Abstract

Research has documented that loneliness is a major public health concern, particularly for older adults in the United States. However, previous studies have not elucidated the mechanisms that connect family economic adversity to husbands’ and wives’ loneliness in later adulthood. Thus, using prospective dyadic data over 27 years from 254 enduring couples, the present study investigated how spouses’ mastery, as an intra-individual process, and marital functioning, as a couple process, link midlife family economic adversity to spouses’ later-life loneliness. The results provided support for three linking life course pathways: an adversity-mastery-loneliness pathway, an adversity-marital functioning-loneliness pathway, and a mastery-marital functioning-loneliness pathway. The results also showed spousal contemporaneous dependencies in mastery and loneliness. These findings demonstrate the persistent influence of midlife family economic adversity on husbands’ and wives’ loneliness nearly three decades later and elucidate linking mechanisms involving mastery and couple marital functioning. Findings are discussed as they relate to life course and family systems theories. Implications address multiple levels including national- and state-policies and couple-level clinical interventions.

Keywords: midlife, economic stress, mastery, marriage, loneliness, older adults

Previous research has documented that nearly one-fifth of adults in the United States experience loneliness in the second-half of their life (Perissnotto, Cenzer, & Covinsky, 2012). Loneliness is a subjective feeling of isolation, not belonging, or lack of companionship that often increases with age (Dykstra, van Tilburg, & de Jong Gierveld, 2005; Perissnotto et al., 2012). Feelings of loneliness can impair individual wellbeing and are often associated with various physical, psychological, and cognitive problems, such as cardiovascular risk, obesity, physical limitations, depression, low self-esteem, memory decline, and poor sleep as well as increased mortality (de Jong Gierveld, van Tilburg, & Dykstra, 2006; Xia & Li, 2018).

With regard to antecedents of loneliness, research has documented various adverse life experiences as contributors to the development of loneliness in later years (defined as 65 years or more), including socioeconomic status, low income, lack of social integration, strained marital relations, and poor physical health (De Jong Gierveld et al., 2006; Wickrama, O’Neal, Klopack, & Neppl, 2020). However, previous research has not investigated the long-term influence of family economic adversity over the middle years on later-life loneliness for husbands and wives in enduring marriages.

Research suggests that the adversity-loneliness association may be mediated by the depletion of individual psychological resources, such as mastery (Ben-Zur, 2018; Crowe & Butterworth, 2016). Mastery is the perception that events and circumstances are under one’s own personal control rather than the control of external forces (Pearlin, 1989). Consequently, individuals’ perceptions of mastery integrate their past and present (Pearlin, Nguyen, Schieman & Milkie, 2007). Indeed, research has shown that mastery is associated with multiple physical and mental health outcomes (Drewelies et al., 2018). Specific to the variables of interest in the present study, individuals’ mastery has been shown to be adversely influenced by experiences of economic adversity (Crowe & Butterworth, 2016), and mastery has also been shown to alleviate or prevent the development of feelings of loneliness (Ben-Zur, 2018). Thus, mastery may play an important role linking experiences of family economic adversity in the middle years to loneliness in later adulthood (i.e., an adversity-mastery-loneliness pathway). However, we know little about this potential long-term intra-individual mediating processes involving mastery.

In addition, mastery has also been shown to positively contribute to spouses’ marital behaviors. Specifically, previous research has documented that mastery may have a positive influence on couples’ conflict resolution abilities, resulting in better marital functioning (Lee, Wickrama, Futris, & Mancini, 2016; Lee, King, Wickrama, & O’Neal, 2019). In the present study, we consider couples’ constructive conflict resolution as an indicator of positive marital functioning and expect that a lack of mastery may contribute to spouses’ poor conflict resolution and poor marital functioning.

Marital functioning is also important for loneliness as positive marital functioning has been shown to alleviate feelings of loneliness by making close intimate social connections available to both spouses (Ayalon, Shiovitz-Ezra, & Palgi, 2013). Alternatively, poor marital functioning can increase loneliness by limiting the availability of close intimate relationships (Wickrama et al., 2020) as well as through biological mechanisms involving physiological responses to stressful conflictual marital relations (Campagne, 2019). The association between marital functioning and loneliness may be strong for older adults because marital functioning is particularly salient for spouses in long-term, enduring marriages (Cornwell & Waite, 2009; Wickrama et al., 2020). Consequently, in addition to the adversity-mastery-loneliness pathway previously introduced, mastery may influence later-life loneliness of husbands and wives in its own right through its influence on couples’ marital functioning forming a mastery-marital functioning-loneliness pathway. Family economic adversity may also influence later-life loneliness of husbands and wives through its influence on couples’ marital functioning forming an adversity-marital functioning-loneliness pathway.

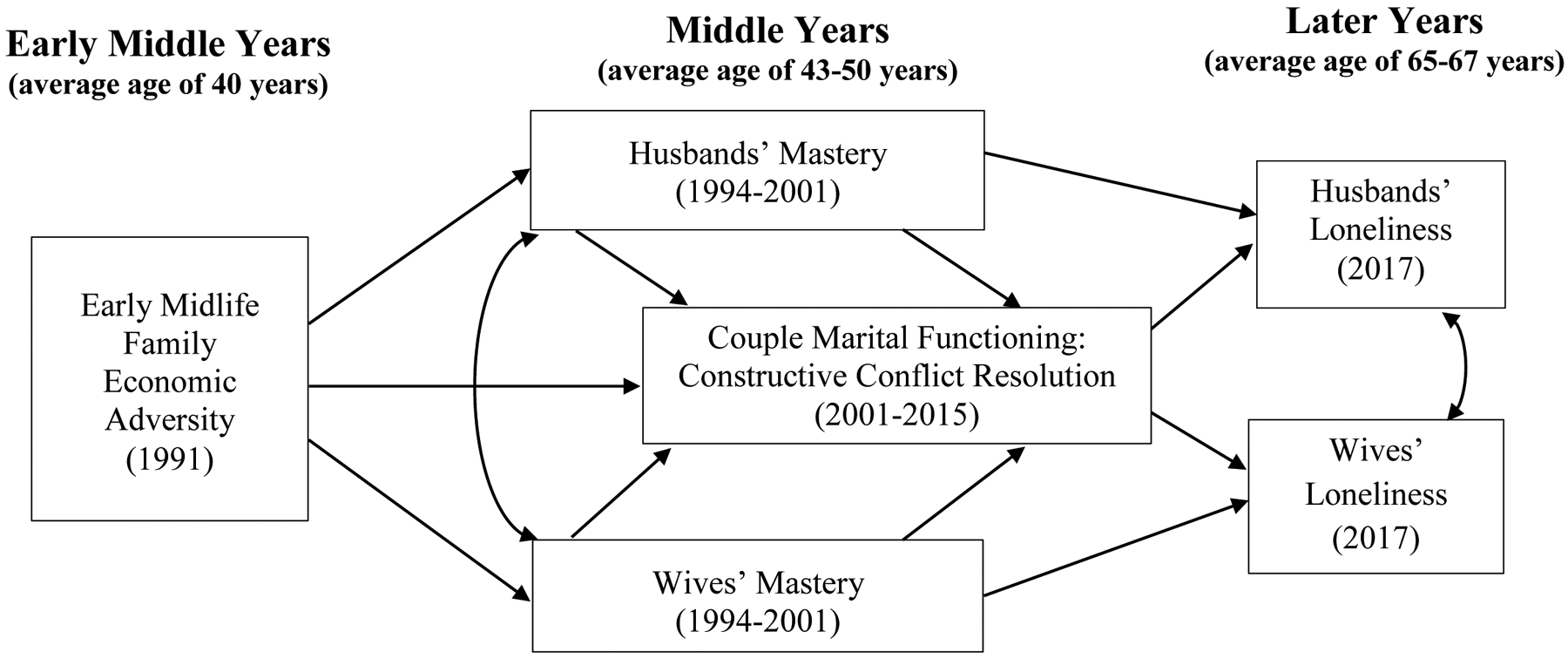

These three pathways, drawn from the previous research, are shown in figure 1 noting mastery as an intra-individual process and marital functioning as a couple process contributing to the influence of midlife family economic adversity on husbands’ and wives loneliness in later adulthood. However, more research is needed to elucidate the complex web of mechanisms linking midlife family economic adversity and later-life loneliness.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework: Intra-individual and marital processes linking enduring couples’ family economic adversity in early middle years to loneliness in later years.

Furthermore, the present study emphasizes life course developmental aspects and dyadic elements of couple aging. Regarding life course development, due to cumulative life experiences, mastery can be malleable over the middle years (Kaniasty, 2006; Wickrama, Surjadi, Lorenz, &Elder, 2008). Research also suggest that, over the mid-later years, positive aspects of marital relationships generally increase, whereas negative aspect decrease (Wickrama et al., 2020). As previously noted, loneliness has been shown to increase with age (Dykstra et al., 2012). Thus, the hypothesized pathways investigate important life course developmental changes over time and associations among these attributes over the middle and later years. Regarding the investigation of dyadic elements of couple aging, consistent with the life course “linked lives,” notion, the relational context influences each spouse’s behaviors, beliefs, and feelings (Elder, 1998). Also consistent with the relational perspective (Berscheid & Ammazzalorso, 2001), individuals function, and their experiences occur, in a context of mutual influences and interactions, forming dependencies between them. These dependencies between spouses, combined with the increased likelihood of biased parameter estimates when conducting separate analyses of husbands and wives (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006), reinforce the need for dyadic analyses of husbands and wives.

The Present Study

Drawing from the life course model (Elder & Giele, 2009) and using prospective data over 27 years with a sample of 254 husbands and wives in enduring marriages, as depicted in figure 1, the present study will investigate a dyadic life course model examining how early midlife family economic adversity influence husbands’ and wives’ later-life loneliness (> 67 years) through intra-individual and couple processes involving mastery and marital functioning across later midlife (average age 40–67 years from 1991–2017). More specifically, the three hypothesized pathways leading to loneliness in the later years address adversity-mastery-loneliness, mastery-marital functioning-loneliness, and adversity-marital functioning-loneliness. These inter-related processes account for spouses’ interdependency and are expected to combine to form a life course dyadic process. Also, consistent with the relational (Berscheid & Ammazzalorso, 2001) and life course (Elder, 1998) perspectives, these pathways consider both individual-level (e.g., mastery) and couple-level (i.e., couple conflict resolution) characteristics as mediators. Thus, this multi-level, interdependent dyadic process (see Figure 1) explains how midlife family adversity exerts a long-term influence on both spouses’ loneliness in later years through the depletion of individual control beliefs and skills and associated couple conflict resolution over their mid-later years. That is, family economic adversity is expected to create a “chain of risks” (Kuh et al., 2003), including the depletion of mastery and conflictual marital functioning in later midlife, impacting later-life loneliness. Importantly, in this life course dyadic process, family economic adversity may operate as a common fate construct (i.e., experiences that are “shared” between spouses) (Ledermann & Kenny, 2012).

Most previous studies of loneliness have not adequately investigated life experiences prospectively over a long period of time. The insufficient follow-up periods have limited the ability of previous research to fully assess possible adverse consequences of family economic adversity on later-life loneliness. The lack of extensive follow-up periods is particularly important given that life-long stressful experiences are thought to have cumulative influences on wellbeing in later adulthood (Lynch, Kaplan, & Shema, 1997). This investigation will enhance our knowledge of the long-term antecedents, and mechanisms connected to the development, of loneliness in later years, and this enhanced knowledge can inform preventive intervention programs targeting middle-aged adults in enduring marriages. The three hypothesized “layered” pathways depicted in figure 1 are discussed in the paragraphs that follow (i.e., pathways of (1) adversity-mastery-loneliness, (2) adversity-marital functioning-loneliness, and (3) mastery-marital functioning-loneliness).

Pathway 1: Family Economic Adversity, Mastery, and Loneliness

As depicted in figure 1, the long-term economic adversity-loneliness association may partly operate through the depletion of individuals’ sense of mastery. Although mastery is considered a personality characteristic, there is evidence that it is malleable depending on life circumstances (Kaniasty, 2006). The hardships and stressors most inimical to mastery are, first, those that are stubbornly persistent despite efforts to avoid or ameliorate them; and, second, those that are located within the most salient areas of life” (Pearlin et al., 2007, p. 166). Because family finances are highly salient for most families, including middle aged parents, and because family economic adversity often continues over an extended period of time, family economic adversity is expected to be strongly associated with a decline in mastery during the middle years (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). Conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2001) also posits that psychological resources, such as mastery, can become depleted as a result of adverse socioeconomic circumstances. The couples in the present sample faced the “farm crisis” of the late 1980s including the continuing low prices of agricultural products as they were entering middle adulthood. The consequences of economic difficulties, as a particularly stressful life experience for these mid-western rural couples, have been repeatedly noted (Conger & Elder, 1994; Lorenz, Conger, Montague, & Wickrama, 1993).

Individuals with a high level of mastery believe in their ability to influence what happens around them and to them, rather than believing they are at the mercy of external forces (Pudrovska, Schieman, Pearlin, & Nguyen, 2005). An important dimension of mastery is contingency (Ben-Zur, 2018); that is, mastery is a link between an individual’s actions and outcomes because mastery includes beliefs about personal control and the ability to affect one’s environment and context through actions in every-day life circumstances. According to this argument, we expect that individuals with high mastery are likely to be more successful at evoking or actively selecting environments that will provide desired social connections. Consequently, high mastery may protect against feelings of loneliness in later years by contributing to the maintenance of social connections in later years (Dykstra et al., 2005; Perissnotto et al., 2012).

Furthermore, connecting these components of mastery to loneliness through coping mechanisms, Lazarus (1999) suggests two primary reasons that explain the influence of mastery on loneliness. First, mastery enables individual to cope effectively with feelings of loneliness and alleviate or regulate these feelings by appraising stress coping capacity and finding and using appropriate cognitive and behavioral stress coping strategies. Second, mastery, through beliefs about personal control, can prevent the generation of feelings of loneliness.

Pathway 2: Family Economic Adversity, Couple Marital Functioning, and Loneliness

As shown in figure 1, family economic adversity is hypothesized to negatively influence couple’s marital functioning. Family economic adversity has psychological consequences for both husbands and wives (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010), and distressed spouses are more likely to be irritable, authoritarian, and rejecting, which can result in less constructive conflict resolution between spouses and, more generally, decreased marital functioning. More specifically, research has shown that higher levels of family economic pressure are associated with higher levels of marital conflict and increased stressful family events (Conger et al., 2002; Lorenz, Elder, Bao, Wickrama, & Conger, 2000; Robila & Krishnakumar, 2005).

Particularly, as previously noted, most of the enduring couples in the present study sample experienced family economic hardship as a result of the rural farm crisis in the late 1980s when they were middle-aged mothers and fathers with adolescent children and aging parents. Although some of these marriages have dissolved in subsequent years, many have continued, and these enduring couples have experienced decades of major life transitions together (e.g., becoming “empty nesters,” work transitions, retirement transitions) with varying levels of marital functioning.

In turn, marital functioning is hypothesized to influence loneliness of both husbands and wives. Consistent with the cognitive perspective of loneliness (de Jong Gierveld et al., 2006), individuals have certain desires and criteria for their social and intimate relationships, and when these expectations are not fulfilled, feelings of loneliness can develop. Thus, loneliness often arises from an individual’s perceived lack of high-quality social connections (Ayalon et al., 2013; de Jong Gierveld et al., 2006; Dykstra et al., 2005; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010).

The marital relationship is generally the most important social connection because it serves as the most intimate psychological, emotional, and physical source of support available to most individuals (Berg, Johnson, Meegan, & Strough, 2003; Hazan & Shaver, 1987). This is consistent with attachment theory, which emphasizes the centrality of intimate relationships in adulthood for staving off loneliness (Bowlby, 1998). In particular, the marital relationship is salient in later years because, as individuals age, they tend to narrow their number of social relationships and place increasing value on the relationships they choose to maintain over time (Levenson, Carstensen, & Gottman, 1994). As individuals approach later life, aging individuals frequently cite their spouse as the primary source of emotional and instrumental support (Cornwell & Waite, 2009). Thus, we expect marital functioning, as measured by conflict resolution, will be an important determinant of loneliness in later years.

Pathway 3: Mastery, Marital Functioning, and Loneliness

As shown in figure 1, the mastery-marital functioning, and loneliness pathway may also lead to loneliness because mastery is a psychological resource that people draw from when responding to day-to-day events and circumstances, including interactions with one’s partner (Alarcon, Bowling, & Khazon, 2013; Lee et al., 2016). Based on existing research, we posit that mastery beliefs, such as contingency, control, and competence, together with the cognitive skills underlying mastery, such as cognitive flexibility, sustained attention, and tolerance (Richards & Hatch, 2011, will contribute to marital conflict resolution and management. That is, greater mastery may enable spouses to engage in active and attentive problem-solving processes that facilitate positive behavioral responses between couple members and, consequently, positive couple interactions. Also, mastery may generate feelings of competency about their ability to cope with relational problems, which can promote more constructive conflict resolution behaviors between marital partners and reduce the occurrence of destructive conflict resolution behaviors (Schneewind & Gerhard, 2002).

Conversely, for individuals with a low level of mastery, their passive beliefs toward life outcomes (i.e., perceptions of a lack of contingency and competence) may lead to less engagement in constructive conflict resolution behaviors. Also, impaired mastery can compromise their energy and ability to manage relationship issues and conflicts and, ultimately, increase marital conflict (Buck & Neff, 2012), contributing to loneliness in later adulthood.

Dependencies between Husbands and Wives

Consistent with the life course linked lives notion (Elder, 1998) and relational perspective (Berscheid & Ammazzalorso, 2001), the daily life activities of spouses in enduring marriages are closely connected, and one spouse’s beliefs and feelings can be transmitted to the other resulting in dependencies (Johnson et al., 2017). For example, if one spouse perceives a deficiency in social connections, this perception can be transmitted to their spouse, resulting in increased congruence in partners’ loneliness (a process termed “love sick”; Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017). Past research has provided evidence for such husband-wife contemporaneous associations with respect to mastery beliefs (Lee et al., 2019) and loneliness (Wickrama et al, 2020). Further, recent research has provided evidence for spouses’ interdependence in relation to the association between spouses’ marital quality and their partners’ loneliness. For example, Hsieh & Hawkley (2018) found that aversion to one’s spouse was associated with increased loneliness among their partners, and Moorman (2016) reported that one partner’s report of positive relationship quality was equally influential for both spouses loneliness. Further, Stokes (2016) revealed that both spouses’ perceptions of positive and negative marital quality were significantly related to husbands’ and wives’ loneliness. Thus, as shown in figure 1, spousal interdependence and contemporaneous associations are taken into account in the current study’s dyadic framework (depicted by curved non-directional paths).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The data used to evaluate these hypotheses are from the Iowa Youth and Family Project (IYFP, 1989–1994), which was later continued as two panel studies: the Midlife Transitions Project (MTP) in 2001) and the Later Adulthood Study (LAS) in 2015 and 2017. Together, these projects provide data over 27 years on rural families from a cluster of eight counties in north-central Iowa that closely mirror the economic diversity of the rural Midwest. The IYFP began as a study of rural couples with children, at least one of whom was a seventh grader in 1989 (Conger & Elder, 1994). The 254 consistently married couples in the present study are those who participated in 1991, 1994, 2001, 2015, and 2017 data collections and were consistently married throughout the study period. Data collected in 1991, rather than 1989, were used as the first time point due to the availability of study variables.

The attrition rate was 31% from 1991 to 2017 in part because we limited the present study sample to husbands and wives who were consistently married from 1991 to 2017 (N=254). An attrition analysis compared the current analytic sample of consistently married dual-earning couples and couples who were excluded from the current analyses due to divorce and study attrition on demographic characteristics (i.e., age, education level, economic hardship measured by counts of economic cutbacks, and divorce proneness (Booth, Johnson, & Edwards, 1983)) and study variables (e.g., mastery) in 1991. The only significant difference noted was for divorce proneness in 1991, with higher scores reported for couples who were excluded from the current analysis.

In 1991, spouses were in their early middle years. The average ages of husbands and wives were 42 and 40 years, respectively, and their ages ranged from 33 to 59 for husbands and 31 to 55 for wives. On average, the couples had been married for 19 years and had three children. The median age of the youngest child was 12. In 1989, the average number of years of education for husbands and wives was 13.68 and 13.54 years, respectively. Because there are very few minorities in the rural area studied, all participating families were White.

Measures

Family Economic Adversity

In 1991, each spouse reported whether they have difficulty paying bills each month (1=no difficulty at all, 5=a great deal of difficulty) and whether they have money left over at the end of the month (1=more than enough money left over, 4=not enough to make ends meet). Almost 15% (14.8%) of the respondents reported that they experienced great difficulty paying bills, and slightly more respondents (18.4%) reported not having enough money to make ends meet. The two items were strongly correlated for husbands and wives (r=.67 for husbands and .62 for wives). Each spouse’s responses were standardized and summed with higher scores indicating greater family economic adversity.

Mastery

In 1994 and 2001, participants responded to four items from Pearlin’s Mastery Scale (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981). Example items include “Sometimes I feel that I am being pushed around in life” and “I have little control over the things that happen to me.” Responses ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Items were averaged, and higher scores indicated greater mastery (α=.78 and .81 in 1994 and .60 and .70 in 2001, for husbands and wives, respectively). In 1994, the correlations for mastery items ranged from .37 to .57 for husbands and from .31 to .52 for wives. In 2001, the correlations for mastery items ranged from .21 to .43 for husbands and from .25 to .55 for wives.

Couple Constructive Conflict Resolution

As an indicator of marital functioning, in 2001 and 2015, six items from the family problem-solving questionnaire (Conger, 1988) were used to ask each partner about their spouse’s behaviors during conflict (e.g., How often does your partner… “listen to your ideas how to solve the problem?” and “show a real interest in helping solve the problem?”). Response options ranged from 1 (always) to 7 (never). Averaged scores were computed for husbands and wives, and then spouses’ reports were averaged to create a couple constructive conflict resolution with higher scores reflecting more frequent constructive conflict resolution (α=.82 to .92 across spouses and measurement occasions).

Loneliness

Husbands and wives completed the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Frguson, 1978) in 2017. The 20-item scale was designed to measure subjective feelings of loneliness as well as feelings of social isolation. The measure included items such as: “You lack companionship,” “There is no one you can turn to,” and “You are no longer close to anyone.” Participants rated each item on a 4-point scale (1=never; 4=often), and items were averaged. The scale’s internal consistency for husbands and wives was .80 and .90, respectively.

Statistical Analyses

Using husbands’ and wives’ reports in 1991, a latent construct was estimated to capture family economic adversity (i.e., a common fate construct). Because the three hypothesized pathways were nested within the larger model, a series of incremental structural equation models (SEMs) were estimated. The covariance between two loneliness constructs in Model 1 was fixed based on the observed covariance in Model 2 to enable model identification. The final model (i.e., Model 3) included analyses to test family economic adversity in 1991, husbands’ and wives’ mastery in 1994 and 2001, couples’ constructive conflict resolution in 2001 and 2015 as predictors of spouses’ loneliness outcomes in 2017. The final model also included husbands’ and wives’ age and physical health in 1994, along with family economic adversity in 2001, as control variables explaining variation in later-life loneliness. For these control variables, non-significant paths were removed from the final model to enhance model parsimony. We also tested a fully recursive model as an alternate to the hypothesized model by freeing all of the fixed paths between the study constructs in Model 3. All models were tested using Mplus, version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018).

Out of the sample of 254 couples, some cases were unavailable for a specific wave of data collection (nearly 9% of the data). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was utilized to test the hypotheses with all available data. A range of fit indices were used to evaluate the model fit including the chi-square statistic, Cumulative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). For the chi-square fit statistic, the model is thought to fit the data well when the chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom is below 3.0 (Carmines, McIver, Bohrnstedt, & Borgatta, 1981). CFI values near or greater than .95 and RMSEA values close to or less than .06 suggests that the model fits the data well (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The TLI, similar to the CFI, is an incremental fit index that assess the improvement in the fit of a model over a baseline model, with values near or greater than .95 suggesting the model fits the data well (Kline, 2011). The statistical significance of indirect effects linking family economic adversity in early midlife to loneliness in later adulthood was assessed using bootstrapping (with 5,000 draws) (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This method uses a resampling strategy in order to avoid the assumption of multivariate normality.

Results

The descriptive statistics for study variables are shown in Table 1. The first model, identifying the association between family economic adversity in couples’ early middle years (1991) and both spouses loneliness in later adulthood (2017) , indicated family economic adversity (measured as a common fate construct comprised of husbands’ and wives’ reports) was implicated in greater later-life loneliness for husbands and wives (unstandardized coefficients are reported; Husbands: B=.09, p<.01; Wives: B=.08, p<.05) (see panel A of figure 2).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. H. economic adversity (91) | — | |||||||||||||||

| 2. W. economic adversity (91) | .70*** | — | ||||||||||||||

| 3. H. mastery (94) | −.29*** | −.41*** | — | |||||||||||||

| 4. W. mastery (94) | −.29*** | −.15** | .20*** | — | ||||||||||||

| 5. H. mastery (01) | −.13* | −.25*** | .52*** | .08 | — | |||||||||||

| 6. W. mastery (01) | −.16** | −.10 | .16** | .52*** | .14* | — | ||||||||||

| 7. Couples’ CCR (01) | −.15* | −.11 | .18** | .23*** | .18** | .22*** | — | |||||||||

| 8. Couples’ CCR (15) | −.15* | −.13* | .19** | .28*** | .19** | .23*** | .63*** | — | ||||||||

| 9. H. loneliness (17) | .17* | .06 | −.02 | −.37*** | −.06 | −.42*** | −.31*** | −.36*** | — | |||||||

| 10. W. loneliness (17) | .22** | .20** | −.32*** | −.22** | .32*** | −.12 | .25*** | −.30*** | .27*** | — | ||||||

| 11. H. physical health (94) | −.16** | −.22*** | .26*** | .07 | .28*** | .09 | .08 | .08 | .04 | −.22** | — | |||||

| 12. W. physical health (94) | −.21*** | .17*** | .04 | −33*** | .08 | .22*** | .06 | .19** | −.31*** | −.12 | .08 | — | ||||

| 13. H. economic adversity (01) | .41*** | .45*** | −.24*** | −.16** | −.28*** | −.13* | .10 | −.14* | .10 | .22** | −.27*** | −.16** | — | |||

| 14. W. economic adversity (01) | .56*** | .38*** | −.21*** | −.31*** | −.16** | −.24*** | −.13* | −.09 | .15* | .19** | −.10 | .27*** | .64*** | — | ||

| 15. H. age (91) | .01 | .01 | −.04 | −.03 | −.06 | −.03 | .01 | −.07 | −.08 | .09 | −.10 | .06 | .01 | .06 | — | |

| 16. W. age (91) | −.03 | −.05 | −.04 | −.06 | .06 | −.04 | .03 | −.06 | −.11 | .01 | −.11* | .07 | −.01 | −.01 | .80*** | — |

| M | .00 | −.09 | 3.78 | 3.76 | 3.82 | 3.79 | 10.21 | 10.73 | 1.70 | 1.64 | 3.55 | 3.50 | −.03 | −.07 | 41.72 | 39.70 |

| SD | .87 | .86 | .51 | .59 | .53 | .56 | 1.50 | 1.60 | .50 | .51 | .75 | .77 | .81 | .83 | 4.89 | 4.12 |

Notes. Years are indicated in parentheses. H.=Husbands. W.=Wives. CCR=Constructive conflict resolution. M=Mean; SD=Standard deviation. Pairwise deletion was implemented.

p < .05 (two-tailed).

p < .01 (two-tailed).

p < .001 (two-tailed).

Figure 2.

The direct influence of family economic adversity on loneliness as mediated by mastery.

Notes. F. Econ Adversity = Family Economic Adversity. H. = Husbands. W. = Wives. Unstandardized coefficients are shown.

The second model (see panel B of figure 2) incorporated mastery at two time points in their middle years (1994 and 2001) as a mechanism linking family economic adversity and husbands’ and wives’ loneliness. Compared to couples experiencing less economic adversity, when couples experienced more family economic adversity in their early middle years (1991), both spouses averaged lower levels of mastery in 1994 (B=−.29 and −.20, p<.001 for husbands and wives, respectively). In turn, significant intra-individual rank-order continuity was indicated for husbands and wives’ mastery from 1994 to 2001 (B=.53 and .47, p<.001, respectively). Individuals’ mastery at both measurement occasions in their middle years (1994 and 2001) had a unique influence on their loneliness in later adulthood (2017) with individuals averaging less mastery when they reported a higher level of mastery (for husbands and wives, respectively: 1994 B=−.16 and −.15, p<.05; 2001 B=−.14, p<.05 and −.30, p<.001). In comparing Model 1 and Model 2 (panels A and B in Figure 2), after incorporating mastery, family economic adversity in the early middle years was no longer directly associated with loneliness in later adulthood (B=.07 and .02, p>.05 for husbands and wives, respectively).

In the third, and final, model (see Figure 3), measures of couples’ constructive conflict resolution in later middle years (2001) and later adulthood (2015) were added to Model 2. Most of the paths from Model 2 were unchanged. More specifically, family economic adversity in 1991 continued to negatively influence husbands’ and wives’ mastery in 1994 (B=−.36 and −.32, p<.001, respectively). In turn, for husbands and wives, there was a high degree of stability in mastery from 1994 to 2001 (B=.58 and .57, p<.001), and those with greater mastery in 2001 reported less loneliness in later adulthood (2017) (B=−.21, p<.01 and −.29, p<.001 for husbands and wives, respectively). However, the significant association between mastery in 1994 and loneliness in later adulthood was no longer statistically significant (B=.10 and .06, p>.05 for husbands and wives, respectively). Instead, husbands’ and wives’ mastery in 1994 was positively associated with couples constructive conflict resolution in 2001 (B=.40 and .47, p<.05, respectively). Family economic adversity in early middle years (1991) was also influential for couples constructive conflict resolution (2001) (B=−.28, p<.05). In turn, conflict resolution in 2001 explained couples’ conflict resolution in 2015 (B=.63, p<.001), and when couples reported more constructive conflict resolution in 2015, their members generally reported less subsequent loneliness (2017) (B=−.06 and −.25, p<.001 for husbands and wives, respectively). Husbands’ and wives’ perceptions of loneliness in later adulthood were significantly associated (r=.20, p<.01), and their reports of mastery were correlated in 1994 (r=.05, p>.05, respectively).

Figure 3.

Linking family economic adversity in early middle years to loneliness in later years through mastery and constructive conflict resolution (Model 3).

Notes. F. Econ Adversity = Family Economic Adversity. H. = Husbands. W. = Wives. CCR=Couples’ constructive conflict resolution. Unstandardized coefficients are shown. Only statistically significant paths and correlations are shown. Three control variables are not shown (family economic adversity in 2001 and spouses’ age). Family economic adversity in 2001 had a significant effect on husbands’ loneliness (B=.10, p<.05). The effects of age on dependent variables were not significant. χ2(82)=104.02. CFI=.97. TLI=.96. RMSEA=.04.

Variables capturing family economic adversity in later middle years (2001), couple members’ physical health in 1994, and age were also incorporated in Model 3 (see figure 3) as control variables. There was statistically significant rank-order continuity in family economic adversity from early to later middle years (B=.64, p<.001), and family economic adversity in later mid-life was associated with greater loneliness for husbands (B=.10, p<.05) but not wives (B=.04, p>.05). Regarding health, family economic adversity in early midlife was detrimental for husbands’ and wives’ physical health in 1994 (B=−.14, p<.05 and −.19, p<.01), and husbands and wives with poorer health in their middle years generally reported more later-life loneliness (B=−.09, p<.05 and −.12, p<.01). Reports of later-life loneliness did not vary significantly by age. Model 3 explained 19.7% of the variation in husbands’ later-life loneliness and slightly more variation (27.4%) in wives’ later-life loneliness.

Five statistically significant indirect effects were found in Model 3. Two of the indirect effects supported the adversity-mastery-loneliness pathway. More specifically, family economic adversity in early middle years (1991) was indirectly linked to both husbands’ and wives’ later-life loneliness (2017) through their mastery in 1994 and 2001 (coefficient=.03, p<.05 and .03, p<.01, respectively). Two additional indirect effects supported the adversity-marital functioning-loneliness pathway. Early socioeconomic adversity (1991) was indirectly implicated in both husbands’ and wives’ later-life loneliness (2017) through their constructive conflict resolution in 2015 (coefficient=.02, p<.05 and .03, p<.01, respectively). Last, for both husbands and wives, the comprehensive indirect effect (adversity 1991 → mastery 1994 → couples constructive conflict resolution 2001 → couples constructive conflict resolution 2015 → loneliness 2017) was statistically significant but small in magnitude (coefficient=.00, p<.01).

Discussion

Previous research has documented that older adults’ loneliness is a major public health concern in the United States (Perissnotto et al., 2012) because loneliness is associated with multiple health problems in later years as well as increased mortality (de Jong Gierveld et al., 2006). Although previous studies have shown that various socioeconomic adversities and proximal factors, such as impaired individual resources and poor relational experiences, contribute to the development of loneliness in later years, fewer studies have elucidated the mechanisms that connect family adversity, such as economic hardship, to husbands’ and wives’ loneness in later adulthood. Thus, using prospective dyadic data over 27 years from husbands and wives in enduring marriages, the present study investigated how mastery, as an intra-individual process, and couples’ marital functioning, as measured by their constructive conflict resolution, link midlife family economic adversity to later-life loneliness. Drawing from the life course model (Elder & Giele, 2009; Kuh et al., 2003), three related pathways were hypothesized: (1) adversity-mastery-loneliness, (2) adversity-marital functioning-loneliness, and (3) mastery-marital functioning-loneliness.

The results provided empirical support for the intra-individual adversity-mastery-loneliness pathway. Although research has largely considered mastery to be a stable personality characteristic, other research notes that spouses’ mastery can be malleable and dependent on family circumstances (Kaniasty, 2006). Particularly, it appears that, for both husbands and wives, family economic adversity can deplete their sense of mastery. This finding is consistent with the expectation that personal resources are vulnerable to adverse life circumstances, particularly for the most salient life domains, such as family finances (Pearlin et al., 2007). The results also showed that, for both spouses, mastery in midlife is associated with lower levels of loneliness in later adulthood. The positive effects of mastery are consistent with the cognitive perspective (Lazarus, 1999), which suggests that mastery reduces the likelihood that feelings of loneliness will develop (perhaps through continued social connections) and also enables individuals to cope effectively with loneliness, should they develop. Thus, mastery can be a potent individual resource for older adults given that it connects past experiences to present loneliness (Pearlin et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the results of the incremental, nested SEMs showed that mastery in the middle years uniquely influenced husbands’ and wives’ loneliness, indicating an intra-individual processes. Given that the results indicated a chain effect, with mastery measured at two measurement occasions in their middle years (when spouses averaged in their early 40s and mid-50s), it is important to consider the differential effects of early mastery and later mastery. Mastery in the early middle years was implicated in higher quality marital process during the middle years, which, in turn, influenced loneliness whereas later mastery was not implicated in subsequent marital processes. Thus, mastery seems to be more important for marital processes in the early middle years than later years. However, it would be incorrect to conclude that later mastery is unimportant, given that later mastery was associated with loneliness. Moreover, later mastery (when individuals were in their mid-50s on average) may contribute to later wellbeing through more proximal mechanisms (e.g., coping). These findings highlight the need for investigations of age-graded mastery that take a “long view” to identify the various mechanisms linking mastery to individual wellbeing across the life course.

The results also provided evidence for a mastery-marital functioning-loneliness pathway. More specifically, spouses’ early midlife mastery (1994) positively influenced couple’s marital functioning (2001), but later mastery (2001) did not influence subsequent marital functioning (2015). It appears that spouses who possess a high level of mastery in early midlife are successful in managing their earlier levels of marital disagreements and conflicts. As previously discussed, marital conflict resolution and management is essential for positive marital functioning. Mastery may provide the necessary energy, competence, and control, and even the underlying cognitive skills, such as attention and tolerance, that are necessary for effectively navigating day-to-day life circumstances (Alarcon et al., 2013). Conversely, life adversities can deplete mastery, resulting in spouses’ poor conflict resolution and, in turn, conflictual marital relations. This process is particularly relevant for the present study population who experienced family economic adversity in the wake of the farm crisis when they were middle-aged mothers and fathers (Conger et al., 2002).

The results also supported the existence of an adversity-marital functioning-loneliness pathway. It appears that, in addition to mastery, the influence of economic adversity on loneliness also operates indirectly through marital functioning. This mediation effect is somewhat consistent with the family stress model (Conger et al., 2002), which posits that the influence of family economic adversity on marital relationships operates indirectly through spouses’ psychological distress. Future research should investigate the competing (or additive) mediating roles of positive psychological resources, such as mastery, and negative psychological states, such as depressive symptoms, in relation to family economic adversity and marital functioning. As expected, the results provided evidence for the influence of marital functioning on the loneliness of both spouses. That is, both mastery and marital functioning uniquely influenced spouses’ loneliness. These findings are consistent with systems theory (Cox & Paley, 1997), which contends that both individual-level and family-level characteristics influence the wellbeing of individuals comprising the family system.

The dyadic analytical framework utilized in the study provided an opportunity to consider (a) common fate factors (Ledermann & Kenny, 2012) and (b) spousal dependencies (Kenny et al., 2006) within a single analytical framework. First, family economic adversity was examined as a common fate factor, and it was influential for couple’s marital functioning and for both spouses sense of mastery. The couple-level construct of economic adversity captures the common variance, or shared experience, of husbands and wives economic adversity. The observed significant associations between this couple-level construct and individual attributes would not have been evident in individual-level, spouse-specific analyses.

Second, consistent with the life course model (Elder & Giele, 2009) and the relational perspective (Berscheid & Ammazzalorso, 2001), individuals function, and their experiences occur, in a context of mutual influences and interactions, which forms spousal dependencies. Accordingly, the results demonstrated that husbands’ and wives’ mastery feelings are contemporaneously associated providing evidence of their dependency. More importantly, these associations remained statistically significant even after taking the common influence of family economic adversity on both spouses’ mastery into account, which is evidence that the spousal dependency in mastery in not spurious due to experiences of economic hardship. Moreover, taking spousal dependencies into account when testing the hypothesized associations limits biased parameter estimates. Furthermore, although the analyses did not reveal traditional “partner effects” between spouses (e.g., husbands’ mastery influencing wives’ loneliness), partner effects may exist through the contemporaneous spousal associations of mastery. For example, husbands’ mastery may influences wives’ loneliness through the association between husbands’ and wives’ mastery.

There are limitations to the present study that should be noted. First, all measures were assessed using spouses’ subjective reports. However, in some instances, such as the economic adversity items, the measures captured concrete behaviors (i.e., can’t pay bills at the end of each month, having no remaining money at the end of each month). Future studies can improve on this research by using objective measures of family economic adversity (e.g., tax returns) and observational measures of conflict resolution. Second, the present investigation examined only direct and indirect influences between economic adversity, mastery, and marital functioning on loneliness in later life. Future studies should investigate how loneliness is affected by multiplicative influences between these constructs (i.e., moderation). The third limitation relates to the generalizability of the results. The sample was comprised only of European-American individuals that lived in rural Iowa during the farm crisis of the 1980s. Although the farm crisis provided the opportunity to research relatively widespread family economic adversity, future studies testing similar models with a more diverse population are needed. For instance, future samples should include multiple ethnicities, greater variation in the length of marriage, and other geographic locations. Finally, the present study limited its investigation to family economic adversity and couples’ marital functioning, but other life course stressors warrant investigation, such as stressful work and poor parent-child relations, as they may also have long-term influence on loneliness.

These findings provide support for the value and necessity of national- and state-level policies aimed at improving families’ economic conditions given that they underscore the long-term effects of financial stress over multiple decades and the web of effects generated, including effects on mastery, constructive conflict resolution, and loneliness among others. Together the sizeable body of research suggests that eliminating or minimizing families’ economic adversity is a point of intervention and policy change that can result in notable improvements in families’ well-being for decades to come. Specific to the current study population, these findings note the value of interventions and policy changes that can reduce economic adversity in early midlife, as individuals at this life stage are often parents sandwiched between responsibilities of caring for children and parents, which may make them uniquely vulnerable to economic adversity. These considerations are also important for mental health professionals and counselors as these findings serve as a reminder not to overlook family economic adversity as a potential cause of negative feelings, such as loneliness, in later adulthood.

Beyond economic adversity, the study findings also emphasize the preserving and strengthening of individual resources, such mastery, and improving marital functioning as ways to protect older adults from the development of loneliness and its physical and psychological consequences. Although mastery is sometimes conceptualized as a relatively stable personal trait, these findings (and others), indicate its’ malleability over the life course. Because mastery in early midlife was implicated in subsequent marital processes, mastery is also important for intervention and prevention efforts targeting both loneliness and couple relationships. Interestingly, because mastery was related to marital processes in the middle years, but not later life, the findings highlight considerations for when and what type of interventions are most likely to be successful. That is, for interventions targeting marital processes, efforts to increase mastery are likely to be more effective in the early middle years, but for interventions targeting loneliness, increased mastery may be beneficial later in life as well. Moreover, bolstering mastery and marital functioning may “break” the chain of risks that implicates previous adverse experiences, including economic adversity, with subsequent loneliness.

Acknowledgment

This research is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG043599, Kandauda A. S. Wickrama, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573, HD064687), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Contributor Information

Kandauda Wickrama, Department of Human Development and Family Science, The University of Georgia, 107 Family Science Center I (House A), Athens, GA 30602

Catherine Walker O’Neal, Department of Human Development and Family Science, The University of Georgia, 107 Family Science Center II (House D), Athens, GA 30602.

References

- Alarcon GM, Bowling NA, & Khazon S (2013). Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(7), 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon L, Shiovitz-Ezra S, & Palgi Y (2013). Associations of loneliness in older married men and women. Aging and Mental Health, 17(1), 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur H (2018). The Association of mastery with loneliness: An integrative review. Journal of Individual Differences, 39, 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Johnson MM, Meegan SP, & Strough J (2003). Collaborative problem-solving interactions in young and old married couples. Discourse Processes, 35(1), 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, & Ammazzalorso H (2001). Emotional experience in close relationships. In Fletcher GJ & Clark MS (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal process (pp. 308–330). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Johnson D, & Edwards NJ (1983). Measuring marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment New York: Basic Books. (Original work published 1969). [Google Scholar]

- Buck AA, & Neff LA (2012). Stress spillover in early marriage: The role of self-regulatory depletion. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(5), 698–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagne DM (2019). Stress and perceived social isolation (loneliness). Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 82, 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmines EG, & McIver JP (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In Bohmstedt GW & Borgatta EF (Eds.), Social measurement (pp. 65–115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD (1988). Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP). Washington, DC: National Institute of Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, & Martin MJ (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, & Elder GH Jr (1994). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. Social institutions and social change Aldine de Gruyter, Hawthorne, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, & Waite LJ (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe L, & Butterworth P (2016). The role of financial hardship, mastery and social support in the association between employment status and depression: Results from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open, 6(5), e009834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T, & Dykstra PA (2006). Loneliness and social isolation. In Vangelisti A & Perlman D (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 485–500). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drewelies J, Chopik WJ, Hoppmann CA, Smith J, & Gerstorf D (2018). Linked lives: Dyadic associations of mastery beliefs with health (behavior) and health (behavior) change among older partners. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 73(5), 787–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra PA, Van Tilburg TG, & de Jong Gierveld J (2005). Changes in adult loneliness. Research on Aging, 27, 725–747. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69(1), 1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder G & Giele J (Eds.). (2009). The craft of life course research. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, & Cacioppo JT (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, & Shaver P (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, & Shirom A (2001). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In Golembiewski RT (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (p. 57–80). Marcel Dekker. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh N, & Hawkley L (2018). Loneliness in the older adult marriage: Associations with dyadic aversion, indifference, and ambivalence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(10), 1319–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, Galambos NL, Finn C, Neyer FJ, & Horne RM (2017). Pathways between self-esteem and depression in couples. Developmental Psychology, 53(4), 787–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K (2006). Sense of mastery as a moderator of longer-term effects of disaster impact on psychological distress. In Strelau J &Klonowicz T (Eds.), People under extreme stress (pp. 131–147).Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). The analysis of dyadic data. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, & Wilson SJ (2017). Lovesick: How couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 421–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2011). Methodology in the Social Sciences. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, & Power C (2003). Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(10), 778–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, &Weaver SL (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. London, UK: Free Association Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann T, & Kenny DA (2012). The common fate model for dyadic data: Variations of a theoretically important but underutilized model. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(1), 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, King V, Wickrama KAS, & O’Neal CW (2019). Psychological resources, constructive conflict management behaviors, and depressive symptoms: A dyadic analysis. Family Process. 10.1111/famp.12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Wickrama KAS, Futris TG, & Mancini JA (2017). Linking work control to depressive symptoms through intrapersonal and marital processes. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1626–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RW, Carstensen LL, & Gottman JM (1994). Influence of age and gender on affect, physiology, and their interrelations: A study of long-term marriages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Elder GH Jr, Bao WN, Wickrama KA, & Conger RD (2000). After farming: Emotional health trajectories of farm, nonfarm, and displaced farm couples. Rural Sociology, 65(1), 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, & Shema SJ (1997). Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(26), 1889–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Montague RB, & Wickrama KAS (1993). Economic conditions, spouse support, and psychological distress of rural husbands and wives. Rural Sociology, 58(2), 247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman SM (2016). Dyadic perspectives on marital quality and loneliness in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(5), 600–618. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2018). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, & Mullan JT (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Nguyen KB, Schieman S, & Milkie MA (2007). The life-course origins of mastery among older people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(2), 164–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto CM, Cenzer IS, & Covinsky KE (2012). Loneliness in older persons: A predictor of functional decline and death. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudrovska T, Schieman S, Pearlin LI, & Nguyen K (2005). The sense of mastery as a mediator and moderator in the association between economic hardship and health in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 17(5), 634–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, & Hatch SL (2011). A life course approach to the development of mental skills. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B(Supplement 1), i26–i35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robila M, & Krishnakumar A (2005). Effects of economic pressure on marital conflict in Romania. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 246–251. 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, & Ferguson ML (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneewind KA, & Gerhard AK (2002). Relationship personality, conflict resolution, and marital satisfaction in the first 5 years of marriage. Family Relations, 51(1), 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JE (2017). Marital quality and loneliness in later life: A dyadic analysis of older married couples in Ireland. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(1), 114–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KA, O’Neal CW, Klopack ET, & Neppl TK (2020). Life course trajectories of negative and positive marital experiences and loneliness in later years: Exploring differential associations. Family Process, 59(1), 142–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Surjadi FF, Lorenz FO, & Elder GH Jr (2008). The influence of work control trajectories on men’s mental and physical health during the middle years: Mediational role of personal control. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(3), S135–S145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia N, & Li H (2018). Loneliness, social isolation, and cardiovascular health. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 28(9), 837–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]