Abstract

Objective:

Developmental models of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) have highlighted the interplay of psychological variables (i.e., impulsivity and emotional reactivity) with social risk factors including invalidating parenting and childhood trauma. Prospective longitudinal studies have demonstrated the association of BPD with social, familial and psychological antecedents. However, to date, few of these studies have studied the interaction of multiple risk domains and their potential manifestations in the preschool period.

Method:

Participants were 170 children enrolled in a prospective longitudinal study of early childhood depression. Participants completed a baseline assessment between ages 3-6 years. Psychopathology, suicidality and self-harm were assessed using a semi-structured age appropriate psychiatric interview before age 8 as well as self-report after age 8. BPD symptoms were assessed between ages 14-19 by self-report. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and peer relations were reported by parents. Maternal support was assessed using an observational measure at ages 3-6.

Results:

Preschool ACEs accounted for 14.9% of adolescent BPD symptom variance in a regression analysis. Controlling for gender and preschool ACEs, preschool and school-age externalizing symptoms, preschool internalizing symptoms and low maternal support were significant predictors of BPD symptoms in multivariate analyses. Preschool and school age suicidality composite scores significantly predicted BPD symptoms.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that preschool factors may be early predictors of BPD symptomatology. Findings demonstrate that preschoolers with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, high ACEs, and early suicidality are at greater risk of developing BPD symptoms. However, further research is needed to guide key factors for targeted early intervention.

Keywords: early childhood, adverse childhood experiences, maternal support, suicidality, preschool onset disorders

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a common and highly impairing diagnosis characterized by instability in affect, impulse control, interpersonal relationships, and self-image1. BPD is associated with severe psychosocial impairment2 and high mortality: up to 10% of patients commit suicide3, a rate almost 50 times higher than the general population4. The severe impairment BPD causes is reflected in its prevalence in clinical settings. While the community prevalence of BPD is 1-2%5, it is present in up to 20% of people in outpatient psychiatric care6, and up to 50% of people receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment7. The personal and social costs of BPD are heavy with high rates of unemployment and increased disability and health services utilization8,9. Although effective psychotherapy based treatments for BPD have been developed10,11, their delivery is resource intensive with limited availability. The diagnosis of BPD prior to adulthood remains controversial, due to the hesitancy of some practitioners to assign a personality disorder diagnosis to individuals still in a period of identity formation12. However, there is growing evidence of general continuity of BPD symptoms from adolescence to adulthood13,14 as well as impairment related to BPD symptoms in adolescence strikingly similar to that experienced by adults14,15.

The morbidity, mortality, and social burden of BPD make prevention, early detection, and intervention urgent public health priorities. However, research on early predictors of BPD has been relatively limited. While there have been some prospective longitudinal studies studying BPD as an outcome16,17,18, few have examined preschool risk factors. In a systematic review, Stepp et. al. found that on average, risk factors were assessed at 13 years old19. Thus, there is need for research on BPD risk factors assessed during early childhood, as treatments focused on parenting and emotion regulation can be highly impactful at this age20,21.

Prominent developmental models of BPD highlight the interaction of psychological variables such as impulsivity,22 emotional sensitivity, and over-reactivity23 with social risk factors including invalidating parenting22, disorganized attachment24,11, and childhood trauma25. These biopsychosocial developmental models have been supported by prospective longitudinal studies demonstrating that BPD is associated with social antecedents such as child abuse and neglect26, maternal hostility16, early life stress27, and peer victimization.18 Psychological antecedents including ADHD symptoms17 and infant emotionality16, and biological antecedents including genetic liability14 and prenatal exposures28 have been reported. Family psychiatric history, 29,30 which includes biological, psychological, and social components is a strong indicator of risk. However, few studies have accounted for multiple risk domains simultaneously, making it difficult to determine if there is a separable role for each of these risk factors in predicting BPD. Moreover, many of these studies are limited to the adolescent time period, leaving the effects of earlier childhood psychopathology, occurring during a key period of emotional regulatory development, unexplored. Finally, while a number of studies use high risk community (e.g. enriched for poverty) and clinical (e.g. enriched for externalizing psychopathology) samples, to our knowledge no study to date has prospectively examined BPD risk factors in a sample selected for internalizing psychopathology ascertained in early childhood, which is also associated with impaired development of emotion regulation.

The goal of the present study was to utilize longitudinal data from a sample enriched for preschool depression to examine the relationships between family, social, and psychological factors prospectively assessed during early childhood on adolescent BPD symptoms. Following key findings on predictors of BPD, we specifically examined the following potential early developmental antecedents of borderline symptoms: (a) demographic predictors, (b) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), (c) maternal support, (d) maternal psychopathology, (e) childhood internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, (f) peer problems and (g) preschool suicidality, which while unusual has been observed in this study group31. We also attempted to determine the separable effects of ACEs, maternal support, and preschool internalizing and externalizing psychopathology through a multiple regression model.

Method

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the Preschool Depression Study (PDS), a prospective, longitudinal investigation of preschoolers and their families conducted at the Washington University School of Medicine Early Emotional Development Program that has been extensively described elsewhere32. Initially 306 3-6 year old children and their caregivers were recruited from primary care clinics and day care centers in the St. Louis Metropolitan area oversampling for depression using the Preschool Feelings Checklist, a validated measure assessing depressive symptoms in the preschool age, enrolling children with ≥ 3 symptoms of depression, ≥ 3 symptoms of disruptive behavior, or those with ≤ 1 symptom of any type. All were invited to participate in up to an additional 6 yearly assessments including clinical interviews, observational assessments, and behavioral questionnaires, and a subset of these children and their parents were invited for an additional 3 assessments including similar interviews and 4 neuroimaging scans, in total spanning over ten years. The present study includes 170 participants who completed the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children (BPFS-C) during assessment 9 (ages 14-19 years). Participants who completed the BPFS-C at assessment 9 were not statistically different from those that did not complete the 9th assessment in demographics or any of the domains of psychopathology and functioning assessed (see Table S1, available online).

Assessments

For a composite summary of all assessments and timing of administration, please see Table S2, available online.

Demographic Assessments

Income-to-Needs ratio was assessed at baseline by dividing parent-reported income by the federal poverty guideline for parent-reported number of people living in the home.

IQ was assessed using either the Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence II at assessment 5 (age 8-12) or the Kauffman Brief Intelligence Test 2 at assessment 7 (ages 9.17-14.89). Due to the presumed general stability across development, this was considered as a lifetime risk factor.

Adolescent Psychopathology and Outcome Assessments

Borderline Symptoms.

Youths’ borderline symptoms were assessed using the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children (BPFS-C)33, a widely used self-report measure of borderline pathology with excellent criterion validity34. The borderline symptoms were assessed at assessment 9, ages 14-19 (mean age=16.0, SD= 0.96). Our analyses used a continuous BPFS-C score as well as the standard BPFS-C cutoff score of 65 for presumptive clinical diagnosis34.

Psychopathology.

Symptoms of depression (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SOC), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) were assessed at assessment 9 using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia PL (KSADS)35, a reliable, semi-structured clinical interview for parents and children ages 6–18. All diagnoses were based on DSM-5 symptoms endorsed by either caregiver or youth.

Impairment.

At assessment 9 (age 14-19, mean 16.0) impairment was assessed by the clinician-rated Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), a widely used, reliable measure of children and adolescents’ general functioning36. The Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ), a reliable and valid parent-report measure of children and adolescent’s overall impairment, academic functioning, peer relationships, and both overt and relational aggression37, was assessed at multiple timepoints.

Assessments of Early Life Experiences and Risk Factors

Maternal Support.

Maternal support was measured at assessment 2, (ages 4.0-7.11 years), through observational coding of “the waiting task”, a laboratory task designed to produce mild stress for both members of the parent-child dyad. The task requires the child to wait 8 minutes before opening a wrapped gift while the parent completes questionnaires. The parent’s supportive caregiving strategies (providing guidance, verbal assists, warmth and affection, emotion coaching, changing proximity, incorporating the child in their work, and clear directions and explanations) were coded by staff trained to reliability. Support score was calculated as the number of supportive events per minute(unpublished data, January, 2006.)

ACEs.

We created an Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) variable based on items identified by Felitti et al38, summing items assessing parent-reported poverty, parental suicide attempts, substance abuse, and psychopathology, and parent- or child-reported traumatic events, then converting to a Z-score, as detailed elsewhere39. ACEs variables include: one including experiences only during the preschool period (3-6 years), one only experiences in the school-age period (7-9 years), and another including lifetime experiences from all assessments in which these were captured (assessments 1-8). See Table S3, available online, for the rates of each ACE during each developmental period. To ensure the robustness of results, two alternative Z-transformed ACE variables were created, one excluding parental psychopathology and one excluding a history of poverty, due to the inclusion of these factors as independent predictors in our analyses.

Assessments of Maternal Psychopathology.

Maternal BPD symptoms were measured using the borderline subscale of the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI-BOR), a widely used self-report measure of borderline pathology with high criterion validity40, during assessment 9. General Maternal Psychopathology was assessed using the Family Interview for Genetic Studies41 and questions about current treatment; mothers comprised 92% of informants. Maternal history of psychopathology (any affective, psychotic, anxiety disorder, or ADHD) and maternal history of depression were calculated as dichotomous variables. They were assessed at assessment 7, when participants were aged 9.17-14.89 years and were assumed to be lifetime risk factors for the child.

Early life Psychopathology.

Symptoms of MDD, GAD, separation (SAD) and social (SOC) anxiety disorders, ADHD, ODD and CD were assessed from the 1st to the 8th assessments using the semi-structured parent-report interview Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA)42 from ages 3-7 years and the parent-report and child-report Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA)43 from age 8 and above. MDD, anxiety (GAD/SAD/SOC), ADHD, and ODD/CD symptom scores are sums of the total number of DSM-IV diagnostic symptoms endorsed by either the caregiver or child during each assessment. These psychopathology variables were collapsed into internalizing (sum of MDD and anxiety (GAD/SAD/SOC) symptoms) and externalizing (sum of ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms) composites. Preschool composites were averages of all assessments completed between ages 3-5.11 years; School-age composites were averages of all assessments between ages 6-9.11 years.

Assessments of Peer Relations.

Peer relations were assessed with the parent-reported Health Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ),37 collected at each assessment. The global peer relationships scale assessed the participants’ relationships with peers during the preschool (age 3-5.11 years) and school-age (age 6-9.11 years) periods. The composite assesses the quality of a child’s friendships, the extent to which the child is liked by peers, and how frequently the child is teased.

The HBQ bullied by peers and relational victimization subscales were used in planned post-hoc analyses.

Suicidality and Self-Injury Composite Variables.

Suicidality composite variables were derived from the PAPA/CAPA during the preschool and school-age periods and from the KSADS at assessment 9. Each composite summed items measuring recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury. The preschool/school-age composites from the PAPA/CAPA also included items measuring death and suicide themes in play; the KSADS composite included items measuring suicidal intention and attempts, similar to Whalen et al., 201531. 56 of the 306 children in the PDS sample (18%) had suicidality/self-injury during the preschool period.

Plan of Analyses

Regressions.

Impact of BPFS on functioning.

Regression analyses were run to evaluate the association between adolescent BPFS-C score and concurrent functional impairment, with follow-up multiple regression analyses controlling for significant predictors (gender, preschool ACEs score, and concurrent MDD) and a separate regression controlling for other psychiatric diagnoses (MDD, anxiety, ADHD, ODD, and CD) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms Predict Impairment Across a Range of Domains

| Measure of Adolescent Functioning | Bivariate Model | Model with covariates: gender, preschool ACES-Z, concurrent MDD diagnosis | Model with covariates: gender, diagnosis MDD, Anxiety, ADHD, CD, ODD | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Stand Est | t | p | pFDR | n | Stand Est | t | p | pFDR | n | Stand Est | t | p | pFDR | |

| Parent CGAS | 169 | −0.37 | −5.16 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 136 | −0.19 | −2.21 | 0.029 | 0.057 | 135 | −0.231 | −2.812 | 0.006 | 0.014 |

| Child CGAS | 170 | −0.52 | −7.85 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 137 | −0.36 | −4.64 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 135 | −0.407 | −5.44 | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| HBQ functional impairment | 169 | 0.30 | 4.12 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 136 | 0.18 | 1.98 | 0.049 | 0.074 | 135 | 0.232 | 2.609 | 0.119 | 0.159 |

| HBQ global peer relations | 169 | −0.19 | −2.53 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 136 | −0.13 | −1.34 | 0.183 | 0.183 | 135 | −0.148 | −1.568 | 0.183 | 0.182 |

| HBQ academic functioning | 169 | −0.27 | −3.68 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 136 | −0.18 | −1.93 | 0.055 | 0.074 | 156 | −0.158 | −2.302 | 0.023 | 0.037 |

| HBQ relational aggression | 169 | 0.31 | 4.20 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 136 | 0.22 | 2.40 | 0.018 | 0.078 | 135 | 0.246 | 2.751 | 0.007 | 0.014 |

| HBQ overt aggression | 168 | 0.30 | 4.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 135 | 0.29 | 3.08 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 135 | 0.261 | 2.978 | 0.003 | 0.012 |

| Child reported suicidality and self-injury | 170 | 0.34 | 4.70 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 137 | 0.11 | 1.45 | 0.150 | 0.171 | 135 | 0.19 | 2.14 | 0.034 | 0.045 |

Note: When controlling for correlated factors (gender, preschool adverse childhood experiences, and concurrent diagnosis of major depressive disorder), BPD symptoms continue to predict global functioning and aggression. When controlling for comorbid psychopathology, BPD symptoms continue to predict global and academic functioning as well as aggression. ACES-Z = Z-transformed adverse childhood experiences; ADHD= attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CD= conduct disorder; CGAS = child global assessment scale; HBQ = health and behavior questionnaire; MDD= major depressive disorder; ODD= oppositional defiant disorder.

Early predictors of BPFS-C score.

Bivariate and multiple regression analyses controlling for gender and preschool ACEs were run to evaluate the association between early life risk factors with adolescent BPFS-C score. To assess if predictors of dimensional borderline symptoms also predicted likely BPD diagnosis (BPFSC>65), we ran logistic regressions, again controlling for gender and preschool ACEs.

Relationship between ACEs and BPD.

As above, we calculated ACEs variables (1) excluding parental psychopathology and (2) excluding poverty, and performed regressions predicting BPD symptoms from these variables. A separate linear regression predicted BPFS-C score excluding the small subset of participants that experienced sexual abuse. We tested whether preschool ACEs score differentially predicted the four BPFS-C subscales with planned regressions of each subscale. Post-hoc analysis of the association between preschool ACEs and age 14-19 depression symptoms evaluated the specificity of the relationship between ACEs score and BPFS-C score. We tested whether there was a significant difference in the variance attributable to ACEs in BPD as opposed to MDD symptoms using the Stieger’s Z.

Correction for Multiple Comparisons.

All p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons, using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure44. All p-values reported below are the false discovery rate corrected p-values and are denoted as pFDR.

Results

BPD is Prevalent in this Sample

Presumptive BPD at age 14-19 years was prevalent in this sample enriched for preschool depression. Of the 170 individuals in our sample, 41 (24.1%) scored > 65 on the BPFS-C, exceeding the suggested cutoff for BPD on the BPFS-C (Table 1).

Table 1:

Rates of Psychiatric Conditions Comorbid with Suprathreshold Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms

| Participants with BPD (n=41) |

Participants without BPD (n=129) |

Participants with vs. without BPD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | % | n | % | n | χ2 | p | pFDR | OR | 95% CI |

| MDD | 39.0 | 16 | 3.9 | 5 | 24.61 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 15.87 | (5.32, 47.31) |

| GAD/SAD/SOC | 48.8 | 20 | 20.9 | 27 | 11.35 | 0.0008 | 0.0011 | 3.60 | (1.71, 7.58) |

| ADHD | 19.5 | 8 | 6.3 | 8 | 5.78 | 0.0162 | 0.0162 | 3.64 | (1.27, 10.43) |

| ODD/CD | 19.5 | 8 | 1.6 | 2 | 11.27 | 0.0008 | 0.0011 | 15.39 | (3.12, 75.95) |

Note: ADHD= attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BPD= borderline personality disorder; CD= conduct disorder; GAD= generalized anxiety disorder; MDD= major depressive disorder; ODD= oppositional defiant disorder; SAD= separation anxiety disorder; SOC= social phobia.

BPD is Associated with Concurrent Psychopathology

Likely diagnosis of BPD, as indicated by BPFS-C > 65, was positively associated with all concurrent psychiatric diagnoses examined. Suprathreshold BPD symptoms were associated with increased risk of concurrent depression (OR= 15.87, 95% CI: 5.32-47.31), anxiety disorders (OR=15.87, 95% CI: 1.71-27.58), ADHD (OR= 3.64, 95% CI: 1.27-10.43) and ODD/CD (OR= 15.39, 95% CI: 3.12-75.95). However, while participants with suprathreshold BPD symptoms had extensive comorbidity, no comorbid diagnosis was present in more than half of participants with presumptive BPD. Of participants with BPFS-C>65, 16 (39%) met criteria for MDD, 20 (49%) met criteria for an anxiety disorder, 8 (20%) for ADHD and 8 (20%) for ODD/CD.

Borderline Personality Symptoms are Associated with Clinical Impairment

Bivariate analyses showed BPFS-C score was significantly associated with each measure of functional impairment (Table 2). Specifically, higher BPFS-C scores were associated with decreased global functioning assessed by CGAS parent (ß=−0.37, pFDR<0.001) and child interview (ß=−0.52, pFDR<0.001) and increased functional impairment assessed by HBQ (ß=0.30, pFDR<0.001). In the domain of peer relations, higher BPFS-C scores corresponded to worse global peer relations (ß=−0.19,pFDR=0.0124), increased relational aggression (ß=0.31, pFDR<0.001) and increased overt aggression (ß=0.30,pFDR<0.001) assessed by HBQ. Higher BPFS-C scores also corresponded to lower academic functioning as assessed by HBQ (ß=−0.27, pFDR<0.001) and increased suicidality/self-injury composite score (ß=0.31, pFDR<0.001).

In the multivariate models controlling for preschool ACEs, gender, and concurrent MDD (see Table 2), all of which were shown to be associated with increased BPFS-C scores in regression analyses, BPFS-C scores were significantly associated with decreased global functioning as assessed by CGAS child interview (ß=−0.36, pFDR<0.001), increased relational aggression (ß= 0.22, pFDR=0.048), and increased overt aggression (ß=0.29, pFDR=0.010). In the multivariate models controlling for gender and comorbid diagnoses, including ever having a diagnosis of MDD, Anxiety (GAD, SOC, PTSD), ADHD, ODD, and CD, BPFS-C scores were significantly associated with decreased global functioning as assessed by CGAS parent (ß=−0.23, pFDR=0.014) and child interview (ß=−0.41, pFDR=0.008), poorer academic functioning (ß=−0.16, pFDR=0.037), increased relational aggression (ß=0.25, pFDR= 0.014), overt aggression (ß=0.26, pFDR= 0.012), and suicidality and self-injury (ß=0.19, pFDR=0.045).

Preschool and School-Age Adversity, Maternal Psychopathology and Problematic Peer Relations Predict BPD Symptoms and Diagnosis

Outside the domain of peer relations, each childhood variable examined was significantly associated with BPD symptoms (Table 3, correlations between variables shown in Table S4, available online). Bivariate analyses demonstrated that BPFS-C scores were associated with female gender (t=2.44, pFDR=0.024), lower IQ (ß=−0.15, pFDR= 0.027) and lower family income-to-need ratio during preschool (ß=−0.21, pFDR=0.024). Preschool (ß=0.38, pFDR<0.001) and school-age (ß=−0.29, pFDR<0.001) ACEs score predicted increased BPFS-C score, as did lower preschool maternal support (ß=−0.20, pFDR=0.027), maternal borderline features (ß=0.26, pFDR=0.001), maternal depression history (ß=0.19, pFDR=0.021), and maternal history of any psychopathology (ß=0.25, pFDR=0.002). However, preschool and school-age peer relations were not significantly associated with BPFS-C score when accounting for multiple comparisons. Planned post-hoc analyses found that childhood bullying victimization and relational victimization were also not significantly associated with BPFS-C score.

Table 3:

Early Life Factors Predict Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in Adolescence in Bivariate and Multivariate Regression Models

| Bivariate Model | Model with covariates: gender, preschool ACES-Z |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | n | Stand. Est. | t | p | pFDR | n | Stand. Est. | t | p | pFDR |

| Female gender | 170 | 0.18 | 2.44 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 137 | 0.15 | 1.87 | 0.063 | 0.190 |

| IQ score | 163 | −0.17 | −2.23 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 130 | −0.05 | −0.54 | 0.590 | 0.590 |

| Baseline income-to-needs ratio | 149 | −0.21 | −2.61 | 0.010 | 0.024 | 126 | −0.09 | −0.99 | 0.324 | 0.481 |

| Early Life Experiences | ||||||||||

| Preschool ACES-Z | 137 | 0.39 | 4.86 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 137 | 0.38 | 4.76 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age 6-8 ACES-Z | 141 | 0.29 | 3.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 132 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.686 | 0.696 |

| Preschool maternal support | 130 | −0.19 | −2.24 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 129 | −0.20 | −2.45 | 0.016 | 0.0236 |

| Maternal Psychopathology | ||||||||||

| Maternal borderline symptoms | 169 | 0.26 | 3.46 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 136 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 0.236 | 0.494 |

| Maternal depression history | 169 | 0.18 | 2.34 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 136 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.998 | 0.998 |

| Maternal psychopathology history | 169 | 0.25 | 3.27 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 136 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.329 | 0.494 |

| Early Psychopathology | ||||||||||

| Preschool internalizing symptoms | 137 | 0.28 | 3.43 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 137 | 0.18 | 2.17 | 0.032 | 0.044 |

| School-age internalizing symptoms | 154 | 0.17 | 2.15 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 135 | 0.10 | 1.19 | 0.235 | 0.235 |

| Preschool externalizing symptoms | 137 | 0.34 | 4.21 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 137 | 0.24 | 2.70 | 0.008 | 0.031 |

| School-age externalizing symptoms | 152 | 0.29 | 3.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 133 | 0.22 | 2.42 | 0.017 | 0.034 |

| Problems with Peers | ||||||||||

| Preschool HBQ peer relations | 135 | −0.18 | −2.07 | 0.040 | 0.080 | 135 | −0.13 | −1.66 | 0.100 | 0.100 |

| School-age HBQ peer relations | 154 | −0.14 | −1.76 | 0.080 | 0.080 | 135 | −0.09 | −1.18 | 0.239 | 0.239 |

| Suicidality | ||||||||||

| Preschool suicidality and self-injury composite | 137 | 0.25 | 2.95 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 137 | 0.19 | 2.21 | 0.029 | 0.058 |

| School-age suicidality and self-injury composite | 154 | 0.17 | 2.16 | 0.033 | 0.033 | 135 | 0.11 | 1.38 | 0.170 | 0.170 |

Note: ACES-Z= Z-transformed adverse childhood experiences ;HBQ = Health and Behavior Questionnaire.

When controlling for gender and preschool ACES, low preschool maternal support continued to predict increased BPFS-C scores (ß=−0.20, pFDR= 0.024). However, IQ, preschool income-to-needs ratio, school-age ACES, maternal BPD symptoms, maternal depression history, and maternal psychopathology history no longer significantly predicted BPFS-C scores.

In assessing whether predictors of BPD symptoms also predicted presumptive BPD diagnoses (BPFS-C>65) we found that female gender, lower IQ, low baseline income-to-needs, and higher preschool and school-age ACEs were all predictive of presumptive BPD, however, in a step-wise multiple logistic regression, preschool ACES was the only significant predictor of presumptive BPD diagnosis when all were included in the model.

Preschool ACEs are a Robust Predictor of BPD Symptoms

When calculated without parental psychopathology (ß=0.31, p<0.001) or poverty (ß=0.37, p<0.001) as a potential ACE, preschool ACEs continued to predict BPFS-C scores. When re-calculated excluding children who experienced sexual abuse, which was done given prior reports of specific associations between sexual abuse and BPD, preschool ACEs also continued to predict BPFS-C scores (preschool ACEs ß=0.36, p<0.001), though adolescents with a lifetime history of sexual abuse had significantly higher BPD symptoms (M=69.43, SD=11.574) than adolescents who had not experienced sexual abuse (M=55.01, SD=13.055; t=3.987, p<0.001).

Post-hoc analysis to determine whether preschool ACEs predicted significantly more variance in any specific BPFS-C subscale than others demonstrated the variance explained for each subscale was statistically equivalent: Self-harm (adj R2=0.097, F=15.669, p<0.001); Relationships (adj R2=0.143, F=23.668, p<0.001); Identity problems (adj R2=0.125, F=20.396, p<0.001); Affect instability (adj R2=0.042, F=7.010, p=0.009), all Steiger’s Z < 1.5 andps > 0.10.

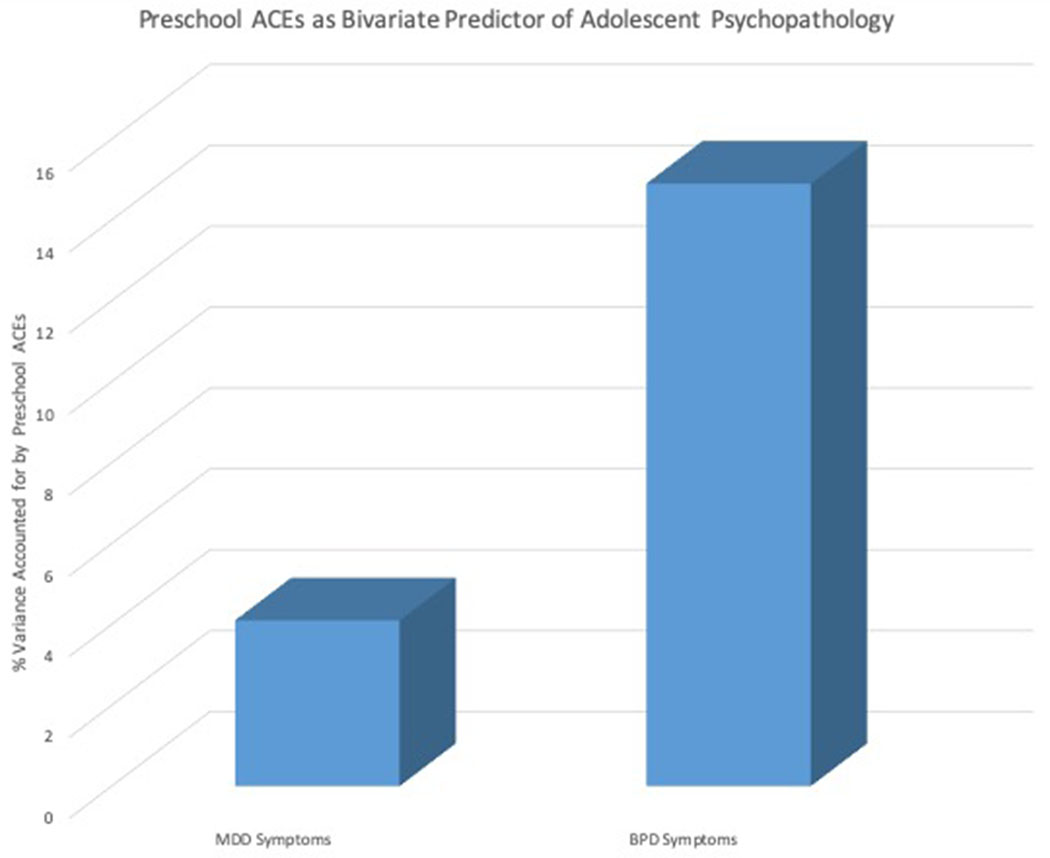

Preschool ACEs predicted BPD symptoms above and beyond broad internalizing or externalizing symptoms. When predicting later BPD symptoms, the relationship between preschool ACEs remained significant (ß=0.23, p=0.006) when gender, concurrent internalizing and externalizing symptoms were entered into the model, though concurrent externalizing symptoms also related to BPD symptoms (ß=0.34, p<0.001). While preschool ACEs are also known to predict adolescent depression, the relationship between preschool ACEs and adolescent BPD symptoms was numerically stronger than the relationship between preschool ACEs and adolescent depression, though not statistically significantly so (Figure 1). A post-hoc bivariate analysis found that preschool ACEs predicted 14.9% of the variance in BPFS-C score (ß=0.38, p<0.001, R2=0.149), versus only 4.1% of the variance in MDD symptoms, despite being a significant predictor (ß=0.202, p=0.018, R2=0.041). However, there is no significant difference in the variance explained using the Steiger’s Z (Z=−1.618, p=0.10).

Figure 1:

Preschool Adverse Childhood Experience as a Predictor of Borderline Personality Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder Symptoms

Note: ACEs= adverse childhood experiences; BPD= borderline personality disorder; MDD= major depressive disorder.

Preschool and School-Age Psychopathology Predict BPD Symptoms and Diagnosis

In bivariate analyses, both childhood internalizing and externalizing symptoms were associated with increased adolescent BPD symptoms. Preschool and school-age internalizing (PS: ß= 0.28, pFDR=0.001; SA: ß=0.17, pFDR=0.033) and externalizing (PS: ß=0.34, pFDR<0.001; SA: ß=0.29, pFDR<0.001) symptoms were significant predictors of increased BPFS-C score. When controlling for gender and preschool ACEs, the relationship remained significant for preschool and school-age externalizing symptoms (PS: ß=0.22, pFDR=0.031, SA: ß=0.24, pFDR=0.034) and preschool internalizing symptoms (ß=0.18, pFDR=0.044.

Logistic regressions found that none of the childhood psychopathology variables was significantly associated with suprathreshold BPD scores.

Preschool and School-Age Suicidality Predict BPD Symptoms

Bivariate analyses demonstrated that preschool (ß=0.25, pFDR=0.007) and school-age (ß=0.17, pFDR=0.033) suicidality/self-injury composites significantly predicted increased BPFS-C score, though neither variable significantly predicted BPFS-C score when controlling for gender and preschool ACEs.

Preschool Risk Factors Explain Variance in Adolescent BPD Symptoms

A multiple regression model including all significant preschool predictors (preschool ACEs score, gender, preschool externalizing symptoms, preschool internalizing symptoms and preschool maternal support) was conducted (see Table 4). In this model, preschool ACES (ß=0.24, p=0.011), female gender (ß=0.019, p=0.022), and low maternal support (ß=−0.17, p=0.038) predicted adolescent borderline symptoms. The overall model accounted for over 20% of the variance in adolescent borderline symptoms (adjusted R2= 0.216).

Table 4:

Multivariate Model Including Significant Preschool Age Predictors of Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms

| Independent Variable | Standardized Estimate | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preschool ACES-Z | 0.24 | 2.56 | 0.012 |

| Female gender | 0.19 | 2.32 | 0.022 |

| Preschool externalizing symptoms | 0.18 | 1.71 | 0.090 |

| Preschool internalizing symptoms | 0.09 | 0.91 | 0.365 |

| Preschool maternal support | −0.17 | −2.10 | 0.038 |

Note: A multivariate model including preschool ACEs, psychopathology, and low observed maternal support explains over 20% of the variance in BPD symptoms in adolescence, with independent contributions for ACEs and low observed maternal support. ACES-Z = Z-transformed adverse childhood experiences.

Discussion

This study examined relationships between early childhood family, social and psychological factors and adolescent BPD symptoms using longitudinal data. Interestingly, we found more adolescents ages 14-19 with presumed BPD than with MDD. As expected, BPD symptoms were associated with increased risk of concurrent psychopathology as well as overall impairment. Bivariate analyses emphasized the role of stressful early life experiences in BPD symptomatology, as preschool ACEs strongly predicted borderline symptoms, accounting for 14.9% of variance. Multivariate analyses controlling for gender and preschool ACEs revealed additional roles for maternal support and early psychopathology in development of BPD symptoms, as low preschool maternal support, preschool internalizing psychopathology and preschool and school-age externalizing psychopathology were also robust predictors of BPD symptoms. Analyses showed that preschool and school-age suicidal thoughts and behaviors also predicted adolescent borderline symptoms more than 10 years later. Interestingly, while bivariate analyses replicated past research demonstrating that female gender, low IQ, childhood poverty and maternal psychopathology predicted increased borderline symptoms, these associations were not significant after controlling for gender and ACEs, underscoring the importance of early childhood trauma in BPD symptomatology.

Unexpectedly, the rates of presumed BPD were quite high in this sample of children initially enriched for preschool-onset depression. While those with presumed BPD were more likely to have a co-occurring depression or anxiety diagnosis, less than half of the adolescents with presumed BPD concurrently met criteria for MDD or an anxiety disorder and thus high levels of BPD symptoms presented even in the absence of co-morbid illness. Moreover, our analyses showed that adolescent borderline symptoms as assessed by the BPFS-C were associated with substantial impairment over and above the contribution of the clinical diagnosis of MDD, anxiety, ADHD, ODD, or CD.

Additionally, multiple regression analyses demonstrated internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in preschool predicted adolescent borderline symptoms, even after controlling for gender and ACEs. These results are consistent with the biopsychosocial model of BPD and add to the small number of studies specifically using psychopathology variables as borderline predictors45. However, it is not clear if the risk of later BPD symptomatology is conferred by having a given diagnosis or by dimensional components of these diagnoses such as affective lability, impulsivity22, or difficulty with emotion regulation. Future research should examine whether such dimensional constructs underlie the relationship between early psychopathology and adolescent BPD.

In keeping with the biopsychosocial model of BPD22 bivariate and multiple regression analyses found that preschool adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) were the strongest predictor of adolescent borderline symptoms in our sample, accounting for almost 15% of the variance in bivariate analyses. This result is consistent with substantial literature showing early life stress and adversity, including stressful life events16, lower SES27 and family adversity46 prospectively predict borderline symptoms. However, the significant portion of variance in BPD symptoms predicted by preschool ACEs over a decade later suggests that early life stress may be a particularly strong predictor of borderline symptoms. Further, that preschool but not school-age ACEs were significant in multiple regression models combining both variables suggests early childhood may be a particularly sensitive period for the impact of ACEs on the development of borderline personality features. This finding warrants further study, given there have been no other studies to our knowledge prospectively investigating such early associations, though it provides an important opportunity for preventative interventions.

While bivariate analyses replicated previous results showing that lower IQ30, low childhood SES27 and parental psychopathology47 are prospectively associated with BPD symptoms, none of these factors remained a significant predictor of BPD symptoms after controlling for gender and preschool ACEs. The lack of association of baseline income-to-needs ratio, maternal BPD symptoms, and psychopathology history with adolescent BPD symptoms after controlling for gender and preschool ACEs might be expected given that our ACEs construct includes items measuring parental psychopathology and concurrent poverty. Though, we demonstrate ACEs continue to predict later BPD symptoms even when ACE scores were calculated excluding either parental psychopathology or poverty.

Our bivariate and multiple regression analyses demonstrated that low preschool maternal support was a robust predictor of adolescent BPD symptoms. While not a novel result, this adds to the few studies16,48 that have shown that maladaptive parenting observationally assessed during early childhood is prospectively associated with BPD symptoms. Unfortunately, our parenting data did not allow us to test specific caregiving behaviors such as invalidation23, that contribute to BPD risk in developmental models, though this is an important future direction given the potential role for parenting-based interventions in early BPD treatment and prevention.

Preschool and school-age peer relations were not significant predictors of BPD symptoms. In particular, we failed to replicate the finding of Wolke et. al.18 that school age bullying victimization and relation victimization prospectively predict borderline symptoms. This discrepancy may be due to school-age bullying being measured less proximally to BPD symptoms in this study than in Wolke et al. (at least 5 years vs. 2-4 years.)

In a novel analysis, we found that preschool and school-age suicidality/self-harm were significant predictors of BPD symptoms. This result builds upon the research of Whalen et. al. 201531, showing that that early childhood suicidal cognitions and behaviors (SI) were a robust predictor of school-age SI. The current results suggest that for some patients with BPD, self-harm and suicidal thoughts and behaviors may precede or be some of the earliest indicators of their BPD symptoms and may begin as early as the preschool period. Further research should investigate whether early suicidality/self-harm specifically predicts BPD symptoms in the domain of self-harm, or also predicts other BPD symptom domains (e.g. identity problems.) Further research should also assess the specificity of early suicidality as a predictor of BPD versus other forms of psychopathology.

This study was limited by its sample size, which did not provide sufficient power to investigate the interaction of risk factors in mediating and moderating analyses. Additionally, the enrichment for preschool depression, while enhancing the clinical relevance of this study, may make its results less applicable to the general population. BPD symptoms were measured in adolescence, possibly limiting inferences to adult BPD. However, there is a growing consensus8,12 that BPD is as reliable a diagnosis in adolescence as adulthood. Nonetheless, future research should assess the effect of these early childhood predictors on adult BPD as well. Due to low base rates of trauma outside of poverty and maternal psychopathology, we were unable to isolate specific components of the ACES variable to predict BPD. Mothers were used as primary informants during the preschool years and therefore, some of the information collected may be prone to social desirability and related biases. Future work should capitalize on the strengths of a multi-informant approach.

Overall, the findings presented here have considerable implications for BPD prevention and early intervention. The overall prevalence of adolescent BPD (24%) in this preschool depression enriched cohort suggests that children with early affective psychopathology may be at high risk of developing BPD symptoms. Preschool variables explained a large amount of the variance in adolescent borderline symptoms; the model including gender, preschool ACES, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology accounted for more than 20% of variance. These results suggest that preschoolers with psychopathology, ACEs, and suicidal thoughts/behavior are at high risk of borderline symptoms and should be targeted for further evaluation and intervention. Children with early psychopathology and stressful experiences, particularly those with early suicidality and low maternal support could receive targeted interventions aimed at developing emotion regulation skills, such as Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Children49 or Parent Child Interaction Therapy Emotional Development21, hopefully limiting the extensive morbidity and mortality associated with BPD. Further research investigating the role of various aspects of emotional competence in the pathways from early BPD risk factors to BPD development could result in the discovery of more specific clinical markers and new targets for early intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

All phases of this study were supported by an NIH grant, R01 MH064769-06A1 (PI’s: Luby and Barch). Dr. Vogel’s work was supported by NIH grant T32 MH100019-06. Dr. Whalen’s work was supported by NIH grants: K23MH22325028202-01 (PI: Whalen); L30 MH108015 (PI: Whalen). Mr. Geselowitz’s work was supported by NIH grant 5 T 35 HL 7815-24. We wish to thank the children and caregivers for their continued participation in the Preschool Depression Study.

References

- 1.Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet. 2004;364(9432):453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skodol AE, Pagano ME, Bender DS, et al. Stability of functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive–compulsive personality disorder over two years. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(3):443–451. doi: 10.1017/S003329170400354X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pompili M, Girardi P, Ruberto A, Tatarelli R. Suicide in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;59(5):319–324. doi: 10.1080/08039480500320025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bell CC. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. JAMA. 1994;272(10):828–829. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520100096046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The Prevalence of Personality Disorders in a Community Sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korzekwa MI, Dell PF, Links PS, Thabane L, Webb SP. Estimating the prevalence of borderline personality disorder in psychiatric outpatients using a two-phase procedure. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49(4):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Quinlan DM, Walker ML, Greenfeld D, Edell WS. Frequency of Personality Disorders in Two Age Cohorts of Psychiatric Inpatients. AJP. 1998; 155(1): 140–142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chanen AM, McCutcheon L. Prevention and early intervention for borderline personality disorder: current status and recent evidence. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202(s54):s24–s29. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Asselt ADI, Dirksen CD, Arntz A, Severens JL. The cost of borderline personality disorder: societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. European Psychiatry. 2007;22(6):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-Year Randomized Controlled Trial and Follow-up of Dialectical Behavior Therapy vs Therapy by Experts for Suicidal Behaviors and Borderline Personality Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fonagy P, Bateman A. The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder—A Mentalizing Model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(1):4–21. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp C, Fonagy P. Practitioner Review: Borderline personality disorder in adolescence--recent conceptualization, intervention, and implications for clinical practice. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(12):1266–1288. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bornovalova MA, Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Stability, Change, and Heritability of Borderline Personality Disorder Traits from Adolescence to Adulthood: A Longitudinal Twin Study. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21(4):1335–1353. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wertz J, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Borderline Symptoms at Age 12 Signal Risk for Poor Outcomes During the Transition to Adulthood: Findings From a Genetically Sensitive Longitudinal Cohort Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Published online July 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chanen AM, Jovev M, Jackson HJ. Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(2):297–306. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n0217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson EA, Egeland B, Sroufe LA. A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(4): 1311–1334. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stepp SD, Burke JD, Hipwell AE, Loeber R. Trajectories of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder Symptoms as Precursors of Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in Adolescent Girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(1):7–20. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9530-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolke D, Schreier A, Zanarini MC, Winsper C. Bullied by peers in childhood and borderline personality symptoms at 11 years of age: A prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(8):846–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stepp SD, Lazarus SA, Byrd AL. A systematic review of risk factors prospectively associated with borderline personality disorder: Taking stock and moving forward. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2016;7(4):316–323. doi: 10.1037/per0000186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents With Disruptive Behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(1):215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luby JL, Barch DM, Whalen D, Tillman R, Freedland KE. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Parent-Child Psychotherapy Targeting Emotion Development for Early Childhood Depression. AJP. 2018;175(11): 1102–1110. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(3):495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linehan MM. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Guilford Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunderson JG, Lyons-Ruth K. BPD’s Interpersonal Hypersensitivity Phenotype: A Gene-Environment-Developmental Model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(1):22–41. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Pathways to the Development of Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997; 11(1):93–104. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP. Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk for Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen P, Chen H, Gordon K, Johnson J, Brook J, Kasen S. Socioeconomic background and the developmental course of schizotypal and borderline personality disorder symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(2):633–650. doi: 10.1017/S095457940800031X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winsper C, Wolke D, Lereya T. Prospective associations between prenatal adversities and borderline personality disorder at 11–12 years. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(5):1025–1037. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinelt E, Stopsack M, Aldinger M, Ulrich I, Grabe HJ, Barnow S. Longitudinal Transmission Pathways of Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms: From Mother to Child? PSP. 2014;47(1): 10–16. doi: 10.1159/000345857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belsky DW, Caspi A, Arseneault L, et al. Etiological features of borderline personality related characteristics in a birth cohort of 12-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(1):251–265. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whalen DJ, Dixon-Gordon K, Belden AC, Barch D, Luby JL. Correlates and Consequences of Suicidal Cognitions and Behaviors in Children Ages 3 to 7 Years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(11):926–937.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2015.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luby JL, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, April LM, Belden AC. Trajectories of Preschool Disorders to Full DSM Depression at School Age and Early Adolescence: Continuity of Preschool Depression. AJP. 2014;171(7):768–776. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crick NR, Murray–Close D, Woods K. Borderline personality features in childhood: A short-term longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(4):1051–1070. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang B, Sharp C, Ha C. The Criterion Validity of the Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children in an Adolescent Inpatient Setting. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25(4):492–503. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(11):1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. The Confluence of Mental, Physical, Social, and Academic Difficulties in Middle Childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):588–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barch DM, Belden AC, Tillman R, Whalen D, Luby JL. Early Childhood Adverse Experiences, Inferior Frontal Gyrus Connectivity, and the Trajectory of Externalizing Psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;57(3):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein MB, Pinsker-aspen JH, Hilsenroth MJ. Borderline Pathology and the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI): An Evaluation of Criterion and Concurrent Validity. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;88(1):81–89. doi: 10.1080/00223890709336838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maxwell E The Family Interview for Genetic Studies: Manual. Clinical Neurogenetics Branch, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egger HL, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Potts E, Walter BK, Angold A. Test-Retest Reliability of the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment (PAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(5):538–549. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000205705.71194.b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological). 1995;57(1):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burke JD, Stepp SD. Adolescent Disruptive Behavior and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in Young Adult Men. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9558-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winsper C, Zanarini M, Wolke D. Prospective study of family adversity and maladaptive parenting in childhood and borderline personality disorder symptoms in a non-clinical population at 11 years. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(11):2405–2420. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stepp SD, Olino TM, Klein DN, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Unique influences of adolescent antecedents on adult borderline personality disorder features. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2013;4(3):223–229. doi: 10.1037/per0000015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyons-Ruth K, Bureau J-F, Holmes B, Easterbrooks A, Brooks NH. Borderline symptoms and suicidality/self-injury in late adolescence: Prospectively observed relationship correlates in infancy and childhood. Psychiatry Research. 2013;206(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perepletchikova F, Nathanson D, Axelrod SR, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Preadolescent Children With Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Feasibility and Outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):832–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.