Abstract

Background

Treatment and diagnostic recommendations are often made in clinical guidelines, reports from advisory committee meetings, opinion pieces such as editorials, and narrative reviews. Quite often, the authors or members of advisory committees have industry ties or particular specialty interests which may impact on which interventions are recommended. Similarly, clinical guidelines and narrative reviews may be funded by industry sources resulting in conflicts of interest.

Objectives

To investigate to what degree financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest are associated with favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews.

Search methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Methodology Register for studies published up to February 2020. We also searched reference lists of included studies, Web of Science for studies citing the included studies, and grey literature sources.

Selection criteria

We included studies comparing the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations of drugs or devices (e.g. recommending a particular drug) in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, or narrative reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently included studies, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. When a meta‐analysis was considered meaningful to synthesise our findings, we used random‐effects models to estimate risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with RR > 1 indicating that documents (e.g. clinical guidelines) with conflicts of interest more often had favourable recommendations. We analysed associations for financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest separately, and analysed the four types of documents both separately (pre‐planned analyses) and combined (post hoc analysis).

Main results

We included 21 studies analysing 106 clinical guidelines, 1809 advisory committee reports, 340 opinion pieces, and 497 narrative reviews. We received unpublished data from 11 studies; eight full data sets and three summary data sets. Fifteen studies had a risk of confounding, as they compared documents that may differ in other aspects than conflicts of interest (e.g. documents on different drugs used for different populations). The associations between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations were: clinical guidelines, RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.93 to 1.69 (four studies of 86 clinical guidelines); advisory committee reports, RR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.45 (four studies of 629 advisory committee reports); opinion pieces, RR: 2.62, 95% CI: 0.91 to 7.55 (four studies of 284 opinion pieces); and narrative reviews, RR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.49 (four studies of 457 narrative reviews). An analysis combining all four document types supported these findings (RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.44).

One study investigating specialty interests found that the association between including radiologist guideline authors and recommending routine breast cancer screening was RR: 2.10, 95% CI: 0.92 to 4.77 (12 clinical guidelines).

Authors' conclusions

We interpret our findings to indicate that financial conflicts of interest are associated with favourable recommendations of drugs and devices in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. However, we also stress risk of confounding in the included studies and the statistical imprecision of individual analyses of each document type. It is not certain whether non‐financial conflicts of interest impact on recommendations.

Plain language summary

Conflicts of interest and recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews

Which treatments and diagnostic tests doctors offer to their patients are often based on recommendations expressed in a variety of documents. A common example is clinical guidelines, which are statements providing recommendations on how to diagnose and treat patients on the basis of the best available evidence. The treatments that may be offered to patients are also influenced by which drugs are recommended for approval by drug advisory committees at regulatory drug agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Finally, doctors may also be influenced by recommendations expressed in opinion pieces, such as editorials, or in narrative review papers in medical journals.

Quite often, publications expressing clinical recommendations are written by authors with conflicts of interest related to a specific product, for example when the author acts as a consultant for the company producing the treatment of interest. Such conflicts of interest may impact on the recommendations made. Similarly, authors may have so‐called non‐financial conflicts of interest such as belonging to a specific profession, for example being an orthopaedic surgeon, which may influence whether a specific intervention is preferred over another. This Cochrane Methodology Review investigated how financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest are associated with the recommendations made in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews.

We included 21 studies and we interpreted our findings to indicate that financial conflicts of interest are associated with favourable recommendations in these documents, although there is some uncertainty around the size of the effect. This means that when such publications are written by authors with financial conflicts of interest, they more often have favourable recommendations than publications written by authors without conflicts of interest. Only a single study investigated the impact of non‐financial conflicts of interest in clinical guidelines and the results were uncertain, but indicated a similar direction of effect.

We suggest that patients, doctors, and healthcare decision makers primarily use clinical guidelines, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews that have been written by authors without financial conflicts of interest. If that is not possible, users should read and interpret the publications with caution. Furthermore, our findings suggest that if committee members are asked to vote on the recommendation of a drug, they may be more likely to vote in favour of the drug when they have financial conflicts of interest.

Background

Recommendations of treatment and diagnostic approaches impact on patient care, especially if they are written by “key opinion leaders” or originate from healthcare authorities. Recommendations may appear in multiple types of documents, for example in clinical guidelines and advisory committee reports (which could include records from meetings in regulatory drug advisory committees or hospital drug and therapeutics committees) as well as in opinion pieces such as editorials, and in narrative reviews.

Quite often, publications with clinical recommendations are written by authors with conflicts of interest related to the drug or device industry. For example, in a sample of 45 clinical guidelines written by 254 authors, Bindslev and colleagues found that 135 (53%) authors had financial conflicts of interest (Bindslev 2013). Similarly, studies report that narrative reviews, editorials and commentaries often (31%) had at least one author with conflicts of interest (Grundy 2018), and around a quarter of committee meetings at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) included at least one voting member with financial conflicts of interest (Xu 2017).

Authors may also have non‐financial conflicts of interest. For example, if authors of a guideline were also authors of some of the included studies on which recommendations in a guideline were based, the authors may be more likely to favour the interventions that they previously studied (Akl 2014). Whereas financial conflicts of interest are relatively simple to characterise (i.e. any financial relationship with a party with an interest in the direction of a recommendation), it is more unclear and debated which interests and relationships constitute a non‐financial conflict of interest and whether the term is appropriate (Bero 2016). This lack of consensus regarding non‐financial conflicts of interest is also reflected in journal disclosure policies. Shawwa and colleagues found that only 57% of core clinical journals specifically required disclosure of non‐financial conflicts of interest, and that there was large variation in how journals defined such conflicts (Shawwa 2016).

Numerous studies have investigated the impact of financial conflicts of interest on the interpretation of the results of primary research studies, mainly clinical trials. An updated Cochrane Methodology Review reported an association between industry funding and favourable conclusions in primary research studies (Lundh 2017). This association has been attributed to various factors, including the sponsor's influence on framing the question, study design, and reporting of results (Bero 1996; Bero 2007; Fabbri 2018). Similarly, another Cochrane Methodology Review reported an association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable conclusions in systematic reviews (Hansen 2019a). In contrast, few studies have investigated the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines (Norris 2012), advisory committee reports (Pham‐Kanter 2014), opinion pieces (Bariani 2013), and narrative reviews (Dunn 2016). Furthermore, the evidence from such studies has to our knowledge not previously been synthesised in a methodological systematic review. This review fills that gap and is based on the previously published protocol (Hansen 2019b).

How these methods might work

Financial conflicts of interest such as honoraria, consultancies, grants, or advisory board membership can provide a substantial income for physicians and academic researchers. Such relationships may therefore affect how the benefits and harms of the companies' products are perceived by authors and thereby whether they are recommended in publications by the authors. Similarly, non‐financial interests, such as authors’ professional affiliations and personal relationships, may influence the recommendation of a particular intervention.

In contrast to primary research papers and systematic reviews, clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews typically provide specific recommendations concerning treatments and diagnostics. However, the methodological rigour behind such recommendations differs between the types of publications. Clinical guidelines are increasingly based on systematic searches of existing evidence and may follow standardised procedures for grading evidence and recommendations (Guyatt 2011). In contrast, authors of opinion pieces are free to selectively cite studies and interpret the evidence, and editorials often focus on results from a single primary study. Clinical guidelines are also typically written by a broad group of authors who may have differing viewpoints, whereas opinion pieces are often written by single authors. Thus, clinical guidelines may be less susceptible to influence from conflicts of interest compared to opinion pieces. Committee reports and narrative reviews are conducted using more or less systematic procedures, but also involve subjective elements and may therefore be more susceptible to influence from conflicts of interest than clinical guidelines, but less than opinion pieces.

Why it is important to do this review

Recommendations in journal papers or guidelines and decisions about which interventions are approved by regulatory authorities have substantial impact on the interventions offered to patients. It is therefore important that such recommendations are evidence‐based and as little influenced by conflicts of interest as possible. Individual studies have investigated the associations between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews, but these studies differ in methods and conclusions. Despite conflicts of interest being recognised as an important source of influence on clinical recommendations, these studies have, to our knowledge, not previously been summarised in a systematic review. Findings from this review may provide patients, clinicians, and policymakers with guidance on how to interpret recommendations in light of conflicts of interest and may assist journal editors, guideline issuing organisations, and public authorities with managing such conflicts.

Objectives

Our objectives were to investigate to what degree financial and non‐financial conflicts of interests are associated with favourable recommendations in:

clinical guidelines;

advisory committee reports (e.g. records from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee on oncological drugs or hospital drug and therapeutics committees);

opinion pieces (e.g. editorials and commentaries);

narrative reviews.

Terminology

We used the definitions below. All definitions are described in more detail in Appendix 1.

Conflicts of interest: any financial or non‐financial conflicts of interest as specified below.

Financial conflicts of interest: any funding of clinical guidelines, opinion pieces, or narrative reviews by drug or device companies or any authors or committee members with ties to such companies (e.g. advisory board membership).

Non‐financial conflicts of interest: any relationships that differ from what is typically regarded as financial conflicts of interest (i.e. relationships with the drug or device industry). Regardless of the definitions used by the authors of the included studies, we do not focus on studies investigating beliefs (e.g. political or religious), personal experience (e.g. abuse or trauma), or institutional conflicts of interest (Bero 2016).

Drugs: medications that require approval from a regulatory authority.

Devices: instruments used in diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease (FDA 2017). This term also includes medical imaging technologies.

Clinical guidelines: “Systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” (Institute of Medicine 1990).

Advisory committee reports: reports from meetings held in committees, boards, councils, or similar formalised groups that are established to advise an organisation and provide a recommendation concerning an intervention (e.g. the FDA advisory committee on oncological drugs).

Opinion pieces: publications that are not research studies in which an author expresses a personal opinion about a specific intervention (e.g. editorials, commentaries, and letters to the editor).

Narrative reviews: literature reviews without a systematic search of the literature with clear eligibility criteria.

Documents: clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included published and unpublished studies of any design (e.g. cross‐sectional studies) that assessed the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations made in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, or narrative reviews concerning drug or device interventions (which include diagnostic tests for the purposes of this review, see Appendix 1).

Studies in all languages were eligible.

Types of data

We included studies with dichotomous (e.g. favourable or unfavourable recommendations) or continuous data (e.g. percentages) on the association between conflicts of interest and recommendations in favour of the intervention in question.

Types of methods

We included studies that investigated documents with conflicts of interest versus documents without conflicts of interest. For financial conflicts of interest, we included studies regardless of the type of financial conflict. For non‐financial conflicts of interest, we included studies on intellectual, academic, professional, or specialty interests, and personal or professional relationships.

We excluded studies concerning:

financial conflicts of interest not related to the drug or device industry (e.g. tobacco or nutrition industry);

beliefs (e.g. religious) or personal experiences (e.g. suffering from the medical condition), even if the original authors defined these as non‐financial conflicts of interest;

membership of certain groups (e.g. gender or ethnicity), even if the original authors defined this as non‐financial conflicts of interest;

both financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest at the level of an institution;

conflicts of interest related to reports from scientific grant committees.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was the type of recommendation in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. We defined ‘favourable recommendations’ according to the definitions used by the authors of the included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Methodology Register (up to February 2020). We searched Web of Science (up to March 2020) for studies that cited any of the included studies.

Search strategy

Our search strategy was based on search terms used in a PubMed search from two previous Cochrane Methodology Reviews on financial conflicts of interest in primary research studies and systematic reviews (Lundh 2017; Hansen 2019a), and tailored it for this review (Appendix 2). The PubMed strategy was adapted for Embase and The Cochrane Methodology Register. All search strategies were developed in collaboration with information specialists.

Searching other resources

Grey literature

Our electronic search in the Cochrane Methodology Register identified relevant grey literature because the database includes conference abstracts. Additionally, we searched for conference abstracts from Peer Review Congresses (American Medical Association 2017), Cochrane Colloquia (Cochrane Community 2017), and Evidence Live (Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine 2017) (search of all conferences up to February 2020). We searched PROSPERO (up to February 2020) for registered systematic reviews and the ProQuest database (up to February 2020) for dissertations and theses.

Additional searches

We used Google Scholar (up to March 2020) to search for additional eligible studies. We based our search on core search terms from the search strategy defined in Appendix 2 and screened the first 20 records for each search. We searched PubMed for publications by the first and last author of the included studies (up to March 2020). Other sources of data included the files of the authors of this review and checking reference lists of included studies (Horsley 2011).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (CHN) screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved records for obvious exclusions. Two review authors (CHN and either AWJ or AL) independently assessed potentially eligible studies based on full text. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and used arbitration by a third review author (AL or AH) when needed.

Reasons for exclusion of studies are described in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CHN and either AWJ, ML, or AL) independently extracted data from included studies. We resolved any differences in data extraction by discussion and used arbitration by a third review author (AH or AL) when needed.

We extracted data on basic characteristics of the included studies and data on the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations. We extracted data for documents with and without conflicts of interest based on the definitions used by the authors of the included studies. When reported, we also extracted effect measures and confidence intervals (CIs) or the raw data to calculate them. We also extracted information on funding sources and conflicts of interest disclosures of authors of the included studies. The full plan for data extraction is reported in Appendix 3.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

As there are no published assessment tools for investigating bias in these types of studies, we developed our own criteria based on those used in previous Cochrane Methodology Reviews on financial conflicts of interest in primary research studies and systematic reviews (Lundh 2017; Hansen 2019a). In accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020) we use the term ‘risk of bias’ in contrast to ‘methodological quality’. However, we recognise that some of the included items are more related to methodological quality than risk of bias and that inadequate methodological quality (e.g. coding of conflicts of interest information by a single author) is not necessarily biased. In our risk of bias assessment we therefore focused on whether study methodology was appropriate (i.e. appropriate methodology resulted in low risk of bias).

Two review authors (CHN and either AWJ, ML, or AL) independently assessed included studies for risk of bias. We resolved any disagreements by discussion and used arbitration by a third review author (AL or AH) when needed. We used the following criteria.

Whether there was a risk of bias in the inclusion of documents (low risk of bias may, for example, include reporting of clear inclusion criteria with two or more assessors independently selecting documents).

Whether there was a risk of bias in the coding of conflicts of interest (low risk of bias may, for example, include coding done by two or more assessors based on multiple sources of information).

Whether there was a risk of bias in the coding of recommendations (low risk of bias may, for example, include coding done by two or more assessors blinded to the status of conflicts of interest).

Whether there was a risk of confounding (low risk of confounding may, for example, include documents with and without conflicts of interest discussing the same treatment used in similar groups of patients). The documents included in a study may differ on key aspects (e.g. in a sample of clinical guidelines, the guidelines may differ in relation to types of patients and conditions, interventions, the quality of the underlying evidence, and the quality of the guidelines), which could potentially confound the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations.

In assessing risk of bias, our primary aim was to differentiate between studies with higher and lower risk of bias. Thus, we coded, by default, a study as low risk of bias if all criteria were assessed as low risk of bias; otherwise, we coded it as high risk of bias.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of the included studies in an attempt to obtain unpublished data, to clarify issues on our 'Risk of bias' assessments, or to receive copies of unpublished protocols (Appendix 4). When we received unpublished data, we analysed the data according to the methods used in the original studies.

We included one study that investigated a mixture of opinion pieces and narrative reviews, but which did not report results stratified by document type. However, coding of financial conflicts of interest and recommendations were reported separately for each document (Hayes 2019). As the type of document (e.g. opinion piece) was not coded in the original study, two review authors (CHN and AL) independently coded the type of documents to enable inclusion in our meta‐analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was described using the I2 statistic.

To further address statistical heterogeneity, we calculated prediction intervals for our primary analyses. We only calculated prediction intervals when at least four studies were included in the pooled analysis, because intervals will be imprecise when the effect estimates are based on only a few studies. A prediction interval presents the expected range of true effects in similar studies, is not influenced by sample size, and shows whether the study effects are dispersed over a wide range (IntHout 2016). A prediction interval thereby shows the range of risk ratios (RRs) that can be expected from similar studies, and, thus, a broad prediction interval indicates heterogeneity and uncertainty. To calculate prediction intervals, we used the formula presented by Riley and colleagues (Riley 2011) (Appendix 5).

Data synthesis

Data management of individual studies

In our primary analyses, we used the definitions and coding of recommendations and conflicts of interest used by the authors of the included studies. If an ordinal scale was used to grade recommendations (e.g. highly positive, positive, neutral, negative, and highly negative), we recoded recommendations into two categories (i.e. favourable versus neutral/unfavourable recommendations).

If the sample of documents included in a study contained a mixture of types of documents (e.g. both clinical guidelines and research papers), we only included the study in our pooled analyses if we could get separate data for the types of documents relevant for our review.

In our analyses on clinical guidelines, we included one study that investigated 13 guidelines that each included recommendations on 24 different drugs (Norris 2013). To allow for this type of panel data, we used Poisson Generalised Estimating Equations to calculate effect estimates we could include in our pooled analyses (Lumley 2006).

In our analyses on advisory committee reports, we included studies with two types of analysis units: committee members and their individual votes (individual level) and committee reports and the overall voting outcome (meeting level). In our primary analysis, we analysed data on meeting level as this level of analysis was most comparable to recommendations in the other types of documents (e.g. clinical guidelines).

In some cases the same document was included in two separate studies. When we had access to unpublished data it was possible to remove the duplicate documents and we chose to remove it from the study with the latest publication date. We included two studies that investigated some of the same FDA advisory committee reports (Ackerley 2009; Lurie 2006) and removed duplicates from the study by Ackerley and colleagues (Ackerley 2009). We included two studies that investigated editorials published in some of the same oncology journals in overlapping time periods (Bariani 2013; Lerner 2012) and removed duplicates from the study by Bariani and colleagues (Bariani 2013).

Primary analysis

Due to expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity among the included studies, we used inverse variance random‐effects models to estimate RRs with 95% CIs. We compared recommendations between documents with and without conflicts of interest and ensured uniform directionality so RR > 1 indicated that documents with conflicts of interest more often had favourable recommendations than documents without conflicts of interest. We analysed financial and non‐financial conflicts of interests separately, and analysed clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews separately.

Using the methods for calculating a Number Needed to Treat, we calculated a Number Needed to Read for each document type (Appendix 6) (Schünemann 2020). We defined Number Needed to Read as the expected number of documents with conflicts of interest needed to be read rather than documents without conflicts of interest for one additional document having a favourable recommendation. As describing the 95% CI is difficult for Number Needed to Read when the CI of the RR crosses the boundary of no difference (Altman 1998), we report the 95% CI of the Number Needed to Read in Appendix 6.

Secondary analyses

We analysed advisory committee reports on an individual level.

In a post‐hoc analysis, we combined all four types of documents (i.e. clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews) in an analysis of financial conflicts of interest.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct the following pre‐planned subgroup analyses for our primary analyses for all document types (Appendix 7):

Documents stratified by different types of financial conflicts of interest (e.g. funding, investigator, author grants, honorarium, consulting, speaker’s bureau, equity/stock, gifts)

Studies assessed as high risk of bias versus studies assessed as low risk of bias

We planned to conduct the following pre‐planned subgroup analysis for our primary analysis on clinical guidelines only:

Clinical guidelines developed using standardised methods (e.g. GRADE (Guyatt 2011) or USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2015)) versus clinical guidelines not developed using standardised methods. For the stratification of documents, we relied on the coding done by the authors of the included studies

In addition, we conducted the following post‐hoc subgroup analyses for our primary analyses.

Documents stratified by degree of financial conflicts of interest: we compared major financial conflicts of interest (defined as at least half of the authors/committee members having financial conflicts of interest) with minor financial conflicts of interest (defined as less than half of the authors/committee members with financial conflicts of interest). The purpose of this subgroup analysis was to investigate a potential dose‐response relationship between financial conflicts of interest and recommendations.

We only carried out the subgroup analyses when we had sufficient data (i.e. at least five documents in the groups with and without conflicts of interest in the included studies combined).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct the following pre‐planned sensitivity analyses for our primary analyses (Appendix 8).

Excluding documents with unclear or undisclosed conflicts of interest.

Excluding documents with neutral recommendations.

Excluding all studies which disclosed a relevant conflict of interest. For example, if one of the included studies was funded by a drug company, we excluded the study and re‐analysed our data.

Re‐analysing our primary analyses using a fixed‐effect model.

In addition, we conducted the following post‐hoc sensitivity analyses for our primary analyses.

Re‐categorising documents with financial conflicts of interest into documents with financial conflicts of interest related to the manufacturer of the drug or device of interest or to any for‐profit organisation in two separate analyses.

We only carried out the sensitivity analyses when we had sufficient data (i.e. at least five documents in the groups with and without conflicts of interest in the included studies combined).

We conducted all analyses in Review Manager (RevMan 5.4) and Stata 15.

Assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Based on prior experience, using formal systems such as GRADE for assessing the certainty of evidence from methodological studies is challenging. We therefore focused on interpreting our results in the context of the statistical precision of our estimates (i.e. width of CIs) and risk of confounding. In Appendix 9, we report GRADE assessments employing both an approach similar to observational intervention studies and to prognostic studies (Guyatt 2008; Foroutan 2020).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

Results of the search

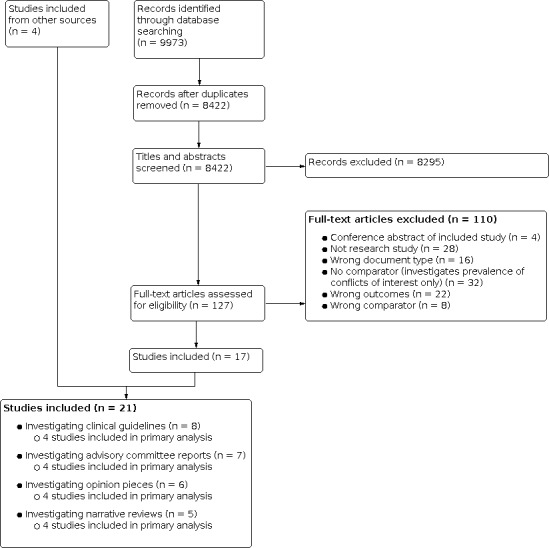

See: Figure 1

1.

Study flow diagram.

In total, 9973 records were identified through our database searches. After removing duplicates, we screened 8422 records based on titles and abstracts and assessed 127 full‐text papers for inclusion. In total, we included 21 studies. We did not identify any unpublished studies or protocols for planned studies.

Included studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

The 21 studies were published between 1998 and 2019. Eight studies investigated clinical guidelines (median number of clinical guidelines: nine, range: 2 to 50), seven studies investigated FDA drug and/or device advisory committee reports (median number of advisory committee reports: 376, range: 79 to 416), six studies investigated opinion pieces (editorials, commentaries, and letters; median number of opinion pieces: 44, range: 8 to 131), and five studies investigated narrative reviews (median number of narrative reviews: 84, range: 7 to 213). Sixteen studies investigated documents on drugs, three studies investigated documents on devices, and two studies investigated documents on both drugs and devices. Twenty studies only investigated financial conflicts of interest and one study investigated both financial conflicts of interest and specialty affiliations among guideline authors (i.e. non‐financial conflicts of interest). None of the included studies reported industry funding, but six studies did not report funding information. Seven of the included studies investigating documents with and without financial conflicts of interest were conducted by authors who themselves had financial conflicts of interest.

We received unpublished data from 11 studies. In eight cases, we obtained full unpublished data sets (Ackerley 2009; Bariani 2013; Dunn 2016; Hartog 2012; Lerner 2012; Lurie 2006; Wang 2010; Zhang 2019), and in three cases we obtained additional summary data (Pham‐Kanter 2014; Tibau 2015; Tibau 2016).

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

We assessed 20 studies as overall high risk of bias and one study as low risk of bias. Around half of the included studies had low risk of bias in the document inclusion process (n = 10) and the majority had low risk of bias in the coding of conflicts of interest (n = 15) and recommendations (n = 17). We assessed six studies to be low risk of confounding and 15 to be high risk of confounding, because they included documents of different topics (e.g. various cancer drugs for different indications), or included documents on the same drug used for different indications (e.g. antidiabetic drugs used in adults, children, or pregnant women).

We found no published protocols and only received unpublished protocols for two studies (Downing 2014; Lurie 2006). We found no discrepancies between outcomes in these protocols and study publications. Nine of 21 author teams replied that no protocol existed for their study, and two author teams supplied us with reports that we did not consider to be protocols (Appendix 4).

Effect of methods

Financial conflicts of interest: differences in recommendations

Clinical guidelines

Eight studies investigated a total of 106 clinical guidelines and data from four of these studies including 86 clinical guidelines could be used in our pooled primary analysis (Aakre 2012; Norris 2013; Tibau 2015; Wang 2010). The association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines was RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.93 to 1.69, I2: 0% (Analysis 1.1). The Number Needed to Read for clinical guidelines was 9.1 (Appendix 6).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Primary analyses, Outcome 1: Financial conflicts of interest

The prediction interval for the RR was 0.65 to 2.43 (Appendix 5). Thus, one can expect that clinical guidelines with financial conflicts of interest more often have favourable recommendations compared with clinical guidelines without financial conflicts of interest, but for an individual study of clinical guidelines the association may be reversed.

Four included studies did not report data in a way that enabled us to include them in our pooled analysis. Two studies each investigated one clinical guideline with financial conflicts of interest and one without. In both of these studies the clinical guidelines with financial conflicts of interest had a favourable recommendation, whereas the clinical guidelines without had a unfavourable recommendation (George 2014; Schott 2013). One study investigated 12 clinical guidelines, but only reported the percentage of authors with financial conflicts of interest in each guideline. Three out of eight clinical guidelines with favourable recommendations included authors with financial conflicts of interest (prevalence from 12% to 53%), and two out of four clinical guidelines with unfavourable recommendations included authors with financial conflicts of interest (prevalence 9% and 11%) (Norris 2012). The remaining study investigated a mixture of four clinical guidelines, 23 editorials and commentaries, and 40 reviews (mainly narrative) commenting on a randomised trial on fenofibrate use. The authors found that documents written by authors with conflicts of interest more often recommended fibrate use (RR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.67) (Downing 2014).

One of the studies included in our pooled analysis adjusted for the specific drug that was evaluated in the guideline (thereby reducing the risk of confounding). The authors found no association between financial conflicts of interest and recommendations of a drug, but did not report any effect estimates in the study publication (Norris 2013).

Advisory committee reports

Seven studies investigated a total of 1809 advisory committee reports and data from five studies could be included in our pooled analyses (Ackerley 2009; Lurie 2006; Pham‐Kanter 2014; Tibau 2016; Zhang 2019). In our primary analysis, including four studies of 629 advisory committee reports, the association between any advisory committee report with members with financial conflicts of interest and voting in favour of approving a drug or device was RR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.45, I2: 24% (Analysis 1.1). The Number Needed to Read for advisory committee reports was 7.7 (Appendix 6). In our secondary analysis, including three studies of 17,816 votes, the association between financial conflicts of interest of individual advisory committee members and voting in favour of approving a drug or device was RR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07 to 1.21, I2: 35% (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Secondary analysis: using individual voting level in the analysis on advisory committee reports, Outcome 1: Financial conflicts of interest

The prediction interval for the RR was 0.66 to 2.19 (Appendix 5). Thus, one can expect that advisory committee reports with financial conflicts of interest more often have favourable recommendations compared with advisory committee reports without financial conflicts of interest, but for an individual study of advisory committee reports the association may be reversed.

Two included studies did not report data in a way that enabled us to include them in our pooled analysis. One of the studies investigated the association between conflicts of interest and voting behaviour of 1482 members from 385 advisory committee reports. The authors reported that they found no association between conflicts of interest and voting outcome among members, but did not report any effect estimates on the association (Xu 2017). The remaining study investigated 1483 members from 416 advisory committee reports. The authors found that committee members with financial conflicts of interest had 14.3% greater odds of voting for approval compared with committee members without financial conflicts of interest. However, the estimate was not statistically significant (P value: 0.12) (Cooper 2019).

One of the studies included in the pooled analysis adjusted for medical product and advisory committee meeting characteristics (thereby reducing the risk of confounding) and the association between financial conflicts of interest related to the manufacturing company and favourable recommendations was odds ratio (OR): 4.66, 95% CI: 0.64 to 33.6 (Zhang 2019).

Opinion pieces

Six studies investigated a total of 340 opinion pieces (Bariani 2013; Downing 2014; Hayes 2019; Lerner 2012; Stelfox 1998; Wang 2010) and data from four of these studies including 284 opinion pieces could be included in our pooled primary analysis. The association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in opinion pieces was RR: 2.62, 95% CI: 0.91 to 7.55, I2: 78% (Analysis 1.1). The Number Needed to Read for opinion pieces was 2.3 (Appendix 6).

The prediction interval for the RR was 0.03 to 220.56 (Appendix 5). Thus, one can expect that opinion pieces with financial conflicts of interest more often have favourable recommendations compared with opinion pieces without financial conflicts of interest, but for an individual study of opinion pieces the association may be reversed.

Two included studies did not report data in a way that enabled us to include them in our pooled analysis. One study investigated a mixture of 69 authors of original research papers, review articles, and letters. The study found that authors with financial conflicts of interest related to the drug manufacturer more often had favourable recommendations than authors without financial conflicts of interest (RR: 13.91, 95% CI: 1.99 to 96.97) (Stelfox 1998). The remaining study investigated a mixture of four clinical guidelines, 23 editorials and commentaries, and 40 reviews (mainly narrative) and found that documents written by authors with conflicts of interest more often recommended fibrate use (RR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.67) (Downing 2014).

One of the studies included in the pooled analysis adjusted for characteristics of the trial (e.g. type of intervention and trial conclusion) the editorial commented on (thereby reducing the risk of confounding) and the association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations was OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 0.52 to 3.70 (Bariani 2013).

Narrative reviews

Five studies investigated a total of 497 narrative reviews and data from four of these studies investigating 457 narrative reviews could be included in our pooled primary analysis (Dunn 2016; Hartog 2012; Hayes 2019; Wang 2010). The association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in narrative reviews was RR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.49, I2: 39% (Analysis 1.1). The Number Needed to Read for narrative reviews was 8.3 (Appendix 6).

The prediction interval for the RR of was 0.56 to 2.59 (Appendix 5). Thus, one can expect that narrative reviews with financial conflicts of interest more often have favourable recommendations compared with narrative reviews without financial conflicts of interest, but for an individual study of narrative reviews the association may be reversed.

One included study did not report data in a way that enabled us to include it in our pooled analysis. The study investigated a mixture of four clinical guidelines, 23 editorials and commentaries, and 40 reviews (mainly narrative). The authors found that documents written by authors with conflicts of interest more often recommended fibrate use (RR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.67) (Downing 2014).

Post‐hoc analysis combining all document types. Financial conflicts of interest: differences in recommendations

In a post‐hoc analysis, we combined all types of documents and the association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations was RR: 1.26, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.44, I2: 38% (Analysis 1.1). The Number Needed to Read was 7.1 (Appendix 6).

The prediction interval for the RR was 0.88 to 1.80 (Appendix 5). Thus, one can expect that documents with financial conflicts of interest more often have favourable recommendations compared with documents without financial conflicts of interest, but for an individual study the association may be reversed.

Non‐financial conflicts of interest: differences in recommendations

One study investigated specialty interests and included 12 clinical guidelines on mammography screening. The focus was whether the guideline author team included a radiologist (Norris 2012). In our analysis based on this study, the association between having radiologists in the guideline panel and recommending routine screening for breast cancer was RR: 2.10, 95% CI: 0.92 to 4.77. The Number Needed to Read was 2.1 (Appendix 6).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We found no differences in effect estimates in relation to the type of financial conflicts of interest or the degree of financial conflicts of interest for any document type. We were not able to conduct the planned subgroup analyses in relation to risk of bias in included studies for all document types and development methods for clinical guidelines (Appendix 7).

Sensitivity analyses were robust in 20 of 23 analyses of financial conflicts of interest and in three analyses the association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations became stronger (Appendix 8).

Assessment of certainty of the evidence

The evidence on financial conflicts of interest in all four types of documents and non‐financial conflicts of interest in clinical guidelines should be interpreted with some caution as the majority of the studies (15 out of 21) had a risk of confounding and all effect estimates of the primary analyses lacked statistical precision. Using the GRADE approaches for intervention and prognostic studies resulted in low to very low certainty of the evidence depending on type of document and the GRADE system used (Appendix 9).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 21 studies investigating 106 clinical guidelines, 1809 advisory committee reports, 340 opinion pieces, and 497 narrative reviews. We found an association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations of drugs and devices in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. Our four primary analyses pointed in a consistent direction and provided a fairly similar magnitude of effect, but each with varying degrees of statistical precision. Our post hoc analysis combining all document types confirmed these findings and increased the statistical precision. Our findings on the impact of non‐financial conflicts of interest on recommendations were limited to evidence from a single study of breast cancer screening guidelines with involvement of radiologist authors, with statistically imprecise results. It is therefore uncertain whether specialty interests or other types of non‐financial conflicts of interest impact on recommendations.

Quality of the evidence

All but one of the included studies were assessed as having high risk of bias, mainly due to a high risk of confounding. Documents differed in other aspects than conflicts of interest (e.g. they investigated different drugs used for different patient groups) which could have introduced confounding. For example, if a study included editorials in oncology commenting on numerous drugs. If some drugs are more likely to have editorials written by authors with conflicts of interest (e.g. developed by major drug companies), and if such drugs are more likely to have favourable trial results (i.e. thereby receiving a favourable recommendation in an editorial), this could confound the association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of our study is the inclusion of unpublished data from 11 of 21 studies. We retrieved eight full datasets and unpublished summary data for three additional studies which enabled us to ensure high data quality and to conduct comprehensive analyses thereby increasing statistical precision and minimising reporting bias. Furthermore, we did a thorough search for grey literature and attempted to identify published and unpublished protocols. We only obtained two protocols (Downing 2014; Lurie 2006) and a comparison of outcomes in the protocols with outcomes in the study publications gave no indication of selective outcome reporting.

However, six of 21 included studies were reported in a format that did not allow inclusion in meta‐analysis. Four of these studies reported results similar to our meta‐analysis. Two of the four studies combined different types of documents without stratifying results, with estimates RR: 1.69, 95% CI: 1.07 to 2.67 and RR: 13.91, 95% CI: 1.99 to 96.97) in line with our primary analysis (Downing 2014; Stelfox 1998). The other two of the four studies sampled a single pair of clinical guidelines with and without financial conflicts of interest and in both cases guidelines with conflicts were favourable (George 2014; Schott 2013). The last two of the six studies (29% of all documents) (Cooper 2019; Xu 2017) sampled FDA committee reports from the same period as the studies included in our meta‐analysis, implying a considerable risk of overlapping documents between the studies. The two studies reported no results for our primary analysis and if we had access to raw data we would likely have had to exclude a considerable proportion of the documents from our analyses to avoid double‐counting. Thus, we find it unlikely that our result would have been qualitatively different had the six studies reported results in a format suitable for meta‐analysis.

Furthermore, our findings on the influence of financial conflicts of interest were robust in most of our sensitivity analyses. When our analyses were not robust, the sensitivity analyses generally showed a stronger association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations.

Nevertheless, there are some challenges. First, the different types of documents were described using various terms in the included studies and despite using a comprehensive search strategy we might have missed relevant studies. Furthermore, only four studies were included in each of our four primary analyses. Therefore, our effect estimates have some degree of statistical imprecision and none of our primary analyses were statistically significant at the conventional 5% level. However, the sizes of the effect estimates were similar for clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, and narrative reviews and slightly higher for opinion pieces, and when we combined all document types in a post hoc analysis including 13 studies, we increased the statistical precision and found a statistically significant association with moderate heterogeneity.

Second, our criteria for assessment of risk of bias in relation to confounding might be viewed as quite strict and others may interpret the risk of bias in studies differently. Nevertheless, the majority of studies had a risk of confounding as they compared documents that may differ in other aspects than conflicts of interest (e.g. documents on different drugs used for different patient groups). While confounding could have influenced our estimates, the association between conflicts of interest and recommendations was fairly consistent across document types despite some studies including quite comparable documents (e.g. clinical guidelines on efalizumab for treatment of psoriasis (Schott 2013)), and others including quite different documents (e.g. advisory committee reports on a wide range of different drugs (Pham‐Kanter 2014)). Moreover, recommendations in guidelines and narrative reviews could have been influenced by conflicts of interest in the underlying evidence. For example, in certain clinical fields such as oncology (Andreatos 2017), conflicts of interest are highly frequent which could have impacted the conclusions of clinical trials and systematic reviews (Lundh 2017; Hansen 2019a) and thereby indirectly affected guideline recommendations and potentially result in effect modification. Furthermore, how conflicts of interest in the primary clinical trials and systematic reviews underpinning a guideline are interpreted could be associated with the conflicts of interest of the guideline authors.

Third, the number of authors with financial conflicts of interest may influence recommendations in a document. Our subgroup analyses comparing documents with the majority of authors with financial conflicts of interest versus a minority of authors found no difference in effect. However, the analyses were somehow simplistic and based on few data with statistically imprecise results. Another important aspect is the role of the author with financial conflicts of interest. For example, the chair of a guideline committee or the lead author of a narrative review likely has greater influence on recommendations than an author with a less prominent role. Unfortunately, none of the included studies reported data that allowed such a comparison.

Fourth, 11 of the 21 included studies relied solely on disclosed information in the included documents for coding conflicts of interest. This could have led to an underestimation of our effect estimates, as conflicts of interest are often underreported in various publication types, including clinical guidelines (Bindslev 2013).

Finally, the interpretation of our results can be debated. There is no published guidance specifically tailored for summarising and interpreting evidence from methodological studies. One approach could be to use the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008), but it is questionable whether using GRADE for observational intervention studies or prognostic studies is best suited for methodological studies, since the methodology of studies or the presence of conflicts of interest cannot be randomised. In Appendix 9, we report assessments using both strategies which resulted in low to very low certainty of evidence depending on type of documents and the system used. Using the GRADE approach for intervention studies resulted in a more conservative interpretation of the certainty of the evidence.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Other systematic reviews have focused on financial conflicts of interest in other types of publications and have reported similar findings. A recent updated Cochrane Methodology Review focused on primary research, mainly trials, and found that industry‐funded studies more often had favourable conclusions compared with non‐industry‐funded studies (RR: 1.34, 95% CI: 1.19 to 1.51) (Lundh 2017). Similarly, another recent Cochrane Methodology Review focused on systematic reviews and found that systematic reviews with industry funding or by authors with financial conflicts of interest more often had favourable conclusions compared with systematic reviews without financial conflicts of interest (RR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.26 to 3.11) (Hansen 2019a).

Financial conflicts of interest have also been investigated in relation to other industries and in a systematic review, Chartres and colleagues reported that industry‐funded nutrition studies and reviews more often had favourable conclusions than non‐industry‐funded nutrition studies and reviews (RR: 1.31, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.72) (Chartres 2016).

Meaning of our review

For our analyses, we included studies of four types of documents that both were fairly common and involved authors’ interpretation of external evidence (involving methods less stringent than in a systematic review). Although we had anticipated potential differences between the various types of documents, we found a fairly consistent association between financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. One reason could be that authors with conflicts of interest are more prone to confirm prior beliefs by selectively citing and interpreting the literature (DuBroff 2018). This could also explain the somewhat stronger association found in opinion pieces which to some degree allow authors more room for interpretation than narrative reviews, which undergo peer review, and clinical guidelines, which are increasingly done using standardised methods. On an absolute scale, the association between conflicts of interest and recommendations was particularly strong for opinion pieces and specialty interest in clinical guidelines with Numbers Needed to Read of only 2.3 and 2.1, respectively, although the estimates had considerable statistical imprecision.

Authors' conclusions

Implication for systematic reviews and evaluations of healthcare.

We interpreted our findings to indicate that financial conflicts of interest are associated with favourable recommendations of drugs and devices in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews. Although the magnitude of effect is fairly consistent across document types, most studies had a risk of confounding and our individual analyses of each document type had some degree of statistical imprecision. It is more uncertain whether non‐financial conflicts of interest impact on recommendations.

Our findings support conflicts of interest policies from major guideline issuing organisations such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the US Preventive Services Task Force, and the World Health Organization (NICE 2019; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 2018; WHO 2014). These policies aim to minimise the number and role of guideline authors with conflicts of interest. Similarly, some high impact journals manage conflicts of interest beyond disclosure, for example New England Journal of Medicine prohibits narrative reviews and editorials with significant financial conflicts of interest (> US$ 10,000), and The Lancet prohibits commentaries, seminars, reviews, and series by authors with relevant stock ownership, employment, or company board membership (Bero 2018; Lundh 2020). Other journals should consider introducing such polices in order to minimise the influence from conflicts of interest on journal content.

In line with this, the FDA introduced more stringent criteria on which types of conflicts of interest where allowed for committee members in 2008 (Ackerley 2009). This could be a possible explanation as to why the study by Zhang and colleagues (Zhang 2019), which exclusively sampled advisory committee reports from 2008 and onwards, found a somewhat weaker association between financial conflicts of interest and recommendations in advisory committee reports than the three other studies included in our pooled analyses (Ackerley 2009; Lurie 2006; Tibau 2016).

To minimise influence from conflicts of interest we suggest that patients, clinicians, and healthcare decision makers primarily use clinical guidelines that are based on rigorous methodology and have clear policies of how to manage conflicts of interest, such as excluding or minimising the role of members with conflicts and ensuring a broad skill set in the panel. If such guidelines are not available, users should interpret such guidelines with caution. Similarly, journal readers should prefer publications written by authors without conflicts of interest.

Implication for methodological research.

Ideally, future studies should try to minimise the risk of confounding, e.g. by using a matched study design (Jørgensen 2006). However, identifying editorials commenting on the same study or guidelines addressing the same question and developed using similar methods might be a challenge. Furthermore, future research could focus on investigating whether specific types of financial conflicts of interest (e.g. advisory board membership) or conflicts of interest related to specific companies (e.g. drug manufacturer) have a greater impact than others. Moreover, the included studies used various definitions of financial conflicts of interest and recommendations, and use of a standardised terminology would be helpful.

Investigating the impact of non‐financial conflicts of interest is challenging because no uniform definition exists. On one hand, a multitude of interests such as specialty interests, intellectual interests, personal beliefs, and personal relationships can be viewed as non‐financial conflicts of interest (The PLoS Medicine Editors 2008; Viswanathan 2014). On the other hand, labelling personal beliefs and theoretical schools of thoughts as conflicts of interest risks muddying the waters since no researcher is completely interest free or free from intellectual pre‐conceptions (Bero 2014; Bero 2016; Bero 2017). Furthermore, the distinction between financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest is not always clear. For example, in relation to the included study on mammography screening guidelines (Norris 2012), it can be debated whether being a radiologist should be considered a purely non‐financial conflict of interest because radiologists may have direct financial income from breast cancer screening. Future studies could focus on investigating the impact of the various types of non‐financial conflicts of interest on favourable recommendations and on the impact of managing such interests using guideline panels with a broad range of skill sets, rather than mainly content area experts.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 6, 2013 Review first published: Issue 12, 2020

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 October 2019 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | This protocol was re‐published in October 2019 to generate a new citation, reflecting the change in title and authorship from the original version (Lundh A, Jørgensen AW, Bero L. Association between personal conflicts of interest and recommendations on medical interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. Art. No.: MR000040). |

| 25 April 2018 | Amended | The text has been updated to align it with other Cochrane Methodology reviews on conflicts of interest. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Gloria Won, from UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion, for developing our initial search strategy for an earlier version of the protocol. We thank Herdis Foverskov, from University Library of Southern Denmark, for valuable help in developing and adjusting the search strategies. We thank Ulrich Halekoh, from Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Biodemography at University of Southern Denmark, for valuable statistical guidance.

We thank Aakre, Ackerley, Bariani, Downing, Dunn, George, Hartog, Hayes, Lerner, Lurie, Norris, Pham‐Kanter, Schott, Stelfox, Tibau, Wang, and Zhang and their respective colleagues (authors of included studies) for clarifying issues and sharing protocols and data.

An abridged version of this article is published in BMJ. We thank the editors and peer reviewers for both journals for assistance and comments on the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Terminology

We use the overall term ‘conflicts of interest’ to refer to both financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest as specified below.

We use the definition by the Institute of Medicine (US) and define ‘conflicts of interest’ as “a set of circumstances that creates a risk that professional judgment or actions regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest” (Institute of Medicine 2009). This includes both financial and non‐financial conflicts of interest. By financial conflicts of interest we include authors’ financial relationships, for example employment, research grants, speaker’s bureau membership, stock ownership, and consultancy work and also funding of publication (e.g. a clinical guideline). We focus on financial conflicts of interest related to the drug or device industry. Financial conflicts of interest related to other industries (e.g. tobacco industry) are not included. We define 'drugs' as medications requiring approval from a regulatory authority as a prescription drug. We define 'devices' according to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as instruments used in diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of disease (FDA 2017).

As there is no consensus concerning the definition of non‐financial conflicts of interest, we generally use the definition used by the authors of the included studies. If the authors do not use the term non‐financial conflicts of interest, we use the following subcategories: personal and professional relationships (e.g. research collaboration), professional and specialty interests (e.g. belonging to a certain medial subspecialty), or intellectual and academic conflicts of interest (e.g. authorship of studies that are part of the evidence base for reaching a particular recommendation) (Akl 2014). We do not focus on studies investigating beliefs (e.g. political or religious), personal experience (e.g. abuse or trauma), or institutional conflicts of interest (Bero 2016). In some cases an interest can be considered both a financial and non‐financial. For example, a surgeon who uses a particular surgical intervention which he/she then investigates in a clinical guideline. This can be viewed as a financial conflict of interest, because the surgeon might benefit financially if the intervention is recommended. It can also be viewed as a non‐financial conflict of interest, because the surgeon uses the surgical procedure as part of clinical practice (i.e. specialty interest) or may have conducted some of the studies included in the guideline (i.e. academic interest). For this review, we regard such relationships as non‐financial because they differ from what is typically regarded as financial conflicts of interest (i.e. direct financial relationships with the drug or device industry).

We use the term ‘clinical guidelines’ to refer to guidelines. We define ‘clinical guidelines’ as “Systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances” (Institute of Medicine 1990).

We use the term ‘advisory committee reports’ to refer to reports or transcripts from meetings held in committees, boards, councils, or similar that are established to advise an organisation and provide a recommendation concerning an intervention (e.g. the Food and Drug Administration’s advisory committee on oncological drugs).

We define ‘opinion pieces’ as documents that are not research studies in which an author expresses a personal opinion about a specific intervention (e.g. editorials, commentaries, and letters‐to‐the‐editors).

We define ‘narrative reviews’ as literature reviews without a systematic search of the literature with clear eligibility criteria.

We use the term ‘documents’ to refer to clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews included in the studies.

Appendix 2. PubMed search strategy

Block 1A: drug and device industry

1. Drug Industry (MeSH)

2. Manufacturing Industry (MeSH)

3. (Drug [Title/Abstract] OR drugs[Title/Abstract] OR pharmaceutical[Title/Abstract] OR pharmaceutic [Title/Abstract] OR pharmacological[Title/Abstract] OR pharma*[Title/Abstract] OR biotech*[Title/Abstract] OR bio‐tech[Title/Abstract] OR biopharma*[Title/Abstract] OR bio‐pharma*[Title/Abstract] OR biomed*[Title/Abstract] OR bio‐med*[Title/Abstract] OR device[Title/Abstract] OR devices[Title/Abstract] OR imaging[Title/Abstract] OR for‐profit[Title/Abstract] OR private[Title/Abstract]) AND (industry[Title/Abstract] OR industries[Title/Abstract] OR company[Title/Abstract] OR companies[Title/Abstract] OR manufacturer[Title/Abstract] OR manufacturers[Title/Abstract] OR organisation[Title/Abstract] OR organisations[Title/Abstract] OR organization[Title/Abstract] OR organizations[Title/Abstract] OR agency[Title/Abstract] OR agencies[Title/Abstract] OR sector[Title/Abstract] OR sectors[Title/Abstract])

4. Personal[Title] OR self‐reported[Title] OR selfreported[Title] OR author[Title] OR authors[Title] OR authorship[Title] OR ((committee[Title] OR board[Title]) AND (member[Title] OR members[Title])) OR voting[Title] OR votings[Title] OR financial[Title] OR finance[Title]

5. 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4

Block 1B: financial conflicts of interest

6. Conflict of interest (MeSH)

7. Financial support (MeSH)

8. Research support as topic (MeSH)

9. (Conflict[Title/Abstract] OR conflicts[Title/Abstract] OR conflicting[Title/Abstract]) AND (interest[Title/Abstract] OR interests[Title/Abstract])

10. (Competing[Title/Abstract] OR vested[Title/Abstract]) AND (interest[Title/Abstract] OR interests[Title/Abstract])

11. (Industry[Title/Abstract] OR industries[Title/Abstract] OR company[Title/Abstract] OR companies[Title/Abstract] OR manufacturer[Title/Abstract] OR manufacturers[Title/Abstract] OR finance[Title/Abstract] OR financial[Title/Abstract]) AND (funded[Title/Abstract] OR funding[Title/Abstract] OR sponsor[Title/Abstract] OR sponsors[Title/Abstract] OR sponsorship[Title/Abstract] OR sponsoring[Title/Abstract] OR support[Title/Abstract] OR supported[Title/Abstract] OR finance[Title/Abstract] OR financial[Title/Abstract] OR involvement[Title/Abstract] OR involving[Title/Abstract] OR payment[Title/Abstract] OR payments[Title/Abstract] OR relationship[Title/Abstract] OR relationships[Title/Abstract] OR relation[Title/Abstract] OR relations[Title/Abstract] OR tie[Title/Abstract] OR ties[Title/Abstract] OR collaboration[Title/Abstract] OR collaborations[Title/Abstract])

12. Industry‐funded[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐funding[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐sponsor*[Title/Abstract] OR company‐funded[Title/Abstract] OR company‐funding[Title/Abstract] OR company‐sponsor*[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐support[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐supported[Title/Abstract] OR company‐support[Title/Abstract] OR company‐supported[Title/Abstract]

13. (Commercial‐academic[Title/Abstract] OR academic‐commercial[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐academic[Title/Abstract] OR academic‐industry[Title/Abstract] OR commercial‐industry[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐commercial[Title/Abstract] OR industry‐physician[Title/Abstract] OR physician‐industry[Title/Abstract]) AND (interaction[Title/Abstract] OR interactions[Title/Abstract] OR relationship[Title/Abstract] OR relationships[Title/Abstract] OR relation[Title/Abstract] OR relations[Title/Abstract] OR collaboration[Title/Abstract] OR collaborations[Title/Abstract])

14. 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13

Block 2A: non‐financial, personal, and academic

15. Non‐financial[Title/Abstract] OR nonfinancial[Title/Abstract]

16. Personal[Title] OR individual[Title] OR self‐reported[Title] OR selfreported[Title] OR author[Title] OR authors[Title] OR authorship[Title]

17. Specialist[Title/Abstract] OR specialists[Title/Abstract] OR specialty[Title/Abstract] OR expert[Title/Abstract] OR experts[Title/Abstract] OR intellectual[Title/Abstract] OR intellectuals[Title/Abstract] OR professional[Title/Abstract] OR professionals[Title/Abstract] OR academic[Title/Abstract] OR academics[Title/Abstract]

18. 15 OR 16 OR 17

Block 2B: non‐financial conflicts of interest

19. Conflict of interest (MeSH)

20. Conflict[Title] OR conflicts[Title] OR conflicting[Title] OR competing[Title] OR vested[Title]

21. Relation[Title] OR relations[Title] OR relationship[Title] OR relationships[Title]

22. Interest[Title] OR interests[Title]

23. 19 OR 20 OR 21 OR 22

Block 3: clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports opinion pieces, and narrative reviews

24. (Opinion[Title/Abstract] OR opinions[Title/Abstract] OR policy[Title/Abstract] OR policies[Title/Abstract] OR statement[Title/Abstract] OR statements[Title/Abstract]) AND (piece[Title/Abstract] OR pieces[Title/Abstract] OR article[Title/Abstract] OR articles[Title/Abstract])

25. (Narrative[Title/Abstract] OR descriptive[Title/Abstract] OR non‐systematic[Title/Abstract] OR non‐systematical[Title/Abstract] OR non‐systematically[Title/Abstract] OR nonsystematic[Title/Abstract] OR nonsystematical[Title/Abstract] OR nonsystematically[Title/Abstract]) AND (review[Title/Abstract] OR reviews[Title/Abstract] OR overview[Title/Abstract] OR overviews[Title/Abstract])

26. Non[Title/Abstract] AND (systematic[Title/Abstract] OR systematical[Title/Abstract] OR systematically[Title/Abstract]) AND (review[Title/Abstract] OR reviews[Title/Abstract] OR overview[Title/Abstract] OR overviews[Title/Abstract])

27. Editorial[Title] OR editorials[Title] OR essay[Title] OR essays[Title] OR commentary[Title] OR commentaries[Title] OR comment[Title] OR comments[Title] OR letter[Title] OR letters[Title]

28. (Treatment[Title/Abstract] OR treatments[Title/Abstract] OR screening[Title/Abstract] OR screen[Title/Abstract] OR testing[Title/Abstract] OR test[Title/Abstract] OR tests[Title/Abstract OR diagnostic[Title/Abstract] OR diagnosis[Title/Abstract] OR therapy[Title/Abstract] OR therapies[Title/Abstract]) AND (recommendation[Title/Abstract] OR recommendations[Title/Abstract])

29. Guidelines as Topic (MeSH)

30. Health Planning Guidelines (MeSH)

31. (Clinical[Title] OR clinic[Title] OR health[Title] OR practice[Title]) AND (guideline[Title] OR guidelines[Title] OR recommendation[Title] OR recommendations[Title])

32. (Advisory[Title/Abstract] OR advising[Title/Abstract] OR formulary[Title/Abstract] OR counselling[Title/Abstract] OR counselling[Title/Abstract] OR drug[Title/Abstract] OR drugs[Title/Abstract]) AND (board[Title/Abstract] OR boards[Title/Abstract] OR committee[Title/Abstract] OR committees[Title/Abstract] OR panel[Title/Abstract] OR panels[Title/Abstract] OR meeting[Title/Abstract] OR meetings[Title/Abstract])

33. 24 OR 25 OR 26 OR 27 OR 28 OR 29 OR 30 OR 31 OR 32

Combined searches

34. 5 AND 14

35. 18 AND 23

36. (34 OR 35) AND 33

Appendix 3. Data extraction

Two review authors independently extracted the following information.

Study characteristics

Title.

Name of lead author.

Name of journal.

Year published.

Primary aim of the study.

Design of study: cohort, cross‐sectional study, systematic review or meta‐analysis, or other.

Study domain ‐ category: clinical guideline, advisory committee report, opinion pieces, narrative review, or mixed.

Sample description: for example, clinical guidelines on treatment of hypertensionStrategy used to collect sample: for example, search of PubMed and time period coveredDefinition of clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, or narrative reviews used in the study. Verbatim extraction.

Number of included documents (separate data for clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews).

Types of documents included in the study. Verbatim extraction.

Types of documents included in the study (drug, device or both).

Conflict of interest and outcome data

Definition of financial conflicts of interest used in the study. Verbatim extraction.

Definition of non‐financial conflicts of interest used in the study. Verbatim extraction.

-

Types of financial conflicts of interest investigated, potential categories are:

funding;

author grant;

honorarium;

consulting;

speakers bureau.

Types of non‐financial conflicts of interest investigated.

Definition of favourable recommendations used by the authors of the study. Verbatim extraction.

Definition of primary analysis used in the study. Verbatim extraction.

Total number of documents with and without conflicts of interest. Stratified by type of document (i.e. clinical guideline, advisory committee reports, opinion piece, narrative review) and type of conflicts of interest (i.e. financial, non‐financial).

Number of documents with and without conflicts of interest with favourable recommendations stratified by type of documents (i.e. clinical guideline, advisory committee reports, opinion piece, narrative review) and type of conflicts of interest (i.e. financial, non‐financial).

Any data on estimates of the association between financial conflicts of interest/non‐financial conflicts of interest and recommendations in clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, and narrative reviews (for example, adjusted effect estimates and confidence intervals).

Data for informing subgroup analyses or reflection on heterogeneity

Total number of documents with conflicts of interest and number with favourable recommendations. Stratified by document type (i.e. clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, narrative reviews) and category of financial conflicts of interest (e.g. investigator, grants, honorarium, consulting, speaker’s bureau, equity/stock, gifts).

Any data on the association between each category of financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations.

Total number of clinical guidelines following standardised methods with and without conflicts of interest and number with favourable recommendations. Stratified by type of conflicts of interest (i.e. financial, non‐financial).

Total number of clinical guidelines not following standardised methods with and without conflicts of interest and number with favourable recommendations. Stratified by type of conflicts of interest (i.e. financial, non‐financial).

Any data on the association between conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations for clinical guidelines following standardised methods and clinical guidelines not following standardised methods.

Total number of documents with conflicts of interest and number with favourable recommendations. Stratified by document type (i.e. clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, narrative reviews) and degree of financial conflicts of interest (i.e. major and minor).

Any data on the association between major and minor financial conflicts of interest and favourable recommendations.

Data for performing sensitivity analyses

Total number of documents with and without conflicts of interest and number of documents in each group with favourable recommendations, when excluding documents with unclear or undisclosed conflicts of interest. Stratified by document type (i.e. clinical guidelines, advisory committee reports, opinion pieces, narrative reviews) and type of conflicts of interest (i.e. financial, non‐financial).