Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who require urgent initiation of dialysis but without having a permanent dialysis access have traditionally commenced haemodialysis (HD) using a central venous catheter (CVC). However, several studies have reported that urgent initiation of peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a viable alternative option for such patients.

Objectives

This review aimed to examine the benefits and harms of urgent‐start PD compared to HD initiated using a CVC in adults and children with CKD requiring long‐term kidney replacement therapy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 25 May 2020 for randomised controlled trials through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

For non‐randomised controlled trials, MEDLINE (OVID) (1946 to 11 February 2020) and EMBASE (OVID) (1980 to 11 February 2020) were searched.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs and non‐RCTs comparing urgent‐start PD to HD initiated using a CVC.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors extracted data and assessed the quality of studies independently. Additional information was obtained from the primary investigators. The estimates of effect were analysed using random‐effects model and results were presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The GRADE framework was used to make judgments regarding certainty of the evidence for each outcome.

Main results

Overall, seven observational studies (991 participants) were included: three prospective cohort studies and four retrospective cohort studies. All the outcomes except one (bacteraemia) were graded as very low certainty of evidence given that all included studies were observational studies and reported few events resulting in imprecision, and inconsistent findings. Urgent‐start PD may reduce the incidence of catheter‐related bacteraemia compared with HD initiated with a CVC (2 studies, 301 participants: RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.41; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence), which translated into 131 fewer bacteraemia episodes per 1000 (95% CI 89 to 145 fewer). Urgent‐start PD has uncertain effects on peritonitis risk (2 studies, 301 participants: RR 1.78, 95% CI 0.23 to 13.62; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence), exit‐site/tunnel infection (1 study, 419 participants: RR 3.99, 95% CI 1.2 to 12.05; very low certainty evidence), exit‐site bleeding (1 study, 178 participants: RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.33; very low certainty evidence), catheter malfunction (2 studies; 597 participants: RR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.07 to 0.91; I2 = 66%; very low certainty evidence), catheter re‐adjustment (2 studies, 225 participants: RR: 0.13; 95% CI 0.00 to 18.61; I2 = 92%; very low certainty evidence), technique survival (1 study, 123 participants: RR: 1.18, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.61; very low certainty evidence), or patient survival (5 studies, 820 participants; RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.07; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence) compared with HD initiated using a CVC. Two studies using different methods of measurements for hospitalisation reported that hospitalisation was similar although one study reported higher hospitalisation rates in HD initiated using a catheter compared with urgent‐start PD.

Authors' conclusions

Compared with HD initiated using a CVC, urgent‐start PD may reduce the risk of bacteraemia and had uncertain effects on other complications of dialysis and technique and patient survival. In summary, there are very few studies directly comparing the outcomes of urgent‐start PD and HD initiated using a CVC for patients with CKD who need to commence dialysis urgently. This evidence gap needs to be addressed in future studies.

Plain language summary

Urgent‐start peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis for people with chronic kidney disease

What is the issue?

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an established form of kidney replacement therapy using the patient’s own peritoneal membrane (inner lining of the abdomen) as a filter for dialysis. Traditionally, initiation of PD has been delayed for 2 weeks after the placement of a PD catheter to allow time for wound healing. However, some patients require dialysis urgently and are unable to wait for 2 weeks. In order to avoid an additional procedure of insertion of a catheter for haemodialysis (HD) in PD patients, there have been studies reporting the successful start of PD urgently within 2 weeks of PD catheter insertion. The review compared the outcomes of PD patients who commenced PD urgently with those HD patients who commenced dialysis using a catheter.

What did we do?

We performed a systemic review to look at the benefits and harms of patients with chronic kidney disease who commenced urgent PD (usually within 2 weeks of PD catheter insertion) with those who underwent HD using a dialysis catheter.

What did we find?

We identified 7 studies (991 participants) comparing the risks and benefits of urgent initiation of peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis using a catheter. We found that patients who underwent urgent PD may have a lower risk of blood‐stream infection (presence of bacteria in the blood) compared with patients who underwent HD using a dialysis catheter. The differences in the risks of having other infectious complications and mechanical complications of a dialysis catheter, or sustainability on the original type of dialysis treatment (PD or HD) between the two modes of dialysis were uncertain.

Conclusions

Patients on PD may have a lower risk of blood stream infection compared with those on HD using a catheter. However, it is unclear whether there are any differences in other infection‐related or catheter‐related complications, ability to remain on the same type of dialysis treatment, and patient survival between urgent PD and HD using a catheter.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Urgent‐start peritoneal dialysis versus haemodialysis initiated with a catheter for patients with chronic kidney disease | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD Settings: community Intervention: USPD Comparison: HD initiated with a central venous catheter | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with USHD | Risk with USPD | ||||

|

Bacteraemia up to 6 months |

151 per 1,000 |

20 per 1,000 (6 to 62) |

RR 0.13 (0.04 to 0.41) |

301 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1 |

|

Peritonitis up to 6 months |

7 per 1,000 |

13 per 1,000 (2 to 98) |

RR 1.78 (0.23 to 13.62) |

301 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| Exit‐site or tunnel infection | 18 per 1,000 |

71 per 1,000 (24 to 216) |

RR 3.99 (1.32 to 12.05) |

419 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| Exit‐site bleeding | 37 per 1,000 |

4 per 1,000 (0 to 85) |

RR 0.12 (0.01 to 2.33) |

178 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| Catheter malfunction | 151 per 1,000 |

39 per 1,000 (11 to 137) |

RR 0.26 (0.07 to 0.91) |

597 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 |

|

Catheter re‐adjustment up to 60 months |

373 per 1,000 |

48 per 1,000 (0 to 1,000) |

RR 0.13 (0.00 to 18.61) |

225 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 |

|

Technique survival up to 6 months |

526 per 1,000 |

621 per 1,000 (458 to 847) |

RR 1.18 (0.87 to 1.61) |

123 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| Home dialysis | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies | ABSENT |

|

Death (any cause) up to 24 months |

204 per 1000 |

139 per 1,000 (90 to 218) |

RR 0.68 (0.44 to 1.07) |

820 (5) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

|

Hospitalisation up to 6 months |

579 per 1,000 |

683 per 1,000 (515 to 897) |

RR 1.18 (0.89 to 1.55) |

123 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 |

| *The risk in the USPD group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; HD: haemodialysis; USHD: urgent‐start HD; USPD: urgent‐start peritoneal dialysis | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1downgraded for observational studies

2 downgraded for observational studies, imprecision due to small number of events

3 downgraded for observational studies and imprecision due to small number of events, and inconsistency

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) requiring long‐term kidney replacement therapy (KRT) is a common and growing problem affecting over two million people worldwide (AIHW 2016; Couser 2011; Gilg 2016). Even though one of the main predictors of better patient survival is having an established dialysis access at the time of dialysis commencement (Pisoni 2009; Ravani 2013), a large proportion of patients commence treatment via a central venous catheter (CVC) (40% to 80%) (ANZDATA 2015; Moist 2014; Rao 2016; USRDS 2015). In part, this is due to many patients (20% to 30%) presenting ‘late’ to a nephrology service that necessitates commencement of dialysis urgently or in an unplanned manner (Foote 2014). In other cases, it could be the consequence of health system failure such as a lack of an established responsive dialysis access programme with limited access to a surgical or interventional nephrology service. In this setting, most patients start haemodialysis (HD) via a CVC, which then places them at a heightened risk of infection, prolonged hospitalisation, mortality (Perl 2011) as well as future complications from central vascular stenosis (Shingarev 2012). A recent systematic review, that included a total of 586,337 patients, identified that the use of a CVC led to the highest risk of death, fatal infections, and cardiovascular events, compared with other types of vascular access (Ravani 2013). Moreover, these patients were more likely to remain on facility‐based HD (Morton 2010) rather than to transition to home‐based dialysis program such as peritoneal dialysis (PD), which confers an initial survival advantage (Kumar 2014; Masterson 2008).

PD is a type of home‐based dialysis that uses the peritoneum in a person’s abdomen as the membrane through which fluid and dissolved substances are exchanged with the blood. PD solution is introduced through a PD catheter, which is placed in the lower abdomen permanently (Mehrotra 2016). PD has many benefits at the patient‐level, including initial survival advantage compared to HD, easier mastery of the technique, better preservation of residual kidney function, better patient‐level satisfaction, and preservation of vascular access for future use (Tokgoz 2009). PD can also offer annual cost savings of up to 40% compared to facility HD (KHA 2012; KHA 2016). However, uptake of PD remains relatively low and only accounts for approximately 11% of the global dialysis population (Jain 2012). The decision‐making process which leads to undertaking a home therapy is complex and can be influenced by social circumstances, education, and the capacity to undertake training (Machowska 2016). However, one of the contributors to limited growth in PD may relate to the reluctance to utilise PD as the dialysis modality of choice without established dialysis access, which is driven by the practice to delay treatment by at least two weeks from the time of PD catheter insertion to lower the risk of catheter‐related complications, such as leaks (Dombros 2005; Figueiredo 2010). However, these practices are guided by recommendations based on the weak level of evidence (Dombros 2005; Figueiredo 2010).

More recently, urgent‐start PD has been promoted as an alternative form of urgent, unplanned dialysis treatment, which has been reported to be effective and potentially has fewer adverse consequences based on findings from observational studies (Casaretto 2012; Ghaffari 2012; Jo 2007; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008; See 2017).

Description of the intervention

Traditionally, new CKD patients who require dialysis urgently but do not have a permanent functional dialysis access are subjected to HD via central venous dialysis catheter (CVC). In order to avoid the CVC and its related complications, urgent‐start PD, has been introduced as an alternative form of KRT for CKD patients who require dialysis urgently or in an unplanned fashion. Currently, there is no universally agreed definition regarding the duration between PD catheter insertion and commencement that qualifies as urgent‐start PD. The International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) recommends the use of PD catheters at least two weeks after its insertion (Figueiredo 2010). The duration between PD catheter insertion and commencement (Ranganathan 2017), fill volume and insertion technique may have an impact on outcomes observed following urgent‐start PD and therefore will be considered as part of subgroup analyses in the present review.

How the intervention might work

Urgent‐start PD is initiated with low fill volumes in the supine position using a cycler to minimise the risk of peri‐catheter leak. Treatment can be delivered in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Why it is important to do this review

The vast majority of evidence relating to outcomes from urgent‐start PD has been generated from single‐centre observational studies with relatively small patient numbers (Casaretto 2012; Ghaffari 2012; Jo 2007; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008), which has resulted in ad hoc implementation rather than a ‘standard’ care across the world.

Objectives

This review aimed to look at the benefits and harms of urgent‐start PD (defined as initiation of PD within 2 weeks of catheter insertion) compared to HD (defined as initiation of HD using a CVC) in adults and children with CKD requiring long‐term KRT.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods), and non‐RCTs comparing urgent‐start PD to HD treatments via CVC.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Participants included in this review were both adults and children with CKD, who require dialysis treatment. Participants had a PD catheter inserted to undergo PD or a CVC for HD.

Exclusion criteria

The review did not include data obtained from patients with acute kidney injury.

Types of interventions

Studies comparing urgent‐start PD and HD via CVC were included in this review.

Intervention: patients commenced on urgent‐start PD, defined as initiation of PD therapy within two weeks of catheter placement.

Comparator: patients commenced on urgent‐start HD, defined as initiation of HD therapy using a CVC (cuffed and uncuffed at commencement).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Catheter‐related infectious complications occurring within 30 days (early complication) and 90 days (late complication)

Bacteraemia (defined as blood culture positive for bacteria) after commencement of dialysis (proportion of patients developing bacteraemia)

Peritonitis as defined by the ISPD guidelines (Li 2010) after commencement of dialysis (proportion of patients developing peritonitis)

Exit site or tunnel tract infection in PD patients was defined by the ISPD guidelines (Li 2010) after commencement of dialysis and CVC exit‐site infection was defined as presence of erythema, induration, and/or tenderness within 2 cm of the catheter exit site; may be associated with fever or purulent drainage from the exit site, with or without concomitant bloodstream infection (Mermel 2009) and tunnel infection, defined as tenderness, erythema, and/or induration > 2 cm from the catheter exit site, along the subcutaneous tract of a tunnelled catheter, with or without concomitant bloodstream infection (Mermel 2009). (proportion of patients developing exit site or tunnel tract infections)

-

Catheter‐related non‐infectious complications occurring within 30 days (early complication) and 90 days (late complication)

Exit site bleeding requiring intervention (e.g. additional application of suture) after commencement of dialysis (proportion of patients developing exit site bleeding)

Catheter malfunction, defined as catheter flow problems requiring intervention (medical (e.g. urokinase) or surgical (e.g. catheter replacement)) or malposition after commencement of dialysis (proportion of patients developing catheter malfunction)

Catheter re‐adjustment, defined as catheter malfunction requiring intervention to re‐adjust or replace the catheter (proportion of patients requiring catheter re‐adjustment procedure)

Home dialysis (proportion of patients on home dialysis (e.g. PD or home HD)).

Secondary outcomes

Technique survival (number of patients remaining on the initial mode of KRT at the end of study)

Death (any cause)

Hospitalisation (average days spent in hospital, episodes of hospitalisation, or number requiring hospitalisation)

Pain/discomfort related to dialysis therapy

Adverse effects

Quality of life

Cost of dialysis treatment

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 25 May 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Hand searching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of hand searched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

For non‐RCTs, MEDLINE (OVID) (1946 ‐ 11 February 2020) and EMBASE (OVID) (1980 ‐ 11 February 2020), Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov (up to 14 February 2019) were searched.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed and retrieved abstracts and, if necessary, the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions, these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Randomised controlled trials

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool for RCTs (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Non‐randomised controlled trials

The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) (www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf) for assessing quality of non‐randomised studies were used.

-

For case control studies the following items were evaluated.

Selection (adequacy of definition, representativeness of the cases, selection of controls, definition of controls)

Comparability (comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis)

Exposure (ascertainment of exposure, same method of ascertainment for cases and controls, non‐response rate).

-

For cohort studies the following items were evaluated.

Selection (representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of the non‐exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure, demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study)

Comparability (comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis)

Outcome (assessment of outcome, adequacy of follow‐up and duration of follow‐up).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. death, mechanical complications within one month of commencement of PD) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (e.g. duration of hospitalisation, duration of PD training), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. Outcomes from RCTs and non‐RCTs were reported separately.

Unit of analysis issues

If the review included cluster RCTs, the unit of analysis was at the same level as the allocation, using a summary measurements from each cluster. All data were collected and analysed according to the type of measure (e.g. hazard ratios, odds ratio).

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing the corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients, as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol populations were carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were evaluated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values was as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a Cl for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

If possible, funnel plots were used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We combined data of studies having similar designs and interventions and reporting similar outcomes. A random effects model was used to measure treatment effects for dichotomous outcomes. In sensitivity analyses, adjusted effect estimates and their standard errors were used for pooling studies in meta‐analyses and the generic inverse‐variance method was used whenever adjusted data were available.

Risks of bias of included studies were assessed using the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS). Certainty of evidence was evaluated using GRADE recommendations by starting at “low certainty” for observational studies and upgrading based on a large magnitude of effect, lack of concern about confounders or a dose‐response gradient and downgrading based on imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency, and reporting bias (GRADE 2008).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants, interventions and study quality including method of PD catheter insertion). Heterogeneity among participants could have been related to age and renal pathology (e.g. children versus adults). Heterogeneity in treatments could have been related to prior agent(s) used and the agent, dose, and duration of therapy (e.g. initial fill volume). Therefore, subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate the source of heterogeneity according to:

-

Participants

Adult versus paediatric patients

Incident versus prevalent patients

-

Setting

Single‐centre versus multi‐centre

-

Type of treatment utilised

According to initial fill volume

Days to PD commencement (e.g. within 24 hours versus 7 days)

Methodological quality

Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques, as they were likely to be different for the various agents used. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared to no treatment or to another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We planned to present the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

-

Catheter‐related infectious complications within 30 and 90 days of commencement of dialysis

Bacteraemia

Peritonitis

Exit‐site or tunnel infections

-

Catheter‐related non‐infectious complications within 30 and 90 days of commencement

Exit‐site bleeding

Catheter malfunction

Catheter re‐adjustment

Technique survival

Home dialysis

Death (any cause)

Hospitalisation

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

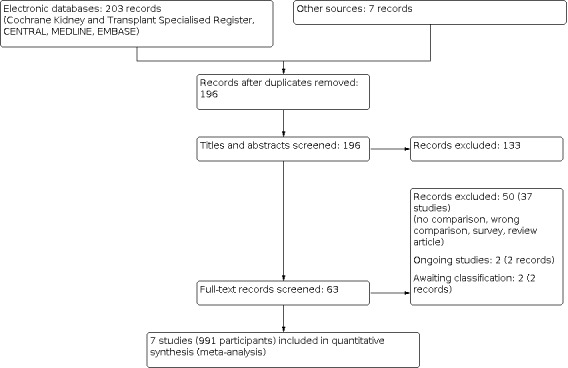

An electronic search (last search date for RCTs: 25 May 2020; non‐RCTs: 11 February 2020) identified 210 potentially relevant reports in total. After removing duplicates and screening through 196 titles and abstracts, 133 reports were excluded. Full text review was conducted of the remaining 63 records (43 studies). Seven studies (9 records) were included, 37 studies (50 records) and were excluded. Two ongoing studies (2 records) and two studies waiting classification (2 records) will be assessed in a future update of this review (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Seven studies (991 participants) were included in the review. Studies were conducted in the USA (Bhalla 2017; Ghaffari 2015; Wang 2017), China (Jin 2016), Brazil (Brabo 2018), France (Lobbedez 2008), and Germany (Koch 2012). There were four single‐centre retrospective cohort studies and three single‐centre prospective cohort studies (Table 2). Six out of seven studies compared the clinical outcomes between urgent‐start PD and HD using a CVC and one study (Brabo 2018) compared the cost of dialysis between these two modalities.

1. Description of studies included in the review.

| Study | Country | Study design | Time frame | No. of participants | Follow‐up duration |

| Bhalla 2017 | USA | Retrospective cohort (SC) | 2011‐2014 | 419 | Not reported |

| Brabo 2018 | Brazil | Prospective cohort (SC) | Not reported | 40 | 6 months |

| Ghaffari 2015 | USA | Prospective cohort (SC) | 2010‐2013 | 124 | Average 810 days |

| Jin 2016 | China | Retrospective cohort (SC) | 2013‐2014 | 178 | At least 30 days (up to Jan 2016) |

| Koch 2012 | Germany | Retrospective cohort (SC) | 2005‐2010 | 123 | 6 months |

| Lobbedez 2008 | France | Prospective cohort study (SC) | 2004‐2006 | 60 | Till 31 December 2006 |

| Wang 2017 | USA | Retrospective cohort (SC) | 2015‐2016 | 47 | HD: 60 months PD: 46 months |

SC: single‐centre; HD: haemodialysis; PD: peritoneal dialysis

Two studies (301 participants) examined peritonitis (Jin 2016; Koch 2012), two studies (301 participants) examined bacteraemia (Jin 2016; Koch 2012, one study (419 participants) examined the exit‐site infection (Bhalla 2017), one study (178 participants) examined the exit‐site bleeding (Jin 2016), two studies (597 participants) examined catheter malfunction (Bhalla 2017; Jin 2016), two studies (225 participants) examined catheter readjustment (Jin 2016; Wang 2017), one study (123 participants) examined technique survival (Koch 2012), five studies (820 participants) examined death (any cause) (Bhalla 2017; Brabo 2018; Jin 2016; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008), one study (123 participants) examined hospitalisation (Koch 2012), and one study (40 participants) examined the cost of dialysis (Brabo 2018).

Excluded studies

In total, 37 studies were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were: review articles; surveys; lack of control group for urgent‐start PD; wrong comparison; or wrong intervention (Figure 1).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias for all cohort studies is presented in Table 3.

2. Assessment of quality of studies.

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Evidence of quality | |||||

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non‐exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcomes not present at start | Assessment of outcome | Length of follow‐up | Adequacy of follow‐up | |||

| Bhalla 2017 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ‐‐ | 7 |

| Brabo 2018 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | * | * | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | * | * | 4 |

| Ghaffari 2015 | * | * | ‐‐ | * | ‐ | ‐‐ | * | * | 5 |

| Jin 2016 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ‐‐ | 7 |

| Koch 2012 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ‐‐ | 7 |

| Lobbedez 2008 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ‐‐ | 7 |

| Wang 2017 | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | * | * | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | * | ‐‐ | 3 |

Allocation of star was based on NEWCASTLE ‐ OTTAWA Quality Assessment Scale (www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nosgen.pdf)

Selection

Four included cohort studies (Bhalla 2017; Jin 2016; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008) met all criteria of the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for selection including representativeness of exposed cohort, selection of non‐exposed cohort, ascertainment of exposure and outcomes of interest was not presented at the start of the study. The representativeness of cohort was unable to be assessed in two studies (Brabo 2018; Wang 2017), selection of non‐exposed cohort was unable to be assessed in two studies (Brabo 2018; Wang 2017) and ascertainment of exposure was unable to be assessed in two studies (Brabo 2018; Ghaffari 2015).

Comparability of groups of study

Four cohort studies (Bhalla 2017; Jin 2016; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008) met the comparability criteria of NOS. There was insufficient information to assess the comparability between groups for two included studies (Brabo 2018; Ghaffari 2015). One study was assessed as having a high risk of bias due to differences in baseline characteristics between PD and HD groups (Wang 2017).

Outcome

Three cohort studies (Bhalla 2017; Jin 2016; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008) met the two domains of outcome including assessment of outcome and length of follow‐up and another two studies (Brabo 2018; Ghaffari 2015) met the criteria of length of follow‐up and adequacy of follow‐up.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Infectious complications

Bacteraemia

Urgent‐start PD may reduce the incidence of catheter‐related bacteraemia compared with HD using CVC (Analysis 1.1 (2 studies, 301 participants): RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.41; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence). This translated into 131 fewer bacteraemia episodes per 1000 (89 to 145 fewer). It was graded as low certainty of evidence. The evidence was downgraded due to the fact that included studies were observational studies (Table 1). In a sensitivity analysis that included adjusted data, a similar result was observed (Analysis 1.2 (2 studies, 301 participants): RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.42, I2 = 0%). Ghaffari 2015 also reported a higher risk of catheter‐related bacteraemia in HD initiated with a CVC compared with urgent‐start PD (adjusted incidence risk ratio (IRR) 4.32; 95% CI 1.48 to 12.62).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 1: Bacteraemia

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 2: Bacteraemia (adjusted data)

Peritonitis

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD increases the risk of peritonitis compared to HD using a CVC, (Analysis 1.3 (2 studies, 301 participants): RR 1.78, 95% CI 0.23 to 13.62; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence was graded as very low given non‐RCT designs and imprecision.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 3: Peritonitis

Exit‐site or tunnel infection

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD increases the incidence of exit‐site/tunnel infection (Analysis 1.4 (1 study, 419 participants): RR 3.99, 95% CI 1.32 to 12.05; very low certainty evidence) compared with HD initiated using a catheter. The remaining included studies did not report exit‐site/tunnel infection.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 4: Exit‐site or tunnel infection

Non‐infectious complications

Exit‐site bleeding

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD reduces the risk of exit‐site bleeding (Analysis 1.5 (1 study, 178 participants): RR 0.12, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.33; very low certainty evidence) compared with HD initiated using a catheter. The remaining included studies did not report exit‐site bleeding

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 5: Exit‐site bleeding

Catheter malfunction

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD reduces catheter malfunction compared with HD using a CVC (Analysis 1.6 (2 studies; 597 participants): RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.91; I2 = 66%; very low certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence was graded as very low as both studies were observational, imprecise, and inconsistent. The subgroup analysis was unable to be meaningfully performed given that a limited number of included studies.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 6: Catheter malfunction

Catheter re‐adjustment

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD reduces the risk of catheter re‐adjustment as compared with HD via CVC (Analysis 1.7 (2 studies, 225 participants): RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.00 to 18.61; I2 = 92%; very low certainty evidence). Further sub‐group or sensitivity analyses were unable to be performed meaningfully given that a limited number of studies reported this particular outcome.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 7: Catheter readjustment

Technique survival

It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD increases technique survival compared with HD using CVC (Analysis 1.8 (1 study, 123 participants): RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.61; very low certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence was graded as very low given that only one non‐RCT was included in the review.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 8: Technique survival

Death (any cause)

Urgent‐start PD had uncertain effect on death (any cause) compared with HD using CVC (Analysis 1.9 (5 studies, 820 participants): RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.07; I2 = 27% ; very low certainty evidence).In a sensitivity analysis that included adjusted data, a similar result was observed (Analysis 1.10 (5 studies, 820 participants); OR 0.64, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.15; I2 = 29%). Sensitivity analyses including all studies with a low risk of bias (Analysis 1.11 (4 studies, 780 participants): RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.12; I2 = 37%) or exclusion of the largest study showed similar results (Analysis 1.12 (4 studies, 401 participants): RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.17; I2 = 0%).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 9: Death (any cause)

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 10: Death (any cause): adjusted data

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 11: Death (any cause): studies with low risk of bias

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 12: Death (any cause): sensitivity analysis (excluding large studies)

Hospitalisation

Three studies (Ghaffari 2015; Koch 2012; Lobbedez 2008) reported hospitalisation. Lobbedez 2008 reported that the duration of initial hospitalisation was similar between urgent‐start PD and HD groups (median: 16.5 versus 20 days; P = 0.16). The study also reported urgent‐start PD had similar survival free of re‐hospitalisation compared to the HD group (21% versus 36% at one year; P = 0.12). Koch 2012 also reported a similar incidence of re‐hospitalisation between urgent‐start PD and HD groups (Analysis 1.13 (1 study, 123 participants): RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.55). However, Ghaffari 2015 reported a higher adjusted rate of hospitalisation in the HD group compared with the urgent‐start PD group (1 study, 124 participants; adjusted IRR 1.43; 95% CI 1.11 to 1.85). The continuous scale of measurement of effect was unable to be used given the different methods of reporting the duration of hospitalisation between studies and the limited number of studies.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD, Outcome 13: Hospitalisation

Cost of dialysis

Comparison of the cost of dialysis between urgent‐start PD and HD using a CVC was reported in Brabo 2018 who compared cost/patient over six months and reported similar cost (US$ 6091.7 ± 1289.4 versus 6209.1 ± 1600) between urgent‐start PD and HD using a CVC (Table 4).

3. Cost of urgent dialysis.

| Study | Variables | USPD | USHD |

| Brabo 2018 | Direct cost/patient over 6 months (US$) | 6092 ± 1289 | 6209 ± 1600 |

| Dialysis access | 3.7% | 9.3% | |

| Dialysis service | 80.3% | 75.2% | |

| Hospitalisation | 0% | 2.1% | |

| Laboratory tests | 1.7% | 1.6% | |

| Treatment cost for infectious complications | 1.1% | 2.5% | |

| Medication | 9.6% | 12.3% |

USHD ‐ urgent‐start haemodialysis; USPD ‐ urgent‐start peritoneal dialysis

Quality of Life

None of the included studies reported QoL.

Home dialysis

None of the included studies reported the proportion of HD patients on home HD.

Pain/discomfort related to dialysis therapy

None of the included studies reported pain/discomfort related to dialysis therapy.

Adverse events

Jin 2016 reported that there was no catheter thrombosis in PD group but 6 (7.3%) catheter thrombosis in the HD group. There was no leakage or organ rupture in either the PD or HD groups.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The present review demonstrated that, in low certainty evidence, urgent‐start PD may reduce the incidence of catheter‐related bacteraemia compared with HD using a CVC. It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD increases the risk of peritonitis compared with HD using a CVC. Urgent‐start PD has uncertain effects on exit‐site or tunnel infection, exit‐site bleeding, catheter malfunction, catheter re‐adjustment, technique or patient survival compared with HD using a CVC. There were two studies that reported a comparable risk of hospitalisation although one study reported a higher hospitalisation rate in the urgent‐start HD group compared with the urgent‐start PD group. One study comparing cost over six months reported comparable cost between the two modalities.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The present review only included observational studies (no RCTs were identified) and the majority of included studies failed to adjust for important potential confounders including age, comorbidities such as presence of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, malignancy, baseline residual kidney function, aetiology of kidney failure, and urgency for dialysis initiation in the HD group who initiated using a CVC. Few studies adjusted for confounders, and the confounders adjusted were varied across studies. In addition, the total number or included studies was very small which resulted in imprecision and further reduced the certainty of evidence. Moreover, subgroup analyses with different break‐in periods, fill volume and insertion techniques in PD patients could not be performed due to insufficient number of studies. Last but not least, this systemic review used a broad definition of urgent‐start (within 14 days of catheter insertion) and was unable to separately identify patients who required to initiate dialysis acutely after catheter insertion compared to an earlier start of planned PD.

The current review included seven observational studies. However, only three studies compared the outcomes of bacteraemia between urgent‐start PD and HD initiated with a CVC. Though certainty of evidence was graded as low to very low due to the observational study design, the results indicated HD initiated using a CVC may increase the risk of catheter‐related bacteraemia compared with urgent‐start PD. This result is biologically plausible as using a CVC for dialysis access has been well established to be independently and strongly associated with bacteraemia in HD patients (Thomson 2007).

The outcome of peritonitis was examined in two observational studies, which found that urgent‐start PD has an uncertain effect on the risk of peritonitis compared with HD group. The event rates were very low in these two studies which resulted in imprecision. The follow‐up duration was also very short in one included study that only reported peritonitis in the first 30 days of dialysis. Future studies with reasonably long follow up durations in excess of one year are required to permit more confident conclusions to be drawn. It is uncertain whether urgent‐start PD increases exit‐site/tunnel infections compared with HD using a catheter as these events were only reported in one retrospective study.

Mechanical catheter complications were examined in the present review. Urgent‐start PD has uncertain effect on catheter malfunction compared with HD initiated using a CVC. The certainty of evidence was graded as very low due to observational study design, impression due to small events, and the presence of inconsistencies between studies. Further subgroup analysis was unable to be performed given the small number of included studies. The certainty of evidence for catheter re‐adjustment was graded as very low due to observational study design the presence of considerable heterogeneity and imprecision. No strong conclusion can be drawn regarding the mechanical complications between urgent‐start PD and HD group based on the current evidence.

Technique survival was compared in one study with relatively short follow‐up durations. Similarly, death (any cause) was reported in five studies with short follow‐up durations and suboptimal methodologic quality, thereby preventing any conclusions being drawn regarding the effect of urgent‐start PD as compared with HD initiated with a catheter on technique and patient survival. In addition, patients who required emergency dialysis were routinely initiated on dialysis using a CVC rather than urgent‐start PD, which potentially could have led to selection bias with sicker patients defaulted to initiate HD using a CVC. Future well‐designed studies with adequate follow up period are needed to permit the valid comparison of technique and patient survival between the two urgent‐start modalities.

Hospitalisation was reported in three observational studies. Lobbedez 2008 reported the length of initial hospitalisation and re‐hospitalisation‐free survival, Koch 2012 reported incidence of re‐hospitalisation, and Ghaffari 2015 reported adjusted hospitalisation rate. Though the first two studies reported similar results between the two forms of urgent‐start dialysis, the last study reported a higher risk of hospitalisation in patients initiating HD using a CVC compared with urgent‐start PD patients. Meta‐analysis was unable to be performed because of the different methods of outcome reporting.

Cost of dialysis was analysed in one study conducted in Brazil (Brabo 2018) over the initial six‐month period and reported similar cost between the two urgent‐start dialysis modalities.

Quality of the evidence

All included studies were observational, of which four were single‐centre retrospective cohorts and three were single‐centre prospective cohorts. Since all included studies were non‐RCTs, the certainty of evidence was graded as low to very low. The number of studies in this area was also relatively small, which further downgraded the certainty of evidence.

The outcome bacteraemia was graded as low certainty of evidence. The evidence was downgraded due to its inclusion of only non‐RCT studies. The research provides some degree of plausible effect because the CVC enters directly into a blood vessel, thereby increasing the probability of bacteraemia in the setting of catheter‐related infection in urgent‐start HD in contrast to PD catheter which is inserted into a peritoneal cavity without direct exposure to the circulatory system.

Most of the included studies did not adjust for the potential confounders in their analyses. Most of the outcomes analysed in the present review used unadjusted data which reduced the certainty of the evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

The review process involved obtaining a comprehensive review of available publications through MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL electronic search with the help of an information specialist. Two authors performed data extraction, data analysis and assessment of study quality independently and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with additional two authors. The additional data from previous publications were obtained by contacting the corresponding authors. There were only few included studies adjusted for potential confounders, and confounders adjusted were different across studies. There might be potential bias of combined studies that adjusted for different confounders or with no adjustment at all.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first systematic review performed to compare the benefits and harms between urgent‐start PD and HD initiated using a CVC.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Compared with HD initiated with a CVC, urgent‐start PD may reduce the risk of catheter‐related bacteraemia but has uncertain effects on peritonitis, exit‐site/tunnel infection, exit‐site bleeding, catheter malfunction, catheter re‐adjustment, technique and patient survival compared with HD initiated using a CVC. Urgent‐start PD is a reasonable dialysis option for patients with chronic kidney disease who require urgent dialysis and choose to do PD.

Implications for research.

Future larger, well‐conducted studies with longer follow‐up duration are needed to compare catheter‐related infection‐free survival, technique survival and patient survival between urgent‐start PD and HD initiated using a CVC. Future studies also need to include how the study defines exit site and tunnel infections, and detail information on the type of catheter inserted (tunnel versus non‐tunnelled) and type of catheter intervention (stripping of fibrin or catheter exchange etc).

Future studies comparing patient reported outcomes (including patient satisfaction and quality of life) are needed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 February 2021 | Amended | Minor edit to abstract text |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 12, 2017 Review first published: Issue 1, 2021

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Cochrane Kidney and Transplant for their support and advice in the development of this review. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Dr Thierry Lobbedez who responded to our queries about his study.

The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Daniela Ponce (Botucatu School of Medicine, Brazil), Prof Martin Wilkie (Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK), Arsh Jain (Canada).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation (minimisation may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub‐scales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Urgent‐start PD versus urgent‐start HD.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Bacteraemia | 2 | 301 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.41] |

| 1.2 Bacteraemia (adjusted data) | 2 | Risk Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.04, 0.42] | |

| 1.3 Peritonitis | 2 | 301 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.78 [0.23, 13.62] |

| 1.4 Exit‐site or tunnel infection | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.5 Exit‐site bleeding | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.6 Catheter malfunction | 2 | 597 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.26 [0.07, 0.91] |

| 1.7 Catheter readjustment | 2 | 225 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.13 [0.00, 18.61] |

| 1.8 Technique survival | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.9 Death (any cause) | 5 | 820 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.44, 1.07] |

| 1.10 Death (any cause): adjusted data | 5 | Odds Ratio (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.36, 1.15] | |

| 1.11 Death (any cause): studies with low risk of bias | 4 | 780 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.44, 1.12] |

| 1.12 Death (any cause): sensitivity analysis (excluding large studies) | 4 | 401 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.55, 1.17] |

| 1.13 Hospitalisation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bhalla 2017.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Low risk | Patients who met criteria for USPD |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | Patients from the same population who met criteria for USHD |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Review medical records |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcomes unlikely to be presented before the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Low risk | Control matched with case based on selected criteria (details of criteria were not provided) |

| Outcome: assessment | Low risk | Medical records reviewed by three nephrologists |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

Brabo 2018.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | Drawn from the same centre |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Outcome: assessment | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Adequate follow‐up period |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Low risk | Lost to follow‐up (10%) in control group unlikely to introduce bias |

Ghaffari 2015.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Low risk | ESKD patients who required urgent‐start PD admitted to a single centre |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | ESKD patients who required HD via central line from the same hospital during the same period of study |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcomes unlikely to be present before the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Unclear risk | Reported adjusted estimates for outcomes including bacteraemia and hospitalisation, but it was unclear about the factors adjusted in analysis |

| Outcome: assessment | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Adequate follow‐up duration |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Low risk | ITT analysis |

Jin 2016.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Low risk | Study included ESKD patients without permanent dialysis access, admitted to a single hospital during a study period |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | ESKD patients who did not have vascular access and admitted to the same hospital but started on HD |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Review medical record |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcomes of interest were unlikely to present before the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Low risk | Study was adjusted for potential confounder (presence of heart failure) for composite outcome (short‐term dialysis‐related complications) |

| Outcome: assessment | Low risk | Record linkage |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Minimal 30 days, enough to examine early complications |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | High risk | High proportion of dropout from HD group (34%) |

Koch 2012.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Low risk | Unplanned patients who need dialysis urgently |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | Same cohorts |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Medical records |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Low risk | Covariables adjusted in the outcomes ‐ bacteraemia and death included age at dialysis initiation, gender, presence of heart failure, DM, malignancy, and peripheral arterial occlusive disease |

| Outcome: assessment | Low risk | Record linkage |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Adequate to examine short term outcomes |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

Lobbedez 2008.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Low risk | CKD patients who were unplanned for dialysis |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Low risk | Drawn from same community |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Extract data from medical records |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Low risk | Potential cofounder adjusted for survival was initial modified Charlson's comorbidity index |

| Outcome: assessment | Low risk | Record linkage |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Adequate follow‐up period |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to permit judgement |

Wang 2017.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Selection: representativeness of exposed cohort | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to permit judgement |

| Selection: non exposed cohort | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to permit judgement |

| Selection: ascertainment of exposure | Low risk | Medical records |

| Selection: demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study | Low risk | Outcome of interest unlikely to be present before the study |

| Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | High risk | There was significant difference between PD and HD groups in baseline data including age, presence of heart failure, hypertension, and pre‐dialysis SCr |

| Outcome: assessment | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to permit judgement |

| Outcome: follow‐up length | Low risk | Adequate follow‐up period |

| Outcome: adequacy of follow‐up | Unclear risk | Insufficient data to permit judgement |

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; DM ‐ diabetes mellitus; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis; ITT ‐ intention‐to‐treat; KPNC ‐ Kaiser Permanente North Carolina; NYHA ‐ New York Heart Association; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; SCr ‐ serum creatinine; SD ‐ standard deviation; USHD ‐ urgent‐start HD; USPD ‐ urgent‐start PD

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abdel 2018 | Wrong comparison: compare different technique of insertion in USPD patients |

| Artunc 2019 | Wrong comparison: compared USPD group and another PD group initiating dialysis with CVC first then PD |

| Bednarova 2019 | Review article |

| Bitencourt Dias 2017 | No comparison group |

| Calice‐Silva 2019 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Carsillo 2019 | No comparison group |

| Casaretto 2012 | No comparison group |

| Greenberg 2020 | Editorial |

| Hdez 2012 | Wrong comparison: unplanned PD instead of USPD initiation |

| Holm 2010 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| IDEAL‐Dialysis 2004 | Wrong intervention: early versus late initiation of dialysis |

| Javaid 2019 | Review article |

| Javaid 2019a | Review article |

| Javaid 2019b | Review article |

| Jiang 2019 | No comparison group |

| Jimenez 2019 | No comparison group |

| Kim 2018 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Li 2017 | Wrong comparison: PD group initiated dialysis emergently using HD catheter |

| Liu 2014 | Survey, not a study |

| Liu 2018 | Wrong comparison: APD versus CAPD in urgent‐start PD patients |

| Lok 2016 | Review article |

| Machowska 2017 | Wrong intervention: effect of education on the choice of dialysis in unplanned kidney failure patients |

| Naljayan 2018 | No comparison group |

| Nayak 2018 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Neumann 2018 | Wrong comparison: non‐urgent start dialysis |

| Peng 2019 | Review article |

| Salari 2018 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Salari 2018a | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Scalamogna 2019 | Wrong comparison: different insertion technique in USPD |

| Serrano 2019 | Wrong comparison: no USHD group |

| Shanmuganathan 2018 | Wrong comparison: unplanned HD initiation versus intermittent PD |

| Sloan 2019 | Not an urgent dialysis paper |

| Tannus 2017 | No comparison group |

| Tunbridge 2019 | Review article |

| Wang 2018 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Wojtaszek 2018 | Wrong comparison: USPD versus CSPD |

| Yong 2018 | Non‐urgent dialysis |

| Zang 2019 | Systemic review article |

APD ‐ automated PD; CAPD ‐ continuous ambulatory PD; CSPD ‐ conventional start PD; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; USPD ‐ urgent‐start PD

Characteristics of studies awaiting classification [ordered by study ID]

ChiCTR‐TRC‐10001132.

| Methods |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | USPD (APD) versus HD |

| Outcomes | To assess the efficiency and safety of rapid initiation of PD in unplanned dialysis patients by APD or HD |

| Notes |

TCTR20181123002.

| Methods |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | USPD versus temporarily start HD |

| Outcomes |

|

| Notes |

AKI ‐ acute kidney injury; APD ‐ automated PD; BMI ‐ body mass index; CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; CVC ‐ central venous catheter; HD ‐ haemodialysis; NYHA ‐ New York Heart Association; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial; USPD ‐ urgent‐start PD

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT02946528.

| Study name | A multi‐center clinical trial of safety and efficacy of urgent‐start peritoneal dialysis in ESRD patients |

| Methods |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | USPD versus HD |

| Outcomes |

|

| Starting date | October 2016 |

| Contact information | profnizh@126.com |

| Notes |

NCT03474367.

| Study name | Cost‐effectiveness of urgent‐start therapies hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis |

| Methods |

|

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | Unplanned PD versus HD |

| Outcomes | Cost effectiveness analysis of unplanned PD and HD |

| Starting date | April 2017 |

| Contact information | alexandrembrabo@gmail.com |

| Notes |

CKD ‐ chronic kidney disease; DBP ‐ diastolic blood pressure; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; ESRD ‐ end‐stage renal disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis; KRT ‐ kidney replacement therapy; PD ‐ peritoneal dialysis; USPD ‐ urgent‐start PD

Contributions of authors

Draft the protocol: YC, HH, CH, JC, AT, DJ

Study selection: YC, HH

Extract data from studies: YC, HH

Enter data into RevMan: YC, HH

Carry out the analysis: YC, HH, JC, AT

Interpret the analysis: YC, HH, CH, JC, AT, DJ

Draft the final review: YC, HH, CH, JC, AT, DJ

Disagreement resolution: JC, DJ

Update the review: YC

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia

DJ is supported by Practitioner Fellowship; YC is supported by Early Career Fellowship

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

Carmel Hawley has received fees from Amgen, Shire, Roche, Abbott, Bayer, Fresenius, Baxter, Gambro, Janssen‐Cilag and Genzyme in relation to consultancy, speakers' fees, education, and grants for activities unrelated to this review.

David Johnson has received consultancy fees, research grants, speaker's honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care. He has also received consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, AWAK, and travel sponsorships from Amgen. All funding was unrelated to this review. Yeoungjee Cho has received research grants and speaker’s honoraria from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care. She has also received research grants from Amgen. All funding was unrelated to this review.Htay Htay has received consultancy fees and travel sponsorships from AWAK technology, speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and research grants from Johnson & Johnson Company and Singhealth. All funding was unrelated to this review.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bhalla 2017 {published data only}

- Bhalla NM, Arora N, Darbinian JA, Zheng S. Urgent start dialysis: peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis via a central venous catheter [abstract no: TH-PO827]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;28(Abstract Suppl):314. [Google Scholar]

Brabo 2018 {published data only}

- Brabo AM, Menezes FG, Morgado F, Ponce D. A pilot study on cost evaluation of urgent start automated peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in the treatment of end-stage renal disease in Sao Paulo, Brazil [abstract no: PUK5]. Value in Health 2018;21(Suppl 1):S266. [EMBASE: 623584854] [Google Scholar]

Ghaffari 2015 {published data only}

- Ghaffari A, Hashemi N, Ghofrani H, Adenuga G. Urgent-start peritoneal dialysis versus other modalities of dialysis: long-term outcomes. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2015;64(4):A37. [EMBASE: 71874973] [Google Scholar]

Jin 2016 {published data only}

- Jin H, Fang W, Zhu M, Yu Z, Fang Y, Yan H, et al. Urgent-start peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in ESRD patients: complications and outcomes. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 2016;11(11):e0166181. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Ni Z, Che X, Gu L, Zhu M, Yuan J, et al. Peritoneal dialysis as an option for unplanned dialysis initiation in patients with end-stage renal disease and diabetes mellitus. Blood Purification 2019;47(1-3):52-7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Ni Z, Mou S, Lu R, Fang W, Huang J, et al. Feasibility of urgent-start peritoneal dialysis in older patients with end-stage renal disease: a single-center experience. Peritoneal Dialysis International 2018;38(2):125-30. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koch 2012 {published data only}

- Koch M, Kohnle M, Trapp R, Haastert B, Rump LC, Aker S. Comparable outcome of acute unplanned peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012;27(1):375–80. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lobbedez 2008 {published data only}

- Lobbedez T, Lecouf A, Ficheux M, Henri P, Hurault de Ligny B, Ryckelynck JP. Is rapid initiation of peritoneal dialysis feasible in unplanned dialysis patients? A single-centre experience. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2008;23(10):3290–4. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2017 {published data only}