Abstract

The 90 kDa heat shock protein (Hsp90) is a molecular chaperone that processes nascent polypeptides into their biologically active conformations. Many of these proteins contribute to the progression of cancer, and consequently, inhibition of the Hsp90 protein folding machinery represents an innovative approach toward cancer chemotherapy. However, clinical trials with Hsp90 N-terminal inhibitors have encountered deleterious side effects and toxicities, which appear to result from the pan-inhibition of all four Hsp90 isoforms. Therefore, the development of isoform-selective Hsp90 inhibitors is sought to delineate the pathological role played by each isoform. Herein, we describe a structure-based approach that was used to design the first Hsp90α-selective inhibitors, which exhibit > 50-fold selectivity versus other Hsp90 isoforms.

Keywords: Hsp90 alpha, structure-based drug design, isoform selectivity, drug discovery

Molecular chaperones are a class of proteins that regulate proteostasis by assisting in the conformational maturation of nascent polypeptides (referred to as client proteins) and the renaturation of denatured proteins. The heat shock proteins (Hsps) belong to a ubiquitously expressed molecular chaperone family that is highly conserved in eukaryotes. In fact, the 90kDa Heat shock protein (Hsp90) is one of the most abundant Hsps and is highly upregulated in stressed cells, including cancer.[1,2] As a molecular chaperone, Hsp90 is responsible for the conformational maturation of more than 300 client protein substrates, many of which are key regulators of oncogenic transformation, growth, and metastasis.[3–6] As a result, Hsp90 has been widely sought after as a cancer target, which resulted in the development of 18 inhibitors that underwent clinical evaluation.[7,8] Unfortunately, the clinical approval of these inhibitors was hindered due to detrimental activities that are likely to result from the inhibition of all four Hsp90 isoforms (pan-inhibitors). The four Hsp90 isoforms include cytosolic isoforms Hsp90α (inducible) and Hsp90β (constitutively expressed); the endoplasmic reticulum residing glucose regulated protein 94 (Grp94); and the mitochondrial isoform, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated protein 1 (Trap1). [1,2] Pan-inhibition of all four isoforms leads to non-specific degradation of the entire Hsp90-dependent substrate population, and ultimately leads to undesired activities.[4,9] The development of Hsp90 isoform-selective compounds can provide a tool to dissect the role played by each isoform towards disease pathology and toxicities associated with pan Hsp90 inhibition.

Despite high structural similarity between the constitutively expressed isoform, Hsp90β, and the inducible isoform, Hsp90α, each of these isoforms fold select client proteins.[10] Genetic knockdown of Hsp90α results in the degradation of oncogenic client proteins, suggesting that the administration of an Hsp90α-selective inhibitor could exhibit anti-cancer activity against Hsp90α-dependent cancers.[11] In addition to its presence in the cytosol, Hsp90α is also secreted extracellularly to promote wound healing, cell adhesion, and inflammation.[12] In fact, significant levels of Hsp90α are secreted from highly invasive cancers to activate matrix metalloprotease 2 (MMP-2) to induce expression of MMP-3, which drives tumor invasion.[13,14]

Extracellular Hsp90α also contributes to an inflammatory microenvironment that supports prostate cancer progression.[14] Analysis of gene ontology traits revealed Hsp90β to interact with a larger subset of proteins than Hsp90α.[15] Notably, Hsp90α-dependent processes contribute to stress adaptation or other specialized functions, while Hsp90β is important for maintaining cell viability, clearly highlighting the distinct evolution of each isoform.[15–17]

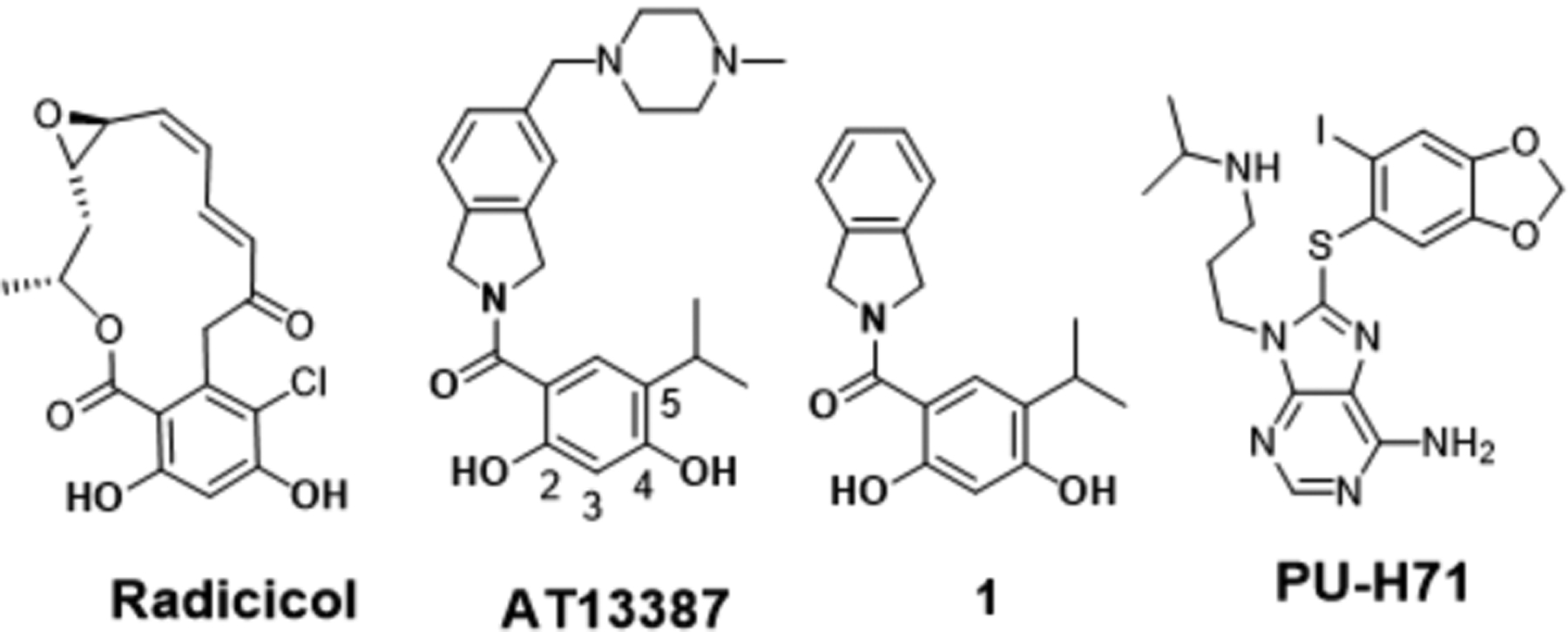

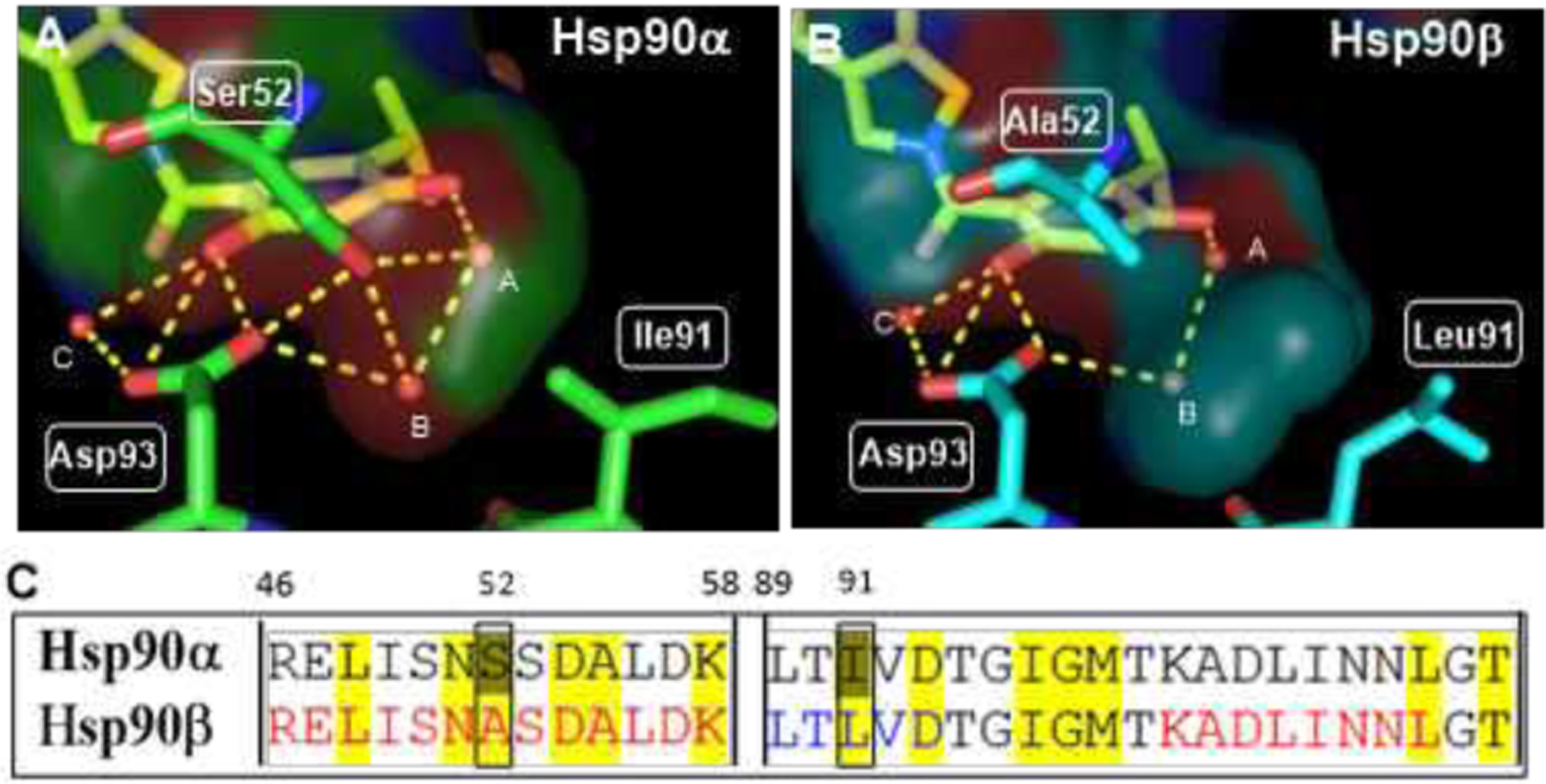

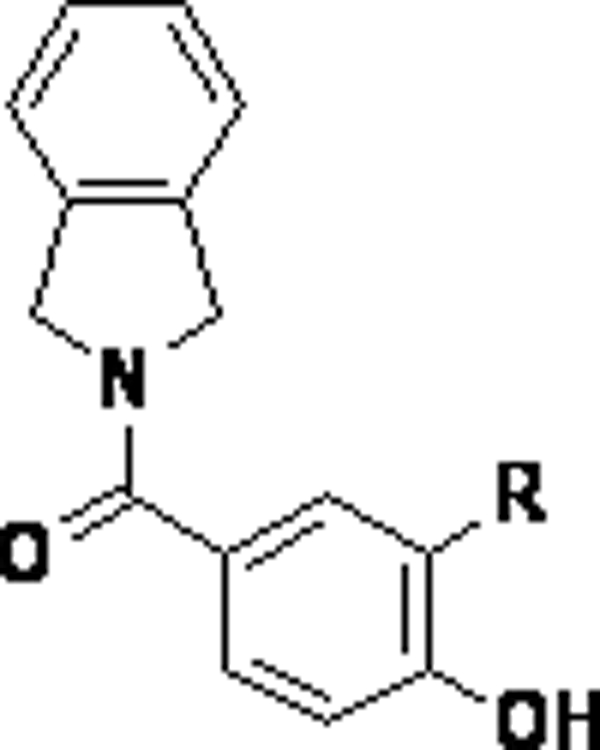

Initial efforts to develop isoform-selective inhibitors focused on Grp94, due to its distinguishing structural features that easily differentiate it from the other Hsp90 isoforms.[18–20] However, the design of isoform-selective inhibitors against the cytosolic isoforms, Hsp90α and Hsp90β, has been extremely challenging as these isoforms share >95% identity within the N-terminal ATP- binding sites. In fact, only two amino acids differ between these nucleotide-binding sites. Despite these challenges, we recently disclosed KUNB 31 as the first Hsp90β-selective inhibitor. [21] However, an isoform selective inhibitor of Hsp90α has not yet been reported. Upon analysis of the Hsp90 α and β N-terminal ATP- binding sites bound to radicicol (Figure 1), it was determined that the resorcinol moiety interacts uniquely with each Hsp90 isoform. Compound 1 was chosen as lead molecule because it represents an analog of AT13387, which is a resorcinol-derived Hsp90 pan-inhibitor that underwent clinical evaluation.[2] Computational studies with 1 bound to the N-terminal ATP-binding site of Hsp90α (PDB: 2XAB) and Hsp90β (PDB:1UYM) revealed the presence of an extensive hydrogen-bond network that is coordinated by three conserved water molecules (labeled as A-C, Figure 2). However, the presence of Ser52 and Ile91 in Hsp90α in lieu of Ala52 and Leu91 in Hsp90β results in formation of a smaller hydrophilic pocket in Hsp90α and a large hydrophobic subpocket in Hsp90β. The subtle difference between these two binding sites were exploited to develop KUNB31, but unfortunately, the presence of a smaller pocket in Hsp90α prevents such investigation. Thus, Ser52/Ala52 represents the only amino acid difference that can be utilized to develop Hsp90α–selective inhibitors (Figure 2). Since compound 1 manifested equipotent binding affinity towards both Hsp90α and Hsp90β when evaluated in a fluorescence polarization (FP) assay (SI, Figure 3S), it served as a starting point for the development of Hsp90α-selective inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Structures of radicicol, AT13387, compound 1 and PU-H71

Figure 2.

Resorcinol pharmacophore of compound 1 and its interactions with N-terminal ATP binding site in A) Hsp90α and B) Hsp90β C) Amino acid sequence alignment of N-terminal ATP-binding site (details in SI).

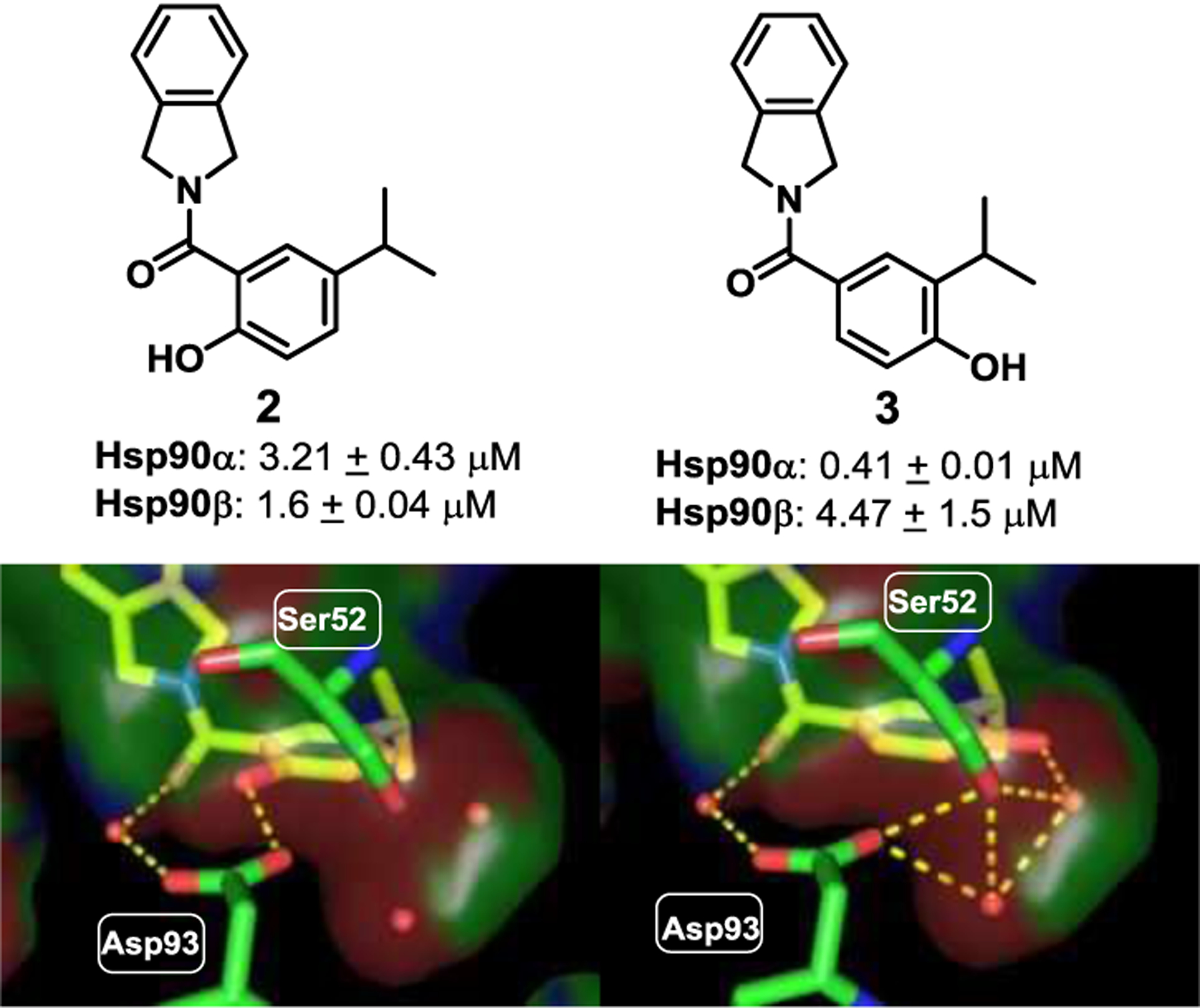

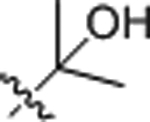

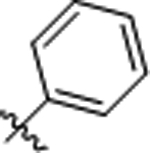

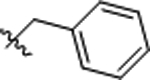

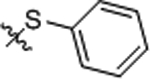

As can be seen in Figure 2, The resorcinol pharmacophore was shown to interact with Asp93 via the 2-phenol, whereas Ser52 hydrogen bonds with the 4-phenol via water molecules A and B. Therefore, systematic removal of each phenol was pursued to determine their contribution towards the binding to each isoform. Upon preparation, the desphenol variants, compound 2 (2-phenol) and compound 3 (4-phenol) (Figure 3) were evaluated for isoform selectivity.[21,22] Compound 3, which contains the 4-phenol, exhibited ~10-fold greater binding affinity for Hsp90α versus Hsp90β, whereas compound 2 bound Hsp90β with minimal preference (~2-fold).[21] Excited by these results, the isopropyl moiety at the 5-position was replaced to modulate the steric and electronic environment of the phenol, as well as to access the open conformation of Hsp90(Figure 4). Replacement of the 5-isopropyl substituent with a chlorine atom resulted in ~10-fold decrease in affinity, while the inclusion of iodine completely negated affinity. Introduction of bromine at the 5-position provided the highest selectivity (>30-fold) and a reasonable IC50 of ~ 2.73 μM. Intramolecular hydrogen-bonding interactions between the fluorine and phenol hydrogen could explain the decreased affinity that was observed for compound 7. Inclusion of a t-butyl group at the 5-position was shown to manifest affinity similar to 5, and supports the hypothesis that spheric bulk elicits selectivity for Hsp90α. Compounds 10, 11 and 12 were synthesized to probe Site 1 of Hsp90α (Figure 4, 4S), which is a flexible pocket that is lined with hydrophobic residues, while simultaneously reducing the distance between the 4-phenol and Ser52 to increase binding affinity and selectivity towards Hsp90α.

Figure 3.

Screening of phenols 2 and 3 and their proposed binding modes in Hsp90α (PDB code: 2XAB) and IC50’s as using fluorescence polarization (FP) assay. Compounds were incubated with Hsp90α/β and FITC-GDA in triplicate, and ± SD was measured.

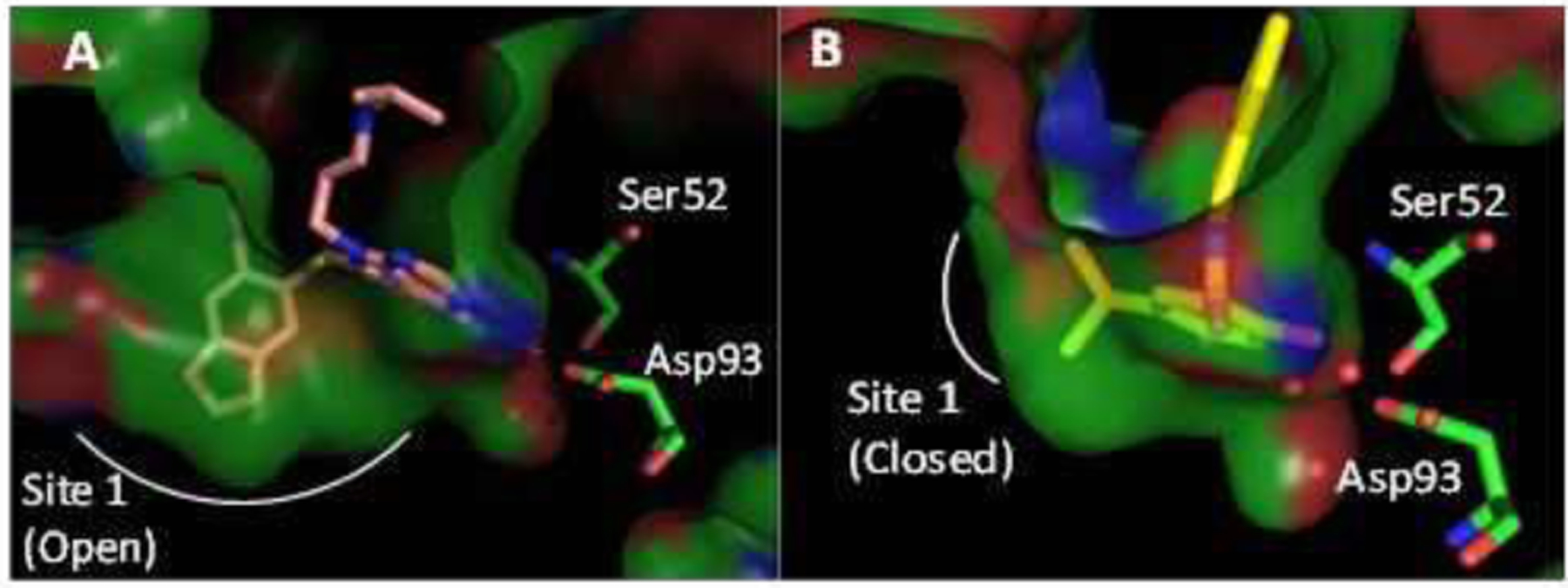

Figure 4.

A) Co-crystal structures of PU-H71 (PDB code: 2FWZ) and B) 1 (PDB code: 2XAB) with Hsp90α.

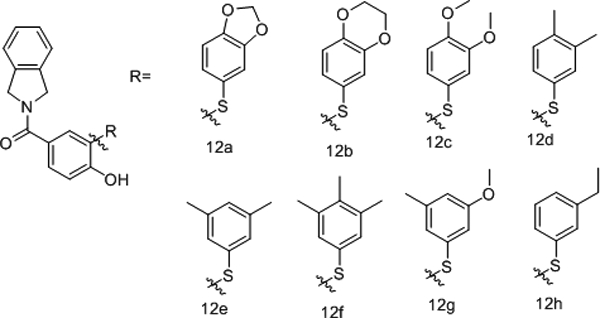

The binding affinity of 10, 11 and 12 were determined and compound 12 was found to bind Hsp90α with a IC50 of ~4.8 μM and >20-fold selectivity versus Hsp90β. As illustrated in Figure 4, the methylenedioxy ring induces the opening of Site 1, (Figure 4A, 4S). In contrast to PU-H71, which is a pan inhibitor that induces the opening of Site1, Compound 1 binds to the closed form of Hsp90 (Figure 4B). However, the 5-position thiophenol present in 12 is able to access Site 1 in a conformation that overlaps with the methylenedioxy ring of PU-H71 (Figure 4S C). Despite the presence of an identical Site 1 in both Hsp90α and Hsp90β, substitutions on the thiophenol were proposed to elicit different conformations of Hsp90α, perturbing interactions of the 4-Phenol with Ser52. Table 2 represents thiophenol analogs that were studied as well as their respective binding affinities (additional structure activity relationship (SAR), FP probe binding affinities for Hsp90 isoforms and solubility data can be found in supporting information). Compounds 12a and 12b contained methylenedioxy and ethylenedioxy rings, respectively, which were proposed to interact with Tyr139 via an additional hydrogen bond (Figure 5a).

Table 2:

Installation of substituted thiophenols and evaluation of binding affinity IC50 determined using fluorescence polarization (FP) assay. Compounds were incubated with Hsp90α/β and FITC-GDA in triplicates and ± SD was measured.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | IC50 Hsp90α (μM)(a) | IC50Hsp90β (μM)(a) | Fold Selectivity |

| 12a | 0.71 ± 0.03 | >50 | >70 |

| 12b | 0.52 ± 0.01 | 27.7±3.07 | ~53 |

| 12c | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 11.6±1.07 | ~22 |

| 12d | 0.84 ± 0.13 | >50 | >63 |

| 12e | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 37.5±3.8 | ~51 |

| 12f | 3.03±0.26 | >50 | >16 |

| 12g | 0.9±0.02 | >50 | >16 |

| 12h | 0.46±0.05 | 22.28±2.8 | ~48 |

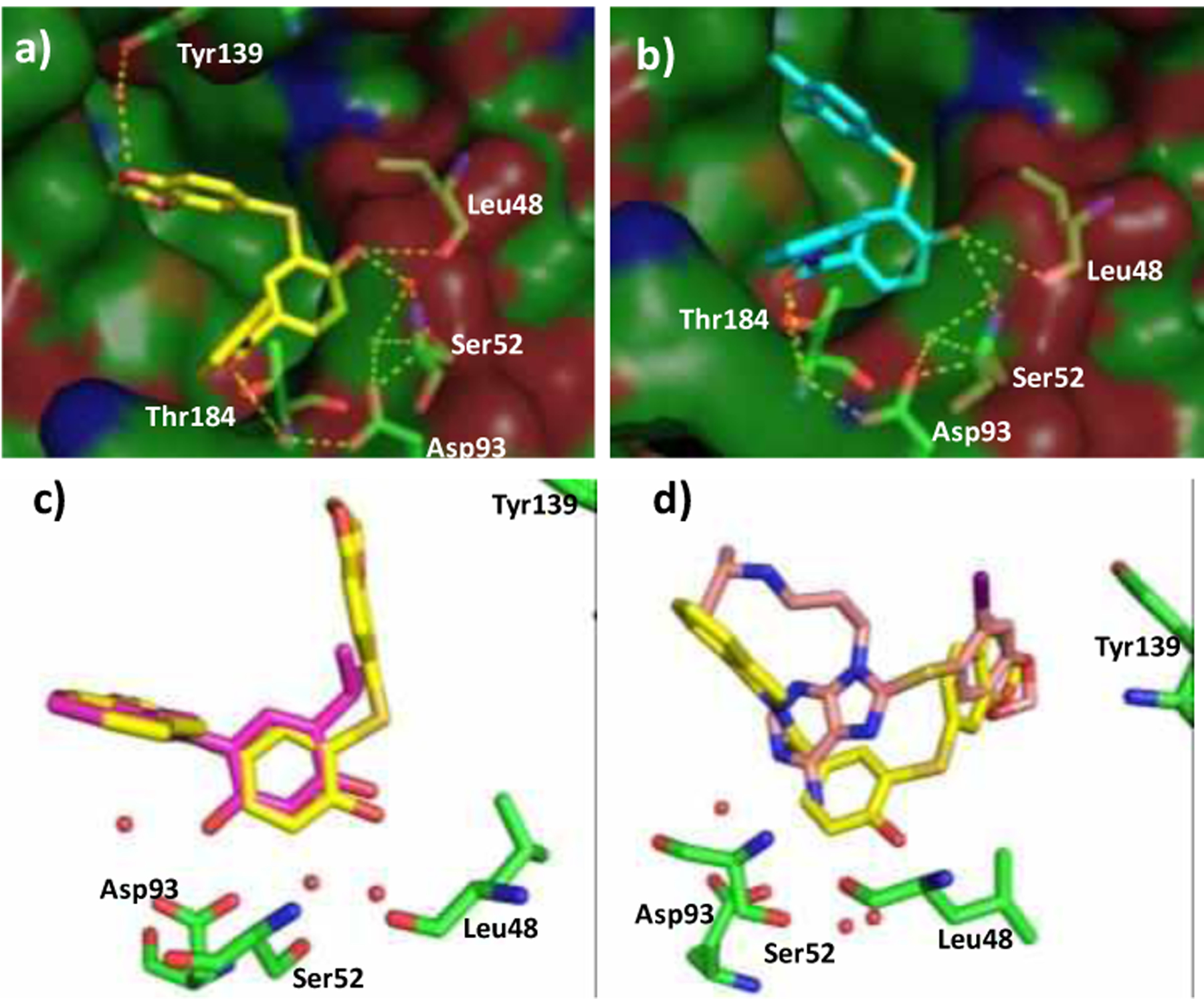

Figure 5:

a) Co-crystal structure of 12b with Hsp90α (PDB code: 7LSZ) b) Co-crystal structure of 12d with Hsp90α (PDB code: 7LT0) c) Overlay of the co-crystal structures of 12b and 1 bound to Hsp90α (PDB: 2XAB) d) Overlay of the co-crystal structures of 12b and PU-H71 bound to Hsp90α.

As predicted by our model, compounds 12a and 12b were shown to exhibit improved binding affinity for Hsp90α. Similarly, 12c, which contained the 3,4-dimethoxy group bound Hsp90α with an IC50 value of ~530 nM and ~22-fold selectivity versus Hsp90β. A methyl scan on the thiophenol ring led us to conclude that substitutions at 3- and 4-positions enhanced binding affinity. Consequently, substitutions at the 3- and 4-position of the thiophenol ring were sought, and eventually resulted in the preparation of 12d, 12e,12f, and 12g. Notably, 12d and 12e were found to exhibit a IC50 ~840 nM and ~720 nM for Hsp90α, whereas, the trimethyl substituted compound 12f bound with reduced affinity. The 3-methoxy-5-methyl substituted compound (12g) resulted in ~900 nM affinity for Hsp90α. Homologation of the 3-methyl substituent to the ethyl variant resulted in increased affinity. However, inclusion of a propyl group at the 3-position reduced affinity for Hsp90α (SI).

In order to study the binding mode of the Hsp90α-selective inhibitors, compounds 12b and 12d were co-crystalized with the N-terminal domain of Hsp90α. As expected, the crystal structures supported our hypothesis that the ethylenedioxy ring interacts with Tyr139 via a conserved water molecule, which increases binding affinity. In contrast, compound 12d does not afford secondary hydrogen bond with Tyr139. However, the hydrophobic occupation of Site 1 improves the binding affinity by reducing the entropic penalty, which explains the increased affinity manifested by 12h. It should also be noted that the 4-phenol interacts with Ser52 via water molecules A and B (Figure 2 and 5a–b). Therefore, the selectivity manifested by the benzenethiol containing compounds for Hsp90α was rationalized by overlaying the binding pose of the non-selective compound 1, and 12b bound to Hsp90α. As can be observed in Figure 5c, inclusion of the benzenethiol at the 5-position and the 4-phenol induce a conformational change that leads to the opening of Site 1. In fact, the orientation of the thioether fragment is different to that observed for the purine-class of Hsp90 pan-inhibitors (Figure 5d). The co-crystal structures of Hsp90α bound to 12b and 12d suggest the thioether to shift toward the adenine binding pocket (Figure 5c) by bringing the 4-phenol into close proximity to Ser52, a residue that differentiates the Hsp90α and Hsp90β binding sites.16−17 As a result, Hsp90α preferentially accommodates the benzenethiol containing 4-phenol.

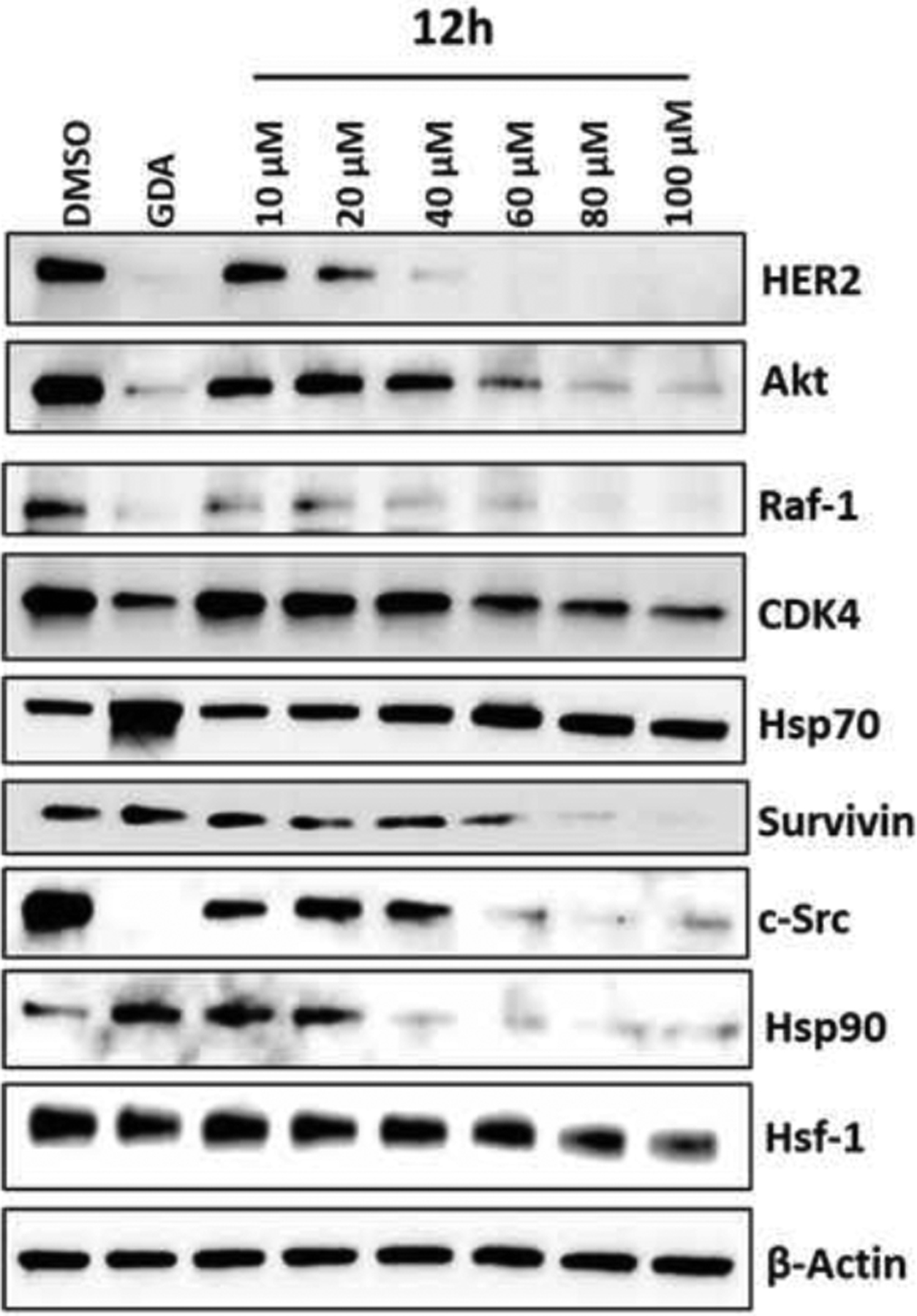

A NCI-60 cancer cell screen was performed with compounds 5 and 12d to determine the cellular response of Hsp90α-selective inhibitors. The growth of non-small cell lung cancer cell line, NCI-H522, melanoma cell line UACC-62, ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV-3, and renal cell carcinoma cell line UO-31 were selectively inhibited. Hsp90 client protein degradation was determined using NCI-H522 cells treated with increasing concentrations of 12h. In particular, the levels of Hsp90 client proteins Her2, Raf-1 and Akt decreased in a dose-dependent manner.

The Hsp90β-dependent substrate, CDK4, degraded at a higher concentration of 12h in comparison to c-Src, which is a Hsp90α-dependent client, highlighting preferential inhibition of Hsp90α in the cellular environment.[21,23] Hsp90α-dependent client survivin also decreased in a dose-dependent manner when treated with 12h. Levels of Hsp70 were induced albeit to a lesser extent, which is in contrast to Hsp90 pan-inhibitors such as GDA. Hsp90 levels were induced at lower concentrations of 12h, similar to GDA, however, it decreased with higher concentrations of 12h. Interestingly, levels of HSF1 also decreased upon treatment with 12h but only at high concentrations.

Conclusion

The design and development of isoform-selective inhibitors has remained a challenging task in medicinal chemistry, especially, when there exists significant sequence and conformational identity. Hsp90α and Hsp90β represent a major challenge for medicinal chemists, as only two amino acids vary in the ligand binding sites, and they are shielded behind two conserved water molecules. While an Hsp90β-selective inhibitor was previously shown to occupy the small subpocket in Hsp90β that results from the two amino acid difference, Hsp90α-selective inhibitors could not be developed via a similar approach. Therefore, the roles played by each phenol was interrogated and led to the identification of monophenol 3 as a new lead compound that exhibited ~10-fold selectivity for Hsp90α. Subsequent studies led to the development of compound 5, which exhibited greater selectivity for Hsp90α, but possessed modest binding affinity (IC50 ~2.7 μM.) Improvement in the binding affinity was sought by installation of a benzenethiol moiety to occupy Site 1. Further exploration of the benzenethiol side chain led to 12h, which manifested an IC50 of ~460 nM for Hsp90α and ~48-fold selectivity over Hsp90β. NCI Screening of the Hsp90α-selective inhibitors revealed cancer cell lines that are selectively inhibited by these compounds. Moreover, it was determined that Hsp90α-dependent substrates are readily degraded in the presence of Hsp90α-selective inhibitors, but Hsp90β-dependent clients were not affected until higher concentrations were reached. In totality, the first Hsp90α-selective inhibitor was developed via a structure-based approach to yield a drug-like small molecule that manifests good affinity and reasonable selectivity in both recombinant and cellular assays. The full utility and optimization of these inhibitors continue and the results from such studies will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of client proteins with 12h in NCI-H522 cell line. DMSO and 500 nM Geldanamycin (GDA) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Table 1:

Replacement of the isopropyl group, IC50 determined using fluorescence polarization (FP) assay. Compounds were incubated with Hsp90α/β and FITC-GDA in triplicate, and ± SD was measured.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R group | IC50 Hsp90α (μM)(a) | IC50 Hsp90β (μM)(a) |

| 4 | Cl | 4.69 ± 0.27 | >100 |

| 5 | Br | 2.73 ± 0.19 | >100 |

| 6 | I | >100 | >100 |

| 7 | CF3 | 7.90 ± 1.18 | >100 |

| 8 |  |

2.62 ± 0.08 | >100 |

| 9 |  |

0.65 ± 0.04 | 12.92 ± 1.92 |

| 10 |  |

>50 | >50 |

| 11 |  |

>25 | >50 |

| 12 |  |

4.87 ± 0.29 | >100 |

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support of this work via the National Institutes of Health to BSJB (CA213566), RLM and JD (CA219907), and the Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station to RLM (OKL03159) and JD (OKL03060). The research is also supported in part by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Award P20GM103640). We thank the staff of beam-line 14 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource for their support.

References

- [1].Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S, Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2010, 11, 515–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Park H-K, Yoon NG, Lee J-E, Hu S, Yoon S, Kim SY, Hong J-H, Nam D, Chae YC, Park JB, Kang BH, Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2020, 52, 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Powers MV, Workman P, FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3758–3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Neckers L, Workman P, Clin. Cancer. Res 2012, 18, 64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].da Silva VC, Ramos CH, J. Proteomics 2012, 75, 2790–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Holzbeierlein JM, Windsperger A, Vielhauer G, Curr. Oncol. Rep 2010, 12, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jhaveri K, Taldone T, Modi S, Chiosis G, Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012, 1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Yuno A, Lee MJ, Lee S, Tomita Y, Rekhtman D, Moore B, Trepel JB, Methods Mol. Biol 2018, 1709, 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hong DS, Banerji U, Tavana B, George GC, Aaron J, Kurzrock R, Cancer Treat. Rev 2013, 39, 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hoter A, El-Sabban ME, Naim HY, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang X, Song X, Zhuo W, Fu Y, Shi H, Liang Y, Tong M, Chang G, Luo Y, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 21288–21293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li W, Sahu D, Tsen F, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eustace BK, Sakurai T, Stewart JK, Yimlamai D, Unger C, Zehetmeier C, Lain B, Torella C, Henning SW, Beste G, Scroggins BT, Neckers L, Ilag LL, Jay DG, Nat. Cell Biol 2004, 6, 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bohonowych JE, Hance MW, Nolan KD, Defee M, Parsons CH, Isaacs JS, Prostate 2014, 74, 395–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Voss AK, Thomas T, Gruss P, Development 2000, 127, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Grad I, Cederroth CR, Walicki J, Grey C, Barluenga S, Winssinger N, De Massy B, Nef S, Picard D, PLoS One 2010, 5, e15770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kajiwara C, Kondo S, Uda S, Dai L, Ichiyanagi T, Chiba T, Ishido S, Koji T, Udono H, Biology open 2012, 1, 977–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Duerfeldt AS, Peterson LB, Maynard JC, Ng CL, Eletto D, Ostrovsky O, Shinogle HE, Moore DS, Argon Y, Nicchitta CV, Blagg BSJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 9796–9804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Patel PD, Yan P, Seidler PM, Patel HJ, Sun W, Yang C, Que NS, Taldone T, Finotti P, Stephani RA, Gewirth DT, Chiosis G, Nat. Chem. Biol 2013, 9, 677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mishra SJ, Ghosh S, Stothert AR, Dickey CA, Blagg BS, ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 244–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Khandelwal A, Kent CN, Balch M, Peng S, Mishra SJ, Deng J, Day VW, Liu W, Subramanian C, Cohen M, Holzbeierlein JM, Matts R, Blagg BSJ, Nature Communications 2018, 9, 425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Murray CW, Carr MG, Callaghan O, Chessari G, Congreve M, Cowan S, Coyle JE, Downham R, Figueroa E, Frederickson M, Graham B, McMenamin R, O’Brien MA, Patel S, Phillips TR, Williams G, Woodhead AJ, Woolford AJA, J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 5942–5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Liu W, Vielhauer GA, Holzbeierlein JM, Zhao H, Ghosh S, Brown D, Lee E, Blagg BS, Mol. Pharmacol 2015, 88, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.