Abstract

There is increasing evidence that several mitochondrial abnormalities are present in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Decreased alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (αKGDHc) activity was identified in some patients with AD. The αKGDHc is a key enzyme in the Krebs cycle. This enzyme is very sensitive to the harmful effect of reactive oxygen species, which gives them a critical role in the Alzheimer and mitochondrial disease research area. Previously, several genetic risk factors were described in association with AD. Our aim was to analyze the associations of rare damaging variants in the genes encoding αKGDHc subunits and AD. The three genes (OGDH, DLST, DLD) encoding αKGDHc subunits were sequenced from different brain regions of 11 patients with histologically confirmed AD and the blood of further 35 AD patients. As a control group, we screened 134 persons with whole-exome sequencing. In all subunits, a one–one rare variant was identified with unknown significance based on American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) classification. Based on the literature research and our experience, R263H mutation in the DLD gene seems likely to be pathogenic. In the different cerebral areas, the αKGDHc mutational profile was the same, indicating the presence of germline variants. We hypothesize that the heterozygous missense R263H in the DLD gene may have a role in AD as a mild genetic risk factor.

Keywords: alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, αKGDHc, Alzheimer, dementia, DLD, rare variants, brain tissue

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most frequent primary dementia (60–80%), is a neurodegenerative disease associated with initial memory impairment and cognitive deterioration, which may affect later visuospatial orientation, behavior, and speech as well [1,2]. AD is usually a complex multifactorial disease, although monogenic forms are known, too. In the background of multifactorial AD, in addition to genetic risk factors, many pathophysiological dysfunctions are described such as oxidative stress, problems with the cell cycle, and neurovascular dysfunction [3].

A significant proportion of AD cases (90–95%) are sporadic and belong to the late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) group (>65 years). Several genetic risk factors have already been identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) in association with LOAD. The most significant of these is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) 4 allele. In addition, several genetic risk genes in LOAD, such as TREM2 and ADAM10, have been shown to not only directly affect tau and amyloid precursor protein (APP) but also modulate endocytosis, immune response, and cholesterol metabolism [1]. Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) is often of monogenic origin, and the symptoms of the patients are already present in the 40s (in extreme cases the 30s); about 10% of all AD patients belong here. While the LOAD, which has a complex, heterogeneous etiology has 70–80% inheritance, the EOAD, which is usually a genetically deterministic form, has 92–100% inheritance. However, only 5–10% of EOAD cases are explained by high-penetrant mutations in the three known EOAD genes: APP, presenilin 1 and 2 (PSEN1, PSEN2). However, the majority of AD cases are still unresolved, indicating the need to identify additional causal or risk genes. Understanding the role of various known and newly described risk genes has greatly contributed to the understanding of the pathomechanism of AD and shed light on the molecular pathways involved [4,5,6,7].

The accumulation of aggregated extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) made of abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau are the fundamental hallmarks of AD neuropathology [8]. The tau lesion is correlated with cognitive disturbances, suggesting a fundamental role of tau pathology in neurodegeneration of this disease [9].

There is an increasing evidence that several mitochondrial abnormalities are present also in the brain of patients with AD [10,11]. Impaired energy metabolism, disrupted mitochondrial bioenergetics, abnormal balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion, axonal trafficking, and mitochondrial distribution have been described in association with AD [12]. Furthermore, there are observations that are supporting the impaired mitochondrial biogenesis, endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondrial interaction, mitophagy, and mitochondrial proteostasis also in AD [12]. A recent publication associates the mitochondrial dysfunction with tau pathology in AD [13]. The axonal transport of different organelles and mitochondrial dynamics can be damaged by the overexpression of hyperphosphorylated and aggregated tau, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction [14].

Positron emission tomography with 2-(18F) fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG PET) investigations have been detected glucose hypometabolism in the early phase of AD in the brain [15]. This was interpreted as impaired energy metabolism through oxidative phosphorylation. The decreased glucose metabolism correlated with the reduced levels of blood thiamine diphosphate, which is a critical coenzyme of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc), as well as α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (αKGDHc) in the Krebs cycle and transketolase in the pentose phosphate pathway in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortical regions of the patients with AD [16]. In patients with primary mitochondrial disease, the FDG PET detected impaired cerebral glucose uptake in the temporal and occipital lobe [17]. Inczedy et al. reported in their case series that the systematic evaluation of patients with mtDNA mutations evidenced cognitive deficits quite similar to those commonly seen in AD [18].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of αKGDHc in the pathogenesis of AD. This enzyme is a key player in the Krebs cycle, and alpha-ketoglutarate catalyzes an irreversible reaction converting alpha-ketoglutarate, coenzyme A and NAD+ to succinyl-coenzyme A, NADH and CO2, using thiamine pyrophosphate as a cofactor. This enzyme is located in the mitochondrial matrix and uses thiamine pyrophosphate as a cofactor. The enzyme consists of three subunits encoded by the OGDH (E1 subunit: 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase), DLST (E2 subunit: dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase), and DLD (E3 subunit: dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: LADH) genes. Previous investigations into the cell-specific localization of subunits in the adult human brain cortex have also revealed that DLD was identified in both neurons and glia, while OGDH and DLST were detected only in neurons [19]. The impairment of LADH function affects numerous key metabolic routes, as it is a common E3 subunit to the alpha-ketoglutarate, alpha-ketoadipate, pyruvate, and branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. This is also due to the clinical severity of loss in LADH function [20]. Previous in vitro experiments have demonstrated that disease-causing variants show increased reactive oxygen species (ROS)-generating capacities as compared to wild-type enzyme [21]. Based on the first high-resolution structural study of the E3 subunit mutant, it is hypothesized, for example, that mutations in the dimeric interface are likely to modify the geometry and polarity of E3; thus, they may lead to enhanced ROS generation [22]. Other studies of E3 have also revealed that the variant with the most severe structural aberrations (P453L-E3) has the most serious clinical symptoms, while the variant with the least abnormity (G426E-E3, G194C-E3) has a mild clinical manifestation [23].

In this study, we focused on αKGDHc, which is a key enzyme in the Krebs cycle that is very sensitive to the harmful effect of ROS, which gives them a critical role in Alzheimer’s and mitochondrial disease research areas. It has previously been demonstrated that αKGDHc activity decreases in AD [24,25]. In the brain, it behaves differently compared to other tissues—it is implicated in glutamate degradation, having an important role in neurotoxicity [26]. The enzyme activity is also different in each brain region, the highest of which is in the cortex [27]. Cholinergic neurons are rich in αKGDHc complexes, and they are extremely sensitive to αKGDHc defects [26]. Some research suggests a correlation between lower αKGDHc activity and more severe dementia (CDR value: clinical dementia rating) [28].

E3-deficiency, inherited in autosomal recessive form, is a severe infantile lethal disease. The E3 defect affects mostly tissues with high oxygen expenditure, resulting in neurological and cardiological symptoms. Typical symptoms are hypotonia, developmental delay, encephalopathy, recurrent metabolic crises, and lactic acidosis. The symptoms usually appear at a young age with lactate acidosis and hypotonia. The affected children usually die under 4–10 years of age due to their first or recurrent metabolic decompensation [29,30,31].

Alpha-KGDH defects have been observed in neurodegenerative diseases as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and SCA1 [32]. We suppose that the heterozygous mutations of αKGDHc’s subunits could be genetic risk factors or triggers of AD.

Waqar et al. investigated the association between AD and DLD through tau-mediated toxicity in a C. elegans model of AD. Based on their results, DLD suppression leads to significant tau phosphorylation, thereby influencing the pathology of AD [33].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

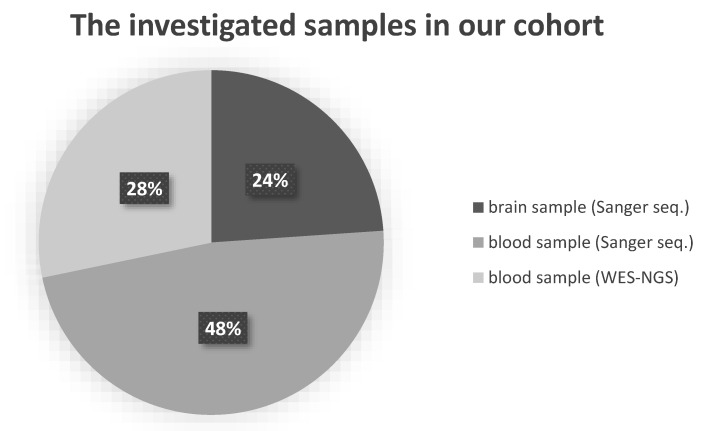

For 46 patients diagnosed with AD, all three subunits of αKGDHc were genetically analyzed. In 11 patients diagnosed with AD, post-mortem brain tissue was examined (5 male, 69.5 ± 9 years; 6 female, 77 ± 8 years). Brain samples were selected from the Human Brain Tissue Bank of Semmelweis University (HBTB); in all cases, detailed neuropathological investigation certified the Alzheimer’s diagnosis. HBTB has been authorized by the Committee of Science and Research Ethics of the Hungarian Ministry of Health (No. 6008/8/2002/ETT) and the Semmelweis University Regional Committee of Science and Research Ethics (No. 32/1992/TUKEB). For autopsy, brains were removed from the skull with a post-mortem delay of 2–6 h. Several regions (frontal, temporal Brodman 20–21, prefrontal Brodman 9, parietal, and parahippocampal lobes) of brain tissues were analyzed per sample to detect rare damaging variants and to observe possible somatic mutations. Further AD patients were selected from our NEPSYBANK [34]. These patients were diagnosed with AD by a board-certified neurologist. On blood samples of 13 AD patients (2 male, 72 ± 13 years; 11 female, 62 ± 8 years), whole-exome sequencing with next-generation sequencing (WES-NGS) was performed, and 22 AD patients (6 male, 63 ± 4.6 years; 16 female, 55.8 ± 10 years) were analyzed with bidirectional Sanger sequencing. The distribution of the analyzed samples between the different sample types and sequencing methodologies is shown in Figure 1. As a control group, we investigated brain tissues from patients without any sign of neurodegenerative disorders from the HBTB. This healthy control group consisted of 9 post-mortem brain tissues (3 male, 73 ± 5 years; 6 female, 54 ± 14 years) in which histopathological examinations did not detect any alterations indicating neurodegeneration. The 134 control individuals (72 male; 62 female) could be divided into two groups: 55 were healthy, in 79 cases, no neurological disorders were detected. They were investigated by WES-NGS.

Figure 1.

The distribution of the different analyzed samples by sample type. Abbreviations: WES-NGS: whole-exome sequencing with next-generation sequencing.

2.2. Genetic Investigations

All DNA from frozen brain samples in our study was isolated with a QIAamp DNA tissue kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). DNA from blood samples were isolated with a QIAamp DNA blood kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAgen, Hilden, Germany). We analyzed the third subunit of αKGDHc with bidirectional Sanger sequencing using an ABI Prism 3500 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at 22 AD patients. The sequences were compared with the human reference genome using NCBI’s Blast® application (OGDH: (GRCh37/hg19, ENST00000222673.5, NM_002541.4, DLST: GRCh37/hg19, ENST00000334220.4, NM_001933.5, DLD: GRCh37/hg19, ENST00000205402.5, NM_000108.5). DNA library preparation for WES was performed by a SureSelect QXT library preparation kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After library preparation, next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). First, cluster generation was performed on the cBot using HiSeq PE (Paired-End) Cluster Kit v4, then for sequencing HiSeq SBS Kit Reagent v4 was used.

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

After qualitative filtering of the raw data, the sequences were aligned with the GRCh37/hg19 reference genome using the BWA-MEM (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner; version 0.7.15) default parameters [35]. Variant calling from the NGS data was carried out with GATK HaplotypeCaller (Genome Analysis Toolkit, version 3.3-0) following the GATK Best Practices Guidelines [36]. Variant Call Format (VCF) files were annotated with different types of annotations by VariantAnalyzer software developed by the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. The annotations of SNPs and short INDELs were performed using for example SnpEff [37], which predicted their effect on genes and using ClinVar for disease associations [38]. Filtration for potentially damaging variants was performed VariantAnalyzer software. Variants with minor allele frequencies (MAFs) not exceeding 5% and less than 5% in our in-house exome database were also considered. The MAF was determined based on data of the 1000 Genomes Project (1 KG), the Genome Aggregation Database (GnomAD v2.1). During the next step of the analysis, rare alterations were filtered for known disease-causing alterations and then for non-synonymous variants. Variants selected based on these criteria were analyzed in our control group and reserved for further analysis. Interpretation of the novel variants were prepared according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guideline [39,40]. Variants were classified using the Varsome and Franklin websites [41,42].

3. Results

Analyzing the subunits of the enzyme for 46 patients with AD, we found three probably damaging missense mutations—in all subunits, one missense mutation was present. In this AD group, OGDH harbored eight synonymous rare variants (E115E; S132S; L228L; H425H; T434T; S603S; T996T; N1021N), two benign or likely benign rare missense variants (S55L; V1018I), and one rare variant with unknown significance (P471H). In the DLST gene, only one variant with unknown significance was detected (P204L). Only one rare missense substitution was detected in the DLD. All alterations found in our AD cohort are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The detected variants in the investigated cohort.

| Gene | Variant ID | Variant Effect | Clinical Significance |

ACMG Classification |

MAF (GnomAD, Non-Finnish) |

Patients | Controls | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGDH | c.164 C > T p. S55L |

missense | B | Likely Benign | 1.07% | 2/46 | 4/134 | - |

| c.345 A > G E115E |

synonymous | B | Benign | 2.47% | 1/46 | 18/134 | - | |

| c.396 G > A S132S |

synonymous | B | Benign | 4.88% | 1/46 | 5/134 | - | |

| c.682 C > T L228L |

synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 2/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1275 C > T H425H |

synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1302 T > A T434T |

synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1412 C > A P471H |

missense | B | Uncertain Significance | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.1809 C > A S603S |

synonymous | B | Likely Benign | - | 1/46 | 0/134 | - | |

| c.2988 C > T T996T |

synonymous | B | Benign | 5.04% | 1/46 | 10/134 | - | |

| c.3052 G > A V1018I |

missense | B | Benign | 5.05% | 2/46 | 12/134 | - | |

| c.3063 C > T N1021N |

synonymous | B | Benign | 5.05% | 1/46 | 10/134 | - | |

| DLST | c.611 C > T P204L |

missense | B | Uncertain Significance | 2.27% | 1/46 | 4/134 | - |

| DLD | c.788 G > A R263H |

missense | D | Uncertain Significance | ≤0.01 | 1/46 | 0/134 | [30] |

Abbreviations: OGDH: oxoglutarate dehydrogenase; DLST: dihydrolipoamide S-succinyltransferase; DLD: dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase; ACMG: American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; GnomAD: Genome Aggregation Database; B: Benign; D: Damaging.

In the control group, altogether, 29 exonic rare variants were found in the OGDH gene (synonymous n = 23, missense n = 6), 2 in the DLST gene (missense n = 2), and 10 in the DLD gene (synonymous n = 9, missense n = 1). These missense alterations are all benign or likely benign variants according to ACMG, except for the DLST I393V. The DLST I393V alteration is classified as VUS (variant of uncertain significance) by ACMG, because it is not found in GnomAD. The rare alteration was identified in a healthy 70-year-old male.

The characteristics of the detected rare variants and VUS in the AD group are the following.

In the DLD gene (αKGDHc 3. subunit), exon 9 c.788 G > A (R263H, rs145670503) mutation was detected in the frontal, parahippocampal, and temporal lobes of one patient, who died at age 64. The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s in this patient was proven with histopathological analysis. At codon 263 of the DLD protein, arginine was replaced with histidine. This variant is present with low allele frequency in population databases (GnomAD 0.0008, ExAC 0.0007, 1000G 0.0004). According to the predictions software, the variant is pathogenic. Based on the available evidence, ACMG classifies it as a variant of uncertain significance, but previously, this alteration was detected in a CLA (Congenital Lactic Acidosis) patient and interpreted as a disease-causing mutation in a biallelic form [30]. In the healthy control screening, we did not find this mutation.

In the OGDH gene, only one rare missense variant was detected, which is classified as VUS by ACMG. The P471H alteration is not included in the population databases and was present neither in our control group nor in the literature. Prediction software qualified it as pathogenic; however, most of the clinically reported missense variants in the OGDH gene are known as benign (37 out of 44, 84.1%).

In the DLST gene (αKGDHc 2. subunit) in exon 9, we detected the c. 611 C > T (P204L, rs142872233) missense mutation, causing a proline/leucine amino acid change (P204L). Based on most prediction software, the alteration was classified as damaging and low MAF value (GnomAD 0.017, ExAC 0.016, 1000G 0.008). ‘MutationTaster’ and ‘SIFT’s predictions are disease-causing; it is a conserved amino acid. The allele frequency is low but higher than 0.001 (GnomAD 0.0017). Based on these, ACMG classifies the variant as uncertain significance. In the course of healthy control’s testing (n = 24), we found this mutation in a frozen brain sample with a lack of any neuropathological lesions typical for dementia (this patient died at age 74 in acute circulatory failure). It was present in an additional three individuals in our WES control group.

No differences were found regarding the presence or lack of mutations in the different analyzed brain regions.

4. Discussion

The αKGDHc mutation testing detected a heterozygous missense mutation (R263H) in the DLD gene, which was supposed to be damaging based on the lack of large genomic healthy control investigations. The significance of this variant is supported by the observation that the deficiency of αKGDHc and PDHc enzymes in the Krebs cycle may explain the glucose metabolism defect observed in the brains of AD patients [43]. Furthermore, impaired mitochondrial function has been described as an early and outstanding feature of the AD, suggesting that mitochondria play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of disease [12]. Due to mitochondrial dysfunction, tau is phosphorylated and aggregated, while hyperphosphorylated tau damages mitochondrial axonal transport, creating a vicious cycle that impairs nerve and synaptic functions, leading to memory impairment in AD [13].

The R263H alteration was identified in heterozygous form in all investigated regions of our patient’s brain, excluding the presence of a somatic mutation. This alteration is localized at a conserved nucleotide position; many types of prediction software score a pathogenic amino acid change (SIFT, PolyPhen2, Mutation Taster). This alteration was published in biallelic form in a severe patient’s primary mitochondrial disease, whose main symptoms were psychomotor retardation and epileptic encephalopathy [30]. This was the only reference to this variant pointing out its rarity. The difference between the two clinical manifestations may be explained by the presence of mono/biallelic form. Interestingly, the same mutation was found in one of our patients with suspected primary mitochondrial disease heterozygous form (unpublished data). This patient had early onset epilepsy, spastic paraparesis, and cognitive dysfunction. More brain samples should be investigated for major conclusions to support our risk factor theory.

Several substitutions were reported as VUS in the vicinity of the variant detected by us (c.788G > A, R263H) in the DLD gene. These are c.781T > G (F261V), c.782T > G (F261C), c.783T > G (F261L), and c.787C > A (R263S). This locus is associated with dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency and is a TF-binding site for PRDM4 (involved in cell differentiation). The GnomAD’s frequency data show a higher occurrence of R263H but no homozygous appearance in the European population [44].

So far in the DLD gene, 14 disease-causing substitutions are known in the literature: (I47T, K72E, G229C, G252C, G328C, M361V, E375K, I393T, E398K, I441T, D479V, R482K or R482G, P488L, and R495G) [20]. Based on X-ray crystallographic analysis, the described pathogenic mutations are localizing at the cofactor-binding site, or disulfide-exchange site, or on the homodimer interface domain [45]. The R263H amino acid change is localizing at DLD’s NAD+/NADH-binding region; in this region, only one mutation is described: G194C amino acid change. According to the literature, most mutations are localizing in the DLD interface region. Mutations in the interface domain (I480M) or NAD+/NADH-binding domain (G229C) cause milder symptoms [46]. Odièvre et al. reported similar mutations in the interface domain (R482G, D479V) with E3 deficiency without clinical and biochemical evidence [47].

Inhibition of dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD) results in increased phosphorylation of tau in nematode C. elegans—a model of AD [33]. A linkage association exists between AD and the chromosomal region of the DLD gene [48].

Mastrogiacomo et al. measured the activity of αKGDHc complex at post mortem AD brain samples. Compared with the controls, the activity was reduced at different levels in the different lobes [49].

However, the heterozygous rare variants of the OGDH and DLST are classified as variants with unknown significance by ACMG. We suppose that the DLST P204L alteration may be benign, since it is present in several control persons. Furthermore, for the rare variant in the OGDH gene (P471H), we found no evidence that it could play a role as a risk factor in the development of AD.

We did not find any genetic differences between various lobes indicating the presence of germline mutation.

We conclude that the rare variants of the heterozygous αKGDHc subunits can be rare genetic risk factors for AD enhancing the accumulation of tau. Since in the difference cerebral areas, the mutation profile of the αKGDHc was the same, we do not assume that somatic mutations are responsible for neuropathological alterations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miklós Palkovits for the frozen brain samples from the Human Brain Tissue Bank (Semmelweis University), for his professional advice and careful sample selection. We thank Emese Bányász for her science student work on this project in our laboratory. The Institute of Genomic Medicine and Rare Disorders is member of ERN for Rare Neurological Disorders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and M.J.M.; Data curation, M.J.M.; Formal analysis, A.I.; Investigation, D.C.; Methodology, K.P. and R.T.-B.; Resources, Z.G.; Software, A.G.; Supervision, M.J.M.; Validation, D.C., K.P. and R.T.-B.; Writing—original draft, D.C.; Writing—review and editing, M.J.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Hungarian National Brain Research Program KTIA_13_NAP-A-III/6 project and by the FIKP Fund. AG was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH, Grant No. OTKA PD 134449).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study has been authorized by the Committee of Science and Research Ethics of the Hungarian Ministry of Health (No. 6008/8/2002/ETT) and the Semmelweis University Regional Committee of Science and Research Ethics (No. 32/1992/TUKEB).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from subjects whose blood sample was involved in the study. Postmortem samples originating from the HBTB did not have informed consent. The use of these samples for research was approved by the Committee of Science and Research Ethics of the Hungarian Ministry of Health (No. 6008/8/2002/ETT) and the Semmelweis University Regional Committee of Science and Research Ethics (No. 32/1992/TUKEB).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results (datasets analyzed or generated during the study) can be found at the data warehouse of the Institute of Genomic Medicine and rare Disorders.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Deture M.A., Dickson D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019;14:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association 2014 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers. Dement. 2014;10:e47–e92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blennow K., de Leon M.J., Zetterberg H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2006;368:387–403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q., Sidorenko J., Couvy-Duchesne B., Marioni R.E., Wright M.J., Goate A.M., Marcora E., Huang K., Porter T., Laws S.M., et al. Risk prediction of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease implies an oligogenic architecture. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4799. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18534-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacace R., Sleegers K., Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular genetics of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease revisited. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:733–748. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Giau V., Senanarong V., Bagyinszky E., An S.S.A. Analysis of 50 Neurodegenerative Genes in Clinically Diagnosed Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:1514. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bis J.C., Jian X., Kunkle B.W., Chen Y., Hamilton-Nelson K.L., Bush W.S., Salerno W.J., Lancour D., Ma Y., Renton A.E., et al. Whole exome sequencing study identifies novel rare and common Alzheimer’s-Associated variants involved in immune response and transcriptional regulation. Mol. Psychiatry. 2020;25:1859–1875. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajmohan R., Reddy P.H. Amyloid-Beta and Phosphorylated Tau Accumulations Cause Abnormalities at Synapses of Alzheimer’s disease Neurons. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:975–999. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arriagada P.V., Growdon J.H., Hedley-Whyte E.T., Hyman B.T. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42:631. doi: 10.1212/WNL.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swerdlow R.H. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Cascades in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:1403–1416. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X., Wang W., Li L., Perry G., Lee H.G., Zhu X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014;1842:1240–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W., Zhao F., Ma X., Perry G., Zhu X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020;15:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng Y., Bai F. The association of tau with mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:2014–2019. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckert A., Nisbet R., Grimm A., Götz J. March separate, strike together—Role of phosphorylated TAU in mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014;1842:1258–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mosconi L., Pupi A., De Leon M.J. Brain Glucose Hypometabolism and Oxidative Stress in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1147:180–195. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sang S., Pan X., Chen Z., Zeng F., Pan S., Liu H., Jin L., Fei G., Wang C., Ren S., et al. Thiamine diphosphate reduction strongly correlates with brain glucose hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease, whereas amyloid deposition does not. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2018;10:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0354-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molnár M.J., Valikovics A., Molnár S., Trón L., Diószeghy P., Mechler F., Gulyás B. Cerebral blood flow and glucose metabolism in mitochondrial disorders. Neurology. 2000;55:544–548. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inczedy-Farkas G., Trampush J.W., Perczel Forintos D., Beech D., Andrejkovics M., Varga Z., Remenyi V., Bereznai B., Gal A., Molnar M.J. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and cognition: A case-series report. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014;29:315–321. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobolyi A., Bago A., Palkovits M., Nemeria N.S., Jordan F., Doczi J., Ambrus A., Adam-Vizi V., Chinopoulos C. Exclusive neuronal detection of KGDHC-specific subunits in the adult human brain cortex despite pancellular protein lysine succinylation. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020;225:639–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-020-02026-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambrus A. An Updated View on the Molecular Pathomechanisms of Human Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Light of Novel Crystallographic Evidence. Neurochem. Res. 2019;44:2307–2313. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02766-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambrus A., Torocsik B., Tretter L., Ozohanics O., Adam-Vizi V. Stimulation of reactive oxygen species generation by disease-causing mutations of lipoamide dehydrogenase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:2984–2995. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szabo E., Mizsei R., Wilk P., Zambo Z., Torocsik B., Weiss M.S., Adam-Vizi V., Ambrus A. Crystal structures of the disease-causing D444V mutant and the relevant wild type human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;124:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szabo E., Wilk P., Nagy B., Zambo Z., Bui D., Weichsel A., Arjunan P., Torocsik B., Hubert A., Furey W., et al. Underlying molecular alterations in human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase deficiency revealed by structural analyses of disease-causing enzyme variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019;28:3339–3354. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheu K.R., Cooper A.J.L., Koike K., Koike M., Lindsay J.G., Blass J.P. Abnormality of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in fibroblasts from familial Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1994;35:312–318. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stempler S., Yizhak K., Ruppin E. Integrating transcriptomics with metabolic modeling predicts biomarkers and drug targets for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheu K.F.R., Blass J.P. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;893:61–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: A target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005;360:2335–2345. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi Q., Xu H., Kleinman W.A., Gibson G.E. Novel functions of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex may mediate diverse oxidant-induced changes in mitochondrial enzymes associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2008;1782:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrus A., Adam-Vizi V. Human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3) deficiency: Novel insights into the structural basis and molecular pathomechanism. Neurochem. Int. 2018;117:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bravo-Alonso I., Navarrete R., Vega A.I., Ruíz-Sala P., García Silva M.T., Martín-Hernández E., Quijada-Fraile P., Belanger-Quintana A., Stanescu S., Bueno M., et al. Genes and Variants Underlying Human Congenital Lactic Acidosis-From Genetics to Personalized Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019;8:1811. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinonez S.C., Thoene J.G. GeneReviews® (Internet) University of Washington; Seattle, WA, USA: 2014. [(accessed on 3 April 2021)]. Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220444/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson G.E., Park L.C., Sheu K.-F.R., Blass J.P., Calingasan N.Y. The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2000;36:97–112. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(99)00114-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad W. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase suppression induces human tau phosphorylation by increasing whole body glucose levels in a C. elegans model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Exp. Brain Res. 2018;236:2857–2866. doi: 10.1007/s00221-018-5341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inczédy-Farkas G., Benkovits J., Balogh N., Álmos P., Scholtz B., Zahuczky G., Török Z., Nagy K., Réthelyi J., Makkos Z., et al. SCHIZOBANK—The Hungarian national schizophrenia biobank and its role in schizophrenia research. Orv. Hetil. 2010;151:1403–1408. doi: 10.1556/oh.2010.28943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van der Auwera G.A., Carneiro M.O., Hartl C., Poplin R., del Angel G., Levy-Moonshine A., Jordan T., Shakir K., Roazen D., Thibault J., et al. From fastQ Data to High-Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013;43:11.10.1–11.10.33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cingolani P., Platts A., Wang L.L., Coon M., Nguyen T., Wang L., Land S.J., Lu X., Ruden D.M. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., Brown G., Chao C., Chitipiralla S., Gu B., Hart J., Hoffman D., Hoover J., et al. ClinVar: Public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D862-8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kearney H.M., Thorland E.C., Brown K.K., Quintero-Rivera F., South S.T. American College of Medical Genetics standards and guidelines for interpretation and reporting of postnatal constitutional copy number variants. Genet. Med. 2011;13:680–685. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182217a3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., Grody W.W., Hegde M., Lyon E., Spector E., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kopanos C., Tsiolkas V., Kouris A., Chapple C.E., Albarca Aguilera M., Meyer R., Massouras A. VarSome: The human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:1978–1980. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franklin by Genoox. [(accessed on 4 January 2021)]; Available online: https://franklin.genoox.com.

- 43.Simoncini C., Orsucci D., Caldarazzo Ienco E., Siciliano G., Bonuccelli U., Mancuso M. Alzheimer’s pathogenesis and its link to the mitochondrion. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/803942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lek M., Karczewski K.J., Minikel E.V., Samocha K.E., Banks E., Fennell T., O’Donnell-Luria A.H., Ware J.S., Hill A.J., Cummings B.B., et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brautigam C.A., Chuang J.L., Tomchick D.R., Machius M., Chuang D.T. Crystal structure of human dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase: NAD +/NADH binding and the structural basis of disease-causing mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;350:543–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quintana E., Pineda M., Font A., Vilaseca M.A., Tort F., Ribes A., Briones P. Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (DLD) deficiency in a Spanish patient with myopathic presentation due to a new mutation in the interface domain. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010;33:315–319. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Odièvre M.-H., Chretien D., Munnich A., Robinson B.H., Dumoulin R., Masmoudi S., Kadhom N., Rötig A., Rustin P., Bonnefont J.-P. A novel mutation in the dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase E3 subunit gene (DLD) resulting in an atypical form of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase deficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2005;25:323–324. doi: 10.1002/humu.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown A.M., Gordon D., Lee H., De Vrièze F.W., Cellini E., Bagnoli S., Nacmias B., Sorbi S., Hardy J., Blass J.P. Testing for linkage and association across the dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase gene region with Alzheimer’s disease in three sample populations. Neurochem. Res. 2007;32:857–869. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9235-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mastrogiacomo F., Bergeron C., Kish S.J. Brain α-Ketoglutarate Dehydrogenase Complex Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 1993;61:2007–2014. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results (datasets analyzed or generated during the study) can be found at the data warehouse of the Institute of Genomic Medicine and rare Disorders.