Abstract

Objectives

To identify and critically appraise published clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) regarding healthcare of gender minority/trans people.

Design

Systematic review and quality appraisal using AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool), including stakeholder domain prioritisation.

Setting

Six databases and six CPG websites were searched, and international key opinion leaders approached.

Participants

CPGs relating to adults and/or children who are gender minority/trans with no exclusions due to comorbidities, except differences in sex development.

Intervention

Any health-related intervention connected to the care of gender minority/trans people.

Main outcome measures

Number and quality of international CPGs addressing the health of gender minority/trans people, information on estimated changes in mortality or quality of life (QoL), consistency of recommended interventions across CPGs, and appraisal of key messages for patients.

Results

Twelve international CPGs address gender minority/trans people’s healthcare as complete (n=5), partial (n=4) or marginal (n=3) focus of guidance. The quality scores have a wide range and heterogeneity whichever AGREE II domain is prioritised. Five higher-quality CPGs focus on HIV and other blood-borne infections (overall assessment scores 69%–94%). Six lower-quality CPGs concern transition-specific interventions (overall assessment scores 11%–56%). None deal with primary care, mental health or longer-term medical issues. Sparse information on estimated changes in mortality and QoL is conflicting. Consistency between CPGs could not be examined due to unclear recommendations within the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care Version 7 and a lack of overlap between other CPGs. None provide key messages for patients.

Conclusions

A paucity of high-quality guidance for gender minority/trans people exists, largely limited to HIV and transition, but not wider aspects of healthcare, mortality or QoL. Reference to AGREE II, use of systematic reviews, independent external review, stakeholder participation and patient facing material might improve future CPG quality.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019154361.

Keywords: protocols & guidelines, quality in health care, sexual and gender disorders, international health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First systematic review to identify and use a validated quality appraisal instrument to assess all international clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) addressing gender minority/trans health.

International CPGs were studied due to their influential status in gender minority/trans health, though further research is needed on national and local CPGs.

An innovative prioritisation exercise was performed to elicit stakeholders’ priorities and inform the setting of AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool) quality thresholds, however these stakeholder priorities may not be applicable outside the UK.

An inclusive approach using wide criteria, extensive searches and approaching key opinion leaders should have allowed the study to identify all relevant international CPGs, however it is possible some may have been missed.

Introduction

Assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines

Evidence-based practice integrates best available research with clinical expertise and the patient’s unique values and circumstances. High-quality clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) support high-quality healthcare delivery. They can guide clinicians and policymakers to improve care, reduce variation in clinical practice, thereby affecting patient safety and outcomes. The Institute of Medicine defines CPGs as: ‘statements that include recommendations intended to optimise patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options’,1 although other definitions exist.2 Recommendations are used alongside professional judgement, directly or within decision aids, in training and practice. CPGs are important but have limitations depending on evidence selection and development processes.3 Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) was developed to address the evidence that is selected and appraised during CPG development.4–6 Using a systematic approach and transparent framework for developing and presenting summaries of evidence, GRADE is the most widely adopted tool worldwide for grading the quality of evidence and making recommendations,7 but does not alone ensure a CPG is high quality. Strength of evidence is only one component of what makes a ‘good’ CPG; factors such as transparency, rigour, independence, multidisciplinary input, patient and public involvement, avoidance of commercial influences and rapidity8 9 should also be considered. Broader domains of CPG quality are included in the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation instrument AGREE II.10–12 Despite widely recognised principles and methods for developing sound CPGs, current research shows that guidelines on various topics lack appropriate uptake of systematic review methodologies in their development,13 give recommendations that conflict with scientific evidence14 or do not adequately take into account existing CPG quality and reporting assessment tools.15 This emphasises the ongoing need to appraise guidelines to ensure evidence-informed care.

Healthcare for gender minority/trans people

‘Trans’ is an umbrella term for individuals whose inner sense of self (gender identity) or how they present themselves using visual or behavioural cues (gender expression) differs from the expected stereotypes (gender) culturally assigned to their biological sex.16 'Gender minority' is an often-used alternative population description. Some gender minority/trans people may seek medical transition, which involves interventions such as hormones or surgery that alter physical characteristics and align appearance with gender identity. Patient numbers referred to UK gender identity clinics and length of waiting lists have increased in the last decade, particularly for adolescents,17 a phenomenon seen elsewhere.18 Gender minority/trans people may have continuing, sometimes complex, life-long healthcare needs whether they undergo medical transition or not. Gender minority/trans people may experience more mental health issues such as mood and anxiety disorders,19 substance use20 and higher rates of suicidal ideation.21 They may seek assistance with sexual health, mental health,22 substance use disorders,23 prevention and/or management of HIV24 as well as usual general health enquiries. However, they may encounter difficulties in accessing healthcare,25 reporting negative healthcare experiences,26 discrimination and stigma.27 28 Like all individuals, gender minority/trans people require high-quality evidence-based healthcare25 29 addressing general and specific needs.

Guidelines used internationally and in the UK

The quality of current guidelines on gender minority/trans health is unclear. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care Version 7 (SOCv7)30 represent normative standards for clinical care, acting as a benchmark in this field.31 Globally, many national and local guidelines32–35 are adaptations of, acknowledge being influenced by, or are intended to complement WPATH SOCv7,30 despite expressed reservations that WPATH SOCv730 is based on lower-quality primary research, the opinions of experts and lacks grading of evidence.36

In the UK, an advocacy group worked to incorporate WPATH SOCv730 into national practice.37 WPATH SOCv730 informs National Health Service (NHS) gender identity clinics38 and guidelines produced by the Royal College of Psychiatrists (without use of GRADE).39 No CPGs were available from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), British Association of Gender Identity Specialists, or medical Royal Colleges, although the Royal College of General Practitioners issued a position statement on gender minority/trans healthcare in 2019.40 Assessing quality of international CPGs such as WPATH SOCv730 has practice implications for the NHS38 and private sector. CPGs with international scope may present additional challenges (eg, the implementability of key recommendations might not be easily translated among different contexts) but they seem to influence discourse around gender minority/trans health.36 No prior study has investigated the number and quality of guidelines to support the care and well-being of gender minority/trans people. The purpose of this research was to identify and critically appraise all published international CPGs relating to the healthcare of gender minority/trans people.

Methods

Approach/research design

The rationale was to identify the key CPGs available to healthcare practitioners in this field of clinical practice. Following preliminary searches, we chose international CPGs in view of WPATH’s influence within the UK and elsewhere, and to avoid ‘double-counting’. We considered AGREE II10–12 the most appropriate tool; it is the most comprehensively validated and evaluated instrument available for assessing CPGs,41 42 designed for use by non-expert stakeholders10 such as healthcare providers, practicing clinicians and educators.11 It benefits from clear instructions and prompts regarding scoring and several people applying the criteria independently (a minimum of two reviewers, but four are recommended). AGREE II synthesis calculates quality scores from 23 appraisal criteria organised into six key domains (scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, editorial independence) and an overall assessment of ‘Recommend for use?’ (answer options; yes, no, yes if modified). This systematic review was conducted according to a pre-specified PROSPERO protocol https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=154361 uploaded 19 December 2019. The MEDLINE strategy was straightforward; although not formally processed,43 it was peer-reviewed by an information specialist.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We defined a CPG as a systematically developed set of recommendations that assist practitioners and patients in the provision of healthcare in specific circumstances, produced after review and assessment of available clinical evidence.1 2 44–46 CPGs published after 1 January 2010 were eligible if they (or part thereof) specifically targeted patients/population with gender minority/trans status and/or gender dysphoria, were evidence-based, with some documentation of development methodology, had international scope (more than one country, defined as a Member State of the United Nations) and were an original source. We chose the time frame to focus on the most recent guidelines, currently applicable to practice and to include WPATH SOCv7.30 CPGs were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: participants/population was adults and/or children who are gender minority/trans with no exclusion due to comorbidities or age although differences/disorders in sex development (intersex) were excluded; exposure/intervention was any health intervention related to gender dysphoria or gender affirmation, or health concerns of gender minority/trans people, including screening, assessment, referral, diagnosis and interventions. We excluded previous versions of the same CPG. We used broad criteria because terminology has been in flux with changes made in both International Classification of Diseases and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders diagnostic criteria.16 There were no restrictions on setting or language.

Search strategy and guideline selection

We conducted the searches up to 11 June 2020 (CM), using search terms and appropriate synonyms (as Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and text words) that we developed based on population and exposures (online supplemental table 1). We searched six databases (Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, LILACS) and six CPG websites (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), eGuidelines and Guidelines, NICE National Library for Health, SIGN, EBSCO DynaMed Plus, Guidelines International Network Library) and the World Health Organization (WHO). The NGC closed in 2017 but CM hand-searched the archive. In addition to protocol, individual reviewers (IA, DC and MHJ) hand-searched four specialty journals (International Journal of Transgender Health, Transgender Health, LGBT Health, Journal of Homosexuality) to ensure key subject-relevant sources of abstracts were thoroughly checked. In order to find potential grey literature CPGs outwith the scholarly literature, two reviewers (IA and SD) independently performed four separate Google searches (not Google Scholar as misstated in the protocol) by using one generic (clinical practice guidelines) plus one specific term (transgender, gender dysphoria, trans health or gender minority) and examining the first 100 hits. We identified International Key Opinion Leaders (n=24) via publications known to reviewers (DC and SD) and contacted them via email, with one reminder, to identify further guidelines. Reference lists of relevant reviews and all full-text studies were hand-searched to identify any relevant papers or CPGs not found by database searching. Two reviewers (SB and SD) independently read all titles and abstracts and assessed for inclusion. If there was uncertainty or disagreement, or reasonable suspicion that the full-text might lead to another relevant CPG, the full-text was obtained. Non-English abstracts were Google-translated but if a possible CPG could not be reliably excluded, the full-text paper was obtained and translated. Where full-text publications could not be accessed, we contacted authors directly. Two reviewers (SB and either DC/MHJ) independently carried out full-text assessment to determine inclusion or exclusion from the systematic review based on the above criteria, and noted reasons for excluding full-texts. The whole team discussed uncertainties and disagreements to achieve consensus, with voting and final adjudication by the senior author (CM).

bmjopen-2021-048943supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Data extraction

Two reviewers (SB and SD) independently collected formal descriptive data of included CPGs. All ambiguities or discrepancies were referred to the team for discussion and to re-examine original texts and extract data. Information collected was title, author, year of publication, number of countries covered, originating organisation, audience, methods used, page and reference numbers (excluding accompanying materials) and funding. Key recommendations were extracted for comparison between CPGs. We searched for all text mentions of mortality or any measures of quality of life (QoL), and noted if accompanied by a citation. All patient facing material was extracted. In addition, we extracted data about publication outlet (journal/website), and whether the quantity of information pertaining to the health of gender minority/trans people represented a complete, partial or marginal proportion of recommendations in the CPG.

Outcomes

Outcomes were: the number and quality assessment scores (using AGREE II) of international CPGs addressing the health of gender minority/trans people; analysis and comparison of the presence or absence of information on estimated changes in mortality or QoL (any measure) following any specific recommended intervention, over any time interval; the consistency (or lack thereof) of recommendations across the CPGs; and the presence (or absence) of key messages for patients.

Quality assessment

All authors completed AGREE II video training, a practice assessment and two pilots whose results were discussed. The six reviewers (IA, SB, DC, SD, MHJ and CM) independently and anonymously completed quality scoring on every CPG by rating each of the items using the standard proforma on the My AGREE PLUS online platform (AGREE enterprise website),11 which also calculated group appraisal scores.

Patient and public involvement

The AGREE II instrument generates quality scores but does not set specific parameters for what constitutes high quality, recommending that decisions about defining such thresholds should be made prior to performing appraisals, considering relevant stakeholders and the context in which the CPG is used.11 To help set quality thresholds, we conducted an AGREE II domain prioritisation exercise in January 2020 via email, with one reminder. It was considered impossible to ensure comprehensive representation of international stakeholders. We chose the UK for feasibility, although validity might be limited to UK-based clinicians. Fifty-two UK service-user stakeholder groups and gender minority/trans advocacy organisations, identified via reviewer knowledge and internet searches (IA, SB, DC, SD, MHJ and CM), were informed about the study. They were invited to participate in a stakeholder prioritisation of the AGREE II domains, created using SurveyMonkey and with an option to remain anonymous (https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/WLZ55NQ gives invitation wording, links to resources and protocol). The reviewer team performed an anonymous prioritisation for comparison.

Strategy for data and statistical analyses

Simple frequencies were used to present the stakeholder and reviewer priorities, and outcomes. Following team discussion of the prioritisation exercise results, no prespecified quality threshold score was used to define high or low quality, although colour was superimposed (≤30%, 31%–69% and ≥70%) on the final scores table to aid visual comparisons and interpretation.

Results

Search results

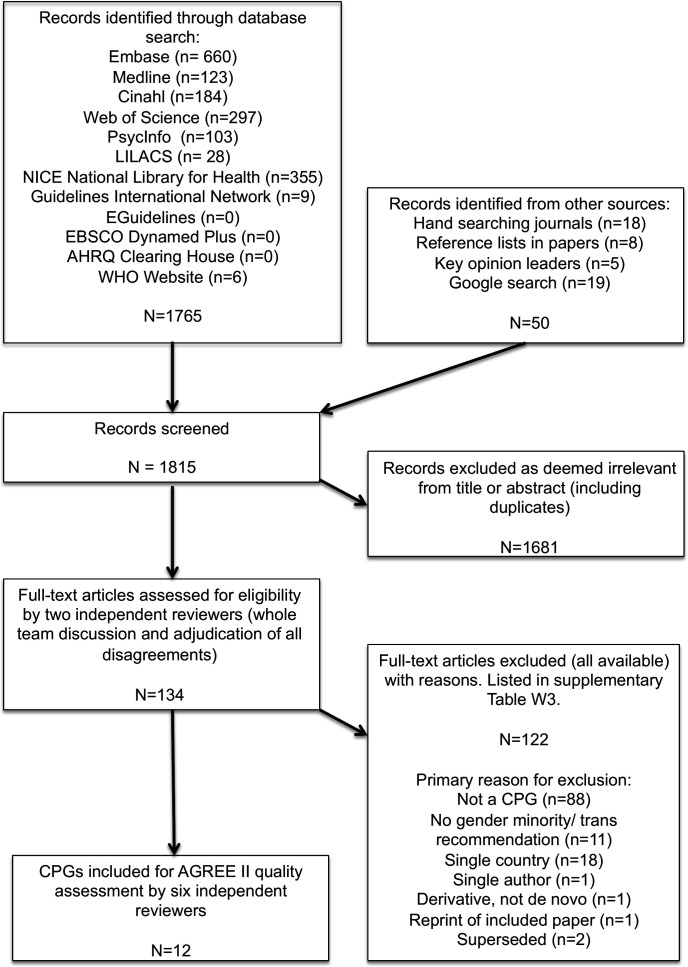

Figure 1 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart47) shows that 1815 citations were identified, of which 134 full-text publications were read (all available, three supplied by authors) and 122 excluded (online supplemental table W2 with reasons).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool; CPG, clinical practice guideline; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Data extraction

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the CPGs. Online supplemental tables W3 and W4 show raw data of key recommendations and mortality and QoL evidence.

Table 1.

General characteristics of included clinical practice guidelines (n=12)

| Number | Author (year) | Full title | Countries covered | Origin | Primary audience | Design (systematic review, SR, used and methods thereafter) | Planned update given | Funding |

| 1 | Coleman et al (2012)30 | Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender and gender non-conforming people V.7 | Global | WPATH | Health professionals | Work groups submit manuscripts based on prior literature reviews, no explicit links of recommendations to evidence, expert consensus. No independent external review | No | Tawani Foundation and gift from anonymous donor |

| 2 | Davies et al (2015)51 | Voice and communication change for gender non-conforming individuals: giving voice to the person inside | Global | WPATH | Speech-language therapists | Review of evidence. Expert consensus. No independent external review | No | Transgender Health Information Program of British Columbia Canada |

| 3 | ECDC (2018)58 | Public health guidance on HIV, hepatitis B and C testing in the EU/EEA | EU/EEA | ECDC consortium CHIP, PHE, SSAT and EATG | Member states’ public health professionals who coordinate the development of national guidelines or programmes for HBV, HCV and HIV testing | Four SRs, SIGN, NICE and AXIS checklists. Ad hoc internal and external expert panel, independent chair, expert consensus. No independent external review | No | Commissioned by ECDC, contractor Rigshospitalet CHIP |

| 4 | Gilligan et al (2017)52 | Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology consensus guideline | USA and others | ASCO | Clinicians who care for adults with cancer | Nine questions (one SR), expert consensus and a Delphi exercise. No independent external review | Regular review 3-year check | None declared |

| 5 | Hembree et al (2017)53 | Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline | Global | Endocrine Society | Endocrinologists, trained mental health professionals and trained physicians | Two SRs and GRADE, rest expert consensus. No independent external review | No | Endocrine Society |

| 6 | IAPHCCO (2015)54 | IAPAC guidelines for optimising the HIV care continuum for adults and adolescents | Global | IAPAC | Care providers, programme managers, policymakers, affected communities, organisations, and health systems involved with implementing HIV programmes and/or delivering HIV care | A systematic search of CDC database, expert consensus. No independent external review | No | IAPAC, US NIH and Office of AIDS Research |

| 7 | Ralph et al (2010)56 | Trauma, gender reassignment and penile augmentation | Not specified (international publication) | Author group | Not stated (urological surgeons) | No SR. Unclear if literature review. Leading experts’ consensus opinion. No independent external review | No | None declared |

| 8 | Strang et al (2018)57 | Initial clinical guidelines for co-occurring autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria or incongruence in adolescents | Not specified (international publication) | Author group | Clinicians | No SR or literature review. Two-stage Delphi consensus. No independent external review | No | Isadore and Bertha Gudelsky Family Foundation |

| 9 | T'Sjoen et al (2020)55 | ESSM Position Statement ‘Assessment and hormonal management in adolescent and adult trans people, with attention for sexual function and satisfaction’ | Europe | ESSM | European clinicians working in transgender health, sexologists and other healthcare professionals | No SR. Leading experts’ consensus opinion. No independent external review | No | ESSM |

| 10 | WHO (2011)48 | Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender people. Recommendations for a public health approach | Global | WHO | National public health officials and managers of HIV/AIDS and STI programmes, NGOs including community and civil society organisations, and health workers | 13 SRs for PICOs and GRADE, external GDG, and independent external review | Yes in 2015 | BMZ and PEPFAR through CDC and USAID |

| 11 | WHO (2012)49 | Guidance on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV. Recommendations for use in the context of demonstration projects | Global | WHO | Countries/member states | Four SRs (including values and preferences reviews) and GRADE, external GDG and independent external review group | Yes in 2015 | Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation |

| 12 | WHO (2016)50 | Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations. 2016 update | Global | WHO | National HIV programme managers and other decision-makers within ministries of health and those responsible for health policies, programmes and services in prisons | Two new SRs in revised guidance, GRADE, external GDGs and 79 independent external peer reviewers | Regular updates; no detail | UNAIDS, PEPFAR, Global Fund |

AACE, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; ASA, American Society of Andrology; ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AXIS, Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies; BMZ, German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development; CDC, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CHIP, CHIP/Region H, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen; CPG, clinical practice guideline; EATG, European AIDS Treatment Group; EAU, European Association of Urology; ECDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; ESE, European Society of Endocrinology; ESPE, European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology; ESSM, European Society for Sexual Medicine; EU/EEA, European Union/European Economic Area; GDG, guideline development group; Global Fund, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IAPAC, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care; IAPHCCO, International Advisory Panel on HIV Care Continuum Optimization; NGO, non-governmental organisations; NICE, National Institute of Health and Care Excellence; NIH, National Institutes of Health; PEPFAR, US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; PES, Pediatric Endocrine Society; PHE, Public Health England; PICO, Participants/patients, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; SR, systematic review; SSAT, St Stephen’s AIDS Trust; STI, sexually transmitted infection; UNAIDS, The Unified Budget, Results and Accountability Framework of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; USAID, US Agency for International Development; WPATH, World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Number and characteristics of clinical practice guidelines

Twelve CPGs (table 1) originated from: WHO (n=3),48–50 WPATH (n=2),30 51 professional specialist/special-interest societies (n=4),52–55 small groups of experts (n=2)56 57 and one consortium.58 All were published in English, in journals,51–57 the organisation’s website48–50 58 or both.30 Guideline development methodology was variable, including use of systematic reviews (table 1). Ten CPGs had no external review, eight had no update plans. Gender minority/trans health recommendations made up complete (n=5),30 51 53 55 57 partial (n=4)48–50 56 or marginal (n=3)52 54 58 focus of content. CPGs contained 10 to 155 pages, and 20 to 505 references. Funding sources were wide-ranging and sometimes multiple, from government agencies, professional societies, charities and private donations. Two CPGs provided no funding details.52 56

A 13th CPG was excluded post-scoring as it had been superseded by a 2020 version without recommendations for gender minority/trans people.59 It was arguable if four included CPGs did meet criteria: one had not been withdrawn48; one contained minimal relevant content52; one might not have been intended as a CPG30 (although WPATH SOCv7’s stated overall goal is ‘to provide clinical guidance for health professionals’30 it contains no list of key recommendations nor auditable quality standards, yet is widely used to compare procedures covered by US providers60 61); one variously described itself as ‘position statement’ and ‘position study’ (stating it did ‘not aim to provide detailed clinical guidelines for professionals such as… [named]30 53’, but evidence was obviously linked to key recommendations for clinicians55). After discussion it was decided not to exclude these borderline CPGs, as the definition of CPG in the protocol was intended to favour an inclusive approach.

Quality prioritisation and assessment

Results of the domain prioritisation by stakeholders (n=19 replies, response rate 39% excluding 3 ‘undeliverable’) and reviewers (n=6) showed that stakeholders prioritised stakeholder involvement, whereas the reviewer team prioritised methodological rigour (online supplementary table W5). No stakeholder asked for clarification or more information.

Table 2 shows AGREE II scores by domain (8%–94%), and overall (11%–94%). The quality scores have a wide range and heterogeneity. Five CPGs focused on trans people as a key population for HIV and other blood-borne infections (overall assessment scores 69%–94%). Six CPGs concerned transition-specific interventions (overall assessment scores 11%–56%). Transition-related CPGs tended to lack methodological rigour and rely on patchier, lower-quality primary research. The two prioritised domain scores were usually comparable with the overall AGREE II quality assessment (ranges; stakeholder involvement 14%–93%, methodological rigour 17%–87%). Four CPGs obtained a majority opinion ‘recommend for use’,48–50 58 five CPGs had unanimous ‘do not recommend’30 51 55–57 and three had minority support with division about the extent of ‘yes, if modified’52–54 (table 2). Despite wide variation there was a pattern; HIV and blood-borne infection guidelines48–50 54 58 were higher quality, and those focusing on transition were lower quality.30 53 55–57

Table 2.

AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool) domain percentages and overall assessment of included guidelines, and summary of mortality/quality of life measures (n=12)

| Number | Author (year) | Scope and purpose | Stakeholder involvement | Rigour of development | Clarity and presentation | Applicability | Editorial independence | Overall assessment | Recommendation to use | Mortality | Quality of life | Mortality (any comment) and quality of life (any formal measure) |

| 1 | Coleman et al (2012)30 | 63% | 47% | 20% | 37% | 16% | 15% | 31% | Yes 0 No 5 If modified 1 |

Y | Y | M: Higher in post SRS vs matched no SRS, and both pre and post SRS vs gen popn. QoL: FtM<gen popn, FtM post breast/chest surgery >not surgery, mixed results at 15 years. |

| 2 | Davies et al (2015)51 | 62% | 38% | 17% | 61% | 28% | 14% | 28% | Yes 0 No 3 If modified 3 |

N | Y | QoL: A voice-related TG QoL measure correlated with own and others’ perception. |

| 3 | ECDC (2018)58 | 94% | 56% | 55% | 76% | 68% | 38% | 69% | Yes 4 No 0 If modified 2 | Y | Y | M: Reduced by early diagnosis. QoL: Cost/QALY in anti-HCV birth cohort screening is acceptable. Universal offer HIV testing in hospital settings is highly cost effective. |

| 4 | Gilligan et al (2017)52 | 84% | 67% | 66% | 81% | 47% | 61% | 78% | Yes 2 No 0 If modified 4 |

N | N | |

| 5 | Hembree et al (2017)53 | 65% | 40% | 41% | 73% | 29% | 65% | 56% | Yes 1 No 2 If modified 3 |

Y | Y | M: TW/TM’s CV mortality same (‘insufficient very low quality data’ for TM) and younger age at death after SRS. QoL: long-term psychological and psychiatric issues post SRS. |

| 6 | IAPHCCO (2015)54 | 85% | 56% | 61% | 87% | 40% | 63% | 81% | Yes 3 No 0 If modified 3 |

Y | Y | M: Lower if early ART, easy access, immediate ART, and community distribution. QoL: ART preserves QoL, and stigma and mental health impact on QoL. |

| 7 | Ralph et al (2010)56 | 45% | 14% | 19% | 64% | 5% | 32% | 28% | Yes 0 No 5 If modified 1 |

N | N | |

| 8 | Strang et al57 (2018)57 | 57% | 33% | 19% | 39% | 8% | 25% | 11% | Yes 0 No 6 If modified 0 |

N | N | |

| 9 | T’Sjoen et al (2020)55 | 59% | 37% | 35% | 58% | 15% | 33% | 42% | Yes 0 No 4 If modified 2 |

N | Y | QoL: Sexual life improves after GAMI, but not to non-TG levels. |

| 10 | WHO (2011)48 | 94% | 89% | 87% | 86% | 64% | 82% | 83% | Yes 5 No 0 If modified 1 |

Y | Y | M: Looked for mortality evidence but none found. QoL: Positive QALYs if HIV averted. |

| 11 | WHO (2012)49 | 85% | 60% | 81% | 76% | 41% | 72% | 72% | Yes 4 No 0 If modified 2 |

N | Y | QoL: Positive QALYs modelled if PrEP. |

| 12 | WHO (2016)50 | 94% | 93% | 81% | 89% | 84% | 65% | 94% | Yes 5 No 0 If modified 1 |

Y | N | M: Better if access and if adhere to OST, and at prison release; if early ART and completed TB Rx, HBV/ HCV managed; and access to post-abortion care. Worse if food insecure, poor nutrition, low body mass index. |

Colours to aid interpretation (not thresholds) ≤30 RED, 31–69 AMBER, ≥70 GREEN.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CV, cardiovascular; ECDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; FtM, female-to-male; GAMI, gender affirming medical intervention; gen popn, general population; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immuno-deficiency virus; IAPHCCO, International advisory panel on HIV care continuum optimization; M, mortality; OST, opiate substitute therapy; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; QALY, quality adjusted life year; QoL, Quality of life; Rx, treatment; SR, systematic review; SRS, sex reassignment surgery; TB, tuberculosis; TG, trans people/gender-minority; TM, trans man; TW, trans woman.

Content

Four CPGs concerning HIV prevention, transmission and care48–50 54 and one public health guideline on population screening for blood-borne viruses,58 contained recommendations for gender minority/trans people as a ‘key population’. Three CPGs were devoted to overall transition care for all gender minority/trans people,30 53 55 two to an aspect of transition51 56 and one to transition in a specific group.57 One oncology communication guideline contained a single recommendation relating to gender minority/trans people.52 No international guidelines were found that addressed primary care, psychological support/mental health interventions, or general medical/chronic disease care (such as cardiovascular, cancer or elderly care).

Mortality and quality of life

Six CPGs referred to mortality30 48 50 53 54 58 and eight to QoL30 48 49 51 53–55 58 (table 2). Online supplemental table W4 shows all extractions of sentences relating to mortality or morbidity, associated references and which CPGs included no such data. More robust evidence was linked to the recommendations in the HIV and blood-borne virus CPGs whereas there was little, inconsistent data and poorer linking to evidence in transition-related CPGs.

Consistency of recommendations across the CPGs

Online supplemental table W5 contains all extracted key recommendations where these could be distinguished. It shows little overlap of topic content across the CPGs. Many recommendations in WHO 201148 and 201650 were similar, but not identical, the former not being stood down after the latter was published. No statements were highlighted by the WPATH SOCv730 authors as key recommendations, and it proved impossible for all six reviewers independently performing data extraction to identify them. The total number of extracted recommendations ranged between 0 and 168 with little consistency or agreement on what passages were selected. Some extracted statements might have been intended as recommendations or standards, but many were flexible, disconnected from evidence and could not be used by individuals or services to benchmark practice. After discussion of this incoherence within WPATH SOCv730 and our inability therefore to compare recommendations across all CPGs, it was decided not to revisit inclusions post hoc but to abandon this protocol aim.

Patient facing material

No patient-facing material was found in any guideline.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

Variable quality international CPGs regarding gender minority/trans people’s healthcare contain little, conflicting information on mortality and QoL, no patient facing messages and inconsistent use of systematic reviews in generating recommendations. A major finding is that the scope of the guidelines is confined to HIV/STI prevention or management of transition with an absence of guidelines relating to other medical issues. WPATH SOCv730 cannot be considered ‘gold standard’.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

Strengths include protocol preregistration, stakeholder involvement, piloting all stages, an extensive systematic search without language restriction for any relevant current guidelines, wide inclusion criteria including grey literature, use of key opinion leaders, close attention to avoidance of bias, double full-text reading and data entry and careful presentation of results. Six trained reviewers, exceeding AGREE II recommendations,11 compensated for expected variation in scoring. Extensive searches should have mitigated loss of CPGs. Limitations include some uncertainty about stakeholder understanding despite a good response rate, and generalisability of the prioritisation only to the UK; stakeholders elsewhere might have different priorities. Focusing only on international CPGs might have missed higher quality national and local CPGs derived from them or written de novo. The social acceptance and consequent healthcare system coverage of gender minority/trans health related interventions vary among different countries, which may limit the space for international and multinational guidelines. While the search strategy yielded an oncology communication CPG with a single recommendation for gender minority/trans people,52 other general health CPGs with similar solo statements might have been missed.

Comparison with other studies, discussing important differences in results

This is the first systematic review using a validated quality appraisal instrument of international CPGs addressing gender minority/trans health. It may act as a benchmark to monitor and improve population healthcare. CPG quality results correspond with, and quantitatively confirm, previously noted concerns about the evidence-base36 62 63 and variable use of quality assessment in systematic reviews,64–66 in a healthcare field with unknown or unclear longitudinal outcomes.17 AGREE II has been applied to CPGs in other medical areas, including cancer,67 diabetes,68 pregnancy69 and depression.70 These exercises tend to show room for improvement. Developers have been criticised for not using methodological rigour when writing reliable evidence-based guidelines,71 as well as not implementing high-quality CPGs.72 Thus, finding poor quality CPGs is not confined to this area of healthcare.73 Improvement messages are generalisable to other specialties.

Meaning of the study: possible explanations

The finding of higher-quality, but narrow, focus on gender minority/trans people’s healthcare for blood-borne infections may relate to the global HIV pandemic and the WHO applying twin lenses of public health and human rights (ie, the population as ‘means’ and ‘ends’). The lower-quality CPGs focus on transition. WPATH SOCv730 originated nearly a decade ago from a special-interest association; diagnostic criteria and CPG methodology have since changed. Although HIV and transition are important, it is puzzling to have found so little else, maybe suggesting CPGs for gender minority/trans people have been driven by provider-interests rather than healthcare needs. Including gender minority/trans people in guidelines can be considered a matter of health equity, where CPGs have a role to play.74 GRADE suggests CPG developers may consider equity at various stages in creating guidelines, such as deciding guideline questions, evidence searching and assembly of the guideline group.75 How CPGs may impact more vulnerable members of society should be reflected-upon during guideline development,76 and implementation.77

Implications for clinicians, UK and international policymakers and patients

Clinicians should be made aware that gender minority/trans health CPGs outside of HIV-related topics are linked to a weak evidence base, with variations in methodological rigour and lack of stakeholder involvement. While patient care plans ought to take into account the individual needs of each gender minority/trans person, a gap appears to exist between clinical practice and research in this field.78 Clinicians should proceed with caution, explain uncertainties to patients and recruit to research.

Policymakers ought to invest in both primary research and high-quality systematic reviews in areas relevant for CPG and service development. Organisations producing guidelines and aspiring to higher-level quality could use more robust methods, handling of competing interests79 80 and quality assessment. CPG developers should label key recommendations clearly. Although editorial independence was lowest priority for stakeholders, independent external review is important to avoid biases and bad practices, examine use of resources, resist commercial interests and gain widespread credibility outside the field.

The UK is fortunate in being familiar with developing priority-setting partnerships (eg, James Lind Initiative81) and generating suites of clinical questions that might cover all steps in patient pathways (eg, in partnership with Cochrane Collaboration82). These could underpin multidisciplinary and funded research priorities whose results feed into future better evidence-based CPGs. Implications for UK education and curricular content (eg, new gender identity healthcare credentials83), should be carefully scrutinised.

Internationally, CPG development and implementation will vary depending on local country contexts and available resources. Those countries with quality assurance agencies might use them for external assurance. Countries might reconsider the wisdom of adapting low-quality ‘off the shelf’ international CPGs without due assessment of the evidence for recommendations (eg, using the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT framework84). WHO demonstrates how CPGs can achieve high quality.

Patients should be positively encouraged to engage with CPG development as stakeholders. The lack of patient-facing material should be addressed, especially as medical and non-medical online material contains jargon, is unreliable and potentially misleading.85 Future CPGs should be populated with patient-facing decision aids (eg, fact boxes86 and icon arrays87) that explain sizes of benefits and harms to support informed patient choice. Patients and carers will benefit from a more focused approach to throughout-life healthcare. As the figures for gender minority/trans patients increase within the NHS and internationally, so does the need for consistent guidance to clinicians across specialisms on specific risks to, and means of treating, this population. Current patients should be welcomed to contribute, where they are comfortable, to any research being undertaken by their clinicians, in order to improve data and future practice for gender minority/trans health.

Unanswered questions and future research

This study should be replicated as new iterations of international CPGs become available. It can be applied to national guidelines and countries should perform their own stakeholder prioritisation. When ‘best available evidence’ is poor, quality improvement can be driven both from inside and outside the field. International guideline developers require more primary research for this population, and impetus from clinicians and scientists to build a better evidence base using robust data from randomised controlled trials and long-term observational cohort studies, especially regarding chronic diseases, health behaviours, substance use, screening and how interventions (eg, hormones) might impact on long-term health (eg, risk of cardiovascular and thromboembolic disease). Mortality and QoL data are required to address questions of clinical and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion

Gender minority/trans health in current international CPGs seems limited to a focus on HIV or transition-related interventions. WPATH SOCv730 is due for updating and this study should be used positively to accelerate improvement. Future guideline developers might better address the holistic healthcare needs of gender minority/trans people by enhancing the evidence-base, upgrading the quality of CPGs and increasing the breadth of health topics wherein this population is considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Wakeford and Leena Järveläinen (information specialists, British Library and Turku University Library), Gillian Claire Evans (German translations), Sarah Peitzmeier, Sam Winter, Christina Richards and Riittakerttu Kaltiala (opinion leaders), Paul Seed (statistician), researchers who shared copies of their papers, the UK stakeholders who participated in the prioritisation exercise and the peer reviewers whose feedback improved the work.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors were involved as follows: SB, IA, CM conception. All authors (SD, DC, IA, MHJ, SB, CM) were involved in design, execution, analysis, drafting manuscript and critical discussion; all were responsible for revision and final approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CM acts as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available upon request.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine . Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kredo T, Bernhardsson S, Machingaidze S, et al. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:122–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzv115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, et al. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:527–30. 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995–8. 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siemieniuk R, Guyatt G. What is GRADE? BMJ Best Pract. Available: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/ [Accessed 23 Nov 2020].

- 8.GRADE Working Group . GRADE publications, 2020. Available: https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/ [Accessed 15 Aug 2020].

- 9.Siemieniuk R. Rapid recommendations: improving the efficiency and trustworthiness of systematic reviews and guidelines, 2020. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25540

- 10.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing Guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Can Med Assoc J 2010;182:E839–42. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AGREE Next Steps Consortium . The AGREE II Instrument [Electronic version]., 2017. Available: http://www.agreetrust.org [Accessed 14 Jul 2020].

- 12.AGREE Collaboration . Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:18–23. 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trevisiol C, Cinquini M, Fabricio ASC, et al. Insufficient uptake of systematic search methods in oncological clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:180. 10.1186/s12874-019-0818-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plöderl M, Hengartner MP. Guidelines for the pharmacological acute treatment of major depression: conflicts with current evidence as demonstrated with the German S3-guidelines. BMC Psychiatry 2019;19:265. 10.1186/s12888-019-2230-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maes-Carballo M, Mignini L, Martín-Díaz M, et al. Quality and reporting of clinical guidelines for breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Breast 2020;53:201–11. 10.1016/j.breast.2020.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . WHO/Europe brief – transgender health in the context of ICD-11. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/gender/gender-definitions/whoeurope-brief-transgender-health-in-the-context-of-icd-11 [Accessed 16 Jul 2020].

- 17.Butler G, De Graaf N, Wren B, et al. Assessment and support of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:631–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaltiala-Heino R, Bergman H, Työläjärvi M, et al. Gender dysphoria in adolescence: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2018;9:31–41. 10.2147/AHMT.S135432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Freitas LD, Léda-Rêgo G, Bezerra-Filho S, et al. Psychiatric disorders in individuals diagnosed with gender dysphoria: a systematic review. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:99–104. 10.1111/pcn.12947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connolly D, Davies E, Lynskey M, et al. Comparing intentions to reduce substance use and willingness to seek help among transgender and cisgender participants from the global drug survey. J Subst Abuse Treat 2020;112:86–91. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Katz M. Attempted suicide among transgender persons. J Homosex 2006;51:53–69. 10.1300/J082v51n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catelan RF, Costa AB, Lisboa CSdeM. Psychological interventions for transgender persons: a scoping review. Int J Sex Heal 2017;29:325–37. 10.1080/19317611.2017.1360432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glynn TR, van den Berg JJ. A systematic review of interventions to reduce problematic substance use among transgender individuals: a call to action. Transgend Health 2017;2:45–59. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poteat T, Reisner SL, Radix A. HIV epidemics among transgender women. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9:168–73. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter S, Diamond M, Green J, et al. Transgender people: health at the margins of society. Lancet 2016;388:390–400. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00683-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S. The report of the US Transgender Survey 2015. Washington, DC: National Center for Healthcare Equality, 2016. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, et al. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health 2013;103:943–51. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.OHCHR . Discrimination and violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, 2015. Available: https://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/29/23

- 29.Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet 2016;388:412–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend 2012;13:165–232. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wylie K, Knudson G, Khan SI, et al. Serving transgender people: clinical care considerations and service delivery models in transgender health. Lancet 2016;388:401–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00682-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dahl M, Feldman JL, Goldberg J. Endocrine therapy for transgender adults in British Columbia: suggested guidelines physical aspects of transgender endocrine therapy; 2015.

- 33.Oliphant J, Veale J, Macdonald J, et al. Guidelines for gender affirming healthcare for gender diverse and transgender children, young people and adults in Aotearoa, New Zealand. N Z Med J 2018;131:86–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Psychological Society of South Africa . Practice guidelines for psychology professionals working with sexually- and gender-diverse people. Johannesburg: Psychological Society of South Africa, 2017. https://www.psyssa.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PsySSA-Diversity-Competence-Practice-Guidelines-PRINT-singlesided.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.UCSF Transgender Care . Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. 2nd edn. San Francisco: Department of Family and Community Medicine University of California San Francisco, 2016. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deutsch MB, Radix A, Reisner S. What's in a guideline? Developing collaborative and sound research designs that substantiate best practice recommendations for transgender health care. AMA J Ethics 2016;18:1098–106. 10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.11.stas1-1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gender Identity Research and Education Society . What we do. Available: https://www.gires.org.uk/what-we-do/improving-medical-care/ [Accessed 18 Nov 2020].

- 38.Ahmad S, Barrett J, Beaini AY, et al. Gender dysphoria services: a guide for general practitioners and other healthcare staff. Sex Relatsh Ther 2013;28:172–85. 10.1080/14681994.2013.808884 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wylie K, Barrett J, Besser M, et al. Good practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of adults with gender dysphoria. Sex Relatsh Ther 2014;29:154–214. 10.1080/14681994.2014.883353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.RCGP . The role of the GP in caring for gender-questioning and transgender patients. RCGP Position Statement, 2019. Available: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/2019/RCGP-position-statement-providing-care-for-gender-transgender-patients-june-2019.ashx?la=en [Accessed 23 Nov 2020].

- 41.Hoffmann-Eßer W, Siering U, Neugebauer EAM, et al. Guideline appraisal with AGREE II: systematic review of the current evidence on how users handle the two overall assessments. PLoS One 2017;12:e0174831. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siering U, Eikermann M, Hausner E, et al. Appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e82915. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network . What are guidelines? Sign. Available: https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-are-guidelines [Accessed 16 Jul 2020].

- 45.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . How NICE clinical guidelines are developed: an overview for stakeholders, the public and the NHS. NICE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Institute of Medicine . Guidelines for clinical practice: from development to use. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO . Prevention and treatment of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men and transgender people: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/msm_guidelines2011/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO . Guidance on oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for serodiscordant couples, men and transgender women who have sex with men at high risk of HIV: recommendations for use in the context of demonstration projects. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidance_prep/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO . Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, 2016 update, 2016. Available: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations/ [PubMed]

- 51.Davies S, Papp VG, Antoni C. Voice and communication change for gender nonconforming individuals: giving voice to the person inside. Int J Transgend 2015;16:117–59. 10.1080/15532739.2015.1075931 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3618–32. 10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3869–903. 10.1210/jc.2017-01658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.International Advisory Panel on HIV Care Continuum Optimization . IAPAC guidelines for optimizing the HIV care continuum for adults and adolescents. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2015;14(Suppl 1):S3–34. 10.1177/2325957415613442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.T'Sjoen G, Arcelus J, De Vries ALC, et al. European Society for Sexual Medicine Position Statement "Assessment and Hormonal Management in Adolescent and Adult Trans People, With Attention for Sexual Function and Satisfaction". J Sex Med 2020;17:570–84. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ralph D, Gonzalez-Cadavid N, Mirone V, et al. Trauma, gender reassignment, and penile augmentation. J Sex Med 2010;7:1657–67. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01781.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strang JF, Meagher H, Kenworthy L, et al. Initial clinical guidelines for co-occurring autism spectrum disorder and gender dysphoria or incongruence in adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2018;47:105–15. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1228462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.ECDC . European centre for disease prevention and control. public health guidance on HIV, hepatitis B and C testing in the EU/EEA: an integrated approach. Stockholm, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jungwirth A, Diemer T, Kopa Z, et al. EAU guidelines on male infertility. European Association of Urology, 2018. https://uroweb.org/guideline/male-infertility/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thoreson N, Marks DH, Peebles JK, et al. Health insurance coverage of permanent hair removal in transgender and gender-minority patients. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:561. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solotke MT, Liu P, Dhruva SS, et al. Medicare prescription drug plan coverage of hormone therapies used by transgender individuals. LGBT Health 2020;7:137–45. 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fraser L, Knudson G. Past and future challenges associated with standards of care for gender transitioning clients. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017;40:15–27. 10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shuster SM. Uncertain expertise and the limitations of clinical guidelines in transgender healthcare. J Health Soc Behav 2016;57:319–32. 10.1177/0022146516660343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Velho I, Fighera TM, Ziegelmann PK, et al. Effects of testosterone therapy on BMI, blood pressure, and laboratory profile of transgender men: a systematic review. Andrology 2017;5:881–8. 10.1111/andr.12382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maraka S, Singh Ospina N, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Sex steroids and cardiovascular outcomes in transgender individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017;102:3914–23. 10.1210/jc.2017-01643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Connolly D, Hughes X, Berner A. Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among transgender men and non-binary people with a cervix: a systematic narrative review. Prev Med 2020;135:106071. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lei X, Liu F, Luo S, et al. Evaluation of guidelines regarding surgical treatment of breast cancer using the AGREE instrument: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014883. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhatt M, Nahari A, Wang P-W, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines for management of pediatric type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review using the AGREE II instrument. Syst Rev 2018;7:193. 10.1186/s13643-018-0843-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bazzano AN, Green E, Madison A, et al. Assessment of the quality and content of national and international guidelines on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy using the AGREE II instrument. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009189. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacQueen G, Santaguida P, Keshavarz H, et al. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for failed antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder, Dysthymia, and subthreshold depression in adults. Can J Psychiatry 2017;62:11–23. 10.1177/0706743716664885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e58. 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bewley S. What inhibits obstetricians implementing reliable guidelines? BJOG 2020;127:798. 10.1111/1471-0528.16177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grilli R, Magrini N, Penna A, et al. Practice guidelines developed by specialty societies: the need for a critical appraisal. Lancet 2000;355:103–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02171-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Welch VA, Akl EA, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE Equity Guidelines 1: considering health equity in GRADE Guideline development: introduction and rationale. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;90:59–67. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akl EA, Welch V, Pottie K, et al. GRADE Equity Guidelines 2: considering health equity in GRADE Guideline development: equity extension of the Guideline Development Checklist. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;90:68–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Welch VA, Akl EA, Pottie K, et al. GRADE Equity Guidelines 3: considering health equity in GRADE Guideline development: rating the certainty of synthesized evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;90:76–83. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pottie K, Welch V, Morton R, et al. GRADE Equity Guidelines 4: considering health equity in GRADE Guideline development: evidence to decision process. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;90:84–91. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Haupt C, Henke M, Kutschmar A, et al. Antiandrogen or estradiol treatment or both during hormone therapy in transitioning transgender women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;11:CD013138. 10.1002/14651858.CD013138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ioannidis JPA. Professional societies should abstain from authorship of guidelines and disease definition statements. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018;11:e004889. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ioannidis JPA. Guidelines do not entangle practitioners with unavoidable conflicts as authors, and when there is no evidence, just say so. Circulation 2018;11. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.James Lind Alliance . About priority setting partnerships. Available: http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/about-the-james-lind-alliance/about-psps.htm [Accessed 8 Jul 2020].

- 82.Thomas J, Kneale D, McKenzie J. Chapter 2: Determining the scope of the review and the questions it will address. : Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, . Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane, 2020. www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- 83.Royal College of Physicians . Gender identity healthcare credentials (GIH). London: RCP, 2020. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/education-practice/courses/gender-identity-healthcare-credentials-gih [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schünemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Brozek J, et al. GRADE evidence to decision (ETD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:101–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dunford C, Gresty H, Takhar M, et al. Transgender and adolescence: is online information accurate or mis-leading? Eur Urol Suppl 2019;18:e1782. 10.1016/S1569-9056(19)31291-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harding Center for Risk Literacy . Fact boxes. Available: https://www.hardingcenter.de/en/fact-boxes [Accessed 8 Jul 2020].

- 87.Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication . Available: https://wintoncentre.maths.cam.ac.uk/ [Accessed 8 Jul 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-048943supp001.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available upon request.