Abstract

Structural variation in plant genomes is a significant driver of phenotypic variability in traits important for the domestication and productivity of crop species. Among these are traits that depend on functional meristems, populations of stem cells maintained by the CLAVATA-WUSCHEL (CLV-WUS) negative feedback-loop that controls the expression of the WUS homeobox transcription factor. WUS function and impact on maize development and yield remain largely unexplored. Here we show that the maize dominant Barren inflorescence3 (Bif3) mutant harbors a tandem duplicated copy of the ZmWUS1 gene, ZmWUS1-B, whose novel promoter enhances transcription in a ring-like pattern. Overexpression of ZmWUS1-B is due to multimerized binding sites for type-B RESPONSE REGULATORs (RRs), key transcription factors in cytokinin signaling. Hypersensitivity to cytokinin causes stem cell overproliferation and major rearrangements of Bif3 inflorescence meristems, leading to the formation of ball-shaped ears and severely affecting productivity. These findings establish ZmWUS1 as an essential meristem size regulator in maize and highlight the striking effect of cis-regulatory variation on a key developmental program.

Subject terms: Plant stem cell, Shoot apical meristem, Plant genetics

The WUSCHEL transcription factor promotes plant stem cell proliferation. Here the authors show that the maize Bif3 mutant contains a duplication of the ZmWUS1 locus leading to cytokinin hypersensitivity and overproliferation at the shoot meristem demonstrating the role of WUSCHEL in maize and how structural variation can impact plant morphology.

Introduction

The control of plant stem cells is essential for sustaining the function of apical meristems, plant growth, and ultimately productivity1. Stem cells reside at the growing tip of meristems, where they differentiate to produce new organs throughout the life of plant and maintain a constant reservoir of pluripotent stem cells. Stem cell maintenance in the shoot is under the control of the CLAVATA-WUSCHEL (CLV-WUS) negative feedback-loop, which is tightly integrated with hormone function, in particular auxin and cytokinin that promote cell differentiation and proliferation, respectively2. WUS is a homeodomain transcription factor (TF) produced in the organizing center (OC) domain of apical meristems and is transported via plasmodesmata into the apical domain (called central zone, CZ) to promote proliferation of stem cells3. Flanking the CZ is the peripheral zone (PZ) where cells are recruited for the initiation of new lateral primordia. In the CZ, WUS activates the CLV3 gene, encoding a short signaling peptide perceived by a series of leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-receptor-like complexes, among which are complexes containing CLV1 and CLV2. Activation of CLV3 in the OC is prevented by the action of WUS in conjunction with the GRAS-transcription regulators HAIRY MERISTEMs (HAMs)4,5. A distinct ZmFCP1-FEA3 ligand–receptor combination, originally identified in maize, prevents WUS gene expression in the region below the OC (also called rib zone, RZ), thus confining WUS expression within the OC of meristems6.

The molecular architecture of the CLV-WUS pathway is conserved across different plant species7, but individual gene contributions differ and, in some cases, genes acquire distinct functions8,9. In particular, based on studies in rice and Arabidopsis, it is believed that WUS function is not evolutionary conserved between eudicot and monocot species9–11, but this hypothesis is solely based on work carried out in rice. The function of the two uncharacterized maize co-orthologs of WUS, ZmWUS1 and ZmWUS2, is unknown8. Recently, interest in ZmWUS’s stem cell promoting properties has resurfaced due to their use in efficient transformation systems for maize and other recalcitrant plant species12,13.

The regulation of WUS transcription is crucial for meristem homeostasis, whereby high WUS expression leads to enlarged meristems and low expression leads to the formation of small meristems3,14. The phytohormone cytokinin induces WUS expression, and it was recently shown that type-B Arabidopsis response regulators (B-ARRs) directly bind to the WUS proximal promoter region and activate its expression in a cytokinin-dependent fashion15–20.

In this study, by characterization of the dominant maize mutant Barren inflorescence3 (Bif3) we identified a tandem-duplicated copy of ZmWUS1 whose expression is dramatically enhanced by the insertion of a short stretch of chimeric proximal promoter sequence. We showed that this causes striking changes in inflorescence meristem (IM) architecture and leads to extreme stem cell proliferation and the formation of spherical meristems, whereby OC, CZ, and PZ domains become arranged in concentric circles. We determined that multimerized binding sites of type-B RR TFs at the duplicated ZmWUS1 locus are the underlying cause of its ectopic expression and promote cytokinin hypersensitivity. These findings refine the gene-regulatory network of maize meristems placing ZmWUS1 at the center of vegetative and reproductive meristem size regulation, thus enhancing our ability to exploit variation in the CLV-WUS pathway for diverse agricultural traits and for fast and efficient transformation systems.

Results

Bif3 inflorescences show defects in meristem initiation and maintenance

The Barren inflorescence3 (Bif3) mutant was originally isolated in an uncharacterized genetic background. To better evaluate its phenotype, we introgressed the only Bif3 allele available (Bif3-ref) in two different maize inbred lines, A619 and B73. In both genetic backgrounds, the Bif3 mutation severely affected inflorescence architecture, but more so in the A619 background where the mutation showed dominance in ear and semi-dominance in tassel phenotypes. In B73, instead, the mutant phenotype appeared slightly milder, in particular in heterozygous tassels, which showed no obvious change in the number of branches and spikelets, structures that contain florets (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, these plants were male sterile, as were homozygous mutants. The male sterility was not due to a gametophytic effect given that the mutation segregated as expected (X2, 0.75 < p > 0.5, n = 82) and pollen germination rate was unchanged (Supplementary Fig. 1), but very few pollen grains were produced.

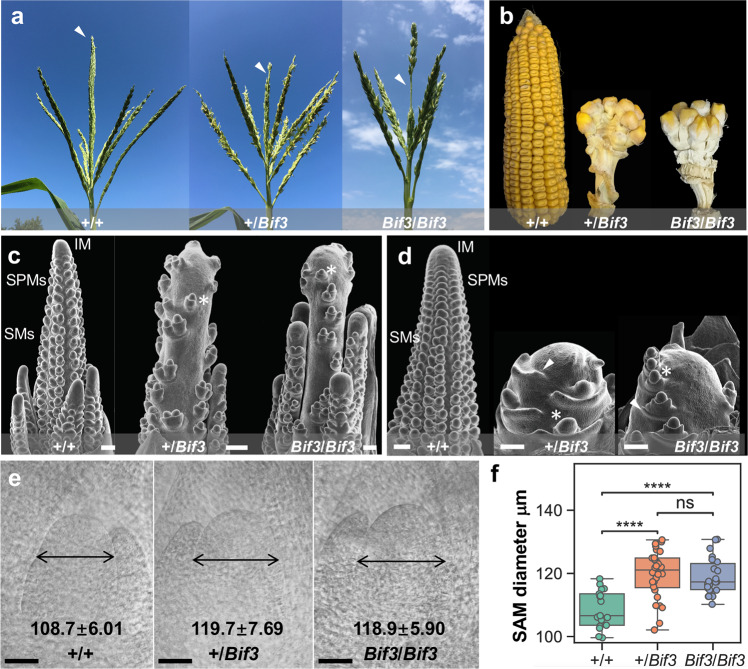

Given that the phenotype was more severe in A619, we carefully analyzed the developmental defects of Bif3 inflorescences in this genetic background. The central spike of heterozygous and homozygous Bif3 tassels was significantly shorter than wild-type (~67% of wild-type length, Student’s t-test p < 0.0001, n ≥ 13), and had several visible barren patches devoid of spikelets (Fig. 1a). Ears, on the other hand, were extremely reduced in size, ball-shaped, and carried only few kernels upon fertilization (Fig. 1b). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of 2–3 mm Bif3 tassel and ear primordia revealed the formation of extremely enlarged IMs, spikelet pair meristems (SPMs) developing on the top of the inflorescence, and single rather than paired spikelet meristems (SMs), with bigger than normal subtending suppressed bracts (Fig. 1c, d). In normal inflorescences, IMs form organized rows of axillary meristems (SPMs and paired SMs) in both inflorescences (Fig. 1c, d). While other mutants with increased IM size (fasciated) produce more axillary meristems (AMs)6,21–26, Bif3 mutants were unique in initiating only a small number of AMs.

Fig. 1. Bif3 mutant phenotypes.

a Normal tassels produce spikelets on branches and central spikes (white arrowheads). Barren patches are observed in Bif3 mutants. b Ball-shaped ear of Bif3 mutants. c, d SEM images of wild-type and Bif3 tassel, and ear primordia. Bif3 mutants show enlarged IMs, a reduced number of SPMs, single SMs (asterisks) and enlarged suppressed bracts (arrowheads). e Cleared shoot apical meristems (SAMs) from wild-type (A619), heterozygous, and homozygous Bif3 plants. The Bif3 SAMs have larger diameter (double-headed arrows). f Quantification of SAM diameter: two-tailed Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001 (n+/+ = 17; n+/Bif3 = 28; nBif3/Bif3 = 22). Box plot center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, maximum and minimum values. Scale bars: 200 μm in (c and d); 50 μm in (e).

To investigate whether other meristems were affected, we also measured vegetative shoot apical meristems (SAMs) in heterozygous and homozygous Bif3 mutants and determined that they were approximately 8% larger than those of wild-type siblings (mean diameter 119.7 ± 7.7 μm and 118.9 ± 5.9 μm, respectively, vs. 108.7 ± 6.0 μm) (Fig. 1e, f). In Bif3 mutants, larger SAMs correlated with leaves that were 20% wider and 12% shorter than wild-type (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, these results indicate that Bif3 has defects in vegetative and reproductive meristem size regulation as well as reproductive AM initiation.

Bif3 is caused by a tandem-duplicated ZmWUS1 gene expressed by a novel chimeric promoter

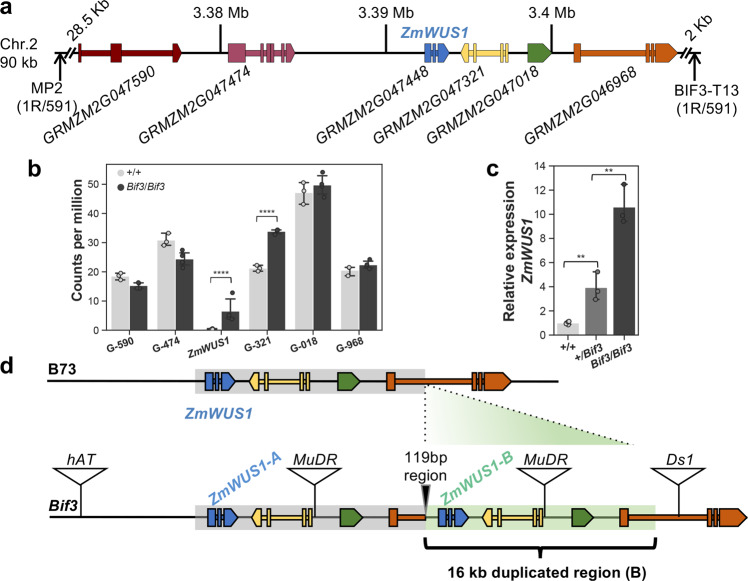

To identify the causal gene, we first mapped the Bif3 locus to a small region of ~90 kb on the top of chromosome 2 that contained six genes including ZmWUS1, one of the maize co-orthologs of the Arabidopsis WUS gene (AtWUS)8 (Fig. 2a). ZmWUS1 encodes a protein of 320 amino acids with 64% identity with AtWUS. By performing RNA-seq analysis of Bif3/Bif3 and wild-type ear primordia (3–4 mm), we subsequently determined that of the six genes within this mapping window, two genes, ZmWUS1 (GRMZM2G047448) and its immediate downstream gene GRMZM2G047321, were differentially expressed in Bif3/Bif3 (16.5-fold and 1.6-fold higher relative to wild-type, respectively; Fig. 2b). Given the enlarged IM phenotype, we concentrated on ZmWUS1 and confirmed its strong up-regulation by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2c). These results suggested that the enhanced expression of ZmWUS1 may cause the Bif3 dominant mutant phenotype.

Fig. 2. Bif3 gene identification.

a Map-based cloning of Bif3 (in parenthesis, number of recombinants R/total chromosomes). b RNA-seq analysis of genes (G) in the mapping window indicates that ZmWUS1 is differentially expressed (fold-change = 13.6); two-tailed Student’s t-test ****p < 0.0001). n+/+ = 3, nBif3/Bif3 = 4 (n pools of three ear samples). Plotted data represent mean ± standard deviation. c qRT-PCR of ZmWUS1 in immature ears; two-tailed Student’s t-test **p < 0.01; n+/+ = 4, n+/Bif3 = 3, nBif3/Bif3 = 3 (n pools of three ear samples). Plotted data represent mean ± standard deviation. d Structure of the tandem-duplicated ZmWUS1 locus in the Bif3 mutant. A 16 kb fragment containing ZmWUS1 was duplicated and inserted in the first intron of GRMZM2G046968. Triangles represent transposon insertions from different families.

To identify the molecular basis of elevated ZmWUS1 expression levels, we conducted a series of PCR and Southern blot analyses that revealed an additional copy of ZmWUS1 (hereafter referred to as ZmWUS1-B to distinguish it from the original copy, ZmWUS1-A) at the Bif3 locus (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2). Using a PCR-based chromosome walking method27, we sequenced both flanking regions of ZmWUS1-B and detected a tandem duplication of a 16 kb fragment containing ZmWUS1-B, the two downstream genes (GRMZM2G047321 and GRMZM2G047018), and a fragment of the third downstream gene GRMZM2G046968 (including promoter, first exon, and partial first intron) (Fig. 2d). The tandem-duplicated ZmWUS1 locus also contained copies of a MuDR transposable element, the autonomous element of the Mutator transposon family28. The 5′ junction of the tandem-duplicated regions contained a novel 119 bp region. While the coding sequences of both copies of the ZmWUS1 gene were identical, the upstream regulatory region of ZmWUS1-B included the original 444 bp proximal promoter region of ZmWUS1, the 119 bp junction sequence, and a partial fragment of the GRMZM2G046968 gene (Fig. 2d). The ZmWUS1-B gene was only present in the Bif3 mutant background, and not in a diverse panel of inbred lines (Supplementary Fig. 2). By sequencing several DNA sequence stretches in the region, we determined that Ki3, a Thai inbred, was very similar, though not identical (~99.1% identity; Supplementary Fig. 3), to the original Bif3 mutant background, suggesting that the Bif3 mutation arose in a closely related tropical line.

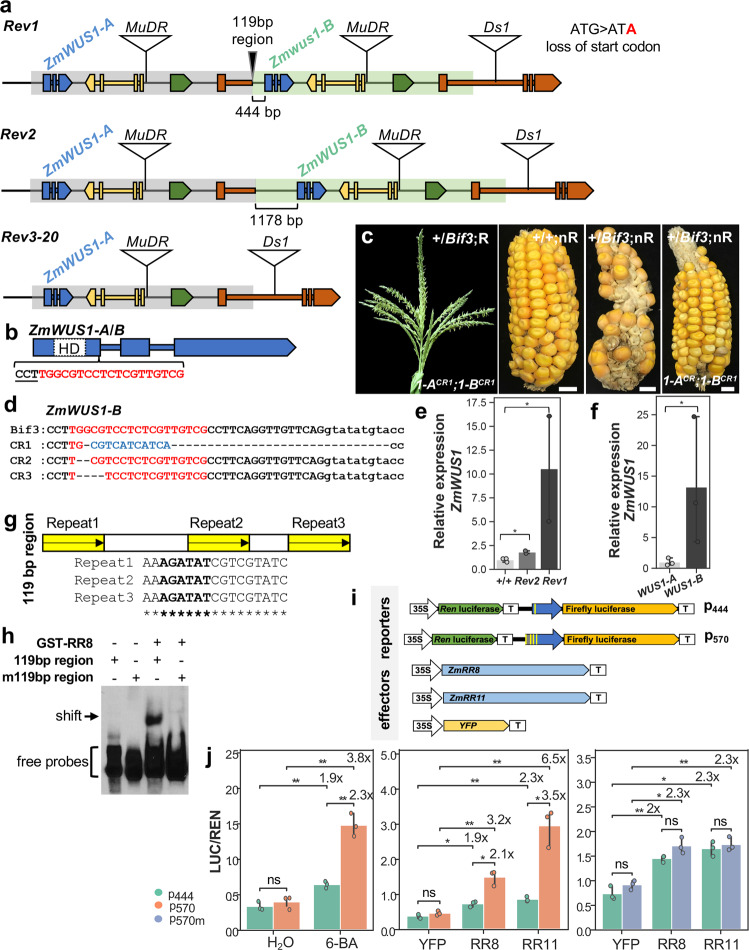

To test whether the overexpression of ZmWUS1 was the cause of the Bif3 mutant phenotype, we performed a targeted ethyl-methane sulfonate (EMS) intragenic suppressor screen in the A619 background, to ask if knock-out mutations in the ZmWUS1 locus could restore a wild-type phenotype (reversion). Pollen from homozygous Bif3 mutants was treated with EMS and used to fertilize ears of wild-type A619. Approximately 10,000 M1 plants were screened and we identified 512 phenotypically wild-type plants (revertants) that were heterozygous for Bif3. The unexpected high frequency of reversion (~100-fold higher than expected29) led us to investigate its nature. We first asked if any of the M1 revertant individuals carried an EMS-induced mutation in ZmWUS1-A or ZmWUS1-B, using a 3D-pooling strategy and next-generation sequencing. This approach identified one revertant individual (Bif3-Rev1) in which the ZmWUS1-B gene carried a G > A point mutation in the start codon (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2). As a consequence of this mutation, the predicted ZmWUS1-B protein lost the N-terminus, including a section of the DNA-binding domain. In other revertants, we first performed PCR on the original pools to determine whether the ZmWUS1-B copy was still present. A small subset of revertants was then characterized by a combination of PCRs and Southern blots. This approach led to the identification of another revertant (Bif3-Rev2) which still carried the ZmWUS1-B gene. However, in this plant ZmWUS1-B contained a longer native promoter (1178 bp proximal promoter instead of 444 bp proximal promoter of ZmWUS1-B) and lost the 119 bp junction region (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2). A subset of other revertants (Bif3-Rev3 to Rev20) were tested with a series of markers designed to distinguish the duplicated regions, and all had lost the ZmWUS1-B duplicated region (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4), presumably by intrachromosomal recombination-based mechanisms30.

Fig. 3. Bif3 is caused by ectopic expression of ZmWUS1-B.

a Bif3 revertants identified from a targeted EMS suppressor screen. Three classes of revertants were identified. Revertant1 (Rev1) carries a G-to-A transition occurred at the start codon ATG of ZmWUS1-B. In revertant2 (Rev2), ZmWUS1-B carries a longer promoter (1178 bp from ATG) and lost the 119 bp region. In other revertants (Rev3–20), ZmWUS1-B is missing. b–d CRISPR-Cas9 targeted ZmWUS1 knock-out in Bif3 mutant. b ZmWUS1 gene structure with homeobox domain (HD in dashed white rectangle) highlighted in the first exon. gRNA in red with PAM site underlined. c The tassel (F1) and ear (BC1) of ZmWUS1-B knock-out plants (A619 background). nR, non-resistant to herbicide treatment, R, resistant to herbicide treatment. Scale bars: 1 cm. d CRISPR-Cas9 edits in ZmWUS1-B. gRNA targeted sequence in red. In blue, insertion sequence. e, f qRT-PCR of ZmWUS1 transcripts in wild-type, Rev2, and Rev1 (e) and of ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B in Rev1 by copy-specific primers based on the G/A SNP (f). Two-tailed Student’s t-test *p < 0.05. n+/+ = 3, nREV1 = 2, nREV2 = 2, nWUS1-A = 3, nWUS1-B = 3 (n independent experiments). g The unique 119 bp region of ZmWUS1-B contains three direct repeats. Yellow boxes with arrow indicate repeat units, and each repeat unit contains the AGATAT motif. h Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with ZmRR8. m119 bp region carries mutations in all repeats. i, j Transient transactivation in maize protoplasts. i Reporter and effector constructs used. The Firefly luciferase is driven by the proximal promoter of ZmWUS1-B (blue arrows), including 444 bp (p444) or 570 bp (p570) including the 119 bp region. The Renilla (Ren) luciferase is used for normalization. j ZmWUS1-B is induced by cytokinin treatments (6-BA), and by type-B ZmRR8 and ZmRR11. Two-tailed Student’s t-test *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. p570m, 570 bp proximal promoter with AGATAT motifs mutated into TTTTTT. Plotted data represent mean ± standard deviation. Three replicates for each experiment.

To unequivocally show that the loss of ZmWUS1-B function rescued the mutant phenotype, we used a CRISPR-Cas9 strategy to knock out ZmWUS1 in Bif3 mutants. A transgenic construct containing a gRNA targeting the first exon of the ZmWUS1 coding sequence was first introduced into wild-type maize, and then the resulting line was crossed to a Bif3 mutant (Fig. 3b). One heterozygous Bif3 plant resulting from this cross showed a normal inflorescence phenotype (Fig. 3c). By gene-specific amplification and direct sequencing we determined that ZmWUS1-B carried a 42 bp deletion/11 bp insertion (CR1) in this plant (Fig. 3c). ZmWUS1-A was also edited in this plant, as expected given that the gRNA could not distinguish between the two identical copies of ZmWUS1, and carried a 1 bp deletion in the targeted region. Additional editing events (CR2, CR3) were subsequently obtained and produced +/Bif3 plants with a wild-type phenotype and edited ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B copies (Supplementary Fig. 5). Altogether, the two intragenic suppressor approaches demonstrated that the Bif3 phenotype is caused by the presence of an additional functional copy of the ZmWUS1 gene.

Ectopic expression of ZmWUS1-B is responsible for the Bif3 phenotype

It remained to be determined whether the overexpression of ZmWUS1 was caused by the presence of an extra copy of the ZmWUS1 gene, or by the unique ZmWUS1-B copy, as suggested by the normal phenotype of the Bif3-Rev2 individual. To confirm this, we introduced a 10 kb DNA fragment containing the entire ZmWUS1-A locus of Bif3 mutants into wild-type maize, and found that the plants were significantly shorter than non-transgenic siblings with wider and shorter leaves. However, both tassel and ear developed normally (Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating that adding an extra copy of ZmWUS1 was not sufficient to phenocopy the inflorescence phenotype of Bif3 mutants.

Since both Bif3-Rev1 and Bif3-Rev2 had normal inflorescences despite harboring both ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B copies, we used these revertants to compare the expression levels of ZmWUS1 by qRT-PCR. While homozygous Bif3-Rev1 retained elevated expression of ZmWUS1 (~11-fold), homozygous Bif3-Rev2 showed only a moderate (~2-fold) up-regulation compared to wild-type siblings (Fig. 3e). Next, we asked whether the ZmWUS1-B gene was responsible for the high levels of ZmWUS1 expression observed in Bif3 and Bif3-Rev1. We took advantage of the G > A SNP in the start codon of ZmWUS1-B to design allele-specific primers to quantify the relative contribution of ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B transcripts in Bif3-Rev1. By qRT-PCR we showed that ZmWUS1-B transcripts outnumbered those of ZmWUS1-A by approximately 12-fold (Fig. 3f). These results, together with the transgenic approach presented above, suggested that the Bif3 phenotype was caused by the duplicated ZmWUS1-B locus, whose novel chimeric promoter enhanced transcription.

We next analyzed the regulatory sequences upstream of ZmWUS1-B, focusing on the unique 119 bp region present in Bif3 mutants but lost in the Bif3-Rev2 revertant. We noticed that a 17 bp element, originally present in the ZmWUS1 promoter in single copy, was repeated three times in this region (Fig. 3g). Within each repeat, we identified an AGATAT motif which is an in vivo binding element of type-B ARR TFs (ARR1, ARR10, ARR12) that activates WUS expression in a cytokinin-dependent fashion15,17,19,20. This motif of the WUS promoter is highly conserved across multiple grass species (Supplementary Fig. 7). We therefore asked if the multimerization of this 6 bp motif caused the up-regulation of ZmWUS1-B expression. To this end, we tested whether maize ZmRR8 and ZmRR11, two broadly expressed genes (Supplementary Fig. 7) closely related to Arabidopsis ARR1, ARR10, ARR12, encoded type-B RRs capable of binding to the ZmWUS1 promoter region containing the AGATAT motif and activated its transcription. In electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), ZmRR8 binding was specific and was abolished when the AGATAT motifs were changed to TTTTTT (Fig. 3h). Subsequently, we used a transactivation dual-luciferase transient assay in maize protoplasts and determined that a 570 bp fragment of the ZmWUS1-B promoter containing multimerized copies of the 17 bp sequence (p570) had stronger transcriptional activity upon treatment with 10 µM cytokinin (6-Benzylaminopurine, 2.3×, p < 0.01) as well as in the presence of overexpressed ZmRR8 and ZmRR11 (2.1× and 3.5×, respectively, p < 0.05), than the proximal 444 bp promoter containing a single AGATAT motif (p444). Importantly, the latter was not observed when the AGATAT motifs were mutated (p570m, Fig. 3i, j). Overall, these results suggest that multiple copies of the AGATAT motif present in the unique 119 bp region of the ZmWUS1-B promoter cause its overexpression, and are bound by ZmRRs, making ZmWUS1-B hyper-responsive to cytokinin.

Ectopic expression of ZmWUS1 causes major architectural rearrangements of inflorescence meristems and mis-regulation of key stem cell regulators

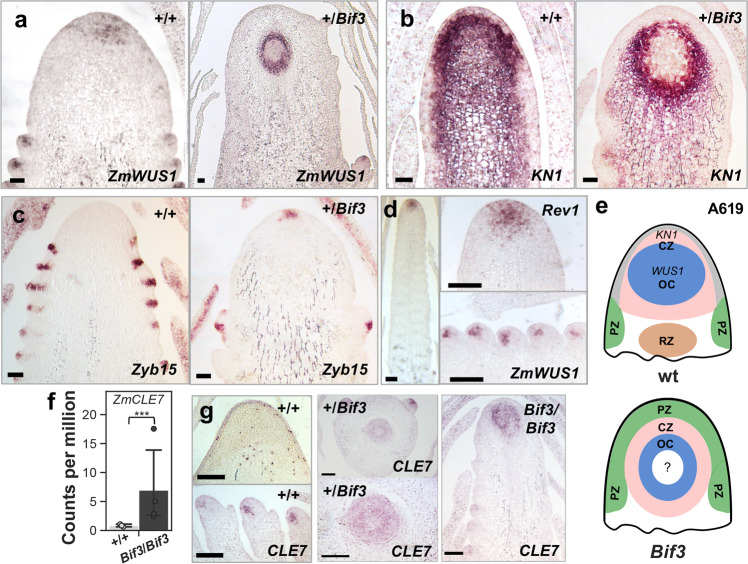

To determine how AM initiation in Bif3 inflorescences was disrupted and whether the novel chimeric promoter changed the pattern of expression of ZmWUS1, we used RNA in situ hybridizations in immature ears using different marker genes including ZmWUS1. In wild-type ears, very weak ZmWUS1 expression was observed in IMs, while a stronger signal was detected in AMs as previously reported8 (Fig. 4a). Surprisingly, however, a strong expression of ZmWUS1 was observed in Bif3 in a ring-like pattern located deeply in the inflorescence (Fig. 4a). Consecutive sections of this unusual domain showed that it roughly corresponded to a hollow sphere (Supplementary Fig. 8). This pattern was also detected with KNOTTED1 (KN1; Fig. 4b), a meristem marker gene normally expressed throughout the meristem and ground tissue, but excluded from the incipient primordia and the L1 layer31. Notably, ZYB15, a marker of suppressed bract primordia initiated at the PZ of IMs, was expressed at the tip of the Bif3 inflorescence structure (Fig. 4c). A stronger expression of ZmWUS1 was also observed in homozygous Bif3-Rev1 immature ears (Fig. 4d), but not in a ring-like domain. Collectively, these data indicated that the ectopic expression of a functional ZmWUS1-B copy caused a major rearrangement in IMs giving rise to a meristem with PZ, CZ, OC, and possibly RZ organized in concentric domains (Fig. 4e). This reorganization of the IM could explain the unusual formation of AMs in the tip of the inflorescences, observed by SEMs, and the ball-shaped ears, due to lack of longitudinal growth by the enclosed RZ.

Fig. 4. Bif3 architectural rearrangements in inflorescence meristems.

a–d RNA in situ hybridizations of ZmWUS1 (a, d), KN1 (b) and ZYB15 (c) in Bif3 ear inflorescence meristems (IMs). e Model of Bif3 IM structure. OC, organizing center; CZ, central zone; PZ, peripheral zone; RZ, rib zone. f Up-regulation of ZmCLE7 in Bif3 mutant RNA-seq data. Two-tailed Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001; plotted data represent mean ± standard deviation; n+/+ = 3, nBif3/Bif3 = 4 (n pools of three ear samples). g Ectopic expression of ZmCLE7 is observed by in situ hybridizations on longitudinal (+/+ and Bif3/Bif3) and cross (+/Bif3) sections of ear IMs. Scale bars: 50 μm in (a–c); 100 μm in (d, g).

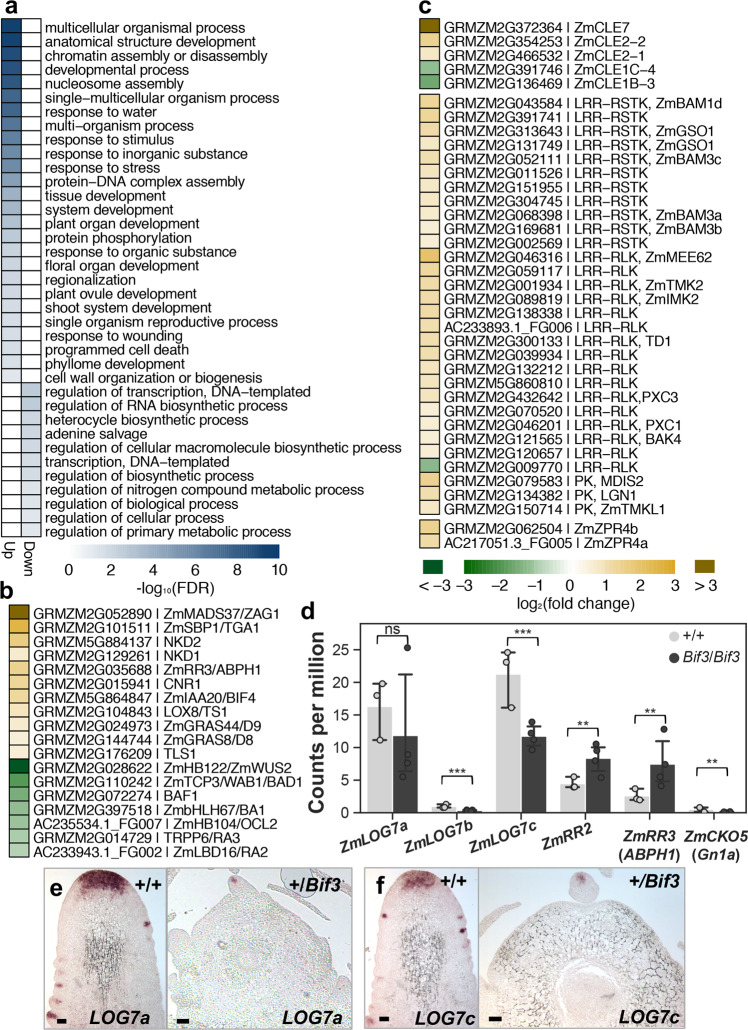

To better understand the consequences of the Bif3 IM rearrangement, we analyzed the transcriptional changes caused by the Bif3 mutation in ear primordia, focusing on genes involved in meristem size regulation and hormonal pathways, in particular auxin and cytokinin, critical for meristem function2. Differential gene expression analysis from RNA-seq experiments identified 1380 up-regulated and 242 down-regulated genes (p < 0.05, FDR < 0.1, fold-change > 1.5; Supplementary Data 1). Since WUS is a bifunctional transcriptional factor32, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of genes up- and down-regulated in Bif3 mutant ears (Fig. 5a). We found strong enrichment for “transcriptional regulation” in up-regulation and down-regulation gene sets, respectively (Fig. 5a). Up-regulated genes included those involved in inflorescence and flower development such as TGA1 and ZAG133,34 (Supplementary Data 1). Significantly down-regulated genes included those involved in AM initiation and maintenance including BAF1, BA1, RA2, RA3, and WAB135–39 (Fig. 5b), correlating with failure to initiate AMs in regularly arranged patterns.

Fig. 5. Altered expression of key meristem genes in Bif3 ear primordia.

a GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. b Differential expression of known developmental regulators. c Differential expression of CLAVATA3/ESR-related (CLE), protein kinase (PK), leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-receptor-like protein (LRR-RLP), LRR-receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK), LRR-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase-encoding genes (LRR-RSTK), and LITTLE ZIPPER4 (fold change ≥ 1.5). d Gene expression profiles. Two-tailed Student’s t-test **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, non-significant; plotted data represent mean ± standard deviation; n+/+ = 3, nBif3/Bif3 = 4 (n pools of three ear samples). e, f RNA in situ hybridizations of ZmLOG7a and ZmLOG7c in Bif3 inflorescence meristems. Bars: 200 µm.

We then asked how the Bif3 mutation affected the CLV-WUS feedback-loop pathway. WUS is sufficient to induce the expression of CLV314, and RNA-seq data showed that ZmCLE7, the likely maize CLV3 orthologue (GRMZM2G372364)23,40 was strongly up-regulated (~8.2-fold) in Bif3 ear primordia, compared to wild-type siblings (Fig. 4f). In situ hybridization showed that ZmCLE7, normally expressed in the meristem L1 layer in IMs and in the CZ of AMs, was ectopically expressed in Bif3 immature inflorescences in a similar fashion as ZmWUS1 (Fig. 4f, g). Additional up-regulated genes involved in maize meristem maintenance and the CLV-WUS pathway included two additional CLE genes, ZmCLE2-1 and ZmCLE2-2 (~1.8 to 2.8-fold), LIGULELESS NARROW1 (LGN1)41, THICK TASSEL DWARF1 (TD1)25, and two additional genes encoding protein kinases (PKs), and the paralogous ZmBAM1d and ZmBAM3a to 3c, the maize orthologs of the Arabidopsis BARELY ANY MERISTEM (BAM) genes42,43. Furthermore, 14 LRR-receptor-like kinase-encoding genes (LRR-RLK), seven LRR-receptor-like serine/threonine-protein kinase (LRR-RSTK)-encoding genes, and two LITTLE ZIPPER4 co-orthologs (ZmZPR4a and ZmZPR4b)44 (Fig. 5c) were also up-regulated. Notably, among CLE genes, ZmCLE1c-4 and ZmCLE1b-3 were instead down-regulated (2.2-fold and 3.1-fold, respectively) in Bif3 ear primordia (Fig. 5c).

Since cytokinin is an essential hormone for meristem maintenance, we examined the expression of the LONELY GUY (LOG)45 maize co-orthologs. LOG encodes a cytokinin-activating enzyme in the final biosynthetic step to produce free-base cytokinin to maintain meristem activity. LOG is expressed in the CZ of IMs45 in rice, and two of the three maize LOG co-orthologs46 were expressed in the CZ of IMs and AMs of wild-type ears. These two genes were down-regulated in Bif3 ear primordia (Fig. 5d), and were expressed only in the AMs of Bif3 ears and not in IMs (Fig. 5e, f). Additionally, we determined that two type-A ZmRR genes, ZmRR2 and ZmRR3/ABPH1, which act as negative feedback regulators of cytokinin function, were significantly up-regulated47. All these data suggested that cytokinin biosynthesis and response are severely impaired in Bif3 IMs.

Together with cytokinin, auxin is a key hormone controlling basic meristem function2. We therefore checked the interaction of BIF3 with BIF4, which encodes an Aux/IAA protein48 that was significantly up-regulated in Bif3 ear primordia (Supplementary Fig. 9). We tested the genetic interaction of Bif3 and Bif4, a semi-dominant inflorescence mutant that alters branch and spikelet formation, in the B73 background, which mitigates the severity of the heterozygous Bif3 phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 1). SEMs of tassel and ear primordia revealed that heterozygous Bif3 inflorescences in B73 had normal IMs while only ears had patterning defects. However, both tassels and ears had enlarged IMs and were severely affected in inflorescence patterning in homozygous Bif3 mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9). Surprisingly, in situ hybridizations with ZmWUS1 and KN1 in Bif3/Bif3 ears often revealed two OCs (Supplementary Fig. 9), suggesting that immature mutant ears tried to recover and form a normal IM. Double heterozygous +/Bif3;+/Bif4 mutants dramatically enhanced the phenotype of single +/Bif3 or +/Bif4 phenotypes, with ears showing extensive barren patches (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 9). SEM analysis of +/Bif3;+/Bif4 immature ears showed disorganized IMs with few irregularly arranged AMs, when compared to both single mutants (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 9). By in situ hybridization we determined that ZmWUS1 expression was still up-regulated in the IM of +/Bif3;+/Bif4 double mutants (Supplementary Fig. 9). Furthermore, the expression of KN1 was excluded from an additional cell layer of +/Bif3 and +/Bif3;+/Bif4 IMs when compared to wild-type and +/Bif4 inflorescences (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 9), and ZmLOG7a in the CZ of +/Bif3;+/Bif4 IMs was missing (Supplementary Fig. 9). Altogether, elevated ZmWUS1 expression caused disruption of auxin and cytokinin pathways, leading to major architectural rearrangements of IM and defects in initiation and maintenance of AM in Bif3 ears.

Fasciated ear mutants enhance Bif3 inflorescence defects

WUS expression is controlled by the CLV-WUS negative feedback-loop which in maize includes the CLV2 ortholog FEA2, the LRR-receptor-like protein FEA3, and the Gα subunit of heterotrimeric GTP binding protein CT221,23,24, among others. However, the function of WUS in maize remains unresolved. We therefore investigated the genetic interactions between Bif3 and fasciated mutants using the less severe Bif3 mutant in the B73 background for double mutant analysis.

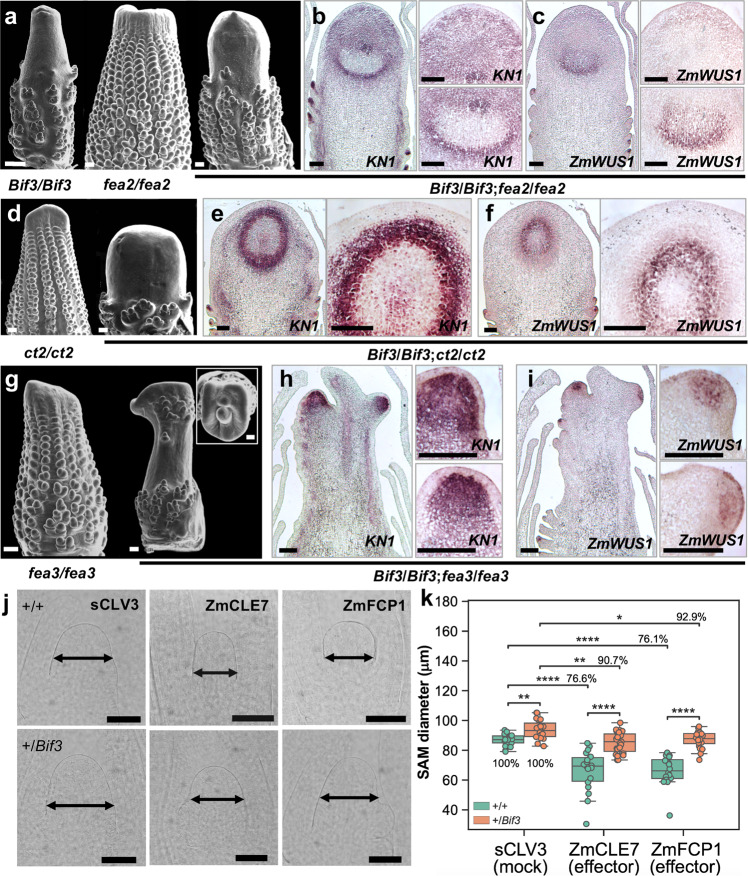

Bif3 dramatically enhanced the phenotype of single fea2, fea3, and ct2 mutants, showing in ears more enlarged and fasciated IMs, stronger than those observed in single Bif3 IMs (Fig. 6a, d, g and Supplementary Fig. 10). The enhancement was also evident in mature tassels, in particular in double mutant combinations with ct2 and fea3 that showed extremely reduced and barren central spikes (Supplementary Fig. 10). These results indicated that removing negative regulation of ZmWUS1 expression enhanced the Bif3 phenotype, consistent with a model in which FEA2, FEA3 and CT2 negatively regulate ZmWUS1 expression to maintain IMs. We also examined the expression patterns of KN1 and ZmWUS1 in double mutant IMs. Double fea2/fea2;Bif3/Bif3 and ct2/ct2;Bif3/Bif3 mutants retained the ring-shaped expression of ZmWUS1 and KN1 in extremely enlarged IMs. Intriguingly, this expression pattern was not detected in the fea3/fea3;Bif3/Bif3, and the IM split in multiple apical meristems (Fig. 6g, h).

Fig. 6. Genetic and molecular interaction of Bif3 and negative regulators of ZmWUS1.

a, d, g SEMs of single and double mutant ears in B73 background. Scale bars: 200 μm. b, c, e, f, h, i In situ hybridizations in double mutant immature ears with ZmWUS1 and KN1 antisense probes. Scale bars: 50 μm. j, k Bif3 SAMs are partially resistant to ZmCLE7 and ZmFCP1 peptide treatments. Percentages in (k) indicate reduction relative to scrambled peptide control (sCLV3). Two-tailed Student’s t-test *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 (n+/+ sCLV3 = 17; n+/Bif3 sCLV3 = 19; n+/+ ZmCLE7 = 18; n+/Bif3 ZmCLE7 = 23; n+/+ ZmFCP1 = 16; n+/Bif3 ZmFCP1 = 20). Box plot center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, maximum and minimum values. Single datapoints outside of the whiskers represent outliers Scale bars: 100 μm.

FEA2 and CT2 are receptor components that participate in CLE7 signaling, while FEA3 perceives the ZmFCP1 peptide in a parallel signaling pathway to the CLV-WUS pathway6,23. FEA3 functions to restrict ZmWUS1 expression and exclude it from the RZ23,46. We therefore tested the sensitivity of Bif3 embryonic SAMs to both ZmCLE7 and ZmFCP1 in comparison to wild-type embryos. As expected due to ZmWUS1 overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 10), +/Bif3 SAMs showed partial resistance to both peptides as they were less sensitive to the treatments than wild-type embryos (Fig. 6j, k). Altogether, these findings suggest that in maize, unlike rice, the function of WUS in the CLV-WUS feedback pathway is conserved.

Discussion

Recent tandem duplications are the most challenging structural variations to identify in genomes and have been significant drivers of phenotypic variability in traits important for domestication and breeding of crop species49–51. Here we determined that the ZmWUS1 locus underwent a large tandem segmental duplication event in Bif3 mutants that created a unique 119 bp insertion in the proximal promoter region of the duplicate ZmWUS1-B copy. Segmental duplications are a typical feature of many plant and animal genomes52,53, and are known to generate new genes, diversify gene functions, and expand gene families in the course of genome evolution54. The new copies of the duplicated genes can acquire modified functions compared to the ancestral ones, as in the case of the maize dominant pod corn mutant Tunicate1, which is caused by a long-range chromosomal inversion followed by a tandem duplication of the MADS box transcription factor Zmm19 in the junction region55. However, long chromosome segment repeats are often unstable and lead to repeat losses, as observed for example in other dominant maize mutants56,57. In Bif3 mutants, instability of the tandem-duplicated structure was obvious during the mutagenesis screen and since MuDR has been reported to be active under these conditions58, it may have been triggered by the pollen EMS treatment.

While the CLV-WUS pathway has been known for decades, an open and long-standing question is whether the function of individual members of the pathway is conserved across plant species. Notably, the rice WOX4 gene provides an analogous function to WUS in meristems, while the true WUS ortholog TAB1 has only a role in AM initiation9,11. Our data in maize indicate that the ZmWUS1 is involved in both meristem maintenance and AM initiation. However, we cannot rule out that the defects in AM initiation observed in Bif3 mutant inflorescences may be a consequence of the drastic reorganization of IMs, whereby the CZ, OC and possibly the RZ are deeply embedded in differentiated tissue. Hence the signal that normally triggers the formation of lateral primordia has to travel through several more cell layers to reach the surface of the inflorescence structure and this could be the cause of the observed patterning defects. Nonetheless, our genetic and molecular analysis of the interaction of ZmWUS1 and the various components of the CLV-WUS pathway are consistent with conservation of the pathway in maize, namely that ZmWUS1 functions in meristem size regulation, suggesting that rice may not be representative of all monocots. In support of its role in meristem size regulation, our data show that ZmWUS1 is expressed at a very low level in IMs and agree with data from a published transcriptional reporter line23. Our transgenic analysis also showed that increasing ZmWUS1 expression by altering copy number (Supplementary Fig. 6) has consequences to vegetative development, suggesting that tight transcriptional control of ZmWUS1 is essential for SAM function. Finally, we conclude that CRISPR-induced mutations in ZmWUS1 do not appear to have phenotypic consequences for overall maize development (Supplementary Fig. 9), likely due to the presence of the paralogous ZmWUS2 gene8, suggesting that the two genes play redundant functions in meristem development. Alternatively, other WOX genes could work redundantly with ZmWUS1. Recently, an enlarged ball-shaped SAM was observed in Arabidopsis plants expressing a constitutively active version of a type-B ARR20 which mimics constant cytokinin response. This is consistent with our findings and indicates that a similar rearrangement of the meristem structure occurred in these Arabidopsis plants and raises intriguing questions on why hypersensitivity to cytokinin by WUS genes drives the formation of spherical meristems.

Tinkering with meristem size holds promise for increasing yield in different plant species26,59,60. The dominant Bif3 mutation places ZmWUS1 squarely at the center of meristem size regulation in maize and provides new insights into the transcriptional control of WUS genes. Significant interest has been placed on the function of ZmWUS genes given their use alone or in combination with the transcription factor BBM for improving transformation of maize and other recalcitrant species12,13. Our results indicate that high levels of expression of ZmWUS1 can be achieved by multimerization of a single highly conserved cis-regulatory element of the proximal promoter sequence. These findings could be applied to different species to boost the expression of morphogenetic factors in transformation systems.

Methods

Plant materials and genotyping

The original Bif3 allele (Bif3-ref) was a donation by Matt Evans and Paula McSteen. All mutants used for phenotypic and molecular analysis were backcrossed to the A619 (BC10) and B73 (BC8) inbred lines. For double mutant analysis in the B73 background, we used the fea2-0, fea3-0, ct2-ref, and Bif4-N2616 alleles from previous reports6,23,24,48. Double mutant genotype was determined using allele-specific primers (Supplementary Data 2).

Plant phenotyping

Images of IMs were captured by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) while those of SAMs were captured on FAA-fixed and methyl salicylate-cleared seedling tissues by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. For SEMs, fresh tassel and ear primordia (3–5 mm) were dissected and directly analyzed using a JMC-6000PLUS benchtop SEM. For quantifying meristem width, 7-day-old siblings containing SAMs were dissected and fixed in FAA (2% formaldehyde, 5% acetic acid, 60% ethanol) overnight at 4 °C. The fixed tissues were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (75%, 85%, 95%, and 100%) for 30 min each at room temperature and cleared in methyl salicylate/ethanol series (50% and 100%) for 1 h each at room temperature, followed by 100% methyl salicylate overnight treatment. Meristems were mounted in methyl salicylate on slides with coverslips and imaged using a LEICA DM5500B microscope. Measurements were taken using Fiji (ImageJ); the width of the meristem was calculated using P1 as a reference.

Leaf width (approximately 15 cm above ligule) and length (leaf tip to ligule) of +/Bif3 mutants and pZmWUS1-A::ZmWUS1-A transgenic lines were measured on the top-third leaf blades.

EMS mutagenesis and screen

For EMS mutagenesis screen, pollen of A619 Bif3/Bif3 mutants was collected in the morning, treated with EMS (0.06% in mineral oil) for 45 min and used to fertilize A619 +/+ ears. Seeds of the resulting M1 progeny were planted in the field in two consecutive years and revertants were identified based on tassel and ear phenotypes. For the 3D-pooling strategy, we first pooled equal amounts of leaf tissues, extracted genomic DNA, and amplified the coding sequence of ZmWUS1 (both ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B copies) by PCR using primers WUSseqF3 and WUSseqR3. Subsequently, the PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and sonicated to 200 bp fragments in a Covaris S2 sonicator. DNA fragments were subsequently purified using AmpureXP beads at a 2:1 bead:DNA ratio. The fragmented DNA was then end-repaired using the End-It kit (Lucigen) followed by DNA purification using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). The purified samples were then A-tailed using Klenow Fragment for 30 min at room temperature and again purified using QIAquick PCR Purification (QIAGEN). The A-tailed DNA fragments were then ligated overnight with a truncated Illumina Y-adapter61. Finally, these DNA libraries with unique barcodes were purified by bead cleaning using a 1:1 bead:DNA ratio, and then eluted from the beads in 30 μL of elution buffer, followed by double-stranded DNA quantification using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit. DNA libraries were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 sequencer. Reads were mapped to ZmWUS1 of Bif3 allele using software UGENE62, and the alignment results and the nucleotide changes were detected using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)63.

Positional cloning of Bif3

The Bif3 locus was initially mapped to chromosome 2 between bins 2.00 and 2.01 by bulk segregant analysis (BSA) using a +/Bif3 × Mo17 BC1 population64. Fine mapping of the Bif3 locus was obtained using molecular markers available from MaizeGDB65 on approximately 590 mutant individuals from a +/Bif3 × Mo17 BC2 population. Molecular markers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

The tandem duplication in the Bif3 locus was determined by Southern blotting and thermal asymmetric interlaced polymerase chain reaction (TAIL-PCR). For Southern blotting, genomic DNA from Bif3 homozygous mutant and wild-type siblings was extracted from leaves. 10μg of genomic DNA was digested with restriction enzymes (EcoRI, XbaI, HindIII, and PstI) at 37 °C for 6 h. The fragmented DNA was resolved by size on a 0.7% agarose gel, denatured, and blotted onto a Hybond-N membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was cross-linked by UV light and hybridized with ZmWUS1-specific DNA probe. This ~1 kb ZmWUS1-specific DNA probe spanned from the proximal promoter to the second intron (from −335 bp to +708 bp) and was amplified using primers WUSseqF3 and WUSfu-R1, and then cloned into pGEM T-easy vector. The DNA probe was isotope-labeled with Random Primer DNA Labeling Kit Ver.2 (TaKaRa) and purified with ProbeQuant G-50 Micro Column (GE Healthcare). For Bif3 TAIL-PCR chromosome walking, symmetric and asymmetric PCRs were performed as described previously27; the amplicons that ranged from 2 to 6 kb were recovered from gel and cloned into pCR-Blunt vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for sequencing. Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Multiple sequence alignments were performed using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/).

Generation of maize transgenic lines

Transgenic maize plants carrying the pZmWUS1-A::ZmWUS1-A construct and CRISPR-Cas9-derived mutants and their wild-type segregants were grown under standard long-day greenhouse conditions (16 h light and 8 h dark) or in the field. To obtain the CRISPR-Cas9-derived mutants, a ZmWUS1-specific guide RNA was cloned into pBUE411 vector by Golden Gate cloning, and the resulting construct was introduced into Hi-II immature embryos by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, followed by callus induction, bialaphos selection, and shoot and root regeneration66. CRISPR-Cas9-derived ZmWUS1-B knock-out mutation in Bif3 mutant was created by crossing transgenic lines carrying CRISPR-Cas9-ZmWUS1gRNA construct with Bif3 mutants. The genotype of the knock-out mutations was determined by copy-specific genotyping primers—1428WUS-FWD/WUSseqR1 (for ZmWUS1-A) 6968-F7/WUSseqR1 (for ZmWUS1-B)—followed by direct sequencing using primer Bif3RTF3-1.

The pZmWUS1-A::ZmWUS1-A transgenic construct was created by cloning a 10 kb genomic fragment including the 7.7 kb upstream of ATG, the 1.2 kb gene body (ATG to TGA) and the 1.1 kb downstream fragment of TGA of the Bif3 mutant into the pTF101.1 transformation vector. The resulting construct was introduced into Hi-II maize by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation method at the Iowa State University Plant Transformation Facility. Out of 15 original events, only two events survived and made it to flowering. These two events were crossed with A619 and then backcrossed twice for phenotypic analysis. Genotyping of the transgenic construct was done using primers 7448-F12 and 7448-R9. Additionally, the presence of the transgenic construct was monitored by treatment of leaf blades of 3-week-old plants with 0.4% Liberty®. Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Expression and RNA-seq analysis

In situ hybridization experiments were performed on 2–4 mm ear and tassel primordia fixed in PFA, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, cleared with Histoclear and embedded in Paraplast48. To generate the antisense RNA probes for ZmWUS1, ZmLOG7a, ZmLOG7c, ZmOCL4, ZmIAA9, ZYB15, KN1, and ZmCLE7 genes, the entire/partial coding sequences together with partial 3′-untranslated region of each gene were cloned into pENTR223-Sfi, pBJ36, or pGEM T-easy vectors (Promega). The resulting plasmids were linearized by restriction endonucleases, and the antisense RNA probes (with sizes ranging from 400 to 1000 bp) were synthesized by T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega). The vectors, enzymes, and primers used for probe design are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

qRT-PCR analysis was performed using an Illumina Eco Real-Time PCR System. At least three ear primordia were pooled for each genotype and two biological replicates were performed for each assay. Total mRNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase I (Qiagen) treatment and used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis with a qScript cDNA synthesis kit (Quanta Biosciences). qPCR was performed using gene-specific primers and the PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix (Quanta Biosciences). Target cycle threshold values were normalized using ZmUBIQUITIN. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

For RNA-sequencing analysis, ear primordia (3–4 mm) of homozygous Bif3 mutant and wild-type siblings in B73 background were dissected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase I (Qiagen) treatment. Four biological replicates for homozygous Bif3 (three ear primordia for each replicate) and three biological replicates for wild-type (three ear primordia for each replicate) were performed for RNA-sequencing analysis. RNA-seq raw data were trimmed with Trimmomatic with default settings67 and aligned to the reference genome (B73v3 genome) using HISAT 2.1.0 with default settings68. Gene expression was quantified as read counts by HTSeq-count69 and genes with differential expressions were determined by edgeR 3.18.1 package70. All statistical analyses of gene expression were conducted in R and python. Genes with a fold change > 1.5 with p < 0.05 and FDR < 0.1 were considered as differentially expressed genes.

EMSA and transactivation assays

For EMSAs, the 119 bp repeat of ZmWUS1-B novel promoter that contained the putative B-ARR core AGATAT element was amplified from Bif3 mutant, and biotinylated using the Biotin 3′ End DNA Labeling Kit (ThermoScientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The recombinant protein GST-ZmRR8 (DNA-binding domain only, 191aa-262aa) was generated by cloning DNA-binding domain sequences of ZmRR8 into the pET-60-DEST vector, followed by IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside)-induced expression in Rosetta (DE3) cells (Stratagene). Cells from 500 mL Terrific Broth (TB) medium were harvested and resuspended in 10 mL resuspension buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), and 2 mM lysozyme and then sonicated on ice. Cleared lysate was applied to GST Gravitrap Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) columns and washed with resuspension buffer thoroughly. Recombinant proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione and concentrated using Amicon Ultra 30 K concentrators (Millipore). DNA binding assays were performed using the Lightshift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (ThermoScientific) as follows: binding reactions containing 1× Binding Buffer, 50 ng/μL poly(dI/dC), 2.5% glycerol, 2 μL biotinylated probe, and 1 μL purified GST-ZmRR8 protein were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and loaded on a 6% DNA retardation gel (Life Technologies), followed by transferring the DNA probes and proteins to a nylon membrane. Subsequent detection was carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The mutated probe was generated by oligonucleotide synthesis, and the three core AGATAT elements were changed to three TTTTTT elements.

Transactivation assays were conducted in maize mesophyll protoplasts as described previously71. The effector vector pEarlyGate 100 was used for expression of ZmRR8, ZmRR11 and YFP driven by the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) dual 35S promoter. The reporter vector pGreenII 0800-LUC was used for detecting the transactivation activities of ZmRR8 and ZmRR11 on the ZmWUS1-B novel promoter with 119 bp insertion (p570) and ZmWUS1-B original promoter without 119 bp insertion (p444), respectively. Mutated elements in which the three core AGATAT elements of the 119 bp region were changed to TTTTTT by oligonucleotide synthesis (Sigma). Equal amounts of effector plasmids and reporter plasmids were co-transformed into mesophyll protoplasts of maize by PEG-mediated protoplast transformation72. The protoplasts were incubated in dark at 23 °C for 15 h for Firefly luciferase/Renilla luciferase (LUC/REN) activity analysis. The ratio of LUC/REN activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega). Primers used to amplify the ZmWUS1-B promoter and the coding sequences of ZmRR8 and ZmRR11 are listed in Supplementary Data 2.

Peptide assays

Maize embryos segregating for Bif3 and wild-type were dissected 10 days after pollination and cultured on gel medium supplied with scrambled peptide, ZmFCP1 or ZmCLE7 peptide (30 μM each; Genscript) as described previously6. After 10 days, embryos were collected for genotyping, fixed and cleared with methyl salicylate as described above. SAMs were then imaged using a LEICA DM5500B microscopy and the SAM width was measured using ImageJ as described above.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-tests; exact p values for all comparisons are provided in the Source Data file. All experiments have been replicated at least twice with similar or identical results and/or data have been extracted using multiple biological samples (e.g., RNA-seq, EMS mutagenesis). For in situ hybridizations, at least two independent samples were hybridized with similar results; a representative picture is shown in the figures. Similarly, representative SEMs of the different genotypes analyzed are presented in the figures.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Matt Evans and Paula McSteen for donating the original Bif3 allele; to Dave Jackson and members of the Gallavotti lab for critical reading of the manuscript; to Weibin Song for suggestions on maize transformation; to Caitlin Menello for assistance with revertant characterization and Qiguo Yu for assistance with Southern blots; to Robert Schmitz and the Georgia University Genetic Department for RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (IOS#1546873 and IOS#2026561) to A.G. and by the Charles and a Johanna Busch Postdoctoral Fellowship to Z.C.

Source data

Author contributions

Z.C., M.G., and A.G. designed research and analyzed data; Z.C., W.L., C.G., A.B., M.G., and A.G. performed experiments; Z.C. and A.G. wrote the paper.

Data availability

RNA-seq datasets are deposited in GEO with accession code GSE158330. Genomic sequences of ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B loci in the Bif3 mutant are available in GenBank (accession numbers MW677561, MW677562, MW677563). Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Sarah Hake, Jan Lohmann, and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22699-8.

References

- 1.Fletcher JC. The CLV-WUS stem cell signaling pathway: a roadmap to crop yield optimization. Plants (Basel) 2018;7:87. doi: 10.3390/plants7040087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitagawa M, Jackson D. Control of meristem size. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019;70:269–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer KF, et al. Role of WUSCHEL in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Cell. 1998;95:805–815. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, et al. Control of plant stem cell function by conserved interacting transcriptional regulators. Nature. 2015;517:377–380. doi: 10.1038/nature13853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou Y, et al. HAIRY MERISTEM with WUSCHEL confines CLAVATA3 expression to the outer apical meristem layers. Science. 2018;361:502–506. doi: 10.1126/science.aar8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Je BI, et al. The CLAVATA receptor FASCIATED EAR2 responds to distinct CLE peptides by signaling through two downstream effectors. eLife. 2018;7:e35673. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greb T, Lohmann JU. Plant stem cells. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:R816–R821. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nardmann J, Werr W. The shoot stem cell niche in angiosperms: expression patterns of WUS orthologues in rice and maize imply major modifications in the course of mono- and dicot evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2492–2504. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka W, et al. Axillary meristem formation in rice requires the WUSCHEL ortholog TILLERS ABSENT1. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1173–1184. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu Z, et al. MONOCULM 3, an ortholog of WUSCHEL in rice, is required for tiller bud formation. J. Genet. Genomics. 2015;42:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki C, Tanaka W, Hirano H-Y. Transcriptional corepressor ASP1 and CLV-like signaling regulate meristem maintenance in rice. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:1520–1534. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe K, et al. Morphogenic regulators baby boom and Wuschel improve monocot transformation. Plant Cell. 2016;28:1998–2015. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe K, et al. Rapid genotype “independent” Zea mays L. (maize) transformation via direct somatic embryogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant. 2018;54:240–252. doi: 10.1007/s11627-018-9905-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoof H, et al. The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems in maintained by a regulatory loop between the CLAVATA and WUSCHEL genes. Cell. 2000;100:635–644. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zubo YO, et al. Cytokinin induces genome-wide binding of the type-B response regulator ARR10 to regulate growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E5995–E6004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620749114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai X, et al. ARR12 promotes de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis thaliana via activation of WUSCHEL expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017;59:747–758. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng WJ, et al. Type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORs specify the shoot stem cell niche by dual regulation of WUSCHEL. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1357–1372. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wybouw B, De Rybel B. Cytokinin - a developing story. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, et al. Cytokinin signaling activates WUSCHEL expression during axillary meristem initiation. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1373–1387. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie M, et al. A B-ARR-mediated cytokinin transcriptional network directs hormone cross-regulation and shoot development. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1604. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03921-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taguchi-Shiobara F, Yuan Z, Hake S, Jackson D. The fasciated ear2 gene encodes a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like protein that regulates shoot meristem proliferation in maize. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.208501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pautler M, et al. FASCIATED EAR4 encodes a bZIP transcription factor that regulates shoot meristem size in maize. Plant Cell. 2015;27:104–120. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.132506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Je BI, et al. Signaling from maize organ primordia via FASCIATED EAR3 regulates stem cell proliferation and yield traits. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:785–791. doi: 10.1038/ng.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bommert P, Je BI, Goldshmidt A, Jackson D. The maize Galpha gene COMPACT PLANT2 functions in CLAVATA signalling to control shoot meristem size. Nature. 2013;502:555–558. doi: 10.1038/nature12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bommert P, et al. thick tassel dwarf1 encodes a putative maize ortholog of the Arabidopsis CLAVATA1 leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase. Development. 2005;132:1235–1245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bommert P, Nagasawa NS, Jackson D. Quantitative variation in maize kernel row number is controlled by the FASCIATED EAR2 locus. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:334–337. doi: 10.1038/ng.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S, He J, Cui Z, Li S. Self-formed adaptor PCR: a simple and efficient method for chromosome walking. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5048–5051. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02973-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lisch D, Chomet P, Freeling M. Genetic characterization of the Mutator system in maize: behavior and regulation of Mu transposons in a minimal line. Genetics. 1995;139:1777–1796. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuffer, M. G. Mutagenesis. In The Maize Handbook (eds. Freeling M. & Walbot V.) 212–219 (Springer, 1994).

- 30.Chaudhuri J, Jasin M. Immunology. Antibodies get a break. Science. 2007;315:335–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1138091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson D, Veit B, Hake S. Expression of maize Knotted1 related homeobox genes in the shoot apical meristem predicts patterns of morphogenesis in the vegetative shoot. Development. 1994;120:405–413. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda M, Mitsuda N, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis WUSCHEL is a bifunctional transcription factor that acts as a repressor in stem cell regulation and as an activator in floral patterning. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3493–3505. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H, et al. The origin of the naked grains of maize. Nature. 2005;436:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature03863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mena M, et al. Diversification of C-function activity in maize flower development. Science. 1996;274:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis MW, et al. Gene regulatory interactions at lateral organ boundaries in maize. Development. 2014;141:4590–4597. doi: 10.1242/dev.111955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallavotti A, et al. The role of barren stalk1 in the architecture of maize. Nature. 2004;432:630–635. doi: 10.1038/nature03148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gallavotti A, et al. BARREN STALK FASTIGIATE1 is an AT-hook protein required for the formation of maize ears. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1756–1771. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Satoh-Nagasawa N, et al. A trehalose metabolic enzyme controls inflorescence architecture in maize. Nature. 2006;441:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature04725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bortiri E, et al. ramosa2 encodes a LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARY domain protein that determines the fate of stem cells in branch meristems of maize. Plant Cell. 2006;18:574–585. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Leal D, et al. Evolution of buffering in a genetic circuit controlling plant stem cell proliferation. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:786–792. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moon J, Candela H, Hake S. The Liguleless narrow mutation affects proximal-distal signaling and leaf growth. Development. 2013;140:405–412. doi: 10.1242/dev.085787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nimchuk ZL, et al. Plant stem cell maintenance by transcriptional cross-regulation of related receptor kinases. Development. 2015;142:1043–1049. doi: 10.1242/dev.119677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi F, et al. A small peptide modulates stomatal control via abscisic acid in long-distance signalling. Nature. 2018;556:235–238. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Q, et al. Domain-specific expression of meristematic genes is defined by the LITTLE ZIPPER protein DTM in tomato. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:134. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurakawa T, et al. Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature. 2007;445:652–655. doi: 10.1038/nature05504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knauer S, et al. A high-resolution gene expression atlas links dedicated meristem genes to key architectural traits. Genome Res. 2019;29:1962–1973. doi: 10.1101/gr.250878.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giulini A, Wang J, Jackson D. Control of phyllotaxy by the cytokinin-inducible response regulator homologue ABPHYL1. Nature. 2004;430:1031–1034. doi: 10.1038/nature02778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galli M, et al. Auxin signaling modules regulate maize inflorescence architecture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:13372–13377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516473112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soyk S, et al. Duplication of a domestication locus neutralized a cryptic variant that caused a breeding barrier in tomato. Nat. Plants. 2019;5:471–479. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0422-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alonge M, et al. Major impacts of widespread structural variation on gene expression and crop improvement in tomato. Cell. 2020;182:145–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lye ZN, Purugganan MD. Copy number variation in domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gaut BS, Doebley JF. DNA sequence evidence for the segmental allotetraploid origin of maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6809–6814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bailey JA, et al. Recent segmental duplications in the human genome. Science. 2002;297:1003–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1072047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Samonte RV, Eichler EE. Segmental duplications and the evolution of the primate genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrg705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han JJ, Jackson D, Martienssen R. Pod corn is caused by rearrangement at the Tunicate1 locus. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2733–2744. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veit B, Vollbrecht E, Mathern J, Hake S. A tandem duplication causes the Kn1-O allele of Knotted, a dominant morphological mutant of maize. Genetics. 1990;125:623–631. doi: 10.1093/genetics/125.3.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du Y, et al. Gene duplication at the Fascicled ear1 locus controls the fate of inflorescence meristem cells in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2019218118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019218118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yandeau-Nelson MD, et al. MuDR transposase increases the frequency of meiotic crossovers in the vicinity of a Mu insertion in the maize a1 gene. Genetics. 2005;169:917–929. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.035089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodriguez-Leal D, et al. Engineering quantitative trait variation for crop improvement by genome editing. Cell. 2017;171:470–480.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu L, et al. Enhancing grain-yield-related traits by CRISPR-Cas9 promoter editing of maize CLE genes. Nat. Plants. 2021;7:287–294. doi: 10.1038/s41477-021-00858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galli M, et al. The DNA binding landscape of the maize AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR family. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4526. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06977-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okonechnikov K, Golosova O, Fursov M, team, U. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gallavotti A, Whipple CJ. Positional cloning in maize (Zea mays subsp. mays, Poaceae). Appl. Plant Sci. 2015;3:apps.1400092. doi: 10.3732/apps.1400092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Portwood JL, et al. MaizeGDB 2018: the maize multi-genome genetics and genomics database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D1146–D1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ishida Y, Hiei Y, Komari T. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of maize. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1614–1621. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Y, Lun AT, Smyth GK. From reads to genes to pathways: differential expression analysis of RNA-Seq experiments using Rsubread and the edgeR quasi-likelihood pipeline. F1000Res. 2016;5:1438. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8987.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheen J. Molecular mechanisms underlying the differential expression of maize pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase genes. Plant Cell. 1991;3:225–245. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Descriptions of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq datasets are deposited in GEO with accession code GSE158330. Genomic sequences of ZmWUS1-A and ZmWUS1-B loci in the Bif3 mutant are available in GenBank (accession numbers MW677561, MW677562, MW677563). Source data are provided with this paper.