Abstract

Purpose

To develop a prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted radiotherapeutic for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with optimized efficacy and minimized toxicity employing the β-particle radiation of 177Lu.

Methods

We synthesized 14 new PSMA-targeted, 177Lu-labeled radioligands (177Lu-L1–177Lu-L14) using different chelating agents and linkers. We evaluated them in vitro using human prostate cancer PSMA(+) PC3 PIP and PSMA(−) PC3 flu cells and in corresponding flank tumor models. Efficacy and toxicity after 8 weeks were evaluated at a single administration of 111 MBq for177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3, 177Lu-L5 and 177Lu-PSMA-617. Efficacy of 177Lu-L1 was further investigated using different doses, and long-term toxicity was determined in healthy immunocompetent mice.

Results

Radioligands were produced in high radiochemical yield and purity. Cell uptake and internalization indicated specific uptake only in PSMA(+) PC3 cells. 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 demonstrated comparable uptake to 177Lu-PSMA-617 and 177Lu-PSMA-I&T in PSMA-expressing tumors up to 72 h post-injection. 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 also demonstrated efficient tumor regression at 8 weeks. 177Lu-L1 enabled the highest survival rate. Necropsy studies of the treated group at 8 weeks revealed subacute damage to lacrimal glands and testes. No radiation nephropathy was observed 1 year post-treatment in healthy mice receiving 111 MBq of 177Lu-L1, most likely related to the fast renal clearance of this agent.

Conclusions

177Lu-L1 is a viable clinical candidate for radionuclide therapy of PSMA-expressing malignancies because of its high tumor-targeting ability and low off-target radiotoxic effects.

Keywords: Prostate-specific membrane antigen, β-Particle, Prostate cancer, Lutetium, Metastatic

Introduction

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type II metalloprotease and valuable clinical biomarker of prostate cancer (PC) [1, 2]. Pathology reports have revealed that over 90% of PC specimens express high levels of PSMA [3], as do most other solid malignancies [4], the latter demonstrating expression in tumor-associated neovasculature [5–7]. Lower levels are found in physiologically normal tissues such as the kidneys, salivary glands and small intestine [8]. High expression of PSMA in PC has led to its use as a target for delivering a range of diagnostic and therapeutic agents for positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), nanoparticles and optical agents, among others [1,9].The PSMA-targeted, low-molecular-weight PET agents68Ga-PSMA-11 [10], 18F-DCFPyL [11] and 18F-PSMA-1007 [12] have revolutionized imaging-based detection of PC.

Although the recently introduced PSMA-targeted radiopharmaceuticals 177Lu-PSMA-617, 177Lu-PSMA-I&T [13–15] (Fig. 1a) and 131I-MIP1095 [16] are promising, xerostomia remains a side effect, and long-term renal toxicity has emerged as more patients are treated more frequently and are studied over longer periods [17]. Prospective data are still lacking that address the potential issue of long-term toxicity.

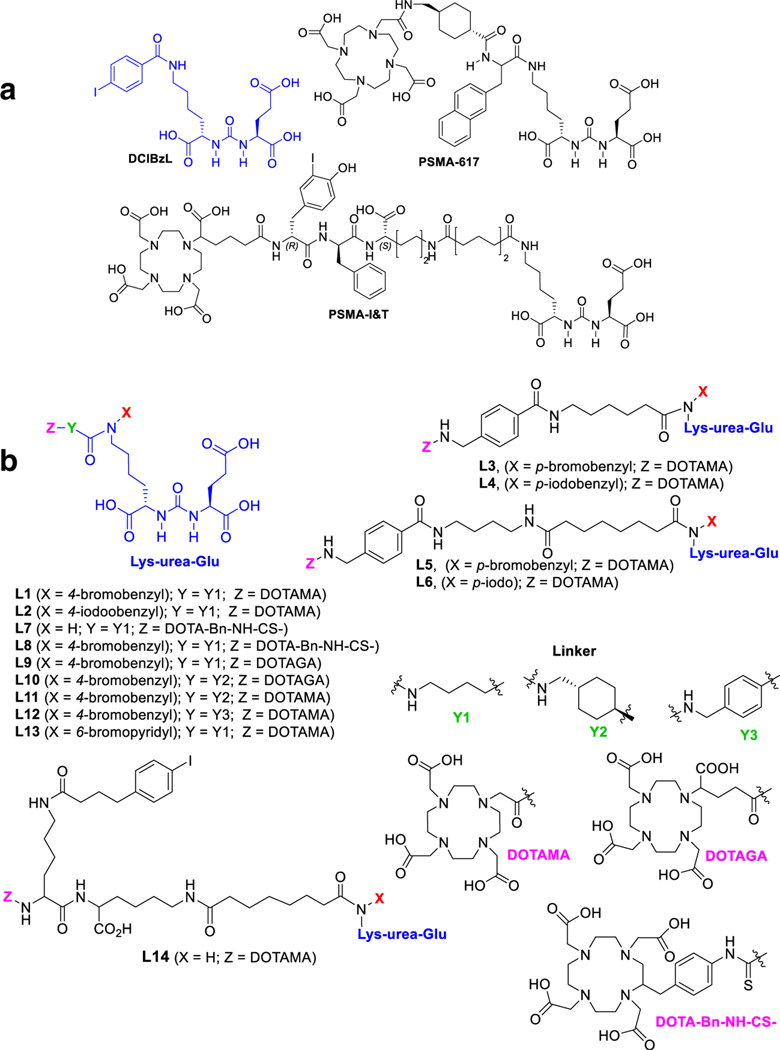

Fig. 1.

a Chemical structures of DCIBzL, PSMA-617 and PSMAI&T. b Chemical structures of the new PSMA-based compounds, L1–L14

We and others have investigated the pharmacokinetics of radiolabeled PSMA-targeted Lys-Glu-ureas to promote safe and effective clinical application for imaging and therapy of PC [1, 18]. So far, two general classes of high-affinity (Ki < 20 nM) agents have surfaced, which we refer to as type I and type II agents (Supplementary Figure S1). Type I agents demonstrate high PSMA-specific tumor uptake and long retention, however, with high uptake in some PSMA-expressing normal tissues including the kidney and spleen [19]. Examples include 99mTc-oxo [20], 64Cu-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7–2triacetic acid (NOTA) [21], 68Ga-PSMA-11 [22] and 68Ga-/177Lu-PSMA-I&T [14]. Others have recently developed several high-affinity radioligands with prolonged tumor retention using an albumin-binding 4-(p-iodophenyl)butyric acid motif [23–25]. That has also led to high retention in the murine renal cortex and other normal organs, indicating that such agents are type I. Type II agents display high tumor uptake and retention, and fast clearance from most normal tissues, including kidney and salivary glands, producing high tumor-to-background ratios [20, 21]. Type II agents include those developed by us [26] and PSMA-617 [13].

Here we report preclinical evaluation of a new series of theranostic ligands, 177Lu-L1–177Lu-L14, targeting PSMA (Fig. 1). We investigate the 4-halo-benzyl derivatives of LysGlu-urea because of sustained tumor uptake and high efficacy in human PC xenografts demonstrated by 125I-DCIBzL (Fig. 1) [27]. Additionally, the α-particle-emitting, 211At-labeled version of DCIBzL proved effective in both flank and micrometastatic models [28]. We have synthesized 14 new 177Lu-labeled radioligands and evaluated their pharmacokinetics, capacity to kill cells in vitro and tumor control in vivo. We have taken a systematic and graded approach to provide an optimized agent with reduced off-target effects for 177Lu and, by extension, possibly 212Pb or 225Ac, each of which also utilizes a 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-based macrocyclic chelator.

Materials and methods

New compound synthesis, spectral characterization data, including a new microwave-assisted radiolabeling method, as well as cell culture and tissue biodistribution methods, are provided in the Supplementary Material. All compounds were synthesized using solution-phase chemistry based on our well-established methods [26, 29]. Ligands L1–L4, L7–L9 and L13 possess a short and flexible linker, while L10–L12 contain a rigid alicyclic or aromatic linker. In contrast, L5, L6 and L14 have a longer linker similar to our previous lead agent [26]. Binding affinities of the new ligands were determined by a competitive fluorescence-based assay reported from our laboratory [29]. All 177Lu-labeled radioligands were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to remove unreacted ligand from the radiolabeled material to ensure high specific radioactivity.

Cell uptake and internalization studies and clonogenic survival assay were performed as previously reported [30, 31]. Animal studies were carried out in compliance with the regulations of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Small animal SPECT/CT imaging and histology

Single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) imaging and histology were performed after administration of 177Lu-L1 (37 MBq, n = 2–3 per time-point) via tail vein injection in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP and PSMA(−) PC3 flu flank tumor models. For SPECT/CT, we followed a previously reported method [29] with data analyzed using AMIDE software (http://amide.sourceforge.net/). Tissues were collected for histology at different time points. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining were done as previously described by us [32]. Tumor sections were stained for γ-H2AX (phospho S139), a marker of DNA double-strand breaks, according to [33].

PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy

Three separate in vivo treatment experiments were performed using the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP flank tumor model. Mouse body weight and tumor volume were monitored every 3 days. The formula used for calculation of tumor volume was V =width2 × length/2.Endpointcriteria as defined by the ACUC were weight loss ≥15%, tumor volume>1800 mm3, active ulceration of the tumor or abnormal behavior indicating pain or distress. Those definitions were also used for Kaplan–Meier analysis. For the first experiment, antitumor efficacy was evaluated for a single-dose (111 MBq) intravenous injection of 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3, 177Lu-L5 (n = 10 mice per group), 177Lu-PSMA-617 (n = 9) vs. saline (n = 9). That was a direct comparison study and employed the same batch of male NOD/SCID mice. The study was commenced 14–18 days post-inoculation of tumor cells, when tumor volumes reached ~60–85 mm3 (Supplementary Table 21). Acute radiotoxicity of the 177Lu treatment groups [(177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3, 177Lu-L5 and 177Lu-PSMA-617 vs. saline) (n=3)] after 8 weeks was evaluated at the Johns Hopkins Phenotyping Core. Mice treated with 177Lu-L1 (n = 6) and 177Lu-PSMA-617 (n=5) were monitored for 190 days. The second treatment study was performed using 177Lu-L1 with a variable single dose [18.5,37 and 111 MBq vs. control (n=5)] up to 80 days. A third experiment was done using single doses of 177 Lu-L1 of 1.9, 9.3, 18.5 MBq vs. control with saline injection (n = 7). Long-term radiotoxicity of 177Lu-L1 (single dose, 111 MBq, n=3) was assessed in immunocompetent CD-1 mice (Charles River) at 1 year after injection of the agent.

Radiation dosimetry

Murine time-integrated activity per unit of mass [TIA/g], was calculated with fits to the biodistribution data: bi-exponential for kidney and salivary glands (with physical decay constraint imposed for the salivary glands) and mono-exponential for the tumor. Conversion from TIA to absorbed dose was done using (1) a power law formula derived from a fit to spherical data generated from GEANT4 Monte Carlo for the tumor and salivary glands, and (2) the absorbed fraction from a murine kidney model, obtained by scaling the MIRD #19 kidney model [34] to murine dimensions using GEANT4 Monte Carlo for the kidneys.

Data analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Cell uptake and biodistribution studies were compared using the unpaired two-tailed t test. Survival analysis was performed with Kaplan–Meier curves and the log-rank test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Chemistry and radiochemistry

We synthesized the series of compounds for structure–activity relationships (SAR) shown in Fig. 1. All ligands bear a bromo- or iodo-benzyl Lys-urea-Glu-targeting moiety, except for L7 and L14. The effect of chelating agent was investigated in ligands L7 and L8 by replacing DOTA-monoamide (DOTAMA), used in L1, by S-2-(4- isothiocyanatobenzyl) DOTA (DOTA-Bn-NCS) and in L9 using DOTA-glutaric acid (DOTAGA). Ligands L10 and L11 have a rigid cyclohexyl linker, as in PSMA-617, with DOTAGA and DOTAMA chelating agents for assessing the effect of a rigid linker and choice of chelator compared to L9 and L1, respectively. Ligand L13 has a bromo-pyridyl group on the targeting urea as in our clinical PETagent, 18F-DCFPyL. Ligand L14 has an albumin-binding moiety, 4-(p-iodophenyl)butyric acid, on our previously reported PSMA-binding targeting platform as recently studied by several research groups [23–25] to investigate the effect of 4-(p-iodophenyl) on biodistribution. All ligands were radiolabeled with 177Lu in high radiochemical yield (> 98%) and purity (> 99%) using both conventional and microwave-assisted methods.

Affinity, cell uptake and internalization

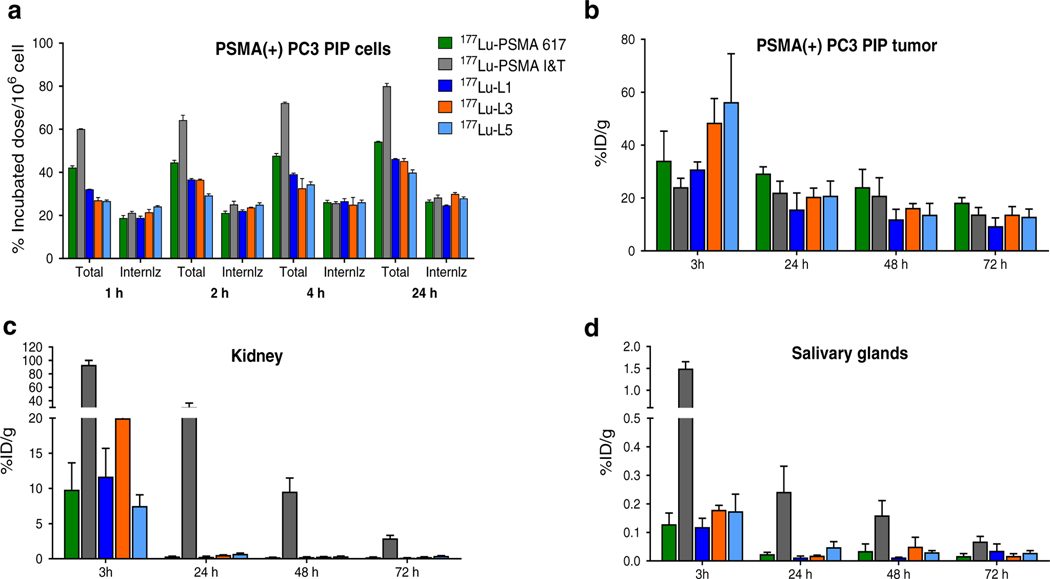

All ligands demonstrated high binding affinity to PSMA with Ki values ranging from 0.03 to 8 nM (Table 1). The stable lutetium analog of L1 (Lu-L1) showed a threefold increase in binding affinityoverL1, suggesting that all radioligands (177Lu-L) of this class should also display a similar increase in binding affinity compared to the corresponding free ligand. Cell uptake and internalization data up to 24 h of incubation with 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 are shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1. The total cell surface uptake and internalization of the radioligands in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells increased between 2 and 24 h. Both 177Lu-PSMA-I&T and 177Lu-PSMA-617 displayed significantly higher cell uptake within the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells, ~60% and ~40% of the incubated dose, respectively, compared to 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 initially, which showed uptake of ~30% (Fig. 2). However, the percentage of internalization for all 5 compounds was in the same range of ~18–24% at 1 h to 25–30% at 24 h of incubation. The uptake in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells could be blocked by treatment with an excess (~ 10 μM) of known PSMA inhibitor, ZJ43 [35], indicating binding specificity to PSMA.

Table 1.

Physical properties and PSMA binding activity of the new compounds

| Ligand | Molecular weight | Ki [nM] |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | 973.87 | 0.20–0.33 nM |

| L2 | 1020.87 | 0.09–34 nM |

| L3 | 1121.05 | 0.14–0.39 nM |

| L4 | 1168.05 | 0.46–0.63 nM |

| L5 | 1234.21 | 0.35–0.93 nM |

| L6 | 1281.21 | 0.29–0.81 nM |

| L7 | 970.06 | NA |

| L8 | 1139.08 | 0.08–0.16 nM |

| L9 | 1045.94 | 0.02–0.05 nM |

| L10 | 1086.00 | 0.43–1.2 nM |

| L11 | 1013.94 | NA |

| L12 | 1007.89 | 0.22–4.03 nM |

| L13 | 974.86 | 0.23–8.10 nM |

| L14 | 1390.34 | 0.13–2.15 nM |

Fig. 2.

a Cell uptake and internalization data in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells (percentage incubated dose per 1 million cells, mean ± SD, n = 3). Selected biodistribution data [PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumor (b), kidney (c) and salivary glands (d)] after administration of 1.85 ± 0.37MBq of 177Lu-PSMA-617, 177Lu-PSMAI&T, 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 (%ID/ g, mean ± SD, n = 4 per group)

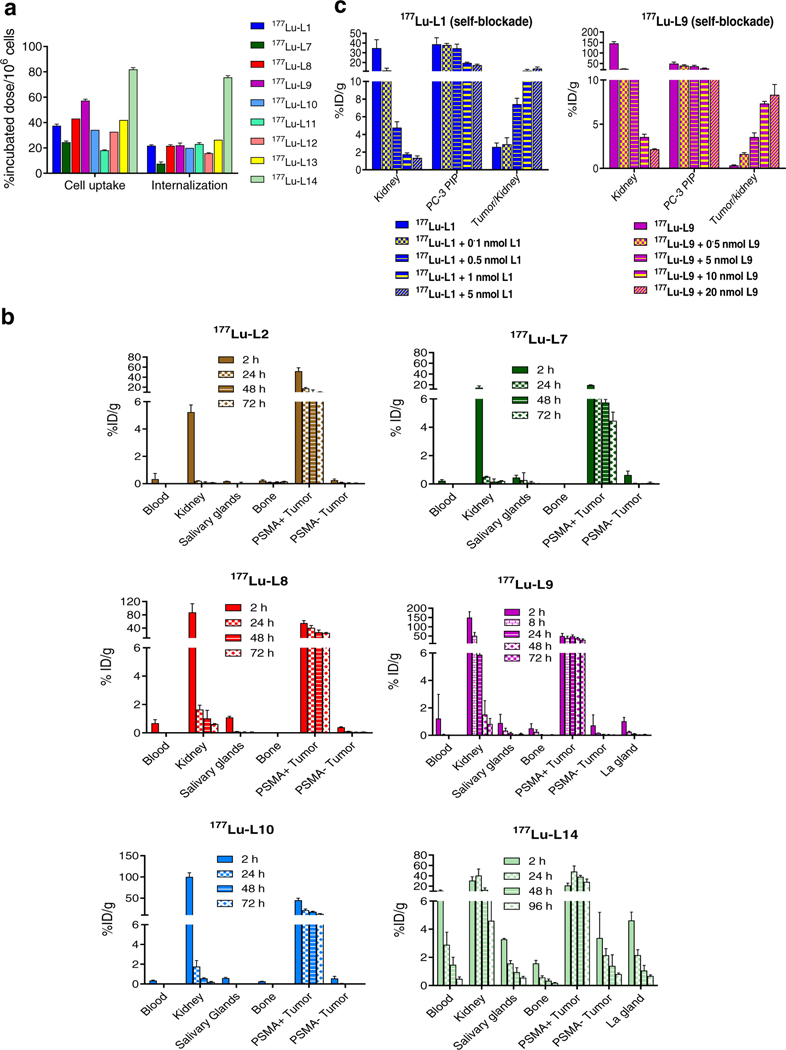

Cell uptake and internalization of selected radioligands from the series were assessed at 2 h post-incubation (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 2) and compared to 177Lu-L1. DOTA-Bn-SCN-chelated 177Lu-L8, with a p-bromo-benzyl moiety, displayed higher uptake and nearly > 1.5-fold higher internalization compared to 177Lu-L7, which does not possess a p-bromo-benzyl group. Significantly, 177Lu-L9, which is equipped with a DOTAGA chelating group, displayed higher uptake compared to 177Lu-L8 and 177Lu-L1. In contrast, 177Lu-L10, which also employs DOTAGA, but is also modified with a rigid cyclohexyl linker, showed lower uptake and internalization compared to 177Lu-L8 and 177Lu-L9. Structurally unrelated radioligand 177Lu-L14, with the albumin-binding 4-(p-iodophenyl)-butyric acid moiety, displayed highest uptake and internalization from the series at 2 h. Overall, 177Lu-L8 and 177Lu-L9, which differ only with respect to chelator, demonstrated significantly higher uptake in PSMA(+) PIP cells compared to 177Lu-L1, while the radioligands with a rigid linker (177Lu-L10, 177Lu-L11 and 177Lu-L12) displayed significantly lower PSMA(+) cell binding compared to similar analogs with linear linkers (e.g., 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L9).

Fig. 3.

a Cell uptake and internalization data of the selected radioligands in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells compared to 177Lu-L1 (percentage incubated dose per 1 million cells, mean ± SD, n = 3). b Biodistribution data of 177Lu-L2, 177Lu-L7, 177Lu-L8, 177Lu-L9, 177Lu-L10 and 177Lu-14.c Self-blocking study performed of 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L9 using variables doses of the respective ligands. (%ID/g, mean± SD, n = 4 per group)

Biodistribution

In vivo pharmacokinetics of the new compounds are presented in Figs. 2 and 3. Mouse body and tumor weights for the selected agents are provided in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. Except for 177Lu-L7, which is without the p-bromo-benzyl-modified Lys-Glu-urea moiety, and agents with a rigid linker (177Lu-L11 and 177Lu-L12), all compounds demonstrated high PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumor uptake (>18% ID/g) at 24 h post-injection. Biodistribution of 177Lu-PSMA-617, 177LuPSMA-I&T, 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 are shown in Fig. 2b. At 3 h post-injection, significantly higher tumor uptake was observed for 177Lu-L3 [52.6 ± 4.9% injected dose per gram (ID/g)] and 177Lu-L5 (56.3 ± 18.3 %ID/g), while the tumor uptake for 177Lu-L1 was comparable to 177Lu-PSMA617 and 177Lu-PSMA-I&T. However, after 24 h, both 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 demonstrated rapid clearance from the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumors, ultimately providing tumor uptake comparable to 177Lu-PSMA-617 and 177Lu-PSMA-I&T. In contrast, 177Lu-L1 displayed significantly lower tumor uptake compared to 177Lu-PSMA-617 at 24 h. At 72 h post-injection, 177Lu-PSMA-617 displayed higher tumor uptake compared to 177Lu-PSMA-I&T, 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L3 and comparable to 177Lu-L5. Uptake in the PSMA(−) PC3 flu tumor was low (<0.3% ID/g) for all compounds starting at 3 h post-injection, demonstrating high specificity of the compounds tested.

Although agents tested demonstrated similar tumor uptake, they were quite different with respect to normal tissue distribution. Organs that normally express PSMA, for example, kidneys, salivary glands and spleen, showed significantly higher radiotracer uptake for 177Lu-PSMA-I&T than for the other compounds. Even though 177Lu-PSMA-I&T showed a certain degree of renal clearance over time, demonstrating 30.4 ± 12.5 %ID/g at 24 h, 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3, 177Lu-L5 and 177LuPSMA-617 showed an almost tenfold clearance, resulting in kidney uptake <0.5 ID/g, over the same period of time.

Selected tissue biodistribution data of 177Lu-L2, the p-iodo-benzyl analog of 177Lu-L1, and ligands without any halo-benzyl-modified urea-targeting moiety, 177Lu-L7 and 177Lu-L14, and p-bromobenzyl-modified agents, 177Lu-L8, 177Lu-L9 and Lu-L10, are shown in Fig. 3b. 177Lu-L2 displayed nearly similar biodistribution properties as 177Lu-L1. While both 177Lu-L7 and 177Lu-L8 were modified with the DOTA-Bn-SCN chelating agent, tumor uptake and retention of 177Lu-L8 were significantly higher at all time points compared to 177Lu-L7, further emphasizing the importance of the p-bromobenzyl group on tumor retention. Similarly, DOTAGA-modified 177Lu-L9 displayed significantly higher tumor uptake and retention compared to 177Lu-L1, however, with nearly threefold higher kidney uptake at 2 h.

Biodistribution of 177Lu-L14 was consistent with reported albumin-binding agents, with high and sustained tumor uptake. Although the agent initially displayed lower renal uptake compared to 177Lu-PSMA-I&T, only ~ threefold clearance of activity was observed during the time course of the study, for example displaying 17.47 ± 4.18 %ID/g after 48 h, compared to a tenfold wash-out of the activity for 177Lu-PSMA-I&T over that same period of time (Figs. 2 and 3). 177Lu-L14 also showed the highest blood uptake from the series, 16.13± 2.33 %ID/g at 2 h post-injection, followed by 5.05 ± 0.05 %ID/g at 24 h and 2.48 ± 0.44 %ID/g at 48 h. Spleen salivary and lacrimal gland uptake and retention of 177Lu-L14 were highest in the series.

To mitigate renal uptake, self-blocking studies were performed for 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L9. Among newly synthesized agents, those two displayed the lowest and highest kidney uptake (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Tables 19 and 20) at 2 h post-injection, respectively. Different self-blocking doses were co-administrated with radioligands compared to the control with no blocking dose. Of note, both radioligands displayed a greater than sixfold decrease in kidney uptake using ~ 0.5 nmol of blocker. Owing to its low kidney uptake, 177Lu-L1 maintained comparable tumor uptake compared to unblocked (34.7 ± 8.2 vs. 38.7 ± 13.5% D/g) while demonstrating significant blockade in kidney uptake (34.74 ± 17.37 vs. 4.76 ± 1.35% D/g). 177Lu-L9 also displayed significant blocking within the PSMA-expressing lacrimal and salivary glands.

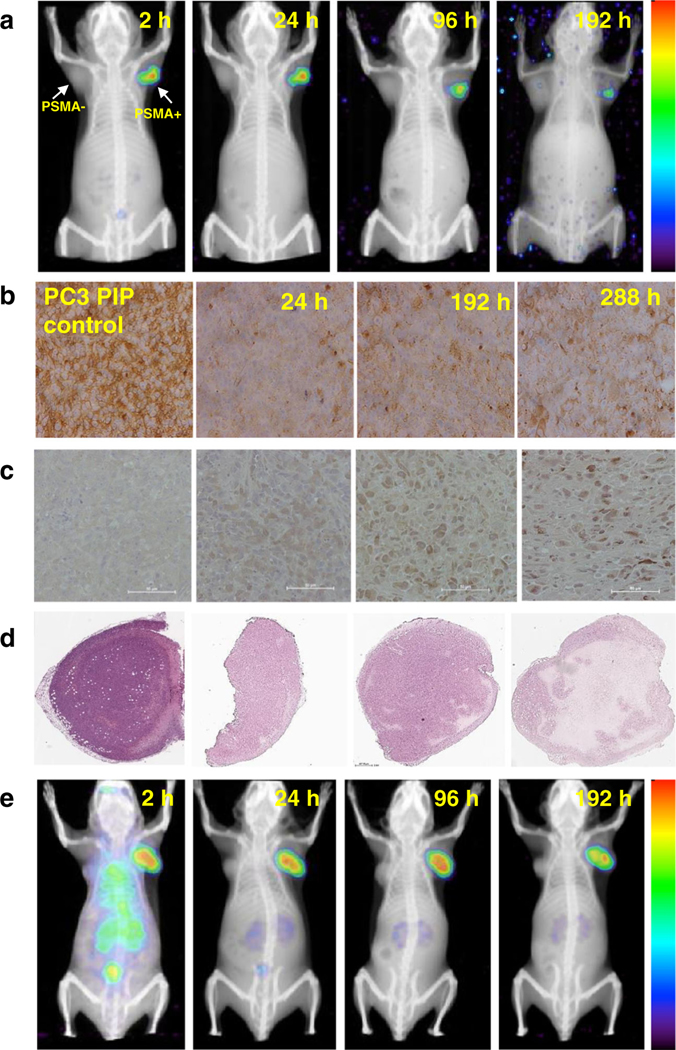

Tumor imaging by in vivo SPECT/CT and ex vivo histology

SPECT/CT imaging of 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L14 (Fig. 4a and e) was also performed to check in vivo pharmacokinetics panoramically. As anticipated from the biodistribution data, SPECT/CT images during 2–192 h after administration of 177Lu-L1 confirmed high uptake in the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumors (right) but not in the PSMA(−) PC3 flu tumors (left). Also, consistent with the biodistribution data, the ligand displayed very low uptake in kidneys and all normal tissues, including after 2 h post-administration. We also established the status of PSMA expression within the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumors during the imaging experiments by IHC and tumor morphology by H&E staining. We detected a decrease in PSMA expression in the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumors at all time points after administration of 177Lu-L1 (37 MBq) compared to tumor harvested from control animals that did not receive radioactivity (Fig. 4b). This was attributed to the loss of PSMA-expressing tumor cells following effective therapy. However, there was an apparent rebound in PSMA expression over time. That rebound could represent PSMA that was internal and not available for IHC staining (or radiotherapy) at the earlier time points. Additionally, significant DNA damage was visualized by γ-H2A.X staining at 7 d compared to 24 h and in the non-treated control. Whole-tumor H&E staining at 7 d and specifically at 12d presented extensive necrosis within the treated tumors (Fig. 4d), indicating significant cell kill using 37 MBq of 177Lu-L1. A theranostic SPECT/CT imaging study was also performed for 177Lu-L8 using 111 MBq from 24 to 192 h post-treatment (Supplementary Figure 2), although pharmacokinetics were inferior to 177Lu-L1.

Fig. 4.

a and e SPECT/CT imaging 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L14 (37 MBq) in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP and PSMA(−) PC3 flu tumor bearing mouse during 2–192 h (n = 2). b Representative IHC staining of PSMA expression. c γ-H2A.X staining to demonstrate DNA damage (scale bar: 50 μm, 20X). d H&E staining of whole tumor issue sections within the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumor for untreated control and after administration of 177Lu-L1 24 h, 7 and 12 d (left to right) (scale bar:660μm, 2X)

Radionuclide therapy

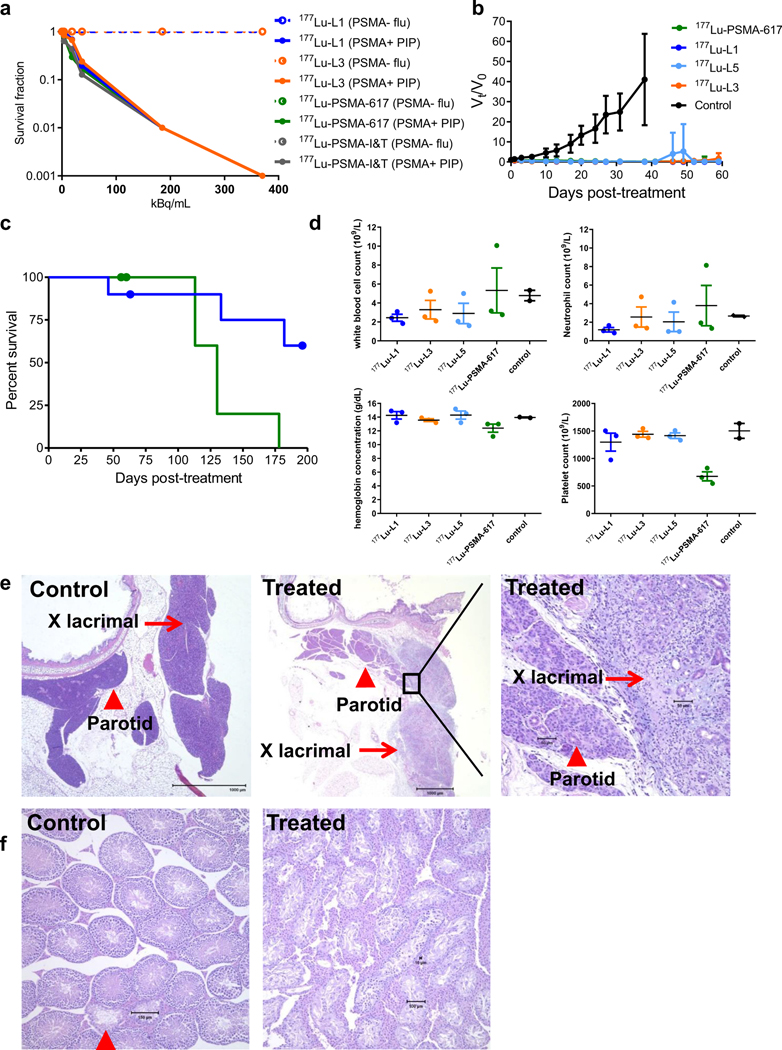

The colony-forming ability of PSMA(+) PC3 PIP cells after incubation with 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3, 177Lu-PSMA-617 and 177Lu-PSMA-I&T is shown in Fig. 5a. Significant loss of colony formation was observed only after 48 h of incubation for all compounds. The D0 (37% survival) of 177Lu-PSMA617, 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L3 were in the same range (24–32 kBq/mL), whereas that for 177Lu-PSMA-I&T was much lower (~9.5 kBq/mL),as anticipated from the cell uptake data. PSMA(−) PC3 flu cells did not display any cell kill effect under similar experimental conditions for any radioligand.

Fig. 5.

In vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy of PSMA-targeted radioligands. a In vitro cell kill effect of 177Lu-PSMA-617, 177Lu-PSMA I&T, 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L3 after 48 h incubation in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP and PSMA(−) flu cells (data mean ± SD, n = 3) at37 °C. b Effect of 177Lu-PSMA-617 (n = 9), 177Lu-L1,177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 (n = 10) on the PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumor growth (data mean ± SD) after administration of 111 MBq via tail-vein injection. c Kaplan−Meier plot of survival for the group treated with 177Lu-PSMA-617 (n = 9) and 177Lu-L1 (n = 10), censored event (dot), three mice were removed from each group at 8 weeks for evaluating acute toxicity. d Hemoglobin and blood counts (white blood cells, neutrophil and platelets) level after 8-week. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3). e and f Acute toxicity evaluation by H&E staining of lacrimal glands and testes. Extraorbital lacrimal glands control untreated (left); 177Lu-PSMA-617(middle and right), adjacent parotid gland (arrowhead) is spared (middle); higher magnification, showing acinar loss, with chronic and active inflammation (right). Testis control untreated, active spermatogenesis, near the rete testis 2 tubules (arrowhead) contain only Sertoli cells (left), 177Lu-PSMA-617 (right). Diffuse and near complete loss of seminiferous epithelium, with prominent interstitial cells

To evaluate in vivo efficacy, initially, a pilot study was conducted using PSMA(+) PC3 PIP tumors with a single intravenous dose of the vehicle (control) or 111 MBq of 177Lu-PSMA-617, 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L3 or 177Lu-L5 (Supplementary Table 21 and Fig. 5b). Kaplan−Meier survival plots, individual tumor volume and body weight measurements for each animal are shown in Supplementary Figures 3–8. The tumor volume of mice in the control group reached > 5 times the initial volume within 14 days. All treated groups showed significant tumor regression up to 8 weeks post-treatment. The survival among treatment groups was statistically significant by the log-rank test compared to the untreated group (P < 0.0001 for 177Lu-PSMA-617 and 177Lu-L1, P < 0.001 for 177Lu-L5, and P < 0.01 for 177Lu-L3). As shown in Supplementary Table 21, only one mouse from the group treated with 177Lu-L5 or 177Lu-PSMA-617 reached a relative tumor volume > 4 times the initial volume, and two mice from the group treated with 177Lu-L3 progressed to that degree. The cause of death of the other mice treated with the agents in Supplementary Table 21 was due to a sudden decrease in body weight, and was not directly related to tumor growth. While treatment monitoring was terminated for 177Lu-L3 and 177Lu-L5 at 8 weeks, treatment was continued for 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-PSMA-617 until the predefined end-point was reached. Figure 5c displays the survival data of 177Lu-L1 and 177LuPSMA-617. Median survival for 177Lu-PSMA-617 was 130 days, whereas for 177Lu-L1, survival was still > 60% of animals at 190 days after administration.

Toxicity was assessed initially at 8 weeks post-treatment through complete blood analysis and necropsy. Selected toxicity data are shown in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Tables S22–S24. All animals that underwent radiotherapy had normal creatinine (0.3–0.4 mg/dL) and blood urea nitrogen levels. All three mice receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 had significantly lower platelets than those in the other treatment groups. One of those mice also had the greatest tumor burden, and the highest neutrophil count of the mice tested, including possible lung metastases (<1 mm) (Supplementary Figure 13).

Anatomic pathology identified significant changes in lacrimal grands (Fig. 5e) and testes (Fig. 5f) in all treated groups. Lacrimal glands (extraorbital and infraorbital) in all treatment groups had marked degenerative, inflammatory and fibrotic changes. Salivary glands were generally spared, but mice receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 had mild changes in parotid glands. Testes of one mouse receiving 177Lu-L5 and all three mice receiving 177Lu-PSMA-617 had the most severe degenerative changes and loss of seminiferous epithelium. Changes in kidneys were minimal in all treated groups. One mouse receiving 177Lu-L5 had thymic lymphoma, which is an expected cause of death in naïve NOD/SCID mice [36], and may be accelerated by irradiation and certain carcinogens. Possible mild changes in ameloblasts and odontoblasts were identified in limited incisor sections examined for all treated mice.

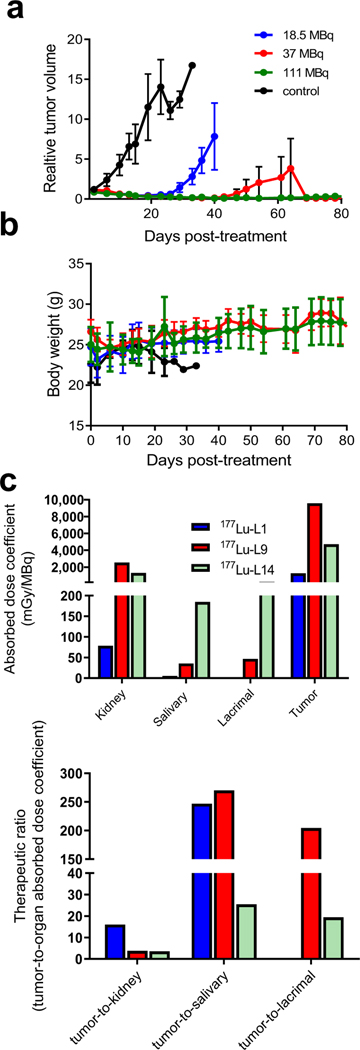

Given that 177Lu-L1 demonstrated a suitable treatment effect, we performed tumor growth delay studies using escalated doses from 18.5, 37 and 111 MBq (n = 5 per group) up to 80 days and a separate study with lower doses (1.9, 9.3, 18.5 MBq, n = 7) (Figures S10–S12). As shown in Fig. 6, 177Lu-L1, exhibited tumor growth delay for all treated groups except for the 1.9 MBq treatment group compared to untreated. Long-term radiotoxicity was also evaluated for 177Lu-L1 after administration of 111 MBq in tumor-free CD-1 mice (n = 3). One treated mouse had a small (<1 mm) adenoma of the lung. That is not a surprising finding in CD-1 mice in chronic studies [37]. We speculate that the cause of the death of another mouse after 11 months most likely related to similar natural death events of CD-1 mouse of this age [37]. No measurable toxicity was found for the treated mice compared to controls in the kidneys with acceptable blood urea nitrogen, albumin, creatinine and total protein level [38]. In contrast to 8 weeks post-treatment, changes in lacrimal glands and testes were minimal after 1 year. Changes in adrenal glands, kidneys, urinary bladder and liver were mild, but may exceed expected age-related changes and warrant further assessment (Supplementary Figure 15 and Tables 25–26).

Fig. 6.

Radiotherapy performed with 177Lu-L1 (n = 5) in PSMA(+) PC3 PIP flank tumor. a Tumor growth curves relative to the tumor volume at day 0 (set to 1) for mice that received saline, mice treated with a single dose of 18.5 MBq, 37 MBq and 111 MBq. b Body weight of the corresponding treatment groups. c Murine radiation absorbed dose coefficients of selected organs for 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L9 and 177Lu-L14 (top) and therapeutic ratio (tumor-to-normal organ absorbed dose coefficients) (bottom)

Organ absorbed doses

Figure 6c provides selected mouse organ absorbed dose coefficients (mGy/MBq) for 177Lu-L1, 177Lu-L9 and 177Lu-L14. For all radioligands, the kidney received the highest absorbed dose, as expected from the biodistribution study. The absorbed dose of 177Lu-L1 for the kidneys and salivary glands are low, and demonstrated fourfold higher tumor-to-kidney absorbed dose coefficients (therapeutic ratio) compared to 177Lu-L9 and 177 Lu-L14.

Discussion

Here we investigated SAR of a new series of PSMA-targeted low-molecular-weight 177Lu-labeled theranostic agents. Structural features we investigated included the presence of a p-halo-benzyl moiety attached to the lysine ε-amine, chelating agent, linker length and rigidity, and the attachment of an albumin-binding moiety (Fig. 1b). We also optimized aspects of the radiosynthesis and assessed short- and long-term toxicity of a lead agent, namely, 177Lu-L1.

Agents synthesized here are derived from our own linker-based targeting platform [39, 40]. The attachment of a p-halo-benzyl moiety to the PSMA-targeting Lys-urea-Glu provided high tumor retention and fast normal tissue clearance. First, we observed significantly lower PSMA(+) cell binding affinity both in vitro and in vivo for 177Lu-L7, which is without the p-halo-benzyl moiety, compared to 177Lu-L1 and 177Lu-L8, which have it. Second, we showed that radioligands with macrocyclic chelating agents DOTA-Bn-SCN (177Lu-L8) and DOTAGA (177Lu-L9) with four acetate donor arms provided higher tumor uptake and retention compared to the DOTAMA chelating agents (e.g., 177Lu-L3 or 177Lu-L1) with three acetate arms. These results were further supported by the in vitro data showing an increase in the binding affinity of L8 and L9 compared to L1. Those agents also displayed higher blood plasma protein binding compared to 177Lu-L1 (Supplementary Figure 16) and also in PSMA-expressing normal tissues, including the kidneys, and salivary and lacrimal glands. Third, radioligands with the p-bromo-benzyl moiety showed higher tumor uptake and retention with linear linkers than when they possessed rigid linker (e.g., 177Lu-L1 vs. 177Lu-L11 and 177Lu-L9 vs.177Lu-L10). Also, no significant changes were observed in tumor uptake and retention between the short vs. the long linker (177Lu-L1 vs. 177 Lu-L5). Fourth, attachment of an albumin-binding moiety provided longer tumor retention for 177Lu-L14, most likely by increasing serum half-life as recently reported by others [23–25]. That change was also associated with significantly higher kidney and salivary gland retention compared to the clinical agents 177Lu-PSMA-617 (type II) or 177Lu-PSMA-I&T (type I) and consistent with recent clinical data from a similar class of albumin-binding agent,177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 [41].

Several strategies have been attempted to mitigate off-target toxicity of these low-molecular-weight radioligands, such as renal protection, external cooling of salivary glands and the use of concurrently administered blocking agents [17, 42]. These radioligands are cleared through the kidneys and may be reabsorbed and partially retained in the proximal tubules, causing dose-limiting nephrotoxicity. While renal toxicity has not yet proved a major issue for 177Lu-PSMA-targeted therapy, perhaps due to low reabsorption and retention of the radioligands and long-range, lowlinear energy transfer (LET) radiation of 177Lu (βmax 0.5 MeV, 1.7 mm), a blocking strategy can be utilized to mitigate salivary or lacrimal gland irradiation for PSMA-based α-particle therapy, as seen with 225Ac-PSMA-617 [43]. PSMA-based α-particle therapy can also be fraught with long-term renal toxicity [28]. The self-blocking study that we investigated showed that 177Lu-L1, which already demonstrates relatively low renal uptake as a type II agent, caused no significant change in tumor uptake but yielded a tenfold kidney blockade. Another strategy to decrease off-target effects would be merely to optimize dosing regimen, i.e., amount and frequency, which is being undertaken in certain centers.

In cellulo, the colony-forming assay indicated that efficacy was directly related to cell uptake and internalization. In vivo treatment studies were conducted with larger initial tumor volumes (Supplementary Table 21) compared to similar studies in the recent literature, which used tumor sizes of 10–20 mm3 [23]. Using large tumors could have skewed the results unfavorably due to the presence of central necrosis and more challenging dispersion of the radiotherapeutic through the tumor. Furthermore, the early deaths that we observed in the in vivo studies were not related to the animals being overcome by the tumor, but other causes not overt on autopsy [36]. Our necropsy data, while not demonstrating renal toxicity, showed acute and subacute damage to murine lacrimal glands and testes (seminiferous tubules), indicating that the lacrimal glands could be used as a surrogate organ for these 177LuPSMA agents for preclinical toxicity evaluation. Although most preclinical studies did not report lacrimal gland uptake, an albumin-binding agent, CTT1403, displayed high uptake in the lacrimal glands [23], as anticipated.

Conclusion

We undertook an abbreviated SAR study to optimize urea-based agents for PSMA-targeted, β-particle radiopharmaceutical therapy. While difficult to alter only one variable at a time and perform studies from synthesis through long-term toxicity on all permutations, we believe that we have obtained a few hints to help guide future work. As we expect such agents to be used with increasing frequency and perhaps to maintain patients over many years, careful attention to off-target effects is necessary, although they may not have manifested in the early trials performed to date, e.g., renal toxicity. Our goal was to provide a high-affinity type II agent that was at least equivalent to existing clinical agents with respect to efficacy. Employing a p-bromo-benzyl moiety combined with a relatively short linker between the chelator and targeting moiety produced 177Lu-L1, which likely has the most beneficial combination of structural features of this series, and could justifiably be developed for clinical use. The scaffold on which 177Lu-L1 is based may also provide guidance for the corresponding α-particle emitters, which, although potentially more efficacious, may also be fraught with more imposing adverse side effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. R. Mease for his helpful comments.

Funding We are grateful for the following sources of support: K25 CA148901 and the Patrick C. Walsh Prostate Cancer Research Fund (SRB), CA134675, CA184228, EB024495, and the Commonwealth Foundation (MGP).

Abbreviations

- PC

Prostate cancer

- SAR

Structure–activity relationships

- PSMA

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

- DCIBzL

2-[3-[1Carboxy-5-(4-(125)I-iodo-benzoylamino)-pentyl]-ureido]-pentanedioic acid

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- SPECT

Single-photon emission computed tomography

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest Drs. Banerjee and Pomper are co-inventors on one or more U.S. patents covering compounds discussed in this submission, and as such are entitled to a portion of any licensing fees and royalties generated by this technology. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. No other authors have declared any relevant conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval All animal studies were carried out in compliance with the regulations of the Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kiess AP, Banerjee SR, Mease RC, Rowe SP, Rao A, Foss CA, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen as a target for cancer imaging and therapy. Quarterly J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;59: 241–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haberkorn U, Eder M, Kopka K, Babich JW, Eisenhut M. New strategies in prostate cancer: prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) ligands for diagnosis and therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborne JR, Akhtar NH, Vallabhajosula S, Anand A, Deh K, Tagawa ST. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-based imaging. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:144–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salas Fragomeni RA, Amir T, Sheikhbahaei S, Harvey SC, Javadi MS, Solnes LB, et al. Imaging of nonprostate cancers using PSMA-targeted radiotracers: rationale, current state of the field, and a call to arms. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:871–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang SS, O’Keefe DS, Bacich DJ, Reuter VE, Heston WD, Gaudin PB. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is produced in tumor-associated neovasculature. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2674–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baccala A, Sercia L, Li J, Heston W, Zhou M. Expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen in tumor-associated neovasculature of renal neoplasms. Urology. 2007;70:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spatz S, Tolkach Y, Jung K, Stephan C, Busch J, Ralla B, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of prostate specific membrane antigen expression in the vasculature of renal tumors: implications for imaging studies and prognostic role. J Urol. 2018;199:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver DA, Pellicer I, Fair WR, Heston WD, Cordon-Cardo C. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrkach J, Von Hoff D, Ali MM, Andrianova E, Auer J, Campbell T, et al. Preclinical development and clinical translation of a PSMA-targeted docetaxel nanoparticle with a differentiated pharmacological profile. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:128ra39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterzing F, Kratochwil C, Fiedler H, Katayama S, Habl G, Kopka K, et al. 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT: a new technique with high potential for the radiotherapeutic management of prostate cancer patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowe SP, Macura KJ, Ciarallo A, Mena E, Blackford A, Nadal R, et al. Comparison of prostate-specific membrane antigen–based 18F-DCFBC PET/CT to conventional imaging modalities for detection of hormone-naïve and castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahbar K, Afshar-Oromieh A, Seifert R, Wagner S, Schäfers M, Bögemann M, et al. Diagnostic performance of 18F-PSMA-1007 PET/CT in patients with biochemical recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:2055–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benesova M, Schafer M, Bauder-Wust U, Afshar-Oromieh A, Kratochwil C, Mier W, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a tailormade DOTA-conjugated PSMA inhibitor with optimized linker moiety for imaging and endoradiotherapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:914–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weineisen M, Schottelius M, Simecek J, Baum RP, Yildiz A, Beykan S, et al. 68Ga- and 177Lu-labeled PSMA I&T: optimization of a PSMA-targeted theranostic concept and first proof-of-concept human studies. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fendler WP, Rahbar K, Herrmann K, Kratochwil C, Eiber M. 177Lu-PSMA radioligand therapy for prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zechmann CM, Afshar-Oromieh A, Armor T, Stubbs JB, Mier W, Hadaschik B, et al. Radiation dosimetry and first therapy results with a 124I/131I-labeled small molecule (MIP-1095) targeting PSMA for prostate cancer therapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1280–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langbein T, Chausse G, Baum RP. Salivary gland toxicity of PSMA radioligand therapy: relevance and preventive strategies. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1172–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopka K, Benešová M, Bařinka C, Haberkorn U, Babich J. Glu–ureido-based inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen: lessons learned during the development of a novel class of low-molecular-weight theranostic radiotracers. J Nucl Med. 2017;58: 17S–26S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trover JK, Beckett ML, Wright GL. Detection and characterization of the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) in tissue extracts and body fluids. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:552–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray Banerjee S, Pullambhatla M, Foss CA, Falk A, Byun Y, Nimmagadda S, et al. Effect of chelators on the pharmacokinetics of (99m)Tc-labeled imaging agents for the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). J Med Chem. 2013;56:6108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee SR, Pullambhatla M, Foss CA, Nimmagadda S, Ferdani R, Anderson CJ, et al. 64Cu-labeled inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen for PET imaging of prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2657–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eder M, Schaefer M, Bauder-Wuest U, Hull W-E, Waengler C, Mier W, et al. 68Ga-complex lipophilicity and the targeting property of a urea-based PSMA inhibitor for PET imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:688–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choy CJ, Ling X, Geruntho JJ, Beyer SK, Latoche JD, Langton-Webster B, et al. 177Lu-labeled phosphoramidate-based PSMA inhibitors: the effect of an albumin binder on biodistribution and therapeutic efficacy in prostate tumor-bearing mice. Theranostics. 2017;7:1928–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umbricht CA, Benesova M, Schibli R, Muller C. Preclinical development of novel PSMA-targeting radioligands: modulation of albumin-binding properties to improve prostate cancer therapy. Mol Pharm. 2018;15:2297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly J, Amor-Coarasa A, Ponnala S, Nikolopoulou A, Williams C Jr, Schlyer D, et al. Trifunctional PSMA-targeting constructs for prostate cancer with unprecedented localization to LNCaP tumors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018.2018;45:1841–1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Banerjee SR, Foss CA, Pullambhatla M, Wang Y, Srinivasan S, Hobbs RF, et al. Preclinical evaluation of 86Y-labeled inhibitors of prostate-specific membrane antigen for dosimetry estimates. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:628–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Foss CA, Byun Y, Nimmagadda S, Pullambahatla M, Fox JJ, et al. Radiohalogenated prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-based ureas as imaging agents for prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7933–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiess AP, Minn I, Vaidyanathan G, Hobbs RF, Josefsson A, Shen C, et al. ( 2 S ) - 2 - ( 3 - ( 1 - C a r b o x y - 5 - ( 4 – 2 1 1 A t astatobenzamido)pentyl)ureido)-pentanedioic acid for PSMA-targeted alpha-particle radiopharmaceutical therapy. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1569–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banerjee SR, Pullambhatla M, Byun Y, Nimmagadda S, Foss CA, Green G, et al. Sequential SPECT and optical imaging of experimental models of prostate cancer with a dual modality inhibitor of the prostate-specific membrane antigen. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:9167–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray Banerjee S, Chen Z, Pullambhatla M, Lisok A, Chen J, Mease RC, et al. Preclinical comparative study of 68Ga-labeled DOTA, NOTA, and HBED-CC chelated radiotracers for targeting PSMA. Bioconjug Chem. 2016;27:1447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiess AP, Minn I, Chen Y, Hobbs R, Sgouros G, Mease RC, et al. Auger radiopharmaceutical therapy targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Chatterjee S, Lisok A, Minn I, Pullambhatla M, Wharram B, et al. A PSMA-targeted theranostic agent for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2017;167:111–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fendler WP, Stuparu AD, Evans-Axelsson S, Luckerath K, Wei L, Kim W, et al. Establishing 177Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in a syngeneic model of murine prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2017;58: 1786–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouchet LG, Bolch WE, Blanco HP, Wessels BW, Siegel JA, Rajon DA, et al. MIRD Pamphlet No. 19: absorbed fractions and radionuclide S values for six age-dependent multiregion models of the kidney. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1113–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olszewski RT, Bukhari N, Zhou J, Kozikowski AP, Wroblewski JT, Shamimi-Noori S, et al. NAAG peptidase inhibition reduces locomotor activity and some stereotypes in the PCP model of schizophrenia via group II mGluR. J Neurochem. 2004;89:876–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapter Brayton C. 25 - spontaneous diseases in commonly used mouse strains. In: Fox JG, Davisson MT, Quimby FW, Barthold SW, Newcomer CE, Smith AL, editors. The mouse in biomedical research. second ed. Burlington: Academic; 2007. p. 623–717. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brayton CF, Treuting PM, Ward JM. Pathobiology of aging mice and GEM: background strains and experimental design. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:85–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serfilippi LM, Pallman DR, Russell B. Serum clinical chemistry and hematology reference values in outbred stocks of albino mice from three commonly used vendors and two inbred strains of albino mice. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci. 2003;42:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee SR, Foss CA, Castanares M, Mease RC, Byun Y, Fox JJ, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of technetium-99m- and rhenium-labeled inhibitors of the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). J Med Chem. 2008;51:4504–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray Banerjee S, Pullambhatla M, Foss CA, Falk A, Byun Y, Nimmagadda S, et al. Effect of chelators on the pharmacokinetics of 99mTc-labeled imaging agents for the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). J Med Chem. 2013;56:6108–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zang J, Fan X, Wang H, Liu Q, Wang J, Li H, et al. First-in-human study of 177Lu-EB-PSMA-617 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46:148–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taïeb D, Foletti J-M, Bardiès M, Rocchi P, Hicks RJ, Haberkorn U. PSMA-targeted radionuclide therapy and salivary gland toxicity: why does it matter? J Nucl Med. 2018;59:747–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kratochwil C, Bruchertseifer F, Rathke H, Bronzel M, Apostolidis C, Weichert W, et al. Targeted alpha therapy of mCRPC with 225Actinium-PSMA-617: dosimetry estimate and empirical dose finding. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.