Abstract

Multiregional communication is important to understanding the brain mechanisms supporting complex behaviors. Work in animals and human subjects shows that multiregional communication plays significant roles in cognitive function and is associated with neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders of brain function. Recent experimental advances enable empirical tests of the mechanisms of multiregional communication. Recent mechanistic insights into brain network function also suggest new therapies to treat disordered brain networks. Here, we discuss how to use the concept of communication channel modulation can help define and constrain what we mean by multiregional communication. We discuss behavioral and neurophysiological evidence for multiregional channels modulation. We then consider the role of causal manipulations and their implications for developing novel therapies based on multiregional communication.

Introduction

Multiregional communication occurs when the activity of a population of neurons in one brain region, the sender, sends action potentials that alter the activity of a population of neurons in another brain region, the receiver. Understanding how populations of neurons interact to support flexible behavior is of central importance to systems neuroscience. Figure 1a illustrates the elements of multiregional communication. Projection neurons in the sender population innervate a population of neurons in the receiver population to form a communication channel (Figure 1a) [1]. Taking a feed-forward perspective, changes in activity in the sender region may alter the information that is transmitted to the receiver. However, neurons in the receiver may also vary in their excitability, and hence their responses to input. Changes receiver excitability can therefore alter the response to sender input and may also reflect the action of a channel modulator. Channel modulators may modulate receiver neurons at the soma, perhaps independently of specific input from the sender. Channel modulators may also modulate sender-specific synaptic input to the receiver at pre- or post-synaptic sites (Figure 1b). In each case, the channel modulator effectively controls the state of the communication channel, open or closed, to alter how receiver populations respond to the activity of sender populations. Channel modulators may arise from the neuromodulatory brainstem projection systems [2] as well as due to activity-dependent brain mechanisms that alter functional interactions between regions, such as in the thalamus [3]. The channel modulation hypothesis is falsifiable in cases when communication is not dynamic and is static, and in cases where modulation acts to alter activity at the sender in a feed-forward manner. Modulation of multiregional communication allows responses to vary in a behaviorally-relevant manner. For example, responding to sensory cues depends on how sensory information is dynamically routed between brain regions. When responding to a cue in the presence of distractors, the channel that carries cue information to the motor system could open and the channel carrying distractor information could close (Figure 1c).

Figure 1 –

(a) The communication channel is formed from anatomical projections from a sender (blue) to a receiver (red). As a result, activity in a population of sender neurons drives responses in receiver neurons (right). Note that due to local recurrence, not all neurons in the sender region need to innervate all neurons in the receiver region. The modulator network (black) contains neurons which send anatomical projections to the sender and/or receiver regions. Modulator network activity can alter the receiver response to input from the sender, and so modulate the communication channel. Note also that neurons in a given region of the modulator network need not project to the sender-receiver regions in the communication channel. (b) The modulator network may alter the receiver response due to an influence on the sender alone, (sender-dependent modulation) or due to an influence on the receiver (receiver-dependent modulation). (c) Channel modulation can support flexible behavior by opening the channel that communicates visual target information to guide a behavioral response (Behavior A) while closing the channel supporting communication between a distractor (S2) that would guide a different response (Behavior B).

The channel modulation hypothesis suggests multiple mechanisms by which different behavioral outcomes can arise from modulation of multiregional communication between a sender and receiver population. In the following, we develop and review evidence for the channel modulation hypothesis based on experiments featuring behavioral manipulations, neuronal recordings and causal manipulations.

Multiregional communication to support behavior

Dual-task behavioral designs, widely used in studies of attention and executive control in humans [4,5], require subjects to perform tasks that depend on two concurrent behavioral processes with distinct goals [6]. Since dual-task paradigms involve defining how and when behavioral processes interact, such paradigms constrain potential mechanisms of communication and identify how modulation of multiregional communication supports behavioral flexibility. By using behavior to determine when and how systems interact, dual-task paradigms offer the opportunity to constrain how we interpret patterns of neural firing in terms of communication. Dual-task paradigms also allow fluctuations in behavioral performance to be interpreted as due to the dynamics of multiregional communication. Both overt behaviors, such as movements, and covert behaviors, such as attention and decision-making, depend on systems of brain areas that modulate their interactions depending on behavioral demands. We can interpret behavioral performance as due to modulation of multiregional communication by conceptualizing how information must flow between systems to support the behavior.

Coordinated eye-hand behaviors have been studied as dual-task paradigms. Making a coordinated look and reach depends on interactions between the two systems: the skeletal and oculomotor systems (Figure 2a). Modulations in the interactions between these systems change how the movements are coordinated [7,8]. Furthermore, since task manipulations that require more coordinated behavior increase interactions between the two systems [9], we can design behavioral experiments where behavioral performance can measure the level and potentially the direction of multiregional communication. For example, when arm and eye movements are coordinated the reaction times of each movement are correlated (Figure 2b). Introducing a stimulus-onset asynchrony (SOA) commonly used in dual-task paradigms allows us to experimentally manipulate the onset of movement times - the saccade is instructed by one cue and the reach is instructed by a second cue that follows in time (Figure 2c). As the SOA increases, reaction time correlations decrease (Figure 2d). Modeling work suggests that this is consistent with a breakdown in communication between two systems, with one system guiding saccade reaction times and another system guiding reach reaction times [8]. Introducing the SOA as in a dual-task paradigm can, therefore, change when the reach and saccade systems are recruited, and permits the interpretation of changes in RT correlations as due to changes in communication between the reach and saccade systems.

Figure 2 –

Behavioral systems for multiregional communication. (a) Reach and saccade systems (including the posterior parietal cortex, PPC) work together to guide coordinated movements and independently to guide eye and hand movements. (b) Reaction times for the reach and saccade are correlated for coordinated movements. (c) Dual-task experimental designs can probe the mechanisms of communication across reach and saccade systems by manipulating the stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) for the go cues for the reach and saccade. (d) Reaction time correlations for the reach and saccade decrease with increasing SOA demonstrating dual-task effects. Adapted from ref [8]. (e) Attention systems including the prefrontal cortex (PFC) can provide top-down modulation to sensory systems such as the visual via the visual thalamus (lateral geniculate nucleus, LGN) which increases its output gain to the visual cortex (primary visual cortex, V1). (f) Rodents can be trained to perform a form of dual-task paradigm by attending to either a visual or auditory cue. (g) Performance in the visual detection task decreased in cross-modal conditions (where auditory and visual cues compete for attention) compared to visual-cue only trials. Adapted from [10].

Physiological evidence for multiregional communication also comes from simultaneous recordings from the reach and saccade systems that view coordinated and independent movements as a dual-task paradigm. Beta-frequency-band local field potential (LFP) power in both saccade and reach systems correlates with the reaction time of coordinated reaches and saccades [7]. However, beta-band LFP power is also suppressed during coordinated look-reach movements compared to making eye movements alone [7,11]. Neurons whose firing rates are suppressed during coordinated movements have coherent firing rates with the beta-band LFP [11]. Such inhibition may serve as a brake to help coordinate the two movements. These results suggest that both neural inhibition of firing rates and LFP power and functional inhibition of behavioral latencies can be features of communication channel modulation. However, both the coordinated movement task and the SOA task fall short of definitively linking neural mechanisms to the multiregional communication between saccade and reach systems. Reaction times for coordinated movements may be guided by mechanisms outside of these circuits [12] and further work is needed to assess such contributions.

Attention and decision-making tasks are also fertile terrain for dual-task designs and provide opportunities to test how modulation of multiregional communication guides behavior. Sensory attention is controlled by multiple systems that can generate endogenous goals or can be captured by exogenous stimuli [13]. Stimulus-driven attention, driven by salient external stimuli, is often described as being ‘bottom-up’, as it propagates from sensory systems to the association systems. Dual-task experimental designs to pit bottom-up and top-down requirements can be used to reveal interactions between these processes [13]. Dual task designs to investigate multiregional communication can also employ competing sensory stimuli from different sensory systems. Prefrontal cortex is essential for gating attention between sensory signals from either visual or auditory systems (Figure 2e), depending on task demands (Figure 2f) [10,14]. The gating of attention reflects a form of inhibitory communication that affects behavioral performance (Figure 2g), and is mediated between the thalamus and frontal-parietal cortex [10,14].

For visual attention, salience is encoded as early as the primary visual cortex [15] but is also dependent on the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) [16]. Goal-directed visual attention or ‘top-down’ attention is guided by behavioral motivation. While in primates top-down visual attention is believed to be mediated by frontal parietal systems [17], frontal-parietal activity modulates visual system processing as well [18]. Top-down and bottom-up systems for visual attention compete to guide behavior [13,19,20]. Decision-making may be goal-directed, or ‘model based,’ meaning actions are motivated by their specific consequences, or decisions may arise out of habit, or ‘model-free’, and are not reliant on the potentially changing circumstances under which the action is undertaken [21]. Interactions between different decision systems may also depend on multiregional communication [22].

In each case, dual-task designs permit behavioral performance to be interpreted in terms of communication between brain systems which serves to constrain interpretations of the underlying patterns of neural activity. When behavioral evidence indicates that channel-based communication is changing, patterns of neural activity that are hypothesized to support channel communication must also change. If the changes in receiver activity can be attributed to activity changes driving the sender, the changes in communication may reflect a feed-forward pathway. If the changes in the receiver response are not explained by changes in the sender activity alone, the changes in communication may reflect channel modulation.

Neural mechanisms of flexible communication

Multiregional communication is typically inferred from correlations in neural activity [23]. In electrophysiology, a pervasive feature of correlated neural activity is neural coherence between spiking activity and LFP activity [24]. Studies of visual-spatial attention report that patterns of coherent activity between a sender and a receiver region depend on the current locus of attention [25]. Neural coherence may, therefore, be responsible for flexibly routing information through cortical networks [26]. Coherent neural activity is also recruited in different frequency bands, notably alpha, beta and gamma bands. Frequency-specific correlations have been interpreted as reflecting distinct communication channels supporting top-down versus bottom-up tasks [27]. While some patterns of coherent neural activity in the gamma-frequency band are thought to reflect feedforward drive, coherent neural activity across a range of frequencies may also reflect changes in neural excitability that modulate receiver responses to sender input.

While the role that coherent neural activity plays in sender-receiver-modulator interactions remains open, this body of work highlights how the neural mechanisms which support flexible communication depend, at least in part, on synchrony and neural coherence. Formulating the analysis of multiregional communication in terms of channel modulation will help interpret the results in terms of sender-receiver-modulator interactions. Previous work has also inferred communication from correlations in neuronal activity as well as from field potentials. Both inferences may suffer interpretational challenges due to confounds such as common input or volume conduction [28]. Studying the effects of behavioral and causal manipulations in terms of sender-specific and receiver-specific modulations is important to address these interpretational confounds.

In a sender-specific communication, changes in activity at the receiver can be explained by changes in activity in the sender that drives input to the receiver. Evidence for this can be found in a recent study which examined the sender communication hypothesis in the non-human primate early visual system. Fluctuations in a small number of dimensions of the V1 population activity drove changes in V2 activity (Figure 3a) [29]. This suggests that multiregional communication depends on how sender activity occupies a local activity subspace. Other work in rodents also provides evidence of sender subspace communication. Bilateral optogenetic inhibition of a motor cortical area (ALM) transiently silences motor responding. If ALM is transiently inhibited unilaterally, after inhibition is removed, preparatory motor activity is communicated from the other hemisphere and activity in the previously-silenced hemisphere returns to its unperturbed state. Consistent with sender-subspace communication, recovery is primarily in dimensions of neural activity and depends on inter-hemispheric projections linking the sender ALM to the receiver ALM [31]. Perturbations can also reveal sender-specific communication mechanisms. Silencing sender activity can alter the stimulus-dependent response at the receiver, and decrease task performance [32]. Optogenetic activation can also enhance stimulus encoding at the downstream receiver site [33]. In each case, receiver responses are interpreted as being due to silencing or activating the sender consistent with the feedforward operation of a communication channel.

Figure 3 –

Evidence for network mechanisms of communication. (a) Model of sender-dependent modulation of communication in which the response at the receiver depends on the dynamics of activity at the sender. S denotes the Sender. R denotes the Receiver. M denotes the Modulator. (b), Example V2 neuron in which only two dimensions of V1 activity are needed to match the performance of the full model in predicting V2 response. Adapted from [29]. (c) Model of receiver-dependent modulation of communication in which the response at the receiver depends on the dynamics of the activity at the receiver prior to the arrival of inputs from the sender. S,R and M as in a). (d) Response to visual stimulation in V1 depends on the phase of the prestimulus delta band activity. Adapted from [30].

Communication can also be receiver-dependent in ways that are not necessarily due to changes in sender activity and reflect channel modulation. For example, perceptual stimuli are sampled rhythmically [34] and the detection of such stimuli is predicted by the phase of ongoing electroencephalographic (EEG) oscillatory activity [35]. Therefore, neural responses may be gated by sub-second excitability fluctuations. Receiver-dependent modulation has also been reported as a mechanism of gating during decision making [36]. Dynamic changes in excitability are likely governed by a variety of network mechanisms including channel modulators. For example, activity in modulatory brain areas can generate sub-threshold synaptic inputs at the receiver which drive changes in intracellular membrane potentials at the receiver, thus affecting the efficacy of identical inputs arriving from the sender. Consistent with this idea, spiking responses to visual stimulus vary depending on the phase of the population activity at the time of stimulus (Figure 3c) [30]. In each of these cases, receiver responses can be interpreted as governed by fluctuations in receiver excitability. Variations in excitability that can lead to different responses in the receiver even when activity in the sender is the same are an important signature of channel modulation.

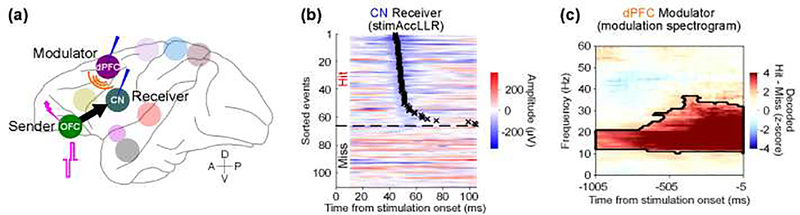

Causal manipulations also provide ways to more precisely identify sender-receiver communication channels and the mechanisms of channel modulation. Recent work has used simultaneous stimulation and recording across the large-scale primate mood processing network to test the channel modulation hypothesis using a causal network analysis [37]. The causal network analysis characterizes sender-receiver communication by measuring neural activity at the receiver(s) in response to isolated microstimulation pulses delivered at the sender (Figure 4a). The probability that the receiver responded to stimulation of the sender was less than one, suggesting a mechanism of network excitability that regulates the state of communication channel between the sender and receiver nodes. Most importantly, the variability in sender-receiver excitability (Figure 4b) could be predicted by decoding modulator neural activity in the beta band (10–40 Hz) immediately prior to sender stimulation (Figure 4c).

Figure 4 –

Modulator decoding for sender-receiver communication. (a) Schematic of predicting the channel state of communication from an orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) sender to a caudate nucleus (CN) receiver based on the neural activity recorded from a dorsal prefrontal cortex (dPFC) modulator. Anterior (A), posterior (P), dorsal (D), and ventral (V) directions are shown. (b) The pulse-by-pulse evoked CN receiver neural activity, in response to single microstimulation pulses (30 μA, 100 μs/phase) delivered at the OFC sender, are sorted by pulse-response latency (black crosses, “Hit”) using the stimulation-based accumulating log-likelihood ratio (stimAccLLR) method. Along with 60% “Hit” events, “Miss” events also observed. (c) Modulation spectrograms of dPFC modulator baseline LFP activity, computed as Z score magnitude of power difference between decoded “Hit” and “Miss” events in CN receiver responses. Contour shows significance from the permutation test (cluster-corrected; n = 10,000, p < 0.05, two-tailed test). Adapted from [37]

Taken together, these results provide valuable tests of channel modulation and how it depends on sender-receiver interactions, and suggest that dynamic multiregional communication is governed by state-dependent fluctuations in neuronal excitability. Note however, that the effects of causal manipulations can be difficult to interpret because of the artificial patterns of activity they generate. Any artificial form of stimulation tends to activate neurons simultaneously and interferes with ongoing dynamics [38]. Electrical microstimulation also tends to activate axons and so generates action potentials that travel in both directions from the site of stimulation to the post-synaptic cell, as well as back to the soma [39]. In these cases, restricting effects to the sender or receiver alone may not be possible. We also note that we have discussed channel modulators that are identified based on patterns of neural activity that correlate with receiver responses to sender manipulations. The presence of correlations between channel modulator activity and sender-receiver interactions does not imply that channel modulators play a causal role in modulating channel communication. Causal inferences to identify channel modulators will be an important area for future work.

Therapeutic implications

Causal analyses of multiregional communication also offer new directions for developing neurotechnologies and closed-loop brain-machine interface (BMI) systems. BMI systems restore lost sensory and motor functions [40–43] by interfacing with particular brain regions. Sensory prostheses write information by stimulating sensory areas. Motor prostheses read out information by recording from motor areas. Integrated brain functions, however, are regulated by communication across multiple brain regions in distributed networks [44,45]. Moreover, manipulating specific brain regions has not yet been effective and efficacious as a treatment strategy, in particular for treating cognitive and mood disorders [46,47]. This may reflect the need to model state-dependent multiregional communication. To address these concerns, the concept of modulator decoding [37] may help guide novel closed-loop communication-based BMI systems. Targeting neuromodulation to modulator sites by delivering clinically-relevant high-frequency electrical stimulation may shut down sender-receiver communication, in effect by activating the modulator to suppress the receiver response to the sender [37]. Alternatively, neuromodulation that depends on decoding modulator activity to predict channel state and control a sender-receiver channel may effectively restore disordered multiregional communication. Future work is needed to develop these ideas and evaluate whether BMI technologies that manipulate multiregional communication can improve the current therapeutic efficacy of neuromodulation procedures [48].

Conclusions

Here, we have discussed the channel modulation hypothesis that defines flexible multiregional communication in terms of dynamically-interacting sender and receiver populations. We argue that convergent evidence from behavioral, neuronal recordings and causal manipulations highlights the role of network excitability in modulating multiregional communication with implications for neuromodulatory therapies.

Highlights.

Multiregional communication involves dynamically-interacting neuronal populations

Communication fluctuates in time to allow for flexible behavior

The communication channel hypothesis outlines a sender-receiver framework

Changes in excitability at the sender or receiver can control flexible communication

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health [R01-EY024067, R01-NS104923, U01-NS103518, U01-NS099697]; the National Science Foundation [IOS-1157786], the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency [N66001-17-C-4002,W911NF-14-2-0043], the Simons Foundation, New York, NY [grant number 325548]; the Army Research Office [grant number 68984-CS-MUR], the Australian Research Council [DE180100344, DP200100179] and the National Health and Medical Research Council [Australia, APP1185442].

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hahn G, Ponce-Alvarez A, Deco G, Aertsen A, Kumar A: Portraits of communication in neuronal networks. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20:117–127.**Hahn et al. provide a dynamical systems framework that synthesizes oscillation- and synchrony-based communication mechanisms. They hypothesize that nested slow and fast oscillations may play a role in controlling multiregional communication.

- 2.Marder E, O’Leary T, Shruti S: Neuromodulation of circuits with variable parameters: single neurons and small circuits reveal principles of state-dependent and robust neuromodulation. Annu Rev Neurosci 2014, 37:329–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halassa MM, Kastner S: Thalamic functions in distributed cognitive control. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20:1669–1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pashler H: Dual-task interference in simple tasks: data and theory. Psychol Bull 1994, 116:220–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigman M, Dehaene S: Dynamics of the central bottleneck: dual-task and task uncertainty. PLoS Biol 2006, 4:e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe K, Funahashi S: A dual-task paradigm for behavioral and neurobiological studies in nonhuman primates. J Neurosci Methods 2015, 246:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean HL, Hagan MA, Pesaran B: Only coherent spiking in posterior parietal cortex coordinates looking and reaching. Neuron 2012, 73:829–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean HL, Martí D, Tsui E, Rinzel J, Pesaran B: Reaction time correlations during eye-hand coordination: behavior and modeling. J Neurosci 2011, 31:2399–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazquez Y, Federici L, Pesaran B: Multiple spatial representations interact to increase reach accuracy when coordinating a saccade with a reach. J Neurophysiol 2017, 118:2328–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wimmer RD, Schmitt LI, Davidson TJ, Nakajima M, Deisseroth K, Halassa MM: Thalamic control of sensory selection in divided attention. Nature 2015, 526:705–709.**Wimmer et al. use causal manipulations of PFC and the visual thalamic reticular nucleus to show that attention in a multisensory task depends on both areas. They find that PFC alters sensory gain in visTRN, thereby selecting specific sensory information for downstream processing.

- 11.Hagan MA, Dean HL, Pesaran B: Spike-field activity in parietal area LIP during coordinated reach and saccade movements. J Neurophysiol 2012, 107:1275–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yttri EA, Wang C, Liu Y, Snyder LH: The parietal reach region is limb specific and not involved in eye-hand coordination. Journal of Neurophysiology 2014, 111:520–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Markowitz DA, Shewcraft RA, Wong YT, Pesaran B: Competition for visual selection in the oculomotor system. J Neurosci 2011, 31:9298–9306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rikhye RV, Gilra A, Halassa MM: Thalamic regulation of switching between cortical representations enables cognitive flexibility. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21:1753–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y, Zhaoping L, Li W: Bottom-up saliency and top-down learning in the primary visual cortex of monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:10499–10504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Zirnsak M, Vega GM, Govil E, Lomber SG, Moore T: Parietal Cortex Regulates Visual Salience and Salience-Driven Behavior. Neuron 2020, 106:177–187.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sapountzis P, Paneri S, Gregoriou GG: Distinct roles of prefrontal and parietal areas in the encoding of attentional priority. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:E8755–E8764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregoriou GG, Gotts SJ, Zhou H, Desimone R: High-frequency, long-range coupling between prefrontal and visual cortex during attention. Science 2009, 324:1207–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachman MD, Wang L, Gamble ML, Woldorff MG: Physical Salience and Value-Driven Salience Operate through Different Neural Mechanisms to Enhance Attentional Selection. J Neurosci 2020, 40:5455–5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itthipuripat S, Vo VA, Sprague TC, Serences JT: Value-driven attentional capture enhances distractor representations in early visual cortex. PLoS Biol 2019, 17:e3000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daw ND, Gershman SJ, Seymour B, Dayan P, Dolan RJ: Model-based influences on humans’ choices and striatal prediction errors. Neuron 2011, 69:1204–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dal Monte O, Chu CCJ, Fagan NA, Chang SWC: Specialized medial prefrontal-amygdala coordination in other-regarding decision preference. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friston KJ: Functional and effective connectivity: a review. Brain Connect 2011, 1:13–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesaran B: Neural correlations, decisions, and actions. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2010, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saalmann YB, Pinsk MA, Wang L, Li X, Kastner S: The pulvinar regulates information transmission between cortical areas based on attention demands. Science 2012, 337:753–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fries P: Rhythms for Cognition: Communication through Coherence. Neuron 2015, 88:220–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastos AM, Vezoli J, Bosman CA, Schoffelen J-M, Oostenveld R, Dowdall JR, De Weerd P, Kennedy H, Fries P: Visual areas exert feedforward and feedback influences through distinct frequency channels. Neuron 2015, 85:390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastos AM, Schoffelen J-M: A Tutorial Review of Functional Connectivity Analysis Methods and Their Interpretational Pitfalls. Front Syst Neurosci 2015, 9:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semedo JD, Zandvakili A, Machens CK, Yu BM, Kohn A: Cortical Areas Interact through a Communication Subspace. Neuron 2019, 102:249–259.e4.**Semedo et al. show that multiregional communication between V1 to V2 depends on the patterns of activity across a V1 populations. Fluctuations in V2 are driven by low-dimensional activity in V1, which they term a communication subspace, providing evidence for sender-dependent multiregional communication.

- 30.Lakatos P, Karmos G, Mehta AD, Ulbert I, Schroeder CE: Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection. Science 2008, 320:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li N, Daie K, Svoboda K, Druckmann S: Corrigendum: Robust neuronal dynamics in premotor cortex during motor planning. Nature 2016, 537:122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuster JM, Bauer RH, Jervey JP: Functional interactions between inferotemporal and prefrontal cortex in a cognitive task. Brain Res 1985, 330:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt LI, Wimmer RD, Nakajima M, Happ M, Mofakham S, Halassa MM: Thalamic amplification of cortical connectivity sustains attentional control. Nature 2017, 545:219–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiebelkorn IC, Saalmann YB, Kastner S: Rhythmic sampling within and between objects despite sustained attention at a cued location. Curr Biol 2013, 23:2553–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mathewson KE, Gratton G, Fabiani M, Beck DM, Ro T: To See or Not to See: Prestimulus α Phase Predicts Visual Awareness. J Neurosci 2009, 29:2725–2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein A, Fontolan L, Economo MN, Li N, Romani S, Svoboda K: Attractor dynamics gate cortical information flow during decision-making. 2019, doi: 10.1101/2019.12.14.876425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiao S, Sedillo JI, Brown KA, Ferrentino B, Pesaran B: A Causal Network Analysis of Neuromodulation in the Mood Processing Network. Neuron 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.012.**Qiao et al. performed a novel causal network analysis to decode and manipulate multiregional communication across 15 cortico-subcortical and limbic brain regions. This work introduces the concept of an excitability-based neuromodulation brain-machine interface to decode and manipulate multiregional communication.

- 38.Jazayeri M, Afraz A: Navigating the Neural Space in Search of the Neural Code. Neuron 2017, 93:1003–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tehovnik EJ, Slocum WM: Two-photon imaging and the activation of cortical neurons. Neuroscience 2013, 245:12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bensmaia SJ, Miller LE: Restoring sensorimotor function through intracortical interfaces: progress and looming challenges. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014, 15:313–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shanechi MM: Brain-machine interfaces from motor to mood. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22:1554–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shenoy KV, Carmena JM: Combining decoder design and neural adaptation in brain-machine interfaces. Neuron 2014, 84:665–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orsborn AL, Pesaran B: Parsing learning in networks using brain-machine interfaces. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2017, 46:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, Dunlop K, Mansouri F, Meng Y, Fetcho RN, Zebley B, Oathes DJ, Etkin A, et al. : Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nature Medicine 2017, 23:28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sani OG, Yang Y, Lee MB, Dawes HE, Chang EF, Shanechi MM: Mood variations decoded from multi-site intracranial human brain activity. Nat Biotechnol 2018, 36:954–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Howland RH, Bhati MT, O’Reardon JP, Eskandar EN, Baltuch GH, Machado AD, Kondziolka D, et al. : A Randomized Sham-Controlled Trial of Deep Brain Stimulation of the Ventral Capsule/Ventral Striatum for Chronic Treatment-Resistant Depression. Biological Psychiatry 2015, 78:240–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs J, Miller J, Lee SA, Coffey T, Watrous AJ, Sperling MR, Sharan A, Worrell G, Berry B, Lega B, et al. : Direct Electrical Stimulation of the Human Entorhinal Region and Hippocampus Impairs Memory. Neuron 2016, 92:983–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lozano AM, Lipsman N, Bergman H, Brown P, Chabardes S, Chang JW, Matthews K, McIntyre CC, Schlaepfer TE, Schulder M, et al. : Deep brain stimulation: current challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol 2019, 15:148–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]