The ascomycete Cryphonectria parasitica causes destructive chestnut blight, which is controllable by hypovirulence-conferring viruses infecting the fungus. The tripartite chestnut/C. parasitica/virus pathosystem involves the dynamic interactions of their genetic elements, i.e., virus transmission and lateral transfer of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes between fungal strains via anastomosis occurring in trees.

KEYWORDS: Cryphonectria parasitica, chestnut blight fungus, hypovirus, mitovirus, mycovirus, reovirus, virus spread

ABSTRACT

The ascomycete Cryphonectria parasitica causes destructive chestnut blight. Biological control of the fungus by virus infection (hypovirulence) has been shown to be an effective control strategy against chestnut blight in Europe. To provide biocontrol effects, viruses must be able to induce hypovirulence and spread efficiently in chestnut trees. Field studies using living trees to date have focused on a selected family of viruses called hypoviruses, especially prototypic hypovirus CHV1, but there are now known to be many other viruses that infect C. parasitica. Here, we tested seven different viruses for their hypovirulence induction, biocontrol potential, and transmission properties between two vegetatively compatible but molecularly distinguishable fungal strains in trees. The test included cytosolically and mitochondrially replicating viruses with positive-sense single-stranded RNA or double-stranded RNA genomes. The seven viruses showed different in planta behaviors and were classified into four groups. Group I, including CHV1, had great biocontrol potential and could protect trees by efficiently spreading and converting virulent to hypovirulent cankers in the trees. Group II could induce high levels of hypovirulence but showed much smaller biocontrol potential, likely because of inefficient virus transmission. Group III showed poor performance in hypovirulence induction and biocontrol, while efficiently being transmitted in the infected trees. Group IV could induce hypovirulence and spread efficiently but showed poor biocontrol potential. Nuclear and mitochondrial genotyping of fungal isolates obtained from the treated cankers confirmed virus transmission between the two fungal strains in most isolates. These results are discussed in view of dynamic interactions in the tripartite pathosystem.

IMPORTANCE The ascomycete Cryphonectria parasitica causes destructive chestnut blight, which is controllable by hypovirulence-conferring viruses infecting the fungus. The tripartite chestnut/C. parasitica/virus pathosystem involves the dynamic interactions of their genetic elements, i.e., virus transmission and lateral transfer of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes between fungal strains via anastomosis occurring in trees. Here, we tested diverse RNA viruses for their hypovirulence induction, biocontrol potential, and transmission properties between two vegetatively compatible but molecularly distinguishable fungal strains in live chestnut trees. The tested viruses, which are different in genome type (single-stranded or double-stranded RNA) and organization, replication site (cytosol or mitochondria), virus form (encapsidated or capsidless) and/or symptomatology, have been unexplored in the aforementioned aspects under controlled conditions. This study showed intriguing different in-tree behaviors of the seven viruses and suggested that to exert significant biocontrol effects, viruses must be able to induce hypovirulence and spread efficiently in the fungus infecting the chestnut trees.

INTRODUCTION

Chestnut blight, caused by the ascomycete Cryphonectria parasitica, is one of the most destructive tree diseases (1, 2). The fungus infects the stem and branches of susceptible chestnut trees, causing rapidly expanding bark lesions, called cankers (3). This disease could be controlled by naturally disseminating viruses conferring hypovirulence in certain areas of Europe or by treating cankers with hypovirus-infected fungal strains (3, 4). Another type of attempt to control chestnut blight in the United States is to spray chestnut forests with engineered conidia that carry infectious cDNA of the prototype hypovirus CHV1 (Cryphonectria hypovirus 1) in their chromosomes and are able to allow CHV1 replication upon germination (5). The latter treatment is often impaired by the self/nonself intraspecies recognition system, so-called vegetative incompatibility, genetically governed by 6 diallelic loci (vic1 to vic4, vic6, and vic7) (6). These loci have been molecularly characterized by Nuss and colleagues (7, 8), and their genotyping can be readily conducted by PCR-based methods (9, 10). To breach the restriction imposed by vegetative incompatibility, Zhang and Nuss prepared a “super donor” formula, a mixture of two independent quadruple disruptions of four of six vic genes, which allows lateral transmission of the prototype hypovirus CHV1-EP713 to any known fungal strain (11).

Other viruses besides CHV1 have been found in C. parasitica in natural settings. In North America, the hypovirus CHV3 has been the subject of several studies and releases for attempted biocontrol (12, 13), and CHV4 has been studied to a lesser extent (14). Local screening for presence of CHV2 was performed where it was first identified (15), and broader screenings have been performed in the northeastern United States for viruses including CHV1, CHV2, CHV3, and CHV4 (16), but these studies did not include virus releases. Thus, CHV1 and CHV3 have been the subjects of most of the virus releases for the purpose of controlling C. parasitica in natural settings, with CHV1 representing the great preponderance.

C. parasitica is also important as a virus host organism for studying virus/virus and virus/host interactions (17, 18). This fungus supports the replication of diverse viruses, not only those discovered in C. parasitica itself (referred to here as homologous viruses) (19) but also viruses originally detected in different fungi, as exemplified by several viruses from Rosellinia necatrix, which belongs to an order different from C. parasitica (referred to here as heterologous viruses) (19–24). These viruses all fall within the realm Riboviria, accommodating all RNA viruses but retroviruses (25), and span over 10 families, including Hypoviridae, Reoviridae, Mitoviridae, Totiviridae, and Partitiviridae, with different genome organizations (19; N. Suzuki, unpublished results). It is of interest that beside CHV1, other homologous viruses originally isolated from C. parasitica and some heterologous viruses isolated from different fungi also confer hypovirulence to the chestnut blight fungus under laboratory conditions. Also of note is that while most viruses of C. parasitica are cytosolically replicating, the fungus was the first shown to host a mitochondrially replicating virus (26), now known to be common in fungi.

The tripartite chestnut/C. parasitica/virus pathosystem involves the dynamic interactions of their genetic elements that include virus transmission and lateral transfer of nuclear and mitochondrial genomes between fungal strains via anastomosis that occurs in trees. Most studies aiming at exploring such tripartite interactions are limited to those with members of the family Hypoviridae (hypoviruses), including CHV1, and field-level or chestnut tree-level investigations of other viruses are scarce. CHV1 is able to reduce considerably the pigmentation, sporulation, and virulence of host fungus; CHV1-infected fungi typically lose the ability to invade aggressively and kill chestnut trees. In-tree behavior of hypovirulent fungal strains was earlier investigated in American chestnut sprouts (Castanea dentata) using two vegetatively compatible fungal strains with distinct nuclear genetic backgrounds (27). The study investigated how the virus and host fungus spread in cankers and showed the transmission of an uncharacterized hypovirulence-inducing agent (virus) from the fungus used for challenge inoculation to the virulent fungus used as the primary inoculation. Another related interesting study in a natural setting showed dynamic exchange of genetic materials at the population levels in a chestnut coppice between virus-free resident and experimentally introduced CHV1-infected fungi (28). Long-term monitoring showed efficient spread of CHV1 as well as relatively less efficient spread of the mitochondrial genome of the introduced strain in the resident fungal population.

In the current study, we tested seven different viruses for their hypovirulence induction, biocontrol potential, and spread in the fungus using European chestnut trees (Castanea sativa). Biocontrol potential in this study refers to curative effects of virus-infected fungal strains against specific virulent cankers, rather than their biocontrol performance at field level, which includes spontaneous dissemination of the virus in the pathogen population. This study showed different in-tree behaviors of the viruses and suggested that to exert significant biocontrol effects, viruses must be able to induce hypovirulence and spread efficiently in the fungus infecting the chestnut trees.

RESULTS

Phenotypes of virus-infected C. parasitica strains EP155 and PC7.

Fungal and viral strains used in the current study are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A total of seven RNA viruses were tested: two double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses, Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 6 strain W113 (RnPV6-W113; bi-segmented dsRNA genome; genus Betapartitivirus, family Partitiviridae) and mycoreovirus 1 (MyRV1-9B21; 11-segmented; genus Mycoreovirus, family Reoviridae); four hypoviruses with positive-strand RNA genomes, the prototype hypovirus CHV1 wild-type (WT) strain EP713 (CHV1-EP713; genus Hypovirus, family Hypoviridae), an RNA silencing suppressor (RSS) deletion mutant of CHV1-EP713 (Δp69), Cryphonectria hypovirus 2 strain NB58 (CHV2-NB58; genus Hypovirus), and Cryphonectria hypovirus 3 strain GH2a (CHV3-GH2a; genus Hypovirus); and a mitochondrially replicating virus, Cryphonectria mitovirus 1 strain NB631 (CpMV1-NB631; genus Mitovirus, family Mitoviridae). In order to trace in-tree spread of both virus and fungus, we introduced viruses into two fungal strains, EP155 and PC7, that were genetically distinguishable based on nuclear genotype as well as mitochondrial haplotype but belonged to the same vegetative compatibility (VC) type. The standard C. parasitica strain EP155 was infected by the above seven viruses, and the viruses were then transferred from EP155 to PC7 via anastomosis. Symptom induction profiles for CHV2-NB58 were similar to those reported earlier for the original CHV2-NB58-bearing C. parasitica strains but were less severe than those reported for CHV3 (13, 29), as discussed below (Fig. 1). Symptom induction in EP155 by the other viruses was as described before (Fig. 1) (22, 30–32). See below for symptom descriptions.

TABLE 1.

Viral strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Original host | Accession no | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyRV1-9B21 | Exemplar strain of Mycoreovirus 1 within the genus Mycoreovirus | Cryphonectria parasitica strain 9B21 | AY277888–AY277890, AB179636–AB179643 | 30, 49 |

| CHV1-EP713 | Prototype of the family Hypoviridae | Cryphonectria parasitica strain EP713 | M57938 | 62 |

| CHV1-Δp69 | ORF-A deletion mutant of CHV1-EP713 lacking the p29 and p40 coding domains | Genetically engineered | M57938 | 32 |

| CHV2-NB58 | Exemplar strain of Cryphonectria hypovirus 2 | Cryphonectria parasitica strain NB58 | L29010 | 51 |

| CHV3-GH2a | Exemplar strain of Cryphonectria hypovirus 3 | Cryphonectria parasitica strain GH2 | AF188515 | 29 |

| CpMV1-NB631 | Exemplar strain of Cryphonectria mitovirus 1 | Cryphonectria parasitica strain NB631 | L31849 | 26 |

| RnPV6-W113 | Exemplar strain of Rosellinia necatrix partitivirus 6 | Rosellinia necatrix strain W113 | LC010952, LC010953 | 22 |

TABLE 2.

Fungal strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | VC type (vic genotypea) | Mating type | Isolation site and yr | Strain collection no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP155 | Standard strain of Cryphonectria parasitica (virus free) | EU5 (2211-22) | MAT1-2 | Bethany, CT, USA; 1977 | ATCC 38755 |

| PC7 | Field-collected isolate (virus free) | EU5 (2211-22) | MAT1-2 | Bergamo, Italy; 1993 | M1334 |

vic genotype is expressed according to reference 7.

FIG 1.

Colony morphology of PC7 and EP155 infected with different viruses. EP155 (top row) and PC7 (bottom row) infected by the seven virus strains were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Introduced viruses, listed in Table 1, are shown at the top and bottom. Colonies were grown on PDA for 1 week on the benchtop at approximately 23°C and photographed. Virus-free EP155 and PC7 were grown in parallel.

We confirmed through anastomosis experiments that the virulent, virus-free strain PC7 could receive viruses from EP155. All of the seven viruses tested could move from EP155 to the recipient PC7 strain on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates and were stable in the new host. All of these fungal strains were confirmed to be infected by the respective viruses by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). Symptoms induced by CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, and MyRV1-9B21 were similar to one another and characterized by reduced growth of aerial mycelia and enhanced brown pigmentation. CHV1-EP713 reduced orange pigmentation and mycelial growth rate, while RnPV6-W113 caused severe growth reduction in culture. CHV3-GH2a and CpMV1-NB631 exerted little effect on culture morphology. However, it should be noted that MyRV1-9B21 and RnPV6-W113 were less efficiently moved to PC7. This phenomenon was not due to host genotype differences but to intrinsic virus attributes, because it was also observed in their transfer from EP155 to EP155. Symptoms induced by these viruses in PC7 grown on PDA were indistinguishable from those in EP155 (Fig. 1), suggesting no significant difference in effects of viruses on virulence attenuation between the two fungal strains.

Virulence of virus-infected C. parasitica strain EP155.

Three-year-old European chestnut trees (Castanea sativa) were used in three different assays to investigate (i) virulence, (ii) in-tree spread of different viruses, and (iii) biocontrol effects of fungal strains infected with different viruses (see Fig. 2 and Materials and Methods for details).

FIG 2.

Schematic representation of the experimental procedures to assess biocontrol potential and in-tree spread of viruses. For both assays, the European virulent strain PC7 was inoculated into European chestnut trees (shown by blue circles) with the aid of a cork borer (A). Two weeks postinoculation, the trees were challenged (shown by yellow circles) with EP155 colonies infected with different viruses (Table 1) at one (for assay II, virus spread) or eight sites (for assay III, biocontrol) on the periphery of virulent cankers (shown by brownish ovals) induced by PC7 (B) with the aid of a cork borer. For fungal isolation, bark plugs were obtained from a total of 18 sites (for virus spread assay) or 4 sites inside the original canker area plus 4 sites in expanded areas (for the biocontrol assay) for challenge inoculation with CHV3-GH2a-, RnPV1-W113-, CpMV1-NB631-, and MyRV1-9B21-infected EP155 (C). For challenge inoculation with the remaining virus-infected colonies, only four inside plugs were utilized, because the original virulent cankers became inactive and failed to expand. Bark sampling was performed 3 and 6 weeks (for the virus spread assay) and 2 months (for the biocontrol assay) after challenge inoculation with the aid of a bone marrow needle. Isolated fungi were examined for virus infection and nuclear and mitochondrial genotypes.

In assay I, we tested the virulence levels of EP155 infected by the respective viruses using living chestnut trees under controlled conditions. As shown in Table 3, virulence of fungal strains as measured by canker sizes 2, 4, and 6 weeks and 2 months postinoculation varied depending on infecting viruses. Differences among the fungal strains were pronounced as incubation time became longer. Virulence levels measured 2 months postinoculation are shown in Fig. 3. The virulence levels determined by the current study were generally congruent with those reported using their original fungal isolates and other assay systems with apple fruits and/or chestnut dormant stems. Namely, CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, and MyRV1-9B21 induced great hypovirulence, whereas RnPV6-W113-infected EP155 caused much larger cankers, approaching the level exhibited by virus-free EP155. Our CHV3-GH2a-infected EP155 isolate also caused larger cankers, indicating a difference between this isolate and the original CHV3-GH2 strain (33, 34). CpMV1-NB631, which had never been tested for virulence attenuation using isogenic fungal strains, was shown to confer a level of hypovirulence similar to that seen with CHV1-EP713. It was anticipated that RnPV6-W113 would induce hypovirulence, given the observation that the virus caused great reduction in culture growth on PDA and on apple fruits (22). However, RnPV6-W113 did not cause significant hypovirulence in living chestnut trees. This was not due to spontaneous loss of RnPV6-W113 during fungal growth in trees, because all 22 fungal isolates recovered from three cankers induced by RnPV6-W113-infected EP155 harbored the virus (data not shown). A difference from the literature was noted for CHV3-GH2a; CHV3-GH2a did not induce great hypovirulence (Table 3), whereas the virus had earlier been reported to cause hypovirulence (29, 33, 34). It should be mentioned that CHV3-GH2 transferred to EP155 does not carry defective RNAs that were carried in the original field-collected GH2 strain (35).

TABLE 3.

Mean canker areas induced by virus-infected and virus-free EP155 fungal colonies

| Infecting virus | Canker area (cm2)a |

% VDRb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 wk (Oct 23) | 4 wk (Nov 7) | 6 wk (Nov 21) | 2 mo (Dec 9) | ||

| CHV1-EP713 | 0.99 ± 0.41 | 1.26 ± 0.39 | 1.09 ± 0.38 | 1.13 ± 0.28 | 94.4 (17/18) |

| CHV1-Δp69 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.69 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.11 | 0.76 ± 0.11 | 96.7 (30/31) |

| CHV2-NB58 | 0.50 ± 0 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 93.3 (14/15) |

| CHV3-GH2a | 2.29 ± 0.31 | 4.41 ± 0.20 | 12.93 ± 7.42 | 22.30 ± 10.65 | 93.3 (14/15) |

| MyRV1-9B21 | 0.50 ± 0 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.08 | 66.7 (22/33) |

| RnPV6-W113 | 1.16 ± 0.38 | 3.06 ± 1.57 | 9.99 ± 3.66 | 18.28 ± 6.18 | 73.3 (11/15) |

| CpMV1-NB631 | 0.50 ± 0 | 2.33 ± 1.40 | 2.46 ± 1.50 | 2.72 ± 1.50 | 94.4 (17/18) |

| None (EP155) | 4.14 ± 1.39 | 9.57 ± 1.49 | 20.31 ± 3.77 | 29.10 ± 3.39 | 0 (0/10) |

Averages and standard deviations calculated from three biologic replicates are shown.

VDR, virus detection rates of fungal isolates recovered on 20 December. The parenthetical values indicate the numbers of virus-carrying colonies and colonies tested. The number of fungal isolates recovered from bark cankers varied.

FIG 3.

Virulence of EP155 infected by different viruses. Three trees per virus-infected strain were inoculated. Virulence levels were expressed by areas of cankers induced by the respective fungal strains that were measured 2 months postinoculation. Virus-free EP155 was also inoculated into three chestnut trees in parallel. (A) Mean canker areas and standard deviations calculated from the values in panel B. (B) Canker areas measured for three trees per virus-infected strain 2 months postinoculation. Measurements made at different time points are shown in Table 3.

At least one and in most cases two or three fungal isolates were obtained from each canker induced by the respective virus-harboring fungi 74 days postinoculation. Approximately 30% of fungal isolates derived from cankers induced by the MyRV1-9B21- and RnPV1-W113-harboring fungal strains were virus free, suggesting emergence of virus-free sectors within the canker. In the other cases, all recovered fungal isolates were confirmed to be infected by expected viruses (Table 3) with only a few exceptions. As expected, nine isolates recovered from three virus-free EP155-induced cankers remained virus free, confirming no virus contamination in the biosafety level 3 (BSL3) greenhouse environments.

Virus spread in chestnut trees.

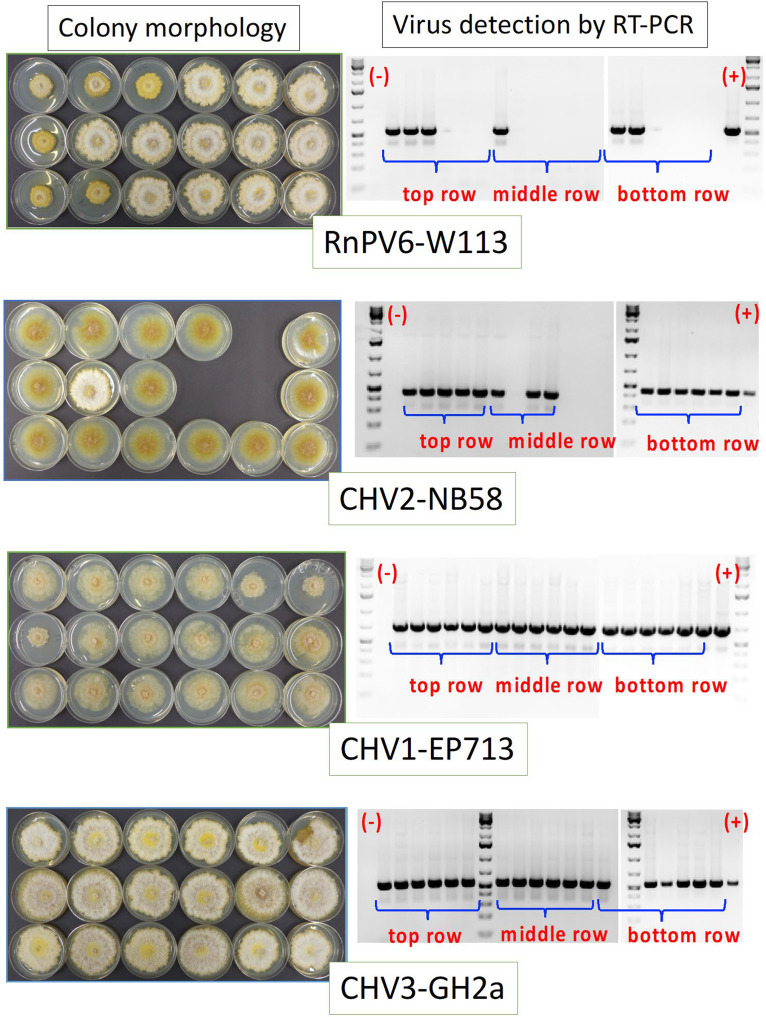

In assay II, 2 weeks following the inoculation of chestnut trees with the virulent, virus-free strain PC7, the trees were challenged with EP155 strains infected with different viruses at the lower end of the growing cankers (Fig. 2). Three and 6 weeks after the challenge inoculation (Fig. 1), six bark plugs were taken from each of three rows of the single canker (Fig. 1), and the fungal isolates recovered were tested for virus infection. This experiment was repeated once (experiments I and II). Virus infection was determined by phenotypic observation and RT-PCR (Fig. 4). Phenotypic diagnosis was useful for highly symptomatic viruses, such as CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, MyRV1-9B21, and RnPV6-W113, and fully agreed with that based on RT-PCR (Fig. 4, RnPV6-W113 and CHV2-NB58). Virus detection rates are summarized in Table 4. Interesting differences in virus detection rates were observed. CHV1-EP713 and CHV3-GH2a were found to move to the top edge of the canker within 3 weeks, while RnPV6-W113 did not move up to the top in one of the cankers in experiment I (Fig. 4). It is, however, worth noting that the detection patterns of RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21 varied depending on cankers or experiments and that viruses were not necessarily detected more frequently at 6 weeks after challenge inoculation (Table 4). As summarized in Table 4, CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, CHV3-GH2a, and CpMV1-NB631 showed higher (>93.6%) virus detection rates, whereas the other two viruses, RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21, were detected at lower frequencies (<75.8%). This was consistent with the results of the bench virus transmission assay via anastomosis. Virus-free fungal isolates tended to be obtained frequently from the middle row in the spread assay with RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21 (Fig. 5A and B). A similar trend was observed for other efficiently spreading viruses.

FIG 4.

Virus transmission in chestnut trees. As shown in Fig. 2, 3-year-old chestnut trees were first inoculated with a virus-free virulent fungal strain, PC7. EP155 strains each infected by the respective viruses were inoculated at the lengthwise growing edge of the canker 2 weeks after the first inoculation. Eighteen bark plugs were taken and placed on water agar containing streptomycin to isolate fungal strains. After a few days, mycelia were transferred to PDA plates. Fungal isolates obtained 3 weeks postchallenge inoculation from cankers treated with RnPV6-W113-, CHV2-NB58-, CHV1-EP713-, and CHV3-GH2a-infected EP155 were cultured on PDA for 1 week on the benchtop and photographed (left). RT-PCR analysis of the fungal isolates recovered from bark samples was carried out (right). Direct colony RT-PCR with toothpicks was employed to examine recovered fungal isolates for virus infection. Amplified cDNA fragments were electrophoresed in 1.2% agarose gel in the 1× TBE buffer system (89 mM Tris-borate, 89 mM boric acid, 2.5 mM EDTA [pH 8.3]). GeneRuler 1 kb Plus DNA ladders (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used as size standards. Virus transmission rates are summarized in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Summary of virus spread assaya

| Virus strain | Expt I |

Expt II |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 wks postchallenge |

6 wks postchallenge |

3 wks postchallenge |

6 wks post challenge inoculation |

|||||||||||||||||

| VDR | Nuclear genotype |

MH | VDR | Nuclear genotype |

MH | VDR | Nuclear genotype |

MH | VDR | Nuclear genotype |

MH | |||||||||

| PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | |||||||||

| CHV1-EP713 | 18/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT | 16/17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | NT | 12/13 | 13 | 0 | 0 | NT | 17/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| CHV1-Δp69 | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT | 14/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT | 12/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| CHV2-NB58 | 14/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT | 14/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT | 14/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| CHV3-GH2a | 18/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT | 17/17 | 14 | 0 | 3d | NT | 15/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT | 14/15 | 14 | 0 | 1d | NT |

| MyRV1-9B21 | 11/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT | 11/18b | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT | 12/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT | 11/15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| RnPV6-W113 | 6/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NT | 17/17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | NT | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NT | 11/15c | 15 | 0 | 0 | NT |

| CpMV1-NB631 | 16/17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | PC7 | 14/17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | PC7 | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | PC7 | 17/18 | 17 | 0 | 1 | PC7 |

FIG 5.

Schematic representation of bark sampling sites for virus-free isolates and isolates with a mixture of the EP155 and PC7 genomes. Incomplete spread of MyRV1-9B21 (A) and RnPV1-W113 (B) and detection of the EP155 nuclear genome in the CHV3-GH2a spread assay (C). As shown in Fig. 1, the blue and yellow filled circles indicate the sites of the primary and challenge inoculations. Gray circles indicate the sites where the respective virus was detected, and white circles indicate where it was not detected. (A) Results of experiment I 6 weeks after challenge inoculation. (B) Results of experiment II 6 weeks after challenge inoculation (Table 4). (C) Genotyping revealed a mixture of the EP155 and PC7 nuclear genomes in a few isolates obtained from the CHV3-GH2a spread experiments I and II (Table 4). Orange symbols indicate the four sampling sites from which isolates with the mixed genotype were recovered. Gray symbols denote the sites where only the PC7 genotype was present.

These results clearly indicate that different viruses have different spread efficiencies in trees. The relatively lower spread rates of the two viruses RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21 may be associated with the lower detection rates of the viruses in assay II (virulence assay) (Table 3). Note that all of the fungal isolates cultured from the infected trees were confirmed to have the PC7 genetic background when tested for microsatellite markers (see below), indicating that lateral virus transmission had occurred from fungal strain EP155 to PC7 in trees, rather than simple overgrowth and reisolation of the original virus-infected EP155 inoculum.

Biocontrol potential of viruses.

The seven viruses tested in this study include dsRNA viruses and positive-strand RNA viruses whose biocontrol potential had not been explored comparatively under controlled conditions. As for assay II, chestnut trees were primarily inoculated with the virulent, virus-free strain PC7, but the challenge inoculation was made at the eight periphery sites of the growing cankers in assay III (Fig. 2). The potential ability of these viruses to serve as biological control agents was measured by inhibition of canker expansion and reduction of mortality caused by the primary inoculation with the virulent chestnut blight fungus (Fig. 2). They showed great variation in biocontrol effects. Representative canker morphology is shown in Fig. 6A to illustrate how challenge inoculation of the trees with each virus-infected fungal EP155 strain contributed to the repression of virulent or active cankers. Figure 6B and Table 5 summarize the biocontrol effects of the respective viruses. CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, and CHV2-NB58 exerted significant biocontrol effects, whereas CHV3-GH2a and RnPV6-W113 did not and allowed canker expansion, similar to the treatment with agar (negative control). CpMV1-NB631 and MyRV1-9B21 inhibited canker expansion at a statistically significant, albeit modest, level (Fig. 6). Approximately 3 months after challenge inoculation with RnPV6-W113-, CHV3-GH2a-, and CpMV1-NB631-infected colonies, chestnut leaves were wilting, a sign of destroyed function of vascular tissue, as in the case of treatment with agar (Fig. 7). No wilting symptoms were observed when virulent cankers were challenged with CHV1-EP713, CHV2-NB58, or CHV1-Δp69 (Fig. 7 and data not shown).

FIG 6.

Biological control effects of different viruses. Three-year-old European chestnut trees were first inoculated with a virus-free virulent fungal strain, PC7, at one site per tree (Fig. 2). After 2 weeks, the trees (five per fungal strain) were challenged by EP155 infected with different viruses (Table 1) inoculated at 8 sites per tree at the periphery of growing cankers. Resulting cankers induced by the first and second challenge inoculations were photographed 8 weeks after the first inoculation. (A) Representative cankers, with the viruses used for the challenge inoculation shown at the bottom. Cankers induced by the challenge inoculation with agar as a negative control in parallel are also shown. The original canker area induced by PC7 at the time point of the challenge inoculation is shown by a white bracket, while the expanded canker area 6 weeks after challenge inoculation is indicated by a yellow bracket. Canker areas were measured 6 weeks after challenge inoculation. (B) Mean canker expansions and standard deviations, calculated by five biological replicates. Biocontrol effects of viruses on the fungal pathogen are greater as canker expansions are smaller.

TABLE 5.

Growth of canker area after challenge inoculations with virus-infected fungal carrier EP155

| Infecting virus | Canker area (cm2)a |

Canker expansion 8 wks after biocontrol treatmentb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 wks (12 Aug) | 2 wks (27 Aug) | 4 wks (10 Sept) | 6 wks (23 Sept) | 8 wks (7 Oct) | ||

| CHV1-EP713 | 15.5 ± 5.2 | 15.4 ± 5.1 | 16.4 ± 5.0 | 17.7 ± 6.8 | 16.7 ± 5.6 | 1.2 ± 1.8 c |

| CHV1-Δp69 | 13.7 ± 3.5 | 14.3 ± 5.5 | 14.9 ± 4.6 | 14.8 ± 4.5 | 15.8 ± 5.5 | 2.0 ± 2.1 c |

| CHV2-NB58 | 13.9 ± 2.9 | 13.2 ± 1.6 | 14.5 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 2.5 | 14.9 ± 2.2 | 1.1 ± 3.4 c |

| CHV3-GH2a | 16.6 ± 2.8 | 23.0 ± 6.5 | 34.4 ± 6.4 | 50.3 ± 7.0 | 67.5 ± 12.7 | 50.9 ± 11.9 ab |

| MyRV1-9B21 | 17.7 ± 3.6 | 21.6 ± 3.2 | 36.0 ± 9.2 | 42.9 ± 18.8 | 48.0 ± 20.9 | 30.3 ± 21.2 b |

| RnPV6-W113 | 13.6 ± 2.8 | 20.2 ± 4.4 | 34.5 ± 11.2 | 64.4 ± 15.3 | 52.8 ± 9.8 | 50.8 ± 13.0 ab |

| CpMV1-NB631 | 18.5 ± 7.8 | 25.0 ± 5.7 | 32.0 ± 10.6 | 39.9 ± 12.2 | 46.1 ± 14.7 | 27.6 ± 17.1 b |

| Agar | 16.3 ± 3.7 | 22.4 ± 5.4 | 40.0 ± 7.8 | 66.7 ± 16.5 | 80.0 ± 10.4 | 63.7 ± 8.5 a |

Canker area induced by the inoculated fungal strain PC7 at the time point of biological control treatment. Averages and standard deviations calculated from five biological replicates are shown.

Means followed by different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05).

FIG 7.

Chestnut trees surviving and dying of inoculation by PC7. Two representative trees, inoculated with the virulent strain PC7, are shown. The trees were challenged with the CHV1-Δp69-infected fungus (right) or mock-inoculated (agar) (left) and photographed 15 weeks postchallenge inoculation.

It is important to confirm that the aforementioned biocontrol effects resulted from conversion of the PC7 strain from a virulent to a hypovirulent strain by the transmitted virus. To this end, we isolated fungi from four to eight sites of each canker (Fig. 2) and tested them for virus infection. As observed in the in vitro horizontal transmission assay described above, CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, CHV3-GH2a, and CpMV1-NB631 were transmitted within trees more efficiently than others (MyRV1-9B21 and RnPV6-W113) (Table 6). Virus detection rates ranged from 66.7 to 73.3% for MyRV1 and RnPV6 and from 93.3 to 96.7% for the other 5 viruses tested (Table 3).

TABLE 6.

Nuclear genotype and virus detection rate of fungal isolates recovered in the biocontrol assaya

| Virus strain | Inside of the cankers |

Periphery of the cankers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDR | Nuclear genotype |

VDR | Nuclear genotype |

|||||

| PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | PC7 | EP155 | PC7+EP155 | |||

| CHV1-EP713 | 15/16 | 11a | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CHV1-Δp69 | 16/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CHV2-NB58 | 17/17 | 14b | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CHV3-GH2a | 16/16 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 18/18 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| MyRV1-9B21 | 7/16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 12/18 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| RnPV6-W113 | 11/19 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15/19 | 15 | 1 | 3 |

| CpMV1-NB631 | 19/20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 14/14 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Agar | NA | 19 | 0 | 0 | NA | 17 | 0 | 0 |

NA, not applicable; VDR, virus detection rate.

A few fungal isolates were omitted from genotyping experiments.

Nuclear and mitochondrial genotyping of fungal isolates recovered from cankers.

From the perspective of field-level biocontrol of chestnut blight, it is important to know how introduced hypovirulent fungal strains disseminate in treated chestnut forests, particularly when transgenic hypovirulent strains are used. All of the fungal isolates, which were analyzed for virus infection in the virus spread assay, were examined for their nuclear genotype. It should be stated that in the virus spread assay, a maximum of 18 fungal isolates were recovered from a larger area of an active canker relative to that of a hypovirulent canker (Fig. 1). At the time points of fungal reisolation, 3 and 6 weeks after challenge inoculation, virulent cankers were expanding aggressively, while hypovirulent cankers, which were challenged with CHV1-EP713, CHV2-NB58, or CHV1-Δp69, stopped expanding (data not shown). As summarized in Tables 4 and 5, 3 weeks postchallenge inoculation, most of the recovered isolates had the PC7 nuclear genotype, while at this time point all of the viruses moved within cankers, though to different degree (see above). Six weeks after challenge inoculation, both genotypes were observed in a few cultures isolated from cankers challenged with CHV3-GH2a-infected EP155 (Fig. 5C). Also, a single isolate recovered from a canker challenged with CpMV1-NB631-infected EP155 was found to contain both the PC7 and EP155 genotypes.

For biocontrol assay, 2 months after challenge inoculation, fungal isolates were recovered from four bark samples obtained at the periphery of each treated canker. For cankers that were still expanding after biocontrol treatment (i.e., CHV3-GH2a-, CpMV1-NB631-, MyRV1-9B21-, and RnPV6-W113-treated cankers and the agar control), four additional samples were taken from inside the cankers near the treatment holes (Fig. 1). Table 6 summarizes data from 5 trees for each virus-infected fungus. The vast majority of the isolates obtained from the treated cankers had the PC7 genotype and were infected with the respective virus used in the biocontrol assay, indicating overall successful virus transmission from EP155 into the PC7-induced cankers. Isolates with the EP155 genotype or a mixed genotype were observed only in expanding cankers treated with CHV3-GH2a, CpMV1-NB631, and RnPV6-W113.

For mitochondrial haplotyping, we first tried PCR-fragment length polymorphism-based differentiation as reported by Shahi et al. (31). However, EP155 and PC7 showed identical profiles regardless of the PCR primer sets used. Thus, a polymorphic gene for NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5 (36) was sequenced and compared between the two strains. The EP155 NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5 gene sequence was confirmed to be identical to that previously reported by Gobbi et al. (36). PC7 was shown to have a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at map position 22 from the termination codon (A of the initiation codon numbered 1). This SNP (T for EP155 and C for PC7) was utilized for mitochondrial haplotyping of fungal isolates obtained from trees inoculated with EP155 infected by the mitochondrially replicating CpMV1-NB631. We tested fungal isolates obtained from the virus spread assay with the mitochondrially replicating CpMV1-NB631 and those from the biocontrol assay with CHV3-GH2a. Consequently, a total of 68 isolates from the virus spread assay, largely carrying CpMV1-NB631, had the recipient (PC7) mitohaplotype rather than the donor’s (EP155) (Table 4). For the seven isolates from the biocontrol assay, three had the EP155 mitochondrial genotype while four had the PC7 mitohaplotype. Importantly the four isolates with the EP155 mitohaplotype had the EP155 nuclear genotype. Likewise, two isolates with the PC7 mitohaplotype had the PC7 nuclear genotype. The remaining two isolates with the PC7 mitohaplotype had a mixture of both nuclear genotypes. These results suggest that no efficient exchange between the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes occurred in this assay.

DISCUSSION

Biocontrol of chestnut blight involves the dynamic interactions of three organisms: chestnut tree, chestnut blight fungus, and viruses infecting the fungus. Various studies have explored fungal and viral factors governing success or failure in population-level biocontrol and suggested VC type diversity and ecological fitness of virus infected fungi as major determinants (37). Such studies largely involved hypoviruses, especially CHV1-EP713, because the viruses have served as biocontrol agents in some areas of Europe. The characterization of many other viruses infecting C. parasitica in the last few decades prompted the current study. Here, we monitored in-tree behaviors of seven viruses with dsRNA or positive-strand RNA genomes that were harbored in the chestnut blight fungus by assessing their biocontrol potential, horizontal transmission, and spread in chestnut blight cankers. This study highlights different behaviors of the seven viruses and provides interesting insights into biocontrol of chestnut blight. It should be noted that the current study focused on European chestnut, C. sativa, as the host plant, whereas some other studies in the literature have focused on American chestnut, C. dentata, as the host. While differences in blight resistance between these two tree species are not dramatic, they are measurable, with C. dentata being slightly more susceptible to blight than C. sativa (38).

All hypoviruses but CHV3-GH2a showed similar in-tree behavioral profiles, although they induced different symptoms on PDA (Fig. 2). CHV1-EP713, its deletion mutant CHV1-Δp69, and CHV2-NB58 were able to confer a high level of hypovirulence, be horizontally transmitted efficiently, and have high potential as biocontrol agents (Fig. 3 and 6; Tables 3 to 5). CHV1-Δp69 lacks the open reading frame (ORF) coding region encoding the RNA silencing suppressor (32, 39, 40) and basic protein p40. Therefore, this study confirms the previous notion that p29 and p40 are dispensable for hypovirulence induction. Although both viruses can confer hypovirulence to the fungal host, they differ in symptom induction; the wild-type CHV1-EP713 reduces pigmentation and conidiation more than the Δp69 virus. Another difference is the inducibility of the antiviral RNA silencing genes; CHV1-Δp69 activates RNA silencing via transcriptional upregulation, while the wild-type CHV1-EP713 does not (41, 42). In contrast, the CHV3-GH2a isolate in this study was predicted to be a poor performer as a biocontrol agent (Fig. 6), even though it was transmitted efficiently, as were the other hypoviruses (Table 4). The speeds at which these hypoviruses spread in chestnut blight cankers are estimated to be >100 to ∼200 μm/h, which is greater than that of the cell-to-cell movement of plant viruses (∼5 μm/h) (43) and smaller than that of the long-distance movement (∼5 cm/h) (44). Like CHV1-EP713 and unlike CHV1-Δp69 and CHV2-NB58, CHV3-GH2a is unable to upregulate antiviral RNA silencing transcriptionally (45).

The other two viruses spread less efficiently than the hypoviruses: the homologous virus MyRV1-9B21, originally isolated from strain 9B21 of C. parasitica (mean virus detection rate, 70.3%), and the heterologous virus RnPV6-W113, originally isolated from strain W113 of R. necatrix (mean virus detection rate, 75.8%), had substantially lower spreading rates than the aforementioned hypoviruses (mean virus detection rate, over 94%) (Table 4). Given the observation that most fungal isolates from trees had the PC7 genotype (primary inoculum; see below), virus was considered to be transmitted in trees via inter- and intrastrain anastomosis rather than predominant colonization by virus-infected EP155 (secondary inoculum). Although CHV1-EP713 was recently shown to replicate in an annual plant (46), this is unlikely to have occurred in chestnut trees because systemic infection by CHV1-EP713 in plant requires supply of a movement protein from a plant virus. It is unknown why the two viruses moved less efficiently than hypoviruses. It should be noted that while RnPV6-W113 causes severe growth reduction on PDA (Fig. 2), this virus did not reduce fungal virulence much in the trees (Fig. 3; Table 3). CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, and MyRV1-9B21 induce similar symptoms, such as reduced growth of aerial hyphae and enhanced production of brown pigments (Fig. 2). Despite similar symptom induction patterns (Fig. 2), only MyRV1-9B21 spread less efficiently in trees than the others. A property distinguishing the less efficiently moving viruses from efficiently moving viruses is an encapsidated (RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21) or capsidless (hypoviruses) nature.

CpMV1-NB631 is different from all other tested viruses in that it replicates in mitochondria and utilizes mitochondrial translational codes (26, 47). In this sense, it is of great interest to know how mitochondria and its virus CpMV1-NB631 spread in cankers on living chestnut trees. This study clearly showed that CpMV1-NB631 spreads as efficiently as the hypoviruses (Table 4). A previous study showed that CpMV1-NB631 has a relatively narrow host range and is not targeted by RNA silencing (31). The authors of that study also suggested compatibility between the nuclear and mitochondrial genotypes and two modes of transmission: an extra- and intramitochondrial mode, besides colonization of CpMV1-NB631-infected mitochondria in the recipient (31). While studying interspecies and intraspecies transmission of CpMV1-NB631 via protoplast fusion, Shahi et al. (31) showed that only CpMV1-NB631 moved into recipient strains that maintain their original donor mitochondrial haplotypes. Note that in that study, the recipient nuclear genotypes were selected on drug-amended media. In the current study, we could not detect the introduced EP155 mitohaplotype in fungal isolates recovered from treated cankers (Table 4), indicating that CpMV1-NB631 alone could readily transmit to the mitochondria of the primary inoculum PC7. Previous studies showed the presence of mitovirus-derived small RNAs likely generated in the nonmitochondrial cytoplasm (48). Currently, no mitochondrial heteroplasmy was observed. Collectively, these observations favor the idea that CpMV1-NB631 could be transmitted extramitochondrially while not negating the possibility of fusion-based intramitochondrial transmission.

The dissemination and exchange of three genetic elements—viruses, mitochondria, and nuclei—were previously examined at the canker and population levels. Shain and Miller (27) studied within-canker spread of an uncharacterized hypovirulence-inducing virus in an American chestnut (C. dentata) tree. The authors showed that it took 6 weeks for the virus to move from a single challenge inoculation site, at the lower end of a virulent canker, to the top edge of the canker about 10 cm from the challenge site. The current study showed CHV1 and other hypoviruses to move slightly more quickly (100 to ∼200 μm/h) than the unidentified virus reported by Shain and Miller (40 to ∼110 μm/h) (27). In this study, CHV1-EP713 was detected in almost all fungal isolates recovered from the treated virulent cankers 3 weeks after challenge inoculation. An interesting similarity is that the nuclear genotype of the virulent strain, PC7 (primary inoculum) for this study and a methionine-requiring auxotroph (Met−) for the previous study, was dominant in the fungal isolates obtained from the treated cankers in both studies. These results demonstrate not only efficient horizontal transmission of the viruses into treated cankers but also efficient replication and spread within cankers.

At the population level, the three genetic elements disseminated at different speeds during a 2-year biocontrol experiment, in which a CHV1-infected fungal strain was used to treat active cankers induced by resident virulent fungi. Simultaneous transfer of CHV1 and the mitochondrial haplotype into the resident nuclear genotype were observed in almost half of CHV1-infected fungal isolates recovered from treated cankers 1 year postchallenge (28). Although the present study did not investigate the mitochondrial haplotype of isolates obtained from cankers challenged with CHV1-EP713-infected fungi, no transfer of the mitochondrial genome of the introduced strain would be expected from the results with isolates from cankers challenged with the CpMV1-NB631-infected strain (Table 4). In a study by Hoegger et al. (28), almost one-third of the isolates from treated cankers had the same mitochondrial and nuclear genomes as those of the introduced strain, a pattern not observed in the current study. The rest carried the same mitochondrial and nuclear genomes as those of the resident strain, meaning that only CHV1 was transmitted. The nuclear and mitochondrial genotypes of introduced EP155 could seldom be detected and resident ones remained predominant in fungal isolates from cankers treated with fungi infected with CHV1-EP713 or other viruses in the current study. This noticeable difference in detection pattern may be accounted for by the different time scales of the experiments. The nuclear genotype of challenged EP155 could be detected only occasionally in fungal isolates recovered from bark of expanding canker areas of trees challenged with viruses without biocontrol potential (Table 6). It should be noted that CHV3-GH2a infection appeared to facilitate karyon transmission, as observed in the two independent assays with three or five biologic replicates (Tables 4 and 6). Although its mechanism remains largely unknown, it is of interest to speculate about a positive effect of CHV3-GH2a on anastomosis and spread of infected host fungi in tree. Such effects of CHV3-GH2a could also be observed in vitro cultures (N. Suzuki, unpublished data).

Conclusions.

This study suggests that CHV1-EP713, CHV2-NB58, and CHV1-Δp69 are likely more robust as biological control agents than the other viruses tested in this study (Table 7; Fig. 6). MyRV1-9B21 conferred strong hypovirulence to its fungal host strain when tested on apple fruits previously and with live chestnut trees in the current study. Therefore, the failures of the virus in biocontrol against the virulent fungus PC7 appear to be due to their inefficient transmission into PC7 (Table 4). These results allow us to conclude that to serve as robust biocontrol agents, viruses must be able to induce hypovirulence and efficiently spread into chestnut blight cankers (Table 7). Why CpMV1-NB631 has poor biocontrol potential despite its ability to confer hypovirulence and spread efficiently (Table 7; Fig. 6) remains unknown. Discussion of biocontrol agent potential at the field level requires cautious consideration of many factors other than VC type diversity, as discussed earlier (37). For example, CHV1-EP713 considerably reduces not only the virulence but also asexual sporulation of its host fungi, which would affect ecological fitness of infected host fungi at the field level. This point was previously noted by several studies (see reference 37 for a review). While this study did not explore effects of viruses on sporulation, it underlines the importance of horizontal virus transmissibility and in particular virus spread within chestnut blight cankers.

TABLE 7.

Biological properties of the seven viruses infecting C. parasitica

| Virus | Hypovirulence | Efficient spread | Biocontrol |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHV1-EP713 | +++ | Yes | +++ |

| CHV1-Δp69 | +++ | Yes | +++ |

| CHV2-NB58 | +++ | Yes | +++ |

| CpMV1-NB631 | ++ | Yes | + |

| MyRV1-9B21 | +++ | No | + |

| RnPV6-W113 | (+) | No | No |

| CHV3-GH2a | No | Yes | No |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral and fungal strains.

Fungal and viral strains used in the current study are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A total of seven RNA viruses were tested: RnPV6-W113 (22), MyRV1-9B21 (30, 49), CHV1-EP713 (50), CHV1-Δp69 (32), CHV2-NB58 (51), CpMV1-NB631 (26), and CHV3-GH2a, a derivative of CHV3-GH2 (29). Note that these viruses are diverse molecularly and biologically. Even the hypoviruses are different from each other in many properties, including their origins, effects on fungal phenotype, and ability to confer hypovirulence (19), as well as their induction of antiviral silencing genes (45). Another noteworthy point is that CHV3-GH2a, derived during subculturing of the infected fungus by the original CHV3-GH2, lacked the defective RNA termed RNA2 but retained two satellite RNAs (RNA3 and RNA4), while the original contains all three subviral RNAs (52). Two strains of C. parasitica, PC7 (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research [WSL] fungal collection accession number M1334) originally isolated in 1993 from Bergamo, Italy (53), and EP155 (ATCC 38755), originally isolated in 1977 from Bethany, Connecticut, USA, both belonging to the EU5 VC group, were used as virulent strains (54, 55). These two strains are readily distinguishable by microsatellite markers as described below.

Virus inoculation and horizontal and vertical transmission.

Many viruses from Cryphonectria spp. and other fungi could be experimentally introduced into the standard EP155 genetic background using several previously developed methods. Different methods were used depending primarily on whether the viruses of interest form virus particles and whether infectious RNAs or DNAs are available for them. CHV1-Δp69 was introduced into strain EP155 by spheroplast transformation with the infectious cDNA clone pCPXHY-CHV1-Δp69 (56) or in vitro-synthesized RNA derived from pRFL4 (57). EP155 infected with capsidless CHV2-NB58, CHV3-GH2a, and CpMV1-NB631 was previously obtained by protoplast fusion (31, 45). The remaining encapsidated viruses, RnPV6-W113 and MyRV1-9B21, were transfected into EP155 earlier (22, 30). Horizontal viral transmission was examined by coculture of virus donor and recipient fungal strains on a PDA plate (9 cm in diameter) as described previously (56).

Inoculation of chestnut trees with fungal strains.

Three-year-old chestnut trees (C. sativa; provenance, Maggiatal, Switzerland), approximately 2.5 m high, and approximately 2.5 cm wide (diameter), were purchased from a Swiss nursery and grown outside for a few months from April to July 2019. They were moved to a biosafety level 3 (BSL3), temperature-controlled greenhouse (25°C) greenhouse at WSL and acclimated to the greenhouse environment for a week. These trees were used in three different assays (I, II, and III) (Fig. 2). All inoculations were done using mycelial plugs from actively growing cultures as described by Dennert et al. (58). For assay I (to investigate virulence), strain EP155 infected by different viruses was inoculated into the chestnut trees. Three biological replicates were used for each virus-infected strain and for a virus-free control. For assay II (to examine in-tree spread of different viruses), two trees each were singly inoculated with the virulent strain PC7 in two consecutive experiments. For assay III (to estimate biocontrol potential), five trees were singly inoculated with PC7. Two weeks following these primary inoculations with PC7, challenge inoculations were made with the virus-infected EP155 strains (Fig. 2). For assay II, a single inoculation at the lower end of each virulent canker was made. For assay III, eight inoculations regularly distributed along the periphery of a virulent canker were carried out. After inoculation, the holes were sealed with LacBalsam (Frunol Delicia, Delitzsch, Germany) to prevent desiccation. At the time of challenge inoculation in assays II and III, the typical canker size was approximately 43 mm by 21 mm. The length and width of the treated cankers were measured biweekly, and the canker area was calculated using the formula for an ellipse. The degree of canker expansion after the biocontrol treatments was used to assess the biocontrol effects of the different mycoviruses. A linear model with Scheffe’s post hoc test (calculated using DataDesk 6.3; DataDescription, Inc., Ithaca, NY) was applied to test for significant differences in mean canker expansion between viruses.

Fungal isolation from cankers on chestnut trees.

All cankers were sampled at the end of the experiment to verify virus infection and fungal identity (Fig. 1). For assay I, three bark samples (top, middle, and bottom of the canker) were taken from each canker using a bone marrow biopsy needle (diameter, 2 mm; Jamshidi 11 gauge; BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). For assay II, four bark samples at the periphery of each canker were taken 2 months after the challenge inoculations. For expanding cankers, four additional samples were taken from inside the cankers between the four biocontrol inoculation holes. For assay III, two cankers were sampled for each virus 3 and 6 weeks after the biocontrol inoculations. At each time point, six bark samples were taken along three rows from the lower to the upper end of the cankers, resulting in 18 samples per canker (Fig. 1). Bark plugs were surface sterilized using 70% ethanol and placed on water agar plates containing streptomycin at a concentration of 40 mg/liter. Outgrowing mycelia were transferred on potato dextrose agar (PDA; 39 g/liter; BD Difco) plates, which were then incubated at room temperature in the dark for 10 to 14 days. Under this condition, cultures infected with CHV1-EP713, CHV1-Δp69, CHV2-NB58, MyRV1-9B21, and RnPV6-W113 developed a virus-specific culture morphology that was used as an indicator for virus infection (Fig. 2). Results based on culture morphology were confirmed for subsamples by virus-specific RT-PCR as described below. The presence of CHV3-GH2a and CpMV1-NB631 was exclusively verified by RT-PCR, as these two viruses did not induce a specific cultural phenotype in infected fungal strains (see Fig. 4 for some examples).

DNA extraction, RT-PCR, and nuclear and mitochondrial genotyping.

The simplified and reliable one-step RT-PCR technique developed by Urayama et al. (59) for virus detection in Magnaporthe oryzae without nucleic acid extraction was employed to detect virus in fungal isolates obtained from cankers. The method entails stabbing the freshly growing region of mycelial colony on PDA with a toothpick and dipping the toothpick into a 10-μl premixed RT-PCR mixture prepared according to the protocol for PrimeScript One Step RT-PCR version 2 (Dye Plus) (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan). Importantly, this technique was found to be applicable to C. parasitica and viruses (59, 60). The PCR was programmed as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. The sequences of primers for detection of respective viruses are available upon request.

For nuclear genotyping, DNA was extracted from lyophilized fungal mycelium using the KingFisher 96 Flex system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The multiplex PCR 3 described by Prospero and Rigling (61) was used to distinguish PC7 and EP155. In this PCR, strain PC7 yields a 130-bp DNA fragment at microsatellite locus CPE1 and a 252-bp fragment at locus CPE5. The corresponding DNA fragments in strain EP155 are 148 bp and 260 bp long.

Mitochondrial genotyping or mito-haplotyping was based on a single nucleotide polymorphism detected in the coding region of NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5. This region was amplified using the primers MtF2 and MtR2 (sequences available upon request) and the PCR fragments were sequenced by the Sanger method.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by Yomogi Inc., Joint Usage/Research Center, Institute of Plant Science and Resources, Okayama University (to C.C.), the Ohara Foundation for Agriculture Research (to N.S.), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (KAKENHI 17H01463, 15K14663, 16H06436, 16H06429, and 16K21723 to N.S.), and the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station and USDA-NIFA (to B.I.H.). N.S. was a recipient of the WSL Fellowship from June 2019 to November 2019. A.A. and S.S. are MEXT scholars.

We are grateful to Donald L. Nuss for generous gifts of the C. parasitica standard strain EP155 and the prototype hypovirus, CHV1-EP713. We are grateful to Helene Blauenstein, Cygni Armbruster, and Sven Ulrich for their technical assistance.

N.S. and D.R. designed research; N.S., C.C., A.A., S.S., and D.R. performed research; N.S., B.I.H., and D.R. analyzed data; N.S., D.R., and B.I.H. wrote the manuscript.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the late Helene Blauenstein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostakis SL. 1982. Biological control of chestnut blight. Science 215:466–471. doi: 10.1126/science.215.4532.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiniger U, Rigling D. 1994. Biological control of chestnut blight in Europe. Annu Rev Phytopathol 32:581–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.32.090194.003053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigling D, Prospero S. 2018. Cryphonectria parasitica, the causal agent of chestnut blight: invasion history, population biology and disease control. Mol Plant Pathol 19:7–20. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuss DL. 1992. Biological control of chestnut blight: an example of virus-mediated attenuation of fungal pathogenesis. Microbiol Rev 56:561–576. doi: 10.1128/MR.56.4.561-576.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anagnostakis SL, Chen BS, Geletka LM, Nuss DL. 1998. Hypovirus transmission to ascospore progeny by field-released transgenic hypovirulent strains of Cryphonectria parasitica. Phytopathology 88:598–604. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.7.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milgroom MG, Cortesi P. 1999. Analysis of population structure of the chestnut blight fungus based on vegetative incompatibility genotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:10518–10523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi GH, Dawe AL, Churbanov A, Smith ML, Milgroom MG, Nuss DL. 2012. Molecular characterization of vegetative incompatibility genes that restrict hypovirus transmission in the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. Genetics 190:113–127. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.133983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang DX, Spiering MJ, Dawe AL, Nuss DL. 2014. Vegetative incompatibility loci with dedicated roles in allorecognition restrict mycovirus transmission in chestnut blight fungus. Genetics 197:701–714. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.164574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short DP, Double M, Nuss DL, Stauder CM, MacDonald W, Kasson MT. 2015. Multilocus PCR assays elucidate vegetative incompatibility gene profiles of Cryphonectria parasitica in the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5736–5742. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00926-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornejo C, Sever B, Kupper Q, Prospero S, Rigling D. 2019. A multiplexed genotyping assay to determine vegetative incompatibility and mating type in Cryphonectria parasitica. Eur J Plant Pathol 155:377–379. doi: 10.1007/s10658-019-01773-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang DX, Nuss DL. 2016. Engineering super mycovirus donor strains of chestnut blight fungus by systematic disruption of multilocus vic genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:2062–2067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522219113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacDonald WL, Fulbright DW. 1991. Biological-control of chestnut blight-use and limitations of transmissible hypovirulence. Plant Dis 75:653–661. doi: 10.1094/PD-75-053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Double ML, Jarosz AM, Fulbright DW, Baines AD, MacDonald WL. 2018. Evaluation of two decades of Cryphonectria parasitica hypovirus introduction in an American chestnut stand in Wisconsin. Phytopathology 108:702–710. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-10-17-0354-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enebak SA, Macdonald WL, Hillman BI. 1994. Effect of dsRNA associated with isolates of Cryphonectria parasitica from the central Appalachians and their relatedness to other dsRNA from North America and Europe. Phytopathology 84:528–534. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung PH, Bedker PJ, Hillman BI. 1994. Diversity of Cryphonectria parasitica hypovirulence-associated double-stranded RNAs within a chestnut population in New Jersey. Phytopathology 84:984–990. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peever TL, Liu YC, Milgroom MG. 1997. Diversity of hypoviruses and other double-stranded RNAs in Cryphonectria parasitica in North America. Phytopathology 87:1026–1033. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1997.87.10.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eusebio-Cope A, Sun L, Tanaka T, Chiba S, Kasahara S, Suzuki N. 2015. The chestnut blight fungus for studies on virus/host and virus/virus interactions: from a natural to a model host. Virology 477:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nuss DL. 2005. Hypovirulence: mycoviruses at the fungal-plant interface. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:632–642. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillman BI, Suzuki N. 2004. Viruses of the chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica. Adv Virus Res 63:423–472. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(04)63007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiba S, Lin YH, Kondo H, Kanematsu S, Suzuki N. 2013. Effects of defective-interfering RNA on symptom induction by, and replication of a novel partitivirus from a phytopathogenic fungus Rosellinia necatrix. J Virol 87:2330–2341. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02835-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiba S, Lin YH, Kondo H, Kanematsu S, Suzuki N. 2013. A novel victorivirus from a phytopathogenic fungus, Rosellinia necatrix is infectious as particles and targeted by RNA silencing. J Virol 87:6727–6738. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00557-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiba S, Lin YH, Kondo H, Kanematsu S, Suzuki N. 2016. A novel betapartitivirus RnPV6 from Rosellinia necatrix tolerates host RNA silencing but is interfered by its defective RNAs. Virus Res 219:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salaipeth L, Chiba S, Eusebio-Cope A, Kanematsu S, Suzuki N. 2014. Biological properties and expression strategy of Rosellinia necatrix megabirnavirus 1 analyzed in an experimental host, Cryphonectria parasitica. J Gen Virol 95:740–750. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.058164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanematsu S, Sasaki A, Onoue M, Oikawa Y, Ito T. 2010. Extending the fungal host range of a partitivirus and a mycoreovirus from Rosellinia necatrix by inoculation of protoplasts with virus particles. Phytopathology 100:922–930. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-100-9-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koonin EV, Dolja VV, Krupovic M, Varsani A, Wolf YI, Yutin N, Zerbini FM, Kuhn JH. 2020. Global organization and proposed megataxonomy of the virus world. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 84:e00061-19. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00061-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polashock JJ, Hillman BI. 1994. A small mitochondrial double-stranded (ds) RNA element associated with a hypovirulent strain of the chestnut blight fungus and ancestrally related to yeast cytoplasmic T and W dsRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:8680–8684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shain H, Miller JB. 1992. Movement of cytopasmic hypovirulence agents in chestnut blight cankers. Can J Bot 70:557–561. doi: 10.1139/b92-070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoegger PJ, Heiniger U, Holdenrieder O, Rigling D. 2003. Differential transfer and dissemination of hypovirus and nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of a hypovirus-infected Cryphonectria parasitica strain after introduction into a natural population. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:3767–3771. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.7.3767-3771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smart CD, Yuan W, Foglia R, Nuss DL, Fulbright DW, Hillman BI. 1999. Cryphonectria hypovirus 3, a virus species in the family hypoviridae with a single open reading frame. Virology 265:66–73. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hillman BI, Supyani S, Kondo H, Suzuki N. 2004. A reovirus of the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica that is infectious as particles and related to the Coltivirus genus of animal pathogens. J Virol 78:892–898. doi: 10.1128/jvi.78.2.892-898.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahi S, Eusebio-Cope A, Kondo H, Hillman BI, Suzuki N. 2019. Investigation of host range of and host defense against a mitochondrially replicating mitovirus. J Virol 93:e01503-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01503-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki N, Nuss DL. 2002. Contribution of protein p40 to hypovirus-mediated modulation of fungal host phenotype and viral RNA accumulation. J Virol 76:7747–7759. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.15.7747-7759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fulbright DW, Weidlich WH, Haufler KZ, Thomas CS, Paul CP. 1983. Chestnut blight and recovering American chestnut trees in Michigan. Can J Bot 61:3164–3171. doi: 10.1139/b83-354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fulbright DW. 1984. Effect of eliminating dsRNA in hypovirulent Endothia parasitica. Phytopathology 74:722–724. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-74-722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan W, Hillman BI. 2001. In vitro translational analysis of genomic, defective, and satellite RNAs of Cryphonectria hypovirus 3-GH2. Virology 281:117–123. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gobbi E, Firrao G, Carpanelli A, Locci R, Van Alfen NK. 2003. Mapping and characterization of polymorphism in mtDNA of Cryphonectria parasitica: evidence of the presence of an optional intron. Fungal Genet Biol 40:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Milgroom MG, Cortesi P. 2004. Biological control of chestnut blight with hypovirulence: a critical analysis. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42:311–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graves AH. 1950. Relative blight resistance in species and hybrids of Castanea. Phytopathology 40:1125–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segers GC, van Wezel R, Zhang X, Hong Y, Nuss DL. 2006. Hypovirus papain-like protease p29 suppresses RNA silencing in the natural fungal host and in a heterologous plant system. Eukaryot Cell 5:896–904. doi: 10.1128/EC.00373-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki N, Maruyama K, Moriyama M, Nuss DL. 2003. Hypovirus papain-like protease p29 functions in trans to enhance viral double-stranded RNA accumulation and vertical transmission. J Virol 77:11697–11707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.21.11697-11707.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun Q, Choi GH, Nuss DL. 2009. A single Argonaute gene is required for induction of RNA silencing antiviral defense and promotes viral RNA recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17927–17932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907552106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiba S, Suzuki N. 2015. Highly activated RNA silencing via strong induction of dicer by one virus can interfere with the replication of an unrelated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E4911–E4918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509151112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyashita S, Kishino H. 2010. Estimation of the size of genetic bottlenecks in cell-to-cell movement of soil-borne wheat mosaic virus and the possible role of the bottlenecks in speeding up selection of variations in trans-acting genes or elements. J Virol 84:1828–1837. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01890-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carrington JC, Kasschau KD, Mahajan SK, Schaad MC. 1996. Cell-to-cell and long-distance transport of viruses in plants. Plant Cell 8:1669–1681. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aulia A, Tabara M, Telengech P, Fukuhara T, Suzuki N. 2020. Dicer monitoring in a model filamentous fungus host, Cryphonectria parasitica. Curr Res Virol Sci 1:100001. doi: 10.1016/j.crviro.2020.100001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bian R, Andika IB, Pang T, Lian Z, Wei S, Niu E, Wu Y, Kondo H, Liu X, Sun L. 2020. Facilitative and synergistic interactions between fungal and plant viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117:3779–3788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915996117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hillman BI, Cai G. 2013. The family Narnaviridae: simplest of RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res 86:149–176. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394315-6.00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vainio EJ, Jurvansuu J, Streng J, Rajamaki ML, Hantula J, Valkonen JPT. 2015. Diagnosis and discovery of fungal viruses using deep sequencing of small RNAs. J Gen Virol 96:714–725. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki N, Supyani S, Maruyama K, Hillman BI. 2004. Complete genome sequence of Mycoreovirus-1/Cp9B21, a member of a novel genus within the family Reoviridae, isolated from the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. J Gen Virol 85:3437–3448. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shapira R, Choi GH, Nuss DL. 1991. Virus-like genetic organization and expression strategy for a double-stranded RNA genetic element associated with biological control of chestnut blight. EMBO J 10:731–739. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hillman BI, Halpern BT, Brown MP. 1994. A viral dsRNA element of the chestnut blight fungus with a distinct genetic organization. Virology 201:241–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hillman BI, Foglia R, Yuan W. 2000. Satellite and defective RNAs of Cryphonectria hypovirus 3-grand haven 2, a virus species in the family Hypoviridae with a single open reading frame. Virology 276:181–189. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortesi P, Rigling D, Heiniger U. 1998. Comparison of vegetative compatibility types in Italian and Swiss subpopulations of Cryphonectria parasitica. Forest Pathol 28:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.1998.tb01247.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anagnostakis SL, Day PR. 1979. Hypovirulence conversion in Endothia parasitica. Phytopathology 69:1226–1229. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-69-1226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crouch JA, Dawe A, Aerts A, Barry K, Churchill ACL, Grimwood J, Hillman BI, Milgroom MG, Pangilinan J, Smith M, Salamov A, Schmutz J, Yadav JS, Grigoriev IV, Nuss DL. 2020. Genome sequence of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica EP155: a fundamental resource for an archetypical invasive plant pathogen. Phytopathology 110:1180–1188. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-19-0478-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andika IB, Jamal A, Kondo H, Suzuki N. 2017. SAGA complex mediates the transcriptional up-regulation of antiviral RNA silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:E3499–E3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701196114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suzuki N, Chen B, Nuss DL. 1999. Mapping of a hypovirus p29 protease symptom determinant domain with sequence similarity to potyvirus HC-Pro protease. J Virol 73:9478–9484. doi: 10.1128/JVI.73.11.9478-9484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dennert F, Meyer JB, Rigling D, Prospero S. 2019. Assessing the phytosanitary risk posed by an intraspecific invasion of Cryphonectria parasitica in Europe. Phytopathology 109:2055–2063. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-19-0197-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urayama S, Katoh Y, Fukuhara T, Arie T, Moriyama H, Teraoka T. 2015. Rapid detection of Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1-A from fungal colonies on agar plates and lesions of rice blast. J Gen Plant Pathol 81:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s10327-014-0567-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aulia A, Andika IB, Kondo H, Hillman BI, Suzuki N. 2019. A symptomless hypovirus, CHV4, facilitates stable infection of the chestnut blight fungus by a coinfecting reovirus likely through suppression of antiviral RNA silencing. Virology 533:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prospero S, Rigling D. 2012. Invasion genetics of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica in Switzerland. Phytopathology 102:73–82. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-11-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Choi GH, Nuss DL. 1992. Hypovirulence of chestnut blight fungus conferred by an infectious viral cDNA. Science 257:800–803. doi: 10.1126/science.1496400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]