Abstract

Psychostimulants, including amphetamines and methylphenidate, are first-line pharmacotherapies for individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This review aims to educate physicians regarding differences in pharmacology and mechanisms of action between amphetamine and methylphenidate, thus enhancing physician understanding of psychostimulants and their use in managing individuals with ADHD who may have comorbid psychiatric conditions. A systematic literature review of PubMed was conducted in April 2017, focusing on cellular- and brain system–level effects of amphetamine and methylphenidate. The primary pharmacologic effect of both amphetamine and methylphenidate is to increase central dopamine and norepinephrine activity, which impacts executive and attentional function. Amphetamine actions include dopamine and norepinephrine transporter inhibition, vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2) inhibition, and monoamine oxidase activity inhibition. Methylphenidate actions include dopamine and norepinephrine transporter inhibition, agonist activity at the serotonin type 1A receptor, and redistribution of the VMAT-2. There is also evidence for interactions with glutamate and opioid systems. Clinical implications of these actions in individuals with ADHD with comorbid depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, and sleep disturbances are discussed.

Keywords: amphetamine, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, methylphenidate, pharmacology

1.0. Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was initially identified in children (1) but is now understood to persist into adulthood in about two thirds of cases (2-4). In a 2007 meta-analysis that included more than 100 studies, the estimated worldwide prevalence of ADHD in individuals <18 years old was 5.29% (5). The estimated prevalence in adults was 4.4% in a national survey in the United States (6), 3.4% in a 10-nation survey (7), and 2.5% in a meta-regression analysis of 6 studies (8).

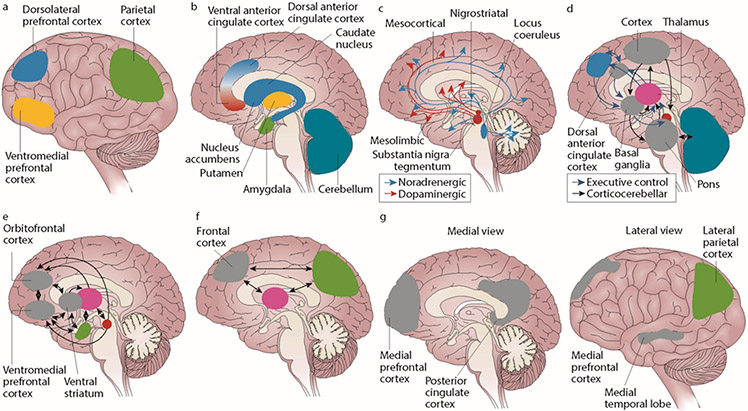

A large body of evidence suggests that multiple neurotransmitters and brain structures play a role in ADHD (9-11). Although a substantial amount of research has focused on dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE), ADHD has also been linked to dysfunction in serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]), acetylcholine (ACH), opioid, and glutamate (GLU) pathways (10, 12-15). The alterations in these neurotransmitter systems affect the function of brain structures that moderate executive function, working memory, emotional regulation, and reward processing (Figure 1) (11).

Figure 1. Brain Mechanisms in ADHD*.

(a) The cortical regions (lateral view) of the brain have a role in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is linked to working memory, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to complex decision making and strategic planning, and the parietal cortex to orientation of attention. (b) ADHD involves the subcortical structures (medial view) of the brain. The ventral anterior cingulate cortex and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex subserve affective and cognitive components of executive control. Together with the basal ganglia (comprising the nucleus accumbens, caudate nucleus, and putamen), they form the frontostriatal circuit. Neuroimaging studies show structural and functional abnormalities in all of these structures in patients with ADHD, extending into the amygdala and cerebellum. (c) Neurotransmitter circuits in the brain are involved in ADHD. The dopamine system plays an important part in planning and initiation of motor responses, activation, switching, reaction to novelty, and processing of reward. The noradrenergic system influences arousal modulation, signal-to-noise ratios in cortical areas, state-dependent cognitive processes, and cognitive preparation of urgent stimuli. (d) Executive control networks are affected in patients with ADHD. The executive control and cortico-cerebellar networks coordinate executive functioning (ie, planning, goal-directed behavior, inhibition, working memory, and the flexible adaptation to context). These networks are underactivated and have lower internal functional connectivity in individuals with ADHD compared with individuals without the disorder. (e) ADHD involves the reward network. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and ventral striatum are at the center of the brain network that responds to anticipation and receipt of reward. Other structures involved are the thalamus, the amygdala, and the cell bodies of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, which, as indicated by the arrows, interact in a complex manner. Behavioral and neural responses to reward are abnormal in ADHD. (f) The alerting network is impaired in ADHD. The frontal and parietal cortical areas and the thalamus intensively interact in the alerting network (indicated by the arrows), which supports attentional functioning and is weaker in individuals with ADHD than in controls. (g) ADHD involves the default-mode network (DMN). The DMN consists of the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex (medial view) as well as the lateral parietal cortex and the medial temporal lobe (lateral view). DMN fluctuations are 180° out of phase with fluctuations in networks that become activated during externally oriented tasks, presumably reflecting competition between opposing processes for processing resources. Negative correlations between the DMN and the frontoparietal control network are weaker in patients with ADHD than in people who do not have the disorder.

*Reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: [NAT REV DIS PRIMERS] (Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 Aug 6;1:15020), copyright 2015.

Individuals with ADHD are often diagnosed with additional psychiatric comorbidities, including anxiety, mood, substance use, sleep disturbances, and antisocial personality disorders (16-18). Importantly, the neurobiological substrates that mediate behaviors associated with ADHD share commonalities to some extent with those involved in these comorbid disorders (19-21). Genetic studies have also identified shared genetic risk factors between ADHD and associated comorbid disorders (22, 23). As such, comorbidities need to be taken into account when considering pharmacotherapy in an individual with ADHD.

Although stimulants (including amphetamine [AMP]–based and methylphenidate [MPH]–based agents) and nonstimulants (eg, atomoxetine, clonidine, and guanfacine) are approved for the treatment of ADHD (24), stimulants are considered first-line therapy in children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD because of their greater efficacy (25-30). AMP and MPH have been shown to exhibit comparable efficacy in 2 meta-analyses (31, 32), with other analyses reporting that AMP has moderately greater effects than MPH (33-35). The tolerability and safety profiles of AMP and MPH in terms of adverse events, treatment discontinuation, and cardiovascular effects are also generally comparable (36-38), although weight loss and insomnia have been reported to be more common with AMP than with MPH (32). Additional work is planned that will further compare the efficacy, tolerability, and safety profiles of different pharmacologic interventions in children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD (39).

Although increased synaptic availability of DA and NE is a key result of exposure to both AMP and MPH (40, 41), differences in the specific cellular mechanisms of action of AMP and MPH may influence their effects on the neurobiological substrates of ADHD and response to treatment in individuals with ADHD as well as their effects on common comorbidities, such as depression and anxiety.

The objective of this review is to educate physicians about the mechanisms of action of AMP and MPH and the implications of these actions on the management of ADHD and its comorbidities. To achieve this goal, a systematic review of the published literature was conducted to obtain articles describing the cellular- and brain system–level effects of AMP and MPH. The results of relevant studies are described and interpreted in the context of the treatment of ADHD and in light of the comorbidities associated with ADHD.

2.0. Methods

A systematic literature review of PubMed was conducted on April 24, 2017; no limits were included for publication year or the language of publication. The search consisted of titles and abstracts and used the following search string: (amphetamine [MESH term] OR methylphenidate [MESH term]) AND (cellular OR receptor binding OR neuroimaging OR FMRI OR SPECT OR PET OR positron emission tomography OR magnetic resonance OR tomography OR spectroscopy) AND (dopamine OR serotonin OR norepinephrine OR acetylcholine OR glutamate OR opioid OR opiate) NOT (methamphetamine OR MDMA OR ecstasy OR addiction OR abuse). The literature search included both animal and human studies.

Additional articles of interest were obtained via an assessment of the relevant articles obtained through the literature review and based on author knowledge. A publication was excluded if it did not specifically focus on the mechanism of action or pharmacologic effects of AMP or MPH or if it was an imaging study in individuals who were other than healthy (ie, studies in those with psychiatric disorders were not included).

3.0. Results

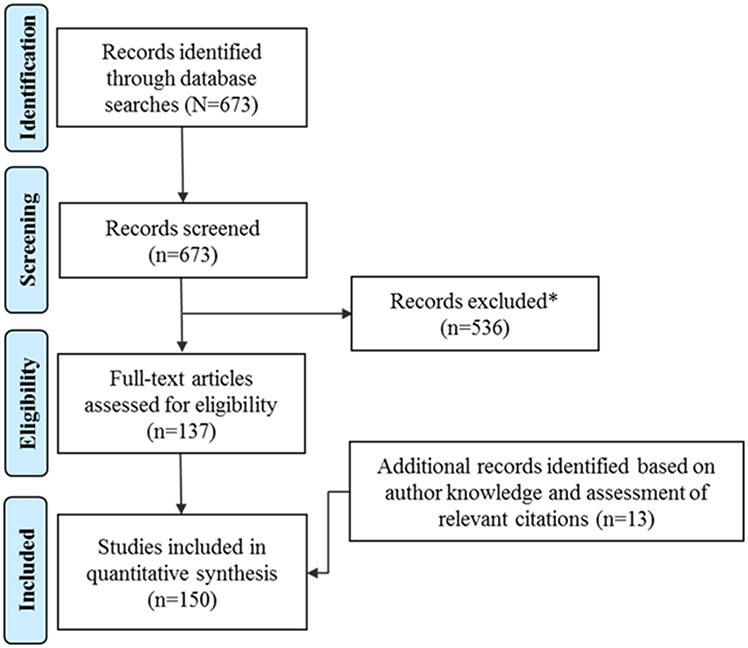

The literature search yielded 673 articles (Figure 2). Of these, 137 were considered relevant to the topic of this review. Additional articles (n=13) were identified based on author knowledge and assessment of the reference sections of relevant citations. The articles included in this review are summarized in Table 1 (42-191).

Figure 2. PRISMA Flow Diagram of the Literature Search.

*Publications were excluded if they did not focus on the mechanism of action or pharmacologic effects of amphetamine or methylphenidate or if the publications were imaging studies in individuals who were not healthy (ie, studies in those with psychiatric disorders were not included).

Table 1.

Studies of the Actions of AMP and MPH

| Preclinical studies | |

| Amphetamine | |

| al-Tikriti et al (42) | • AMP increased the washout rate of [123I]IBF (a D2 receptor antagonist) from the striatum of baboons, as measured using SPECT |

| Annamalai et al (43) | • AMP-stimulated downregulation of the NET was linked to the PKC-resistant T258/S259 structural motif and mediated by reduced plasma membrane insertion and enhanced endocytosis |

| Avelar et al (44) | • AMP increased electrically evoked DA levels, inhibited DA uptake, and upregulated DA vesicular release in rat striatum |

| Bjorklund et al (45) | • Adenosine A3 receptor knockout mice exhibited reduced locomotor responses to AMP, suggesting potential alterations in monoaminergic (DA, 5-HT, or NE) systems |

| Carson et al (46) | • AMP reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of rhesus monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Castner et al (47) | • AMP reduced [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of rhesus monkeys, as measured by SPECT |

| Chen et al (48) | • AMP-induced increases in whole-brain relative cerebral blood volume were attenuated by electroacupuncture (electrical paw stimulation) in rats |

| Chen et al (49) | • Rapid AMP-induced increases in striatal surface DAT levels and DA release in mice were not observed in PKC-β knockout mice |

| Choe et al (50) | • AMP increased phosphorylation of CREB in rats; intrastriatal administration of PHCCC (an mGluR type 1 antagonist) and systemic administration of MPEP (an mGluR type 5 antagonist) attenuated this effect |

| Chou et al (51) | • AMP reduced [11C]FLB 457 (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the thalamus, cortex, and striatum of cynomolgus monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Covey et al (52) | • AMP increased DA release in rat striatum when administered with a short-duration electrical stimulus and decreased DA release when administered with a long-duration electrical stimulus |

| Dewey et al (53) | • AMP decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of baboons, as measured by PET |

| Dixon et al (54) | • AMP caused widespread increases in fMRI BOLD signal intensity in subcortical structures containing rich DA innervation, with decreases in BOLD signal observed in the superficial layers of the cortex in rats |

| Drevets et al (55) | • AMP-induced reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in baboons were greater in the anteroventral striatum than in the dorsal striatum, as measured by PET |

| Duttaroy et al (56) | • Chronic AMP exposure blocked naloxone-induced supersensitivity of μ- and δ-opioid receptors without altering naloxone-induced upregulation of these receptors in mice |

| Easton et al (57) | • AMP isomers increased DA release (basal and electrically stimulated) in the nucleus accumbens, medial entorhinal cortex, colliculi, hippocampal area CA1, and thalamic nuclei of rats |

| Easton et al (58) | • AMP inhibited accumulation of DA or NE in rat brain synaptosomes and vesicles, which was mitigated by inhibitors of the DAT and NET |

| Finnema et al (59) | • AMP reduced binding of [11C]ORM-13070 (an adrenergic α2c receptor antagonist) in the striatum of cynomolgus monkeys, as measured by PET, and increased rat striatal NE and DA concentrations |

| Floor and Meng (60) | • Low AMP concentrations increased DA release from rat brain synaptic vesicles independent of vesicular alkalinization; high-AMP-concentration DA release was reduced as a function of the proton gradient |

| Gallezot et al (61) | • AMP reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) and [11C]PHNO (a D2/D3 receptor agonist) binding in the striatum, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra of rhesus monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Ginovart et al (62) | • Chronic AMP administration (14 days) was associated with an increased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding affinity after 1 day of drug withdrawal and with binding after 7 and 14 days of withdrawal in cynomolgus monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Hartvig et al (63) | • AMP increased DA biosynthesis in the brain in nonhuman primates, as measured by PET |

| Helmeste and Seeman (64) | • Mice with high D2 receptor density in the striatum and olfactory tubercle exhibited hypolocomotion in response to low-dose AMP, whereas mice with low D2 receptor density were nonresponsive to AMP |

| Howlett and Nahorski (65) | • AMP exposure increased [3H]spiperone (a D2/D3 receptor antagonist) binding affinity and density after 4 days of exposure and decreased binding density after 20 days of exposure in rat striatum |

| Inderbitzin et al (66) | • AMP increased preprodynorphin mRNA expression and κ-opioid receptor binding in the basal ganglia of rats |

| Jedema et al (67) | • AMP increased DA release in the caudate and prefrontal cortex of rhesus macaques, as measured using microdialysis, with DA levels remaining elevated for a longer duration in the prefrontal cortex than in the caudate |

| Joyce et al (68) | • Administration of a combination of mixed amphetamine salts directly into the striatum of rats stimulated DA release |

| Kashiwagi et al (69) | • AMP increased relative cerebral blood volume in awake and anesthetized rats, with changes correlated to changes in striatal DA concentration |

| Konradi et al (70) | • AMP-induced activation of immediate early genes in dissociated rat striatal cultures was blocked by MK-801 (an NMDA receptor antagonist) |

| Kuczenski and Segal (71) | • AMP increased DA and 5-HT efflux in the caudate and NE efflux in the hippocampus of rats following systemic administration |

| Lahti and Tamminga (72) | • AMP increased D2 receptor occupancy in the cortex and caudate of rats, as measured by receptor autoradiography |

| Landau et al (73) | • AMP decreased binding of [11C]yohimbine (an adrenergic ɑ2 receptor antagonist) in the thalamus, cortex, and caudate of pigs, as measured by PET |

| Laruelle et al (74) | • AMP reduced [123I]IBZM and [123I]IBF (D2 receptor antagonists) in vervets (nonhuman primates), as measured by SPECT, with binding changes correlating with peak DA release as measured by microdialysis |

| Le Masurier et al (75) | • AMP-reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of rats, as measured by PET, was attenuated by pretreatment with a tyrosine-free amino acid mixture |

| Lind et al (76) | • AMP decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the caudate, putamen, and ventral striatum of pigs, as measured by PET |

| Liu et al (77) | • AMP increased cytosolic calcium concentrations and NE release in a dose-dependent and extracellular calcium-dependent manner in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells; nicotinic receptor antagonists suppressed these effects • AMP acted as a nicotinic receptor agonist to induce calcium increases and NE release in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells |

| May et al (78) | • AMP stimulated DA release in the caudate nucleus of rats, as measured by in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry |

| Miller et al (79) | • AMP inhibited MAO type A activity |

| Mukherjee et al (80) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of rats and monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Patrick et al (81) | • Stimulation of DA synthesis in rat brain striatal synaptosomes produced by the depolarizing agent veratridine markedly reduced AMP, suggesting AMP altered interactions between tyrosine hydroxylase and the synaptosomes regulating catecholamine formation |

| Pedersen et al (82) | • AMP-induced decreases in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the dorsal and ventral striatum of rats were not altered by pretreatment with pargyline, as measured using PET |

| Preece et al (83) | • AMP reduced BOLD signal intensity in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex and increased signal intensity in the motor cortex of rats as measured by fMRI; the signal intensity changes in the nucleus accumbens and caudate (but not in the motor cortex) were attenuated by pretreatment with a tyrosine-free amino acid mixture |

| Price et al (84) | • After administration of AMP, a general increase in CBF that gradually declined toward baseline values was observed using a bolus injection PET method in baboons |

| Pum et al (85) | • AMP dose-dependently increased DA and 5-HT levels in the perirhinal, entorhinal, and prefrontal cortices |

| Quelch et al (86) | • AMP reduced [3H]carfentanil (a μ-opioid receptor antagonist) binding in rat total brain homogenate, as measured by subcellular fractionation, and in the superior colliculi, hypothalamus, and amygdala of rats, as measured by in vivo receptor binding |

| Ren et al (87) | • AMP increased DA release in the caudate/putamen and cAMP activity in the caudate/putamen, nucleus accumbens, and medial prefrontal cortex in rats |

| Riddle et al (88) | • Administration of low-dose AMP altered VMAT-2 distribution within nerve terminals selectively in monoaminergic neurons |

| Ritz and Kuhar (89) | • AMP exhibited high affinity for DA, NE, and 5-HT reuptake sites and for α2 adrenergic receptor sites, as measured using in vivo binding in rats |

| Robinson (90) | • AMP enantiomers (d and l) inhibited MAO type A and MAO type B activity in rat liver mitochondria |

| Saelens et al (91) | • AMP increased [3H]spiroperidol (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in regions containing DA terminals (eg, the septum, nucleus accumbens, cortex, caudate-putamen) or dendrites (eg, ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra), as measured by in vivo receptor binding |

| Schwarz et al (92) | • AMP produced widespread increases in regional CBF in multiple brain region clusters that are involved in primary DA pathways in rats |

| Schwendt et al (93) | • AMP decreased RGS4 mRNA in the caudate-putamen and cortex and RGS4 protein levels in the caudate-putamen of rats but did not modify the effects of SCH 23390 or eticlopride (D2 receptor antagonists) on RGS4 mRNA or protein levels in these same brain regions |

| Schiffer et al (94) | • AMP elevated extracellular DA in the striatum but to a greater degree than MPH; reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding were similar with AMP and MPH |

| Seneca et al (95) | • AMP reduced binding of [11C]MNPA and [11C]raclopride (D2 receptor antagonists) in the striatum of cynomolgus monkeys, as measured by PET |

| Shaffer et al (96) | • AMP reduced striatal and increased medial prefrontal cortical protein expression of mGluR type 5 in rats |

| Skinbjerg et al (97) | • AMP-induced decreases in [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding were associated with receptor internalization, as assessed using PET in knockout mice lacking the ability to internalize D2 receptors |

| Smith et al (98) | • Melanin-concentrating hormone type 1 receptor knockout mice exhibited an increased locomotor response to AMP but did not exhibit altered DA, NE, or 5-HT release in the striatum in response to AMP |

| Sulzer et al (99) | • AMP produced a rapid release of DA from vesicles, resulting in redistribution to the cytosol |

| Sulzer and Rayport (100) | • AMP reduced the pH gradient in rat chromaffin cells, resulting in reduced DA uptake |

| Sun et al (101) | • AMP decreased binding of [3H]raclopride but not of [3H]spiperone (D2 receptor antagonists) in rat striatum |

| Tomic et al (102) | • AMP decreased [3H]SCH 23390 (a D1 receptor antagonist) binding in the caudate and nucleus accumbens, increased [3H]SCH 23390 binding in the substantia nigra, and decreased [3H]spiperone (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum and nucleus accumbens in rats, as measured using autoradiography |

| Tomic and Joksimovic (103) | • Acute treatment with AMP reduced [3H]SCH 23390 (a D1 receptor antagonist) and [3H]spiperone (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum and nucleus accumbens in rats, as measured by autoradiography |

| van Berckel et al (104) | • AMP-induced decrease in [3H]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of baboons was enhanced by LY354740 (an mGluR type 2/3 receptor agonist), as measured by PET |

| Xiao and Becker (105) | • AMP-induced striatal DA release in rats was increased by catechol estrogens, as measured using in vivo microdialysis |

| Yin et al (106) | • AMP produced time-dependent changes in levels of GABA, 5-HT, and NE in the cerebellar vermis of mice |

| Young et al (107) | • AMP increased DA concentrations in the striatum, but not in the cortex or ventral tegmental area, in prairie voles |

| Yu et al (108) | • AMP enhanced the cellular response of cortical and hippocampal neurons to CHPG (an mGluR type 5 agonist) in rats |

| Methylphenidate | |

| Andrews and Lavin (109) | • Intracortical MPH increased cortical cell excitability in rats, an effect that was lost following catecholamine depletion and was mediated via stimulation of α2 adrenergic receptors but not D1 receptors |

| Bartl et al (110) | • MPH exerted diverse cellular effects including increased neurotransmitter levels, downregulated synaptic gene expression, and enhanced cell proliferation in rat pheochromocytoma cells |

| Ding et al (111) | • MPH reduced binding of [11C]dl-threo-MPH in the striatum of baboons, as measured by PET |

| Ding et al (112) | • MPH reduced binding of [11C]d-threo-MPH (but not [11C]l-threo-MPH) in the striatum of baboons, as measured by PET |

| Dresel et al (113) | • MPH reduced [99Tc]TRODAT-1 (a DAT/SERT ligand) binding to DAT in the striatum, but not to the SERT in the midbrain/hypothalamus in baboons, as measured by PET |

| Easton et al (58) | • MPH inhibited accumulation of DA or NE in rat brain synaptosomes and vesicles, with greater potency observed for synaptosomal inhibition |

| Federici et al (114) | • MPH reduced spontaneous firing of DA neurons, as measured by electrophysiologic recordings in rat brain slices, via blockade of the DAT |

| Gamo et al (115) | • MPH increased performance on a spatial working memory task in rhesus monkeys, an effect that was blocked by the α2 adrenergic antagonist idazoxan |

| Gatley et al (116) | • [11C]d-threo-MPH exhibited high affinity for the DAT that was insensitive to competition with endogenous DA in baboons, as measured by PET; the highest concentrations of [11C]d-threo-MPH binding in mouse brain were found in striatum |

| Gatley et al (117) | • MPH reduced [3H]cocaine (a DAT agonist) binding in the olfactory tubercle and striatum in mice, as measured by PET |

| Gatley et al (118) | • MPH exhibited higher affinities for the DAT and NET than for the serotonin transporter in rat brain |

| Kuczenski and Segal (71) | • MPH increased DA efflux in the caudate and NE efflux in the hippocampus of rats following systemic administration |

| Markowitz et al (119) | • MPH acted as an agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor in guinea pig ileum |

| Markowitz et al (120) | • MPH exhibited affinity at the NET and DAT and at 5-HT1A and 5-HT2B receptors |

| Michaelides et al (121) | • MPH differentially altered metabolism in the prefrontal cortex and cerebellar vermis as a function of DA D4 receptor functionality in mice |

| Nikolaus et al (122) | • MPH reduced [123I]FP-CIT (a DAT ligand) binding in rat striatum, as measured by SPECT |

| Nikolaus et al (123) | • MPH dose-dependently reduced [123I]FP-CIT (a DAT ligand) binding in rat striatum, as measured by SPECT |

| Nikolaus et al (124) | • MPH decreased [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of rats, as measured by SPECT |

| Riddle et al (88) | • Administration of low-dose MPH altered VMAT-2 distribution within nerve terminals selectively in monoaminergic neurons |

| Sandoval et al (125) | • MPH increased vesicular DA uptake and binding of VMAT-2 and altered VMAT-2 cellular distribution |

| Schiffer et al (94) | • MPH elevated extracellular DA in the striatum but to a lesser degree than AMP; reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding were similar with MPH and AMP |

| Somkuwar et al (126) | • MPH administered during the adolescent period in rats produced strain-dependent alterations in cortical DAT activity at adulthood |

| Volkow et al (127) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding potential but not binding affinity in baboons, as measured by PET |

| Wall et al (128) | • MPH caused little or no change in DA, NE, or 5-HT efflux, although it blocked uptake mediated by both NET and DAT in transfected cell lines |

| Human neuroimaging studies | |

| Amphetamine | |

| Aalto et al (129) | • AMP did not alter [11C]FLB 457 (a D2/D3 receptor ligand) binding in the cortex of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Boileau et al (130) | • AMP decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in ventral striatum and putamen of healthy adults in response to conditioned stimuli, as measured by PET |

| Buckholtz et al (131) | • AMP-induced reductions in [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults were associated with increased trait impulsivity |

| Cardenas et al (132) | • AMP produced decreases in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding that were sustained for up to 6 hours in healthy adults, as measured using PET studies |

| Colasanti et al (133) | • AMP reduced [11C]carfentanil (a μ-opioid receptor antagonist) binding in the caudate, putamen, frontal cortex, thalamus, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex of healthy adult males, as measured by PET |

| Cropley et al (134) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the substantia nigra, medial prefrontal and orbital cortices, and caudate of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Devous et al (135) | • AMP increased regional CBF to the prefrontal cortex, inferior orbital frontal cortex, ventral tegmentum, amygdala, and anterior thalamus, and decreased regional CBF to the motor and visual cortices, fusiform gyrus, and regions of the temporal lobe of healthy adults, as measured by SPECT |

| Drevets et al (136) | • AMP-induced reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the anteroventral striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, were negatively correlated with feelings of euphoria |

| Garrett et al (137) | • AMP increased fMRI-based BOLD signal variability in healthy adults, with the effects being more pronounced in older adults (60–70 years old) than younger adults (20–30 years old) |

| Guterstam et al (138) | • AMP had no effect on [11C]carfentanil (a μ-opioid receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum, cortex, amygdala, or hippocampus of healthy adult males, as measured by PET |

| Hariri et al (139) | • AMP potentiated responses of the right amygdala to angry and fearful facial expressions of healthy adults, as measured by fMRI, without producing changes in performance of an emotional recognition task or a sensorimotor control task |

| Kegeles et al (140) | • AMP decreased [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by SPECT |

| Knutson et al (141) | • AMP exerted an equalizing influence on activity in the ventral striatum by enhancing tonic activity over phasic activity during anticipation of positive and negative incentives in healthy adults, as measured by fMRI |

| Laruelle et al (142) | • AMP decreased [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by SPECT |

| Laruelle and Innis (143) | • AMP decreased [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by SPECT |

| Leyton et al (144) | • AMP-decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the ventral striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, was correlated with increases in drug wanting and novelty seeking |

| Leyton et al (145) | • AMP-induced decreases in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the ventral striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, were attenuated by acute depletion of phenylalanine and tyrosine |

| Martinez et al (146) | • AMP decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in healthy adults, as measured by PET, with larger reductions observed in the limbic (ventral) and the sensorimotor (postcommissural) striatal regions than associative (caudate and precommissural) striatal regions |

| Mick et al (147) | • AMP reduced [11C]carfentanil (a μ-opioid receptor antagonist) binding in the caudate, putamen, frontal lobe, thalamus, nucleus accumbens, insula, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Narendran et al (148) | • AMP decreased [11C]FLB 457 (a D2/D3 receptor ligand) and [11C]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the medial temporal lobe, anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral and medial prefrontal cortices, and parietal cortex of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Narendran et al (149) | • AMP decreased [11C]NPA (a D2/D3 receptor agonist) and [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, with reductions of [11C]NPA binding being greater than those of [11C]raclopride |

| Oswald et al (150) | • AMP-induced reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, were correlated with increased cortisol release and positive subjective ratings of AMP |

| Oswald et al (151) | • AMP decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, with lower binding in the right dorsal caudate being associated with lower winnings in the Iowa Gambling Task |

| Riccardi et al (152) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in healthy adults, as measured by PET, with the reductions across brain regions differing as a function of gender |

| Riccardi et al (153) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum, substantia nigra, amygdala, temporal cortex, and thalamus of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Riccardi et al (154) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in healthy adults, as measured by PET, with the reductions in selected baring regions being correlated with Stroop test scores, Stroop test interference, and affective state |

| Rose et al (155) | • AMP increased CBF in the cerebellum, brainstem, temporal lobe, striatum, and prefrontal and parietal cortices of healthy adults, as measured by MRI |

| Schouw et al (156) | • AMP-induced increases in regional CBF in the striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum of healthy adults, as measured by MRI, were not correlated with reductions in [123I]IBZM receptor binding in the striatum, as measured by SPECT |

| Shotbolt et al (157) | • AMP induced reductions in [11C]–(+)-PHNO (a D2/D3 receptor agonist) binding in the ventral pallidum, ventral striatum, thalamus, and putamen of healthy adults, as measured by PET, which were greater than the reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding |

| Silverstone et al (158) | • AMP increased myo-inositol and phosphomonoester concentrations in the temporal lobe of healthy adults, as measured by MRS |

| Slifstein et al (159) | • AMP reduced [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum, globus pallidus, midbrain, hippocampus, and amygdala of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Vollenweider et al (160) | • AMP increased regional cerebral glucose metabolism in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex, caudate nucleus, putamen, and thalamus of healthy adults, as measured by PET with [18F]-FDG |

| Wand et al (161) | • AMP-induced reductions in [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in striatum of healthy adults, as measured PET, were associated with stress-induced cortisol levels |

| Willeit et al (162) | • AMP reduced [11C]–(+)-PHNO (a D2/D3 receptor agonist) binding in the striatum but not in the globus pallidus of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Wolkin et al (163) | • AMP decreased regional cerebral glucose metabolism in the frontal cortex, temporal cortex, and striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Woodward et al (164) | • AMP-induced reductions in [18F]fallypride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, were positively correlated with overall schizotypal traits |

| Methylphenidate | |

| Booij et al (165) | • MPH reduced [123I]IBZM (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by SPECT |

| Clatworthy et al (166) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the putamen, ventral striatum, and postcommissural caudate of healthy adults, as measured by PET, with reductions in the postcommissural caudate being negatively correlated with reversal learning performance |

| Costa et al (167) | • MPH increased neuronal activation in the putamen of healthy adults as measured by fMRI, during a go/no-go task when a response inhibition error occurred but not when a response was successfully inhibited |

| Ding et al (112) | • MPH reduced binding of [11C]d-threo-MPH to a greater degree than [11C]l-threo-MPH in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Hannestad et al (168) | • MPH dose-dependently reduced [11C]MRB (a NET ligand) binding across the brain (eg, locus coeruleus, raphe nucleus, hypothalamus, thalamus) of healthy adults, as measured using PET |

| Kasparbauer et al (169) | • MPH increased BOLD signal during successful go/no-go trials in healthy adult carriers of the SLC6A3 9R allele of the DAT gene but a decrease in 10/10 allele homozygotes, as measured by fMRI |

| Montgomery et al (170) | • MPH reduced [11C]FLB 457 (a D2/D3 receptor ligand) binding in the frontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, temporal cortex, and thalamus of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Moeller et al (171) | • MPH improved Stroop color-word task performance and concurrently reduced dorsal anterior cingulate cortex responses of healthy adults, as measured by fMRI |

| Mueller et al (172) | • MPH increased connectivity strength between the dorsal attention network and thalamus, with the left and right frontoparietal networks and the executive control networks also showing increased connectivity to sensory-motor and visual cortex regions, and decreased connectivity to cortical and subcortical components of cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits in healthy adults, as measured by fMRI |

| Ramaekers et al (173) | • MPH reduced functional connectivity between the nucleus accumbens and the basal ganglia, medial prefrontal cortex, and temporal cortex without changing functional connectivity between the medial dorsal nucleus and the limbic circuit, as measured by fMRI |

| Ramasubbu et al (174) | • MPH decreased oxy-hemoglobin levels, an index of decreased neural activation, in the right lateral prefrontal cortex of healthy adults, as measured by fNIRS |

| Schabram et al (175) | • MPH decreased DA turnover in the caudate and putamen of healthy adult females, as measured by PET using [18F]FDOPA |

| Schweitzer et al (176) | • MPH improved Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test performance, reduced regional CBF in the prefrontal cortex, and increased regional CBF in the right thalamus and precentral gyrus of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Schlosser et al (177) | • Processing of uncertain information was associated with higher activation of the parietal association cortex and posterior cingulate cortex after placebo relative to MPH, but with higher left and right parahippocampal and cerebellar activation after MPH relative to placebo, as measured by fMRI |

| Spencer et al (178) | • Both short-acting and long-acting MPH formulations decreased [11C]altropane (a DAT ligand) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Spencer et al (179) | • Plasma MPH concentrations were correlated with [11C]altropane (a DAT ligand) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Tomasi et al (180) | • MPH increased the activation of the parietal and prefrontal cortices and increased the deactivation of the insula and posterior cingulate cortex in healthy adults, as measured by fMRI during visual attention and working memory tasks |

| Udo de Haes et al (181) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in healthy adults, as measured by PET, with binding changes in the dorsal striatum correlating with MPH-induced increases in euphoria |

| Volkow et al (182) | • MPH decreased [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Volkow et al (183) | • MPH decreased [11C]d-threo-MPH binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Volkow et al (184) | • MPH produced variable changes in brain metabolism in healthy adults, as measured by PET using [18F]FDG, but produced consistent increases in cerebellar metabolism and decreases in the basal ganglia |

| Volkow et al (185) | • MPH dose-dependently reduced [11C]cocaine (a DAT ligand) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, with effects observed at therapeutic doses used for ADHD |

| Volkow et al (186) | • MPH dose-dependently reduced [11C]cocaine (a DAT ligand) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, with self-reports of MPH-induced “high” and “rush” being significantly correlated with [11C]cocaine binding |

| Volkow et al (187) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Volkow et al (188) | • MPH reduced [11C]cocaine (a DAT ligand) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET |

| Volkow et al (189) | • A review of PET studies suggested that mechanism of action of MPH was related to binding of MPH to the DAT levels sufficient to increase signal-to-noise ratios and to increase the salience of stimuli, with variability in MPH response being related to differences in DAT level and DA release across individuals |

| Volkow et al (190) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults in a context-dependent manner, as measured by PET, with reductions observed when a remunerated mathematical task was performed but not when scenery cards were passively viewed |

| Wang et al (191) | • MPH reduced [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) binding in the striatum of healthy adults, as measured by PET, with changes being reproducible in individuals at 1- to 2-week intervals |

5-HT=5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin); ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AMP=amphetamine; BOLD=blood-oxygen-level dependent; cAMP=cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CBF=cerebral blood flow; CHPG=2-chloro-5-hydroxyphenylglycine; CREB=cAMP-responsive element binding protein; DA=dopamine; DAT=dopamine transporter; FDG=2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose; FDOPA=fluorodopamine; fMRI=functional magnetic resonance imaging; fNIRS=functional near infrared spectroscopy; FP-CIT=N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-nortropane; GABA=gamma-aminobutyric acid; GLU=glutamate; IBF=iodobenzofuran; IBZM=iodobenzamide; MAO=monoamine oxidase; mGluR=metabotropic glutamate receptor; MNPA=(R)-2-CH3O-N-n-propylnorapomorphine; MPEP=2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride; MPH=methylphenidate; MRB=methylreboxetine; MRI=magnetic resonance imaging; mRNA=messenger ribonucleic acid; MRS=magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NE=norepinephrine; NET=norepinephrine transporter; NMDA=N-methyl-D-aspartate; NPA=2-methoxy-N-propylnorapomorphine; PET=positron emission tomography; PHCCC=N-phenyl-7-(hydroxyimino)cyclopropa[b]chromen-1a-carboxamide; PHNO=(+)-4-propyl-3,4,4a,5,6,10b-hexahydro-2H-naphtho[1,2-b][1,4]oxazin-9-ol; PKC=protein kinase C; RGS4=regulator of G-protein signaling 4; SERT=serotonin transporter; SPECT=single-photon emission computed tomography; TRODAT=([2-[2-[3-(4-chlorophenyl)-8-methyl-8-azabicyclo[3,2,1]oct-2-yl]methyl](2-mercaptoethyl)amino]ethyl-amino-ethan-etio-lato-(3-)-oxo-[1R-(exo-exo)]; VMAT-2=vesicular monoamine transporter

3.1. Preclinical Studies

3.1.1. Amphetamine

The main mechanism of action of AMP is to increase synaptic extracellular DA and NE levels (44, 52, 59, 60, 67, 68, 71, 78, 80, 85, 87, 94, 105, 107, 128). This effect is mediated by inhibition of DA transporters (DAT) and NE transporters (NET) (44, 52, 58), which reduces the reuptake of these molecules from the synapse. In wild-type mice, AMP initially increases surface trafficking of DAT and DA uptake, but continued AMP exposure results in decreased surface expression of the DAT and decreases in DA uptake (49). In a dose-dependent and region-specific manner, AMP also increases vesicular DA release via inhibition of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT-2), which releases DA from vesicular storage, and the concomitant release of cytosolic DA via reverse transport by the DAT (58, 88, 99). Furthermore, AMP inhibits monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity (79, 90), which decreases cytosolic monoamine breakdown. A wide array of studies using positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have demonstrated that AMP produced reductions in the binding potential of ligands for DA receptors (42, 46, 47, 51, 53, 55, 61, 62, 65, 74-76, 80, 82, 91, 94, 95, 101-104) and NE receptors (59, 73), which is an indirect indicator of increased competition for binding sites resulting from increased extracellular DA or NE. The striatum, which contains most of the DATs in the brain (192, 193), appears to be a principal site of action of AMP (44, 194), but direct effects in the cortex and the ventral tegmental area have also been reported (85, 87, 195). The effects of AMP extend to and are modulated by other neurotransmitter systems (50, 56, 66, 70, 77, 85, 86, 89, 96, 98, 106, 108), including ACH, 5-HT, opioid, and GLU, either directly through enhanced release from presynaptic terminals or via downstream effects.

In other studies, AMP has been shown to produce changes at a more global level. In studies of cerebral blood flow (CBF), AMP increased whole brain CBF in rats and baboons (48, 69, 84, 92), with changes in CBF being correlated with striatal DA concentration (69). In a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study in rats, AMP caused widespread increases in blood-oxygen-level–dependent (BOLD) signal intensity in subcortical structures with rich DA innervation and with decreases in BOLD signal in the superficial layers of the cortex (54). In another fMRI study in rats, AMP reduced BOLD signal intensity in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex and increased signal intensity in the motor cortex of rats, with signal intensity changes in the nucleus accumbens and caudate (but not in the motor cortex) being attenuated by pretreatment with a tyrosine-free amino acid mixture (83).

3.1.2. Methylphenidate

The direct effects of MPH include inhibition of the DAT and NET (113, 114, 118, 120, 123, 128), an affinity for and agonist activity at the 5-HT1A receptor (119, 120), and redistribution of VMAT-2 (88, 125). As a consequence of these interactions, MPH elevates extracellular DA and NE levels (58, 71, 94, 107). The enhanced efflux of DA and NE associated with MPH exposure results in increased availability of DA and NE to bind to their respective transporters (ie, the DAT or NET) or to DA or NE receptors, as evidenced by reductions in ligand binding in PET and SPECT studies (112, 113, 117, 122-124, 127).

Although increases in extracellular levels of striatal DA in rats measured using microdialysis are less pronounced with MPH than with AMP, both compounds have been shown to exhibit similar magnitude of effects with regard to reductions in DA binding potential as measured by PET in rodents and nonhuman primates (94). Multiple studies have demonstrated that MPH also directly interacts with adrenergic receptors (109, 115, 119, 120). Through activation of α2 adrenergic receptors, MPH has been demonstrated to stimulate cortical excitability (109). Further evidence for the interaction of MPH with α2 adrenergic receptors comes from data indicating that the procognitive effects of MPH in a working memory task are blocked by the α2 adrenergic antagonist idazoxan (115). The effects of MPH on α2 adrenergic receptors are notable given that two α2 adrenergic receptor agonist drugs (extended-release forms of guanfacine and clonidine) are indicated for the treatment of ADHD (196).

3.2. Human Neuroimaging Studies

3.2.1. Amphetamine

Reductions in ligand binding in PET (130-132, 134, 136, 144-146, 148-154, 157, 159, 161, 162, 164) and SPECT (140, 142, 143, 156) studies in healthy humans indicate that AMP increases DA release across multiple brain regions, including the dorsal and ventral striatum, substantia nigra, and regions of the cortex. AMP also has been shown to alter regional CBF to areas of the brain with DA innervation, including the striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, prefrontal and parietal cortex, inferior orbital cortex, thalamus, cerebellum, and amygdala (135, 155, 156, 160, 163). The effects of AMP on regional CBF appear to be dependent on the dose, with lower doses decreasing rates of blood flow in the frontal and temporal cortices and in the striatum (163) and higher doses increasing blood flow in the anterior cingulate cortex, caudate nucleus, putamen, and thalamus (160). In fMRI studies in healthy adults, AMP increased BOLD signal variability (137) and exerted an “equalizing” effect on ventral striatum activity during incentive processing (141). In addition, AMP was shown to strengthen amygdalar responses during the processing of angry and fearful facial expressions (139).

Changes in neuronal activity have been shown to correlate with various behavioral traits (131, 136, 144, 164). In PET studies, changes in the binding potential of [11C]raclopride (a D2 receptor antagonist) in regions of the ventral striatum of healthy adults associated with AMP binding have been reported to be negatively correlated with changes in AMP-associated euphoria (136) and with increases in drug wanting and novelty seeking (144).

3.2.2. Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate has also been shown to increase striatal DA availability, as measured by reductions in ligand binding potential in PET studies (165, 166, 170, 178, 179, 181, 182, 187, 190, 191), with evidence to indicate that this effect is related to binding to the DAT (185, 186, 188). MPH-induced reductions in striatal [11C]raclopride binding were associated with MPH-induced changes in euphoria and anxiety and were correlated to age (181, 182). In addition, NE systems have been implicated as key targets for MPH, with MPH dose-dependently blocking the NET in the thalamus and other NET-rich regions; the estimated occupancy of the NET at therapeutic doses of 0.35 to 0.55 mg/kg MPH is 70% to 80% (168).

Assessments of functional activity using fMRI have provided evidence for the widespread functional effects of MPH (167, 171-173, 177, 180). Using fMRI, it has been shown that MPH increases activation of the parietal and prefrontal cortices and increases deactivation of the insula and posterior cingulate cortex during visual attention and working memory tasks (180). Another fMRI study reported MPH-induced activation in the putamen during a go/no-go task when a response inhibition error occurred but not when a response was successfully inhibited (167), suggesting that the effects of MPH are context dependent. Furthermore, MPH exposure altered connectivity strength across various cortical and subcortical networks (172) and shifted brain activation under conditions of uncertainty to higher levels of activation in left and right parahippocampal regions and cerebellar regions (177). Lastly, MPH-associated decreases in task-related errors on the Stroop color-word task were associated with concurrent decreases in anterior cingulate cortex activity (171). MPH has also been shown to reduce regional CBF in the prefrontal cortex and increase regional CBF in the thalamus and precentral gyrus (176). In another study that used functional near-infrared spectroscopy, MPH-associated improvements in the performance of a working memory task corresponded with decreased oxy-hemoglobin levels in the right lateral prefrontal cortex, which is a surrogate for decreased neural activation (174).

4.0. Discussion

Although their mechanisms of action differ, the primary central nervous system effects of AMP and MPH within the brain include increased catecholamine availability in striatal and cortical regions, as evidenced in preclinical (44, 52, 58-60, 67, 68, 71, 78, 80, 85, 87, 94, 105, 107, 128) and human (130-132, 134, 136, 140, 142-146, 148-154, 156, 157, 159, 161, 162, 164-166, 170, 178, 179, 181, 182, 187, 190, 191) studies. These increases in DA and NE availability affect corticostriatal systems that subserve behaviors related to cognition and executive function (171, 177, 180), risky decision making (151), emotional responsivity (139), and the regulation of reward processes (197). Importantly, ADHD has been associated with structural and functional alterations in regions of the brain where AMP and MPH have been shown to alter DA and NE activity.

4.1. Structural Alterations in ADHD

A meta-analysis of imaging data from individuals with ADHD across all age groups revealed altered white matter integrity in diverse brain areas, including the striatum and the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes (198). In a meta-analysis of imaging data from children and adults (199), global gray matter volume was significantly smaller in those with ADHD, especially in basal ganglia structures integral to executive function. In adults with ADHD, reduced gray matter volume in the caudate and parts of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobe, anterior cingulate cortex, putamen, and cerebellum were observed; increased volume was noted in other parts of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and inferior parietal lobe (200). A meta-analysis of 1713 persons with ADHD and 1529 controls found volumetric reductions in the accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, and putamen (201).

In a meta-analysis of 9 PET and SPECT studies, which included 169 patients with ADHD and 173 healthy controls, it was reported that striatal DAT density in patients with ADHD was 14% higher than in healthy controls (202). Meta-regression analysis further revealed that previous exposure to ADHD medication influenced striatal DAT density, with lower DAT density being associated with a lack of medication exposure (202). As the correlation between medication exposure and striatal DAT density accounted for 48% of the variance across studies (202), it was suggested that the higher striatal DAT density in individuals with ADHD was a neuroadaptive response to stimulant exposure.

4.2. Functional Alterations in ADHD

A meta-analysis of imaging data focusing specifically on timing function, which is important for impulsiveness in ADHD, showed consistent deficits in the left inferior prefrontal, parietal, and cerebellar regions of individuals with ADHD (203). A meta-analysis of 24 task-related fMRI studies coupled with functional decoding based on the BrainMap database reported hypoactivation in the left putamen, inferior frontal gyrus, temporal pole, and right caudate of individuals with ADHD (204). When examining these deficits in regard to the BrainMap database, it was suggested that individuals with ADHD may exhibit deficits in the cognitive aspects of music, perception and audition, speech and language, and executive function (204).

In high-functioning, drug-naive young adults with ADHD, resting-state fMRIs revealed altered connectivity in the orbitofrontal-temporal-occipital and frontal-amygdala-occipital networks (relating to inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms, respectively) compared with matched controls; these abnormalities were not related to developmental delays, impaired cognition, or use of pharmacotherapy (205). Imaging studies have also reported hypoactivity in the prefrontal cortex and weak connections to other brain regions in individuals with ADHD (206). A review of progress in neuroimaging indicated that the initial focus on frontostriatal dysfunction has given way to a broader understanding of the complex interactions of various regions of the brain in which alterations may contribute to ADHD symptoms across the life span (207).

A substantial body of literature has examined the role of DA systems in the neurobiology of ADHD and ADHD-related symptoms and behaviors. Among treatment-naive adolescents with ADHD, DAT density shows a significant inverse relationship with blood flow in the cingulate cortex, the frontal and temporal lobes, and the cerebellum, brain regions which are involved in modulating attention (208). In a PET study of treatment-naive men with ADHD and men without ADHD, more pronounced reductions in AMP-induced reductions in striatal [11C]raclopride binding were associated with worse response inhibition, and those with ADHD had the highest-magnitude reductions and AMP-induced reductions in striatal [11C]raclopride binding (209). Two SPECT studies and 1 PET study showed that adults with ADHD had higher DAT concentrations than adults without ADHD (210-212), with the SPECT studies further reporting that MPH reduced DAT availability in adults with ADHD (210, 211). Furthermore, studies have shown significant correlations between global clinical improvement in ADHD symptoms following MPH treatment and striatal DAT availability (213, 214), and the MPH-induced increases in DA availability in the ventral striatum are associated with improved ADHD symptomology in adults with ADHD (215). In another study, in adults with ADHD, long-term MPH treatment increased striatal DAT availability (216). In another PET study in adults with ADHD, decreased DAT and D2/D3 receptor availability in the nucleus accumbens and midbrain compared with individuals without ADHD was reported, and reduced availability of DAT and D2/D3 receptor availability was significantly correlated with lower indices of motivation only in those with ADHD (217). Also, a PET study in young male adults with ADHD has also reported dysfunctional DA metabolism in the putamen, amygdala, and dorsal midbrain relative to healthy controls regardless of treatment status (naive vs previously treated with MPH) and that a history of MPH treatment resulted in a down-regulation of DA turnover (218). Despite the neuroimaging evidence that supports a role for the DAT in adult ADHD, a systematic literature review examining the pharmacogenetics of adult ADHD found that only 1 of 5 identified studies reported finding a polymorphism at the DAT gene associated with ADHD (219).

Studies of NET availability have not consistently reported altered NET availability in individuals with ADHD (220, 221), but one study reported genotype-dependent increases in NET binding in the thalamus and cerebellum of adults with ADHD compared with controls; this effect was largely due to the effect of NET gene polymorphisms on NET binding potential (220). Another study reported no NET differences across multiple brain regions, including the hippocampus, thalamus, and midbrain, in individuals with ADHD compared with controls (221).

Beyond the changes observed in DA and NE systems in individuals with ADHD, there is evidence that GLU, 5-HT, ACH, and opioid systems play a role in ADHD. Studies examining neurometabolism using proton MRIs have reported glutamatergic deficits in the frontal cortical and striatal regions in individuals with ADHD that may be related to cognitive control and symptom severity (12, 222, 223). Regarding the 5-HT systems, it has been reported that increased methylation of the 5-HT transporter is associated with worse clinical presentation and reduced cortical thickness in children with ADHD (224). In adults, significant differences in 5-HT transporter interregional correlations between the precuneus and hippocampus have been reported in adults with ADHD compared with controls without ADHD (225). Functionally, it has been reported that decreased levels of activation are observed in the precuneus of adolescents with ADHD compared with individuals without ADHD; however, there is a significantly greater increase in the activation of the precuneus following the administration of fluoxetine in adolescents with ADHD compared with controls (226). At present, there are no published neuroimaging studies of endogenous opioid or ACH systems in individuals with ADHD. However, altered function in both systems has been implicated in ADHD (13, 14).

4.3. Co-occurring Psychiatric Conditions and ADHD

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is often associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders (16-18), such as anxiety and mood disorders. Importantly, the same brain regions and neurotransmitter systems that underlie ADHD are also implicated in the psychiatric disorders that are frequently comorbid with ADHD (19-21). Thus, it is important to understand how ADHD therapies might influence psychiatric comorbidities.

4.3.1. Anxiety disorders

In healthy human volunteers, AMP has been reported to potentiate amygdalar activity in response to the processing of angry and fearful facial expressions (139). These data provide a potential neurobiologic basis for the anxiogenic effects of AMP (139). However, it has been theorized that stimulant-associated augmentation of serotonergic drive could ameliorate the comorbid anxiety associated with ADHD (227). In practice, the effects of stimulants on anxiety can be complex, with acute administration of MPH reducing anxiety in adults and chronic treatment during early life increasing anxiety during adulthood (228).

4.3.2. Depressive disorders

Psychostimulants have been used in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) since the early 1950s, when the use of MPH was first examined for MDD (229). The rationale for examining the potential utility of psychostimulants in depressive disorders is based on preclinical and clinical evidence implicating DA in depressive symptomatology (230). However, the rapid onset of action of psychostimulants suggests the mechanisms by which they may influence depressive symptoms is likely to differ from that of antidepressants (231).

Based on the published literature, the effects of psychostimulants on depressive symptoms appear equivocal. Although one meta-analysis published in 2008 based on 3 short-term trials reported statistically significant improvements favoring monotherapy with psychostimulants compared with placebo for depressive symptoms (232), a systematic review of augmentation therapy for MDD published in 2009 based on MPH (2 studies) and modafinil (2 studies) reported that neither augmentation strategy was clinically superior to antidepressant monotherapy in reducing depressive symptoms (233). In addition, 2 large phase 3 studies and a phase 2 study of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate augmentation in adults with MDD and inadequate response to antidepressant therapy failed to meet their primary efficacy endpoint versus placebo (234, 235). The lack of treatment effect in these recently published studies, taken together with inconsistent findings based on meta-analyses and systematic reviews, suggests that psychostimulants are ineffective in treating the undifferentiated symptoms of depression. Psychostimulants have also been examined in other mood disorders, including treatment-resistant depression, bipolar depression, and depression associated with specific medical conditions (236). For bipolar depression, there is some evidence supporting the efficacy of psychostimulant augmentation, but the quality and quantity of studies does not allow for a strong evidence-based recommendation for their use to be put forth (236).

Despite inconclusive evidence regarding the efficacy of psychostimulants in treating depressive symptoms, the continued publication of review articles on this topic (231, 237, 238) demonstrates continued interest in this area of research. These review articles hypothesize that the lack of consistent clinical efficacy of psychostimulant augmentation could be due to poorly defined psychopathology and that psychostimulant effects may be more pronounced in selected symptom domains (237, 238) or that the effects of psychostimulants are short-lasting (231). It has also been speculated that the use of clinician-rated scales (rather than patient-rated scales) in some studies (234, 235) may not have adequately captured the effects of psychostimulant treatment.

It should also be noted that the use of stimulants as augmentation agents in combination with tricyclic antidepressants and MAO inhibitors is controversial, with issues concerning the possible development of an adrenergic crisis, the emergence of serotonin syndrome, or a hypertensive crisis being raised (239). In fact, both MPH-based agents and AMP-based agents are contraindicated in individuals taking an MAO inhibitor (currently or within the preceding 2 weeks) because a hypertensive crisis may result (240).

4.3.3. Substance use disorders

The neurobiology of reward and addiction and the key role of mesolimbic DA systems have been described in great detail (241, 242). Although associations have been made between ADHD and substance abuse, their relationship is complex. Several reviews have emphasized that substance use disorders can be comorbid with ADHD (16, 17). For example, in a study of 208 adults diagnosed with ADHD and treated with psychostimulants as youths, the relative risk of having a diagnosis of substance use disorder or alcohol abuse, respectively, compared with the general population was 7.7 or 5.2 (243). Furthermore, a 2012 review noted that there was evidence for increased rates of substance abuse in individuals with ADHD treated with psychostimulants (244). Given the known abuse liability of psychostimulants and data indicating that psychostimulant medications are associated with misuse and diversion (245, 246), it is not surprising that psychostimulant medications approved for use in ADHD are schedule II medications with black box warnings for potential drug dependence (247). Some treatment guidelines suggest that nonstimulant alternatives be considered as therapies for ADHD when issues related to abuse and dependence are a concern (25, 28, 248).

However, multiple studies have provided evidence that psychostimulant treatment in individuals with substance use disorders and ADHD is not associated with a significant worsening of substance abuse (249, 250). In a study that examined the efficacy of extended-release mixed AMP salts in the treatment of ADHD symptoms and cocaine abuse in 126 cocaine-dependent adults with ADHD (250), significantly greater reductions in ADHD symptoms and higher abstinence from cocaine use were observed with extended-release mixed AMP salts than placebo. In another study, osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) MPH did not produce significantly greater reductions in ADHD symptoms than placebo in 24 AMP-dependent adults with newly diagnosed ADHD. However, OROS MPH treatment also was not associated with evidence of increased AMP abuse, as measured by self-reported days of AMP use or craving for AMP, time to relapse, or cumulative abstinence duration (249).

4.3.4. Sleep disturbances

The neurobiologic substrates of sleep are diverse and distributed throughout the brain, with monoaminergic systems playing an important role in wakefulness (21). Substantial literature exists regarding the sleep disturbances associated with ADHD, which include insomnia, disordered sleep, difficulty falling asleep, sleep apnea, daytime somnolence, and increased nocturnal motor activity (see (18, 251-253) for reviews). Evidence suggests that impaired and/or disordered sleep is present in individuals not being treated with psychostimulants (18). For example, in a study of the effects of MPH on sleep in children with ADHD, parents reported that approximately 10% of study participants had sleep problems before starting their medication (254). However, in regard to the reported effects of psychostimulants on sleep in individuals with ADHD, there are some discrepancies. In a meta-analysis of 9 articles, the use of psychostimulant medication was associated with longer sleep latency, worse sleep efficiency, and shorter sleep duration (255). A review of the safety and tolerability of ADHD medications noted that insomnia was one of the most commonly reported adverse events associated with psychostimulant treatment (36). In contrast, some studies have shown that psychostimulants have no significant negative impact on sleep (254, 256, 257). A post hoc analysis of the effects of lisdexamfetamine or SHP465 mixed amphetamine salts in adults with ADHD demonstrated that the proportions of participants exhibiting a worsening of sleep during treatment, as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, did not differ from that of placebo (257). Discrepancies in the effects of stimulants on sleep in individuals with ADHD might be attributable to various factors, including sleep quality prior to treatment, the stimulant formulation, the length of treatment, and the method of sleep assessment (251, 254, 255). For example, in a study of MPH in children with ADHD, 23% of participants without preexisting sleep problems developed sleep problems while taking MPH, whereas 68.5% of those with preexisting sleep problems no longer experienced sleep problems after taking MPH (254).

4.4. Other Safety Concerns

In addition to considering the potential effect of AMP and MPH in individuals with other comorbid psychiatric disorders, the peripheral effects of AMP and MPH related to their pharmacology need to be considered, particularly in regard to their effects on cardiovascular function. Increased heart rate and blood pressure are among the most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events reported with psychostimulant treatment (36, 37); increases in pulse and blood pressure are also frequently reported (36, 37, 258). There is also a safety concern related to the potential for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including ischemic attacks, myocardial infarction, and stroke (259). In a self-controlled case series analysis, treatment with MPH was associated with an increased overall risk of arrhythmia and with an increased risk of myocardial infarction from 1 week to 2 months after treatment initiation in children and adolescents with ADHD (260). Another study reported that the risk for an emergency department visit for cardiac-related reasons among youths did not differ between those being treated with AMP versus MPH (261). However, these findings should be considered in light of data from 2 large studies that reported no significant increase in risk for cardiovascular events in current users of ADHD medications compared with nonusers (262, 263).

The neurotransmitter systems responsible for stimulant-associated adverse events and safety concerns are in large part related to stimulation of peripheral NE activity (36, 259). Based on these concerns, package inserts for stimulants include black box warnings regarding the potential for serious adverse cardiovascular events (247). Assessments of the risks and benefits of stimulant therapy for ADHD should be made on an individual basis, and individuals on psychostimulant treatment should be monitored.

Another issue of potential concern is the possible neuroinflammatory effects of psychostimulants. In rats, MPH administration has been reported to produce neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, as measured by the inflammatory markers tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 1β (264, 265). In a systematic review of 14 studies (266), no study assessed the relationship between psychostimulant treatment and neuroinflammation so the relevance of preclinical models of neuroinflammation to psychostimulant treatment in individuals with ADHD is unknown. The same review did find evidence suggesting a role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of ADHD (266), which is consistent with a meta-analysis finding elevated levels of oxidative stress in patients diagnosed with ADHD (267). Oxidative stress has also been implicated in the lower brain volumes seen in ADHD patients (268).

5.0. Conclusions

Based on the published literature, the primary pharmacologic effects of both AMP and MPH are related to increased central DA and NE activity in brain regions that include the cortex and striatum. These regions are involved in the regulation of executive and attentional function (11). In ADHD, dysfunction in the DA and NE systems, which are critical to proper cortical and striatal function, likely account for some of the pathophysiology of ADHD (10, 11, 206). Although it is a limitation of the review that the only database searched was PubMed, it is unlikely that important studies were not captured.

It has been speculated that the moderately greater efficacy of AMP-based agents compared with MPH-based agents in ADHD may be related to differences in their molecular actions (33), but to date there is no conclusive clinical evidence to support this speculation. Furthermore, there is no conclusive clinical evidence supporting a prospective choice for an AMP-based agent over as MPH-based agent (or vice versa) based on the mechanisms of action of these drug classes. As such, the current understanding of differences in the mechanisms of action of AMP and MPH has not led to clinical guidelines regarding their use in specific patient populations. Furthermore, it is possible that differences in the pharmacologic profile between AMP and MPH, in combination with the complexities associated with the etiology of ADHD (11), contribute to individual differences in treatment response to AMP-based agents or MPH-based agents in individuals with ADHD. Interactions among these factors might explain why some patients have a differential response to these drugs.

When contemplating pharmacotherapy for ADHD, in addition to taking into account the potential for adverse cardiovascular outcomes (259), the presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders should be considered. Multiple psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and anxiety (16, 17), are thought to be mediated in part by shared neurobiological pathways that are also implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD (19, 20). As such, the effect of psychostimulant treatment on the symptoms of these disorders and the potential interactions with medications used to treat these disorders need to be considered.

Highlights.

This review discusses amphetamine (AMP) and methylphenidate (MPH) pharmacology.

AMP and MPH increase corticostriatal catecholamine availability in different ways.

Catecholamine alterations occur in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Differential mechanisms of AMP and MPH may influence individual treatment response.

Considering stimulant effects is vital when treating ADHD with comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

Shire Development LLC (Lexington, MA) provided funding to Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC (CHC; West Chester, PA), an ICON plc company, for support in writing and editing this manuscript. Under the direction of the author, writing assistance was provided by Madhura Mehta, PhD, and Craig Slawecki, PhD, employees of CHC. Editorial assistance in the form of proofreading, copyediting, and fact checking was also provided by CHC. The author exercised full control over the content throughout the development and had final approval of the manuscript for submission.

Dr. Faraone is supported by the K. G. Jebsen Centre for Research on Neuropsychiatric Disorders, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research, technological development, and demonstration under grant agreement no 602805, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 667302, and NIMH grants 5R01MH101519 and U01 MH109536-01.

Footnotes

Disclosures

In the past year, Dr. Faraone received income, potential income, travel expenses, continuing education support, and/or research support from Otsuka, Lundbeck, Kenpharma, Rhodes, Arbor, Ironshore, Shire, Akili Interactive Labs, CogCubed, Alcobra, VAYA, Sunovion, Genomind, and NeuroLifeSciences. With his institution, he holds US patent US20130217707 A1 for the use of sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibitors in the treatment of ADHD.

References

- 1.Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, Biederman J, Greenhill L, Hynd GW, et al. DSM-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1673–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):279–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T. Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(2):211–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fayyad J, De Graaf R, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;190:402–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon V, Czobor P, Balint S, Meszaros A, Bitter I. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purper-Ouakil D, Ramoz N, Lepagnol-Bestel AM, Gorwood P, Simonneau M. Neurobiology of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Res. 2011;69(5 Pt 2):69R–76R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortese S The neurobiology and genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): what every clinician should know. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2012;16(5):422–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maltezos S, Horder J, Coghlan S, Skirrow C, O'Gorman R, Lavender TJ, et al. Glutamate/glutamine and neuronal integrity in adults with ADHD: a proton MRS study. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum K, Chen AL, Braverman ER, Comings DE, Chen TJ, Arcuri V, et al. Attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder and reward deficiency syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(5):893–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter AS, Schaubhut G, Shipman M. Targeting the nicotinic cholinergic system to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: rationale and progress to date. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(12):1103–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elia J, Glessner JT, Wang K, Takahashi N, Shtir CJ, Hadley D, et al. Genome-wide copy number variation study associates metabotropic glutamate receptor gene networks with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet. 2011;44(1):78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]