Abstract

Background

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are used to manage hypertension which is highly prevalent among people with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The treatment for hypertension is particularly challenging in people undergoing dialysis.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of calcium channel blockers in patients with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies to 27 April 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Specialised Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared any type of CCB with other CCB, different doses of the same CCB, other antihypertensives, control or placebo were included. The minimum study duration was 12 weeks.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed study quality and extracted data. Statistical analyses were performed using a random‐effects model and results expressed as risk ratio (RR), risk difference (RD) or mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

This review included 13 studies (24 reports) randomising 1459 participants treated with long‐term haemodialysis. Nine studies were included in the meta‐analysis (622 participants). No studies were performed in children or in those undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Overall, risk of bias was assessed as unclear to high across most domains.

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were at low risk of bias in eight and one studies, respectively. Two studies reported low risk methods for blinding of participants and investigators, and outcome assessment was blinded in 10 studies. Three studies were at low risk of attrition bias, eight studies were at low risk of selective reporting bias, and five studies were at low risk of other potential sources of bias. Overall, the certainty of the evidence was low to very low for all outcomes. No events were reported for cardiovascular death in any of the comparisons. Other side effects were rarely reported and studies were not designed to measure costs.

Five studies (451 randomised adults) compared dihydropyridine CCBs to placebo or no treatment. Dihydropyridine CCBs may decrease predialysis systolic (1 study, 39 participants: MD ‐27.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐43.33 to ‐10.67; low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure level (2 studies, 76 participants; MD ‐13.56 mmHg, 95% CI ‐19.65 to ‐7.48; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or no treatment. Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to occurrence of intradialytic hypotension (2 studies, 287 participants; RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.15; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or no treatment. Other side effects were not reported.

Eight studies (1037 randomised adults) compared dihydropyridine CCBs to other antihypertensives. Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic (4 studies, 180 participants: MD 2.44 mmHg, 95% CI ‐3.74 to 8.62; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure (4 studies, 180 participants: MD 1.49 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.23 to 5.21; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) compared to other antihypertensives. There was no evidence of a difference in the occurrence of intradialytic hypotension (1 study, 92 participants: RR 2.88, 95% CI 0.12 to 68.79; very low certainty evidence) between dihydropyridine CCBs to other antihypertensives. Other side effects were not reported.

Dihydropyridine CCB may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic (1 study, 40 participants: MD ‐4 mmHg, 95% CI ‐11.99 to 3.99; low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure (1 study, 40 participants: MD ‐3.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.06 to 1.06; low certainty evidence) compared to non‐dihydropyridine CCB. There was no evidence of a difference in other side effects (1 study, 40 participants: RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.36; very low certainty evidence) between dihydropyridine CCB and non‐dihydropyridine CCB. Intradialytic hypotension was not reported.

Authors' conclusions

The benefits of CCBs over other antihypertensives on predialysis blood pressure levels and intradialytic hypotension among people with CKD who required haemodialysis were uncertain. Effects of CCBs on other side effects and cardiovascular death also remain uncertain. Dihydropyridine CCBs may decrease predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure level compared to placebo or no treatment. No studies were identified in children or peritoneal dialysis. Available studies have not been designed to measure the effects on costs. The shortcomings of the studies were that they recruited very few participants, had few events, had very short follow‐up periods, some outcomes were not reported, and the reporting of outcomes such as changes in blood pressure was not done uniformly across studies.

Well‐designed RCTs, conducted in both adults and children with CKD requiring both haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis, evaluating both dihydropyridine and non‐dihydropyridine CCBs against other antihypertensives are required. Future research should be focused on outcomes relevant to patients (including death and cardiovascular disease), blood pressure changes, risk of side effects and healthcare costs to assist decision‐making in clinical practice.

Plain language summary

Calcium channel blockers for people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis

What is the issue? People with long‐term kidney disease or chronic kidney disease (CKD) often develop high blood pressure (hypertension), and those with advanced CKD need dialysis when their kidneys are no longer unable to function. Treatment for hypertension is often challenging for people with advanced CKD undergoing dialysis. Several medications are used to treat high blood pressure including calcium channel blockers (CCBs).

We wanted to find out whether the use of CCBs in people with CKD undergoing haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis had any added benefits over other medications used to treat hypertension or placebo (no active treatment) in lowering the blood pressure, risk of death and undesired effects.

What did we do? We searched the literature up to April 2020 to identify all studies that assessed the use of CCBs in adults and children with hypertension and CKD undergoing haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Each study was assessed for possible bias on several pre‐determined domains. We pooled the results of studies that reported on the same outcomes for similar comparisons and reported the overall effects. We applied a system called "GRADE" to assess the quality of the evidence that we found.

What did we find? We included 13 studies randomising 1459 adults undergoing haemodialysis. We did not find any studies in children and there were no studies in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Patients were randomised to CCBs, other medications used to treat hypertension, or placebo or standard care. Some studies were short‐term (over few months) and heart‐related complications were not assessed. The benefit of CCBs over other medications was unclear, possibly due to the small number of participants and the overall number of events. When compared to placebo or no treatment CCBs may decrease blood pressure before haemodialysis, although the quality of the evidence was low.

Conclusions The benefits of CCBs over other medications to treat hypertension could not be determined, while CCBs may lower blood pressure compared to placebo or usual care.

Summary of findings

Background

CKD is a growing health concern associated with a high risk of adverse outcomes. Its global prevalence is increasing at a rate of 8% per year (Ruilope 2008). CKD aetiology differs by region, age, gender, and race. In Europe, Japan and the United States, diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of CKD, while in the developing world, chronic glomerulonephritis and systemic hypertension are the leading causes (Ruilope 2008). Hypertension as a complication is highly prevalent in patients who have end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD). In India, a population‐based study determined that the crude and age‐adjusted ESKD rates were 151 and 232 per million population, respectively. The number of patients requiring dialysis in India has been estimated at 55,000 with an annual growth rate of between 10% and 20% (Jha 2013).

From the 1990s, there has been an increase in CKD incidence of unknown aetiologies observed in several countries ‐ El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Egypt, and India. The disease seems to have a predominance in young male farm workers and the most common aetiology was chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (Almaguer 2014; Wanigasuriya 2014).

Studies in East Africa revealed a prevalence of hypertension ranging between 61.5% and 76% among patients with varying degrees of CKD (Maritim 2007; Rajula 2009) which illustrated the inadequacy of blood pressure control in this population. It is imperative therefore to ensure adequate blood pressure control in patients with ESKD requiring dialysis. This entails the use of appropriate antihypertensives to provide better health outcomes.

Description of the condition

CKD is defined as the progressive loss of kidney function occurring over several months to years and is characterised by gradual kidney scarring (Dipiro 2011). CKD is categorised by the level of kidney function into stages 1 to 5 as proposed by the widely‐accepted United States Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI); staging is determined by the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Levey 2003).

The more recently published Kidney Disease Improving Guidelines Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of CKD have a slightly different staging of CKD. They recommend that CKD be classified based on the cause, GFR category and albuminuria category (CGA). GFR categories are classified as G1, G2, G3a, G3b, G4 and G5 (Eknoyan 2013).

Data from the 1998 to 2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) revealed a rise in CKD prevalence. Prevalence rose in people aged over 20 years from 14.5% in 1988 to 16.8% in 1994 (Onuigbo 2009). The 2003 to 2006 survey reported an increase in stage 3 CKD prevalence from 5.7% in 1988 to 8.1% in 1994 (Dipiro 2011).

Description of the intervention

CCBs are antihypertensive agents that act on both myocardial cells and blood vessels. CCBs are classified broadly as either dihydropyridine or non‐dihydropyridine types. Dihydropyridine CCBs include nifedipine, which is the prototype in this group; others include amlodipine, felodipine, isradipine, nicardipine, nimodipine, nitrendipine, nisoldipine, efonipidine and cilnidipine. The non‐dihydropyridine subclass includes diltiazem and verapamil which are the prototypes for the benzodiazepine and phenylalkylamine class of CCB. Gallopamil, a derivative of verapamil, is also classified as a non‐dihydropyridine CCB (Hart 2008).

How the intervention might work

CCBs are vasodilators, although vasodilatory ability is not equal across all classes; the dihydropyridine CCBs are more potent than non‐dihydropyridine CCBs (Sica 2005).

Both CCBs classes inhibit two types of voltage dependent channels: a high voltage activated calcium channel including P/Q, L, N, and R type channels, and low voltage activated T type channel (Hart 2008). By preferentially binding to L type channels in the vasculature, dihydropyridine CCBs cause vasodilatation and subsequent drop in blood pressure. The non‐dihydropyridine CCBs bind preferentially to L type channels in the cardiac muscles, more so on the sino‐atrial and atrioventricular nodes, causing negative chronotropic effects and decreasing sympathetic nervous system activity. These effects cause blood pressure to decrease (Basile 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

Most people undergoing dialysis have hypertension that is difficult to control; this contributes to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (Inrig 2010; Van Buren 2012). The reported prevalence of hypertension among people on dialysis was 86% in an American cohort of 2535 clinically stable, adults on dialysis. Of these, only 30% had adequately controlled blood pressure (Agarwal 2003). Drugs used before development of ESKD may no longer provide viable options. Some drugs are dialyzable and use would result in a rise in blood pressure during dialysis (Inrig 2010; Van Buren 2012). Clinicians are faced with the challenge of choosing an appropriate therapy for controlling blood pressure for people with ESKD undergoing dialysis.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of calcium channel blockers in patients with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) looking at the effects of CCB on blood pressure control in patients with CKD undergoing dialysis. The minimum study duration was 12 weeks. Cross‐over studies were excluded unless they had a washout period between treatments.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

All patients with CKD requiring dialysis (stage 5 as defined by the K/DOQI guidelines (Levey 2003) or stage G5 as defined by the KDIGO guidelines (Eknoyan 2013). We included patients who underwent either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. There were no restrictions on age, gender, or race.

The participants were comorbid with hypertension as defined by the seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC VII) (Chobanian 2003). Participants with or without diabetes (either type 1 or 2) were included. Patients with heart failure as classified by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) stages I to IV and angina were included.

Exclusion criteria

Kidney transplant patients and patients with CKD stages 1 to 4 and stages G1 to G4 as per the K/DOQI guidelines (Levey 2003) and KDIGO guidelines (Eknoyan 2013) respectively were excluded. Studies where follow‐up was less than 12 weeks were excluded.

Types of interventions

Any type of CCB compared with other CCB, different doses of the same CCB, other antihypertensives, or placebo/control/usual treatment were included. Intervention types were to be assessed as follows.

-

CCB versus placebo/control/usual treatment

Dihydropyridine CCB versus placebo/control/usual treatment

Non‐dihydropyridine CCB versus placebo/control/usual treatment

-

CCB versus CCB

Dihydropyridine CCB versus dihydropyridine CCB

Dihydropyridine CCB versus non‐dihydropyridine CCB

Non‐dihydropyridine CCB versus non‐dihydropyridine CCB

-

Different doses of CCB

Dihydropyridine CCB

Non‐dihydropyridine CCB

-

CCB versus other antihypertensives

Dihydropyridine CCB versus other antihypertensives

Non‐dihydropyridine CCB versus other antihypertensives

The review was amended as newer drugs that had been licensed become available. All drugs were administered orally. The dosages were those that were required for control of hypertension or appropriately adjusted dosages for reduced GFR and dialysis.

Combination preparations with other antihypertensives other than CCB were not included.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Cardiovascular death

Predialysis blood pressure (systolic and diastolic)

Intradialytic hypotension.

Secondary outcomes

Incidence of other adverse events (e.g. reflex tachycardia, headache, constipation, bradycardia and heart block, myocardial infarction) related to the interventions

Cost: total healthcare costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies to 27 April 2020 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov

Studies contained in the Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts are available in the "Specialised Register" section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may have been relevant to the review. The titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable, however studies and reviews that might have included relevant data or information on trials were retained initially. Two authors independently assessed retrieved abstracts and, if necessary, the full text, of these studies to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. The two authors compared their lists and any differences were resolved by discussion and, where this failed, by arbitration by a third author.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study exists, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data was used. Any discrepancy between published versions was highlighted. Differences in opinion on data collection was resolved by discussion and, where this failed, by arbitration by a third author.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. death, adverse events such as hypotension, cardiovascular death) results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (blood pressure), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales had been used. Studies that reported change from baseline scores were meta‐analysed with studies reporting final value scores using the mean difference. In this case, if standard deviation of change was not reported, this was imputed (Higgins 2011). Studies that reported time to event of outcomes as hazard ratios and CIs were meta‐analysed with studies that reported risk ratios where the proportional hazards assumption was reasonable. Otherwise, these studies were analysed as dichotomous data.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not foresee the use of non‐standard design studies such as cross‐over trials and cluster‐RCTs would be included in the review. However, multiple arm studies were found and included. In such cases, all intervention groups that were relevant to the review were included.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence (e.g. emailing the corresponding author) and any relevant information obtained in this manner was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per‐protocol (PP) population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward (LOCF)) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi² test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I² test (Higgins 2003). I² values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium, and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If possible, funnel plots were to be used to assess for the potential existence of small study bias (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity (e.g. participants, interventions, and study quality). Heterogeneity among participants could have been related to age, gender, ethnicity/race, renal pathology, type of dialysis and co morbidities (CVD, hypertension, diabetes mellitus). Heterogeneity in treatments could have been related to prior agents used and the agent, dose, and duration of therapy. Adverse effects were tabulated and assessed with descriptive techniques, as they were likely to be different for the various agents used. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was calculated for each adverse effect, either compared with no treatment or another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies;

repeat the analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias;

repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results;

repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Predialysis systolic blood pressure

Predialysis diastolic blood pressure

Cardiovascular death

Intradialytic hypotension

Other side effects.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

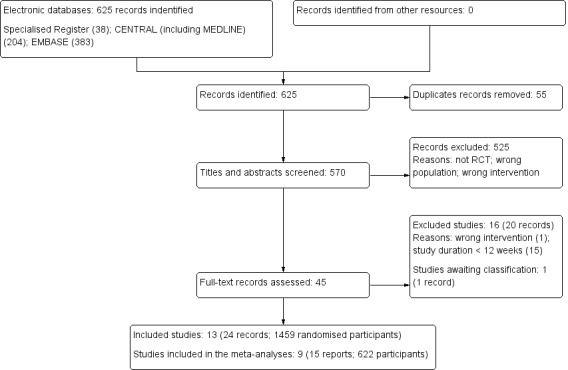

Our search identified 625 reports; 55 duplicate records were deleted. We screened 570 titles and abstracts and excluded 525 records which did not meet our inclusion criteria (not randomised, wrong population, or wrong intervention). We assessed 45 full text reports and excluded a further 20 reports (16 studies). One study (recently completed but not published) has been listed as awaiting classification (NCT01394770). We included 13 studies (24 reports) randomising 1459 participants; nine studies (15 reports; 622 participants) were included in our meta‐analyses.

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

Twelve studies evaluated dihydropyridine CCBs (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002; Tepel 2008; Yilmaz 2010a), and one study (Timio 1997) compared dihydropyridine CCBs to non‐dihydropyridine CCBs.

Kozlova 2006 was a four‐arm study compared amlodipine either to an ACEi (perindopril), dual therapy or no intervention, while Shibasaki 2002 was a three arms study compared amlodipine either to an ACEi (enalapril) or an ARB (losartan).

Dihydropyridine CCB versus placebo or no treatment

Five studies compared dihydropyridine CCB to placebo or no treatment. London 1990 (40 participants) and Marchais 1991 (40 participants) compared nitrendipine to placebo; Tepel 2008 (251 participants) compared amlodipine to placebo; Kozlova 2006 (37 participants) compared amlodipine to no treatment; and LONDON 2019 (51 participants) compared cilnidipine to no treatment.

The outcomes assessed were predialysis systolic (London 1990) and diastolic blood pressure (Kozlova 2006; London 1990), cardiovascular death (London 1990; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991), and intradialytic hypotension (LONDON 2019; Tepel 2008).

Dihydropyridine CCB versus non‐dihydropyridine CCB

Timio 1997 (40 participants) compared dihydropyridine CCB (amlodipine) to a non‐dihydropyridine CCB (verapamil).

The outcomes assessed were predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cardiovascular death, and other side effects (including headache).

Dihydropyridine CCB versus other antihypertensives

Eight studies (1037 participants) compared a dihydropyridine CCB to ACEi (including enalapril, trandolapril, perindopril and ramipril) (Albitar 1997; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; London 1994; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002; Yilmaz 2010a) or an ARB (telmisartan or losartan) (Das 2003; Shibasaki 2002).

Outcomes reported were changes in changes in predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Albitar 1997; London 1994; Kozlova 2006; Yilmaz 2010a), cardiovascular death (Albitar 1997; London 1994; Yilmaz 2010a), and intradialytic hypotension (Yilmaz 2010a)

Das 2003 (47 participants) compared lercanidipine to ARB (telmisartan) and Shibasaki 2002 (39 participants) compared amlodipine to both enalapril and losartan, however no outcome data were extractable.

Excluded studies

We excluded 16 studies (20 reports); 15 studies did not have the required follow‐up period (Aslam 2006; Atabak 2013; Cice 1997; Cice 1998; Cice 2003; EDIT 2011; Kojima 2004; Nakano 2010; Rojas‐Campos 2005; Salvetti 1987; Schiffl 1991; Sherman 1990; Singhaton 2001; Soni 2000; Zuccala 1988) and one study used an inappropriate intervention (NCT02228408). See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Studies awaiting classification

NCT01394770 was registered in 2009 but never published; it was registered more than 10 years ago however its current recruitment status is listed as unknown; therefore, we have assessed it as awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

Our search did not identify any ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, the risk of bias in the included studies are reported in Figure 2, whilst the risk of bias in each study is shown in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Eight studies were judged to be at low risk of selection bias since they reported an appropriate random sequence generation procedure (London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Shibasaki 2002; Tepel 2008; Timio 1997; Yilmaz 2010a). The remaining five studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; Nakao 1999).

Allocation concealment

Tepel 2008 was judged to be at a low risk of bias related to allocation concealment, while the remaining 12 studies were judged to be at unclear risk of bias (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002; Timio 1997; Yilmaz 2010a).

Blinding

Performance bias

Two studies (London 1994; Tepel 2008) were blinded and judged to be at low risk of bias. Eight studies were not blinded and were at high risk of performance bias (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Timio 1997; Yilmaz 2010a), while the risk of bias in three studies (London 1990; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002) was judged to be uncertain.

Detection bias

Ten studies were judged to be at low risk of bias due to blinding of outcome assessors (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; Kozlova 2006; London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Shibasaki 2002; Tepel 2008; Timio 1997). There studies were adjudicated to be at high risk of detection bias (HEART 2003; Nakao 1999; Yilmaz 2010a).

Incomplete outcome data

Three studies (Albitar 1997; Tepel 2008; Timio 1997) were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias. Seven studies were considered at high risk due to incomplete outcome data (Kozlova 2006; London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Shibasaki 2002; Yilmaz 2010a). The remaining three studies were considered to be at unclear risk of bias (Das 2003; HEART 2003; Nakao 1999).

Selective reporting

Eight studies published data on all expected outcomes and were considered to be at low risk of reporting bias (London 1990; London 1994; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Shibasaki 2002; Tepel 2008; Timio 1997; Yilmaz 2010a). Five studies (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; Nakao 1999) were only available as abstracts and were considered to be at high risk of bias. In addition, Kozlova 2006 failed to report some outcomes related to the control group.

Other potential sources of bias

Five studies were judged to be at low risk from other potential sources of bias (London 1994; Shibasaki 2002; Tepel 2008; Timio 1997; Yilmaz 2010a). Eight studies were assessed to be at high risk of other potential sources of bias. Three studies (London 1990; LONDON 2019, Marchais 1991) were funded by pharmaceutical companies or authors had conflict of interests, and this may have introduced some bias. Other potential sources of bias included abstract‐only publications in five studies (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; Nakao 1999).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus placebo/control in people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis.

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus placebo/control in people with CKD requiring dialysis | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD requiring dialysis

Setting: France, Germany, Japan, Russia Intervention: dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, cilnidipine or nitrendipine) Comparison: placebo/control | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Placebo/control | Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | ||||

| Predialysis systolic blood pressure follow‐up 3.7 months | The mean predialysis systolic blood pressure level in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group was 27.00 mmHg lower (43.33 to 10.67 mmHg lower) than the placebo group 1 | ‐ | 39 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2,3 | |

| Predialysis diastolic blood pressure mean follow‐up 4.9 months | The mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure level in the placebo/control group ranged from 98 to 104.1 mmHg The mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure level in the placebo/control group was 13.56 mmHg lower (19.65 to 7.48 mmHg lower) |

‐ | 76 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 3,4 | |

|

Cardiovascular death mean follow‐up 3.4 months |

No events 5 | No events | Not estimable | 124 (3) | ‐ |

|

Intradialytic hypotension mean follow‐up 16.4 months |

122 per 1000 | 66 per 1000 (31 to 141) | RR 0.54 (0.25 to 1.15) | 287 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 3,6 |

| Other side effects | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: Chronic kidney disease; HD: Haemodialysis; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Studies were not designed to measure effects of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers on predialysis systolic blood pressure level in haemodialysis 2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. The study had unclear risks for allocation concealment and blinding (participants and/or investigators) 3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to the small number of participants/events (optimal Information size criterion not met) 4 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Some studies had unclear risk for sequence generation, all studies had unclear risks for allocation concealment and some of them were not blinded (participants and/or investigators) 5 Cardiovascular death was reported by as a single study with zero events in both groups; studies were not designed to measure effects of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers or placebo/control on cardiovascular death in HD 6 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Some studies had unclear risks for allocation concealment and were not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

Summary of findings 2. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives in people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis.

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives in people with CKD requiring dialysis | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD requiring dialysis

Setting: France, Turkey, Russia Intervention: dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (amlodipine or nifedipine) Comparison: other antihypertensives (all studies reported ACEi including, enalapril, perindopril or ramipril) | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Other antihypertensives | Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | ||||

| Predialysis systolic blood pressure mean follow‐up 10.5 months | The mean predialysis systolic blood pressure level in the other antihypertensive group ranged from 129 to 150 mmHg The mean predialysis systolic blood pressure level in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group was 2.44 mmHg higher (3.74 lower to 8.62 mmHg higher) |

‐ | 180 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,2 | |

| Predialysis diastolic blood pressure mean follow‐up 10.5 months | The mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure level in the other antihypertensive group ranged from 80 to 88.3 mmHg The mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure level in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group was 1.49 mmHg higher (2.23 lower to 5.21 mmHg higher) |

‐ | 180 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,2 | |

|

Cardiovascular death mean follow‐up 12 months |

No events 3 | No events | Not estimable | 164 (3) | ‐ |

|

Intradialytic hypotension follow‐up 12 months |

No events 4 | 1/47** | RR 2.88 (0.12 to 68.79) |

92 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 5,6 |

| Other side effects | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: Chronic kidney disease; HD: Haemodialysis; ACEi: Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. **Event rate derived from the raw data. A "per thousand" rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the control group. | |||||

1 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. Some studies had unclear risk for sequence generation, all studies had unclear risks for allocation concealment and the majority of them were not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to the small number of participants/events (optimal information size criterion not met)

3 Cardiovascular death was reported by as a single study with zero events in both groups; studies were not designed to measure cardiovascular death 4 Occurrence of intradialytic hypotension was reported by as a single study; studies were not designed to measure the occurrence of intradialytic hypotension in HD

5 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. The study had unclear risks for allocation concealment and was not blinded (participants and/or investigators)

6 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to imprecision

Summary of findings 3. Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis.

| Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in people with CKD requiring dialysis | |||||

|

Patient or population: people with CKD requiring dialysis Setting: Italy Intervention: dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (amlodipine) Comparison: non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil) | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | ||||

|

Predialysis systolic blood pressure follow‐up 2.8 months |

The mean predialysis systolic blood pressure level in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group was 4 mmHg lower (11.99 lower to 3.99 mmHg higher) than non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers 1 | ‐ | 40 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2,3 | |

|

Predialysis diastolic blood pressure follow‐up 2.8 months |

The mean predialysis diastolic blood pressure level in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group was 3.00 mmHg lower (7.06 lower to 1.06 mmHg higher) than non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers 1 | ‐ | 40 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2,3 | |

|

Cardiovascular death follow‐up 2.8 months |

No events 1,3,4 | No events | Not estimable | 40 (1) | ‐ |

| Intradialytic hypotension | Not reported | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

|

Other side effects1,5 follow‐up 2.8 months |

3/19 1 | No events** |

RR 0.13 (0.01 to 2.36) |

40 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 2,6 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CKD: Chronic kidney disease; HD: Haemodialysis; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio **Event rate derived from the raw data. A "per thousand" rate is non‐informative in view of the scarcity of evidence and zero events in the dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker group | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1 Studies not designed to measure this outcome 2 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to study limitations. The study had unclear risks for allocation concealment and was not blinded (participants and/or investigators) 3 Evidence certainty was downgraded by one level due to the small number of participants/events (optimal information size criterion not met)

4 Cardiovascular death was reported by as a single study with zero events in both groups 5 Other side effects included headache reported in non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group, while no events were reported in dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers group

6 Evidence certainty was downgraded by two levels due to imprecision

Calcium channel blockers versus placebo/control/no treatment

Five studies (Kozlova 2006; London 1990; LONDON 2019; Marchais 1991; Tepel 2008), randomising 451 adults undergoing haemodialysis, compared dihydropyridine CCBs to placebo or no treatment. The certainty of the evidence was low for all outcomes (Table 1).

Dihydropyridine CCBs may decrease predialysis systolic blood pressure level compared to placebo (Analysis 1.1 (1 study, 39 participants): MD ‐27.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐43.33 to ‐10.67; low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure level (Analysis 1.2 (2 studies, 76 participants): MD ‐13.56 mmHg, 95% CI ‐19.65 to ‐7.48; I2 = 0%; low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or no treatment.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker versus placebo/control/usual treatment, Outcome 1: Predialysis systolic blood pressure

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker versus placebo/control/usual treatment, Outcome 2: Predialysis diastolic blood pressure

The effect of dihydropyridine CCBs compared to placebo or no treatment on cardiovascular death was not estimable, since no events were reported in any of the studies (Analysis 1.3: 3 studies, 124 participants).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker versus placebo/control/usual treatment, Outcome 3: Cardiovascular death

Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to intradialytic hypotension (Analysis 1.4: 2 studies, 287 participants): RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.15; I2 = 0%;low certainty evidence) compared to placebo or no treatment.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker versus placebo/control/usual treatment, Outcome 4: Intradialytic hypotension

Other side effects and costs were not reported by any of the included studies.

No studies compared non‐dihydropyridine CCBs to placebo or control.

Calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives

Eight studies (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; London 1994; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002; Yilmaz 2010a) randomising 1037 adults treated with haemodialysis compared dihydropyridine CCBs to other antihypertensives. Five studies (Albitar 1997; Das 2003; HEART 2003; Kozlova 2006; Nakao 1999) were abstract‐only publications. Four studies (Das 2003; HEART 2003; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002), while meeting our inclusion criteria, had insufficient information and were not included in the meta‐analyses. The certainty of the evidence was low to very low (Table 2).

Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic (Analysis 2.1 (4 studies, 180 participants): MD 2.44 mmHg, 95% CI ‐3.74 to 8.62; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure (Analysis 2.2 (4 studies, 180 participants): MD 1.49 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.23 to 5.21; I2 = 0%, low certainty evidence) compared to other antihypertensives.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives, Outcome 1: Predialysis systolic blood pressure

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives, Outcome 2: Predialysis diastolic blood pressure

The effect of dihydropyridine CCBs compared to other antihypertensives on cardiovascular death was not estimable, since no events were reported in any of the studies (Analysis 2.3: 3 studies, 164 participants).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives, Outcome 3: Cardiovascular death

Yilmaz 2010a reported one case of intradialytic hypotension in the dihydropyridine CCB group (Analysis 2.4 (1 study, 92 participants): RR 2.88, 95% CI 0.12 to 68.79; very low certainty evidence).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives, Outcome 4: Intradialytic hypotension

Other side effects and costs were not reported by any of the included studies.

No studies compared non‐dihydropyridine CCBs to other antihypertensives.

Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers

Timio 1997 compared dihydropyridine CCB to non‐dihydropyridine CCB in 40 haemodialysis patients. The certainty of the evidence was low to very low (Table 3).

Timio 1997 reported may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic (Analysis 3.1 (1 study, 40 participants): MD ‐4.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐11.99 to 3.99; low certainty evidence) and diastolic blood pressure level (Analysis 3.2 (1 study, 40 participants): MD ‐3.00 mmHg, 95% CI ‐7.06 to 1.06; low certainty evidence) between dihydropyridine and non‐dihydropyridine CCB.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, Outcome 1: Predialysis systolic blood pressure

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, Outcome 2: Predialysis diastolic blood pressure

The effect of dihydropyridine CCB compared to non‐dihydropyridine CCB on cardiovascular death was not estimable, since no events were reported in either group (Analysis 3.3: 1 study, 40 participants).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, Outcome 3: Cardiovascular death

There was no evidence of a difference in other side effects (Analysis 3.4 (1 study, 40 participants): RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.36; very low certainty evidence) between dihydropyridine CCB and non‐dihydropyridine CCB. Other side effects included headache.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, Outcome 4: Other side effects

Timio 1997 did not report intradialytic hypotension or costs.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found 13 studies that met our inclusion criteria (1459 randomised adults); five of these were available only as abstracts. Four of these studies (Das 2003; HEART 2003; Nakao 1999; Shibasaki 2002), while meeting our inclusion criteria, had insufficient information and were not included in the meta‐analyses. All studies were performed in haemodialysis patients.

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were at low risk of bias in eight and one studies, respectively. Two studies reported low risk methods for blinding of participants and investigators, and outcome assessment was blinded in 10 studies. Three studies were at low risk of attrition bias, eight studies were at low risk of selective reporting bias, and five studies were at low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Dihydropyridine CCBs may decrease predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure when compared to placebo or no treatment, may make little or no difference to occurrence of intradialytic hypotension, whilst the effects on cardiovascular death was uncertain.

Eight studies compared dihydropyridine CCBs with other antihypertensives. Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure, while the effects on cardiovascular death and occurrence of intradialytic hypotension compared to other antihypertensives were uncertain.

Dihydropyridine CCBs may make little or no difference to predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure, while the effects on cardiovascular death and other side effects compared to non‐dihydropyridine CCBs were uncertain.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review searched for evidence supporting the use of CCBs in patients with CKD requiring dialysis. There were inadequate numbers of well conducted RCTs to answer our question conclusively.

Overall, data for carrying out the comparison between dihydropyridine CCBs and other antihypertensives came from four studies with 180 adult patients on maintenance haemodialysis (Albitar 1997; Kozlova 2006; London 1994; Yilmaz 2010a). Side effects were rarely reported (Table 4) and no studies addressed total healthcare cost. Studies done in children and in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis were not found after an extensive literature search.

1. Table of studies reporting adverse events.

| Study ID | Intervention | Control | Adverse events in the intervention group | Adverse events in the control group |

| London 1990 | Nitrendipine | Placebo | Not reported; no deaths were reported; no postdialysis hypotension was reported | Among 20 participants, the following adverse events were reported: dropped out due to DBP persistently > 114 mmHg (1). No death was reported. No postdialysis hypotension was reported |

| London 1994 | Nitrendipine | Perindopril | Among 14 participants, the following adverse events were reported: withdrawn due to DBP > 95 mmHg (4). No deaths were reported. No serious adverse event was reported | Among 16 participants, the following adverse events were reported: withdrawn due to DBP > 95 mmHg (2). No deaths were reported. No serious adverse events were reported |

| LONDON 2019 | Cilnidipine | Control | Among 25 participants, the following adverse events were reported: cardiogenic shock (due to acute coronary syndrome) (1), needed to decrease the dry weight more that 1% due to remarkable volume overload (3). No deaths were reported | Among 11 participants, the following adverse events were reported: colon cancer (1), hypotension (1), hypertension (1), needed to decrease the dry weight more that 1% due to remarkable volume overload (1). No deaths were reported |

| Marchais 1991 | Nifedipine | Placebo | Not reported; no deaths were reported | Among 20 participants, the following adverse events were reported: dropped out due to DBP persistently > 114 mmHg (1). No deaths were reported |

| Shibasaki 2002 | Amlodipine | Losartan or enalapril | Overall, of 61 participants there were: acute MI (3), myocarditis (2), death from pulmonary bleeding (1). However, no data were reported per group | Overall, of 61 participants there were: acute MI (3), myocarditis (2), death from pulmonary bleeding (1). However, no data were reported per group |

| Tepel 2008 | Amlodipine | Placebo | Among 123 participants, the following adverse events were reported: 15 deaths. Overall, 26 sudden deaths, 7 infections, 4 cancers were recorded but data were not reported per group. The flow chart showed that the drug was discontinued because of adverse events in 8 participants. 18 participants reported a cardiovascular event, including MI, need for coronary angioplasty or coronary bypass surgery, Ischaemic stroke, and peripheral vascular disease with the need for amputation or angioplasty |

Among 128 participants, the following adverse events were reported: 22 deaths. Overall, 26 sudden deaths, 7 infections, 4 cancers were recorded but data were not reported per group. The flow chart showed that the drug was discontinued because of adverse events in 12 participants; 33 participants reported a cardiovascular event, including MI, need for coronary angioplasty or coronary bypass surgery, Ischaemic stroke, and peripheral vascular disease with the need for amputation or angioplasty |

| Timio 1997 | Amlodipine | Verapamil | Among 21 participants, the following adverse events were reported: lower limb oedema (2), cough (2), cutaneous rash (1). No deaths were reported | Among 19 participants, the following adverse events were reported: lower limb oedema (7), headache (3). No deaths were reported |

| Yilmaz 2010a | Amlodipine | Ramipril | Among 47 participants, the following adverse events were reported: death (1), hypotension (1), drug intolerance (2) | Among 45 participants, the following adverse events were reported: 1 cough (1), hyperkalaemia (1) lead to the discontinuation from the study |

DBP ‐ diastolic blood pressure; MI ‐ myocardial infarction

No studies compared the effect of different dihydropyridine CCBs, different non‐dihydropyridine CCBs, or different doses of the same drug. No studies compared non‐dihydropyridines CCBs to other antihypertensives, placebo or control.

The majority of studies included in the meta‐analyses were performed in Europe; France (Albitar 1997; London 1990; London 1994; Marchais 1991), Germany (Tepel 2008), Italy (Timio 1997), Russia (Kozlova 2006), and Turkey (Yilmaz 2010a). LONDON 2019 was performed in Japan. This clearly affects the external validity of these findings, as these findings cannot be applied wholesome since clinical practice differs based on region.

The standardisation of outcomes reporting in future studies might enhance better evidence in dialysis setting. The Standardised Outcomes in Nephrology (SONG) initiative suggest that fatigue, cardiovascular disease, vascular access, and death (SONG‐HD) are the core outcomes set to report in all studies in haemodialysis setting, while infection, cardiovascular disease, death, technique survival and life participation are the compulsory outcomes to assess in studies on peritoneal dialysis (SONG‐PD).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was assessed according to the recommendations of the GRADE Working Group (Higgins 2011). Overall, the quality of evidence was generally either low or very low.

Twelve studies did not report allocation concealment and most studies reported inadequate blinding of investigators and participants, attrition, and other sources of bias, reducing the certainty of treatment benefits and harms. Only Tepel 2008 was considered at low risk of bias for all domains. As many outcomes, such as predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure and intradialytic hypotension, were measured using objective measures, 10 studies were at low risk of bias for outcome assessment. Heterogeneity was low across the studies included in the meta‐analysis.

Potential biases in the review process

Although we applied standard Cochrane methodology, residual bias in the review process was inevitably present. It is possible that relevant but unpublished data (those studies with neutral or negative effects) may have been missed. Analysis for evidence of such publication bias was not possible due to the small number of included studies.

Four studies did not report key outcomes in a format available for meta‐analysis. The included studies did not report total healthcare costs and no events were reported for cardiovascular death.

Only Timio 1997 investigated the effect of dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine CCBs. Furthermore, we found no studies that involved children or people undergoing peritoneal dialysis; and 12 studies were conducted in Europe and this may limit the generalisability of our findings.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We found one systematic review and meta‐analysis that investigated the effects of CCBs compared to ACEi or ARB in people with CKD stages 3‐5 including dialysis (Lin 2017). Our Cochrane review is consistent with the findings showed in that review, reporting no significant differences in change in blood pressure and death between the two groups. However, differences between Lin 2017 and our updated review were related to the inclusion of patients in CKD stages 3 to 5: although the author included 21 studies, only four studies were performed in ESKD. In addition, Lin 2017 excluded studies that compared dihydropyridine CCBs to placebo, no treatment or non‐dihydropyridine CCBs.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Dihydropyridine CCBs had uncertain effects on predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure, cardiovascular death, and occurrence of intradialytic hypotension compared to other antihypertensives. Data were provided by only a few studies with limited number of participants who experienced few events.

Dihydropyridine CCBs may reduce predialysis systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels compared to placebo or no treatment, although there was low certainty evidence; further investigation with adequately powered RCTs are needed.

Scant evidence were available to detect differences between dihydropyridine CCBs and non‐dihydropyridine CCBs and no data were available to compare different doses or the efficacy of different medications from the same drug class. Other side effects were rarely reported and no studies addressed costs. No data for treatment effects in children and in peritoneal dialysis were identified.

Implications for research.

Future RCTs with adequate sample size and longer follow‐up are required to assess the benefits and harms of dihydropyridine and non‐dihydropyridine CCBs compared to other antihypertensives, placebo or control in patients with CKD requiring dialysis. Furthermore, research in children and in patients treated with peritoneal dialysis are needed. We recommend these adequately powered prospective RCTS be undertaken. Key outcomes relevant for patients (including death and cardiovascular disease), changes in blood pressure, health care costs and side effects should be reported to assist clinical decision‐making.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2014 Review first published: Issue 10, 2020

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by the editorial team of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. We would also like to thank the referees for their feedback and advice during the preparation of this review.

George Mugendi was supported by a fellowship offered by Cochrane South Africa, South African Medical Research Council, funded by the Effective Health Care Research Consortium (http://www.evidence4health.org/). This Consortium is funded by UK aid from the UK Government for the benefit of developing countries (Grant: 5242). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect UK government policy.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker versus placebo/control/usual treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Predialysis systolic blood pressure | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.2 Predialysis diastolic blood pressure | 2 | 76 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐13.56 [‐19.65, ‐7.48] |

| 1.3 Cardiovascular death | 3 | 124 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 1.4 Intradialytic hypotension | 2 | 287 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.25, 1.15] |

Comparison 2. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers versus other antihypertensives.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Predialysis systolic blood pressure | 4 | 180 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.44 [‐3.74, 8.62] |

| 2.2 Predialysis diastolic blood pressure | 4 | 180 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [‐2.23, 5.21] |

| 2.3 Cardiovascular death | 3 | 164 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Not estimable |

| 2.4 Intradialytic hypotension | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Comparison 3. Dihydropyridine versus non‐dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Predialysis systolic blood pressure | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.2 Predialysis diastolic blood pressure | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.3 Cardiovascular death | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.4 Other side effects | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Albitar 1997.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group (ACEi)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised; method of randomisation was not reported. It was not possible to assess if differences between intervention groups could suggest a problem with the randomisation process |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not reported. However due to the difference between the intervention group and control group, it was possible that participants and/or investigators were aware of the treatment assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Objective outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | QUOTE: "All patients completed the study period without any intercurrent events" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No full‐text publication identified to assess the possible selective reporting |

| Other | High risk | Abstract‐only publication |

Das 2003.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group (ARB)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not reported. However due to the difference between the intervention group and control group, it was possible that participants and/or investigators were aware of the treatment assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Objective outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No full‐text publication identified to assess the possible selective reporting |

| Other | High risk | Abstract‐only publication |

HEART 2003.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group (ACEi)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised method of randomisation was not reported. It was not possible to assess if differences between intervention groups could suggest a problem with the randomisation process |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not reported. However due to the difference between the intervention group and control group, it was possible that participants and/or investigators were aware of the treatment assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | There was no information if an external panel adjudicated outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No full‐text publication identified to assess the possible selective reporting |

| Other | High risk | Abstract‐only publications |

Kozlova 2006.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group 1 (dihydropyridine CCB)

Treatment group 2 (dual therapy; ACEi + dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group 1 (ACEi)

Control group 2

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Study was described as randomised; method of randomisation was not reported. It was not possible to assess if differences between intervention groups could suggest a problem with the randomisation process |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not reported. However due to the difference between the intervention group and control group, it was possible that participants and/or investigators were aware of the treatment assignment |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Objective outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Abstract states 71 patients included, however only 69 accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No full‐text publication identified to assess the possible selective reporting. Not all data related to the control group were reported |

| Other | High risk | Abstract‐only publication |

London 1990.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | QUOTE: "Patients who did not respond were divided into two groups of 20, according to a randomisation list and with a balance every two patients." Study was described as randomised, method of randomisation was not reported. However, it was unlikely that differences between intervention groups could suggest a problem with the randomisation process |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | "Double blind". However, insufficient information to permit judgement |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Objective outcomes were assessed |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | QUOTE: "At the 24th week, due to the lack of a control group, the results of the group of patients taking nitrendipine are only descriptive." QUOTE: "One patient of the group taking placebo dropped out of the study after 4 weeks for DBP persistently higher than 114 mm Hg. Therefore, the analysis included only the remaining 19 patients." |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes prespecified were reported |

| Other | High risk | Commercial funding: Bayer Pharma |

London 1994.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

|

|

| Participants |

|

|

| Interventions | Treatment group (dihydropyridine CCB)

Control group (ACEi)

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |