Abstract

There has been an increase in school mental health research aimed at producing generalizable knowledge to address longstanding science-to-practice gaps to increase children's access to evidence-based mental health services. Successful dissemination and implementation are both important pieces to address science-to-practice gaps, but there is conceptual and semantic imprecision that creates confusion regarding where dissemination ends and implementation begins, as well as an imbalanced focus in research on implementation relative to dissemination. In this paper, we provide an enhanced operational definition of dissemination; offer a conceptual model that outlines elements of effective dissemination that can produce changes in awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation across different stakeholder groups; and delineate guiding principles that can inform dissemination science and practice. The overarching goal of this paper is to stimulate future research that aims to advance dissemination science and practice in school mental health.

Keywords: Dissemination, Dissemination science, Science-to-practice gaps, Implementation, School mental health

Introduction

There is a large gap between the number of evidence-based programs, practices, procedures, and policies (EBPs) available for addressing social, emotional, and behavioral issues among children (Cox & Southam-Gerow, 2020; Southam-Gerow & Prinstein, 2014) and their limited use in schools (Evans et al., 2013). Although there are many reasons for this gap (e.g., lack of EBP tailoring to the school setting; Owens et al., 2014), failure to effectively disseminate EBPs is likely a key contributor. Dissemination is commonly defined as “the targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience” (NIH, 2012). With its focus on information distribution, dissemination is distinct from implementation, or “active and planned efforts to mainstream an innovation within an organization” (Greenhalgh et al., 2004). The intent of dissemination is to strategically communicate information to target stakeholders (e.g., policymakers) with the goal of changing awareness, knowledge, perceptions, or motivation. Although dissemination alone cannot close the persistent gap between research and practice, skillfully constructed and deployed dissemination strategies are a necessary component of efforts that aim to advance the quality of mental health services accessed by children (Purtle et al., 2020). Lackluster dissemination likely results in critical stakeholders being unaware of EBPs and their positive outcomes, or being unmotivated to enact specific behaviors to support the implementation of EBPs. High-quality dissemination is particularly crucial within school mental health, given that schools have become the most common point of entry into a fragmented mental health system for children and adolescents (Duong et al., 2020), and therefore, efforts to improve school-based services carry profound implications for overall public health (Sanchez et al., 2018).

To advance the science of dissemination in school mental health, it is important to understand the current status of this field. First, although the broader field has been inclusively referred to as “dissemination and implementation science,” dissemination is often deemphasized (i.e., the field has been referred to simply as “implementation science”) and is an understudied aspect of how science–practice gaps are addressed. For example, a scan of some of the top journals that published dissemination and implementation research from 2000 to 2020 (i.e., Implementation Science, Frontiers in Public Health, Administration and Policy in Mental Health in Mental Health Services Research) indicates there are 25 articles on implementation science for every one study that focuses on dissemination. However, more recently there has been renewed interest in dissemination as a key step in effecting change (e.g., Ashcraft et al., 2020; Brownson et al., 2013, 2018). This paper serves as an overview of dissemination science within school mental health, with a goal of stimulating research that informs practice in this area.

Second, there is conceptual and semantic imprecision that creates confusion regarding where dissemination ends and implementation begins. Broadly speaking, dissemination is an active approach that distributes evidence-based information to “intervention targets” using predetermined channels and strategies of communicating compelling and persuasive information (Brownson et al., 2013; Wilcox et al., 2018). Indeed, there is increasing evidence that the passive spread of information (e.g., including evidence-based information on a website) is an ineffective approach; thus, effective dissemination requires active, purposeful strategies for spreading information to specific target audiences (Lehoux et al., 2005; Rabin et al., 2010). In contrast, implementation is the use of active methods to “promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice, and, hence, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health services and care” (Eccles & Mittman, 2006, p. 1). Thus, dissemination ideally temporally precedes implementation and aims to increase the likelihood that a given stakeholder will act upon the information gained by engaging in role-specific implementation behaviors (e.g., school leadership protecting time for staff to plan delivery of an EBP).

The distinction between dissemination and implementation is consistent with established theories that highlight the differences between motivational and behavioral enactment phases of behavior change [e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991); The Health Action Process Approach (Schwarzer, 2008); Capability Opportunity Motivation Behavior System (Michie et al., 2011); Transtheoretical Model of Change (DiClemente, 1999)]. Motivational antecedents to behavior change reflect preconditions, such as knowledge of an EBP or outcome expectancies related to benefits of an EBP, that increase the likelihood that a person from a key stakeholder group will enact role-specific implementation behaviors. By targeting these antecedents of behavior change, dissemination efforts have the potential to transform specific target stakeholders into change agents who ultimately are motivated to enact implementation behaviors that have the potential of leading to higher quality mental health services delivered as part of routine practice in schools. Thus, dissemination aims to increase awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation (antecedents of behavior change), whereas implementation aims to promote the enactment of specific behaviors. For example, dissemination efforts that aim to improve school administrator knowledge and attitudes about an EBP are designed to increase administrators’ motivation to engage in implementation-specific leadership behaviors (e.g., proactively supporting implementation, recognizing, and rewarding implementation) that support EBP use in the school (Aarons et al., 2014). Implementation, on the other hand, puts systems of support in place to facilitate administrators’ follow through with implementation-specific leadership behaviors, such as prompts/reminders, performance feedback, and action planning.

Although successful dissemination has the potential to promote action, established theories of behavior change consistently indicate that motivation alone is insufficient (e.g., the intention–behavior gap; Sheeran & Webb, 2016). For example, one-time training, which we view as a dissemination strategy, often improves knowledge and attitudes of providers but is unlikely to promote actual behavior change among those who are expected to implement EBPs (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). Even when motivation is high, there is often a need for strategies and supports that enable and reinforce individuals enacting new behaviors (Wandersman et al., 2012). This is where implementation picks up and implementation strategies become essential to support enactment of role-specific implementation behaviors. Clarifying the distinction between dissemination and implementation can help the field develop and test more precise and effective strategies for use in practice. Further, conceptual clarity allows us to measure precise outcomes of deliberate behavior change efforts. In addition, this distinction helps researchers understand why certain efforts to support behavior change are unsuccessful (e.g., the stakeholder is not properly motivated to enact role-specific implementation behavior or the stakeholder is motivated but not properly supported to enact the behavior), as well as recognize how dissemination and implementation strategies work in tandem to achieve the ultimate goal of improving the quality and reach of school mental health services.

The goal of this paper is to improve dissemination science, both in general and specifically within school mental health. Thus, the advice provided is primarily geared toward researchers rather than other stakeholders who are involved in the practice of dissemination. However, we hope that as generalizable knowledge is produced through dissemination science, this knowledge will inform real-world dissemination practice by researchers and other stakeholders invested in translating EBPs into routine practice. We acknowledge that it is unrealistic to expect researchers to be the main players in dissemination efforts at a large scale; nonetheless, they can play a critical role, along with other stakeholders in creating a robust dissemination infrastructure to facilitate the process of moving EBPs from research to practice (Kreuter & Bernhardt, 2009). Creating new infrastructure to readily disseminate EBPs to key stakeholder groups is needed in the long run. For example, some organizations exist that are dedicated to evidence synthesis (e.g., Campbell Collaboration), and there are also state-level entities that push out specific models (e.g., multi-tiered system of supports initiatives). However, given the scope and focus of our paper, we provide actionable steps that researchers can take to advance dissemination research within school mental health.

Purpose of the Current Paper

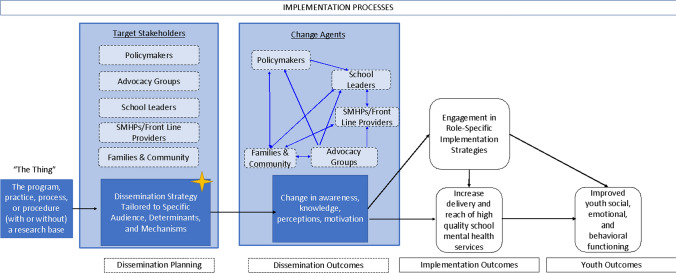

The purpose of this paper is to set forth an agenda for advancing dissemination research in school mental health which, at the present time, is virtually non-existent. To do this, we offer an enhanced definition of dissemination and a conceptual model for understanding dissemination in school mental health (see Fig. 1). Namely, we define dissemination strategies as intentional methods used to communicate strategically crafted information about an EBP to specific stakeholders to alter antecedents of behavior change (e.g., awareness, knowledge, perceptions, motivations) in ways that increase the likelihood of role-specific implementation behaviors. Building on other definitions of dissemination strategies (e.g., Rabin & Brownson, 2018), our definition incorporates a deliberate focus on achieving a specific outcome for a given stakeholder group (i.e., intentional), targeting motivational aspects of behavior change (i.e., antecedents), influencing precise mechanisms of change related to the outcome of interest (i.e., strategically crafted), that ultimately increases the probability of specific actions among a given stakeholder group (e.g., school leadership) that supports the translation of research into routine practice. Each of the core features of this model provides testable hypotheses regarding how to develop dissemination strategies that lead to a cascade of effects on dissemination, implementation, and child mental health outcomes (listed in Fig. 1 from left to right).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of dissemination and its impact on role-specific implementation activities and youth mental health outcomes

First, we discuss “the thing” (i.e., program or practice) that is being disseminated (Curran, 2020). Next, we discuss the various stakeholder groups that may be targets of dissemination (the audience). The aim of dissemination efforts is to target the awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation (i.e., dissemination outcomes) of these stakeholder groups to increase the probability of a stakeholder engaging in role-specific implementation behaviors. In turn, implementation behaviors increase the delivery and reach of high-quality school mental health services (i.e., implementation outcomes), that ultimately lead to improved child social, emotional, and behavioral functioning (i.e., youth outcomes). To supplement the explanation of this process, Table 1 describes different stakeholder groups, the contexts in which they are embedded, and the role-specific implementation behaviors they are capable of exhibiting to partake in translating research into practice.

Table 1.

Target stakeholders in context and specific behaviors to target for change

| Stakeholder | Context | Change Agent Role | Implementation-Specific Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Policymakers: those with authority to create and enforce governance due to elected or hired positions of influence | Local, state, national government | Creating governance and enabling resource allocation | Voting; writing bills; serving on a specific subcommittee; holding town hall meetings |

| Advocacy groups: those who mobilize over a dedicated cause to push or seek funding to advance a specific agenda | Local, state, or national communities operating in a specific service sector | Allocating resources; lobbying policy makers; functioning as an intermediary | Providing grant funding to support implementation projects; Providing technical assistance or professional development; hosting conferences, writing position papers; educating the public about solutions |

| School leaders: those in schools (school administrators; school board members) with authority to make decisions and allocate resources within a school system | Specific communities | Creating priorities, contexts, climates, expectations, and accountability systems; enabling resource allocation | Providing strategic communications about evidence-based practices; applying recognition and reward systems; making hiring decisions; providing feedback about implementation; deciding about program adoptions; overseeing the use of data to guide decision making |

| SMHPs/front line providers: those in schools (e.g., teachers, school counselors; school social workers, school psychologists who are expected to implement evidence-based practices | School buildings applying evidence-based practices with students | Increasing access to high-quality services directly and indirectly; implementation citizenship behaviors; champions | Implementing evidence-based practices with students; championing and advocating for services; providing consultation and peer support; staying abreast of the science |

| Family/Community members: those who are the recipients of services in the community or family members of recipients | Specific community settings and experiencing firsthand mental health needs | Creating pull; advocating for student needs to policymakers, leaders, and the public | Attending meetings; requesting specific services; offering peer support; voting for initiatives; partnering with others to affect change |

Following this, we discuss dissemination strategies (tailored to the target stakeholders) that target determinants (i.e., barriers that can obstruct or facilitators that can lead to successful dissemination) and mechanisms of change that explain how and why dissemination strategies work to influence specific outcomes of interest. Collectively, careful consideration of a target stakeholder group and key determinants and mechanisms of change facilitates dissemination planning. We describe dissemination outcomes broadly, focusing on antecedents of behavior change (e.g., awareness, knowledge, perceptions, motivation) and elaborate on how changes in these antecedents transform target stakeholders into change agents. We explain how each group can engage in role-specific implementation strategies that lead to implementation outcomes (e.g., increased delivery and reach of quality school mental health services) as well as youth outcomes (e.g., improved child social, emotional, and behavioral functioning). Ultimately, we hope that this paper serves to better differentiate dissemination from implementation and offers testable hypotheses related to each aspect of the enhanced definition of dissemination that can advance dissemination research in school mental health.

“The Thing”

“The thing” is an accessible term coined by Curran (2020) to refer to the wide range of innovations that may be the focus of dissemination and implementation. “The thing” could be a program (e.g., social-emotional learning program), a practice (e.g., positive greetings at the classroom door), a procedure (e.g., universal screening to detect students who need targeted intervention), a process (e.g., problem-solving process), or a policy (e.g., governance that requires bully prevention programming in all schools). Ideally, “the thing” being disseminated has defensible evidence to support its use to improve child outcomes, thereby making it an EBP. However, we acknowledge that there are a range of “things” that can be disseminated, some of which have not been researched and some of which research has indicated null or harmful effects. Although the goal is to disseminate EBPs, it is also important to understand how other kinds of information (that may be harmful) can come to be widespread. Thus, our model allows us to understand how a wide variety of “things” ultimately come to be a part of routine practice in schools through successful dissemination and implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption, fidelity, reach).

Target Stakeholders

As mentioned previously, dissemination strategies should be tailored to specific target stakeholders. The rationale for this is based in “audience segmentation,” which states that tailoring communication to groups who are similar to one another with regard to beliefs, identities, values, and roles will improve the effectiveness of dissemination (Purtle et al., 2018; Slater, 1996). Here, we briefly discuss different groups of individuals who play a role in disseminating school-based mental health services, how they are embedded in various contexts, their roles as change agents, and the specific behaviors they are in a position to engage in to support EBP implementation as part of routine school practice (see Table 1). These groups are based on specific roles, but they are not mutually exclusive. For example, individuals can function in multiple roles (e.g., an administrator who is also a parent could represent both school leadership and families and community members) and thus may engage in a wider range of actions that support implementation.

Policymakers

Policymakers refer to individuals who have the authority to create governance and enable resource allocation in the context of the local (e.g., mayor), state (e.g., governor), and/or national level (e.g., members of Congress). Policymakers are often elected or appointed officials who are supposed to serve the needs of a specific constituent group. Policymakers can create the realities for EBP implementation to happen through several behaviors, including voting, writing bills, arguing against the existing policy, serving on subcommittees, holding town hall meetings, and advocating to alter the climate around certain topic areas (Corrigan & Watson, 2003; Raghavan et al., 2008). The importance of policymakers cannot be overstated, as their decisions can set forth the conditions that override motives and actions of other stakeholder groups. For example, if a policy is enacted, then individuals in other groups (e.g., school leaders) must abide by this decision and implement accordingly—for better or for worse. Thus, it is imperative to reach policymakers through dissemination efforts to ensure they are knowledgeable and motivated to engage in behaviors that translate research into policy and create the conditions (e.g., resources, governance) for EBP implementation to happen. Work by Purtle and colleagues has pioneered dissemination research with policymakers to advance children’s mental health services (Purtle et al., 2017, 2018).

Advocacy Groups

Advocacy groups are networks of individuals whose goal is to advance a specific cause or agenda by organizing and mobilizing support. Advocacy groups tend to have membership and a mission to promote change by allocating resources, lobbying policymakers, disseminating information to members, and/or functioning as an intermediary organization that provides support to other organizations. To accomplish this, some advocacy groups provide grant funding to support implementation projects; some are organized to provide technical assistance or professional development; some host conferences; and some write position papers and create other resources to educate the public about particular ideas or topics, products, and innovations. For example, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) advocates for schools to provide and/or facilitate appropriate mental health services to all children. NAMI does this in a variety of ways, such as creating programs (e.g., NAMI Smarts for Advocacy) and offering full-day trainings to educate the workforce on particular topics and programs (Pandya, 2012). There is a diverse range of agendas advanced by advocacy groups, from implementing EBPs to adopting trendy products (that are not necessarily empirically based) to increasing awareness of a particular mental health topic (e.g., suicide), all of which are intended to result in more effective solutions that address specific issues within schools. Understanding the role of advocacy groups is imperative to informing effective dissemination. Their potential as change agents is significant when they engage in specific actions to support the implementation of EBPs among their members and other organizations within their network.

School Leaders

School leaders are individuals in school administration (e.g., superintendents, principals, directors of special education or curriculum) or school boards (e.g., elected members of the community) who act as gatekeepers to EBPs—often having the ability to make decisions about whether time, resources, and professional learning are dedicated to EBPs, and who have a significant influence on implementation climate and whether staff perceive that an EBP is expected, supported, recognized, and rewarded (Lyon et al., 2018). Their role as change agents is to define priorities, allocate resources, establish expectations and accountability systems, and recognize and reward EBP implementation (thereby determining the implementation climate). School leaders can accomplish this by creating strategic communications about EBPs, creating recognition and reward systems related to implementing EBPs, making specific hiring decisions, measuring implementation and providing feedback, and making decisions to allocate precious time, money, and resources. Effectively disseminating to school leadership is crucial, because when school leaders understand what the EBP is and why it will benefit their students, they are more likely to allow the program into their schools, devote time and resources, generate school staff enthusiasm, and encourage program fidelity (Fixsen et al., 2005; Flaspohler et al., 2008; Hodge & Turner, 2016).

School Mental Health Professionals (SMHPs) and Front Line Providers

SMHPs and front line providers are the individuals within school buildings who interface with children and are in the position to adopt and deliver specific mental health services. This group consists of individuals with formal training in health (e.g., school nurses) or mental health (e.g., school social workers, counselors, and psychologists), as well as individuals without such training (e.g., teachers or paraprofessionals) who are expected to implement EBPs (e.g., universal social-emotional curricula and classroom management strategies). SMHPs and front line providers act as change agents by delivering high-quality services directly and/or supporting mental health service delivery indirectly through consultation or coaching, engaging in implementation citizenship behaviors (i.e., going above and beyond to help others and keep informed; Ehrhart et al., 2015), and functioning as key opinion leaders or EBP champions (i.e., an influential peer in the school social network who promotes the implementation of an EBP; Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Dissemination to this group is essential, because ultimately EBP implementation boils down to providers deciding whether or not to invest their limited time and energy to implement a given EBP. This is why providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and motivation about EBPs affect behavioral implementation outcomes like adoption, fidelity, and sustainment (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Fixsen et al., 2005; Flaspohler et al., 2008; Forman et al., 2012).

Families and Community Members

Families and community members are the individuals who live in the community and are affiliated with the school system (e.g., parents/guardians, families, and friends of children with needs). As change agents, families and communities request or demand that specific needs are addressed (this is referred to as “pull;” Becker, 2015) and advocate for student needs to policymakers, leaders, and the general public. To do this, they can attend meetings, request specific services within their schools, offer peer support to other families, vote for initiatives, and partner with educational providers to advance school mental health. Although culture and lived experience should be taken into account when designing dissemination strategies for all stakeholder groups, strategies focused on families and community members must pay particular attention to these factors because of increased diversity and representation from marginalized communities compared to other stakeholder groups, which tend to be predominantly White and from privileged backgrounds. There is a need for dissemination strategies that communicate information to families and community members using culturally responsive language and examples to understand children’s mental health needs, what EBPs exist to address specific needs, how EBPs can support student wellbeing and success, and what behaviors they can engage in to create “pull” for specific EBPs in a school. Community-based participatory research offers a useful approach to engage families and communities in a collaborative research process to identify the best methods of communicating information (Chen et al., 2010).

Dissemination Strategies

Dissemination strategies are the actual planned methods to communicate strategically crafted information to a particular stakeholder group to achieve the goal of improving awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation. Although researchers have evaluated the utility of discrete strategies that target one specific component of dissemination packages (e.g., text campaigns, persuasive messaging; Chapman et al., 2020), evaluation of a multi-faceted approach that combines strategies (e.g., simultaneously considering audience segmentation, determinants, and mechanisms of change) is arguably warranted. This multi-faceted approach should theoretically allow researchers to more effectively change stakeholders’ awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivations (McCormack et al., 2013).

To help readers understand how to create a multi-faceted dissemination approach that could be evaluated in their own line of work, we begin by discussing three foundational questions that researchers should ask themselves. Specifically, (1) Who are the people receiving the information?, (2) How is the content being delivered?, and (3) What is the content being delivered? Consistent with Brownson et al. (2018) Model for Dissemination Research, the who, what, and how map onto the source and audience (who), channels (how), and message (what). To answer each of these questions, we provide guiding principles for creating an effective multi-faceted dissemination approach (see summary in Table 2).

Table 2.

Guiding principles for tailoring dissemination strategies to specific audiences, determinants, and mechanisms

| Who | How | What | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Who are the people receiving the information? | How (what mode/medium) is the content being delivered? | What content is being delivered? | |

| Guiding principles | Tailor messages according to the target stakeholder. Consider the target stakeholder’s… | Consider utilizing multiple mediums to deliver content, including, but not limited to… | Common forms for delivering content include, but are not limited to… |

| - Background | - Webinars | - Narratives | |

| - Goals | - Social media platforms | - Data | |

| - Sociodemographic factors | - Radio | - Visualizations | |

| - Cultural beliefs | - Television | Decisions regarding form should be informed by the “who” | |

| - Values | - Websites | Personalize risk data using stories, narratives, and anecdotes to the audience | |

| - Psychosocial determinants | - Town hall meetings | Frame messages to describe disadvantages associated with NOT adopting EBP (as well as advantages FOR adopting EBP) | |

| - Geographic location | - Individual meetings | ||

| - Language | - Research briefs | ||

| - Customs | |||

| Use clear, plain language (avoid jargon) | |||

| Key Determinants (barriers and facilitators) + Mechanisms (processes to achieve change) = Multi-faceted Dissemination Approach | |||

| After understanding the audience, how to access them, the preferred method of content delivery, and the content most relevant to them, you can develop a dissemination approach that overcomes barriers, leverages facilitators, and applies processes (emotional, cognitive, social) that maximize the likelihood of change in awareness, knowledge, perception and/or motivation | |||

| Key determinants | Access to stakeholder group, availability of stakeholder group, organizational leadership, openness to innovation, time, personnel, and budgetary resources | Preferred or routine method of intaking information, consider organizational leadership | Effective delivery of information in ways that motivate and increase behavioral intentions, consider the degree of readiness or openness to innovation |

| Mechanisms to target | Interest/engagement of stakeholder group, perceived relevance/importance by stakeholder group | Provide information (cognitive) | Knowledge, social norms, expectations, motivation |

| Increase attention (cognitive) | |||

| Stimulate emotion (emotion) | |||

| Facilitate social comparison (social) | |||

Who are the People Receiving the Information?

As discussed previously, identifying the target stakeholders is crucial to designing effective dissemination strategies. Each group of stakeholders will likely vary in background, identities, goals, and values, so utilizing audience segmentation is essential (Purtle et al., 2018; Slater, 1996). Best practices suggest tailoring messages based on the group’s sociodemographic factors, socio-political and cultural beliefs and values, psychosocial characteristics, and geographic location (Noar et al., 2007). By doing this, the targeted individuals are more likely to perceive the information to be personally relevant, and thus more likely to be persuaded by it. Indeed, tailoring messages increases the chance that material will be read by, understood by, and resonate with the recipient (Kreuter & Holt, 2001). Within this vein is the notion that messages should be responsive to local norms, such as culture, language, values, and traditions. Regardless of the audience, it is best to use clear, “plain” language that is accessible (Ashcraft et al., 2020). Although certain jargon may be well known in the research field (e.g., externalizing behavior problems), it is best to use terms that the target audience will understand (e.g., physical aggression, bullying, or off-task behavior rather than externalizing behavior problems). Given the heterogeneity within each targeted stakeholder group, it is imperative for those who are crafting the dissemination strategy to understand the people and their contexts. Understanding the context in which stakeholders reside is essential to identify factors that are likely to facilitate or inhibit the extent to which messages reach target stakeholders and are consumed in meaningful ways that allow stakeholders to feel confident they can make use of the information (Ashcraft et al., 2020).

How is the Content Being Delivered?

Next, researchers should consider the mode of delivery, which reflects the channel or medium through which the content is being delivered. The Diffusion of Innovations model outlines two broad modes of delivery: social and media channels of communication (Rogers, 2003). With the advent of social media, these two channels of communication have been merged to increase the rapid spread of information to target audiences. Information is now routinely disseminated through various modes, including (but not limited to) webinars, social media platforms, radio, television, websites, newsletters and other periodicals, town hall meetings, individual meetings, and research briefs. To extend the reach of dissemination efforts, it is recommended that researchers use multiple mediums for delivering content (McCormack et al., 2013). How the content is delivered needs to be aligned with stakeholder preference for consuming information and the routine ways in which they access information. Failure to take this into account will result in the selection of communication channels that do not reach the target stakeholder group.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to make recommendations regarding best practices for each mode, other researchers highlight key considerations depending on the mode of dissemination (e.g., Ashcraft et al., 2020). For example, when being interviewed, researchers should avoid giving yes or no answers; rather, they should disseminate key findings by elaborating on responses and highlighting key points. When disseminating via research briefs, the document should include information on how the stakeholder can expect to benefit from what is being proposed or described as well as provide recommendations for how recipients can use or apply the information (i.e., role-specific implementation behaviors).

What is the Content Being Delivered?

Finally, researchers should consider what content is being delivered. Content can be communicated in various forms, such as (but not limited to) narratives, anecdotes, data, and visualizations. The choice of what content to deliver should be informed by the stakeholder’s background knowledge, values, and goals. Sometimes these decisions can be informed by previous research (e.g., knowing that policymakers value cost-effectiveness data; Purtle et al., 2020). Other times, this information will not be available, so researchers will need to think critically about their target stakeholder group to determine what information is most essential (e.g., through a needs assessment). Regardless, the goal is to make sure the content is personally relevant to the stakeholder. Below is a brief description of some of the most common forms for delivering content: narratives, data, and visualizations.

Narratives convey information in the form of storytelling and can be written, aural, or visual. Narratives can effectively disseminate complex information to lay audiences (Scott et al., 2012), are perceived to be an appropriate method for communicating information, authentic (e.g., perceiving stories as relevant, accurate, truthful), and can spur action (e.g., to start a conversation about the topic) (Smith et al., 2015). For many stakeholder groups, local anecdotes may be more powerful than statistics or data-based information, as they may evoke more emotion and personal connection (see discussion of mechanisms below).

Data are often used to provide various statistics, such as the prevalence of an issue, effectiveness of a program at changing key outcomes, and whether a program is cost-effective. Instead of providing the same general information to everyone, data should be tailored to reflect what the target stakeholder values and needs. For example, data provided to school administrators may focus on cost or student test scores, but data provided to teachers may focus on reductions in disruptive behavior and teacher stress or increases in student time on-task. Data provided to local policymakers should be based on the local community, but data provided to state legislators should be at the state level (Purtle et al., 2020).

Visualizations (e.g., charts, graphs, infographics) are used to help people understand data (Tufte, 2001; Ware, 2013). Creating visualizations is recommended to help stakeholders digest complex information via a single image, which is the best way to share comprehensible information to laypeople (Wilke, 2019). Key considerations involve choosing the most appropriate type of plot or chart and the aesthetics, involving colors, symbols, and fonts. For example, if the researcher’s goal is to explain how students’ anxiety levels changed before and after an EBP (as compared to a control condition), they could create a graph showing trends of anxiety for both groups over time. This technique takes multiple pieces of information (e.g., group membership, time, and anxiety levels) and condenses it into one easy-to-understand image. Infographics have rapidly emerged as a way of disseminating information that combines narratives, data, and visualizations into brief reports that are visually designed to convey understandable content about a given topic (Alford, 2019).

It is also recommended to personalize risk data by using stories, narratives, and anecdotes (Davidson, 2017; Purtle et al., 2020). For example, instead of simply telling policymakers that a certain evidence-based program is effective at reducing bullying in schools, one could tell the story of a specific child (e.g., Bradley) who was a victim of bullying for many years and how it negatively impacted his life (e.g., developing anxiety, depression, and suicide risk). The story could continue to explain how a bystander intervention was implemented in his school that changed his experience for the better. This narrative personalizes the problem of bullying by talking about a specific individual who was affected, and importantly, the solution. To make storytelling even more impactful, one can use graphics or other visual materials to strengthen the message (Davidson, 2017); for example, presenting a video diary of Bradley telling his story or infographics showing the number of students who were bullied before the program was implemented compared to afterward.

Determinants

Determinants refer to barriers (the factors that make it more difficult to disseminate to a target stakeholder) and facilitators (the factors that make it easier to disseminate to a target stakeholder) of the success of dissemination strategies. Just as researchers must consider the who, how, and what questions, they must also educate themselves about the barriers and facilitators that are relevant to each stakeholder group and context. Once researchers identify the barriers and facilitators specific to their situation, they can select a strategy to either overcome the barriers, leverage the facilitators, or both. We first describe various barriers and facilitators that researchers might encounter, and then describe the mechanisms that explain how the selected strategies can work to overcome barriers or take advantage of facilitators. Thus, determinants and mechanisms are both tied to the development of dissemination strategies; specifically, determinants explain why a strategy does (or does not) work and mechanisms explain how a strategy works.

Some determinants are fixed or difficult to change (e.g., a target stakeholder’s age, the structure of an organization), whereas other determinants are more malleable (e.g., access, availability, openness to making data-driven decisions). Increasingly, malleable determinants are being considered as possible mechanisms of change for dissemination and implementation strategies (Lewis et al., 2018). Thus, we focus on dissemination determinants that are malleable in response to intervention. We consider determinants to be hierarchical in nature, meaning that researchers should consider a sequence of determinants that are related to effectively carrying out a dissemination approach with target stakeholders. Specifically, researchers must first consider the barriers and facilitators for gaining access to the stakeholder. After obtaining access, researchers should then consider the barriers and facilitators for interfacing with the stakeholder.

How do we Gain Access to the Stakeholder?

Before any dissemination can occur, one must first gain access to the target stakeholder. The ease of accomplishing this depends on where the stakeholders are on the continuum from open access (e.g., can be easily reached by anyone) to closed access (e.g., can only be reached by individuals within an exclusive network). If stakeholders are open access, this acts as a facilitator, making it easier to find their contact information (email address, phone number, etc.) to initiate a conversation. However, if stakeholders are closed access, researchers need to think critically about how to overcome this barrier in order to reach their intended audience.

When planning for how to gain access to stakeholders within a closed network, researchers must work to identify gatekeepers who could be used as a stepping stone for connecting with target stakeholders. For instance, consider an example in which researchers want to get into contact with teachers in a certain school division. Principals are often the gatekeepers to teachers in their school, so researchers need to develop strategies to cultivate meaningful relationships with these gatekeepers. Though it is typically easy to find principal contact information, it may be more fruitful to arrange a personal introduction to the principal from someone they know. Researchers can brainstorm how they might leverage existing relationships with various points of connection (e.g., school psychologists, parents) to facilitate an introduction. This is advantageous not only because researchers can be introduced by a familiar face, but also because the person on the inside will know the preferred method to contact the principal. Once contact is made, it is recommended that researchers focus first on listening and/or giving and not asking. By doing this, researchers can foster a relationship with the stakeholder where trust is built. Then, down the road, researchers can leverage that relationship to disseminate information. Following the previous example, researchers may be well advised to listen to the principal about current challenges they face and provide them with training opportunities for their staff or other informational resources without any expectation of payback. Once the principal trusts the researcher to provide quality information, that relationship can be leveraged to disseminate research to the closed-access teachers in the school.

Although open access stakeholders are easier to reach compared to closed-access stakeholders, researchers should still think critically about the best way to initiate contact with these individuals. As an example, federal legislators in the USA are considered open access as they all must provide contact information on their websites for their constituents (who have the right to request meetings to discuss local issues). However, that does not mean it will be easy to actually schedule a meeting with the legislator. Before contacting legislators, it is best to identify someone who has an office within driving distance and also has priorities relevant to the researcher’s work. There will not always be overlap; nonetheless, finding common ground in interests can work as a facilitator. To schedule a meeting, researchers can either email, call, or utilize both modes of contact. It is critical to know that the staff members are the individuals who are receiving these emails, making them the key gatekeepers. Many researchers make the common mistake of undervaluing staff; instead, it is crucial to be extremely courteous and gracious to all staff members to help facilitate relationship building with the entire office and the legislator. Keep emails short and to the point, as staff will receive hundreds of emails a day. If emails are not returned, researchers can consider calling the office and requesting a meeting as well. Persistence is key, given how busy these offices are. One to two follow-ups per week is recommended, though keep in mind that how often or soon to follow up is a balancing act (Baker & Scott, 2019). The goal of the meeting should be the same as with other stakeholders: to build a trusting relationship, not to request anything (especially not to lobby; Ashcraft et al., 2020).

How do We Maximize the Interface with the Information?

Once researchers have gained access to the targeted stakeholders and formed an initial trusting relationship, they can move onto considering determinants and strategies to increase the likelihood that stakeholders will interface with the information to increase their awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation. Interfacing requires engagement that enables the stakeholder to take in the information. Some common determinants relevant to dissemination that determine whether stakeholders will interface with the information include organizational leadership, openness to innovation, access to training, and time/resource availability. Below we elaborate on two of these (organizational climate, time/resource availability) to provide examples for two different stakeholders (school leaders and policymakers).

A common determinant when disseminating to school leaders that influences whether they will interface with the shared information is organizational climate. Organizational climate refers to the shared perceptions of the work environment (Glisson & James, 2002); this might refer to the extent to which employees are willing to make changes or how supportive employees are of one another (Hoy et al., 2002). To illustrate how climate may impact dissemination efforts, imagine a scenario in which a researcher wants to change teachers’ motivation to implement an EBP focused on promoting a positive classroom climate characterized by high amounts of engagement. This EBP requires teachers to change their classroom techniques and to rely on other teachers for advice when they run into difficulties. It can be exceedingly difficult to motivate teachers to do this if they are, on average, not open to change in the classroom and do not have collaborative, supportive relationships with one another (making organizational climate a barrier). Recognizing this, researchers can preemptively plan strategies to change the climate by impacting leadership structures within the school. One way to do this is by identifying a champion within the school, defined as someone whose role is to help others see the advantages of making a change, mentor them through the change, and ultimately persuade others to adopt a new practice (Cranley et al., 2017). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found that champions are critical to influencing organizational structures, as evidenced by increased staff engagement, motivation, and faster adoption and persistence in the delivery of interventions (Wood et al., 2020). Research also suggests a two-step process often exists for champion-driven dissemination and adoption. First, teachers learn about an intervention from key opinion leaders who are frequently sought out for their advice. Second, teachers decide to actually use the intervention when observing teachers with similar patterns of advice-giving relationships (e.g., both teachers are newcomers who receive advice from the same teacher) using the intervention (Neal et al., 2011). The use of champions is a prime example of how common implementation strategies can be repurposed as a dissemination strategy to address barriers that would otherwise interfere with particular stakeholders interfacing with the information that is disseminated to them.

Another common example of a determinant for dissemination is that of time/resource availability, which is very common when trying to engage policymakers to interface with particular information. Although there is diversity in each office’s resources, in general, legislative offices have enormous demands on their time (Vandlandingham & Silloway, 2015) combined with a limited capacity for understanding research that is written for academic audiences (Oliver et al., 2014). This creates quite the barrier when researchers attempt to disseminate to policymakers and engage them in learning new information. Although the research on effective strategies for translating research with policymakers is limited (Choi, 2005), recent work has begun to examine determinants of research use in policymaking (Purtle et al., 2021). Furthermore, a multi-faceted approach known as the Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) model has shown particular promise to increase policymaker engagement with research information (Crowley et al., 2018, 2021).

The RPC is a formal model that aims to bridge the gap between researchers and policymakers by first identifying legislative needs and then employing a “rapid response researcher network” to address those needs. However, implementing the entire RPC model is costly. Although it is not feasible for a given researcher to implement the entire model, there are general principles that can be drawn from the RPC that can be used to guide dissemination efforts. First, it is suggested that researchers approach dissemination efforts through a non-partisan lens, focusing on building a trusting relationship with the intended policymaker that is transparent and impartial (Fox, 2005). Although it may seem intuitive to come to a policymaker with a set agenda, that can be counterproductive. If policymakers perceive you to be lobbying or pushing for a particular issue, trust can decrease and thus reduce the likelihood of developing a lasting relationship where policymakers value researcher input. Thus, it is more productive to come to policymakers and ask what their needs are. Approaching this in a conversational way (e.g., If you could prevent any school mental health problem, what would it be?) can help with engagement and relationship building. After a need has been identified, it is recommended that researchers create short-term action steps that can be carried out in a timely manner (e.g., one month or less). Although the timeline may seem short for researchers, it is critical to acknowledge that things move much faster in policy, so researchers need to be prepared to adapt. Indeed, delivering products in a timely manner is considered essential for dissemination efforts (Ashcraft et al., 2020). As a few examples of short-term action steps, researchers could collect and summarize relevant resources (e.g., what EBPs exist for reducing depression?) or solicit professional networks for consensus on a certain topic of interest (e.g., what does the National Center for School Mental Health believe is the best way to approach virtual learning environments during COVID-19?). Whatever is decided, the key is to approach the dissemination effort in a collaborative way where researchers work alongside policymakers as a team, which increases their engagement with the information being communicated to them (i.e., interfacing). After delivering the agreed upon information, researchers can then repeat the process to further strengthen the relationship and continue dissemination efforts.

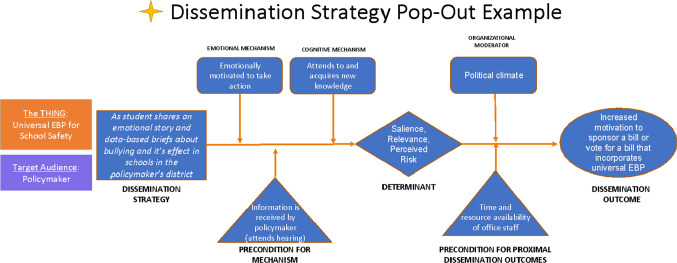

Mechanisms

Within dissemination science, mechanisms of action are the processes through which dissemination strategies work to achieve dissemination outcomes. Most mechanisms activated via dissemination strategies are cognitive, emotional, social, or a combination (see Fig. 2). When dissemination strategies are designed for maximum effect, the mechanism(s) that most powerfully impact the desired outcome(s) must be activated. In contrast to implementation outcomes that include behavioral variables such as adopting an EBP, delivering it with high fidelity, and sustaining implementation over time, dissemination outcomes that precede and overlap with those implementation behaviors include cognitive and emotional variables such as knowledge, attitudes (e.g., outcome expectancy), and motivation. In order to successfully increase these dissemination outcomes, mechanisms such as attention, emotional processing, and social- or self-referencing may be activated.

Fig. 2.

Causal pathway model linking dissemination strategies to mechanisms of change and determinants of outcomes

The mechanisms at play targeted by dissemination strategies may be activated to increase a particular outcome in a one-to-one fashion, or a single mechanism may impact multiple outcomes simultaneously. For example, one cognitive dissemination mechanism (attention) may be used to increase the stakeholder’s factual knowledge about an EBP, to improve positive perceptions about the EBP, and to strengthen expectations about desirable EBP effects, all within one well-designed dissemination communication. Without ensuring the stakeholder’s attention, a message’s information cannot be received; thus, successful dissemination strategies devote considerable effort to tailoring the message to the audience in ways that increase their attention (Hawkins et al., 2008). For example, a short brief that includes striking statistics from the policymaker’s district presented in a visually compelling graph may successfully capture the stakeholder’s attention, and thus help them comprehend the information in the brief in a way that can produce changes in dissemination outcomes.

Alternatively, or simultaneously, a dissemination strategy may be designed to evoke the mechanism of emotional arousal. Emotional processing also impacts the way in which an audience encodes new knowledge, in addition to their motivation to change (Hawkins et al., 2008). A dissemination strategy might include elements that highlight differences between an audience’s goals and their current state, thus creating an experience of cognitive dissonance in an audience that produces emotional arousal and compels them to act in order to resolve this internal conflict. Alternatively, a powerful, emotionally provocative, and personally relevant message like that delivered during a public hearing by Bradly who was bullied may successfully evoke emotion and capture a stakeholder’s attention.

Another example of a widely employed mechanism in dissemination strategies is self-reference. When a message is tailored to be personally relevant to stakeholders’ ideologies and identities in question, it is more likely that they will pay attention, experience emotional arousal, and experience a shift in dissemination outcomes (e.g., knowledge, motivation, and outcome expectancy; Ho & Chua, 2013). Indeed, tailored messages (as opposed to non-tailored messages) are more likely to be paid attention to, remembered, considered to be interesting and important, and discussed with others (Kreuter & Holt, 2001). Similarly, individuals are often influenced by social norms (i.e., what others in their group believe or do; Goldstein et al., 2008); thus, dissemination messages that are framed around social norms (e.g., 80% of teachers find this strategy effective) may capture attention and motivate teachers toward implementation-specific behaviors, especially when the referent group includes others who are like and respected by the stakeholder (e.g., Niemiec et al., 2020). In this way, dissemination mechanisms may do more than serve as a direct line through which dissemination strategies impact outcomes—some mechanisms also serve to increase other mechanisms, thereby having cascading effects that ultimately impact dissemination outcomes.

As shown in Fig. 2 and as described above, a multi-faceted dissemination approach must consider not only the mechanisms (e.g., cognitive, emotional, social) but also the determinants that can facilitate the potential of these mechanisms in the stakeholder’s context. For example, in Fig. 2, it is critical that the relevant policymakers are present at the hearing, that the data presented are salient and relevant to the policymaker’s district, and that the timing is right (i.e., the political climate is such that constituents embrace the topic as important and that there are resources to address the issue). When these factors are considered together, the likelihood of a dissemination approach impacting antecedents of behavior change (i.e., dissemination outcomes) and subsequent role-specific implementation behaviors increases.

Dissemination Outcomes

Broadly defined, outcomes are what we achieve or produce as a result of what we do. As discussed previously, the goal of dissemination is to use intentional methods to communicate strategically crafted information about an EBP to specific stakeholders to change antecedents of behavior change (e.g., awareness, knowledge, perceptions, motivation) that increase the likelihood of role-specific implementation behaviors. Thus, dissemination outcomes are the antecedents of behavior change, such as awareness, knowledge, perceptions, and motivation. Though this is not an exhaustive list of dissemination outcomes, we offer the following definitions to clarify these four outcomes that successful dissemination strategies can impact. One, awareness is attention paid to particular information, information sources, or the consequences of that information (Schmidt, 2001). Two, knowledge is information about facts, procedures, or events (Banks & Millward, 2007). Three, perceptions entail the subjective interpretation and representation of information (e.g., attitudes, expectancies, emotional experiences; Wang & Ruhe, 2007). Four, motivation is the desire or willingness to do something or behave in a particular way (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Ideally, these outcomes will change for each policymaker, advocacy group, school leader, SMHPs/front line provider, and family or community—transitioning them from target stakeholders to change agents. However, given the common gap between knowledge and behavior or intention and behavior (Papies, 2017), research is needed to explore how to optimize dissemination strategies to narrow this gap.

Changes in dissemination outcomes, particularly motivation, are where dissemination ends and implementation picks up. Following this, stakeholders (now change agents) can become involved in role-specific implementation strategies (e.g., teachers implementing EBPs in the classroom, policy makers writing bills; see Table 1 for more examples), which increases delivery and access to quality school mental health services. However, implementation strategies are needed to increase the likelihood that stakeholders will enact the specific role-specific implementation behaviors they are motivated to exhibit. When taken together, dissemination and implementation can produce these and then lead to improved youth social, emotional, and behavioral health outcomes.

Examples in Context

Although researchers can improve dissemination outcomes by following the guidelines mentioned previously, successful dissemination (and subsequent adoption) does not occur inside a vacuum. Rather, success is also dependent on context and external factors that are often outside researchers’ control. As indicated by a recent review, dissemination is most effective when it considers contextual factors, is timely, and is relevant (Ashcraft et al., 2020). To illustrate this, we present two examples of successful dissemination in context: one that benefited from timely, relevant funding (Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports [PBIS]; Sugai & Horner, 2006) and another that scaled quickly due to being timely and relevant to a national crisis (Second Step®; Frey et al., 2000).

PBIS is an evidence-based framework that targets behavioral and mental health problems in schools and has been successfully disseminated across the USA, as evidenced by large-scale adoption (implemented in 20,000 schools in 44 states; Horner, 2014) and policy change (legislation passed for mandated implementation of PBIS; Bradshaw et al., 2012). PBIS provides a strong example of successful dissemination that was supported by a wave of funding from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Programs (OSEP). Funding from OSEP facilitated unique collaborations between state departments of education, researchers at a university, non-profit organizations, and stakeholders in schools (e.g., administrators, teachers).

With large amounts of funding and an established infrastructure in place, dissemination was facilitated in various ways. For example, the collaboration addressed the barrier of reaching closed-access stakeholders, making it much easier for researchers to not only gain access to, but also interface with, school administrators and teachers. Furthermore, the funding allowed researchers to continually collect data and evaluate the framework, which they used to make data-based reports that could be tailored to stakeholders’ priorities (e.g., to address policymakers’ pressing needs). These reports were then made available to all stakeholders for free on an easily accessible website, which is crucial for dissemination efforts. In addition to data, PBIS was able to distribute copious amounts of information in a variety of modes (e.g., videos, fact sheets, infographics, conference presentations) to deliver content (e.g., narratives, visualizations) to each stakeholder (e.g., educators, policymakers, parents) in a tailored way. Importantly, all materials were made freely available through the National PBIS Technical Assistance Center, which is not always feasible without funding. Taken together, PBIS utilized many of the dissemination strategies and guidelines discussed in this paper (though only a few examples are mentioned here). Although PBIS’ success can be attributed to their strategically targeted dissemination efforts, their efforts were also facilitated by a wave of timely and relevant funding from OSEP. Importantly, these dissemination efforts resulted in broader implementation (e.g., implementation in 20,000 schools; Horner, 2014), highlighting where dissemination ends and implementation picks up.

Another example, Second Step® (Frey et al., 2000), is a program that takes a comprehensive approach to implementing social-emotional learning in schools. Although Second Step was designed to address a variety of behaviors (e.g., social skill drug use, aggression), it was recognized as a violence prevention program in 1999 when the Columbine shooting occurred. In the aftermath of this national crisis, policymakers, families and communities, and school leadership were looking for ways to prevent future school shootings. Given Second Step® existed in a relatively small competitive pool of programs, was relevant to the issue at hand and easily accessible, it made it easier for decision makers to learn about the program. The interest led to an infusion of resources for the organization who developed and disseminated Second Step®—Committee for Children. With the resources, Committee for Children has been able to develop more strategic advertising and marketing approaches to achieve dissemination outcomes. As a result, it has been estimated that Second Step® is in schools reaching over 16.5 million children across the globe (Committee for Children, 2021), providing further evidence of its dissemination success (although implementation success has been more variable). Following the rapid adoption and scaling of Second Step ®, it was researched extensively, with 35 studies conducted to evaluate its effectiveness from 1989 to 2012 (Clearinghouse, 2013). This is a unique example of how a social event can serve as a catalyst to facilitate dissemination of a given program, and therefore adoption and scaling, of a program.

Conclusion

In this paper, we provide an enhanced definition of dissemination; a conceptual model to illustrate how effective dissemination can lead to changes in implementation and, ultimately, youth outcomes; and guiding principles so researchers can begin to evaluate them and further inform dissemination science and practice. We also aimed to create a clear differentiation between dissemination and implementation, both of which are deserving of increased study. We hope this framework helps researchers to improve their own dissemination efforts, and guides future dissemination research in school mental health. Although dissemination is not a cure-all to address the gap between EBPs and real-world implementation, it is a key ingredient that can facilitate efforts among stakeholders to ultimately improve child and youth mental health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the School Mental Health Research Summit for providing the opportunity to network with colleagues on topics of shared interest, which is how this manuscript came about.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript conception and writing. All authors collaborated to write drafts of the manuscript, prepare tables and figures, provide comments, and complete revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Stephanie K. Brewer was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (F32 MH116623) during the preparation of this manuscript. Clayton R. Cook was supported by the Institute of Educational Sciences (R30 5A170292).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, Sklar M. Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35:255–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alford, K. (2019). The rise of infographics: Why teachers and teacher educators should take heed. Teaching/Writing: The Journal of Writing Teacher Education, 7(1), 7. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/wte/vol7/iss1/7

- Ashcraft LE, Quinn DA, Brownson RC. Strategies for effective dissemination of research to United States policymakers: A systematic review. Implementation Science. 2020;15(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker E, Scott T. Training activity: Meeting with representatives. Washington, DC: Report created for Research-to-Policy Collaboration; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banks AP, Millward LJ. Differentiating knowledge in teams: The effect of shared declarative and procedural knowledge on team performance. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2007;11(2):95–106. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.11.2.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SJ. Direct-to-consumer marketing: A complementary approach to traditional dissemination and implementation efforts for mental health and substance abuse interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2015;22(1):85–100. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Pas ET, Bloom J, Barrett S, Hershfeldt P, Alexander A, McKenna M, Chafin AE, Leaf PJ. A state-wide partnership to promote safe and supportive schools: The PBIS Maryland initiative. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39(4):225–237. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Research full report: Getting the word out: New approaches for disseminating public health science. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2018;24(2):102. doi: 10.1097/phh.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Jacobs JA, Tabak RG, Hoehner CM, Stamatakis KA. Designing for dissemination among public health researchers: Findings from a national survey in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(9):1693–1699. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.301165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E, Haby MM, Toma TS, de Bortoli MC, Illanes E, Oliveros MJ, Barreto JOM. Knowledge translation strategies for dissemination with a focus on healthcare recipients: An overview of systematic reviews. Implementation Science. 2020;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-0974-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PG, Diaz N, Lucas G, Rosenthal MS. Dissemination of results in community-based participatory research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(4):372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BCK. Can scientists and policy makers work together? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59:632–637. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clearinghouse, W. W. (2013). US department of education, institute of education sciences, what works Clearinghouse. Retrieved from http://whatworks.ed.gov.

- Committee for Children. (2021). Second Step: Success stories. Retrieved from https://www.secondstep.org/success-stories

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Factors that explain how policy makers distribute resources to mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54(4):501–507. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. R., & Southam-Gerow, M. A. (2020). Dissemination of evidence-based treatments for children and families in practice settings. In Handbook of evidence-based therapies for children and adolescents (pp. 331–343). Springer, Cham.

- Cranley LA, Cummings GG, Profetto-McGrath J, Toth F, Estabrooks CA. Facilitation roles and characteristics associated with research use by healthcare professionals: A scoping review. British Medical Journal Open. 2017;7(8):e014384. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley M, Scott JTB, Fishbein D. Translating prevention research for evidence-based policymaking: Results from the research-to-policy collaboration pilot. Prevention Science. 2018;19(2):260–270. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0833-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, D. M., Scott, J. T., Long, E. C., Green, L., Israel, A., Supplee, L., Jordan, E., Oliver, K., Guillot-Wright, S., Gay, B., & Storace, R. (2021). Lawmakers' use of scientific evidence can be improved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 10.1073/pnas.2012955118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Curran GM. Implementation science made too simple: A teaching tool. Implementation Science Communications. 2020;1(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00001-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson B. Storytelling and evidence-based policy: Lessons from the grey literature. Palgrave Communications. 2017;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC. Motivation for change: Implications for substance abuse treatment. Psychological Science. 1999;10(3):209–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duong, M. T., Bruns, E. J., Lee, K., Cox, S., Coifman, J., Mayworm, A., & Lyon, A. R. (2020). Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Innovations in mental health services implementation: A report on state-level data from the US evidence-based practices project. Implementation Science. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart MG, Aarons GA, Farahnak LR. Going above and beyond for implementation: the development and validity testing of the Implementation Citizenship Behavior Scale (ICBS) Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0255-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Koch JR, Brady C, Meszaros P, Sadler J. Community and school mental health professionals’ knowledge and use of evidence based substance use prevention programs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(4):319–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0422-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., & Friedman, R. M. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-MonographFull-01-2005.pdf

- Flaspohler P, Duffy J, Wandersman A, Stillman L, Maras MA. Unpacking prevention capacity: An intersection of research-to-practice models and community-centered models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41(3–4):182–196. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SG, Fagley NS, Chu BC, Walkup JT. Factors influencing school psychologists’ “willingness to implement” evidence-based interventions. School Mental Health. 2012;4(4):207–218. doi: 10.1007/s12310-012-9083-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox DM. Evidence of evidence-based health policy: the politics of systematic reviews in coverage decisions. Health Affairs. 2005;24:114–122. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Hirschstein MK, Guzzo BA. Second Step: Preventing aggression by promoting social competence. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2000;8(2):102–112. doi: 10.1177/106342660000800206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23:767–794. doi: 10.1002/job.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein NJ, Cialdini RB, Griskevicius V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research. 2008;35(3):472–482. doi: 10.1086/586910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. iffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins RP, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, Fishbein M, Dijkstra A. Understanding tailoring in communicating about health. Health Education Research. 2008;23(3):454–466. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S., & Chua, H. F. (2013). Neurobiological bases of self-reference and deliberate processing in tailored health communication. In Social neuroscience and public health (pp. 73–82). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6852-3_5

- Hodge LM, Turner KM. Sustained implementation of evidence-based programs in disadvantaged communities: A conceptual framework of supporting factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2016;58(1–2):192–210. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R. H. (2014). Using PBIS to make schools more effective and equitable. In Southern region student wellness conference, Indian Wells, CA.

- Hoy WK, Smith PA, Sweetland SR. The development of the organizational climate index for high schools: Its measure and relationship to faculty trust. The High School Journal. 2002;86(2):38–49. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2002.0023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Bernhardt JM. Reframing the dissemination challenge: A marketing and distribution perspective. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2123–2127. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.155218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Holt CL. How do people process health information? Applications in an age of individualized communication. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10(6):206–209. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux P, Denis JL, Tailliez S, Hivon M. Dissemination of health technology assessments: Identifying the visions guiding an evolving policy innovation in Canada. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2005;30(4):603–642. doi: 10.1215/03616878-30-4-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C. C., Klasnja, P., Powell, B. J., Lyon, A. R., Tuzzio, L., Jones, S., … & Weiner, B. (2018). From classification to causality: Advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lyon, A. R., Whitaker, K., Locke, J., Cook, C. R., King, K. M., Duong, M., … & Aarons, G. A. (2018). The impact of inter-organizational alignment (IOA) on implementation outcomes: Evaluating unique and shared organizational influences in education sector mental health. Implementation Science, 13(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCormack, L., Sheridan, S., Lewis, M., Boudewyns, V., Melvin, C. L., Kistler, C., Lux, L.J., Cullen, K., & Lohr, K. N. (2013). Communication and dissemination strategies to facilitate the use of health-related evidence. In Database of abstracts of reviews of effects (DARE): Quality-assessed reviews. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]