Active efflux confers intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including old disused molecules. Beside resistance, intracellular survival is another reason for failure to eradicate bacteria with antibiotics.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic, drug efflux, efflux inhibitor, intracellular bacteria

ABSTRACT

Active efflux confers intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including old disused molecules. Beside resistance, intracellular survival is another reason for failure to eradicate bacteria with antibiotics. We evaluated the capacity of polyaminoisoprenyl potentiators (designed as efflux pump inhibitors [EPIs]) NV716 and NV731 compared to PAβN to restore the activity of disused antibiotics (doxycycline, chloramphenicol [substrates for efflux], and rifampin [nonsubstrate]) in comparison with ciprofloxacin against intracellular P. aeruginosa (strains with variable efflux levels) in THP-1 monocytes exposed over 24 h to antibiotics alone (0.003 to 100× MIC) or combined with EPIs. Pharmacodynamic parameters (apparent static concentrations [Cs] and maximal relative efficacy [Emax]) were calculated using the Hill equation of concentration-response curves. PAβN and NV731 moderately reduced (0 to 4 doubling dilutions) antibiotic MICs but did not affect their intracellular activity. NV716 markedly reduced (1 to 16 doubling dilutions) the MIC of all antibiotics (substrates or not for efflux; strains expressing efflux or not); it also improved their relative potency and maximal efficacy (i.e., lower Cs; more negative Emax) intracellularly. In parallel, NV716 reduced the persister fraction in stationary cultures when combined with ciprofloxacin. In contrast to PAβN and NV731, which act only as EPIs against extracellular bacteria, NV716 can resensitize P. aeruginosa to antibiotics whether they are substrates or not for efflux, both extracellularly and intracellularly. This suggests a complex mode of action that goes beyond a simple inhibition of efflux to reduce bacterial persistence. NV716 appears to be a useful adjuvant, including to disused antibiotics with low antipseudomonal activity, to improve their activity, including against intracellular P. aeruginosa.

TEXT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the so-called ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp.) pathogens (1) that harbor multiple mechanisms of drug resistance. It is considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a critical priority species for the search for innovative therapies (2).

P. aeruginosa has acquired a series of resistance mechanisms to all classes of commonly used antibiotics (β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and, more recently, polymyxins). Moreover, it is also innately resistant to many antibiotics, mainly due to poor outer membrane permeability and/or active efflux (3). Four main efflux systems, named MexAB-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, MexEF-OprN, and MexXY-OprM, have been associated with increased MICs for a broad range of antimicrobial agents (4), bringing the active concentrations above the levels that can be achieved in the serum of patients. This explains why drugs like tetracyclines or chloramphenicol cannot be used against P. aeruginosa or other Gram-negative bacteria, although they are capable of binding to their respective target in these bacteria when tested in acellular systems (5, 6).

Another, often neglected, reason for antibiotic failure against P. aeruginosa is the capacity of this bacterium to adopt specific lifestyles, such as intracellular survival. Although considered an extracellular pathogen, P. aeruginosa has been shown by many researchers as capable of invading and surviving inside epithelial (7, 8) and phagocytic cells (9–11) in vitro, as well as in lung epithelial cells and macrophages in vivo (12, 13). In these intracellular niches, bacteria are protected from the host humoral immune defenses but also from antibiotics, which need to have access, accumulate, and express their activity in the infected subcellular compartment (14, 15). Moreover, they can adopt dormant phenotypes that do not respond anymore to antibiotics, like persisters. These are subpopulations of otherwise antibiotic-susceptible bacteria that switch to a transient nondividing phenotype to survive high concentrations of bactericidal antibiotics (16). We have recently provided evidence for another species, Staphylococcus aureus, that bacteria surviving antibiotics intracellularly are persisters, explaining why antibiotics fail to eradicate them (17). Preliminary data suggest that the same may hold true for P. aeruginosa (18).

As P. aeruginosa resistance is worryingly increasing, few new antibiotics have been approved over the last years and are essentially new derivatives in existing classes with improved activity or reduced susceptibility to resistance mechanisms (19). In this context, reviving old and disused antibiotics may appear as an attractive strategy (20), which should be accompanied by an in-depth reassessment of their efficacy according to the modern standards imposed by pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) concepts, including in models of persistent infections like intracellular survival.

One of the approaches proposed to increase the potency of drugs that are substrates for efflux is to combine them with efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) (19). PAβN (MC 207,110; phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide [21]) and CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone [22]) have been widely used in vitro to increase the accumulation of antibiotics within Gram-negative bacteria, but their toxicity and inadequate pharmacokinetic properties preclude clinical applications (23, 24). Efforts have been made to synthesize new efflux pump inhibitors with improved safety profiles (25). Among them, polyaminoisoprenyl compounds NV716 and NV731 (see the chemical structures in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) demonstrated their capacity to restore chloramphenicol activity against Enterobacteria spp. (26), and NV716 also restored chloramphenicol and doxycycline activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (27) and florfenicol activity against Bordetella bronchiseptica (28).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of NV716 in comparison with that of NV731 (less potent against P. aeruginosa [27]) and PAβN (reference EPI) in combination with old and disused antibiotics against the intracellular forms of P. aeruginosa, using strains expressing or not expressing efflux pumps to infect THP-1 monocytes. We exploited a previously established in vitro pharmacodynamic model (11) that allows comparing key pharmacological descriptors of antibiotic intracellular activity, namely, their relative potency and maximal efficacy (29). For antibiotics, we selected doxycycline and chloramphenicol (both substrates for efflux [see Table S1] and for which preliminary data exist regarding the beneficial effect of NV716 [27]), rifampin (not impacted by efflux), and ciprofloxacin, selected as the most active drug against intracellular P. aeruginosa in this preestablished in vitro model (11). The results were examined in the light of the effect of these potentiators on antibiotic MIC and on the selection of persisters in broth culture.

We showed that NV716, contrary to NV731 and PAβN, was capable of increasing the relative potency and maximal efficacy of these antibiotics against intracellular P. aeruginosa, whether substrates or not for efflux and in strains expressing or not efflux pumps. These effects were related to drastic reductions in MIC and in persister fractions. Altogether, these data suggest that NV716 does not act simply by inhibiting efflux but could be a useful adjuvant, including to disused antibiotics with low antipseudomonal activity, to improve their activity even against intracellular P. aeruginosa.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

Table 1 shows the MICs of antibiotics against PAO1, PAO509 (deleted in the genes encoding five efflux pumps), and 205-2 and BV1 (two clinical isolates expressing a nonfunctional and a functional MexAB-OprM efflux pump, respectively), in the absence of or in the presence of 20 mg/liter (38 μM) PAβN, or 4 mg/liter (10 μM) NV731 or NV716. These concentrations were selected because they have been commonly used in previous works (21, 27). In control conditions (no potentiator), ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and chloramphenicol showed much lower MICs against PAO509 than against PAO1, in accordance with the fact they are substrates for efflux (see Table S1). Conversely, the MIC of rifampin remained unchanged in strains expressing efflux or not. BV1 was less susceptible than PAO1 to ciprofloxacin and doxycycline and more susceptible to chloramphenicol, while 205-2 was less susceptible to ciprofloxacin only. PAβN and NV731 reduced antibiotic MICs in a few cases, while NV716 systematically decreased them, except for ciprofloxacin in PAO509, the MIC of which was already very low. Of note, the effect of NV716 was as (or even more) important for testing strains that do not express efflux pumps as for those that do, as well as when using rifampin (not impacted by efflux) or other antibiotics (all substrates for efflux).

TABLE 1.

MICs of antibiotics and adjuvants (EPIs) alone or combined against reference strains and clinical isolates in broth

| Strain | Phenotype | Reference | Antibioticb | AB alone (mg/liter) | PAβN alone (μM) | NV731 alone (μM) | NV716 alone (μM) | MIC in mg/liter (fold dilution decrease versus antibiotic alone)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB+PAβNc | AB+NV731c | AB+NV716c | ||||||||

| PAO1 | Wild type | 48 | CIP | 0.25 | >200 | >250 | 50 | 0.06 (2) | 0.06 (2) | 0.03 (3) |

| DOX | 16 | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 1 (4) | ||||||

| CHL | 32 | 8 (2) | 16 (1) | 1 (5) | ||||||

| RIF | 16 | 8 (1) | 8 (1) | 0.125 (7) | ||||||

| PAO509 | PAO1[Δ(MexAB-OprM), Δ(MexCD-OprJ), Δ(MexJK), Δ(MexXY), Δ(MexEF-OprN)] | 49 | CIP | 0.016 | >200 | >250 | 25 | 0.008 (1) | 0.016 (0) | 0.008 (1) |

| DOX | 1 | 1 (0) | 0.125 (3) | 0.03 (4) | ||||||

| CHL | 2 | 2 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.125 (4) | ||||||

| RIF | 16 | 4 (2) | 8 (1) | 0.06 (7) | ||||||

| BV1 | Clinical isolate (expressing truncated, nonfunctional MexAB-OprM) | 45 | CIP | 1 | >200 | >250 | 50 | 1 (0) | 0.5 (1) | 0.125 (3) |

| DOX | 64 | 8 (3) | 2 (5) | 0.125 (9) | ||||||

| CHL | 8 | 4 (1) | 0.5 (4) | 0.06 (7) | ||||||

| RIF | 32 | 16 (1) | 4 (3) | 0.008 (12) | ||||||

| 205-2 | Clinical isolate (overexpressing functional MexAB) | 46 | CIP | 4 | >200 | >250 | 50 | 2 (1) | 4 (0) | 1 (2) |

| DOX | 16 | 4 (2) | 8 (1) | 0.5 (5) | ||||||

| CHL | 64 | 32 (1) | 32 (1) | 1 (6) | ||||||

| RIF | 16 | 8 (1) | 16 (0) | 0.125 (16) | ||||||

Values in bold denote a decrease of at least 2 doubling dilutions versus antibiotics alone.

AB, antibiotic; CIP, ciprofloxacin; DOX, doxycycline; CHL, chloramphenicol; RIF, rifampin. MICs were determined in at least two independent experiments.

PAβN was used at 38 μM (20 mg/liter); NV731 and NV716 were used at 10 µM (4 mg/liter).

Cytotoxicity of potentiators and antibiotics.

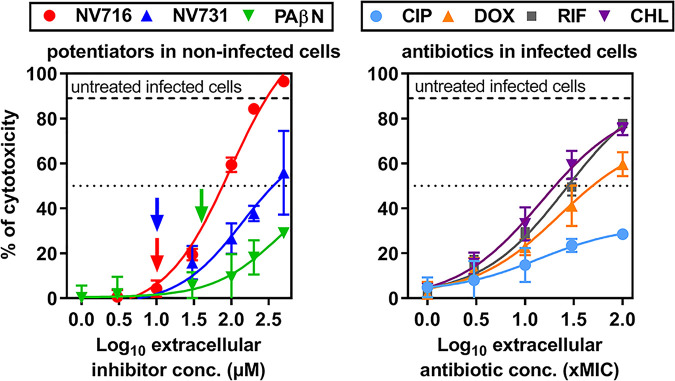

In a first set of experiments, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the EPIs and antibiotics under the conditions of their use for intracellular infection by the trypan blue exclusion test after 24 h of incubation. Infection of THP-1 cells by PAO1 caused 85% cell mortality in the absence of antibiotic. The potentiators alone caused concentration-dependent cell mortality, which was minimal at the concentration used for intracellular infection studies (Fig. 1, left). Doxycycline, chloramphenicol, and rifampin showed toxic effects at high concentrations, with concentrations causing 50% cell mortality (IC50) reaching approximately 30 times their respective MIC in infected cells (Fig. 1, right). Ciprofloxacin was much less toxic at equivalent multiples of its MIC (which corresponds to much lower mass concentrations). IC50 values for toxicity of potentiators, antibiotics, or their combinations in noninfected and infected cells are detailed in Fig. S2 and Table S2 but do not differ from what is described in Fig. 1.

FIG 1.

Cytotoxicity of EPIs and antibiotics as determined by trypan blue exclusion test. (Left) Cytotoxicity of potentiators in noninfected THP-1 cells incubated with increasing concentrations of NV716, NV731, or PAβN over 24 h. (Right) Cytotoxicity of antibiotics in THP-1 cells infected by PAO1 and incubated with increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin (CIP), doxycycline (DOX), rifampin (RIF), or chloramphenicol (CHL) over 24 h. Antibiotic concentrations are expressed in multiples of their MIC against PAO1 (log10 scale). The thick horizontal dotted lines show the percentage of cell mortality measured in untreated infected cells. The thin dotted lines show a 50% cell mortality threshold, allowing us to estimate IC50 values for each compound (see Fig. S2 and Table S2 for these values). The vertical arrows in the left panel show the inhibitor concentrations used in intracellular experiments (10 µM for NV716 and 38 µM for PAβN). All data are means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) (triplicates from three independent experiments).

Activity of antibiotics alone or combined with potentiators against intracellular P. aeruginosa in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model.

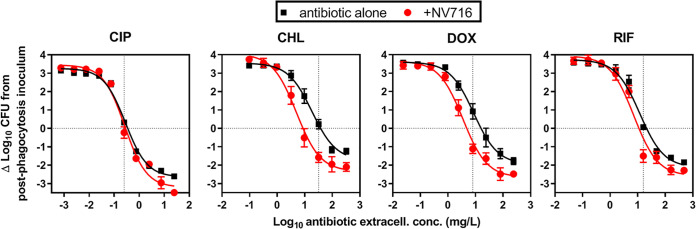

Figure 2 shows the concentration-response curves against intracellular PAO1 in the absence of or in the presence of NV716. The activity of antibiotics alone developed following a sigmoidal concentration-response curve, as previously described (11). At low, sub-MIC concentrations, an ∼3 log10 increase in CFU was noticed over the 24-h incubation period. A static effect was observed at extracellular concentrations close to the MIC of each drug. At the highest concentration tested, the reduction in bacterial counts ranged from a 2 log10 CFU decrease for chloramphenicol, doxycycline, and rifampin, to a 2.6 log10 CFU decrease for ciprofloxacin. In the presence of NV716 at 10 µM, all curves (except that of ciprofloxacin) were shifted to the left, meaning that the corresponding antibiotic was more potent, a static effect being reached at lower extracellular concentrations. Furthermore, the maximal reduction in intracellular counts was also increased, indicating that the antibiotics were more effective.

FIG 2.

Concentration-response curves of antibiotics alone or combined with NV716 against intracellular PAO1 in a model of THP-1 monocytes. The graphs show the changes in CFU counts per mg of cell protein from the initial, postphagocytosis inoculum after 24 h of incubation with increasing extracellular concentrations of antibiotics alone (ciprofloxacin [CIP], doxycycline [DOX], chloramphenicol [CHL], or rifampin [RIF]) or combined with a fixed concentration (10 µM; 4 mg/liter) of NV716. The horizontal dotted line highlights a static effect and the vertical dotted line indicates the MIC of each antibiotic. All data are means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments).

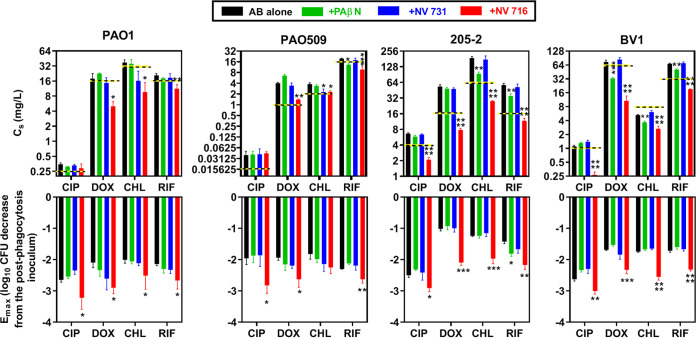

The same type of experiment was performed with the other EPIs and the other strains. Figure 3 illustrates the pharmacodynamic parameters calculated based on the Hill equation of these concentration-response curves (see Materials and Methods for a definition of these parameters), namely, the Cs (a measure of the relative potency of the drug or the drug combination) and the Emax (a measure the relative maximal efficacy of the drug alone or in combination). The Cs values of antibiotics alone were close or slightly higher than the MICs and systematically reduced by 1 doubling dilution or more by NV716, except for ciprofloxacin against PAO1 and PAO509, which were already highly susceptible to this drug. NV731 and PAβN only rarely showed a significant effect on Cs values. Similarly, NV716 was the only EPI capable of increasing the efficacy of the four drugs against all strains, with Emax values being at least 0.5 log10 CFU more negative than those measured for the antibiotics alone.

FIG 3.

Intracellular pharmacodynamic parameters as calculated from the Hill equation of the concentration-response curves. The upper panel shows the Cs (in mg/liter) for the four antibiotics (ciprofloxacin [CIP], doxycycline [DOX], chloramphenicol [CHL], or rifampin [RIF]) against the four strains, with horizontal dotted yellow-black lines corresponding to the MIC of the antibiotic in the absence of potentiator. NV716 and NV731 were used at a concentration of 10 µM and PAβN at a concentration of 38 µM. The lower panel shows the Emax expressed in log10 CFU reduction from the postphagocytosis inoculum. All data are expressed as means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments). Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test versus antibiotic alone (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001).

Concentration-response curves of NV716 combined with fixed concentrations of antibiotics against intracellular P. aeruginosa.

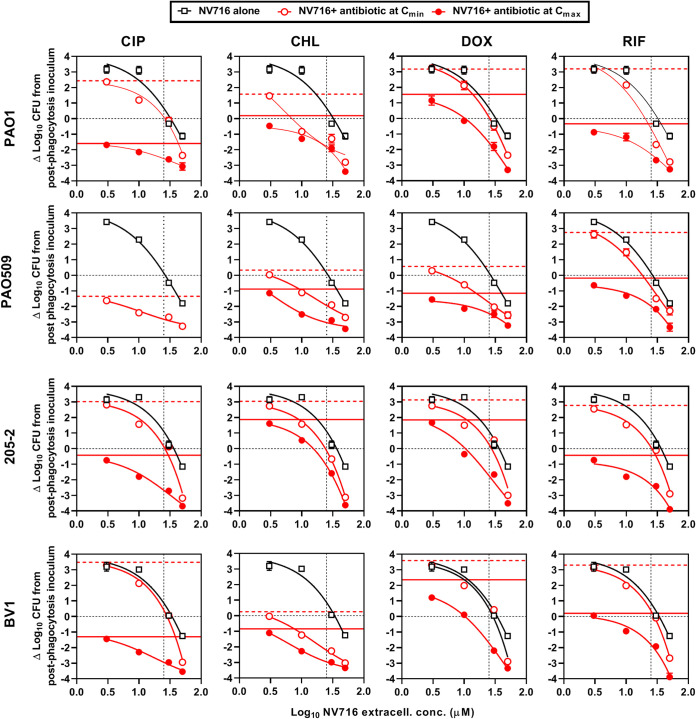

NV716 being the only adjuvant capable of improving both the relative potency and the relative maximal efficacy of antibiotics, we examined the concentration dependency of its effect when combined with antibiotics at fixed concentrations corresponding to their respective minimum and maximum concentrations (Cmin and Cmax) of drug in human serum (see Table S1 for these values). The data are illustrated in Fig. 4. Considering first the activity of NV716 alone, an ∼3 log10 increase in CFU was observed after 24 h of incubation with low NV716 concentrations (≤10 μM) for all strains except PAO509, for which a slight reduction in CFU was already observed at 10 µM. A static effect was obtained for NV716 concentrations close to its MIC in RPMI1640 (25 µM) for all strains. At 50 μM, NV716 caused a reduction in bacterial counts that ranged from an ∼1 log10 CFU decrease for strains PAO1, 205-2, and BV-1 to an ∼2 log10 CFU decrease for PAO509. These data are consistent with those obtained in broth (Fig. S3), showing that NV716 did not prevent PAO1 growth at concentrations ≤10 µM but caused a rapid decrease in bacterial counts at 50 µM. In the presence of antibiotics at their Cmin, we noticed that the intracellular concentration-response curves were globally parallel to those obtained with NV716 alone, thus essentially reflecting the activity of the EPI. Three exceptions, however, need to be highlighted. First, the activity of chloramphenicol was increased for NV716 concentrations of >3 µM against all strains. Second, an improvement in antibiotic activity was noticed against PAO509 as soon as NV716 concentrations reached >3 µM for all drugs that are substrates for efflux (ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and doxycycline). Third, at the highest concentration of NV716 tested (50 µM), the reduction in CFU counts was 0.5 to 1.8 log10 more important than that observed with NV716 alone for all drugs, denoting a synergistic effect. Combining NV716 with antibiotics at their Cmax caused a drastic improvement of activity, with the range of CFU counts being reduced from 0.5 to 2.2 log10 at NV716 concentrations of ≤10 µM to 1.4 to 5.6 log10 at higher NV716 concentrations, in comparison with CFU counts measured for the antibiotic alone.

FIG 4.

Concentration-response curves of NV716 alone or combined with antibiotics at their human Cmin or Cmax against intracellular Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a model of THP-1 monocytes. The graphs show the changes in CFU counts per mg of cell protein from the initial, postphagocytosis inoculum after 24 h of incubation with increasing extracellular concentrations of NV716 alone or combined with ciprofloxacin [CIP], doxycycline [DOX], chloramphenicol [CHL], or rifampin [RIF] at concentrations corresponding to their human Cmin or Cmax (see values in Table S1). The combination with CIP at its Cmax could not be studied, as CFU counts were already close to the limit of detection with the antibiotic alone. The horizontal lines highlight, respectively, a static effect (black dotted line), the effect of the antibiotic alone at its Cmin (red dotted line), or at its Cmax (red plain line), while the vertical dotted line indicates the MIC of NV716 in RPMI1640 (25 µM). All data are means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments).

Persister assay.

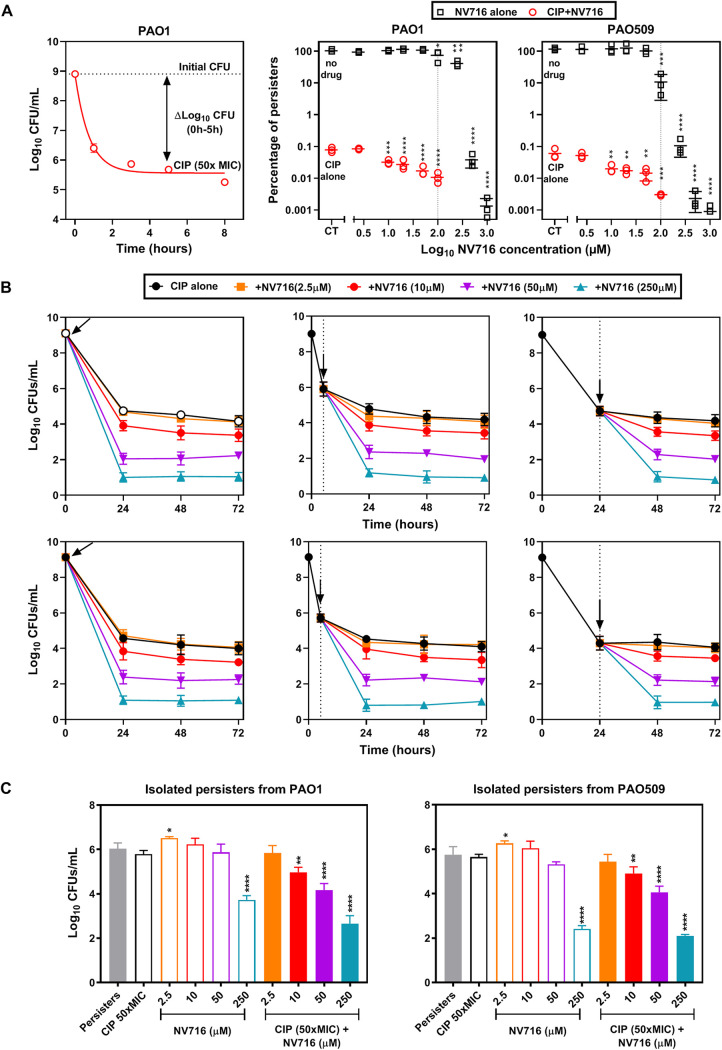

The fact that NV716 increases the intracellular efficacy of antibiotics (i.e., improved killing capacity) suggests it may decrease the proportion of antibiotic persisters in the population, recently identified as a cause of failure to eradicate intracellular S. aureus with antibiotics (30). We therefore examined the persister fraction surviving against ciprofloxacin (selected as a highly bactericidal antibiotic) alone or combined with NV716 in stationary-phase cultures. As shown in the left panel of Fig. 5A, ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC caused a rapid drop in CFU counts of PAO1 over the first 2 h of incubation, after which no further change was observed, leaving a persisting fraction of 0.05% of the initial inoculum. The same type of experiment was then performed with PAO1 and PAO509 exposed to NV716 at increasing concentrations and used alone or combined with 50× MIC of ciprofloxacin. The right panels of Fig. 5A show the proportion of persisters after 5 h of incubation, expressed in percentage of the CFU counts measured in the absence of drugs. NV716 alone had no effect on persisters for concentrations of ≤100 µM but caused a marked reduction in bacterial counts at higher concentrations (3 to 5 log10 CFU for concentrations of >300 µM for PAO1 and >100 µM for PAO509). Strikingly, NV716 at lower concentrations (10 to 100 µM) was already capable of reducing up to 11-fold (PAO1) to 28-fold (PAO509) the percentage of persisters selected by ciprofloxacin.

FIG 5.

Influence of NV716 on persisters selected by ciprofloxacin. (A) Persister fraction assay for ciprofloxacin (CIP) alone, NV716 alone, or their combination against reference strains. Left: kill curve of a stationary-phase culture of PAO1 exposed to ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC over time. The persister fraction is calculated as the difference in CFU counts between control and treated samples at 5 h, when a plateau value has been reached. Right: percentage of persister cells (compared to the CFU counts of untreated samples) after 5 h of incubation with increasing concentrations of NV716 alone or combined with 50× MIC of ciprofloxacin. All data are expressed as means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments). Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test comparing samples exposed to a given concentration of NV716 with the corresponding control (no drug or ciprofloxacin alone): *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001. (B) Kinetics of killing of stationary-phase cultures of PAO1 (top) or PAO509 (bottom) by ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC alone or combined with NV716 at different concentrations. NV716 was added at different timings (0 h [left], 5 h [middle] or 24 h [right]), highlighted by the vertical dotted line and the arrow. All data are expressed as means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments). (C) Killing of persister cells of PAO1 (left) or PAO509 (right) by ciprofloxacin, NV716, or their combinations. Persister cells were isolated after 5 h of incubation with ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC (persisters) and then incubated with either ciprofloxacin (CIP), NV716 at different concentrations, or their combination. All data are expressed as means ± SEM (triplicates from three experiments). Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test comparing samples exposed to CIP alone: *, P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001.

To investigate whether NV716 needs to be administered simultaneously with ciprofloxacin to obtain a maximal activity, we repeated killing experiments with stationary-phase cultures exposed to 50× MIC of ciprofloxacin alone or combined with NV716 added at different time points (Fig. 5B) (31). CFU were significantly reduced after the addition of NV716 at any time point, for concentrations ≥10 µM in both PAO1 and PAO509, indicating that NV716 does not need to be added at the same time as the drug to be able to increase its activity. In a next step, we aimed at examining whether NV716 action was related to a direct capacity to kill persisters or rather to resensitize them to the killing effect of ciprofloxacin. To this end, we isolated the persisters surviving after 5 h of incubation with ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC and reexposed them to ciprofloxacin at 50× MIC, NV716 at different concentrations, or a combination thereof (Fig. 5C) (31). As expected, incubation of the isolated persisters with ciprofloxacin alone caused only a marginal decrease in CFU for both strains, confirming the effective isolation of persister cells. When used alone, NV716 caused a significant decrease in CFU only at the highest concentration tested (250 μM). In contrast, a significant reduction in CFU was observed when NV716 was combined at 10 µM with ciprofloxacin for both strains.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that, in contrast with PAβN and NV731 that act only as efflux inhibitors against planktonic bacteria, NV716 is capable of resensitizing P. aeruginosa to antibiotics whether affected (doxycycline, chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin) or not (rifampin) by efflux, not only in broth but also intracellularly.

Considering first the susceptibility data in broth, we observed a remarkable effect of NV716 on the antibiotic intrinsic activity. While PAβN and NV731 moderately reduced the MICs of antibiotics (essentially those that are substrates for efflux), NV716 caused a marked decrease in the MICs of all drugs, including rifampin (not affected by efflux; see Table S1), against all strains, including the PAO509 strain that does not express efflux pumps and the BV1 strain that expresses a nonfunctional MexAB-OprM efflux pump. This suggests that the mode of action of NV716 is not related to the inhibition of efflux only but probably also relies on its capacity to permeabilize the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa (27). Of note, the synergy with antibiotics is obtained at subinhibitory concentrations of NV716, indicating that, if a direct effect on bacteria takes place, it is not sufficient to cause bacterial death. PAβN has also been shown to permeabilize the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria by displacing Mg2+ and Ca2+ (32), but at concentrations higher than the one we used here, established as adequate to inhibit efflux in initial studies with this molecule (21). The activity of NV716 and of the two other EPIs is observed at concentrations that do not cause cytotoxicity for eukaryotic cells, confirming previous data obtained using another cell type (33), and suggesting no or minimal interaction with eukaryotic membranes.

This contrasts with the cytotoxicity noticed for the three old and disused antibiotics, which caused significant loss of viability of THP-1 monocytes at the highest concentrations tested here, which are largely above those measured in the plasma of treated patients, owing to the high MIC of these drugs against P. aeruginosa. We thus had to limit the range of antibiotic concentrations tested in our concentration-response curves against intracellular bacteria in order to avoid an overly large loss of cells.

Considering the intracellular activity data, we noticed that all antibiotics displayed a bacteriostatic activity at concentrations close or slightly higher than their MIC (Cs being considered a measure of the intracellular MIC), despite the fact they all accumulate to some extent in eukaryotic cells (34) (Table S1). This is in line with our previous observations with other antibiotics in the same model (11), as well as in similar models of intracellular infections by other bacterial species (35, 36), and was interpreted as denoting a poor intracellular bioavailability. While PAβN and NV731 did not increase this relative potency (minimal modification in Cs), NV716 caused a shift of the concentration-response curves to lower concentrations, with a commensurate reduction in the Cs, except for ciprofloxacin against PAO1 and PAO509, the MIC of which was already rather low. Thus, NV716 can decrease the MIC of antibiotics not only extracellularly, but also intracellularly. We did not measure the cellular concentration of NV716 in these cells, but the activity data suggest it has access to intracellular bacteria in sufficient concentrations to exert its synergistic effect. The absence of gain in relative potency observed with PAβN and NV731 can be attributed to their lower intrinsic effects on MICs (as observed in broth) or possibly to a lower penetration inside the cells, which has not been investigated.

Turning our attention toward the intracellular maximal efficacy, we then observed, for antibiotics used alone, reductions of 2.0 to 2.5 log10 CFU with ciprofloxacin, in accordance with our previous results (11), and of 1 to 2 log10 CFU for the other antibiotics, the lowest effect being observed for chloramphenicol and doxycycline against strain 205-2, indicating individual differences in responsiveness among strains. In a broader context, the extent of intracellular killing may also differ depending on the bacterial species. An intracellular Emax of −1.8 log10 CFU was noticed for rifampin against a small colony variant of S. aureus (37), but the activity of chloramphenicol and doxycycline has not been investigated in this model. Chloramphenicol demonstrated bacteriostatic activity against intracellular Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium at 10× MIC (38), while doxycycline reduced by 1.5 log10 the intracellular CFU of Francisella tularensis after 24 h of incubation at a concentration close to its MIC (39). For fluoroquinolones, a maximal reduction of 2 to 4 log10 CFU was observed in concentration-response experiments, similar to those performed here, against S. aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Legionella pneumophila, Burkholderia thailandensis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, or Francisella philomiragia (35, 36, 40).

While PAβN and NV731 did not affect the efficacy of any antibiotic against any of the strains, NV716 systematically improved it (i.e., more negative Emax), suggesting an effect on bacterial responsiveness to antibiotics. We can most likely preclude interference related to the release of bacteria out of the cells before lysis or to the remaining amount of antibiotics accumulated in cells if considering that (i) NV716 did not increase the cytotoxicity of antibiotics, and (ii) charcoal was added to culture plates to adsorb residual antibiotic. Thus, the gain in intracellular efficacy observed in the presence of NV716 is rather suggestive of improved bacterial responsiveness to the drugs. We previously showed an increase in the intracellular efficacy of fluoroquinolones against an insertion mutant in a putative deacetylase in PAO1, which showed a lower persister character in planktonic cultures (18). Here, we found that NV716 was capable of decreasing the proportion of persisters selected by ciprofloxacin in a stationary-phase culture at concentrations for which it did not cause any bacterial killing by itself, and also of reducing at sub-MIC concentrations the number of persisters when combined with ciprofloxacin but not when used alone, suggesting a mode of action unrelated to a direct bactericidal effect but rather related to a resensitization of persisters to the antibiotic (31). Of interest, other molecules capable of disrupting membrane integrity also reduced the residual fraction of persisters upon exposure to antibiotics for different bacterial species (41–43). One of them (SPI009; 1-[[2,4-dichlorophenethyl] amino]-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol) was also shown to increase the efficacy of ciprofloxacin against intracellular P. aeruginosa (44).

This work suffers from some limitations. First, we used a single phagocytic cell line (THP-1 monocytes), which does not necessarily represent the repertoire of cells infected by P. aeruginosa in vivo. The reason for selecting this permissive cell line was that it allows assessing the effect of antibiotics without interference of cell defense mechanisms. Second, we did not measure the cellular accumulation of antibiotics and EPIs in our experimental conditions, but setting up the necessary methodologies would represent a work by itself. Third, we did not study in detail the occurrence of intracellular persisters, the aim of the study being instead oriented toward an in-depth pharmacodynamic evaluation of the possible ability of EPIs to restore the activity of old and disused antibiotics against intracellular P. aeruginosa.

If we thus examine our data in a more clinically oriented perspective, we see that NV716 is capable of improving the activity of all antibiotics in the range of concentrations achieved in the serum of patients as soon as its extracellular concentration exceeds 3 µM. At 10-fold higher concentrations, NV716 caused a 2 to 3 log10 CFU decrease when combined with antibiotics at their human Cmax, strongly arguing for examining the possible efficacy of this compound in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture media.

Table 1 shows the reference and clinical strains used in the study. BV-1 was isolated in 2006 at the Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom, from a patient with cystic fibrosis. It shows a truncation in MexB (672 amino acids instead of 1,046) that drastically reduces the activity of the efflux transporter and has an impact on the MIC of the preferential MexAB-OprM antibiotic substrate temocillin (45). Strain 205 was isolated in 2012 at the University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany, from a patient with cystic fibrosis (46) and shows a fully active MexAB-OprM efflux pump, based on the elevated MIC of temocillin.

Bacteria were incubated overnight at 37°C in tryptic soy agar (TSA) (VWR; Radnor, PA). A single colony was then added to 10 ml of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CA-MHB) (BD Life Sciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and incubated at 37°C overnight under gentle agitation (130 rpm). TSA supplemented with 2 g/liter charcoal (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used for CFU counts. Cell culture medium (RPMI1640) and human and fetal bovine sera were from Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Antibiotics and potentiators.

Chloramphenicol (potency, 98%), doxycycline (potency, 98%), and rifampin (potency, 98%) were obtained as microbiological standards from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), ciprofloxacin HCl (potency, 89%) from Bayer (Leverkusen, Germany), and gentamicin sulfate (potency, 60.7%) from PnReac AppliChem (Darmstadt, Germany). Table S1 shows relevant properties of the antibiotics used in this study. The reference efflux pump inhibitor Phe-Arg β-naphthylamide (PAβN; potency, 98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The hydrosoluble hydrochloride polyamino-isoprenic salt derivatives NV716 and NV731 were synthesized at Aix-Marseille University (26). Stock solutions of these potentiators were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations of 96 mM (50 mg/ml) for PAβN or in water at 10 mM (4 mg/liter) for NV716 and NV731, respectively, and stored at −20°C until use.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs of antibiotics against P. aeruginosa were measured by serial 2-fold microdilution in MHB-CA according to CLSI guidelines in control conditions or in the presence of 38 µM (20 mg/liter) (21) PAβN or of 10 µM (4 mg/liter) NV731 or NV716 (27).

Cytotoxicity assessment (trypan blue exclusion assay).

THP-1 cells (7.5 × 105 cells per ml) were incubated for 24 h in 96-well plates with the antibiotics or potentiators under study over a wide range of concentrations. At the end of the incubation, viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion test (vital colorant excluded from viable cells) using a previously described method (29), with specific adaptations to the purpose of our study. Briefly, 50 μl of trypan blue reagent was added to 50 μl of cell suspension. After 10 min of incubation at 37°C, noncolored (viable) cells were counted using a Fuchs-Rosenthal counting chamber (Tiefe 0.2 mm). Cells were counted in the same surface for all conditions (1 big square made of 16 single squares) (0.0625 mm2 for each single square). The percentage of cytotoxicity was evaluated based on the reduction in the number of living cells according to the following equation:

| (1) |

Intracellular infection.

All experiments were performed using human THP-1 monocytes cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) based on a previously established protocol (11). In brief, bacteria were opsonized by incubation during 1 h in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% human serum at 37°C with gentle agitation (130 rpm). Phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria was then allowed for 2 h using a bacterium:cell ratio of 10:1, after which nonphagocytosed bacteria were eliminated by incubation for 1 h with gentamicin at 50× MIC. After 3 washings with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), infected cells were resuspended in the original volume of RPMI1640 with 10% FBS. The postphagocytosis inoculum was consistently 5 × 105 to 7 × 105 CFU/mg of cell protein (defined as time zero). Infected cells were then incubated for 24 h with antibiotics over a broad range of concentrations (0.003 to 100× their MIC) in 12-well plates. After 24 h of incubation, infected cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed once with PBS at room temperature to eliminate extracellular bacteria, and collected in 1 ml distilled water to achieve complete cell lysis. Lysates were used for determining CFU counts by spreading on agar supplemented with 2 g/liter charcoal (to avoid carry-over effect, especially in samples that had been incubated with high antibiotic concentrations [no difference in colony counts was observed between plates supplemented or not with charcoal for samples exposed to low antibiotic concentrations, ruling out any interfering effect of charcoal in the assay]) and protein content using a commercially available kit (Bio-Rad DC protein assay, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The activity was expressed as the change in CFU (normalized by mg of cell protein) from the initial inoculum after 24 h of incubation. The data were used to fit a sigmoidal function and calculate pharmacodynamic parameters based on the corresponding Hill-Langmuir equation (apparent static concentrations [Cs], i.e., extracellular concentration resulting in no apparent intracellular growth, and maximal relative efficacy [Emax], i.e., maximal decrease in bacterial counts compared to the postphagocytosis inoculum as extrapolated for an infinitely large antibiotic concentration).

Persister assay and isolation.

A single colony from overnight cultures of PAO1 and PAO509 on TSA was added to 200 ml MHB-CA in a 1-liter flask and incubated for 24 h under agitation (130 rpm) at 37°C. An aliquot (10 ml) of the bacterial suspension was then incubated with 50× MIC ciprofloxacin for 5 h at 37°C under agitation (130 rpm), in the presence or absence of NV716. Aliquots were serially diluted in PBS and spread on TSA supplemented with 2 g/liter charcoal for CFU counting. The persister fraction was defined as the number of CFU growing at the end of this experiment compared to the initial inoculum (47). For experiments using isolated persisters, stationary-phase cultures were incubated with ciprofloxacin (50× MIC) over 5 h, i.e., the condition for which a plateau of killing was reached. The remaining bacteria were washed twice with sterile PBS, centrifuged (5,200 × g, 15 min, 4°C), and used for killing assays (31).

Curve fittings and statistical analyses.

Curve fittings were performed with GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.3) software for Windows (GraphPad Prism Software, San Diego, CA). Pharmacodynamic parameters were calculated based on Hill equations of concentration-response curves, and statistical analyses were executed with GraphPadInStat 3 version 3.10 (GraphPad Prism Software) or GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to V. Mohymont, K. Santos-Saial, and V. Yfantis for proficient technical assistance.

G.W. received a PhD grant from the China Scholarship Council (CSC). F.V.B. is Research Director at the Belgian Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS).

This work was supported by the Belgian FRS-FNRS (grant T.0189.16). We thank Campus France and Wallonie Bruxelles International (WBI) for financing a PHC Tournesol program (France-Belgium 2018–2019).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rice LB. 2008. Federal funding for the study of antimicrobial resistance in nosocomial pathogens: no ESKAPE. J Infect Dis 197:1079–1081. doi: 10.1086/533452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrivastava S, Shrivastava P, Ramasamy J. 2018. World health organization releases global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. J Med Soc 32:76–77. doi: 10.4103/jms.jms_25_17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesaros N, Nordmann P, Plesiat P, Roussel-Delvallez M, Van Eldere J, Glupczynski Y, Van Laethem Y, Jacobs F, Lebecque P, Malfroot A, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin Microbiol Infect 13:560–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poole K. 2001. Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 3:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olson MW, Ruzin A, Feyfant E, Rush TS, III, O'Connell J, Bradford PA. 2006. Functional, biophysical, and structural bases for antibacterial activity of tigecycline. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2156–2166. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01499-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez D. 1964. Uptake and binding of chloramphenicol by sensitive and resistant organisms. Nature 203:257–258. doi: 10.1038/203257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleiszig SM, Zaidi TS, Fletcher EL, Preston MJ, Pier GB. 1994. Pseudomonas aeruginosa invades corneal epithelial cells during experimental infection. Infect Immun 62:3485–3493. doi: 10.1128/IAI.62.8.3485-3493.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emam A, Carter WG, Lingwood C. 2010. Glycolipid-dependent, protease sensitive internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa into cultured human respiratory epithelial cells. Open Microbiol J 4:106–115. doi: 10.2174/1874285801004010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Porto P, Cifani N, Guarnieri S, Di Domenico EG, Mariggio MA, Spadaro F, Guglietta S, Anile M, Venuta F, Quattrucci S, Ascenzioni F. 2011. Dysfunctional CFTR alters the bactericidal activity of human macrophages against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 6:e19970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garai P, Berry L, Moussouni M, Bleves S, Blanc-Potard AB. 2019. Killing from the inside: intracellular role of T3SS in the fate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within macrophages revealed by mgtC and oprF mutants. PLoS Pathog 15:e1007812. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buyck JM, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2013. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of the intracellular activity of antibiotics towards Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in a model of THP-1 human monocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2310–2318. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02609-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmiedl A, Kerber-Momot T, Munder A, Pabst R, Tschernig T. 2010. Bacterial distribution in lung parenchyma early after pulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Tissue Res 342:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaas DW, Swan ZD, Brown BJ, Li G, Randell SH, Degan S, Sunday ME, Wright JR, Abraham SN. 2009. Counteracting signaling activities in lipid rafts associated with the invasion of lung epithelial cells by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 284:9955–9964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808629200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carryn S, Chanteux H, Seral C, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM. 2003. Intracellular pharmacodynamics of antibiotics. Infect Dis Clin North Am 17:615–634. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Bambeke F, Barcia-Macay M, Lemaire S, Tulkens PM. 2006. Cellular pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antibiotics: current views and perspectives. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel 9:218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balaban NQ, Helaine S, Lewis K, Ackermann M, Aldridge B, Andersson DI, Brynildsen MP, Bumann D, Camilli A, Collins JJ, Dehio C, Fortune S, Ghigo JM, Hardt WD, Harms A, Heinemann M, Hung DT, Jenal U, Levin BR, Michiels J, Storz G, Tan MW, Tenson T, Van Melderen L, Zinkernagel A. 2019. Definitions and guidelines for research on antibiotic persistence. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:441–448. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peyrusson F, Varet H, Nguyen TK, Legendre R, Sismeiro O, Coppée J-Y, Wolz C, Tenson T, Van Bambeke F. 2020. Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus persisters upon antibiotic exposure. Nat Commun 11:2200. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandekar S, Liebens V, Fauvart M, Tulkens PM, Michiels J, Van Bambeke F. 2018. The putative de-N-acetylaseDnpA contributes to intracellular and biofilm-associated persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exposed to fluoroquinolones. Front Microbiol 9:1455. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burrows LL. 2018. The therapeutic pipeline for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. ACS Infect Dis 4:1041–1047. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theuretzbacher U, Van Bambeke F, Canton R, Giske CG, Mouton JW, Nation RL, Paul M, Turnidge JD, Kahlmeter G. 2015. Reviving old antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2177–2181. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomovskaya O, Warren MS, Lee A, Galazzo J, Fronko R, Lee M, Blais J, Cho D, Chamberland S, Renau T, Leger R, Hecker S, Watkins W, Hoshino K, Ishida H, Lee VJ. 2001. Identification and characterization of inhibitors of multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel agents for combination therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:105–116. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.105-116.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pages JM, Masi M, Barbe J. 2005. Inhibitors of efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Mol Med 11:382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomovskaya O, Bostian KA. 2006. Practical applications and feasibility of efflux pump inhibitors in the clinic—a vision for applied use. BiochemPharmacol 71:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahamoud A, Chevalier J, Alibert-Franco S, Kern WV, Pages JM. 2007. Antibiotic efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria: the inhibitor response strategy. J Antimicrob Chemother 59:1223–1229. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douafer H, Andrieu V, Phanstiel O, Brunel JM. 2019. Antibiotic adjuvants: make antibiotics great again! J Med Chem 62:8665–8681. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunel JM, Lieutaud A, Lome V, Pages JM, Bolla JM. 2013. Polyaminogeranic derivatives as new chemosensitizers to combat antibiotic resistant gram-negative bacteria. Bioorg Med Chem 21:1174–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borselli D, Lieutaud A, Thefenne H, Garnotel E, Pages JM, Brunel JM, Bolla JM. 2016. Polyamino-isoprenic derivatives block intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to doxycycline and chloramphenicol in vitro. PLoS One 11:e0154490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borselli D, Brunel JM, Gorge O, Bolla JM. 2019. Polyamino-isoprenyl derivatives as antibiotic adjuvants and motility inhibitors for Bordetella bronchiseptica porcine pulmonary infection treatment. Front Microbiol 10:1771. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buyck JM, Lemaire S, Seral C, Anantharajah A, Peyrusson F, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2016. In vitro models for the study of the intracellular activity of antibiotics. Methods Mol Biol 1333:147–157. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2854-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen TK, Peyrusson F, Dodémont M, Pham NH, Nguyen NH, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2020. The persister character of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus contributes to faster evolution to resistance and higher survival in THP-1 monocytes: a study with moxifloxacin. Front Microbiol doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.587364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebens V, Defraine V, Knapen W, Swings T, Beullens S, Corbau R, Marchand A, Chaltin P, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2017. Identification of 1-((2,4-dichlorophenethyl)amino)-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol, a novel antibacterial compound active against persisters of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00836-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00836-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamers RP, Cavallari JF, Burrows LL. 2013. The efflux inhibitor phenylalanine-arginine beta-naphthylamide (PAbetaN) permeabilizes the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One 8:e60666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lieutaud A, Pieri C, Bolla JM, Brunel JM. 2020. New polyaminoisoprenyl antibiotics enhancers against two multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from Enterobacter and Salmonella species. J Med Chem 63:10496–10508. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulkens PM. 1991. Intracellular distribution and activity of antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 10:100–106. doi: 10.1007/BF01964420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barcia-Macay M, Seral C, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2006. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of the intracellular activities of antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus in a model of THP-1 macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:841–851. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.3.841-851.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaire S, Van Bambeke F, Tulkens PM. 2011. Activity of finafloxacin, a novel fluoroquinolone with increased activity at acid pH, towards extracellular and intracellular Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and Legionella pneumophila. Int J Antimicrob Agents 38:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen HA, Denis O, Vergison A, Theunis A, Tulkens PM, Struelens MJ, Van Bambeke F. 2009. Intracellular activity of antibiotics in a model of human THP-1 macrophages infected by a Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variant strain isolated from a cystic fibrosis patient: pharmacodynamic evaluation and comparison with isogenic normal-phenotype and revertant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:1434–1442. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01145-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiu CH, Lin TY, Ou JT. 1999. In vitro evaluation of intracellular activity of antibiotics against non-typhoid Salmonella. Int J Antimicrob Agents 12:47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(99)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maurin M, Mersali NF, Raoult D. 2000. Bactericidal activities of antibiotics against intracellular Francisella tularensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:3428–3431. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3428-3431.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chalhoub H, Harding SV, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2019. Influence of pH on the activity of finafloxacin against extracellular and intracellular Burkholderia thailandensis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Francisella philomiragia and on its cellular pharmacokinetics in THP-1 monocytes. Clin Microbiol Infect doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Defraine V, Liebens V, Loos E, Swings T, Weytjens B, Fierro C, Marchal K, Sharkey L, O'Neill AJ, Corbau R, Marchand A, Chaltin P, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2018. 1-((2,4-dichlorophenethyl)amino)-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol kills Pseudomonas aeruginosa through extensive membrane damage. Front Microbiol 9:129. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicol M, Mlouka MAB, Berthe T, Di Martino P, Jouenne T, Brunel JM, De E. 2019. Anti-persister activity of squalamine against Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents 53:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naclerio GA, Sintim HO. 2020. Multiple ways to kill bacteria via inhibiting novel cell wall or membrane targets. Future Med Chem 12:1253–1279. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2020-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Defraine V, Verstraete L, Van Bambeke F, Anantharajah A, Townsend EM, Ramage G, Corbau R, Marchand A, Chaltin P, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2017. Antibacterial activity of 1-[(2,4-dichlorophenethyl)amino]-3-phenoxypropan-2-ol against antibiotic-resistant strains of diverse bacterial pathogens, biofilms and in pre-clinical infection models. Front Microbiol 8:2585. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chalhoub H, Pletzer D, Weingart H, Braun Y, Tunney MM, Elborn JS, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Plésiat P, Kahl BC, Denis O, Winterhalter M, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2017. Mechanisms of intrinsic resistance and acquired susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients to temocillin, a revived antibiotic. Sci Rep 7:40208. doi: 10.1038/srep40208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mustafa M-H, Chalhoub H, Denis O, Deplano A, Vergison A, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Tunney MM, Elborn JS, Kahl BC, Traore H, Vanderbist F, Tulkens PM, Van Bambeke F. 2016. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients in Northern Europe. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:6735–6741. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01046-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Groote VN, Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, Kint CI, Verbeeck AM, Beullens S, Cornelis P, Michiels J. 2009. Novel persistence genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified by high-throughput screening. FEMS Microbiol Lett 297:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mima T, Joshi S, Gomez-Escalada M, Schweizer HP. 2007. Identification and characterization of TriABC-OpmH, a triclosan efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requiring two membrane fusion proteins. J Bacteriol 189:7600–7609. doi: 10.1128/JB.00850-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.