the corresponding author. Extended methods and Major Resources Table included in the Supplemental Materials.

Mouse studies.

All experimental procedures were done in accordance with the US Department of Agriculture Animal Welfare Act and the US Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the New York University School of Medicine’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Analyses of mouse experiments were blinded whenever possible through numerical coding of samples. Sample size was predefined as n = 8–10 mice/group for morphometric and flow cytometry analyses, and n = >5 for immunostaining analyses, as noted. Eight week old male Ldlr–/– mice (C57Bl6 LDLrtm1Her from Jackson Laboratories, ME, USA) were placed on a western diet (21% [wt/wt] fat, 40% fat kcal, 0.3% cholesterol; Dyets #101977GI) for 14 weeks to induce atherosclerosis, after which mice were either sacrificed to perform baseline measurements or switched to chow diet and randomized into 2 treatment groups (n = 23 mice/group). Mice received 2 subcutaneous injections of 10 mg/kg 2′F/MOE control anti-miR (TTATCGCCATGTCCAATGAGGCT) or anti-miR-33 (TGCAATGCAACTACAATGCAC) oligonucleotides (Regulus Therapeutics, CA, USA) in the first week, spaced 2 days apart, and then weekly injections thereafter for a total of 4 weeks. At sacrifice, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, exsanguinated by vena cava and tissues collected for sectioning, flow cytometry or transcriptomic analyses. During analyses, technical issues during aorta sectioning led to exclusion of 3 mice from the control group and 1 mouse from anti-miR-33 group. During the treatment, 2 mice in the anti-miR-33 group died during retroorbital injection and were excluded from the study.

Labelling and tracking of blood monocytes.

Circulating blood monocytes were labeled in vivo by retro-orbital injection of 1 µm Fluoresbrite YG microspheres (Polysciences Inc., PA, USA) diluted in sterile PBS (1:4) as described31, 32, 3 days before sacrifice to determine the recruitment of Ly6Clo monocytes. Ly6Chi monocytes were labelled by intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of Edu (5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine) from Life Technologies (NY, USA) as described33, 34, 3 days to assess recruitment or 28 days prior euthanasia to assess macrophage retention. The efficiency of fluorescent beads or EdU labelling was verified 24 hours after injection by flow cytometry of blood monocytes. Edu was detected using the Click IT EdU Pacific Blue Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Life Technologies, NY, USA). The number of EdU (Ly6Chi) monocyte-derived macrophages in aortic root sections was quantified using the Click-IT reaction with Alexa Fluor 647 nm-azide (Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit, Invitrogen, CA, USA).

Atherosclerosis analysis.

OCT embedded hearts were sectioned through the aortic root (6 μm) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for lesion quantification or used for immunohistochemical analysis. For morphometric analyses of lesions, 6 sections per mouse were imaged, spanning the entire aortic root, and lesions and necrotic area were quantified using ImageJ Software. Necrosis was quantified in aortic roots by measuring the acellular areas of plaques with ImageJ software as previously described31. Immunostaining and subsequent analyses were performed as described in extended methods. Representative images were selected to represent the mean value of each condition.

Transcriptomic profiling.

RNA isolation from the aorta and Nanostring gene expression profiling were performed as described in extended methods. Single-cell RNA-sequencing was performed on CD45+ cells isolated from pooled aortic arches of 4 mice per group and analysed as described in extended methods.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry analysis was performed as described in extended methods.

Statistics.

GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Data are presented as mean ± standard error (S.E.M.) unless otherwise indicated, and p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Briefly, the normality of data was first tested by Shapiro Wilk normality test. The normally distributed data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test for more than 2 group comparison, and by Student’s t test for two group comparison. For the data that didn’t pass Shapiro Wilk normality test, Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc Dunn’s test were used for more than 2 group comparison and Mann-Whitney U-test for 2 group comparison. For the single-cell RNA-seq and pathway analyses, unless otherwise noted, we report adjusted p-values that have been corrected for multiple testing using Benjamini-Hochberg. The average log fold change values were calculated using the following equation:

T tests were then performed for each cluster using expression values from all anti-miR-33 cells in that cluster vs. expression values from all control cells in that cluster. No experiment-wide multiple test correction was applied.

RESULTS

Inhibition of miR-33 promotes atherosclerosis regression by altering innate and adaptive immune cell populations.

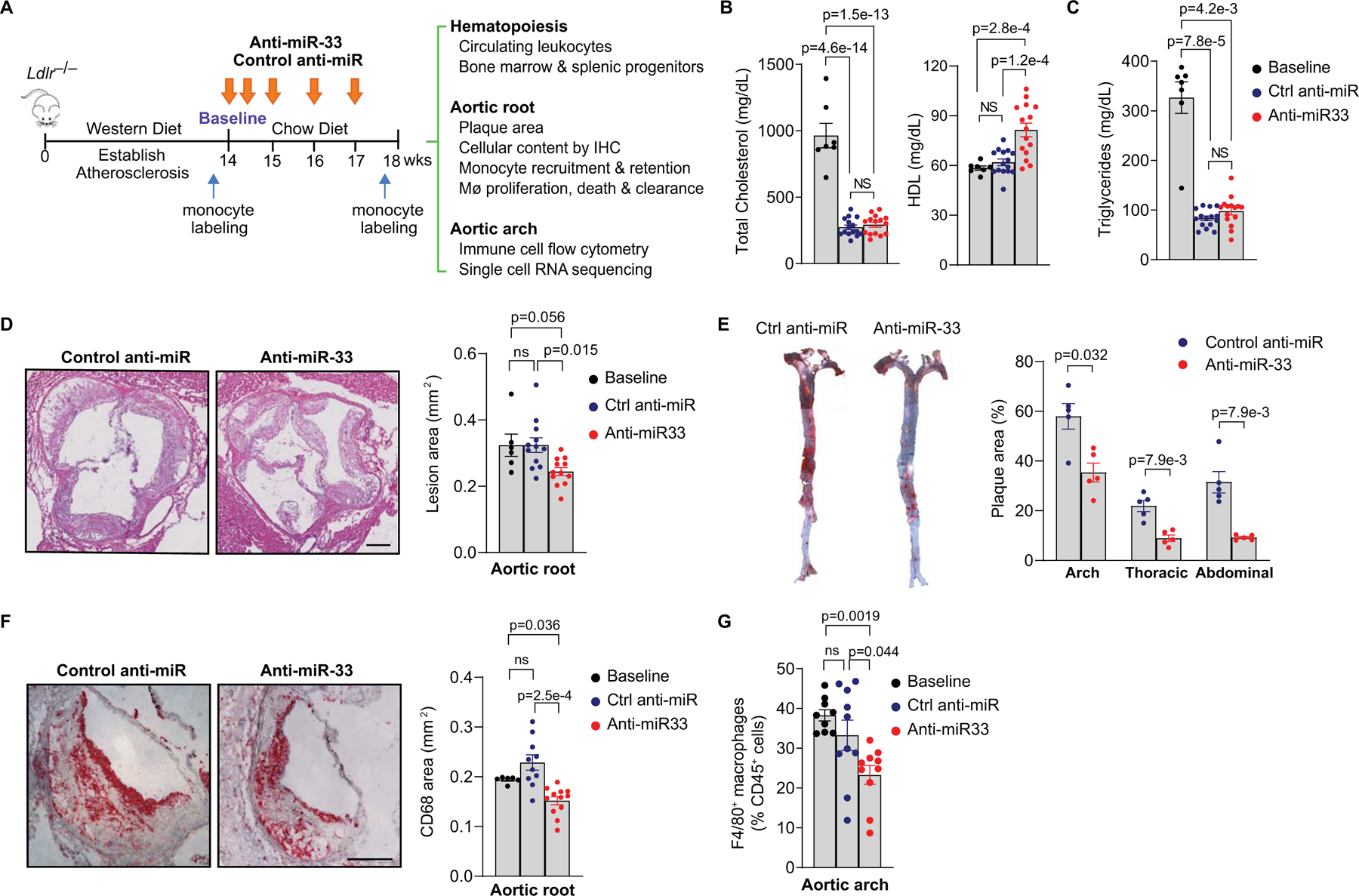

To understand how the inhibition of miR-33 alters atherosclerotic inflammation, we fed Ldlr−/− mice a western diet for 14 weeks to establish advanced plaques, then switched the mice to chow diet to halt atherosclerosis progression and treated with control anti-miR or anti-miR-33 oligonucleotides for 4 weeks (Figure 1A). This design was chosen to most closely resemble the clinical scenario of therapeutic inhibition of miR-33 in hyperlipidemic patients managed with statins or other lipid lowering therapies. As expected, we observed a decrease in plasma levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides in atherosclerotic mice switched to chow diet, that was similar in both control and anti-miR-33 treated mice. Consistent with previous findings23, anti-miR-33 treatment increased plasma levels of HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), but not triglycerides, compared to control anti-miR (Figure 1B–C). Furthermore, anti-miR-33 regressed atherosclerotic plaque area by 25–30% in both the aortic root (Figure 1D) and the aortic arch (Figure 1E) compared with control anti-miR. A greater reduction of plaque burden by anti-miR-33 was observed in the abdominal and thoracic regions of the aorta (60–70%), where plaque progression is less advanced than in the aortic arch and thus, more easily regressed (Figure 1E). This was accompanied by a decrease in the macrophage content of plaques in anti-miR-33 treated mice, measured by CD68 staining of aortic root cross-sections (Figure 1F) and flow cytometric analysis of F4/80 staining of cells from the aortic arch (Figure 1G). To further understand how anti-miR-33 alters the immune cell repertoire of plaques, we analyzed RNA from the aortic arches of treated mice using the NanoString nCounter immune profiling panel that utilizes multiplex gene expression analysis of 770 genes covering both the adaptive and innate immune responses. This exploratory analysis showed that miR-33 inhibition altered levels of both innate and adaptive immune cell markers in plaques, compared to control anti-miR (Online Figure I). Among the genes decreased by anti-miR-33 were the macrophage markers Adgre1 (F4/80) and Cd14, as well as Lcn2 (lipocalin-2) and Spp1 (osteopontin), inflammatory mediators that are associated with increased risk and severity of coronary artery disease in humans35–37. Among the genes increased by anti-miR-33 were the regulatory T cell marker Ikzf2 (Helios) and Il34 (Interleukin-34), which is a cytokine crucial for the maintenance of resident macrophage populations (Online Figure I). These results suggest that miR-33 inhibition alters both innate and adaptive immune responses in the plaque to promote atherosclerosis regression.

Figure 1. Inhibition of miR-33 induces atherosclerosis regression by reducing the plaque macrophage content.

A) Experimental outline: Atherosclerosis was established in Ldlr−/− mice by feeding a western diet for 14 weeks (baseline), after which mice were treated with control anti-miR or anti-miR-33 for 4 weeks on chow diet. Monocyte labeling was performed at baseline to macrophage retention, or 3 days prior to the end of the treatment period to assess monocyte recruitment. B-C) Plasma levels of (B) total cholesterol (TC) and HDL cholesterol and (C) triglycerides (TG), (n=7 baseline, 15 control anti-miR and 15 anti-miR-33). D-E) Quantification of atherosclerotic lesion area in (D) cross-sections of the aortic root (Scale bar = 250 μm) (n= 6 baseline, 12 control anti-miR and 12 anti-miR-33) and (E) the aorta en face (n= 5 mice/group). F-G) Quantification of plaque macrophage content measured by (F) CD68 immunostaining of the aortic root (Scale bar = 250 μm) (n= 6 baseline, 10 control anti-miR and 12 anti-miR-33) and (G) flow cytometric analysis of F4/80 in the aortic arch (n= 9 baseline, 10 control anti-miR and 10 anti-miR-33). Representative images were selected to represent the mean value of each condition. (B-G) Data are the mean ± S.E.M. P values were determined by (B, D) one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s test, (E) Mann-Whitney U-test or (C, F, G) Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc Dunn’s test.

Inhibition of miR-33 alters the transcriptomic landscape of aortic macrophages.

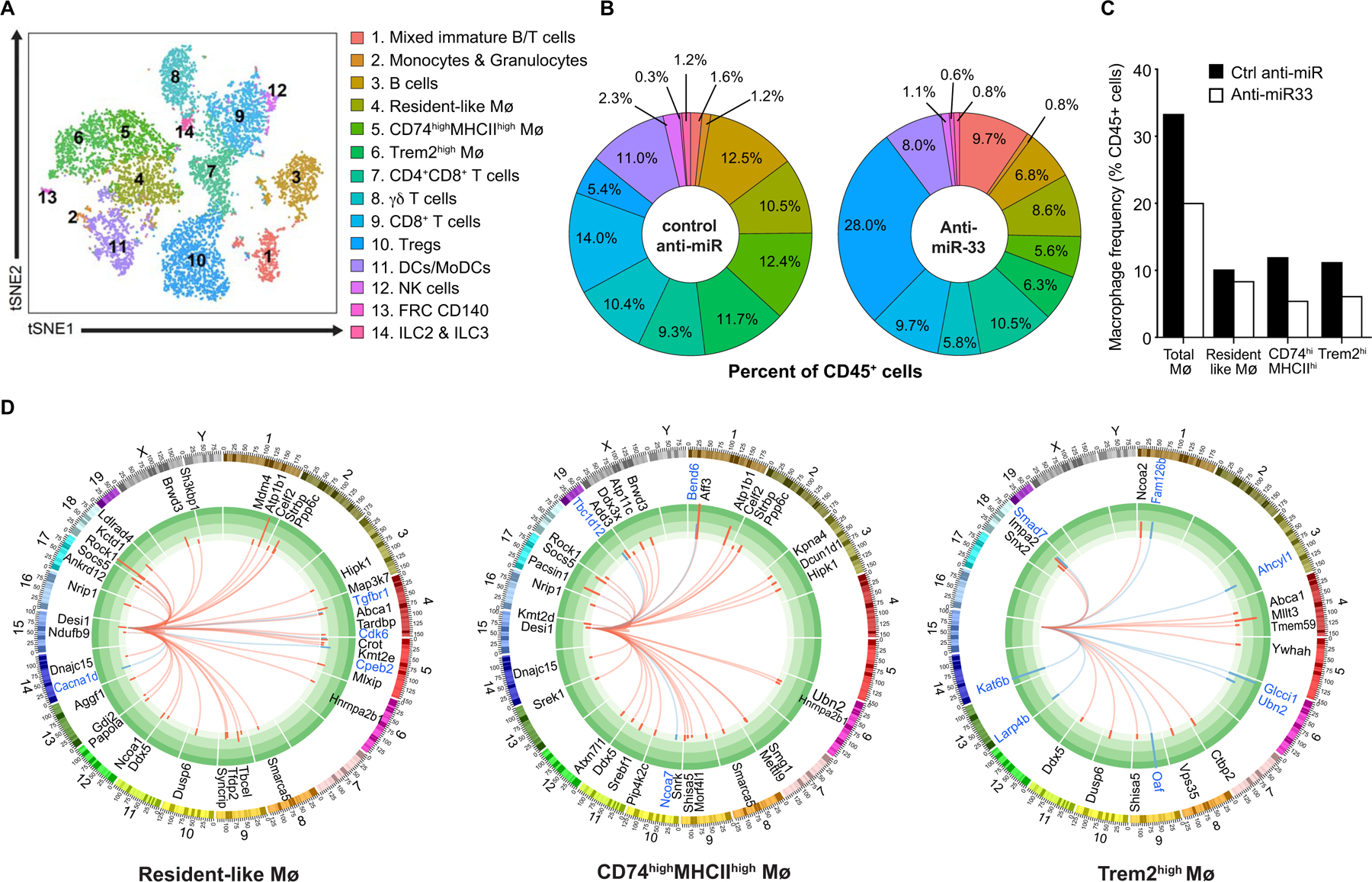

To further validate our targeted immune profiling analysis of aortic plaques, we isolated CD45+ cells from the aortic arches of mice treated with control anti-miR or anti-miR-33, and performed single cell (sc)RNA-sequencing. This technique allows greater discrimination of immune cell subpopulations based on individual cell transcriptomes. We analyzed 5480 and 6166 CD45+ cells from control anti-miR and anti-miR-33 treated mice (n=4 mice pooled per genotype), respectively, and performed unsupervised clustering and principal component analysis of the aggregated data to group cells with similar gene expression. This unbiased hierarchical clustering revealed 14 immune cell clusters in the atherosclerotic aortas, which were visualized using the multicore t-stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) algorithm (Figure 2A). Using SingleR, which leverages the ImmGen database to assign cells to their closest match in an unsupervised manner38, we identified 5 T cell, 3 macrophage, 1 natural killer (NK) cell, 1 innate lymphoid cell (ILC), 1 B cell, 1 monocyte/granulocyte, 1 dendritic cell (DC) and 1 mixed T/B cell cluster. The genes with the highest differential expression for each cluster is shown in Online Figure II, which showed concordance with published scRNA-sequencing datasets of immune cells from Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− mouse atherosclerotic plaques26, 29.

Figure 2. Single cell RNA-sequencing reveals that miR-33 inhibition alters the immune cell landscape in plaques.

A) t-Stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot showing clustering of aortic arch CD45+ cells based on gene expression. B) Immune cell frequencies in the aortic arches of mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. C) Frequency of the 3 macrophage clusters identified by single cell RNA-sequencing of CD45+ cells from the aortic arches of mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. D) Circos plots showing genome-wide differential expression of miR-33 target genes in each of the macrophage clusters. The inner track shows predicted miR-33 target genes that are upregulated (red arcs) or downregulated (blue arcs) in anti-miR-33 vs control anti-miR treatment. The outer track shows the chromosomal location of the miR-33 target genes. Data in A-D are from n=4 mice pooled/group; anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR.

Using canonical myeloid lineage markers such as Adgre1, Csf1r and Cd68 (Online Figure IIIA) we identified 3 macrophage clusters, including a resident-like cluster defined by high expression of Lyve1, F13a1 and Pf4 (cluster 4), a CD74hiMHCIIhi cluster defined by high expression of Cd74, H2.DMb1 and Il1b (cluster 5) and a Trem2hi cluster defined by high expression of Spp1, Trem2,and Ctsb (cluster 6) (Online Figure IIIB). Analysis of the cell frequencies in each cluster as a proportion of total CD45+ cells confirmed a marked decrease in aortic macrophage burden (−40%) in anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 2B, C). Notably, this contraction of the macrophage pool was due primarily to reductions in MHCIIhi “inflammatory” and Trem2hi “metabolic”, but not resident-like macrophages (Figure 2B, C). We also observed decreases in the frequencies of DCs, CD8+ T cells, NK cells and ILCs in the aortas of anti-miR-33 treated mice (Figure 2A, B). By contrast, we observed a 5-fold increase in the proportion of regulatory T cells in the aortas of mice treated with anti-miR-33 (Figure 2A, B), consistent with the increased expression of the regulatory T cell marker Ikzf2 detected by NanoString immune profiling of plaques (Figure 1G). Together, these changes in both the innate and adaptive immune cell composition in plaques suggest that anti-miR-33 dampens inflammation in the artery wall.

Next, to understand how miR-33 silencing altered the expression of miR-33 target genes in the various immune cell subsets, we cross-referenced the list of genes differentially expressed in anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR treated mice obtained by scRNA-seq with the list of predicted miR-33 target genes identified by Targetscan. Of the 14 immune cell clusters, we observed the highest number of derepressed miR-33 target mRNAs in plaque macrophages, followed by immature T/B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells (Figure 2D, Online Figure IV). By contrast, we observed little or no derepression of miR-33 target genes in monocytes, dendritic cells, ILCs, and NK cells (Online Fig IV). In resident-like and Trem2hi “metabolic” macrophages, we observed derepression of miR-33 target genes involved in lipid metabolism, such as the cholesterol transporter Abca1, and the steroid receptor co-activators Ncoa1 and Ncoa2 (also known as Src1/Src2) that interact with nuclear hormone receptor (e.g., LXR, FXR and PPARγ) regulators of lipid homeostasis39 (Figure 2D). Trem2hi macrophages from anti-miR-33 treated mice also showed upregulation of miR-33 target genes involved in protein sorting in the trans-Golgi network, endosome, and/or lysosome compartments, including Snx2, Vps35, and Tmem59, which maintain cellular homeostasis (Figure 2D). Resident-like and MHCIIhi inflammatory macrophages showed derepression of a common subset of miR-33 target genes, including Atp1b1, Brwd3, Ddx5, Desi1, Dnajc15, Hipk1, Hnrnpa2b1, Nrip1, Ppp6c, Rock1, Smarca5, Socs5, and Strbp (Figure 2D), many of which were also upregulated in plaque B and T cell subsets of mice treated with anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR (Online Figure IV). Interestingly, several of these miR-33 target genes have functions in regulating chromatin structure and/or transcriptional activation (e.g., Brwd3, Ddx5, Hipk1, Nrip1, Smarca5) that could promote broad transcriptional changes.

Differential target gene derepression in distinct cell clusters by anti-miR-33 may be due to a number of factors, including the endogenous levels of miR-33, phagocytic ability, target mRNA abundance, and RNA binding proteins. Indeed, transcription of miR-33 has been shown to be co-regulated with that of its host gene Srebf2, and we found that expression of Srebf2 varied by immune cell cluster. Among the macrophage clusters, we observed the highest level of Srebf2 mRNA in the resident-like macrophages which had the highest number of derepressed miR-33 target genes, and correspondingly, the lowest Srebf2 expression in Trem2hi macrophages, which had the fewest derepressed miR-33 target genes (Online Fig V, Figure 2D).

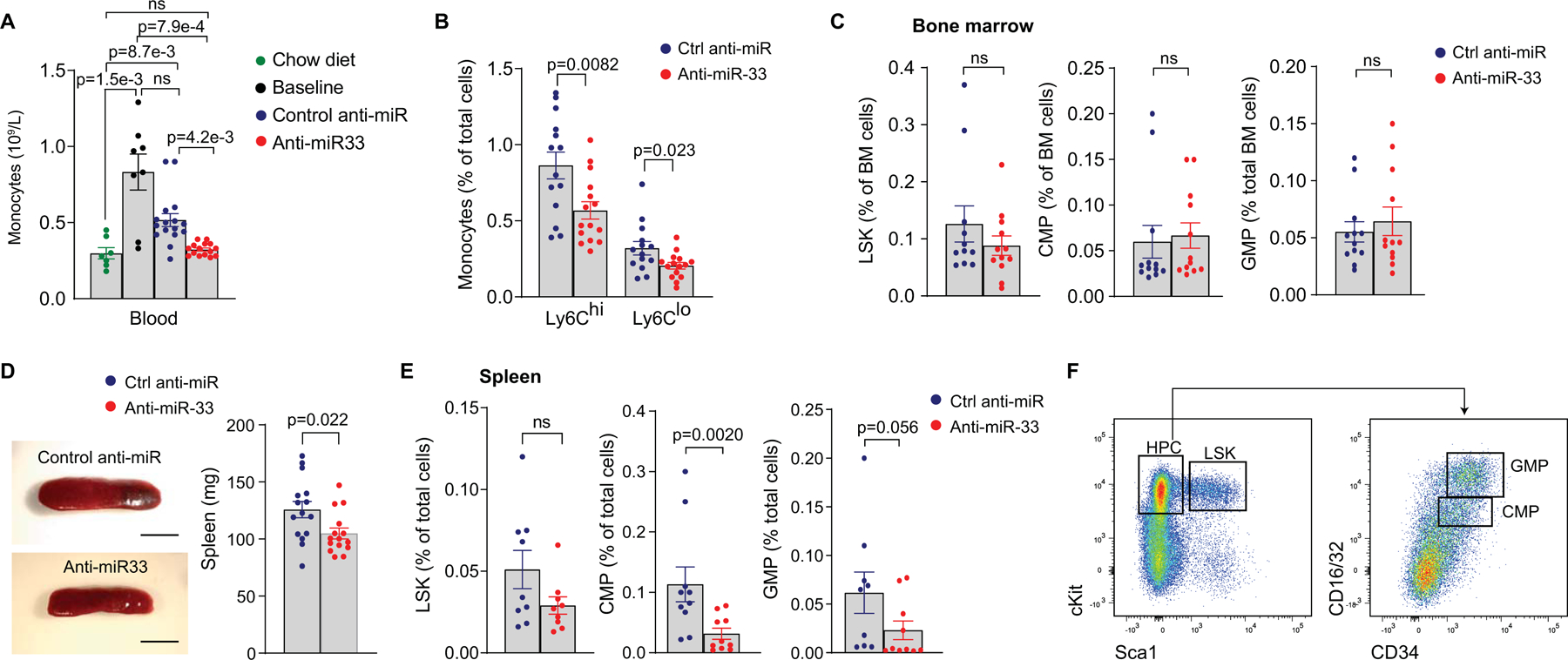

Inhibition of miR-33 reduces monocytosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen.

As our scRNA-seq analyses suggested that the anti-miR-33-induced contraction of plaque macrophage burden stemmed from reductions in monocyte-derived macrophage subpopulations, we next quantified the kinetic processes that determine the size of the macrophage pool in plaques (e.g., monocyte recruitment and macrophage proliferation, retention, and death). Consistent with studies showing that hypercholesterolemic mice exhibit monocytosis5, we found that Ldlr–/– mice fed a western diet had a 3-fold increase in circulating monocytes compared to Ldlr–/– mice fed a chow diet (Figure 3A). In atherosclerotic Ldlr–/– mice switched to chow diet and treated with control anti-miR, this monocytosis was decreased by 50%, whereas mice treated with anti-miR-33 showed complete reversal of monocytosis to control levels (Figure 3A). Anti-miR33 treatment decreased both Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytes in the blood of atherosclerotic Ldlr–/– mice (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, we observed no differences in the levels of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the bone marrow of anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 3C). However, mice treated with anti-miR-33 showed a decrease in spleen size and common myeloid and granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells in the spleen (Figure 3D–F), which has been shown to be an important monocyte reservoir for recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques40, 41.

Figure 3. Inhibition of miR-33 decreases monocytosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen.

A) Blood levels of monocytes in Ldlr−/− mice fed chow diet, western diet for 14 weeks (Baseline), or after treatment with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR for 4 weeks. n=7 chow diet, 8 baseline, 16 control anti-miR, 15 anti-miR-33. B) Flow cytometric analysis of Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytes in the blood of atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 (n=15) or control anti-miR (n=14). C) Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations (LSK, Lin–Sca+Kit– cells; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; GMP, granulocyte-myeloid progenitor, n=12 mice/group). D) Representative images and spleen weights from Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. n=15 mice/group. Scale 5 mm. E) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell populations. n=9 control anti-miR and 10 anti-miR-33. F) Flow cytometry gating strategy for LSK, CMP and GMP cells in the bone marrow and spleen. Data in A-E are the mean ± SEM. P values were determined by Kruskal-Wallis with post-hoc Dunn’s test (A), Student’s t-test (B) or Mann-Whitney’s test (C-E). ns=not significant.

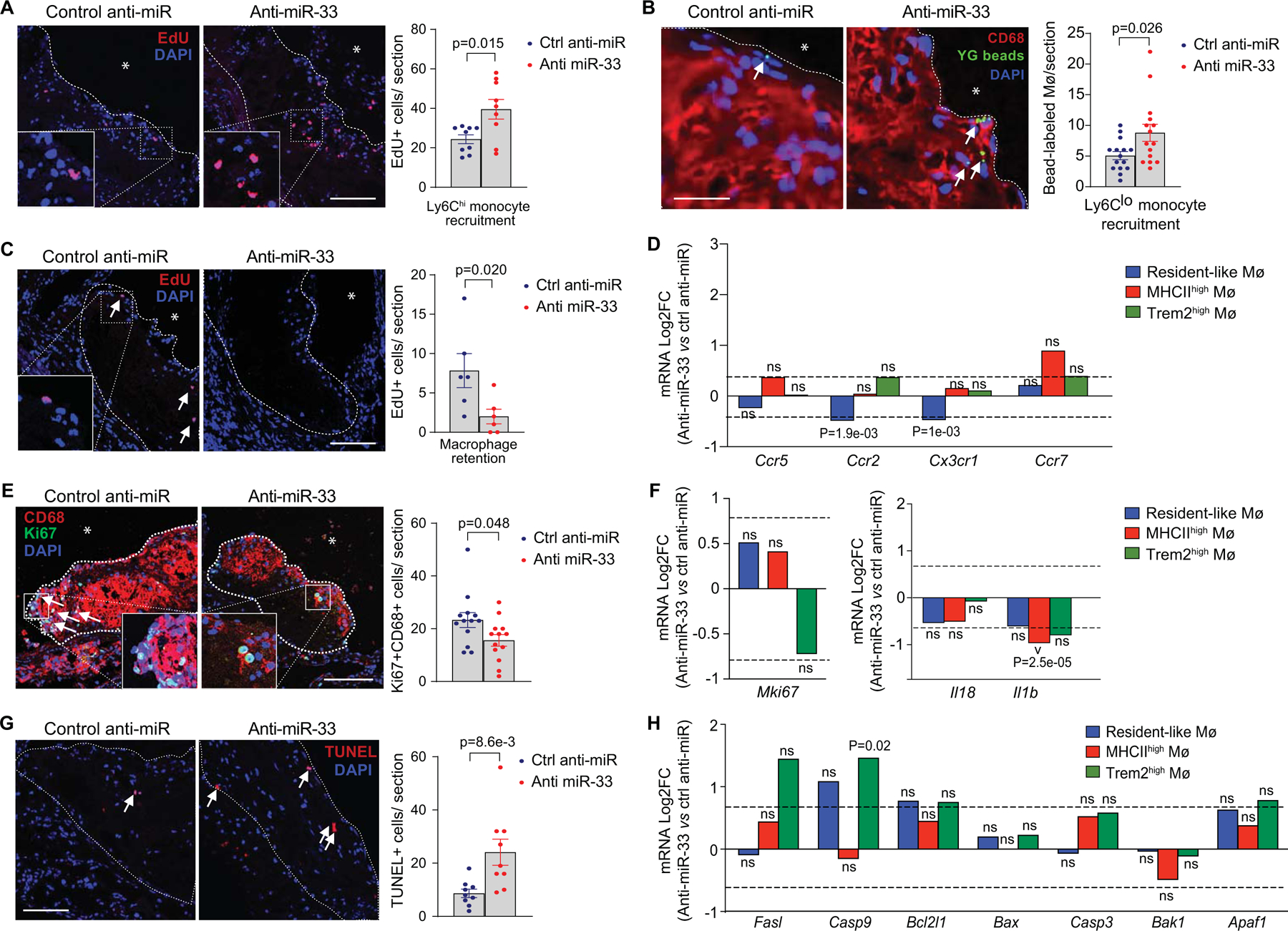

We next quantified monocyte recruitment and traced the fate of monocyte-derived macrophages in plaques of anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR treated mice. We labeled Ly6Clow and Ly6Chigh monocytes using fluorescent beads and pulse labeling with EdU, respectively34, 3 days prior to the end of anti-miR treatment period and quantified the number of labelled monocyte-derived macrophages in cross-sections of the aortic root at sacrifice by fluorescence microscopy. Despite a decrease in circulating monocyte levels in anti-miR-33 treated mice, we observed higher numbers of labelled Ly6Clo and Ly6hi monocytes recruited into plaques of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 4A, B), consistent with previous findings that Ly6Chi monocytes are required for atherosclerosis regression42.

Fig 4. Inhibition of miR-33 alters monocyte-macrophage dynamics in the plaque.

A-B) Representative images and quantification of (A) Edu-labeled Ly6Chi (n=9 mice/group, scale= 100 μm) and (B) fluorescent bead-labeled Ly6Clo (n = 15 mice/group, scale = 10 μm) monocytes recruited into aortic root plaques of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. C) Representative images and quantification of Ly6Chi monocyte-derived macrophages (Edu+) retained in aortic root plaques after 4 weeks of anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR treatment. Scale bar = 100 μm (n = 6/group). D) Fold change in RNA-seq reads of genes involved in macrophage migration and retention in anti-miR33 vs control anti-miR treated mice by macrophage clusters. E) Representative images and quantification of immunostaining for the proliferation marker Ki67 and the macrophage marker CD68 in aortic root plaques of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. Scale bar = 100 μm (n=13/group). F) Fold change in RNA-seq reads of proliferation and inflammatory genes in anti-miR-33 versus control anti-miR treated mice within the indicated aortic macrophage populations. G) Representative images and quantification of the apoptotic cell marker TUNEL in aortic root plaques of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. (n=9 mice/group, scale = 100 μm). H) Fold change in RNA-seq reads of cell death-related genes in anti-miR33 vs control anti-miR treated mice by macrophage clusters (n=4 pooled mice/group in scRNA-seq). P values were determined by Mann-Whitney’s test (A, B, C, E) or by Student’s t-test (D, F, G, H). P values in D, F and H are unadjusted and represent significantly different gene expression presented in Log2FC for anti-miR-33 as compared to control anti-miR treatment in the indicated macrophage cluster. ns=not significant.

To assess whether monocyte-derived macrophages are retained in plaques, Ly6Chi monocytes were labelled in atherosclerotic Ldlr–/– mice at baseline, and the number of labelled monocyte-derived macrophages remaining in plaques at the end of the treatment period was assessed in aortic root cross-sections. Compared to control anti-miR, anti-miR-33 treated mice showed a 75% reduction in labeled monocyte-derived macrophages retained in plaques (Figure 4C). Analysis of migratory factors differentially expressed in macrophage subsets after anti-miR-33 treatment showed that MHCIIhi “inflammatory” macrophages had a 2-fold increase in expression of the chemokine receptor Ccr7, which directs macrophage emigration from the artery wall43, 44, however this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4D). Resident-like macrophages from anti-miR-33 treated mice had significant reductions in the chemokine receptor genes Ccr2 and Cx3cr1 (Figure 4D). By contrast, we observed little change in expression of migratory factors in the Trem2hi macrophage population (Figure 4D; Online Fig VI).

To assess the contributions of macrophage proliferation and death to the plaque macrophage content, we performed immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 and TUNEL. We observed a 30% decrease in Ki67+CD68+ cells in aortic root plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice (Figure 4E), which correlated with a 40% reduction in Mki67 expression in the Trem2hi macrophage population (Figure 4F; Online Fig VI). We observed a 2.5-fold increase TUNEL+ cells in plaques of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 4G), which was associated with increased expression of the pro-apoptotic genes Casp9, Fasl, and Apaf1 in the Trem2hi macrophage population (Figure 4H; Online Fig VI). By comparison, we observed significantly reduced expression of the pro-atherosclerotic cytokine interleukin-1β (Il1b) in the MHCIIhi macrophage subset in plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice, and similar trends were observed in resident-like and Trem2hi macrophage populations after anti-miR-33 treatment (Figure 4F; Online Fig VI). Together, these data suggest that anti-miR-33 decreases the macrophage content of plaques by altering the balance of macrophage proliferation, retention and death, and point to specific contributions of macrophage subpopulations in these processes.

miR-33 silencing increases efferocytosis and the accumulation of tissue-reparative macrophages.

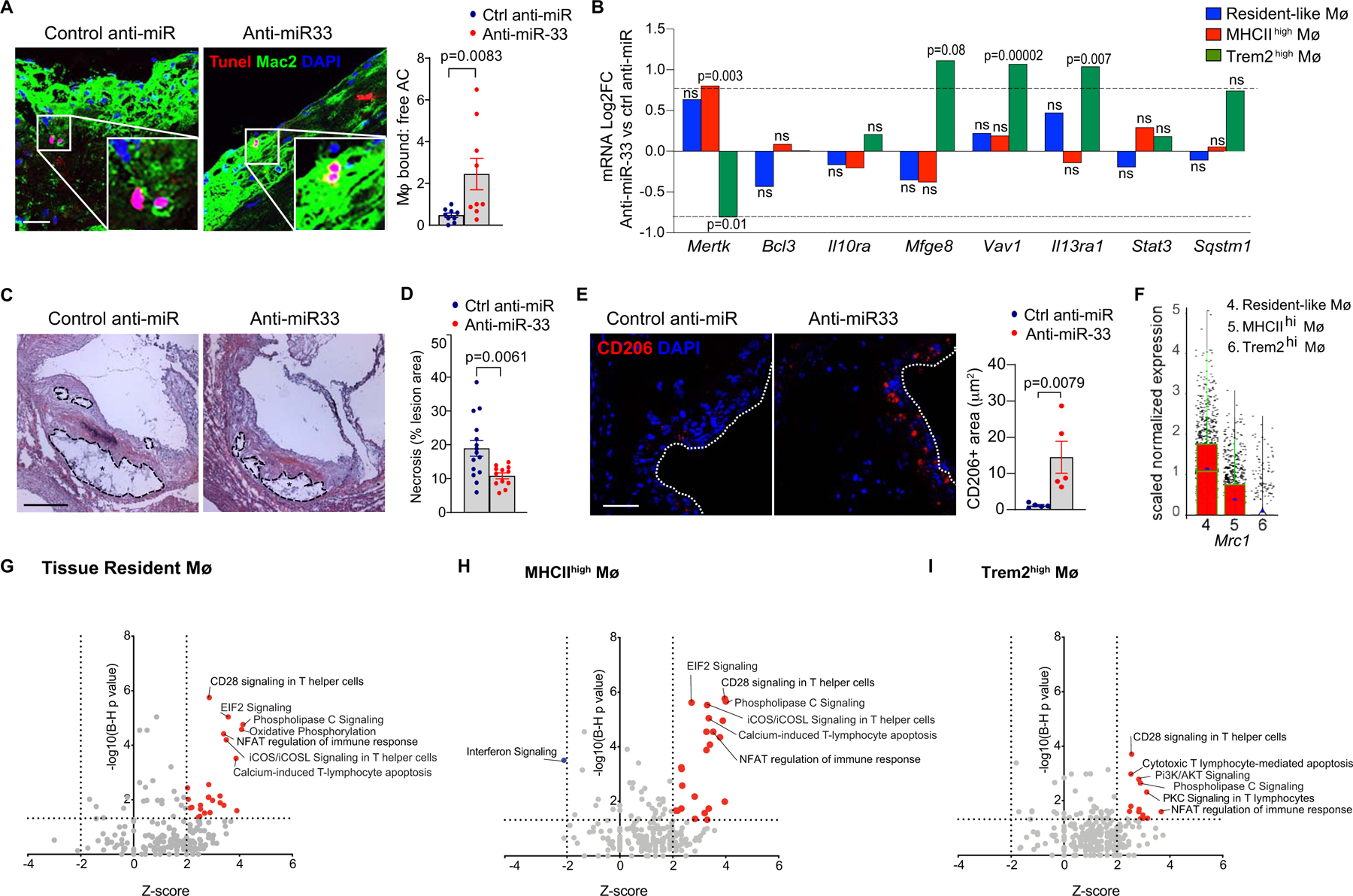

The clearance of apoptotic cells is essential for tissue homeostasis and repair. This process, known as efferocytosis, becomes defective in advanced atherosclerotic plaques, resulting in post-apoptotic necrosis, inflammation and formation of a necrotic core 45. We previously showed that miR-33 inhibition can promote efferocytosis in vitro, in part by enhancing autophagy15. Co-staining of plaques for TUNEL and the macrophage marker Mac2 showed a 5-fold increase in macrophage-bound vs free apoptotic cells in plaques of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 5A), indicating that miR-33 silencing also increases efferocytosis in atherosclerotic plaques15. Interrogation of the scRNA-seq transcriptomes revealed a 2-fold increase in expression of the efferocytosis receptor Mertk in MHCIIhi inflammatory macrophages, as well as a non-significant increase (1.5-fold) in resident-like plaque macrophages of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 5B; Online Fig VI). Interestingly, we observed decreased expression of Mertk, alongside increased expression of the “eat-me” signal Mfge8, in Trem2hi macrophages of anti-miR-33 treated mice 46. Together with the increased expression of pro-apoptotic genes (Casp9, Fasl, and Apaf1) (Figure 4H), these data suggest that the Trem2hi macrophage population in plaques is reduced by programmed cell death in anti-miR-33 treated mice. Furthermore, they implicate MHCIIhi and resident-like macrophages in the enhanced efferocytotic clearance observed in anti-miR-33 treated mice. Consistent with our findings of increased efferocytosis, we observed a 50% decrease in necrotic area in aortic root plaques of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 5C, D). Together, these data suggest that miR-33 inhibition promotes macrophage processes that contribute to tissue repair and plaque contraction.

Figure 5. Inhibition of miR-33 promotes macrophage processes associated with plaque remodeling and repair.

A) Representative images of costaining for the apoptosis marker TUNEL and the macrophage marker Mac-2, and quantification of macrophage-bound and free apoptotic cells to determine efferocytosis in aortic root plaques of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR (n=9 mice/group, scale = 25 μm). B) Fold change in RNA-seq reads of efferocytosis-related genes in anti-miR33 vs control anti-miR treated mice by macrophage clusters. P values were determined by Student’s t-test and represent significantly different gene expression presented in Log2FC for anti-miR-33 as compared to control anti-miR treatment in the indicated macrophage cluster. C-D) Quantification of necrotic area in hematoxylin and eosin stained aortic root plaques of mice treated with control anti-miR or anti-miR-33. Representative images shown in D. Scale bar = 250 μm. n=15 control anti-miR and 12 anti-miR-33. E) Representative images and quantification of immunostaining for the M2 macrophage marker CD206 (Mrc1) in aortic root plaques of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. Scale bar = 25 μm. n=5 mice/group. Data in A, C, E are expressed as mean ± SEM. P values were determined by Mann-Whitney’s test (A, E) or Student’s t-test (D). F) Mrc1 expression in immune cells clusters identified by single cell RNA sequencing of aortic arch CD45+ cells (n=4 mice/group pooled). G-I) Top enriched canonical pathways in aortic macrophage clusters of anti-miR-33 vs control anti-miR treated mice. Significant pathways were identified based on a 5% false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (B-H p-value <0.05) within the Canonical Pathways annotations by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Activated canonical pathways (Z score >2) are indicated by red filled dots, while inhibited pathways (Z-score <−2) are indicated by blue filled dots. Key pathways of interest are annotated. ns=not significant.

miR-33 inhibition promotes the accumulation of pro-resolving M2-like macrophages and Tregs in plaques.

Recent studies from our lab and others have established essential roles for M2-like macrophages and regulatory T cells in facilitating tissue repair and inflammation resolution during atherosclerosis regression47–50. Alternatively activated M2 macrophages efficiently clear apoptotic cells and promote the differentiation and maintenance of inflammation-dampening regulatory T cells by secreting retinoic acid, IL-10 and TGF-β51, 52. In turn, regulatory T cells promote alternative activation of macrophages and enhance efferocytosis through their secretion of IL-1353. We previously showed that miR-33 inhibition can promote alternative activation of macrophages and increased expression of the M2 markers mannose receptor/CD206 (Mrc1) and arginase (Arg1), in part by upregulating oxidative phosphorylation15. Consistent with this, anti-miR-33 treated mice showed a 10-fold increase in mannose receptor positive cells in the plaque, compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 5E). We interrogated our scRNA-seq to understand which plaque macrophage subsets contribute to this signature of alternative activation, and found that Mrc1 (Figure 5F), as well as the other M2 markers Retnla (Fizz1) and Aldh1a2 (Online Fig. IV), were most highly expressed in the resident-like macrophage subset. By contrast, Arg1 was broadly expressed (Figure 5F, Online Figure V). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of differentially expressed genes in anti-miR33 versus control anti-miR treated mice identified oxidative phosphorylation as a biological process upregulated in resident-like, but not MHCIIhi or Trem2hi macrophages (Figure 5G). These data suggest that anti-miR-33’s effects on macrophage oxidative respiration and M2-like polarization16, 24, 54 occur predominantly in the resident-like macrophage population in plaques. Finally, interferon (IFN) signaling, which is thought to be pro-atherosclerotic by activating macrophages to an M1-like phenotype and enhancing antigen presentation55, was significantly reduced by anti-miR-33 in MHCIIhi macrophages (Figure 5H).

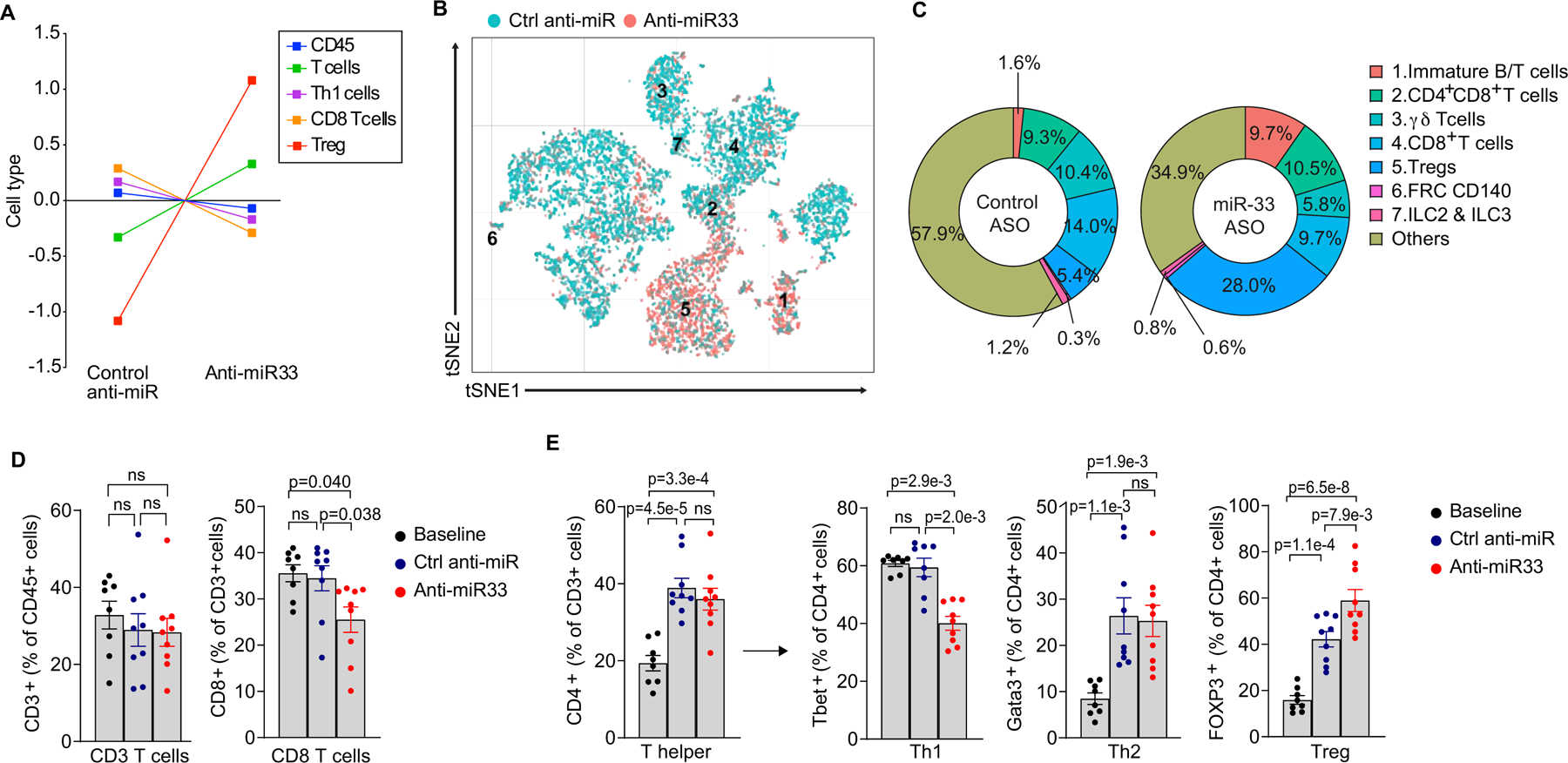

Pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes in anti-miR33 versus control anti-miR treated mice showed that phospholipase C signaling, NFAT signaling in the immune response, CD28 signaling in T helper cells, and ICOS-ICOSL signaling in T helper cells was upregulated in all 3 macrophage subsets (Figure 5G, Online Figure VII). The latter two pathways are notable for their roles in co-stimulation of T helper cells, which is essential for induction of adaptive immune responses. In particular, ICOS signaling has been shown to support the proliferative potential and suppressive capabilities of regulatory T cells56, and is required to maintain FoxP3+ cells in atherosclerotic plaques57. To understand how miR-33 silencing affects the T cell repertoire in plaques, we first analyzed the transcriptomic immune cell signature of aortic arch plaques using the NanoString nCounter immune profiling panel. This immune deconvolution analysis, which predicts immune cell abundance from bulk RNA transcriptomic analysis, showed enrichment of gene sets for regulatory T cells and reduction of gene sets for Th1 and CD8+ T cells in aortas of anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 6A). These findings were confirmed by scRNA-sequencing of aortic CD45+ cells, which showed an expansion of Treg and a contraction of CD8+ T cell populations in anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR treated mice (Figure 6B–D). Interestingly, we also observed an increase in the frequency of immature B/T cells in aortas of anti-miR-33 treated mice (Figure 6C). As scRNA-seq is not optimal for discriminating all T cell subsets, we performed flow cytometry analysis of the aortic arches of anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR treated mice, which confirmed that miR-33 silencing reduced CD8+ T cells and increased Tregs in aortic plaques (Figure 6D). Moreover, we found that anti-miR-33 treatment reduced CD4+ Th1 cells in aortic plaques, consistent with the ability of Tregs to suppress these effector T cell populations (Figure 6D–E). By contrast, we observed no difference in CD4+ Th2 cells in anti-miR-33 and control anti-miR treated mice. Together, these data suggest that anti-miR-33 treatment alters the balance of pro-atherosclerotic (i.e., CD8+, CD4+ Th1) and anti-atherosclerotic (i.e., Treg) T cells in the plaque.

Figure 6. Inhibition of miR-33 alters the T cell balance in atherosclerotic plaques to promote inflammation resolution.

A) NanoString immune profiling gene set analysis of RNA from aortic arches of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR (n=6 mice/group). B) t-Stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) plot showing clustering of T cells from the aortic arch of Ldlr−/− mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR based on gene expression. n=4 mice pooled/group. C) Frequencies of the T cell clusters identified by single cell RNA-sequencing of CD45+ cells from the aortic arches of mice treated with anti-miR-33 or control anti-miR. D-E) Flow cytometric analysis of CD8+ and CD3+ T cells (D), and CD4+ T helper cell subsets (E) in aortic arches of mice treated with control anti-miR or anti-miR-33 (n=8 baseline, 9 control anti-miR and 9 anti-miR33). Data in D-E are presented as mean ± S.E.M. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test for T cells, T helper cells and regulatory T cells or Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s test for Th1, Th2 and CD8 T cells. ns=not significant.

To address the clinical relevance of our findings, we analyzed the recent scRNA-seq of CD45+ cells isolated from aortas of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients performed by Fernandez et al27 to determine whether the human orthologs of the miR-33 target genes that were de-repressed in macrophages in regressing plaques were enriched in macrophages from asymptomatic compared to symptomatic plaques in humans. When we performed a concordance analysis, we found that 16 of the 24 miR-33 target genes whose expression was increased in plaque macrophages following inhibition of miR-33 showed higher expression in the asymptomatic plaques than the symptomatic plaques (Online Fig VIII). Simulations showed that this would occur by chance in 7 of 10,000 permutation tests These data suggest that miR-33 target gene repression correlates with plaque progression and symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

DISCUSSION

Targeted inhibition of miR-33 has been proposed as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease23–25. The atheroprotective functions of miR-33 inhibitors have been attributed, in part, to effects in plaque macrophages and other hematopoietic cells15, 24, 58, but the underlying mechanisms have been incompletely understood. Using scRNA-Seq, monocyte tracing, histological staining and flow cytometry we generated a high-resolution map of the immune cell compartment of plaques in atherosclerotic mice following treatment with a miR-33 inhibitor. This comprehensive analysis revealed the breadth of miR-33 target genes derepressed in the distinct immune cell subsets in the plaque, and how these immune cell subpopulations shift in phenotype and frequency to enable regression with anti-miR-33 treatment. Using plaque macrophage populations as an exemplar, we showed how the inhibition of miR-33 affects common and distinct target genes in each of the macrophage subsets in plaques, including resident, Trem2hi and MHCIIhi macrophages. Moreover, we correlate the transcriptomic changes in each of these subsets with measured changes in macrophage kinetic processes to show how miR-33 silencing alters the proliferation, retention, death and efferocytosis of the macrophage subsets in the plaque to support inflammation resolution. These findings enhance our understanding of the effects of miR-33 inhibition on plaque immune cells, particularly macrophages, and illustrate how incorporating single-cell technologies with conventional atherosclerosis analyses can provide additional insight into how therapeutic interventions, such as anti-miR-33, mediate atherosclerosis regression.

The recent application of single cell technologies to the study of atherosclerosis has unveiled remarkable heterogeneity of plaque immune cells and introduced new classifications based on transcriptionally distinct sub-populations26, 28, 29. However, connecting this transcriptional heterogeneity to functional phenotypes and in vivo cell behaviors is a new challenge in understanding the multi-faceted roles of immune cells in atherosclerosis. This is particularly true of plaque macrophages, where scRNA-seq has identified multiple new macrophage subsets that cannot be distinguished using conventional protein markers such as CD68, F4/80 and Mac-2 (Lgals3), or markers of macrophages polarized in vitro to M1 or M2 states (e.g., Arg1, MRC1/CD206, Fizz1/Renla). Using a multi-pronged approach of scRNA-seq, flow cytometry and monocyte tracing and immunostaining, we attempted to connect transcriptional changes induced during miR-33 inhibition with distinct macrophage subsets and their functional behaviors.

Macrophages are among the cell types most readily targeted by ASOs by virtue of their phagocytic nature, and among the macrophage clusters we observed the highest number of derepressed miR-33 target mRNAs in resident-like > MHCIIhi > Trem2hi macrophages, which correlated with their level of expression of the miR-33 host gene Srebf2. By virtue of their identification using Louvain clustering, each macrophage cluster shares a common transcriptional profile that is distinct from all other clusters and may vary in their levels of miR-33 target mRNAs, and likely miR-33 itself, as suggested by their expression of Srebf2. These factors would be expected to lead to different responses to miR-33 inhibition among the different macrophage clusters. Indeed, we show that Abca1, a prominent miR-33 target gene involved in cholesterol efflux10–12, was upregulated primarily in resident-like and Trem2hi metabolic macrophage subsets, but not MHCIIhi inflammatory macrophages or other immune cell subsets in anti-miR-33 treated mice. These two macrophage populations also showed derepression of co-regulators of nuclear hormone receptors (i.e., Ncoa1, Ncoa2) involved in sterol regulation, suggesting that miR-33 silencing in resident-like and Trem2hi macrophage subpopulations alters lipid metabolism. We also noted upregulation in Trem2hi macrophages of miR-33 target genes involved in cargo sorting in endosomal and lysosomal compartments (Snx2, Vps35, and Tmem59), which may facilitate intracellular lipid trafficking and endolysosomal functions critical to cholesterol metabolism, consistent with the specialized lipid metabolism functions of this macrophage subset26, 59.

Resident-like macrophages from anti-miR-33 treated mice exhibited a gene expression signature consistent with increased oxidative phosphorylation, including upregulation of the miR-33 target gene Crot17, which critically regulates transport of medium chain fatty acids from peroxisomes to the cytosol and mitochondria for breakdown. We previously reported that miR-33 silencing in macrophages increases β-oxidation of fatty acids, and this shift in metabolic programming preceded macrophage polarization to an alternatively activated or M2 state24. Indeed, we observed increased staining for the M2 macrophage marker MRC1 in plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice, which correlated with high expression of the M2 associated genes Mrc1, Aldh1a2, and Retnla in the resident-like macrophage subset. M2 macrophages have tissue reparative and inflammation-resolving functions, including an enhanced ability to clear apoptotic cells. Accordingly, we noted an increase in macrophage efferocytotic capacity and a decrease in necrotic area in plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice. The increase in efferocytotic capacity after anti-miR-33 treatment is likely to be shared by both resident-like and MHCIIhi macrophage populations in the plaque, as these subsets showed increased expression of the apoptotic cell receptor Mertk, which is essential for efferocytotic clearance in plaques60.

Additional links between specific miR-33 target genes and functional changes in the MHCIIhi macrophage subpopulation were difficult to ascribe. Among the predicted miR-33 target genes that were upregulated in plaque MHCIIhi macrophages of anti-miR-33 treated mice, we noted several involved in chromatin remodeling and/or transcriptional activation, such as Brwd3, Ddx5, Hipk1, Nrip1, and Smarca5. Interestingly, several of these target genes were also upregulated in plaque B and T cell subsets of mice treated with anti-miR-33 compared to control anti-miR. Derepression of these target genes by anti-miR-33 would be predicted to lead to broad downstream changes in transcription by altering chromatin architecture and facilitating transcriptional activation of non-miR-33 target genes. Although these miR-33 target genes remain to be further validated, and the actions of anti-miR-33 in T and B cells confirmed, these data suggest a mechanism through which miR-33 could broadly regulate immune cell function by altering the epigenetic landscape. Together, these data show that miR-33 targeting leads to derepression of both common and distinct gene targets in different immune cell subsets in the plaque. This is likely due to a combination of factors, including the target cell’s endogenous levels of miR-33, the efficiency of ASO uptake, miR-33 target mRNA abundance in the cell, as well as trans-factors affecting miRNA targeting in different cell types, such as expression of RNA binding proteins, other miRNAs and competing endogenous RNAs. Notably, we observed that the human orthologs of miR-33 target genes de-repressed in plaque macrophages after anti-miR-33 treatment were enriched in macrophages from asymptomatic compared to symptomatic plaques in humans. Concordance analysis showed that 75% of miR-33 target genes increased in plaque macrophages following miR-33 inhibition showed higher expression in asymptomatic human plaques compared to symptomatic human plaques suggesting that repression of miR-33 target genes correlates with plaque progression and symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

In addition to its effects on the distinct macrophage subsets of the plaques, anti-miR-33 also had potent effects on levels of circulating monocytes and their progenitors in the spleen. In atherosclerosis, hypercholesterolemia and inflammatory signals induce proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and promote myelopoiesis4, 5. In mice, hematopoietic progenitor cells also mobilize from the bone marrow to secondary lymphoid organs such as spleen, where they serve as a reservoir for monocytes recruited to plaques41, 61. Anti-miR-33 treated mice had noticeably smaller spleens upon visual inspection, and this was associated with a decrease in the number of splenic myeloid progenitor cells, including CMPs and GMPs. The miR-33 target genes Abca1 and Abcg1 play critical roles in regulating hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation and extramedullary hematopoiesis, by modulating intracellular cholesterol levels62. Previous studies from our group showed that inhibition of miR-33 decreased hyperglycemia-induced monocytosis and proliferation of CMP and GMPs in the bone marrow by upregulation of Abca131. In the current study we did not observe differences in bone marrow progenitors of anti-miR-33 treated mice, which may relate to differences in the models used. Consistent with the reduced splenic myeloid progenitor cell pool, we found that mice treated with anti-miR-33 had lower levels of both Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytes in the circulation than control anti-miR treated mice. Indeed, treating atherosclerotic mice with anti-miR-33 reduced blood monocyte levels to those observed in chow diet fed mice. As elevated monocyte levels are associated with increased CVD risk in humans and progression of atherosclerosis in mouse models, the ability of anti-miR-33 to reduce levels of monocytes and their progenitors likely contributes to its inflammation-dampening actions.

Surprisingly, the reduction in monocytosis observed in anti-miR-33-treated mice did not correlate with decreased monocyte recruitment in atherosclerotic plaques. Rather, monocyte tracing studies showed an increase in the recruitment of Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo monocytes into aortic root plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice. While initially somewhat counterintuitive, these findings are consistent with our recent report that Ly6Chi monocytes recruited into plaques are a source of tissue reparative M2 macrophages that are required to enact atherosclerosis regression42. While that study showed that recruitment of Ly6Clo monocytes is not essential for atherosclerosis regression42, these patrolling monocytes have been associated with wound healing and inflammation resolution through their removal of damaged cells and debris from the vasculature63. Furthermore, we found that treatment with anti-miR-33 decreased macrophage proliferation in the aorta, which was associated with reduced expression of the proliferation marker Mki67 in the Trem2hi macrophage population. Trem2hi macrophages from anti-miR-33 treated mice also exhibited increased expression of genes involved in apoptosis and “eat me” signaling, suggesting that their contraction during inflammation resolution may derive from both reduced proliferation and increased programmed cell death. While expression of markers of proliferation and apoptosis were not significantly changed in MHCIIhi macrophages after anti-miR-33 treatment, we observed increased expression of the chemokine receptor Ccr7 which has been linked to macrophage emigration from plaques to the draining lymph nodes44, 64. These findings suggest distinct effects of anti-miR-33 on resident-like, MHCIIhi and Trem2hi macrophage populations that result in a net reduction in macrophage burden in the aorta and plaque contraction.

miR-33 inhibition in atherosclerotic mice also promoted changes in adaptive immune cell populations in the plaque. Most prominent was an expansion of immune dampening Tregs in plaques of anti-miR-33 treated mice, which was detected by flow cytometry analysis, Nanostring profiling and scRNA-seq. Tregs are known to be atheroprotective in humans and mice65–67, and their enrichment in plaques is essential for regression47. Consistent with Treg suppression of pro-inflammatory T cell responses in anti-miR-33 treated mice, we observed a decrease in plaque CD4+ Th1 and CD8+ T cells. Depletion of these pro-atherogenic T cell subsets in mice is associated with reduced plaque progression68, 69 and in the case of CD8+ T cell depletion, reduced monocytosis70. The altered balance in plaque T cells in anti-miR-33 treated mice likely results from both T cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic effects. Downregulation of miR-33 after CD28 priming of naïve T cells increases mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and enhance the spare respiratory capacity needed for a rapid response to restimulation and long-lasting effects in memory T cells71. Furthermore, inhibition of miR-33 would reinforce the high rate of oxidative phosphorylation in FoxP3+ Tregs, which is essential to their immunosuppressive capacity72. Alternatively, miR-33 inhibition in macrophages may indirectly foster Tregs in plaques by expanding the population of M2-like macrophages, which secrete Treg sustaining factors such as retinoic acid, IL-10 and TGF-β 51, 52. Indeed, we previously showed in vitro that miR-33 inhibition increases macrophage expression of the retinoic acid–producing enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1, subfamily A2 (Aldh1a2), and promotes Treg differentiation in co-culture assays 24. Notably, plaque macrophages of anti-miR33 treated mice showed increased ICOS signaling, which is required to both maintain FoxP3+ Treg cells in plaques57 and support their suppressive functions56. Taken together, our data suggest that anti-miR-33 targeting of both innate and adaptive immune cell responses contributes to inflammation resolution in plaques.

In summary, our work illustrates how incorporating single-cell technologies with conventional atherosclerosis analyses can provide additional insight into how therapeutic interventions, such as anti-miR-33, mediate their effects on disease resolution. Whereas traditional RNAseq methods provides the average gene expression of many cells, scRNAseq allows a more refined understanding of the effect of interventions on specific cell subpopulations, heterogeneity among individual cells, and regulatory relationships between genes. ScRNAseq of aortic CD45+ cells from pooled mice, as we have done here, provides a powerful approach for the analysis of variation in expression of individual genes across >5400 cells for each condition. We demonstrate that the inhibition of miR-33 induces atherosclerosis regression by altering the balance and the transcriptional landscape of cells involved in innate and adaptive immunity. While some of these actions can be attributed to effects on expression of target genes that alter cellular metabolic programs to dampen inflammation (e.g., improved cholesterol efflux likely underlies reductions in CMP and GMP levels in spleen, and increased fatty acid oxidation promotes M2 macrophage polarization), other associated changes are likely downstream of these effects (e.g., the enrichment in plaque M2 macrophages can induce Treg differentiation and increase efferocytosis to reduce the necrotic core and its associated inflammatory components). One limitation of the experimental design of our study, which sequenced aortic CD45+ cells from pooled mice, is that experimental considerations such as tissue procurement and sample preparation can introduce technical variation and thus, independent replication is important. In addition, future studies in human immune cell subsets will be needed to confirm the observed effects of miR-33 silencing on inflammation resolution. Furthermore, the incorporation of additional technologies, such as mass cytometry and spatial transcriptomics, will provide greater temporal, spatial and functional resolution in understanding immune cell dynamics in plaques during atherosclerosis regression. Such understanding has the promise to help guide new interventional strategies to block or enhance the actions of distinct immune cell subpopulations to enable the resolution of atherosclerotic inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Online Figures I - VIII

Major Resources Table

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Atherosclerosis results from chronic inflammation in the artery wall in the setting of dyslipidemia. Lipid lowering therapies alone are insufficient to significantly regress existing atherosclerotic plaques, and strategies targeting plaque inflammation are thought to hold promise for the primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression that mediate translational repression of mRNAs and/or their degradation. Notably, individual miRNAs can have multiple gene targets, often in related pathways, providing a mechanism to coordinately regulate gene expression. A prime example of this paradigm is miR-33, which provides a layer of post-transcriptional control over genes engaged in lipid homeostasis, nutrient sensing and energy regulation.

Targeted inhibition of miR-33 using anti-sense oligonucleotides has been shown to increase plasma HDL cholesterol and promote atherosclerosis regression in mice, in part, by enhancing reverse cholesterol transport and dampening plaque inflammation. However, how miR-33 reshapes the immune microenvironment of plaques remains poorly understood.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Using single cell RNA-sequencing combined with monocyte-labeling techniques, immunohistological staining and flow cytometry we show that treatment of atherosclerotic mice with a miR-33 antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) alters the dynamic balance of innate and adaptive immune cells in plaques to favor inflammation resolution and tissue repair.

miR-33 ASO treated mice show reduced frequency of the MHCIIhi “inflammatory” and Trem2hi “metabolic” macrophage subsets, CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Th1 cells in plaques, but increased numbers of immune-dampening regulatory T cells.

By single cell RNA-sequencing we identify distinct subsets of miR-33 target genes that are derepressed in the various immune cell subsets of the plaque.

We correlated changes in macrophage kinetic processes (recruitment, retention, proliferation, death) with changes in the transcriptomic profiles of resident, MHCIIhi, and Trem2hi subsets, to unveil the distinct contributions of plaque macrophage subtypes to the anti-atherosclerotic effects of miR-33 ASO.

Our findings connect the functional and transcriptional phenotypic changes of plaque macrophages and other immune cells upon miR-33 silencing to provide insight into the mechanisms underlying anti-miR-33’s atheroprotective actions in the plaque.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Current therapies targeting atherogenic lipids reduce atherosclerotic plaque progression, but are inadequate to appreciably regress existing plaques. There is thus an urgent need to identify pathways that resolve inflammation in the artery wall and to enable plaque regression. We report that inhibiting miR-33 using ASOs in atherosclerotic mice promotes the resolution of atherosclerotic inflammation and plaque contraction by altering the immune cell balance and transcriptional landscape. Our study integrates data from single cell RNA-sequencing, flow cytometry and immunohistological analyses to identify shifts in immune cell subpopulations and their gene expression patterns mediated by inhibiting miR-33 that promote inflammation resolution and tissue repair in the plaque. Together, our findings connect the functional and transcriptional phenotypic changes of plaque macrophages and other immune cells upon miR-33 silencing to provide insight into the mechanisms underlying anti-miR-33’s atheroprotective actions in the plaque.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R35HL135799 to KJM; R01HL084312 to KJM, EAF, PL; R01HL153712 to CG; P01HL131481 to KJM and EAF; P01HL131478 to KJM and EAF; T32HL098129 to CvS], German Research Foundation Schl 2172/2 to M. Schlegel, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (NFL-2020-218415 to CG); and the American Heart Association [19POST34380010 to MSh; 14POST20180018; 19CDA34630066 to CvS; 20SFRN35210252 to CG].

Nonstandard Abbreviations And Acronyms:

- apoB

apolipoprotein B

- ASO

anti-sense oligonucleotide

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- IL

interleukin

- ILC

innate lymphoid cell

- IFN

interferon

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- LDLR

low density lipoprotein receptor

- M1

classically activated

- M2

alternatively activated

- Th

T helper cell

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

- WD

western diet

Footnotes

This manuscript was sent to Karin Bornfeldt, Internal Consulting Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article is published in its accepted form. It has not been copyedited and has not appeared in an issue of the journal. Preparation for inclusion in an issue of Circulation Research involves copyediting, typesetting, proofreading, and author review, which may lead to differences between this accepted version of the manuscript and the final, published version.

DISCLOSURES

KJM and EAF have a patent on the use of miR-33 inhibitors to treat inflammation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rhoads JP and Major AS. How Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Activates Inflammatory Responses. Crit Rev Immunol. 2018;38:333–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf D and Ley K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2019;124:315–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P and Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279:1477–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivares R, Ducimetiere P and Claude JR. Monocyte count: a risk factor for coronary heart disease? Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swirski FK, Libby P, Aikawa E, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Weissleder R and Pittet MJ. Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ and Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nature reviews Immunology. 2013;13:709–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witztum JL and Lichtman AH. The influence of innate and adaptive immune responses on atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:73–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwan AC, Aronis KN, Sandfort V, Blumenthal RS and Bluemke DA. Bridging the gap for lipid lowering therapy: plaque regression, coronary computed tomographic angiography, and imaging-guided personalized medicine. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;15:547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams KJ, Feig JE and Fisher EA. Rapid regression of atherosclerosis: insights from the clinical and experimental literature. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rayner KJ, Suarez Y, Davalos A, Parathath S, Fitzgerald ML, Tamehiro N, Fisher EA, Moore KJ and Fernandez-Hernando C. MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1570–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marquart TJ, Allen RM, Ory DS and Baldan A. miR-33 links SREBP-2 induction to repression of sterol transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12228–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F, Li Y, Shioda T, Cohen DE, Gerszten RE and Naar AM. MicroRNA-33 and the SREBP host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 2010;328:1566–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen RM, Marquart TJ, Albert CJ, Suchy FJ, Wang DQ, Ananthanarayanan M, Ford DA and Baldan A. miR-33 controls the expression of biliary transporters, and mediates statin- and diet-induced hepatotoxicity. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:882–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouimet M, Hennessy EJ, van Solingen C, Koelwyn GJ, Hussein MA, Ramkhelawon B, Rayner KJ, Temel RE, Perisic L, Hedin U, Maegdefessel L, Garabedian MJ, Holdt LM, Teupser D and Moore KJ. miRNA Targeting of Oxysterol-Binding Protein-Like 6 Regulates Cholesterol Trafficking and Efflux. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:942–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouimet M, Ediriweera H, Afonso MS, Ramkhelawon B, Singaravelu R, Liao X, Bandler RC, Rahman K, Fisher EA, Rayner KJ, Pezacki JP, Tabas I and Moore KJ. microRNA-33 Regulates Macrophage Autophagy in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:1058–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karunakaran D, Thrush AB, Nguyen MA, Richards L, Geoffrion M, Singaravelu R, Ramphos E, Shangari P, Ouimet M, Pezacki JP, Moore KJ, Perisic L, Maegdefessel L, Hedin U, Harper ME and Rayner KJ. Macrophage Mitochondrial Energy Status Regulates Cholesterol Efflux and Is Enhanced by Anti-miR33 in Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117:266–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davalos A, Goedeke L, Smibert P, Ramirez CM, Warrier NP, Andreo U, Cirera-Salinas D, Rayner K, Suresh U, Pastor-Pareja JC, Esplugues E, Fisher EA, Penalva LO, Moore KJ, Suarez Y, Lai EC and Fernandez-Hernando C. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9232–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rottiers V, Najafi-Shoushtari SH, Kristo F, Gurumurthy S, Zhong L, Li Y, Cohen DE, Gerszten RE, Bardeesy N, Mostoslavsky R and Naar AM. MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic diseases. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2011;76:225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouimet M, Koster S, Sakowski E, Ramkhelawon B, van Solingen C, Oldebeken S, Karunakaran D, Portal-Celhay C, Sheedy FJ, Ray TD, Cecchini K, Zamore PD, Rayner KJ, Marcel YL, Philips JA and Moore KJ. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces the miR-33 locus to reprogram autophagy and host lipid metabolism. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:677–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramirez CM, Goedeke L, Rotllan N, Yoon JH, Cirera-Salinas D, Mattison JA, Suarez Y, de Cabo R, Gorospe M and Fernandez-Hernando C. MicroRNA 33 regulates glucose metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:2891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afonso MS, Verma N, Sharma M, van Solingen C, Perie L, Corr EM, Schlegel M, Shanley LC, Peled D, Yoo JY, Schmidt AM, Mueller E and Moore KJ. MicroRNA-33 regulates brown fat functionality and adaptive thermogenesis. Circ Res. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Rayner KJ, Esau CC, Hussain FN, McDaniel AL, Marshall SM, van Gils JM, Ray TD, Sheedy FJ, Goedeke L, Liu X, Khatsenko OG, Kaimal V, Lees CJ, Fernandez-Hernando C, Fisher EA, Temel RE and Moore KJ. Inhibition of miR-33a/b in non-human primates raises plasma HDL and lowers VLDL triglycerides. Nature. 2011;478:404–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayner KJ, Sheedy FJ, Esau CC, Hussain FN, Temel RE, Parathath S, van Gils JM, Rayner AJ, Chang AN, Suarez Y, Fernandez-Hernando C, Fisher EA and Moore KJ. Antagonism of miR-33 in mice promotes reverse cholesterol transport and regression of atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2921–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouimet M, Ediriweera HN, Gundra UM, Sheedy FJ, Ramkhelawon B, Hutchison SB, Rinehold K, van Solingen C, Fullerton MD, Cecchini K, Rayner KJ, Steinberg GR, Zamore PD, Fisher EA, Loke P and Moore KJ. MicroRNA-33-dependent regulation of macrophage metabolism directs immune cell polarization in atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4334–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotllan N, Ramirez CM, Aryal B, Esau CC and Fernandez-Hernando C. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-33 inhibits the progression of atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice--brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1973–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Arampatzi P, Pelisek J, Winkels H, Ley K, Wolf D, Saliba AE and Zernecke A. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals the Transcriptional Landscape and Heterogeneity of Aortic Macrophages in Murine Atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2018;122:1661–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, Chudnovskiy A, Amir ED, Amadori L, Khan NS, Wong CK, Shamailova R, Hill CA, Wang Z, Remark R, Li JR, Pina C, Faries C, Awad AJ, Moss N, Bjorkegren JLM, Kim-Schulze S, Gnjatic S, Ma’ayan A, Mocco J, Faries P, Merad M and Giannarelli C. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat Med. 2019;25:1576–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin JD, Nishi H, Poles J, Niu X, McCauley C, Rahman K, Brown EJ, Yeung ST, Vozhilla N, Weinstock A, Ramsey SA, Fisher EA and Loke P. Single-cell analysis of fate-mapped macrophages reveals heterogeneity, including stem-like properties, during atherosclerosis progression and regression. JCI Insight. 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winkels H, Ehinger E, Vassallo M, Buscher K, Dinh HQ, Kobiyama K, Hamers AAJ, Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Saliba AE, Zernecke A, Pramod AB, Ghosh AK, Anto Michel N, Hoppe N, Hilgendorf I, Zirlik A, Hedrick CC, Ley K and Wolf D. Atlas of the Immune Cell Repertoire in Mouse Atherosclerosis Defined by Single-Cell RNA-Sequencing and Mass Cytometry. Circ Res. 2018;122:1675–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willemsen L and de Winther MP. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis as defined by single-cell technologies. J Pathol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Distel E, Barrett TJ, Chung K, Girgis NM, Parathath S, Essau CC, Murphy AJ, Moore KJ and Fisher EA. miR33 inhibition overcomes deleterious effects of diabetes mellitus on atherosclerosis plaque regression in mice. Circ Res. 2014;115:759–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potteaux S, Gautier EL, Hutchison SB, van Rooijen N, Rader DJ, Thomas MJ, Sorci-Thomas MG and Randolph GJ. Suppressed monocyte recruitment drives macrophage removal from atherosclerotic plaques of Apoe−/− mice during disease regression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2025–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagareddy PR, Murphy AJ, Stirzaker RA, Hu Y, Yu S, Miller RG, Ramkhelawon B, Distel E, Westerterp M, Huang LS, Schmidt AM, Orchard TJ, Fisher EA, Tall AR and Goldberg IJ. Hyperglycemia promotes myelopoiesis and impairs the resolution of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2013;17:695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinstock A and Fisher EA. Methods to Study Monocyte and Macrophage Trafficking in Atherosclerosis Progression and Resolution. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1951:153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemdahl AL, Gabrielsen A, Zhu C, Eriksson P, Hedin U, Kastrup J, Thoren P and Hansson GK. Expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.te Boekhorst BC, Bovens SM, Hellings WE, van der Kraak PH, van de Kolk KW, Vink A, Moll FL, van Oosterhout MF, de Vries JP, Doevendans PA, Goumans MJ, de Kleijn DP, van Echteld CJ, Pasterkamp G and Sluijter JP. Molecular MRI of murine atherosclerotic plaque targeting NGAL: a protein associated with unstable human plaque characteristics. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:680–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lok ZSY and Lyle AN. Osteopontin in Vascular Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:613–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, Butte AJ and Bhattacharya M. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leo C and Chen JD. The SRC family of nuclear receptor coactivators. Gene. 2000;245:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dutta P, Hoyer FF, Sun Y, Iwamoto Y, Tricot B, Weissleder R, Magnani JL, Swirski FK and Nahrendorf M. E-Selectin Inhibition Mitigates Splenic HSC Activation and Myelopoiesis in Hypercholesterolemic Mice With Myocardial Infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1802–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R and Pittet MJ. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman K, Vengrenyuk Y, Ramsey SA, Vila NR, Girgis NM, Liu J, Gusarova V, Gromada J, Weinstock A, Moore KJ, Loke P and Fisher EA. Inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes and their conversion to M2 macrophages drive atherosclerosis regression. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2904–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roufaiel M, Gracey E, Siu A, Zhu SN, Lau A, Ibrahim H, Althagafi M, Tai K, Hyduk SJ, Cybulsky KO, Ensan S, Li A, Besla R, Becker HM, Xiao H, Luther SA, Inman RD, Robbins CS, Jongstra-Bilen J and Cybulsky MI. CCL19-CCR7-dependent reverse transendothelial migration of myeloid cells clears Chlamydia muridarum from the arterial intima. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trogan E, Feig JE, Dogan S, Rothblat GH, Angeli V, Tacke F, Randolph GJ and Fisher EA. Gene expression changes in foam cells and the role of chemokine receptor CCR7 during atherosclerosis regression in ApoE-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3781–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yurdagul A Jr., Doran AC, Cai B, Fredman G and Tabas IA. Mechanisms and Consequences of Defective Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ait-Oufella H, Kinugawa K, Zoll J, Simon T, Boddaert J, Heeneman S, Blanc-Brude O, Barateau V, Potteaux S, Merval R, Esposito B, Teissier E, Daemen MJ, Leseche G, Boulanger C, Tedgui A and Mallat Z. Lactadherin deficiency leads to apoptotic cell accumulation and accelerated atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2168–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma M, Schlegel MP, Afonso MS, Brown EJ, Rahman K, Weinstock A, Sansbury B, Corr EM, van Solingen C, Koelwyn G, Shanley LC, Beckett L, Peled D, Lafaille JJ, Spite M, Loke P, Fisher EA and Moore KJ. Regulatory T Cells License Macrophage Pro-Resolving Functions During Atherosclerosis Regression. Circ Res. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Feig JE, Parathath S, Rong JX, Mick SL, Vengrenyuk Y, Grauer L, Young SG and Fisher EA. Reversal of hyperlipidemia with a genetic switch favorably affects the content and inflammatory state of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2011;123:989–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]