Abstract

The kidney tubules provide homeostasis by maintaining the external milieu that is critical for proper cellular function. Without homeostasis, there would be no heartbeat, no muscle movement, no thought, sensation, or emotion. The task is achieved by an orchestra of proteins, directly or indirectly involved in the tubular transport of water and solutes. Inherited tubulopathies are characterized by impaired function of one or more of these specific transport molecules. The clinical consequences can range from isolated alterations in the concentration of specific solutes in blood or urine to serious and life-threatening disorders of homeostasis. In this review, we focus on genetic aspects of the tubulopathies and how genetic investigations and kidney physiology have crossfertilized each other and facilitated the identification of these disorders and their molecular basis. In turn, clinical investigations of genetically defined patients have shaped our understanding of kidney physiology.

Keywords: kidney tubule, renal tubular acidosis, Bartter-s syndrome, tubulopathies, nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, magnesium wasting disorders, Water, Kidney Tubules, kidney, Urinary Tract Physiological Phenomena, Emotions, Homeostasis, Sensation, Kidney, Genomics, Series

Introduction

Homeostasis refers to the maintenance of the “milieu interieur,” which, as expressed by the physiologist Claude Bernard, is a “condition for a free and independent existence” (1). Simplified, homeostasis with regard to the kidney follows the principle of balance: “what goes in, must come out.” Our bodies must maintain balance of fluids, electrolytes, and acid-base despite great fluctuations from diet, metabolism, and environmental conditions. If laboring in high temperatures with limited fluid intake, water must be preserved; if the diet contains a high acid load, this needs to be excreted, and so on: the kidneys will adjust excretion of fluid and solutes so that the total body balance is preserved. Specifically, it is the kidney tubules that perform this critical task by adjusting reabsorption and secretion so that the final urine volume and composition matches the diet and environmental stressors. A whole array of transport proteins in the tubular epithelial cells is involved in this, and their importance becomes most apparent when one or more of them are defective. Collectively, these disorders are called kidney tubulopathies and a list of these is compiled in Table 1. The clinical consequences reflect the role of the affected transport protein: it can be isolated loss of specific solutes, which may even be of clinical benefit, considering, for instance, isolated renal glycosuria owing to mutations in the sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2. But they can also be devastating if global homeostasis is affected, impairing even the most basic physiologic functions, such as respiration (2).

Table 1.

List of inherited tubulopathies

| Disorder | Inheritance | Gene | Protein | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal tubule | ||||

| Fanconi renotubular syndrome 1 | AD | GATM | L-ARGININE:GLYCINE AMIDINOTRANSFERASE | #134600 |

| Fanconi renotubular syndrome 2 | AR | SLC34A1 | NaPi2A | #182309 |

| Fanconi renotubular syndrome 3 | AD | EHHADH | PBFE | #607037 |

| Fanconi renotubular syndrome 4 | AD | HNF4A | HNF-4 | #600281 |

| Fanconi Bickel syndrome | AR | SLC2A2 | GLUT-2 | #138160 |

| Dent disease type 1 | XLR | CLCN5 | CLC-5 | #300008 |

| Dent disease type 2/Lowe syndrome | XLR | OCRL | OCRL | #300535 |

| Renal tubular acidosis type 3 | AR | CA2 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | #611492 |

| Hereditary hypophosphatemic rickets with hypercalciuria | AR | SLC34A3 | NaPi2c | #241530 |

| X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets | XLD | PHEX | PHEX | #307800 |

| Cystinuria A | AD | SLC3A1 | rBAT | #104614 |

| Cystinuria B | AR | SLC7A9 | b(0,+)AT1 | #604144 |

| Lysinuric protein intolerance | AR | SLC7A7 | y(+)LAT1 | #222700 |

| Hartnup disorder | AR | SLC6A19 | B(0)AT1 | #234500 |

| Iminoglycinuria | AR/digenic | SLC36A2+SLC6A20/SLC6A19 | SLC36A2+SLC6A20/SLC6A19 | #242600 |

| Dicarboxylic aminoaciduria | AR | SLC1A1 | ? | #222730 |

| Thick ascending limb | ||||

| Bartter type 1 | AR | SLC12A1 | NKCC2 | #600839 |

| Bartter type 2 | AR | KCNJ1 | ROMK | #600359 |

| Bartter type 3 | AR | CLCNKB | CLC-Kb | #602023 |

| Bartter type 4a | AR | BSND | Barttin | #606412 |

| Bartter type 4b | Digenic | CLCNKA+CLCNKB | CLC-Ka+CLC-Kb | #602024 |

| Bartter type 5 | XR | MAGED2 | MAGED2 | #601199 |

| Hypomagnesemia type 3/familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis | AR | CLDN16 | Claudin16 | #603959 |

| Hypomagnesemia type 5/familial hypomagnesemia with hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis | AR | CLDN19 | Claudin19 | #610036 |

| Autosomal dominant hypocalcemia | AD | CaSR | Calcium-sensing receptor | #601198 |

| Kenny−Caffey syndrome type 2 | AD | FAM111A | FAM111A | #127000 |

| Distal convoluted tubule | ||||

| Gitelman syndrome | AR | SLC12A3 | NCCT | #600968 |

| EAST/SeSAME syndrome | AR | KCNJ10 | Kir4.1 | #602028 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2b | AD | WNK4 | WNK4 | #601844 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2c | AD | WNK1 | WNK1 | #605232 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2d | AD/AR | KLHL3 | KLHL3 | #614495 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2e | AD | CUL3 | CUL3 | #614496 |

| Hypomagnesemia type 1/hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia | AR | TRPM6 | TRPM6 | #607009 |

| Hypomagnesemia type 2 | AD | FXYD2 | Na-K-ATPase | #154020 |

| Autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia | AD | KCNA1 | Kv1.1 | #176260 |

| HNF1B-related kidney disease | AD | HNF1B | HNF1B | #137920 |

| Hyperphenylalaninemia BH4-deficient | AR | PCBD1 | PCDB1 | #264070 |

| Hypomagnesemia type 4 | AR | EGF | EGF | #611718 |

| Neonatal inflammatory skin and bowel disease type 2 | AR | EGFR | EGFR | #616069 |

| Hypomagnesemia, seizures, and mental retardation type 1 | AD/AR | CNNM2 | CNNM2 | #613882 |

| Hypomagnesemia, seizures, and mental retardation type 2 | De novo | ATP1A1 | ATP1A1 | #618314 |

| Collecting duct | ||||

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 | AR | SCNN1A | ENaC α subunit | #600228 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 | AR | SCNN1B | ENaC β subunit | #600760 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 | AR | SCNN1G | ENaC γ subunit | #600761 |

| Pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1A | AD | NR3C2 | MR | #600983 |

| Liddle syndrome | AD | SCNN1B | ENaC β subunit | #600760 |

| Liddle syndrome | AD | SCNN1G | ENaC γ subunit | #600761 |

| Apparent mineralocorticoid excess | AR | HSD11B2 | 11-β-HSD2 | #614232 |

| Glucocorticoid remediable aldosteronism | AD | CYP11B1/CYP11B2 | 11-β-hydroxylase/ALDOS | #610613 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia type 1 | AR | CYP21A2 | 21-hydroxylase | #613815 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia type 2 | AR | HSD3B2 | 3-β-HSD2 | #613890 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia type 4 | AR | CYP11B1 | 11-β-hydroxylase | #610613 |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia type 5 | AR | CYP17A1 | 17-α-hydroxylase | #609300 |

| Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus | XLR | AVPR2 | AVPR2 | #300538 |

| Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus | AR/AD | AQP2 | AQP-2 | #107777 |

| Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis | XLR | AVPR2 | V2R | #300538 |

| Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis | AD | GNAS | G-α s | |

| Distal RTA | AD/AR | SLC4A1 | AE1 | #109270 |

| Distal RTA | AR | ATP6V1B1 | V-ATPase subunit B1 | #192132 |

| Distal RTA | AR | ATP6V0A4 | V-ATPase subunit a4 | #605239 |

| Distal RTA | AR | FOXI1 | Forkhead box protein I1 | #601093 |

| Distal RTA | AR | WDR72 | WD repeat-containing protein 72 | #613214 |

Listed are primary renal tubulopathies grouped by affected nephron segment, the underlying gene(s), and encoded protein(s), as well as their OMIM entry number. OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; XLR, x-linked recessive; RTA, renal tubular acidosis.

Kidney physiologists often study genetically modified animals to better understand the role of the respective gene. In contrast, clinicians studying patients with suspected tubulopathies find clues as to the potentially underlying cause through clinical observations. It is clinicians, who, together with genetic and physiologic scientists, have often led the discovery of these transport molecules and their encoding genes and thereby provided fundamental insights into kidney physiology. In this review, rather than providing an exhaustive discussion of all tubulopathies, we focus on the contribution of genetics to our current understanding of tubulopathies and, in turn, kidney physiology.

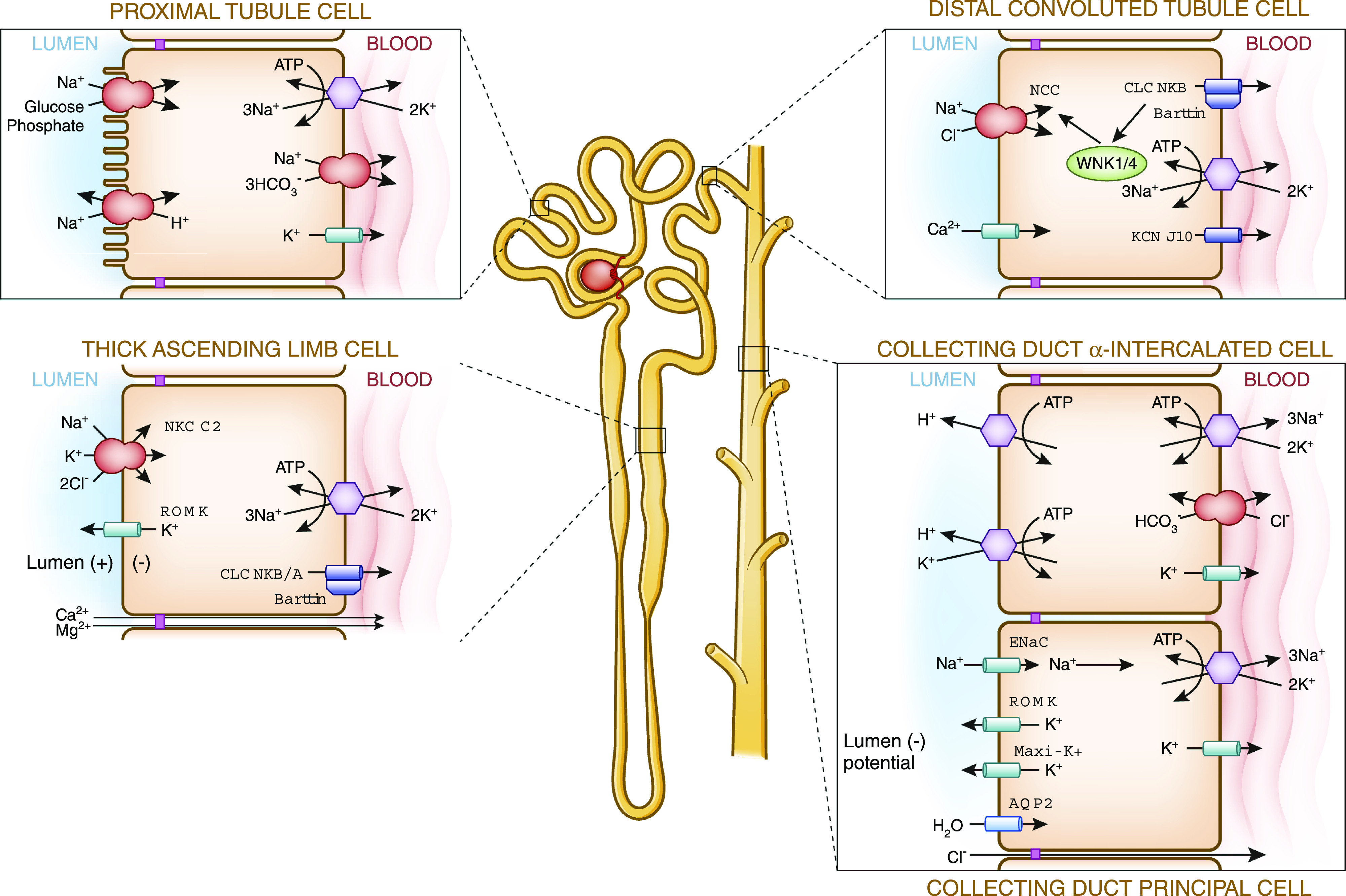

The Central Role of Salt

On average, the human adult kidney filters approximately 150–180 L of water and 20–25 mol of sodium per day, of which typically >99% is then reabsorbed back into the circulation by multiple sodium transport systems along the nephron (Figure 1) (3). The engine that drives tubular transport is the Na+-K+-ATPase, located on the basolateral aspect of the tubular epithelial cells. The stoichiometry of 3 sodium versus 2 potassium ion counter transport in concert with a potassium conductance establishes the crucial electrochemical gradient that facilitates sodium entry from the tubular lumen. Consequently, this gradient is used for the transport of many other solutes, such as glucose, various amino acids and phosphate (by cotransport), protons and potassium (by exchange), or calcium and uric acid (by facilitated diffusion) (3).

Figure 1.

Inherited tubulopathies are caused by dysfunction of specific transport molecules in the renal tubule. Shown is an overview of a nephron, detailing selected transporters involved in disorders of tubular sodium handling. For associated disorders, see Table 1.

Genetic and clinical investigations into rare disorders of kidney salt handling have facilitated the cloning of many of the most important salt transport systems. Often, this was in parallel with kidney physiologic studies. The identification of the genetic basis of Bartter and Gitelman syndromes, for instance, fit perfectly with the understanding of kidney physiology and the clinical experience from loop and thiazide diuretics (4). But in some instances, genetic investigations also provided very surprising results that prompted a revision of our understanding of physiology.

A key insight from these genetic studies is the recognition of kidney salt handling at the center of BP regulation and thus volume homeostasis (5). In the 1970s, Guyton et al. (6) described in detail the numerous physiologic processes implicated in affecting BP and beautifully illustrated the integration of all these factors in a famous diagram. But subsequent genetic studies of rare disorders associated with abnormal BP clearly established kidney salt handling at the center of long-term BP regulation (5).

An interesting observation from these disorders is the evolutionary ranking of the various aspects of homeostasis. Because the transport of many solutes in the tubule is directly or indirectly linked to sodium, this can create conflicts; for instance, in the collecting duct, the reabsorption of sodium via the epithelial sodium channel creates the favorable electrical gradient for the secretion of potassium and protons (Figure 1). Consequently, the biochemical “fingerprint” of enhanced sodium reabsorption in this segment is hypokalemic alkalosis (7). In Bartter and Gitelman syndromes, the kidneys excrete potassium and protons to facilitate sodium reabsorption, demonstrating the precedence of volume homeostasis over potassium and acid-base balance (3). It follows naturally from this insight that salt supplementation should be beneficial also for normalizing plasma potassium levels in these salt-wasting syndromes (8).

Genetic investigations have also revealed how evolution has devised mechanisms to cope with competing homeostatic demands. The identification of the genetic basis of pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2 (Gordon syndrome) elegantly solved the “aldosterone paradox,” i.e., the question of how aldosterone could be involved in the potentially conflicting demands of volume and potassium homeostasis (9). If both sodium and potassium need to be preserved, sodium reabsorption is shifted to the distal convoluted tubule (DCT); if sodium must be preserved, but potassium excreted (for instance, after a salt-poor, potassium-rich meal typical for the paleolithic diet), then sodium reabsorption is shifted to the collecting duct, facilitating potassium secretion (9). These and other disorders also revealed the potassium sensing role of KCNJ10, the basolateral potassium channel in the DCT, in which mutations cause epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural-deafness, tubulopathy syndrome (10,11). From a clinical perspective, this has important implications, as it explains why a high-potassium intake facilitates excretion of the high-salt content of a typical Western diet, thus mitigating the associated cardiovascular complications (12).

Genetic studies have also revealed the sometimes haphazard nature of evolution. Intelligent design would likely have made the various steroid hormones specific for their respective receptors. However, the mineralocorticoid receptor is highly sensitive to the glucocorticoid cortisol, which is present in plasma in almost 1000-fold higher concentration than aldosterone (13). Fortunately, specificity is provided by the enzyme HSD11B2, which metabolizes cortisol to cortisone and thereby protects the mineralocorticoid receptor. Mutations in this enzyme lead to the rare hypertensive disorder of apparent mineralocorticoid excess (13). The study of this disorder also illustrates the importance of a comprehensive clinical investigation for a correct diagnosis, as this disorder shares many clinical features with Bartter syndromes types 1 and 2: hypokalemic alkalosis, hypercalciuria, and, commonly, secondary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (14). Only BP and hormone levels can distinguish one disorder from the other: in apparent mineralocorticoid excess, BP is elevated and aldosterone/renin levels are suppressed, whereas in the Bartter syndromes, the opposite is true.

Approximately 65% of sodium reabsorption occurs in the proximal tubule, and experiments in mice show that the bulk of this occurs via the sodium-proton exchanger Nhe3 (15). Consequently, loss of function of NHE3 in humans was expected to be either incompatible with life, or at least lead to a severe form of proximal tubular acidosis (16). Yet, when such loss-of-function mutations were identified, they were associated with the intestinal disorder congenital secretory sodium diarrhea with no apparent kidney phenotype (17). Further studies in mice demonstrated that a kidney-specific knockout of Nhe3 does exhibit some bicarbonate wasting, albeit mild (18). Potentially, downstream isoforms of NHE provide compensation for NHE3-specific dysfunction in the proximal tubule, thereby explaining the mild kidney phenotype.

Disorders of Water

Disorders of kidney water handling were among the first tubulopathies to be genetically solved, perhaps because of the typical clinical presentation: impaired kidney water conservation (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus) is associated with hypernatremic dehydration, whereas impaired water excretion (nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis) is associated with hyponatremia (19,20).

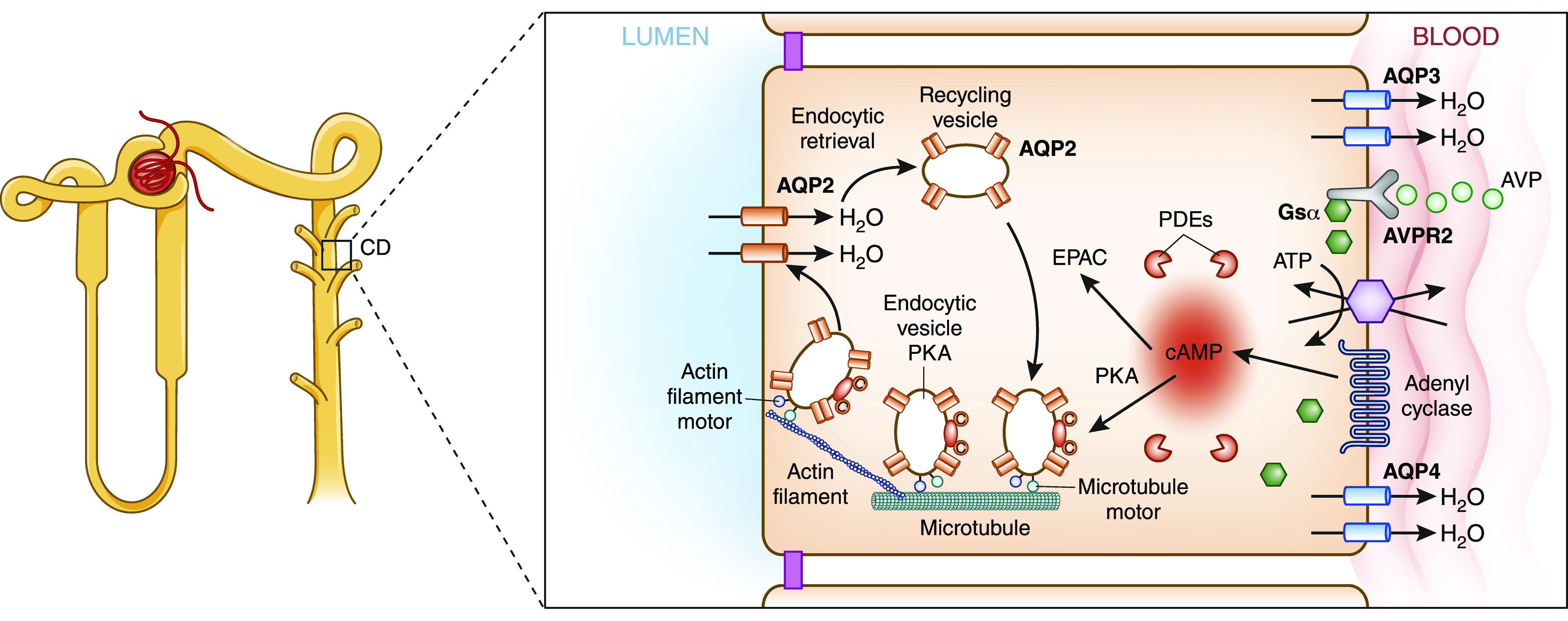

Primary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is associated with mutations in two genes, AVPR2 and AQP2, encoding for the type 2 arginine-vasopressin (AVP) receptor and a water channel, respectively (Figure 2) (21,22). Detailed clinical observations in affected patients have revealed also extrarenal roles of AVPR2, expressed in the vasculature, where activation of the receptor results in vasodilation and release of coagulation factors (23).

Figure 2.

Disorders of water are caused by impaired regulation of water reabsorption in the collecting duct. Shown is a schematic of a principal cell in the collecting duct (CD), with relevance to water transport. Note the expression of AVPR2 on the basolateral side. Activation of this receptor results in insertion of AQP2 into the apical membrane.

Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is characterized by an inability to dilute the urine, with a consequent risk of hyponatremia from water overload (20,24). It is thus the mirror image of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: nephrogenic diabetes insipidus reflects loss of function in the urinary concentration pathway, whereas nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is caused by gain-of-function mutations in AVPR2 (20). Yet, no corresponding gain-of-function mutations in AQP2 have so far been described. Instead, mutations in GNAS have been identified as another cause of nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis, either isolated or as part of a more complex syndrome, which reflects the association of GNAS with several G protein–coupled receptors (25,26). GNAS encodes the stimulatory G-α protein, which links AVPR2 activation to adenyl cyclase in the AVP signaling pathway (Figure 2) (27). Why some GNAS mutations lead to syndromic features and others seem to cause isolated nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is currently unclear. It has been speculated that AVPR2 signaling may be the most sensitive GNAS-associated pathway, so that milder mutation manifest clinically only in impaired urinary dilution (25).

These disorders therefore provide important clinical insights, corresponding to those from salt-handling disorders: impaired kidney water handling is reflected in dysnatremia, whereas disorders of kidney sodium handling primarily result in altered volume homeostasis. Moreover, they demonstrate the precedence of volume homeostasis over maintenance of normal plasma tonicity: in hypernatremic dehydration in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, the kidneys will preserve sodium, whereas in hyponatremia water overload in the nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis, sodium is excreted. Such insight also informs the diagnosis and treatment of the more common but related disorder, the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis, which, owing to its elevated urinary sodium concentration, is commonly misdiagnosed as cerebral or pulmonary salt wasting (7). Treatment with salt supplementation thus only re-establishes the volume overload and consequently risks hypertension. Instead, asymptomatic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis should be treated by water removal (28).

Acid-Base Homeostasis

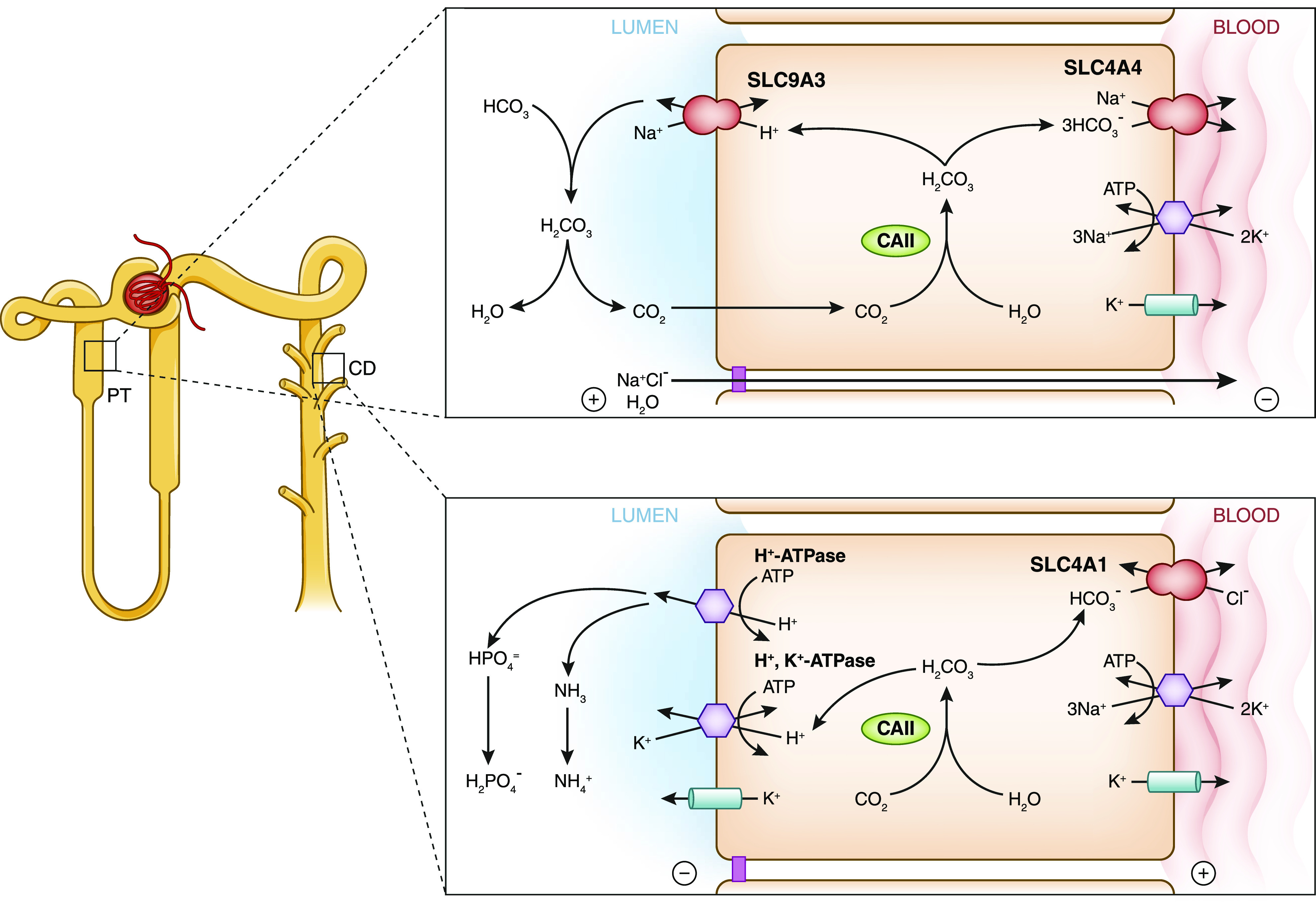

Early clinical and physiologic investigations distinguished renal tubular acidosis (RTA) into a proximal and distal form, to which a mixed form was later added (29,30).

Subsequent discovery of the underlying genes beautifully confirmed the initial astute clinical observations as these genes encoded proteins involved in either proximal bicarbonate reabsorption (proximal RTA) or distal proton secretion (distal RTA) or both (Figure 3). Proximal RTA typically occurs in people with generalized proximal tubular dysfunction (Fanconi renotubular syndrome). Isolated proximal RTA is exceedingly rare, is associated with eye abnormalities, and is caused by mutations in the basolateral sodium/bicarbonate exchanger SLC4A4 (31). A further family with apparently isolated proximal RTA and dominant inheritance has been described, but the genetic basis remains so far unsolved (32). SLC9A3 (see above) was considered a strong candidate, but this could not be confirmed, illustrating how our understanding of kidney physiology, derived mainly from animal models, can at times be critically informed by insights from human genetics (16).

Figure 3.

Disorders of acid-base homeostasis are caused by impaired bicarbonate reabsorption in the proximal tubule or impaired acid secretion in the collecting duct. Shown is a schematic of a tubular epithelial cell in the proximal tubule (PT) and an intercalated cell (type A) in the collecting duct (CD), highlighting proteins involved in bicarbonate reabsorption and acid secretion. For associated disorders, see Table 1.

Genetic investigations into distal RTA provided insights into the different functions of the chloride/bicarbonate anion exchanger AE1. This transport protein, encoded by SLC4A1 and initially identified in Western blots from red cells (“Band 3”), was already associated with East Asian ovalocytosis and hereditary spherocytosis, but was subsequently found to also cause distal RTA (33).

Physiologic investigations have highlighted the role of both the H+-ATPase and H+/K+-ATPase in the collecting duct for distal acid secretion (34,35). Yet, so far, mutations have been identified in only two of the 14 different subunits of the H+-ATPase (ATP6V0A4 and ATP6V1B1) that cause distal RTA, and in none of the H+/K+-ATPase (36,37). The remaining genes are obviously strong candidate genes for the 30%–40% of genetically unsolved patients with a clinical diagnosis of primary distal RTA, yet so far, no convincing mutations have been reported (38). Instead, two different genes have emerged as novel distal RTA disease genes. The first, FOXI1, fits perfectly with current understanding of physiology (39). It encodes a transcription factor regulating the expression of several proteins involved in acid secretion, and mice deleted for the murine paralogue had been previously described to have distal RTA (40). Mutations in transcription factors are usually inherited in a dominant fashion, probably reflecting the fact that complete loss is not compatible with life (41). The fact that FOXI1 mutations are recessively inherited highlights the specific and restricted role of this transcription factor in acid-secreting epithelia.

In contrast to FOXI1, the discovery of WDR72 as a distal RTA disease gene was completely unexpected, illustrating the power of genetics to provide novel insights (42). Mutations in WDR72 were identified in several patients with a syndromic combination of amelogenesis imperfecta and distal RTA. The exact mechanisms of how WDR72 mutations are linked to distal RTA remain unclear at present. Interestingly, WDR72 mutations had been previously identified as a cause of amelogenesis imperfecta (43). It remains unclear whether specific WDR72 mutations can cause isolated dental problems, others only distal RTA, and yet others both clinical features. Potentially, this just reflects incomplete phenotyping, so that the dentist may have missed the presence of distal RTA, just as the nephrologist may have overlooked amelogenesis imperfecta. Interestingly, the identification of WDR72 mutations in a cohort of patients with distal RTA led to the subsequent diagnosis of amelogenesis imperfecta in all affected patients by “reverse phenotyping” (44). This is reminiscent of the identification of FAM20A mutations first as a cause of amelogenesis imperfecta, and subsequently, of nephrocalcinosis (45). Arguably, these examples illustrate the narrow clinical focus of individual medical specialties and the importance of comprehensive phenotyping.

Clinical studies in patients with acid-base abnormalities reveal the critical importance of precise acid-base balance for proper physiologic function of our body, reflected in the exquisitely tight control of arterial pH between 7.37 and 7.43, a change of <±3 nmol/L. Protons can bind to proteins, especially to histidine residues, and thereby affect protein charge, which in turn affects protein folding and function. Consequently, disturbances of acid-base balance are potentially catastrophic and can include dysrhythmias, apnea, coma, and death (46). And even relatively mild forms of distal RTA reveal that acidosis is associated not only with rickets and nephrocalcinosis/urolithiasis, but also with more general symptoms, such as impaired growth (47).

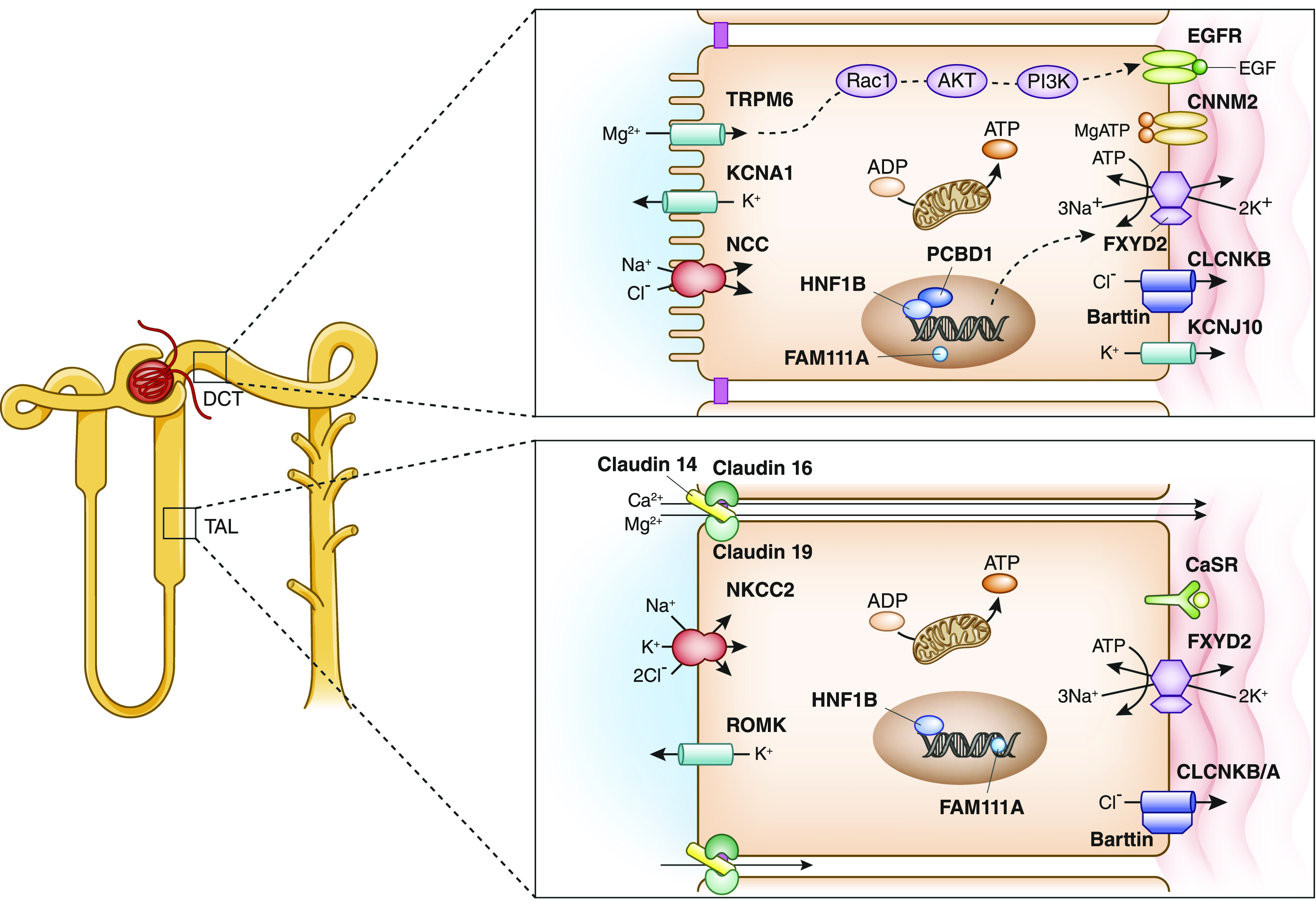

Magnesium Homeostasis

Magnesium is the second-most abundant intracellular cation and a cofactor in numerous enzymatic reactions, yet it is often called the “forgotten ion” (48). Magnesium homeostasis is primarily maintained through reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) and DCT, and clinically, this can be typically distinguished by the concurrence of hypercalciuria (TAL) or normo-/hypocalciuria (DCT) (49). All known genetic causes of hypomagnesemia encode proteins expressed in these functional segments of the nephron (Figure 4). In the TAL, calcium and magnesium are reabsorbed through a common paracellular pathway, lined by CLDN16 and CLDN19, mutations in which cause hypercalciuric hypomagnesemia (49). Interestingly, mutations in CLDN10, another claudin that lines this paracellular pore, enhance magnesium reabsorption and thereby cause hypermagnesemia as part of a more complex phenotype called HELIX syndrome (50).

Figure 4.

Disorders of magnesium homeostasis are caused by impaired magnesium transport in TAL or DCT. Shown is a schematic of a tubular epithelial cell in thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle (TAL) and distal convoluted tubule (DCT), highlighting proteins involved in tubular magnesium handling. For associated disorders, see Table 1.

Although paracellular reabsorption of cations depends on a transepithelial voltage gradient, which is established by the combined function of NKCC2 and ROMK1, the corresponding recessive disorders Bartter syndromes type 1 and 2 are usually not associated with hypomagnesemia (3). In contrast, dominant gain-of-function mutations in the calcium-sensing receptor that suppress ROMK function do associate with hypomagnesemia, likely because of other functional roles of this receptor (49).

Although only about 10% of filtered magnesium is reabsorbed in the DCT, this represents the final regulated pathway, and genetic investigations have revealed a surprising complexity: at least 15 genes have so far been identified in which mutations impair magnesium transport in this segment (Figure 4, Table 1). These are associated with hypocalciuria if not only magnesium but also salt reabsorption is affected (Gitelman-like hypomagnesemias [49]), as the resulting hypovolemia leads to increased proximal sodium and thus calcium reabsorption (51). In contrast, disorders affecting magnesium transport only are associated with normocalciuria. The most prominent example for the latter is familial hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia, and the identification of the underlying genetic basis as mutations in TRPM6 established this channel as the key magnesium transport pathway in the apical membrane of the DCT (52).

There are some interesting observations in genetically defined patients with hypomagnesemia. For instance, mutations impairing the function of the basolateral Na+-K+-ATPase seem to predominantly affect magnesium transport. Mutations in the α (ATP1A1) (53) or γ (FXYD2) (54) subunit, or in their regulators, such as HNF1B (55), manifest primarily with hypomagnesemia, although a trend to a Gitelman-like tubulopathy may be observed (56). Presumably, this reflects the critical role of the DCT for magnesium homeostasis, whereas other segments may be able to compensate more with regard to sodium (57).

Another interesting observation is the apparent absence of hypokalemia in patients with TRPM6 mutations (58). Because ROMK is inhibited by intracellular magnesium, hypomagnesemia has been proposed as a cause for refractory hypokalemia (59). Yet, these patients, despite their often profound hypomagnesemia, are not reported to suffer from hypokalemia, seriously questioning the clinical relevance of hypomagnesemia for potassium control.

A relevant physiologic question arising from the genetic findings in patients with hypomagnesemia is regarding the link between impaired sodium transport in DCT and magnesium reabsorption. Presumably, apical sodium uptake via SCL12A3 is necessary to maintain the activity of the Na+-K+-ATPase, which, in turn, establishes the electrochemical gradient that facilitates magnesium uptake. To do so, an apical potassium channel is needed that can translate this electrochemical gradient into a lumen-negative membrane potential to enable magnesium uptake via TRPM6. The identification of a familial form of hypomagnesemia associated with a mutation in the apically expressed potassium channel KCNA1 fits nicely with this hypothesis, except that this is a voltage-gated potassium channel with essentially zero open probability at the membrane voltages observed in DCT (60). Moreover, other mutations in KCNA1 are the cause of episodic ataxia type 1, which is not associated with hypomagnesemia (49). Further studies are needed to resolve these apparent conundrums.

Genetic investigations have also provided some insights with regard to the identity of the basolateral transport pathway for magnesium in DCT, although questions remain. Initially, CNNM2 was thought to constitute this pathway in the form of a basolateral sodium-magnesium exchanger, but later it was also proposed to be an intracellular magnesium sensor (61,62). Thus, whether CNNM2 constitutes the main basolateral exit pathway or whether other transport proteins are involved remains currently unclear.

Genetic Testing in Tubulopathies

Currently, more than 50 disease genes for kidney tubulopathies are recognized (Table 1), and the list keeps on expanding. Because of the specific phenotype associated with mutations in most genes, an accurate clinical diagnosis can usually be established. However, even in expert centers, genetic testing can sometimes further specify or even correct the clinical diagnosis, so that genetic confirmation is usually recommended because of potentially important implications not only for genetic counseling, but also for treatment (63,64). For instance, Bartter syndrome is occasionally misdiagnosed as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and the common therapeutic use of thiazides for the latter could have life-threatening consequences in the former disorder (27). Whether genetic testing is done by sequencing of single genes, a targeted panel, or whole exome/genome depends on the certainty of the clinical diagnosis and local availability/affordability. If no causative variant(s) are identified by selected gene sequencing, a subsequent more comprehensive approach is necessary to reach a genetic diagnosis. For this reason, whole-exome/-genome sequencing is increasingly used as a first-line approach. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the aim is to use whole-genome sequencing for the vast majority of genetic tests (https://www.england.nhs.uk/genomics/nhs-genomic-med-service/). To minimize the analytical workload and the risk of incidental findings, only a panel of relevant disease genes is assessed. Obviously, these gene panels need to be constantly updated, and various resources for this exist (65).

Yet, although the diagnostic yield of genetic testing in tubulopathies is much higher than in most other kidney disorders, in about a third of patients with pediatric onset tubulopathy, a genetic diagnosis cannot be established and this increases to more than two thirds in those with adult onset (63,64). This likely reflects the diagnostic uncertainty regarding some identified variants, or genes, as well as acquired causes, especially in adult-onset patients.

Translation of Genetic Insights

Genetic investigations have provided unparalleled insights into the molecular basis of tubular physiology and thus the maintenance of homeostasis. Although discoveries of new Mendelian disease genes are still ongoing, their number is necessarily limited. Other genetic approaches, such as genome-wide association studies, may provide further insights into the genetic architecture of tubulopathies and the maintenance of homeostasis (66).

Translating genetic discoveries into targeted treatments is an obvious key aim. Many of the identified molecular causes were already known as targets of drugs, such as diuretics. For disorders with a gain-of-function disease mechanism, treatment can be logical and targeted, such as the use of thiazides in pseudohypoaldosteronism type 2 or amiloride in Liddle syndrome. In some instances, understanding of the molecular mechanism has provided a basis for the development of a specific treatment. One that has now entered the clinical arena is the anti-FGF23 antibody burosumab in X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets (67). Another example is the recognition of the central role of cyclic AMP in kidney water handling, which has spurred investigations into novel treatments for nephrogenic diabetes that enhance AQP2 expression in the apical membrane independent of AVPR2 receptor activation (68(–70).

Yet, for most tubulopathies, treatment has remained essentially unchanged over the past decades and is mainly supportive; for instance, in the form of electrolyte supplements. Fortunately, the advent of gene-editing technologies, such as CRISPR/CAS9, may provide opportunities for the future treatment of tubulopathies (71). In contrast to most other genetic kidney disorders, such as inherited kidney malformations or nephronophthisis, in which global kidney architecture and function is typically irreversibly altered at the time of diagnosis, tubulopathies affect only very specific aspects of kidney function. Although there may be some irreversible changes, such as nephrocalcinosis or interstitial fibrosis, most patients with tubulopathies would have sufficient kidney function if the genetic defect could be repaired.

A key obstacle remains the targeted delivery of the gene-editing machinery to the kidney. So far, clinical trials of gene editing address mostly hematologic or immune disorders, where relevant blood cells can be obtained for gene editing ex vivo and then returned to the patient (72). However, if precise delivery to the tubule can be achieved, then tubulopathies will constitute an ideal group of disorders for the therapeutic application of this promising new technology. Another approach currently trialed is delivery of the correct gene via hematopoietic stem cells (73).

Conclusions

Tubulopathies of the kidney illustrate the synergistic potential of clinical, genetic, and physiologic investigations to facilitate accurate diagnosis and targeted management of affected patients, in turn enhancing our understanding of kidney physiology. They reveal the superior importance of sodium in overall tubular transport, the primate of volume over other aspects of homeostasis, and its control through sodium reabsorption. Tubulopathies also sometimes dramatically illustrate the critical importance of homeostasis for overall body function.

The high rate of identifiable underlying genetic causes, and the fact that they affect very specific aspects of tubular function while generally preserving overall kidney function, make them ideal targets for future treatments using gene-editing techniques.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

M.L. Downie, R. Kleta, and D. Bockenhauer were supported by St. Peter’s Trust for Kidney, Bladder & Prostate Research. S.C. Lopez Garcia, R. Kleta, and D. Bockenhauer are grateful to Dr. Magdi Yaqoob for support through the William Harvey Paediatric Fellowship. R. Kleta and D. Bockenhauer were supported by Kids Kidney Research and Kidney Research UK. R. Kleta was supported by the David and Elaine Potter Foundation. D. Bockenhauer was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Great Ormond Street Hospital/University College London Institute of Child Health.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Bernard C: Leçons sur les phénomènes de la vie communs aux animaux et aux vegetaux, Paris, J.-B. Baillière, 1878 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plumb LA, Van’t Hoff W, Kleta R, Reid C, Ashton E, Samuels M, Bockenhauer D: Renal apnoea: Extreme disturbance of homoeostasis in a child with Bartter syndrome type IV. Lancet 388: 631–632, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleta R, Bockenhauer D: Salt-losing tubulopathies in children: What’s new, what’s controversial? J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 727–739, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon DB, Bindra RS, Mansfield TA, Nelson-Williams C, Mendonca E, Stone R, Schurman S, Nayir A, Alpay H, Bakkaloglu A, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Morales JM, Sanjad SA, Taylor CM, Pilz D, Brem A, Trachtman H, Griswold W, Richard GA, John E, Lifton RP: Mutations in the chloride channel gene, CLCNKB, cause Bartter’s syndrome type III. Nat Genet 17: 171–178, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS: Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104: 545–556, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyton AC, Coleman TG, Granger HJ: Circulation: Overall regulation. Annu Rev Physiol 34: 13–46, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockenhauer D, Aitkenhead H: The kidney speaks: Interpreting urinary sodium and osmolality. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 96: 223–227, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchard A, Bockenhauer D, Bolignano D, Calò LA, Cosyns E, Devuyst O, Ellison DH, Karet Frankl FE, Knoers NV, Konrad M, Lin SH, Vargas-Poussou R: Gitelman syndrome: Consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 91: 24–33, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arroyo JP, Ronzaud C, Lagnaz D, Staub O, Gamba G: Aldosterone paradox: Differential regulation of ion transport in distal nephron. Physiology (Bethesda) 26: 115–123, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, Tobin J, Lieberer E, Sterner C, Landoure G, Arora R, Sirimanna T, Thompson D, Cross JH, van’t Hoff W, Al Masri O, Tullus K, Yeung S, Anikster Y, Klootwijk E, Hubank M, Dillon MJ, Heitzmann D, Arcos-Burgos M, Knepper MA, Dobbie A, Gahl WA, Warth R, Sheridan E, Kleta R: Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med 360: 1960–1970, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellison DH, Terker AS, Gamba G: Potassium and its discontents: New insight, new treatments. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 981–989, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drüeke TB: Salt and health: Time to revisit the recommendations. Kidney Int 89: 259–260, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinkler M, Stewart PM: Hypertension and the cortisol-cortisone shuttle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88: 2384–2392, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bockenhauer D, van’t Hoff W, Dattani M, Lehnhardt A, Subtirelu M, Hildebrandt F, Bichet DG: Secondary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus as a complication of inherited renal diseases. Nephron Physiol 116: 23–29, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang T, Yang CL, Abbiati T, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE, Giebisch G, Aronson PS: Mechanism of proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption in NHE3 null mice. Am J Physiol 277: F298–F302, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igarashi T, Sekine T, Inatomi J, Seki G: Unraveling the molecular pathogenesis of isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2171–2177, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janecke AR, Heinz-Erian P, Yin J, Petersen BS, Franke A, Lechner S, Fuchs I, Melancon S, Uhlig HH, Travis S, Marinier E, Perisic V, Ristic N, Gerner P, Booth IW, Wedenoja S, Baumgartner N, Vodopiutz J, Frechette-Duval MC, De Lafollie J, Persad R, Warner N, Tse CM, Sud K, Zachos NC, Sarker R, Zhu X, Muise AM, Zimmer KP, Witt H, Zoller H, Donowitz M, Müller T: Reduced sodium/proton exchanger NHE3 activity causes congenital sodium diarrhea. Hum Mol Genet 24: 6614–6623, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li HC, Du Z, Barone S, Rubera I, McDonough AA, Tauc M, Zahedi K, Wang T, Soleimani M: Proximal tubule specific knockout of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3: Effects on bicarbonate absorption and ammonium excretion. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 951–963, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bockenhauer D, Bichet DG: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 576–588, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman BJ, Rosenthal SM, Vargas GA, Fenwick RG, Huang EA, Matsuda-Abedini M, Lustig RH, Mathias RS, Portale AA, Miller WL, Gitelman SE: Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med 352: 1884–1890, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenthal W, Seibold A, Antaramian A, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Hendy GN, Birnbaumer M, Bichet DG: Molecular identification of the gene responsible for congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nature 359: 233–235, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deen PM, Verdijk MA, Knoers NV, Wieringa B, Monnens LA, van Os CH, van Oost BA: Requirement of human renal water channel aquaporin-2 for vasopressin-dependent concentration of urine. Science 264: 92–95, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bichet DG, Razi M, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Papukna V, Kortas C, Barjon JN: Hemodynamic and coagulation responses to 1-desamino[8-D-arginine] vasopressin in patients with congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. N Engl J Med 318: 881–887, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bockenhauer D, Penney MD, Hampton D, van’t Hoff W, Gullett A, Sailesh S, Bichet DG: A family with hyponatremia and the nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 566–568, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyado M, Fukami M, Takada S, Terao M, Nakabayashi K, Hata K, Matsubara Y, Tanaka Y, Sasaki G, Nagasaki K, Shiina M, Ogata K, Masunaga Y, Saitsu H, Ogata T: Germline-derived gain-of-function variants of Gsα-coding GNAS gene identified in nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 877–889, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bichet DG, Granier S, Bockenhauer D: GNAS: A new nephrogenic cause of inappropriate antidiuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 722–725, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bockenhauer D, Bichet DG: Inherited secondary nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: Concentrating on humans. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F1037–F1042, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marx-Berger D, Milford DV, Bandhakavi M, Van’t Hoff W, Kleta R, Dattani M, Bockenhauer D: Tolvaptan is successful in treating inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion in infants. Acta Paediatr 105: e334–e337, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris RC Jr.: Renal tubular acidosis. Mechanisms, classification and implications. N Engl J Med 281: 1405–1413, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soriano JR, Boichis H, Edelmann CM Jr.: Bicarbonate reabsorption and hydrogen ion excretion in children with renal tubular acidosis. J Pediatr 71: 802–813, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Igarashi T, Inatomi J, Sekine T, Cha SH, Kanai Y, Kunimi M, Tsukamoto K, Satoh H, Shimadzu M, Tozawa F, Mori T, Shiobara M, Seki G, Endou H: Mutations in SLC4A4 cause permanent isolated proximal renal tubular acidosis with ocular abnormalities. Nat Genet 23: 264–266, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenes LG, Brenes JN, Hernandez MM: Familial proximal renal tubular acidosis. A distinct clinical entity. Am J Med 63: 244–252, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruce LJ, Cope DL, Jones GK, Schofield AE, Burley M, Povey S, Unwin RJ, Wrong O, Tanner MJ: Familial distal renal tubular acidosis is associated with mutations in the red cell anion exchanger (Band 3, AE1) gene. J Clin Invest 100: 1693–1707, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gumz ML, Lynch IJ, Greenlee MM, Cain BD, Wingo CS: The renal H+-K+-ATPases: Physiology, regulation, and structure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F12–F21, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner CA, Finberg KE, Breton S, Marshansky V, Brown D, Geibel JP: Renal vacuolar H+-ATPase. Physiol Rev 84: 1263–1314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AN, Skaug J, Choate KA, Nayir A, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Hulton SA, Sanjad SA, Al-Sabban EA, Lifton RP, Scherer SW, Karet FE: Mutations in ATP6N1B, encoding a new kidney vacuolar proton pump 116-kD subunit, cause recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with preserved hearing. Nat Genet 26: 71–75, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karet FE, Finberg KE, Nelson RD, Nayir A, Mocan H, Sanjad SA, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Santos F, Cremers CW, Di Pietro A, Hoffbrand BI, Winiarski J, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Dusunsel R, Goodyer P, Hulton SA, Wu DK, Skvorak AB, Morton CC, Cunningham MJ, Jha V, Lifton RP: Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat Genet 21: 84–90, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashton E, Bockenhauer D: Diagnosis of uncertain significance: Can next-generation sequencing replace the clinician? Kidney Int 97: 455–457, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enerbäck S, Nilsson D, Edwards N, Heglind M, Alkanderi S, Ashton E, Deeb A, Kokash FEB, Bakhsh ARA, Van’t Hoff W, Walsh SB, D’Arco F, Daryadel A, Bourgeois S, Wagner CA, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D, Sayer JA: Acidosis and deafness in patients with recessive mutations in FOXI1. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1041–1048, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vidarsson H, Westergren R, Heglind M, Blomqvist SR, Breton S, Enerbäck S: The forkhead transcription factor Foxi1 is a master regulator of vacuolar H+-ATPase proton pump subunits in the inner ear, kidney and epididymis. PLoS One 4: e4471, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Latchman DS: Transcription-factor mutations and disease. N Engl J Med 334: 28–33, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rungroj N, Nettuwakul C, Sawasdee N, Sangnual S, Deejai N, Misgar RA, Pasena A, Khositseth S, Kirdpon S, Sritippayawan S, Vasuvattakul S, Yenchitsomanus PT: Distal renal tubular acidosis caused by tryptophan-aspartate repeat domain 72 (WDR72) mutations. Clin Genet 94: 409–418, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Sayed W, Parry DA, Shore RC, Ahmed M, Jafri H, Rashid Y, Al-Bahlani S, Al Harasi S, Kirkham J, Inglehearn CF, Mighell AJ: Mutations in the beta propeller WDR72 cause autosomal-recessive hypomaturation amelogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet 85: 699–705, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jobst-Schwan T, Klaembt V, Tarsio M, Heneghan JF, Majmundar AJ, Shril S, Buerger F, Ottlewski I, Shmukler BE, Topaloglu R, Hashmi S, Hafeez F, Emma F, Greco M, Laube GF, Fathy HM, Pohl M, Gellermann J, Hildebrandt F: Whole exome sequencing identified ATP6V1C2 as a novel candidate gene for recessive distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney Int 97: 567–579, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaureguiberry G, De la Dure-Molla M, Parry D, Quentric M, Himmerkus N, Koike T, Poulter J, Klootwijk E, Robinette SL, Howie AJ, Patel V, Figueres ML, Stanescu HC, Issler N, Nicholson JK, Bockenhauer D, Laing C, Walsh SB, McCredie DA, Povey S, Asselin A, Picard A, Coulomb A, Medlar AJ, Bailleul-Forestier I, Verloes A, Le Caignec C, Roussey G, Guiol J, Isidor B, Logan C, Shore R, Johnson C, Inglehearn C, Al-Bahlani S, Schmittbuhl M, Clauss F, Huckert M, Laugel V, Ginglinger E, Pajarola S, Spartà G, Bartholdi D, Rauch A, Addor MC, Yamaguti PM, Safatle HP, Acevedo AC, Martelli-Júnior H, dos Santos Netos PE, Coletta RD, Gruessel S, Sandmann C, Ruehmann D, Langman CB, Scheinman SJ, Ozdemir-Ozenen D, Hart TC, Hart PS, Neugebauer U, Schlatter E, Houillier P, Gahl WA, Vikkula M, Bloch-Zupan A, Bleich M, Kitagawa H, Unwin RJ, Mighell A, Berdal A, Kleta R: Nephrocalcinosis (enamel renal syndrome) caused by autosomal recessive FAM20A mutations. Nephron, Physiol 122: 1–6, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avner ED, Harmon WE, Niaudet P, Yoshikawa N, Emma F, Goldstein SL: Pediatric Nephrology, Heidelberg, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopez-Garcia SC, Emma F, Walsh SB, Fila M, Hooman N, Zaniew M, Bertholet-Thomas A, Colussi G, Burgmaier K, Levtchenko E, Sharma J, Singhal J, Soliman NA, Ariceta G, Basu B, Murer L, Tasic V, Tsygin A, Decramer S, Gil-Pena H, Koster-Kamphuis L, La Scola C, Gellermann J, Konrad M, Lilien M, Francisco T, Tramma D, Trnka P, Yuksel S, Caruso MR, Chromek M, Ekinci Z, Gambaro G, Kari JA, Konig J, Taroni F, Thumfart J, Trepiccione F, Winding L, Wuhl E, Agbas A, Belkevich A, Vargas-Poussou R, Blanchard A, Conti G, Boyer O, Dursun I, Pinarbasi AS, Melek E, Miglinas M, Novo R, Mallett A, Milosevic D, Szczepanska M, Wente S, Cheong HI, Sinha R, Gucev Z, Dufek S, Iancu D, Kleta R, Schaefer F, Bockenhauer D; European dRTA Consortium: Treatment and long-term outcome in primary distal renal tubular acidosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 34: 981–991, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elin RJ: Magnesium: The fifth but forgotten electrolyte. Am J Clin Pathol 102: 616–622, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viering DHHM, de Baaij JHF, Walsh SB, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D: Genetic causes of hypomagnesemia, a clinical overview. Pediatr Nephrol 32: 1123–1135, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hadj-Rabia S, Brideau G, Al-Sarraj Y, Maroun RC, Figueres ML, Leclerc-Mercier S, Olinger E, Baron S, Chaussain C, Nochy D, Taha RZ, Knebelmann B, Joshi V, Curmi PA, Kambouris M, Vargas-Poussou R, Bodemer C, Devuyst O, Houillier P, El-Shanti H: Multiplex epithelium dysfunction due to CLDN10 mutation: The HELIX syndrome. Genet Med 20: 190–201, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nijenhuis T, Vallon V, van der Kemp AW, Loffing J, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ: Enhanced passive Ca2+ reabsorption and reduced Mg2+ channel abundance explains thiazide-induced hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia. J Clin Invest 115: 1651–1658, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlingmann KP, Weber S, Peters M, Niemann Nejsum L, Vitzthum H, Klingel K, Kratz M, Haddad E, Ristoff E, Dinour D, Syrrou M, Nielsen S, Sassen M, Waldegger S, Seyberth HW, Konrad M: Hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia is caused by mutations in TRPM6, a new member of the TRPM gene family. Nat Genet 31: 166–170, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlingmann KP, Bandulik S, Mammen C, Tarailo-Graovac M, Holm R, Baumann M, König J, Lee JJY, Drögemöller B, Imminger K, Beck BB, Altmüller J, Thiele H, Waldegger S, Van’t Hoff W, Kleta R, Warth R, van Karnebeek CDM, Vilsen B, Bockenhauer D, Konrad M: Germline de novo mutations in ATP1A1 cause renal hypomagnesemia, refractory seizures, and intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet 103: 808–816, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meij IC, Koenderink JB, van Bokhoven H, Assink KF, Groenestege WT, de Pont JJ, Bindels RJ, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP, Knoers NV: Dominant isolated renal magnesium loss is caused by misrouting of the Na(+),K(+)-ATPase gamma-subunit. Nat Genet 26: 265–266, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adalat S, Woolf AS, Johnstone KA, Wirsing A, Harries LW, Long DA, Hennekam RC, Ledermann SE, Rees L, van’t Hoff W, Marks SD, Trompeter RS, Tullus K, Winyard PJ, Cansick J, Mushtaq I, Dhillon HK, Bingham C, Edghill EL, Shroff R, Stanescu H, Ryffel GU, Ellard S, Bockenhauer D: HNF1B mutations associate with hypomagnesemia and renal magnesium wasting. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1123–1131, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adalat S, Hayes WN, Bryant WA, Booth J, Woolf AS, Kleta R, Subtil S, Clissold R, Colclough K, Ellard S, Bockenhauer D: HNF1B mutations are associated with a Gitelman-like tubulopathy that develops during childhood. Kidney Int Rep 4: 1304–1311, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reilly RF, Ellison DH: Mammalian distal tubule: Physiology, pathophysiology, and molecular anatomy. Physiol Rev 80: 277–313, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schlingmann KP, Sassen MC, Weber S, Pechmann U, Kusch K, Pelken L, Lotan D, Syrrou M, Prebble JJ, Cole DE, Metzger DL, Rahman S, Tajima T, Shu SG, Waldegger S, Seyberth HW, Konrad M: Novel TRPM6 mutations in 21 families with primary hypomagnesemia and secondary hypocalcemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 3061–3069, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang CL, Kuo E: Mechanism of hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2649–2652, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glaudemans B, van der Wijst J, Scola RH, Lorenzoni PJ, Heister A, van der Kemp AW, Knoers NV, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ: A missense mutation in the Kv1.1 voltage-gated potassium channel-encoding gene KCNA1 is linked to human autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia. J Clin Invest 119: 936–942, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stuiver M, Lainez S, Will C, Terryn S, Günzel D, Debaix H, Sommer K, Kopplin K, Thumfart J, Kampik NB, Querfeld U, Willnow TE, Němec V, Wagner CA, Hoenderop JG, Devuyst O, Knoers NV, Bindels RJ, Meij IC, Müller D: CNNM2, encoding a basolateral protein required for renal Mg2+ handling, is mutated in dominant hypomagnesemia. Am J Hum Genet 88: 333–343, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arjona FJ, de Baaij JH, Schlingmann KP, Lameris AL, van Wijk E, Flik G, Regele S, Korenke GC, Neophytou B, Rust S, Reintjes N, Konrad M, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: CNNM2 mutations cause impaired brain development and seizures in patients with hypomagnesemia. PLoS Genet 10: e1004267, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashton EJ, Legrand A, Benoit V, Roncelin I, Venisse A, Zennaro MC, Jeunemaitre X, Iancu D, Van’t Hoff WG, Walsh SB, Godefroid N, Rotthier A, Del Favero J, Devuyst O, Schaefer F, Jenkins LA, Kleta R, Dahan K, Vargas-Poussou R, Bockenhauer D: Simultaneous sequencing of 37 genes identified causative mutations in the majority of children with renal tubulopathies. Kidney Int 93: 961–967, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hureaux M, Ashton E, Dahan K, Houillier P, Blanchard A, Cormier C, Koumakis E, Iancu D, Belge H, Hilbert P, Rotthier A, Del Favero J, Schaefer F, Kleta R, Bockenhauer D, Jeunemaitre X, Devuyst O, Walsh SB, Vargas-Poussou R: High-throughput sequencing contributes to the diagnosis of tubulopathies and familial hypercalcemia hypocalciuria in adults. Kidney Int 96: 1408–1416, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin AR, Williams E, Foulger RE, Leigh S, Daugherty LC, Niblock O, Leong IUS, Smith KR, Gerasimenko O, Haraldsdottir E, Thomas E, Scott RH, Baple E, Tucci A, Brittain H, de Burca A, Ibañez K, Kasperaviciute D, Smedley D, Caulfield M, Rendon A, McDonagh EM: PanelApp crowdsources expert knowledge to establish consensus diagnostic gene panels. Nat Genet 51: 1560–1565, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meyer TE, Verwoert GC, Hwang SJ, Glazer NL, Smith AV, van Rooij FJ, Ehret GB, Boerwinkle E, Felix JF, Leak TS, Harris TB, Yang Q, Dehghan A, Aspelund T, Katz R, Homuth G, Kocher T, Rettig R, Ried JS, Gieger C, Prucha H, Pfeufer A, Meitinger T, Coresh J, Hofman A, Sarnak MJ, Chen YD, Uitterlinden AG, Chakravarti A, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Kao WH, Witteman JC, Gudnason V, Siscovick DS, Fox CS, Kottgen A; Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis Consortium; Meta Analysis of Glucose and Insulin Related Traits Consortium: Genome-wide association studies of serum magnesium, potassium, and sodium concentrations identify six loci influencing serum magnesium levels. PLoS Genet 6: e1001045, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carpenter TO, Whyte MP, Imel EA, Boot AM, Högler W, Linglart A, Padidela R, Van’t Hoff W, Mao M, Chen CY, Skrinar A, Kakkis E, San Martin J, Portale AA: Burosumab therapy in children with X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med 378: 1987–1998, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ando F, Mori S, Yui N, Morimoto T, Nomura N, Sohara E, Rai T, Sasaki S, Kondo Y, Kagechika H, Uchida S: AKAPs-PKA disruptors increase AQP2 activity independently of vasopressin in a model of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nat Commun 9: 1411, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bech AP, Wetzels JFM, Nijenhuis T: Effects of sildenafil, metformin, and simvastatin on ADH-independent urine concentration in healthy volunteers. Physiol Rep 6: e13665, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olesen ET, Rützler MR, Moeller HB, Praetorius HA, Fenton RA: Vasopressin-independent targeting of aquaporin-2 by selective E-prostanoid receptor agonists alleviates nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 12949–12954, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.WareJoncas Z, Campbell JM, Martinez-Gálvez G, Gendron WAC, Barry MA, Harris PC, Sussman CR, Ekker SC: Precision gene editing technology and applications in nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 14: 663–677, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.June CH: Emerging use of CRISPR technology - Chasing the elusive HIV cure. N Engl J Med 381: 1281–1283, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rocca CJ, Cherqui S: Potential use of stem cells as a therapy for cystinosis. Pediatr Nephrol 34: 965–973, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]