Abstract

Background

This is the third update of this review, first published in July 2009. All major guidelines on treatment of hypertension recommend weight loss; anti‐obesity drugs may be able to help in this respect.

Objectives

Primary objectives:

To assess the long‐term effects of pharmacologically‐induced reduction in body weight in adults with essential hypertension on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, and adverse events (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events)..

Secondary objectives:

To assess the long‐term effects of pharmacologically‐induced reduction in body weight in adults with essential hypertension on change from baseline in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and on body weight reduction.

Search methods

For this updated review, the Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases for randomised controlled trials up to March 2020: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov. The searches had no language restrictions. We contacted authors of relevant papers about further published and unpublished work.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of at least 24 weeks' duration in adults with hypertension that compared approved long‐term weight‐loss medications to placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, assessed risks of bias, and extracted data. Where appropriate and in the absence of significant heterogeneity between studies (P > 0.1), we pooled studies using a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. When heterogeneity was present, we used the random‐effects method and investigated the cause of the heterogeneity.

Main results

This third update of the review added one new trial, investigating the combination of naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo. Two medications, which were included in the previous versions of this review (rimonabant and sibutramine) are no longer considered relevant for this update, since their marketing approval was withdrawn in 2010 and 2009, respectively. The number of included studies in this review update is therefore six (12,724 participants in total): four RCTs comparing orlistat to placebo, involving a total of 3132 participants with high blood pressure and a mean age of 46 to 55 years; one trial comparing phentermine/topiramate to placebo, involving 1305 participants with high blood pressure and a mean age of 53 years; and one trial comparing naltrexone/bupropion to placebo, involving 8283 participants with hypertension and a mean age of 62 years. We judged the risks of bias to be unclear for the trials investigating orlistat or naltrexone/bupropion. and low for the trial investigating phentermine/topiramate. Only the study of naltrexone/bupropion included cardiovascular mortality and morbidity as predefined outcomes.

There were no differences in the rates of all‐cause or cardiovascular mortality, major cardiovascular events, or serious adverse events between naltrexone/bupropion and placebo. The incidence of overall adverse events was significantly higher in participants treated with naltrexone/bupropion. For orlistat, the incidence of gastrointestinal side effects was consistently higher compared to placebo. The most frequent side effects with phentermine/topiramate were dry mouth and paraesthesia. After six to 12 months, orlistat reduced systolic blood pressure compared to placebo by mean difference (MD) −2.6 mm Hg (95% confidence interval (CI) −3.8 to −1.4 mm Hg; 4 trials, 2058 participants) and diastolic blood pressure by MD −2.0 mm Hg (95% CI −2.7 to −1.2 mm Hg; 4 trials, 2058 participants). After 13 months of follow‐up, phentermine/topiramate decreased systolic blood pressure compared to placebo by −2.0 to −4.2 mm Hg (1 trial, 1030 participants) (depending on drug dosage), and diastolic blood pressure by −1.3 to −1.9 mm Hg (1 trial, 1030 participants) (depending on drug dosage). There was no difference in the change in systolic or diastolic blood pressure between naltrexone/bupropion and placebo (1 trial, 8283 participants). We identified no relevant studies investigating liraglutide or lorcaserin in people with hypertension.

Authors' conclusions

In people with elevated blood pressure, orlistat, phentermine/topiramate and naltrexone/bupropion reduced body weight; the magnitude of the effect was greatest with phentermine/topiramate. In the same trials, orlistat and phentermine/topiramate, but not naltrexone/bupropion, reduced blood pressure. One RCT of naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo showed no differences in all‐cause mortality or cardiovascular mortality or morbidity after two years. The European Medicines Agency refused marketing authorisation for phentermine/topiramate due to safety concerns, while for lorcaserin the application for European marketing authorisation was withdrawn due to a negative overall benefit/risk balance. In 2020 lorcaserin was also withdrawn from the US market. Two other medications (rimonabant and sibutramine) had already been withdrawn from the market in 2009 and 2010, respectively.

Plain language summary

Do medicines for weight loss affect blood pressure, and reduce the effects of high blood pressure (hypertension)?

What is high blood pressure (hypertension)?

Blood pressure is a measure of the force that your heart uses to pump blood around your body. It is usually given as two figures: the pressure when your heart pushes blood out (systolic pressure), and the pressure when your heart rests between beats (diastolic pressure). Blood pressure is considered to be high when systolic pressure is over 140 and/or diastolic pressure is over 90, often written as '140 over 90' and measured in millimetres of mercury (mm Hg). The risk of developing high blood pressure increases as you get older.

Hypertension can increase people's risk of developing serious long‐term health problems, such as heart attack or stroke. Lowering blood pressure in people with hypertension reduces the number of people who develop diseases of the heart and blood vessels (cardiovascular disease), which leads to fewer deaths and cardiovascular problems.

Weight and hypertension

Hypertension treatment guidelines recommend keeping to a healthy weight and losing weight when needed. Some people may take medicines to help reduce their weight.

Why we did this Cochrane Review

Medicines licensed for use in weight loss in the USA and Europe include orlistat and naltrexone combined with bupropion. Another combination, phentermine with topiramate, is licensed in the USA only. We wanted to find out if weight‐loss medicines have long‐lasting effects on blood pressure, and whether they could reduce the unwanted effects of high blood pressure on people's health.

What did we do?

We searched for studies about the effects of taking weight‐loss medicines in people with high blood pressure. We were interested in how these medicines affected blood pressure and body weight. We also wanted to know how many people experienced any unwanted effects, how many people developed cardiovascular disease, and if any people died.

We looked for randomised controlled studies, in which the treatments people received were decided at random. This type of study usually gives the most reliable evidence about the effects of a treatment.

We assessed the reliability of the evidence we found. We considered factors such as: how the studies were conducted, how many people they involved, and whether their findings were consistent across studies.

Search date: we included evidence published up to March 2020.

What we found

We found six studies in 12,724 people with high blood pressure (average age 46 to 62 years). The studies were conducted in the USA (3 studies) and Europe (3 studies), and lasted from 6 months to 28 months.

All studies compared the effects of taking a weight‐loss medicine with effects of taking a dummy medicine (placebo).

What are the results of our review?

Orlistat may reduce weight and probably reduces blood pressure (4 studies; 2058 people).

Phentermine plus topiramate may reduce weight and may reduce blood pressure (1 study; 1305 people).

Naltrexone plus bupropion probably reduces weight but probably does not reduce blood pressure (1 study; 8283 people).

One study looked at the risk of death and major unwanted cardiovascular effects; it showed no differences between naltrexone plus bupropion treatment and a placebo after two years.

People taking weight‐loss medicines reported more unwanted effects than those taking a placebo. The most common unwanted effects were digestive problems (for orlistat, and phentermine plus topiramate), dry mouth and skin tingling or numbness (for naltrexone plus bupropion).

How reliable are these results?

Results are from a small number of studies. In some studies, there were few events for some measures we were interested in.

We are moderately confident about how orlistat and naltrexone plus bupropion affected weight loss and blood pressure. However, results might change if more evidence becomes available.

We are less confident about the effects of phentermine plus topiramate; the unwanted effects of orlistat, and the risk of unwanted cardiovascular events associated with naltrexone plus bupropion. Results are likely to change if more evidence becomes available.

Conclusions

Some weight‐loss medicines reduce weight and blood pressure in people with high blood pressure, but may cause unwanted effects. We did not find enough evidence about whether taking weight‐loss medicines to lose weight could reduce death and cardiovascular disease.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension is a chronic condition associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. It is estimated that raised blood pressure affects 1.13 billion people worldwide and leads to over 9 million deaths each year (WHO 2013). Lowering blood pressure levels in hypertensive people has been shown to be an effective means of reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiological investigations have consistently found an association between high blood pressure and different lifestyles, one of them being excess body weight. Major guidelines recommend weight reduction as a first‐step intervention in the therapy of hypertensive people (Hypertension Canada 2018; ACC/AHA 2017; ESC/ESH 2018; NICE 2019). Body weight may be reduced by lifestyle modifications as well as pharmacological and invasive interventions.

Description of the intervention

For a select group of overweight or obese people for whom lifestyle interventions are unsuccessful, anti‐obesity drugs may be an option to help reduce body weight. Orlistat, sibutramine, and rimonabant were formerly the most commonly used anti‐obesity drugs, but only orlistat, which was approved in 1998, still has market approval for the long‐term treatment of obesity. Since 2012, four additional drugs (lorcaserin, liraglutide, phentermine/topiramate, and naltrexone/bupropion) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for obese (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2) people with at least one obesity‐related comorbidity (FDA 2012a; FDA 2012b; FDA 2014a; FDA 2014b). These medications have been quoted in guidelines for the long‐term pharmacological treatment of obesity (Apovian 2015). In Europe, liraglutide, which has also been approved for the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2, and naltrexone/bupropion were approved for weight management in March 2015 by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (EMA 2015a; EMA 2015b). In 2013, the manufacturer of lorcaserin withdrew its application to the EMA after the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use raised safety concerns (EMA 2013a), while the EMA refused marketing authorisation for phentermine/topiramate due to safety concerns (EMA 2013c).

Sibutramine and rimonabant both lost their marketing approval about 10 years ago.Sibutramine was approved by the FDA in 1997 and by the EMA in 1999. Preliminary results of the Sibutramine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (SCOUT 2010), presented in October 2009, showed an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events (such as heart attack or stroke) among people with known cardiovascular disease who were taking sibutramine. This led the FDA and EMA to recommend suspension of the marketing authorisation (EMA 2010a; EMA 2010b; FDA 2010a). In January 2010, Abbot Laboratories agreed to voluntarily withdraw sibutramine from the European market (Abbott 2010), and in October 2010 from the US market (FDA 2010b). Rimonabant received regulatory approval in several European countries in 2006, but failed to receive FDA approval after preclinical and clinical data raised concerns about an association between rimonabant intake and the increased incidence of psychiatric adverse events, including suicidality, an ill‐defined constellation of neurological signs and symptoms, and seizures (FDA 2007). In October 2008, the EMA recommended the suspension of rimonabant from the market because of newly‐available post‐marketing analyses demonstrating detrimental effects compared with placebo (EMA 2008a; EMA 2008b). In January 2009, the European Commission decided to withdraw market authorisation for rimonabant in all countries of the European Union (EMA 2009a). In February 2020, lorcaserin was withdrawn from the US market by the manufacturer after a request by the FDA (Eisai Inc. 2020). This action was taken after an FDA analysis of data from a safety clinical trial showed an increased occurrence of cancer in participants treated with lorcaserin (FDA 2020).

How the intervention might work

Anti‐obesity drugs aim to reduce body weight and to maintain the weight reduction over a longer period. Orlistat is a gastric and pancreatic lipase inhibitor that blocks the absorption of about 30% of dietary fat (Padwal 2007). Liraglutide, a glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist, appears to regulate appetite by increasing feelings of satiety (Russell‐Jones 2009). The combination of phentermine, a neurostabiliser, and topiramate, an antiseizure medication, appears to have an additive effect on weight reduction (Aronne 2013). In combination with naltrexone, bupropion, a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, reduces appetite and increases energy expenditure (Caixas 2014). The mechanisms by which these three medications cause weight loss are not yet fully understood. Lorcaserin is a selective serotonin receptor agonist and increases the sense of fullness (Taylor 2013). Dietary‐intervention studies in hypertensive people have shown a positive association between weight loss and blood pressure reduction (Horvath 2008). It therefore seems reasonable to suppose that medical weight‐reducing treatment may also lead to a fall in blood pressure.

Why it is important to do this review

For overweight or obese people with established hypertension, blood pressure should first be managed with non‐pharmacological interventions such as weight reduction (Hypertension Canada 2018; ACC/AHA 2017; ESC/ESH 2018; NICE 2019). Since anti‐obesity drugs may support the efforts of people to reduce body weight, it is important that the physician be informed about the efficacy and potential harms of these drugs before prescribing them.

Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have shown that pharmacological weight‐reducing interventions with orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate,and liraglutide reduce both blood pressure and body weight (Chan 2013; Khera 2018; LeBlanc 2018; Zhang 2015). Treatment with naltrexone/bupropion reduced body weight but did not lower blood pressure (Caixas 2014; Khera 2018, LeBlanc 2018). None of these reviews investigated the efficacy and safety of weight‐reducing drugs in the subgroup of overweight or obese people with hypertension. Furthermore, only limited data were available on the question of whether pharmacological weight reduction lowers the risk of mortality and other patient‐relevant endpoints. Results from a few RCTs showed no beneficial effect on cardiovascular events for liraglutide or phentermine/topiramate compared to placebo (LeBlanc 2018). Two studies examining clinical endpoints for rimonabant (CRESCENDO 2010) and sibutramine (SCOUT 2010) have resulted in the drugs being withdrawn from the market. Neither sibutramine nor rimonabant are therefore considered relevant for this review update.This currently leaves orlistat, liraglutide and naltrexone/bupropion as approved for the long‐term treatment of obesity in Europe and the USA, and lorcaserin and phentermine/topiramate as approved for the long‐term treatment of obesity in the USA only.

This is an update of a previously‐published Cochrane Review (Siebenhofer 2016).

Objectives

Primary objectives:

To assess the long‐term effects of pharmacologically‐induced reduction in body weight in adults with essential hypertension on all‐cause mortality, cardiovascular morbidity, and adverse events (including total serious adverse events, withdrawal due to adverse events, and total non‐serious adverse events).

Secondary objectives:

To assess the long‐term effects of pharmacologically‐induced reduction in body weight in adults with essential hypertension on change from baseline in systolic blood pressure, change from baseline in diastolic blood pressure, and body weight reduction.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

The study design must meet the following criteria: all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing pharmacologic interventions approved for long‐term weight management versus placebo, with a follow‐up of at least 24 weeks. The reason for including only studies with a follow‐up of at least 24 weeks is that studies of shorter duration cannot show long‐term effects. Any additional active care (for example, antihypertensive medication) must have been applied to the active treatment group and to the control group.

Types of participants

Men and non‐pregnant women aged 18 years or older with essential hypertension (i.e. a baseline blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg systolic or a diastolic blood pressure of at least 90 mm Hg, or both, or people on antihypertensive treatment), for whom at least one of the following outcomes was reported: mortality, cardiovascular outcomes, adverse events, or blood pressure.

Types of interventions

Monotherapy with drugs for long‐term weight management (orlistat, phentermine/topiramate, lorcaserin, naltrexone/bupropion, or liraglutide).

Types of outcome measures

We included the following outcomes:

Primary outcomes

Total mortality

Cardiovascular morbidity

Adverse events (withdrawals due to adverse events, adverse events related to a particular anti‐obesity drug)

Secondary outcomes

Change in systolic blood pressure

Change in diastolic blood pressure

Change in body weight

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases, without language, publication year or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) (searched 20 March 2020);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web; searched 17 March 2020);

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 onwards), MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print, and MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (searched 17 March 2020);

Embase Ovid (from 1974 onwards) (searched 17 March 2020);

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); (searched 17 March 2020);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.it.trialsearch); (searched 17 March 2020).

The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. Where appropriate, they were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6 (Handbook 2019; Lefebvre 2019)). We present search strategies for major databases in Appendix 4.

The search strategy used in the previous review versions is documented in Appendix 5, Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

Searching other resources

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the Hypertension Specialised Register segment (which includes searches of MEDLINE, Embase, and Epistemonikos for systematic reviews) to retrieve existing reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. The Specialised Register also includes searches for controlled trials in the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), CAB Abstracts & Global Health, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses and Web of Science.

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to relevant trials.

Where necessary, we contacted authors of key papers and abstracts to request additional information about their trials

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (from SW, TS, KH, KJ) independently screened the title and abstract of each reference identified by the search and applied the inclusion criteria. We retrieved potentially relevant studies in full, and again two review authors (SW, TS) independently decided whether they met the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement, we also obtained the full article and the two review authors inspected it independently, resolving differences in opinion by recourse to a third party. If a resolution of the disagreement was not possible, we classified the article as 'awaiting assessment' and contacted the authors of the study for clarification.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (from SW, TS, KH, KJ, CK) independently extracted data using a data extraction form. We resolved differences in data extraction by consensus, referring back to the original article. We sought information from the authors of the primary studies if necessary. We extracted, checked, and recorded the following data.

1. General information

This included all publications of a single trial, the sponsor of the trial (specified, known or unknown), and the country in which the trial was conducted.

2. Methods section

The information on the methods summarised the characteristics of the trial, participants, and interventions, and the outcome measures used and reported in the publication.

2.1. Characteristics of the trial

The reported items included the design and duration of the trial, randomisation (and method), allocation concealment (and method), blinding (participants, people administering treatment, outcome assessors), and checking of blinding.

2.2. Characteristics of participants

This included the number of participants in each group, how the participants were selected (random, convenience), the exclusion criteria used, and their demographic characteristics (for example, age, gender, nationality, ethnicity). We extracted disease‐related information about duration of hypertension. We checked the similarity of groups at baseline as well as reports about withdrawals and losses to follow‐up (reasons/description), and described them in the 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies. If subgroups were analysed, we noted and reported the reasons and methods.

2.3. Characteristics of interventions

The relevant information to be extracted was the duration of the intervention, length of follow‐up (in months), the type of anti‐obesity drug (orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, or liraglutide), the dose, and the administration route.

2.4. Characteristics of outcome measures

We reported the measures mentioned in the outcome section and any other outcomes measured in the study.

3. Data from clinical trial registers

If data from included trials were available as study results in clinical trial registers such as ClinicalTrials.gov or similar sources, we made full use of this information and extracted the data. If there was also a full publication of the trial, we collated and critically appraised all available data. If an included trial was marked as a completed study in a clinical trial register but no additional information (study results, publication or both) was available, we added this trial to the table Characteristics of excluded studies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (from SW, TS, KH, KJ, CK) independently assessed trials fulfilling the inclusion criteria in order to evaluate methodological quality, resolving any differences in opinion by discussion with a third review author (from TS, KH, KJ). We assessed all trials using the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2019), and we judged the 'Risk of bias' criteria as having low, high or unclear risk. We evaluated individual bias items as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions according to the categories: adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential biases. We evaluated the risk of bias for the categories of blinding and incomplete outcome data separately for each outcome (Hróbjartsson 2013). We noted whether endpoints were self‐reported, investigator‐assessed or adjudicated outcome measures.

Measures of treatment effect

When at least two included trials were available for a comparison and a given outcome, we tried to express dichotomous data as a risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous outcomes (changes in blood pressure and body weight), we estimated the intervention effect using the mean difference with a 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

We intended to consider the level at which randomisation occurred, such as cross‐over trials, cluster‐randomised trials and multiple observations for the same outcome. If more than one comparison from the same trial was eligible for inclusion in the same meta‐analysis, we either combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison or appropriately reduced the sample size so that the same participants did not contribute more than once (splitting the 'shared' group into two or more groups). While the latter approach offers some solution to adjusting the precision of the comparison, it does not account for correlation arising because the same set of participants was included in multiple comparisons (Deeks 2019).

Dealing with missing data

We obtained relevant missing data from authors and from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care report (IQWiG 2006). We evaluated important numerical data such as screened, eligible, and randomised participants as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT) and per‐protocol (PP) populations. We investigated attrition rates, for example dropouts, losses to follow‐up, and withdrawals. We critically appraised issues of missing data, ITT, and PP and, if available, compared them to the specification of primary outcome parameters and power calculations.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using Higgins I2.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we included 10 or more trials that investigated a particular outcome, we assessed publication bias and small‐study effects using the funnel plot. Several explanations may account for funnel plot asymmetry, including true heterogeneity of effect with respect to trial size, poor methodological design (and hence bias of small trials) and publication bias. We therefore interpreted the results cautiously (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We summarised data statistically when they were available, sufficiently similar, and of sufficient quality. We performed analyses separately for each drug. We performed statistical analysis according to the statistical guidelines referenced in the current version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2019). We considered fixed‐effect and random‐effects models for the meta‐analyses. In case of between‐study variability, we present the results of the random‐effects model. If standard deviations were unavailable, we approximated them on the basis of P values and sample sizes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses where appropriate. Heterogeneity among participants could be related to, for example, sex, age, body mass index, concomitant diseases, ethnicity, blood pressure at baseline, blood pressure goals, concomitant antihypertensive therapy, and socioeconomic status.

Sensitivity analysis

We tested the robustness of our results where appropriate, using several sensitivity analyses (for example, study quality or PP versus ITT analyses, studies with large dropout rates and losses to follow‐up). In case of substantial heterogeneity (I2 greater than 50%), we planned to perform sensitivity analyses for the following items: study quality, PP versus ITT analyses, sex, age, body mass index, concomitant diseases, ethnicity, blood pressure at baseline, blood pressure goals, concomitant antihypertensive therapy, and socioeconomic status.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence (Guyatt 2011). We present the main results of the review, including a summary of the data, the magnitude of the effect and the overall certainty of the evidence, for each type of weight‐reducing drug separately in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3.

Summary of findings 1. Orlistat versus placebo for weight reduction.

| Orlistat compared with placebo for weight reduction | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Men and non‐pregnant women ≥ 18 years old with essential hypertension Intervention: Orlistat Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with orlistat | |||||

|

Total mortality Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 208 weeks |

2 deaths (OD subgroup) and 1 death (OS subgroup) with orlistat, and no deaths with placebo in 1 trial; no deaths with orlistat or placebo in 2 other trials | ‐ | 1488 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Very low event rate. | |

|

Cardiovascular morbidity Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

see comment | ‐ | 1811 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb |

Reporting of results too diverse to allow a meta‐analysis and small number of events. The effects of orlistat compared with placebo for this outcome are uncertain. | |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 208 weeks |

101 per 1000 | 146 per 1000 (111 to 192) | RR 1.45 (1.10 to 1.91) | 1476 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec | ‐ |

|

All adverse events Follow‐up: 24‐208 weeks |

865 per 1000 | 977 per 1000 (727 to 1000) | RR 1.13 (0.84 to 1.54) | 1386 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd | 98% heterogeneity |

|

Change in systolic blood pressure compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 52 weeks |

Reduction of systolic blood pressure ranged across control groups from 0.9 to 11.0 mm Hg | MD 2.58 mm Hg lower (3.78 lower to 1.37 lower) | ‐ | 2058 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec | ‐ |

|

Change in diastolic blood pressure compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 52 weeks |

Reduction of diastolic blood pressure ranged across control groups from 0.8 to 9.2 mm Hg | MD 1.97 mm Hg lower (2.72 lower to 1.22 lower) | ‐ | 2058 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatec | ‐ |

|

Change in body weight compared to placebo (kg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 24 ‐ 52 weeks |

Reduction of body weight ranged across control groups from 1.8 to 6.93 kg | MD 3.74 kg lower (4.70 lower to 2.78 lower) | ‐ | 2080 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd | ‐ |

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; OD: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; OS: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (small number of trials, very low event rates) ‐ see Appendix 1. bDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (small number of trials, very low event rates) and by one level because of high risk of bias (attrition bias) ‐ see Appendix 1. cDowngraded by one level because of imprecision (small number of trials) ‐ see Appendix 1. dDowngraded by one level because of imprecision (small number of trials) and by two levels because of severe inconsistency (98% heterogeneity) ‐ see Appendix 1.

Summary of findings 2. Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo for weight reduction.

| Phentermine/topiramate compared with placebo for weight reduction | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Men and non‐pregnant women ≥ 18 years old with essential hypertension Intervention: Phentermine/topiramate Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with phentermine/topiramate | |||||

|

Total mortality Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

see comment | ‐ | 1305 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | No death occurred in the hypertensive subgroup of the only included RCT. | |

|

Cardiovascular morbidity Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

see comment | ‐ | 1305 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb |

2.3% of the hypertensive participants in the low‐dose phen/top group, 3.7% in the high‐dose phen/top group, and 1.7% in the placebo group experienced treatment‐emergent cardiovascular adverse events. | |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

42 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (21 to 62) | RR 0.85 (0.49 to 1.48) | 1305 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

|

All adverse events Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

773 per 1000 | 873 per 1000 (835 to 927) | RR 1.13 (1.08 to 1.20) | 1305 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

|

Change in systolic blood pressure compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

Reduction of systolic blood pressure was −4.9 mm Hg | Low dose: MD 2.0 mm Hg lower (3.97 lower to 0.03 lower) |

‐ | 772 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| High dose: MD 4.2 mm Hg lower (5.85 lower to 2.55 lower) |

‐ | 1030 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ | ||

|

Change in diastolic blood pressure compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

Reduction of diastolic blood pressure was −4.9 mm Hg | Low dose: MD 1.3 mm Hg lower (2.6 lower to 0.0 lower) | ‐ | 772 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ |

| High dose: MD 1.9 mm Hg lower (2.88 lower to 0.92 lower) | ‐ | 1030 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | ‐ | ||

|

Change in body weight as compared to placebo (%) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

Reduction of body weight was −1.9 % | Low dose: MD 6.3 % lower (7.37 lower to 5.23 lower) | ‐ | 772 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Percentage change from initial body weight. |

| High dose: MD 8.2 % lower (9.09 lower to 7.31 lower) | ‐ | 1030 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Percentage change from initial body weight. | ||

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (single study) ‐ see Appendix 2. bDowngraded by two levels because of serious imprecision (single study) and by one level because of high risk of bias (attrition bias) ‐ see Appendix 2.

Summary of findings 3. Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo for weight reduction.

| Naltrexone/bupropion compared with placebo for weight reduction | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Men and non‐pregnant women ≥ 18 years old with essential hypertension Intervention: Naltrexone/bupropion Comparison: Placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with naltrexone/bupropion | |||||

|

Total mortality Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

15 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (11 to 21) | RR 0.99 (0.70 to 1.40) | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

|

Cardiovascular morbidity Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

29 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (25 to 40) | RR 1.11 (0.87 to 1.41) | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb | MI, stroke + hospitalisation for unstable angina. |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

205 per 1000 | 215 per 1000 (196 to 233) | RR 1.05 (0.96 to 1.14) | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

|

All adverse events Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

256 per 1000 | 432 per 1000 (404 to 460) | RR 1.69 (1.58 to 1.80) | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

|

Change in systolic blood pressure as compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 56 weeks |

Increase of systolic blood pressure was 2.2 mm Hg | MD 0.0 mm Hg higher (0.6 lower to 0.6 higher) | ‐ | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

|

Change in diastolic blood pressure as compared to placebo (mm Hg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

Increase of diastolic blood pressure was 1.1 mm Hg | MD 0.3 mm Hg higher (0.08 lower to 0.68 higher) | ‐ | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

|

Change in body weight as compared to placebo (kg) from baseline to end of study Follow‐up: 121 weeks |

Reduction of body weight was 0.0 kg | MD 1.9 kg lower (2.07 lower to 1.73 lower) | ‐ | 8283 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | ‐ |

| CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by one level because of imprecision (single study). bDowngraded by two levels because of imprecision (single study) and increased risk of bias (other bias: only 50% of the planned number of cardiovascular events were reported) ‐ see Appendix 3

We include all primary and secondary outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables, listed according to priority:

Total mortality

Cardiovascular morbidity

Adverse events

Change in systolic blood pressure

Change in diastolic blood pressure

Change in body weight

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

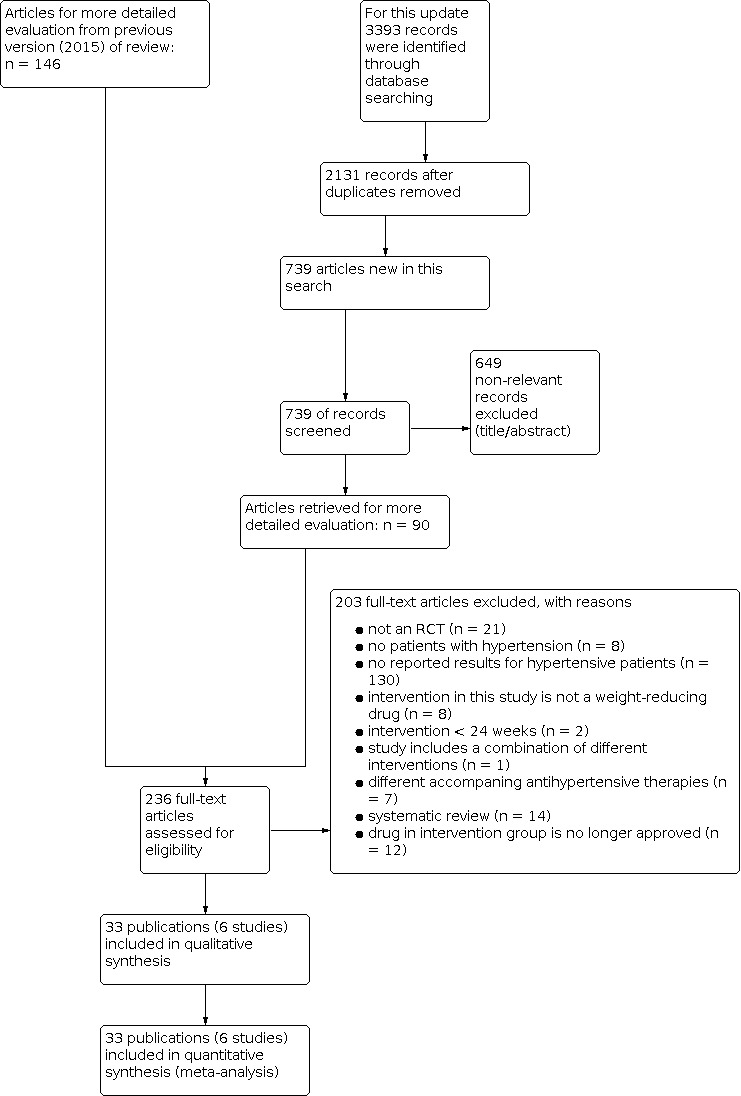

Our search of the electronic databases for this third update in 2020 yielded 739 records after correcting for duplication. The consensus was that on the basis of their abstracts, 649 of these were not relevant to the question under study and should be excluded. We identified no further studies from the reference lists of the included trials nor from relevant systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. We therefore identified 90 publications for further examination.

In the previous version of the review (Siebenhofer 2016) we retrieved 146 articles for full‐text evaluation. Among them was a report from the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), which provided data for an unpublished subgroup analysis of hypertensive people in the Xenical in the Prevention of Diabetes in Obese Subjects (XENDOS) study (IQWiG 2006; XENDOS 2001‐2006).

In summary, we identified 236 publications for further examination. After screening the full text of these selected publications and after contacting authors of potentially relevant studies, we excluded 198 articles. We also excluded five publications (four studies) from the previous version of this review that investigated the effect of sibutramine, since this drug is no longer considered relevant for the current update. Finally, three additional publications referring to the CONQUER 2013 trial (which had been included in the previous version of the review), and five articles referring to one new trial could be included from the 2020 update search. Together with the remaining 25 publications (five studies) from the previous version of the review (Siebenhofer 2016), we include in this third update 33 publications describing six completed studies (see Figure 1 for details of the PRISMA statement; PRISMA 2009).

1.

Study flow diagram.

All relevant studies were published after the year 2000 and were written in English, except for the report from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG 2006), which was published in German.

Included studies

We have provided details of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies table and in Table 4; Table 5; Table 6. The following gives a brief overview of the comparisons between orlistat and placebo (four RCTs), naltrexone/bupropion and placebo (one RCT), and phentermine/topiramate and placebo (one RCT). We found no relevant studies investigating liraglutide or lorcaserin, since no results for participants with hypertension were available.

1. Overview of study populations.

| Study | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Description of power and sample size calculation | Randomised (N) | Safety (N) | ITT (N) | Finishing trial (N) | Randomised finishing trial (%) | Follow‐up (extended follow‐up) | |

| Orlistat vs placebo | |||||||||

| Bakris 2002 | Orlistat | The sample size determination for the present trial was based on a 2‐sample t‐test (2‐tailed). Since there were 2 primary efficacy parameters in this trial, body weight reduction and sitting diastolic BP reduction, Holm’s sequential rejection procedure was used to project the overall type I error rate 0.05, and α = 0.025 was chosen for the calculation of sample size for each parameter. A mean body weight change of 2.1 kg and a within‐group standard deviation of 6.1 kg would require 161 participants per group to provide a power of 0.8 at α = 0.025. A mean change of 3.0 mm Hg in sitting diastolic BP with a within‐group standard deviation of 8.5 mm Hg would require 153 participants per group to provide power of 0.8 with α = 0.025. Based on these calculations, and assuming a dropout rate of 35%, 496 participants (248 participants per group) had to be enrolled to ensure an adequate statistical power of at least 80% in either of the 2 primary efficacy parameters. | 278 | nr | 267 | 162 | 58 | 24 weeks | |

| Placebo | 276 | nr | 265 | 108 | 36 | ||||

| Cocco 2005 | Orlistat | nr | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 100 | 24 weeks | |

| Placebo | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 100 | ||||

| Guy‐Grand 2004 | Orlistat | Power calculations indicated that, with a power of 80% at the 0.05 significance level, 408 participants were needed to detect a 2.5 mm Hg difference in diastolic BP, 152 participants were needed to detect a 0.05% difference in HbA1c. 140 participants were needed to detect a 0.35 mmol/l difference in LDL‐cholesterol. | 499 (HT: 304) | nr | 499 (HT: 304) | 458 (HT: nr) | 91.6% (HT: nr) | 24 weeks | |

| Placebo | 505 (HT: 310) | nr | 505 (HT: 310) | 458 (HT: nr) | 90.7% (HT: nr) | ||||

| XENDOS 2001‐2006 | Orlistat (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [OD] |

A 2‐sided log‐rank test would require a minimum of ~ 95 primary cases of type 2 diabetes in both study groups combined to have 90% power of detecting a significant outcome at α = 0.05. With this event‐based design, 3305 participants were randomised and followed until sufficient events occurred. As a consequence of the design, study power would be unaffected by dropout rate. | 1650 | (HT: 408) | nr | 1640 (HT: nr) | (HT: 386) | 94.6 | 208 weeks |

| Orlistat (SBP ≥ 140mm Hg) [OS] |

(HT: 516) | nr | (HT: 491) | 95.2 | |||||

| Placebo (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [PD] |

1655 | (HT: 441) | nr | 1637 (HT: nr) | (HT: 421) | 95.5 | |||

| Placebo (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [PS] |

(HT: 509) | nr | (HT: 487) | 95.7 | |||||

| Phentermine/topiramate vs placebo | |||||||||

| CONQUER 2013 | Phen/Top [LD] | Power analysis based on data from a previous study suggested that 250 participants in each group would provide > 95% power to detect a difference of 4.4% in weight loss between placebo and active treatments at a significance level of 0.05. To enhance the power for detecting differences in safety outcomes, we planned to enrol about 2500 participants. | 498 (HT: 261) | 398 (HT: 261) | 488 (HT: 261) | 374 (HT: 256) | 75.1 (HT: 98.1) | 56 weeks | |

| Phen/Top [HD] | 995 (HT: 520) | 994 (HT: 520) | 981 (HT: 520) | 733 (HT: 514) | 73.7 (HT: 98.8) | ||||

| Placebo | 994 (HT: 524) | 993 (HT: 524) | 976 (HT: 524) | 616 (HT: 516) | 61.9 (HT: 98.5) | ||||

| Naltrexone/bupropion vs placebo | |||||||||

| Nissen 2016 | Nal/Bup | The trial was designed to provide 90% power to rule out the 1.4 margin (i.e. the upper limit of the confidence interval would not exceed 1.4) when the true HR is 1.0, which required 378 primary events. The early pre‐approval analysis to rule out the 2.0 margin required 87 primary events to provide 90% power when the true HR is 1.0. In both settings, a 1‐sided type I error (α) of 2.5% was used. To obtain sample sizes, an annualised rate of primary events of 1.5% in the placebo group was assumed. The recruitment was assumed to take 1.5 years, with maximum participant follow‐up of 4 years. It was assumed that 7% of the study population would discontinue during the lead‐in period, with a loss–to–follow‐up rate of 1.2% annually. | 4456 (HT: 4164) | 4455 (HT: 4164) | 4455 (HT: 4164) | 705 (HT: nr) | 15.8% (HT: nr) | 121 weeks | |

| Placebo | 4454 (HT: 4123) | 4450 (HT: 4119) | 4450 (HT: 4119) | 275 (HT: nr) | 6.2% (HT: nr) | ||||

DBD: diastolic blood pressure; HR: hazard ratio; HT: hypertensive subgroup; ITT: intention‐to‐treat; nr: not reported; [OD]: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [OS]: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; Phen/Top [HD]: phentermine/topiramate high dose (15 mg/92 mg); Phen/Top [LD]: phentermine/topiramate low dose (7.5 mg/46 mg); [PD]: placebo and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [PS]: placebo and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; SBD: systolic blood pressure.

2. Baseline characteristics (I).

| Study | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Description of participants | Nationality | Setting | Ethnic groups (%) | Duration of disease (mean years (SD)) | Antihypertensive treatment (%) |

| Orlistat vs placebo | |||||||

| Bakris 2002 | Orlistat | Obese individuals with insufficiently controlled hypertension | USA | Outpatient clinic | White (85) African American (11) Hispanic (4) Other (0) |

nr | Antihypertensive‐treatment at trial onset: 95% ACE‐inhibitor (27) Ca‐antagonists (29) β‐blocker (27) Diuretic (19) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (6) α‐blocker (10) Other (11), |

| Placebo | White (86) African American (12) Hispanic (1) Other (1) |

nr | antihypertensive‐treatment at trial onset: 94% ACE‐inhibitor (35) Ca‐antagonist (30) β‐blocker (26) Diuretic (14) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (10) α‐blocker (8) Other (9) |

||||

| Cocco 2005 | Orlistat | Obese individuals with metabolic syndrome, diabetes type 2, hypertension, mostly with coronary heart disease (77%) and concomitant cardiac dysfunction | Switzerland | Outpatient clinic | White (100) | nr | Antihypertensive‐treatment at trial onset: 100% ACE‐inhibitor (36) Ca‐antagonist (18) β‐blocker (49) Diuretic (low‐dose hydrochlorothiazide) (60) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (49) |

| Placebo | |||||||

| Guy‐Grand 2004 | Orlistat | Obese individuals with diabetes type 2, hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia | France | Private practices (endocrinologists) | nr | nr | Antihypertensive‐treatment at trial onset: 70% |

| Placebo | |||||||

| XENDOS 2001‐2006 | Orlistat (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [OD] | Obese individuals with normal or impaired glucose tolerancea | Sweden | Medical centres | nr | nr | ACE‐inhibitors (7) Ca‐antagonists (6) β‐blockers (17) Diuretics (7) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (2) |

| Orlistat (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [OS] | ACE‐inhibitors (6) Ca‐antagonists (6) β‐blockers (14) Diuretics (8) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (2) |

||||||

| Placebo (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [PD] | ACE‐inhibitors (7) Ca‐antagonists (7) β‐blockers (13) Diuretics (11) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (1) |

||||||

| Placebo (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [PS] | ACE‐inhibitors (8) Ca‐antagonists (8) β‐blockers (13) Diuretics (10) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists (2) |

||||||

| Phentermine/topiramate vs placebo | |||||||

| CONQUER 2013 | Phen/Top [LD] | Obese or overweight individuals with 2 or more comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes or prediabetes, or abdominal obesity)a | USA | Outpatient clinic | White (83) African American (15) Hispanic or Latino (10) |

nr | ACE inhibitors alone (26.9) β‐blockers alone (24.1) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists alone (15.5) ACE inhibitors + diuretics (5.8) ACE inhibitors + Ca‐antagonists (3.5), AT‐II‐receptor antagonists + diuretics (12.4) AT‐II‐receptor antagonists + Ca‐antagonists (0.9) |

| Phen/Top [HD] | |||||||

| Placebo | |||||||

| Naltrexone/bupropion vs placebo | |||||||

| Nissen 2016 | Nal/Bup | Overweight or obese people at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes | USA | Medical sites | White (83.3) Black (15.3) Other (1.4) |

12.2 (9.40) | 97.1 |

| Placebo | White (82.3) Black (15.3) Other (2.4) |

11.6 (9.03) | 97.2 | ||||

a only data for the predefined subgroup of hypertensive participants are reported here.

ACE inhibitors: angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; AT‐II‐receptor antagonists: angiotensin II‐receptor antagonists; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; nr: not reported; [OD]: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [OS]: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; Phen/Top; [HD]: phentermine/topiramate high dose (15 mg/92 mg); Phen/Top [LD]: phentermine/topiramate low dose (7.5 mg/46 mg); [PD]: placebo and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [PS]: placebo and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; SBD: systolic blood pressure; SD: standard deviation.

3. Baseline characteristics (II).

| Study | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Age (mean years (SD)) | Sex (female %) | BMI (mean kg/m² (SD)) | Body weight (mean kg (SD)) | Sitting systolic blood pressure (mean mm Hg (SD)) | Sitting diastolic blood pressure (mean mm Hg (SD)) | Comorbid conditions (%) |

| Orlistat vs placebo | ||||||||

| Bakris 2002 | Orlistat | 53.2 (0.5) | 63 | 35.8 (3.9) | 101.2 (1.0) | 154.2 (13.4) | 98.4 (3.7) | diabetes (8) |

| Placebo | 52.5 (0.5) | 59 | 35.4 (4.0) | 101.5 (1.0) | 150.8 (12.7) | 98.3 (35) | diabetes (8) | |

| Cocco 2005 | Orlistat | 54.9 (5.1) | 51 | 36.5 (1.9) | 107.0 (5.7) | 145.8 (9.8) | 87.8 (7.3) | metabolic syndrome (100) coronary heart disease (77) myocardial infarction (47) |

| Placebo | 54.5 (4.5) | 51 | 36.1 (1.8) | 106.0 (5.9) | 142.1 (6.2) | 85.3 (5.6) | ||

| Guy‐Grand 2004 | Orlistat | 49.1 (0.6) | 69 | 34.3 (0.2) | 93.9 (0.8) | 150.0 (0.8) | 96.9 (0.3) | nr |

| Placebo | 49.5 (0.5) | 65 | 33.9 (0.2) | 93.5 (0.8) | 152.2 (0.9) | 97.0 (0.3) | nr | |

| XENDOS 2001‐2006 | Orlistat (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [OD] | 46 (7) | 3862 | nr | 116 (17) | 146 (13) | 95 (5) | nr |

| Orlistat (SBP ≥ 140mm Hg) [OS] | 47(7) | 42 | nr | 116 (17) | 149 (10) | 91 (9) | nr | |

| Placebo (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [PD] | 46 (7) | 4456 | nr | 114 (18) | 142 (126) | 95 (5) | nr | |

| Placebo (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [PS] | 47(7) | 42 | nr | 115 (18) | 149 (8) | 91 (8) | nr | |

| Phentermine/topiramate vs placebo | ||||||||

| CONQUER 2013 | Phen/Top [LD] | 53.0 (9.8) | 65.9% | 36.7 (4.6) | 104.4 (18.4) | 134.2 (13.0) | 83.7 (9.1) | nr |

| Phen/Top [HD] | ||||||||

| Placebo | ||||||||

| Naltrexone/bupropion vs placebo | ||||||||

| Nissen 2016 | Nal/Bup | 61.8 (7.27) | 54.5 | 37.1 (5.27) | 106 (19.09) | 126.1 (12.55) | 74.5 (9.01) | History of cardiovascular disease (30.3) History of Type 2 diabetes (86.4) History of dyslipidaemia (92.4) History of low LDL (27.8) Current smoker (8.4) |

| Placebo | 61.6 (7.38) | 54.4 | 37.3 (5.42) | 106.6 (19.17) | 125.7 (12.62) | 74.4 (9.14) | History of cardiovascular disease (31.3) History of type 2 diabetes (86.9) History of dyslipidemia (92.1) History of low LDL (28.2) Current smoker (8.5) |

|

BMI: body mass index; LDL: low‐density lipoprotein; nr: not reported; [OD]: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [OS]: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; Phen/Top [HD]: phentermine/topiramate high dose (15 mg/92 mg); Phen/Top [LD]: phentermine/topiramate low dose (7.5 mg/46 mg); [PD]: placebo and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [PS]: placebo and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; SBD: systolic blood pressure; SD: standard deviation.

Orlistat versus placebo

All four included studies had a parallel, double‐blind design (Bakris 2002; Cocco 2005; Guy‐Grand 2004; XENDOS 2001‐2006). Only Cocco 2005 did not mention any industry sponsorship, and it was the only study that was performed as a single‐centre trial.

Participants and duration

The four included studies involved a total of 3132 hypertensive participants with a mean age of 46 to 55 years, a baseline systolic blood pressure (BP) of 142 to 154 mm Hg and a baseline diastolic BP of 85 to 98 mm Hg. Mean treatment duration was 6 to 48 months. All participants in Bakris 2002 and Cocco 2005 were overweight and hypertensive. In Cocco 2005 all participants also had diabetes mellitus type 2. One trial (Guy‐Grand 2004) included overweight people with diabetes mellitus type 2, hypercholesterolaemia or hypertension, and reported results for the predefined subgroup of participants with hypertension. XENDOS 2001‐2006 included both normotensive and hypertensive obese participants. Data are available for two predefined subgroups of hypertensive participants (first subgroup: diastolic BP at baseline ≥ 90 mm Hg; second subgroup: systolic BP at baseline ≥ 140 mm Hg). Participants in one subgroup may also be included in the other subgroup. We present the data for the two subgroups separately in this review. For meta‐analyses we used the results of the subgroup with participants having a diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mm Hg at baseline.

Interventions

Participants received either 120 mg orlistat three times daily or placebo in all studies. In Bakris 2002, Cocco 2005 and XENDOS 2001‐2006, participants in all study groups were also encouraged to modify their lifestyle and increase physical activity.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

No study included mortality or cardiovascular morbidity as predefined outcomes. All studies reported adverse events.

Secondary outcomes

All studies described the mean change in systolic and diastolic BP and the mean change in body weight.

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

The only included study was multicentre, with 93 study sites in the USA (CONQUER 2013). The study had a parallel, double‐blind design and the industry sponsor was mentioned.

Participants and duration

The included study involved 2487 obese or overweight people with two or more comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes or prediabetes, or abdominal obesity). The hypertensive subgroup included 1305 participants with a mean age of 53 years, a mean baseline systolic BP of 134 mm Hg and a mean baseline diastolic BP of 84 mm Hg. About 90% of the included participants were taking antihypertensive medication. Among the hypertensive subgroup, 216 participants had uncontrolled hypertension at baseline. The treatment duration was 56 weeks.

Interventions

The study compared two different dose regimens of phentermine/topiramate once daily versus placebo. All participants in the active groups received an initial dose of 7.5 mg phentermine and 23 mg topiramate. During an initial four‐week titration period, doses were increased weekly (3.75 mg phentermine and 23 mg topiramate) until the assigned dosages of 7.5 mg phentermine/46.0 mg topiramate (group low dose) or 15 mg phentermine/92.0 mg topiramate (group high dose) were achieved. The assigned dosages were maintained for 52 weeks. In addition, all participants received a standardised counselling for diet (to reduce caloric intake by 500 kcal/day) and lifestyle modification.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The study did not include mortality or cardiovascular morbidity as predefined outcomes. Adverse events were reported.

Secondary outcomes

The study described the mean change in systolic and diastolic BP and the mean percentage change in body weight.

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

The included trial was a parallel, double‐blind placebo‐controlled multicentre trial with 266 study sites in the USA (Nissen 2016). The trial was funded by Orexigen Therapeutics Inc. and Takeda Pharmaceuticals International.

Participants and duration

The trial involved 8910 obese or overweight people aged at least 45 years (men) or 50 years (women), with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events. Results for the subgroup of participants with hypertension were provided by the authors upon request. The hypertensive subgroup included 8287 participants (93% of the total study population), with a mean age of 62 years, a mean baseline systolic BP of 126 mm Hg and a mean baseline diastolic BP of 75 mm Hg. About 97% of the included participants were taking antihypertensive medication. Among the hypertensive subgroup, about 87% of the participants had diabetes mellitus type 2 and about 30% had cardiovascular disease. The median duration of follow‐up was 121 weeks (interquartile range,114 to 128 weeks).

Interventions

The participants received either a fixed‐dose combination of naltrexone (8 mg) and bupropion (90 mg) or placebo once or twice a day. During an initial four‐week titration period, the number of tablets were increased weekly (one tablet a day during the first week, two tablets a day during week two, three tablets a day during week three, and four tablets a day during week four and thereafter). All participants also received an internet‐based weight management programme focused on healthy eating and physical activity.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality was reported as an additional outcome. Cardiovascular death, fatal or nonfatal stroke, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction were reported as primary and secondary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

The study described the mean change in systolic and diastolic BP and the mean change in body weight.

Excluded studies

Full‐text evaluation in the study selection process of this review resulted in the exclusion of 124 studies (203 publications/records). The main reason for exclusion was a lack of data for the hypertensive subgroup in studies including normotensive as well as hypertensive participants. Other reasons for exclusion were not describing a randomised controlled trial, not including participants with essential hypertension, having a duration of intervention of less than 24 weeks, or including different accompanying antihypertensive therapies in the study groups. We provide reasons for excluding each trial in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

The judgements of the risk of bias for all included studies are shown in the 'Risk of bias' summary figures (Figure 2; Figure 3). For details see the 'Risk of bias' tables in Characteristics of included studies. The following provides a brief overview.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Orlistat versus placebo

All included studies were randomised controlled trials involving randomised individuals. For method of randomisation, we judged three trials (Cocco 2005; Guy‐Grand 2004; XENDOS 2001‐2006) to have a low risk of bias based on the information from journal publications or the IQWIG report (IQWiG 2006). In one study the method of randomisation was not reported and therefore unclear (Bakris 2002). The method of allocation concealment was adequate in two studies (Guy‐Grand 2004; XENDOS 2001‐2006), while it was unclear in the other two studies (Bakris 2002; Cocco 2005).

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

The included study adequately described the method of randomisation and concealment (CONQUER 2013).

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

The study adequately described the method of randomisation and concealment (Nissen 2016).

Blinding

Orlistat versus placebo

While all included trials were described as double‐blind, three trials provided too little information, and the blinding of participants and key study personnel was uncertain (Bakris 2002; Cocco 2005; Guy‐Grand 2004). Based on the authors' information, we can only assume that blinding took place throughout the duration of one study (Cocco 2005).

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

The included study was described as double‐blind. The investigators, participants, and study sponsors were masked to treatment assignment, and all study drugs were administered as capsules that were identical in size and appearance (CONQUER 2013).

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

The included study was described as double‐blind. The investigators and participants were masked to treatment assignment. A blinded independent clinical events committee adjudicated clinical outcomes, including cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, hospitalisation for unstable angina, and all‐cause mortality (Nissen 2016).

Incomplete outcome data

Orlistat versus placebo

In two studies, the outcome data description was complete for total mortality, adverse events, change in blood pressure and change in body weight: Cocco 2005 had no losses to follow‐up, and Bakris 2002 described all reasons for withdrawals and losses to follow‐up. Cardiovascular morbidity was reported only in the context of adverse events in these two RCTs, so the completeness of the information is unclear. For this endpoint we judged the risk of bias to be high.

In Guy‐Grand 2004, withdrawals were only reported for the whole study population and not for the hypertensive subgroup, and in XENDOS 2001‐2006 the reasons for withdrawals were incompletely reported. We rated the risk of bias for these two studies as unclear for all reported outcomes. Cardiovascular morbidity was reported only in the context of adverse events in the XENDOS 2001‐2006, so the completeness of the information is unclear. For this endpoint we judged the risk of bias to be high.

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

The total number of withdrawals was only reported for the whole study population and not for the hypertensive subgroup of the study (CONQUER 2013). For the hypertensive subgroup, only the number of withdrawals due to adverse events was reported, so the reasons for withdrawals were incompletely reported. We therefore judged the risk of bias to be unclear for all reported outcomes, except for cardiovascular morbidity. Cardiovascular morbidity was reported only in the context of treatment‐emergent adverse events, so the completeness of the information is unclear. For this endpoint we judged the risk of bias to be high.

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

All primary analyses were performed for the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, defined as participants who underwent randomisation into the treatment period and were dispensed study medication. No imputation was performed for missing data. The number of withdrawals and reasons were only reported for the whole study population, but not for the subset of participants with hypertension (Nissen 2016).

Selective reporting

Orlistat versus placebo

As either no study protocol was provided (Bakris 2002; Cocco 2005; Guy‐Grand 2004), or no full publication was obtainable (XENDOS 2001‐2006), or more outcomes were reported than were prespecified (Bakris 2002), we classified the risk of bias for selective reporting as uncertain for all studies.

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

No study protocol was available for CONQUER 2013. We therefore classified the risk of bias for selective reporting as uncertain.

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

A study protocol was provided and all prespecified outcomes were reported. The study was terminated prematurely after the unplanned release of the 25% interim data, which was judged as compromising the scientific integrity of the ongoing study. Outcome measures data based on the 50% interim analysis were designated as the primary analysis. Safety data were based on all available data at the time of database lock, which occurred after the 50% interim analysis (Nissen 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

Orlistat versus placebo

No trial included in the review reported any significant differences between groups in the main characteristics of participants at baseline. However, in Bakris 2002 and XENDOS 2001‐2006, the combination of a high withdrawal rate and the unknown length of involvement of participants in the trial increases the risk of bias, even when last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis is used. In addition, within Bakris 2002 there were inconsistencies between the text and flowchart for numbers of participants who finished the study.

Phentermine/topiramate versus placebo

We could identify no other potential source of bias in the included study (CONQUER 2013).

Naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo

There were no significance differences between groups in the main characteristics of participants at baseline. There was an increased risk of bias because of very high withdrawal rates (84% and 94%, respectively), without imputation for missing data (Nissen 2016).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

1. Orlistat versus placebo

See: Table 1.

Primary outcomes

For details on primary outcome data see Table 7 and Table 8.

4. Adverse events (I).

| Study | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Randomised/Safety (N) | Death (n (%)) | All adverse events (n (%)) | Leading to withdrawal (n (%)) | Serious adverse events (n (%)) |

| Orlistat vs placebo | ||||||

| Bakris 2002 | Orlistat | 278/268a | 0 (0) | 239 (89) | 18 (6.7) | 31 (11.7) |

| Placebo | 276/274a | 0 (0) | 195 (71) | 20 (7.3) | 24 (8.6) | |

| Cocco 2005 | Orlistat | 45/45 | 0 (0) | nr | nr | 0 (0) |

| Placebo | 45/45 | 0 (0) | nr | nr | 0 (0) | |

| Guy‐Grand 2004 | Orlistat | 304/304 | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Placebo | 310/310 | nr | nr | nr | nr | |

| XENDOS 2001‐2006 | Orlistat (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [OD] | 408/407 | 2 (0.5) | 403 (99) | 37 (9) | 73 (18) |

| Orlistat (SBP ≥ 140mm Hg) [OS] | 516/513 | 1 (0.2) | 508 (99) | 46 (9) | 92 (18) | |

| Placebo (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [PD] | 441/437 | 0 (0) | 420 (96) | 17 (4) | 52 (12) | |

| Placebo (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [PS] | 509/508 | 0 (0) | 493 (97) | 20 (4) | 60 (12) | |

| Phentermine/topiramate vs placebo | ||||||

| CONQUER 2013 | Phen/Top [LD] | 261/261 | 0 (0) | 223 (85.4) | 31 (11.9) | 9 (3.4) |

| Phen/Top [HD] | 520/520 | 0 (0) | 462 (88.8) | 103 (19.8) | 19 (3.7) | |

| Placebo | 524/524 | 0 (0) | 405 (77.3) | 51 (9.7) | 22 (4.2) | |

| Naltrexone/bupropion vs placebo | ||||||

| Nissen 2016 | Nal/Bup | 4164/4164 | 63 (1.5) / P = 0.916 | 1796 (43.1) / P < 0.001 | 1273 (30.6) / P < 0.001 | 891 (21.4) / P = 0.297 |

| Placebo | 4119/4119 | 63 (1,5) | 1053 (25.6) | 379 (9.2) | 843 (20.5) | |

aCalculated from percentage rates

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; nr: not reported; [OD]: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [OS]: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; Phen/Top [HD]: phentermine/topiramate high dose (15 mg/92 mg); Phen/Top [LD]: phentermine/topiramate low dose (7.5 mg/46 mg); [PD]: placebo and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [PS]: placebo and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; SBD: systolic blood pressure.

5. Adverse events (II).

| Study | Intervention(s) and comparator(s) | Randomised/Safety /N) | Gastrointestinal AE (n (%)) | Musculoskeletal AE (n (%)) | Dermatological AE (n (%)) | Vascular AE (n (%)) | Cardiac AE (n (%)) | Nervous system AE (n (%)) | Respiratory AE (n (%)) |

| Orlistat vs placebo | |||||||||

| Bakris 2002 | Orlistat | 278/nr | 200 (72.5) | nr (22.8) | nr | nr | 5 (nr)a | nr | nr |

| Placebo | 276/nr | 120 (43.6) | nr (15.5) | nr | nr | 5 (nr)a | nr | nr | |

| Cocco 2005 | Orlistat | 45/45 | 16 (35.6)b | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Placebo | 45/45 | 11 (24.4)b | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | |

| Guy‐Grand 2004 | Orlistat | 304/304 | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr |

| Placebo | 310/310 | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | nr | |

| XENDOS 2001‐2006 | Orlistat (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [OD] | 408/407 | 379 (93) | 265 (65) | 81 (20) | 69 (17) | nr | 159 (39) | nr |

| Orlistat (SBP ≥ 140mm Hg) [OS] | 516/513 | 477 (93) | 333 (65) | 113 (22) | 87 (17) | nr | 205 (40) | nr | |

| Placebo (DBP ≥ 90 mm Hg) [PD] | 441/437 | 306 (70) | 271 (62) | 74 (17) | 83 (19) | nr | 170 (39) | nr | |

| Placebo (SBP ≥ 140 mm Hg) [PS] | 509/508 | 361 (71) | 320 (63) | 86 (17) | 97 (19) | nr | 188 (37) | nr | |

| Phentermine/topiramate vs placebo | |||||||||

| CONQUER 2013 | Phen/Top [LD] | 261/261 | Constipation: 41 (15.7) | nr | nr | nr | 6 (2.3) | Dry mouth: 37 (14.2) Paresthesia: 37 (14.2) Dysgeusia: 20 (7.7) Insomnia: 15 (5.7) Headache: 13 (5.0) Dizziness: 17 (6.5) |

Upper respiratory tract infection: 33 (12.6) Nasopharyngitis: 27 (10.3) Sinusitis: 14 (5.4) |

| Phen/Top [HD] | 520/520 | Constipation: 94 (18.1) | nr | nr | nr | 19 (3.7) | Dry mouth: 118 (22.7) Paresthesia: 116 (22.3) Dysgeusia: 57 (11.0) Insomnia: 57 (11.0) Headache: 56 (10.8) Dizziness: 63 (12.1) |

Upper respiratory tract infection: 63 (12.1) Nasopharyngitis: 53 (10.2) Sinusitis: 43 (8.3) |

|

| Placebo | 524/524 | Constipation: 29 (5.5) | nr | nr | nr | 9 (1.7) | Dry mouth: 12 (2.3) Paresthesia: 12 (2.3) Dysgeusia: 4 (0.8) Insomnia: 25 (4.8) Headache: 44 (8.4) Dizziness: 16 (3.1) |

Upper respiratory tract infection: 62 (11.8) Nasopharyngitis: 46 (8.8) Sinusitis: 34 (6.5) |

|

| Naltrexone/bupropion vs placebo | |||||||||

| Nissen 2016 | Nal/Bup | 4164/4164 | 718 (17.2) / P < 0.001 | 181 (4.3) / P = 0.749 | 45 (1.1) / P = 0.002 | 158 (3.8)c / P = 0.978 | 313 (7.5) / P < 0.001 | 74 (1.8) / P = 0.947 | |

| Placebo | 4119/4119 | 142 (3.4) | 185 (4.5) | 20 (0.5) | 155 (3.8)c | 111 (2.7) | 74 (1.8) | ||

aOnly serious cardiac events. bNo data on adverse events were reported for the whole study duration. The data above refer to 4 and 3 weeks of treatment in the orlistat and placebo group, respectively. After 3 months, the number of participants with events decreased to 5 (11%) [O] with flatulence and mild abdominal cramps versus 6 (13%) [P] with nausea and hunger feeling. c Major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, non‐fatal stroke, non‐fatal myocardial infarction) + hospitalisation for unstable angina.

AE: adverse events; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; nr: not reported; [OD]: orlistat and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [OS]: orlistat and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; Phen/Top [HD]: phentermine/topiramate high dose (15 mg/92 mg); Phen/Top [LD]: phentermine/topiramate low dose (7.5 mg/46 mg); [PD]: placebo and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg; [PS]: placebo and systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg; SBD: systolic blood pressure.

Total mortality

Three of four studies reported on mortality. No deaths were reported in either Bakris 2002 or Cocco 2005. In XENDOS 2001‐2006, there were two deaths in the orlistat‐treated group in the first subgroup analysis (diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg) and one death in the orlistat group in the second subgroup analysis (systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg); no deaths occurred in the placebo group.

Cardiovascular morbidity

Three studies presented data on cardiovascular morbidity. In Bakris 2002, two participants in the orlistat group suffered a myocardial infarction, two had chest pain, and one had an episode of atrial fibrillation. In the placebo group, one participant had a myocardial infarction, one had worsening atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, and two had an episode of chest pain. Cocco 2005 reported that in participants with resting left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) below 50% at baseline, LVEF did not change with placebo (0.6%), but was increased by 4.3% in the orlistat group (P < 0.001). In XENDOS 2001‐2006, vascular complications were reported in the context of adverse events. In both subgroups (diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg and systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg), 17% of the participants treated with orlistat and 19% treated with placebo reported a vascular adverse event.

Adverse events

Data on serious adverse events (SAEs) were available from three trials (Bakris 2002; Cocco 2005; XENDOS 2001‐2006), with significantly more SAEs in participants treated with orlistat compared to those who received placebo: RR 1.45 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.91; 3 trials, 1476 participants; Analysis 1.1). Overall adverse events were reported in two RCTs (Bakris 2002; XENDOS 2001‐2006), with no significant difference between the orlistat and the placebo group: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.54; 2 trials, 1386 participants; Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Orlistat versus placebo, Outcome 1: Serious adverse events

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Orlistat versus placebo, Outcome 2: All adverse events

Bakris 2002: At least one adverse event was reported by significantly more participants in the orlistat‐treated group (89%) than in the placebo‐treated group (71%), with a P value < 0.001. Of those, 7% of participants in the orlistat group versus 7% of participants in the placebo group withdrew. Twelve per cent of all adverse events in the orlistat‐treated group versus 9% in the placebo‐treated group were classified as serious adverse events, and none was classified as being related to study medication. Gastrointestinal side effects were significantly higher in the orlistat‐treated group than in the placebo group (73% versus 44%; P < 0.001); 8% of those participants in the orlistat group and 5% in the placebo group stopped taking the medication for this reason. Musculoskeletal side effects were also reported significantly more often in the orlistat versus the placebo group (23% versus 16%; P < 0.05).

Cocco 2005: As reported by the authors, side effects were mild. No overall adverse events were reported. Gastrointestinal side effects were the most common adverse events and were described for 24% of the placebo group within the first three weeks and for 36% of the orlistat group within the first four weeks.

Guy‐Grand 2004: Data were only presented for the whole study group, with no information provided on the hypertensive subgroup.

XENDOS 2001‐2006: First subgroup (diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg): Side effects were reported in 99% of participants in the orlistat and 96% of participants in the placebo group. Eighteen per cent of participants in the orlistat group and 12% of participants in the placebo group experienced severe adverse events. Gastrointestinal side effects were more common in the orlistat (93%) versus the placebo group (70%). Musculoskeletal, nervous, dermatological, and vascular events were comparable in both treatment groups. Nine per cent withdrew due to side effects in the orlistat versus 4% in the placebo group, but it is not clear whether the reported side effects were study drug‐related. Second subgroup (systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg): Side effects were reported in 99% of participants in the orlistat and 97% of participants in the placebo group. Eighteen per cent of participants in the orlistat group and 12% of participants in the placebo group experienced severe adverse events. Gastrointestinal side effects were more common in the orlistat (93%) versus the placebo group (71%). Musculoskeletal, nervous, dermatological, and vascular events were comparable in both treatment groups. Nine per cent withdrew due to side effects in the orlistat versus 4% in the placebo group. It is not clear whether the reported side effects were study drug‐related.

Secondary outcomes