Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Does septum resection improve reproductive outcomes in women with a septate uterus?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Hysteroscopic septum resection does not improve reproductive outcomes in women with a septate uterus.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

A septate uterus is a congenital uterine anomaly. Women with a septate uterus are at increased risk of subfertility, pregnancy loss and preterm birth. Hysteroscopic resection of a septum may improve the chance of a live birth in affected women, but this has never been evaluated in randomized clinical trials. We assessed whether septum resection improves reproductive outcomes in women with a septate uterus, wanting to become pregnant.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

We performed an international, multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial in 10 centres in The Netherlands, UK, USA and Iran between October 2010 and September 2018.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Women with a septate uterus and a history of subfertility, pregnancy loss or preterm birth were randomly allocated to septum resection or expectant management. The primary outcome was conception leading to live birth within 12 months after randomization, defined as the birth of a living foetus beyond 24 weeks of gestational age. We analysed the data on an intention-to-treat basis and calculated relative risks with 95% CI.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

We randomly assigned 80 women with a septate uterus to septum resection (n = 40) or expectant management (n = 40). We excluded one woman who underwent septum resection from the intention-to-treat analysis, because she withdrew informed consent for the study shortly after randomization. Live birth occurred in 12 of 39 women allocated to septum resection (31%) and in 14 of 40 women allocated to expectant management (35%) (relative risk (RR) 0.88 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.65)). There was one uterine perforation which occurred during surgery (1/39 = 2.6%).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

Although this was a major international trial, the sample size was still limited and recruitment took a long period. Since surgical techniques did not fundamentally change over time, we consider the latter of limited clinical significance.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The trial generated high-level evidence in addition to evidence from a recently published large cohort study. Both studies unequivocally do not reveal any improvements in reproductive outcomes, thereby questioning any rationale behind surgery.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

There was no study funding. M.H.E. reports a patent on a surgical endoscopic cutting device and process for the removal of tissue from a body cavity licensed to Medtronic, outside the scope of the submitted work. H.A.v.V. reports personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. B.W.J.M. reports grants from NHMRC, personal fees from ObsEva, personal fees from Merck Merck KGaA, personal fees from Guerbet, personal fees from iGenomix, outside the submitted work. M.G. reports several research and educational grants from Guerbet, Merck and Ferring (location VUMC) outside the scope of the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to declare.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

Dutch trial registry: NTR 1676

TRIAL REGISTRATION DATE

18 February 2009

DATE OF FIRST PATIENT’S ENROLMENT

20 October 2010

Keywords: septum resection, septate uterus, live birth, pregnancy loss, subfertility

Introduction

The septate uterus is a congenital uterine anomaly. It is infrequently detected, with an estimated prevalence of around 0.2–2.3% in women of reproductive age (Saravelos et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2011b). Women with a septate uterus are at increased risk for subfertility, pregnancy loss and preterm birth (Chan et al., 2011a). Hysteroscopic septum resection is currently standard practice to restore normal uterine anatomy, with the aim of improving reproductive outcomes.

At present, the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) guideline for management of the septate uterus recommends hysteroscopic resection (ASRM, 2016). In contrast, guidance on recurrent pregnancy loss associated with a septate uterus from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) do not support the use of the procedure, until adequate studies would have demonstrated its effectiveness (RCOG, 2011; NICE, 2015; ESHRE, 2018).

Recently, a large cohort study including 257 women with a septate uterus, showed that surgery did not improve chance of conception, nor did it appear to prevent pregnancy loss or preterm birth. Surgical complications occurred in seven women (4.6%) (Rikken et al., 2020).

To provide a higher level of evidence, we here performed a randomized controlled trial comparing hysteroscopic septum resection with expectant management in women with a septate uterus.

Materials and methods

Design

This study was designed as an international, multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial carried out in centres with expertise in hysteroscopic septum resection. These centres were three tertiary-care and four secondary-care hospitals collaborating in the Dutch Consortium for Women’s Health Research, and three tertiary-care hospitals in the USA, UK and Iran, respectively.

Ethical approval

The TRUST (The Randomised Uterine Septum Trial) trial was registered within the Netherlands Trial Register, number NTR1676. The trial protocol and all subsequent amendments were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Academic Medical Centre (IDS NL24082.018.08 MEC Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam), The Netherlands on 28 October 2008 (MEC 08/245), and by the boards of directors of all participating hospitals.

All adverse and serious adverse events suspected of having a causal relationship to surgery were recorded. A serious adverse event was defined as death or illness necessitating intensive care unit (ICU) treatment. All serious adverse events had to be reported to the ethics committee of the Academic Medical Centre, Amsterdam. The study protocol has been published previously (Rikken et al., 2018).

Eligible women were provided with trial information verbally and in writing by consultant gynaecologists or dedicated research employees at the outpatient clinics. All women provided written informed consent. Women could withdraw from the trial at any time.

Study population

Women of reproductive age with a septate uterus, wanting to become pregnant and with a history of subfertility, pregnancy loss or preterm birth were eligible. Women with a contraindication to surgery were not eligible. Initially, after ethical study approval only women with recurrent pregnancy loss were included. During the course of the trial, the eligibility criteria were extended to include women with a history of subfertility (2011), one pregnancy loss or preterm birth (2015). This broadening of inclusions was based on a systematic review published in 2011 that showed that women with a septate uterus had reduced clinical pregnancy rates and increased rates of pregnancy loss and preterm birth when compared with women with normal uteri (Chan et al., 2011a,b). A septate uterus was diagnosed by the treating consultant according to the leading classification systems at that time of recruitment (AFS, 1988; Grimbizis et al., 2013; ASRM, 2016). The presence of a uterine septum had to be ascertained by hysterosalpingography, 3-dimensional pelvic ultrasound, MRI, saline or gel infusion sonohysterography or hysteroscopy combined with laparoscopy (Faivre et al., 2012; Ludwin et al., 2013; Siam and Soliman, 2014; Graupera et al., 2015).

Definitions

The following list of definitions was used. Subfertility: the inability to conceive for a minimal period of 12 months of trying to conceive (Zegers-Hochschild et al., 2017); Pregnancy loss: the spontaneous demise of a pregnancy before 24 weeks of gestation, including non-visualized or biochemical pregnancies, confirmed by either serum or urine b-HCG; Recurrent pregnancy loss: two or more, not necessarily consecutive, pregnancy losses (ESHRE, 2018); Preterm birth: birth before a gestational age of 37 complete weeks (Blencowe et al., 2013); Clinical pregnancy: the presence of a foetal heartbeat at or beyond 6 weeks of pregnancy; Ongoing pregnancy: a viable intrauterine pregnancy of at least 12 weeks duration, confirmed on an ultrasound scan (Braakhekke et al., 2014).

Randomization and blinding

Women were randomly allocated (1:1) to hysteroscopic septum resection or expectant management, by use of a central password protected internet-based randomization programme. The randomization list behind the programme was prepared by an independent statistician with a variable block size with randomly selected block sizes that varied between two, four and six. There was no stratification. Neither the recruiters nor the trial project group could access the randomization sequence. Because of the nature of the interventions, blinding women or doctors was impossible.

Procedures

Women allocated to hysteroscopic septum resection had their surgical procedure performed under general or loco-regional anaesthesia. The choice of instrumentation was left to the participating surgeon, which could include monopolar or bipolar resectoscopes with needle and/or loop electrosurgical electrodes, bipolar vaporization electrodes (Versapoint®) or conventional mechanical scissors. To monitor the depth of the myometrial resection and to prevent uterine perforation during surgery, laparoscopic or ultrasound monitoring was advised (Zhang et al., 2015). To assess the results of the septum resection, a diagnostic control hysteroscopy 6–8 weeks postoperatively was performed in an outpatient setting.

Women allocated to expectant management did not receive any specific intervention and were advised to continue trying to conceive naturally or with assisted reproductive technologies in case of subfertility. In women with recurrent pregnancy loss and co-existing antiphospholipid syndrome, low dose aspirin or low molecular weight heparin were allowed. Women could opt for hysteroscopic septum resection if the first pregnancy after randomization resulted in a pregnancy loss or if pregnancy did not occur after 1 year of follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was conception leading to live birth within 12 months after randomization. Live birth was defined as the birth of a living foetus beyond 24 weeks of gestational age. Secondary outcomes included clinical pregnancy, pregnancy loss, ongoing pregnancy and preterm birth, with conception leading to these outcomes within 12 months after randomization. In women with an ongoing pregnancy, pregnancy outcomes such as multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, placental abruption, uterine rupture and mode of delivery were assessed. Data on specific complications during and following hysteroscopic septum resection, like uterine perforation, fluid overload and endometritis, were collected. We followed women for at least 1 year, and followed those who conceived within that period for the course of that pregnancy. If women had a pregnancy loss within 1 year, we followed them until the next conception leading to live birth if within 12 months after randomization, or otherwise until 12 months after randomization.

Sample size

For the sample size calculation, we estimated live birth rate to be 35% in women with a septate uterus without surgery and we expected an increase to 70% with surgery, based on retrospective studies (Homer et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2011a). Using a two-sided test, an alpha-error of 5% and a beta-error of 20%, 62 women were needed to demonstrate this difference. Anticipating lost-to-follow-up and protocol violations, an additional 10% was needed. Thus, a minimum of 68 women needed to be randomized. Because of the small sample size, we did not plan an interim analysis.

Statistical analysis

We analysed the data on intention-to-treat basis. We calculated relative risks and 95% CIs for all pregnancy outcomes. To account for time to conception leading to live birth, we constructed Kaplan–Meier curves using the log-rank test to compare the treatment arms and calculated the corresponding hazard rates with 95% CI. Additionally, we performed a per-protocol analysis limited to women who were treated according to their allocated study arm, regardless of first having a pregnancy loss or not having become pregnant. We used SPSS® (IBM 2019, USA) software for all statistical analyses (version 25).

Results

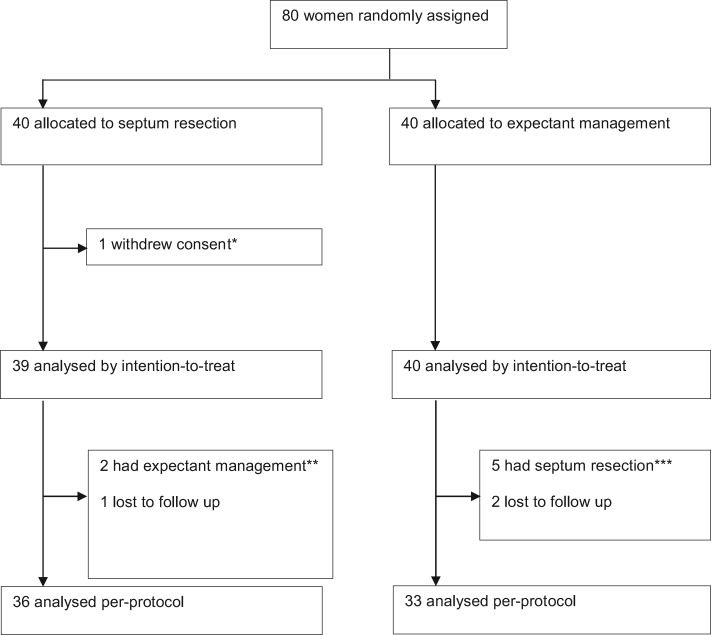

Between 20 October 2010 and 3 September 2018, 80 women were randomly assigned and allocated to septum resection (n = 40) or expectant management (n = 40) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile. *One woman withdrew informed consent immediately after being randomized as she did not prefer a septum resection. **Two women appeared to have no septate uterus at time of surgery and hence septum resection was cancelled. ***One woman had a septum resection after 1 month, three women after 4 months and one woman after 9 months of follow-up.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two treatment arms (Table I). Surgical details of women allocated to septum resection are shown in Table II. One uterine perforation occurred immediately after introduction of the hysteroscope, after which the surgeon stopped the procedure without any further interventions needed. The septum was removed 4 weeks later without further complications. Serious adverse events (death or illness necessitating ICU treatment) were not reported. Seven women did not have monitoring via laparoscopy or ultrasound during surgery, which we documented as a protocol deviation. There were 27 women (69%) who had a control hysteroscopy at 6 weeks follow-up. Two women had a residual septum, including the woman with the uterine perforation. Both women underwent a second procedure.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics.

| Septum resection (n = 39) | Expectant management (n = 40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 31.0 (29–32) | 31.7 (30–33) |

| Parity | ||

| 0 | 31 (80) | 32 (80) |

| 1 | 6 (15) | 7 (18) |

| >1 | 2 (5) | 1 (2) |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25 (24–27) | 25 (23–26) |

| Smoker | ||

| Yes | 3 (8) | 5 (13) |

| No | 36 (92) | 35 (87) |

| Inclusion criteria ** | ||

| Pregnancy loss | 23 (59) | 27 (67) |

| Subfertility | 15 (39) | 13 (33) |

| Preterm birth | 2 (5) | 4 (10) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Partial septum | 35 (92) | 36 (90) |

| Complete septum | 3 (8) | 4 (10) |

| Unknown | 1 | |

| Diagnostic procedure *** | ||

| SIS/GIS | 4 (10) | 4 (10) |

| 3D ultrasound | 11 (28) | 15 (38) |

| MRI | 6 (15) | 7 (18) |

| Hysteroscopy + laparoscopy | 21 (54) | 17 (43) |

| HSG | 9 (23) | 3 (7.5) |

Data are in mean (standard deviation) or n (%).

BMI, body mass index; GIS, gel infusion sonohysterography; HSG, hysterosalpingography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SIS, saline infusion sonohysterography.

Women could have more than one inclusion criterium.

Combinations of diagnostic procedures could have been used.

Table II.

Surgical details for women allocated to uterine septum resection.

| Septum resection (n = 39) | |

|---|---|

| Energy modality | |

| Resectoscope (needle- or loop electrode) | 25 (64) |

| Vaporization electrode (Versapoint®) | 7 (18) |

| Mechanical—scissors | 5 (13) |

| No resection | 2 (5) |

| Concomitant imaging | |

| Laparoscopy | 28 (72) |

| Ultrasound | 4 (10) |

| None | 7 (18) |

| Successful (complete resection) * | |

| Yes | 36 (92) |

| Uterine perforation | |

| Yes | 1 (2.6) |

| Control hysteroscopy** | |

| Yes | 27 (69) |

| Repeat procedure (incomplete resection) | |

| Yes | 2 (5.1) |

Data are in n (%).

Successful was defined as removal of the septum without complications as assessed at the end of the procedure.

**Hysteroscopy at 6 weeks of follow-up to assess the anatomy of the uterus.

Reproductive outcomes

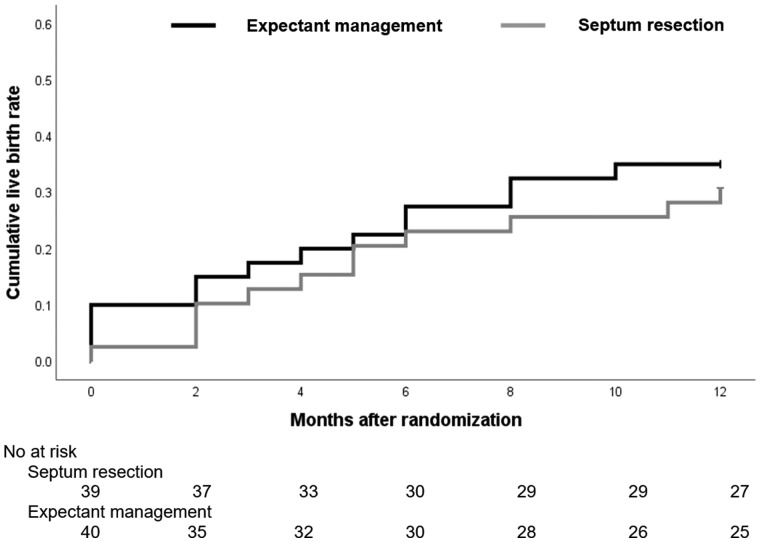

Reproductive outcomes are summarized in Table III. In the intention-to-treat analysis, 12 of 39 women who were allocated to septum resection (31%) had a live birth, compared to 14 of 40 women who were allocated to expectant management (35%); this corresponds to a RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.47–1.7) and an absolute risk difference of minus 4.2% (95% CI −24.9% to 16.5%). There was also no evidence of a difference in clinical pregnancy, ongoing pregnancy, pregnancy loss or preterm birth rates. The mean time to conception leading to live birth was 9.8 months (95% CI 8.6 to 11) following randomization for septum resection and 9.2 months (95% CI 7.8 to 11) after randomization for expectant management (log rank: P = 0.64). The corresponding hazard ratio (HR) was 0.83 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.9) (Fig. 2).

Table III.

Reproductive outcomes—intention-to-treat analysis.

| Septum resection (n = 39) | Expectant management (n = 40) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Live birth | 12 (31%) | 14 (35%) | 0.88 (0.47–1.7) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Ongoing pregnancy* | 13 (33%) | 14 (35%) | 0.95 (0.52–1.8) |

| Clinical pregnancy | 22 (56%) | 19 (48%) | 1.2 (0.77–1.2) |

| Pregnancy loss** | 11 (28%) | 5 (13%) | 2.3 (0.86–5.9) |

| Preterm birth | 5 (13%) | 4 (10%) | 1.3 (0.37–4.4) |

Data are in n (%).

RR, relative risk.

One woman who underwent septum resection had an ongoing pregnancy that ended in a late pregnancy loss at 17 weeks.

One woman had a biochemical pregnancy that ended in a pregnancy loss at 5 weeks.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of cumulative live birth rate in women who underwent septum resection and women who had expectant management.

In women with an ongoing pregnancy, breech presentation at the time of delivery occurred in two women were allocated to septum resection and in six women who were allocated to expectant management (Table IV). Of 13 women who allocated to septum resection, 9 (69%) had a caesarean section while 5 of 14 women who allocated to expectant management (36%) had a caesarean section (RR 1.9 (95% CI 0.88 to 5.0)). The reasons for a caesarean section in women who were allocated to septum resection were elective reasons (n = 3), non-progressive labour (n = 1), foetal distress (n = 1), placenta praevia (n = 1) or unknown (n = 4), and the reasons in women who were allocated to expectant management were breech presentation (n = 3) or foetal distress (n = 2). Two women in the septum resection arm had twin pregnancies (15%) versus none in the expectant management arm. There were no cases of ectopic pregnancy, uterine rupture, placental abruption, postpartum haemorrhage or intra-uterine foetal death.

Table IV.

Pregnancy outcomes for women with an ongoing pregnancy—intention-to-treat.

| Septum resection (n = 13) | Expectant management (n = 14) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation at term | |||

| Cephalic | 11 (85%) | 7 (54%) | 1.6 (0.87–2.8) |

| Breech | 2 (15%) | 6 (46%) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 | |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Caesarean section | 9 (69%) | 5 (36%) | 1.9 (0.88–5.0) |

| Spontaneous | 4 (31%) | 9 (64%) |

Data are in n (%).

RR, relative risk.

Per-protocol analysis

In line with the intention-to-treat analysis, the per-protocol analysis showed no evidence of a difference in live birth, ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, pregnancy loss or preterm birth, RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.5), RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.9), RR 1.1 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.7), RR 1.83 (95% CI 0.70 to 4.8) and RR 1.2 (95% CI 0.34 to 3.9), for septum resection versus expectant management respectively) (Table V).

Table V.

Reproductive outcomes—per-protocol analysis.

| Septum resection (n = 36) | Expectant management (n = 33) | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Live birth | 12 (33%) | 12 (36%) | 0.92 (0.55–1.5) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Ongoing pregnancy* | 13 (36%) | 12 (36%) | 0.99 (0.53–1.9) |

| Clinical pregnancy | 21 (58%) | 17 (52%) | 1.1 (0.74–1.7) |

| Pregnancy loss | 10 (28%) | 5 (15%) | 1.8 (0.70–4.8) |

| Preterm birth | 5 (14%) | 4 (12%) | 1.2 (0.34–3.9) |

Data are in n (%).

RR, relative risk.

One woman who underwent septum resection had an ongoing pregnancy that ended in a late pregnancy loss at 17 weeks.

Discussion

In this international, multicentre, open-label, randomized controlled trial in women with a septate uterus, septum resection did not improve live birth rates compared with expectant management. There was also no evidence of a difference in other reproductive outcomes, like ongoing pregnancy, pregnancy loss and preterm birth rates. One complication of treatment, a perforation of the uterus, was sustained during septum resection.

Our study has a number of strengths. We performed a pragmatic study, in which we included women who had been diagnosed by their treating gynaecologist in 10 centres in four countries worldwide, based on the leading classification at that time. This reflects daily practices and ensures a high generalizability of the study results. Whilst an accepted classification of uterine anomalies remains elusive (Grimbizis et al., 2013; ASRM, 2016; Ludwin et al., 2018), it seems unlikely that subtle changes in the definition of a uterine septum, would impact substantially upon our findings. In addition, there was a high compliance, i.e. only a few women were lost to follow-up (4 women, 5%).

A limitation of our study is that with our sample size of 68 women, we were able to detect an improvement in live birth from 35% to 70% with surgery, which we expected based on the existing literature at the start of the study (Homer et al., 2000). To detect a smaller improvement of 10% in live births, for example from 35% to 45%, new studies would need to recruit at least 752 women. Any effort to confirm or refute the results of this trial would thus need a worldwide, dedicated and adequately resourced collaboration. Such an enterprise is unlikely to be feasible, especially if one considers that the only other randomized controlled trial comparing septum resection with expectant management carried out in the UK was forced to stop because of poor recruitment; six patients in a recruitment period of 3 years (pilot randomized controlled trial of hysteroscopic septum resection, ISRCTN28960271).

Our findings are in line with our recently published international multicentre cohort study of 257 women with a septate uterus, which showed no differences in live birth rates between women who underwent septum resection and women following expectant management, adjusted for possible confounders (53% vs 72%, respectively, HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.02) (Rikken et al., 2020).

Our study was not powered to evaluate any differential effect of septum resection in women with pregnancy loss compared with those presenting with subfertility, or according to the number of pregnancy losses, nor was it powered to evaluate any possible differential effect of the size of the uterine septum. Complete septa are less common than incomplete septa and represented under 10% of our trial population. Of the seven women with a complete septate uterus, live birth occurred in two of three women (66.7%) who underwent septum resection, and 3 of 4 women (75%) who had expectant management.

The findings of this randomized controlled trial show that hysteroscopic septum resection does not improve live birth rates or other reproductive outcomes in women with a septate uterus. The surgical procedure, by definition, has the propensity for harm, with one peri-operative uterine perforation occurring in a woman undergoing septum resection in this trial. Thus, in light of the lack of any evidence of effectiveness and the potential for harm, we recommend against septum resection as a routine procedure in clinical practice. Women with a septate uterus need to be informed about the data of this study. After counselling, according to the principles of shared decision-making, an informed decision can then be made.

Data availability

Request for data collected for the study can be made to the co-corresponding authors and will be considered on an individual basis. Additional, study-related documents are immediately available and can be requested from the co-corresponding authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank all women who participated in this trial, all participating institutions and their staff and research employees for their contribution to this study, and all recruiting staff and research employees in all hospitals in the Netherlands who referred their patients to one of the participating centres.

Authors’ roles

C.R.K., B.W.J.M. and M.G. designed the study. C.R.K. and J.F.W.R. coordinated the trial. J.F.W.R. collected the data. M.H.E., M.Y.B., T.S., F.W.J., A.G.M.G.J.M. and H.A.v.V. managed the trial in the hospitals in the Netherlands, and commented on the paper. R.P. is responsible for the trial in Iran, T.J.C. in the UK and M.D.S. in the USA, and all commented on the draft paper. J.F.W.R. and M.v.W. performed the statistical analyses. J.F.W.R., M.v.W., M.G. and F.v.d.V. drafted the paper. All authors interpreted the data, critically revised the article and approved the final version.

Funding

There was no funder of this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict of interest

H.A.v.V. reports personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work. B.W.J.M. reports grants from NHMRC, personal fees from ObsEva, personal fees from Merck Merck KGaA, personal fees from Guerbet and personal fees from iGenomix, outside the submitted work. M.G. works at the Department of Reproductive Medicine of the Amsterdam UMC (Location AMC and location VUMC). Location VUMC has received several research and educational grants from Guerbet, Merck and Ferring, outside the scope of the submitted work. M.H.E. reports a patent on a surgical endoscopic cutting device and process for the removal of tissue from a body cavity licensed to Medtronic, outside the context of the submitted work. The remaining authors have nothing to declare.

References

- AFS. The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, mullerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril 1988;49:944–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASRM. Uterine septum: a guideline. Fertil Steril 2016;106:530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller AB, Kinney M, Lawn J; the Born Too Soon Preterm Birth Action Group (see acknowledgement for full list). Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health 2013;10:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braakhekke M, Kamphuis EI, Dancet EA, Mol F, van der Veen F, Mol BW.. Ongoing pregnancy qualifies best as the primary outcome measure of choice in trials in reproductive medicine: an opinion paper. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1203–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Tan A, Thornton JG, Coomarasamy A, Raine-Fenning NJ.. Reproductive outcomes in women with congenital uterine anomalies: a systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011a;38:371–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, Thornton JG, Raine-Fenning N, Coomarasamy A.. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2011b;17:761–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL, Bender Atik R, Christiansen OB, Elson J, Kolte AM, Lewis S, Middeldorp S, Nelen W, Peramo B, Quenby S, Vermeulen N, Goddijn M. ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Open 2018; doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoy004. PMID: 31486805; PMCID: PMC6276652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Faivre E, Fernandez H, Deffieux X, Gervaise A, Frydman R, Levaillant JM.. Accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of septate and bicornuate uterus compared with office hysteroscopy and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2012;19:101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graupera B, Pascual MA, Hereter L, Browne JL, Ubeda B, Rodriguez I, Pedrero C.. Accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasound compared with magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis of Mullerian duct anomalies using ESHRE-ESGE consensus on the classification of congenital anomalies of the female genital tract. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:616–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Brucker S, De Angelis C, Gergolet M, Li TC, Tanos V, Brolmann H, Gianaroli L. et al. The ESHRE-ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Gynecol Surg 2013;10:199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer HA, Li TC, Cooke ID.. The septate uterus: a review of management and reproductive outcome. Fertil Steril 2000;73:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwin A, Martins WP, Nastri CO, Ludwin I, Coelho Neto MA, Leitao VM, Acien M, Alcazar JL, Benacerraf B, Condous G. et al. Congenital Uterine Malformation by Experts (CUME): better criteria for distinguishing between normal/arcuate and septate uterus? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018;51:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwin A, Pityński K, Ludwin I, Banas T, Knafel A.. Two- and three-dimensional ultrasonography and sonohysterography versus hysteroscopy with laparoscopy in the differential diagnosis of septate, bicornuate, and arcuate uteri. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013;20:90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Guideline: Hysteroscopic metroplasty of a uterine septum for primary infertility. 2015:1–8.

- RCOG. Guideline: The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent first-trimester and second-trimester miscarriage. 2011:1–18.

- Rikken JFW, Kowalik CR, Emanuel MH, Bongers MY, Spinder T, de Kruif JH, Bloemenkamp KWM, Jansen FW, Veersema S, Mulders AGMGJ. et al. The randomised uterine septum transsection trial (TRUST): design and protocol. BMC Women's Health 2018;18:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rikken JFW, Verhorstert KWJ, Emanuel MH, Bongers MY, Spinder T, Kuchenbecker W, Jansen FW, van der Steeg JW, Janssen CAH, Kapiteijn K. et al. Septum resection in women with a septate uterus: a cohort study. Hum Reprod 2020;35:1722–1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravelos SH, Cocksedge KA, Li TC.. Prevalence and diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies in women with reproductive failure: a critical appraisal. Hum Reprod Update 2008;14:415–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siam S, Soliman BS.. Combined laparoscopy and hysteroscopy for the detection of female genital system anomalies results of 3,811 infertile women. J Reprod Med 2014;59:542–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, Rienzi L, Sunde A, Schmidt L, Cooke ID. et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Hum Reprod 2017;32:1786–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yang L, Yang SL, Zhao Q, Xie Y.. Ultrasonography versus laparoscopy in transcervical resection of septa: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2015;42:515–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Request for data collected for the study can be made to the co-corresponding authors and will be considered on an individual basis. Additional, study-related documents are immediately available and can be requested from the co-corresponding authors.