Abstract

Objective:

To identify causal pathophysiological mechanisms for atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events using protein measurements.

Approach and Results:

Carotid artery atherosclerosis was assessed by ultrasound and 86 cardiovascular-related proteins were measured using the Olink CVD-I panel in 7 Swedish prospective studies (11,754 individuals). The proteins were analyzed in relation to intima-media thickness in the common carotid artery (IMT-CCA), plaque occurrence, and incident cardiovascular events (composite end-point of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke) using a discovery/replication approach in different studies.

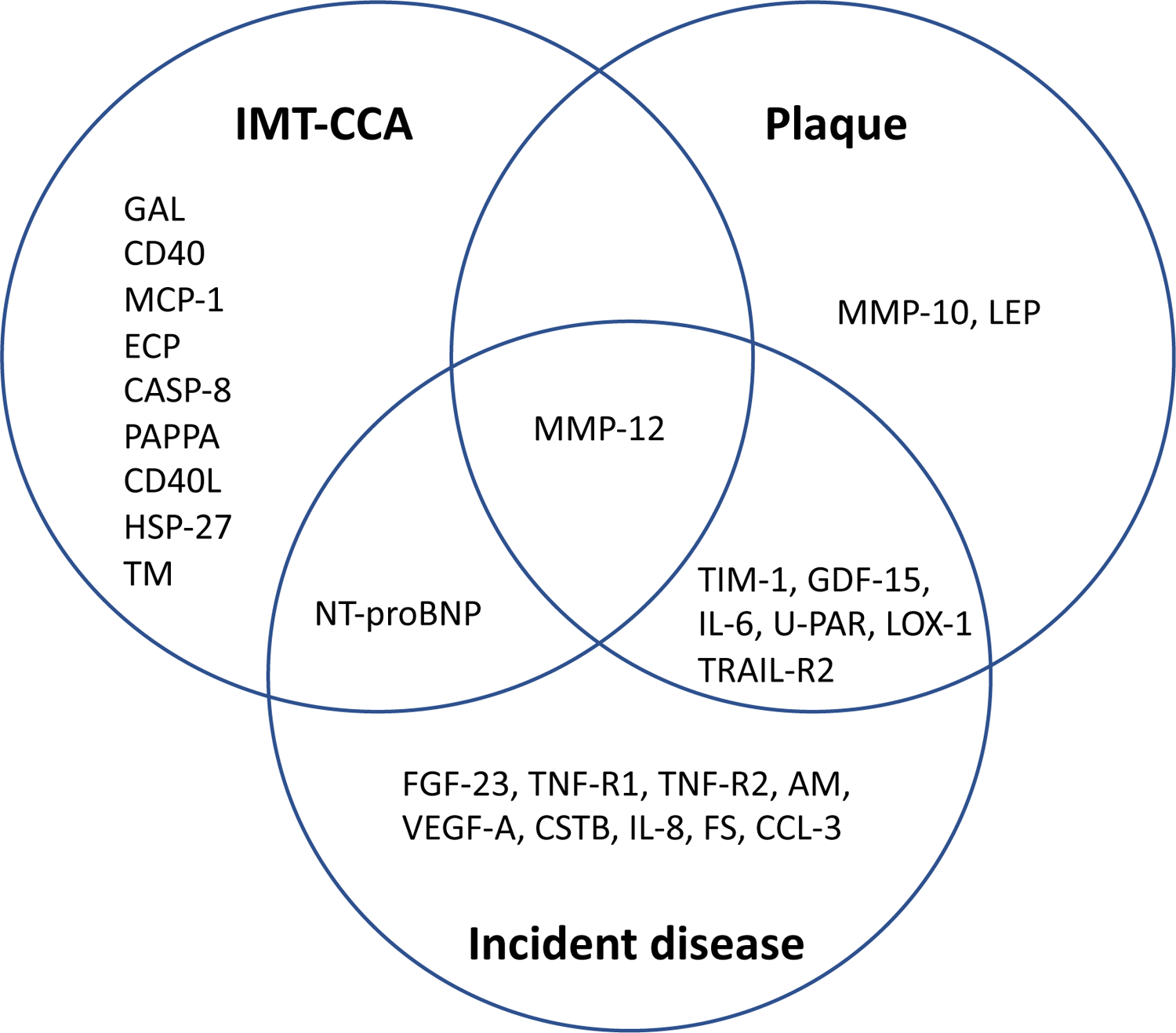

After adjustments for traditional cardiovascular risk factors, eleven proteins remained significantly associated with IMT-CCA in the replication stage, whereas nine proteins were replicated for plaque occurrence and seventeen proteins for incident cardiovascular events. NT-proBNP and MMP-12 were associated with both IMT-CCA and incident events, but the overlap was considerably larger between plaque occurrence and incident events, including MMP-12, TIM-1, GDF-15, IL-6, U-PAR, LOX-1 and TRAIL-R2. Only MMP-12 was associated with IMT-CCA, plaque, and incident events with a positive and concordant direction of effect. However, a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis suggested that increased MMP-12 may be protective against ischemic stroke (p=5.5 × 10−7), which is in the opposite direction of the observational analyses.

Conclusion:

The present meta-analysis discovered several proteins related to carotid atherosclerosis that partly differed in their association with IMT-CCA, plaque, and incident atherosclerotic disease. Mendelian randomization analysis for the top finding, MMP-12, suggest that the increased levels of MMP-12 could be a consequence of atherosclerotic burden rather than the opposite chain of events.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, epidemiology, carotid artery, ultrasound, Mendelian randomization

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Proteomics, Ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Intima-media thickness in the common carotid artery (IMT-CCA) and plaque occurrence in the carotid arteries measured by ultrasound are both regarded as valid biomarkers for subclinical atherosclerosis, based on their previously reported associations with incident cardiovascular events in observational studies1, 2. Since also genetic studies have shown associations between both IMT-CCA and plaque and both coronary heart disease and stroke3, both indices must be regarded as important characteristics of carotid atherosclerosis.

Proteins can today be measured with high accuracy using multiplex methods. Proteins also have the advantage of being measurable in frozen samples, and are functional products of the information stored in the genetic code. Furthermore, potential causal relationships between proteins and atherosclerotic outcomes can be readily evaluated using Mendelian Randomization (MR) with minimal risk of pleiotropy, provided that the Mendelian randomization model is based on genetic variants in the protein-encoding gene. MR uses genetic variants as a natural experiment to separate observational from causal relationships, and has become an established epidemiological tool4.

Several proteins have shown association with atherosclerosis when measured one by one in different studies5–9. Using targeted proteomics that tested 92 proteins preselected for potential links to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, we previously demonstrated that six4 proteins were related to carotid artery plaque occurrence, while none of the proteins were significantly related to IMT-CCA10. The lack of significant associations between proteins and IMT-CCA may be explained by limited statistical power, since our previous study included only ~900 individuals. Recently, we identified significant associations between four proteins and IMT-CCA in a larger meta-analysis11.

In the present study, we investigated 86 circulating proteins to identify pathophysiological mechanisms for atherosclerosis in a meta-analysis of 7 different samples with an overall sample size exceeding 11,000 participants. We thereafter evaluated if the identified proteins were casually related to atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries by use of 2-sample MR, using protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) from a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) of protein levels on the same analytical platform12 and a recent GWAS for IMT-CCA and plaque occurrence3.

In addition, in the same cohorts, we evaluated if the same proteins were associated with incident atherosclerotic events, defined as either myocardial infarction (MI) or ischemic stroke (IS). To assess whether the proteins were causal in MI and IS, we performed a 2-sample MR. The hypothesis tested was that the present meta-analysis would provide a number of proteins being related to both atherosclerosis and incident atherosclerotic disease, and that some of these relationships would reflect casual pathophysiological mechanisms for atherosclerosis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Samples

Seven different studies were used in the analyses. Of those, three were randomly selected population-based studies (the Malmö Diet and Cancer [MDC] study13, the Prospective Investigation of Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors [PIVUS] study14, and the Prospective investigation of Obesity, Energy and Metabolism [POEM] study15), one study consisted of high-cardiovascular risk individuals collected in five European countries (Carotid IMT and IMT-Progression as Predictors of Vascular Events in a High Risk European Population [IMPROVE])16, one study was a collection of subjects with diabetes (the Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes - A Prospective Study in Primary Care [CARDIPP])17, another one consisted of subjects with peripheral artery disease (Study of Atherosclerosis in Vastmanland [SAVA]- Peripheral Arterial Disease in Vastmanland [PADVA])18, while the last study consisted of control subjects from the same geographical area as those with peripheral artery disease (SAVA-control). The characteristics of the different studies are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic characteristics in the seven studies included in the meta-analysis.

given as mean and SD in parenthesis or proportions.

| MDC | PIVUS | POEM | CARDIPP | SAVA-control | SAVA-PADVA | IMPROVE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of data collection | 1991–1994 | 2001–2004 | 2010–2015 | 2005–2008 | 2005–2011 | 2005–2011 | 2004–2005 | |||||||

| n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | n | Mean | |

| Age | 4742 | 57 (5.9) | 954 | 70 (0.1) | 496 | 50 (0.1) | 741 | 60 (3.0) | 737 | 66 (9.3) | 381 | 69 (6.9) | 3703 | 64 (5.5) |

| Sex (% female) | 4742 | 60 | 954 | 50 | 496 | 51 | 741 | 35 | 737 | 29 | 381 | 59 | 3703 | 52 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 4742 | 140 (18) | 951 | 149 (22) | 496 | 125 (16) | 708 | 128 (17) | 737 | 147 (21) | 380 | 144 (20) | 3698 | 141 (18) |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 4741 | 1.3 (0.4) | 951 | 1.5 (0.4) | 496 | 1.3 (0.4) | 727 | 1.1 (1.3) | 728 | 1.3 (0.4) | 377 | 1.2 (0.4) | 3687 | 1.2 (0.4) |

| LDL (mmol/l) | 4736 | 4.1 (0.9) | 949 | 3.3 (0.9) | 496 | 3.4 (0.9) | 712 | 2.2 (2.4) | 715 | 3.6 (1.1) | 372 | 2.6 (0.9) | 3623 | 3.5 (1.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 4742 | 25.7 (3.9) | 954 | 26.9 (4.2) | 496 | 26.4 (4.2) | 740 | 30.0 (4.7) | 737 | 26.7 (3.8) | 381 | 27.0 (4.1) | 3700 | 27.2 (4.2) |

| Diabetes (%) | 4742 | 7.7 | 954 | 12 | 496 | 3.2 | 741 | 100 | 737 | 9 | 381 | 25 | 3703 | 27 |

| Current smoking (%) | 4736 | 21 | 953 | 11 | 493 | 8.2 | 741 | 19 | 737 | 11 | 381 | 17 | 3703 | 14 |

| IMT-CCA (mm) | 4709 | 0.76 (0.15) | 954 | 0.89 (0.16) | 496 | 0.65 (0.13) | 741 | 0.73 (0.18) | 737 | 0.81 (0.17) | 381 | 0.92 (0.20) | 3699 | 0.74 (0.14) |

| Plaque prevalence (%) | 4565 | 43 | 896 | 65 | NA | 741 | 78 | 737 | 33 | 381 | 87 | 3703 | 69 | |

NA, Not assessed; SBP, systolic blood pressure; IMT-CCA, intima-media thickness in the common carotid artery.

Traditional cardiovascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol, body mass index (BMI) and prevalent diabetes) were determined by conventional methods, such as physical examinations, standard laboratory tests and questionnaire data. Self-reported smoking status was used.

Measurement of carotid ultrasound

In all studies, the common carotid artery, the bulb and the internal carotid artery were scanned with a 10 Hz transducer. IMT was imaged in CCA one cm proximal of the bulb (IMT-CCA), and the measurements analysis were performed by the same semi-automated software in all studies (AMS). Plaque occurrence (binary) was defined as either a local thickening of IMT of >50% or an IMT>1.2 mm in the bulb or in CCA. A detailed description of the carotid examinations could be found in19.

Protein analysis

Using the proximity extension assay (PEA)20, 92 cardiovascular-related proteins (CVD-I panel, Olink Proteomics, Uppsala, Sweden) were measured in all included subjects. Six of the proteins were removed prior to analysis since more than 25 % of observations were below the assay detection limit in most studies.

Incident atherosclerotic disease

We used a composite end-point combining fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction (ICD-10 code I21) or ischemic stroke (codes I63.0–5 and 7–9). Diagnoses and dates were obtained from the Swedish in-patient register and cause of death register. The IMPROVE study also includes individuals from other countries, and the collection of incident cases of atherosclerotic disease has previously been described in that study16. Data on incident cases were not available in POEM and SAVA/PADVA.

Statistical analysis

All protein measurements were given from the laboratory on the Log(2)-scale to ensure normally distributed data. These values were thereafter transformed to a SD-scale for easy comparison between the proteins. Also IMT-CCA was log-transformed to achieve a normal distribution.

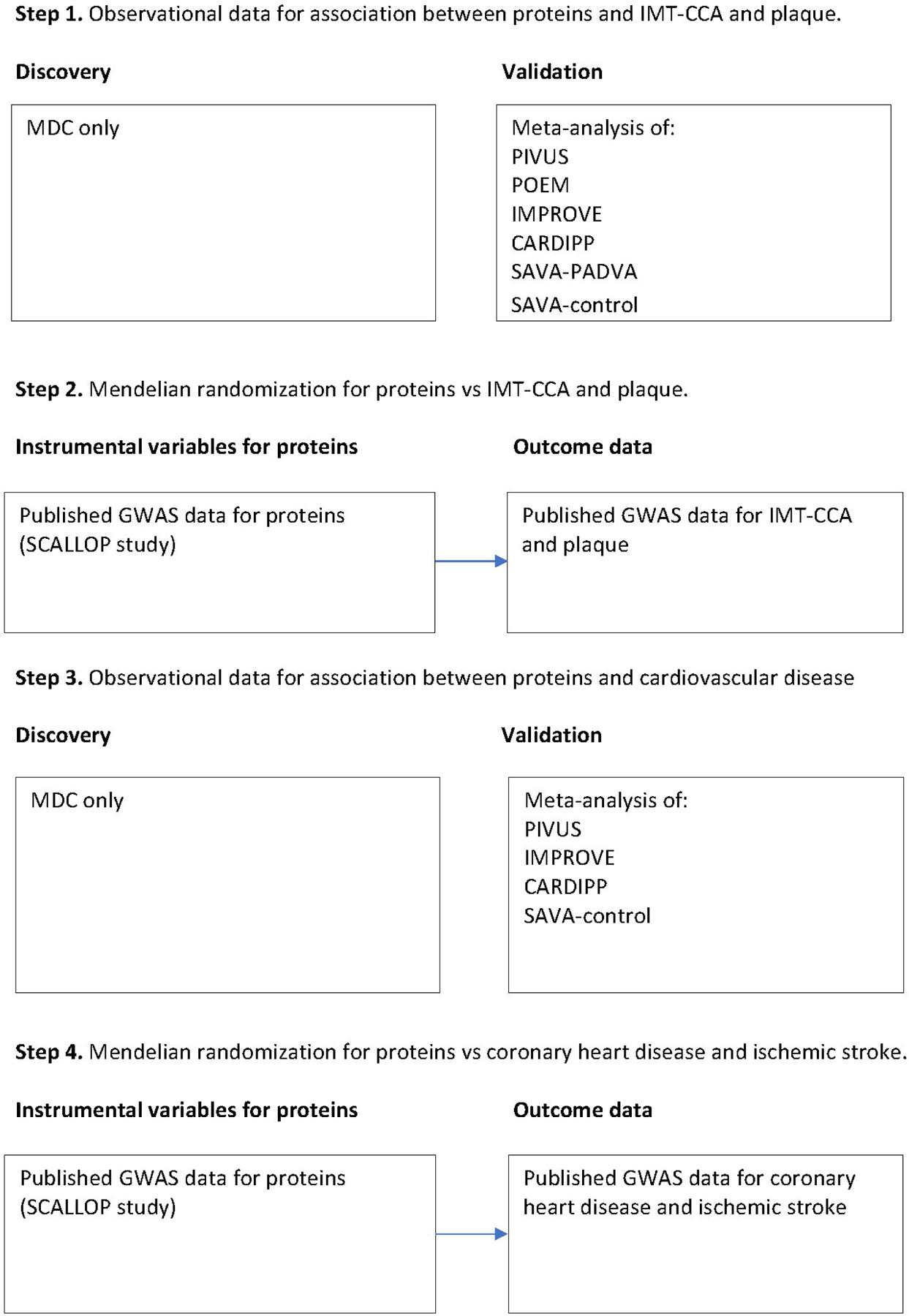

Step 1: Proteins vs IMT-CCA and plaque

Regarding IMT-CCA, a linear regression model with IMT-CCA as the dependent variable and a protein as the independent variable, with covariate adjustment for age and sex as confounders, was evaluated for each of the proteins. A similar model was tested for each protein, but in this case the traditional risk factors (systolic blood pressure, HDL- and LDL-cholesterol, BMI, current smoking and prevalent diabetes) were also adjusted for in addition to age and sex.

The largest of the samples, MDC, was used for the discovery phase of the protein vs IMT-CCA/plaque relationships, and a false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% was used as criterion in the age and sex-adjusted analysis to take a protein forward to the validation step. The validation step used an inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis of the remaining six samples using FDR<5% for the age and sex-adjusted analysis. In addition, we demanded the multiple-adjusted p-value to be <0.05 in order to claim that the relationship between a protein and an outcome was significant. Also the sign of direction for an association had to be the same in the discovery and validation analyses in order to be judged as being valid.

For prevalent plaque, a similar approach was applied as for IMT-CCA with plaque as the dependent variable, but in this case logistic regression analysis was used.

As secondary analyses, we also performed meta-analyses including all samples. Since those analyses were not replicated, we used the more stringent Bonferroni adjustment of the p-value as the limit of significance (p=0.05/86=0.00058).

Step 2: Mendelian randomization for IMT-CCA and plaque

The 2-sample MR analysis, evaluating the relationships between proteins and IMT-CCA/plaque, used instrumental variables from a recently published GWAS for the protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) (SCALLOP)12. To obtain data on genetic variants related to carotid atherosclerosis, a recently published GWAS for IMT/plaque loci was used, including around 70,000 individuals for IMT-CCA, and 48,000 individuals for carotid plaque3. For each SNP used in the MR-analyses, we have checked that the effect allele is the same in the instrument compared to the outcome GWAS.

In the gene-protein step, an LD-pruning for the GWAS significant SNPs (p<5×10−8) was performed, so that only independent SNPs (r<0.001 for LD) were used in the MR analysis. The primary analysis included only cis-pQTLs (defined as a locus within 1 Mb of the gene encoding the protein), but in an exploratory analysis also trans-pQTLs were included. The Wald ratio was used to obtain the causal estimate when only one pQTL was used as instrumental variable. An inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis (IVW) was used when more than one SNP was used as instrumental variable. When > 3 pQTLs were evaluated, also MR Egger and the weighted median method were used. Since we tested the potential causality of 19 proteins vs two outcomes in the MR analyses, we set the level of significance to 0.05/2×19=0.0013.

The genetic instruments used in the MR analyses are given in Supplemental Table I.

Step 3: Proteins and incident atherosclerotic disease

When the relationships between the proteins and incident atherosclerotic disease were studied, we used a composite endpoint of fatal or non-fatal MI or IS. Similar to the above-mentioned analyses, MDC was used as discovery cohort and a meta-analysis of the other cohorts were used for replication. An FDR of 5% for the age and sex-adjusted results was applied for both discovery and replication. Cox proportional hazards models were used, with one model being adjusted for age and sex and the other also for traditional risk factors. We demanded the multiple-adjusted p-value to be <0.05 in order to claim that the relationship between a protein and an outcome was significant. Also the sign of direction for an association had to be the same in the discovery and validation analyses in order to be judged as being valid.

As secondary analyses, we also performed meta-analyses including all samples. Since those analyses were not replicated, we used the more stringent Bonferroni adjustment of the p-value as the limit of significance (p=0.05/86=0.00058).

Step 4: Mendelian randomization for coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke

As described above, a 2-sample MR analysis was used to evaluate the potential causal relationships between the 17 proteins showing association with incident cardiovascular events. In this case, GWAS pQTL data from the SCALLOP CVD-I study12 was used for instrumental variable selection. CARDIoGRAMplusC4D21 was used for the GWAS of the outcome coronary artery disease (CAD), and MEGASTROKE22 was used for the outcome stroke. For each SNP used in the MR-analyses, we have checked that the effect allele is the same in the instrument compared to the outcome GWAS. Since we tested 17 pQTLs for proteins vs two different outcomes in the MR analyses, we set the level of significance to 0.05/2×17=0.0014 in this analysis.

STATA16 (Stata inc, College Station, TX; USA) was used for the analyses, except for the LD-pruning step (clumping) of the gene vs protein relationships for which Plink 1.9 was used. For the statistical code, please see the Major Resources Table in the Supplemental Materials.

A flow chart for the different analyses performed and the different samples used in each step is given as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the different statistical analyses and the data included in each analysis step.

RESULTS

Step 1:

Proteins vs IMT-CCA

Of 63 proteins associated with IMT-CCA after age- and sex adjustment in the discovery cohort (Supplemental Table II), 21 were replicated at FDR<5% (Table 2). Of those 21 proteins, 11 remained significant at p<0.05 after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors. The strongest replicated associations after risk factor adjustments were matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) (positive relationship) and galanin (GAL) peptides (inverse relationship).

Table 2. Relationships between cardiovascular proteins and intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery (IMT-CCA).

Sixty-three proteins were identified in the discovery phase and were evaluated in the validation step. This table only show the 21 proteins with FDR<5% in the validation meta-analysis following adjustment for age and sex. Also data following further adjustment for cardiovascular (CV) risk factors are shown. We demanded the multiple-adjusted p-value to be <0.05 in order to claim that the relationship between a protein and an outcome was significant.

| Age and sex-adjusted | Adjusted for CV risk factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Beta | SE | p-value | Beta | SE | p-value |

| C-X-C motif chemokine 6 (CXCL6) | .019 | .00096 | 2.46e-27 | −.00137 | .00096 | .15 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) | .0086 | .00096 | 4.75e-19 | .0064 | .00096 | 2.19e-11 |

| Galanin peptides (GAL) | −.0066 | .00096 | 5.89e-12 | −.0043 | .00096 | 5.68e-06 |

| T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) | .0038 | .00096 | .000056 | .0015 | .00096 | .10 |

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) | .0038 | .00096 | .00008 | .0026 | .00095 | .0053 |

| CD40L receptor (CD40) | −.0037 | .00096 | .00010 | −.0038 | .00096 | .000058 |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) | −.0036 | .00096 | .00016 | −.0040 | .0017 | .021 |

| Caspase-8 (CASP-8) | −.0035 | .00095 | .00018 | −.0036 | .00095 | .00016 |

| Eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) | .0033 | .00096 | .00061 | .0021 | .00096 | .023 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | .0032 | .00096 | .00074 | .00098 | .00096 | .30 |

| C-X-C motif chemokine 1 (CXCL1) | .0030 | .00096 | .0014 | .0012 | .00096 | .18 |

| Growth/differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) | .0030 | .00097 | .0015 | .000022 | .00097 | .98 |

| Stem cell factor (SCF) | −.0030 | .00096 | .0017 | −.00066 | .00096 | .48 |

| Pappalysin-1 (PAPPA) | −.0030 | .00097 | .0017 | −.0029 | .00097 | .0025 |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | .0028 | .00096 | .0035 | .00092 | .00096 | .33 |

| CD40 ligand (CD40L) | −.0026 | .00096 | .0054 | −.0037 | .00095 | .000073 |

| Osteoprotegerin (OPG) | .00269 | .00097 | .0054 | .0015 | .00097 | .10 |

| Heat shock 27 kDa protein (HSP 27) | −.0024 | .00095 | .0090 | −.0037 | .00095 | .000086 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) | .0024 | .00095 | .010 | .0010 | .00095 | .25 |

| Thrombomodulin (TM) | −.0023 | .00096 | .015 | −.0033 | .00096 | .00047 |

| Follistatin (FS) | .0023 | .00096 | .015 | −.00083 | .00096 | .38 |

In the secondary meta-analysis including all samples, seven proteins showed p<0.00058 (Bonferroni-adjustment) vs IMT-CCA for the age- and sex-adjusted analysis and p<0.05 after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (Supplemental Table III). Of those, Matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) was the only protein not being identified by the above mentioned discovery/validation approach.

Proteins vs Plaque

After age- and sex adjustment, 13 proteins were found to be associated with plaque occurrence (Table 3 and Supplemental Table IV). Of those, 12 proteins showed FDR<5% at the replication stage. Further adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors rendered 3 proteins no longer significant, which left 9 proteins. MMP-12 showed a strong positive relationship also with plaque occurrence. In addition, growth/differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) was replicated at a positive direction of effect.

Table 3. Relationships between cardiovascular proteins and prevalent plaque.

Thirteen proteins were identified in the discovery phase and were evaluated in the validation step. This table show the 12 proteins with FDR<5% in the validation step following adjustment for age and sex. Also data following further adjustment for cardiovascular (CV) risk factors are shown. The betas are the log odds ratios. We demanded the multiple-adjusted p-value to be <0.05 in order to claim that the relationship between a protein and an outcome was significant.

| Age and sex-adjusted | Also adjusted for CV risk factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Beta | SE | p-value | Beta | SE | p-value |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) | .25 | .031 | 5.58e-16 | .20 | .03 | 5.12e-10 |

| Growth/differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) | .21 | .034 | 6.86e-10 | .16 | .038 | 9.16e-06 |

| T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) | .15 | .030 | 5.54e-07 | .11 | .033 | .00046 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | .13 | .030 | .000013 | .10 | .032 | .0020 |

| Urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor (U-PAR) | .12 | .03 | .000034 | .095 | .031 | .0025 |

| TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2 (TRAIL-R2) | .11 | .032 | .00032 | .094 | .034 | .0060 |

| Lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) | .10 | .030 | .00051 | .072 | .032 | .024 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-10 (MMP-10) | .095 | .029 | .0010 | .0797 | .03 | .0094 |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | .091 | .030 | .0024 | .048 | .033 | .14 |

| Stem cell factor (SCF) | −.086 | .029 | .0035 | −.028 | .031 | .37 |

| Leptin (LEP) | −.094 | .034 | .0056 | −.157 | .047 | .00095 |

| Galanin peptides (GAL) | −.070 | .030 | .020 | −.021 | .032 | .51 |

In the secondary meta-analysis including all samples, sixteen proteins showed p<0.00058 (Bonferroni-adjustment) vs plaque for the age- and sex-adjusted analysis and p<0.05 after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (Supplemental Table V). Of those, renin was the top ranked protein not being identified by the above mentioned discovery/validation approach.

Overlap of findings for IMT-CCA vs plaque

As seen in Figure 2, only MMP-12 was significantly related to both IMT-CCA and plaque occurrence. GAL, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP), CD40L receptor (CD40), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), caspase-8 (CASP-8), eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), pappalysin-1 (PAPPA), CD40 ligand (CD40L), heat shock 27 kDa protein (HSP 27) and thrombomodulin (TM) were significantly related to IMT-CCA only whereas GDF-15, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor (U-PAR), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2 (TRAIL-R2), lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1), matrix metalloproteinase-10 (MMP-10) and leptin (LEP) were significantly associated with plaque only.

Figure 2. Venn diagram of validated findings for proteins vs intima-media thickness.

in the common carotid artery (IMT-CCA) or plaque or incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke).

Step 2:

Mendelian randomization for IMT-CCA and plaque

NT-proBNP showed evidence of causality on IMT-CCA (natriuretic peptides B (NPPB), p=4.4 × 10−5, Supplemental Table VI) whereas no other protein met the thresholds set for statistical significance. The causal estimate for NT-proBNP was negative, which contrasts the reported observational relationship between NT-proBNP plasma levels and IMT-CCA. The addition of trans-pQTLs in the MR models did not yield any significant causal estimates. No significant causal estimates were seen for plaque occurrence (Supplemental Table VII). When the 8 independent SNPs being GWAS significant for IMT were used as instrument vs NT-proBNP levels, no evidence for a causal role of IMT on NT-proBNP levels was found (IVW estimate 0.97, SE 1.54, p-value=0.52, MR Egger estimate −2.9, SE 8.7, p-value=0.75).

Step 3:

Proteins and incident atherosclerotic disease

Identification of proteins associated with incident cardiovascular events was based on 754 incident cases in the MDC study (median follow-up 23 years) with replication based on 433 cases from the meta-analysis of 4 studies (see Supplemental Table VIII for details on follow-up).

A total of 37 proteins were associated with cardiovascular events in MDC (Supplemental Table IX), of which 31 were replicated (FDR<0.05) using the age and sex-adjusted model and 17 were replicated after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationships between cardiovascular proteins and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (either myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke).

37 proteins were identified in the discovery phase and were evaluated in the validation step. This table only show the 31 proteins with FDR<5% in the validation meta-analysis following adjustment for age and sex. Also data following further adjustment for cardiovascular (CV) risk factors are shown. HR= hazard ratio. We demanded the multiple-adjusted p-value to be <0.05 in order to claim that the relationship between a protein and an outcome was significant.

| Age and sex-adjusted | Also adjusted for CV risk factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | HR | 95%CI lower | 95%CI higher | p-value | HR | 95%CI lower | 95%CI higher | p-value |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12) | 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.49 | 3.61e-10 | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.35 | .00014 |

| Growth/differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15) | 1.35 | 1.22 | 1.49 | 3.98e-09 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 1.35 | .0011 |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.37 | 2.03e-07 | 1.15 | 1.04 | 1.27 | .0047 |

| TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2 (TRAIL-R2) | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.38 | 6.89e-07 | 1.19 | 1.07 | 1.32 | .0014 |

| Cystatin-B (CSTB) | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.38 | 9.77e-07 | 1.15 | 1.04 | 1.27 | .0059 |

| Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IL-1RA) | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.39 | 1.04e-06 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.25 | .050 |

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro-BNP) | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.35 | 1.22e-06 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 1.34 | 8.50e-06 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.37 | 4.67e-06 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 1.29 | .0020 |

| Urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor (U-PAR) | 1.24 | 1.12 | 1.37 | .000028 | 1.14 | 1.03 | 1.26 | .014 |

| Fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4) | 1.21 | 1.11 | 1.33 | .000033 | 1.10 | .98 | 1.23 | .11 |

| T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1 (TIM-1) | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.35 | .000039 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.25 | .026 |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) | 1.22 | 1.11 | 1.35 | .000069 | 1.08 | .96 | 1.20 | .19 |

| Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) | 1.20 | 1.10 | 1.32 | .00011 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.24 | .019 |

| Adrenomedullin (AM) | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.37 | .00011 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 1.25 | .044 |

| Lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) | 1.21 | 1.10 | 1.33 | .00014 | 1.40 | 1.26 | 1.55 | 1.47e-10 |

| Interleukin-8 (IL-8) | 1.18 | 1.08 | 1.29 | .00015 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.23 | .020 |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 (TNF-R2) | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.32 | .00023 | 1.13 | 1.02 | 1.26 | .016 |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (TNF-R1) | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.33 | .00027 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.24 | .032 |

| Leptin (LEP) | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.37 | .00053 | 1.07 | .92 | 1.24 | .36 |

| Follistatin (FS) | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.31 | .00066 | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.23 | .045 |

| C-C motif chemokine 3 (CCL3) | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.27 | .00078 | 1.11 | 1.01 | 1.22 | .038 |

| Cathepsin D (CTSD) | 1.17 | 1.07 | 1.29 | .0011 | 1.04 | .94 | 1.15 | .49 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) | 1.14 | 1.05 | 1.24 | .0023 | 1.06 | .97 | 1.16 | .16 |

| Placenta growth factor (PlGF) | 1.16 | 1.05 | 1.27 | .0027 | 1.09 | .99 | 1.20 | .080 |

| Tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 14 (TNFSF14) | 1.16 | 1.05 | 1.28 | .0043 | 1.06 | .95 | 1.18 | .30 |

| Resistin (RETN) | 1.14 | 1.04 | 1.26 | .0071 | 1.10 | .99 | 1.22 | .073 |

| Tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) | 1.15 | 1.04 | 1.27 | .0075 | 1.04 | .93 | 1.15 | .49 |

| Osteoprotegerin (OPG) | 1.14 | 1.03 | 1.26 | .011 | 1.08 | .97 | 1.20 | .14 |

| C-C motif chemokine 20 (CCL20) | 1.12 | 1.03 | 1.22 | .011 | 1.08 | .98 | 1.19 | .13 |

| Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) | 1.13 | 1.03 | 1.25 | .014 | 1.07 | .97 | 1.19 | .18 |

| Interleukin-18 (IL-18) | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.24 | .018 | 1.05 | .95 | 1.16 | .33 |

In the secondary meta-analysis including all samples, twenty-five proteins showed p<0.00058 (Bonferroni-adjustment) vs incident atherosclerotic disease for the age- and sex-adjusted analysis and p<0.05 after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (Supplemental Table X). Of those, interleukin −6 (IL-6) was the top ranked protein not being identified by the above mentioned discovery/validation approach.

Mendelian randomization for coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke

The 17 proteins associated with incident events were tested for causality using MR with CAD and IS as outcome traits. MMP-12 was found to be inversely causal in ischemic stroke using either the model based on cis-pQTLs only (p=5.5 × 10−7) or the model using both cis- and trans-pQTLs as instrumental variables. Whilst the estimate of MMP-12 on CAD did not attain corrected statistical significance, a trend towards inverse causality was noted, similar to IS. (Supplemental Tables XI and XII)

DISCUSSION

Main findings

In the present investigation, we tested the association of 86 cardiovascular proteins with carotid artery plaque, IMT, and incident atherosclerotic events, and assessed their potential causal role in IMT-CCA and risk of IS and CAD using MR. Seven proteins showed association with both carotid artery plaque and incident atherosclerotic disease, although only MMP-12 was related to IMT-CCA, as well as to plaque and incident atherosclerotic disease with a positive direction of the effect. Mendelian randomization analyses showed that MMP-12 is inversely causal in IS, which contrasts our observational data for plaque, IMT-CCA and incident cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, also a previous study showed that MMP-12 was inversely causal in CAD23. Thus, our observational studies on MMP-12 levels in relation to atherosclerosis, suggest that the increased levels of MMP-12 could be a consequence of atherosclerotic burden rather than the opposite chain of events.

Proteins vs IMT-CCA and plaque

While the 92 proteins on the CVD-I panel were selected for potential cardiovascular relevance, the selection was based on multiple criteria including experimental data in preclinical models and in vitro. Many of the proteins had no prior association with cardiovascular events in human studies. However, most of the proteins that were identified in the present study have previously been linked to carotid atherosclerosis in humans, such as MMP-1210, MMP-1024, NT-proBNP25, CD40 ligand26, MCP-127, ECP28, PAPPA29, HSP2730, TM31, LOX-132, GDF-1510, TIM-110, IL-633, U-PAR34 and LEP35. To the best of our knowledge, no such links with human carotid atherosclerosis in the population have been published for GAL, CD40, CASP-8, and TRAIL-R2.

TRAIL-R2 is one of the receptors for the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), a protein known to be involved in apoptosis. TRAIL has been shown to induce apoptosis and upregulation of inflammatory genes in endothelial cells36. When TRAIL was knocked out in an atherosclerosis prone background in mice, an increased calcification was found37, and in patients with chronic renal failure, low levels of TRAIL were related to an accelerated plaque progression over 2 years38. However, we did not find TRAIL-R2 levels to be causally related to carotid atherosclerosis or atherosclerotic events.

Galanine peptides is a family with diverse actions spanning from neurotransmission to effects on metabolism, energy homeostasis, inflammation, immunity, and bone formation, as reviewed by Lang et al39. We could not find any published link with atherosclerosis, and our data did not support a casual role for galanin peptides in the atherosclerosis process.

CD40L is involved in adhesion molecule expression on endothelial cells, as well as activation of platelets, two major steps in atherosclerosis and subsequent clot formation40. Elevated levels of CD40L have also been linked to occlusive carotid artery disease in humans26. However, we did not find CD40L levels to be causally related to carotid atherosclerosis or atherosclerotic events.

CASP-8 is mainly known as for signaling of apoptosis and cell death. However, as reviewed by Keller et al, CASP-8 is also involved in cell adhesion and migration by its proteolytic activity41. However, our data did not support a casual role for CASP-8 in the atherosclerosis process.

At first sight it looks surprising that some proteins are related to plaque occurrence, while other proteins are related to IMT-CCA. Only MMP-12 was significantly related to both of these measures of atherosclerosis. However, atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries often starts in the bulb, and not in CCA, although it could well later expand to also include the CCA part of the carotid artery. Previous observational studies have shown that IMT in the CCA mainly is associated with hypertension and stroke, but IMT in the bulb, on the other hand, mainly was related with coronary heart disease and its risk factors42. Furthermore, genes known to be related to coronary atherosclerosis were associated with carotid plaques and IMT of the bulb, as expected, not to IMT-CCA19. In addition, we have previously found that IMT in the bulb was more closely related to future atherosclerotic events compared to IMT-CCA11, further exemplifying that measurement of plaque and IMT-CCA partly represent different cardiovascular phenotypes. From that perspective it is not surprising that we found that several of the proteins are related to only one of these two indices of carotid atherosclerosis

Mendelian randomization for IMT-CCA and plaque

In the Mendelian randomization study for IMT-CCA and plaque, we used a fairly arge study on protein QTLs and primarily used SNPs being located in or close to the gene encoding the protein of interest (cis protein QTLs) to avoid pleiotropy of the chosen instruments. We also used a large GWAS on IMT-CCA and plaque3. The only cis-protein QTL resulting in a significant causal estimate was found for rs198389, adjacent to the BNP gene, NPPB. The Wald ratio estimate for IMT-CCA was negative, which is opposite of what would be expected from our observational data on showing a positive relationship between NT-proBNP and IMT-CCA. The A allele of the NT-pro-BNP protein QTL has previously been linked to lower BNP levels in the Jackson Heart Study43, and we have previously shown that NT-proBNP levels, measured using Olink PEA, were associated with incident stroke in a positive fashion in the PIVUS and ULSAM studies44. These results were also in line with a large meta-analysis that measured NT-proBNP using a conventional ELISA45.

NT-proBNP is a prohormone and the function of its product BNP is to increase natriuresis and thereby reduce plasma volume, blood pressure and cardiac strain. It has been shown that individuals with SNPs associated with low NT-proBNP have higher blood pressure, perhaps due to a lower capacity to eliminate sodium from the circulation46. Hypertension is the major cause of media-thickening and IMT-CCA. This could explain why SNPs associated with low NT-proBNP are associated high IMT-CCA, while positive relationships are found between circulating NT-proBNP and IMT-CCA. However, when we evaluated if IMT was causally related to NT-proBNP levels using the bidirectional MR approach, no such significant causal effect was seen. It must however be emphasized that the instrumental strength for IMT was poor compared to that of NT-proBNP (R2= 0.0041 for the IMT instrument and R2=0.023 for the NT-proBNP instrument). With such poor R2 as seen for IMT, it is generally very hard to achieve significant findings in a MR analysis.

Proteins and incident atherosclerotic disease

Higher MMP-12 levels were not only related to both IMT-CCA and plaque, but also to incident cardiovascular events. We have previously shown that high levels of this metalloprotease are linked to IMT-CCA11, and others have shown its association to future cardiovascular disease47. Since MMP-12, and other proteases, are involved in the integrity of the collagen-rich fibrous cap of the plaque, the links to IMT-CCA, plaque, and overt ischemic disease are plausible.

We also replicated the association of six other proteins with cardiovascular events and showed association with plaque occurrence, but not to IMT.

Nine proteins were related to incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but not to IMT-CCA or to plaque. Plaques in themselves generally do not induce acute coronary syndromes. A thrombus formation is also needed, usually proceeded by plaque rupture. The mechanisms involved with plaque formation may be different from those involved in plaque rupture and thrombus formation. In addition, many thrombi are dissolved by the endogenous fibrinolytic system and thereby does not cause overt acute disease. It may well be that the nine proteins being related to incident atherosclerotic disease, but not to atherosclerosis, are involved in plaque rupture, thrombus formation or a defect fibrinolysis. None of those proteins are new findings when considering cardiovascular events.

Mendelian randomization for incident atherosclerotic disease

MMP-12 belongs to a large group of metalloproteases that are known to be secreted from immunocompetent cells, as well as being expressed in vascular tissue, as reviewed by Myasoedova et al48. They are endopeptidases that process various parts of the extracellular matrix and has as a group been shown to be involved in all stages in the atherosclerotic process. MMP-12 is considered a metalloelastase, and ApoE/MMP-12 double knock-out mice show reduced lesion size, as well as increased content of smooth muscle cells and reduced macrophage content in the lesions49, suggesting a role deleterious role for MMP-12 in both lesion formation and plaque stability.

In observational studies it has been shown that MMP-12 levels are related to both the amount of atherosclerosis10, 47, 50, 51, as well as to incident atherosclerotic events in different samples10, 47, 50. It has furthermore been reported that a high content of MMP-12 in macrophages in plaque is linked to incident CVD52. Thus, both experimental and human observational data points towards a deleterious role of MMP-12 in atherosclerosis.

It was therefore a surprise that genetically determined MMP-12 was inversely related to ischemic stroke in the MR-analysis in the present study. This could be a false positive finding despite the thorough correction of the p-value for multiple testing, but the finding of a similar inverse relationship in an MR-analysis of MMP-12 vs coronary heart disease23 support the view that our MR result is not only a chance finding. It cannot be excluded that MMP-12 is upregulated to compensate for pro-atherogenic processes during early atherogenesis, and that individuals with reduced capacity to synthesize MMP-12 therefore have increased cardiovascular risk. This could possibly explain the seemingly contradictive result of the MR analysis compared to the observational association between MMP-12 and incident cardiovascular events. However, future studies with MMP-12 activity modulating drugs are needed to solve this matter.

As with the NT-proBNP vs IMT relationship, we evaluated if ischemic stroke was casually related to MMP-12 levels using MR analysis in the recently published paper from the SCALLOP consortium12. However, we had the same problem with a poor power of the instrument for ischemic stroke compared to that of MMP-12 (R2=0.0053 for the ischemic stroke instrument and R2=0.13 for the MMP-12 instrument), so it was not a surprise that we did not find ischemic stroke to be causally related to MMP-12 levels (p-value=0.35).

Strength and limitations

The strengths of the present study are the large sample size obtained by the meta-analysis, the use of a discovery/validation approach in independent samples to minimize the risk of false positive findings, together with the use of MR to assess causality. Also the uniform measurements of the protein chip should increase the chances of accurate findings.

It should however be pointed out that despite the fact that fairly large samples were used in the MR analysis, the limiting factor is usually the strength of the genetic instruments for the plasma protein levels as well as outcomes, and therefore true minor casual effects of some proteins cannot be excluded. Another limitation is that all samples mainly consisted of Caucasians, so these results have to be confirmed in other ethnic groups.

As could be seen in Table 1, the time of collection of plasma for protein analysis differed between studies. Since time in freezer might affect protein levels, this fact might have had an impact on the results. However, such an increased variation in protein measurements could only drive the statistical analyses towards the null hypothesis and would not produce any false positive findings.

In accordance with our previous papers on proteins vs stroke and atrial fibrillation44, 53, we regard the discover/validation approach in different samples as the main analysis, since replication in an independent sample is a valid way to minimize the number of false positive findings. In addition, to maximize the power, we also performed a secondary meta-analysis including all samples. It should however be remembered that those results are not replicated and therefore must be taken with caution.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis discovered several proteins related to carotid atherosclerosis that partly differed in their association with IMT-CCA, plaque, and incident atherosclerotic disease. Mendelian randomization analysis for the top finding, MMP-12, suggest that the increased levels of MMP-12 could be a consequence of atherosclerotic burden rather than the opposite chain of events.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Intima-media thickness in the common carotid artery (IMT-CCA), plaque occurrence, and incident cardiovascular events were related to 86 proteins.

Seven studies with >11,000 individuals were used.

Only MMP-12 was associated with IMT-CCA, plaque, and incident events with a positive effect.

Mendelian randomization analysis suggested that increased MMP-12 is protective against ischemic stroke

Increased levels of MMP-12 could be a consequence of atherosclerotic burden rather than the opposite.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

The PIVUS study was supported by the Uppsala University Hospital and the Swedish Heart and Lung foundation.

The MDC study was supported by the Swedish research council and the Swedish Heart and Lung foundation.

The IMPROVE study was supported by the Swedish research council, the Swedish Heart and Lung foundation, Stockholm County Council (ALF), and by an EU grant.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMI

body mass index

- CARDIPP

Cardiovascular Risk in Type 2 Diabetes - A Prospective Study in Primary Care

- CASP-8

caspase-8

- CD40

CD40L receptor

- CD40L

CD40 ligand

- ECP

eosinophil cationic protein

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GAL

galanin

- GDF-15

growth/differentiation factor 15

- HSP 27

heat shock 27 kDa protein

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IMPROVE

Carotid IMT and IMT-Progression as Predictors of Vascular Events in a High Risk European Population

- IMT-CCA

intima-media thickness in the common carotid artery

- IS

ischemic stroke

- IVW

inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect meta-analysis

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- LEP

leptin

- LOX-1

lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein 1

- MDC

the Malmö Diet and Cancer study

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MMP-10

matrix metalloproteinase-10

- MMP-12

matrix metalloproteinase-12

- MR

Mendelian Randomization

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- pQTL

protein quantitative trait loci

- PAPPA

pappalysin-1

- PADVA

the Peripheral Arterial Disease in Vastmanland study

- PIVUS

the Prospective Investigation of Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors study

- POEM

the Prospective investigation of Obesity, Energy and Metabolism study

- SAVA

Study of Atherosclerosis in Vastmanland

- TIM-1

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain 1

- TM

thrombomodulin

- TRAIL-R2

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 2

- U-PAR

urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Polak JF, Shemanski L, O’Leary DH, Lefkowitz D, Price TR, Savage PJ, Brant WE, Reid C. Hypoechoic plaque at US of the carotid artery: an independent risk factor for incident stroke in adults aged 65 years or older. Cardiovascular Health Study. Radiology. 1998;208:649–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lorenz MW, Polak JF, Kavousi M, Mathiesen EB, Völzke H, Tuomainen TP, Sander D, Plichart M, Catapano AL, Robertson CM, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness progression to predict cardiovascular events in the general population (the PROG-IMT collaborative project): a meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;379:2053–2062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franceschini N, Giambartolomei C, de Vries PS, Finan C, Bis JC, Huntley RP, Lovering RC, Tajuddin SM, Winkler TW, Graff M, et al. GWAS and colocalization analyses implicate carotid intima-media thickness and carotid plaque loci in cardiovascular outcomes. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess S, Bowden J, Fall T, Ingelsson E, Thompson SG. Sensitivity Analyses for Robust Causal Inference from Mendelian Randomization Analyses with Multiple Genetic Variants. Epidemiology. 2017;28:30–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dittrich J, Beutner F, Teren A, Thiery J, Burkhardt R, Scholz M, Ceglarek U. Plasma levels of apolipoproteins C-III, A-IV, and E are independently associated with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2019;281:17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhosale SD, Moulder R, Venäläinen MS, Koskinen JS, Pitkänen N, Juonala MT, Kähönen MAP, Lehtimäki TJ, Viikari JSA, Elo LL, et al. Serum Proteomic Profiling to Identify Biomarkers of Premature Carotid Atherosclerosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pleskovič A, Letonja MS, Vujkovac AC, Nikolajević Starčević J, Gazdikova K, Caprnda M, Gaspar L, Kruzliak P, Petrovič D. C-reactive protein as a marker of progression of carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Vasa. 2017;46:187–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Fang X, Hua Y, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Gu X, Wu X, Tang Z, Guan S, Liu H, et al. Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 and Risk of Carotid Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Events in Community-Based Older Adults in China. Angiology. 2018;69:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie W, Liu J, Wang W, Wang M, Qi Y, Zhao F, Sun J, Liu J, Li Y, Zhao D. Association between plasma PCSK9 levels and 10-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis beyond LDL-C: A cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind L, Ärnlöv J, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, Sundström J, Ingelsson E. Use of a proximity extension assay proteomics chip to discover new biomarkers for human atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242:205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lind L, Gigante B, Borne Y, Mälarstig A, Sundström J, Ärnlöv J, Ingelsson E, Baldassarre D, Tremoli E, Veglia F, et al. The plasma protein profile and cardiovascular risk differ between intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery and the bulb: A meta-analysis and a longitudinal evaluation. Atherosclerosis. 2020;295:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkersen L, Gustafsson S, Wang Q, Hansen DH, Hedman Å K, Schork A, Page K, Zhernakova DV, Wu Y, Peters J, et al. Genomic and drug target evaluation of 90 cardiovascular proteins in 30,931 individuals. Nat Metab. 2020;2:1135–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamrefors V, Hedblad B, Engström G, Almgren P, Sjögren M, Melander O. A myocardial infarction genetic risk score is associated with markers of carotid atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 2012;271:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lind L, Fors N, Hall J, Marttala K, Stenborg A. A comparison of three different methods to evaluate endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the elderly: the Prospective Investigation of the Vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2368–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lind L, Strand R, Michaëlsson K, Ahlström H, Kullberg J. Voxel-wise Study of Cohort Associations in Whole-Body MRI: Application in Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components. Radiology. 2020;294:559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldassarre D, Hamsten A, Veglia F, de Faire U, Humphries SE, Smit AJ, Giral P, Kurl S, Rauramaa R, Mannarino E, et al. Measurements of carotid intima-media thickness and of interadventitia common carotid diameter improve prediction of cardiovascular events: results of the IMPROVE (Carotid Intima Media Thickness [IMT] and IMT-Progression as Predictors of Vascular Events in a High Risk European Population) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1489–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahlén EM, Länne T, Engvall J, Lindström T, Grodzinsky E, Nyström FH, Östgren CJ. Carotid intima-media thickness and apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-I ratio in middle-aged patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26:384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedberg P, Hammar C, Selmeryd J, Viklund J, Leppert J, Hellberg A, Henriksen E. Left ventricular systolic dysfunction in outpatients with peripheral atherosclerotic vascular disease: prevalence and association with location of arterial disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:625–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Hoed M, Strawbridge RJ, Almgren P, Gustafsson S, Axelsson T, Engström G, de Faire U, Hedblad B, Humphries SE, Lindgren CM, et al. GWAS-identified loci for coronary heart disease are associated with intima-media thickness and plaque presence at the carotid artery bulb. Atherosclerosis. 2015;239:304–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G, Björkesten J, Thorsen SB, Ekman D, Eriksson A, Rennel Dickens E, Ohlsson S, Edfeldt G, et al. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, Hall LM, Willenborg C, Kanoni S, Saleheen D, Kyriakou T, Nelson CP, Hopewell JC, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 Genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1121–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malik R, Chauhan G, Traylor M, Sargurupremraj M, Okada Y, Mishra A, Rutten-Jacobs L, Giese AK, van der Laan SW, Gretarsdottir S, et al. Multiancestry genome-wide association study of 520,000 subjects identifies 32 loci associated with stroke and stroke subtypes. Nat Genet. 2018;50:524–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Burgess S, Jiang T, Paige E, Surendran P, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orbe J, Montero I, Rodríguez JA, Beloqui O, Roncal C, Páramo JA. Independent association of matrix metalloproteinase-10, cardiovascular risk factors and subclinical atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pastormerlo LE, Maffei S, Latta DD, Chubuchny V, Susini C, Berti S, Clerico A, Prontera C, Passino C, Januzzi JL Jr., et al. N-terminal prob-type natriuretic peptide is a marker of vascular remodelling and subclinical atherosclerosis in asymptomatic hypertensives. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:366–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balla J, Magyar MT, Bereczki D, Valikovics A, Nagy E, Barna E, Pál A, Balla G, Csiba L, Blaskó G. Serum levels of platelet released CD40 ligand are increased in early onset occlusive carotid artery disease. Dis Markers. 2006;22:133–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson PT, Hallerstam S, Rosfors S, Wallén NH. Circulating markers of inflammation are related to carotid artery atherosclerosis. Int Angiol. 2005;24:43–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundström J, Söderholm M, Borné Y, Nilsson J, Persson M, Östling G, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, Engström G. Eosinophil Cationic Protein, Carotid Plaque, and Incidence of Stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:2686–2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woelfle J, Roth CL, Wunsch R, Reinehr T. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A in obese children: relationship to markers and risk factors of atherosclerosis and members of the IGF system. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:613–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Ventura JL, Duran MC, Blanco-Colio LM, Meilhac O, Leclercq A, Michel JB, Jensen ON, Hernandez-Merida S, Tuñón J, Vivanco F, et al. Identification by a differential proteomic approach of heat shock protein 27 as a potential marker of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;110:2216–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahran M, Nasr FM, Metwaly AA, El-Sheikh N, Khalil NS, Harba T. The Role of Hemostatic Factors in Atherosclerosis in Patients with Chronic Renal Disease. Electron Physician. 2015;7:1270–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markstad H, Edsfeldt A, Yao Mattison I, Bengtsson E, Singh P, Cavalera M, Asciutto G, Björkbacka H, Fredrikson GN, Dias N, et al. High Levels of Soluble Lectinlike Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-1 Are Associated With Carotid Plaque Inflammation and Increased Risk of Ischemic Stroke. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e009874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eltoft A, Arntzen KA, Wilsgaard T, Mathiesen EB, Johnsen SH. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of progressive atherosclerosis in the carotid artery: The Tromso Study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;271:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Persson M, Östling G, Smith G, Hamrefors V, Melander O, Hedblad B, Engström G. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor: a risk factor for carotid plaque, stroke, and coronary artery disease. Stroke. 2014;45:18–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciccone M, Vettor R, Pannacciulli N, Minenna A, Bellacicco M, Rizzon P, Giorgino R, De Pergola G. Plasma leptin is independently associated with the intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:805–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li JH, Kirkiles-Smith NC, McNiff JM, Pober JS. TRAIL induces apoptosis and inflammatory gene expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:1526–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Bartolo BA, Cartland SP, Harith HH, Bobryshev YV, Schoppet M, Kavurma MM. TRAIL-deficiency accelerates vascular calcification in atherosclerosis via modulation of RANKL. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arcidiacono MV, Rimondi E, Maietti E, Melloni E, Tisato V, Gallo S, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E, Betriu À, Voltan R, et al. Relationship between low levels of circulating TRAIL and atheromatosis progression in patients with chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0203716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang R, Gundlach AL, Holmes FE, Hobson SA, Wynick D, Hökfelt T, Kofler B. Physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of galanin peptides and receptors: three decades of emerging diversity. Pharmacol Rev. 2015;67:118–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Büchner K, Henn V, Gräfe M, de Boer OJ, Becker AE, Kroczek RA. CD40 ligand is selectively expressed on CD4+ T cells and platelets: implications for CD40-CD40L signalling in atherosclerosis. J Pathol. 2003;201:288–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller N, Ozmadenci D, Ichim G, Stupack D. Caspase-8 function, and phosphorylation, in cell migration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;82:105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ebrahim S, Papacosta O, Whincup P, Wannamethee G, Walker M, Nicolaides AN, Dhanjil S, Griffin M, Belcaro G, Rumley A, et al. Carotid plaque, intima media thickness, cardiovascular risk factors, and prevalent cardiovascular disease in men and women: the British Regional Heart Study. Stroke. 1999;30:841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Musani SK, Fox ER, Kraja A, Bidulescu A, Lieb W, Lin H, Beecham A, Chen MH, Felix JF, Fox CS, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of plasma B-type natriuretic peptide in blacks: the Jackson Heart Study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8:122–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lind L, Siegbahn A, Lindahl B, Stenemo M, Sundström J, Ärnlöv J. Discovery of New Risk Markers for Ischemic Stroke Using a Novel Targeted Proteomics Chip. Stroke. 2015;46:3340–3347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Natriuretic Peptides Studies C, Willeit P, Kaptoge S, Welsh P, Butterworth AS, Chowdhury R, Spackman SA, Pennells L, Gao P, Burgess S, et al. Natriuretic peptides and integrated risk assessment for cardiovascular disease: an individual-participant-data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4:840–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newton-Cheh C, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Levy D, Bloch KD, Surti A, Guiducci C, Kathiresan S, Benjamin EJ, Struck J, et al. Association of common variants in NPPA and NPPB with circulating natriuretic peptides and blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:348–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goncalves I, Bengtsson E, Colhoun HM, Shore AC, Palombo C, Natali A, Edsfeldt A, Dunér P, Fredrikson GN, Björkbacka H, et al. Elevated Plasma Levels of MMP-12 Are Associated With Atherosclerotic Burden and Symptomatic Cardiovascular Disease in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myasoedova VA, Chistiakov DA, Grechko AV, Orekhov AN. Matrix metalloproteinases in pro-atherosclerotic arterial remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;123:159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson JL, George SJ, Newby AC, Jackson CL. Divergent effects of matrix metalloproteinases 3, 7, 9, and 12 on atherosclerotic plaque stability in mouse brachiocephalic arteries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15575–15580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu W, Wei R, Wang L, Lu J, Liu H, Zhang W. Correlations of MMP-1, MMP-3, and MMP-12 with the degree of atherosclerosis, plaque stability and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15:1994–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraen M, Frantz S, Nihlén U, Engström G, Löfdahl CG, Wollmer P, Dencker M. Matrix Metalloproteinases in COPD and atherosclerosis with emphasis on the effects of smoking. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scholtes VP, Johnson JL, Jenkins N, Sala-Newby GB, de Vries JP, de Borst GJ, de Kleijn DP, Moll FL, Pasterkamp G, Newby AC. Carotid atherosclerotic plaque matrix metalloproteinase-12-positive macrophage subpopulation predicts adverse outcome after endarterectomy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e001040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lind L, Sundström J, Stenemo M, Hagström E, Ärnlöv J. Discovery of new biomarkers for atrial fibrillation using a custom-made proteomics chip. Heart. 2017;103:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.