Abstract

Background:

Upfront autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) remains an important therapy in managing multiple myeloma (MM), a disease of older adults.

Methods:

We investigated the outcomes of AHCT in MM in patients aged 70 years and older (≥70). The CIBMTR database registered 15,999 U.S. MM patients within 12 months of diagnosis during 2013–2017; 2,092 patients were ≥70. Non-relapse mortality (NRM), relapse/progression (REL), progression-free and overall survival (PFS, OS) were modeled using Cox proportional hazards with age at transplant as the main effect. Because of the large sample size, a p-value of <0.01 was considered significant a priori.

Results:

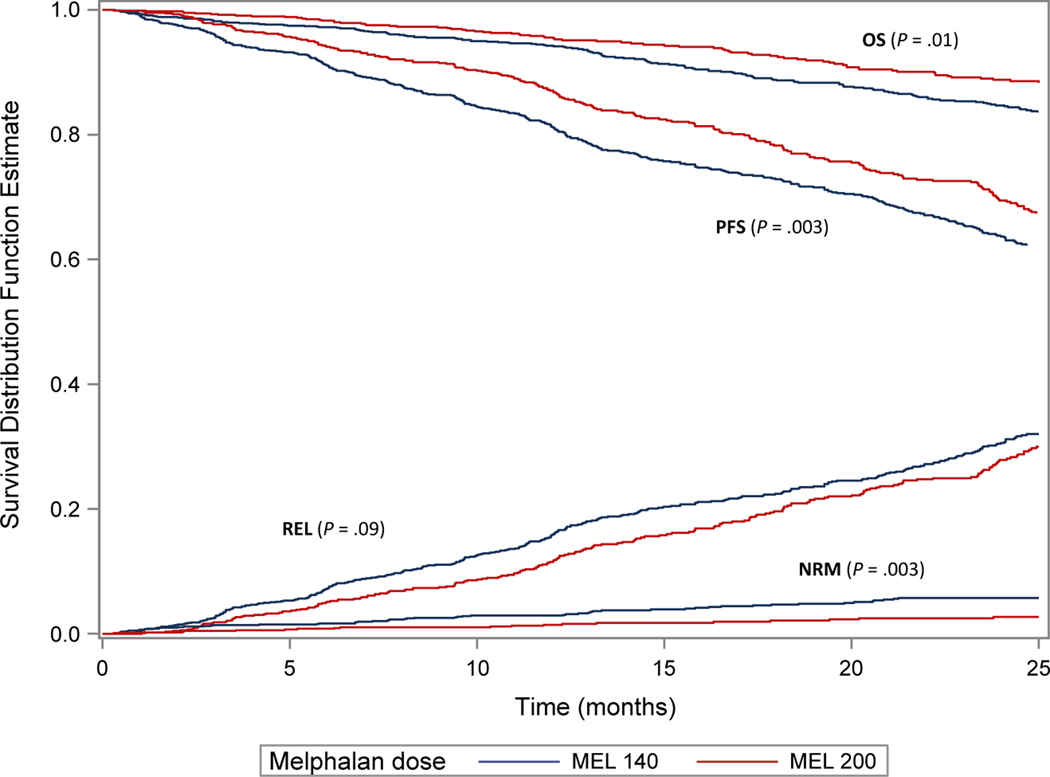

An increase in AHCT was noted in 2017 (28%) compared to 2013 (15%) in ≥70. While 82% patients received melphalan (Mel) 200 mg/m2 overall, 58% of the patients ≥70 received Mel 140 mg/m2. On multivariate analysis, patients ≥70 had no difference in NRM (hazard ratio (HR) 1.3, 99% confidence interval (CI) 1, 1.7, p 0.06), REL (HR 1.03, 99% CI 0.9–1.1, p 0.6), PFS (HR 1.06, 99% CI 1–1.2, p 0.2), and OS (HR 1.2, 99% CI 1–1.4, p 0.02) compared to the reference group (60–69 years). In patients ≥70, Mel 140 mg/m2 was associated with worse outcomes compared to Mel 200 mg/m2 including day-100 NRM 1 (1–2)% vs 0 (0–1)%, p 0.003, 2-year PFS 64 (60–67)% vs 69 (66–73)%, p 0.003, and 2-year OS 85 (82–87)% vs 89 (86–91)%, p 0.01, respectively, likely representing frailty.

Conclusion:

We conclude that AHCT remains an effective consolidation therapy across all MM age groups.

Keywords: transplant, geriatric oncology, myeloma

Precis:

Upfront autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) remains an important therapy in managing multiple myeloma (MM), a disease of older adults. This large database study confirms that AHCT remains an effective consolidation therapy in fit older adults aged 70 years and older.

Introduction

Multiple recent studies have confirmed the role of early autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) even in the age of current induction therapies.[1–5] Despite these data and continued recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network that transplant should be considered in patients with symptomatic disease, studies from the United States (US) suggest that AHCT utilization in MM, even in recent years, is less than 40%.[6] While race and ethnicity have been recognized as important barriers in AHCT utilization,[6] age is also an important barrier.[7 8]

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a cancer of older adults with the median age at diagnosis of 66–70 years in the United States (US).[9 10] Though the 5- and 10-year survival rates of patients diagnosed with MM have shown significant improvements in the last two decades, a group where long term outcomes have not been encouraging include older patients, both 65–74 and 75+ years old patients.[10] Prior single center, retrospective studies from the US have supported the safety and benefit of AHCT in MM patients 70 years and older[11 12] but these include patients treated in the pre-novel therapy era and may not reflect current clinical treatment paradigms.

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant (CIBMTR®) database shows that the number of transplants performed in patients over the age of 70 continues to increase annually.[13] We sought to study the outcomes of older patients with MM undergoing AHCT in 2013–2017 in the US. We hypothesized that MM patients aged 70 and older would have similar non-relapse mortality (NRM), relapse/progression (REL), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to MM patients less than 70 years at transplant.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

We used the CIBMTR database which captures and prospectively maintains outcomes of 75–80% of MM transplants in the US during 2013–2017.[14] The CIBMTR is a working group of more than 500 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on HCT to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW). Participating centers are required to report all transplantations consecutively and compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Data are collected at two levels: transplant essential data (TED) and comprehensive report form (CRF) data. TED forms include disease type, age, gender, pre-HCT disease stage and chemotherapy-responsiveness, date of diagnosis, graft type, conditioning regimen, post-transplant disease progression and survival, development of a new malignancy, and cause of death. All CIBMTR centers contribute to the TED set. More detailed disease and pre- and post-transplant clinical information is collected on a subset of registered patients selected for CRF data by a weighted randomization scheme. TED- and CRF-level data are collected pre-transplant, 100-days, and 6 months post-HCT and annually thereafter or until death. Data for the current analysis were retrieved from TED report forms as our intent was to capture all patients registered with the CIBMTR.

Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. The MCW Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Patients

Included in this analysis are consented adult (≥ 18 years) MM patients undergoing a single AHCT within 12 months from diagnosis between 2013 and 2017 in the US with peripheral blood hematopoietic cells after melphalan (Mel) conditioning. The TED dataset was used in this study and provided data on patient (age, gender, race, Karnofsky performance score [KPS], HCT comorbidity index [HCT-CI]), disease (immunoglobulin subtype, International staging system [ISS], cytogenetics) and transplant (time from diagnosis to transplant, disease status at transplant, melphalan conditioning dose and year of transplant) related covariates. Data regarding induction therapy received was available in 13% of the patients selected for this analysis who were registered in the CRF track. Of these patients, all were treated initially with proteasome inhibitors and/or immunomodulatory drugs thus extrapolating that patients on our study all received novel therapy.

Definitions and study endpoints

The primary objective of this study is to compare NRM in older versus younger MM patients following AHCT, where NRM was defined as death from any cause in the absence of relapse/progression. Our secondary objectives included PFS (defined as the time from transplantation to relapse, disease progression or death from any cause) and OS (defined as the time from transplantation to death from any cause). Our primary endpoint was to assess NRM among different age groups. Our secondary endpoint was to assess PFS, OS and relapse/progression among all age groups.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Cumulative incidences of NRM and disease relapse/progression were calculated accounting for competing risks. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to calculate the probabilities of PFS and OS. Multivariate analysis of PFS and OS were conducted using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to assess the main effect, age at transplant studied in decades, adjusting for key patient-, disease-, and transplant-related covariates (sex, race, KPS, HCT-comorbidity index, stage at diagnosis, disease status at transplant, cytogenetics, conditioning melphalan dose, time from diagnosis to transplant, and year of transplant). Age group 60–69 was used as the reference group based on maximum representation of patients. Owing to very few events in the <40-year group as well as a small overall N, this group was excluded from the multivariate analysis. Melphalan dose was studied at two levels; the standard 200mg/m2 and the reduced level 140mg/m2. The assumption of proportional hazards for each covariate in the Cox model was tested using time-dependent variables. A stepwise model selection approach was used to identify covariates associated with outcomes. Factors significant at the 1% level of significance (P <0.01) were kept in the final model. Hazard ratio (HR) with 99% confidence intervals (CI) were shown. A lower p-value was considered significant owing to the large sample size of the population and was decided a priori. A second subset analysis was conducted in patients 70 years and older (N=2,092) where the main effect was the melphalan conditioning dose. Other covariates that went into the model included sex, race, Karnofsky performance status, HCT-comorbidity index, stage at diagnosis, disease status at transplant, cytogenetics, conditioning melphalan dose, time from diagnosis to transplant, and year of transplant. Owing to the small sample size, p-values <0.05 were considered significant and hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 shows the overall patient population included in this study (N=15,999), including 2,092 patients aged 70 and older. The median patient age was 62 years (range, 20–83 years). Most patients were Caucasians (78%) with male (57%) predominance. Patients ≥70 years were more likely to be White compared to younger patients: 85% Caucasians for ≥70 years of age compared to 64% 20–39 years of age. All age groups had similar distribution of gender, KPS, HCT-CI, stage III by Durie-Salmon/International Staging System. There was a higher proportion of high-risk cytogenetics in patients ≥70 years (30%), compared to age group 40–49 years (24%) and 20–39 years (20%) in this population. Similar numbers of patients ≥70 years were in very good partial response (VGPR) or better prior to transplant compared to other age groups. While 82% of the overall population received Mel 200 mg/m2, only 41% of patients ≥70 received Mel 200 mg/m2. There was a higher proportion of transplants performed in the ≥70-year age group in 2017 (28%) compared to 2013 (15%). The median follow-up of survivors was 25 (<1–72) months.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total | 20–39 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60–69 | ≥70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 15999 | 308 | 1615 | 4952 | 7032 | 2092 |

| Median age (range) | 62 (20–83) | 37 (20–39) | 47 (40–49) | 56 (50–59) | 65 (60–69) | 72 (70–83) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 9160 (57) | 186 (60) | 908 (56) | 2841 (57) | 3960 (56) | 1265 (60) |

| Female | 6839 (43) | 122 (40) | 707 (44) | 2111 (43) | 3072 (44) | 827 (40) |

| Self-reported race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 12416 (78) | 198 (64) | 1088 (67) | 3702 (75) | 5658 (80) | 1770 (85) |

| African-American | 2683 (17) | 78 (25) | 396 (25) | 942 (19) | 1024 (15) | 243 (12) |

| Othera | 455 (3) | 18 (6) | 65 (4) | 158 (3) | 180 (3) | 34 (2) |

| Missing | 445 (3) | 14 (5) | 66 (4) | 150 (3) | 170 (2) | 45 (2) |

| Karnofsky score | ||||||

| ≥ 90 | 8562 (54) | 197 (64) | 966 (60) | 2838 (57) | 3648 (52) | 913 (44) |

| < 90 | 7263 (45) | 108 (35) | 618 (38) | 2066 (42) | 3322 (47) | 1149 (55) |

| Missing | 174 (1) | 3 (<1) | 31 (2) | 48 (<1) | 62 (<1) | 30 (1) |

| HCT-CI | ||||||

| 0 | 4276 (27) | 105 (34) | 518 (32) | 1450 (29) | 1775 (25) | 428 (20) |

| 1 | 2144 (13) | 55 (18) | 240 (15) | 663 (13) | 928 (13) | 258 (12) |

| 2 | 2831 (18) | 62 (20) | 292 (18) | 911 (18) | 1213 (17) | 353 (17) |

| 3 | 2957 (18) | 43 (14) | 292 (18) | 908 (18) | 1320 (19) | 394 (19) |

| 4 | 1711 (11) | 25 (8) | 144 (9) | 494 (10) | 775 (11) | 273 (13) |

| 5 | 980 (6) | 12 (4) | 77 (5) | 283 (6) | 449 (6) | 159 (8) |

| ≥ 6 | 1093 (7) | 6 (2) | 52 (3) | 240 (5) | 568 (8) | 227 (11) |

| Missing | 7 (<1) | 0 | 0 | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 0 |

| ISS/DS stage at diagnosis | ||||||

| Stage III | 8713 (54) | 188 (61) | 949 (59) | 2697 (54) | 3811 (54) | 1068 (51) |

| Stage I-II | 6848 (43) | 117 (38) | 632 (39) | 2112 (43) | 3021 (43) | 966 (46) |

| Missing | 438 (3) | 3 (<1) | 34 (2) | 143 (3) | 200 (3) | 58 (3) |

| Cytogenetics | ||||||

| No abnormal | 3430 (21) | 73 (24) | 375 (23) | 1101 (22) | 1483 (21) | 398 (19) |

| High risk | 4398 (27) | 63 (20) | 380 (24) | 1307 (26) | 2019 (29) | 629 (30) |

| Standard risk | 4871 (30) | 98 (32) | 493 (31) | 1513 (31) | 2110 (30) | 657 (31) |

| Test not done/unknown | 3300 (21) | 74 (24) | 367 (23) | 1031 (21) | 1420 (20) | 408 (20) |

| MEL 140 | 2938 (18) | 32 (10) | 144 (9) | 475 (10) | 1064 (15) | 1223 (58) |

| MEL 200 | 13047 (82) | 276 (90) | 1468 (91) | 4473 (90) | 5962 (85) | 868 (41) |

| Unknown dose | 14 (<1) | 0 | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 6 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| Disease status prior to transplant | ||||||

| sCR/CR | 2520 (16) | 51 (17) | 269 (17) | 814 (16) | 1089 (15) | 297 (14) |

| VGPR | 6277 (39) | 117 (38) | 632 (39) | 1929 (39) | 2746 (39) | 853 (41) |

| PR | 6057 (38) | 122 (40) | 595 (37) | 1842 (37) | 2700 (38) | 798 (38) |

| SD/PD/Relapse | 1075 (7) | 18 (6) | 112 (7) | 341 (7) | 467 (7) | 137 (7) |

| Missing | 70 (<1) | 0 | 7 (<1) | 26 (<1) | 30 (<1) | 7 (<1) |

| Year of transplant | ||||||

| 2013 | 2746 (17) | 70 (23) | 327 (20) | 859 (17) | 1183 (17) | 307 (15) |

| 2014 | 2940 (18) | 60 (19) | 300 (19) | 962 (19) | 1272 (18) | 346 (17) |

| 2015 | 3034 (19) | 53 (17) | 312 (19) | 952 (19) | 1345 (19) | 372 (18) |

| 2016 | 3547 (22) | 65 (21) | 339 (21) | 1100 (22) | 1563 (22) | 480 (23) |

| 2017 | 3732 (23) | 60 (19) | 337 (21) | 1079 (22) | 1669 (24) | 587 (28) |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 25 (<1–72) | 34 (1–64) | 33 (1–71) | 27 (1–71) | 25 (1–72) | 24 (1–66) |

Legend: HCT-CI: hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index; ISS: International staging system; DSS: Durie-Salmon staging; VGPR: Very good partial response.

Non-relapse mortality

Univariate outcomes by age groups shown in Table 2 revealed that the 100-day NRM was low across all age groups including 0% in the <40 year group, 0 (0–1)% in 40–49 years, 0% in 50–59 years, 0 (0–1)% in 60–69 years and 1 (1–1)% in ≥ 70 years (p <0.01). Table 3 shows the multivariate analysis for NRM. Patients younger than age 60 had lower NRM and patients older than 70 years had similar NRM compared to the reference age group of 60–69 years. Other factors negatively associated with NRM included KPS <90, HCT-CI >0, stage III, and disease status at HCT of PR or worse.

Table 2.

Univariate outcomes. Probabilities with 95% confidence intervals are shown

| Age Group | 20–39 (n=308) | 40–49 (N=1,615) | 50–59 (N=4,952) | 60–69 (N=7,032) | ≥70 (N=2,092) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100-day non-relapse mortality | 0% | 0 (0–1)% | 0% | 0 (0–1)% | 1 (1–1)% | <0.01 |

| 2-year relapse/progression | 31 (26–37)% | 29 (27–32)% | 30 (28–31)% | 29 (28–30)% | 29 (27–32)% | 0.80 |

| 2-year progression-free survival | 68 (62–74)% | 69 (67–72)% | 68 (67–70)% | 68 (67–69)% | 66 (64–68)% | 0.44 |

| 2-year overall survival | 94 (91–97)% | 91 (90–93)% | 90 (90–91)% | 89 (88–89)% | 86 (85–88)% | <0.01 |

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of outcomes. 99% confidence intervals shown and p-value <0.01 is considered significant

| Outcome | N (Events/Evaluable) | Hazard Ratio (99% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-relapse mortality | |||

| Main effect-age | <0.01 | ||

| 60 – 69 | 189/6922 | 1.00 | |

| 40 – 49 | 23/1591 | 0.55 (0.35–0.85) | <0.01 |

| 50 – 59 | 86/4855 | 0.67 (0.52–0.87) | <0.01 |

| ≥ 70 | 75/2063 | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | 0.06 |

| Karnofsky score ≥90 | 148/8236 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| <90 | 218/7028 | 1.52 (1.23–1.88) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 7/167 | 2.65 (1.24–5.66) | 0.01 |

| HCT-Comorbidity Index 0 | 54/4093 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 1–2 | 109/4778 | 1.66 (1.20–2.30) | <0.01 |

| ≥3 | 210/6560 | 2.18 (1.61–2.95) | <0.01 |

| ISS/DSS I-II | 131/6612 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| III | 231/8398 | 1.42 (1.15–1.77) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 11/421 | 1.42 (0.77–2.63) | 0.26 |

| Disease status at AHCT, CR | 41/2460 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| VGPR | 127/6095 | 1.27 (0.90–1.81) | 0.18 |

| PR | 158/5845 | 1.67 (1.18–2.35) | <0.01 |

| <PR | 47/1031 | 2.93 (1.93–4.46) | <0.01 |

| Relapse/Progression | |||

| Main effect-age | 0.86 | ||

| 60 – 69 | 1719/6922 | 1.00 | |

| 40 – 49 | 401/1591 | 1.00 (0.90–1.12) | 0.92 |

| 50 – 59 | 1243/4855 | 1.03 (0.95–1.10) | 0.43 |

| ≥ 70 | 498/2063 | 1.03 (0.93–1.13) | 0.56 |

| ISS/DSS I-II | 1426/6612 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| III | 2331/8398 | 1.36 (1.27–1.46) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 104/421 | 1.27 (1.04–1.56) | 0.02 |

| Disease status at AHCT, CR | 530/2460 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| VGPR | 1436/6095 | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 0.03 |

| PR | 1561/5845 | 1.29 (1.17–1.42) | <0.01 |

| <PR | 334/1031 | 1.70 (1.48–1.95) | <0.01 |

| Cytogenetics, no abnormality | 66/3298 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| High risk | 1324/4263 | 1.88 (1.71–2.07) | <0.01 |

| Standard risk | 961/4717 | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 0.30 |

| Not tested/unknown | 915/3153 | 1.22 (1.09–1.36) | <0.01 |

| Year of transplant, 2017 | 454/3628 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 2013 | 829/2625 | 1.19 (1.04–1.36) | 0.01 |

| 2014 | 915/2819 | 1.18 (1.05–1.33) | <0.01 |

| 2015 | 862/2926 | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | 0.29 |

| 2016 | 801/3433 | 0.96 (0.86–1.09) | 0.54 |

| Progression-free survival | |||

| Main effect-age | 0.48 | ||

| 60 – 69 | 1908/6922 | 1.00 | |

| 40 – 49 | 424/1591 | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) | 0.45 |

| 50 – 59 | 1329/4855 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.92 |

| ≥ 70 | 573/2063 | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) | 0.24 |

| Karnofsky score ≥90 | 2170/8236 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| <90 | 2011/7028 | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 53/167 | 1.43 (1.09–1.88) | 0.01 |

| ISS/DSS I-II | 1557/6612 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| III | 2562/8398 | 1.36 (1.28–1.45) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 115/421 | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | <0.01 |

| Disease status at AHCT, CR | 571/2460 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| VGPR | 1563/6095 | 1.13 (1.03–1.25) | 0.01 |

| PR | 1719/5845 | 1.32 (1.20–1.45) | <0.01 |

| <PR | 381/1031 | 1.78 (1.57–2.03) | <0.01 |

| Cytogenetics, no abnormality | 734/3298 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| High risk | 1430/4263 | 1.82 (1.67–1.99) | <0.01 |

| Standard risk | 1061/4717 | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 0.33 |

| Not tested/unknown | 1009/3153 | 1.22 (1.09–1.35) | <0.01 |

| Year of transplant, 2017 | 502/3628 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 2013 | 909/2625 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | <0.01 |

| 2014 | 996/2819 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | <0.01 |

| 2015 | 945/2926 | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 0.14 |

| 2016 | 882/3433 | 0.98 (0.88–1.10) | 0.73 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Main effect-age | 659/6992 | <0.01 | |

| 60 – 69 | 117/1605 | 1.00 | |

| 40 – 49 | 400/4919 | 0.77 (0.63–0.94) | 0.01 |

| 50 – 59 | 227/2084 | 0.88(0.77–0.99) | 0.05 |

| ≥ 70 | 659/6992 | 1.18(1.02–1.38) | 0.03 |

| Karnofsky score ≥90 | 627/8323 | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) | <0.01 |

| <90 | 755/7108 | 1.83 (1.18–2.82) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 21/169 | 1.33 (1.19–1.48) | <0.01 |

| HCT-Comorbidity Index 0 | 304/4140 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 1–2 | 416/4831 | 1.16 (1.00–1.34) | 0.05 |

| ≥3 | 683/6629 | 1.33 (1.16–1.52) | <0.01 |

| ISS/DSS I-II | 424/6685 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| III | 944/8488 | 1.77 (1.58–1.99) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 35/427 | 1.36 (0.96–1.92) | 0.08 |

| Disease status at AHCT, CR | 173/2467 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| VGPR | 507/6148 | 1.21 (1.02–1.44) | 0.03 |

| PR | 548/5929 | 1.37 (1.15–1.62) | <0.01 |

| <PR | 175/1056 | 2.55 (2.07–3.15) | <0.01 |

| Cytogenetics, no abnormality | 215/3334 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| High risk | 523/4311 | 2.07 (1.77–2.42) | <0.01 |

| Standard risk | 262/4755 | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 0.13 |

| Not tested/unknown | 403/3200 | 1.73 (1.46–2.04) | <0.01 |

Legend: HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; ISS, International Staging System: DSS, Durie-Salmon staging; VGPR, very good partial response; CR, complete response; AHCT, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation; PR, partial response

Relapse/Progression

On univariate analysis, REL at 2 years was similar across all groups, p 0.8 (table 2). On multivariate analysis (table 3), age at transplant was also not associated with relapse/progression; stage III, disease status at HCT of VGPR or worse, presence of high-risk cytogenetics and earlier year of transplant were associated with higher relapse/progression.

Progression-free survival

At 2 years, PFS was similar across all age groups on univariate analysis, p 0.4 (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, age at transplant was not associated with worse PFS; KPS, stage, disease status, cytogenetics and year of transplant being significant predictors of PFS (Table 3).

Overall survival

At 2 years, OS was lower in the ≥70 years at 86 (85–88)% compared to the younger groups (p <0.01), Table 2. On multivariate analysis adjusted for other covariates (Table 3), age was associated with OS (p 0.0003), with patients 40–49 having lower hazards of mortality compared to 60–69 (HR 0.8, 99% CI, 0.6–0.9, p 0.01) but no significant difference for 50–59 years (HR 0.9, 99% CI, 0.8–1, p 0.05) or ≥70 years (HR 1.2, 99% CI, 1–1.4, p 0.03). Other factors associated with worse survival included KPS, HCT-CI, stage, disease status at transplant and cytogenetics.

Subset analysis studying the effect of Melphalan dose in patients ≥70 years

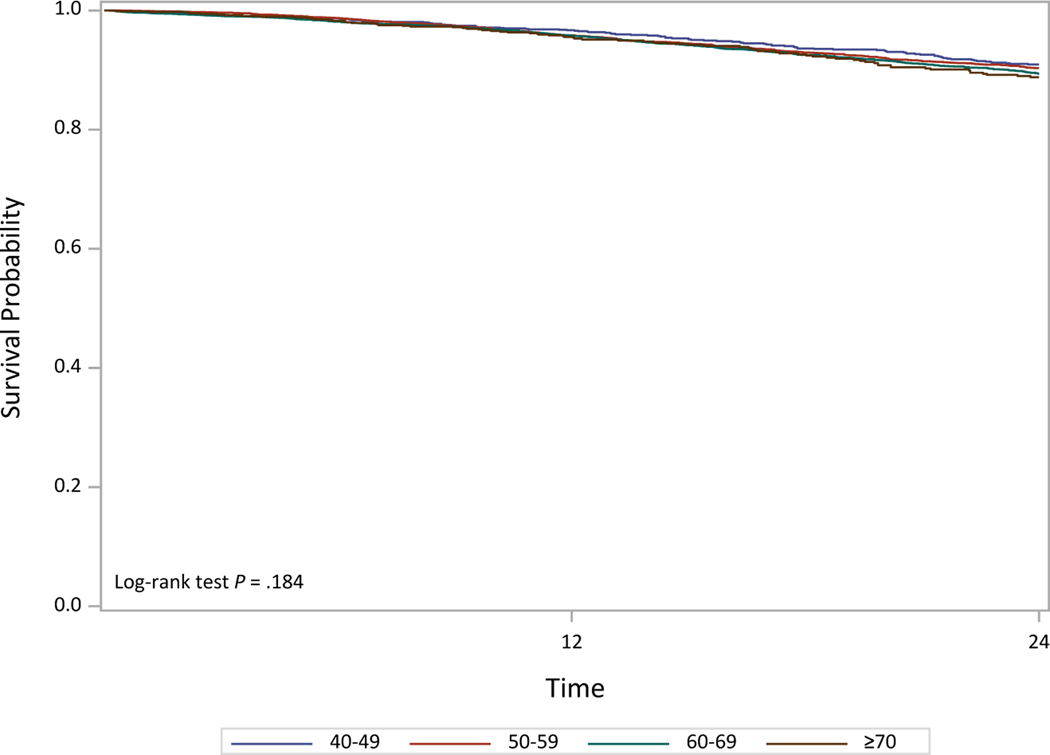

We studied the effect of melphalan conditioning dose in patients aged ≥70 years. Most patients (N=1,223) received reduced Mel 140 mg/m2 (Mel 140) while 868 patients received Mel 200 mg/m2 (Mel 200). The overall NRM on univariate analysis was worse in the Mel 140 group compared to Mel 200 (p 0.003). Both PFS and OS were better in the Mel 200 group compared to Mel 140. On multivariate analysis, Mel 140 was associated with a worse NRM with HR 2.2, 95% CI, 1.3–3.7, p 0.003 compared to Mel 200. Similarly, both PFS and OS were worse among the ≥70 year patients with Mel 140 compared to Mel 200 (Figure 1, Table 4). Among patients who received Mel 200, there was no difference in overall survival by age group (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Outcomes in ≥70 year old adults by melphalan dose

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of outcomes in ≥70 year old adults

| N (Events/Evaluable) | Hazard Ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-relapse mortality | |||

| Melphalan dose, 200mg/m2 | 19/857 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 140 mg/m2 | 56/1206 | 2.22 (1.31–3.73) | |

| Relapse/Progression | |||

| Melphalan dose, 200 mg/m2 | 194/857 | 1.00 | 0.10 |

| 140 mg/m2 | 304/1206 | 1.17 (0.97–1.40) | |

| Cytogenetics, no abnormality | 73/394 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| High-risk | 190/621 | 1.97 (1.50–2.58) | <0.01 |

| Standard risk | 129/649 | 1.13 (0.85–1.51) | 0.40 |

| Not tested/unavailable | 106/399 | 1.25 (0.93–1.68) | 0.15 |

| Progression-free survival | |||

| Melphalan dose, 200 mg/m2 | 213/857 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| 140 mg/m2 | 360/1206 | 1.26 (1.06–1.49) | |

| Cytogenetics, no abnormality | 87/394 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| High-risk | 210/621 | 1.80 (1.41–2.32) | <0.01 |

| Standard risk | 153/649 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) | 0.40 |

| Not tested/unavailable | 123/399 | 1.23 (0.93–1.61) | 0.15 |

| Overall survival | |||

| Melphalan dose, 200 mg/m2 | 77/864 | 1.00 | 0.02 |

| 140 mg/m2 | 150/1220 | 1.40 (1.06–1.84) | |

| ISS/DSS stage, I-II | 83/964 | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| III | 139/1063 | 1.57 (1.20–2.07) | <0.01 |

| Missing | 5/57 | 1.22 (0.49–3.01) | 0.67 |

Legend: ISS, International Staging System; DSS, Durie-Salmon staging.

Figure 2.

Overall survival for Mel 200 patients by age groups

Cause of death

A total of 2,356 deaths were seen among the entire cohort of 15,999. The cause of death was MM in 72% of <40 years, 80% 40–49 years, 80% in 50–59 years, 72% in 60–69 years and 68% in ≥ 70 years. More patients were reported to die of organ failure (5%) and secondary malignancy (4%) in ≥ 70 years compared to younger patients.

Discussion

In this large database study capturing the majority of autologous transplant activity when used in upfront therapy in MM in the US in recent years, we make the following observations: 1. Transplants conducted among patients aged 70 and older continue to increase each year with 28% of all MM AHCT in 2017 compared to 15% in 2013, 2. Age ≥ 70 years was not associated with adverse outcomes in MM post-HCT compared to the reference group 60–69 years age, 3. Mel 200 use in ≥ 70 years was associated with superior outcomes, likely representing that the choice of Mel 140 was based on frailty and lastly, 4. MM remains the predominant cause of death across all age groups.

The use of upfront AHCT in newly diagnosed MM in the era of proteasome inhibitor and immunomodulatory agent-based induction therapies remains an important strategy to induce a deep and durable response.[5] Yet, prior work done by our group calculating the stem cell utilization rate using CIBMTR data and SEER incidence data have shown that only a minority of MM patients receive an AHCT in the United States.[6 7] Our current data show that with every age decade group, fewer non-White patients receive transplant in the US.

The ≥ 70 years age group differed in some criteria compared to younger patients. More patients in this group had KPS <90 and HCT-CI score > 2. However, no difference was seen with respect to stage or high-risk cytogenetics in older adults compared to younger adults. As expected, more melphalan conditioning dose reductions were seen in the ≥ 70 years group and 59% received reduced dose melphalan. Still, 41% received Mel 200 mg/m2 in this group. Further, on a separate multivariate analysis focused on the ≥ 70 years group, the use of Mel 200 was associated with superior PFS and OS compared to reduced dose melphalan, as well as lower day 100 transplant-related mortality. This finding implies that perhaps patient selection based on frailty or tolerability led to melphalan dose reductions. Reasons why melphalan dose was reduced are not available in our analysis although 36% of these older patients had an HCT-CI score ≥3. This further implies that ‘sicker’ patients are expected to have higher NRM after AHCT, irrespective of complications related to AHCT. Notwithstanding the higher potential for toxicities when using Mel 200 vs. Mel140 in patients ≥ 70 years and without understanding further the choice between Mel 140 vs Mel 200 dose beyond KPS and HCT-CI in our dataset, it is not possible to recommend Mel 200 over Mel 140 in older adults based on our study; though our results provide assurance that Mel 200 can indeed be given safely in some older adults aged 70 and older. Our data also suggest the importance of frailty assessment tools in individualizing treatment in older MM patients.[15]

In our current analysis, patients ≥ 70 years, have shorter survival than younger patients, though using a narrower confidence interval (99% with p <0.01 for significance) showed no significant difference compared to the standard reference group 60–69 years. Survival was even shorter when compared to MM patients < 50 years. However, this is expected given that life expectancy of the general US population at age 70 is 14.4 years for males and 16.6 years for females, and at 75 years is 11.2 years for males and 13 years for females compared to the life expectancy of 29.7 years for males and 33.3 years for females at age 50.[16] To note, recent SEER data analysis showed the cost-effectiveness of AHCT in the era of novel agents in elderly patients (>65 years) compared to those not undergoing AHCT, with an overall survival benefit (58 months in AHCT versus 37 months non-AHCT, p <0.001).[17] We are unable to study the tolerability of maintenance therapy in this age group and how it may impact survival in older MM patients.

Older patients are often excluded from clinical trials,[18] particularly transplant trials, either due to ineligibility or physician decision regardless of eligibility. There are no randomized data studying AHCT in newly diagnosed MM patients in the ≥70 years age group. The recent large US randomized study of upfront AHCT showed a median age 56 years[19] and 59 years in a CIBMTR trends analysis.[20] Given the median age of myeloma being 69 years, clinical trials of AHCT exclude the majority of MM patients and perhaps the overwhelming majority of non-White racial/ethnic groups.[21] Another important aspect of management unique to the US compared to Europe, is the management of MM predominantly in the non-transplant based community oncology practice. The use of transplant is thus dependent on a referral to a transplant center. This referral may not happen for many reasons- socioeconomic, bias, distance from transplant center, among others. The Veterans Administration (VA) has shown that providing equal care leads to removal of disparities with no difference in transplant utilization by race, though only ~10% of VA patients received transplantation for myeloma.[22] Finally, the American Cancer Society estimates about 30,770 new cases of multiple myeloma in 2018;[23] with a median age of 69 years at diagnosis, reflecting approximately 15,000 patients aged 70 or older. Our study averages approximately 400 patients ≥ 70 years undergoing AHCT in a year, thus representing ≤3% patients in this age group.

Our study has some limitations inherent to a database study. Since our database only includes patients that received a transplant, we cannot make any inferences on the patients who did not get transplant, e.g. they were referred but deemed ineligible for AHCT. That is unlikely as data show that once patients are seen and evaluated at transplant center, there is no racial difference in patients who do or don’t undergo AHCT.[24] Another potential limitation is that our study was restricted to upfront AHCT. It is possible, though unlikely, that patients ≥ 70 years who delay transplant at diagnosis, would then actually receive transplant at relapse given that they would be even older and less fit. Our study has short follow-up of only a median of 2 years and does not include details about maintenance therapy following AHCT. Lastly, there may be other important assessments focused on functional age such as comprehensive geriatric assessment, frailty index, etc. which would help determine melphalan dose etc. but are not available.

In conclusion, our data which represent the largest study of older adults ≥ 70 years receiving transplant for MM, show that while more patients ≥ 70 years are receiving AHCT for MM in the U.S. in recent years, these are predominantly excluding minorities. Further our data highlight that transplant remains a safe consolidation therapy across all age groups of myeloma patients, and that the anti-myeloma effects are not affected by age at transplant. Older age (≥70 years) should not be a barrier to referral or performing AHCT for myeloma patients and where possible, full dose melphalan should be used.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Acknowledgements

The CIBMTR is supported primarily by Public Health Service U24CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); U24HL138660 from NHLBI and NCI; OT3HL147741, R21HL140314, K23HL141445, and U01HL128568 from the NHLBI; HHSH250201700006C, SC1MC31881–01-00 and HHSH250201700007C from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); and N00014–18-1–2850, N00014–18-1–2888, and N00014–20-1–2705 from the Office of Naval Research; Additional federal support is provided by P01CA111412, R01CA152108, R01CA215134, R01CA218285, R01CA231141, R01HL126589, R01AI128775, R01HL129472, R01HL130388, R01HL131731, U01AI069197, U01AI126612, and BARDA. Support is also provided by Be the Match Foundation, Boston Children’s Hospital, Dana Farber, Japan Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Data Center, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, the National Marrow Donor Program, the Medical College of Wisconsin and from the following commercial entities: AbbVie; Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies; Adienne SA; Allovir, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anthem, Inc.; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc.; bluebird bio, Inc.; Bristol Myers Squibb Co.; Celgene Corp.; Chimerix, Inc.; CSL Behring; CytoSen Therapeutics, Inc.; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.; Gamida-Cell, Ltd.; Genzyme; GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Biotech, Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Janssen/Johnson & Johnson; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; Kite Pharma; Kyowa Kirin; Legend Biotech; Magenta Therapeutics; Mallinckrodt LLC; Medac GmbH; Merck & Company, Inc.; Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; Mesoblast; Millennium, the Takeda Oncology Co.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; Novartis Oncology; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Omeros Corporation; Oncoimmune, Inc.; Orca Biosystems, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc.; Phamacyclics, LLC; Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; REGiMMUNE Corp.; Sanofi Genzyme; Seattle Genetics; Sobi, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Takeda Pharma; Terumo BCT; Viracor Eurofins and Xenikos BV. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

All other authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Attal M, Richardson PG, Moreau P. Drug Combinations with Transplantation for Myeloma. The New England journal of medicine 2017;377(1):93–94 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1705671[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology 2015;16(16):1617–29 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00389-7[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine 2014;371(10):895–905 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402888[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavo M, Palumbo A, Zweegman S, et al. Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/Ho95 MM trial). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016;34(15) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.8000[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. The New England journal of medicine 2017;376(14):1311–20 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611750[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schriber JR, Hari PN, Ahn KW, et al. Hispanics have the lowest stem cell transplant utilization rate for autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in the United States: A CIBMTR report. Cancer 2017;123(16):3141–49 doi: 10.1002/cncr.30747[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costa LJ, Huang JX, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2015;21(4):701–6 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.024[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa LJ, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous transplantation as early therapy for multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2013;19(11):1615–24 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.08.002[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/, based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2019., 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa LJ, Brill IK, Omel J, Godby K, Kumar SK, Brown EE. Recent trends in multiple myeloma incidence and survival by age, race, and ethnicity in the United States. Blood Adv 2017;1(4):282–87 doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016002493[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhakal B, Nelson A, Guru Murthy GS, et al. Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients With Multiple Myeloma: Effect of Age. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia 2017;17(3):165–72 doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.11.006[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muchtar E, Dingli D, Kumar S, et al. Autologous stem cell transplant for multiple myeloma patients 70 years or older. Bone marrow transplantation 2016;51(11):1449–55 doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.174[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Souza A, Fretham C. Current Uses and Outcomes of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT): CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2018. Available at https://www.cibmtr.org, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Souza A, Lee S, Zhu X, Pasquini M. Current Use and Trends in Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in the United States. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2017;23(9):1417–21 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.05.035[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelhardt M, Ihorst G, Duque-Afonso J, et al. Structured assessment of frailty in multiple myeloma as a paradigm of individualized treatment algorithms in cancer patients at advanced age. Haematologica 2020;105(5):1183–88 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.242958[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html. Secondary https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html 2016.

- 17.Shah GL, Winn AN, Lin PJ, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Elderly Patients with Multiple Myeloma using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare Database. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2015;21(10):1823–9 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.013[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludmir EB, Mainwaring W, Lin TA, et al. Factors Associated With Age Disparities Among Cancer Clinical Trial Participants. JAMA Oncol 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2055[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stadtmauer EA, Pasquini MC, Blackwell B, et al. Autologous Transplantation, Consolidation, and Maintenance Therapy in Multiple Myeloma: Results of the BMT CTN 0702 Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2019;37(7):589–97 doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00685[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Souza A, Zhang MJ, Huang J, et al. Trends in pre- and post-transplant therapies with first autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation among patients with multiple myeloma in the United States, 2004–2014. Leukemia 2017;31(9):1998–2000 doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.185[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa LJ, Hari PN, Kumar SK. Differences between unselected patients and participants in multiple myeloma clinical trials in US: a threat to external validity. Leukemia & lymphoma 2016;57(12):2827–32 doi: 10.3109/10428194.2016.1170828[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fillmore NR, Yellapragada SV, Ifeorah C, et al. With equal access, African American patients have superior survival compared to white patients with multiple myeloma: a VA study. Blood 2019;133(24):2615–18 doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000406[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.2014 http://www.cancer.org/cancer/multiplemyeloma/detailedguide/multiple-myeloma-key-statistics.

- 24.Schriber J, Bean C, Simpson E, et al. No Differences in Stem Cell Transplantation Utilization Rates (STUR) By Ethnicity after Referral to a Transplant Center for Multiple Myeloma (MM): Implications for Improving Stur Rates in Minorities. Blood and Marrow Transplantation Tandem Meeting. Orlando, FL: Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2017. [Google Scholar]