Abstract

Objectives

Muscle mass is one of the key components in defining sarcopenia and is known to be important for locomotion and body homeostasis. Lean mass is commonly used as a surrogate of muscle mass and has been shown to be associated with increased mortality. However, the relationship of lean mass with mortality may be affected by different clinical conditions, modalities used, cut-off point to define low or normal lean mass, and even types of cancer among cancer patients. Thus, we aim to perform a comprehensive meta-analysis of lean mass with mortality by considering all these factors.

Methods

Systematic search was done in PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase for articles related to lean mass and mortality. Lean mass measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry, bioelectrical impedance analysis, and computerized tomography were included.

Results

The number of relevant studies has increased continuously since 2002. A total of 188 studies with 98 468 people were included in the meta-analysis. The association of lean mass with mortality was most studied in cancer patients, followed by people with renal diseases, liver diseases, elderly, people with cardiovascular disease, lung diseases, and other diseases. The meta-analysis can be further conducted in subgroups based on measurement modalities, site of measurements, definition of low lean mass adopted, and types of cancer for studies conducted in cancer patients.

Conclusions

This series of meta-analysis provided insight and evidence on the relationship between lean mass and mortality in all directions, which may be useful for further study and guideline development.

Keywords: Lean mass, Sarcopenia, Mortality, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

1. Introduction

Muscles are critical for normal human anatomical and physiological functioning, including posture, locomotion, respiration, and regulation of whole body metabolism and energy balance [1]. Loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) not just affects mobility, but also causes frailty and increases risk of mortality [2]. It is known that obesity is associated with increased mortality, while lean mass (a proxy of muscle mass) is at the opposite end of the spectrum to obesity, with low lean mass being detrimental to health. A previous meta-analysis comprising more than 9 million people showed a J- or U-shaped association between body mass index (BMI) and all-cause mortality [3]. However, as BMI reflects both lean mass and fat mass, the independent relationship of the former with mortality remains uncertain.

Given the importance of sarcopenia, it has been endorsed as an independent condition by the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) Code in 2016. Nevertheless, there is no consensus on the definition of sarcopenia, although several definitions have been proposed for sarcopenia in elderly and cancer patients [[4], [5], [6], [7]]. The Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) recommended using dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) as one of the diagnostic tools for sarcopenia [4]. However, a recent study suggested that lean mass measured by DXA should not be used in defining sarcopenia, since inconsistent associations were observed for DXA-derived lean mass with various clinical outcomes, such as fall, mobility limitation, and hip fractures [8]. Notably, the authors [8] and others [9] acknowledged the limitation of measurement method (measurement of lean mass instead of muscle mass) and studied population (relatively healthy elderly) may affect the validity of the conclusion.

Indeed, it is commonly observed in the literature that muscle mass was measured using different methods, and different cut-offs of muscle mass were adopted in defining people as having normal or low muscle mass, making the comparison and interpretation difficult. Although a few meta-analyses were conducted to evaluate the relationship between lean mass and mortality, the analyses were either small-scale, conducted in a subgroup with a particular health condition only, or combined the data based on dichotomized lean mass phenotype [[10], [11], [12], [13]]. We are thus lacking a comprehensive overview of how lean mass contributes to mortality. The performance of lean mass in predicting mortality in different health conditions and measurement modalities are also unknown. To evaluate the relationship of lean mass with mortality comprehensively, we conducted a large-scale meta-analysis of the association between lean mass and mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase for articles published up to December 20, 2017. The following algorithms were used for the literature search:

("lean mass" OR "ALM" OR "muscle mass") AND ("death" OR "mortality" OR "outcome");

("lean mass" OR "Body composition" OR "muscle mass" OR "sarcopenia" OR "bio-impedance" OR "frailty") AND ("death" OR "mortality" OR "cause of death" OR "fatal outcome" OR "mortality, premature" OR "survival rate" OR "mortal" OR "fatal") AND ("cohort studies" OR "follow-up studies" OR "longitudinal studies" OR "prospective studies" OR "retrospective studies" OR "cohort" OR "longitudinal" OR "prospective" OR "follow-up" OR "retrospective") AND ("association" OR "associated"); ("lean mass" OR "Body composition" OR "muscle mass" OR "sarcopenia" OR "bio-impedance" OR "bioimpedance") AND ("death" OR "mortality" OR "cause of death" OR "fatal outcome" OR "mortality, premature" OR "survival rate" OR "mortal" OR "fatal" OR "survival" OR "prognosis" OR "prognostic").

The inclusion criteria were original studies investigating the relationship between lean mass and all-cause mortality or overall survival. The reference lists of systematic reviews and meta-analyses were also checked for inclusion of additional literatures. We only included studies reporting the association between all-cause mortality and muscle mass measured by computerized tomography (CT), dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) or bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) reported as “reduced lean mass” (ie, lean mass was treated as continuous variable) or “low lean mass” (ie, lean mass was treated as a binary variable, low vs normal lean mass). The pre-specified exclusion criteria were as follows: non-human studies; studies using the following exposures: other surrogates of muscle mass (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], creatinine level, or lean mass ratio), anthropometric measurement of muscle mass (such as skinfold measurement, mid-arm circumference, etc), rate of change in muscle mass, sarcopenia defined using composite criteria (low lean mass in combination with muscle strength and physical performance); and studies with insufficient data for meta-analysis (studies reporting lean mass as continuous variable without providing standard deviation [SD] for standardized hazard ratio [HR] calculation and studies providing P-values only). Notably, although mid-arm muscle area was considered an acceptable assessment of muscle mass in cancer cachexia [6], the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) commented that this method is prone to error and it is not recommended for routine use in the diagnosis of sarcopenia [5].

The PRISMA guideline was followed when evaluating search results. Each paper was screened by title and abstract for eligibility independently by 3 investigators (G.K.L, M.C, C.L.C). Any discrepancy was resolved by consensus. Data extraction was performed by 2 investigators (G.K.L and M.C) and cross-checked by a third investigator (G.H.L). The following information was recorded for each study: first author’s name, year of publication, study design, population, sex, ethnicity, health status, median or mean age, follow-up duration, source of lean mass, types of lean mass, lean mass unit, cut-off definition of sarcopenia, HR with associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and P-values for overall survival. HR and 95% CI were obtained from the fully-adjusted model if available. Otherwise, the crude model would be used. We contacted the corresponding authors if any of the required information was unclear in the article, and the paper was included when the relevant information was provided. Additionally, quality appraisal was done using a modified Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) by J.M and cross-checked by G.K.L (Supplementary Table 1). A modified NOS was applied because some questions were not applicable in the current study, such as selection of non-exposed cohort, demonstration that outcome of interest (ie, mortality in the current study) was not present at start of the study. In the current meta-analysis, studies of good quality were defined as 2 stars in selection domain AND 1/2 stars in comparability domain AND 1/2 stars in outcome/exposure domain; studies of fair quality were defined as 1 star in selection domain AND 1/2 stars in comparability domain AND 1/2 stars in outcome/exposure domain, and poor quality was defined as studies not meeting the criteria of good or fair quality. Any discrepancy in the data extraction and quality appraisal was addressed by discussion and consensus, with involvement of another author if necessary.

We attempted to identify and exclude duplicate data from research studies presented in separate publications. For cases in which we identified multiple studies with duplicated or overlapping data (by population, time and place), we selected the study with the longest follow-up time. When these studies had the same follow-up time, the study with the largest sample size was selected. If lean mass was measured at different sites in the same cohort, we selected the lean mass data based on the following order: whole body lean mass > appendicular lean mass > skeletal muscle > psoas muscle. If various muscle mass indices were used, the index was selected according to the following order: lean mass/height2 > lean mass/BMI > lean mass only. For various low lean mass cut-offs in cancer, the result was selected according to the following order: Martin > Prado > Optimal stratification > cut-off based on median of study population.

2.2. Data analysis

For studies with lean mass as a continuous variable, data could not be directly combined because different units of lean mass were used in different studies. Therefore, in order to combine the estimates across different studies, HR and 95% CI were expressed in standardized units [14] (per SD decrease in lean mass). For studies using lean mass as a binary cut-off, high lean mass was used as reference. The HR and 95% CI of each study were entered into Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan, Cochrane, United Kingdom) by G.K.L and cross-checked by P.C.A. If there was mismatch in 95% CI between the calculated values in Revman and those reported in the study publication, either upper or lower 95% CI was chosen as reference according to the calculated P-value in Revman, with the one with a P-value closest to the P-value reported in the study chosen. If numeric HR and/or 95% CI were not available in the literature, these were calculated based on beta, SE, and/or P-value provided in the literature.

All statistical analyses were performed using RevMan. The pooled HR and corresponding 95% CI were estimated using a random-effect model. Publication bias was appraised using funnel plots to test for asymmetry. We used the I2 statistic to evaluate the proportion of total variation in the study estimates which was due to heterogeneity.

3. Results

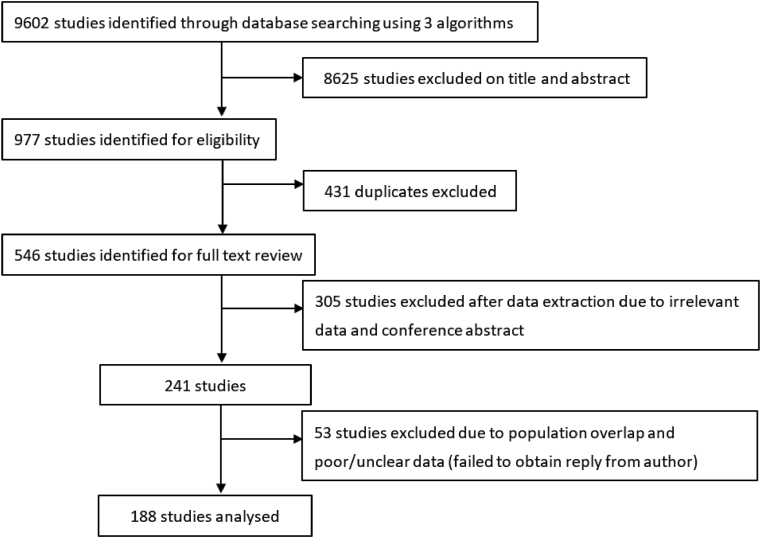

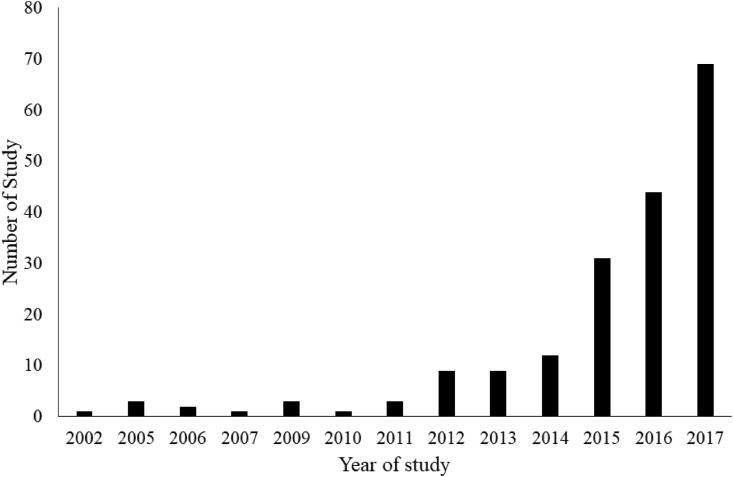

We identified 9,602 articles, of which 977 met the inclusion criteria. After excluding 431 duplicate studies, 546 full-text articles were retrieved. We excluded another 358 articles due to the irrelevant data, population overlap, poor/unclear data, or the articles were conference abstracts without available details. A total of 188 studies were included in the current meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Detailed characteristics of included studies are provided in Supplementary Tables 2–5. The number of studies by publication year (including those first published online) is shown in Fig. 2, and the number of studies increased continuously over time. Among the 188 included articles, 104, 81, and 3 of them were respectively classified as good-, fair-, and poor-quality studies (Supplementary Table 6).

Fig. 1.

Study attrition diagram.

Fig. 2.

Number of studies by publication year included in the meta-analysis.

Data from a total of 98 468 people were included in the meta-analysis (Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). The association of sarcopenia with mortality was most studied in cancer patients (n = 100) [[15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114]], followed by people with renal diseases (n = 21) [[115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135]], liver diseases (n = 18) [[136], [137], [138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153]], elderly (n = 16) [[154], [155], [156], [157], [158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168], [169]], people with cardiovascular diseases (n = 11) [[170], [171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180]], lung diseases (n = 11) [[181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191]], and other diseases (n = 11) [[192], [193], [194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202]]. For the method used to measure lean mass (Table 1, Supplementary Table 3), computed tomography (CT) was the most used modality (n = 138) [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114],[133], [134], [135],[138], [139], [140], [141], [142], [143], [144], [145], [146], [147], [148], [149], [150], [151], [152], [153],[171], [172], [173], [174], [175], [176], [177], [178], [179], [180],[188], [189], [190], [191],[194], [195], [196], [197], [198], [199], [200], [201], [202]], followed by BIA (n = 29) [[15], [16], [17], [18],[115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126],136,137,[154], [155], [156], [157],[181], [182], [183], [184], [185], [186], [187]], and DXA (n = 21) [19,[127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132],[158], [159], [160], [161], [162], [163], [164], [165], [166], [167], [168],170,192,193]. After excluding cancer-related studies in the calculation, CT remained the most commonly used method in assessing lean mass (n = 43), followed by BIA (n = 25) and DXA (n = 20). Majority (n = 120) of the studies used low lean mass as the exposure (Table 1, Supplementary Table 4). Fifty studies used reduced lean mass, while 18 studies investigated both low lean mass and reduced lean mass. After excluding cancer-related studies in the calculation, majority of the studies (n = 40) used reduced lean mass as exposure, 37 studies used low lean mass as exposure, while 11 studies examined both.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Subgroups | Number of studies | Sample size | Number of studies by measurement modality |

Number of studies by type of variables that lean mass was investigated |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIA | DXA | CT | Binary | Continuous | Both | |||

| Elderly | 16 | 19320 | 4(154–157) | 11(158–168) | 1(169) | 7(154, 158–163) | 7(157, 164–169) | 2(155, 156) |

| Cancer patients | 100 | 29511 | 4(15–18) | 1(19) | 95(20–114) | 83(15–17, 19–33, 35, 37–39, 41–45, 47, 48, 50–56, 58, 59, 62, 64–67, 69–72, 74–85, 87–89, 93–96, 98–114) | 10(18, 34, 36, 46, 49, 57, 60, 61, 68, 86) | 7(40, 63, 73, 90–92, 97) |

| People with cardiovascular diseases | 11 | 2793 | 0 | 1(170) | 10(171–180) | 4(171–174) | 6(170, 176–180) | 1(175) |

| People with liver diseases | 18 | 4356 | 2(136, 137) | 0 | 16(138–153) | 8(137, 138, 140, 141, 143–146) | 8(136, 147–153) | 2(139, 142) |

| People with lung diseases | 11 | 1792 | 7(181–187) | 0 | 4(188–191) | 4(181–183, 188) | 6(184–187, 190, 191) | 1(189) |

| People with renal diseases | 21 | 30042 | 12(115–126) | 6(127–132) | 3(133–135) | 9(115–117, 119, 121, 127, 128, 130, 133) | 9(122–126, 131, 132, 134, 135) | 3(118, 120, 129) |

| People with other diseases | 11 | 10654 | 0 | 2(192, 193) | 9(194–202) | 5(192, 195, 197–199) | 4(193, 200–202) | 2(194, 196) |

| Total | 188 | 98468 | 29 | 21 | 138 | 120 | 50 | 18 |

Among studies conducted in cancer populations, 95 of them studied CT-measured lean mass with mortality (Table 2). The most frequently studied cancer type was gastrointestinal cancer (n = 21), followed by liver and intrahepatic bile duct (n = 20), urinary tract (n = 13), pancreatic (n = 10), lung (n = 8), ovarian and endometrial (n = 7), multiple (n = 5), hematopoietic (n = 4), breast (n = 3), bile duct (n = 2), head and neck (n = 1), and prostate (n = 1) cancer. The most frequently studied lean mass index was L3 skeletal muscle index (n = 70), followed by L3 psoas index (n = 11) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories of cancer studies measuring muscle using computed tomography and the muscle indices used in the analysis.

| Cancer category | Total | L3 Skeletal Muscle Index | L3 Psoas Index | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile duct (excludes intrahepatic) | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Breast | 3 | 3 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 21 | 18 | 3 | |

| Head and neck | 1 | 1 | ||

| Hematopoietic | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 20 | 15 | 2 | 3 |

| Lung | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Ovarian and endometria | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Pancreatic | 10 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Prostate | 1 | 1 | ||

| Urinary tract | 13 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| Multiple |

5 |

5 |

||

| Overall | 95 | 70 | 11 | 14 |

In defining low lean mass in cancer studies (Table 3, Supplementary Table 4), threshold suggested by Martin et al was the most often used (n = 20), followed by Prado et al (n = 15), and international consensus of cancer cachexia (n = 8). Other definitions were mostly derived from different statistical methods based on the study cohort, such as optimal stratification, ROC, median, etc.

Table 3.

Cutoff definition of low lean mass in cancer studies.

| Cutoff | n |

|---|---|

| Martin | 20 |

| Prado | 15 |

| International consensus of cancer cachexia | 8 |

| Other cohort cut-offs | 7 |

| Optimal stratification | 10 |

| ROC | 8 |

| Quantiles/percentiles | 7 |

| Median | 8 |

| Others |

7 |

| Total | 90 |

4. Discussion

In this study involving 188 studies and 98 468 participants from 34 countries, we examined the associations of lean mass with all-cause mortality across a wide range of healthy people and patients, across different measurement modalities, and various definition of sarcopenia. As we can see the number of studies in relation to lean mass and mortality has increased continuously since 2002, this is therefore a timely comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between lean mass and mortality, especially when efforts are being put in the definition of sarcopenia.

Although sarcopenia is a well-recognized issue in the elderly population, this systematic review and meta-analysis found that only 16 out of 188 studies were conducted in the elderly population. On the other hand, more than half (n = 100; 53.2%) of the studies were conducted in patients with cancer. This could be explained by the clinical management of cancer as CT is routinely used to monitor disease progression in cancer patients. Thus, lean mass measurement can be retrieved from existing CT data in many studies, which facilitated the research of sarcopenia in cancer patients. This also explained why CT was the most often used imaging modality in evaluating lean mass (138 out of 188 studies). However, given the high radiation dose of CT, it is not justifiable to use CT purely for sarcopenia research. On the other hand, DXA has a much lower dose of radiation, while BIA is radiation-free. Therefore, these DXA and BIA may be more suitable for lean mass measurement in sarcopenia research in non-cancer patients.

For DXA and BIA, sarcopenia is usually defined using appendicular lean mass, as suggested by consensus. On the other hand, the most common skeletal site in defining sarcopenia in cancer was cross-sectional area (CSA) of muscles at the L3 vertebral level. Two indices can be derived from the muscles at the L3 vertebral level, namely L3 skeletal muscle index and L3 psoas index. L3 skeletal muscle index calculated the CSA of all muscles at the L3 vertebral level, whereas L3 psoas index calculated the CSA of psoas muscle only at the L3 vertebral level. These 2 indices were said to be interchangeable, but whether these indices had similar association with mortality is largely unknown.

Lean mass was commonly analyzed as a binary trait, ie, low vs normal lean mass. There were several operational definitions of low lean mass, such as the International Working Group on Sarcopenia [203], Society of Sarcopenia, Cachexia and Wasting Disorders [204], FNIH [205], and European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [5]. Recently, consensus by EWGSOP was updated (known as EWGSOP2) [7], and such update was found to affect study result slightly [206]. It is therefore important to have a consensus on the definition, so that the findings could be compared across studies. Conversely, since there was no consensus on the cut-off point used for defining low lean mass or sarcopenia in cancer patients, many different methods were used to define sarcopenia. The definition provided by Martin et al [207] and Prado et al [208] were most often used. Optimal stratification [209], which defines sarcopenia based on the most significant cut-off point using log rank test, is the third most commonly used method. This is similar to the ROC method, which defines the optimal cut-off point using Youden’s index. However, these cut-off points are expected to be study-specific, and may over-estimate the effect if there is no validation study. These methods (optimal stratification or ROC) may be useful in deriving a cut-off point in a specific population, while the generalizability of these findings is largely unknown.

Our current study aims to provide insight on these issues, especially to address a recent recommendation by the Sarcopenia Definitions and Outcomes Consortium (SDOC). In the latest analyses by SDOC, they found that lean mass measured by DXA was not a good predictor of multiple adverse outcomes in the elderly [8], thus proposing inclusion of gait speed and grip strength, but not lean mass, in the definition of sarcopenia. In fact, low lean mass (defined as ALM/ht2 < 5.45 and 7.26 in women and men, respectively) was consistently associated with increased risk of mortality in both women and men in their study [8]. Therefore, whether lean mass should be excluded from use in the definition of sarcopenia remains an open question, while our current study has provided further evidence in this aspect.

Although the current study has evaluated the association of different parameters of lean mass on mortality, we acknowledge that our analyses are insufficient to address these questions directly. For example, the best way to compare the usefulness of different modalities, cut-off points, or site of muscle measurements is to compare these differences directly in the same study. The current analysis was only able to summarize evidences from multiple studies, in which the difference in estimates could be due to the study design and population, instead of the intrinsic difference between the modalities, cut-off points, and site of muscle measurement under investigation. However, only a very limited number of studies were conducted for direct comparison. It is important to have an international collaboration in answering these questions directly, which is essential for developing clinical guidelines of sarcopenia, not only for the elderly, but also for patients with different diseases. In addition, due to tremendous work of the current meta-analysis, we only updated the literature until the end of 2017. We understand there were publications on sarcopenia and mortality published from 2018 to 2020, however the number of studies included in the current study should enable us to come up with a conclusion on whether lean mass is associated with mortality. We hope that the current work will provide a useful resource to the field for future research and guideline development.

In conclusion, this series of meta-analysis of lean mass and mortality could provide insight and evidence on the relationship between lean mass and mortality in all directions, which may be useful for further study and guideline development, especially when there are growing efforts to move from risk assessment to intervention of sarcopenia [9].

CRediT author statement

Ching-Lung Cheung: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Grace Koon-Yee Lee: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Philip Chun-Ming Au: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Gloria Hoi-Yee Li: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Marcus Chan: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Hang-Long Li: Writing - Review & Editing. Bernard Man-Yung Cheung: Writing - Review & Editing. Ian Chi-Kei Wong: Writing - Review & Editing. Victor Ho-Fun Lee: Writing - Review & Editing. James Mok: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. Benjamin Hon-Kei Yip: Writing - Review & Editing. Kenneth King-Yip Cheng: Writing - Review & Editing. Chih-Hsing Wu: Writing - Review & Editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

ORCID Ching-Lung Cheung: 0000-0002-6233-9144. Grace Koon-Yee Lee: 0000-0002-9362-4319. Philip Chun-Ming Au: 0000-0002-0736-4726. Gloria Hoi-Yee Li: 0000-0003-0275-2356. Marcus Chan: 0000-0001-6072-7648. Hang-Long Li: 0000-0002-2294-2977. Bernard Man-Yung Cheung: 0000-0001-9106-7363. Ian Chi-Kei Wong: 0000-0001-8242-0014. Victor Ho-Fun Lee: 0000-0002-6283-978X. James Mok: 0000-0003-1974-0829. Benjamin Hon-Kei Yip: 0000-0002-4749-7611. Kenneth King-Yip Cheng: 0000-0002-7274-0839. Chih-Hsing Wu: 0000-0002-0504-2053.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Korean Society of Osteoporosis.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afos.2021.01.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Schnyder S., Handschin C. Skeletal muscle as an endocrine organ: PGC-1α, myokines and exercise. Bone. 2015;80:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung C.L., Lam K.S., Cheung B.M. Evaluation of cutpoints for low lean mass and slow gait speed in predicting death in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:90–95. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee D.H., Keum N., Hu F.B., Orav E.J., Rimm E.B., Willett W.C. Predicted lean body mass, fat mass, and all cause and cause specific mortality in men: prospective US cohort study. BMJ. 2018:362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L.K., Liu L.K., Woo J., Assantachai P., Auyeung T.W., Bahyah K.S. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Baeyens J.P., Bauer J.M., Boirie Y., Cederholm T., Landi F. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European working group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon K., Strasser F., Anker S.D., Bosaeus I., Bruera E., Fainsinger R.L. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz-Jentoft A.J., Bahat G., Bauer J., Boirie Y., Bruyere O., Cederholm T. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48:601. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cawthon P.M., Manini T., Patel S.M., Newman A., Travison T., Kiel D.P. Putative cut-points in sarcopenia components and incident adverse health outcomes: an SDOC Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1429–1437. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesari M., Kuchel G.A. Role of sarcopenia definition and diagnosis in clinical care: moving from risk assessment to mechanism-guided interventions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1406–1409. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boshier P.R., Heneghan R., Markar S.R., Baracos V.E., Low D.E. Assessment of body composition and sarcopenia in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2018;31:1–11. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim G., Kang S.H., Kim M.Y., Baik S.K. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in patients with liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu P., Hao Q., Hai S., Wang H., Cao L., Dong B. Sarcopenia as a predictor of all-cause mortality among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2017;103:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shachar S.S., Williams G.R., Muss H.B., Nishijima T.F. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur J Canc. 2016;57:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens S.L., Wood S., Koshiaris C., Law K., Glasziou P., Stevens R.J. Blood pressure variability and cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:i4098. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez M., Pastore C., Orlandi S., Heymsfield S. Obesity paradox in cancer: new insights provided by body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:999–1005. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pérez Camargo D., Allende Pérez S., Verastegui Avilés E., Rivera Franco M., Meneses García A., Herrera Gómez Á. Assessment and impact of phase angle and sarcopenia in palliative cancer patients. Nutr Canc. 2017;69:1227–1233. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1367939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stobäus N., Küpferling S., Lorenz M., Norman K. Discrepancy between body surface area and body composition in cancer. Nutr Canc. 2013;65:1151–1156. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.828084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui D., Bansal S., Morgado M., Dev R., Chisholm G., Bruera E. Phase angle for prognostication of survival in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings. Cancer. 2014;120:2207–2214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villasenor A., Ballard-Barbash R., Baumgartner K., Baumgartner R., Bernstein L., McTiernan A. Prevalence and prognostic effect of sarcopenia in breast cancer survivors: the HEAL Study. J Cancer Surv. 2012;6:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0234-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amini N., Spolverato G., Gupta R., Margonis G., Kim Y., Wagner D. Impact total psoas volume on short- and long-term outcomes in patients undergoing curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a new tool to assess sarcopenia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1593–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2835-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoun S., Lanoy E., Iacovelli R., Albiges-Sauvin L., Loriot Y., Merad-Taoufik M. Skeletal muscle density predicts prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapies. Cancer. 2013;119:3377–3384. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antoun S., Bayar A., Ileana E., Laplanche A., Fizazi K., di Palma M. High subcutaneous adipose tissue predicts the prognosis in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients in post chemotherapy setting. Eur J Canc. 2015;51:2570–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Begini P, Gigante E, Antonelli G, Carbonetti F, Iannicelli E, Anania G, et al. Sarcopenia predicts reduced survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma at first diagnosis. Ann Hepatol 16:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Black D., Mackay C., Ramsay G., Hamoodi Z., Nanthakumaran S., Park K. Prognostic value of computed tomography: measured parameters of body composition in primary operable gastrointestinal cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2241–2251. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5829-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blauwhoff-Buskermolen S., Versteeg K.S., de van der Schueren M.A., den Braver N.R., Berkhof J., Langius J.A. Loss of muscle mass during chemotherapy is predictive for poor survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1339–1344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.6043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boer B.C., de Graaff F., Brusse-Keizer M., Bouman D.E., Slump C.H., Slee-Valentijn M. Skeletal muscle mass and quality as risk factors for postoperative outcome after open colon resection for cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;6:1117–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowden J., Williams L., Simms A., Price A., Campbell S., Fallon M. Prediction of 90 day and overall survival after chemoradiotherapy for lung cancer: role of performance status and body composition. Clin Oncol. 2017;29:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bronger H., Hederich P., Hapfelmeier A., Metz S., Noël P., Kiechle M. Sarcopenia in advanced serous ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Canc. 2017;27:223–232. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caan B.J., Meyerhardt J.A., Kroenke C.H., Alexeeff S., Xiao J., Weltzien E. Explaining the obesity paradox: the association between body composition and colorectal cancer survival (C-SCANS Study) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1008–1015. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho K., Park H., Oh D., Kim T., Lee K., Han S. Skeletal muscle depletion predicts survival of patients with advanced biliary tract cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:79441–79452. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi M., Oh S., Lee I., Oh S., Won D. Sarcopenia is negatively associated with long-term outcomes in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;9:53–59. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi Y., Oh D.Y., Kim T.Y., Lee K.H., Han S.W., Im S.A. Skeletal muscle depletion predicts the prognosis of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer undergoing palliative chemotherapy, independent of body mass index. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coelen R.J., Wiggers J.K., Nio C.Y., Besselink M.G., Busch O.R., Gouma D.J. Preoperative computed tomography assessment of skeletal muscle mass is valuable in predicting outcomes following hepatectomy for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:520–528. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper A.B., Slack R., Fogelman D., Holmes H.M., Petzel M., Parker N. Characterization of anthropometric changes that occur during neoadjuvant therapy for potentially resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2416–2423. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4285-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dalal S., Hui D., Bidaut L., Lem K., Del Fabbro E., Crane C. Relationships among body mass index, longitudinal body composition alterations, and survival in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer receiving chemoradiation: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;44:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delitto D., Judge S.M., George T.J., Jr., Sarosi G.A., Thomas R.M., Behrns K.E. A clinically applicable muscular index predicts long-term survival in resectable pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2017;161:930–938. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deluche E., Leobon S., Desport J., Venat-Bouvet L., Usseglio J., Tubiana-Mathieu N. Impact of body composition on outcome in patients with early breast cancer. Support Care Canc. 2018;26:861–868. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ebadi M., Martin L., Ghosh S., Field C., Lehner R., Baracos V. Subcutaneous adiposity is an independent predictor of mortality in cancer patients. Br J Canc. 2017;117:148–155. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujiwara N., Nakagawa H., Kudo Y., Tateishi R., Taguri M., Watadani T. Sarcopenia, intramuscular fat deposition, and visceral adiposity independently predict the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;63:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukushima H., Yokoyama M., Nakanishi Y., Tobisu K., Koga F. Sarcopenia as a prognostic biomarker of advanced urothelial carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukushima H., Nakanishi Y., Kataoka M., Tobisu K., Koga F. Prognostic significance of sarcopenia in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 2016;195:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukushima H., Nakanishi Y., Kataoka M., Tobisu K., Koga F. Prognostic significance of sarcopenia in upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients treated with radical nephroureterectomy. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2213–2220. doi: 10.1002/cam4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Go S., Park M., Song H., Kim H., Kang M., Lee H. Prognostic impact of sarcopenia in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grossberg A.J., Chamchod S., Fuller C.D., Mohamed A.S., Heukelom J., Eichelberger H. Association of body composition with survival and locoregional control of radiotherapy-treated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:782–789. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grotenhuis B.A., Shapiro J., van Adrichem S., de Vries M., Koek M., Wijnhoven B.P. Sarcopenia/muscle mass is not a prognostic factor for short- and long-term outcome after esophagectomy for cancer. World J Surg. 2016;40:2698–2704. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3603-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu W., Zhu Y., Wang H., Zhang H., Shi G., Liu X. Prognostic value of components of body composition in patients treated with targeted therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective case series. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu W., Wu J., Liu X., Zhang H., Shi G., Zhu Y. Early skeletal muscle loss during target therapy is a prognostic biomarker in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7587. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ha Y., Kim D., Han S., Chon Y., Lee Y., Kim M. Sarcopenia predicts prognosis in patients with newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma, independent of tumor stage and liver function. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;5:843–851. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harimoto N., Shirabe K., Yamashita Y., Ikegami T., Yoshizumi T., Soejima Y. Sarcopenia as a predictor of prognosis in patients following hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1523–1530. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harimoto N., Yoshizumi T., Shimokawa M., Sakata K., Kimura K., Itoh S. Sarcopenia is a poor prognostic factor following hepatic resection in patients aged 70 years and older with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:1247–1255. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hervochon R., Bobbio A., Guinet C., Mansuet-Lupo A., Rabbat A., Regnard J.F. Body mass index and total psoas area affect outcomes in patients undergoing pneumonectomy for cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higashi T., Hayashi H., Taki K., Sakamoto K., Kuroki H., Nitta H. Sarcopenia, but not visceral fat amount, is a risk factor of postoperative complications after major hepatectomy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:310–319. doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiraoka A., Hirooka M., Koizumi Y., Izumoto H., Ueki H., Kaneto M. Muscle volume loss as a prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with sorafenib. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:558–565. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iritani S., Imai K., Takai K., Hanai T., Ideta T., Miyazaki T. Skeletal muscle depletion is an independent prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:323–332. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ishihara H., Kondo T., Omae K., Takagi T., Iizuka J., Kobayashi H. Sarcopenia and the Modified Glasgow Prognostic Score are significant predictors of survival among patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who are receiving first-line sunitinib treatment. Target Oncol. 2016;11:605–617. doi: 10.1007/s11523-016-0430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishii N., Iwata Y., Nishikawa H., Enomoto H., Aizawa N., Ishii A. Effect of pretreatment psoas muscle mass on survival for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer undergoing systemic chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:6059–6065. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jung H.W., Kim J.W., Kim J.Y., Kim S.W., Yang H.K., Lee J.W. Effect of muscle mass on toxicity and survival in patients with colon cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. Support Care Canc. 2015;23:687–694. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2418-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamachi S., Mizuta T., Otsuka T., Nakashita S., Ide Y., Miyoshi A. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative treatment. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:201–208. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim E., Kim Y., Park I., Ahn H., Cho E., Jeong Y. Prognostic significance of CT-determined sarcopenia in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1795–1799. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura M., Naito T., Kenmotsu H., Taira T., Wakuda K., Oyakawa T. Prognostic impact of cancer cachexia in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Canc. 2015;23:1699–1708. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kinsey C.M., San Jose Estepar R., van der Velden J., Cole B.F., Christiani D.C., Washko G.R. Lower pectoralis muscle area is associated with a worse overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:38–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kudou K., Saeki H., Nakashima Y., Edahiro K., Korehisa S., Taniguchi D. Prognostic significance of sarcopenia in patients with esophagogastric junction cancer or upper gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1804–1810. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5811-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar A., Moynagh M.R., Multinu F., Cliby W.A., McGree M.E., Weaver A.L. Muscle composition measured by CT scan is a measurable predictor of overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuroki L.M., Mangano M., Allsworth J.E., Menias C.O., Massad L.S., Powell M.A. Pre-operative assessment of muscle mass to predict surgical complications and prognosis in patients with endometrial cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:972–979. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lanic H., Kraut-Tauzia J., Modzelewski R., Clatot F., Mareschal S., Picquenot J. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:817–823. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.816421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levolger S., van Vledder M.G., Muslem R., Koek M., Niessen W.J., de Man R.A. Sarcopenia impairs survival in patients with potentially curable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2015;112:208–213. doi: 10.1002/jso.23976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Levolger S., van Vledder M., Alberda W., Verhoef C., de Bruin R., IJzermans J. Muscle wasting and survival following pre-operative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal carcinoma. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1728–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu J., Motoyama S., Sato Y., Wakita A., Kawakita Y., Saito H. Decreased skeletal muscle mass after neoadjuvant therapy correlates with poor prognosis in patients with esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:6677–6685. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lodewick T., van Nijnatten T., van Dam R., van Mierlo K., Dello S., Neumann U. Are sarcopenia, obesity and sarcopenic obesity predictive of outcome in patients with colorectal liver metastases? HPB (Oxford) 2015;17:438–446. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malietzis G., Currie A.C., Athanasiou T., Johns N., Anyamene N., Glynne-Jones R. Influence of body composition profile on outcomes following colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103:572–580. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martin L., Birdsell L., Macdonald N., Reiman T., Clandinin M., McCargar L. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1539–1547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McSorley S., Black D., Horgan P., McMillan D. The relationship between tumour stage, systemic inflammation, body composition and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meza-Junco J., Montano-Loza A.J., Baracos V.E., Prado C.M., Bain V.G., Beaumont C. Sarcopenia as a prognostic index of nutritional status in concurrent cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:861–870. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318293a825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyake M., Morizawa Y., Hori S., Marugami N., Iida K., Ohnishi K. Integrative assessment of pretreatment inflammation-, nutrition-, and muscle-based prognostic markers in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Oncology. 2017;93:259–269. doi: 10.1159/000477405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Miyamoto Y., Baba Y., Sakamoto Y., Ohuchi M., Tokunaga R., Kurashige J. Sarcopenia is a negative prognostic factor after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:2663–2668. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Naganuma A., Hoshino T., Suzuki Y., Uehara D., Kudo T., Ishihara H. Association between skeletal muscle depletion and sorafenib treatment in male patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Acta Med Okayama. 2017;71:291–299. doi: 10.18926/AMO/55305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakamura N., Hara T., Shibata Y., Matsumoto T., Nakamura H., Ninomiya S. Sarcopenia is an independent prognostic factor in male patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:2043–2053. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nault J.C., Pigneur F., Nelson A.C., Costentin C., Tselikas L., Katsahian S. Visceral fat area predicts survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ninomiya G., Fujii T., Yamada S., Yabusaki N., Suzuki K., Iwata N. Clinical impact of sarcopenia on prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;39:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nishikawa H., Nishijima N., Enomoto H., Sakamoto A., Nasu A., Komekado H. Prognostic significance of sarcopenia in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing sorafenib therapy. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:1637–1647. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okumura S., Kaido T., Hamaguchi Y., Fujimoto Y., Masui T., Mizumoto M. Impact of preoperative quality as well as quantity of skeletal muscle on survival after resection of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2015;157:1088–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Okumura S., Kaido T., Hamaguchi Y., Fujimoto Y., Kobayashi A., Iida T. Impact of the preoperative quantity and quality of skeletal muscle on outcomes after resection of extrahepatic biliary malignancies. Surgery. 2016;159:821–833. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Okumura S., Kaido T., Hamaguchi Y., Kobayashi A., Shirai H., Fujimoto Y. Impact of skeletal muscle mass, muscle quality, and visceral adiposity on outcomes following resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1037–1045. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5668-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Okumura S., Kaido T., Hamaguchi Y., Kobayashi A., Shirai H., Yao S. Visceral adiposity and sarcopenic visceral obesity are associated with poor prognosis after resection of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:3732–3740. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6077-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paireder M., Asari R., Kristo I., Rieder E., Tamandl D., Ba-Ssalamah A. Impact of sarcopenia on outcome in patients with esophageal resection following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for esophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parsons H., Baracos V., Dhillon N., Hong D., Kurzrock R. Body composition, symptoms, and survival in advanced cancer patients referred to a phase I service. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peng P., Hyder O., Firoozmand A., Kneuertz P., Schulick R.D., Huang D. Impact of sarcopenia on outcomes following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1478–1486. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1923-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peyton C.C., Heavner M.G., Rague J.T., Krane L.S., Hemal A.K. Does sarcopenia impact complications and overall survival in patients undergoing radical nephrectomy for stage iii and iv kidney cancer? J Endourol. 2016;30:229–236. doi: 10.1089/end.2015.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Psutka S.P., Carrasco A., Schmit G.D., Moynagh M.R., Boorjian S.A., Frank I. Sarcopenia in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy: impact on cancer-specific and all-cause mortality. Cancer. 2014;120:2910–2918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Psutka S.P., Boorjian S.A., Moynagh M.R., Schmit G.D., Frank I., Carrasco A. Mortality after radical cystectomy: impact of obesity versus adiposity after adjusting for skeletal muscle wasting. J Urol. 2015;193:1507–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.11.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Psutka S.P., Boorjian S.A., Moynagh M.R., Schmit G.D., Costello B.A., Thompson R.H. Decreased skeletal muscle mass is associated with an increased risk of mortality after radical nephrectomy for localized renal cell cancer. J Urol. 2016;195:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rier H.N., Jager A., Sleijfer S., van Rosmalen J., Kock M.C., Levin M.D. Low muscle attenuation is a prognostic factor for survival in metastatic breast cancer patients treated with first line palliative chemotherapy. Breast. 2017;31:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rollins K., Tewari N., Ackner A., Awwad A., Madhusudan S., Macdonald I. The impact of sarcopenia and myosteatosis on outcomes of unresectable pancreatic cancer or distal cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rutten I.J., van Dijk D.P., Kruitwagen R.F., Beets-Tan R.G., Olde Damink S.W., van Gorp T. Loss of skeletal muscle during neoadjuvant chemotherapy is related to decreased survival in ovarian cancer patients. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:458–466. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rutten I.J., Ubachs J., Kruitwagen R.F., van Dijk D.P., Beets-Tan R.G., Massuger L.F. The influence of sarcopenia on survival and surgical complications in ovarian cancer patients undergoing primary debulking surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sakurai K., Kubo N., Tamura T., Toyokawa T., Amano R., Tanaka H. Adverse effects of low preoperative skeletal muscle mass in patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2712–2719. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shachar S., Deal A., Weinberg M., Nyrop K., Williams G., Nishijima T. Skeletal muscle measures as predictors of toxicity, hospitalization, and survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving taxane-based chemotherapy. Clin Canc Res. 2017;23:658–665. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma P., Zargar-Shoshtari K., Caracciolo J., Fishman M., Poch M., Pow-Sang J. Sarcopenia as a predictor of overall survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shoji F., Matsubara T., Kozuma Y., Haratake N., Akamine T., Takamori S. Relationship between preoperative sarcopenia status and immuno-nutritional parameters in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:6997–7003. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stene G., Helbostad J., Amundsen T., Sørhaug S., Hjelde H., Kaasa S. Changes in skeletal muscle mass during palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:340–348. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.953259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Takagi K., Yagi T., Yoshida R., Shinoura S., Umeda Y., Nobuoka D. Sarcopenia and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status in the assessment of outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing hepatectomy. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:363–370. doi: 10.18926/AMO/54594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takeoka Y., Sakatoku K., Miura A., Yamamura R., Araki T., Seura H. Prognostic effect of low subcutaneous adipose tissue on survival outcome in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tamandl D., Paireder M., Asari R., Baltzer P., Schoppmann S., Ba-Ssalamah A. Markers of sarcopenia quantified by computed tomography predict adverse long-term outcome in patients with resected oesophageal or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:1359–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tan B., Birdsell L., Martin L., Baracos V., Fearon K. Sarcopenia in an overweight or obese patient is an adverse prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Clin Canc Res. 2009;15:6973–6979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Thoresen L., Frykholm G., Lydersen S., Ulveland H., Baracos V., Prado C. Nutritional status, cachexia and survival in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma. Different assessment criteria for nutritional status provide unequal results. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsukioka T., Nishiyama N., Izumi N., Mizuguchi S., Komatsu H., Okada S. Sarcopenia is a novel poor prognostic factor in male patients with pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47:363–368. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Valero V., 3rd, Amini N., Spolverato G., Weiss M.J., Hirose K., Dagher N.N. Sarcopenia adversely impacts postoperative complications following resection or transplantation in patients with primary liver tumors. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:272–281. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2680-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van Vledder M., Levolger S., Ayez N., Verhoef C., Tran T., Ijzermans J. Body composition and outcome in patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2012;99:550–557. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Veasey Rodrigues H., Baracos V., Wheler J., Parsons H., Hong D., Naing A. Body composition and survival in the early clinical trials setting. Eur J Canc. 2013;49:3068–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Voron T., Tselikas L., Pietrasz D., Pigneur F., Laurent A., Compagnon P. Sarcopenia impacts on short- and long-term results of hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2015;261:1173–1183. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zakaria H.M., Basheer A., Boyce-Fappiano D., Elibe E., Schultz L., Lee I. Application of morphometric analysis to patients with lung cancer metastasis to the spine: a clinical study. Neurosurg Focus. 2016;41:E12. doi: 10.3171/2016.5.FOCUS16152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zheng Z., Lu J., Zheng C., Li P., Xie J., Wang J. A novel prognostic scoring system based on preoperative sarcopenia predicts the long-term outcome for patients after r0 resection for gastric cancer: experiences of a high-volume center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1795–1803. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhou G., Bao H., Zeng Q., Hu W., Zhang Q. Sarcopenia as a prognostic factor in hepatolithiasis-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients following hepatectomy: a retrospective study. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:18245–18254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhuang C.L., Huang D.D., Pang W.Y., Zhou C.J., Wang S.L., Lou N. Sarcopenia is an independent predictor of severe postoperative complications and long-term survival after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: analysis from a large-scale cohort. Medicine (Baltim) 2016;95:e3164. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dekker M.J.E., Marcelli D., Canaud B., Konings C.J.A.M., Leunissen K.M., Levin N.W. Unraveling the relationship between mortality, hyponatremia, inflammation and malnutrition in hemodialysis patients: results from the international MONDO initiative. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:779–784. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jin S., Lu Q., Su C., Pang D., Wang T. Shortage of appendicular skeletal muscle is an independent risk factor for mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37:78–84. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2016.00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kim J., Kim S., Oh J., Lee Y., Noh J., Kim H. Impact of sarcopenia on long-term mortality and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34:599–607. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2017.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kittiskulnam P., Chertow G.M., Carrero J.J., Delgado C., Kaysen G.A., Johansen K.L. Sarcopenia and its individual criteria are associated, in part, with mortality among patients on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2017;92:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lin T., Peng C., Hung S., Tarng D. Body composition is associated with clinical outcomes in patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018;93:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paudel K., Visser A., Burke S., Samad N., Fan S.L. Can bioimpedance measurements of lean and fat tissue mass replace subjective global assessments in peritoneal dialysis patients? J Ren Nutr. 2015;25:480–487. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Rosenberger J., Kissova V., Majernikova M., Straussova Z., Boldizsar J. Body composition monitor assessing malnutrition in the hemodialysis population independently predicts mortality. J Ren Nutr. 2014;24:172–176. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Abad S., Sotomayor G., Vega A., Perez de Jose A., Verdalles U., Jofre R. The phase angle of the electrical impedance is a predictor of long-term survival in dialysis patients. Nefrologia. 2011;31:670–676. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2011.Sep.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Barros A., Costa B.E., Mottin C.C., d’Avila D.O. Depression, quality of life, and body composition in patients with end-stage renal disease: a cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;38:301–306. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Vega A., Abad S., Macias N., Aragoncillo I., Santos A., Galan I. Low lean tissue mass is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with stages 4 and 5 non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10:170–175. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wilson F.P., Xie D., Anderson A.H., Leonard M.B., Reese P.P., Delafontaine P. Urinary creatinine excretion, bioelectrical impedance analysis, and clinical outcomes in patients with CKD: the CRIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:2095–2103. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03790414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wu H., Tseng S., Wang W., Chen H., Lee L. Association between obesity with low muscle mass and dialysis mortality. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1282–1291. doi: 10.1111/imj.13553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Androga L., Sharma D., Amodu A., Abramowitz M. Sarcopenia, obesity, and mortality in US adults with and without chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Honda H., Qureshi A., Axelsson J., Heimburger O., Suliman M., Barany P. Obese sarcopenia in patients with end-stage renal disease is associated with inflammation and increased mortality. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:633–638. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Isoyama N., Qureshi A.R., Avesani C.M., Lindholm B., Barany P., Heimburger O. Comparative associations of muscle mass and muscle strength with mortality in dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1720–1728. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10261013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kang S.H., Cho K.H., Park J.W., Do J.Y. Low appendicular muscle mass is associated with mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients: a single-center cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:1405–1410. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2017.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kakiya R., Shoji T., Tsujimoto Y., Tatsumi N., Hatsuda S., Shinohara K. Body fat mass and lean mass as predictors of survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;70:549–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nilsson E., Cao Y., Lindholm B., Ohyama A., Carrero J., Qureshi A. Pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A predicts survival in end-stage renal disease-confounding and modifying effects of cardiovascular disease, body composition and inflammation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:1776. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ishihara H., Kondo T., Omae K., Takagi T., Iizuka J., Kobayashi H. Sarcopenia predicts survival outcomes among patients with urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract undergoing radical nephroureterectomy: a retrospective multi-institution study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:136–144. doi: 10.1007/s10147-016-1021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fukasawa H., Kaneko M., Niwa H., Matsuyama T., Yasuda H., Kumagai H. Lower thigh muscle mass is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in elderly hemodialysis patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:64–69. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Locke J., Carr J., Nair S., Terry J., Reed R., Smith G. Abdominal lean muscle is associated with lower mortality among kidney waitlist candidates. Clin Transplant. 2017;31 doi: 10.1111/ctr.12911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nishikawa H., Enomoto H., Ishii A., Iwata Y., Miyamoto Y., Ishii N. Comparison of prognostic impact between the child-pugh score and skeletal muscle mass for patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrients. 2017;9:595. doi: 10.3390/nu9060595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Nishikawa H., Enomoto H., Iwata Y., Nishimura T., Iijima H., Nishiguchi S. Clinical utility of bioimpedance analysis in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:409–416. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Golse N., Bucur P., Ciacio O., Pittau G., Sa Cunha A., Adam R. A new definition of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2017;23:143–154. doi: 10.1002/lt.24671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Hanai T., Shiraki M., Ohnishi S., Miyazaki T., Ideta T., Kochi T. Rapid skeletal muscle wasting predicts worse survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2016;46:743–751. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jeon J.Y., Wang H.J., Ock S.Y., Xu W., Lee J.D., Lee J.H. Newly developed sarcopenia as a prognostic factor for survival in patients who underwent liver transplantation. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Masuda T., Shirabe K., Ikegami T., Harimoto N., Yoshizumi T., Soejima Y. Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2014;20:401–407. doi: 10.1002/lt.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Montano-Loza A., Angulo P., Meza-Junco J., Prado C., Sawyer M., Beaumont C. Sarcopenic obesity and myosteatosis are associated with higher mortality in patients with cirrhosis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7:126–135. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Nishikawa H., Enomoto H., Ishii A., Iwata Y., Miyamoto Y., Ishii N. Prognostic significance of low skeletal muscle mass compared with protein-energy malnutrition in liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:1042–1052. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Shirai H., Kaido T., Hamaguchi Y., Yao S., Kobayashi A., Okumura S. Preoperative low muscle mass has a strong negative effect on pulmonary function in patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation. Nutrition. 2018;45:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Tandon P., Ney M., Irwin I., Ma M.M., Gramlich L., Bain V.G. Severe muscle depletion in patients on the liver transplant wait list: its prevalence and independent prognostic value. Liver Transplant. 2012;18:1209–1216. doi: 10.1002/lt.23495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yadav A., Chang Y.H., Carpenter S., Silva A.C., Rakela J., Aqel B.A. Relationship between sarcopenia, six-minute walk distance and health-related quality of life in liver transplant candidates. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:134–141. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Carey E.J., Lai J.C., Wang C.W., Dasarathy S., Lobach I., Montano-Loza A.J. A multicenter study to define sarcopenia in patients with end-stage liver disease. Liver Transplant. 2017;23:625–633. doi: 10.1002/lt.24750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.DiMartini A., Cruz R., Dew M., Myaskovsky L., Goodpaster B., Fox K. Muscle mass predicts outcomes following liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2013;19:1172–1180. doi: 10.1002/lt.23724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Durand F., Buyse S., Francoz C., Laouenan C., Bruno O., Belghiti J. Prognostic value of muscle atrophy in cirrhosis using psoas muscle thickness on computed tomography. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1151–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kim T., Kim M., Sohn J., Kim S., Ryu J., Lim S. Sarcopenia as a useful predictor for long-term mortality in cirrhotic patients with ascites. J Kor Med Sci. 2014;29:1253–1259. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.9.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Sinclair M., Grossmann M., Angus P.W., Hoermann R., Hey P., Scodellaro T. Low testosterone as a better predictor of mortality than sarcopenia in men with advanced liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:661–667. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Terjimanian M.N., Harbaugh C.M., Hussain A., Olugbade K.O., Jr., Waits S.A., Wang S.C. Abdominal adiposity, body composition and survival after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2016;30:289–294. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Wang C.W., Feng S., Covinsky K.E., Hayssen H., Zhou L.Q., Yeh B.M. A comparison of muscle function, mass, and quality in liver transplant candidates: results from the functional assessment in liver transplantation study. Transplantation. 2016;100:1692–1698. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Chuang S.Y., Chang H.Y., Lee M.S., Chia-Yu Chen R., Pan W.H. Skeletal muscle mass and risk of death in an elderly population. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Genton L., Graf C., Karsegard V., Kyle U., Pichard C. Low fat-free mass as a marker of mortality in community-dwelling healthy elderly subjects. Age Ageing. 2013;42:33–39. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Graf C., Herrmann F., Spoerri A., Makhlouf A., Sørensen T., Ho S. Impact of body composition changes on risk of all-cause mortality in older adults. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1499–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Brown J.C., Harhay M.O., Harhay M.N. Appendicular lean mass and mortality among prefrail and frail older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:342–345. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0753-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Balogun S., Winzenberg T., Wills K., Scott D., Jones G., Aitken D. Prospective associations of low muscle mass and function with 10-year falls risk, incident fracture and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21:843–848. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0843-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Batsis J., Mackenzie T., Emeny R., Lopez-Jimenez F., Bartels S. Low lean mass with and without obesity, and mortality: results from the 1999-2004 National health and nutrition examination survey. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:1445–1451. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.De Buyser S.L., Petrovic M., Taes Y.E., Toye K.R., Kaufman J.M., Lapauw B. Validation of the FNIH sarcopenia criteria and SOF frailty index as predictors of long-term mortality in ambulatory older men. Age Ageing. 2016;45:602–608. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Hirani V., Blyth F., Naganathan V., Le Couteur D.G., Seibel M.J., Waite L.M. Sarcopenia is associated with incident disability, institutionalization, and mortality in community-dwelling older men: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Lee W., Liu L., Hwang A., Peng L., Lin M., Chen L. Dysmobility syndrome and risk of mortality for community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: the nexus of aging and body composition. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8785. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09366-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Moon J.H., Kim K.M., Kim J.H., Moon J.H., Choi S.H., Lim S. Predictive values of the new sarcopenia index by the foundation for the National institutes of health sarcopenia project for mortality among older Korean adults. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Kim Y.H., Kim K.I., Paik N.J., Kim K.W., Jang H.C., Lim J.Y. Muscle strength: a better index of low physical performance than muscle mass in older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:577–585. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Newman A.B., Kupelian V., Visser M., Simonsick E.M., Goodpaster B.H., Kritchevsky S.B. Strength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in the health, aging and body composition study cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:72–77. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Spahillari A., Mukamal K.J., DeFilippi C., Kizer J.R., Gottdiener J.S., Djousse L. The association of lean and fat mass with all-cause mortality in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Toss F., Wiklund P., Nordstrom P., Nordstrom A. Body composition and mortality risk in later life. Age Ageing. 2012;41:677–681. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Wijnhoven H.A., Snijder M.B., van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren M.A., Deeg D.J., Visser M. Region-specific fat mass and muscle mass and mortality in community-dwelling older men and women. Gerontology. 2012;58:32–40. doi: 10.1159/000324027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Cesari M., Pahor M., Lauretani F., Zamboni V., Bandinelli S., Bernabei R. Skeletal muscle and mortality results from the InCHIANTI Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:377–384. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Doehner W., Rauchhaus M., Ponikowski P., Godsland I.F., von Haehling S., Okonko D.O. Impaired insulin sensitivity as an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with stable chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Ikeno Y., Koide Y., Abe N., Matsueda T., Izawa N., Yamazato T. Impact of sarcopenia on the outcomes of elective total arch replacement in the elderlydagger. Eur J Cardio Thorac Surg. 2017;51:1135–1141. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Matsubara Y., Matsumoto T., Aoyagi Y., Tanaka S., Okadome J., Morisaki K. Sarcopenia is a prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61:945–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.10.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Mok M., Allende R., Leipsic J., Altisent O.A., Del Trigo M., Campelo-Parada F. Prognostic value of fat mass and skeletal muscle mass determined by computed tomography in patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Thurston B., Pena G., Howell S., Cowled P., Fitridge R. Low total psoas area as scored in the clinic setting independently predicts midterm mortality after endovascular aneurysm repair in male patients. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67:460–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Yamashita M., Kamiya K., Matsunaga A., Kitamura T., Hamazaki N., Matsuzawa R. Prognostic value of psoas muscle area and density in patients who undergo cardiovascular surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1652–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]