Abstract

Introduction:

There is growing recognition that systematically obtaining the patient’s perspective on their health experience, using patient-reported outcomes (PRO), can be used to improve patient care in real time. Few PRO systems are designed to monitor and provide symptom management support between visits. Patients are instructed to contact providers between visits with their concerns, but they rarely do, leaving patients to cope with symptoms alone at home. We developed and tested an automated system, Symptom Care at Home (SCH), to address this gap in tracking and responding to PRO data in-between clinic visits. The purpose of this paper is to describe SCH as an example of a comprehensive PRO system that addresses unmet need for symptom support outside the clinic.

Methods for PRO Score Interpretation:

SCH uses pragmatic, single-item measures for assessing symptoms, which are commonly used and readily interpretable for both patients and providers. We established alerting values for PRO symptom data, which was particularly important for conserving oncology providers’ time in responding to daily PRO data.

Methods for Developing Recommendations for Acting on PRO Results:

The SCH system provides automated, just-in-time self-management coaching tailored to the specific symptom pattern and severity levels reported in the daily call. In addition, the SCH system includes a provider decision support system for follow-up symptom assessment and intervention strategies.

Discussion:

SCH provides PRO monitoring, tailored automated self-management coaching, and alerts the oncology team of poorly controlled symptoms with a provider dashboard that includes evidence-based decision support for follow-up to improve individual patients’ symptom care. We particularly emphasize our process for PRO selection, rationale for determining alerting thresholds, and the design of the provider dashboard and decision support. Currently, we are in the process of updating the SCH system, developing both web-based and app versions in addition to interactive voice response phone access and integrating the SCH system in the electronic health record.

Keywords: chemotherapy, decision support systems, eHealth, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, patient-reported outcomes, symptom management, telehealth

Measurement of symptoms paired with patient-provider symptom communication can reduce symptom distress and related poor outcomes in cancer care.1–7 Yet, best practices for implementing symptom monitoring and management in cancer care are still emerging.8–19 Optimal symptom management is particularly challenging to achieve between oncology clinic visits when patients are at home.20 Symptoms related to cancer and its treatment present in various patterns and intensity, can change rapidly, and impact quality of life and even survival.21–25 Most patients experience multiple symptoms concurrently. Episodic assessment and management of symptoms at clinic visits may miss key episodes of severe symptoms experienced by patients at home.

Current practices are suboptimal to educate and assist patients at home with poorly controlled symptoms and result in unnecessary suffering, emergency department visits and unplanned hospitalizations.13 Patients are hesitant to contact their oncology providers about escalating symptoms even when they have been instructed to do so. In our own research we found that patients experiencing symptoms of moderate and severe intensity only contacted their providers 5% of the time.1,26 With the development of automated technologies, new approaches to remote monitoring and symptom care can be developed utilizing patient-reported outcomes (PRO) systems to improve symptom care in the home.27

Since 2000, we have developed and tested an automated system, Symptom Care at Home (SCH) that addresses the shortfall in home symptom monitoring for cancer patients and their family caregivers. SCH is an example of a pragmatic approach to comprehensive PRO systems. Development of the SCH system was an iterative and interactive process informed by the findings of multiple pilot studies and randomized trials. Several principles have guided our process and decisions. First, our focus was on improving symptoms and quality of life based on the individual patient’s perspective. SCH was not developed with the goal of measuring population-level outcomes. Our decisions were guided primarily using a patient/family caregiver-centric lens and, second, by what would be efficient and helpful for oncology providers. We considered: (1) the need for efficient and continuous monitoring of symptoms to capture change; (2) the need to provide self-care coaching tailored to the pattern and intensity of symptoms, at the time the patient was experiencing those symptoms; (3) automated alerts to providers about unrelieved symptoms to bypass patient reluctance to contact providers; and (4) support for the providers to improve symptom care through dashboards combined with evidence-based decision support.

The initial telephone-based interactive voice response (IVR) SCH system included daily home monitoring of chemotherapy symptoms with provider alerts for poorly controlled symptoms. An initial pilot study showed that the IVR system was acceptable to patients, and able to generate usable symptom data with oncology provider alerts based on patient-reported data.28 Although our first randomized trial showed high patient satisfaction and usability, there was no improvement in symptom outcomes.29 On exploration, we found that oncology providers rarely acted on alerts, describing barriers to follow-up that were consistent with clinical inertia and health system barriers.29–32 Our subsequent randomized controlled trial was designed to specifically address provider beliefs that symptom care intensification is unlikely to improve outcomes.1 We developed SCH utilizing the original IVR system but expanded it to include 4 components: automated daily monitoring of 11 chemotherapy-related symptoms, automated patient self-management coaching tailored to the symptom pattern reported during the call, automated provider alerts for poorly controlled symptoms, and a web-based dashboard with a guideline-based decision support system (DSS). The dashboard and decision support were used by study-employed nurse practitioners to provide telephone follow-up to intensify symptom care for poorly controlled symptoms. Remote symptom monitoring and management by nurse practitioners decreased symptom severity overall, for 10 of the individual symptoms monitored, dramatically decreased days where the highest symptom(s) was reported at moderate or severe intensity, and increased days of no or mild symptom intensity as compared with usual care.1 Patients can be enrolled to the SCH system for the length of time the oncology provider specifies. In our randomized controlled trials, patients were enrolled for the course of chemotherapy.1,29 We have subsequently adapted and tested SCH for family caregivers of patients with life-limiting cancer. Currently, we are examining the value of the individual components of the intervention: self-management coaching, oncology provider follow-up to intensify care, and oncology provider follow-up utilizing the DSS. We are assessing the degree to which each component contributes to symptom reduction.

METHODS FOR PRO SCORE INTERPRETATION

Measurement Selection

We utilized a panel of supportive care and palliative care clinicians and symptom science research experts to guide the measurement approach. The primary driver in selecting our measurement approach was the need to monitor symptoms on an ongoing basis so we could provide self-management coaching and alert providers as needed. Rather than a more complex assessment with multi-item individual or composite symptom measures, we chose a pragmatic screening approach that could quickly and frequently track individual symptoms with the least burden to patients. Composite measures provide data on overall symptom burden, whereas individual symptom screening facilitates interventions targeting symptoms that are poorly controlled. We asked patients to report their symptom experience on a daily basis, ideally before noon, so providers could follow-up in a timely manner. We chose to use single-item symptom measures utilizing a 1–10 rating scale. This simple approach to symptom measurement is commonly used and readily interpretable for both patients and providers. Given our approach, with daily longitudinal data on the presence and severity of 11 symptoms, clinicians are provided a detailed picture of the patient’s experience in-between clinic visits.

Using branching logic, the SCH system efficiently assesses the presence of 11 symptoms. Symptoms cover both physical and psychosocial concerns. Once the patient reports symptom presence, SCH assesses the severity of endorsed symptoms on a 1–10 scale. For some symptoms additional drill down questions are asked to provide detailed information for the provider and to further tailor self-care coaching. For example, for vomiting, the drill down includes questions about the number of times vomited, the number of glasses of fluid consumed and kept down, presence of dizziness and questions about antiemetic medication use. Besides symptom assessment, we ask additional questions including the degree of symptom interference on functioning and for those working, whether they worked if a workday. The automated PRO screening averages 4:19 minutes to complete.1 We have used an iterative process in selecting the symptoms to be screened and our process for obtaining PRO data. For example, in our first study the daily call adherence was 65%.29 At the end of the study, we asked patients why they missed calls and 35% said they would skip a call when they were too sick to call. Because intervening to improve symptom outcomes was our objective, we added an initial strategic filter to allow patients to call to simply report they were too sick to report, generating a provider alert for follow-up in the intervention group. In the subsequent study, daily call adherence was 90%.1

Selecting Provider Alert Thresholds

An ongoing challenge in using PRO measures for monitoring and managing symptoms in clinical care is determining when a PRO score requires further assessment and/or intervention by providers.33 Guidelines for when to initiate symptom management strategies are not well defined.34,35 We recognized that establishing alerting values for PRO symptom data were particularly important as we were screening PROs daily and it was important to conserve oncology providers’ time. The goal was to target patients who would benefit from symptom care intensification while helping providers to rapidly identify clinically relevant trends that require reassessment of care.1,33,36–43

The choice of 0–10 scaling of the PRO screening for presence and severity of symptoms simplified the interpretation and was a pragmatic, provider-focused choice. Such scaling is widely used by clinicians and often collapsed categorically to none, mild, moderate, and severe. Further work has been done to determine cut-point scores for a variety of symptoms, pain notable among them.39–43 Although there is some variation in cut-points, particularly for moderate versus severe designation, several studies support—0 for none, 1–3 for mild, 4–7 for moderate, and 8–10 for severe. Our content experts chose this categorization. As a clinically focused tool to guide improvement in individual patient’s symptoms at home, there was debate about when to engage the provider with an alert. From our previous study, we knew that providers had not initiated follow-up in the face of alert data so we were cognizant of burdening providers. At the same time, we felt that early intervention before symptoms escalated in severity might be important to provide better control and decrease emergency department use as the source for symptom management.29 Further study would contribute to understanding severity levels to initiate further symptom care to prevent symptom escalation. Our panel decided that for 7 symptoms such as pain, alerts would trigger for moderate through severe symptom scores (4–10). The remaining 4 symptoms (fatigue, disturbed sleep, anxiety, and depressed mood) would alert at the severe level (8–10). But for a moderate score (4–7), they would only trigger an alert when a clear trend was indicated by 3 moderate or higher scores (4–10) over the past 7 days. Besides the symptom severity alerts, there are additional responses that generate a clinical alert to providers, including specific responses to drill down questions such as vomited ≥5 times or a response of too sick to call.26 SCH also generates alerts for missed reporting calls or when a patient calls-in a notes that she/he is too sick to call with no other data reported. Once an alert threshold is met, at the end of the patient call, the SCH system immediately transmits the alert data to the provider web-based dashboard and DSS. Additional email, text alerts, or pager notification can be generated if desired.

METHODS FOR DEVELOPING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTING ON PRO RESULTS

Triggers for Patient Self-Management Coaching

In addition to provider action, improving symptom outcomes requires patient engagement in self-care. Information on self-care is provided to patients as standard of care but is not optimized to be usable. The SCH system addresses this by providing automated, just-in-time self-management coaching tailored to the specific symptom pattern and severity levels reported in the daily call.26 Coaching is based on national evidence-based guidelines and includes both short-term actions, such as fluid intake for nausea and vomiting, and longer term behavioral actions, such as beginning and maintaining an exercise program for fatigue. The self-management coaching involves algorithms that conform to the severity level reported (mild, moderate, or severe), whether the symptom has been reported over the past 7 days and if it is improving or worsening. The expert panel that developed the screening approach also guided the development of the algorithms to generate self-management messages. In our studies to date patients have not been provided their data. However, in the self-management coaching a pattern is sometimes acknowledged. For example, “We see that you have been having trouble sleeping over the past few days.” Patients receive the self-management coaching immediately on the IVR call and there is a library of self-management information that patients can access at any time. The coaching adds, on average, 30 seconds to the daily call. We query patients about the value of the messages and ways to improve them with each succeeding study. Patients report that they readily bond with the voice and value the individualized support, as one patient put it, “I feel like someone else is on the team to help.” New evidence on symptom self-management is reviewed annually and SCH is updated.

Provider-facing Data Display Dashboard

The display of PRO symptom data in a useable provider-facing dashboard is an essential component of a comprehensive PRO system designed for individual patient care. The dashboard must efficiently display symptom scores, integrating symptom monitoring results into the clinical workflow so providers can respond.44–46 When presented with PRO symptom data, providers need to be able to correctly interpret PRO data to make quick judgements.44,47 Unfamiliar measures and scoring algorithms make it more difficult to interpret PROs. There is evidence that providers often have difficulty understanding the meaning of symptom scores and that this may reduce clinical action.46

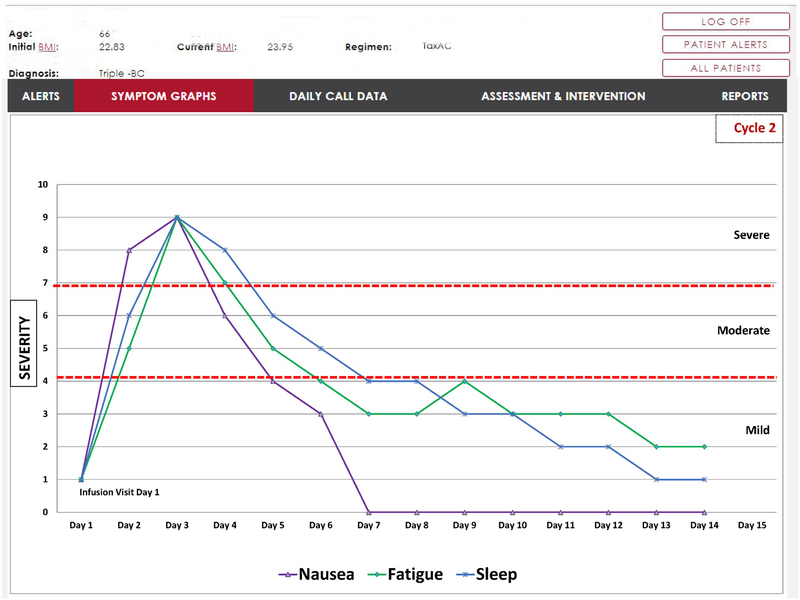

In developing the PRO data display dashboard for alerting symptoms, the panel of content experts was expanded to include additional clinicians (nurse practitioners and oncologists) and dashboard programmers. Once again decisions were based on common ways of representing clinical data familiar to providers. We asked providers to comment on the dashboard display system and indicate features that might be useful and then incorporated that feedback in the display design. The initial page of the web-based dashboard shows the provider’s list of patients who have alerted during the day, the symptoms that have alerted and their severity levels so patients of greatest concern can be triaged. Clicking on the patient’s name allows the provider to view the current day’s PRO data including the drill down information. They also have a tab for graphic display of the symptom over time (Fig. 1). Individual symptom scores are presented in simple line graphs with dates on the x-axis and score on the y-axis (0–10 scale). For those on active treatment, this allows providers to see patterns over each cycle of treatment (dates are separated by vertical lines between cycles). For example, nausea not present on the first day after chemotherapy but appearing on the second or third day shows a pattern of delayed nausea. We also provide horizontal lines discriminating mild, moderate, and severe scores so the provider can quickly see the number of mild, moderate, and severe days experienced for that symptom (all data points are represented on the graph, not just alerting scores). In addition, the provider can overlay symptom graphs to look at symptom clustering, for example, they may quickly see that pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance always co-occur. In user testing, providers have commented positively on these features. They appreciated the combination of current symptom data from the alert and historical trends that quickly placed, in context, the individual patient’s overall symptom experience. Future plans include more formal evaluations of a variety of dashboard displays to determine the most optimal.

FIGURE 1.

Example of longitudinal symptom severity display.

Provider DSS

Previous evidence suggests that provider inaction and clinical inertia may pose significant barriers to the use of PROs to enhance symptom management.1,8,48 In the context of cancer symptoms, clinical inertia refers to provider uncertainty that intensification of symptom management will improve symptom outcomes.30–32 Recent trials of routine cancer symptom monitoring and management have found that provider alerts to moderate or severe symptoms, without symptom guidelines, may not lead to reduced symptoms.29,49 When provided with evidenced-based decision support indicating follow-up action, providers may be more likely to respond to alerting symptoms.1,8,48

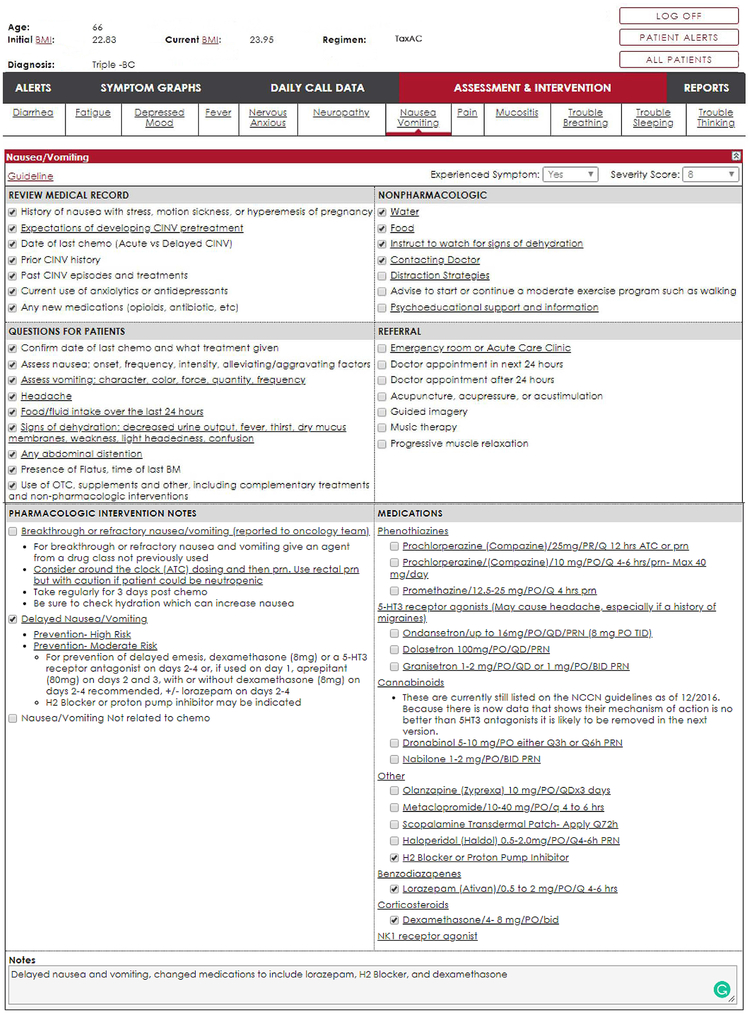

The SCH system provides a DSS embedded with the data dashboard (Fig. 2). The DSS provides follow-up symptom assessment and intervention strategies based on published guidelines from several professional organizations. The primary source for the DSS development was the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Supportive Care Guidelines. Other sources included the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Mucositis from the Multidisciplinary Association for Supportive Care in Cancer, the Oncology Nursing Society Putting Evidence Into Practice Resources program, the Physician Data Query resources provided by the National Cancer Institute, and Cancer Care Ontario Symptom Management Guidelines. The panel of content experts distilled the guidelines into 4 areas: (1) further assessment including additional history, further characterization of symptoms, laboratory, and radiology; (2) pharmacological interventions; (3) nonpharmacological interventions; and (4) referrals. The DSS also provides a link to the primary national guideline for the symptom. Checkboxes are placed next to each of the suggested strategies to allow the provider to quickly document the assessments, interventions, and referrals made. Updates to national guidelines are reviewed annually and the DSS is updated. To insure local context has been considered, we review DSS embedded guidelines with the oncology practices to make sure recommendations are aligned with formulary drug availability and available resources for referral. Sometimes choice among recommended drugs is influenced by insurance plan reimbursement In addition to the guideline-based symptom and intervention strategies, treatment start date is noted in the DSS and updated as needed. Other data, such as concurrent medications are accessed through the electronic health record.

FIGURE 2.

Example of provider decision support dashboard display. ATC indicates around the clock; BM, bowel movement; CINV, chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; OTC, over the counter; PRN, pro re nata.

DISCUSSION

SCH is an example of a pragmatic approach to comprehensive PRO systems that screen multiple cancer symptoms and patient-reported behaviors, provide automated, just-in-time, tailored self-management coaching, alert the oncology team about poorly controlled symptoms, and provide the team a dashboard and DSS to follow-up with patients to efficiently intensify symptom care between clinic visits. Important to the successful development of SCH was the dynamic design process that emphasized an iterative cycle of design, test, and improve based on study results and user feedback. Starting with clarity on the purpose and principles that drove the design of each component, we worked with our content experts, utilizing the literature to build the system, and then tested it in a series of studies that included extensive patient and provider feedback. The insights gained formed the basis for system updates. Our pragmatic decision to use single-item-based screening reduces the precision of measurement. Thus, the use of SCH as a population-level outcomes tool and comparison to multi-item scales may be limited. Nonetheless, single-item measures are considered valid and reliable as symptom measures, particularly for screening purposes; they reduce participant burden and support ease of clinical interpretation.50 Because symptom PROs are measured daily, there is rich capture of the patient’s experience at home. These characteristics fit our primary intent to develop a PRO system to monitor and intervene on poorly controlled symptoms between clinic visits. Technologic advances in recent years provide opportunities to improve and enhance the SCH system further. Currently, SCH is a phone-based IVR system which allows the widest access as it utilizes telephone lines and does not require internet access. We are in the process of updating the system and developing both web-based and app versions in addition to IVR phone access. Eventually, patients will be able to select their preferred platform for reporting PRO data among the 3 approaches. In addition, SCH integration into electronic health records is planned in the near future and will enhance adoption and alignment with clinical workflow. In our current update, we are designing the platform to be easily editable so the system can be customized to different purposes without requiring significant programing and cost to adapt. Ultimately, for SCH or any other PRO system to be utilized for monitoring and care beyond the walls of a cancer center or community oncology practice, reimbursement models and care delivery system workflows will need to adapt to recognize and incorporate this new value-based, patient-centric approach to providing PRO monitoring and symptom care.

KEY POINTS.

We developed Symptom Care at Home (SCH), a comprehensive automated PRO system, to overcome gaps in care when cancer patients are at home between clinic visits.

The design of SCH was based on pragmatic decisions to maximize features familiar to providers and patients.

Remote PRO monitoring and symptom management can be successfully implemented through a pragmatic approach to designing the system.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the PRO-cision Medicine Methods Toolkit paper series funded by Genentech.

Supported by Genentech, the United States Department of Defense (DAMD17-00-1-0695), National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA89474), National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01CA120558), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (8UL1TR000105). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors were paid an honorarium from Genentech for development of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The PRO-cision Medicine Methods Toolkit paper series was presented during a symposium at the 2018 Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research, Dublin, Ireland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med. 2017;6:537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry DL, Blumenstein BA, Halpenny B, et al. Enhancing patient-provider communication with the electronic self-report assessment for cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1029–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DL, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Electronic self-report assessment for cancer and self-care support: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleeland CS, Wang XS, Shi Q, et al. Automated symptom alerts reduce postoperative symptom severity after cancer surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry DL, Hong F, Blonquist T, et al. Self report assessment and support for cancer symptoms: impact on hospital admissions and emergency department visits. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl):e20552. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Howell D, et al. Does routine symptom screening with ESAS decrease ED visits in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy? Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:3025–3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mooney K, Berry DL, Whisenant M, et al. Improving cancer care through the patient experience: how to use patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. ASCO EdBook. 2017;37:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, et al. Employment and cancer: findings from a longitudinal study of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Idler E, et al. Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105:209–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esther Kim JE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE, et al. A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:715–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshields TL, Potter P, Olsen S, et al. The persistence of symptom burden: symptom experience and quality of life of cancer patients across one year. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1089–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbera L, Atzema C, Sutradhar R, et al. Do patient-reported symptoms predict emergency department visits in cancer patients? A population-based analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:427.e5–437.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spoelstra SL, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Treatment with oral anticancer agents: symptom severity and attribution, and interference with comorbidity management. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Herk-Sukel MP, van de Poll-Franse LV, Voogd AC, et al. Half of breast cancer patients discontinue tamoxifen and any endocrine treatment before the end of the recommended treatment period of 5 years: a population-based analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010; 122:843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon R, Latreille J, Matte C, et al. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients with regular follow-up. Can J Surg. 2014;57:26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Cheville AL. Symptom improvement requires more than screening and feedback. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3351–3352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry DL, Blonquist TM, Hong F, et al. Self-reported adherence to oral cancer therapy: relationships with symptom distress, depression, and personal characteristics. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1587–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lebovits AH, Strain JJ, Schleifer SJ, et al. Patient noncompliance with self-administered chemotherapy. Cancer. 1990;65:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleeland CS. Cancer-related symptoms. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2000;10: 175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayl AE, Meyers CA. Side-effects of chemotherapy and quality of life in ovarian and breast cancer patients. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whisenant M, Wong B, Mitchell SA, et al. Distinct trajectories of fatigue and sleep disturbance in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44:739–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boehmke MM, Dickerson SS. Symptom, symptom experiences, and symptom distress encountered by women with breast cancer undergoing current treatment modalities. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:382–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodd MJ, Cho MH, Cooper BA, et al. The effect of symptom clusters on functional status and quality of life in women with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck S, Eaton LH, Echeverria C, et al. Symptom Care at Home: developing an integrated symptom monitoring and management system for outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Comput Inform Nurs. 2017;35:520–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liss HJ, Glueckauf RL, Ecklund-Johson EP. Research on telehealth and chronic medical conditions: critical review, key issues, and future directions. Rehabil Psychol. 2002;47:8–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mooney KH, Beck SL, Friedman RH, et al. Telephone-linked care for cancer symptom monitoring: a pilot study. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mooney KH, Beck SL, Friedman RH, et al. Automated monitoring of symptoms during ambulatory chemotherapy and oncology providers’ use of the information: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2343–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aujoulat I, Jacquemin P, Rietzschel E, et al. Factors associated with clinical inertia: an integrative review. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:825–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips LS, Twombly JG. It’s time to overcome clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:783–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Okuyama T, et al. Using the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in clinical practice for patient management: identifying scores requiring a clinician’s attention. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:2685–2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon S, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. The utility of screening in the design of trials for symptom management in cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:606–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldenmenger WH, de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, et al. Cut points on 0–10 numeric rating scales for symptoms included in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:714–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Wolff AC, et al. Feasibility and value of PatientViewpoint: a web system for patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Psychooncology. 2013;22:895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen RE, Potosky AL, Moinpour CM, et al. United States population-based estimates of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system symptom and functional status reference values for individuals with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1913–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerbershagen HJ, Rothaug J, Kalkman CJ, et al. Determination of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain on the numeric rating scale: a cut-off point analysis applying four different methods. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paul M, Zelman DC, Smith M, et al. Categorizing the severity of cancer pain: further exploration of the establishment of cutpoints. Pain. 2005;113:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, et al. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61:277–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendoza TR, Chen C, Brugger A, et al. The utility and validity of the modified brief pain inventory in a multiple-dose postoperative analgesic trial. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Given B, Given CW, Sikorskii A, et al. Establishing mild, moderate, and severe scores for cancer-related symptoms: how consistent and clinically meaningful are interference-based severity cut-points? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:126–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen RE, Snyder CF, Abernethy AP, et al. Review of electronic patient-reported outcomes systems used in cancer clinical care. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e215–e222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen RE, Rothrock NE, DeWitt EM, et al. The role of technical advances in the adoption and integration of patient-reported outcomes in clinical care. Med Care. 2015;53:153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bantug ET, Coles T, Smith KC, et al. Graphical displays of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) for use in clinical practice: what makes a PRO picture worth a thousand words? Pat Educ Couns. 2016;99:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brundage MD, Smith KC, Little EA, et al. Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2457–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes EF, Wu AW, Carducci MA, et al. What can I do? Recommendations for responding to issues identified by patient-reported outcomes assessments used in clinical practice. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yount SE, Rothrock N, Bass M, et al. A randomized trial of weekly symptom telemonitoring in advanced lung cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:973–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR. Symptom measurement by patient report. In: Cleeland CS, Fisch MJ, Dunn AJ, eds. Cancer Symptom Science. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011:268–284. [Google Scholar]