ABSTRACT

Aim

To assess the children’s perceptions of the dentist’s attire and environment. The protocol is available in the PROSPERO database.

Search strategies

Systematic searches in the databases were performed in Cochrane, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences, PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science from their inception to December 12, 2019, Google Scholar, Open Grey, and ProQuest Dissertations.

Selection criteria

Criteria consisted of descriptive studies regarding the above matter while two authors assessed the information. The risk of bias was also performed.

Results

Databases showed 1,544 papers and a two-phase assessment selected 21 studies in narrative and 9 in the quantitative synthesis. A meta-analysis demonstrated no difference between white coat and child-friendly attire (OR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.16–2.49; n = 3,706) and a decorated vs plain dental clinic was the preference of the children’s majority (OR = 8.75; 95% CI 1.21–63.37; n = 150).

Conclusion

It can be concluded that there is no difference in the children’s perception, white coat vs child-friendly attire; however, children prefer a decorated dental clinic.

How to cite this article

Oliveira LB, Massignan C, De Carvalho RM, et al. Children’s Perceptions of Dentist’s Attire and Environment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020;13(6):700–716.

Keywords: Attire, Child, Dental offices, Dental service, Patient preference.

INTRODUCTION

Dental anxiety, fear, or phobia is time-consuming, costly, and demanding issues that promote oral health commitment and a strong negative impact on the dentist’s image.1,2 This aspect may postpone the treatment and aggravate the oral condition, followed by lower life quality.3–5

Children’s low or moderate fear as well as anxiety can be effectively managed when the dental professional can promote confidence, good communication, empathy, careful treatment, and some basic nonpharmacological approaches. On the contrary, high anxious/fearful or phobic children may require specific treatment approaches including nitrous oxide sedation or general anesthesia which represents a high cost.6,7

Friendly relationship and rapport between the child and dentist and the dental are of utmost importance to promote successful dental treatment.8–10 A recent study has also concluded that the dental team’s understanding of children’s attitudes creates a comfortable environment that improves the quality of the visit and reduces anxiety.

Some authors11 stated that the children regularly judge their dentist anchored in words and gestures during a dental appointment. Physical appearance plays a crucial role in the dentist–patient relationship.10 Previous studies evaluated children’s perception toward dentists’ look and controversial results showed that children preferred their dentist in traditional attire,12–15 against a friendly or causal child-like attire.10,16,17 The dental environment also triggers an anxious response in children. Some studies demonstrated that an attractive physical dental environment decorated with toys for children can build up their positive relationship.

A previous systematic review18 examined the influence of physician attire on adults’ perceptions and the authors concluded that formal attire with or without white coats, or a white coat with other non-specified attire has been preferred in 60% of the eligible studies. Images of dentists dressed in white coats or formal suits have been associated with trust and confidence.

This study assessed the children’s dental perception answering the following PECOS (population, exposure, comparator, outcomes, and study design) research questions: “What are the children’s perceptions of the dentist’s attire?” and “what are the children’s perceptions of the dental environment?”

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis checklist.19 The protocol was available in PROSPERO under number CRD42018116473.

Study Design

This systematic review was based on these questions: “What are the children’s perceptions of the dentist’s attire?” and “what are the children’s perceptions of the dental environment?” Descriptive studies were included which evaluated the preference/perception of children about the dentist’s attire and the environment of the dental office. The studies could use questionnaires and/or photos to assess the child’s preference. Studies with different objectives, studies that evaluated dentist’s or parents’ perceptions were excluded. Secondary studies (articles review, letter to the editor, books, book chapters, etc.) and those with adult populations were also excluded.

Information Sources and Search Strategies

An experienced health sciences librarian helped with the search strategy with appropriate modification for each database (Supporting information Appendix 1).

The databases Cochrane, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences (LILACS), PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched from their inception to December 6, 2018, and updated on December 12, 2019. Google Scholar provided a limit of 100 most relevant articles for Gray literature; OpenGrey, ProQuest Dissertations, Theses Database, and the reference list were searched for additional studies. No restrictions were applied regarding dates or language. EndNote® X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, EUA) and Rayyan software20 (http://rayyan.qcri.org/) were used to manage references and duplicate hits were removed.

Study Selection and Data Collection

The selection process was performed in two phases by two independent reviewers (LBO and RMC). First, they assessed all retrieved titles and abstracts for eligibility. Second, the full-text articles were obtained and evaluated if both reviewers considered the abstract potentially relevant. Disagreements were settled by discussion involving the third reviewer (CM). The same process was used in data extraction. Two reviewers (LBO and CM) independently collected data and the results were compared. Discussion and consensus dissolved disagreement between the authors. Study characteristics (design/setting), population characteristics (sample size, age), and outcome characteristics (data analysis, findings, and conclusion) were provided in the primary studies.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The meta-analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (MAStARI) checklist was adopted by two reviewers (LBO and CM) to assess the methodological quality. The questionnaire for analytical cross-sectional studies was applied. All domains in the questionnaire were considered.

Summary Measures

Descriptive data/statistics (number and percentage) related to children’s perception of the dentist’s attire and their dental environment were considered the main outcomes. The children’s attires and dental clinic preferences were analyzed.

Synthesis of Results

A meta-analysis was planned within the studies presenting comparative data following the appropriate Cochrane Guidelines.21 Meta-analysis was performed with the aid of MedCalc Statistical Software version 14.8.1 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Heterogeneity was calculated by inconsistency indexes (I2), and a value >50% was considered an indicator of substantial heterogeneity between studies, and a random effect is prioritized.22 The level of significance was set at 5%.

RESULTS

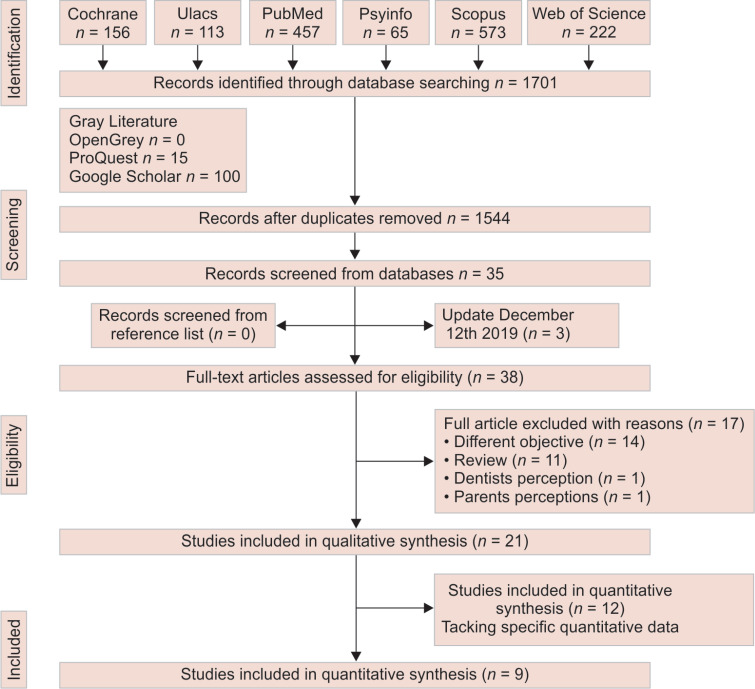

Study Selection (Flowchart 1)

Flowchart 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search and selection criteria

Phase 1 showed 1,544 papers across the six electronic databases after duplicates were removed. After abstract evaluation, 38 articles were considered potentially useful and selected for phase 2 assessment. There was no additional reference from Gray literature (Google Scholar, the OpenGrey, and ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database). No additional study was identified after the reference list of the 38 studies review. From these 38 remaining studies, 17 were subsequently excluded (Supporting information Appendix 2). Thus, 21 studies8,10,12–17,23–35 were included in qualitative analysis, and 9 studies were retained for the final meta-analysis aimed at answering the first question10,12,13,17,24,25,28,29,33 (What are the children’s perceptions of the dentist’s attire?”). From these 21 studies, only two studies24,29 included information regarding decorated dental clinic and plain clinic and were used in the meta-analysis aiming to answer the second question (What are the children’s perceptions of the dental environment?”).

Study Characteristics (Tables 1 and 2)

Table 1.

Summary of descriptive characteristics of included articles that evaluated the dentist’s attire preferences (n = 20)

| Group | Author, year | Study sample (n), sex, and age (years) | Objectives | Setting | Statistical analysis | Findings | Main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture-based survey and questionnaire | AlSarheed12 Saudi Arabia | (583), 289 females, 294 males, 9–12 | To assess schoolchildren’s feelings and attitudes toward their dentist. | Eight primary public schools | Descriptive analysis. Chi-square test and non-parametric test. | 90% of the children preferred their dentist to wear a white coat instead of a colored one, while 40% preferred them to wear a mask and protective eyeglasses as protective measures during treatment. | The results indicated that children prefer their dentist to wear traditional formal attire with a white coat in the dental clinic. |

| Asokan et al.,25 India | (1,155), 709 females, 446 males, 9–12 | To analyze the association between anxious states of children about dentists and their preference for dentist attire and gender in the dental office. | Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry | Chi-square test. | Of all anxious children, 502 (69.9%) had a preference for colored attires and 408 (66.8%) preferred dentists with protective wear. | The use of child-friendly colors in attires may help in relieving dental anxiety and aid in better communication. | |

| Kamavaram Ellore et al.,13 India | (150), 75 females, 75 males, 9–13 | To evaluate children and parental perceptions and preferences toward dentist attire. | Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry | Pearson Chi-square analysis. | The majority (70%) of the children in this study preferred their dentist’s wearing traditional white coat attire. 30% preferred the non-white coat attires for their dentist to wear. 12% of the children preferred child-friendly attire and 9% preferred formal attire. | The authors found that traditional white coat attire is most preferred by children. | |

| Kuscu et al.,14 Turkey | (827), 407 females, 420 males, 9–14 | To assess children’s preferences for each of four different kinds of dental attire and to consider the relationship between children’s preferences and levels of dental anxiety. | Two elementary schools | ANOVA, Tukey HSD, and Chi-square test. | Formal attire was the first preference for 45.6% of the children (n = 377), followed by child-friendly attire with a preferred rate of 30.5% (n = 144). Informal attire was the preferred least (43%, n = 356). There was no statistically significant difference in anxiety scores between groups. | Children were observed to prefer formal attire more than other attires. However, the concept of “child-friendly” attire might be more appropriated for anxious children to enhance easy first communication. The popular view that children are fearful of white coats was not supported. | |

| Mistry and Tahmassebi,26 England | (100), 54 females, 46 males, 4–16 | To assess children and parents attitudes toward dental attire | Pediatric Department | Pearson Chi-squared analysis. | The most popular mode of attire was the female dental student with a white coat and mask (15.5%), followed by the male dental student in a white coat and mask (11.0%). The least favored were the female in the white coat and visor (1%) and male in the pediatric coat (1.5%). The results showed that overall only 5.5% of participants preferred the pediatric coat. | Children significantly preferred dental students in casual attire. Both children and parents similarly ranked formal white coats in favor of a pediatric coat. | |

| Molinari,27 USA | (52), 3–12 | To evaluate the perceptions of pediatric patients regarding the use of personal protective equipment by dentists. | Dental School Clinic | Descriptive analysis. | The majority (60%) of the children preferred dentist C (Dentist was wearing masks, gloves, and eyewear). Eighteen (35%) preferred dentist A (formal clothes) and 12 (23%) preferred dentist B (dentists without PPE). | It appears that the majority of pediatric dental patients are generally comfortable with the use of personal protective equipment by dentists. | |

| Nirmala et al.,28 India | (1,008), 405 females and 603 males, 9–14 | To evaluate preferences of dentist’s attire and gender by anxious and non-anxious children in India. | 15 public schools | Pearson’s test and Chi-square analysis. | The attire mostly preferred by anxious children was the female dentist in formal attire (19%), followed by the female dentist in a white coat (16%) and the female dentist in a white coat with glasses (16%). The least favored was the male dentist in the pediatric coat (0.4%), which was the least-preferred choice for non-anxious children as well. Only 1% of children preferred the pediatric coat. | Formal attire might be more appropriate for anxious children. | |

| Panda et al.,15 India | (619), 297 females, 322 males, 6–14 | To assess schoolchildren’s perceptions and preferences toward the dentist’s attire to understand their psych and promote a successful relationship with the patient. | Public Schools | Descriptive analysis and Chi-square test. | The study found that the majority of children preferred dental professionals to wear traditional formal attire with a white coat and name badge. They preferred the use of plain masks and white gloves but disliked protective eyewear or head caps. | The results obtained from this study can help dentists decide what is appropriate to wear while dealing with children to minimize their anxiety and improve the delivery of health care | |

| Patır Münevveroğlu et al.,10 Turkey | (200), 98 females, 102 boys, 6–12 | To evaluate the attitudes of children toward dentists and preferences. | Department of Pedodontics | Descriptive analysis. Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, and Student’s test. | 76.5% preferred their dentist to wear a colored coat instead of a white one. 20% preferred their dentist not to wear protective equipment. | Children have strong preferences regarding the appearance of their dentist and dental clinics. | |

| The majority of children preferred their dentist to wear a colored coat instead of a white one. | |||||||

| Ravikumar et al.,8 India | (534), 264 females, 270 males, 6–11 | To determine the preference of children toward dentists’ attire based on various age groups | Dental School Clinic | Descriptive analysis. Chi-square test. | Of the total 41.1% of boys preferred white coat whereas only 31.8% of girls preferred the same. The preference level for surgical scrubs was high among girls (41.2%) and only 31.4% of boys preferred surgical scrubs. 27.4% of boys and 26.8% of girls preferred a regular outfit. | Younger age group children preferred their dentist to wear a regular outfit and middle and older age groups preferred their dentist to wear a white coat and surgical scrubs. The white coat was the preference of choice by most of the children in a school environment but their preference level toward surgical scrubs was high in the dental environment. | |

| Souza-Constantino et al.,33 Brazil | (120) 8–11, (120) 12–17 | To investigate whether patients in different age groups are influenced by the age, sex, and attire of an orthodontist. | Dental School Clinic | Descriptive statistics. | A white coat was the preferred attire (48.1%), followed by social clothing (31.7%), and a thematic pediatric coat (19.7%). | The participants largely preferred younger professionals who dressed in white coats, because this type of attire was considered clean and hygienic. | |

| Subramanian and Rajasekaran,29 India | (100), 9–12 | To assess children’s attitudes and perceptions toward their dentist. | Dental Hospital | Descriptive statistics. | The results showed that 72% of the children preferred their dentist to wear a color dress instead of a white coat. When asked to choose between two pictures of different clinical settings, 83% of the children indicated that they preferred a decorated dental clinic over a plain clinic. | Children have strong perceptions and preferences regarding their dentists. Data collected for this study can be used by dentists to improve the delivery of care. | |

| Tong et al.,30 Singapore | (402), 180 females, 222 males, 5–7 | To evaluate the child and parental attitudes toward dentists’ appearance, subsequently related to a child’s dental experience and their association with a child’s anxiety levels. | School Dental Service | Descriptive analysis, Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis, and Spearman’s correlation tests. | Personal protective equipment (PPE) was the attire of choice for both parents and children, followed by the pediatric coat. Formal and informal attire was least preferred by children and parents, respectively. | Regardless of child anxiety levels, the PPE followed by pediatric coats were preferred over other choices of dentists’ attire. | |

| Westphal et al.31 USA | (97), 9–14 | To understand guardian and child preferences for the appearance of their pediatric dentist. | Pediatric Dental Clinic | Descriptive statistics. | For pediatric patients, scrubs were still, most often selected, but at a lower rate (43%). White coat remained the second most preferred option at 37%. | The authors concluded that those scrubs were the most preferred attire chosen by the child for their dentist. | |

| Questionnaire-based survey | Bahammam,34 Saudi Arabia | (202), 9–12 | To assess the preferences of children regarding dentist attire in Al-Madinah Munawarah. | University Hospital | Descriptive statistics, one-way ANOVA. | The majority of the children (49.5%) preferred that dentists wore a white coat with a white scarf. | There is a significant impact of dentist attire on the child’s acceptance of the dental procedure. |

| Jayakaran et al.,24 India | (50), 21 females, 29 males, 6–10 | To determine children’s preferences in a dental clinic to reduce anxiety during dental procedures. | Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test. | 78% preferred white coat and 22% colored coat. | The results will help the dental team decide on appropriate design/dentist attire. | |

| Yahyaoglu et al.,32 Turkey | (810), 402 females, 408 males, 6–12 | To determine the prevalence of dental fear, the relationship between dental fear and dental caries and the dentist appearance most likely to reduce anxiety among children. | Department of Pediatric Dentistry | Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis, and Spearman | Patients who preferred their dentist to wear a colorful uniform were found to have significantly greater CFSS-DS scores than those who preferred the more traditional white coat attire. | Anxious children demonstrated a preference for their physicians’ external appearance. | |

| Picture-based survey | Babaji et al.,35 India | (750), 4–14 | To evaluate the preference of the dentist’s attire and kind of syringe (conventional or camouflage) among different age groups of children. | Dental College | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test. | The authors observed that the preference of colored attire of dentists among younger children over the older ones. | Younger children prefer the colorful attire of a dentist and camouflage syringe over the conventional one. |

| Children’s anxiety level decreases with age and preference for the white coat and conventional syringe increases. | |||||||

| Cohen,16 USA | (300), 2–16 | To assess children’s attitudes toward the dentist’s attire. | Dental Department of Children’s Hospital | Chi-square test. | There was no significant difference between the entire groups (white jacket, shirt and tie, clinic gown). | The data collected indicate that the dress of the dentist probably has more effect on the dentist than on the child patient. | |

| Medrano García and Castillo Cevallos,17, Peru | (100), 3–14 | To determine preference for the dentist attire by children and their parents. | Dental School Clinic | Chi-square test. | The most preferred dentist attire by children was child-friendly attire (44%) and white coat (37.5%). The least preferred dentist attire by children was informal attire (56%), followed by casual attire. | The most preferred dentist attire by children for man was a white coat and for a woman was child-friendly attire. | |

| The group of children age 11–14 years preferred white coat and casual attires. |

Table 2.

Summary of descriptive characteristics of included articles that evaluated dental clinic preferences (n = 5)

| Group | Author, year | Study sample (n), sex, and mean age (years) | Objectives | Setting | Statistical analysis | Findings | Main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Picture-based survey and questionnaire | Patır Münevveroğlu et al.,10 Turkey | (200), 98 females, 102 boys, 6–12 | To evaluate the attitudes of children toward dentists and preferences. | Department of Pedodontics | Descriptive analysis. Chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, and Student’s test. | When the children were asked to choose between pictures of undecorated and decorated dental clinics as the clinic they would like to be treated in, 76.5% selected the decorated dental clinic. However, there was no significant difference between age groups (p < 0.05). | Children have strong preferences regarding the appearance of their dentist and dental clinics. |

| Subramanian and Rajasekaran29 India | (100), 9–12 | To assess children’s attitudes and perceptions toward their dentist. | Dental Hospital | Descriptive statistics. | When asked to choose between two pictures of different clinical settings, 83% of the children indicated that they preferred a decorated dental clinic over a plain clinic. | Children have strong perceptions and preferences regarding their dentists. Data collected for this study can be used by dentists to improve the delivery of care. | |

| Questionnaire-based survey | Jayakaran et al.,24 India | (50), 21 females, 29 males, 6–10 | To determine children’s preferences in a dental clinic to reduce anxiety during dental procedures. | Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry | Chi-square test. | A large number of children preferred listening to rhymes and watching cartoons while undergoing dental treatment. They also preferred the walls painted with cartoons, the dental chair full of toys, a scented environment. | A blue wall, with cartoon background, filled with toys, in a scented atmosphere, with rhymes, played in the background, with cartoon videos. |

| Panda and Shah,23 India | (212), 85 females, 127 males, 6–11 | To determine children’s preferences regarding the dental waiting area so as to improve their waiting experience and reduce their preoperative anxiety before a dental appointment. | Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry | Cross-tables using Phi (for 2 9 2 tables) or Cramer’s V (for larger than 2 9 2 tables). | A majority of children preferred music and the ability to play in a waiting room. They also preferred natural light and walls with pictures. They preferred looking at an aquarium or television and sitting on beanbags and chairs and also preferred plants and oral hygiene posters. | Children do have strong preferences related to the dental waiting area. Introducing distractions that children prefer in the dental waiting area, such as books, music, aquarium, etc., can help relax them and can reduce anxiety related to the upcoming dental visit. | |

| Picture-based survey | AlSarheed,12 Saudi Arabia | (583), 289 females, 294 males, 9–12 | To assess school children’s feelings and attitudes toward their dentist. | Eight primary public schools | Descriptive analysis. Chi-square test and non-parametric test. | 63% of the children indicated that they preferred a decorated dental clinic over a plain clinic instead of a colored one. However, this preference differed between age groups, 37% of young children (9–10 years) liked the decorated dental clinic compared to 15% of the older age group (10–12 years). | The results indicated the children favored a decorated dental clinic with the toys and posters over a routine and bare clinic. |

All the included studies had a descriptive design. Regarding the origin, the selected studies were nine from India,8,13,15,23–25,28,29,35 three from Turkey,10,14,32 three from the USA,16,27,31 one from England,26 two from Saudi Arabia,12,34 one from Singapore,30 one from Peru,17 and one from Brazil.33 Sample size ranged extensively from 5024 to 1,155 subjects.25 From the 21 included studies, 20 were retained to attend to question 1 using the following methodologies: picture-based survey and questionnaire,8,10,12–15,23,25–30,33 questionnaire-based survey,24,32,34 and picture-based survey.16,17,35 Five studies were retained to address question 2 reported the children’s perceptions of the dental environment and the following methodologies were adopted: picture-based survey and questionnaire,10,29 questionnaire-based survey,23,24 and picture-based survey.12

Table 1 shows a study descriptive summary from the 20 studies selected for question 1. Table 2 shows the five-study characteristics to answer question 2.

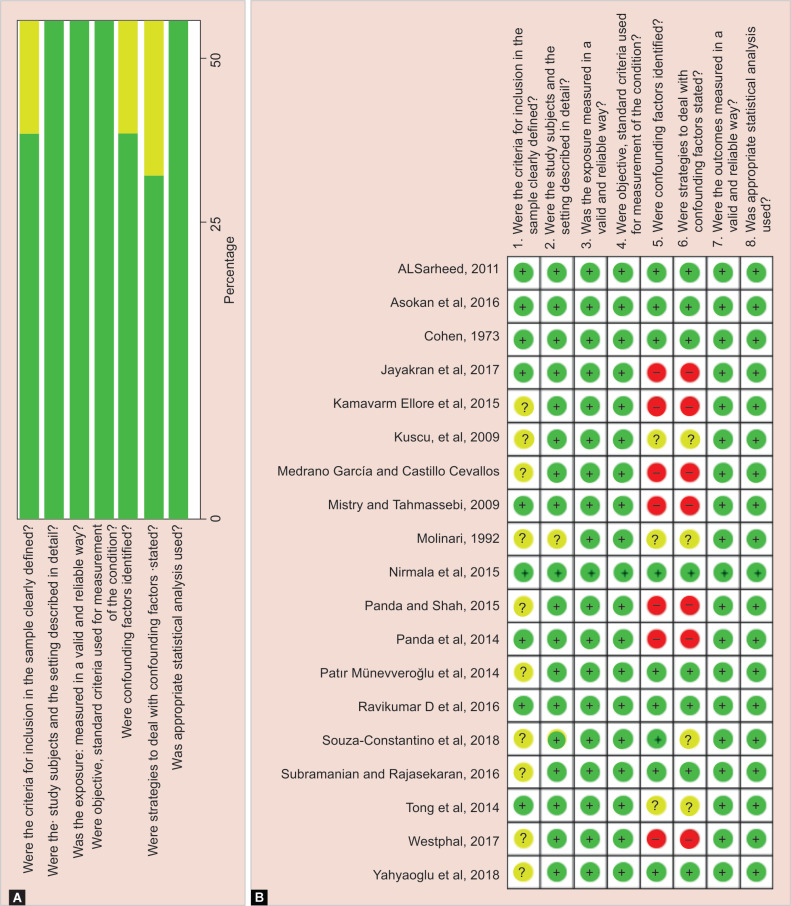

Risk of Bias within Studies (Fig. 1)

Figs 1A and B.

(A) Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies; (B) Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study

The majority of the included studies for question 1 (13 studies) had a low risk of bias, six moderate risks, and only two high risks. Question two studies were more homogeneous, with five bias low risk, and one moderate risk. Figure 1 provides more summarized assessment bias risk information. Appendix 3 shows a more detailed assessment.

Results of Individual Studies (Tables 1 and 2)

The characteristics of studies selected to answer question one are reported in Table 1, while the characteristics of the studies selected to answer question two are synthesized in Table 2. The children’s perceptions of the dentist’s attire studies indicated that children prefer their dentist to wear traditional formal attire with a white coat.12–15,24,26,28,33,34 On the contrary, some authors10,17,29,30,32 reported children’s preference for the colored coat. Asokan et al.25 and Yahyaoglu et al.32 found that child-friendly color attires may assist in dental anxiety control and improve communication.

Cohen16 concluded that there was no significant difference between entire groups (white jacket, shirt and tie, clinic gown).

Westphal et al.31 and Ravikumar et al.8 found that scrubs were the most preferred option. According to Molinari,27 it appears that the majority of pediatric patients are generally comfortable with the use of personal protective equipment by dentists.

Considering the five studies that addressed the children’s perceptions of the dental environment, Subramanian and Rajasekaran29 reported that 83% of the children indicated that they preferred a decorated dental clinic to a plain one. Panda and Shah23 reported that children’s favorite distractions in the dental waiting area can reduce anxiety regarding the dental visit. Jayakaran et al.24 concluded that children preferred the walls painted with cartoons, the dental chair full of toys, and a scented environment. AlSarheed12 observed that young children (9–10 years) liked the decorated dental clinic compared with 15% of the older age group (11–12 years). Differently, Patir Münevveroğlu et al.10 found that there was no significant difference between the age groups regarding the appearance of dental clinics.

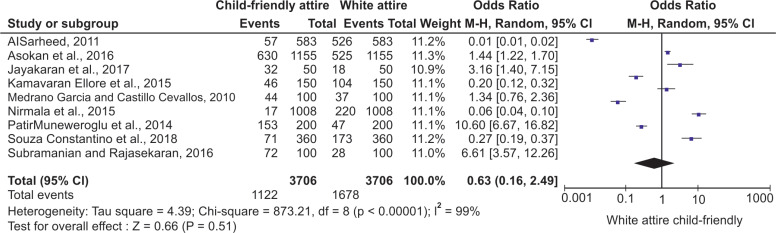

Synthesis of Results (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for children’s attire preferences

The meta-analysis was performed in two steps:

To answer question 1, the selected studies were grouped and a meta-analysis was performed. The results from this meta-analysis showed that there is no difference when compared white coat vs child-friendly attire (OR = 0.63; 95% CI 0.16–2.49; n = 3,706) (Fig. 2).

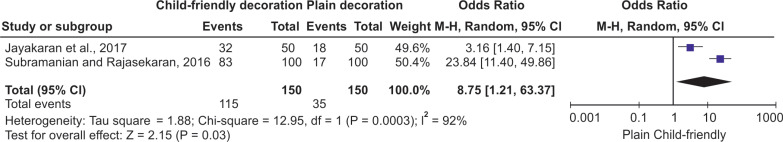

To answer question 2, the two included in the meta-analysis24,29 that directly presented results regarding the decorated dental clinic and plain clinic were included in the quantitative synthesis. The decorated clinic proved to be the majority of children’s preference (OR = 8.75; 95% CI 1.21–63.37; n = 150) (Fig. 3). The heterogeneity between the studies found in the meta-analysis was high. The decorated clinic was the majority of children’s preference.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for children’s dental clinic preferences

Risk of Bias Across Studies and Confidence in Cumulative Evidence

Although the studies had the same study design the main methodological limitation is the sample size. Most of the included studies used a convenience sample that does not represent the general population. Due to the research preference questions nature, the included studies observational design, and the expected high heterogeneity among the compared studies, the confidence assessment in cumulative evidence using GRADE criteria36 was considered unreliable. However, if applicable, the initial grade of overall evidence was low due to included studies observational design.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review has evaluated the children’s perception and preferences regarding the dentist’s attire and environment. The patient’s first impression of a health professional may strongly influence the care perception provided and personal attributes of the dentists, as well.12,18,28 Understanding the children’s perception realm may be of utmost importance to guarantee a successful dentist–patient relationship. Reducing negative image impact toward the dentist’s attributed rapport along with the dental environment will certainly prevent other children’s negative impressions.12

The scientific literature has shown a great variation in the children’s perception of their dentist’s attire and it has been hypothesized that children are afraid of doctors who wear a white coat, which according to another report it could impair doctor–patient confidence.37 In addition, it was expected that a child-friendly suit might contribute to pediatric dentist’s empathy. Surprisingly, the majority of the included studies in this systematic review reported that white coat attire was the most preferred by children.12–15,24,26,28,33,34 Other studies have concluded that children are inclined to be more comfortable with a dentist in a friendly or causal child-like attire.10,16,17,25,32 Using a meta-analysis we meant to increase the sample size by grouping the results of the primary studies included in the review to elucidate whether there is a difference between the attires tested. Our meta-analysis showed that there is no difference when compared with white coat vs child-friendly attire.

A previous systematic review carried out in adults has reported that although patients often prefer formal physician attire (with or without a white coat), this perception is complex and multifactorial.18 We believe that it is essential to evaluate the children’s preferences according to their age group. However, few studies have compared children’s preferences in different age groups, thus a subgroup analysis was not possible. Concerning the preferences and the possible association with the child’s age, it was verified that there is a tendency of older children to prefer the white coat attire and a plain clinic and the younger ones prefer the child-friendly attire. Ravikumar et al.,8 Kuscu et al.,14 and Babaji et al.35 have concluded that older children preferred the traditional white coat more than the younger ones. This result might be expressing a learned observed children’s response rather than demonstrating a personal preference. A feasible explanation may be related to the effects of age on learned preferences, and how young/old (age) children do start developing learning preferences. During the first 8 years, children develop their visual acuity.38

Kuscu et al.14 reported that 9 years is a cut-off age for scientific and social development when the child is more inquisitive. They have also stated that older children’s preference for the traditional white coat may have been a learned observation from other children than a personal preference or even from pediatricians and family doctors from an early age. The children’s dental environment perception has pointed out to the decorated clinic than the plain one. This result is also in line with the previous studies23,24,29 and the findings may help the dentists and dental team decide the appropriate design of the pediatric dental clinic, including the waiting room and dental settings to provide a more comfortable dental environment. However, it is crucial to mention that perceptions of children and adolescents may be different. A previous study has shown that the younger age group liked the decorated dental clinic and a lower preference was observed in the older age group.12 AlSarheed12 verified that 63% of the children would choose the decorated dental clinic. This preference also differed significantly between age groups as only 37% of participants from the younger age group liked the decorated dental clinic compared with 15% of the older age group. It is essential to emphasize that there is an age group overlap in primary studies, impairing different age groups’ data. According to the literature, an attractive physical dental environment specially decorated for children can build up their positive attitude toward the upcoming dental visit.

Some of our included studies have evaluated and compared the child’s preferences and their anxiety levels. Asokan et al.25 reported that anxiety levels play an important role in children’s preferences. Anxious children preferred colored attires while not anxious ones preferred conventional attires. It is believed that a pleasant and colorful environment relieves the children’s anxiety. The authors have also pointed out that a child who has not undergone dental/medical experience prefers the dentist’s colored attires. The use of child-friendly colors in attires may help in relieving dental anxiety and aid in better communication.14,25

Anxiety levels along with a child’s age may be related concerning the perception of the dental environment and it is essential to elucidate in which way these dental surroundings can trigger children’s anxiety. According to the literature, younger children presented more negative perceptions of dentists than older children once younger ones could not satisfactorily comply. The majority of the children aged 6–12 years have reported a positive perception of the dentist.9 The ability to comply with the dental treatment increases with the age.39 Children’s responses to the dental environment are diverse and complex. It is important to mention that children show different behavior depending on age, behavioral maturity, experience, family backgrounds, culture, and health status.38 Syringes, needles, and high- and low-speed motors may provide a negative perception of the dentist. A gradual children exposure to the dental environment in sequential different nature visits decreased dental anxiety.40

Moreover, some authors have also highlighted that introducing amusement, such as, books, music, aquarium, and toys in the dental waiting area can help children relax as well as reduce anxiety concerning the following visits.23,32 Future randomized controlled trials could explore these findings by assessing the impact of decorating or plain dental clinic on children’s level of anxiety and satisfaction with dental treatment.

In addition, some studies have verified that children’s perceptions were influenced by gender. AlSarheed12 has reported that more girls than boys preferred the colored coat instead of a white coat. It is important to point out that the majority of the included studies have not considered preference according to gender, thus meta-analysis was not possible. Most of our review selected studies presented a low bias risk. However, it is essential to highlight the great variation of the dental environment characteristics. An appropriate eligibility criterion was used to minimize bias and obtain study homogeneity.

Our systematic review has some limitations that should be considered while interpreting the findings of the studies reviewed. All included studies were cross-sectional descriptive studies and the sample size ranged from 5024 to 1,155 subjects.25 Small size and convenience samples may impair statistics. These points may explain the high heterogeneity in the results. Despite this, we have attempted to reduce potential biases and minimize errors by adopting the random effect model in our meta-analysis. Moreover, due to high methodological heterogeneity in the included studies regarding sample size, different countries, and children’s age, the statistical results also presented high heterogeneity. This means that the results should be considered with caution. Further high-quality studies are required to verify the conclusion.

Future studies demand a sample with different age groups to test the influence of age groups in the preference of dental attires. Furthermore, other confounding factors, such as, gender, levels of anxiety, child’s personality, medical/dentist past experiences, and socioeconomic backgrounds, should be considered for a better understanding of the children’s perceptions or preferences.

Cultural aspects should also be sought for in future studies. The majority of the included studies in this systematic review were conducted in Asia. The selected studies were nine from India8,13,15,23–25,28,29,35 and three from Turkey.10,14,32 As Asia is a continent with different traditions in comparison with other parts of the world, the heterogeneity of the children population should be considered as every continent has its specific culture. Petrilli et al.18 have verified the influence of geography on attire preferences. Geography can influence attire perceptions due to cultural, fashion, or ethnic expectations. According to Tong et al.,30 the effect of ethnicity on patient’s perception of the appearance of their healthcare professional is not well established. Future methodologically more rigorous studies to evaluate the global children’s perception of the dentist’s attire and preferences related to their dental environments are encouraged to improve children’s satisfaction.

CONCLUSION

Based on available evidence, it was concluded that there is no difference in the children’s perception considering white coat vs child-friendly attire. Children prefer a decorated dental clinic over a plain.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Understanding children’s perceptions regarding the dentist’s attributes and the dental environment are essential for a successful dentist–patient relationship.

Appendix 1: Database search strategy

| Database | Search 6th December 2018 - updated on 12th December 2019 |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((“Patient Satisfaction”[Mesh] OR “Patient Preference”[Mesh] OR “personal satisfaction”[MeSH Terms] OR “satisfaction”[All Fields] OR “satisfactions”[All Fields] OR “preferences”[All Fields] OR “preference”[All Fields] OR “perception”[MeSH Terms] OR “perception”[All Fields] OR “perceptions”[All Fields] OR “Visual Perception”[Mesh] OR “Form Perception”[Mesh] OR “Trust”[Mesh] OR “Trust”[All Fields] OR “Interpersonal Relations”[Mesh] OR “Interpersonal Relations”[All Fields] OR “Professional-Patient Relations”[Mesh] OR “Professional-Patient Relations”[All Fields] OR “confidence”[All Fields] OR “Patient Comfort”[Mesh] OR “Comfort”[All Fields] OR “friendly”[All Fields] OR “Empathy”[Mesh] OR “Empathy”[All Fields] OR “caring”[All Fields] OR “compassion”[All Fields] OR “sympathy”[All Fields] OR “Happiness”[Mesh] OR “Happiness”[All Fields] OR “Emotions”[Mesh] OR “Emotions”[All Fields] OR “Emotion”[All Fields] OR “feelings”[All Fields] OR “feeling”[All Fields] OR “Pleasure”[Mesh] OR “Pleasure”[All Fields] OR “Sensation”[Mesh] OR “Sensation”[All Fields] OR “Sensations”[All Fields]) AND (“environment”[All Fields] OR “waiting room”[All Fields] OR “attire”[All Fields] OR “attires”[All Fields] OR “clothes”[All Fields] OR “clothing”[All Fields] OR “white coat”[All Fields] OR “scrubs”[All Fields] OR “dress”[All Fields] OR “dresses”[All Fields] OR “necktie”[All Fields] OR “appearance”[All Fields] OR “appearances”[All Fields] OR “colour”[All Fields] OR “color”[All Fields] OR “colors”[All Fields] OR “colorful”[All Fields] OR “colourful”[All Fields] OR “ambience”[All Fields] OR “settings”[All Fields] OR “child friendly colors”[All Fields])) AND (“child”[MeSH Terms] OR “child”[Title/Abstract] OR “children”[Title/Abstract] OR “childhood”[Title/Abstract] OR “child, preschool”[MeSH Terms] OR “preschool”[All Fields] OR “preschools”[All Fields] OR “Infant”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Infant”[All Fields] OR “Infants”[All Fields] OR “pediatrics”[MeSH Terms] OR “pediatrics”[Title/Abstract] OR “pediatric”[Title/Abstract] OR “paediatrics”[Title/Abstract] OR “paediatric”[Title/Abstract])) AND (((“dental”[Title/Abstract] OR “dentistry”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“visit”[All Fields] OR “visits”[All Fields] OR “treatment”[All Fields] OR “treatments”[All Fields])) OR “Dental Care”[Mesh:noexp] OR “Dental Care”[All Fields] OR “Dental Care for Children”[Mesh] OR “Dental Offices”[Mesh] OR “Dental Offices”[All Fields] OR “Dental Office”[All Fields] OR “Pediatric Dentistry”[Mesh] OR “Pediatric Dentistry”[All Fields] OR “Paediatric Dentistry”[All Fields] OR “Dental Service, Hospital”[Mesh] OR “Hospital Dental Services”[All Fields] OR “Hospital Dental Services”[All Fields]) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

| Cochrane | (“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND (“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND (((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

| Web of Science | (“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND (“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND (((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

| LILACS | (tw:(“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations” OR “satisfação” OR “satisfações” OR preferência* OR “percepção” OR “percepções” OR “Confiança” OR “Relações Interpessoais” OR “Relações Profissional-Paciente” OR “Conforto” OR “amigável” OR “empatia” OR “carinho” OR “simpatia” OR felicidad* OR “emoções” OR “emoção” OR “sentimentos” OR “sentimento” OR “prazer” OR “sensação” OR “sensações” OR “satisfacción” OR “satisfacciones” OR percepción* OR “Confianza” OR “Relaciones Interpersonales” OR “Relaciones Profesional-Paciente” OR “confianza” OR “Confort” OR “simpatía” OR emocion* OR “sentimientos” OR “sentimiento” OR “Placer” OR sensacion* )) AND (tw:(“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors” OR “ambiente” OR “sala de espera” OR vestuário* OR roupa* OR “avental” OR “aparência” OR “cor” OR “cores” OR colorid* OR “ambiente” OR atuendo* OR ropa* OR bata* OR apariencia* OR “colores” )) AND (tw:(“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric” OR criança* OR “infância” OR “pré escolar” OR “pré escolares” OR lactente* OR “pediatria” OR pediátric* OR niño* OR “preescolar” OR “preescolares” OR infante* )) AND (tw:(((“dentistry” OR odontologia OR denta*) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments” OR “visita” OR “visitas” OR tratamento* OR tratamiento*)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Assistência Odontológica” OR “Consultórios Odontológicos” OR “Consultório Odontológico” OR “Serviços Odontologicos Hospitalares” OR “Serviço Odontologico Hospitalar” OR “atención dental” OR “servicios dentales” OR “Servicios Dentales Hospitalarios” OR “Servicio Dental Hospitalar”)) AND (instance:”regional”) AND ( db:(“LILACS”)) |

| PsycINFO | (“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND (“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND (((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

| Google Scholar | (“perception” OR “perceptions” OR “preferences” OR “preference”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “childhood”) AND (“dental visit”) |

| OpenGrey | (“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND (“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND (((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

| ProQuest | noft(“satisfaction” OR “satisfactions” OR “preferences” OR “preference” OR “perception” OR “perceptions” OR “Trust” OR “Interpersonal Relations” OR “Professional-Patient Relations” OR “confidence” OR “Comfort” OR “friendly” OR “Empathy” OR “caring” OR “compassion” OR “sympathy” OR “Happiness” OR “Emotions” OR “Emotion” OR “feelings” OR “feeling” OR “Pleasure” OR “Sensation” OR “Sensations”) AND noft(“environment” OR “waiting room” OR “attire” OR “attires” OR “clothes” OR “clothing” OR “white coat” OR “scrubs” OR “dress” OR “dresses” OR “necktie” OR “appearance” OR “appearances” OR “colour” OR “color” OR “colors” OR “colorful” OR “colourful” OR “ambience” OR “settings” OR “child friendly colors”) AND noft(“child” OR “children” OR “childhood” OR “preschool” OR “preschools” OR “Infant” OR “Infants” OR “pediatrics” OR “pediatric” OR “paediatrics” OR “paediatric”) AND noft(((“dental” OR “dentistry”) AND (“visit” OR “visits” OR “treatment” OR “treatments”)) OR “Dental Care” OR “Dental Offices” OR “Dental Office” OR “Pediatric Dentistry” OR “Paediatric Dentistry” OR “Hospital Dental Services” OR “Hospital Dental Services”) |

Appendix 2: Excluded articles and reasons for exclusion

| Author, Year | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Annamary et al. 20161 | 1 |

| Bubna et al. 20172 | 1 |

| Daniel et al. 20083 | 1 |

| Fox, Newton, 20064 | 1 |

| Fraiz, Macedo 20015 | 1 |

| Hass et al. 20166 | 1 |

| Ishikawa et al. 19847 | 1 |

| Karmakar et al. 20198 | 1 |

| Kominek, Rozkovcová, 19689 | 1 |

| Ozdas et al. 201710 | 1 |

| Pandiyan, Hedge 201711 | 4 |

| Pati, Nanda 201112 | 1 |

| Swallow et al. 197513 | 1 |

| Umamaheshwari et al. 201314 | 1 |

| Wali et al. 201615 | 3 |

| Welly et al. 201216 | 1 |

| Winer, 198217 | 2 |

Legend: 1—Studies with different objectives (n = 14), 2—Review (n = 1), 3—Studies that evaluate dentists’ perceptions (n = 1), 4—Studies that evaluate parents’ perceptions (n = 1)

Appendix 3: Risk of bias assessed by meta-analysis of statistics assessment and review instrument (MAStARI) critical appraisal tools. Risk of bias was categorized as high when the study reaches up to 49% score “yes”, moderate when the study reached 50% to 69% score “yes”, and low when the study reached more than 70% score “yes”

| (Question Analytical Cross-sectional Studies) | AlSarheed, 201112 | Asokan et al, 201626 | Babaji et al, 201836 | Bahammam, 201935 | Cohen, 197316 | Jayakaran et al, 201719 | Kamavaram Ellore et al, 201513 | Kuscu, et al, 200914 | Medrano Garcia and Castillo Cevallos, 201017 | Mistry and Tahmassebi, 200927 | Molinari, 199228 | Nirmala et al, 201529 | Panda et al, 201415 | Panda and Shah, 201518 | Patır Münevveroğlu et al, 201410 | Ravikumar et al, 20168 | Souza-Constantino et al, 201834 | Subramanian and Rajasekaran, 201630 | Tong et al, 201431 | Westphal, 201732 | Yahyaoglu et al, 201833 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | U | Y | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | U | U | Y | U | U |

| 2. Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 4. Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5. Were confounding factors identified? | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | N | U | N | N | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y |

| 6. Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | N | U | N | N | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | U | Y | U | N | Y |

| 7. Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 8. Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| %Yes/Risk | 100 | 100 | 42.8 | 57.1 | 100 | 71.4 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 71.4 | 42.8 | 100 | 71.4 | 57.1 | 85.7 | 100 | 57.1 | 85.7 | 71.4 | 57.1 | 85.7 |

| Overall | low | low | high | mod | low | low | mod | mod | mod | low | high | low | low | mod | low | low | mod | low | low | mod | low |

Y = Yes, N = No, U = Unclear, NA = Not applicable

Footnotes

Source of support: This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Finance Code 001.

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Porritt J, Buchanan H, Hall M, et al. Assessing children’s dental anxiety: a systematic review of current measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;;41((2):):130––142.. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00740.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asl AN, Shokravi M, Jamali Z, et al. Barriers and drawbacks of the assessment of dental fear, dental anxiety and dental phobia in children: a critical literature review. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;;41((6):):399––423.. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-41.6.1. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diercke K, Ollinger I, Bermejo JL, et al. Dental fear in children and adolescents: a comparison of forms of anxiety management practised by general and paediatric dentists. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;;22((1):):60––67.. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01158.x. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seligman LD, Hovey JD, Chacon K, et al. Dental anxiety: an understudied problem in youth. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;;55::25––40.. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.004. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nermo H, Willumsen T, Johnsen JK. Prevalence of dental anxiety and associations with oral health, psychological distress, avoidance and anticipated pain in adolescence: a cross-sectional study based on the Tromsø study, fit futures. Acta Odontol Scand. 2018;;77((2):):126––134.. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2018.1513558. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and dental anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dental J. 2013;;58((4):):390––407.. doi: 10.1111/adj.12118. DOI: quiz 531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cianetti S, Paglia L, Gatto R, et al. Evidence of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of dental fear in paediatric dentistry: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;;7((8):):e016043. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016043. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravikumar D, Gurunathan D, Karthikeyan S, et al. Age and environment determined children’s preference towards dentist attire – a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;;10((10):):ZC16––ZC19.. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/22566.8632. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frauches M, Monteiro L, Rodrigues S, et al. Association between children’s perceptions of the dentist and dental treatment and their oral health-related quality of life. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2018;;19((5):):321––329.. doi: 10.1007/s40368-018-0361-9. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patir Münevveroğlu A, Akgöl BB, Erol T. Assessment of the fellings and attitudes of children towards their dentist and their association with oral health. ISRN Dent. 2014;;2014::867234. doi: 10.1155/2014/867234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinknecht RA, Klepac RK, Alexander LD. Origins and characteristics of fear of dentistry. JADA. 1973;;86((4):):842––848.. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1973.0165. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AlSarheed M. Children’s perception of their dentists. Eur J Dent. 2011;;5((2):):186––190.. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698878. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamavaram Ellore VP, Mohammed M, Taranath M, et al. Children and parent’s attitude and preferences of dentist’s attire in pediatric dental practice. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2015;;8((2):):102––107.. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1293. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuscu OO, çaglar E, Kayabasoglu N, et al. Short communication: preferences of dentist’s attire in a group of Istanbul school children related with dental anxiety. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;;10((1):):38––41.. doi: 10.1007/BF03262666. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panda A, Garg I, Bhobe AP. Children’s perspective on the dentist’s attire. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014;;24((2):):98––103.. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12032. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen S. Children’s attitudes toward dentists’ attire. ASDC J Dent Child. 1973;;40((4):):285––287.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medrano García G, Castillo, Cevallos JL. Preference for the dentist attire by children and their parents. Odontol Pediatr. 2010;;9::150––162.. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, et al. Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature-targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open. 2015;;5((1):):e006578. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006578. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;;8((5):):336––341.. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;;5((1):):210.. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macaskill P, Gatsonis C, Deeks JJ, et al. Analysing and presenting results. In: Deeks JJ, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Version 5.1.0, ed.: Oxford, United Kingdom:: The Cochrane Collaboration;; 2010.. ch. 10, [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Collaboration,; 2011.. [Accessed October 25, 2019.]. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. ed., Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panda A, Shah M. Children’s preferences concerning ambiance of dental waiting rooms. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;;16((1):):27––33.. doi: 10.1007/s40368-014-0142-z. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jayakaran TG, Rekha CV, Annamalai S, et al. Preferences and choices of a child concerning the environment in a pediatric dental operatory. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2017;;14((3):):183––187.. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.208767. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asokan A, Kambalimath HV, Patil RU, et al. A survey of the dentist attire and gender preferences in dentally anxious children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;;34((1):):30––35.. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.175507. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mistry D, Tahmassebi JF. Children’s and parents’ attitudes towards dentists’ attire. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;;10((4):):237––240.. doi: 10.1007/BF03262689. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molinari GE. Pediatric dental patients’perceptions of personal protective equipment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1992;;20((10):):39––42.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nirmala SVSG, Veluru S, Nuvvula S, et al. Preferences of dentists’ attire by anxious and nonanxious Indian children. J Dent Child. 2015;;82((2):):97––101.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramanian P, Rajasekaran S. Children’s perception of their dentist. RJPBCS. 2016;;7::787––789.. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong HJ, Khong J, Ong C, et al. Children’s and parents’ attitudes towards dentists’ appearance, child dental experience and their relationship with dental anxiety. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;;15((6):):377––384.. doi: 10.1007/s40368-014-0126-z. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westphal J, Berry E, Carrico C, et al. Provider appearance: a survey of guardian and patient preference. J Dent Child. 2017;;84((3):):139––144.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yahyaoglu O, Baygin O, Yahyaoglu G, et al. Effect of dentists’ appearance related with dental fear and caries status in 6-12 years old children. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2018;;42((4):):262––268.. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-42.4.4. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Souza-Constantino AM, Cláudia de Castro Ferreira Conti A, Capelloza Filho L, et al. Patients’ preferences regarding age, sex, and attire of orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;;154((6):):829––834.. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2018.02.013. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahammam S. Children’s preferences toward dentist attire in al Madinah al Munawarah. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;;13::601––607.. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S196373. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babaji P, Chauhan P, Churasia VR, et al. A cross-sectional evaluation of children preference for dentist attire and syringe type in reduction of dental anxiety. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2018;;15((6):):391––396.. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.245228. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;;336((7650):):924––926.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. DOI: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazory A. Physicians, their appearance, and the white coat. Am J Med. 2008;;121((9):):825––828.. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.05.030. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohebbi SZ, Razeghi S, Gholami M, et al. Dental fear and its determinants in 7-11-year-old children in Tehran, Iran. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2019 Oct;20((5):):393––401.. doi: 10.1007/s40368-018-0407-z. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suprabha BS, Rao A, Choudhary S, et al. Child dental fear and behavior: the role of environment factors in a hospital cohort. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2011;;29::95––101.. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.84679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Menezes Abreu DM, Leal SC, Mulder J, et al. Patterns of dental anxiety in children after sequential dental visits. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2011 Dec;12((6):):298––302.. doi: 10.1007/BF03262827. DOI: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]