Abstract

Background

The aim of this study is to review current indications to diagnostic and/or operative hysteroscopy in primary and secondary infertility, as well as to determine its efficacy in improving fertility.

Materials and Methods

We gathered available evidence about the role of hysteroscopy in the management of vari- ous infertility conditions. Literature from 2000 to 2020 that pertained to this topic were retrieved and appropriately selected.

Results

Hysteroscopy does not appear as a first line diagnostic procedure for every clinical scenario. However, its di- agnostic sensitivity and specificity in assessing intrauterine pathology is superior to all other non-invasive techniques, such as saline infusion/gel instillation sonography (SIS/GIS), transvaginal sonography (TVS) and hysterosalpingog- raphy (HSG). Hysteroscopy allows not only a satisfactory evaluation of the uterine cavity but also, the eventual treat- ment of endocavitary pathologies that may affect fertility both in spontaneous and assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles.

Conclusion

Hysteroscopy, due to its diagnostic and therapeutic potential, should be regarded as a necessary step in infertility management. However, in case of suspected uterine malformation, hysteroscopy should be integrated with other tests [three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)] for diagnostic confirmation.

Keywords: Hysteroscopy, Infertility, Pregnancy Rate, Primary Infertility

Introduction

During the last decade, infertility has had an increasing impact onthe health of Western countries’ populations. The most accepted definition of infertility is failure to conceive after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourses (1).

During the last 20 years, multiple factors have been addressed as causes of reduced spontaneous conception, among which intrauterine pathologies might play a crucial role. According to this, several treatments have been proposed to overcome infertility due to the presence of intrauterine affections. In this context, hysteroscopy is currently considered the gold standard for both assessment and management of intrauterine factors. Indeed, it allows a more precise diagnosis of endometrial abnormalities compared to non-invasive techniques such as transvaginal sonography (TVS), hysterosalpingography (HSG) and sonohysterography; above all, it allows for simultaneous treatment of an intrauterine pathology (2).

The present study is a systematic review on the efficacy of diagnostic and/or operative hysteroscopy in improving reproductive outcomes for specific conditions in infertile women.

Materials and Methods

We systematically reviewed the literature from 2000 to 2020 by searching in PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Libraryby using the following keywords: infertility, hysteroscopy, pregnancy rate (PR), miscarriages, live birth rates (LBR), uterine malformations and metroplasty. In general, randomised controlled trials (RCT) were selected; if they were not available on a specific subject, less relevant studies were chosen. The patients included in this review were infertile women with or without endometrial abnormalities who sought spontaneous conception or required in vitro fertilization/ intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI). The type of intervention analysed is diagnostic and/or operative hysteroscopy performed during the infertility evaluation and/or prior IVF/ICSI compared to no hysteroscopy in similar groups of patients.

Study population

We divided the studied population according to indication and efficacy of hysteroscopy in improving reproductive outcomes. As result, we obtained the following four groups: group A: initial work-up of asymptomatic patients with negative ultrasound findings; group B: women with endometrial abnormalities at the TVS with or without abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB); group C: patients with genital tract malformations and/or recurrent abortions; and group D: women with negative ultrasound findings who required assisted reproductive technology (ART), IVF or ICSI.

Main outcomes

The primary outcome was clinical PR (CPR), which was defined by at least TVS visualization of the gestational sac. The secondary outcome was miscarriage rate (MR), which was defined as pregnancy loss before 20 weeks of gestation.

Results

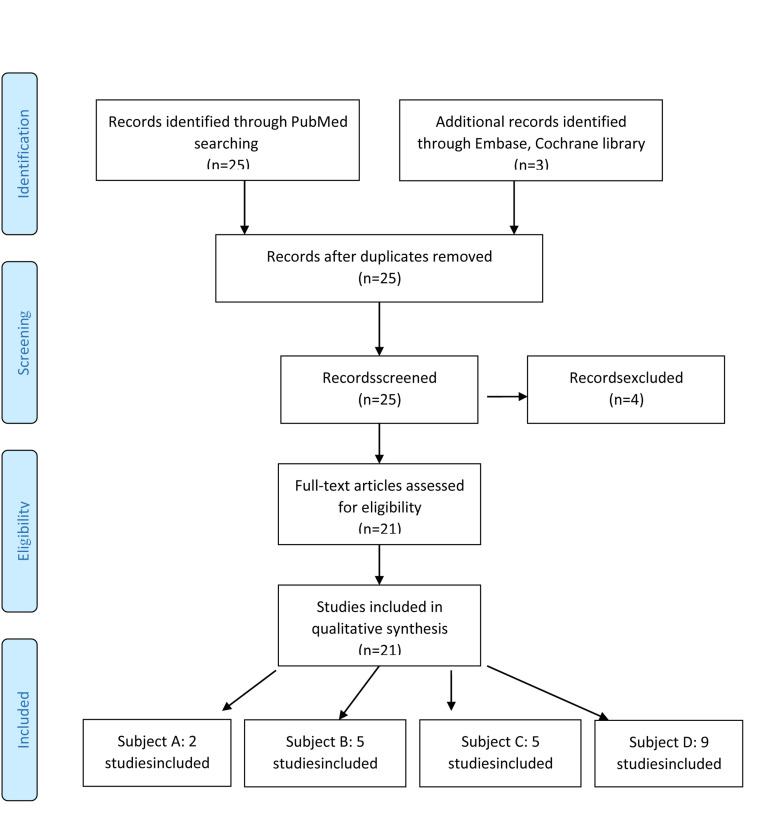

Atotal of 28 records were considered in the study selection process. After removing three duplicates and excluding four studies due to incomplete outcomes, 21 full-text articles wereconsidered suitable for the systematic review (Fig.1).

Fig.1.

Prisma flow chart (3).

Subdivisions of the selected articles according to groups A, B, C or D, and their results, are described as follows. Only two studies, one retrospective and one prospective, were included in group A, which showed that a consistent percentage of women (79 and 33%, respectively) had hysteroscopic abnormalities (Table 1). Group B comprised four studies- two prospective, one RCT, and one retrospective cross-sectional. The outcomes reported that 65% of patients achieved pregnancy after hysteroscopy with only one intrauterine insemination (IUI), and the PR was significantly higher after hysteroscopic removal of submucous myomas. Malignancy or atypia did not occur in the subsequent 12 months of followup after the hysteroscopy, and the uterine cavity was restored in 93.6% of women, respectively (Table 2). Group C had five studies, three prospective and two retrospectives. The results revealed significantly higher PR and LBR in patients who underwent hysteroscopic treatment of uterine septum (Table 3). A total of nine RCT studies were assigned to group D. This group had significantly higher PR, CPR, LBR and implantation rate (IR) in the selected categories of patients who underwent hysteroscopy before ICSI (Table 4). Tables 1-4 display the aforementioned groups in extensive details.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two studies included in group A

| Author | Country, year | Study design | Main inclusion criteria | Intervention | Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di Muzio et al. (4) | Italy, 2016 | Retrospective | 92 nulliparous patients with unexplained infertility (absence of uterine lesions at TVS and HSG) | All patients underwent diagnostic and operative hysteroscopies | No | PR: 85% (79% of patients had endometrial lesions) |

| Elbareg et al. (5) | Libya, 2014 | Prospective | 200 infertile women in whom standard infertility investigations revealed no abnormalities | All women underwent diagnostic and operative hysteroscopies | No | PR: 46%(33% of women had hysteroscopic abnormalities) |

TVS; Transvaginal sonography, HSG; Hysterosalpingography, and PR; Pregnancy rate.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the five studies included in group B

| Author | Country, year | Study design | Main inclusion criteria | Intervention | Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perez-Medina et al. (6) | Spain, 2005 | RCT | 204 infertile women with sonographic diagnosis of EP and candidates for IUI | n=101Patients underwent hysteroscopic polypectomy | n=103Patients underwent diagnostic hysteroscopy and polyp biopsy | PR: 63.4% vs. 28.2% (P<0.001)PR (after four IUI cycles) 51.4% vs. 25.4% (P<0.001) (Pregnancies in the study group were obtained before the first IUI in 65% of cases) |

| Casini et al. (7) | Italy, 2006 | RCT | 181 infertile women with uterine fibroids | n=92Patients underwent laparotomy or hysteroscopic myomectomy(30 SM; 23 IM; 17 IM-SS and 22 SM-IM) | n=89Patients did not undergo surgical treatment:(22 SM; 22 IM; 11 SS; 14 IM-SS and 20 with IM-SM) | PR (SM): 43.3% vs. 27.2%(P<0.05)PR (IM): 56.5% vs. 41%(P: NS)PR (SM-IM): 36.4% vs. 15%(P<0.05)PR (IM-SS): 35.5% vs. 21.4%(P: NS) |

| Mazzon et al. (8) | Italy, 2010 | Prospective study | 6 young nulliparous patients with stage IA endometrial cancer | All patients underwent hysteroscopic resection of the tumour followed by hormone therapy (megestrol acetate,160 mg/day, for 6 months) | No | PR: 66%(no atypia or malignancy after 12 months follow-up) |

| Chen et al. (9) | China, 2017 | Retrospective cross-sectional study | 350 infertile women with mild, moderate, and severe IUAs | All patients underwent hysteroscopic adhesiolysis(The reproductive outcomes of 332 cases, 93%, were followed for 27 ± 9 months) | No | PR: 48.2%(60.7% in mild IUAs, 53.4% in moderate, 25% in severe cases)MR: 9.4% LBR: 85.6% Uterine cavity was restored in 93.6% of patients) |

EP; Endometrial polyp, SM; Submucosal fibroid, IM; Intramural fibroid, SS; Subserosal fibroid, SM-IM; Submucosal-intramural fibroid, IM-SS; Intramural-subserosal fibroid, IUA; Intrauterine adhesion, IUI; Intrauterine insemination, MR; Miscarriage rate, LBR; Live birth rate, CR; Conception rate, CS; Caesarean section, PAUB; Postmenstrual uterine bleeding, PR; Pregnancy rate, and RCT; Randomised controlled trial.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the five studiesincluded in group C

| Author | Country, year | Study design | Main inclusion criteria | Intervention | Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mollo et al. (10) | Italy, 2008 | Prospective controlled trial | 176 infertile women | n=44Patients withseptate uterus and underwent hysteroscopic metroplasty | n=132Patients with unexplained infertility, managed expectantly | PR: 38.6% vs. 20.4% LBR: 34.1% vs. 18.9% |

| Tonguc et al. (11) | Turkey, 2010 | Retrospective study | 127 infertile women with uterine septum | n=102Patients underwent hysteroscopic metroplasty | n=25Patients did not undergo metroplasty | PR: 43.1% vs. 20% (P=0.03)MR: 11.4% vs. 60% (P=0.02)LBR: 35.3% vs. 8% (P=0.008) |

| Pacheco et al. (12) | Spain, 2019 | Prospective cohort study | 63 nulliparous infertile womenwith primary T-shaped uterus | All women underwent hysteroscopic metroplasty (Only 60 patients tried to conceive after metroplasty) | No | PR:83.3% LBR:63.3% |

| Ban-Frangež et al. (13) | Slovenia, 2008 | Retrospective matched control study | 380 women conceived following IVF/ICSI | n=106Patients underwent hysteroscopic resection ofa small or large septum | n=274 Patients did not undergo surgery because they did not have any uterine malformation | MR (small septum): 30.6% vs. 20.4%(P: NS)MR (large septum): 28.1% vs. 19.3%(P: NS) |

| Bakas et al. (14) | Greece, 2012 | Prospective observational | 68 infertile women with septate uterus (12 months follow-up) | All patients underwent hysteroscopic metroplasty | No | CPR: 44%LBR: 36.8%MR: 16.6% |

CPR; Clinical pregnancy rate, MR; Miscarriage rate, AR; Abortion rate, LBR; Live birth rate, PR; Pregnancy rate, IVF; In vitro fertilization, ICSI; Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and NS; Not significant.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the nine studies included in group D

| Author | Country, year | Study design | Main inclusion criteria | Intervention | Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raju et al. (15) | India, 2006 | Prospective RCT | 520 women undergoing IVF programme | n=255Had office hysteroscopy-Group A (n=160) hadnormalhysteroscopic findings-Group B(n=95) had abnormal office hysteroscopyfindings that were corrected | n=265Without office hysteroscopy | CPR 44.4% (A) 39.5% (B) vs. 26.2% (P<0.05) |

| Elsetohy et al. (16) | Egypt, 2014 | RCT | 193 infertile women with no abnormality detected in TVS undergoing ICSI | n= 97 Hysteroscopic examination before ICSI | n=96ICSI without hysteroscopy | PR: 70.1% vs. 45.8% (P=0.001) |

| Smit et al. (17) | Netherlands, 2016 | Multicentre RCT | 742 infertile women scheduled to start IVF or ICSI treatment, with normal TVS | n=369 Hysteroscopy prior to IVF(355 completed 18 months of follow-up) | n=373IVF without hysteroscopic examination(353 completed 18 months of follow-up) | OP: 57%vs. 54% (P=0.41) |

| Aghahosseini et al. (18) | Iran,2012 | RCT | 353 women undergoing ICSI withtwo or more implantation failuresand:- no uterine cavity abnormalities- normal HSG - age <38 years. | n=142 Hysteroscopy prior to ART | n=211 Immediate ICSI without prior hysteroscopy | CPR: 50.7% vs. 30.3% Delivery rates was 35.5% in the hysteroscopy group and 21.1% in the control group, respectively |

| El-Toukhy et al. (19) | UK, Italy, Belgium, Czech Republic, 2016 | Multicentre RCT | n=367 IVF cycle with prior hysteroscopy | n=352 IVF cycle without prior hysteroscopy | 102 (29%) of women in the hysteroscopy group had a livebirth after IVF compared with 102 (29%) women in the control group (risk ratio 1-0.95% CI 0.79–1.25; P=0.96) | |

| Shawki et al. (20) | Egypt, 2012 | RCT | 719 infertile women younger than 38 years, with two to four failed IVF cycles and planned a further IVF/ICSI cycle | n=105ICSI after office hysteroscopy | n=110ICSI without office hysteroscopy | IR and CPR were statistically significant between the intervention group and control group |

| Demirol and Gurgan (21) | Turkey, 2004 | RCT | 225 infertile women with no uterine factor of infertility,abnormal HSG or TVS, previousintrauterine surgery or contraindication for hysteroscopy | n=210Office hysteroscopic before IVF cycles.Group IIa (n = 154) had normalhysteroscopic findings, and group IIb (n = 56) had abnormal hysteroscopic findings | n=211No office hysteroscopic evaluation before IVF cycles | There was a significant difference in the CPR between patients in the control group and group II a (21.6% and 32.5%, P=0.044, respectively) and control group and group IIb (21.6% and 30.4%, P=0.044, respectively) |

| El-Nashar and Nasr (22) | Egypt, 2011 | RCT | 421 patients with primary infertility and two or more failed IVF cycles with no uterine cavity abnormalities and normal HSG | n=62 Hysteroscopy with directed biopsy and correction of any intrauterine abnormalities before ICSI | n = 62ICSI cycle without undergoing a hysteroscopy | CPR: 40.3% vs. 24.2% (P<0.05) |

| Shohayeb and El-Khayat (23) | Egypt, 2012 | Prospective RCT | 124 infertile women starting their first ICSI cycle 210 infertile womenwith a history of two or more failed ICSI cycles and withnormal thin endometrium | n=105 Hysteroscopy and endometrial scraping in the cycle preceding the ICSI cycle | n=105 Hysteroscopy without endometrial scraping | IR: 12% vs. 7% (P=0.015). CPR: 32% vs. 18 %(P=0.034) BR 28% vs. 14% (P=0.024) |

RCT; Randomized controlled trial, PR; Pregnancy rate, TVS; Transvaginal sonography, HSG; Hysterosalpingography, IR; Implantation rate, MR; Miscarriage rate, LBR; Live birth rate, OP; Ongoing pregnancy rate, ICSI; Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, IVF; In vitro fertilization, ART; Assisted reproductive technology, and CPR; Clinical pregnancy rate.

Discussion

The exploration of the uterine cavity as a routine procedureduring the initial infertility work-up is still under debate. With regards to our study results, only two studies were included in the systematic review, which analysed the role of hysteroscopy in asymptomatic infertile women. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE guidelines, 2014) stated that hysteroscopy should not be offered during the initial infertility evaluation; on the other hand, according to the Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), hysteroscopy is a relatively expensive and invasive procedure (2). In contrast, the guidelines of the Italian Society of Gynaecological Endoscopy (SEGI), strictly recommend hysteroscopy as a screening procedure for the infertile couple as part of the primary work-up (24), even if a specific evidence of its usefulness in these cases is lacking. Similarly, the literature currently shows an increasing trend towards hysteroscopic evaluation for women who struggle with unexplained infertility. Moreover, this kind of management could help todetect lesions that were not diagnosed by other tools. Indeed, it mayprovide definitive treatment of endocavitary lesions that could impact women fertility (4).

Conversely, hysteroscopic exam of the uterine cavity is considered mandatory during the primary work-up of infertile couples in presence endometrial abnormalities detected at TVS, accompanied or notby bleeding. In this context, the most common endometrial pathologies observed by hysteroscopyare endometrial polyps and submucous fibroids. In general, their treatment by operative hysteroscopy improves PR and reproductive outcomes. Endometrial polyps are thought to interfere with uterine receptivity and embryo implantation, and adversely impact fertility (25). Current evidence supports hysteroscopic resection of endometrial polyps prior to ART in order to improve fertility (6, 25-27). There is a 50% viable PR obtained after polypectomy among subfertile patients (26). In cases with hysteroscopic polypectomy prior to IUI, hysteroscopic removal of polyps showed a significant improvement in clinical PR (27). Submucous fibroids should be also removed in infertile patients, especially if they significantly impact the endometrial line, regardless of the size or the presence of symptoms (27, 28).

Infertility may be associated with AUB, not only in cases of endometrial polyps and submucous myoma, but also in cases of other endometrial pathologies such as adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial malignancy. In the latter cases, it is interesting to report that small (<2 cm) intramucous endometrial cancer, well-differentiated, may be removed by hysteroscopy, preserving fertility (29).

Another emerging cause of infertility associated with AUB is isthmocele or uterine scar defects following caesarean section (CS). These may be defined as first, second, or third degree according tothe dimensions. Hysteroscopic treatment of isthmocele is reported to be associated with an increased PR (30).

Intrauterine adhesions (IUA), occasionally associated with Asherman syndrome, are caused by postsurgical or infectious damage to the basalis layer of the endometrium. IUA, sometimes detected on ultrasound as endometrial thickening, may be responsible for infertility and recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) (31). In this context, hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard for both diagnosis and treatment (32).

Hysteroscopic adhesiolysisis associated with improved fertility as well as reproductive outcomes as reported by Goldenberg et al. (33). Moreover, hysteroscopic evaluation of the uterine cavity is recommended in order to identify eventual congenital uterine abnormalities in patients with RPL (34-36). Indeed, women with a history of recurrent miscarriage or infertility have higher prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies compared with those not having a history of recurrent miscarriage or infertility (37). However, it is important to highlight that, among congenital uterine malformations, septate uterus is the most common structural uterine anomaly associated with the highest incidence of reproductive failure (28). In this context, the Thessaloniki ESHRE/ ESGE consensus on diagnosis of the female genital anomalies has recently established that the combination of gynaecologic examination and two-dimensional (2D)-TVS is recommended as the current standard for the evaluation of asymptomatic women, while threedimensional (3D)-TV is recommended when genital tract anomalies are suspected. Thus, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoscopic evaluation are also indicated, but only in complex cases or in diagnostic dilemmas (38).

Hysteroscopy, as well as HSG, cannot differentiate septate from bicorporal uterus, due to their inability to assess the contour of the uterus; therefore, both procedures have a limited diagnostic value in the evaluation of genital tract malformations. Conversely, hysteroscopy compared to HSG, may be more useful to investigate the relationship between the cervix (single or double) and the vaginal canal, and analyse the vaginal, the cervical and the uterine intracavitary morphology (39).

When infertility is associated with the presence of a uterine septum, operative hysteroscopy is a valuable tool that offers resolutive management. Bakas et al. (14) have proposed that hysteroscopic metroplasty in patients with septate uterus and unexplained infertility is a method to improve CPR and LBR. Grimbizis et al. (40) reported 6.1% of LBR in untreated women with uterine septum compared with 82% in those who underwent hysteroscopic metroplasty. To date, RCTs with the aim to evaluate the effectiveness and possible complications of hysteroscopic metroplasty have not been published (41). Furthermore, it seems that hysteroscopy with biopsy may be a valid tool in patients with RPL and recurrent implantation failure (RIF) in order to detect chronic endometritis, as reported by Zargar et al. (42).

In ART, the role of hysteroscopy is even more important. In the clinical practice, hysteroscopy is commonly performed before IVF in all patients, including women with normal TVS and/or HSG findings, because a significant percentage may have a misdiagnosed uterine disease that might negatively affect the success of the fertility treatment (43). Hysteroscopy reveals the presence of intrauterine lesions in almost 28% of infertile patients with negative TVS results undergoing ART. This demonstrates that TVS hasa low sensitivity in diagnosis of several intrauterine alterations (44).

Moreover, the RCT by Elsetohy et al. (16), reported that 43.3% of women with negative ultrasounds showed abnormal hysteroscopic findings prior to ICSI. Similarly, an improved IR and CPR, after office hysteroscopy and before undergoing ICSI, was observed, especially in patients whose uterine abnormalities were corrected (20, 45).

El-Toukhy et al. (19) reported significant improvement in PR when hysteroscopy was performed in the cycle before IVF, regardless of intrauterine abnormalities. Possible explanations include possible reliance on irrigation of the cavity with saline, which mechanically removes harmful antiadhesive glycoprotein molecules (46); probing of the cervical canal, which makes the embryotransfer procedure easier (23); and mechanical endometrial injury, which may enhance receptivity by modulating the expressions of gene encoding factors required for implantation (47- 52). Finally, a screening hysteroscopy is recommended prior to ART and highly recommended after two or more failed IVF cycles.

The strength of our study relies on its design. This systematic review included a large sample size of infertile women with or without endometrial abnormalities who sought spontaneous conception or required IVF/ICSI. Despite our robust methodological approach, risk of bias inherent to the nature of the study itself should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Larger, prospective randomised studies are warranted to draw firm conclusions.

Conclusion

Hysteroscopy represents the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of abnormal uterine findings that are present in approximately 25% of infertile women. These lesions can interfere with spontaneous and assisted reproduction, and may remain undiagnosed with the use of TVS, SIS/GIS or HSG. Although spontaneous or assisted reproductive conception is possible, even in the presence of the small intrauterine abnormalities that represent only 2-3% of infertility causes, their treatment by operative hysteroscopy may help improving the IR and CPR. However, it has to be considered that treatment of intrauterine lesions may not always be synonymous with restoration of fertility. Diagnostic and, if required, operative hysteroscopy prior to ART in infertile women with or without intrauterine abnormalities, may contribute to increase reproductive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This research received no financial support and conflicts of interest in this study.

Authors’ Contributions

F.G.; Was responsible for the manuscript draft. M.M.M.; Designed the tables. F.D.G.; Contributed to the manuscript and English review. V.D., V.L.; Contributed to the research of studies suitable for the review. F.M.C., M.P.; Substantially revised the last draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript version.

References

- 1.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009*. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Spiezio Sardo A, Di Carlo C, Minozzi S, Spinelli M, Pistotti V, Alviggi C, et al. Efficacy of hysteroscopy in improving reproductive outcomes of infertile couples: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(4):479–496. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097–e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Muzio M, Gambaro AML, Colagiovanni V, Valentini L, Di Simone E, Monti M. The role of hysteroscopy in unexplained infertility. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2016;43(6):862–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elbareg AM, Essadi FM, Anwar KI, Elmehashi MO. Value of hysteroscopy in management of unexplained infertility. Asian Pac J Reprod. 2014;3(4):295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-Medina T, Bajo-Arenas J, Salazar F, Redondo T, Sanfrutos L, Alvarez P, et al. Endometrial polyps and their implication in the pregnancy rates of patients undergoing intrauterine insemination: a prospective, randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(6):1632–1635. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casini ML, Rossi F, Agostini R, Unfer V. Effects of the position of fibroids on fertility. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22(2):106–109. doi: 10.1080/09513590600604673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzon I, Corrado G, Masciullo V, Morricone D, Ferrandina G, Scambia G. Conservative surgical management of stage IA endometrial carcinoma for fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1286–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Zhang H, Wang Q, Xie F, Gao S, Song Y, et al. Reproductive outcomes in patients with intrauterine adhesions following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis: experience from the largest women's hospital in China. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(2):299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollo A, De Franciscis P, Colacurci N, Cobellis L, Perino A, Venezia R, et al. Hysteroscopic resection of the septum improves the pregnancy rate of women with unexplained infertility: a prospective controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2628–2631. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonguc EA, Var T, Yilmaz N, Batioglu S. Intrauterine device or estrogen treatment after hysteroscopic uterine septum resection. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2010;109(3):226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pacheco LA, Laganà AS, Garzon S, Garrido AP, Gornés AF, Ghezzi F. Hysteroscopic outpatient metroplasty for T-shaped uterus in women with reproductive failure: results from a large prospective cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;243:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ban-Frangež H, Tomaževič T, Virant-Klun I, Verdenik I, Ribič-Pucelj M, Bokal EV. The outcome of singleton pregnancies after IVF/ICSI in women before and after hysteroscopic resection of a uterine septum compared to normal controls. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakas P, Gregoriou O, Hassiakos D, Liapis A, Creatsas M, Konidaris S. Hysteroscopic resection of uterine septum and reproductive outcome in women with unexplained infertility. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;73(4):321–325. doi: 10.1159/000335924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raju GR, Kumari GS, Krishna KM, Prakash GJ, Madan K. Assessment of uterine cavity by hysteroscopy in assisted reproduction programme and its influence on pregnancy outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2006;274(3):160–164. doi: 10.1007/s00404-006-0174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsetohy KA, Askalany AH, Hassan M, Dawood Z. Routine office hysteroscopy prior to ICSI vs.ICSI alone in patients with normal transvaginal ultrasound: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(1):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3397-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smit JG, Kasius JC, Eijkemans MJ, Koks CA, Van Golde R, Nap AW, et al. Hysteroscopy before in-vitro fertilisation (inSIGHT): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10038):2622–2629. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghahosseini M, Ebrahimi N, Mahdavi A, Aleyasin A, Safdarian L, Sina S. Hysteroscopy prior to assisted reproductive technique in women with recurrent implantation failure improves pregnancy likelihood. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):S4–S4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Toukhy T, Campo R, Khalaf Y, Tabanelli C, Gianaroli L, Gordts SS, et al. Hysteroscopy in recurrent in-vitro fertilisation failure (TROPHY): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10038):2614–2621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shawki HE, Elmorsy M, Eissa MK. Routine office hysteroscopy prior to ICSI and its impact on assisted reproduction program outcome: a randomized controlled trial. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2012;17(1):14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demirol A, Gurgan T. Effect of treatment of intrauterine pathologies with office hysteroscopy in patients with recurrent IVF failure. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;8(5):590–594. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Nashar IH, Nasr A. The role of hysteroscopy before intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI): a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(3):S266–S266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shohayeb A, El-Khayat W. Does a single endometrial biopsy regimen (S-EBR) improve ICSI outcome in patients with repeated implantation failure?. A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164(2):176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campo R, Santangelo F, Gordts S, Di Cesare C, Van Kerrebroeck H, De Angelis MC, et al. Outpatient hysteroscopy. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2018;10(3):115–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donaghay M, Lessey BA. Uterine receptivity: alterations associated with benign gynecological disease. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(6):461–475. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shokeir TA, Shalan HM, El-Shafei MM. Significance of endometrial polyps detected hysteroscopically in eumenorrheic infertile women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(2):84–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2003.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bosteels J, Wessel Sv, Weyers S, Broekmans FJ, D'Hooghe TM, Bongers MY, et al. Hysteroscopy for treating subfertility associated with suspected major uterine cavity abnormalities. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12(12):CD009461–CD009461. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009461.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor E, Gomel V. The uterus and fertility. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazzon I, Corrado G, Masciullo V, Morricone D, Ferrandina G, Scambia G. Conservative surgical management of stage IA endometrial carcinoma for fertility preservation. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(4):1286–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gubbini G, Casadio P, Marra E. Resectoscopic correction of the “Isthmocele” in women with postmenstrual abnormal uterine bleeding and secondary infertility. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(2):172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Spiezio Sardo A, Di Guardo F, Santangelo F, Cianci S, Giampaolino P. Commentary on “Assessment of risk factors of intrauterine adhesions in patients with induced abortion and the curative effect of hysteroscopic surgery”. J Invest Surg. 2019;32(1):90–92. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2017.1400133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanstede MMF, van der Meij E, Goedemans L, Emanuel MH. Results of centralized Asherman surgery, 2003-2013. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(6):1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.039. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldenberg M, Sivan E, Sharabi Z, Mashiach S, Lipitz S, Seidman DS. Reproductive outcome following hysteroscopic management of intrauterine septum and adhesions. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(10):2663–2665. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Di Venere R, Pansini MV, Pellegrino A, Marello F, et al. Advanced operative office hysteroscopy without anaesthesia: analysis of 501 cases treated with a 5 Fr.bipolar electrode. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(9):2435–2438. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.9.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakour SH, Jones SE, O’Donovan P. Ambulatory hysteroscopy: evidence-based guide to diagnosis and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(6):953–975. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning N, Coomarasamy A. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(6):761–771. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimbizis GF, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Saravelos SH, Gordts S, Exacoustos C, Van Schoubroeck D, et al. The Thessaloniki ESHRE/ ESGE consensus on diagnosis of female genital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(1):2–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Laganà AS, Vitale SG, Catena U, Scutiero G, et al. Is hysteroscopy better than ultrasonography for uterine cavity evaluation?. An evidence-based and patient-oriented approach. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2016;8(3):87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grimbizis GF, Camus M, Tarlatzis BC, Bontis JN, Devroey P. Clinical implications of uterine malformations and hysteroscopic treatment results. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7(2):161–174. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kowalik CR, Goddijn M, Emanuel MH, Bongers MY, Spinder T, de Kruif JH, et al. Metroplasty versus expectant management for women with recurrent miscarriage and a septate uterus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008576–CD008576. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008576.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zargar M, Ghafourian M, Nikbakht R, Mir Hosseini V, Moradi Choghakabodi P. Evaluating chronic endometritis in women with recurrent implantation failure and recurrent pregnancy loss by hysteroscopy and immunohistochemistry. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(1):116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakas P, Hassiakos D, Grigoriadis C, Vlahos N, Liapis A, Gregoriou O. Role of hysteroscopy prior to assisted reproduction techniques. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monteiro CS, Cavallo IK, Dias JA, Pereira FAN, Reis FM. Uterine alterations in women undergoing routine hysteroscopy before in vitro fertilization: high prevalence of unsuspected lesions. J Bras Reprod Assist. 2019;23(4):396–401. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20190046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fatemi HM, Kasius JC, Timmermans A, van Disseldorp J, Fauser BC, Devroey P, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected uterine cavity abnormalities diagnosed by office hysteroscopy prior to in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(8):1959–1965. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi K, Mukaida T, Tomiyama T, Oka C. High Pregnancy rate after hysteroscopy with irrigation in uterine cavity prior to blastocyst transfer in patients who have failed to conceive after blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(3 suppl 1):S206–S206. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almog B, Shalom-Paz E, Dufort D, Tulandi T. Promoting implantation by local injury to the endometrium. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2026–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen HF, Chen SU, Ma GC, Hsieh ST, Tsai H Der, Yang YS, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening: current status and future challenges. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117(2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nastri CO, Lensen SF, Gibreel A, Raine-Fenning N, Ferriani RA, Bhattacharya S, et al. Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD009517–CD009517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Di Guardo F, Corte L Della, Vilos GA, Carugno J, Török P, Giampaolino P, et al. Evaluation and treatment of infertile women with Asherman syndrome: an updated review focusing on the role of hysteroscopy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Genovese F, D’Urso G, Di Guardo F, Insalaco G, Tuscano A, Ciotta L, et al. Failed diagnostic hysteroscopy: analysis of 62 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;245:193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Di Guardo F, Palumbo M. Asherman syndrome and insufficient endometrial thickness: a hypothesis of integrated approach to restore the endometrium. Med Hypotheses. 2019;134:109521–109521. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]