Abstract

Objectives

To gauge specific knowledge around clinical features, transmission pathways and prevention methods, and to identify factors associated with poor knowledge to help facilitate outbreak management in Syria during this rapid global rise of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Web-based cross-sectional survey.

Setting

This study was conducted in March 2020, nearly 10 years into the Syrian war crisis. The Arabic-language survey was posted on various social media platforms including WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and Facebook targeting various social groups.

Participants

A total of 4495 participants completed the survey. Participants with a history of COVID-19 infection, residing outside Syria or who did not fully complete the survey were excluded from the study. The final sample of 3586 participants (completion rate=79.8%) consisted of 2444 (68.2%) females and 1142 (31.8%) males.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

First, knowledge of COVID-19 in four areas (general knowledge; transmission pathways; signs and symptoms; prevention methods). Second, factors associated with poor knowledge.

Results

Of the 3586 participants, 2444 (68.2%) were female, 1822 (50.8%) were unemployed and 2839 (79.2%) were college educated. The study revealed good awareness regarding COVID-19 (mean 75.6%, SD ±9.4%). Multiple linear regression analysis correlated poor mean knowledge scores with male gender (β=−0.933, p=0.005), secondary school or lower education level (β=−3.782, p<0.001), non-healthcare occupation (β=−3.592, p<0.001), low economic status (β=−0.669, p<0.040) and >5 household members (β=−1.737, p<0.001).

Conclusion

This study revealed some potentially troubling knowledge gaps which underscore the need for a vigorous public education campaign in Syria. This campaign must reinforce the public’s awareness, knowledge and vigilance towards precautionary measures against COVID-19, and most importantly aid in controlling the worldwide spread of the disease.

Keywords: public health, COVID-19

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data are derived from a large, national survey across Syria, during the lockdown period.

The survey covered sociodemographic information, general knowledge, transmission, symptoms and prevention.

Results have broad implications for public health programming and response to COVID-19 in Syria.

This web-based cross-sectional study cannot be generalised towards the Syrian population.

Background

COVID-19 is a highly infectious respiratory disease that evolved into a worldwide pandemic, threatening a prolonged economic recession. The first incidence was reported at a local seafood market in Wuhan, China.1 The virus continues to spread, with steadily increasing morbidity and mortality cases, hitting the poorest and most vulnerable in the world. Many studies have assessed symptomatic clusters, transmission pathways and prevention methods; however, many aspects have yet to be studied.2 3

The battle against COVID-19 in Syria has just entered its third wave.4 5 The first confirmed case was announced on 22 March 2020,6 and there had only been 44 cases and 3 deaths at the time of the study. These figures are significantly lower than neighbouring countries such as Turkey (127 659 cases and 3461 deaths), Iran (98 647 and 6277), Iraq (2346 and 98), Lebanon (740 and 25), and Jordan (465 and 9).7 The Syrian healthcare system is severely underequipped and lacks the capacity to contain such a crisis. The estimated number of intensive care unit (ICU) beds with ventilators is a mere 325, and the theoretical maximum number of cases that can be adequately treated is only 6500.8 Once this maximum threshold (capacity) is exceeded, drastic rationing decisions will have to be made. Therefore, cooperation with and response to guidance from the WHO are of utmost importance. Unprecedented measures have been adopted to control the spread of COVID-19 in Syria.8 The public’s adherence to these control measures is largely affected by their awareness, knowledge, and attitudes towards disease and outbreaks.9 10

The Syrian conflict, now on its 10th year, has resulted in the worst refugee crisis since World War II.11 The devastating impact of war has placed the public health system under constant strain; the numbers of casualties continue to rise, 70% of healthcare workers (HCWs) have fled the country, the annihilation of healthcare facilities and the ‘weaponisation’ of healthcare are ongoing challenges.8 12 These challenges along with dense residential areas, the growing prevalence of chronic illness and 83% of the population living below the poverty line make Syria highly vulnerable to a severe outbreak.8 13

While some studies have been conducted to assess the knowledge, attitude and practices among populations during this pandemic, including one done in China, none have been undertaken in Syria.14–21 To our knowledge, this is the first study which aims to measure the awareness and general knowledge of COVID-19 among the Syrian population at a time where ambiguity and misinformation are rampant. The objective of this study is to gauge specific knowledge around clinical features, transmission pathways and prevention methods, and to identify factors associated with poor knowledge to help facilitate outbreak management in Syria during this rapid global rise of the COVID-19 pandemic. The information gleaned from this research will help with public health programming and response to COVID-19 in Syria as the pandemic continues to unfold.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

This web-based cross-sectional survey was conducted between 31 March and 4 April 2020, during the lockdown period. The inclusion criteria for this study were participants residing in Syria who completed the survey and had no known history of COVID-19 infection. The authors’ designed questions were modelled after existing awareness surveys, WHO course materials, technical briefs, and question-and-answer bank on COVID-19-related topics.14 15 22–25 Questions from existing awareness surveys that did not target community awareness regarding COVID-19 were excluded from the study.14 15 The survey was translated into Arabic and was reviewed by two dialectologists and two infectious disease specialists, who evaluated whether the survey questions effectively assessed COVID-19 knowledge, and checked for double-barrelled and confusing questions, to ascertain validity. We conducted a pilot study on 20 volunteers to assess reliability, clarity, relevance and the acceptability of the survey. These volunteers were excluded from the final sample to avoid bias. Modifications were made based on feedback received to facilitate better comprehension before distributing the final survey to the general population. The Arabic-language survey was posted on various social media platforms including WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and Facebook targeting various social groups. To avoid non-response bias, the survey was distributed during lockdown where the majority of the population were out of work and at home. GIFs and posts were adapted to appeal to each social group; the questions were made short and in the form of multiple choice questions that required no typing. The ability for viewers to comment on the link increased the popularity of the survey. Participants confirmed their voluntary participation by answering a yes–no question, were informed of the option to opt-out of the survey at any time, and were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. After confirmation, participants were directed to the first part of the survey to complete questions about sociodemographic information including age, gender, residence, education level, occupation and economic status. Participants under the age of 18 years required informed parental consent, as well as submission of parent/guardian contact information. The researchers were responsible for contacting the parents/guardians to obtain consent before the child was given access to the survey. The sample size calculated was 2401 participants based on a margin of error of 2%, and a CI of 95%, for a population of 18 284 423 people using a sample size calculator (website: https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm). The self-administered survey contained 40 questions divided into four sections: general knowledge (10 questions), transmission pathways (7 questions), clinical features (12 questions) and prevention methods (11 questions). The survey is available in online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjopen-2020-043305supp001.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

The public were not involved in the study design, conduct of the study or plans to disseminate the results to study participants.

Statistical analysis

A scoring system was used to analyse the participants’ knowledge: a score of ‘1’ was given for a correct answer and a score of ‘0’ was given for an incorrect answer. The correct answers to the survey were determined from previous surveys and available WHO resources.14 15 22–25 The percentage score for mean knowledge was calculated as follows: sum of scores obtained/maximum scores that could be obtained×100. Participants’ total mean knowledge in all the subsections, and mean knowledge of each subsection were calculated. Data were analysed using the SPSS V.25.0 and reported as frequencies and percentages (for categorical variables) or means and SDs (for continuous variables). The t-test was applied to compare mean knowledge scores against both genders, and three questions (knowing an infected individual, use of personal belongings and dissemination of knowledge). The t-test was applied to compare mean knowledge scores against gender. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied using f-test to compare mean knowledge scores against sociodemographic variables (age, social status, residence, education level, occupation, economic status and number of household members), and source of information. Multivariable linear regression analysis using the sociodemographic variables as independent variables (categorical) and mean knowledge score as the outcome variable (continuous) was conducted to identify factors associated with knowledge. Factors were selected with a backward method and were analysed using the unstandardised coefficient (β), and 95% CI. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

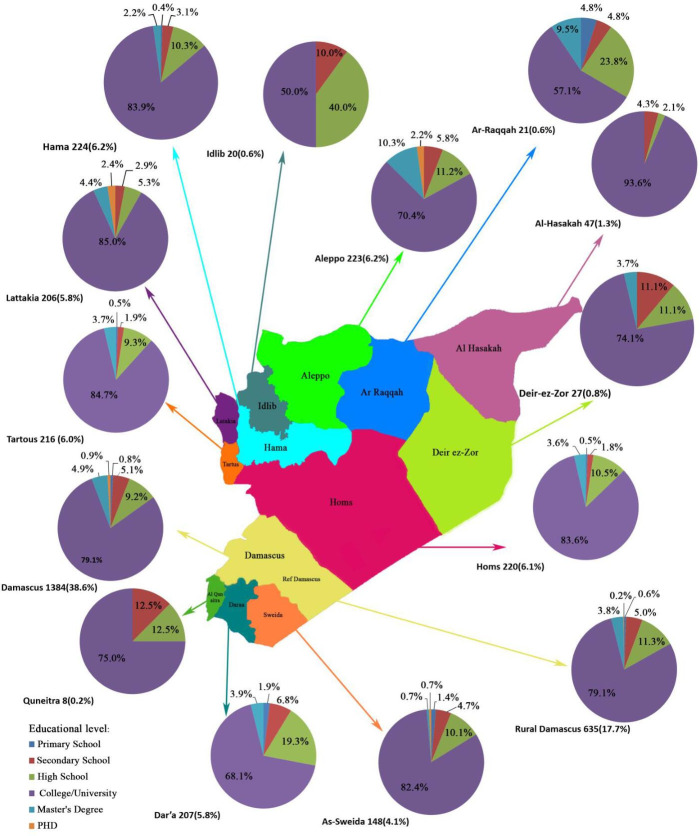

Of 4495 total participants who completed the survey, participants with a known history of COVID-19 infection, residing outside Syria and who did not fully complete the survey were excluded. The final sample of 3586 participants (completion rate=79.8%) consisted of 2444 (68.2%) females and 1142 (31.8%) males. Participants aged >20 years were the majority 1204 (33.6%), while participants between 35 and 39 years were the minority 186 (5.2%). Participant ages ranged from 12 to 78 years with a mean of 30 (±10) years. A total of 2279 (63.6%) participants were single, 1822 (50.8%) were unemployed, 1064 (29.7%) were smokers and 428 (11.9%) were alcohol consumers (table 1). The majority of participants were residents of Damascus/Rural Damascus 2019 (56.3%) and had attained college/university level education (figure 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics: (n=3586)

| Gender (%) | Male | 1142 (31.8) | Education (%) | Primary school | 25 (0.7) |

| Female | 2444 (68.2) | Intermediate school | 166 (4.6) | ||

| Age (%) | <20 | 1204 (33.6) | Secondary school | 375 (10.4) | |

| 20–24 | 1104 (30.8) | College/university | 2839 (79.2) | ||

| 25–29 | 446 (12.4) | Master’s degree | 157 (4.4) | ||

| 30–34 | 266 (7.4) | PhD | 24 (0.7) | ||

| 35–39 | 186 (5.2) | Healthcare worker | 634 (17.7) | ||

| >39 | 380 (10.6) | Government institution | 283 (7.9) | ||

| Social status (%) | Single | 2279 (63.5) | Occupation (%) | Private institution | 182 (5.1) |

| In a relationship | 286 (8.0) | Business | 198 (5.5) | ||

| Married | 943 (26.3) | Military | 32 (0.9) | ||

| Divorced | 46 (1.3) | Unemployed | 1822 (50.8) | ||

| Widowed | 32 (0.9) | Other | 435 (12.1) | ||

| Economic status (%) | Poor* | 247 (6.9) | Household members (%) | 0 | 46 (1.3) |

| Moderate† | 1247 (34.8) | 1–5 | 2751 (76.7) | ||

| Good‡ | 1761 (49.1) | >5 | 789 (22) | ||

| Excellent§ | 331 (9.2) |

*Poor: income does not provide essential needs for the family.

†Moderate: income provides essential needs for the family but no more.

‡Good: income provides essential needs and some luxury requirements.

§Excellent: income provides luxury requirements.

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants according to governorates and education level.

General knowledge regarding COVID-19

Participants showed a good level of awareness regarding COVID-19 (75.6%±9.4%). An adequate level of basic knowledge (67.0%±18.9%) was found among participants: 3383 (94.3%) knew that a virus was the causative agent of COVID-19; 2535 (70.7%) correctly identified the incubation period as being between 2 days and 2 weeks. Only 1500 (41.8%) believed that an infection with COVID-19 does not confer lifelong immunity. The majority of participants 3489 (97.3%) were aware that COVID-19 infection in high-risk groups can be fatal. There is currently insufficient evidence on whether infertility is a complication of COVID-19 infection; 461 (12.9%) participants believed that COVID-19 can cause infertility while 1903 (53.0%) did not. A total of 2986 (83.3%) and 2597 (72.4%) correctly answered that there are currently no available vaccine or treatments, respectively; however, there were misconceptions about the efficacy of antibiotics and ibuprofen as treatments, 1228 (34.2%) and 1268 (35.3%), respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

General knowledge, transmission, signs and symptoms, and prevention of COVID-19: (n=3586)

| General knowledge | |||||

| Causative agent, N (%) | Virus | 3383 (94.3) | Incubation period N (%) | 1 min– 1 hour |

18 (0.5) |

| Bacteria | 39 (1.1) | 1 hour– 2 days |

58 (1.6) | ||

| Parasite | 8 (0.2) | 2 days–2 weeks | 2535 (70.7) | ||

| Immune deficiency | 46 (1.3) | ||||

| Fungus | 0 (0.0) | 2 weeks–1 month | 958 (26.7) | ||

| Inherited | 2 (0.1) | ||||

| Do not know | 108 (3.0) | >1 month | 17 (0.5) | ||

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Do not know (%) |

|||

| Can infection with COVID-19 confer permanent immunity? | 815 (22.7) | 1500 (41.8) | 1271 (35.5) | ||

| Can COVID-19 cause severe illness and lead to death in elderly, chronically ill and immunodeficient patients? | 3489 (97.3) | 28 (0.8) | 69 (1.9) | ||

| Can COVID-19 cause infertility? | 461 (12.9) | 1222 (34.1) | 1903 (53.0) | ||

| Is COVID-19 teratogenic (ie, cause malformations/abnormalities to an embryo/fetus)? | 157 (4.4) | 1433 (40.0) | 1996 (55.6) | ||

| Is there no available treatment against COVID-19? | 2597 (72.4) | 515 (14.4) | 474 (13.2) | ||

| Can COVID-19 be treated with antibiotics? | 1228 (34.3) | 1790 (49.9) | 568 (15.8) | ||

| Can COVID-19 be treated with ibuprofen? | 1268 (35.3) | 1921 (53.6) | 397 (11.1) | ||

| Are there available COVID-19 vaccines? | 103 (2.9) | 2986 (83.3) | 497 (13.8) | ||

| Transmission pathways | |||||

| Respiratory droplets (from coughing or sneezing) | 3521 (98.2) | 21 (0.6) | 44 (1.2) | ||

| Handshaking | 3330 (92.9) | 189 (5.3) | 67 (1.8) | ||

| Touching an infected person’s personal belongings | 3387 (94.4) | 131 (3.7) | 68 (1.9) | ||

| Animals to human | 910 (25.4) | 1973 (55.0) | 703 (19.6) | ||

| Undercooked food | 1301 (36.3) | 1734 (48.3) | 551 (15.4) | ||

| Sexual contact | 1210 (33.7) | 1477 (41.2) | 899 (25.1) | ||

| Horizontal transmission | 1130 (31.5) | 1160 (32.4) | 1296 (36.1) | ||

| Signs and symptoms | |||||

| Fever | 3563 (99.4) | 9 (0.2) | 14 (0.4) | ||

| Sneezing | 2353 (65.6) | 1000 (27.9) | 233 (6.5) | ||

| Sore throat | 3037 (84.7) | 358 (10.0) | 191 (5.3) | ||

| Headache | 3186 (88.8) | 190 (5.3) | 210 (5.9) | ||

| Chest pain | 3050 (85.0) | 254 (7.1) | 282 (7.9) | ||

| Body aches (generalised pain) | 3019 (84.2) | 260 (7.2) | 307 (8.6) | ||

| Fatigue | 3405 (95.0) | 72 (2.0) | 109 (3.0) | ||

| Diarrhoea | 1972 (55.0) | 971 (27.1) | 643 (17.9) | ||

| Dry cough | 3466 (96.7) | 44 (1.2) | 76 (2.1) | ||

| Productive cough | 458 (12.8) | 2586 (72.1) | 542 (15.1) | ||

| Bleeding | 130 (3.6) | 2613 (72.9) | 843 (23.5) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 2221 (61.9) | 375 (10.5) | 990 (27.6) | ||

| Prevention methods | |||||

| Does wearing a face mask outside the home offer protection from COVID-19? | 3204 (89.3) | 314 (8.8) | 68 (1.9) | ||

| Does washing hands with soap and water offer protection from COVID-19? | 3574 (99.7) | 5 (0.1) | 7 (0.2) | ||

| Does avoiding crowded places offer protection from COVID-19? | 3574 (99.7) | 4 (0.1) | 8 (0.2) | ||

| Does the influenza vaccine offer protection from COVID-19? | 331 (9.2) | 2482 (69.2) | 773 (21.6) | ||

| Does staying at home offer protection from COVID-19? | 3554 (99.1) | 15 (0.4) | 17 (0.5) | ||

| Does using hand sanitiser offer protection from COVID-19? | 3430 (95.6) | 104 (2.9) | 52 (1.5) | ||

| Does cleaning household surfaces with bleach offer protection from COVID-19? | 3408 (95.0) | 110 (3.1) | 68 (1.9) | ||

| Does cleaning fruits and vegetables with soap and water offer protection from COVID-19? | 3262 (90.9) | 221 (6.2) | 103 (2.9) | ||

| Does cleaning surfaces with a mixture of Flash and bleach offer a safe protection from COVID-19? | 158 (4.4) | 3301 (92.1) | 127 (3.5) | ||

| Does the quarantine of symptomatic individuals protect others from COVID-19? | 3305 (92.2) | 241 (6.7) | 40 (1.1) | ||

| Do cumin, anise and mint offer protection from COVID-19? | 1041 (29.0) | 1934 (53.9) | 611 (17.1) | ||

Transmission, and signs and symptoms regarding COVID-19

There was a fair level of awareness (70.7%±16.9%) regarding COVID-19 transmission pathways. A high level of awareness was demonstrated regarding common transmission pathways: 3521 (98.2%), 3387 (94.4%) and 3330 (92.9%) identified respiratory droplets, touching an infected person’s personal belongings and handshaking, respectively. There is currently limited evidence of animal-to-human and sexual transmission; 703 (19.6%) did not know if transmission occurs between animals and humans, while 899 (25.1%) did not know if the virus is transmitted sexually (table 2).

The data showed a good level of awareness (76.0%±13.6%) regarding clinical features. When asked about the main clinical features, participants correctly identified fever 3563 (99.4%), sore throat 3037 (84.7%), headache 3186 (88.8%), chest pain 3050 (85.0%), general pain 3019 (84.2%), fatigue 3405 (95.0%) and dry cough 3466 (96.7%), whereas only 1972 (55.0%) knew that diarrhoea can be a symptom. Only 2221 (61.9%) were aware that infected individuals may be asymptomatic (table 2).

Prevention methods regarding COVID-19

The highest level of awareness was in the prevention section (88.8%±10.2%). Washing hands with soap, avoiding crowded areas, remaining at home and wearing a face mask outside are the principal preventative measures against COVID-19: 3574 (99.7%), 3574 (99.75%), 3554 (99.1%) and 3204 (89.3%), respectively. A minority of 158 (4.4%) believed that cleaning with a mixture of Flash and bleach is a sound preventive measure. Only 2482 (69.2%) knew that the influenza vaccine offers no protection against COVID-19 (table 2).

Statistical analysis of the data

A series of one-way ANOVA analyses revealed that mean knowledge differed significantly across: gender (p=0.009), age (p=0.003), social status (p=0.042), education level (p<0.001), economic status (p<0.001), number of household members (p<0.001), place of residence (p<0.001) and source of information (p<0.001) (table 3). Participants living in Lattakia (77.6%) exhibited the greatest awareness, whereas those in Ar-Raqqah (71.7%) followed by Deir-ez-Zor (71.8%) exhibited the lowest. The mean knowledge differed across groups that acquired information from different sources, the lowest awareness was among participants who chose family members/friends as one of their source(s) (74.0%), whereas those with the highest awareness acquired their information from lectures as one of their source(s) (78.2%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Mean knowledge score of participants by demographic variables and source of information (one way ANOVA), (n=3586)

| Characteristics | Number of participants (%) | Mean knowledge score (±SD%) |

F-test/t-test | P value | |

| Gender | Male | 1142 (31.8) | 75.0 (±10.1) | −2.625 | 0.009 |

| Female | 2444 (68.2) | 75.9 (±9) | |||

| Age group (years) |

<20 | 1204 (33.6) | 75.0 (±9.9) | 2.990 | 0.011 |

| 20–24 | 1104 (30.8) | 76.4 (±9.3) | |||

| 25–29 | 446 (12.4) | 76.0 (±9.4) | |||

| 30–34 | 266 (7.4) | 75.4 (±9.4) | |||

| 35–39 | 186 (5.2) | 76.1 (±7.6) | |||

| >39 | 380 (10.6) | 75.1 (±8.6) | |||

| Social status | Single | 2279 (63.5) | 75.8 (±9.3) | 2.485 | 0.042 |

| In a relationship | 286 (8.0) | 76.6 (±8.6) | |||

| Married | 943 (26.3) | 75.1 (±9.4) | |||

| Divorced | 46 (1.3) | 73.9 (±8.8) | |||

| Widowed | 32 (0.9) | 73.4 (±15.9) | |||

| Residence | Urban | 2426 (67.7) | 75.8 (±9.3) | 1.652 | 0.099 |

| Rural | 1160 (32.3) | 75.3 (±9.6) | |||

| Education | Primary school | 25 (0.7) | 66.5 (±12.4) | 26.176 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate school | 166 (4.6) | 73.2 (±9.3) | |||

| Secondary school | 375 (10.4) | 70.0 (±13) | |||

| College/university | 2839 (79.2) | 76.3 (±8.9) | |||

| Master’s degree | 157 (4.4) | 77.2 (±9.7) | |||

| PhD | 24 (0.7) | 76.6 (±8.5) | |||

| Occupation | Healthcare worker | 634 (17.7) | 78.6 (±8.6) | 16.379 | <0.001 |

| Government institution | 283 (7.9) | 75.7 (±7.9) | |||

| Private institution | 182 (5.1) | 75.5 (±9) | |||

| Business | 198 (5.5) | 73.4 (±10.2) | |||

| Military | 32 (0.9) | 71.2 (±15.6) | |||

| Unemployed | 1822 (50.8) | 75.3 (±9.2) | |||

| Other | 435 (12.1) | 74.0 (±10.2) | |||

| Economic status | Excellent | 331 (9.2) | 76.6 (±11.1) | 7.108 | <0.001 |

| Good | 1761 (49.1) | 76.2 (±9.4) | |||

| Moderate | 1247 (34.8) | 74.9 (±9) | |||

| Poor | 247 (6.9) | 74.3 (±9.3) | |||

| Household members | 0 | 46 (1.3) | 74.4 (±10.6) | 15.451 | <0.001 |

| 1–5 | 2751 (76.7) | 76.1 (±9) | |||

| >5 | 789 (22.0) | 74.0 (±10.2) | |||

| Source of information | Health websites | 2823 (78.7) | 76.4 (±8.7) | 24.523 | <0.001 |

| Social media | 1998 (55.7) | 74.6 (±9.6) | |||

| Television/radio | 1572 (43.8) | 75.5 (±9) | |||

| Family members/friends | 528 (14.7) | 74.0 (±10.3) | |||

| Lectures | 517 (14.4) | 78.2 (±7.5) | |||

| Magazines/books | 266 (7.4) | 77.6 (±8.8) | |||

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

When participants were asked if they were likely to share new information with friends and family, 3513 (98.0%) answered ‘yes’. There was a significant difference in mean knowledge between those who were inclined to disseminate new information about COVID-19 to friends and family (75.7%) compared with those who were not (72.3%) (p=0.002). On exclusive use of personal belongings, 2692 (75.1%) answered ‘yes’. We found no significant correlation between mean knowledge and participant tendency to share personal belongings with others (p=0.112). Of participants who knew someone infected with COVID-19, 65 (1.8%) answered ‘yes’. There was no significant difference in mean knowledge between those who knew an infected individual (75.9%) compared with those who did not (75.6%) (p=0.816).

Multiple linear regression

Multiple linear regression analysis results: male gender (vs female, β=−0.933, p=0.005); education of secondary school or lower (vs college/university and above, β=−3.782, p<0.001); careers in government, private, business, military and ‘other’ sectors, as well as unemployment (vs healthcare workers, β=−3.592, p<0.001); poor and moderate economic status (vs good and excellent, β=−0.669, p<0.040); and over five household members (vs 1–5, β=−1.737, p<0.001) were associated with significantly poorer knowledge scores (table 4). Careers in healthcare (vs unemployed, β=3.592, p<0.001) and the 31–45 age group (vs 16–30, β=1.511, p=0.005) were associated with significantly higher knowledge scores.

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression on variables associated with poor COVID-19 knowledge

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t | P value |

| Male gender (reference: female) | −0.933 | 0.334 | −2.794 | 0.005 |

| Education of secondary school or lower (reference: college/university and above) | −3.782 | 0.466 | −8.125 | <0.001 |

| Careers in government, private, business, military and ‘other’ sectors, as well as unemployment (reference: healthcare workers) | −3.592 | 0.474 | −7.579 | <0.001 |

| Poor and moderate economic status (reference: good and excellent) | −0.669 | 0.325 | −2.057 | 0.040 |

| >5 household members (reference: 1–5) | −1.737 | 0.374 | −4.648 | <0.001 |

Discussion

We found an overall mean knowledge score of 75.6%, indicating that most participants were relatively knowledgeable about COVID-19, though less so compared with their counterparts in China (90%).14 This level of knowledge was unexpected given that only 10 cases of COVID-19 had been confirmed in Syria at the time of the survey.26

Poor knowledge was associated with males, non-post-secondary education, non-healthcare occupations, unemployment, poor and moderate economic status, and households with more than five members. Similar trends were observed in China.14 Correlating sociodemographic variables with awareness is critical to public health efforts to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. The data obtained from this study can be leveraged by the Syrian Ministry of Health to tailor prevention and educational campaigns to populations with the widest knowledge gaps.

Our study showed a relatively high level of awareness 2535 (70.7%) among the population. In the general knowledge section (mean knowledge score 67%), the majority of the participants 3383 (94.3%) knew that COVID-19 is caused by a virus. This was similar to a Pakistani study (93.3%).19 Low awareness of the incubation period of 2–14 days was found27 among dentists (36.1%) and HCWs (36.4%) in similar studies.15 21 Syria has a relatively young population. Statistical data from 2018 showed that only an estimated 4.5% of the population was over the age of 65 years.28 A total of 3489 (97.3%) knew that COVID-19 infection can be severe and potentially fatal in elderly, chronically ill and immunodeficient patients. This is higher than in studies conducted in China (73.2%) and India (88.37%).14 29 A total of 40.6% of Syrians are hypertensive, yet a staggering 79.8% of them are unaware of their condition. Diabetes is also prevalent, affecting 11.9% of the population.30 31 Such a rampant lack of awareness about chronic diseases associated with high mortality in patients with COVID-19 underscores the need for targeted awareness campaigns.

At the time of the survey, no standardised evidence-based protocols had yet been developed to treat COVID-19 infections; only 2597 (72.4%) participants knew that there was no available treatment at that time. This is higher than a Kenyan study (40%) but significantly lower than a Chinese study (94%).14 17 A minority 103 (2.9%) of participants thought there was a vaccine available against COVID-19, even though vaccines have only become commercially available in the past few months. By contrast, Coimbatore District and Pakistan were less informed, with (18.6%) and (11.6%), respectively, believing that such a vaccine was available at the time. In the absence of a vaccine or effective treatment protocol for COVID-19 at the time of the survey, controlling the spread of the disease was the best line of defence, and remains so given the dire shortage of medication, ventilators, ICU capacity and the continued lack of a vaccine available to the Syrian people. We observed a considerable knowledge gap in 1268 (35.3%) with regard to ibuprofen as a treatment option. There is no available evidence to suggest that ibuprofen is effective against COVID-19.32

Participants showed a fair level of awareness regarding transmission pathways (70.7%), very similar to a Pakistani study (70.8%).19 The majority 3521 (98.2%) of participants were aware that respiratory droplets are common transmission vectors; this is similar to a Chinese study (97.8%) but much higher than an Indian study (29.5%).14 18 A total of 3330 (92.9%) participants identified handshaking as a transmission pathway, higher than a study among Jordanian dentists (85.6%).15

The majority of survey participants were sufficiently aware of the clinical features of COVID-19 (76.0%), similar to a Pakistani study (77.7%).19 A very high level of awareness of the most common symptoms was found: fever 3563 (99.4%), dry cough 3466 (96.7%), fatigue 3405 (95.0%) and myalgia 3019 (84.2%), similar to findings from Chinese (96.4%) and Indian (95.4%) studies.14 29 When asked about sore throat, a high level of awareness 3037 (84.7%) was found compared with studies from India (15.2%) and among dentists in Jordan (28.5%).15 18 Knowledge about diarrhoea as a symptom was lacking: only 1972 (55.0%); a study among dentists also showed low awareness (39.9%).15 18 While infected individuals are frequently asymptomatic or present with mild symptoms, around one in every five infections can be serious enough to require hospitalisation.33 34 Only 2221 (61.9%) participants were aware that infected individuals can be asymptomatic, while a study among dentists (34.5%) reported much lower awareness. Increasing public awareness about the variability of symptoms is particularly important since those with mild or unreported symptoms may significantly contribute to the transmission of COVID-19. The lack of health insurance, paid sick leave, telecommuting, or other social and professional safety nets increases the likelihood that these ‘silent spreaders’ will under-report symptoms for fear of being forced to miss work.

We found a high level of awareness in the preventive methods section (88.8%), similar to a Pakistani study (85%).19 Hand hygiene has been known to be an important element of infection control since the 14th century.35 Implementing handwashing techniques can break the transmission cycle and reduce the risk of infection by 6%–44%.36 Almost all 3574 (99.7%) participants were aware that washing hands with soap and water is an important preventive measure against COVID-19. This finding is in accordance with studies from Jordan (97.0%) and India (96.2% and 87%).15 18 21

This year, the WHO recommended that the following mitigation measures be implemented during the holy month of Ramadan: cancelling social and religious gatherings, holding events outdoors for adequate ventilation, physical distancing of at least 1 m between people and the use of technology to broadcast ceremonies on television.37 38 The majority 3574 (99.7%) identified avoiding mass gatherings as a preventive measure; studies in China (98.6%) and Coimbatore District (97.7%) reported similar awareness.14 29 Cheap and efficient interventions such as N95 (filtration capacity=95%) have a 91% effectiveness of blocking pathogen transmission.39 A total of 3204 (89.3%) participants considered wearing a face mask when leaving home as an effective prevention method, compared with a Coimbatore District study (93.02%).29

Since Syrian society is particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, this knowledge gap is potentially dangerous and should be addressed to mitigate disease spread. Only 2482 (69.2%) knew that the influenza vaccine offers no protection against COVID-19; this is similar to a Coimbatore District study (67.4%), but lower than a study among HCWs (90.7%).21 29 A total of 3305 (92.2%) were aware that individuals showing symptoms should quarantine themselves, lower than in China (98.2%) and India (95.8%).14 18

North-East Syria (NES) has a population of over 4 million people, 600 000 of whom are internally displaced refugees, 100 000 of whom live in overcrowded camps: only 2 of NES’s 11 hospitals are currently functioning. NES consists of three governorates: Ar-Raqqah, Deir-ez-Zor and Al-Hasakah. With only 22 ICU beds, (18 in Al-Hasakah, 4 in Ar-Raqqah and none in Deir-ez-Zor), the maximum capacity threshold is only 80 COVID-19 cases. Ar-Raqqa and Deir-ez-Zor, the most vulnerable governorates, also showed the lowest awareness in the study (71.7%) and (71.8%). This is a potentially catastrophic situation, and a concern to the international community, as an unmonitored, uncontrolled outbreak in NES can prolong the global pandemic.

Limitations

Our findings may not be generalised to the wider Syrian population. The authors used a convenience sampling strategy involving various social media platforms. Credible published national data regarding the sociodemographic characteristics of Syrians are not available to evaluate the representativeness of our sample. Syrians vulnerable to COVID-19, such as the elderly and rural residents, are more likely to exhibit poor knowledge and awareness due to limited internet access. As such, reaching out to these populations must be prioritised. Even though all Syrian governorates were represented in this study, most participants lived in Damascus and Rural Damascus. Furthermore, an assessment of the Syrian population’s practices relating to COVID-19 and the attitudes driving them is necessary to complete the picture.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has been a dire warning to humanity about the fragility of its social, economic and healthcare institutions. Our study revealed good public awareness of clinical features and preventive measures. However, general knowledge and knowledge about transmission pathways were suboptimal. Syrians of good socioeconomic status, in particular young well-educated women, have shown good knowledge. Our national response must adapt to the growing threat of COVID-19 by adopting public awareness strategies and behaviours to contain the disease both within and beyond our borders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the management of the Syrian Private University for the support in the field of medical training and research. We are thankful to everyone who participated in this study and to Mrs Marah Marrawi for her statistical help. We would also like to thank Mr Rod Usher for his valuable comments on the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: FM conceptualised the study, participated in the design, wrote the study protocol, performed the statistical analysis, did a literature search and drafted the manuscript. BB participated in study design, did a literature search and drafted the manuscript. HA and NA did a literature search and revision of the draft. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. The data are available with the corresponding author (FM), fatemamohsena@gmail.com.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Syrian Private University (SPU). The IRB at SPU did not provide us with a number/ID. All participants confirmed their written consent by answering a yes–no question. Participants under the age of 18 years required verbal informed parental consent, as well as submission of parent/guardian contact information. The researchers were responsible for contacting the parents/guardians to obtain verbal consent before the child was given access to the survey. The verbal and written form of consent was approved by the IRB at SPU. Participation in the study was voluntary and participants were assured that anyone who was not inclined to participate or decided to withdraw after giving consent would not be victimised. All information collected from this study was kept strictly confidential.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viner RM, Ward JL, Hudson LD, et al. Systematic review of reviews of symptoms and signs of COVID-19 in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2020:archdischild-2020-320972. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehraeen E, Salehi MA, Behnezhad F, et al. Transmission modes of COVID-19: a systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2020;26:125–36. 10.1016/j.ijso.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Affairs UOftCoH, Organization WH . Syrian Arab Republic: COVID-19 humanitarian update No. 23 as of 1 February 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-awsat A. Syria Grapples with third COVID-19 wave, 2021. Available: https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/2836166/syria-grapples-third-covid-19-wave

- 6.McKernan B. Syria confirms first Covid-19 case amid fears of catastrophic spread. The Guardian, 2020. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/23/syria-confirms-first-covid-19-coronavirus-case-amid-fears-of-catastrophic-spread

- 7.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 106, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200505covid-19-sitrep-106.pdf?sfvrsn=47090f63_2

- 8.Gharibah M, Mehchy Z. COVID-19 pandemic: Syria’s response and healthcare capacity. London, UK: Conflict Research Programme, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajilore K, Atakiti I, Onyenankeya K. College students’ knowledge, attitudes and adherence to public service announcements on Ebola in Nigeria: Suggestions for improving future Ebola prevention education programmes. Health Educ J 2017;76:648–60. 10.1177/0017896917710969 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tachfouti N, Slama K, Berraho M, et al. The impact of knowledge and attitudes on adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a case-control study in a Moroccan region. Pan Afr Med J 2012;12:52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNatt Z, Boothby NG, Al-Shannaq H. Impact of separation on refugee families: Syrian refugees in Jordan. UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 2018. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D80P2GF9 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syria anniversary press release . United nations office for the coordination of humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 2020. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syria-anniversary-press-release-6-march-2020

- 13.reliefweb . Unicef Syria crisis situation report, 2019. Available: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/unicef-syria-crisis-situation-report-march-2019-humanitarian-results

- 14.Zhong B-L, Luo W, Li H-M, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16:1745. 10.7150/ijbs.45221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khader Y, Al Nsour M, Al-Batayneh OB, et al. Dentists' awareness, perception, and attitude regarding COVID-19 and infection control: cross-sectional study among Jordanian dentists. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020;6:e18798. 10.2196/18798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qarawi ATA, Ng SJ, Gad A, et al. Awareness and Preparedness of Hospital Staff against Novel Coronavirus (COVID-2019): A Global Survey - Study Protocol. SSRN Electronic Journal 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3550294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austrian K, Pinchoff J, Tidwell JB. COVID-19 related knowledge, attitudes, practices and needs of households in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya 2020. 10.2139/ssrn.3576785 [DOI]

- 18.Roy D, Tripathy S, Kar SK, et al. Study of knowledge, attitude, anxiety & perceived mental healthcare need in Indian population during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr 2020;51:102083. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain T, Khan S, Gilani U. Evaluation of general awareness among professionals regarding COVID-19: a survey based study from Pakistan 2020.

- 20.Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect 2020;105:183-187. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions: a survey on healthcare workers. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . Introduction to COVID-19: methods for detection, prevention, response and control. Available: https://openwho.org/courses/introduction-to-ncov

- 23.World Health Organization . Q&As on COVID-19 and related health topics. Available: https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/corona-virus/questions-and-answers.html

- 24.World Health Organization . Water, sanitation, hygiene and waste management for COVID-19: technical brief, 03 March 2020. Geneva: World Health organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . Key planning recommendations for mass gatherings in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 19 March 2020. Geneva: World Health organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 71, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200331-sitrep-71-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=4360e92b_8

- 27.Backer JA, Klinkenberg D, Wallinga J. Incubation period of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infections among travellers from Wuhan, China, 20-28 January 2020. Euro Surveill 2020;25. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.2000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plecher H. Syria: age structure from 2009 to 2019, 2020. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/326601/age-structure-in-syria/

- 29.Vadivu TS, Annamuthu P. An awareness and perception of COVID-19 among General Public–A cross sectional analysis, 2014. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Shenbhagavadivu-Thangavel-2/publication/340351891_An_Awareness_and_Perception_of_COVID_-19_among_General_Public_-_A_Cross_Sectional_Analysis/links/5e84b89a92851c2f52715214/An-Awareness-and-Perception-of-COVID-19-among-General-Public-A-Cross-Sectional-Analysis.pdf

- 30.World Health Organization . Web World health Organization–Diabetes country profiles: Diakses, 2016. Available: https://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/diabetes_profiles_explanatory_notes.pdf?ua=1

- 31.Tailakh A, Evangelista LS, Mentes JC, et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, and control in Arab countries: a systematic review. Nurs Health Sci 2014;16:126–30. 10.1111/nhs.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/the-use-of-non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-(nsaids)-in-patients-with-covid-19

- 33.Surveillances V. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Weekly 2020;2:113–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19: how COVID-19 spreads, 19 March 2020. Geneva: World Health organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Best M, Neuhauser D. Ignaz Semmelweis and the birth of infection control. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:233–4. 10.1136/qhc.13.3.233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabie T, Curtis V. Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: a quantitative systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2006;11:258–67. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01568.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization . Practical considerations and recommendations for religious leaders and faith-based communities in the context of COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/practical-considerations-and-recommendations-for-religious-leaders-and-faith-based-communities-in-the-context-of-covid-19

- 38.World Health organization . Safe Ramadan practices in the context of the COVID-19. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331767

- 39.Jefferson T, Foxlee R, Del Mar C, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. BMJ 2008;336:77–80. 10.1136/bmj.39393.510347.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-043305supp001.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. The data are available with the corresponding author (FM), fatemamohsena@gmail.com.