Abstract

Background

Poor retention of participants in randomised trials can lead to missing outcome data which can introduce bias and reduce study power, affecting the generalisability, validity and reliability of results. Many strategies are used to improve retention but few have been formally evaluated.

Objectives

To quantify the effect of strategies to improve retention of participants in randomised trials and to investigate if the effect varied by trial setting.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science Core Collection (SCI‐expanded, SSCI, CPSI‐S, CPCI‐SSH and ESCI) either directly with a specified search strategy or indirectly through the ORRCA database. We also searched the SWAT repository to identify ongoing or recently completed retention trials. We did our most recent searches in January 2020.

Selection criteria

We included eligible randomised or quasi‐randomised trials of evaluations of strategies to increase retention that were embedded in 'host' randomised trials from all disease areas and healthcare settings. We excluded studies aiming to increase treatment compliance.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data on: the retention strategy being evaluated; location of study; host trial setting; method of randomisation; numbers and proportions in each intervention and comparator group. We used a risk difference (RD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) to estimate the effectiveness of the strategies to improve retention. We assessed heterogeneity between trials. We applied GRADE to determine the certainty of the evidence within each comparison.

Main results

We identified 70 eligible papers that reported data from 81 retention trials. We included 69 studies with more than 100,000 participants in the final meta‐analyses, of which 67 studies evaluated interventions aimed at trial participants and two evaluated interventions aimed at trial staff involved in retention. All studies were in health care and most aimed to improve postal questionnaire response. Interventions were categorised into broad comparison groups: Data collection; Participants; Sites and site staff; Central study management; and Study design.

These intervention groups consisted of 52 comparisons, none of which were supported by high‐certainty evidence as determined by GRADE assessment. There were four comparisons presenting moderate‐certainty evidence, three supporting retention (self‐sampling kits, monetary reward together with reminder or prenotification and giving a pen at recruitment) and one reducing retention (inclusion of a diary with usual follow‐up compared to usual follow‐up alone). Of the remaining studies, 20 presented GRADE low‐certainty evidence and 28 presented very low‐certainty evidence.

Our findings do provide a priority list for future replication studies, especially with regard to comparisons that currently rely on a single study.

Authors' conclusions

Most of the interventions we identified aimed to improve retention in the form of postal questionnaire response. There were few evaluations of ways to improve participants returning to trial sites for trial follow‐up. None of the comparisons are supported by high‐certainty evidence. Comparisons in the review where the evidence certainty could be improved with the addition of well‐done studies should be the focus for future evaluations.

Plain language summary

Strategies that might help to encourage people to continue to participate in a randomised trial (a type of scientific study)

Why is this review important?

Randomised trials are a type of scientific study typically used to test new healthcare treatments. In a randomised trial, people who agree to take part are randomly (by chance) put into one of two or more treatment groups and then studied for a period of time. The research team try to keep in touch with them to collect information about how they are doing. This 'follow up' can last from days to years depending on the trial, but the longer the trial lasts, the more difficult it can be. This might be because people are too busy to reply, are unable to come to a clinic, or just do not want to participate any longer. Keeping people in a trial is called 'retention'. If retention is poor, it can make the trial results less certain but most trials do not get data from all the people who started out in the trial.

The information gathered during follow‐up, sometimes called data, helps the trial team to determine which of the treatments being tested works the best. Often this information is collected directly from patients by asking them to complete a questionnaire or by asking them to come back for a clinic visit.

There are many ways to collect data from people in trials. These include using letters, the internet, telephone calls, text messaging, face‐to‐face meetings or the return of medical test kits. Research teams use different methods to try to collect data and it's important to know which strategies are effective and worthwhile, which is why we did this review to compare the success of different strategies.

How did we identify and evaluate the evidence?

We searched scientific databases for studies that compared strategies that research teams use to improve trial retention against each other or against not using such a strategy.We looked for studies that included participants from any age, gender, ethnic, language or geographic group. We then compared the results of the studies, and summarised the evidence that we had found. Finally, we rated our confidence in this evidence, based on factors such as the methods used in the studies and their size, and the consistency of findings across studies.

What did we find?

We identified 70 relevant articles, which reported 81 retention studies involving more than 100,000 participants, that had investigated different ways of trying to encourage randomised trial participants to provide data and stay in the trial. We organised these into broad comparison groups but, unfortunately, we are not able to say with confidence that any of the results we found is a true effect and not caused by other factors, such as flaws with the design of the studies. As such, the effect of ways to encourage people to stay involved in trials is still not clear and more research is needed to see if these retention methods really do work.

How certain is the evidence and how up‐to‐date is this review?

The strategies we identified were tested in randomised trials run in many different disease areas and settings but, in some cases, were tested in only one trial. None of the comparisons we made provided high quality evidence and more studies are needed to help provide more confidence for the results we did find. The evidence in this Cochrane Review is current to January 2020.

Summary of findings

Background

Randomised trials are considered the gold standard for evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of interventions. Poor retention (or high attrition) in randomised trials has serious consequences for the validity, reliability and usability of their results. Missing data, resulting from poor retention, are of particular concern if the data that are not missing are not at random. In other words, if there is a difference in the amount of missing data between the trial arms or amongst people who are more unwell. However, even if data are missing at random, this is also a potential problem because it will weaken the power of the trial and mean that more participants are needed to achieve a satisfactory sample size. It has been proposed that loss of less than 5% is not problematic but that more than 20% is a serious threat to validity, with anything in between also requiring attention (Fewtrell 2008; Schulz 2002). Recent work suggests that up to 50% of all trials have loss to follow‐up of more than 11% (Walters 2016).

Missing data from loss to follow‐up can be dealt with statistically by various methods including, for example, imputing values based on assumptions about the missing data to give a conservative estimate of the treatment effect (methods such as maximum likelihood estimation routines or multiple imputation). However, the risk of bias still remains when trials do not collect adequate data to give accurate estimates (Hollis 1999). Loss to follow‐up from randomised trials can sometimes go unreported and using different, but plausible, assumptions about outcomes for participants lost to follow‐up can change the results of randomised trials (Walsh 2014). However, rather than adjusting for missingness in the analysis of a trial, and inflating the sample size during recruitment, it seems much more sensible to mitigate the problem of poor retention by designing and evaluating approaches and strategies to maximise data collection. Not knowing how best to retain people in trials means trials will take longer (and cost more) and may expose additional patients to unnecessary risk or forgo the opportunity for others to receive effective treatments. Evidence for effective retention strategies would enable trial teams to include strategies in their trial which are likely to maximise trial design, efficiency and reduce research waste.

This is a substantially revised update of the first full version of this Cochrane Methodology Review (Brueton 2013). The scope of this review is restricted to interventions that are designed to maximise data collection from trial participants once they have been recruited and randomised. The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines define non‐retention as instances in which participants are prematurely ’off‐study’ (i.e. consent withdrawn or lost to follow‐up), and therefore outcome data cannot be obtained (Chan 2013). However, participants can still be 'on‐study' but not provide outcome data. Trial non‐retention is distinct from non‐adherence to the trial intervention, which refers to the degree to which the behaviour of trial participants corresponds to the intervention assigned to them. There are Studies Witihin A Trial (SWAT) for this (Bensaaud 2020), but it is not within the scope of this review.

Description of the methods being investigated

Strategies to improve trial retention include those designed to generate maximum data return or compliance and follow‐up procedures that aim to collect data from participants (e.g. weight measurements, blood tests). These strategies can include how outcomes are collected (e.g. postal or telephone); who collects outcomes (e.g. participant‐reported or routine data), when outcomes are collected and also consider, where outcomes are collected (e.g. postal questionnaire or clinic visits).

Objectives

To quantify the effects of strategies for improving retention of participants in randomised trials. A secondary objective is to investigate if the effects vary by trial setting.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials of interventions to improve retention of participants in randomised trials (hereafter referred to as retention trials).

Strategies to improve retention are designed to have an impact after participants are randomised to one of the intervention groups of the host and the retention trial, however, they could be delivered at any point (including at the time of recruitment, for example by modifying the information that focuses on retention that is presented to potential participants). Participants in the host trials cover a range of groups and can include (but not be limited to): patients, public, healthcare professionals, etc, and likewise the retention trials might include a range of designs such as individually‐randomised, cluster‐randomised, etc. We excluded trials of strategies that were intended to increase recruitment only, because these are covered by a complementary Cochrane Methodology Review (Treweek 2018). We excluded cohort studies with embedded randomised retention trials, which are the subject of a separate systematic review (Booker 2011).

When referring to embedded trials, we mean randomised trials of retention interventions (e.g. monetary incentives to improve response to postal questionnaires) that are set within a clinical trial (e.g. drug treatment for stroke). Clinical trials that embed retention trials are sometimes referred to as the host trial. Embedded trials are also sometimes referred to as Studies Within A Trial or SWATs. As per guidance by Treweek 2018, ‘a SWAT is a self‐contained research study that has been embedded within a host trial with the aim of evaluating or exploring alternative ways of delivering or organising a particular trial process’.

Types of data

We included retention trials within the context of a host randomised trial with participants from any age, gender, ethnic, language and geographic groups. We included unpublished and published participant retention data from randomised trials addressing health care (including all disciplines and disease areas) and non‐healthcare (education, social sciences) topics. We also included trials set in the community that were healthcare‐related. However, whilst the setting could be non‐health care, the outcomes being measured in the host randomised trial were required to be clinical‐ or health‐related. The retention trials were embedded in real trials (host trials) and not hypothetical trials.

Types of methods

Any intervention that aimed to improve retention of participants to a randomised trial. We considered any strategy aimed at increasing retention, whether it was directed towards the clinician, researcher or participant. The retention trials included at least one randomised comparison of two or more strategies to improve retention, or compared one or more strategies with usual study procedures. We also included trials with any combination of strategies to increase retention. Strategies could include any of the following:

data collection (e.g. shorter length of follow‐up or variation in follow‐up visit frequency);

participant strategies (e.g. monetary incentives, non‐monetary incentives, reminders, behavioural strategies, etc);

sites and site staff (e.g. monitoring approaches);

central study management (e.g. patient and public involvement);

study design (e.g. blinding and treatment preference).

For trials that simultaneously evaluated more than one intervention, unless designed as a factorial trial, or interaction effects were accounted for in the analysis, interventions had to be separated by at least six months to be considered eligible for the review. The reason for this was to account for contamination effects from carry over of previous intervention effects.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The proportion of participants retained at the primary analysis point as defined in each individual retention trial is our primary outcome. If the primary outcome was not predefined in a retention trial, we took the first time point reported for analysis. In most cases, this was final response. If retention at a number of time points was reported and no clear time point for the primary outcome for the retention trial was stated, we took data for the nearest time point to the intervention in the retention trial analyses. For studies that reported data captured 'without additional chasing' (i.e. no further standard follow‐up processes such as telephone calls were included before data collection), this was selected as the primary analysis point for data to be included in this review. For studies that delivered an intervention at trial recruitment, we took the total number of participants in the intervention trial as the number who consented as the denominator and the number retained as the numerator. All decisions about primary outcome timing were based on the retention trial publication and discussion within our team; we did not check study protocols or contact authors for clarification.

Secondary outcomes

This update includes no secondary outcomes. This is a change from the previous version of the review (Brueton 2013) which stated "Retention of participants at secondary analysis points" as a secondary outcome. However, because this is rarely reported, we decided to no longer include it as a secondary outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

We used the Online Resource for Recruitment research in Clinical triAls (ORRCA, www.orrca.org.uk) database to search for studies that had been published up to the end of December 2017. As the scope of this update had changed from that of the original review (Brueton 2013), we re‐ran the full search from database inception rather than only for the period required for the update (which would have been 2013 to 2020). The ORRCA database provides a comprehensive online database of published research (empirical and non‐empirical) about recruitment and/or retention to clinical research. ORRCA is populated from an extensive systematic search of the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE (Ovid), SCOPUS, CINAHL, psycINFO, and SCI‐EXPANDED and SSCI (via ISI Web of Science). The search strategy used to populate ORRCA was based on the original Cochrane Review of strategies to improve trial retention (Brueton 2013), but updated and extended to ensure capture of all relevant studies in this area (see below and Appendices for details). Eligible articles are categorised on the ORRCA database according to research methods and host study characteristics. We searched the ORRCA retention database in April 2020 to identify randomised evaluations of retention strategies that were nested within randomised trials (including factorial, cluster and cross‐over trials), patient preference studies, registries or where the host study type was unknown.

The search strategy used to develop ORRCA aimed to identify published research addressing retention challenges in healthcare and social science settings involving any method of follow‐up. At the time of updating this review, ORRCA only captured studies published until January 2018. Therefore we also ran the search strategy across all platforms described above, to capture studies published between January 2018 and January 2020.

Electronic searches

Each search comprised a filter to identify randomised trials plus free‐text terms and database subject headings relating to reducing loss to follow‐up or increasing retention (Appendix 1). Electronic databases that we searched included the following.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (to January 2020)

MEDLINE (OVID) (1950 to January 2020) (Appendix 1)

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; 1981 to January 2020) (Appendix 1)

PsycINFO (1806 to January 2020) (Appendix 1)

SCOPUS (to January 2020)

Web of Science Core Collection (SCI‐expanded, SSCI, CPSI‐S, CPCI‐SSH and ESCI) (1900 to January 2020)

Searching other resources

We also searched the SWAT repository (SWAT) to identify retention trials that were unpublished or ongoing.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All review authors were involved in the screening of titles and abstracts retrieved by the searches (in batches of 600) using a predesigned study eligibility screening form. A random 10% of each batch and all potentially eligible titles and abstracts were double screened by one of the review team (KG). We obtained full‐text papers for all potentially eligible studies for inclusion. All review authors were involved in independently assessing full‐text articles to determine if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with two review authors allocated to each full‐text article. We contacted study authors for electronic copies of papers that we could not access through library sources. We were able to obtain copies of all the potentially eligible papers, or abstracts, that we wanted to screen. When necessary, we sought information from the original investigators for potentially eligible trials where we wished to clarify eligibility. We resolved disagreements by discussion with a third review author (MAM or KG).

Data extraction and management

All review authors were involved in independently extracting data from included studies using a prespecified data extraction form, with two review authors allocated to each study. A third review author (MAM) checked the extractions for inconsistencies and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with another review author (KG). Data extracted for the host trial were: design, location, setting, population, intervention, and comparator. For the embedded retention trial, we extracted data on: randomised or quasi‐randomised; design; aim; definition of retention used; retention period; the source of the retention trial sample (e.g. all host participants, participants lost to follow‐up, etc), and participant details. The retention strategy details extracted included: type, theoretically based; description; frequency and timing; mode of delivery; co‐interventions; economic information; resource requirements, numbers and proportions of participants in the intervention and comparator groups of the retention trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All included studies (from previous version of review (n = 32) and this update (n = 39)) were assessed independently by two review authors (KG and MAM or ST) for risk of bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2008a), with any disagreements being resolved by a third member of the review team (ST or MAM). Information on risk of bias for all included studies is presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. When assessing studies on 'Blinding of participants and/or personal', we determined that if study authors noted that participants/personnel were not able to be blinded but that they were not given explicit knowledge of the retention trial and/or there was no way staff could use this knowledge to influence the objective outcome of retention, we determined these to be of low risk of bias for this domain. Likewise, when assessing 'Blinding of outcome assessment' we made a judgement as to whether the lack of blinding of outcome assessors would impact on their assessment of the objective outcome of retention. For the majority assessed, we considered studies to be low risk of bias on this domain. If studies were scored as low risk of bis on any one element, or unclear on any one element, this was the corresponding overall risk of bias rating.

We applied GRADE to all comparisons, including when only one study was available for a comparison (Guyatt 2008). For meta‐analyses, GRADE assessment data for the relevant meta‐analyses are provided in the relevant 'Summary of findings' table.

For single studies, we used the rules applied in the Cochrane recruitment review (Treweek 2018), with all studies initially assigned a high GRADE rating of certainty, with the following rules then applied to determine the overall rating.

Study limitations: downgrade all studies at high risk of bias by two levels; downgrade all studies at uncertain risk of bias by one level.

Inconsistency: assume no serious inconsistency.

Indirectness: assume no serious indirectness (all studies provided direct retention data).

Imprecision: downgrade all single studies by one level because of the sparsity of data; downgrade by a further level if the confidence interval is wide and includes a risk difference of zero.

Reporting bias: assume no serious reporting bias.

We provided an informative statement with each GRADE assessment following the guidance in GRADE Guideline 26 (Santesso 2020). This uses both the GRADE assessment and the effect size to produce an informative statement. We used the following rules regarding effect size.

Large effect: 10% or over

Moderate effect: 5% to 9%

Small important effect: 2% to 4%

Trivial, small unimportant effect or no effect: 0% to‐ 1%

We applied the same rules to effect size, regardless of whether the effect was an increase or a decrease in retention.

As per the Cochrane recruitment review (Treweek 2018), we did not exclude studies that were assessed to be at high risk of bias. However, where a high risk of bias study is the only study in a comparison, we do not describe them in the Results or Discussion sections due to the low confidence we have in their findings. We encourage more rigorous evaluations of these interventions but would discourage interpretation about their effects on retention from existing evaluations. The exception to this is if the data from high risk of bias studies could be included in a meta‐analysis alongside data from other studies and where a cumulative judgement on the certainty of the body of evidence using GRADE (as described above) could then be done.

Measures of the effect of the methods

We calculated risk difference (RD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for retention to determine the effect of strategies on this outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

For retention trials that randomised individuals and clusters, the unit of analysis was the participant. For cluster‐randomised trials that ignored clustering in the analysis, we inflated the standard errors (SEs) to avoid over precise estimates of effect as follows (Higgins 2008b).

We calculated the RD, 95% CI and SE based on participants in the usual way (i.e. ignoring clustering).

This SE was then inflated using the design effect to get an adjusted SE: adjusted SE = SE X√ design effect. With the design effect calculated as follows: design effect = 1 + (M ‐ 1) Intra‐cluster coefficient (ICC) where M = mean cluster size, ICC = the intracluster correlation coefficient.

Where published ICCs were not available, we used the mean ICC from appropriate external estimates for Land 2007. This was the mean of estimates for the return of EuroQol questionnaires (ICC = 0.054) from a source recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.3.4) (Higgins 2008b) and www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/documents/iccs-web.xls (last accessed 24 November 2020).

We entered the effect estimate and the new updated SE into Review Manager 5 using the generic inverse variance (RevMan 2012).

Where the number of participants randomised was not clearly stated in the included study report, we contacted the study authors for this information.

Dealing with missing data

For unpublished studies, we contacted study authors for data for the'R risk of bias' assessment, numbers randomised to each group and numbers retained in each group at the primary endpoint.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We agreed the presence of heterogeneity of the intervention effect where the Chi2 statistic has a significance level of 0.10 (representing a 10% chance of a Type I error). This figure was chosen as it counterbalances the relatively low power of the test. We also used the I² test (Higgins 2003). It represents the total variation across studies and is unlike the Chi2 test in that it is independent from the number of studies. Instead theI² is based on treatment effect. Heterogeneity was also explored through subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We would have assessed reporting bias using tests for funnel plot asymmetry if sufficient data were available (Egger 1997; Sterne 2008).

Data synthesis

We grouped included trials based on the type of intervention under investigation with groups directly informed by the ORRCA retention domains (https://www.orrca.org.uk/Uploads/ORRCA_Retention_Domains.pdf). We added a further domain within the 'Participants' domain to allow separate consideration of prompts and reminders targeting retention. This classification resulted in five broad categories with intervention functions grouped within them.

-

Data collection (Category A), interventions include:

questionnaire design;

data collection frequency/timing;

data collection location and method.

-

Participants (Category B), interventions include:

reminders ‐ intention to be received after a retention time point is reached;

prompts ‐ intention to be received before a retention time point is reached;

monetary incentives and rewards‐ includes both incentives (i.e. not conditional on behaviour) and rewards (i.e. is conditional on behaviour);

non‐monetary incentives;

maintaining participant engagement;

behavioural intervention.

-

Sites and site staff (Category C), interventions include:

prompt;

monitoring visits.

-

Central Study Management (Category D), interventions include:

patient public involvement.

-

Study design (Category E), interventions include:

impact of recruitment;

blinding and treatment preference.

We present the results as RD, pooled using a random‐effects model for all meta‐analyses with more than one included study,and with associated CIs where sufficient data were available. If heterogeneity was detected and could not be explained by subgroup or sensitivity analyses, we did not pool results.

For factorial trials, the data for different categories of interventions were included as separate trial comparisons. For multiple retention trials conducted within the same host trial that were not designed to allow for interaction effects between interventions (i.e. did not stratify at randomisation or account for interaction effects in analysis), we pre‐specified the requirement for interventions to be delivered at least six months apart in order to minimise the potential for any intervention interaction effects. In order to minimise interaction effects, we chose not to include data in the meta‐analyses from trials that had evaluated interventions within six months of each other that had not accounted for the interaction effects in the analysis. This resulted in three studies and data from a further four studies (with multiple evaluations) being omitted from our analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to explore the following factors in subgroup analyses assuming enough studies were identified within each comparison.

Type of design used to evaluate the retention strategy (randomised versus quasi‐randomised)

Setting of the host trial (e.g. primary versus secondary care, healthcare setting versus non‐healthcare setting)

Disease area of the host trial (e.g. oncology versus ante‐natal)

Duration of follow‐up (e.g. short versus long term)

Value of monetary incentive (e.g. £5 versus £10 etc)

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of the results, we planned sensitivity analyses that excluded quasi‐randomised retention trials.

Results

Description of studies

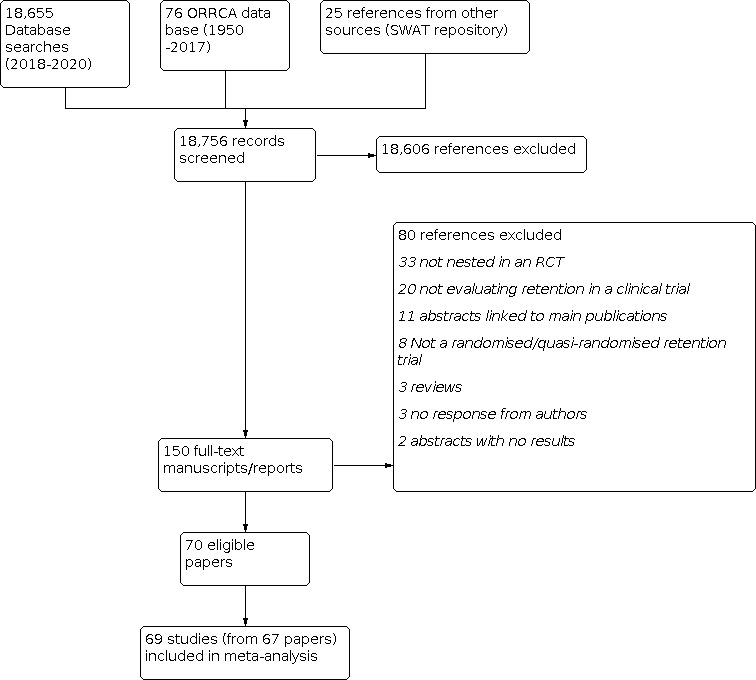

The studies are described in the Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, Characteristics of ongoing studies, and Characteristics of excluded studies tables. We identified 18,756 abstracts, titles and other records and sought the full text for 150 records to confirm eligibility. In total, 70 papers (reporting data from 81 retention trials) were considered eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). The studies were conducted in eight countries with two multi‐national studies. The majority of studies (n = 53) were conducted in the UK followed by the USA (n = 10) (Table 17). Of these 70 papers, 68 evaluated interventions targeting trial participants and two evaluated interventions targeting individuals involved in trial retention. A total of 101,689 participants were included across the retention trials, which included all participants originally randomised to the retention trial. Included retention trials were conducted in a broad spectrum of clinical conditions across a range of different settings including primary care, secondary care, and community settings. However, similar to the previous version of this review (Brueton 2013), the included studies were predominantly composed of studies evaluating interventions to improve questionnaire return (n = 70) rather than clinic attendance (n = 2).

1.

1 Included studies flow diagram.

1. Countries where the included studies took place.

| Country | Number of studies |

| Australia | 1 |

| Canada | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| France | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| UK | 53 |

| USA | 10 |

| Multinational | 2 (one involving UK and Ireland and one involving the USA and Canada). |

The majority of the included trials (42 host trials) included a single retention trial. Some of the included studies reported multiple retention trials (i.e. tested more than one intervention) within one publication (non‐factorial) such as Dinglas 2015 (two retention trials), Edwards 2016 (three retention trials), Goulao 2020 (four retention trials), and Keding 2016 (three retention trials). Other retention trials were reported separately but embedded within the same host trial. These included trials by Avenell 2004 and MacLennan 2014 in the RECORD fracture prevention trial; Cockayne 2017 and Rodgers 2019 in the REFORM trial; Khadjesari 2011 and McCambridge 2011 in the Down your Drink Trial; Bailey 2013 in a feasibility study for the Sex unzipped website; McColl 2003 ‐ Trial 1 and McColl 2003 ‐ Trial 2 in the COGENT trial; Mitchell 2011, Mitchell 2012, and Bell 2016 in the SCOOP trial; Cochrane 2020, James 2020 and Whiteside 2019 in the OTIS trial; and Mitchell 2020a and Mitchell 2020b in the KReBS trial.

There was too much variability and not enough depth (i.e. meaningful replication) in the data set to allow us to conduct any of our planned subgroup analyses.

Two studies (Letley 2000 and Sutherland 1996) are awaiting classification. We were unable to include them due to a lack of information on the number of participants randomised to each arm (Letley 2000), or whether the feasibility they report ahead of the full trial was also randomised (Sutherland 1996).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2 and Figure 3. Authors of trials included in the meta‐analysis reported their studies as either randomised (n = 70) or quasi‐randomised (n = 2). One study included both randomised and quasi‐randomised retention trials (Edwards 2016). The overall risk of bias was considered low for 14 studies, unclear for 50 studies and high for eight studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Effect of methods

We only report comparisons including studies (single studies or overall comparisons) at low or unclear risk of bias in these results. The list of all 52 comparisons, including those of high risk of bias, is included in Table 18, Table 19, Table 20, Table 21 and Table 22. The categorisation of interventions into categories, based on the ORRCA retention domains, was not always clear and was largely informed by the original study authors' intention as described or implied within their report.

2. Data collection (Category A).

| Sub‐domains | Study ID | Intervention | Control |

| 1A. Questionnaire design: Questionnaire length | |||

| Dorman 1997 | New questionnaire (Shorter version) |

Standard questionnaire | |

| Edwards 2004 | New questionnaire (Shorter version) |

Standard questionnaire | |

| Subar 2001 | New questionnaire (Shorter version) |

Standard questionnaire | |

| 2A. Questionnaire design: Addition of a diary to usual follow‐up | |||

| Griffin 2019 | Diaries follow‐up | Postal questionnaires follow‐up | |

| Marques2013 | Resource use log to prospectively record their use of health services | No resource use log | |

| 3A. Questionnaire design: Question order, condition first vs generic first question | |||

| McColl 2003 | Condition‐specific measures of quality of life preceded generic instruments | Questionnaires in a reverse order | |

| 4A. Data collection frequency and timing: Timing of questionnaire delivery | |||

| Renfroe 2002 | Timing of postal questionnaire, cover letter signatory, express | Regular mail, non‐monetary incentive | |

| 5A. Data Collection Location and Method: Postal follow‐up vs clinic follow‐up | |||

| Greig 2017 | Postal follow‐up | Clinic follow‐up | |

| 6A. Data Collection Location and Method: Telephone follow‐up vs postal questionnaire | |||

| Couper 2007 | Telephone follow‐up | Postal questionnaire | |

| Marsh 1999 (Postal trial) | Postal follow‐up with an incentive | Postal follow‐up without incentive | |

| Marsh 1999 (Telephone trail) | Telephone follow‐up with an incentive | Telephone follow‐up without incentive | |

| 7A. Data Collection Location and Method: First class vs second class outward mailing | |||

| Sharp 2006 | First‐class post | Second class | |

| 8A. Data Collection Location and Method: Return postage | |||

| Sharp 2006 | Preaddressed second class stamped envelope | Business reply envelope | |

| Kenton 2007 | 'high priority' stamp to the mailing | Business format mailing | |

| Dinglas 2015 (Mail trial) | Personalised postal follow‐up | Generic postal follow‐up | |

| 9A. Data Collection Location and Method: Use of self‐sampling kits | |||

| Tranberg 2018 | Received a modified second reminder, a leaflet, and a self‐sampling kit. | received the same material as those in the directly mailed group but received no kit | |

3. Participants (Category B).

| Sub‐domains | Study ID | Intervention | Control |

| 10B. Reminders: electronic reminder vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Ashby 2011 | Additional electronic reminder in follow‐up | Usual follow‐up | |

| Starr 2015 (Email reminder) | Email reminder | Postal email reminder | |

| Starr 2015 (SMS text pre‐notification) | Prenotification reminder | Usual follow‐up | |

| 11B. Reminders: action oriented electronic reminder vs standard electronic reminder | |||

| Edwards 2016 (photo trial) | The personalised photo on the letter | Usual letter | |

| Edwards 2016 (pre‐call trial) | Active reminder | Usual reminder | |

| 12B. Reminders: personalised reminder vs non‐personalised reminder | |||

| Nakash2007 | Calendar | Usual follow‐up | |

| Bradshaw 2020 | Intervention group 1 received an SMS message the day before the email with the link to the questionnaire. | No SMS | |

| 13B. Reminders: telephone reminder vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Severi 2011 | Telephone call reminder | Usual follow‐up | |

| 14B. Reminders: telephone reminder vs postal reminder | |||

| Tai 1997 | Telephone reminder | Postal reminder | |

| 15B. Prompts: electronic prompt vs no prompt | |||

| Bradshaw 2020 | Intervention group 1 received an SMS message and a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher sent by post before the 24 months visit. Intervention group 2 received a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher given at the visit. |

No voucher | |

| Clark 2015 | Received an SMS or e‐mail to return a study questionnaire | Received no electronic prompt to returns a study questionnaire | |

| Keding 2016 | Text message prompt Prompt Reminder |

Usual follow‐up Reminder Usual follow‐up |

|

| Man 2011 | Electronic reminder | No reminder | |

| Starr 2015 (Email reminder) | Email reminder | Postal email reminder | |

| Starr 2015 (SMS text pre‐notification) | Prenotification reminder | Usual follow‐up | |

| 16B. Prompts: telephone prompt vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Edwards 2016 (Email trial) | Addition of an email as prompt | Usual Follow‐up | |

| MacLennan 2014 | Received a telephone call from the trial office ahead of the reminder questionnaire in addition to the usual reminder schedule | Received the usual reminder schedule only | |

| 17B. Prompts: Prenotification card vs no card | |||

| Treweek 2020a | Pre‐notification card sent around 1 month before | No pre‐notification card | |

| 18B. Prompts: sticker vs no sticker | |||

| Goulao 2020 | Received a logo sticker on questionnaire envelopes | Received no sticker | |

| 19B. Prompts: personalised prompt vs no prompt | |||

| Cochrane 2020 | Personalised reminder | Non‐personalised reminder | |

| Mitchell 2020 | Personalised text message | No personalised text message | |

| Nakash 2007 | Calendar | Usual follow‐up | |

| 20B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Bauer 2004 | Interventions group 1 received an incentive of US$10 Interventions group 2 received an incentive of US$2 |

Received no incentive | |

| Gates 2009 | £5 gift voucher | Received no gift voucher | |

| Kenyon 2005 | Monetary incentive (£5 voucher) | No incentive | |

| 21B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives to all trial arms | |||

| Bauer 2004 | Interventions group 1 received an incentive of US$10 Interventions group 2 received an incentive of US$2 |

Received no incentive | |

| Bradshaw 2020 | Intervention group 1 received an SMS message and a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher sent by post before the 24‐month visit. Intervention group 2 received a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher given at the visit. |

No voucher | |

| 22B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives vs addition of monetary reward | |||

| Bradshaw 2020 | Intervention group 1 received an SMS message and a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher sent by post before the 24 months visit. Intervention group 2 received a further £10 high‐street shopping voucher given at the visit. |

No voucher | |

| Cook 2020 | £20 gift voucher given to study at the end of the recruitment visit | A conditional offer of monetary incentive | |

| Dorling 2020 | Received the first paper letter to parents included a promise of an incentive (£15 gift voucher redeemable at some shops) after receipt of a completed form. | Received the first paper letter to parents would enclose the incentive (£15 gift voucher redeemable at high‐street shops) before the receipt of a completed form | |

| Young 2020 | Addition of monetary incentive (£5 multistore voucher) | An offer of incentive (i.e. Conditional vs unconditional £5 multistore voucher) | |

| 23B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary reward vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Marsh 1999 (Clinic trial) | Clinic visit with an incentive (£2 voucher) | Clinic visit without incentive | |

| Marsh 1999 (Postal trial) | Postal follow‐up with incentive (£2 voucher) | Postal follow‐up without incentive | |

| Marsh 1999 (Telephone trail) | Telephone follow‐up with incentive (£2 voucher) | Telephone follow‐up without incentive | |

| Watson 2017 |

Intervention group 1 received unconditional (£5 gift voucher) at 12 but not 24 months. Intervention group 2 received unconditional (£5 gift voucher) at 12 and 24 months. Intervention group 3 received unconditional (£5 gift voucher) at 24 but not 12 months. |

No voucher | |

| Arundel 2019 | An offer of conditional monetary incentive (£10 cash reliant on providing in addition to the £10 gift voucher routinely provided) | Usual follow‐up (£10 gift voucher routinely provided) | |

| 24B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary rewards to all trial arms | |||

| Hardy 2016 | An offer of conditional monetary incentive (£10 gift voucher) | Later offer of conditional monetary incentive (£10 gift voucher) | |

| 25B. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives vs lottery | |||

| Kenton 2007 | Monetary incentive (CAN$2 coin mailed with the questionnaire or draw for a CAN$50 gift certificate upon questionnaire receipt) | Lottery | |

| 26B. Monetary incentives: lottery vs usual follow‐up | |||

| No incentive | |||

| 27B. Monetary incentives: addition of lottery to both trial arms | |||

| Henderson 2010 | An offer of winning voucher (winning 1 of 25 £20 shopping vouchers or winning one £500 shopping voucher) | No incentive | |

| 28B. Non‐monetary incentives: addition of pen vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Bell 2016 | Addition of a pen | No pen | |

| Cunningham‐Burley 2020 | Branded pen with their questionnaire | No pen | |

| James 2020 | Pen with trial invitation pack | No pen | |

| Mitchell 2020b | Addition of a pen | No pen | |

| Sharp 2006 | Pen | No pen | |

| 29B. Non‐monetary incentives: addition of societal benefit message vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Severi 2011 | Fridge magnet and benefit to society message | Usual follow‐up | |

| 30B. Non‐monetary incentives: certificate of appreciation vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Renfroe 2002 | Timing of postal questionnaire, cover letter signatory, express mail | Regular mail and non‐monetary incentive. | |

| 31B. Maintaining participant engagement: newsletter vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Goulao 2020 | Received a tested a theoretically informed newsletter sent before the questionnaire | Received no newsletter | |

| MARMOTH trial | Newsletter one month before the 24‐month paper follow‐up questionnaire | No newsletter | |

| Mitchell 2012 | Invitation mailing packs with a white envelope | Invitation mailing packs with a brown envelope | |

| Rodgers 2019 | Newsletter + handwritten posit it notes Newsletter + printed posit it notes Newsletter only Handwritten posit it notes only Printed posit it note only |

Usual follow‐up | |

| 32B. Maintaining participant engagement: offer of receiving trial results vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Cockayne 2005 | Offered the result of the trial in a questionnaire | No offer of knowing the results | |

| 33B. Maintaining participant engagement: cover letter including a social incentive vs standard cover letter | |||

| James 2020 |

Intervention group 1 received a branded pen and a standard cover letter. Intervention group 2 received a branded pen and a social incentive cover letter. Intervention group 3 received no pen and a social incentive cover letter. |

Control group received no pen, standard cover letter. | |

| 34B. Maintaining participant engagement: personalised cover letter vs usual cover letter | |||

| Edwards 2016 (Email trial) | Addition of an email as prompt | Usual follow‐up | |

| Edwards 2016 (photo trial) | Personalised photo on the letter | Usual letter | |

| Edwards 2016 (pre‐call trial) | Active reminder | Usual reminder | |

| 35B. Maintaining participant engagement: varying signatory on cover letter | |||

| Renfroe 2002 | Timing of postal questionnaire, cover letter signatory, express mail | Regular mail and non‐monetary incentive. | |

| 36B. Maintaining participant engagement: addition of a deadline vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Gatellari 2004 | Cover letter advising return within 1‐week | Standard cover letter | |

| 37B. Maintaining participant engagement: addition of an estimate of time to complete vs no addition | |||

| Marson 2007 | Cover letter though post with the questionnaire that included an estimate of the length of time that it may take to complete | Standard cover letter with no indication of length of time required | |

| 38B. Maintaining participant engagement: brown vs white envelope | |||

| Mitchell 2011 | Invitation mailing packs with a white envelope | Invitation mailing packs with a brown envelope | |

| 39B. Maintaining participant engagement: post‐it notes vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Lewis 2017 | Addition of a post‐it note | Usual follow‐up | |

| Rodgers 2019 | Newsletter + handwritten posit it notes Newsletter + printed posit it notes Newsletter only Handwritten posit it notes only Printed posit it note only |

Usual follow‐up | |

| Tilbrook 2015 | Addition of a post‐it note | Usual follow‐up | |

| 40B. Maintaining participant engagement: inclusion of trial newspaper article vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Salvesen 1992 | Newspaper article | Usual follow‐up | |

| 41B. Maintaining participant engagement: frequency of telephone contact | |||

| Glassman 2020 | Received telephone calls at baseline, six months, and at annual visits after that (annual contact) | Received a call at baseline only (baseline contact) | |

| 42B. Maintaining participant engagement: request for collateral (concomitant) | |||

| Cunningham 2004 |

Intervention group1 were asked to provide a collateral. Intervention group2 asked to provide collateral and told that there was a 50% chance that the collateral would be contacted. All those respondents asked for collateral were told that the collateral would receive a CAN$20 payment for a brief telephone interview. |

Not asked to provide a collateral | |

| 43B. Behavioural interventions: theory informed cover letter vs usual cover letter | |||

| AMBER trial | Received a tested a theoretically informed letter sent with the questionnaire | Received a standard letter | |

| Goulao 2020 | Theory informed letter to follow‐up | Usual letter follow‐up | |

| Goulao 2020 (replication) | Theory informed letter to follow‐up | Usual letter follow‐up | |

| OPAL trial | Received a tested a theoretically informed letter sent with the questionnaire | Received a standard letter | |

| 44B. Behavioural interventions: motivational interviewing vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Bean 2018 | Theory informed to follow‐up | Usual follow‐up | |

4. Sites and site staff (Category C).

| Sub‐domains | Study ID | Intervention | Control |

| 45C. Prompts: site prompts for upcoming assessments vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Land 2007 | Received a monthly reminder to sites listing participants who were due to have a measure in the next three months | Received no reminder | |

| 46C. Monitoring visits: on‐site monitoring vs no visit | |||

| Lienard 2006 | Centres received a systematic on‐site visit (Visited group) | Did not receive a systematic on‐site visit (Non‐visited group) | |

5. Central Study Management (Category D).

| Sub‐domains | Study ID | Intervention | Control |

| 47D. Patient Public Involvement: peer‐led follow‐up strategy vs usual follow‐up | |||

| Fouad 2014 | Peer‐led strategy | Usual follow‐up | |

6. Study design (Category E).

| Sub‐domains | Study ID | Intervention | Control |

| 48E. Impact of recruitment: video‐enhanced patient information vs standard information | |||

| Brubaker 2019 | Change to information provided at recruitment | Standard information | |

| 49E. Impact of recruitment: optimised information vs standard information | |||

| Cockayne 2017 | Optimised patient information | Standard patient information | |

| Guarino 2006 | Change to information provided at recruitment | Standard information | |

| 50E. Impact of recruitment: addition of optimised information to both arms | |||

| Cockayne 2017 | Optimised patient information | Standard patient information | |

| 51E. Impact of recruitment: pen vs no pen | |||

| Whiteside 2019 | Non‐monetary incentive | Usual practice (at recruitment) | |

| 52E. Blinding and treatment preference: open vs blind trial design | |||

| Avenell 2004 | Open design | Blinded design | |

'Summary of findings' tables were produced for all interventions where more than one study evaluated effectiveness. This provided 16 in total: Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13, Table 14, Table 15 and Table 16.

Summary of findings 1. Questionnaire design: short vs usual questionnaire.

| Short questionnaire compared with long questionnaire for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: short questionnaire Comparison: usual questionnaire | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Short questionnaire | Usual questionnaire | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

As measured | ||||

| Lowa | RR 1.01 (0.89 to 1.14) | 3252 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 25 per 100 (22 to 29 ) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 51 per 100 (45 to 57) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 81 per 100 (71 to 91) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of a short questionnaire (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | |||||

Summary of findings 2. Questionnaire design: addition of diary to usual follow‐up vs usual follow‐up.

| Addition of diary to usual follow‐up compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: diary Comparison: no diary | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Diary | No diary | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | 9906 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate | |

| 25 per 100 | 24 per 100 (24 to 25) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 49 per 100 (48 to 49) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 78 per 100 (77 to 78) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of not including a diary (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

| aWe selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | |||||

Summary of findings 3. Data collection location and method: telephone follow‐up vs postal questionnaire.

| Telephone follow‐up compared with postal questionnaire for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: telephone follow‐up Comparison: postal questionnaire | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Telephone follow‐up | Postal questionnaire | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.04 (0.94 to 1.17) | 1006 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| 25 per 100 | 26 per 100 (24 to 29) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 52 per 100 (47 to 59) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 83 per 100 (75 to 94) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of telephone follow‐up (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | |||||

Summary of findings 4. Data collection location and method: return postage.

| Return postage compared with control intervention for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: various return postage strategies Comparison: control intervention | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Various return postage strategies (such as free post versus second class stamp; high priority mail stamp versus usual postage; and personal form) | Standard return postage | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.06 (0.99 to 1.15) | 1543 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| 25 per 100 | 27 per 100 (25 to 29) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 53 per 100 (50 to 58) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 85 per 100 (79 to 92) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | |||||

Summary of findings 5. Reminders: electronic reminder vs usual follow‐up.

| Electronic reminder compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: electronic reminder Comparison: usual follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Electonic reminder | Usual follow‐up | |||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.01 (0.95 to 1.09) | 790 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 25 per 100 (24 to 27) | |||||

| Mediuma | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 51 per 100 (48 to 55) | |||||

| Higha | ||||||

| 80 per 100 | 81 per 100 (76 to 87) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of an electronic reminder (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | ||||||

Summary of findings 6. Prompts: Electronic prompt vs no prompt.

| Electronic prompt compared with no prompt for trial retention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: electronic prompt Comparison: no prompt | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Electronic prompt | No prompt | |||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 2897 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 26 per 100 (25 to 27) | |||||

| Mediuma | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 52 per 100 (49 to 54) | |||||

| Higha | ||||||

| 80 per 100 | 82 per 100 (78 to 86) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of electronic prompts (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | ||||||

Summary of findings 7. Prompts: Telephone prompt vs usual follow‐up.

| Telephone prompt compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: telephone prompt Comparison: usual follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Telephone prompt | Usual follow‐up | |||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.02 (0.85 to 1.22) | 943 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 26 per 100 (21 to 31) | |||||

| Mediuma | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 51 per 100 (43 to 61) | |||||

| Higha | ||||||

| 80 per 100 | 82 per 100 (68 to 98) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of telephone prompts (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | ||||||

Summary of findings 8. Prompts: personalised prompt vs usual follow‐up.

| Personalised prompt compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: personalised prompt Comparison: usual follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Personalised prompt | Usual follow‐up | |||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 0.97 (0.89 to 1.07) | 701 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 24 per 100 (22 to 27) | |||||

| Mediuma | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 49 per 100 (45 to 54) | |||||

| Higha | ||||||

| 80 per 100 | 78 per 100 (71 to 86) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of personalised prompts (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | ||||||

Summary of findings 9. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives vs usual follow‐up.

| Addition of monetary incentives compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: monetary incentives Comparison: usual follow‐up | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Monetary incentives | Usual follow‐up | |||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.20 (1.06 to 1.36) | 3166 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | ||

| 25 per 100 | 30 per 100 (27 to 34) | |||||

| Mediuma | ||||||

| 50 per 100 | 60 per 100 (53 to 68) | |||||

| Higha | ||||||

| 80 per 100 | 96 per 100 (85 to [109) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The effect of monetary incentives (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | ||||||

Summary of findings 10. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary incentives vs addition of a monetary reward.

| Addition of monetary incentives compared with addition of a monetary reward for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: monetary incentive Comparison: monetary reward | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Monetary incentive | Monetary reward | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.00 (0.91 to 1.09) | 3765 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| 25 per 100 | 25 per 100 (23 to 28) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 50 per 100 (46 to 55) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 80 per 100 (73 to 87) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

| a We selected low, medium and high illustrative retention levels of 25%, 50% and 80% based on prior experience with trial retention and evidence from the literature. For example, it has been previously stated that it is common for up to 20% trial participants to drop out before the trial finishes (Walsh 2015), as such we set the upper limit of good retention as 80%. The other extreme of 25% was informed by evidence that some trials (largely internet based) can have retention as low as 10% to 25% (Murray 2009). The mid point of 50% was a judgement made by the review team and was deemed appropriate given the evidence for the other parameters. | |||||

Summary of findings 11. Monetary incentives: addition of monetary reward vs usual follow‐up.

| Addition of monetary reward compared with usual follow‐up for trial retention | |||||

|

Patient or population: trial participants being followed up for data collection Settings: any setting Intervention: monetary reward Comparison: usual follow‐up | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Monetary reward | Usual follow‐up | ||||

|

Retention [follow‐up] |

Lowa | RR 1.02 (0.96 to 1.09) | 1159 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | |

| 25 per 100 | 26 per 100 (24 to 27) | ||||

| Mediuma | |||||

| 50 per 100 | 51 per 100 (48 to 55) | ||||

| Higha | |||||

| 80 per 100 | 82 per 100 (77 to 87) | ||||