Abstract

Purpose

Obesity, measured by body mass index (BMI), is implicated in adverse pregnancy outcomes for women seeking in vitro fertilization (IVF) care. However, the shape of the dose-response relationship between BMI and IVF outcomes remains unclear.

Methods

We therefore conducted a dose-response meta-analysis using a random effects model to estimate summary relative risk (RR) for clinical pregnancy (CPR), live birth (LBR), and miscarriage risk (MR) after IVF.

Results

A total of 18 cohort-based studies involving 975,889 cycles were included. For each 5-unit increase in BMI, the summary RR was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.94–0.97) for CPR, 0.93 (95% CI: 0.92-0.95) for LBR, and 1.09 (95% CI: 1.05-1.12) for MR. There was evidence of a non-linear association between BMI and CPR (Pnon-linearity < 10−5) with CPR decreasing sharply among obese women (BMI > 30). Non-linear dose-response meta-analysis showed a relatively flat curve over a broad range of BMI from 16 to 30 for LBR (Pnon-linearity = 0.0009). In addition, we observed a J-shaped association between BMI and MR (Pnon-linearity = 0.006) with the lowest miscarriage risk observed with a BMI of 22–25.

Conclusions

In conclusion, obesity contributed to increased risk of adverse IVF outcomes in a non-linear dose-response manner. More prospective trials in evaluating the effect of body weight control are necessary.

Keywords: Body mass index, Dose-response, In vitro fertilization, Outcomes

Introduction

Obesity is a serious health issue for both developed and developing countries, affecting more than one billion adults [1]. Women of reproductive age are not invulnerable; 25% of reproductive-aged women in the USA and Europe are overweight (body mass index [BMI] 25.00–29.99 kg/m2), and 23% approximately are obese (BMI ≥ 30.00 kg/m2) [2–4]. Accumulated evidence has shown that excess adiposity contributes to unfavorable obstetric outcomes, including higher risk of miscarriage, preterm birth, fetal deaths, and pregnancy complications [5–7].

Recent studies exploring adverse effects of obesity on endocrine system [8], anovulation [9], and oocyte quality [10] have brought attention toward women with elevated BMIs seeking in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. However, the impact of elevated BMI on IVF outcomes remains somewhat controversial. Early data suggested a lack of association between BMI and IVF outcomes [11–13], but two recent meta-analyses concluded that elevated BMI was associated with higher miscarriage rates, reduced pregnancy, and live birth rates [14, 15]. These studies were based on unadjusted estimates though female age, embryo transfer strategy (fresh and frozen embryo transfer protocols), and PCOS are well-established confounding factors for IVF outcomes. It is therefore possible that the detected effect of BMI was really an effect of these confounders. Extrapolating from these studies is limited by the fact that BMI was categorized as overweight, normal, or obesity groups in their analyses. The exact shape of the dose-response relationship between BMI and IVF outcomes has not been clearly defined. Thus, it is not clear whether there are any threshold effects between BMI and adverse IVF outcomes, and clarifying this would be of major importance for public health implications and improved guidelines to manage risk factors. We therefore conducted a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort-based studies that investigated the association between BMI and clinical pregnancy rates (CPR), live birth rates (LBR), and miscarriage rates (MR) following IVF.

Materials and methods

Identification and eligibility of relevant studies

To identify studies addressing IVF outcomes and BMI, an extensive literature search from 1988 up to March 2020 was conducted from PubMed, ISI Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The search term included keywords relevant to BMI (e.g., “body mass index,” “overweight,” “obesity,” “underweight”) in combination with words related to IVF (e.g., “In vitro fertilization,” “Intracytoplasmic sperm injection,” “ICSI,” “controlled ovarian stimulation,” “ART,” “assisted reproduction technologies”). No language restriction was used, and retrieved articles were screened based on title and abstract, before evaluating the full text. The references of included studies were scrutinized and hand-searched for additional eligible studies. Case reports, non-human study, editorials, and review articles were not considered. The present study was conducted based on theprincipal of PRISMA guidelines [16].

Eligible studies were required to meet the following criteria: (1) cohort-based study evaluated the association between BMI and IVF outcomes; (2) original articles reported independent data; (3) reported number of case and control for 3 or more BMI categories; (4) reported adjusted relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each BMI category or sufficient information for effect size calculation. Studies with fewer than three BMI categories, raw data without adjustment, overlapping samples, insufficient data, and in vitro maturation cycle were excluded.

Data extraction

The outcomes of interest were clinical pregnancy rates, live birth rates, and miscarriage rates. Information with regard to authorship, publication year, country, study design, numbers of patients or cycles, BMI, oocytes source (autologous or donor), embryo transfer strategy (fresh or frozen), variables adjusted for in the multivariable analysis, and RR estimates with corresponding 95% CIs was summarized. Data extraction from included studies was performed independently by two reviewers.

Statistical analysis

The method proposed by Greenland and Longnecker [17] and Orsini [18] was used for the dose-response analysis. For BMI level-specific RRs from each study, the midpoint of the upper and lower boundary for each BMI category was assigned to the corresponding RR estimate. For the lowest or highest category, open-ended category was assumed to have the same amplitude as that of the adjacent interval. A restricted cubic spline model with three knots (10, 50, and 90% percentiles) was used to estimate a potential curve linear association between BMI and IVF outcomes. The P value for non-linearity was calculated by a likelihood ratio test [19]. The study-specific relative risks and variances were pooled using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects model [20] to calculate the summary RR and 95% CI for a 5-unit increment in BMI. Subgroup analyses were stratified by embryo transfer strategy and source of oocytes. Cochran’s Q test and I2 index were calculated to explore heterogeneity across studies [21]. Egger’s tests and Begg’s tests were used to identify potential publication bias [22]. Type I error rate was set at 0.05 for two-sided analysis. All statistical analyses were done using the STATA software (Version 12.0).

Results

Study characteristics

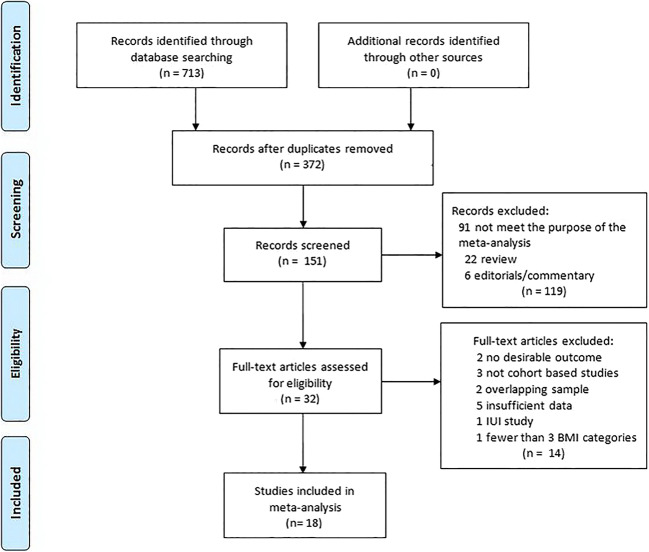

The results of the search process and study selection are summarized in Fig. 1. Eighteen cohort-based studies involving 975,889 cycles were finally included [3, 5, 10, 23–37]. Nine of these studies included only fresh embryo transfers, and 3 studies included only frozen embryo transfers. Six studies reported only autologous cycles, and 2 studies reported only donor cycles. Six studies recruited women undergoing their first cycles. Of the included studies, only 5 articles reported race/ethnicity. Characteristics of the included studies were shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author | Year | Country | Outcomes | Study design | Sample size (cycle/women) | Oocytes source | Embryo transfer strategy | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang | 2000 | Australia | Clinical pregnancy | Retrospective cohort | 8822/3586 | NA | NA | NA |

| Insogna | 2017 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, ongoing pregnancy | Retrospective cohort | 461/461 | Autologous and donor | First frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer | Cycle cancellation, incomplete cycle information |

| Schliep | 2015 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, live birth | Prospective cohort | 721/721 | Autologous | First fresh embryo transfer | Nonobstructive azoospermia men |

| Cai | 2017 | China | Clinical pregnancy, abortion, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 4798/4401 | Autologous | Fresh embryo transfer | Patients on mild stimulation cycles, natural cycles, and luteal-phase stimulation cycles were excluded from the study. We also excluded patients with diagnoses of diabetes, glucose intolerance, and thyroid abnormality. |

| Oliveira | 2018 | Brazil | Clinical pregnancy, abortion, live birth | Prospective cohort | 3740/NA | Autologous | Fresh embryo transfer | Abnormal karyotype, uterine defects, evidence of hydrosalpinx, infections, endocrine problems, coagulation defects or thrombophilia, and autoimmune defects. |

| Christensen | 2016 | Denmark | Clinical pregnancy | Historical cohort | 5342/NA | Autologous | Fresh embryo transfer | Women were excluded if they were receiving other types of treatment, for example, insemination or had missing information on either BMI and/or treatment type. Women were excluded due to ovulation before oocyte retrieval |

| Provost | 2016 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, pregnancy loss, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 239127/NA | autologous | fresh embryo transfer | patients with height < 48 inches and weight < 70 pounds were excluded |

| Provost | 2016 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, pregnancy loss, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 22317/22317 | Donor | Fresh embryo transfer | Patients with height < 48 inches and weight < 70 pounds were excluded. |

| Zhang | 2019 | China | Clinical pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage | Retrospective cohort | 22043/22043 | Autologous and donor | First frozen-thawed embryo transfer | Patients older than 40 years of age; a history of recurrent miscarriage (defined as ≥ 2 previous biochemical/ clinical losses); previous IVF attempts regardless of a prior fresh or frozen embryo transfer; the presence of submucosal fibroids or polyps, intramural fibroids > 4 cm, hydrosalpinx, and congenital uterine malformation as determined by three-dimensional ultrasound and hysterosalpingography. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, or thyroid dysfunction were also excluded. |

| Luke | 2011 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 45163/NA | Autologous and donor | Fresh and frozen embryo transfer | NA |

| Bailey | 2014 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 101/79 | Autologous and donor | Fresh embryo transfer | In vitro maturation, FSH greater than 10 mIU/mL, uncontrolled thyroid disease as defined by thyroid-stimulating hormone of 5.7 mIU/L or greater based on our laboratory cutoff for an abnormal value, a history of chemotherapy or radiation exposure, a recurrent pregnancy loss, uterine factor, balanced translocation (in either partner), surgically documented endometriosis or pelvic adhesions, a history of pelvic inflammatory disease, adenomyosis, and sub-mucosal myoma. |

| Bellver | 2013 | Spain | Clinical pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage | Retrospective cohort | 9587/9587 | Donor | Fresh and frozen embryo transfer | Recipients with uterine pathologic conditions or a clinical history of recurrent miscarriage were excluded |

| MacKenna | 2017 | Chile | Clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 107313/107313 | Autologous | Fresh embryo transfer | NA |

| Chueca | 2010 | Spain | Clinical pregnancy, miscarriage | Retrospective cohort | 5719/NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang | 2002 | Australia | Abortion | Retrospective cohort | 2349/2349 | NA | NA | NA |

| Sarais | 2016 | Italy | Live birth, miscarriage, ongoing clinical pregnancy | Retrospective cohort | 1602/1602 | Autologous | First fresh embryo transfer | NA |

| Kawwass | 2016 | USA | Clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 494097/NA | Autologous | Fresh embryo transfer | Donor and frozen cycles are excluded |

| Qiu | 2019 | China | Clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth | Retrospective cohort | 2587/2587 | Autologous | first frozen Embryo transfer | Serious and unstable disease, such as cerebrovascular, liver, or kidney diseases; gynecological border-line and malignant tumors (ovarian tumor, endometrial tumor, and cervical cancer); other metabolic disorders (diabetes or adrenal cortex hyperfunction); chromosomal abnormalities; or congenital uterine malformations. |

NA not available

Dose-response meta-analysis

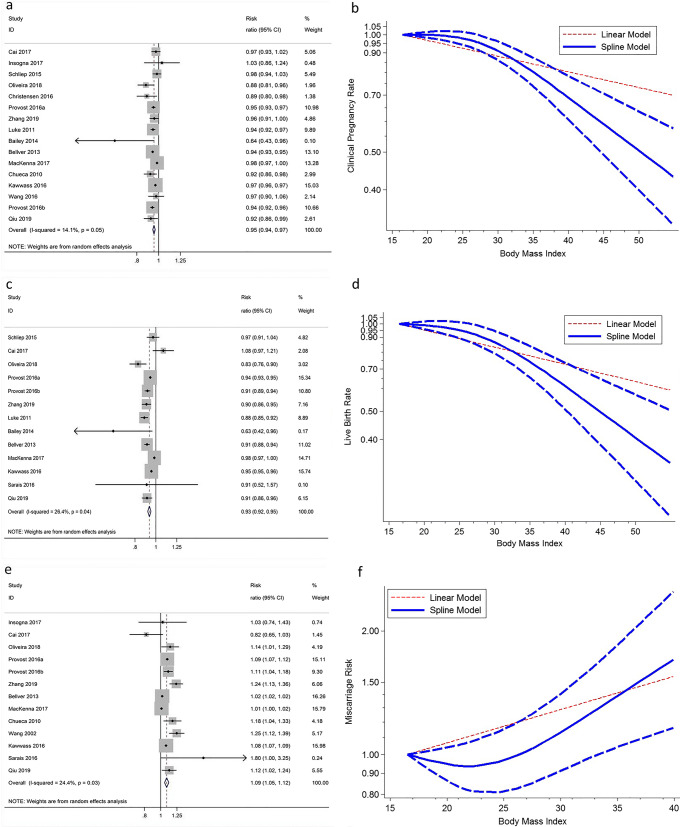

Sixteen studies were included in the analysis of BMI and CPR involving 586,630 cycles. The overall RR for a 5-unit increment in BMI was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.94–0.97, P < 10−5; Fig. 2a) without significant between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 14.1%, P = 0.05). The summary RR was similar when stratified by embryo transfer strategy and source of oocytes (Table 2). The statistical results did not show publication bias (Egger’s test, P = 0.05; Begg’s test, P = 0.47). There was evidence of a non-linear association between BMI and CPR, Pnon-linearity < 10−5 (Fig. 2b). The shape of the dose-response curve was steeper and there was evidence of a sharply decreased CPR among obese women (BMI > 30).

Fig. 2.

Non-linear dose-response analysis and linear trend (per 5 BMI units) of BMI in relation to clinical pregnancy (a, b), live birth (c, d) and miscarriage (e, f) of IVF. Short-dashed blue lines represent 95% confidence intervals

Table 2.

Summary RRs and 95% CIs for a 5-unit increment in BMI and IVF outcomes

| Sub-group analysis | Clinical pregnancy | Live birth | Miscarriage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of data sets | RR (95% CI) | P | No. of data sets | RR (95% CI) | P | No. of data sets | RR (95% CI) | P | |

| Overall | 16 | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | <10−5 | 13 | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) | <10−5 | 13 | 1.09 (1.05–1.12) | <10−5 |

| Embryo transfer strategy | |||||||||

| Fresh | 9 | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | <10−5 | 9 | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | <10−5 | 7 | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | <10−5 |

| Frozen | 3 | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | 0.09 | 2 | 0.91 (0.87–0.94) | <10−5 | 3 | 1.17 (1.08–1.27) | 0.002 |

| Source of oocytes | |||||||||

| Autologous | 8 | 0.96 (0.95–0.98) | <10−5 | 8 | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | <10−5 | 7 | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | 0.003 |

| Donor | 2 | 0.94 (0.93–0.95) | <10−5 | 2 | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | <10−5 | 2 | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 0.18 |

Thirteen studies were included in the analysis of BMI with LBR and included 740,839 cycles. The summary RR for a 5-unit increment in BMI was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.92–0.95, P < 10−5; I2 = 26.4%, Pheterogeneity = 0.04; Fig. 2c). Further stratified according to embryo transfer strategy and source of oocytes, the summary RR was comparable to the overall analysis (Table 2). The Egger test (P = 0.11) and the Begg test (P = 0.90) did not show evidence of publication bias. We did not find evidence suggesting any linear relation between BMI and LBR, Pnon-linearity = 0.0009. Non-linear dose-response meta-analysis showed a relatively flat curve over a broad range of BMI from 16 to 30, with a suggestion of lower LBR associated with higher BMI where data are more sparse and CIs wider (Fig. 2d) and where studies had higher proportions of PCOS patients.

Thirteen studies were included in the analysis of BMI and MR involving 235,167 cycles. The summary RR for miscarriage was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.05–1.12, P < 10−5) per 5-unit increment in BMI (Fig. 2e). There was no strong evidence of heterogeneity among included studies (I2 = 24.4%, P = 0.03). In the subgroup analyses by embryo transfer strategy and source of oocytes, significant associations sustained (Table 2). The dose-response curve for the association was non-linear (Pnon-linearity = 0.006), and there was a J-shaped association between BMI and miscarriage risk. The lowest miscarriage risk was observed with a BMI of 22-25 (Fig. 2f), suggesting increased miscarriage risk for women being underweight or overweight/obese. We found no evidence of small study effects (P > 0.05).

To assess the influence of the individual dataset to the pooled RRs, one single study included in the meta-analysis was deleted each time, and the corresponding pooled RRs were not qualitatively altered.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to explore a potential non-linear association of female BMI and IVF outcomes. Each 5-unit increase in female BMI was related to a statistically significant decrease in risk by 5% and 7% for CPR and LBR, respectively. We also found a 9% increase in the relative risk of miscarriage per 5 units increase in BMI. Although there was evidence of a non-linear association between BMI and clinical pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rate, the non-linearity appeared to be due to a relatively flat curve over a broad range of BMI for CPR and LBR, and a J-shaped curve for MR.

Our results on LBR are in agreement with the previous meta-analysis by Sermondade et al. [15]. In light of our results, the negative relationship between obesity and LBR can be due to synergetic effect of lower CPR and higher MR: the former being direct and the latter making it worse. Therefore, examining the two IVF outcomes separately, as we did in the present study, should provide a better understanding of the underlying relationships between BMI and IVF outcomes. In addition, a non-linear association is observed in the overall analysis with increased risk of adverse IVF outcomes above a BMI of 30 but most pronounced above a BMI of 35. Thus, our results provide further support for previous recommendations to be within the normal range of BMI but also suggest that the detrimental effects of morbidly obese on IVF outcomes should be counseled to women seeking pregnancy with the technique.

Though age, embryo transfer strategy, number of embryos transferred, and PCOS are established risk factors for IVF outcomes, in our analysis all included studies adjusted for BMI, suggesting an association independent of BMI. The biological mechanism by which excess adiposity affects the risk of these outcomes may involve oocyte and embryo quality, ovarian folliculogenesis, impaired uterine environment, embryonic development, metabolic alterations, and interaction between these factors [38–41]. For instance, some studies have demonstrated an increase in euploid miscarriage in obese women [42], suggesting a key role of endometrial factors in the poorer IVF outcomes among obese women. Other researchers did not find increased rates of aneuploidy with increasing BMI [43], suggesting that poor oocyte “quality” in obese patients may be due to factors more complex than chromosomal competence. Though a threshold at around a BMI of 22–25 for miscarriage rate was observed in the present study, detailed mechanism underlying relationships between obesity and IVF outcomes remain unclear.

In the subgroup analyses based on embryo transfer strategy, a pooled analysis of 2 studies found a non-significant reduction in the relative risk of clinical pregnancy undergoing frozen-thawed blastocysts transfers (FET). As suggested by prior studies, using FETs which allows for transfer of embryos into a more physiologic uterine environment may help maximize chances of IVF success [44]. However, most of published studies include fresh cycle, with very few data available on FET to explore the influence of BMI on reproductive outcomes. Though no significant association was detected for MR in donor oocyte cycles, this finding may be attributed to various factors including endometrial effect and differences in baseline [45]. Thus, these differences should not be considered clinically significant. The subgroup analysis was based on studies with limited information available; thus, the result must be interpreted with caution.

Bariatric surgery was suggested as a better way to improve the results of IVF treatment in obese infertile women [46]. However, two recent randomized controlled trials of lifestyle intervention failed to find any favorable effect of short period of weight loss on pregnancy or LBR improvement following IVF [47, 48]. For women undergoing IVF, the problem is the conflict with time. The time it takes to achieve weight loss may not be useful to counter the issues of diminishing ovarian reserve. These results based on different weight loss strategies in obese infertile women highlight the need for more prospective trials with better adherence and longer period of intervention to design the optimal treatment. Therefore, it is difficult to set a BMI threshold exactly going to change clinical care when patients are not typically able to achieve weight loss before starting treatment. Also some clinics refuse to treat women with BMI over 40. Our results clearly emphasize the importance of counseling underweight or obese infertile women before IVF, as cumulative evidences suggest potential long-term effect of abnormal weight on mothers and offspring.

The present meta-analysis has several strengths. Firstly, only cohort-base studies were included and thus recall and selection bias are limited. Secondly, the large sample size allowed us to establish a most comprehensive view of the associations between BMI with different types of IVF outcomes, including clinical pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage. As like any other meta-analysis, limitations also inevitably existed in the present study. As data on different ethnic population is currently limited, future prospective studies including a wider spectrum of subjects are needed, particularly because current publications suggest significant racial/ethnic disparities in IVF outcomes [49]. In addition, a meta-analysis based on observational studies is not able to solve the problem of residual confounders.

In conclusion, findings from this dose-response meta-analysis provide further evidence for the adverse effects of obesity on IVF outcomes. These results suggest that obesity may become one preventable cause of adverse outcomes following IVF, and further work in evaluating the effect of body weight control is necessary.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Gitte Lindved Petersen and Dr. Veronica Sarais for making their data available for the present study.

Data availability

Data analyzed in this study are openly available at locations cited in the reference section.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, Margono C, Mullany EC, Biryukov S, Abbafati C, Abera SF, Abraham JP, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Achoki T, AlBuhairan FS, Alemu ZA, Alfonso R, Ali MK, Ali R, Guzman NA, Ammar W, Anwari P, Banerjee A, Barquera S, Basu S, Bennett DA, Bhutta Z, Blore J, Cabral N, Nonato IC, Chang JC, Chowdhury R, Courville KJ, Criqui MH, Cundiff DK, Dabhadkar KC, Dandona L, Davis A, Dayama A, Dharmaratne SD, Ding EL, Durrani AM, Esteghamati A, Farzadfar F, Fay DFJ, Feigin VL, Flaxman A, Forouzanfar MH, Goto A, Green MA, Gupta R, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hankey GJ, Harewood HC, Havmoeller R, Hay S, Hernandez L, Husseini A, Idrisov BT, Ikeda N, Islami F, Jahangir E, Jassal SK, Jee SH, Jeffreys M, Jonas JB, Kabagambe EK, Khalifa SEAH, Kengne AP, Khader YS, Khang YH, Kim D, Kimokoti RW, Kinge JM, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Kwan G, Lai T, Leinsalu M, Li Y, Liang X, Liu S, Logroscino G, Lotufo PA, Lu Y, Ma J, Mainoo NK, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Mokdad AH, Moschandreas J, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Nand D, Narayan KMV, Nelson EL, Neuhouser ML, Nisar MI, Ohkubo T, Oti SO, Pedroza A, Prabhakaran D, Roy N, Sampson U, Seo H, Sepanlou SG, Shibuya K, Shiri R, Shiue I, Singh GM, Singh JA, Skirbekk V, Stapelberg NJC, Sturua L, Sykes BL, Tobias M, Tran BX, Trasande L, Toyoshima H, van de Vijver S, Vasankari TJ, Veerman JL, Velasquez-Melendez G, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Vos T, Wang C, Wang XR, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wright JL, Yang YC, Yatsuya H, Yoon J, Yoon SJ, Zhao Y, Zhou M, Zhu S, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Gakidou E. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vahratian A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:268–273. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarais V, Pagliardini L, Rebonato G, Papaleo E, Candiani M, Vigano P. A comprehensive analysis of body mass index effect on in vitro fertilization outcomes. Nutrients. 2016;8:109. doi: 10.3390/nu8030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legler J, Fletcher T, Govarts E, Porta M, Blumberg B, Heindel JJ, et al. Obesity, diabetes, and associated costs of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the European Union. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):1278–1288. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawwass JF, Kulkarni AD, Hipp HS, Crawford S, Kissin DM, Jamieson DJ. Extremities of body mass index and their association with pregnancy outcomes in women undergoing in vitro fertilization in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1742–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koning AMH, Kuchenbecker WKH, Groen H, Hoek A, Land JA, Khan KS, Mol BWJ. Economic consequences of overweight and obesity in infertility: a framework for evaluating the costs and outcomes of fertility care. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:246–254. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nohr EA, Bech BH, Davies MJ, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Prepregnancy obesity and fetal death. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:250–259. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172422.81496.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aladashvili-Chikvaidze N, Kristesashvili J, Gegechkori M. Types of reproductive disorders in underweight and overweight young females and correlations of respective hormonal changes with BMI. Iran J Reprod Med. 2015;13:135–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jungheim ES, Travieso JL, Hopeman MM. Weighing the impact of obesity on female reproductive function and fertility. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:3–8. doi: 10.1111/nure.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luke B, Brown MB, Stern JE, Missmer SA, Fujimoto VY, Leach R, A SART Writing Group Female obesity adversely affects assisted reproductive technology (ART) pregnancy and live birth rates. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:245–252. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maheshwari A, Stofberg L, Bhattacharya S. Effect of overweight and obesity on assisted reproductive technology—a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2007;13:433–444. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmm017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Styne-Gross A, Elkind-Hirsch K, Scott RT. Obesity does not impact implantation rates or pregnancy outcome in women attempting conception through oocyte donation. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1629–1634. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dechaud H, Anahory T, Reyftmann L, Loup V, Hamamah S, Hedon B. Obesity does not adversely affect results in patients who are undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;127:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rittenberg V, Seshadri S, Sunkara SK, Sobaleva S, Oteng-Ntim E, El-Toukhy T. Effect of body mass index on IVF treatment outcome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:421–439. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sermondade N, Huberlant S, Bourhis-Lefebvre V, Arbo E, Gallot V, Colombani M, Fréour T. Female obesity is negatively associated with live birth rate following IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25(4):439–451. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata J. 2006;6:40–57. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Dietary magnesium intake and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:362–366. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.022376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bailey AP, Hawkins LK, Missmer SA, Correia KF, Yanushpolsky EH. Effect of body mass index on in vitro fertilization outcomes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:163–e1-e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellver J, Pellicer A, García-Velasco JA, Ballesteros A, Remohí J, Meseguer M. Obesity reduces uterine receptivity: clinical experience from 9,587 first cycles of ovum donation with normal weight donors. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cai J, Liu L, Zhang J, Qiu H, Jiang X, Li P, et al. Low body mass index compromises live birth rate in fresh transfer in vitro fertilization cycles: a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:422–429.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen MW, Ingerslev HJ, Degn B, Kesmodel US, et al. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chueca A, Devesa M, Tur R, Mancini F, Buxaderas R, Barri PN. Should BMI limit patient access to IVF? Hum Reprod. 2010;25(Supplement 1):i283.

- 28.Insogna IG, Lee MS, Reimers RM, Toth TL. Neutral effect of body mass index on implantation rate after frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:770-776.e1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.MacKenna A, Schwarze JE, Crosby JA, Zegers-Hochschild F. Outcome of assisted reproductive technology in overweight and obese women. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2017;21:79–83. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20170020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oliveira JB, Dieamant F, Baruffi R, Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Vagnini LD, Renzi A, Petersen B, Mattila MC, Comar VA, Zamara C, Franco JG., Jr Female body mass index (BMI) influences art outcomes: an evaluation of 3740 IVF/ICSI cycles. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:e120–e121. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Provost MP, Acharya KS, Acharya CR, Yeh JS, Steward RG, Eaton JL, Goldfarb JM, Muasher SJ Pregnancy outcomes decline with increasing body mass index: analysis of 239,127 fresh autologous in vitro fertilization cycles from the 2008 – 2010 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology registry. Fertil Steril. 2016a;105: 663-669, Pregnancy outcomes decline with increasing body mass index: analysis of 239,127 fresh autologous in vitro fertilization cycles from the 2008–2010 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology registry. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Provost MP, Acharya KS, Acharya CR, Yeh JS, Steward RG, Eaton JL, Goldfarb JM, Muasher SJ Pregnancy outcomes decline with increasing recipient body mass index: an analysis of 22,317 fresh donor/recipient cycles from the 2008 – 2010 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System registry. Fertil Steril. 2016b;105:364-368, Pregnancy outcomes decline with increasing recipient body mass index: an analysis of 22,317 fresh donor/recipient cycles from the 2008–2010 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome Reporting System registry. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Schliep KC, Mumford SL, Ahrens KA, Hotaling JM, Carrell DT, Link M, Hinkle SN, Kissell K, Porucznik CA, Hammoud AO. Effect of male and female body mass index on pregnancy and live birth success after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JX, Davies M, Norman RJ. Body mass and probability of pregnancy during assisted reproduction treatment: retrospective study. BMJ. 2000;321:1320–1321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7272.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang JX, Davies MJ, Norman RJ. Obesity increases the risk of spontaneous abortion during infertility treatment. Obes Res. 2002;10:551–554. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Liu H, Mao X, Chen Q, Fan Y, Xiao Y, Wang Y, Kuang Y. Effect of body mass index on pregnancy outcomes in a freeze-all policy: an analysis of 22,043 first autologous frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles in China. BMC Med. 2019;17:114. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1354-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu MT, Tao Y, Kuang YP, Wang Y. Effect of body mass index on pregnancy outcomes with the freeze-all strategy in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1172–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catteau A, Caillon H, Barrière P, Denis MG, Masson D, Fréour T. Leptin and its potential interest in assisted reproduction cycles. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22:320–341. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broughton DE, Moley KH. Obesity and female infertility: potential mediators of obesity’ s impact. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:840–847. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldman KN, Hodes-Wertz B, McCulloh DH, Flom JD, Grifo JA. Association of body mass index with embryonic aneuploidy. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:744–748. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comstock IA, Kim S, Behr B, Lathi RB. Increased body mass index negatively impacts blastocyst formation rate in normal responders undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:1299–1304. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0515-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boots CE, Bernardi LA, Stephenson MD. Frequency of euploid miscarriage is increased in obese women with recurrent early pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldman KN, Hodes-wertz B, Mcculloh DH, Flom JD. Association of body mass index with embryonic aneuploidy. Fertil Steril. 2013;15:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Chambers GM, Zegers-Hochschild F, Mansour R, Ishihara O, Banker M, Dyer S. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology: world report on assisted reproductive technology, 2011. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(6):1067–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polotsky AJ, Hailpern SM, Skurnick JH, Lo JC, Sternfeld B, Santoro N. Association of adolescent obesity and lifetime nulliparity—the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2004–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milone M, Sosa Fernandez LM, Sosa Fernandez LV, Manigrasso M, Elmore U, De Palma GD, et al. Does bariatric surgery improve assisted reproductive technology outcomes in obese infertile women? Obes Surg. 2017;27:2106–2112. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mutsaerts MA, van Oers AM, Groen H, Burggraaff JM, Kuchenbecker WK, Perquin DA, et al. Randomized trial of a lifestyle program in obese infertile women. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1942–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Einarsson S, Bergh C, Friberg B, Pinborg A, Klajnbard A, Karlström PO, Kluge L, Larsson I, Loft A, Mikkelsen-Englund AL, Stenlöf K, Wistrand A, Thurin-Kjellberg A. Weight reduction intervention for obese infertile women prior to IVF: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1621–1630. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wellons MF, Fujimoto VY, Baker VL, Barrington DS, Broomfield D, Catherino WH, Richard-Davis G, Ryan M, Thornton K, Armstrong AY. Race matters: a systematic review of racial/ethnic disparity in Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology reported outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:406–409. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data analyzed in this study are openly available at locations cited in the reference section.