Abstract

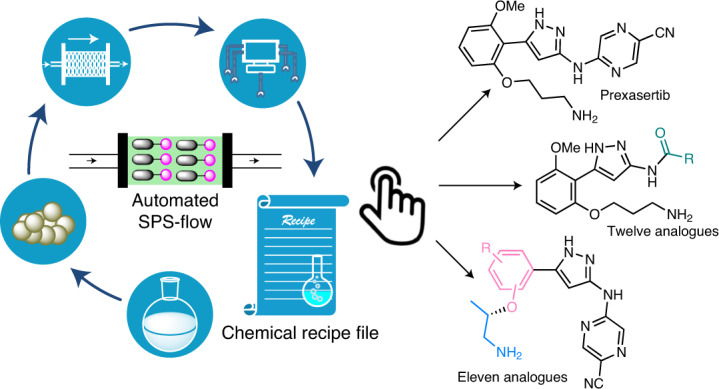

Recent advances in end-to-end continuous-flow synthesis are rapidly expanding the capabilities of automated customized syntheses of small-molecule pharmacophores, resulting in considerable industrial and societal impacts; however, many hurdles persist that limit the number of sequential steps that can be achieved in such systems, including solvent and reagent incompatibility between individual steps, cumulated by-product formation, risk of clogging and mismatch of timescales between steps in a processing chain. To address these limitations, herein we report a strategy that merges solid-phase synthesis and continuous-flow operation, enabling push-button automated multistep syntheses of active pharmaceutical ingredients. We demonstrate our platform with a six-step synthesis of prexasertib in 65% isolated yield after 32 h of continuous execution. As there are no interactions between individual synthetic steps in the sequence, the established chemical recipe file was directly adopted or slightly modified for the synthesis of twenty-three prexasertib derivatives, enabling both automated early and late-stage diversification.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Solid-phase synthesis, Synthetic chemistry methodology, Automation, Flow chemistry

Although strategies for the automated assembly of compounds of pharmaceutical relevance is a growing field of research, the synthesis of small-molecule pharmacophores remains a predominantly manual process. Now, an automated six-step synthesis of prexasertib is achieved by multistep solid-phase chemistry in a continuous-flow fashion using a chemical recipe file that enables automated scaffold modification through both early and late-stage diversification.

Main

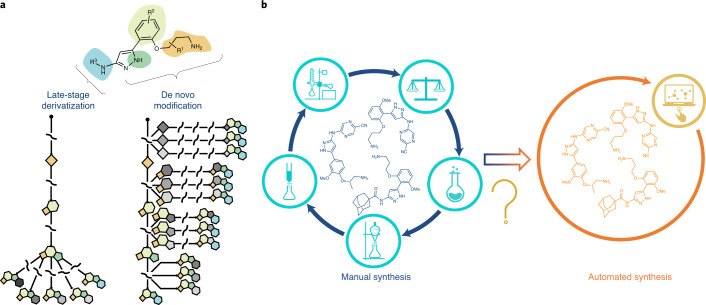

Multidimensional diversification for hit-to-lead optimization for the selection of clinical candidates represents an integral part of pharmaceutical drug discovery. Exploring the diverse chemical space starting from a potential lead compound is a routine practice in medicinal chemistry to understand structure–activity relationships, optimize the on-target potency, and improve absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion properties; however, experimental synthesis is a labour-intensive undertaking as chemists must invest substantial time and effort in repetitive reaction manipulation and downstream purification. In this regard, late-stage derivatization or functionalization is particularly appealing as it can quickly and directly access chemical entities based on a common intermediate without resorting to laborious de novo syntheses1 (Fig. 1a). Although late-stage functionalization has gathered substantial momentum in recent years1,2, only specific sites of the molecule can normally be functionalized, and selectivity and functional group tolerance can be problematic. By stark contrast, diversification through early stage functionalization or de novo modification could potentially modify any site of the molecule to allow molecular editing at will, but it has seldom been approached due to the cumbersome nature of the repetitive multistep synthesis for each modification (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Derivatization for molecule optimization.

a, Late-stage derivatization enables rapid change of the properties of molecules, but only limited sites of a molecule can be selectively functionalized. Early stage derivatization or de novo modification, on the other hand, could potentially modify any site of the molecule at will, but has to rely on cumbersome de novo multistep synthesis. b, A transition to automated synthesis can eliminate the tedious multistep procedures inherent to manual synthesis; however, despite recent advances, automated multistep synthesis still faces obstacles such as limited synthetic steps and narrow reaction scopes.

On the other hand, the transition from manual synthesis to the automated assembly of pharmaceutical molecules has allowed improvements in efficiency, scalability, safety and reproducibility, and is therefore of widespread academial, industrial and societal interest3,4 (Fig. 1b); however, other than the well-defined methods for automated peptide5 and oligonucleotide6 synthesis (and increasingly oligosaccharides7) in which the molecules are composed of repeating functional units, the synthesis of small-molecule-based active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) remains predominantly a manual process due to the structural diversity. In this context, recent emerging technologies such as iterative deprotection–coupling–purification sequences8–10, robotic systems driven by a chemical programming language11, end-to-end on-demand continuous-flow synthesis12 and radial synthesis13 have revolutionized the automated synthesis of APIs. Compared with conventional stirred-reactor vessels, continuous-flow reactors have several notable processing advantages, including improved mass and heat transfer, enhanced mixing efficiency, better reproducibility, improved safety, reduced footprint and facile scalability14,15. Multistep continuous-flow syntheses also enable the telescoping of several steps into a single and uninterrupted synthetic process, which circumvents the need to purify and isolate intermediates16–18. However, it is worth noting that fully continuous-flow syntheses rarely exceed two steps before offline purification19. To realize a fully multistep continuous-flow synthesis is enormously challenging, mainly due to issues originating from solvent and reagent incompatibility, the accumulation of side-products, risk of clogging and mismatch of timescales between steps in a processing chain20,21. Although in-line purification strategies such as phase separators12 have been applied (Supplementary Fig. 1), solvent and reagent incompatibilities between steps still limit the maximum number of steps in continuous-flow syntheses19. The Ley group has pioneered multistep flow syntheses enabled by flowing reactants through polymer-immobilized reagents and scavengers, thereby avoiding interference of leftover reagents in subsequent transformations22,23; however, the downside of this method is the requirement of the efficient preparation and regeneration of a number of reagent and scavenger columns (Supplementary Fig. 1).

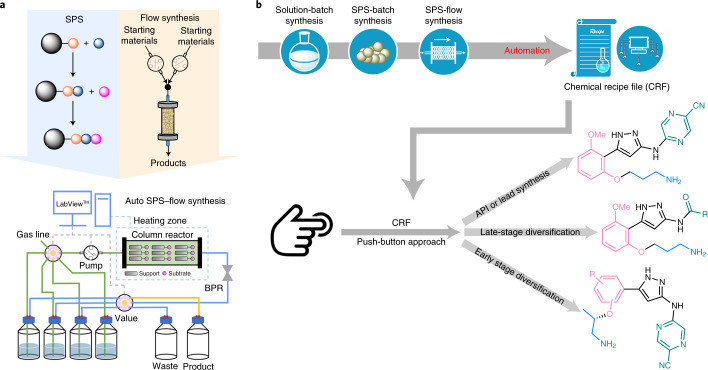

Since its original development in the 1950s by Robert Bruce Merrifield24, solid-phase synthesis (SPS) has become an important branch of organic synthesis25. In this technique, unlike reactions conducted in a mobile phase, the starting substrates are bound to a solid support material and grow step-by-step under sequential treatment with various reagent solutions. The key advantage of SPS is that it circumvents tedious intermediate isolation and purification procedures, and instead uses simple filtration. In this manner, the Ley group has pioneered the application of the catch and release strategy for the synthesis of feedstock chemicals26, reagent preparation27 and purification28 in multistep continuous-flow synthesis. Although there have been numerous examples of SPS-based natural product syntheses in batch29–31, SPS-based flow methods have not been applied to multistep non-peptide API synthesis in an end-to-end fashion32. On close analysis of the top 200 small-molecule pharmaceuticals (by retail sales in 2018; ref. 33), we envision that 73% of the single pharmaceutical molecules among them could potentially be synthesized by SPS (Supplementary Table 11). We therefore aspired to develop a new prototype for the automated synthesis of non-peptide APIs through the merger of SPS and flow synthesis (Fig. 2a). This method is in stark contrast to reported continuous-flow multistep syntheses. The target molecule grows on a solid support while all reagents and catalysts stay in the mobile phase; the product is detached from the resin at the last step followed by a single purification to afford the pure product. This strategy avoids the problem of reagent/solvent/by-product incompatibility between synthetic steps and enables automation with a longer synthetic steps and a much wider range of reaction conditions and reaction types.

Fig. 2. Schematic of the development of automated SPS-flow synthesis of APIs and derivatives.

a, Merging SPS with flow synthesis for automated API synthesis. b, The workflow for the development of a CRF for the automated synthesis of APIs (from solution-batch synthesis, via SPS-batch synthesis, to automated SPS-flow synthesis). The established CRF allows for digital storage of the preparation of the pharmaceutical molecule, and can be applied for derivatization of the lead compound through both early and late-stage diversification in a push-button fashion. BPR, back-pressure regulator.

Generation of a computer-based chemical recipe file (CRF) for a target molecule on a standardized platform enables pharmaceutical production in response to sudden changes in demand or need, such as in an epidemic or pandemic influenza outbreak11,12,34. We envisioned that establishing such a CRF using SPS-based flow technology requires three stages of development: (1) solution-batch synthesis; (2) SPS-batch synthesis; and (3) automated SPS-flow synthesis (Fig. 2b). Small molecules often possess inherent complexity associated with their molecular frameworks; as such, translating batch syntheses into automated liquid-phase continuous-flow syntheses can be challenging, often requiring new synthetic routes or new reagents and advanced purification techniques. Moreover, the number and sequence of units in a continuous processing cascade are tailored to match a specific synthetic route, and it is difficult to reconfigure a system constructed for a specific molecule to another target. This limits the widespread adoption of automated flow syntheses, as one may question whether the convenience afforded by automation of a specific target is worth the considerable effort required to develop such a protocol. By contrast, the translation from solution-batch synthesis to SPS-flow synthesis is much more straightforward for several reasons. First, each step is performed independently, thus avoiding reagent/solvent/by-product incompatibility issues. Next, unlike liquid-phase continuous-flow synthesis, there is no limitation on reaction time in SPS-flow synthesis, and mismatched timescales between subsequent steps do not affect performance. Third, the same system hardware can be reused for many targets without any physical reconfiguration35. Finally, clogging is less problematic as a column reactor with a large threshold filter can be applied. SPS-flow synthesis can substantially reduce the complexity, cost and footprint of the infrastructure needed, and dramatically simplify and accelerate the translation of solution-batch syntheses to automated SPS-flow CRFs. The established CRFs can be directly adopted or slightly modified for the automated synthesis of analogues from a lead compound, allowing both early and late-stage diversification for molecule editing at will (Fig. 2b).

To demonstrate the feasibility of this strategy, prexasertib, a small ATP-competitive selective inhibitor of checkpoint kinases 1 and 2 (CHK1 and CHK2) developed by Eli Lilly36,37, was synthesized via a streamlined, six-step synthesis using a compact SPS-flow platform. Twenty-three analogues were prepared through a push-button approach with or without slight adjustments of the established CRF as a proof-of-concept.

Results and discussion

SPS-flow platform assembly

SPS-flow synthesis addresses each synthetic step independently by simple washing and filtration between each step, and the physical hardware can be reused for different types of reactions. We thus assembled a modular platform, consisting of a high-pressure pump equipped with two channels, a peristaltic pump, four multiway selection valves, a stainless-steel column reactor (fitted with frits with 75 µm pores; Supplementary Fig. 6), a digital heating plate and three back-pressure regulators (Supplementary Fig. 2). Two of the multiway valves allow the routing of reagents and solvents through the column reactor. The third valve either loops the reactor outflow back into the column reactor or directs it to the end waste or product container. The gas line is controlled by the fourth valve to thoroughly purge any solvent residue. The whole system is controlled by a LabVIEW interface (Supplementary Fig. 11), which gives a complete description of the connectivity of all units, and facilitates the movement of reagents and solvents from specific stock locations to the column reactor in a circulative or one-way flow fashion. This platform represents one of the simplest and most compact systems for automated multistep synthesis, and it can fit within the area of half a standard fume hood (56 cm width × 88 cm length × 56 cm height; Supplementary Fig. 2).

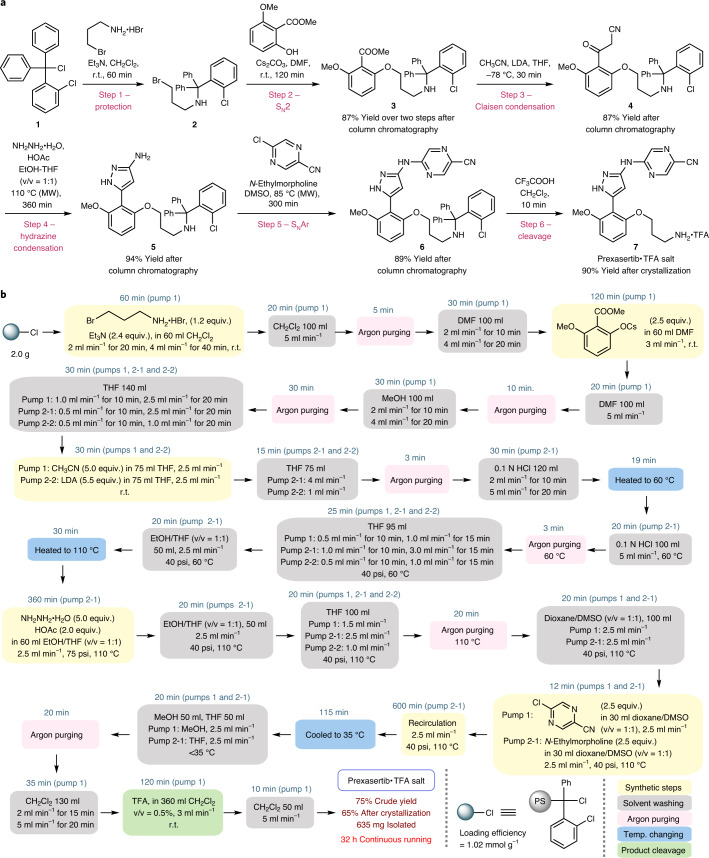

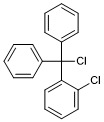

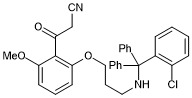

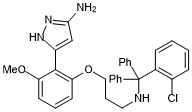

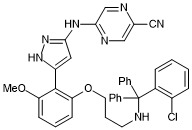

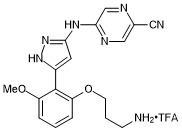

Development of a computerized CRF for the automated synthesis of prexasertib

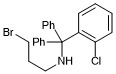

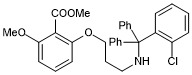

Prexasertib was chosen for proof-of-concept study. Its synthesis can be achieved in a linear fashion with a protection step at the outset. A solid matrix can be applied as a protecting group without introducing further synthetic steps to anchor the starting material onto the solid matrix. An elegant seven-step synthesis of prexasertib was recently accomplished by researchers at Eli Lilly36, employing a continuous-flow process for the last three steps to achieve a kilogram-scale synthesis. To establish a robust computerized CRF for the automated synthesis of prexasertib, our study was initiated with the development of an efficient solution-batch synthesis (Fig. 3a). The synthesis commenced with protecting 3-bromopropylamine using 2-chlorotrityl chloride (1), which was used to mimic 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin, an inexpensive and commonly utilized resin in SPS. A subsequent SN2 reaction between the substituted phenoxide and primary bromide 2 delivered product 3 bearing an aryl ester moiety. Keto-nitrile intermediate 4 was prepared by a Claisen condensation between aryl ester 3 and lithiated acetonitrile38, followed by a hydrazine condensation and an SNAr similar to Eli Lilly’s protocol. Final removal of the 2-chlorotrityl group by treatment with TFA produced prexasertib as TFA salt 7. The Claisen condensation using lithiated acetonitrile allowed a more straightforward route compared with previous syntheses. A six-step synthesis containing five purification-steps was therefore achieved to afford the TFA salt of prexasertib in 57% overall isolated yield.

Fig. 3. Development of automated SPS-flow synthesis of prexasertib.

a, Development of a six-step solution-batch synthesis of prexasertib, which is ready to be transformed into SPS. The 2-chlorotrityl protecting group was used to mimic the solid resin. b, A schematic of the established CRF for prexasertib based on the SPS-flow technology; the CRF was implemented using LabVIEW to enable automated synthesis. SNAr, nucleophilic aromatic substitution; DMF, dimethylformamide; LDA, lithium diisopropylamide; THF, tetrahydrofuran; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; MW, microwave; r.t., room temperature; psi, pound per square inch; PS, polystyrene resin.

Vital to the practicality of this strategy is the facile translation of the optimized solution-batch synthesis to the SPS-flow synthesis. 2-Chlorotrityl chloride resin was selected as the solid matrix. We found that the translation to SPS-batch synthesis was straightforward and no modification was required for the protecting, SN2, hydrazine condensation and cleavage steps. The Claisen condensation in SPS was conducted at room temperature for the flow synthesis, which was different from the conditions used in the solution-batch synthesis (−78 °C); however, the Thorpe reaction occurred at elevated temperatures, which consumed the starting nitrile39, and excess MeCN and LDA reagents were required to ensure a full conversion. The optimal conditions for the SNAr in solution-phase synthesis gave less than 30% conversion in SPS. We suspected that the low reactivity may be caused by the limited swelling of the polymer resin in the DMSO solvent, which may limit substrate diffusion into the matrix. Using 1,4-dioxane as a co-solvent—which allowed more pronounced resin swelling—successfully promoted the SNAr to full conversion. The purification was performed by a simple filtration between each step and a final crystallization from methanol and ethyl acetate. This six-step SPS afforded pure prexasertib TFA salt in 53% overall yield (Supplementary Fig. 9).

As we intended to establish an SPS-flow-based CRF for prexasertib and apply it to derivative synthesis (see below), we attempted a straightforward translation from the SPS-batch synthesis to SPS-flow synthesis without optimizing each transformation again (for example, reaction time, the amount of reagents), even though it is well established that the biphasic solid–liquid interaction is substantially intensified in the flow mode14,40. The direct translation from SPS-batch to SPS-flow may offer more efficient reactions to ensure reasonable conversions for a broad range of different substrates. The established SPS conditions were successfully transferred to the SPS-flow synthesis by incorporating solvent washing steps. Circulating flow was applied for transformations requiring longer reaction time (≥1 h, including the protection, SN2, hydrazine condensation and SNAr steps). Direct one-way flow was employed for the Claisen condensation and the final cleavage step. Argon purging was used to improve the washing efficiency and to mitigate clogging risks associated with the Claisen condensation, which involves the use of LDA. A CRF was therefore established as illustrated in Fig. 3b. Notably, LDA, which is an extremely moisture-sensitive reagent, was successfully incorporated in the middle of this multistep synthesis, which is challenging in solution-phase continuous-flow multistep syntheses due to reagent and solvent incompatibility. An automated push-button synthesis based on the CRF was achieved with LabVIEW programming, which specifies the process modules, the fluid and argon paths, the location of stock solutions and solvents, the flow rates and the temperature (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). A fully automated 32 h continuous synthesis with two grams of resin afforded 635 mg of prexasertib as the TFA salt (65% yield) after crystallization. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis showed that the purity of the product was >99.9% (Supplementary Fig. 16). An animation of the entire protocol is demonstrated in Supplementary Video 1. The digital defined CRF and the standardized reactor system allow the storage of this API synthesis digitally for implementation on demand.

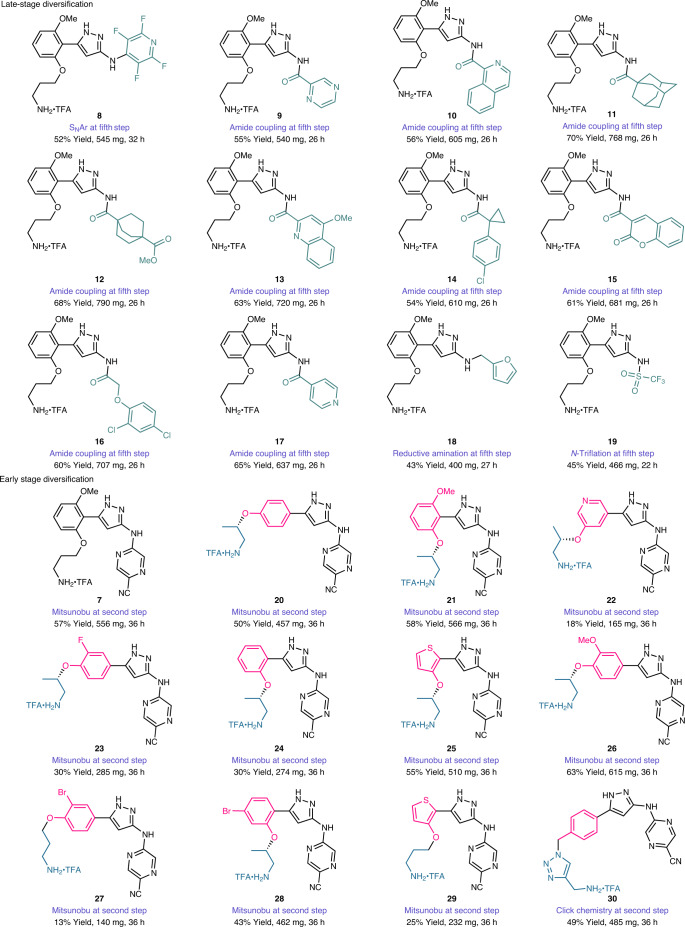

Automated synthesis of a library of prexasertib analogues

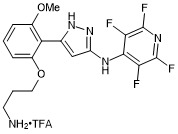

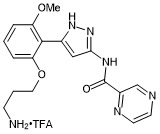

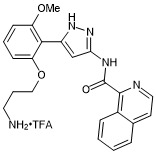

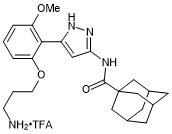

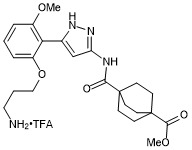

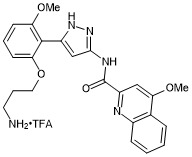

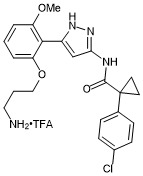

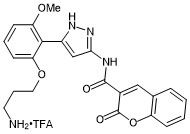

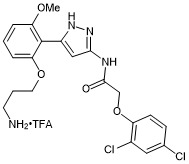

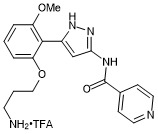

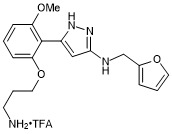

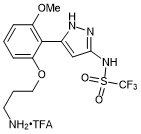

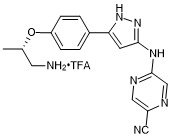

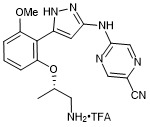

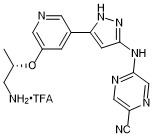

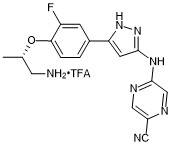

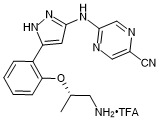

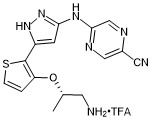

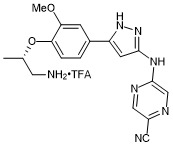

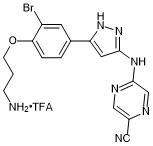

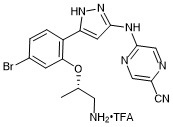

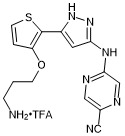

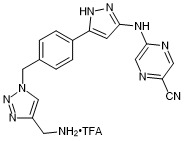

The most prominent advantage of the SPS-flow-based CRF is the versatility, which can be adapted to different types of chemistry, and allows each synthetic step to be considered independently that can in principle be replaced without disturbing the other steps. This enables not only late- but also early stage diversification in an automated manner, which is particularly useful for de novo design and synthesis of drug molecules where structure–activity relationship studies based on initial core structures are instructive for targeted selectivity profiles41. To showcase this capability, we prepared a library of twenty-three prexasertib analogues by directly applying the CRF or changing only one step in the six-step CRF including both early and late-stage diversification (Table 1). A simple condition evaluation and optimization for just the altered step was performed at the SPS-batch stage when switching reaction patterns to establish a modified CRF, which was then applied to automated SPS-flow synthesis. The generated CRFs were directly applied to different substrates at the automated SPS-flow stage for derivative synthesis. By replacement of 2-chloro-5-cyanopyrazine with pentafluoropyridine in the SNAr reaction, but otherwise following the same CRF, prexasertib analogue 8 was prepared in 52% isolated yield. Amide derivatives (9–17) were then accomplished in generally good yields by simply replacing the SNAr reaction with an amide coupling in the CRF, without altering the other steps. A fast cleaning procedure taking less than two hours was established between the production of each derivative (Supplementary Fig. 22). By replacing the SNAr transformation with a two-step reductive amination or an N-triflation transformation, 18 and 19 were produced in 43% and 45% yield, respectively. By conducting a Mitsunobu reaction in the CRF rather than an SN2 transformation in the second step, while keeping the other steps the same, the TFA salt of prexasertib (7) could still be generated in 57% yield. Different aryl and heteroaryl moieties could be incorporated into the scaffold by changing the stock reagents in the Mitsunobu reaction to realize early stage diversification, furnishing products 20–29 in 13–63% isolated yields, with some of the products being obtained in enantiopure form. The last analogue, 30, was specifically chosen to demonstrate the versatility and diversity of this CRF strategy. A click reaction was used instead of the original SN2 transformation to produce 30 in 49% isolated yield in a push-button approach followed by a simple off-line crystallization.

Table 1.

Automated synthesis of prexasertib and derivatives by simple adjustments of the established CRF

Conclusion

By integrating SPS and flow synthesis, we have developed a simple and compact platform for the on-demand automated synthesis of a drug molecule and its derivatives. Prexasertib was prepared in a six-step protocol in good yield as a proof-of-concept, and the generated CRF was modified for the synthesis of another twenty-three analogues by simply switching the stock reagents or changing only one of the synthetic steps. When compared with existing automated multistep syntheses of non-peptide pharmaceutical molecules, the merits of this strategy include: first, automation of multistep syntheses with longer steps, which are compatible with a much wider range of reagents (for example the pyrophoric LDA reagent) and reaction patterns by alleviating the reagent and solvent incompatibility issues—to the best of our knowledge, our synthesis of prexasertib represents the longest linear end-to-end automated synthesis of non-peptide APIs. Second, an extremely simple and compact platform (fit within the area of half a standard fume hood) compared with other automated multistep syntheses—this platform is versatile and can be used for different targets without physical reconfiguration. Third, straightforward establishment of the CRF by translation from solution-batch to SPS-flow synthesis (approximately six months to establish the CRF of prexasertib with the joint efforts of a postdoctoral fellow and a graduate student). Fourth, the synthesis of the target molecule can be stored digitally as a CRF for implementation on demand. Finally, the generated CRF can be directly adopted or slightly modified for the automated synthesis of lead derivatives through both early and late-stage diversification, enabling a push-button access to much wider areas of chemical space.

Analysis of the top-selling 200 small-molecule pharmaceuticals indicates that automated SPS-flow synthesis could potentially be applied to a wide range of pharmaceutical molecules. For the small molecules that lack an obvious handle for covalent attachment to a solid support, simultaneous advances in linker strategies42 and traceless SPS43,44 can substantially expand the scope of molecules that are amenable to this strategy. The desire for process intensification (for example, to decrease overall reaction time); the need to tolerate solid reagents; the development of more economic solid-supports with diverse functional anchors; the combination of reagent preparation, synthesis and downstream purification and formulation into a single, compact unit; the realization of large-scale production45; and parallel assembly of two SPS-flow column reactors or a solution-based continuous-flow system with a SPS-flow column reactor for convergent synthesis can further enhance the value and extensively expand the scope of this strategy. We anticipate that the integration of the SPS-flow technology with computer-guided molecule design and optimization, automated biological testing and feedback analysis will dramatically accelerate the time frames for the lead optimization process46.

Methods

Generation of the CRF for prexasertib

The synthetic routes and reaction conditions were obtained from optimized solution- and solid-phase syntheses in batch conditions (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 9). The conditions of each step were independently defined, including reagents, the amount of reagents, temperature, solvents and the reaction time (Supplementary Sections 4 and 5). The established SPS conditions were transferred to the SPS-flow synthesis by incorporating solvent-washing steps (Supplementary Table 2). Argon purging was used to improve the washing efficiency and to mitigate clogging risks. The CRF for perxasertib was therefore generated as illustrated in Fig. 3b, which was programmed and edited in the form of a Microsoft Excel file (Supplementary Table 3). The Excel file was saved as a tab-delimited.txt file, which can be loaded to the control program to achieve the automated synthesis.

SPS-flow system assembly and execution for automated synthesis of prexasertib

The SPS-flow system was assembled based on the established CRF (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 14), consisting of one peristaltic pump, one continuous syringe pump, two ten-port selection valves, two 16-port selection valves, one column reactor loaded with solid resins (2 g), one remote-controllable stir heat plate equipped with an oil bath, and a computer acting as the control station. All units were logically connected using perfluoroalkoxy tubing and accessories. Vessels filled with the solvents or reagent solutions, and vessels for waste and product collection, were placed in proper locations and connected to the valves accordingly (Supplementary Table 4). The size of the column reactor was defined based on the swelling property of the 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin in various solvents (Supplementary Fig. 10). The automation control program was developed on LabVIEW and the operation code is available in Github (see the Code Availability). The operation instructions have been described in Supplementary Section 7. The synthesis was initiated by pushing the start button on the program interface, and the automated operation lasted for 32 h. After the process was finished, the crude product in the collection vessel was concentrated and subjected to crystallization to give 635 mg of prexasertib as the TFA salt (65% yield). After a fast cleaning procedure (Supplementary Fig. 22), the SPS-flow system was ready for the next implementation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41557-021-00662-w.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–64, Tables 1–11, synthetic procedural details, automation development and implementation, high-resolution mass spectrometry, infrared data, NMR data and spectra, HPLC spectra.

Recording of the automated synthesis of prexasertib using the SPS-flow system.

Raw data for the bioactivity evaluation shown in Supplementary Fig. 23.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) of Singapore RIE2020 AME IRG (grant no. A1783c0013). We thank J. T. Njardarson for allowing us to reproduce and modify the poster ‘Top 200 small molecule pharmaceuticals by retail sales in 2018’ (see Supplementary Table 11).

(chloro(2-chlorophenyl)methylene)dibenzene

- PubChemID:

440065985

- InChIKey

JFLSOKIMYBSASW-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM1_ESM.mol (2KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM2_ESM.cdx (2.9KB, cdx)

3-bromo-N-((2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl)propan-1-amine

- PubChemID:

440065956

- InChIKey

BEFMADJPAQXHDJ-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM3_ESM.mol (2.4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM4_ESM.cdx (3.6KB, cdx)

methyl 2-(3-(((2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl)amino)propoxy)-6-methoxybenzoate

- PubChemID:

440065957

- InChIKey

HDTJJEVRWDVOJZ-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM5_ESM.mol (3.7KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM6_ESM.cdx (5.2KB, cdx)

3-(2-(3-(((2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl)amino)propoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-3-oxopropanenitrile

- PubChemID:

440065958

- InChIKey

NIGXEFPXXLNMPF-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM7_ESM.mol (3.8KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM8_ESM.cdx (5.3KB, cdx)

5-(2-(3-(((2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl)amino)propoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-amine

- PubChemID:

440065959

- InChIKey

ZNBVSMXXQLQDKZ-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM9_ESM.mol (3.8KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM10_ESM.cdx (5.3KB, cdx)

5-((5-(2-(3-(((2-chlorophenyl)diphenylmethyl)amino)propoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile

- PubChemID:

440065960

- InChIKey

COMHTKPNLCPNAJ-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM11_ESM.mol (4.6KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM12_ESM.cdx (6.4KB, cdx)

prexasertib trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065961

- InChIKey

KTEQSHLWYUJSGV-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM13_ESM.mol (3.4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM14_ESM.cdx (5.4KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-2,3,5,6-tetrafluoropyridin-4-amine trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065962

- InChIKey

AVURFVQGUYELKR-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM15_ESM.mol (3.5KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM16_ESM.cdx (5.5KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)pyrazine-2-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065963

- InChIKey

ACTGDMCNZNYRFF-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM17_ESM.mol (3.3KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM18_ESM.cdx (5.2KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)isoquinoline-1-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065964

- InChIKey

UIVOOBJZFWSBDP-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM19_ESM.mol (3.7KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM20_ESM.cdx (5.4KB, cdx)

(3r,5r,7r)-N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)adamantane-1-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065965

- InChIKey

BHHBYOZLCUSPAN-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM21_ESM.mol (3.7KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM22_ESM.cdx (4.5KB, cdx)

methyl 4-((5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)carbamoyl)bicyclo[2.2.2]octane-1-carboxylate trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065966

- InChIKey

NDSOAJZNQDCPEI-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM23_ESM.mol (4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM24_ESM.cdx (5.7KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-4-methoxyquinoline-2-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065967

- InChIKey

QHCZJKYWKWYAFU-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM25_ESM.mol (4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM26_ESM.cdx (5.9KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)cyclopropane-1-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065968

- InChIKey

LKCQGQOKSYZQHS-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM27_ESM.mol (3.7KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM28_ESM.cdx (5.4KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-2-oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065969

- InChIKey

RZVRXTILJMGJEO-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM29_ESM.mol (3.8KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM30_ESM.cdx (5.6KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)acetamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065970

- InChIKey

VTAWWVPCOYGVQQ-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM31_ESM.mol (3.7KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM32_ESM.cdx (5.6KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)isonicotinamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065971

- InChIKey

UUDMVEGBQSLENI-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM33_ESM.mol (3.3KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM34_ESM.cdx (4.3KB, cdx)

5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-N-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-amine trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065972

- InChIKey

WTIVJEKPAOVZSY-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM35_ESM.mol (3.1KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM36_ESM.cdx (4.1KB, cdx)

N-(5-(2-(3-aminopropoxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-1,1,1-trifluoromethanesulfonamide trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065973

- InChIKey

ROPGCAYTTZNKME-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM37_ESM.mol (3.3KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM38_ESM.cdx (5.5KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(4-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)phenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065974

- InChIKey

OXKHLTPQTHTZHB-MERQFXBCSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM39_ESM.mol (3.1KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM40_ESM.cdx (5.2KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(2-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)-6-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065975

- InChIKey

ZEJCCKVKWBFFMH-MERQFXBCSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM41_ESM.mol (3.4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM42_ESM.cdx (4.8KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(5-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)pyridin-3-yl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065976

- InChIKey

STYBUOXDFWFRFQ-PPHPATTJSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM43_ESM.mol (3.1KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM44_ESM.cdx (5.2KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(4-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)-3-fluorophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065977

- InChIKey

CHZKXCHKESRENW-PPHPATTJSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM45_ESM.mol (3.2KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM46_ESM.cdx (4.6KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(2-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)phenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065978

- InChIKey

LPMGNKITNNXTIX-MERQFXBCSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM47_ESM.mol (3.1KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM48_ESM.cdx (5.1KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(3-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)thiophen-2-yl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065979

- InChIKey

UBSQMGRLTNSSJW-FVGYRXGTSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM49_ESM.mol (3KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM50_ESM.cdx (4.4KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(4-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)-3-methoxyphenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065980

- InChIKey

ZAGPRNSEWNBGFZ-MERQFXBCSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM51_ESM.mol (3.4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM52_ESM.cdx (4.6KB, cdx)

5-((5-(4-(3-aminopropoxy)-3-bromophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065981

- InChIKey

YKPUKJUWEYFXED-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM53_ESM.mol (3.2KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM54_ESM.cdx (5.4KB, cdx)

(S)-5-((5-(2-((1-aminopropan-2-yl)oxy)-4-bromophenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065982

- InChIKey

FBTJUFFEZLWSEW-PPHPATTJSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM55_ESM.mol (3.2KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM56_ESM.cdx (5.3KB, cdx)

5-((5-(3-(3-aminopropoxy)thiophen-2-yl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065983

- InChIKey

UWVTYURKQMZZIT-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM57_ESM.mol (3KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM58_ESM.cdx (5.2KB, cdx)

5-((5-(4-((4-(aminomethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)phenyl)-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)amino)pyrazine-2-carbonitrile trifluroacetate

- PubChemID:

440065984

- InChIKey

FNUGKMBPJVPKMU-UHFFFAOYSA-N

- MDL Molfile

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM59_ESM.mol (3.4KB, mol)

- Chemdraw file

- 41557_2021_662_MOESM60_ESM.cdx (5.5KB, cdx)

Author contributions

J.W. conceived and designed the experiments. C.L., W.W., M.W. and W.C. performed the experiments. J.W., S.A.K., C.L. and M.W. analysed the experimental data. C.L. and J.R. built the SPS-flow reactor system. J.X. performed the programming for automated control. B.I.S. and L.-W.D. performed the preliminary biological screening. J.W. and S.A.K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All of the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. A video of the SPS-flow automated synthesis of prexasertib is recorded as Supplementary Video 1.

Code availability

The LabVIEW code for operating the SPS-flow automated synthesis in this study is available at https://github.com/nus-automated-flow-system/auto-SPS-Flow-Supplementary-Software.

Competing interests

J.W., S.A.K., C.L., W.W., W.C., M.W. and J.X. are inventors on International Patent Application PCT/SG2020/050603 filed by the National University of Singapore, which covers the synthesis of non-peptide small-molecules using the strategy of automated SPS-flow synthesis. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Chemistry thanks Kevin Cole, Christopher Gordon and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Saif A. Khan, Email: chesakk@nus.edu.sg

Jie Wu, Email: chmjie@nus.edu.sg.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41557-021-00662-w.

References

- 1.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P, Krska SW. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:546–576. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00628G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moir M, Danon JJ, Reekie TA, Kassiou M. An overview of late-stage functionalization in today’s drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019;14:1137–1149. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2019.1653850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trobe M, Burke MD. The molecular industrial revolution: automated synthesis of small molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:4192–4214. doi: 10.1002/anie.201710482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ley SV, Fitzpatrick DE, Ingham RJ, Myers RM. Organic synthesis: march of the machines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:3449–3464. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merrifield RB. Automated synthesis of peptides. Science. 1965;150:178–185. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3693.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarado-Urbina G, et al. Automated synthesis of gene fragments. Science. 1981;214:270–274. doi: 10.1126/science.6169150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeberger PH, Werz DB. Automated synthesis of oligosaccharides as a basis for drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:751–763. doi: 10.1038/nrd1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, et al. Synthesis of many different types of organic small molecules using one automated process. Science. 2015;347:1221–1226. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann JW, Blair DJ, Burke MD. Towards the generalized iterative synthesis of small molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018;2:0115. doi: 10.1038/s41570-018-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woerly EM, Roy J, Burke MD. Synthesis of most polyene natural product motifs using just twelve building blocks and one coupling reaction. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:484–491. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner S, et al. Organic synthesis in a modular robotic system driven by a chemical programming language. Science. 2019;363:eaav2211. doi: 10.1126/science.aav2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adamo A, et al. On-demand continuous-flow production of pharmaceuticals in a compact, reconfigurable system. Science. 2016;352:61–67. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee S, Guidi M, Seeberger PH, Gilmore K. Automated radial synthesis of organic molecules. Nature. 2020;579:379–384. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman RL, McMullen JP, Jensen KF. Deciding whether to go with the flow: evaluating the merits of flow reactors for synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7502–7519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutmann B, Cantillo D, Kappe CO. Continuous-flow technology—a tool for the safe manufacturing of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:6688–6728. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snead DR, Jamison TF. A three-minute synthesis and purification of ibuprofen: pushing the limits of continuous-flow processing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:983–987. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lévesque F, Seeberger PH. Continuous-flow synthesis of the anti-malaria drug artemisinin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1706–1709. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsubogo T, Oyamada H, Kobayashi S. Multistep continuous-flow synthesis of (R)- and (S)-rolipram using heterogeneous catalysts. Nature. 2015;520:329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature14343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell MG, Jamison TF. Seven-step continuous flow synthesis of linezolid without intermediate purification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:7678–7681. doi: 10.1002/anie.201901814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma MK, Acharya RB, Shukla CA, Kulkarni AA. Assessing the possibilities of designing a unified multistep continuous flow synthesis platform. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2018;14:1917–1936. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.14.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bana P, et al. The route from problem to solution in multistep continuous flow synthesis of pharmaceutical compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017;25:6180–6189. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baxendale, I. R. et al. A flow process for the multi-step synthesis of the alkaloid natural product oxomaritidine: a new paradigm for molecular assembly. Chem. Commun. 2566–2568 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Ley SV. On being green: can flow chemistry help? Chem. Rec. 2012;12:378–390. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201100041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrifield B. Solid phase synthesis. Science. 1986;232:341–347. doi: 10.1126/science.3961484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillier F, Orain D, Bradley M. Linkers and cleavage strategies in solid-phase organic synthesis and combinatorial chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:2091–2158. doi: 10.1021/cr980040+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmieri A, Ley SV, Polyzos A, Ladlow M, Baxendale IR. Continuous flow based catch and release protocol for the synthesis of α-ketoesters. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2009;5:23. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.5.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baxendale, I. R., Ley, S. V., Smith, C. D. & Tranmer, G. K. A flow reactor process for the synthesis of peptides utilizing immobilized reagents, scavengers and catch and release protocols. Chem. Commun. 4835–4837 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Hopkin MD, Baxendale IR, Ley SV. A flow-based synthesis of imatinib: the API of Gleevec. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:2450–2452. doi: 10.1039/c001550d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolaou KC, et al. Synthesis of epothilones A and B in solid and solution phase. Nature. 1997;387:268–272. doi: 10.1038/387268a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandy JP, et al. Advances in solution- and solid-phase synthesis toward the generation of natural product-like libraries. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1999–2060. doi: 10.1021/cr800188v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plante OJ, Palmacci ER, Seeberger PH. Automated solid-phase synthesis of oligosaccharides. Science. 2001;291:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.1057324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mijalis AJ, et al. A fully automated flow-based approach for accelerated peptide synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:464–466. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Njarðarson Group. Top 200 small molecule pharmaceuticals by retail sales in 2018. The University of Arizonahttps://njardarson.lab.arizona.edu/sites/njardarson.lab.arizona.edu/files/Top%20200%20Small%20Molecule%20Pharmaceuticals%202018V4.pdf (2018).

- 34.Coley CW, et al. A robotic platform for flow synthesis of organic compounds informed by AI planning. Science. 2019;365:eaax1566. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bédard AC, et al. Reconfigurable system for automated optimization of diverse chemical reactions. Science. 2018;361:1220–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.aat0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole KP, et al. Kilogram-scale prexasertib monolactate monohydrate synthesis under continuous-flow CGMP conditions. Science. 2017;356:1144–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.aan0745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farouz, F. S., Holcomb, R. C., Kasar, R. & Myers, S. S. Compounds useful for inhibiting chk1. WO Patent 2010077758 A1 (2010).

- 38.Bagley MC, et al. The effect of RO3201195 and a pyrazolyl ketone P38 MAPK inhibitor library on the proliferation of Werner syndrome cells. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:947–956. doi: 10.1039/C5OB02229K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron H, Remfry FGP, Thorpe JF. The formation and reactions of imino-compounds. Part I. Condensation of ethyl cyanoacetate with its sodium derivative. J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 1904;85:1726–1761. doi: 10.1039/CT9048501726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Munirathinam R, Huskens J, Verboom W. Supported catalysis in continuous-flow microreactors. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015;357:1093–1123. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201401081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schneider G, Fechner U. Computer-based de novo design of drug-like molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:649–663. doi: 10.1038/nrd1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott, P. J. H. Linker Strategies in Solid-Phase Organic Synthesis (John Wiley & Sons, 2009)

- 43.Blaney P, Grigg R, Sridharan V. Traceless solid-phase organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:2607–2624. doi: 10.1021/cr0103827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cankařová N, Schütznerová E, Krchňák V. Traceless solid-phase organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:12089–12207. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanghvi YS. A status update of modified oligonucleotides for chemotherapeutics applications. Curr. Protoc. Nucl. Acid Chem. 2011;46:4.1.1–4.1.22. doi: 10.1002/0471142700.nc0401s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider G. Automating drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:97–113. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figs. 1–64, Tables 1–11, synthetic procedural details, automation development and implementation, high-resolution mass spectrometry, infrared data, NMR data and spectra, HPLC spectra.

Recording of the automated synthesis of prexasertib using the SPS-flow system.

Raw data for the bioactivity evaluation shown in Supplementary Fig. 23.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. A video of the SPS-flow automated synthesis of prexasertib is recorded as Supplementary Video 1.

The LabVIEW code for operating the SPS-flow automated synthesis in this study is available at https://github.com/nus-automated-flow-system/auto-SPS-Flow-Supplementary-Software.