Abstract

Background

Treatment with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) is used to reduce proteinuria and retard the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, resolution of proteinuria may be incomplete with these therapies and the addition of an aldosterone antagonist may be added to further prevent progression of CKD. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2009 and updated in 2014.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of aldosterone antagonists (selective (eplerenone), non‐selective (spironolactone or canrenone), or non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists (finerenone)) in adults who have CKD with proteinuria (nephrotic and non‐nephrotic range) on: patient‐centred endpoints including kidney failure (previously know as end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD)), major cardiovascular events, and death (any cause); kidney function (proteinuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and doubling of serum creatinine); blood pressure; and adverse events (including hyperkalaemia, acute kidney injury, and gynaecomastia).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 13 January 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal, and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared aldosterone antagonists in combination with ACEi or ARB (or both) to other anti‐hypertensive strategies or placebo in participants with proteinuric CKD.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study quality and extracted data. Data were summarised using random effects meta‐analysis. We expressed summary treatment estimates as a risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes, or standardised mean difference (SMD) when different scales were used together with their 95% confidence interval (CI). Risk of bias were assessed using the Cochrane tool. Evidence certainty was evaluated using GRADE.

Main results

Forty‐four studies (5745 participants) were included. Risk of bias in the evaluated methodological domains were unclear or high risk in most studies. Adequate random sequence generation was present in 12 studies, allocation concealment in five studies, blinding of participant and investigators in 18 studies, blinding of outcome assessment in 15 studies, and complete outcome reporting in 24 studies.

All studies comparing aldosterone antagonists to placebo or standard care were used in addition to an ACEi or ARB (or both). None of the studies were powered to detect differences in patient‐level outcomes including kidney failure, major cardiovascular events or death.

Aldosterone antagonists had uncertain effects on kidney failure (2 studies, 84 participants: RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.33 to 27.65, I² = 0%; very low certainty evidence), death (3 studies, 421 participants: RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.10 to 3.50, I² = 0%; low certainty evidence), and cardiovascular events (3 studies, 1067 participants: RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.56; I² = 42%; low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or standard care. Aldosterone antagonists may reduce protein excretion (14 studies, 1193 participants: SMD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.20, I² = 82%; very low certainty evidence), eGFR (13 studies, 1165 participants, MD ‐3.00 mL/min/1.73 m², 95% CI ‐5.51 to ‐0.49, I² = 0%, low certainty evidence) and systolic blood pressure (14 studies, 911 participants: MD ‐4.98 mmHg, 95% CI ‐8.22 to ‐1.75, I² = 87%; very low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or standard care.

Aldosterone antagonists probably increase the risk of hyperkalaemia (17 studies, 3001 participants: RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.22, I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence), acute kidney injury (5 studies, 1446 participants: RR 2.04, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.97, I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence), and gynaecomastia (4 studies, 281 participants: RR 5.14, 95% CI 1.14 to 23.23, I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence) compared to placebo or standard care.

Non‐selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB had uncertain effects on protein excretion (2 studies, 139 participants: SMD ‐1.59, 95% CI ‐3.80 to 0.62, I² = 93%; very low certainty evidence) but may increase serum potassium (2 studies, 121 participants: MD 0.31 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.45, I² = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared to diuretics plus ACEi or ARB. Selective aldosterone antagonists may increase the risk of hyperkalaemia (2 studies, 500 participants: RR 1.62, 95% CI 0.66 to 3.95, I² = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared ACEi or ARB (or both). There were insufficient studies to perform meta‐analyses for the comparison between non‐selective aldosterone antagonists and calcium channel blockers, selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB (or both) and nitrate plus ACEi or ARB (or both), and non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists and selective aldosterone antagonists.

Authors' conclusions

The effects of aldosterone antagonists when added to ACEi or ARB (or both) on the risks of death, major cardiovascular events, and kidney failure in people with proteinuric CKD are uncertain. Aldosterone antagonists may reduce proteinuria, eGFR, and systolic blood pressure in adults who have mild to moderate CKD but may increase the risk of hyperkalaemia, acute kidney injury and gynaecomastia when added to ACEi and/or ARB.

Plain language summary

Aldosterone antagonists in addition to renin angiotensin system antagonists for preventing the progression of chronic kidney disease

What is the issue?

People who have chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a higher risk of heart disease and declining kidney function. Increased amounts of protein in the urine is a sign of kidney stress and is linked to declining kidney function. Medications used to lower blood pressure and reduce protein levels in the urine ‐ in particular, angiotensin‐converting enzyme Inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) ‐remain the core treatment to prevent the declining of kidney function in CKD.

Protecting kidney function with these medications may however be incomplete and adding an aldosterone antagonist (blocker) (for example, spironolactone, canrenone, eplerenone, or finerenone) may better protect kidney function in the long‐term. By blocking the production of aldosterone, the kidneys excrete more water which can lead to a lowering of blood pressure. However, they can cause side effects including enlargement of male breast tissue, and when used with ACEi or ARBs may cause high levels of potassium in the blood or a decline in kidney function.

What did we do? We reviewed the available studies looking at the addition of aldosterone blockers to standard treatment in people with CKD to see if they slowed the decline of kidney function and the subsequent need for dialysis or a kidney transplant. We looked at whether they reduced heart disease, the amount of protein in urine, or improved blood pressure. We also looked at whether aldosterone blockers were safe in terms of risks of male breast enlargement, potassium levels in the blood, and short‐term effects on kidney function.

What did we find? We found that adding aldosterone blockers to a patient's current medications (ACEi or ARBs), lowered both protein in the urine and systolic blood pressure. Kidney function declined, however the effects on survival were uncertain. The addition of aldosterone blockers increased the amount of potassium in the blood. This may require medication changes, extra blood tests, and may be potentially harmful. Treatment with aldosterone blockers also increased the chance of short‐term decline in kidney function and enlargement of male breast tissue.

Conclusions It is unclear as to whether aldosterone blockers protect kidney function or prevent heart disease in people who have CKD.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has a global prevalence of 10% to 12% and progression to kidney failure (previously known as end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD)) is rising due to the global diabetes and hypertension pandemics (Mills 2015; Nugent 2011). There is a significant associated economic burden to patients, caregivers, and society, which increases throughout disease progression (Wang 2016). Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) are the standard of care to slow progression of CKD and reduce incidence of kidney failure in patients with proteinuria irrespective of primary kidney disease (Jafar 2001; Strippoli 2006) because they lower proteinuria and blood pressure, which are both independent predictors of death in adults with CKD (Brenner 2001; GISEN 1997; Mathiesen 1999). However, ACEi or ARB slow, but may not completely retard, the progression of CKD (Schieppati 2003).

Description of the intervention

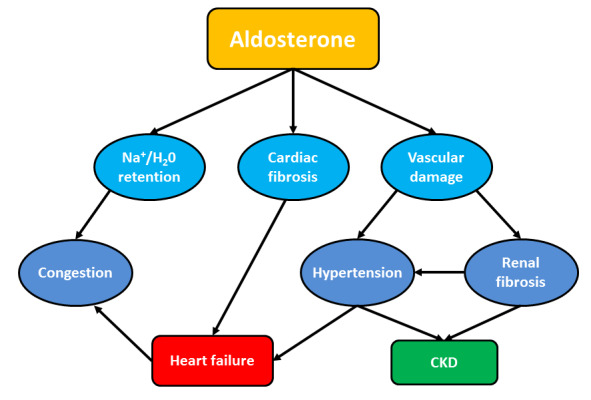

Animal studies have shown that aldosterone has an independent role in the development of hypertensive kidney disease and vascular injury resulting in myocardial and renal fibrosis (Figure 1), and exacerbates glomerulosclerosis resulting in severe proteinuria (Bomback 2007), which is reduced with aldosterone blockade (Aldigier 2005; Green 1996; Rocha 1998; Silvestre 1998). Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system blockade with ACEi or ARB result in incomplete suppression of serum aldosterone levels and is known as the 'aldosterone escape phenomenon' (Staessen 1981). Further experimental studies have established this theory and in humans, the treatment of adults with CKD exhibiting aldosterone escape phenomenon with aldosterone antagonists reduces proteinuria (Fritsch Neves 2003). However, aldosterone antagonism may increase risks of hyperkalaemia and gynaecomastia (Nappi 2011). Novel non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists such as finerenone are more selective for the mineralocorticoid receptor than other steroid receptors including the glucocorticoid receptor, androgen receptor and progesterone receptor (Bramlage 2016) and may provide similar efficacy as non‐selective aldosterone antagonist but improved safety profile.

1.

Mechanisms of cardiac and kidney damage induced by aldosterone excess

How the intervention might work

Multiple aldosterone‐mediated mechanisms have been shown to contribute to renal vascular injury and fibrosis in animal studies. These include aldosterone‐mediated increases in plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 (PAI‐1) which inhibits the fibrinolytic system and activates latent growth factors; up‐regulation of transforming growth factor‐b and associated fibroblast differentiation, up‐regulation of collagen synthesis and down regulation of matrix metalloproteinase collagenase; generation of oxygen‐free radicals and hydrogen peroxide; and up regulation of endothelin‐1 with resultant vasoconstriction (Hollenberg 2004). However, a common pathway is yet to be clearly defined. In a rat model, renal radiation injury resulted in an eight‐fold increase in the expression of PAI‐1 messenger RNA (mRNA) and non‐selective aldosterone blockade (spironolactone) significantly decreased PAI‐1 mRNA expression, development of glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria (Brown 2000). In human studies, beneficial effects of aldosterone blockade (non‐selective and selective) have been established in congestive cardiac failure (Hostetter 2003; Pitt 1999; Pitt 2003) and proteinuric CKD (Bianchi 2006; Chrysostomou 2006; Epstein 2006; Rossing 2005; Schjoedt 2005). In animal studies, finerenone had a more potent natriuretic response than eplerenone but no impact on urinary potassium levels (Kolkhof 2014). Therefore, it is hypothesised that non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists will exhibit the benefits of aldosterone blockade without the risk of hyperkalaemia.

Why it is important to do this review

Aldosterone blockade in combination with ACEi or ARB may reduce proteinuria but their effects on patient‐level outcomes such as kidney failure requiring dialysis or kidney transplantation or major cardiovascular events and their safety in regards to risk of hyperkalaemia and acute kidney injury, particularly in adults who have coexisting CKD, remain uncertain. Thus, we analysed the benefits and harms of aldosterone antagonists in adults who had CKD and who were or who were not already treated with ACEi or ARB (or in combination). We specifically focused on treatment effects for patient‐level outcomes including kidney failure and major cardiovascular events, proteinuria, and kidney function. New relevant studies on CKD patients receiving aldosterone antagonists, including non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists, have recently been completed and their inclusion to update the previous published versions of this review (Bolignano 2014; Navaneethan 2009) would be valuable.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of aldosterone antagonists (selective (eplerenone), non‐selective (spironolactone), and non‐steroidal (finerenone)) in combination with ACEi or ARB in adults who have CKD with proteinuria (nephrotic and non‐nephrotic range) on:

Patient‐centred endpoints including kidney failure, major cardiovascular events, and death (any cause)

Kidney function (proteinuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and doubling of serum creatinine (SCr)

Adverse events (including hyperkalaemia, acute kidney injury, and gynaecomastia).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and quasi‐RCTs of aldosterone antagonists used in combination with ACEi or ARB (or both) were included. Data from the first period of randomised cross‐over studies was also included.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Studies enrolling participants with CKD stages 1 to 4, as defined by the by Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K‐DOQI) guidelines (Levey 2003) and who had albuminuria or proteinuria were considered for inclusion. We included studies in adults who had CKD regardless of aetiology. The K/DOQI categories for kidney disease are as follows.

CKD stage 1: eGFR > 90 mL/min/1.73 m² and evidence of clinically relevant structural or urinary abnormalities including haematuria or proteinuria (or both)

CKD stage 2: eGFR 60 to 89 mL/min/1.73 m²

CKD stage 3: eGFR 30 to 59 mL/1.73 m²

CKD stage 4: eGFR 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m².

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies in adults on dialysis, recipients of a kidney transplant, participants without evidence of CKD or proteinuria, studies less than 4 weeks of duration, and studies not evaluating any outcome of interest.

Types of interventions

We included studies evaluating aldosterone antagonist treatment given in combination with an ACEi or ARB (or both). We considered studies in which treatment duration was 4 weeks or longer. If any studies compared aldosterone antagonists alone (i.e. no additional RAS antagonists), these studies were also included,

We considered the following treatment comparisons.

Aldosterone antagonists with RAS antagonists versus placebo or standard care

Aldosterone antagonist with RAS antagonists versus diuretic plus ACEi or ARB

Non‐selective aldosterone antagonist with RAS antagonists versus calcium channel blocker

Selective aldosterone antagonist with RAS antagonists versus ACEi or ARB (or both)

Selective aldosterone antagonist with RAS antagonists versus ACEi or ARB (or both) versus ACEi or ARB (or both) plus nitrate

Selective aldosterone antagonist with RAS antagonists versus non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonist.

If disaggregated outcome data were not available for the three groups (ACEi alone, ARB alone or the combination separately), we used combined data when available.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Kidney failure (defined as permanent worsening in eGFR requiring kidney replacement therapy)

Hyperkalaemia (defined as serum potassium > 5.0 mEq/L or mmol/L)

Secondary outcomes

Death (any cause)

Major cardiovascular events as defined by the investigators (including but not limited to myocardial infarction, stroke, congestive heart failure)

Urinary protein excretion rate (24‐hour proteinuria, 24‐hour albuminuria in mg/dL, urine protein:creatinine ratio, or urine albumin:creatinine ratio)

Kidney function: estimated GFR (mL/min or mL/min/1.73 m²); doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria

Blood pressure: systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)

Serum potassium

Acute kidney injury

Gynaecomastia

Fatigue

Falls

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 13 January 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals, and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review update.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of clinical practice guidelines, review articles and relevant studies.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Disagreements were resolved in consultation with two authors who also provided methodological assistance throughout the review process.

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies relevant to the review. For this update, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however, studies and reviews that may have included relevant data or information on studies were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts, and if necessary, the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data were used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a third author.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (kidney failure, death (any cause), cardiovascular events, doubling of SCr, hyperkalaemia, acute kidney injury, and gynaecomastia) results were expressed as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). When continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (end of treatment protein excretion rate or albumin excretion rate, eGFR or creatinine clearance, blood pressure, and serum potassium), we used the mean difference (MD) or the standardised mean difference (SMD) when different measurement scales were used.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to seek additional information. We were successful in obtaining additional data from Drs KJ Schjoedt, K Rossing, A Chrysostomou, S Bianchi, S Nielsen, and K Takebayashi. These data were included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol (PP) population were performed. Attrition rates, such as drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I² values was as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi² test, or a confidence interval for I²) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011) for outcomes in which sufficient data observations were available (10 or more studies) and in which there was low or no statistical heterogeneity between studies.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using random effects meta‐analysis, but the fixed effects model was also analysed to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity among participants could be related to age, stage of kidney disease, aetiology of kidney disease and amount of proteinuria. Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to prior agent(s) used and the agent (selective or non‐selective aldosterone antagonist), dose, duration of aldosterone antagonists and the concomitant use of ACEi or ARB (or both).

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables. The absolute treatment effects for dichotomous outcomes was estimated using the risk estimate and 95% CI obtained from the corresponding meta‐analysis.

Primary efficacy outcome

Kidney failure

Primary safety outcome

Hyperkalaemia

Secondary outcomes

Death (any cause)

Cardiovascular events

Doubling SCr

Acute kidney injury

Proteinuria

eGFR

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For this 2020 update a search of The Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies identified 83 reports. We identified 18 new included studies (32 reports), and four reports of two existing included studies; three new ongoing studies (four reports); 13 new excluded studies (40 reports), and two reports of two existing excluded studies. One study (one report) has been recently completed but no results have been published and is awaiting assessment.

In addition to the new reports, one previously included study has been move to excluded (Schjoedt 2006) as a proportion of the patients have been reported in two other included studies (Schjoedt 2005; Rossing 2005). Two previous ongoing studies have now been included (Abolghasmi 2011; EVALUATE 2010) and one study, while complete, is yet to publish any results and is awaiting assessment (NCT00315016). Four non‐RCTs have been removed from this update.

See Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

For this 2020 update we included 18 new studies (4248 participants) (ARTS 2012; ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2013; Chen 2018b; Esteghamati 2013; EVALUATE 2010; Fogari 2014; Hamid 2017a; Hase 2013; Horestani 2012; Ito 2019a; Kato 2015; Morales 2015; Tylicki 2012; Wang 2013g; Ziaee 2013). This brings the total number of included studies to 44 (85 reports, 5745 participants).

Ten studies were cross‐over studies (Boesby 2011; Morales 2009; Morales 2015; Nielsen 2012; Saklayen 2008; Smolen 2006; Rossing 2005; Schjoedt 2005; Tylicki 2008; Tylicki 2012).

Twenty‐three studies included participants who had kidney disease secondary to diabetes mellitus (ARTS‐DN 2015; Chen 2018b; Chrysostomou 2006; Epstein 2002; Epstein 2006; Esteghamati 2013; Fogari 2014; Hamid 2017a; Hase 2013; Horestani 2012; Ito 2019a; Kato 2015; Koroshi 2010; Mehdi 2009; Nielsen 2012; Ogawa 2006a; Rossing 2005; Saklayen 2008; Schjoedt 2005; Takebayashi 2006; van den Meiracker 2006; Zheng 2011; Ziaee 2013). Two studies included participants with heart failure with associated proteinuric CKD (ARTS 2012; ARTS‐HF 2015). The remaining studies included participants with non‐diabetic kidney disease encompassing IgA nephropathy, benign nephrosclerosis, membranous nephropathy, or idiopathic chronic glomerulonephritis (Abolghasmi 2011; Bianchi 2006; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2011; Boesby 2013; Cohen 2010; CRIBS II 2009; Furumatsu 2008; Guney 2009; Haykal 2007; Lv 2009a; Morales 2009; Morales 2015; Smolen 2006; Tokunaga 2008a; Tylicki 2008; Tylicki 2012; Wang 2013g). All studies excluded participants with an eGFR below 15 mL/min/1.73 m². For studies measuring 24‐hour urine protein or albumin, the baseline albuminuria/proteinuria excretion rates ranged from 0.15 to 3.6 g/day. Study duration varied from one to 36 months with a median duration of 3 months. Sample size of all studies was variable (range 16 to 1055) and none were powered to detect hard primary outcomes including kidney failure, death, or major cardiovascular events.

Among studies using non‐selective aldosterone antagonists, 22 studies (1441 participants) compared spironolactone plus ACEi or ARB (or both) to ACEi or ARB (or both) (Abolghasmi 2011; Bianchi 2006; Chen 2018b; Chrysostomou 2006; CRIBS II 2009; Furumatsu 2008; Guney 2009; Kato 2015; Koroshi 2010; Lv 2009a; Mehdi 2009; Nielsen 2012; Ogawa 2006a; Rossing 2005; Saklayen 2008; Schjoedt 2005; Tokunaga 2008a; Tylicki 2008; van den Meiracker 2006; Wang 2013g; Zheng 2011; Ziaee 2013). Five studies (220 participants) compared spironolactone plus ACEi or ARB to diuretics plus ACEi or ARB (Hamid 2017a; Hase 2013, Horestani 2012; Morales 2015; Smolen 2006); one study (37 participants) compared spironolactone to calcium channel blockers (Takebayashi 2006); one study (136 participants) compared spironolactone plus ARB to ACEi plus ARB (Esteghamati 2013); one study (120 participants) compared canrenone plus ARB and calcium channel blockers to hydrochlorothiazide plus ARB and calcium channel blockers (Fogari 2014); and one study (128 participants) compared spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB to ACEi (Bianchi 2010). In the studies that analysed the efficacy of non‐selective aldosterone antagonists, 25 mg/day of spironolactone was used throughout the study period except for Abolghasmi 2011, Saklayen 2008 and van den Meiracker 2006 who used 25 to 50 mg/day. Chen 2018b, Lv 2009a, Wang 2013g and Zheng 2011 used 20 mg/day; Horestani 2012, Koroshi 2010and Takebayashi 2006 used 50 mg/day; Mehdi 2009 used 12.5 to 25 mg/day of spironolactone; and Bianchi 2010 used 25 mg three times/week to 50 mg/day of spironolactone. Fogari 2014 used 25 mg/day of canrenone. In Hamid 2017a, the dose of spironolactone was not defined.

Six studies (925 participants) compared the selective aldosterone antagonist eplerenone plus ACEi or ARB (or both) to ACEi or ARB (or both) (Boesby 2011; Haykal 2007; Epstein 2002; Epstein 2006; EVALUATE 2010; Tylicki 2012). One study (34 participants) compared eplerenone plus ACEi or ARB (or both) to ACEi or ARB (or both) and to ACEi or ARB (or both) plus nitrate (Cohen 2010), and one study (54 participants) compared the selective aldosterone antagonist eplerenone to placebo (Boesby 2013). Studies that analysed the efficacy of selective aldosterone antagonists used eplerenone at the dose of 200 mg/day (Epstein 2002), 50 to 100 mg/day (Epstein 2006), 25 to 50 mg/day (Boesby 2011; Boesby 2013; Haykal 2007), and 50 mg/day (EVALUATE 2010; Tylicki 2012). In Cohen 2010 the dose of eplerenone administered was not defined.

One cross‐over study (12 participants) compared eplerenone alone (25 mg/day) to ACEi alone (20 mg/day) or ACEi (10 mg/day) plus ARB (16 mg/day) (Morales 2009).

Among studies using non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists, one study (821 participants) compared finerenone to placebo (ARTS‐DN 2015), one study (392 participants) compared finerenone to placebo or spironolactone (ARTS 2012), one study (1055 participants) compared finerenone to eplerenone (ARTS‐HF 2015), and one study (358 participants) compared esaxerenone to placebo (Ito 2019a). Studies that analysed the efficacy of non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists used finerenone at the dose of 2.5 to 10 mg/day (ARTS 2012), 1.25 to 25 mg/day (ARTS‐DN 2015), 5 to 20 mg/day (ARTS‐HF 2015), and esaxerenone 0.625 to 5 mg/day (Ito 2019a). Other characteristics of the participants and the interventions of the included studies are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐seven studies (61 reports) were excluded because; they did not include adults with CKD (17 studies); were not studies comparing aldosterone antagonists with or without ACEi or ARB (3); were of short duration (1); included participants already reported in other included studies (1); were terminated early with no reported outcomes (1); or they did not examine outcomes of interest (e.g. pharmacokinetic studies) (1). One study was retracted (1).

For this 2020 update, non‐RCTs have been deleted.

Risk of bias in included studies

Risks of bias in the available studies are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation was judged to be at low risk of bias in 12 studies (ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Bianchi 2006; Chen 2018b; EVALUATE 2010; Mehdi 2009; Morales 2015; Nielsen 2012; Schjoedt 2005; Tylicki 2008; Tylicki 2012; van den Meiracker 2006) and unclear in the remaining 32 studies.

Allocation concealment was judged to be at low risk in five studies (ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Boesby 2011; Chrysostomou 2006; EVALUATE 2010), one study was judged to be a high risk of bias (Bianchi 2010), and unclear in the remaining 38 studies.

Blinding

Participants and investigators were blinded in 18 studies (Abolghasmi 2011; ARTS 2012; ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Chrysostomou 2006; CRIBS II 2009; Epstein 2002; Epstein 2006; EVALUATE 2010; Kato 2015; Lv 2009a; Mehdi 2009; Nielsen 2012; Rossing 2005; Saklayen 2008; Schjoedt 2005; Tylicki 2012; van den Meiracker 2006) and not blinded in 13 studies (Bianchi 2006; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2011; Boesby 2013; Chen 2018b; Esteghamati 2013; Fogari 2014; Furumatsu 2008; Hase 2013; Morales 2009; Tokunaga 2008a; Tylicki 2008; Wang 2013g); blinding was unclear in the remaining 13 studies.

Outcome assessors were not aware of treatment allocation or outcomes were unlikely influenced by treatment allocation in 15 studies (ARTS‐DN 2015; Boesby 2013; CRIBS II 2009; Epstein 2006; Esteghamati 2013; EVALUATE 2010; Fogari 2014; Furumatsu 2008; Guney 2009; Morales 2009; Morales 2015; Nielsen 2012; Saklayen 2008; Smolen 2006; Zheng 2011). Blinding of outcome assessors was unclear in the remaining 29 studies.

Incomplete outcome data

Twenty‐four studies were judged to be at low risk of bias (Abolghasmi 2011; ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Bianchi 2006; Boesby 2011; Chrysostomou 2006; Cohen 2010; CRIBS II 2009; Epstein 2006; EVALUATE 2010; Fogari 2014; Furumatsu 2008; Hase 2013; Haykal 2007; Kato 2015; Morales 2009; Nielsen 2012; Rossing 2005; Saklayen 2008; Schjoedt 2005; Takebayashi 2006; Tylicki 2008; Tylicki 2012; Zheng 2011). Seven studies where there was some loss to follow‐up (ARTS‐DN 2015; Bianchi 2006; Boesby 2011; Chen 2018b; Epstein 2006; Cohen 2010; CRIBS II 2009) were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis. Ten studies were judged to be at high risk of bias (ARTS 2012; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2013; Chen 2018b; Esteghamati 2013; Guney 2009; Ito 2019a; Mehdi 2009; Morales 2015; van den Meiracker 2006). The dropout rate from study follow‐up ranged from 0% to 37% and did not differ between the treatment and control groups.

Selective reporting

All the pre‐specified outcomes and all relevant outcomes were reported in 18 studies (ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Bianchi 2006; Chen 2018b; Chrysostomou 2006; Epstein 2006; Esteghamati 2013; EVALUATE 2010; Fogari 2014; Furumatsu 2008; Guney 2009; Hase 2013; Kato 2015; Lv 2009a; Mehdi 2009; Tokunaga 2008a; Tylicki 2008; Tylicki 2012). Selective reporting was judged to be at high risk of bias in 23 studies (Abolghasmi 2011; Bianchi 2006; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2011; CRIBS II 2009; Epstein 2002; Hamid 2017a; Haykal 2007; Ito 2019a; Koroshi 2010; Morales 2009; Morales 2015; Nielsen 2012; Ogawa 2006a; Rossing 2005; Saklayen 2008; Schjoedt 2005; Smolen 2006; Takebayashi 2006; van den Meiracker 2006; Wang 2013g; Zheng 2011; Ziaee 2013), and unclear in the remaining three studies.

Other potential sources of bias

Eighteen studies were judged to be at low risk of bias due to funding (Bianchi 2006; Bianchi 2010; Boesby 2011; Boesby 2013; Chrysostomou 2006; CRIBS II 2009; Fogari 2014; Furumatsu 2008; Guney 2009; Hase 2013; Mehdi 2009; Morales 2015; Nielsen 2012; Rossing 2005; Schjoedt 2005; Tylicki 2008; van den Meiracker 2006; Ziaee 2013); six studies were funded by a pharmaceutical company (ARTS 2012; ARTS‐DN 2015; ARTS‐HF 2015; Epstein 2006; EVALUATE 2010; Ito 2019a;); one study excluded participants after randomisation due change in treatment (Horestani 2012) and the risk of bias was unclear in the remaining 19 studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6

Summary of findings 1. Aldosterone antagonists versus placebo or standard care for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo or standard care for proteinuric CKD | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric CKD Intervention: aldosterone antagonist Comparison: placebo or standard care | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with placebo or standard care | Risk with aldosterone antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | 0 per 1,000 | 0 per 1,000 (0 to 0) | RR 3.00 (0.33 to 27.65) | 84 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2 |

| Hyperkalaemia | 25 per 1,000 | 55 per 1,000 (37 to 81) | RR 2.17 (1.47 to 3.22) | 3001 (17) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 |

| Death | 14 per 1,000 | 8 per 1,000 (1 to 50) | RR 0.58 (0.10 to 3.50) | 421 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2, 4 |

| Cardiovascular events | 32 per 1,000 | 31 per 1,000 (8 to 115) | RR 0.95 (0.26 to 3.56) | 1067 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2, 5 |

| Doubling serum creatinine | 83 per 1,000 | 107 per 1,000 (57 to 202) | RR 1.30 (0.69 to 2.44) | 875 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2, 5 |

| AKI | 30 per 1,000 | 61 per 1,000 (31 to 119) | RR 2.04 (1.05 to 3.97) | 1446 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 6 |

| Proteinuria | The SMD was 0.51 lower with aldosterone antagonists (0.82 lower to 0.20 lower) than placebo or standard care | ‐ | 1193 (14) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 7, 8, 9, 10 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) | The mean eGFR was 3.00 mL/min/1.73 m² lower with aldosterone antagonists (5.51 lower to 0.49 lower) than placebo or standard care | ‐ | 1144 (12) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2, 11 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: chronic kidney disease; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in no studies, blinding of outcome assessment in one study and complete outcome data in no studies

2 Treatment estimate had a wide CI

3 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in three studies, blinding of outcome assessment in seven studies, complete outcome data in 11 studies

4 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in one study, blinding of outcome assessment in one study, and complete outcome data in one study

5 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in one study, blinding of outcome assessment in one study, complete outcome data in one study

6 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in one study, blinding of outcome assessment in three studies, complete outcome data in one study

7 Evidence quality was downgraded because of suspected small study effects from asymmetry on inverted funnel plot

8Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in one study, blinding of outcome assessment in seven studies, complete outcome data in nine studies

9 There was significant heterogeneity between studies

10 Evidence quality was downgraded because proteinuria is a surrogate outcome for CKD progression

11 Evidence quality was downgraded because of study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in one study, blinding of outcome assessment in four studies, complete outcome data in six studies

Summary of findings 2. Aldosterone antagonists versus diuretics for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Aldosterone antagonist versus diuretics for proteinuric CKD | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric CKD Intervention: aldosterone antagonist Comparison: diuretics | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with diuretics | Risk with aldosterone antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Hyperkalaemia | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Death | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Cardiovascular events | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Doubling serum creatinine | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| AKI | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Proteinuria | The SMD was 1.59 lower (3.8 lower to 0.62 higher) with aldosterone antagonists than diuretics | ‐ | 139 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

The mean eGFR was 2 mL/min/1.73 m² higher with aldosterone antagonists (26.31 lower to 30.31 higher) than diuretics | ‐ | 12 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 4, 5 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: chronic kidney disease; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Evidence quality was downgraded due to study risks of bias. Allocation concealment in no studies, blinding of outcome assessment in one study, complete data in one study

2 There was significant heterogeneity between the studies

3 Evidence quality was downgraded because proteinuria is a surrogate outcome for CKD progression

4 Treatment estimate had a wide confidence interval

5 Single study with unclear allocation concealment

Summary of findings 3. Aldosterone antagonists versus calcium channel blockers for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Aldosterone antagonists versus calcium channel blocker for proteinuric CKD | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric CKD Intervention: aldosterone antagonist Comparison: calcium channel blocker | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with calcium channel blocker | Risk with aldosterone antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Hyperkalaemia | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Death | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Cardiovascular events | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Doubling serum creatinine | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| AKI | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Proteinuria | Data could not to be meta‐analysed | ‐ | 37 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: chronic kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Single study with unclear allocation concealment

2 Evidence quality was downgraded because proteinuria is a surrogate outcome for CKD progression

Summary of findings 4. Aldosterone antagonists versus ACEi or ACEi plus ARB for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Aldosterone antagonists versus ACEi or ACEi plus ARB for proteinuric chronic kidney disease | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric chronic kidney disease Intervention: aldosterone antagonist Comparison: ACEi or ACEi plus ARB | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with ACEi or ACEi plus ARB | Risk with aldosterone antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Hyperkalaemia | 37 per 1,000 | 60 per 1,000 (24 to 146) | RR 1.62 (0.66 to 3.95) | 500 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Death | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Cardiovascular events | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Doubling serum creatinine | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| AKI | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Proteinuria | Data could not be meta‐analysed | ‐ | 465 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 3, 4, 5 | |

| GFR (mL/min/1.73 m²) |

Data could not be meta‐analysed | ‐ | 18 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 6, 7 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACEi: angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Evidence quality was downgraded due to risks of bias. Allocation concealment in no studies, blinding of outcome assessment in one study, complete outcome data in one study

2 Treatment estimates had wide confidence intervals

3 Evidence quality was downgraded due to risks of bias. Allocation concealment in no studies, blinding of outcome assessment in one study, complete outcome data in two studies

4 Evidence quality was downgraded as proteinuria is a surrogate outcome for CKD progression

5 Raw data was not available in studies to allow pooling of treatment estimates

6 Single study with unclear allocation concealment

7 Insufficient studies to inform precision

Summary of findings 5. Aldosterone antagonist versus nitrate for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Aldosterone antagonist versus nitrate for proteinuric chronic kidney disease | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric chronic kidney disease Intervention: aldosterone antagonist Comparison: nitrate | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with nitrate | Risk with aldosterone antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Hyperkalaemia | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Death | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Cardiovascular events | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Doubling serum creatinine | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| AKI | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Proteinuria | Data could not be meta‐analysed | ‐ | 29 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 | |

| eGFR | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Single study with unclear allocation concealment and unclear blinding of outcome assessment

2 Evidence quality was downgraded as proteinuria is a surrogate outcome for CKD progression

Summary of findings 6. Non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist versus selective aldosterone antagonist for proteinuric chronic kidney disease.

| Non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist versus selective aldosterone antagonist for proteinuric chronic kidney disease | |||||

| Patient or population: proteinuric chronic kidney disease Intervention: non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist Comparison: selective aldosterone antagonist | |||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with selective aldosterone antagonist | Risk with non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | ||||

| Kidney failure | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Hyperkalaemia | 47 per 1,000 | 42 per 1,000 (21 to 83) | RR 0.89 (0.45 to 1.77) | 1023 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Death | 36 per 1,000 | 25 per 1,000 (11 to 56) | RR 0.70 (0.31 to 1.55) | 1055 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| Cardiovascular events | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Doubling serum creatinine | 1/834 | 0/221** | RR 0.80 (0.03 to 19.51) | 1055 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1, 2 |

| AKI | not reported | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ |

| Proteinuria | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | |

| eGFR | not reported | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ** Event rate derived from the raw data. A 'per thousand' rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist group CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; AKI: acute kidney injury; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | |||||

1 Single study

2 Treatment estimate had a wide confidence interval

Aldosterone antagonists (selective or non‐selective) versus placebo or standard care

Kidney failure

In very low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists have uncertain effects on kidney failure (Analysis 1.1 (2 studies, 84 participants): RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.33 to 27.65; I² = 0%) (Figure 5) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 1: Kidney failure

5.

Effect of aldosterone antagonists versus placebo or standard care on kidney failure

Hyperkalaemia

In moderate certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists probably increases risk of hyperkalaemia (Analysis 1.2 (17 studies, 3001 participants): RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.22; I² = 0%) (numbers needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) 41) (Figure 6) compared to placebo or standard care, regardless of whether aldosterone antagonists were combined with one ACEi or ARB (Analysis 1.3.1 (11 studies, 1828 participants): RR 2.05, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.28; I² = 0%), or combined with ACEi plus ARB (Analysis 1.3.2 (4 studies, 149 participants): RR 4.30, 95% CI 1.12 to 16.51; I² = 0%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 2: Hyperkalaemia

6.

Effect of aldosterone antagonists versus placebo or standard care on hyperkalaemia

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 3: Subgroup analysis: hyperkalaemia ‐ number of RAS inhibitors used

Death

In low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists have uncertain effects on death (any cause) (Analysis 1.5 (3 studies, 421 participants): RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.10 to 3.50; I² = 0%) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 5: Death

Cardiovascular events

In low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists have uncertain effects on cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.6 (3 studies, 1067 participants): RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.56; I² = 42%) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 6: Cardiovascular events

Mehdi 2009 reported one myocardial infarction in the aldosterone antagonist group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Aldosterone antagonists had uncertain effects on stroke compared to placebo or standard care (Analysis 1.8 (3 studies, 1233 participants): RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.12 to 3.44; I² = 11%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 8: Stroke

Proteinuria

In very low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists may reduce proteinuria (Analysis 1.9 (14 studies, 1193 participants): SMD ‐0.51, 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.20; I² = 82%) (Figure 7) compared to placebo or standard care. There was significant heterogeneity.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 9: Proteinuria

7.

Effect of aldosterone antagonists versus placebo or standard care on proteinuria.

Kidney function

Glomerular filtration rate

In low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists may reduce eGFR (Analysis 1.12 (13 studies, 1165 participants): MD ‐3.00 mL/min/1.73 m², 95% CI ‐5.51 to ‐0.49; I² = 0%) (Figure 8) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 12: eGFR [mL/min/1.73 m²]

8.

Effect of aldosterone antagonists versus placebo or standard care on GFR [mL/min/1.73 m²].

Doubling of serum creatinine

Two studies (ARTS‐DN 2015; Mehdi 2009) reported doubling of SCr (or equivalent eGFR decline ≥ 57%) with events only occurring in Mehdi 2009. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Blood pressure

In very low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists may reduce systolic blood pressure (Analysis 1.16 (14 studies, 911 participants): MD ‐4.98 mmHg, 95% CI ‐8.22 to ‐1.75; I² = 87%) but had uncertain effects on diastolic blood pressure (Analysis 1.17 (13 studies, 875 participants): MD ‐1.04 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.82 to 0.73; I² = 79%) compared to placebo or standard care. There was significant heterogeneity in both analyses.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 16: Systolic BP

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 17: Diastolic BP

Serum potassium

In very low certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists may increase serum potassium (Analysis 1.20 (17 studies, 1326 participants): MD 0.19 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.29; I² = 81%) compared to placebo or standard care. There was significant heterogeneity.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 20: Serum potassium

Acute kidney injury

In moderate certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists probably increases the risk of acute kidney injury (Analysis 1.22 (5 studies, 1446 participants): RR 1.94, 95% CI 0.99 to 3.79; I² = 0%) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 22: Acute kidney injury

Gynaecomastia

In moderate certainty evidence, aldosterone antagonists probably increases the risk of gynaecomastia (Analysis 1.23 (4 studies, 281 participants): RR 5.14, 95% CI 1.14 to 23.23; I² = 0%) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 23: Gynaecomastia

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria; regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; falls; and fatigue.

Analysis of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity in the effects of spironolactone on proteinuria was explored through sub‐group analyses.

Baseline kidney disease

Aldosterone antagonists reduced proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.9.1 (7 studies, 572 participants): SMD ‐0.46, 95% CI ‐0.64 to ‐0.27; I² = 0%) but had unclear effects on non‐diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.9.2 (5 studies, 367 participants): SMD ‐0.68, 95% CI ‐1.57 to 0.21; I² = 93%) compared to placebo or standard care.

Aldosterone antagonists reduced systolic blood pressure to a greater extent in non‐diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.16.2 (5 studies, 367 participants): MD ‐3.35, 95% CI ‐5.06 to ‐1.65; I² = 0%) than diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.16.1 (5 studies, 228 participants): MD ‐1.07, 95% CI ‐1.82 to ‐0.32; I² = 0%) compared to placebo or standard care.

Aldosterone antagonists reduced diastolic blood pressure in non‐diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.17.2 (4 studies, 331 participants): MD ‐1.62, 95% CI ‐2.86 to ‐0.38; I² = 0%) but had unclear effects on diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.17.1 (5 studies, 249 participants): MD ‐1.06, 95% CI ‐1.80 to ‐0.31; I² = 25%) compared to placebo or standard care.

Aldosterone antagonists increased serum potassium in both diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.20.1 (9 studies, 664 participants): MD 0.21 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.28; I² = 0%) and non‐diabetic kidney disease (Analysis 1.20.2 (6 studies, 367 participants): MD 0.30 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.50; I² = 92%) compared to placebo or standard care.

Study duration

Aldosterone antagonists reduced proteinuria in studies reporting follow‐up of less than six months (Analysis 1.24.1 (9 studies, 822 participants): SMD ‐0.39, 95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.24; I² = 0%) but had unclear effects in studies reporting follow‐up of longer than six months (Analysis 1.24.2 (4 studies, 331 participants): SMD ‐0.59, 95% CI ‐1.68 to 0.50; I² = 95%) compared to placebo or standard care.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 24: Subgroup analysis: proteinuria ‐ duration of follow‐up

Aldosterone antagonists reduced systolic blood pressure in both studies reporting follow‐up of less than six months (Analysis 1.25.1 (10 studies, 580 participants): MD ‐5.65, 95% CI ‐10.96 to ‐0.33; I² = 90%) and studies reporting follow‐up of longer than six months (Analysis 1.25.2 (4 studies, 331 participants): MD ‐3.62, 95% CI ‐6.09 to ‐1.15; I² = 15%).

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 25: Subgroup analysis: systolic BP ‐ duration of follow‐up

Aldosterone antagonists reduced diastolic blood pressure in studies reporting follow‐up longer than six months (Analysis 1.26.2 (4 studies, 331 participants): MD ‐1.62, 95% CI ‐2.86 to ‐0.38; I² = 0%) but had unclear effect in studies reporting follow‐up less than six months (Analysis 1.26.1 (9 studies, 553 participants): MD ‐0.98, 95% CI ‐3.71 to 1.75; I² = 83%).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 26: Subgroup analysis: diastolic BP ‐ duration of follow‐up

Aldosterone antagonists increased serum potassium in both studies reporting follow up less than six months (Analysis 1.27.1 (12 studies, 954 participants): MD 0.16 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.22; I² = 23%) and studies reporting follow‐up longer than six months (Analysis 1.27.2 (4 studies, 331 participants): MD 0.35 mEq/L, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.65; I² = 93%).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Aldosterone antagonist versus placebo/standard care (all studies), Outcome 27: Subgroup analysis: serum potassium ‐ duration of follow‐up

Aldosterone antagonist selectivity

A single study (Boesby 2013) reported the effect of the selective aldosterone antagonist eplerenone on proteinuria, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and serum potassium. All other studies reported the effect of the non‐selective aldosterone antagonist spironolactone on these outcomes. Subgroup analysis was not performed.

Baseline proteinuria or albuminuria

Single studies specified baseline albuminuria > 100mg/g (Kato 2015), > 300mg/g (Rossing 2005), > 300mg/day (Schjoedt 2005) and 45 to 300 mg/day (Ito 2019a), and which reported on proteinuria and serum potassium. Subgroup analysis was not performed.

Single studies specified baseline proteinuria > 150mg/day (Horestani 2012), > 0.3g/day (Tylicki 2008), >1g/g (Bianchi 2006), and > 1.5g/day (Chrysostomou 2006), and which reported on proteinuria, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and serum potassium. All other studies specified baseline proteinuria > 0.5g/day or did not specific baseline proteinuria. Subgroup analysis was not performed.

Baseline kidney function

Single studies specified baseline eGFR 15 to 60 mL/min/1.73 m² (Boesby 2013), eGFR 25 to 50 mL/min/1.73 m² (Abolghasmi 2011), eGFR > 45 mL/min/1.73 m² (Tylicki 2008), and which reported on proteinuria, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and serum potassium. All other studies specified baseline eGFR > 30 mL/min/1.73 m² or did not specific baseline kidney function. Subgroup analysis was not performed.

Non‐selective aldosterone antagonists (spironolactone or canrenone) plus ACEi or ARB versus diuretics plus ACEi or ARB

Proteinuria

In very low certainty evidence, non‐selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB had an uncertain effect on proteinuria (Analysis 2.1 (2 studies, 139 participants): SMD ‐1.59, 95% CI ‐3.80 to 0.62; I² = 93%) compared to diuretics plus ACEi or ARB. There was significant heterogeneity.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Aldosterone antagonist plus RAS inhibitor versus other diuretic plus RAS inhibitor, Outcome 1: Proteinuria

Glomerular filtration rate

One study reported eGFR (Morales 2015) and one cross‐over study (Smolen 2006) did not report individual study periods. Meta‐analysis was not performed due to inability to combine study data.

Blood pressure

In very low certainty evidence, non‐selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB had an uncertain effect on systolic blood pressure (Analysis 2.8 (3 studies, 151 participants): MD ‐3.79, 95% CI ‐14.36 to 6.79; I² = 90%) and diastolic blood pressure (Analysis 2.7 (3 studies, 151 participants): MD ‐1.56, 95% CI ‐3.52 to 0.41; I² = 3%) compared to diuretics plus ACEi or ARB. There was significant heterogeneity in the analysis for systolic blood pressure.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Aldosterone antagonist plus RAS inhibitor versus other diuretic plus RAS inhibitor, Outcome 8: Systolic BP

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Aldosterone antagonist plus RAS inhibitor versus other diuretic plus RAS inhibitor, Outcome 7: Diastolic BP

Serum potassium

In low certainty evidence, non‐selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB may increase serum potassium (Analysis 2.11 (2 studies, 121 participants): MD 0.31, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.45; I² = 0%) compared to diuretics plus ACEi or ARB.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Aldosterone antagonist plus RAS inhibitor versus other diuretic plus RAS inhibitor, Outcome 11: Serum potassium

Fatigue

Fogari 2014 reported no difference in fatigue between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; hyperkalaemia; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; and falls.

Non‐selective aldosterone antagonists (spironolactone) versus calcium channel blockers

Proteinuria

Takebayashi 2006 reported spironolactone reduced urinary albumin excretion but did not change in amlodipine group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Blood pressure

Takebayashi 2006reported no change in systolic or diastolic blood pressure between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Serum potassium

Takebayashi 2006 reported serum potassium was lower in the calcium channel blocker group compared to the spironolactone group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; hyperkalaemia; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; eGFR; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; blood pressure; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Selective aldosterone antagonists (eplerenone) alone versus ACEi alone

Hyperkalaemia

One cross‐over study reported hyperkalaemia (Morales 2009). Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Proteinuria

One cross‐over study reported proteinuria (Morales 2009). Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; eGFR; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; blood pressure: serum potassium; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Selective aldosterone antagonists (eplerenone) alone versus ACEi plus ARB

Hyperkalaemia

One cross‐over study reported hyperkalaemia (Morales 2009). Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Proteinuria

One cross‐over study reported proteinuria (Morales 2009). Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; eGFR; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; blood pressure: serum potassium; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Selective aldosterone antagonists (eplerenone) plus ACEi or ARB (or both) versus ACEi or ARB (or both)

Hyperkalaemia

Selective aldosterone antagonists plus ACEi or ARB (or both) may increase the risk of hyperkalaemia (Analysis 6.1 (2 studies, 500 participants): RR 1.62, 95% CI 0.66 to 3.95; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Eplerenone plus ACEi or ARB (or both) versus ACEi or ARB (or both), Outcome 1: Hyperkalaemia

Proteinuria

Six studies reported proteinuria, however data could not be meta‐analysed (Boesby 2011; Cohen 2010; Epstein 2002; Epstein 2006; Haykal 2007; Tylicki 2012).

Blood pressure

Four studies reported blood pressure, however data could not be meta‐analysed (Cohen 2010; Epstein 2002; Epstein 2006; Haykal 2007).

Glomerular filtration rate

One cross‐over study (Tylicki 2012) reported no difference in eGFR between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Serum potassium

One cross‐over study (Tylicki 2012) reported no difference in serum potassium between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Selective aldosterone antagonists (eplerenone) plus ACEi or ARB (or both) versus ACEi or ARB (or both) plus nitrate

Proteinuria

Cohen 2010 reported urine protein excretion was significantly reduced after four weeks of eplerenone while it increased in the comparator group. We could not conduct a meta‐analysis as additional data could not be obtained from the investigators.

Blood pressure

Cohen 2010 reported systolic blood pressure was reduced by 9.7 ± 6.4 mmHg in the eplerenone group and by 1.0 ± 5.4 mmHg in the ACEi/ARB plus isosorbide group at 4 weeks. No data were available about diastolic blood pressure. We could not conduct a meta‐analysis as additional data could not be obtained from the investigators.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; hyperkalaemia; death (any cause); cardiovascular events; eGFR; doubling of SCr; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria: serum potassium; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists (finerenone) versus selective aldosterone antagonist (eplerenone)

Hyperkalaemia

ARTS‐HF 2015 reported no difference in the risk of hyperkalaemia between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Death

ARTS‐HF 2015 reported no difference in the risk of death between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Glomerular filtration rate

ARTS‐HF 2015 reported no significant change in GFR from baseline in either group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Doubling of serum creatinine

ARTS‐HF 2015 reported no difference in the risk of doubling of SCr between the two groups. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Blood pressure

ARTS‐HF 2015 reported no significant change in systolic blood pressure from baseline in either group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; cardiovascular events; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria: serum potassium; acute kidney injury; gynaecomastia; fatigue; and falls.

Non‐selective aldosterone antagonists (spironolactone) plus ACEi and ARB versus ACEi

Hyperkalaemia

Bianchi 2010 reported hyperkalaemia in 9/64 patients in the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group and 3/64 patients in the ACEi group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Proteinuria

Bianchi 2010 reported proteinuria was significantly lower in the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group compared to ACEi group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Glomerular filtration rate

Bianchi 2010 reported eGFR was lower in ACEi group compared to the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Blood pressure

Bianchi 2010 systolic and diastolic blood pressure was lower in the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group compared to the ACEi group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Serum potassium

Bianchi 2010 reported serum potassium was lower in the ACEi group compared to the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Gynaecomastia

Bianchi 2010 reported gynaecomastia in 9/64 patients in the spironolactone plus ACEi and ARB group and 0/64 patients in the ACEi group. Meta‐analysis was not performed.

Other outcomes

Data for the following outcomes were not extractable in a format required for inclusion in analyses or not reported in the available studies: kidney failure; death; cardiovascular events; progression from micro‐ to macroalbuminuria; regression from macro‐ to microalbuminuria and regression from micro‐ to normoalbuminuria: acute kidney injury; fatigue; and falls.

Publication bias

Overall, there were sufficient data and lack of statistical heterogeneity for the outcomes eGFR and hyperkalaemia for the comparison of aldosterone antagonists and placebo or standard care. There was no evidence of small study effects in the analysis of eGFR (Figure 9) or hyperkalaemia (Figure 10).

9.

Funnel plot of comparison studies comparing aldosterone antagonist versus control for the study endpoint of GFR [mL/min/1.73 m²].

10.

Funnel plot of comparison studies comparing aldosterone antagonist versus control for the study endpoint of hyperkalaemia.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review of the evidence for aldosterone antagonists in addition to renin angiotensin system antagonists for preventing the progression of CKD, 44 studies involving 5637 participants were available. Studies included follow‐up for generally three to 12 months. Compared to ACEI or ARB (or both), the addition of an aldosterone antagonist has uncertain effects on progression to kidney failure, major cardiovascular events, and death (any cause) while probably doubling the risk of hyperkalaemia and probably increasing risk of acute kidney injury and gynaecomastia in adults who have proteinuric CKD stages 1 to 4. Aldosterone blockade may reduce proteinuria and kidney function in addition to co‐intervention with ACEi or ARB over a median treatment duration of 3.5 months and may lower systolic blood pressure but had little or no effect on diastolic blood pressure. Aldosterone antagonists appeared to lower systolic pressure to a greater extent in non‐diabetic kidney disease compared to diabetic kidney disease. While aldosterone antagonists appeared to lower proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease, its anti‐proteinuric effect in non‐diabetic kidney disease is less certain. Compared to diuretics, non‐selective aldosterone antagonists (spironolactone or canrenone) had uncertain effects on proteinuria and systolic blood pressure but may increase serum potassium. Furthermore, data comparing aldosterone antagonists to calcium channel blockers or nitrates, and data for treatment effects of selective aldosterone antagonists (eplerenone) and non‐steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists (finerenone) were sparse leading to serious imprecision in treatment estimates or a lack of sufficient data for meta‐analysis.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence