Abstract

Background

The policy several countries is to provide people with a terminal illness the choice of dying at home; this is supported by surveys that indicate that the general public and people with a terminal illness would prefer to receive end‐of‐life care at home. This is the fifth update of the original review.

Objectives

To determine if providing home‐based end‐of‐life care reduces the likelihood of dying in hospital and what effect this has on patients' symptoms, quality of life, health service costs and caregivers compared with inpatient hospital or hospice care.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE(R), Embase, CINAHL, and clinical trials registries to 18 March 2020. We checked the reference lists of systematic reviews. For included studies, we checked the reference lists and performed a forward search using ISI Web of Science. We handsearched palliative care journals indexed by ISI Web of Science for online first references.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of home‐based end‐of‐life care with inpatient hospital or hospice care for people aged 18 years and older.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed study quality. When appropriate, we combined published data for dichotomous outcomes using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel meta‐analysis to calculate risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). When combining outcome data was not possible, we reported the results from individual studies.

Main results

We included four randomised trials and found no new studies from the search in March 2020. Home‐based end‐of‐life care increased the likelihood of dying at home compared with usual care (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.52; 2 trials, 539 participants; I2 = 25%; high‐certainty evidence). Admission to hospital varied among the trials (range of RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.79, to RR 2.61, 95% CI 1.50 to 4.55). The effect on patient outcomes and control of symptoms was uncertain. Home‐based end‐of‐life care may slightly improve patient satisfaction at one‐month follow‐up, with little or no difference at six‐month follow‐up (2 trials; low‐certainty evidence). The effect on caregivers (2 trials; very low‐certainty evidence), staff (1 trial; very low‐certainty evidence) and health service costs was uncertain (2 trials, very low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

The evidence included in this review supports the use of home‐based end‐of‐life care programmes for increasing the number of people who will die at home. Research that assesses the impact of home‐based end‐of‐life care on caregivers and admissions to hospital would be a useful addition to the evidence base, and might inform the delivery of these services.

Plain language summary

Home‐based end‐of‐life care

What was the aim of this review?

We systematically reviewed the literature to see if the provision of end‐of‐life home‐based care reduced the likelihood of dying in hospital and what effect this has on patients' and caregivers' satisfaction and health service costs, compared with being admitted to a hospital or hospice. This is the fifth update of the original review.

Key messages

People who receive end‐of‐life care at home are more likely to die at home. There were few data on the impact of home‐based end‐of‐life services on family members and lay caregivers.

What was studied in the review?

Several countries have invested in health services to provide care at home to people with a terminal illness who wish to die at home. The preferences of the general public and people with a terminal illness seem to support this, as most people indicate that they would prefer to receive end‐of‐life care at home.

What were the main results of the review?

We included four trials in our review. We found that people receiving end‐of‐life care at home were more likely to die at home. Admission to hospital while receiving home‐based end‐of‐life care varied between trials. People who received end‐of‐life care at home may have been slightly more satisfied after one month. The impact of home‐based end‐of‐life care on caregivers, healthcare staff and health service costs was uncertain. There were no data on costs to participants and their families.

How up‐to‐date was this review?

We searched for studies up to 18 March 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Participant outcomes for home‐based end‐of‐life care.

| Participant outcomes for home‐based end‐of‐life care | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people referred for end‐of‐life care Settings: Norway, the UK, the USA Intervention: home‐based end‐of‐life care Comparison: combination of services that could include routine (not specialised) home care, acute inpatient care, primary care services and hospice care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Home‐based end‐of‐life care | |||||

| Place of death (home) Follow‐up: 6–24 months | 525 per 1000 | 688 per 1000 (588 to 798) | RR 1.31 (1.12 to 1.52) | 539 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Home‐based end‐of‐life care increased the likeliood of dying at home compared with usual care (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999). The cluster randomised trial reported that 54/229 (24%) participants allocated to the intervention vs 26/189 (13.80%) participants allocated to usual care died at home (Jordhøy 2000; 24‐month follow‐up) |

|

Unplanned admission to hospital Follow‐up: 6–24 months |

Estimates ranged from a relative increase in risk of admission to hospital of 2.61 (95% CI 1.50 to 4.55) to a relative reduction in risk of 0.62 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.79). | 710 (3 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

Admission to hospital while receiving home‐based end‐of‐life care varied among trials (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Hughes 1992). Data were not pooled due to the high degree of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 91%). The cluster randomised trial reported that 218/235 (92.8%) participants allocated to the intervention vs 186/199 (93.5%) participants allocated to usual care were admitted to hospital during the 2‐year follow‐up (Jordhøy 2000). |

||

| Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms | There may be a small difference in participants pain control assessed by caregivers (4‐point scale: MD –0.48 points, 95% CI –0.93 to –0.03). Little or no difference to functional status, psychological well‐being or cognitive status. |

168 (1 study) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb |

We are uncertain about the effect of home based end‐of‐life care on participant health outcomes or satisfaction (Hughes 1992). Functional status was measured using the Barthel Index, psychological well‐being using the Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale and cognitive status using the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire. Symptoms were measured on a 4‐point scale (low score indicated less of a problem). |

||

|

Patient satisfaction Follow‐up: 1–6 months |

There was a small increase in satisfaction for participants receiving end‐of‐life care at home at 1 month, and little or no difference between groups at 6 months, assessed with the Reid‐Gundlach Satisfaction with Services questionnaire (Brumley 2007) and the National Hospice Study survey (Hughes 1992). | 199 (2 studies) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc |

Home‐based end‐of‐life care may slightly improve patient satisfaction at 1‐month follow‐up, the effect on patient satisfaction at 6‐months is uncertain due to a reduced number of participants providing data for this outcome. | ||

|

Caregiver outcomes Follow‐up: 6 months |

1 study reported a reduction in psychological well‐being for caregivers of participants who had survived > 30 days (Hughes 1992). 1 study reported little or no difference in caregiver response to a questionnaire assessing bereavement (Grande 2004). | 400 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb |

We are uncertain of the effects of the intervention on caregiver outcome, assessed by the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale and the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief; 59 participants provided data in Hughes 1992, and 85 in Grande 1999. | ||

| Staff views on the provision of services | District nurses reported that there should have been additional help for the caregivers (mean score: intervention group: 1.36, SD 0.60; control group: 1.81, SD 0.87; P = < 0.01) and additional help with night nursing (mean score: intervention group: 1.43, SD 0.64; control group: 2.03, SD 0.84; P < 0.0001). | 176 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowd,e |

Staff's assessment of the impact of end‐of‐life care at home on caregivers and additional support required was uncertain. Staff assessed using a 3‐point scale, a lower score indicated less of a problem (Grande 2004). |

||

| Health service resource use and cost | There was a reduction in total health service cost of 18–30% for participants receiving end‐of‐life care at home (Brumley 2007; Hughes 1992). | 199 (2 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowd,f,g |

The effect of home‐based end‐of‐life care on health service resource use and cost was uncertain. | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to inconsistency of findings among studies and risk of bias. bDowngraded three levels due to imprecision and indirectness from a range of different measures of outcome. cDowngraded two levels due to inconsistency and imprecision. dDowngraded one level due to imprecision. eDowngraded two levels due to indirectness as healthcare staff assessed caregivers' experience. fDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. gDowngraded one level due to indirectness as studies reported different healthcare resources.

Background

Description of the condition

Surveys of the preferences of the general public and terminally ill people report that given adequate support, most people would prefer to receive end‐of‐life care at home (Ali 2019; Arnold 2015; Gomes 2012; Higginson 2000; NHS England 2014). The preference of patients who do not have caregivers is less clear. While a policy supporting choice is broadly endorsed (Choice in End of Life Care 2015; ELCC 2016; NHS England 2014), it brings with it conceptual and methodological difficulties for those evaluating the effectiveness of these types of services and further challenges to those responsible for implementing these interventions, due to patient and caregiver preference changing over time.

Description of the intervention

End‐of‐life care at home is the provision of a service that provides active treatment for continuous periods of time by healthcare professionals in the patient's home for patients who would otherwise require hospital or hospice inpatient end‐of‐life care.

How the intervention might work

The rationale for providing end‐of‐life care at home is complex as it reflects the policy objective of providing patients and their families with a choice of where and when they want care. One difficulty underpinning the concept of choice in this context is that while more people want to die at home, they also recognise the practical and emotional difficulties of exercising this choice. For example, terminally ill people express concern about being a 'burden' to family and friends and worry about their families seeing them in distress or having to get involved with intimate aspects of care (Gott 2004). Similarly, although caregivers of terminally ill people often prefer to care for their relatives at home (Woodman 2016), continuity of care may be difficult to achieve, and yet it might be essential to fulfil the choice of dying at home (Seamark 2014).

Why it is important to do this review

In some countries, namely the UK, the US and Canada, the number of people dying at home has increased (Decker 2006; NHS England 2014; Wilson 2009), whereas in others, for example Italy (Cohen 2017) and Japan (Koyama 2020), it has decreased. One retrospective cohort study of Taiwanese patients who died of cancer reported a decrease in the proportion of patients dying at home from 36% to 32%, due to access to treatments that were only available in hospital palliative‐care settings (Tang 2010). Although data indicate a small increase in the number of people who have died at home in the UK, it was estimated that in 2013 22% of people died at home, 22% died in care homes, 6% in hospices, and 48% in hospital (NEoLCIN 2014). The reduction in the proportion of people dying in hospital could be attributed, at least in part, to the improvements in care and services as a result of the 2008 National End of Life Care Strategy (NHS England 2014). Explanations for the large proportion of people still dying in hospital include poorly co‐ordinated services with variable provision, making it difficult for people to be transferred between settings (National Audit Office 2008). Improved collaboration between health and social care and acute and community services, improved pain control and 24‐hour care and support that is provided seven days a week could improve the quality of care, reduce emergency admissions and allow more people to die in the place of their choosing (National Audit Office 2008; NEoLCIN 2014). This is the fifth update of the original review.

Objectives

To determine if providing home‐based end‐of‐life care reduces the likelihood of dying in hospital and what effect this has on patients' symptoms, quality of life, health service costs, and caregivers compared with inpatient hospital or hospice care.

We addressed the following questions.

Are people who receive end‐of‐life care at home more likely to die at home than those who are allocated to inpatient hospital or hospice care?

Do people receiving end‐of‐life care at home have an increased risk of unplanned or precipitous admission to hospital?

Do people who receive end‐of‐life care at home have better symptom control than those who are allocated to inpatient hospital or hospice care?

Does patient and caregiver satisfaction differ between end‐of‐life care at home and inpatient hospital care?

Does providing end‐of‐life care at home alter the costs to health services?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included individual participant randomised trials, and cluster randomised trials with at least two intervention sites and two control sites.

Types of participants

We included evaluations of end‐of‐life care at home for people aged 18 years and over who were at the end of life and required terminal care.

Types of interventions

We included studies comparing end‐of‐life care at home with inpatient hospital or hospice care. The end‐of‐life care at home (which may be referred to as terminal care at home, hospital at home or hospice at home) studies could have included people referred directly from the community who therefore had no physical contact with the hospital, or those referred from the emergency department or hospital inpatient services. We used the following definition to determine if studies should be included in the review: end‐of‐life care at home is a service that provides active treatment for continuous periods of time by healthcare professionals in the patient's home for patients who would otherwise require hospital or hospice inpatient end‐of‐life care.

Types of outcome measures

Main outcomes

Place of death

Unplanned or precipitous admission to hospital

Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms

Patient satisfaction

Caregiver outcomes

Staff views on the provision of services

Health service resource use and cost

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases to 18 March 2020: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (the Cochrane Library), Ovid MEDLINE (from 1950), Embase (from 1980), CINAHL (from 1982), ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform). We provided full details of the search terms used in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of articles identified electronically for evaluations of end‐of‐life home‐based care and obtained potentially relevant articles. We performed a forward search for all included studies, considering all cited studies since the last update (2016 to March 2020), using ISI Web of Science. We searched the online database PDQ‐Evidence to identify other systematic reviews and their primary studies. We handsearched palliative care journals indexed by ISI Web of Science for online first references (American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; BMC Palliative Care; BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care; Journal of Palliative Medicine; Palliative Medicine; Palliative & Supportive Care). We sought unpublished studies by contacting providers and researchers known to be involved in this field. In previous updates, we developed a list of contacts using the existing literature and following discussion with researchers in the area.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (DGB or SS) read all the abstracts in the records retrieved by the electronic searches to identify publications that appeared to be eligible, screened the relevant trials retrieved by the clinical trials registry as well as the identified systematic review, and handsearched relevant publications in palliative care. Two review authors (DGB and SS) independently read the full‐text publications that appeared to be eligible for this update and resolved any disagreements by discussion with another review author (BW).

Data extraction and management

For the previous updates, two review authors (SS and BW or SS and SES) completed data extraction independently using a checklist developed by Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC), modified and amended for the purposes of this review (EPOC 2010). The current update identified no new trials.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SS and BW or SS and SES or SS and DGB) independently assessed risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' criteria (Higgins 2011); these included selection bias, performance and detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and if the control group received the intervention.

Measures of treatment effect

When appropriate, we combined published data for dichotomous outcomes using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel meta‐analysis to calculate risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). When combining outcome data was not possible, we reported the results from individual studies.

Unit of analysis issues

Jordhøy 2000 was a cluster‐randomised trial; this was considered in the published analysis for some of the reported outcomes. For the outcomes place of death and admission to hospital, we reported the number of events and number of participants for these outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors for details of missing data and for clarification of reported data. We reported the amount of missing data in our assessment of loss to follow‐up.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We quantified heterogeneity using Cochrane's Q and the I2 statistic, the latter quantifying the percentage of the total variation across studies that was due to heterogeneity rather than chance (Cochrane 1954; Higgins 2003); smaller percentages suggest less observed heterogeneity. Statistical significance throughout was taken at the two‐sided 5% level (P < 0.05) and we presented data as the estimated effect with 95% CIs. When combining outcome data was not possible because of differences in the reporting of outcomes, we reported the findings of the individual studies.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not have access to the protocols of the included studies, and assessed reporting bias by comparing the range of outcomes described in the methods and reported in the results.Due to the small number of studies we did not construct a funnel plot to assess reporting bias.

Data synthesis

We combined the published data for dichotomous outcomes using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel meta‐analysis (Bradburn 2007). We expressed the pooled effect as an RR for end‐of‐life home‐based care compared with usual hospital care; values greater than 1 indicated outcomes favouring end‐of‐life care at home, and less than 1 for other outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not plan a subgroup analysis and did not conduct a post hoc subgroup analysis. We assessed factors that contributed to heterogeneity by comparing the characteristics of the study populations, intervention and settings across the studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not plan a priori sensitivity analysis and did not perform post hoc sensitivity analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using the following outcomes: place of death; unplanned/precipitous hospital admission; health outcomes (including control of symptoms), patient satisfaction; family or caregiver outcomes, staff views and health service resource use and costs. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and risk of bias) to assess the certainty of the evidence as it related to the main outcomes (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

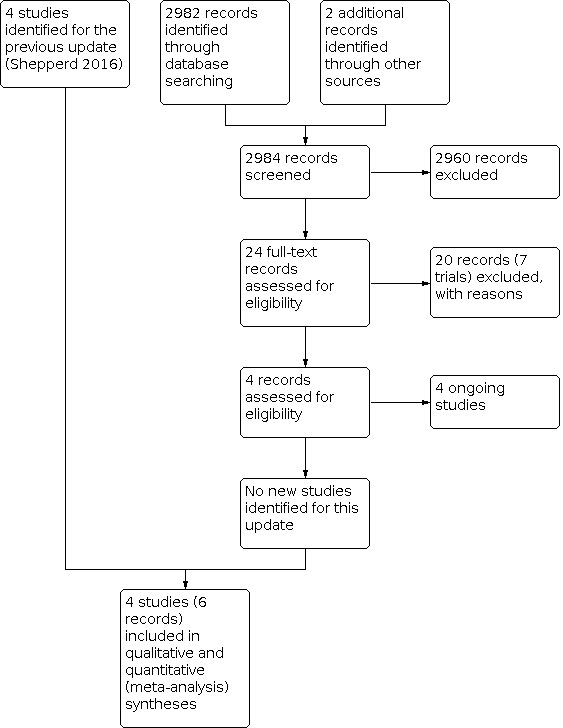

For this update, we retrieved 2984 records, from which we identified 24 potentially relevant records. Seven trials (20 records) were not eligible (Figure 1). We identified no new trials for this update but found four ongoing trials (Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included four published randomised trials (six records), three randomised individual participants (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Hughes 1992), and one cluster trial randomised eight healthcare districts and merged two of the sites that had a small number of inhabitants who were aged greater than 60 years with two larger districts/sites (Jordhøy 2000). Two randomised controlled trials were conducted in the US (Brumley 2007; Hughes 1992), one in Norway (Jordhøy 2000), and one in the UK (Grande 1999). Trials were funded by health services research programmes (Grande 1999; Hughes 1992; Jordhøy 2000) or a non‐profit healthcare plan (Brumley 2007).

The mean age of participants ranged from 63 years to 74 years, with similar proportions of men and women. Between 17% and 36% of participants lived alone (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Jordhøy 2000). In one trial, conducted in the US, 21% of participants had a diagnosis of late‐stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 33% of heart failure and 47% of cancer, with an estimated life expectancy of 12 months or less (Brumley 2007). The most common diagnosis in the second trial conducted in the US was cancer (73% in the intervention group and 80% in the control group) (Hughes 1992). In Grande 1999, conducted in the UK, 86% of participants had a diagnosis of cancer and the survival from referral was a median of 11 days. Jordhøy 2000, conducted in Norway, recruited participants with incurable malignant diseases, excluding those with haematological malignant disease other than lymphoma.

The intervention in three trials was multidisciplinary care, which included specialist palliative‐care nurses, family physicians, palliative‐care consultants, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nutritionists and social care workers (Brumley 2007; Hughes 1992; Jordhøy 2000). In one trial, the focus of the intervention was on nursing care, which was only available for the last two weeks of life (Grande 1999). Three trials provided nursing care for 24 hours if required; in the trial conducted in Norway, the smallest urban district did not have access to 24‐hour care. The intervention evaluated by Jordhøy 2000 was hospital‐based at the Palliative Medicine Unit, which provided community outreach. The intervention had four components:

all inpatient and outpatient hospital services were provided at the Palliative Medicine Unit unless care was required elsewhere for medical reasons;

the Palliative Medicine Unit served as a link to the community services, and the palliative‐care physician and community nurse were defined as the main caregivers;

predefined guidelines were used to keep optimal interaction between services; and

community professionals were offered an educational programme that included bedside training and six to 12 hours of lectures every six months. The lectures addressed the most frequent symptoms and difficulties in palliative care.

Community staff provided follow‐up consultations. In one trial, the intervention group had access to standard care services that were also available to the control group, this was care provided by general practitioners (GP) and other community care services when hospital at home care was not provided 24 hours a day (Grande 1999).

Participants received end‐of‐life care at home for a maximum of 14 days in Grande 1999, a mean of 68 days in Hughes 1992, and two trials did not report the duration of care (Brumley 2007; Jordhøy 2000).

Two trials described an educational component. In one, this was for the participants and their families and included identifying goals of care and the expected course of the disease and outcomes, as well as the likelihood of success of various treatments (Brumley 2007). In the other trial, community staff provided an educational programme (Jordhøy 2000). In two trials, the service was co‐ordinated by a nurse (Grande 1999; Jordhøy 2000); one was physician‐led (Hughes 1992), and in one a core team of physician, specialist nurse and social worker managed care across settings and provided assessment, evaluation, planning, care delivery, follow‐up, monitoring and reassessment of care (Brumley 2007).

The care that the control group received varied across trials and reflected differences in health systems and how standard care was delivered. Two trials described this as including home care (though not specialised end‐of‐life care), acute inpatient care, primary care services and inpatient hospice care (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999). In one trial, the control group received inpatient care at a Veterans Administration (VA) hospital (Hughes 1992), and another trial shared usual care among the hospital departments and the community (Jordhøy 2000) (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Excluded studies

We excluded 17 trials, seven of which reported an intervention that did not provide home‐based end‐of‐life care or was not an alternative to inpatient hospital or hospice care (Brännström 2014; Brumley 2003; Holdsworth 2015; Hughes 1990; Hughes 2000; NCT01885637; Zimmerman 2014), and six trials for which the comparison group received care at primary healthcare centres or hospital outpatient departments (Enguidanos 2019; Markgren 2019; McCaffrey 2013; Ng 2018; NTR2817; Scheerens 2020). Two trials did not fulfil the criterion for study design (Enguidanos 2005; McCusker 1987). One trial was terminated due to the difficulties recruiting participants (McWhinney 1994). We could not locate outcome data or details of the control group for one trial (Stern 2006) (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

Studies awaiting classification

No studies are awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We found four ongoing studies (NCT03793803; NCT03798327; NCT04048590; NCT04243538). We will assess these for inclusion in future versions of this review when data are available (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Two trials described a method of randomisation and allocation concealment and were at low risk of bias (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999). Details were unclear in one study (Hughes 1992), and we assessed one trial at high risk of selection bias as the process of random allocation of the eight clusters was not described (Jordhøy 2000).

Three trials were at low risk of bias for baseline characteristics and differences in outcomes measured at baseline (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Hughes 1992). This was unclear for one trial (Jordhøy 2000).

Blinding

Blinding was not possible in any of the trials, and we assessed performance and detection bias as unclear in three trials (Brumley 2007; Hughes 1992; Jordhøy 2000), and low risk in one trial as outcome data on mortality and place of death were obtained from the Office of National Statistics (Grande 1999).

Incomplete outcome data

All four trials were at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Hughes 1992; Jordhøy 2000).

Selective reporting

There was no evidence of selective reporting of outcome data in Grande 1999 and Jordhøy 2000. This was unclear for Brumley 2007 and Hughes 1992.

Protection against contamination

Three trials were at low risk of bias for protection against contamination as participants allocated to the control group did not have access to the intervention (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Jordhøy 2000). This was unclear for Hughes 1992.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Explanations for the assessments of uncertainty measured by the GRADE criteria are described in Table 1.

Place of death

We were able to combine data from two trials to assess the effectiveness of end‐of‐life home‐based care on dying at home. We found that home‐based end‐of‐life care increased the likelihood of dying at home compared with usual care that included hospice care, inpatient care and routinely available primary healthcare (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.52, P = 0.0005; I2 = 25%; 2 trials, 539 participants; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). A cluster randomised trial reported that 54/229 (24%) participants allocated to end‐of‐life care at home died at home, 146/229 (64%) died in hospital and 19/229 (8%) died in a nursing home; of those allocated to usual care, 26/189 (14%) died at home, 114/189 (60%) died in hospital and 36/189 (19%) died in a nursing home (Analysis 1.2) (Jordhøy 2000). One trial reported that 113/186 (61%) participants allocated to end‐of‐life home‐based care received this form of care (Grande 1999); and 152/186 (82%) participants in the end‐of‐life home care group spent time at home in the last two weeks of life, compared with 34/44 (77%) in the usual care group (Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Place of death, Outcome 1: Dying at home

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Place of death, Outcome 2: Dying at home, in hospital or a nursing home

| Dying at home, in hospital or a nursing home | |

| Study | Outcomes |

| Jordhøy 2000 |

Dying at home Intervention group: 54/229 (23.60%); control group: 26/189 (13.80%) Dying in hospital Intervention group: 146/229 (63.76%); control group: 114/189 (60.32%) Dying in a nursing home Intervention group: 19/229 (8.30%); control group: 36/189 (19.05%) |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Place of death, Outcome 3: Number at home for some or all the last 2 weeks

| Number at home for some or all the last 2 weeks | |

| Study | Outcomes |

| Grande 1999 | Intervention group: 152/186 (82%); control group: 33/43 (77%); P = 0.46 (reported Grande 2000, Figure 1) |

Unplanned admission to hospital

Three patient‐randomised trials assessed the effectiveness of end‐of‐life home‐based care on unplanned admission to hospital (Brumley 2007; Grande 1999; Hughes 1992). Due to a high level of statistical heterogeneity, we did not retain this meta‐analysis and downgraded the evidence due to inconsistency of findings among studies (710 participants; Chi2 = 23.47, degrees of freedom = 2, P < 0.00001, I2 = 91%). Estimates ranged from a relative increase in admission to hospital of 2.61 (95% CI 1.50 to 4.55) to a relative reduction of 0.62 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.79) with a follow‐up between six and 24 months (low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Unplanned admissions to hospital, Outcome 1: Admitted to hospital

Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms

We are uncertain about the impact of home‐based end‐of‐life care on functional status (measured using the Barthel Index), psychological well‐being or cognitive status (1 trial, 168 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3) (Hughes 1992).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 1: Functional status

| Functional status | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Hughes 1992 |

At 6 months (mean) Intervention group: 72, 18 participants; control group: 69.31, 16 participants |

High attrition in both groups due to death. Used the Barthel Self‐Care Index with modified scoring system. No P value given, insufficient data to calculate CI. |

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 2: Psychological well‐being

| Psychological well‐being | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Hughes 1992 |

At 6 months (mean) Intervention group: 1.54, 17 participants; control group: 1.57, 14 participants |

High attrition in both groups due to death. Used Philadelphia Geriatric Morale Scale (shortened version). No P value given, insufficient data to calculate CI. |

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 3: Cognitive status

| Cognitive status | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Hughes 1992 |

At 6 months (mean) Intervention group: 8.33, 18 participants, control group: 8.86, 14 participants |

High attrition in both groups due to death. Used Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (10 items). No P value given, insufficient data to calculate CI. |

One trial reported data on the control of participant symptoms, obtained from GPs, district nurses, and informal caregivers, as previous attempts to obtain data directly from participants proved unsuccessful (Grande 1999). There were a few small differences (low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 5: Caregivers' ratings of symptoms

| Caregivers' ratings of symptoms | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Grande 1999 |

Pain, mean (standard deviation (SD))a Intervention group: 2.49 (0.92), 84 participants; control group: 3.12 (1.05), 17 participants; P < 0.05 Nausea/vomiting, mean (SD)a Intervention group: 1.91 (0.87), 87 participants; control group: 2.47 (1.07), 17 participants; P < 0.05 Constipation, mean (SD)a,b Intervention group: 2.32 (1.09), 82 participants; control group: 2.50 (0.97), 16 participants Diarrhoea, mean (SD)a,b Intervention group: 1.49 (0.88), 81 participants; control group: 1.60 (0.98), 15 participants Breathlessness, mean (SD)a,b Intervention group: 2.39 (1.17), 87 participants; control group: 2.21 (1.19), 14 participants Anxiety, mean (SD)a,b Intervention group: 2.45 (1.05), 80 participants; control group: 2.50 (1.10), 6 participants Depression, mean (SD)a,b Intervention group: 2.08 (0.97), 84 participants; control group: 1.93 (1.14), 144 participants Support with night nursing, mean (SD)b Intervention group: 1.42 (0.73), 108 participants; control group: 1.39 (0.72), 18 participants Help with patient care, mean (SD)b Intervention group: 1.41 (0.69), 106 participants; control group: 1.52 (0.75), 21 participants |

4‐point scale completed by the caregiver. Informal carer ratings of needs for more support and patient's severity of symptoms during patient's final 2 weeks. Lower score indicates less of a problem. aPatients at home only. bAuthors reported not statistically significant |

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 6: General practitioners' ratings of symptoms

| General practitioners' ratings of symptoms | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Grande 1999 |

Pain, mean (standard deviation (SD))a Intervention group: 2.03 (0.73), 130 participants; control group: 2.35 (0.95), 31 participants Nausea/vomiting, mean (SD)a Intervention group: 1.78 (0.82), 129 participants; control group: 2.00 (1.02), 30 participants Constipation, mean (SD)a Intervention group: 1.81 (0.78), 127 participants; control group: 1.97 (0.94), 29 participants Diarrhoea, mean (SD)a Intervention group: 1.17 (0.49), 127 participants; control group: 1.36 (0.73), 29 participants Breathlessness, mean (SD)a Intervention group: 1.82 (1.01), 129 participants; control group: 1.66 (0.93), 29 participants Anxiety, mean (SD) Intervention group: 2.10 (0.95), 127 participants; control group: 2.50 (0.97), 30 participants; P < 0.05 Depression, mean (SD) Intervention group: 1.62 (0.76), 125 participants; control group: 2.19 (1.08), 27 participants; P < 0.01 |

Intention‐to‐treat analysis 4‐point scale completed by the general practitioner. Lower score indicated less of a problem. No difference detected for ratings reported by district nurses and informal caregivers. Patients at home only. aAuthors reported not statistically significant. |

Patient satisfaction

Home‐based end‐of‐life care may slightly increase patient satisfaction (2 trials; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 3.4). Participants receiving end‐of‐life home‐based care reported greater satisfaction than those in the hospital group at one‐month follow‐up (Hughes 1992). This difference disappeared at six‐month follow‐up, which may reflect a reduced sample size due to the death of some participants. Brumley 2007 reported higher levels of satisfaction by participants receiving end‐of‐life home‐based care at 30 days (odds ratio (OR) 3.37, 95% CI 1.42 to 8.10) and not at 60 days (OR 1.79, 95% CI 0.65 to 4.96) (Brumley 2007).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms, Outcome 4: Patient satisfaction

| Patient satisfaction | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Brumley 2007 |

At 30 days Odds ratio (OR) 3.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.42 to 8.10; 216 participants provided data, data was not reported by group At 60 days OR 1.79, 95% CI 0.65 to 4.96; 168 participants provided data, data was not reported by group. |

Satisfaction measured using the Reid‐Gundlack Satisfaction with Service instrument, a total possible score of 48. |

| Hughes 1992 |

At 1 month Authors reported satisfaction was higher in the end‐of‐life home‐based care group; P = 0.02 At 6 months, mean Intervention group: 2.72, 17 participants; control group: 2.45, 14 participants; P = 0.06 |

17‐item questionnaire derived from the National Hospice Study. Number contributing to this outcomes was not reported. |

Caregiver outcomes

We are uncertain whether home‐based end‐of‐life care improves caregiver outcomes (two trials; very low‐certainty evidence) (Grande 2004; Hughes 1992). In one trial, caregivers of participants receiving end‐of‐life home‐based care reported higher satisfaction compared with caregivers in the control group at one‐month follow‐up (Hughes 1992). This difference disappeared at six months, which may reflect a reduced sample size. At six‐month follow‐up, caregivers of participants in the end‐of‐life home‐based care group who had survived more than 30 days reported a decrease in psychological well‐being compared with caregivers looking after participants in the control group (measured by the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale). Grande 2004 found end‐of‐life care at home may make little or no difference for caregiver bereavement response six months following death (low‐certainty evidence) (measured by the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief) (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: mean 46.5, standard deviation (SD) 12.9; control group: mean 46.8, SD 11.8; Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Caregiver outcomes, Outcome 1: Caregiver outcomes

| Caregiver outcomes | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Grande 1999 |

Bereavement, mean (standard deviation (SD)) Intervention group: 46.5 (12.9), 70 participants; control group: 46.8 (11.8), 15 participants |

Measured using Texas Revised Inventory of Grief, which is composed by 2 scales (8 and 13 items); higher scores indicated a worse outcome (as described by Grande 2004). |

| Hughes 1992 |

At 1 month Carers in intervention group reported a greater level of satisfaction, data not reported. At 6 months Authors reported not significant (P = 0.12) |

Number of participants contributing data for this outcome was not reported. |

Staff views on the provision of services

One study reported the views of GPs and district nurses on the provision of services for participants who received home‐based end‐of‐life care (Grande 1999; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 5.1). District nurses reported that there should have been additional help for the caregivers looking after the participants in the control group (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: mean score 1.36, SD 0.60; 141 participants; control group: mean score 1.81, SD 0.87; 31 participants; P ≤ 0.01) and that there should have been additional help with night nursing for the control group (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: mean score 1.43, SD 0.64; 143 participants; control group: mean score 2.03, SD 0.84; 33 participants; P < 0.0001), both measured on a 3‐point scale with lower scores indicating less of a problem. There were small differences between groups in ratings by GPs and of caregivers ratings of the same domains (Analysis 3.5; Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Staff views on the provision of services, Outcome 1: District nurse and general practitioner views

| District nurse and general practitioner views | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Grande 1999 |

District nurse thought there should be additional help for the caregiver to look after the patient, mean (standard deviation (SD)) Intervention group: 1.36 (0.60), 141 participants; control group: 1.81 (0.87), 31 participants; P ≤ 0.01 General practitioner (GP) thought there should be additional help for the caregiver to look after the patient, mean (SD) Intervention group: 1.51 (SD 0.66), 128 participants; control group: 1.73 (0.83), 31 participants District nurse thought there should be more help with night nursing, mean (SD) Intervention group: 1.43 (0.64), 143 participants; control group: 2.03 (0.84), 33 participants; P < 0.0001 GP thought there should be more help with night nursing, mean (SD) Intervention group: 1.53 (SD 0.70), 129 participants; control groups: 1.79 (SD 0.86), 29 participants |

3‐point scale with lower scores indicating less of a problem. No difference for the ratings reported by GPs and informal caregivers. |

Health service resource use and cost

Grande 1999 and Hughes 1992 reported data on the use of healthcare services (very low‐certainty evidence). Grande 1999 reported that during their penultimate week of life, the end‐of‐life home‐based care group had fewer GP evening visits compared to the control group (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: mean 0.17 visits, SD 0.46; control group: mean 0.61 visits, SD 1.42; P < 0.05) and fewer GP night visits than those receiving usual care (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: mean 0.04 visits, SD 0.20; control group: mean 0.26 visits, SD 0.55; P < 0.001; Analysis 6.1). Hughes 1992 reported a reduction in the mean number days in hospital for participants receiving end‐of‐life home‐based care (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: 9.94 days, SD 13.3; control group: 15.86 days, SD 20.1; P = 0.03; Analysis 6.1). Jordhøy 2000 reported little difference in mean length of hospital stay (end‐of‐life care‐at‐home group: 10.5 days, SD 7.3); 235 participants; control group: 11.5 days, SD 8.9; 199 participants). One study reported total costs including VA hospital, private hospital, nursing home, outpatient clinic, home care and community nursing (Hughes 1992), and reported little difference in total costs (home‐based home care: mean cost USD 3479; usual care: mean cost USD 4249). Brumley 2007 reported that the mean cost per day incurred by participants receiving end‐of‐life home‐based care was lower than for those receiving standard care (MD –117.50, P = 0.02), and that the overall mean cost (adjusted for survival, age, and severity of illness) to the health service was USD 12,670 (SD 12,523) compared with USD 20,222 (SD 30,026) for usual care. None of the studies reported costs to the participants or the caregivers.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Health service resource use and cost, Outcome 1: Health service use

| Health service use | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Grande 1999 |

General practitioner (GP) workload in penultimate week of life –visits, mean (standard deviation (SD)) Daytime during the week Intervention group: 2.18 (1.73); control group: 2.32 (2.42) Daytime during the weekend Intervention group: 0.35 (0.81); control group: 0.39 (0.68) Evening home visits Intervention group: 0.17 (0.46); control group: 0.61 (1.42); P < 0.05 Night visits Intervention group: 0.04 (0.20); control group: 0.26 (0.55); P < 0.001 GP workload in last week of life –visits, mean (SD) Daytime during the week Intervention group: 2.92 (2.2); control group: 3.03 (3.18) Daytime during the weekend Intervention group: 0.63 (1.07); control group: 0.95 (1.56) Evening home visits Intervention group: 0.59 (0.91); control group: 1.11 (1.56) Night time visits Intervention group: 0.47 (0.82); control group: 0.63 (1.10) |

Penultimate week of life Intervention group: 150–151 participants; control group: 37–38 participants Final week of life Intervention group: 150–151 participants; control group: 38 participants |

| Hughes 1992 |

Veterans Administration (VA) services at 6 months, mean (SD) General bed days Intervention group: 5.63 (10); control group: 12.06 (15.2); mean difference (MD) 6.43 days (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.55 to 10.3); P = 0.002 All hospital days Intervention group: 9.94 (13.3); control group: 15.86 (20.1); MD 5.92 (95% CI 0.78 to 11); P = 0.03 |

Intervention group: 86 participants; control group: 85 participants |

| Jordhøy 2000 |

Mean length of hospital admission, mean (SD) Intervention group: 10.5 days (7.3); control group: 11.5 days (8.9) |

Intervention group: 235 participants; control group: 199 participants |

Discussion

Despite the widespread support for models of care that better serve the needs of patients at the end of their life, there is limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of home‐based end‐of‐life care. This is not surprising given the difficulties in conducting research in this area.

Summary of main results

Those participants receiving home‐based end‐of‐life care were more likely to die at home compared with those receiving usual care (high‐certainty evidence); there was substantial variability among studies in admission to hospital during follow‐up (moderate‐certainty evidence). The point in a participant's illness that end‐of‐life care at home was provided varied between trials, as did the duration of care. For example, in one trial, median survival from recruitment was 11 days (Grande 1999), and in another it was 196 days (Brumley 2007). There was also considerable heterogeneity between trials regarding hospital admission while receiving home‐based end‐of‐life care. Home‐based end‐of‐life care may slightly increase patient satisfaction at one‐month follow‐up (low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain of the impact of home‐based end‐of‐life care on caregiver outcomes or on healthcare staff.

One trial, conducted in the US, examined costs in some detail and did not report differences in overall net health costs between end‐of‐life home‐based care and hospital care (Hughes 1992). A second trial, also conducted in the US, reported that the mean cost per day incurred by those participants receiving home‐based care was lower than for those receiving standard care (very low‐certainty evidence) (Brumley 2007). None of the studies reported on costs incurred by the participant or the caregiver.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included trials were conducted between 1992 and 2007; all were conducted in high‐income countries, with two in the US, one in the UK, and one in Norway. Three trials recruited 694 participants, and one cluster randomised trial recruited 434 participants. About 25% of participants lived alone. Participant survival times varied, indicating that they were recruited at different stages of their illnesses. In Grande 1999, participants had a median survival of 11 days from referral; participants recruited to the cluster trial in Norway had an estimated life expectancy of between two and nine months (Jordhøy 2000); and participants in one trial conducted in the US had a life expectancy of 12 months or less (Brumley 2007). Admissions to hospital also varied, which may be explained by the different healthcare systems, the configuration of existing community‐based services, the stage of illness and support provided to caregivers. Despite these differences, the evidence does support the implementation of home‐based end‐of‐life care programmes with access to 24‐hour care to support more people dying at home in high‐income countries.

Certainty of the evidence

The low number of small, randomised trials and lack of certainty of the evidence reflects the difficulties in conducting research in this area.

Potential biases in the review process

Only one review author reviewed the abstracts and applied the inclusion criteria to produce a long list of potentially eligible studies, it is possible but unlikely that studies were missed as two review authors independently applied eligibility criteria and assessed these studies for inclusion, extracted data and evaluated the scientific quality. We identified only one abstract of an ongoing trial (Stern 2006), and did not identify subsequent publication of these trial results. We did not identify any unpublished randomised data to include in this review. It is possible that the exclusion of unpublished studies might have introduced a risk publication bias, but given the difficulties in conducting research in this area this is unlikely to be a problem.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Smeenk 1998 systematically reviews home‐care programmes for people with incurable cancer compared to routinely available home care. This review excluded studies in which the control group received hospital care. In addition to noting the poor descriptions of the care involved in the intervention and control groups, Smeenk 1998 reported that the evidence supporting home‐care programmes was inconclusive. Zimmermann 2008 published a systematic review of specialised palliative care across a range of settings. They also concluded that methodological limitations contributed to a weak evidence base. Luckett 2013 assessed to what extent home nursing increased the likelihood of dying at home, concluding that the existing evidence precluded definitive recommendations. Miranda 2019 reviewed the evidence for home palliative care for people with dementia, likewise, concluding that the evidence was of low quality.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Unless major changes are made to the way services are provided, a growing ageing population and continuing demand for hospital‐based services will have an impact on the number of people dying in hospital (ELCC 2016; Gomes 2008). The evidence included in this review supports the use of home‐based end‐of‐life care programmes for increasing the number of people who die at home, although the numbers of people being admitted to hospital and the time spent at home while receiving end‐of‐life care should be monitored, to ensure that the required support is available. The organisation of home‐based end‐of‐life care will depend on the configuration of existing services, as caring for more patients at home will place additional demands on primary care. For example, the trial in Norway concluded that a system with restrictive night services and staff with no specific training in palliative care limited the number of patients who could be admitted. The authors suggest that a more advanced and extensive home‐based end‐of‐life care service may be necessary to substantially increase the proportion of days in home cares (Jordhøy 2000). The model of end‐of‐life care evaluated by Grande 1999 restricted end‐of‐life care to two weeks. All trials included in this review highlighted the need for access to 24‐hour care. There are examples of innovative models of care, several of which use a whole‐systems approach. In the UK, there are the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service and the Marie Curie Delivering Choice Programme (Noble 2015). The latter programme includes community service models that provide 24‐hour care and aim to strengthen co‐ordination between services (Agelopoulos 2009). In Italy, a quantitative study of hospital‐based home palliative‐care programme implemented between 2009 and 2011 provided care to more than 11,000 patients, with 75% of deaths occurring at home by its final year (Masella 2015). The authors also noted that the involvement of primary healthcare workers was essential for the success of their programme. An overview of systematic reviews about common components of in‐home end‐of‐life care programmes identified 30 unique components, spanning services offered, availability, characteristics of the care model, linkages to other resources and process interventions (Bainbridge 2016). Two‐thirds of the programmes reported hospital linkage and multidisciplinary teams.

Implications for research.

Given that the mean age at death is predicted to increase and that those dying are likely to have increasingly complex comorbidities (Gomes 2008), attention should be given to testing different models of end‐of‐life home‐based care. A patient preference design comparing different models could be considered, but may limit patient numbers and further reduce the generalisability of the results (Grande 1999). Interventions that provide a rapid response or intermittent hospice at home could also be an alternative (Harrold 2014), and might provide additional support to carers of those receiving end‐of‐life care at home (NICE 2019). Prospective audit with robust methods of data collection to document patients' transfer between care settings also has a place. The Methods Of Researching End of life Care (MORECare) statement provides evidence‐based guidance on how to design and conduct research on end‐of‐life care, suggesting how observational data and natural experimental methods can be integrated within more traditional randomised controlled trial designs (Higginson 2013). The difficulties of conducting randomised trials in this area are considerable due to logistical difficulties, low recruitment rates and low rates for completing questionnaires that measure outcomes (Enguidanos 2019; McWhinney 1994). Key research outcomes should include facilitating patient choice, place of death, the control of patients' symptoms, transfer to other care settings, impact on healthcare resources and caregiver burden. The burden on caregivers can be substantial, as they provide assistance with a complex range of care needs (Kleinman 2009). This burden can contribute to psychological and physical morbidity. The lack of precision around estimates of admission, or readmission, to hospital could have a major bearing on cost. This needs to be addressed, given the high costs of care at the end of life in high‐income countries.

Feedback

Feedback on review, December 2012

Summary

I would like to draw attention to some fundamental errors in this review.

The review states that "Studies comparing end of life care at home with inpatient hospital or hospice care are included". Surely, this means that in an included controlled trial, one arm is allocated to home care, and one arm to in‐hospital or in‐hospice care, at the point of admission or for early discharge during an admission. As the authors state "We used the following definition to determine if studies should be included in the review: end of life care at home is a service that provides active treatment for continuous periods of time by healthcare professionals in the patient's home for patients who would otherwise require hospital or hospice inpatient end of life care."

However, in none of the included studies is this the case. All studies are comparing different intensities of home care services, sometimes specialist inpatient units are also part of the intervention, with both intervention and control groups able to use hospital or hospice services.

This is what the articles say:

1. Grande GE:

Intervention (BMJ article):

Hospital at home provides practical home nursing care for up to 24 hours a day for up to two weeks. The service was used mainly for terminal care during the last two weeks of life. The hospital at home team consisted of six qualified nurses, two nursing auxiliaries, and a nurse coordinator.

Agency nurses were also used as required.

Both patients allocated to hospital at home and control patients could receive the standard care services provided in the district. The intervention group, however, could also receive hospital at home. Thus the trial compared hospital at home and standard care versus standard care only.

Standard care comprised care in hospital or hospice or care at home with input from general practice, district nursing, Marie Curie nursing, Macmillan nursing, evening district nursing, social services, a flexible care nursing service, or private care.

Or in their Palliative Medicine article: Both CHAH and control patients could receive the standard care provided locally. This included care in hospital or hospice, or care at home with input from GP, district nursing, Marie Curie nursing, Macmillan nursing, evening district nursing, Social Services, private care and a Flexible Care nursing service. The latter was a home nursing service, similar to Marie Curie nursing, but funded by the community NHS Trust and available to all diagnostic groups. Thus the trial compared CHAH and standard care with standard care only.

2. Hughes

"The Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital has had a Hospital‐Based Home Care (HBHC) program since 1971....(the primary aim of the study was about cost but) we also sought to compare the attributes of the Hines model of care with traditional community home care services to which control group patients could be referred."

3. Jordhoy

Conventional care is shared among the hospital departments and the community, according to diagnosis and medical needs. No well‐defined routines exist.

Palliative‐care intervention: The Palliative Medicine Unit has 12 inpatient beds, an outpatient clinic, and a consultant team that works in and out of the hospital.... We compared the palliative‐care intervention with conventional care (control).

4. Brumley

This was a randomized, controlled trial conducted at two separate managed care sites to test the replicability and the effectiveness of an In‐home Palliative Care (IHPC) program.... Each patient enrolled in the intervention arm received customary and usual standard care within individual health benefit limits in addition to the IHPC program.... Usual care consisted of standard care to meet the needs of the patients and followed Medicare guidelines for home healthcare criteria.

There would seem to me to be a major lack of understanding of what Hospital at Home means.

Could you please inform me of how the Cochrane Collaboration will address these major flaws?

Submitter agrees with default conflict of interest statement:

I work in a public hospital and in a public hospital in the home unit. I am also President of the Hospital in the Home Society of Australasia, which is a not for profit organisation.

Gideon Caplan

Occupation Director, Post Acute Care Services

Reply

Response: As we mention in the discussion of our systematic review, conducting research in the area of end of life care is complex. One of the difficulties is that the care needs and preferences for place of death1 of people approaching the end of their life can change rapidly; as a result they may require care from different groups of healthcare professionals and in different settings. In the trials included in our systematic review this resulted in a cross over between intervention and control groups (mentioned in the discussion of this systematic review). Finally, and most importantly, there are ethical concerns with not allowing people approaching the end of their life to choose where they want to be cared for. An added challenge for a systematic review in this area is that the evidence cuts across different health systems, again something we mention in the discussion: ‘the care that the control group received varied across trials and thus reflected differences in health systems and the way standard care is delivered.’

1Munday D, Petrova M, Dale J. Exploring preferences for place of death with terminally ill patients: qualitative study of experiences of general practitioners and community nurses in England. BMJ 2009; 338: b2391 doi:10.1136/bmj.b2391

Our response to the points you make for each of the included studies is below.

Feedback: 1. Grande GE:

Intervention (BMJ article):

Hospital at home provides practical home nursing care for up to 24 hours a day for up to two weeks. The service was used mainly for terminal care during the last two weeks of life. The hospital at home team consisted of six qualified nurses, two nursing auxiliaries, and a nurse coordinator. Agency nurses were also used as required.

Both patients allocated to hospital at home and control patients could receive the standard care services provided in the district. The intervention group, however, could also receive hospital at home. Thus the trial compared hospital at home and standard care versus standard care only. Standard care comprised care in hospital or hospice or care at home with input from general practice, district nursing, Marie Curie nursing, Macmillan nursing, evening district nursing, social services, a flexible care nursing service, or private care.

Or in their Palliative Medicine article:

Both CHAH and control patients could receive the standard care provided locally. This included care in hospital or hospice, or care at home with input from GP, district nursing, Marie Curie nursing, Macmillan nursing, evening district nursing, Social Services, private care and a Flexible Care nursing service. The latter was a home nursing service, similar to Marie Curie nursing, but funded by the community NHS Trust and available to all diagnostic groups. Thus the trial compared CHAH and standard care with standard care only.

Response: People receiving specialist end of life home care could also be admitted to inpatient care, hospice care and access primary care services (SS, SS, BW).

Feedback: 2. Hughes

"The Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital has had a Hospital‐Based Home Care (HBHC) program since 1971....(the primary aim of the study was about cost but) we also sought to compare the attributes of the Hines model of care with traditional community home care services to which control group patients could be referred."

Response: The control group also received inpatient care (SS, SS, BW).

Feedback: 3. Jordhoy

Conventional care is shared among the hospital departments and the community, according to diagnosis and medical needs. No well‐defined routines exist.

Palliative‐care intervention: The Palliative Medicine Unit has 12 inpatient beds, an outpatient clinic, and a consultant team that works in and out of the hospital.... We compared the palliative‐care intervention with conventional care (control).

Response: We gave additional detail in the included studies table: A hospital‐based intervention co‐ordinated by the Palliative Medicine Unit with community outreach. The intervention had been working for 2 years and 8 months. The Palliative Medicine Unit provided supervision and advice and joined visits at home. The community nursing office determined the type and amount of home care and home nursing offered. The care was multidisciplinary, involving a palliative care team, community team, patients and families. Specialist palliative care nurses provided care in the home with a family physician and palliative care consultants (n = 3). Physiotherapy, nutrition and social care were available as was access to a priest. 24‐hour care was limited; the smallest urban district had no access to 24‐hour care.

In addition we asked the authors for additional data and to clarify that their trial was eligible for the review (SS, SS, BW).

Feedback: 4. Brumley

This was a randomized, controlled trial conducted at two separate managed care sites to test the replicability and the effectiveness of an In‐home Palliative Care (IHPC) program.... Each patient enrolled in the intervention arm received customary and usual standard care within individual health benefit limits in addition to the IHPC program.... Usual care consisted of standard care to meet the needs of the patients and followed Medicare guidelines for home healthcare criteria.

Response: The difference between the intervention and the control group was that the control group did not receive specialised 24 hour ‘in home palliative care’ while those allocated to the intervention had access to it until death or transfer to a hospice (see included studies table) (SS, SS, BW).

Feedback: Could you please inform me of how the Cochrane Collaboration will address these major flaws?

Response: The feedback was submitted to the EPOC feedback editor, who then passed it on to the authors and the EPOC managing editor. The authors drafted a response, which was approved by the feedback editor and an additional EPOC editor.

Contributors

Sasha Shepperd

Bee Wee

Sharon E Straus

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 July 2021 | Amended | Text relating to the searching for another review was added to published notes field of this review by mistake. This error was corrected. |

History

Review first published: Issue 7, 2011

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 March 2020 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We included no new studies in this update. |

| 20 March 2020 | New search has been performed | We included no new studies in this update and restricted the study design to randomised trials. We reduced the number of outcomes to seven by merging 'family or caregiver assessment of patient's symptoms' with 'patient health outcomes'; removed delay in care and participant's preferred place of death as no data have been reported for these outcomes in each version of the review; merged 'family or caregiver unable to continue caring' with 'caregiver outcomes' and added staff views as an outcome to the 'Summary of findings' table. We removed the outcome mortality as it does not link to the aims of the review, it was previously included as an outcome when the results for admission avoidance, early discharge and end‐of‐life care hospital at home interventions were reported in one review. In previous versions of the review, we adjusted the data reported by Jordhøy for a cluster randomised trial, using an estimate of an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 that we obtained from the Aberdeen database of ICCs (www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/research/research‐tools/study‐design). In this version of the review, we reported the number of events and participants for the outcomes reported in the review. We updated the references. |

| 23 October 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We included no new studies in this update. |

| 22 April 2015 | New search has been performed | We updated searches. We revised the methods to align with current Cochrane guidance. |

| 18 January 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback submitted; feedback and responses included in "Feedback section". |

Acknowledgements

Professor Steve Iliffe assisted with data extraction for one of the trials (Hughes 1992). Mike Bennett, Luciana Ballini, Camilla Zimmermann, Álvaro Sanz, Andy Oxman and Craig Ramsay provided peer review comments on previous versions of this review. We also acknowledge the contribution from EPOC editorial staff: Paul Miller (Information Specialist), Chris Cooper (Managing Editor) and Denise O'Connor (Contact Editor).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

Searched 18 March 2020

MEDLINE (Ovid MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE)

| 1 | home care services, hospital‐based/ |

| 2 | home care services/ and (hospital* or unit? or ward? or institution*).ti,ab,kf. |

| 3 | home health nursing/ |

| 4 | (hospital* adj2 home).ti,ab,kf. |

| 5 | virtual ward?.ti,ab,kf. |

| 6 | ((early or earlier or supported or assisted) adj2 discharge?).ti,ab,kf. |

| 7 | ((hospice* or terminal or end of life or palliative) adj3 home).ti,ab,kf. |

| 8 | or/1‐7 |

| 9 | exp randomized controlled trial/ |

| 10 | controlled clinical trial.pt. |

| 11 | randomi#ed.ti,ab. |

| 12 | placebo.ab. |

| 13 | randomly.ti,ab. |

| 14 | Clinical Trials as topic.sh. |

| 15 | trial.ti. |

| 16 | or/9‐15 |

| 17 | exp animals/ not humans/ |

| 18 | 16 not 17 |

| 19 | 8 and 18 |

| 20 | (2015* or 2016* or 2017* or 2018* or 2019* or 2020*).dt,dp,ed,ep,yr. |

| 21 | 19 and 20 |

Embase

| 1 | exp *home care/ |

| 2 | (hospital* or unit? or ward? or institution*).ti,ab,kw. |

| 3 | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | (hospital* adj2 home).ti,ab,kw. |

| 5 | virtual ward?.ti,ab,kw. |

| 6 | ((early or earlier or supported or assisted) adj2 discharge?).ti,ab,kw. |

| 7 | ((hospice* or terminal or end of life or palliative) adj3 home).ti,ab,kw. |

| 8 | or/3‐7 |

| 9 | random*.ti,ab. |

| 10 | factorial*.ti,ab. |

| 11 | (crossover* or cross over*).ti,ab. |

| 12 | ((doubl* or singl*) adj blind*).ti,ab. |

| 13 | (assign* or allocat* or volunteer* or placebo*).ti,ab. |

| 14 | crossover procedure/ |

| 15 | single blind procedure/ |

| 16 | randomized controlled trial/ |

| 17 | double blind procedure/ |

| 18 | or/9‐17 |

| 19 | exp animal/ not human/ |

| 20 | 18 not 19 |

| 21 | 8 and 20 |

| 22 | limit 21 to yr="2015 ‐Current" |

| 23 | limit 22 to embase |

CINAHL

| S1 | (MH "Home Health Care+") |

| S2 | (hospital* or unit? or ward? or institution*) |

| S3 | S1 AND S2 |

| S4 | TI (hospital* N2 home) OR AB (hospital* N2 home) |

| S5 | TI (virtual ward?) OR AB (virtual ward?) |

| S6 | TI ((early or earlier or supported or assisted) N2 discharge?) OR AB ((early or earlier or supported or assisted) N2 discharge?) |

| S7 | TI ((hospice* or terminal or end of life or palliative) N3 home) OR AB ((hospice* or terminal or end of life or palliative) N3 home) |

| S8 | S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 |

| S9 | PT randomized controlled trial |

| S10 | PT clinical trial |

| S11 | TI ( randomis* or randomiz* or randomly) OR AB ( randomis* or randomiz* or randomly) |

| S12 | (MH "Clinical Trials+") |

| S13 | (MH "Random Assignment") |

| S14 | S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 |

| S15 | S8 AND S14 |

| S16 | S15 |

| S17 | S16 Limiters ‐ Published Date: 20150101‐20201231 |

CENTRAL search terms

| #1 | [mh "home care services, hospital‐based"] |

| #2 | [mh ^"home care services"] and (hospital* or unit? or ward? or institution*):ti,ab,kw |

| #3 | [mh "home health nursing"] |

| #4 | (hospital* near/2 home):ti,ab,kw |

| #5 | (virtual next ward?):ti,ab,kw |

| #6 | ((early or earlier or supported or assisted) next discharge*):ti,ab,kw |

| #7 | ((hospice* or terminal* or "end of life" or palliative) near/3 home*):ti,ab,kw |

| #8 | {or #1‐#7} |

| #9 | {or #1‐#7} with Cochrane Library publication date Between Jan 2015 and Dec 2020 |

ClinicalTrials.gov

| Interventional Studies | (intervention/treatment) early supported discharge OR "hospital at home" OR virtual ward |

| Interventional Studies | (title) home AND hospital |

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)

| hospital at home |

| early supported discharge |

| virtual ward* |

| TITLE (advanced search): hospital AND home |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Place of death.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Dying at home | 2 | 539 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.12, 1.52] |

| 1.2 Dying at home, in hospital or a nursing home | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 1.3 Number at home for some or all the last 2 weeks | 1 | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 2. Unplanned admissions to hospital.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Admitted to hospital | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Participant health outcomes, including control of symptoms.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Functional status | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 3.2 Psychological well‐being | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 3.3 Cognitive status | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 3.4 Patient satisfaction | 2 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 3.5 Caregivers' ratings of symptoms | 1 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 3.6 General practitioners' ratings of symptoms | 1 | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 4. Caregiver outcomes.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 Caregiver outcomes | 2 | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 5. Staff views on the provision of services.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 District nurse and general practitioner views | 1 | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 6. Health service resource use and cost.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 Health service use | 3 | Other data | No numeric data | |

| 6.2 Cost | 2 | Other data | No numeric data |

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Health service resource use and cost, Outcome 2: Cost

| Cost | ||

| Study | Outcomes | Notes |

| Brumley 2007 |

Controlling for survival, age, severity of illness and primary disease, adjusted mean cost (SD) Intervention group: USD 12,670 (12,523); control group: USD 20,222 (30,026) Mean cost per day incurred by those on intervention arm (USD 95.30) was significantly lower than that of comparator group (USD 212.80) (t = ‐2.417; P = 0.02) |

Service costs were calculated using actual costs for contracted medical services in Colorado and proxy cost estimates for all services provided within the health maintenance organisation

(HMO) as services within the HMO were not billed separately. Costs were based on figures from 2002. Hospitalisation and emergency department cost estimates were calculated using aggregated data from more than 500,000 HMO patient records and include ancillary services such as laboratory and radiology. Costs of physician clinic visits included nurse and clerk expenses. Home health and palliative care visits were calculated using mean time spent on each visit and multiplying that by the cost for each discipline's reimbursement rate. Proxy costs generated for hospital days and emergency department visits were significantly lower than the actual costs received from contracted providers. Total cost variable was constructed by aggregating costs for physician visits, emergency department visits, hospital days, skilled nursing facility days and home health or palliative days accumulated from the point of study enrolment until the end of the study period or death. |

| Hughes 1992 |