Abstract

Background

Dementia is a progressive syndrome characterised by deterioration in memory, thinking and behaviour, and by impaired ability to perform daily activities. Two classes of drug ‐ cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine) and memantine ‐ are widely licensed for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease, and rivastigmine is also licensed for Parkinson's disease dementia. These drugs are prescribed to alleviate symptoms and delay disease progression in these and sometimes in other forms of dementia. There are uncertainties about the benefits and adverse effects of these drugs in the long term and in severe dementia, about effects of withdrawal, and about the most appropriate time to discontinue treatment.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of withdrawal or continuation of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine, or both, in people with dementia on: cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional outcomes, rates of institutionalisation, adverse events, dropout from trials, mortality, quality of life and carer‐related outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialised Register up to 17 October 2020 using terms appropriate for the retrieval of studies of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine. The Specialised Register contains records of clinical trials identified from monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases, numerous trial registries and grey literature sources.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised, controlled clinical trials (RCTs) which compared withdrawal of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine, or both, with continuation of the same drug or drugs.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed citations and full‐text articles for inclusion, extracted data from included trials and assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Where trials were sufficiently similar, we pooled data for outcomes in the short term (up to 2 months after randomisation), medium term (3‐11 months) and long term (12 months or more). We assessed the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome using GRADE methods.

Main results

We included six trials investigating cholinesterase inhibitor withdrawal, and one trial investigating withdrawal of either donepezil or memantine. No trials assessed withdrawal of memantine only. Drugs were withdrawn abruptly in five trials and stepwise in two trials. All participants had dementia due to Alzheimer's disease, with severities ranging from mild to very severe, and were taking cholinesterase inhibitors without known adverse effects at baseline. The included trials randomised 759 participants to treatment groups relevant to this review. Study duration ranged from 6 weeks to 12 months. There were too few included studies to allow planned subgroup analyses. We considered some studies to be at unclear or high risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition or reporting bias.

Compared to continuing cholinesterase inhibitors, discontinuing treatment may be associated with worse cognitive function in the short term (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.64 to ‐0.21; 4 studies; low certainty), but the effect in the medium term is very uncertain (SMD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.87 to 0.07; 3 studies; very low certainty). In a sensitivity analysis omitting data from a study which only included participants who had shown a relatively poor prior response to donepezil, inconsistency was reduced and we found that cognitive function may be worse in the discontinuation group in the medium term (SMD ‐0.62; 95% CI ‐0.94 to ‐0.31). Data from one longer‐term study suggest that discontinuing a cholinesterase inhibitor is probably associated with worse cognitive function at 12 months (mean difference (MD) ‐2.09 Standardised Mini‐Mental State Examination (SMMSE) points, 95% CI ‐3.43 to ‐0.75; moderate certainty).

Discontinuation may make little or no difference to functional status in the short term (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.54 to 0.04; 2 studies; low certainty), and its effect in the medium term is uncertain (SMD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐0.74 to ‐0.01; 2 studies; very low certainty). After 12 months, discontinuing a cholinesterase inhibitor probably results in greater functional impairment than continuing treatment (MD ‐3.38 Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS) points, 95% CI ‐6.67 to ‐0.10; one study; moderate certainty). Discontinuation may be associated with a worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms over the short term and medium term, although we cannot exclude a minimal effect (SMD ‐ 0.48, 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.13; 2 studies; low certainty; and SMD ‐0.27, 95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.08; 3 studies; low certainty, respectively). Data from one study suggest that discontinuing a cholinesterase inhibitor may result in little to no change in neuropsychiatric status at 12 months (MD ‐0.87 Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) points; 95% CI ‐8.42 to 6.68; moderate certainty).

We found no clear evidence of an effect of discontinuation on dropout due to lack of medication efficacy or deterioration in overall medical condition (odds ratio (OR) 1.53, 95% CI 0.84 to 2.76; 4 studies; low certainty), on number of adverse events (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.27; 4 studies; low certainty) or serious adverse events (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.39; 4 studies; low certainty), and on mortality (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.55; 5 studies; low certainty). Institutionalisation was reported in one trial, but it was not possible to extract data for the groups relevant to this review.

Authors' conclusions

This review suggests that discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitors may result in worse cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional status than continuing treatment, although this is supported by limited evidence, almost all of low or very low certainty. As all participants had dementia due to Alzheimer's disease, our findings are not transferable to other dementia types. We were unable to determine whether the effects of discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitors differed with baseline dementia severity. There is currently no evidence to guide decisions about discontinuing memantine. There is a need for further well‐designed RCTs, across a range of dementia severities and settings. We are aware of two ongoing registered trials. In making decisions about discontinuing these drugs, clinicians should exercise caution, considering the evidence from existing trials along with other factors important to patients and their carers.

Plain language summary

Stopping or continuing anti‐dementia drugs in patients with dementia

Background

Dementia is the term used to describe a group of illnesses, usually developing in late life, in which there is a deterioration in a person’s ability to think, remember, communicate and manage daily activities independently. It can be caused by several different brain diseases, but the most common form is dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. At the moment, there are no medical treatments which can prevent dementia or stop it from progressing, but there are two classes of drugs – the cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine) and memantine ‐ which are approved and widely prescribed to treat some of the symptoms. They are used mainly for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease but also sometimes for other types of dementia. Most of the trials studying the effects of these drugs have been quite short (typically six months) even though dementia usually lasts for years. The drugs can have unwanted side effects in some people. There is uncertainty about their long‐term effects and about how useful they are for severe dementia, with different countries making different recommendations. Therefore it can be difficult for doctors and patients to decide if and when these drugs should be stopped once they have been started.

What was the aim of this review?

In this review, we aimed to summarise the best evidence about whether stopping cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine was beneficial or harmful to people with dementia who had been taking them for at least two months.

What we did

We searched up to October 2020 for trials which had: recruited people with dementia who were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both; divided them randomly into a group of patients who continued treatment and a group of patients who stopped treatment; and compared what happened in the two groups.

What we found

We found seven trials (759 participants) to include in the review. All of the participants had dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease, but in some trials, the disease was mild to moderate and in others, it was moderate to severe or very severe. Six trials investigated the effects of stopping a cholinesterase inhibitor and one trial investigated stopping either a cholinesterase inhibitor (specifically, donepezil) or memantine. We decided not to pool its results with the other six trials. Effects were measured over different periods of time in different trials. We looked separately at effects in the first 2 months (short term), between 3 and 11 months (medium term), and after a year or more (long term).

When we looked at the effect on thinking skills and memory, we found that, compared to stopping treatment, continuing treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor may be beneficial in the short term and medium term and is probably beneficial in the long term. For ability to carry out daily activities, there may be little or no effect in the short term, and the effect in the medium term was very uncertain, but there is probably a benefit to continuing treatment over the longer term. For mood and behavioural problems, continuing treatment may have benefits in the short term and medium term, but not in the long term. We found no clear evidence about the effects of stopping these drugs on patients’ physical health or risk of dying. There was very little evidence about effects on quality of life or on the likelihood of moving to a care home to live. There was not enough evidence for us to see whether results differed with the severity of dementia.

Our certainty in the results varied from moderate to very low, mainly because of small numbers of trials and participants, some problems with the way the trials were conducted, and imprecise statistical results.

Our conclusions

Although there was uncertainty about the results, most of the evidence pointed to benefits of continuing treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors. There was no evidence about types of dementia other than Alzheimer’s disease, and we were unable to draw specific conclusions about continuing or stopping treatment at different stages of the illness. We found no trials that just investigated stopping memantine.

These results may help patients and their doctors to make decisions about whether or not to continue treatment, although other factors, such as side effects in an individual patient and the patient’s preferences, are also important.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor compared to continued cholinesterase inhibitor in patients with dementia (short term, up to 2 months).

| Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor compared to continued cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (short term, up to 2 months) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with dementia Settings: all healthcare settings Intervention: withdrawal of Cholinesterase Inhibitor Comparison: continuation of Cholinesterase Inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Continued cholinesterase inhibitor | Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor | |||||

|

Cognitive function (change from baseline, short term) Standardised mean difference (ADAS‐Cog/11, SMMSE, MMSE) |

‐ | SMD 0.42 lower (0.64 lower to 0.21 lower; P < 0.001). Lower SMD means a greater decline in cognitive function from baseline |

‐ | 344 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Discontinuing a ChEI may reduce cognitive function compared to continuing treatment |

|

Functional status (change from baseline, short term) Standardised mean difference (BADLS, ADCS‐ADL‐sev) |

‐ | SMD 0.25 lower (0.54 to 0.04 higher; P = 0.09). Lower SMD means a greater decline in function from baseline |

‐ | 183 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc,d |

Discontinuing a ChEI may result in increased functional impairment compared to continuing ChEI treatment. However, the 95% confidence interval indicates that discontinuation might make little or no difference to functional status. |

|

Neuropsychiatric status (change from baseline, short term) Standardised mean difference (NPI, NPI‐NH) |

‐ | SMD 0.48 lower (0.82 lower to 0.13 lower; P = 0.007). Lower SMD means a greater deterioration in neuropsychiatric status from baseline |

‐ | 136 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowe,f | Discontinuation may result in increased neuropsychiatric symptoms compared to continuing ChEI treatment |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ADAS‐Cog/11: Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale‐Cognitive subscale/11; ADCS‐ADL‐sev: Alzheimer's Disease Co‐operative Study ‐ Activities of Daily Living Inventory, modified for severe dementia; BADLS: Bristol Activities of Daily Living scale; ChEI: Cholinesterase inhibitor; CI: Confidence interval; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPI‐NH: Neuropsychiatric Inventory ‐ Nursing Home version; OR: Odds Ratio; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference; SMMSE: Standardised Mini‐Mental State Examination | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risk of selection bias associated with random sequence generation, detection bias in blinding of outcome assessment, reporting bias in selective reporting, and other bias. One study had high risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) and unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment) and reporting bias, and one study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), detection bias (blinding of participants and personnel, and blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) and other bias. bSerious imprecision: there were 344 participants in the three studies. cSerious risk of bias: one study had high risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) and unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment) and reporting bias (selective reporting). dSerious imprecision: there were 183 participants in the two studies, and a wide confidence interval including both no effect and a large effect. eSerious risk of bias: one study had high risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), and unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment) and reporting bias (selective reporting). One study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel, and blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data) and other bias. fSerious imprecision: there were 136 participants in the two studies.

Summary of findings 2. Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor compared to continued cholinesterase inhibitor in patients with dementia (medium‐term, 3‐11 months).

| Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor compared with continued cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (medium term, 3 to 11 months) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients withdementia Settings: all healthcare settings Intervention: withdrawal of cholinesterase Inhibitor Comparison: continuation of cholinesterase Inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Continued cholinesterase inhibitor | Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor | |||||

|

Cognitive function (change from baseline, medium term) Standardised mean difference (SMMSE, MMSE) |

‐ | SMD 0.40 lower (0.87 lower to 0.09 higher; P = 0.10). Lower SMD means a greater decline in cognitive function from baseline |

‐ | 411 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ verylowa,b,c | It is uncertain whether discontinuing a ChEI reduces cognitive function compared to continuing treatment. The 95% confidence interval indicates that discontinuation might make little or no difference to cognitive function, and the certainty of the evidence is very low. On removing data from one study which only included participants who had shown a poor response to donepezil, inconsistency was reduced and the SMD was ‐0.62 (95% CI ‐0.94 to ‐0.31); P < 0.001. |

|

Functional status (change from baseline, medium term) Standardised mean difference (BADLS, DAD) |

‐ | SMD 0.38 lower (0.74 lower to 0.01 lower; P = 0.04). Lower SMD means a greater decline in function from baseline |

‐ | 314 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ verylowd,e,f | It is uncertain whether discontinuing a ChEI may result in increased functional impairment compared to continuing ChEI treatment, because the certainty of the evidence is very low. |

|

Neuropsychiatric status (change from baseline, medium term) Standardised mean difference (10 and 12‐item NPI) |

‐ | SMD 0.27 lower (0.47 lower to 0.08 lower; P = 0.007). Lower SMD means a greater deterioration in neuropsychiatric status from baseline |

‐ | 410 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowc,g | Discontinuation may result in increased neuropsychiatric symptoms compared to continuing ChEI treatment. |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BADLS: Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale; ChEI: Cholinesterase inhibitor; CI: Confidence interval; DAD: Disability Assessment for Dementia Scale; MD: Mean Difference; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; OR: Odds Ratio; SMD: Standardised Mean Difference; SMMSE: Standardised Mini‐Mental State Examination | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aSerious inconsistency: the confidence intervals did not all overlap, P = 0.005 and I2 = 81%. bSerious imprecision: wide confidence interval including both no effect and a large effect cSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias, and one study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias, and high risk of reporting bias. dSerious imprecision: there were 314 participants in the two studies, and the upper confidence interval was close to the null effect value. eSerious inconsistency: I2 = 60% fSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias, and high risk of reporting bias. gSerious imprecision: the CI includes essentially no effect, and an effect of moderate size, which may be clinically important.

Summary of findings 3. Discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitor compared with continuing cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (long‐term, 12 months or longer).

| Discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitor compared with continuing cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (long term, 12 months or longer) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with dementia Settings: all healthcare settings Intervention: withdrawal of cholinesterase inhibitor Comparison: continuation of cholinesterase inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Continued cholinesterase inhibitor | Discontinued cholinesterase inhibitor | |||||

|

Cognitive function (change from baseline, long term) SMMSE |

‐ | MD 2.09 lower (3.43 lower to 0.75 lower; P = 0.002) Lower MD means a greater decline in cognitive function from baseline |

‐ | 108 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Discontinuing a ChEI probably reduces cognitive function compared to continuing treatment |

|

Functional status (change from baseline, long term) BADLS |

‐ | MD 3.38 lower (6.67 lower to 0.10 lower; P = 0.04) Lower MD means a greater decline in function from baseline |

‐ | 109 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | Discontinuing a ChEI probably results in increased functional impairment compared to continuing ChEI treatment |

|

Neuropsychiatric status (change in NPI from baseline, long term) NPI |

‐ | MD 0.87 lower (8.42 lower to 6.68 higher; P = 0.82) Lower MD means a greater deterioration in neuropsychiatric status from baseline |

‐ | 108 (1) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Discontinuing a ChEI may result in little to no change in neuropsychiatric status compared to continuing treatment |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). BADLS: Bristol Activities of Daily Living scale; ChEI: Cholinesterase inhibitor; CI: Confidence interval; MD: Mean difference; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; OR: Odds Ratio; SMMSE: Standardised Mini‐Mental State Examination | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aSerious imprecision: there were 108 participants in one study, and a wide confidence interval. bSerious imprecision: there were 109 participants in one study, and a wide confidence interval.

Summary of findings 4. Discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitor compared to continued cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (all trial durations) Summary of findings.

| Discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitor compared with continuing cholinesterase inhibitor for patients with dementia (all trial durations) | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with dementia Settings: all healthcare settings Intervention: withdrawal of cholinesterase Inhibitor Comparison: continuation of cholinesterase Inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Continued cholinesterase inhibitor | Continued cholinesterase inhibitor | |||||

| Dropout due to lack of efficacy of trial medication or deterioration in overall medical condition | 9.7% | 14.1% (95% CI = 8.3% to 22.8%) 6.0% more (95% CI = 1.7% less to 23.3% more) |

OR 1.53 (0.84 to 2.76); P = 0.16 | 583 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Discontinuing a ChEI may make little or no difference to the number of dropouts due to lack of efficacy of trial medication or deterioration in overall medical condition in those who discontinued ChEIs vs. those who continued ChEIs |

| Adverse events (any) | 38.7% | 34.9% (95% CI = 26.4% to 44.5%) 8.6% less (95% CI = 21.3% less to 20.5% more) |

OR 0.85 (0.57 to 1.27); P = 0.43 | 446 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | Discontinuing a ChEI may make little or no difference to the number of adverse events between those who discontinued ChEIs vs. those who continued ChEIs |

| Serious adverse events (SAEs) | 29.6% | 25.2% (95% CI = 16.2% to 36.9%) 7.8% less (95% CI = 18.5% less to 19.7% more) |

OR 0.80 (0.46 to 1.39); P = 0.43 | 390 (4) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e | Discontinuing a ChEI may make little or no difference to the number of adverse events between those who discontinued ChEIs vs. those who continued ChEIs |

| Deaths | 6.3% | 4.8% (95% CI = 2.4% to 9.5%) 1.7% less (95% CI = 4.1% less to 3.8% more) |

OR 0.75 (0.36 to 1.55);P = 0.43 | 598 (5) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,f | Discontinuing a ChEI may make little or no difference to the number of deaths between those who discontinued ChEIs vs. those who continued ChEIs |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ChEI: Cholinesterase inhibitor; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds Ratio; SAE: Serious Adverse Event | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risks of performance bias, detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and high risk of attrition bias. One study had unclear risk of bias in the following domains: selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and other bias, and one study had high risk of reporting bias and unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and other bias. bSerious imprecision: the CI includes no effect, and an effect which may be clinically important. cSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risks of performance bias, detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and high risk of attrition bias. One study had unclear risk of selection bias (random sequence generation), detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, one had unclear risk of selection and reporting bias and high risk of attrition bias, and one study had unclear risk of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias and high risk of reporting bias. dSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risks of performance bias, detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and high risk of attrition bias. One study had unclear risks of selection bias (random sequence generation), detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and one had unclear risk of selection and reporting bias and high risk of attrition bias. eSerious imprecision: there were 390 participants in the four studies, and the CI includes no effect, and an effect which may be clinically important. fSerious risk of bias: one study had unclear risk of performance bias, detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and high risk of attrition bias. One study had unclear risks of selection bias (random sequence generation), detection bias, reporting bias and other bias, and one had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment) and reporting bias, and high risk of attrition bias. One study had unclear risks of selection bias (allocation concealment), performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and other bias and high risk of reporting bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Dementia is a global public health problem which will continue to grow as the proportion of older people in the population increases. It has been estimated that 46.8 million people worldwide were living with dementia in 2015 and that this number will rise to 74.7 million in 2030, and to 131.5 million in 2050 (Alzheimer's Disease International 2016). Whilst it has been estimated that between 2% and 10% of all cases start before the age of 65 years, dementia predominantly affects older people (Alzheimer's Disease International 2009; Winblad 2016).

Dementia is defined as “a progressive and largely irreversible clinical syndrome that is characterised by a widespread impairment of mental function” (NICE 2006). It is characterised by a cluster of symptoms and signs including difficulties in memory, disturbances in language, psychosocial and psychiatric changes, and impairments in activities of daily living (Burns 2009; Wu 2016). The intellectual decline is usually progressive and spares the level of consciousness until the very late stages of the illness.

There are different subtypes of dementia associated with a large number of underlying brain pathologies (Alzheimer's Disease International 2009; Burns 2009). The most common subtypes in older patients are dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia (VaD), dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Parkinson's Disease Dementia (PDD). Alzheimer's disease is the most common subtype, accounting for between 50% and 75% of dementia cases. It is characterised by cortical amyloid “plaques” and neurofibrillary “tangles” which develop in the structure of the brain (Tomlinson 1982; Hardy 2002; Querferth 2010; Puri 2011; Scheltens 2016). Vascular dementia is the next most common subtype, accounting for 20% to 30% of all dementia cases. It is caused by a variety of cerebrovascular pathologies, either single infarcts in critical regions of the brain or more diffuse small vessel or multi‐infarct disease (Alzheimer's Disease International 2009; World Health Organization 2010; O'Brien 2015). Post‐mortem studies suggest that many people with dementia have mixed Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia pathology and that this ‘mixed dementia’ is under‐diagnosed (Alzheimer's Disease International 2009; Winblad 2016 ). Prevalence figures for DLB vary widely; it is thought to be responsible for anything up to 30% of dementia cases (Zaccai 2005; Vann Jones 2014) and is caused by cortical Lewy Bodies (alpha‐synuclein) in the brain (Kalra 1996; Jacques 2000; Alzheimer's Disease International 2009; Walker 2015). It has been suggested that DLB is also under‐diagnosed in clinical practice (Mok 2004; Toledo 2013). PDD is related pathologically to DLB and many investigators consider them to lie on a spectrum of Lewy Body disorders.

Description of the intervention

Currently, there are no drugs available which can modify the course of Alzheimer's disease or the Lewy Body dementias. However, an important advance has been the introduction of drugs to delay symptomatic progression and ‐ to some extent ‐ treat the symptoms (Qaseem 2008; Raina 2008; Lopez 2009). Five drugs have United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for managing Alzheimer's disease: four cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs; donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and tacrine) and memantine. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine are licensed in the United Kingdom (UK) and throughout Europe for the management of Alzheimer's disease (Rodda 2012), though they are no longer remunerated in France, due to concern that the small benefit they offer shifts clinicians' attention from other interventions (Livingston 2020). Rivastigmine is currently the only ChEI licensed in the UK and the USA for the treatment of mild to moderate PDD (Rolinski 2012). This represents a limited armoury of therapeutic agents available for pharmacological management of dementia.

In this review, we identified and appraised trials which included patients who were on stable treatment with a ChEI or memantine and were then randomised to withdrawal or continuation of the drug. Although the only regulatory approvals are of ChEIs and memantine for Alzheimer's disease, and rivastigmine for PDD, in clinical practice they are also prescribed for other dementias (Raina 2008). Therefore, we examined studies relating to withdrawal of ChEIs and memantine in people with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, mixed dementias, PDD and DLB.

ChEIs work by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase at cholinergic synapses, thereby raising synaptic levels of acetylcholine (a neurotransmitter critical to the neurons involved in cognition) (Hsiung 2008; Raina 2008). Donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine are the most widely used and have received regulatory approval for the treatment of people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease in all jurisdictions (Voisin 2009). There is also evidence to suggest that donepezil can improve the cognitive, functional and neuropsychiatric status of patients with more advanced Alzheimer's disease (Feldman 2001; Schmitt 2006; Winblad 2006a; Winblad 2006c; Black 2007; Herrmann 2007a; Winblad 2009) and it is approved by the FDA in the USA for this indication. Rivastigmine, administered transdermally in a patch formulation, may also benefit cognition, activities of daily living and global functioning in people with severe Alzheimer's disease and it has received FDA approval for use in such patients (Farlow 2013). However, numerous drug agencies have not approved use of ChEIs in patients at this stage of the disease(Voisin 2009). There is therefore controversy surrounding their use in people with severe disease (Parsons 2010), due in part to the lack of RCT data in people with more severe illness (Herrmann 2007b; Hong 2018).

Rivastigmine is licensed for the treatment of mild and moderate PDD in the UK and the USA and available evidence suggests that it has a positive impact on global assessment, cognitive function, behavioural disturbance and activities of daily living (Rolinski 2012). Although use of ChEIs in DLB is common practice among clinicians, the effect of these agents on patients with DLB has not been widely investigated and evidence for their use in this patient group is not clear (Rolinski 2012).

There is considerable debate over the benefits and risks of extended use of these agents. Trial durations of 3, 6 or 12 months are the most common for assessing efficacy of dementia medications (Winblad 2006a; Rodda 2009; Schneider 2012; Deardorff 2015; Winblad 2016), with a consequent lack of evidence for longer‐term treatment (Seltzer 2007; Schneider 2012; Winblad 2016). There has been a handful of placebo‐controlled trials of ChEIs for people with Alzheimer's disease which have followed participants for a year or more (Mohs 2001; Winblad 2001; Courtney 2004; Suh 2008; DOMINO AD Howard). Their interpretation is complicated by restricted inclusion criteria, high discontinuation rates, and questionable statistical analyses (Hogan 2014). A number of open‐label extension studies have also been conducted in order to evaluate the long‐term efficacy of ChEIs (Rogers 2000; Doody 2001; Geldmacher 2003a; Winblad 2003; Pirttila 2004; Raskind 2004; Farlow 2005; Small 2005; Winblad 2006b; Burns 2007; Feldman 2009; Rountree 2009; Kavanagh 2011; Wattmo 2011; Atri 2012; Rountree 2013; Farlow 2015). Analysis of the data from such studies has shown that cognitive measures of ChEI‐treated patients remain higher (often significantly) than those predicted for a hypothetical placebo group for periods of up to four or five years (Winblad 2004; Bullock 2005; Seltzer 2007). An observational study examining long‐term use of ChEIs, in which patients were monitored for six years from the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, has also demonstrated longer time to reaching functional end points and death (Zhu 2013). Another long‐term study over the course of 20 years reported that increased duration and persistence of treatment was associated with better performance on global, functional and cognitive outcome measures (Rountree 2009). Such studies provide useful data on long‐term effects of these agents in a more authentic setting than RCTs, but they are unable to provide evidence with the same level of certainty (Deardorff 2015). The impression of sustained benefit of these drugs must be interpreted in light of the various limitations and sources of bias inherent in the design of such studies (Schneider 2012). Further, there is evidence that the efficacy of donepezil, and to a lesser extent galantamine, decreases over time due to its ability to induce up‐regulation of acetylcholinesterase (Amici 2001; Davidsson 2001; Parnetti 2002; Darreh‐Shori 2006; Nordberg 2009), and that treatment with the rapidly‐reversible ChEIs (donepezil, galantamine and tacrine) is associated with a marked and significant up‐regulation of acetylcholinesterase in patients with Alzheimer's disease (Darreh‐Shori 2010). Hence, there is continuing uncertainty regarding the long‐term efficacy of ChEIs (Schneider 2012).

As well as questions about long‐term efficacy, concerns have been raised in the literature about adverse events associated with use of ChEIs. Population‐based studies have demonstrated increased rates of syncope, bradycardia, pacemaker insertion and hip fracture in older adults with dementia who are taking ChEIs (Gill 2009; Hernandez 2009; Park‐Wyllie 2009). A meta‐analysis of RCTs has reported an association between use of ChEIs and greater risk of syncope, but not of falls, fracture or accidental injury (Kim 2011). These studies in combination highlight the importance of careful monitoring due to the potential for these serious adverse events in this vulnerable patient population (Deardorff 2015). Discontinuing ChEIs in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease has been common practice in some places. However, if these drugs retain efficacy over the long term, then this may lead to worsening cognitive function and greater functional impairment. This risk must be balanced against the risk of side effects and the costs involved in continuing these agents (Herrmann 2013). Deciding when to discontinue a ChEI remains an area of uncertainty for clinicians (Parsons 2010; Herrmann 2013; Parsons 2014; Deardorff 2015; Hong 2018; Renn 2018).

Memantine is an agonist‐antagonist (partial agonist and uncompetitive antagonist) of the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor. It partially blocks the NMDA receptor and prevents excessive stimulation of the glutamate system, which influences memory and learning (Hsiung 2008; Raina 2008). It is licensed for the treatment of moderate and severe Alzheimer's disease in North America, Europe and Australia (Reisberg 2006), but is not licensed for treatment of mild Alzheimer's disease. Along with cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine was removed from state funding in France in 2018. There is uncertainty about the efficacy of memantine in end‐stage dementia (Herrmann 2008), and about the most appropriate time to discontinue treatment (Puangthong 2009). The long‐term efficacy of memantine also remains to be confirmed (Puangthong 2009), as the duration of most trials evaluating memantine efficacy has been only three to six months (Wilcock 2008; Förstl 2011; Herrmann 2011; Rainer 2011; Schulz 2011; Fox 2012; Grossberg 2013; Nakamura 2014; McShane 2019), although several follow‐up and open‐label extension studies have reported clinically relevant benefits for patients at one year and two years, respectively (Reisberg 2006; Sinforiani 2012). However, prolonged treatment with memantine may be associated with serious adverse effects in some patients: there have been case reports of loss of consciousness or seizure‐like episodes, or both (Savic 2013). A recent Cochrane Review of memantine for dementia concluded that there is a substantial volume of high certainty evidence for a small, beneficial and clinically detectable effect in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease at six months, and moderate certainty evidence of no benefit in mild Alzheimer's disease over six months, with increased possibility of discontinuation due to adverse events (McShane 2019). The review authors identified a need for a large trial of at least two to three years' duration in mild Alzheimer's disease to definitely rule out benefit of long‐term treatment in earlier dementia, and highlighted that a three‐year study in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease is required to determine whether there are any continuing effects beyond six months' treatment with memantine (McShane 2019).

These clinical questions surrounding long‐term treatment with ChEIs and memantine are further complicated by the challenge of detecting ongoing benefit of treatment which is not disease‐modifying for patients in whom dementia progresses. In addition, socioeconomic considerations must be taken into account. A study examining the cost‐effectiveness of continuing donepezil in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease already treated with the drug reported that continuation of donepezil treatment for a further 52 weeks was more cost‐effective than discontinuation, regardless of whether outcomes were measured in terms of improvements in cognitive impairment, functional impairment or health‐related quality of life, and whether costs were measured for the health and social care system or for society as a whole (Knapp 2017). The majority of economic analyses of ChEIs make projections for fairly long periods of time (four to five years), and support persistent use (Seltzer 2007). Studies examining longer durations of treatment with memantine are lacking. Such studies, together with transparent economic analyses, are required to determine the long‐term cost‐effectiveness of memantine (Puangthong 2009).

Finally, the increasing interest in deprescribing medications, where deprescribing is defined as a systematic process of identifying and discontinuing drugs where the potential harms outweigh the potential benefits of continued treatment (Scott 2015), focuses on older adults taking multiple medicines and particularly on individuals with dementia (Herrmann 2018). In many countries, initiatives are underway to deprescribe medications considered to be of questionable benefit and to guide deprescribing priorities where multiple medications may be considered for deprescribing. It is within this context that this review aims to address the effects of withdrawing ChEIs or memantine, or both, on clinical and humanistic outcomes for people with dementia and their carers.

How the intervention might work

Interventions to withdraw ChEIs or memantine, or both, in people with dementia may reduce adverse effects and improve quality of life for the patient and carer. However, they may also cause withdrawal symptoms or worsening of cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional outcomes, and may accelerate institutionalisation. Conversely, continuation of these drugs may prevent deterioration in the clinical outcomes just mentioned, but may increase mortality and adverse events and have a negative impact on the patient's quality of life.

Why it is important to do this review

Little direction is provided within treatment guidelines on how to determine the benefit of ChEIs or memantine in people with dementia, how long treatment should be continued and under what conditions to discontinue treatment. There has been ongoing debate regarding the benefit of continuing therapy, and it remains unclear whether patients who decline despite continuing treatment or those in more severe stages of the disease should have treatment withdrawn. Questions therefore remain unanswered regarding withdrawal or continuation of ChEIs or memantine, or both, for patients with dementia. A systematic review will help to identify the benefits and risks of withdrawal or continuation of these medications in this vulnerable population and may also identify important gaps in the evidence base.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of withdrawal or continuation of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine, or both, in people with dementia on: cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional outcomes, rates of institutionalisation, adverse events, dropout from trials, mortality, quality of life and carer‐related outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised, controlled clinical trials.

Types of participants

Participants had dementia of any severity, diagnosed using a recognised and validated tool or by clinical assessment, and were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, at baseline. Eligible dementia subtypes were Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, mixed dementia, DLB and PDD.

Alzheimer's disease: diagnosis of probable or possible Alzheimer's disease according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke / the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA) criteria or acceptable equivalent

Vascular dementia: diagnosis of probable or possible vascular dementia according to National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke / Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NIND‐AIREN) criteria or acceptable equivalent

PDD: diagnosis of probable or possible PDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) criteria (American Psychiatric Association 1994), or acceptable equivalent

DLB: diagnosis of probable or possible DLB according to international consensus criteria for DLB (McKeith 2006)

Patients could be resident in any setting (including acute hospitals, nursing and residential homes and the community).

Types of interventions

Control Intervention

Continuation of cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, beyond the time of randomisation.

Experimental interventions

Discontinuation of cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, after randomisation, with or without placebo substitution. Treatment may have been discontinued abruptly or by gradual tapering of the dose.

Types of outcome measures

We selected the following primary and secondary outcomes of interest.

Primary outcomes

Cognitive, neuropsychiatric and functional outcomes, measured with validated scales

Rates of institutionalisation

Adverse effects

Dropouts from the trial, including total number of dropouts and number of dropouts due to deterioration or lack of efficacy

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life of patients (measured with a validated scale)

Quality of life of caregivers (measured with a validated scale)

Mortality

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) ‐ the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group’s Specialised Register ‐ up to 17 October 2020. We used search terms appropriate for the identification of reports of trials using the cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and tacrine) and memantine.

ALOIS is maintained by the Information Specialists of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group and contains studies in the areas of dementia (prevention and treatment), mild cognitive impairment and cognitive improvement. The studies are identified from:

monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and LILACS;

monthly searches of a number of trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Register); the WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Library’s Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); and

six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources from ISI Web of Science Core Collection.

To view a list of all sources searched by ALOIS see 'About ALOIS' on the ALOIS website (alois.medsci.ox.ac.uk/about-alois). Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, CENTRAL and conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘Methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group. We performed additional searches in many of the sources listed above, to cover the timeframe from the last searches performed for ALOIS to ensure that the search for the review was as up‐to‐date and as comprehensive as possible. The search strategies used are described in Appendix 1. The most recent search was carried out in October 2020. No language restrictions were applied.

Searching other resources

We inspected the references of all identified studies for other studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Three review authors (CP, CH, WYL) independently screened titles and abstracts of citations identified by the searches, discarding obviously irrelevant articles. At this stage, we were overly inclusive: any article that suggested a relevant trial was retrieved in full‐text form for further assessment. Two review authors then independently assessed the full‐text articles against the predefined inclusion criteria. We resolved discrepancies by consensus.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (CP, CH, WYL) independently extracted data from the included trials and resolved discrepancies by consensus.

For continuous data, we extracted the mean change from baseline, the standard error or standard deviation of the mean change, and the number of patients in each treatment group at each time point. Where changes from baseline were not reported, we extracted the mean, standard deviation and the number of people in each treatment group at each time point. For ordinal variables, such as cognitive, neuropsychiatric, functional and quality of life scales, where there are large numbers of possible scores, we treated the measures as continuous. Where there were differences in the direction of the scales used to measure an outcome (e.g. the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale ‐ Cognitive Subscale (ADAS‐Cog/11) and the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) as measures of cognitive function, where a decrease in MMSE and an increase in ADAS‐Cog/11 indicate poorer function), we multiplied the mean values by ‐1 as appropriate to ensure that all the scales pointed in the same direction.

For dichotomous data, we extracted the number in each treatment group and the numbers experiencing the outcome of interest.

For each outcome measure, we sought to extract data on every patient randomised, irrespective of compliance, whether or not the person was subsequently deemed ineligible, or otherwise excluded from treatment or follow‐up. If these 'intention‐to‐treat' data were not available in the publications, then we extracted 'on‐treatment' data of those who completed the trial.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in each of the included trials using the following criteria of internal validity: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, adequate reporting and handling of missing outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other risks of bias. We followed the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, hereafter referred to as the Cochrane Handbook). Three reviewers (CP, CH, WYL) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. We followed GRADE recommendations to determine the certainty of the evidence (Guyatt 2008). This involved considering risk of bias together with inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias. Two reviewers (CP, WYL) completed this assessment.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes, the measure of treatment effect was the standardised mean difference (SMD, the absolute mean difference divided by the standard deviation) due to a range of outcome measures being employed by the included studies. For dichotomous outcomes, the measure of treatment effect was the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio. A 95% confidence interval was calculated for all effect estimates.

Unit of analysis issues

Individual patients were randomised in all included trials. No unit of analysis issues were encountered.

Dealing with missing data

We described any data which were missing from the published report of a trial.

Where participant‐level data were missing, then we sought intention‐to‐treat data and, if these were not reported, analysed available case data. We reported any statistical method used by the study authors (e.g. multiple imputation analysis, last observation carried forward) to deal with non‐missing‐at‐random data. We excluded studies from meta‐analysis if there was a differential loss to follow‐up between groups greater than 20%.

We also encountered missing data required for our analyses. Where change‐from‐baseline scores were missing for a time point in a study, we extracted numerical post‐intervention data from the appropriate graphs, calculated mean change scores and imputed standard deviations using a correlation coefficient determined using change scores at another time point in the study. Where data were presented as mean change scores with standard errors, we transformed the standard errors into standard deviations.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed potential differences between the included studies in the types of participants, interventions or controls used before pooling data.

We assessed heterogeneity between studies using the Chi2 test (with a significance level set at P < 0.10) and the I2 statistic, which calculates the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than to chance, with I2 values over 50% suggesting substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We included studies published in any language to avoid any risk of language bias. In order to minimise the risk of publication bias, we performed a comprehensive search in multiple databases, including searching for unpublished studies in trial registries. We compared outcomes reported in a trial with the protocol, wherever possible, to examine whether all of the study's prespecified outcomes that were of interest to the review had been reported.

Data synthesis

The duration of trials varied from 6 weeks up to 24 months from the time of randomisation. We conducted separate meta‐analyses where possible for short‐term (up to 2 months) and medium‐term (3 to 11 months) outcomes. It was not possible to conduct meta‐analyses for long‐term (12 months or longer) outcomes due to the limited number of studies reporting these outcomes. Durations for short‐ and medium‐term outcomes are reflective of observation in the literature that the first six weeks following ChEI discontinuation are particularly important when monitoring patients for changes in cognition and neuropsychiatric symptoms (O'Regan 2015; Herrmann 2018). Some trials contributed data to more than one meta‐analysis if multiple assessments were performed. We were not able to conduct separate meta‐analyses for short‐, medium‐ and long‐term outcomes relating to dropouts, adverse events, serious adverse events or deaths as the data available on these outcomes did not allow these distinctions to be determined.

We intended to conduct separate analyses for different dementia subtypes, but in fact all the included studies focused on Alzheimer's disease.

A weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across trials was calculated using a random‐effects model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had prespecified subgroup analyses for severity of dementia (mild to moderate and moderate to severe), but there were too few included studies to allow meaningful subgroup analysis. We were also unable to undertake subgroup analysis by duration of treatment prior to enrolment in the discontinuation trial or by method of discontinuation (abrupt versus tapered) due to the low numbers of included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of including Johannsen 2006, in which participants who showed the best response to donepezil were excluded, and of using data from differing scales measuring the same outcome, to assess the robustness of our results.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used 'Summary of findings' tables to summarise the data comparing withdrawal and continuation of cholinesterase inhibitors at short‐, medium‐ and long‐term time points on cognitive, functional and neuropsychiatric outcome measures. We also included data on dropout due to lack of efficacy of trial medication or deterioration in overall medical condition, adverse events, serious adverse events and mortality across the duration of the trials; it was not possible to separate these by time point. We used GRADE methods to assess the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome (Guyatt 2008).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

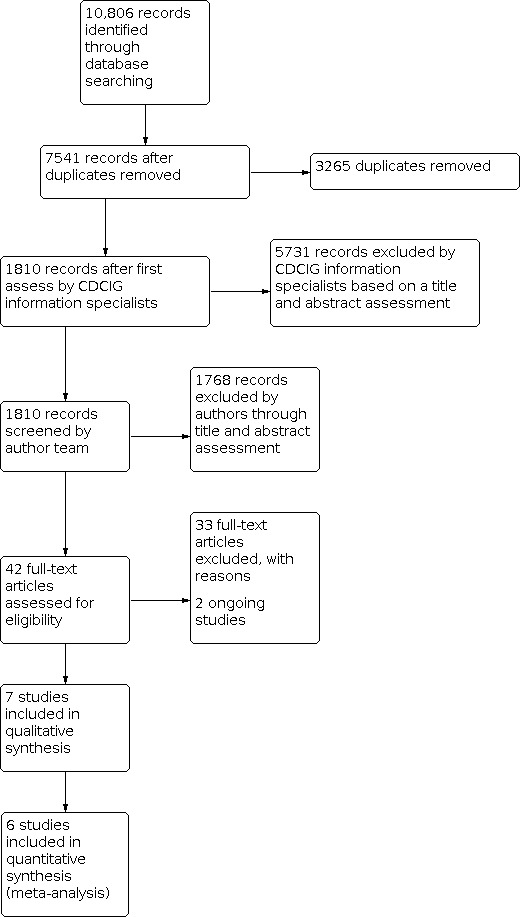

The electronic searches identified 10,806 potentially relevant citations (Figure 1). Following removal of duplicates and review of titles and abstracts by Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group information specialists, we screened 1810 records. Of these, 42 publications were identified as potentially eligible and were examined in full‐text form. We identified seven completed studies which were eligible for inclusion. We also identified two ongoing studies from clinical trial registers (See Characteristics of ongoing studies).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria (the DOMINO‐AD trial (DOMINO AD Howard); GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; Herrmann 2016; Holmes 2004; Hong 2018; Johannsen 2006). The characteristics of these studies are described in detail in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Number of participants and setting

There were a total of 955 participants randomised in the included studies, of whom 759 were assigned to groups relevant to this review. The included studies were conducted in the UK (DOMINO AD Howard; Holmes 2004), USA (GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig), Canada (Herrmann 2016), Italy (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini), South Korea (Hong 2018) and across multiple countries (Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, the Netherlands, Poland and the USA; Johannsen 2006). Participants in the studies were resident at home or in an assisted home care or long‐term care setting. Participants in GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig had previously completed a three‐month, randomised, multicentre, international clinical trial (GAL‐INT‐2; Tariot 2000). Government or charitable foundations, or both, funded two studies (DOMINO AD Howard; Herrmann 2016), and the pharmaceutical industry funded four studies (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006). Hong 2018 received a combination of government and pharmaceutical industry funding.

Dementia diagnoses and severity

Participants in four trials had a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease, according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Assocation (NINCDS‐ADRDA) criteria (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Hong 2018; Johannsen 2006), and in three trials, a diagnosis of probable or possible Alzheimer's disease according to the same criteria (DOMINO AD Howard; Herrmann 2016; Holmes 2004). In addition, patients in Herrmann 2016, Hong 2018 and Johannsen 2006 were required to meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders‐Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) criteria for dementia. Severity of dementia among participants, and the measures used to determine severity, varied across studies: Hong 2018 included patients with extremely severe Alzheimer's disease; DOMINO AD Howard and Herrmann 2016 included patients with moderate to severe dementia; GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini, GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig, Johannsen 2006 and Holmes 2004 included patients with mild to moderate dementia.

Additional criteria for inclusion and exclusion

Other inclusion criteria were also stipulated in each of the included studies. These covered prescribing of ChEIs and other medications, comorbid medical conditions, and regular contact with a caregiver. In general, patients with severe, unstable or poorly controlled medical conditions and with neurodegenerative disorders other than Alzheimer's disease were excluded. In addition, patients were excluded from Johannsen 2006 if they resided in a nursing home. Importantly, participants included in Johannsen 2006 were those who had had a poorer response (uncertain clinical benefit) to prior open‐label treatment with donepezil over 12 to 24 weeks; those thought to have derived clear benefit from the treatment were excluded. Conversely, patients were included in the double blind placebo‐controlled withdrawal phase of GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini only if they had had a good response to galantamine ‐ defined as cognitive deterioration from baseline of less than 4 points on the ADAS‐Cog/11 ‐ in the prior 12‐month open‐label treatment phase.

Description of interventions

Trial duration varied across included studies, ranging from 6 weeks up to 24 months from the time of randomisation.

All studies compared continuing ChEI or memantine to discontinuing treatment. Six of the studies used placebo substitution for the discontinued ChEI; Hong 2018 was the only study which was not placebo‐controlled.

Participants in Hong 2018 had been taking anti‐dementia drugs for at least two months prior to randomisation. The minimum duration of ChEI treatment prior to randomisation in the other trials was: 3 months, with at least 6 weeks on a stable dose (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Holmes 2004); 6 months (Johannsen 2006); 12 months (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini); or 24 months (Herrmann 2016). All treatments consisted of doses regarded as being within the therapeutic range.

In DOMINO AD Howard, participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups, two of which were relevant to this review. In the first group, participants continued to take donepezil 10 mg/day, with placebo memantine, starting in week one, and in the second group, participants took donepezil at a dose of 5 mg/day during weeks one to four and then placebo donepezil starting in week five, plus placebo memantine starting in week one.

Participants entering GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig were assigned treatment according to the group into which they had been randomised in GAL‐INT‐2. Participants who had received placebo were continued on it; this group was not relevant to the review. Participants who had received galantamine were randomised into two groups: a withdrawal group, in which galantamine was discontinued abruptly and participants received a placebo, or a continuation group, in which galantamine treatment was continued at the same dosage as in the previous trial (24 mg/day or 32 mg/day, in two divided doses). These withdrawal and continuation groups were included in this review.

In Hong 2018, no differentiation was made between donepezil and memantine, both of which were classed as anti‐dementia drugs. Participants were randomly assigned to continuation or abrupt discontinuation of anti‐dementia drug treatment.

In Holmes 2004, Johannsen 2006 and GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini, ChEI treatment was also discontinued abruptly, from 10 mg/day donepezil (Holmes 2004 and Johannsen 2006) or 16 mg/day galantamine in two divided doses (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini).

In Herrmann 2016, participants in the discontinuation group were tapered off their baseline dose of ChEI (donepezil, galantamine or rivastigmine) for two weeks and then took placebo for the remaining six weeks of the study period.

Outcomes

The included studies examined cognitive, functional and global outcomes, neuropsychiatric symptoms, quality of life and safety, tolerability and adverse effects, and mortality. Measures used to assess many of these outcomes varied across studies; Appendix 2 provides a list of the assessment scales used. Institutionalisation was also considered by DOMINO AD Howard, in which nursing home placement was a secondary outcome measure. Time to dropout was considered by two studies (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini and Hong 2018). All included studies considered adverse events, safety and tolerability. Quality of life was considered for the patient by DOMINO AD Howard and Herrmann 2016, and the caregiver by DOMINO AD Howard.

Excluded studies

Excluded publications that were read in full are summarised along with the reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias in all included studies, across the following domains: random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective reporting (reporting bias); and other potential sources of bias.

See 'Risk of bias' tables in Risk of bias in included studies, overall 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2), and risk of bias summary (Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged six studies to be at low risk of selection bias due to random sequence generation (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; Herrmann 2016; Holmes 2004; Hong 2018; Johannsen 2006). GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig was considered to be at unclear risk of bias for this domain as the Clinical Research Report indicated that 28 patients were randomised out of sequence.

We judged four studies to be at low risk of selection bias due to allocation concealment (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Hong 2018), with the remaining three studies considered to be at unclear risk (Herrmann 2016; Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006), as no details were reported regarding allocation concealment.

Blinding

We judged three studies to be at low risk of performance bias (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Herrmann 2016), three at unclear risk due to lack of adequate descriptive detail (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006), and one study (Hong 2018) to be at high risk of bias in this domain, as participants and personnel were not blinded to treatment allocation, and it was possible that participants' perceptions may have been affected by their knowledge of the treatment group to which they were allocated. This may have indirectly made them more aware of side effects of drug withdrawal or may have resulted in more severe rating of symptoms. Similarly, investigators may have been influenced by knowledge of treatment allocation when advising patients to look out for certain side effects of drug withdrawal.

We judged three studies to be at low risk of detection bias (DOMINO AD Howard; Herrmann 2016; Hong 2018). We considered the remaining four studies to be at unclear risk of bias in this domain (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006), as no details were provided of how blinding of outcome assessment was undertaken.

Incomplete outcome data

We deemed three studies (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Hong 2018) to be at low risk of attrition bias. We considered two studies to be at unclear risk of attrition bias (Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006). In these studies, the results of the Intent‐to‐Treat with Last Observation Carried Forward (ITT‐LOCF) analyses differed from those of the observed case (OC) analyses, and discontinuations could be linked to participants' health status. We judged two studies to be at high risk of bias (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; Herrmann 2016) due to the proportion of missing data differing in the continuation and discontinuation groups and because discontinuations could be linked to participants' health status. Furthermore, in Herrmann 2016, there was no evidence in the analysis methods or sensitivity analyses that correction for bias was undertaken, and no information was provided on the imputation of missing data, despite Figure 1 clearly demonstrating that there were dropouts after randomisation.

Selective reporting

We judged risk of reporting bias to be low for three studies (DOMINO AD Howard; Holmes 2004; Hong 2018), and deemed three studies to have an unclear risk of bias. In GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini, Clinical Interview Based Impression of Change‐Plus Caregiver Input (CIBIC‐plus) scores (one of the specified secondary outcome measures) were not reported, and the study was not sufficiently powered for ADAS‐Cog/11 survival analysis. In GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig, the clinical study report stated that both Traditional Division of Neuropharmacological Drug Product with Last Observation Carried Forward (Traditional DNDP‐LOCF) and OC analyses were performed, but the published paper reported only the OC analyses. In Herrmann 2016, the number of 'as needed' medications used to treat behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) was not reported, for the Clinician's Global Impression (CGI) outcome measure, it was not made explicit whether this was the Clinician's Global Impression‐Severity (CGI‐S) measure which considers severity, and the baseline Cornell Depression Scale for Dementia scores were not reported. Johannsen 2006 was considered to have a high risk of bias because ADAS‐Cog/11, MMSE, Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) and Disability Assessment in Dementia (DAD) were measured at weeks 6 and 12, but only results at week 12 were reported.

Other potential sources of bias

We considered DOMINO AD Howard, Herrmann 2016 and Hong 2018 to be at low risk of other sources of bias. We considered GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini, GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig, Holmes 2004, and Johannsen 2006 to be at unclear risk of bias since pharmaceutical companies which manufactured galantamine (GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig) and donepezil (Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006) funded the analysis and writing of the manuscripts.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Six of the seven included trials investigated the effect of withdrawal of ChEIs. Three trials investigated withdrawal of donepezil and two trials examined withdrawal of galantamine. One trial was a pilot study in 40 patients, which investigated withdrawal of any ChEI (Herrmann 2016). In this trial, there were very small numbers of patients taking donepezil (N = 17; with 7 in the placebo group and 10 in the continuation group), galantamine (N = 16; with 8 in the placebo group and 8 in the continuation group) and rivastigmine (N = 7; with 4 in the placebo group and 3 in the continuation group) at baseline. We were able to include between two and six trials in each meta‐analysis, depending on the outcome and time point being considered. A seventh trial (Hong 2018) investigated the effect of withdrawing either a cholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil) or memantine, and did not report results for the two drug classes separately. We did not include this trial in the quantitative syntheses. The meta‐analysis results and evidence quality for each outcome for the main comparison (discontinuation compared to continuation of ChEI) are described in the Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Cognitive function

The seven included trials considered a range of time points and cognitive outcomes.

In the meta‐analyses, we considered the effect of discontinuation versus continuation of ChEIs at two different time points, short term (up to 2 months) and medium term (3 to 11 months), using pooled data from four studies and three studies respectively. As different cognitive outcome measures were employed by the included studies, we used standardised mean differences as the measure of effect size.

For the short‐term effect, four studies (344 participants) reported data relevant to this outcome (DOMINO AD Howard; GAL‐USA‐5 Gaudig; Herrmann 2016; Holmes 2004). Discontinuation may reduce cognitive function compared to continuing ChEI treatment (SMD ‐0.42, 95% CI ‐0.64 to ‐0.21; 344 participants, 4 studies; Analysis 1.1). We assessed the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome as low, downgraded one level for risk of bias and one level for imprecision. Johannsen 2006 also measured cognitive function at six weeks, but did not report the results.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Cognitive function, Outcome 1: Cognitive function (change from baseline, short term)

For the medium‐term effect, three studies (411 participants) reported data relevant to this outcome (DOMINO AD Howard; Holmes 2004; Johannsen 2006). For DOMINO AD Howard, we included data from two treatment groups: continuation of donepezil with placebo memantine, and discontinuation of donepezil with placebo memantine. We considered the evidence behind our main analysis to be very low certainty, downgraded for inconsistency, imprecision and risk of bias. Therefore we are very uncertain of the effect of discontinuation of ChEI on cognitive function (SMD ‐0.40, 95% CI ‐0.87 to 0.07; 411 participants, 3 studies; Analysis 1.2). Heterogeneity in this analysis was high (I2 = 81%). We conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding data from Johannsen 2006 which had included only participants with a poor response to donepezil, who might be expected to show less effect of discontinuation. When these data were omitted, the heterogeneity was reduced (I2 = 24%) and the result favoured continuation (SMD ‐0.62, 95% CI ‐0.94 to ‐0.31; 219 participants, 2 studies; P < 0.001). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the impact of using MMSE data rather than ADAS‐Cog/11 data from Johannsen 2006 on the conclusions regarding cognition. We found that using MMSE data made little difference to the effect estimate (SMD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.96 to 0.34; P = 0.35) and heterogeneity remained very high (I2 = 90%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Cognitive function, Outcome 2: Cognitive function (change from baseline, medium term)

For the long‐term effect, data relevant to this outcome were only available for one study (DOMINO AD Howard). Discontinuation probably reduces cognitive function compared to continuing donepezil treatment (MD ‐2.09 SMMSE points, 95% CI ‐3.43 to ‐0.75; 108 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.3). The wide confidence interval and data from a single study affect our certainty about the result (moderate certainty evidence, downgraded one level due to imprecision).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Cognitive function, Outcome 3: Cognitive function (change in SMMSE from baseline, long term)

We did not include data from GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini and Hong 2018 in the quantitative syntheses due to the nature of the study design or the outcome measures selected, or both. GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini withdrew participants when they experienced a deterioration in ADAS‐Cog/11 score of 4 points or more, and reported time to deterioration as the study endpoint. Hong 2018 did not differentiate between participants who were discontinuing donepezil and those discontinuing memantine.

In GAL‐ITA‐2 Scarpini, there was no statistically significant difference in the likelihood of premature study discontinuation due to a confirmed deterioration in ADAS‐Cog/11 score of 4 points or more between participants switched to placebo and those continuing galantamine (HR 1.66, 95% CI 0.78 to 3.54; P = 0.19). The authors examined the number of participants in each group who experienced lack of efficacy (defined as the subjective impression of their caregiver or general practitioner, and deterioration of 4 points or more in the ADAS‐Cog/11 score). Participants taking placebo were more likely to discontinue the study prematurely than those continuing galantamine (HR 1.80, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.18; P = 0.04). The authors reported that 47% of participants who continued galantamine completed the 24‐month follow‐up without showing a change of ADAS‐Cog/11 score of 4 points or more, compared to 30% of those in the discontinuation group, and concluded that galantamine was effective in delaying time to cognitive deterioration in people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.

Hong 2018 reported the change in Baylor Profound Mental State Examination (BPMSE) scores from baseline to 12 weeks in the drug‐continuation group (0.4 point improvement) and the drug‐discontinuation group (0.5 point decline). Our analysis suggests that there was no evidence of a difference between groups (MD ‐0.90 BPMSE points; 95% CI ‐2.18 to 0.38; 57 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.4). The authors also reported no significant difference between the groups in changes from baseline on the MMSE. There was a 0.3 point decline in the continuation group and a 0.3 point improvement in the discontinuation group, and our analysis concurs with their conclusion (MD 0.60 MMSE points, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 1.29; 57 participants, 1 study; Analysis 1.5).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Cognitive function, Outcome 4: Cognitive function (change in BPMSE from baseline, medium term) for Hong 2018

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Cognitive function, Outcome 5: Cognitive function (change in MMSE from baseline, medium term) for Hong 2018

Functional outcomes (performance of activities of daily living)