Abstract

Cardiac MRI (CMR) has rich potential for future cardiovascular screening even though not approved clinically for routine screening for cardiovascular disease among patients with increased cardiometabolic risk. Patients with increased cardiometabolic risk include those with abnormal blood pressure, body mass, cholesterol level, or fasting glucose level, which may be related to dietary and exercise habits. However, CMR does accurately evaluate cardiac structure and function. CMR allows for effective tissue characterization with a variety of sequences that provide unique insights as to fibrosis, infiltration, inflammation, edema, presence of fat, strain, and other potential pathologic features that influence future cardiovascular risk. Ongoing epidemiologic and clinical research may demonstrate clinical benefit leading to increased future use.

© RSNA, 2021

Summary

Cardiac MRI has research applications to screen for manifestations of cardiovascular disease among patients with increased cardiometabolic risk, as well as potential future roles for established and emerging MRI sequences.

Essentials

■ Current guidelines do not endorse any role for cardiac MRI (CMR) as a screening test for cardiovascular disease, even among patients with increased cardiometabolic risk.

■ Patients with increased cardiometabolic risk have increased prevalence of subclinical ischemia and infarction that may be detected by MRI, although identification has not demonstrated a clinical outcomes benefit.

■ Future potential for CMR evaluation of patients at increased cardiometabolic risk may include spectroscopy, strain, and tissue characterization by mapping techniques.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in the world (1–3). Atherosclerotic CVD is a chronic disease process due to systemic derangements that begin early in life. Major metabolic drivers include adiposity, inadequate physical activity, diet, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and dysglycemia (4). Studies assessing how metabolic risk factors raise the lifetime risk of CVD led to the development of the terms metabolic syndrome (5), cardiometabolic syndrome (6), or simply cardiometabolic risk (7). The term metabolic syndrome has varied definitions but most commonly cited is that of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III from 2001, whose classification relied on patients possessing three or more of the five following risk factors: waist circumference greater than 102 cm (40 in) in men or greater than 88 cm (35 in) in women, hypertension (≥ 130/85 mm Hg), low high-density lipoprotein level (< 40 mg/dL in men or < 50 in women), raised triglyceride level (> 150 mg/dL), and impaired fasting glucose level (≥ 110 mg/dL). Other definitions have included measures of insulin resistance or microalbuminuria (5). More generally, the term cardiometabolic risk that we use herein refers to patients with increased lifetime risk of developing clinical CVD due to nonideal control of the above metabolic risk factors (8).

Although there is currently no evidence-based role for routine screening MRI to identify subclinical CVD among patients at increased cardiometabolic risk, contemporary epidemiologic researchers are investigating techniques that physicians and other health care professionals may use to detect and intervene earlier in the pathway of primary versus secondary prevention. Although as yet unproven, earlier intervention to prevent adverse clinical events could reduce the burden of myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, premature death, and heart failure, which are all end-stage clinical manifestations of this cardiometabolic-based chronic disease (4).

Cardiac MRI (CMR) has proven to be a useful tool for assessing patients who are at risk for the development of cardiometabolic diseases. As a historical reference as to the potential for CMR to provide early diagnosis and intervention, screening T2* with CMR provided a breakthrough technology to significantly reduce mortality among patients with thalassemia screened for iron overload (9). Screening CMR also adds important incremental prognostic value by detecting late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) among patients with a variety of cardiomyopathies (10). In a similar manner, CMR could in the near future provide a role to enhance prognostic evaluation among patients with increased cardiometabolic risk, although at present day this requires further validation as to whom to screen, what the incremental prognostic value is, and whether it improves outcomes in a cost-effective manner.

Our purpose is to review the theoretical background, current evidence basis, and future potential for CMR as a screening test for patients with increased cardiometabolic risk. Although emerging literature has identified a screening CMR research potential for aortic disease, carotid disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other extracardiac diseases, for clarity and space limitations we shall focus the current review on cardiac-specific MRI.

Mechanisms of Structural Tissue Changes in Cardiometabolic Diseases

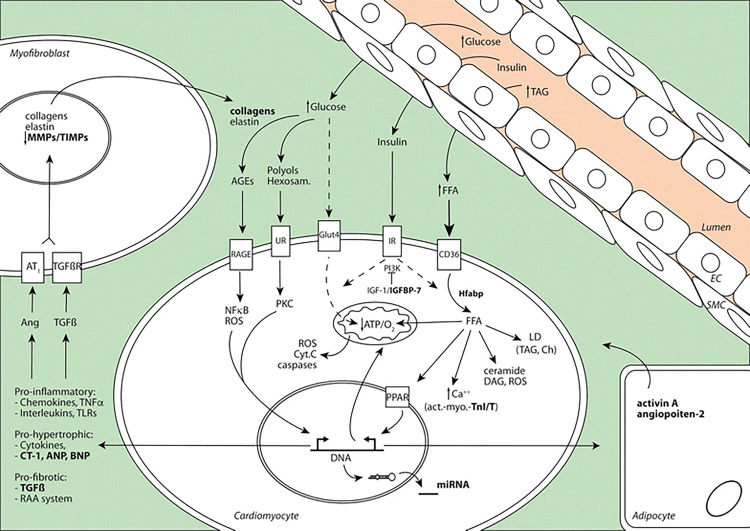

To begin, we provide an overview of cardiac structural changes that occur during the course of cardiometabolic diseases as a framework for understanding how imaging can be used to assess these changes. An underrecognized comorbid sequela of long-standing diabetes can be the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy, which is estimated to affect approximately 12% of patients with diabetes (11). Diabetic cardiomyopathy can be defined as ventricular dysfunction observed in patients with diabetes independent of coronary artery disease (CAD), valve disease, or hypertension (12). The pathophysiologic mechanism of diabetic cardiomyopathy is multifactorial. Atherosclerosis, subclinical microinfarctions, mitochondrial dysfunction, and lipotoxicity may contribute to the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Long-standing hyperglycemia (Fig 1) impairs healthy cardiomyocyte metabolism and results in the deposition of toxic advanced glycation end products (13), which are pro-oxidant and induce inflammation by chemokines, TNFα, toll-like receptors, and interleukins, which results in the development of fibrosis.

Figure 1:

Cardiomyocyte in patients with diabetes. High levels of blood glucose and fatty acid, combined with insulin resistance, activate different cellular mechanisms in the myocardium. Glucose cannot be assimilated by the cardiomyocyte and form glucose metabolites such as advanced glycation products, polyols, and hexosamine, which activate pro-oxidant and proinflammatory pathways. Myocardial energy relies on free fatty acids, which are taken up and accumulated as toxic products such as triacylglycerols, leading to steatosis. These stimuli promote expression of prohypertrophic and profibrotic factors that lead to cardiac dysfunction. AGE = advanced glycation product, EC = endothelial cell, PPARs = peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, RAA = renin-angiotensin-aldosterone, RAGE = receptor for advanced glycation end products, SMC = smooth muscle cell, TIMP = tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 11.)

Fibrosis is caused by the upregulation of collagen, elastin, and matrix metalloproteinases within the myofibroblast and ultimately leads to myocardial stiffness (14). The cardiomyocyte increasingly relies on free fatty acids as an energy source in the chronic hyperglycemic state, which increases toxic byproducts such as triacylglycerols that promote steatosis. The net result of these deleterious cardiometabolic changes contributes to left and right ventricular diastolic dysfunction, reduced left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF), LV hypertrophy, and interstitial fibrosis (15). Diabetic cardiomyopathy can also manifest as contractile dysfunction during exercise (16,17). These structural abnormalities may evolve quiescently but could be detected via a variety of imaging techniques prior to a more advanced disease stage manifesting clinically.

Screening for Cardiometabolic Risk: Shortcomings of Other Modalities

Prior to discussing the potential for CMR evaluation of patients with increased cardiometabolic risk, we will discuss in brief the success and shortcomings of screening via other technologies.

Radionuclide Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

One of the landmark modern studies that sought to use imaging to screen for CVD among patients at increased cardiovascular risk was the Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics (DIAD) study published in 2009 (18). DIAD was a randomized controlled trial with more than 1100 asymptomatic participants with type II diabetes who were randomly assigned to either adenosine-stress radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging or no screening. In this study, the overall cardiac event rate in asymptomatic patients was low (2.9% over 5 years). Despite the identification of a significant prevalence of subclinical myocardial ischemia, adverse cardiac events were not significantly reduced by screening with nuclear imaging at 5-year follow-up. That being said, the patients with prognostically normal studies had lower cardiac event rates than the patients with moderate or large perfusion defects (18). Thus, stress myocardial perfusion imaging is not currently recommended routinely for patients with increased cardiometabolic risk, such as those with diabetes, as testing has not been demonstrated to improve outcomes.

Cardiac CT Angiography

Similarly, screening CT angiography of patients with diabetes identifies subclinical atherosclerosis by coronary artery calcium or CT angiography and even a small prevalence of asymptomatic patients with diabetes mellitus who have obstructive CAD, but this detailed screening has not demonstrated an outcomes benefit. The Screening For Asymptomatic Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Among High-Risk Diabetic Patients Using CT Angiography, Following Core 64 (faCTor-64) trial used cardiac CT angiography to screen 900 asymptomatic patients with diabetes mellitus and included primary outcomes of a composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization. Patients were followed for 4 years, and there were no outcome differences between patients screened with cardiac CT angiography versus standard therapy (19). What is notable for both the DIAD and faCTor-64 studies is the low event rate, which may have left both studies underpowered but also draws into question the added value of screening a general population with overall low disease incidence when well treated at baseline with respect to preventive therapies.

Carotid US and Cardiac CT Angiography

In 2016, Rassi et al (20) screened 98 patients with diabetes for subclinical CAD via carotid US, coronary artery calcium score, exercise treadmill testing, and cardiac CT angiography. When compared with cardiac CT angiography, coronary artery calcium was found to be the most accurate screening modality for detection of CAD, while exercise treadmill testing and carotid US were less sensitive and specific. While this study evaluated the modality that most accurately diagnosed subclinical CAD, it did not evaluate for any hard cardiovascular endpoints (20).

CMR Applications for Assessing Cardiometabolic Diseases

Given that cardiometabolic diseases can impact tissues in a variety of ways, a question remains of which CMR techniques may offer the highest potential benefit for screening patients who are at an elevated cardiometabolic risk. While echocardiography is commonly used to evaluate for presence of cardiac dysfunction, MRI may prove a helpful tool in the detection of abnormal myocardial remodeling and function, tissue characterization, and metabolism to risk stratify patients with diabetes and detect and diagnose cardiac effects of diabetes early in the disease process (11). We outline here some applications for CMR in assessing cardiometabolic diseases.

CMR Evaluation for Patients with Increased Cardiometabolic Risk

When compared with echocardiography, CMR has greater accuracy and reliability to assess chamber size, LVEF, and distribution of myocardial mass. For example, in a study of 20 healthy individuals and 20 with heart failure, Bellinger et al noted that the standard deviation for end-diastolic volume, end-systolic volume, and ejection fraction for CMR was just 4.0 mL, 2.8 mL, and 1.8%, respectively (21). By comparison, images acquired for two-dimensional echocardiography may be limited by patients’ body habitus, could be acquired in foreshortened views, and lack accuracy and precision due to geometric assumptions.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing two-dimensional echocardiography to CMR, Pickett et al reported the limits of agreement for LVEF were wide at −13% to 12% (22). While other modalities such as SPECT and CT had good correlation with LVEF by CMR, two-dimensional echocardiography had significantly lower agreement and only modest correlation (r = 0.660). Clinicians may in part overcome these technical limitations of echocardiography through use of contrast material–enhanced echocardiography or three-dimensional echocardiography, but these techniques require either a more expensive, dedicated three-dimensional probe or, for contrast-enhanced echocardiography, intravenous cannulation, contrast agent administration, and additional time. Thus, three-dimensional or contrast-enhanced echocardiography are not universally performed.

Classification as healthy versus impaired systolic function, as well as allocations of certain medications (such as for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) and devices (such as defibrillators), entirely relies on evaluation of LV size and systolic function. A study by Joshi et al consisting of 52 patients with heart failure concluded that CMR versus echocardiography would reclassify 21% of the patients as to whether defibrillator implantation was recommended. CMR also detected LV thrombus in 10% of patients in whom it was not identified by two-dimensional echocardiography (23).

Extracellular Volume Measurements

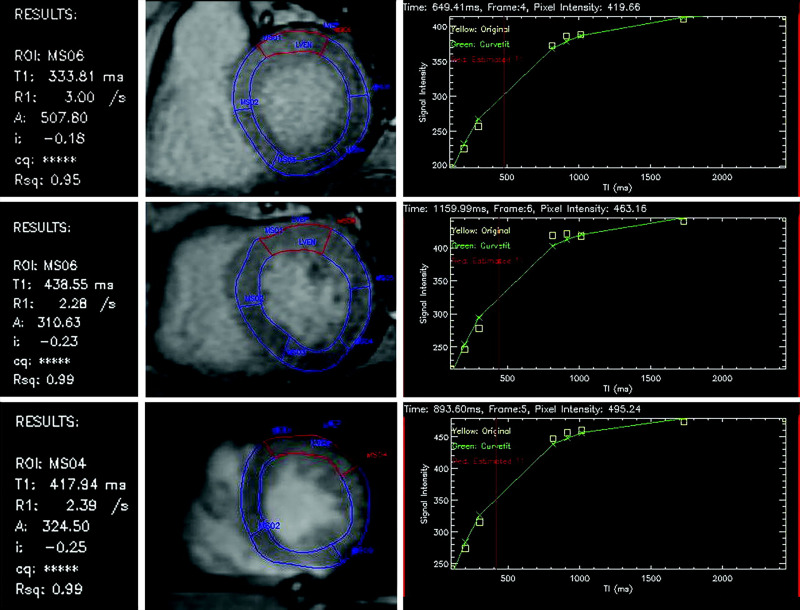

Tissue characterization has been employed using LGE to identify subclinical infarcts (24). More recently, when T1 mapping and/or evaluation of extracellular volume is used, parametric mapping (Fig 2) can identify and quantify diffuse expansion of the extracellular matrix without biopsy, such as due to nonspecific fibrosis in patients with diabetes, which can be a precursor to diabetic cardiomyopathy (25).

Figure 2:

Postcontrast T1 maps of the basal, midcavity, and apical left ventricle in short-axis view of the anterior segment (highlighted in red). An exponential recovery curve of signal intensities at different inversion times (T1) is produced to determine a postcontrast myocardial T1 value for the anterior segment: basal 476 msec, midcavity 439 msec, and apical 418 msec. This can be repeated before and after contrast enhancement for all 16 segments to determine the mean T1 value to quantify the degree of myocardial fibrosis. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 26.) ROI = region of interest.

Kammerlander et al (26) compared T1 mapping to histologic findings from LV biopsies to assess extracellular volume expansion. A total of 473 patients without known infiltrative disorder and with mostly preserved LVEF underwent T1-mapping CMR, and 36 underwent LV biopsy with 1-year clinical outcomes follow-up for hospitalization for cardiovascular reasons (heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, and cerebral vascular accident) or cardiac death. CMR extracellular volume correlated modestly with LV biopsy extracellular volume (r = 0.493, P = .002).

MI and Myocardial Fibrosis

Several studies (26–29) used pre–contrast-enhanced (native) T1 mapping to detect MI and myocardial fibrosis. Kali et al (27) evaluated if native T1 maps could characterize chronic MIs in patients with prior ST-elevation MIs (STEMIs) or non-STEMIs. Native T1 maps were compared with a reference standard of LGE CMR. There was no difference in infarct size and transmurality with native T1 mapping versus LGE. The median infarct-to–remote myocardium contrast-to-noise ratio was 2.5-fold higher for LGE images relative to T1 maps. The sensitivity and specificity of T1 maps using software-based thresholds were 89% and 98%, respectively (STEMI) and 87% and 95%, respectively (non-STEMI). For visual detection, sensitivity and specificity of T1 maps were 60% and 86%, respectively (STEMI) and 64% and 91%, respectively (non-STEMI).

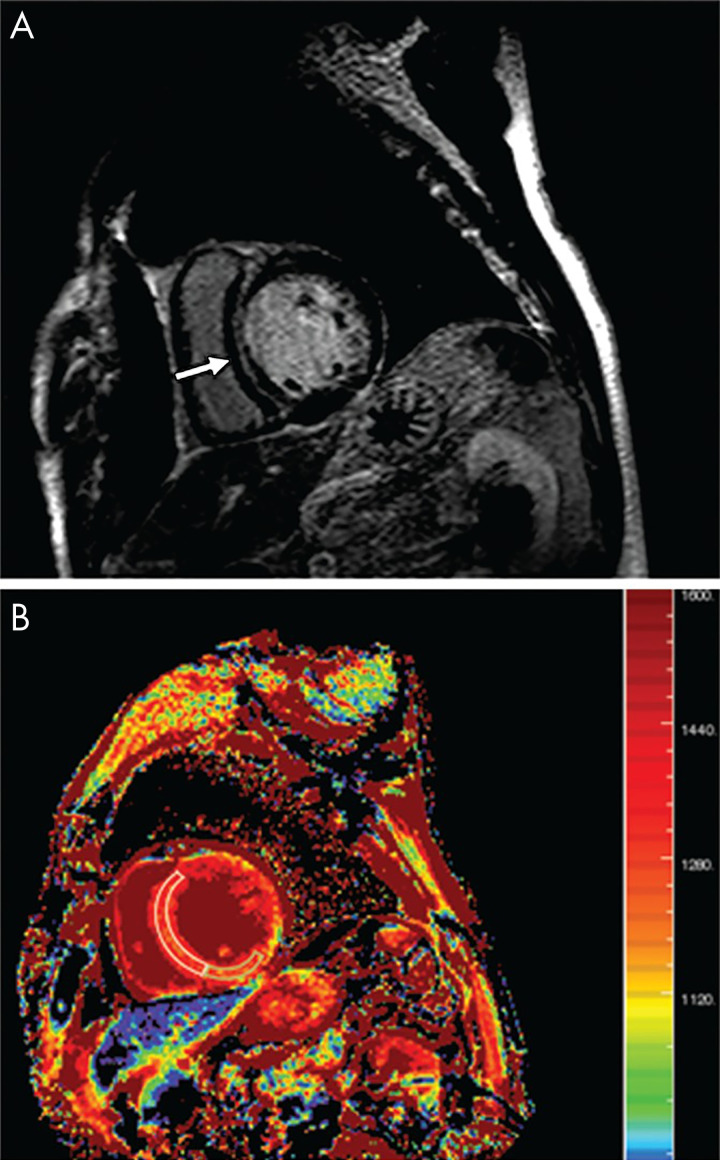

Yanagisawa et al evaluated myocardial fibrosis in patients with dilated nonischemic cardiomyopathy (Fig 3) using T1 mapping versus the presence of LGE (29). This was a small study with 25 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy versus 15 healthy individuals. All patients underwent non–contrast-enhanced T1 mapping; however, the healthy individuals did not receive LGE evaluation. Basal and midventricular levels were divided into eight segments, and the T1 value was measured in each segment. T1 values were significantly higher in septal segments with LGE versus those without. The sensitivity was 75% and specificity was 89.5% for T1 mapping for detection of LGE. The benefits of T1 mapping are promising, but as a new technique it is not well standardized.

Figure 3:

Imaging in a 60-year-old man with dilated cardiomyopathy and septal fibrosis. A, Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) was found in the midwall of the interventricular septum (arrow). B, Non–contrast-enhanced T1 mapping shows that the native T1 value of the septal region including LGE (enclosed by a white line) is 1382.2 msec, which is more than 1349.4 msec ± 1.2 (standard deviation) above that of the minimum T1 value (enclosed by a green line, 1262.4 msec ± 62.0) in this patient. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 29.)

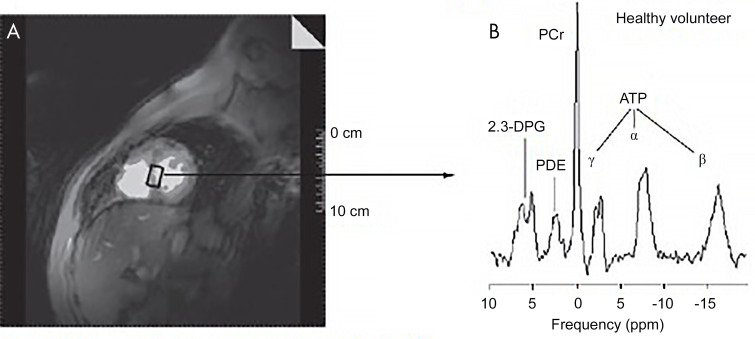

Metabolite Assessment by using CMR Spectroscopy

There are a variety of approaches for using MRI for metabolite and biochemical assessment including hydrogen 1 (1H), sodium 23 (23Na), and phosphate 31 (31P) imaging, which can be used to assess for early myocardial ischemia and viability (30–34) (Fig 4). 1H MR spectroscopy (MRS) can differentiate between myocardial fat, lactate, carnitine, myoglobin, and total creatinine levels (22,30). 23Na MRS measures intracellular and extracellular sodium changes in myocardium. 31P MRS is among the most well studied among spectroscopy techniques. Applications using these MRI approaches with CMR are described.

Figure 4:

Phosphate 31 (31P) spectroscopy in a healthy volunteer. A, Hydrogen 1 short-axis scout image in a healthy volunteer shows typical voxel selection in the myocardial intraventricular septum. B, A typical human cardiac 31P spectrum acquired using three-dimensional chemical shift imaging shows the following six resonances: three 31P atoms of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (α, β, and γ); phosphocreatine (PCr); 2, 3-diphosphoglyceric acid (2,3-DPG); and phosphodiesterase (PDE). (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 92.)

1H MRI.— 1H MRS and CMR were used to quantify myocardial triglyceride content and LV function in 134 asymptomatic patients (35). While LVEF was normal across all groups, the myocardial triglyceride content was 2.3-fold higher in those with impaired glucose tolerance and 2.1-fold higher in those with type II diabetes mellitus compared with individuals without obesity or diabetes. These results suggest that cardiac steatosis occurs early in the sequela of impaired glucose tolerance before clinical heart failure (35). Although still an experimental technique and far removed from screening, by focusing the CMR study on the lipid frequency peak rather than water, as per usual convention, respiratory-gated and electrocardiographically triggered CMR (Fig 5) can identify differences in myocardial lipid content in disease states, such as steatosis, versus healthy controls.

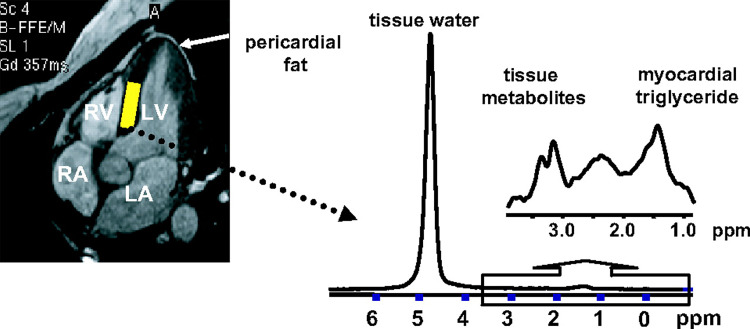

Figure 5:

Measurement of myocardial triglyceride content by localized MR spectroscopy. Left, Cine four-chamber cardiac image. In this image, heart muscle appears dark gray; blood in myocardial chambers and pericardial and adipose fat appear light gray. The volume for testing myocardial triglyceride content is placed within the intraventricular septum (yellow rectangle). Right, Spectrum from myocardial tissue collected during simultaneous end expiration and end systole with respiratory gating and electrocardiographically guided triggering. LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricle. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 35.)

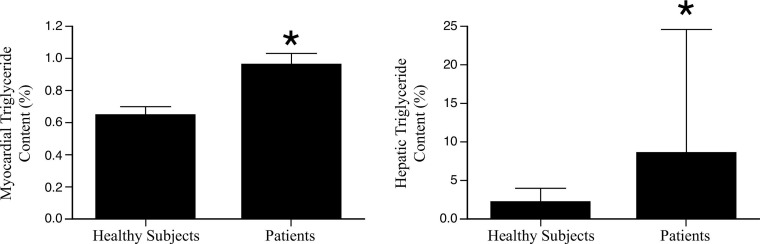

Another 1H MRS lipid spectroscopy study (36) (Fig 6) showed that myocardial triglyceride content is increased in patients with type II diabetes and was associated with LV diastolic dysfunction independent of other risk factors such as age, body mass index, and blood pressure. MRS does not expose the patient to radiation, nor does it require exogenous contrast material to distinguish between viable and nonviable myocardium. It may also assess for precursors to heart failure, including cardiac steatosis. But it is currently limited in its assessment of regional myocardial abnormalities due low temporal and spatial resolution (30,37). Although still a research technique without demonstrated clinical outcomes benefit, the use of CMR lipid spectroscopy to identify the presence of myocardial steatosis could play an important role as a potential biomarker for early detection of diabetic cardiomyopathy (36).

Figure 6:

Myocardial triglyceride content in patients with diabetes and controls using MR spectroscopy. Bars represent mean ± standard error. * indicates P < .05. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 36.)

31P MRI.— Phosphate energetics 31P CMR spectroscopy is an emerging technique that has been used to assess the effect of abnormal high-energy phosphate metabolism on myocardial function. Due to the metabolic demands required to maintain myocardial function, there is high turnover of phosphocreatine and adenosine triphosphate, which can be evaluated by 31P MRS (38). A total of 426 women suspected of having myocardial ischemia underwent MRS handgrip stress testing (38). Primary outcomes were death, MI, heart failure, stroke, other vascular events, and hospitalization for unstable angina. Cumulative freedom from events at 3 years were the following: 87% for women with no CAD and normal MRS; 57% for those with no CAD and abnormal MRS; and 52% for those with CAD (P < .01). After adjusting for CAD and cardiac risk factors, a phosphocreatine–adenosine triphosphate ratio decrease of 1% significantly increased the risk of a cardiovascular event by 4%. Among women without CAD, abnormal MRS consistent with myocardial ischemia predicted cardiovascular outcomes, notably higher rates of anginal hospitalization, repeat catheterization, and greater treatment costs.

In another study of 21 patients with type II diabetes (Fig 6), cardiac phosphocreatine-to–adenosine triphosphate ratio was lower in patients with type II diabetes than in healthy individuals (39). In addition, the abnormal phosphocreatine-to–adenosine triphosphate ratio was associated with LV diastolic dysfunction, which provides evidence that there is a relationship between myocardial energetics and cardiac function (40).

23Na MRI.— 23Na MRI is not actually a spectroscopy technique but does allow one to evaluate intracellular and extracellular sodium changes in myocardium. As sodium is increased in myocardial scar, this may potentially allow for evaluation of myocardial viability without the need for external contrast agents, although spatial resolution is its main limitation (32,33,41). Horn et al reported that acutely infarcted rat myocardium was noted by 23Na MRI to contain 160%–306% sodium content versus noninfarcted myocardium (P < .0083) (41). In chronic scar, sodium signal was increased 142% ± 6 (standard deviation) versus noninfarcted control. However, there was no difference for 23Na MRI of stunned or hibernating myocardium versus healthy controls. With technical advances, 23Na MRI could hold potential for tissue characterization, especially when combined with other techniques.

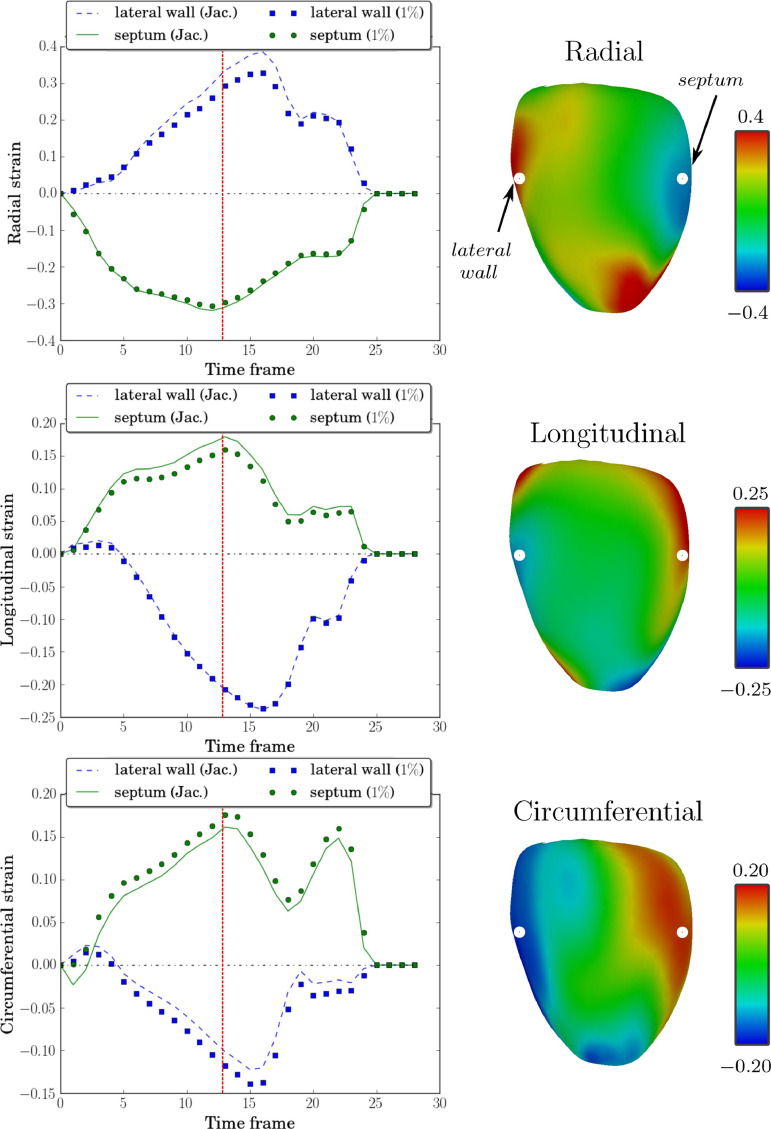

Myocardial deformation imaging.— CMR tagging (Fig 7) uses radiofrequency pulses of the myocardium to create lines or “tags” to assess cardiac deformation throughout the cardiac cycle (42). Harmonic phase analysis software processing of CMR-acquired tagged images provided the first Food and Drug Administration–approved evaluation of strain by CMR, although other methods to evaluate strain are possible as well, such as software evaluation of routine cine images. A study using tagged MRI and three-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated that 28 patients with type II diabetes with no known CAD, ischemia, or wall motion abnormality had reduced peak systolic circumferential (−14%) and longitudinal strains (−22%) and principal three-dimensional shortening strain (−10%) compared with 31 healthy controls (P < .001 for all) (43).

Figure 7:

The strain curves and systolic strain maps for a patient with septal flash. Left column: Comparisons of Jacobian strain and strain computed using a postprocessing of tagged images proposed approach at V s = 1%, with radial strain (top), longitudinal strain (middle), and circumferential strain (bottom) computed at a point in the septum and another in the lateral wall. Right column: Systolic strains (indicated by vertical red line in strain curves) plotted on the medial surface mesh computed using this approach at V s = 1%. The points in the lateral wall and septum at which strain curves are displayed (left) are indicated in the top row (right). Jac. = Jacobian. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 93.)

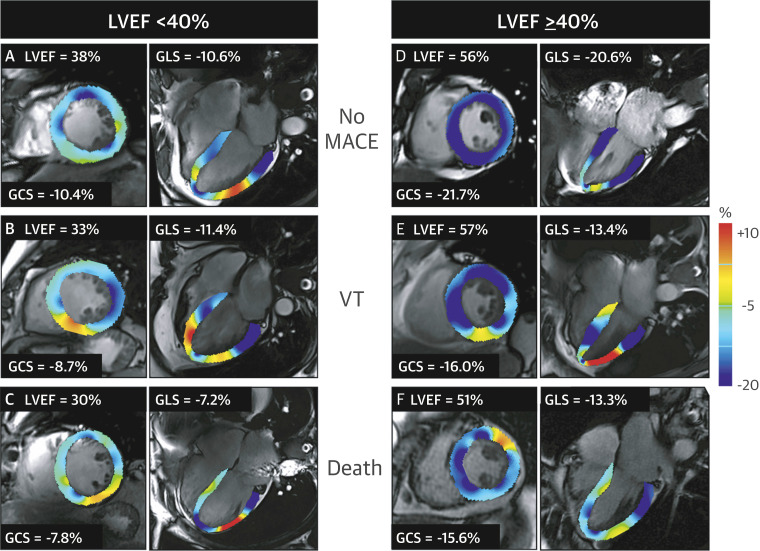

Another cohort study of 455 patients (Fig 8) (44) evaluated outcomes of and risk stratification in patients with myocarditis using CMR feature tracking. There was independent and incremental prognostic value of feature tracking greater than that of clinical features, LVEF, and LGE in patients with myocarditis.

Figure 8:

Examples of cardiovascular MR feature tracking abnormalities in different categories of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and its association with major adverse cardiac events (MACE). Global circumferential strain (GCS) and global longitudinal strain (GLS) are displayed at end systole for, A–C, patients with a reduced LVEF (< 40%) and for, D–F, patients with an LVEF greater than or equal to 40%. VT = sustained ventricular tachycardia. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 44.)

Overview of Impactful CMR Screening Studies

Now that we have introduced some of the proven CMR techniques that may have benefit to screen patients at increased cardiometabolic risk, we will discuss some of the impactful cohort studies for CMR screening.

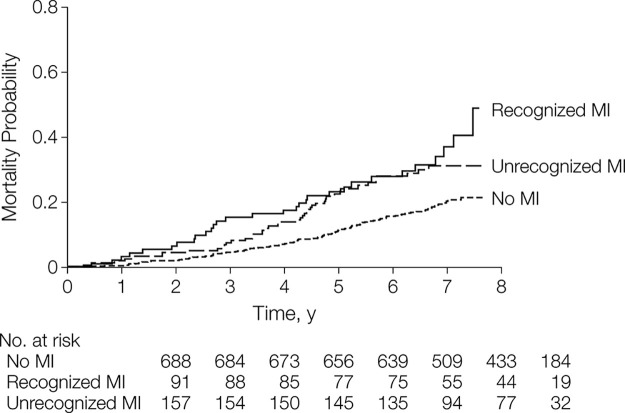

CMR versus Electrocardiography for Unrecognized MI Detection

First, the ICELAND MI study (24) demonstrated that unrecognized MI is underdiagnosed but carries significant prognostic implications. Many studies have validated CMR with LGE as the reference standard for diagnosing and quantifying infarct (45,46). While many population studies for cardiovascular risk stratification and prognosis have used electrocardiography to diagnose unrecognized MI, ICELAND MI compared the diagnostic performance of electrocardiography to CMR in an older, community population (24). In addition, they compared outcomes between cohorts without MI, with recognized MI, and with unrecognized MI. Recognized MI was defined on the basis of a prior history of MI confirmed by hospital records, while unrecognized MI was defined by no prior history of MI by hospital records and positive infarct-pattern LGE at CMR. A total of 936 community-based patients were followed for a median of 6.4 years. Overall, CMR detected unrecognized MI in 17% of patients, while electrocardiography only detected 5% of unrecognized MI. Cardiometabolic risk factors were associated with a higher prevalence of unrecognized MI, including diabetes and hypertension, as well as prior or current history of smoking.

After adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, and recognized MI, Schelbert et al (24) found that unrecognized MI detected with CMR was independently associated (Fig 9) with mortality and improved risk stratification, emphasizing the prognostic importance of detecting unrecognized MI in an older community-based population for appropriate medical management. By comparison, unrecognized MI detected with electrocardiography was not associated with mortality due to inferior accuracy relative to CMR. After an average follow-up of 10.5 years, the all-cause mortality rates of CMR-identified unrecognized MI were equivalent to recognized MI at 10 years (47). In particular, patients younger than 70 years of age appeared to have the highest mortality risk from unrecognized MI. Acharya et al (47) suggest two possible explanations for the acceleration of mortality rates in unrecognized MI relative to recognized MI. One possibility is that patients with unrecognized MI represent a different phenotype of CAD that may involve smaller arterial plaque rupture with a cumulative effect over time. Alternatively, or in conjunction, the recognized MI cohort may slow their progression due to medical management and behavior modification, thus allowing patients with unrecognized MI to catch up in terms of mortality risk.

Figure 9:

Mortality curves according to myocardial infarction (MI) status. (Reprinted, with permission, from reference 24.)

CMR for the Evaluation of Subclinical CVD

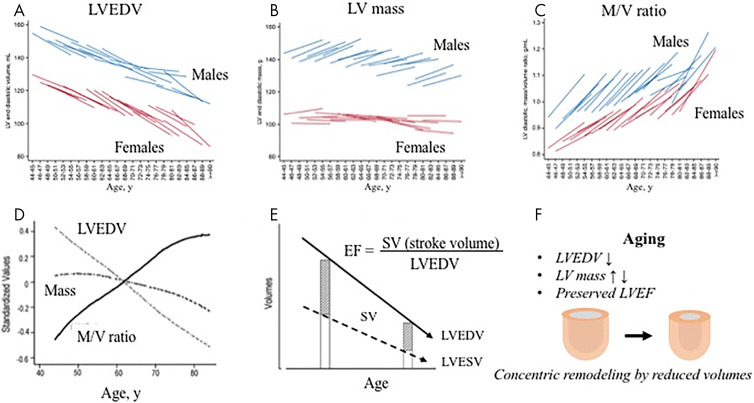

In addition to the important ICELAND MI study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) also allowed for longitudinal evaluation of 6814 asymptomatic patients aged 45–84 years to evaluate the progression of subclinical CVD (48). Baseline CMR was performed in 5004 patients, and 3015 underwent follow-up CMR 10 years later. From the MESA cohort data, Yoneyama et al (49) reported that over the 10-year interval, significant age-associated LV remodeling occurred and included progressively decreased LV volume with age-related increase in LV mass in males and mild decrease in LV mass in females (Fig 10). LV stroke volume also decreased with age, but LVEF was unchanged. Less remodeling was identified in patients who decreased their cardiometabolic risk factors over the interval, such as weight loss or improved blood pressure control. This is important to note because longitudinal MESA CMR data also revealed an increased incidence of adverse cardiac events in patients with evidence of LV remodeling. In particular, higher LV mass at baseline was associated with an 8.6 times increased risk of developing heart failure. As with detecting unrecognized MI, electrocardiography was found to be insensitive compared with CMR in detecting LV remodeling (50). In the MESA study, where coronary artery calcium had the strongest association with future CVD (hazard ratio, 2.3), CMR-determined LV mass best associated with future stroke (hazard ratio, 1.3) and heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.8) (51).

Figure 10:

The natural history of myocardial function in an adult human population. A, Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) statistically significantly decreased over 10 years for each age category, and, B, LV mass increased in men, and, C, mass-to-volume (M/V) ratio increased despite the fact that LV mass did not progressively increase (B, D). E, Although stroke volume (SV) progressively falls, LV ejection fraction (LVEF) maintains due to progressive decline in LV volumes. F, Aging is associated with the development of a concentric remodeling pattern secondary to a progressive decline in LV volume. Figures prepared based on data from Eng et al (94) and Cheng et al (95). (Reprinted, under a CC-BY license, from reference 49.)

CMR data from the MESA trial also revealed an association between LV remodeling and fibrosis. LGE was associated with increased LV mass index by 10 g/m2 and increased mass-to-volume ratio (0.1–0.2 g/mL) but decreased LVEF by 4% (52). CMR parametric mapping of native T1 enables detection of global interstitial fibrosis in the myocardium, which would otherwise be difficult to detect on standard LGE images (53). Reduced postcontrast T1 at year 10 was associated with lower LV mass index (r = 0.33), end-diastolic volume index (r = 0.25), and LVEF (in men only, r = 0.14) and longitudinally with a decrease in LV mass index (r = 0.20) and reduction in LVEF (in men only, r = 0.15). Furthermore, increased mass, fibrosis, and adverse LV remodeling were associated with hypertension.

Tagged gradient-echo CMR techniques allow for quantification of myocardial strain. Among 1100 patients in MESA who underwent CMR and harmonic phase imaging evaluation of tagged images, increased time to peak systolic strain was associated with age (0.49 msec/year, P = .007) and LV mass (1.20 msec/1 gm/m2.7, P < .001). Abnormal strain was also associated with decreased myocardial perfusion among screening patients without known coronary artery stenosis (time to peak systolic strain in the lowest myocardial blood flow tertile was 329.9 msec vs 294.5 msec in the highest, P = .034) (54). Beyond LV evaluation, in a right ventricle substudy of MESA with 4144 participants, right ventricular hypertrophy was associated with 2.52-fold increased risk of heart failure or death (55).

MESA CMR data also included vascular imaging with the ability to evaluate aortic dimensions and distensibility. Higher degrees of aorta stiffness were associated with hypertension, which was also associated with LV remodeling with concentric hypertrophy. Increased aortic stiffness was associated with a four times higher risk of cardiovascular events among those with otherwise low to intermediate risk of CVD (56).

Asymptomatic Screening for Patients with Increased Cardiometabolic Risk

In order for an imaging modality to be used as a prognostic tool in a clinically healthy population, it should be noninvasive, widely available, cost-effective, safe, and provide highly reproducible quantitative results (57). Screening should lead to improved prognostic assessment, treatment changes, and, ultimately, reduced burden of disease. Although no imaging modality meets all criteria perfectly, MRI has many advantages.

MRI allows for the assessment of the cardiovascular system with protocols specifically looking at the appearance of the vasculature, cardiac function, and myocardial tissue composition with the use of parametric T1 mapping (58,59). Methods of acquiring in- and out-of-phase images and calculating water-only and fat-only images using Dixon techniques also allow for the detection of fat and differentiation of adipose from lean tissue (60). With the use of dedicated multiecho gradient-echo sequence imaging, liver fat and iron content can be determined and used to identify pathologic links to diabetes and other metabolic diseases (61,62). MRS can also be used to evaluate the composition of lipids in adipose tissue compartments to provide detailed information about fat metabolism (63). This section provides an overview of MRI screening applications for cardiometabolic diseases.

Whole-Body MRI

Large epidemiologic studies such as the German National Cohort Study, Study of Health in Pomerania, and UK Biobank Imaging Study have standardized whole-body MRI protocols that use these techniques in an effort to obtain reproducible and comparable results as they relate to metabolic and cardiovascular conditions (64–66).

Adipose Tissue Measurements

Visceral adipose tissue is thought to be more important than subcutaneous fat in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance because of its increased metabolic activity and the secretion of vasoactive substances such as inflammatory markers and growth factors (67). As a result, the use of MRI to quantify visceral and epicardial fat has the potential to become a new screening tool for those at risk for metabolic disease and CVD. Several studies have revealed that the size of the epicardial or pericardial fat deposition is associated with the cardiometabolic risk profile for an individual (68–75). For example, epicardial fat accumulation has been associated with coronary artery atherosclerosis and diabetic cardiomyopathy (76).

Hepatic steatosis is also associated with a higher risk for type II diabetes and the development of cardiovascular complications (77). Because some cardiometabolic risk markers may be more affected by certain ectopic fat depots than others, future studies will need to investigate how visceral, epicardial, and hepatic adipose tissue affect various clinical outcomes. Increased epicardial fat may contribute to the impaired vasodilatory response of coronary arteries under various physiologic conditions, while excess visceral or hepatic fat may contribute more to insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, inflammation, and atherogenic dyslipidemia. Intrathoracic fat volume quantification using MRI has shown increased levels of intrathoracic visceral fat in patients with metabolic syndrome. Moreover, the intrathoracic fat volume is incrementally elevated among those with MI and appears to be an independent predictor of total infarct burden (78). A recent study also showed increased intrathoracic fat volume is associated with a greater reduction in remote myocardial tissue strain and contractile dysfunction in patients with CAD (79). The respective roles that all ectopic fat depots play in the various cardiovascular outcomes, such as angina, MI, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and aortic stenosis, represent exciting areas for future research (80,81).

Intramyocardial Triglyceride Content

CMR spectroscopy is an ongoing area of research that can be used to quantify intramyocardial triglyceride content. A recent study assessed asymptomatic women with increased cardiometabolic risk who did or did not have human immunodeficiency virus (82). It was reported that increased intramyocardial triglyceride content, as measured along the ventricular septum, was associated with impaired diastolic function. Diastolic dysfunction was quantified by calculating the left atrial passive ejection fraction. There was a threefold increase in intramyocardial content and a decrease in the left atrial passive ejection fraction for women receiving antiretroviral therapy. These results suggest that there may be a pathologic association of ectopic fat accumulation in myocardial cells in which MRI could be used as a screening tool for asymptomatic patients (82).

Myocardial Interstitial Matrix Expansion

Another area of research involves the use of T1-based CMR techniques to quantify myocardial interstitial matrix expansion in terms of the ECV fraction. It has been shown that adolescents with obesity, regardless of diabetes status, demonstrated a significantly greater expansion of the myocardial interstitial matrix relative to healthy volunteers. Furthermore, key components of cardiometabolic risk (inflammation and dysglycemia) were also associated with myocardial interstitial matrix expansion. This adverse myocardial tissue remodeling occurred before the onset of LV dysfunction and could potentially serve as an early screening test in the management of obesity and diabetes (83).

Evaluation of Cardiometabolic Risk Using Stress CMR in Symptomatic Patients

Stress CMR, or CMR perfusion, is most commonly performed as a high-temporal-resolution first-pass perfusion gadolinium-based contrast-enhanced imaging sequence with and without vasodilator stress. Stress CMR can be used to detect ischemia by inducing myocardial perfusion defects by vasodilator stress or wall motion abnormalities following dobutamine stress. The stress images can be compared with infarct presence and extent from LGE and, most commonly, with rest perfusion to assist in artifact determination. The benefits of stress CMR include avoidance of soft-tissue attenuation artifacts and ionizing radiation, which are limitations of nuclear stress tests. Stress CMR results are not limited by patient factors such as optimal acoustic windows, which is a disadvantage of stress echocardiography (84).

One meta-analysis by Gargiulo et al included several studies that used stress CMR to risk stratify more than 12 000 patients who were known or suspected to have CAD and assessed for clinical outcomes of MI or cardiac death at an average follow-up period of 25 months. This analysis showed that in patients known or suspected to have CAD, the absence of inducible ischemia at stress CMR predicts a low risk of cardiovascular events during a short to midterm follow-up period. The calculated annual major event rate after a normal stress CMR was approximately 1%, which is slightly higher than the estimated event rate in low-risk patients (< 1%). This demonstrated that stress CMR has a high negative predictive value (98.2%) for adverse cardiac events and that the absence of inducible perfusion defect or wall motion abnormality has the ability to correctly identify low-risk patients (85). Not only does stress CMR provide excellent prognostic data, but several studies show that it has a diagnostic accuracy comparable to PET (86).

More recently, the Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States (SPINS) study evaluated the prognostic value of CMR stress perfusion imaging in patients with chest pain (87). It additionally assessed downstream costs from subsequent cardiovascular testing. This retrospective study evaluated nearly 2400 patients over a 5-year duration for presence of ischemia and LGE at cardiac stress MRI. Primary outcomes included cardiovascular death or nonfatal MI. Secondary outcomes included a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, hospitalization for unstable angina or congestive heart failure, and late unplanned coronary artery bypass grafting. Those with ischemia and LGE experienced a greater than fourfold higher annual primary outcome rate and a greater than 10-fold higher rate of coronary revascularization during the 1st year after CMR compared with patients without ischemia or LGE. Negative ischemia and LGE had low average annual cost spent on ischemia testing (87). The SPINS study further supports the notion that stress CMR is an effective cardiac prognostic tool, which may in the future provide enhanced prognostication for patients with increased cardiometabolic risk (87).

Artificial Intelligence Applications

CMR is capable of producing images with a lot of detail, and thus reading these studies can be labor and time intensive. Use of artificial intelligence applications could allow for more rapid interpretation of studies, but concerns arise about reliability compared with manual reads. Nevertheless, advances in accelerated CMR imaging techniques, such as parallel imaging, in addition to advances in software postprocessing and artificial intelligence, offer the potential for a wealth of data to be mined from each CMR.

An automated method to quantify adipose tissue compartments has already been developed (88). In another application, Ruijsink et al (89) developed an automated program to analyze cardiac function using CMR, and it included a quality control algorithm to detect errors. The program comprised a preanalysis deep learning image quality control, followed by a deep learning algorithm for biventricular segmentation in long-axis and short-axis views, myocardial feature tracking, and a postanalysis quality control to detect erroneous results. Both healthy individuals and patients with known cardiac disease were evaluated, and the framework was compared with manual analysis. The automated analysis correlated highly with manual analysis for left and right ventricular volumes, strain, and filling and ejection rates. The sensitivity of detection of erroneous output was 95% for volume-derived parameters and 93% for feature-tracking strain. The study demonstrated that artificial intelligence could fairly accurately assess cine CMR studies without the need for direct clinician oversight.

Moreover, in the MESA study, Ambale-Venkatesh et al demonstrated the potential of using machine learning to develop more accurate cardiovascular risk prediction tools when combined with clinical data and subclinical markers of disease from imaging (90). Such advances demonstrate the promise and potential for increased CMR benefit if demonstrated to have a cost-effective outcome benefit in future research.

CMR Safety

Given these proven techniques, one must also consider that screening tests should be relatively safe when weighed against the benefit of diagnosing preclinical disease. CMR has no ionizing radiation and employs radiofrequency energy at spectra not associated with chronic human disease, such as cancer risk following x-ray exposure. Gadolinium-based contrast agents are very safe, with only rare anaphylaxis and without the acute renal injury risk as for CT contrast agents (91). Concerns about nephrogenic systemic fibrosis mostly among patients requiring hemodialysis emerged about 15 years ago, which led the Food and Drug Administration to restrict use for patients with glomerular filtration rate of greater than 30 mg/mmol (91). For such patients, and when using modern macrocyclic contrast molecules versus older linear contrast molecules, the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after contrast-enhanced CMR is very rare today (91). Some follow-up MRI studies have noted microscopic gadolinium deposition, particularly in patients who underwent four or more contrast-enhanced CMR examinations, although presently this has not been associated with any known harm (91). Last, while dobutamine stress testing does convey small risks, particularly of arrhythmia, vasodilator stress CMR has an excellent safety experience in multiple registries (89). Thus, CMR has very low risk, although this always must be weighed against the potential added outcome benefit (87).

Conclusion

In conclusion, while CMR is not currently approved for screening, this noninvasive modality is safe and increasingly available. CMR accurately evaluates cardiac structure and function. Research has demonstrated that T1 mapping, CMR spectroscopy, and CMR strain accurately diagnose and prognosticate cardiometabolic risk. If CMR demonstrates an outcome benefit, in the future there may be indication to use CMR to evaluate for preclinical disease to reduce cardiovascular risk. As patients with diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and elevated cardiometabolic risk often have concomitant renal disease, CMR techniques that do not require contrast agents will be highly desired, as gadolinium is generally not administered where renal function is severely limited. CMR has begun to demonstrate cost-effective outcomes, but more work needs to be done in this area to integrate the technology into routine screening examinations. In addition, further advances to limit scan times and speed processing of data would allow for expansion of CMR for the evaluation of various manifestations of cardiometabolic disease beyond research protocols and into routine clinical use.

C.P. and R.S. contributed equally to this work.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the United States Army, the Department of Defense (DoD), the Defense Health Agency, or the U.S. Government. Gadolinium contrast agents may involve off-label use for cardiac MRI. The identification of specific products or scientific instrumentation is considered an integral part of the scientific endeavor and does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the authors, DoD, or any component agency.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: C.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.S. disclosed no relevant relationships. P.P. disclosed no relevant relationships. R.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. K.S. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.S.B. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: author’s institution has grants/grants pending from Sanofi; author received payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from EMS, Novo Nordisk, Boston Scientific, and GE Healthcare. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. E.A.H. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: author has volunteer consultation with the Defense Health Agency and Department of Defense Cardiovascular Clinical and Imaging workgroups, volunteer activity with Society of Cardiac Computed Tomography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society of Cardiac MRI, and Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging; editorial board membership with ACC Cardiosmart, SCMR, and Atherosclerosis. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- CAD

- coronary artery disease

- CMR

- cardiac MRI

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- DIAD

- Detection of Ischemia in Asymptomatic Diabetics

- faCTor-64

- Screening For Asymptomatic Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Among High-Risk Diabetic Patients Using CT Angiography, Following Core 64

- LGE

- late gadolinium enhancement

- LV

- left ventricle

- LVEF

- left ventricular ejection fraction

- MESA

- Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- MI

- myocardial infarction

- MRS

- MR spectroscopy

- SPINS

- Stress CMR Perfusion Imaging in the United States

- STEMI

- ST-elevation MI

References

- 1.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Jaffe MG, et al. Recent Trends in Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States and Public Health Goals. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1(5):594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J 2016;37(42):3232–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth GA, Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic drivers of global cardiovascular mortality. N Engl J Med 2015;372(14):1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mechanick JI, Farkouh ME, Newman JD, Garvey WT. Cardiometabolic-Based Chronic Disease, Adiposity and Dysglycemia Drivers: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75(5):525–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 2004;109(3):433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mechanick JI, Rosenson RS, Pinney SP, Mancini DM, Narula J, Fuster V. Coronavirus and Cardiometabolic Syndrome: JACC Focus Seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76(17):2024–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunzell JD, Davidson M, Furberg CD, et al. Lipoprotein management in patients with cardiometabolic risk: consensus conference report from the American Diabetes Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(15):1512–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berry JD, Dyer A, Cai X, et al. Lifetime risks of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2012;366(4):321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas AS, Garbowski M, Ang AL, et al. A Decade Follow-up of a Thalassemia Major (TM) Cohort Monitored by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CMR): Significant Reduction In Patients with Cardiac Iron and In Total Mortality. Blood 2010;116(21):1011.20705768 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuruvilla S, Adenaw N, Katwal AB, Lipinski MJ, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes in nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7(2):250–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorenzo-Almorós A, Tuñón J, Orejas M, Cortés M, Egido J, Lorenzo Ó. Diagnostic approaches for diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2017;16(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirier P, Bogaty P, Garneau C, Marois L, Dumesnil JG. Diastolic dysfunction in normotensive men with well-controlled type 2 diabetes: importance of maneuvers in echocardiographic screening for preclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Care 2001;24(1):5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kass DA, Bronzwaer JG, Paulus WJ. What mechanisms underlie diastolic dysfunction in heart failure? Circ Res 2004;94(12):1533–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronson D. Cross-linking of glycated collagen in the pathogenesis of arterial and myocardial stiffening of aging and diabetes. J Hypertens 2003;21(1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidney S, Quesenberry CP Jr, Jaffe MG, Sorel M, Go AS, Rana JS. Heterogeneity in national U.S. mortality trends within heart disease subgroups, 2000-2015. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017;17(1):192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha JW, Lee HC, Kang ES, et al. Abnormal left ventricular longitudinal functional reserve in patients with diabetes mellitus: implication for detecting subclinical myocardial dysfunction using exercise tissue Doppler echocardiography. Heart 2007;93(12):1571–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widya RL, van der Meer RW, Smit JW, et al. Right ventricular involvement in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Care 2013;36(2):457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, et al. Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301(15):1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhlestein JB, Lappé DL, Lima JA, et al. Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312(21):2234–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rassi CH, Churchill TW, Tavares CA, et al. Use of imaging and clinical data to screen for cardiovascular disease in asymptomatic diabetics. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016;15(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellenger NG, Davies LC, Francis JM, Coats AJ, Pennell DJ. Reduction in sample size for studies of remodeling in heart failure by the use of cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2000;2(4):271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pickett CA, Cheezum MK, Kassop D, Villines TC, Hulten EA. Accuracy of cardiac CT, radionucleotide and invasive ventriculography, two- and three-dimensional echocardiography, and SPECT for left and right ventricular ejection fraction compared with cardiac MRI: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16(8):848–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi SB, Connelly KA, Jimenez-Juan L, et al. Potential clinical impact of cardiovascular magnetic resonance assessment of ejection fraction on eligibility for cardioverter defibrillator implantation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2012;14(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schelbert EB, Cao JJ, Sigurdsson S, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance in older adults. JAMA 2012;308(9):890–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jellis C, Wright J, Kennedy D, et al. Association of imaging markers of myocardial fibrosis with metabolic and functional disturbances in early diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4(6):693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kammerlander AA, Marzluf BA, Zotter-Tufaro C, et al. T1 Mapping by CMR Imaging: From Histological Validation to Clinical Implication. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;9(1):14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kali A, Choi EY, Sharif B, et al. Native T1 Mapping by 3-T CMR Imaging for Characterization of Chronic Myocardial Infarctions. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8(9):1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu D, Borlotti A, Viliani D, et al. CMR Native T1 Mapping Allows Differentiation of Reversible Versus Irreversible Myocardial Damage in ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An OxAMI Study (Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10(8):e005986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yanagisawa F, Amano Y, Tachi M, Inui K, Asai K, Kumita S. Non-contrast-enhanced T1 Mapping of Dilated Cardiomyopathy: Comparison between Native T1 Values and Late Gadolinium Enhancement. Magn Reson Med Sci 2019;18(1):12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudsmith LE, Neubauer S. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in myocardial disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2(1):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holloway CJ, Suttie J, Dass S, Neubauer S. Clinical cardiac magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2011;54(3):320–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandstede JJ, Pabst T, Beer M, et al. Assessment of myocardial infarction in humans with (23)Na MR imaging: comparison with cine MR imaging and delayed contrast enhancement. Radiology 2001;221(1):222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandstede JJ, Hillenbrand H, Beer M, et al. Time course of 23Na signal intensity after myocardial infarction in humans. Magn Reson Med 2004;52(3):545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jansen MA, Van Emous JG, Nederhoff MG, Van Echteld CJ. Assessment of myocardial viability by intracellular 23Na magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2004;110(22):3457–3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGavock JM, Lingvay I, Zib I, et al. Cardiac steatosis in diabetes mellitus: a 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation 2007;116(10):1170–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rijzewijk LJ, van der Meer RW, Smit JW, et al. Myocardial steatosis is an independent predictor of diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52(22):1793–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bizino MB, Hammer S, Lamb HJ. Metabolic imaging of the human heart: clinical application of magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Heart 2014;100(11):881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Buchthal SD, et al. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: results from the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation 2004;109(24):2993–2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheuermann-Freestone M, Madsen PL, Manners D, et al. Abnormal cardiac and skeletal muscle energy metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation 2003;107(24):3040–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diamant M, Lamb HJ, Groeneveld Y, et al. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with altered myocardial metabolism in asymptomatic normotensive patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(2):328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horn M, Weidensteiner C, Scheffer H, et al. Detection of myocardial viability based on measurement of sodium content: A (23)Na-NMR study. Magn Reson Med 2001;45(5):756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischer SE, McKinnon GC, Maier SE, Boesiger P. Improved myocardial tagging contrast. Magn Reson Med 1993;30(2):191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fonseca CG, Dissanayake AM, Doughty RN, et al. Three-dimensional assessment of left ventricular systolic strain in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, diastolic dysfunction, and normal ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol 2004;94(11):1391–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer K, Obrist SJ, Erne SA, et al. Feature Tracking Myocardial Strain Incrementally Improves Prognostication in Myocarditis Beyond Traditional CMR Imaging Features. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13(9):1891–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nadour W, Doyle M, Williams RB, et al. Does the presence of Q waves on the EKG accurately predict prior myocardial infarction when compared to cardiac magnetic resonance using late gadolinium enhancement? A cross-population study of noninfarct vs infarct patients. Heart Rhythm 2014;11(11):2018–2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, Holly TA, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet 2003;361(9355):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acharya T, Aspelund T, Jonasson TF, et al. Association of unrecognized myocardial infarction with long-term outcomes in community-dwelling older adults: the ICELAND MI Study. JAMA Cardiol 2018;3(11):1101–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156(9):871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoneyama K, Venkatesh BA, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Lima JAC. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in an adult human population: serial observations from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain A, Tandri H, Dalal D, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic utility of electrocardiography for left ventricular hypertrophy defined by magnetic resonance imaging in relationship to ethnicity: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am Heart J 2010;159(4):652–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jain A, McClelland RL, Polak JF, et al. Cardiovascular imaging for assessing cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic men versus women: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ambale Venkatesh B, Volpe GJ, Donekal S, et al. Association of longitudinal changes in left ventricular structure and function with myocardial fibrosis: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis study. Hypertension 2014;64(3):508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu C-Y, Liu Y-C, Wu C, et al. Evaluation of age-related interstitial myocardial fibrosis with cardiac magnetic resonance contrast-enhanced T1 mapping: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(14):1280–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosen BD, Fernandes VR, Nasir K, et al. Age, increased left ventricular mass, and lower regional myocardial perfusion are related to greater extent of myocardial dyssynchrony in asymptomatic individuals: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation 2009;120(10):859–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Lima JA, et al. Right ventricular structure is associated with the risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)--right ventricle study. Circulation 2012;126(14):1681–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Redheuil A, Wu CO, Kachenoura N, et al. Proximal aortic distensibility is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and incident CV events: the MESA study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64(24):2619–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gatidis S, Schlett CL, Notohamiprodjo M, Bamberg F. Imaging-based characterization of cardiometabolic phenotypes focusing on whole-body MRI--an approach to disease prevention and personalized treatment. Br J Radiol 2016;89(1059):20150829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM, et al. ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48(7):1475–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Messroghli DR, Moon JC, Ferreira VM, et al. Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of T1, T2, T2* and extracellular volume: A consensus statement by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the European Association for Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI). J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19(1):75 [Published correction appears in J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018;20(1):9.]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machann J, Thamer C, Schnoedt B, et al. Standardized assessment of whole body adipose tissue topography by MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005;21(4):455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kühn JP, Hernando D, Muñoz del Rio A, et al. Effect of multipeak spectral modeling of fat for liver iron and fat quantification: correlation of biopsy with MR imaging results. Radiology 2012;265(1):133–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhong X, Nickel MD, Kannengiesser SA, Dale BM, Kiefer B, Bashir MR. Liver fat quantification using a multi-step adaptive fitting approach with multi-echo GRE imaging. Magn Reson Med 2014;72(5):1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guiu B, Petit JM, Loffroy R, et al. Quantification of liver fat content: comparison of triple-echo chemical shift gradient-echo imaging and in vivo proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology 2009;250(1):95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bamberg F, Kauczor HU, Weckbach S, et al. Whole-Body MR Imaging in the German National Cohort: Rationale, Design, and Technical Background. Radiology 2015;277(1):206–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hegenscheid K, Kühn JP, Völzke H, Biffar R, Hosten N, Puls R. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging of healthy volunteers: pilot study results from the population-based SHIP study. Rofo 2009;181(8):748–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petersen SE, Matthews PM, Bamberg F, et al. Imaging in population science: cardiovascular magnetic resonance in 100,000 participants of UK Biobank - rationale, challenges and approaches. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15(1):46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2007;116(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tadros TM, Massaro JM, Rosito GA, et al. Pericardial fat volume correlates with inflammatory markers: the Framingham Heart Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(5):1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117(5):605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu J, Fox CS, Hickson D, et al. Pericardial adipose tissue, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Jackson heart study. Diabetes Care 2010;33(7):1635–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fox CS, Gona P, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and measures of left ventricular structure and function: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2009;119(12):1586–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McAuley PA, Hsu FC, Loman KK, et al. Liver attenuation, pericardial adipose tissue, obesity, and insulin resistance: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(9):1855–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Miao C, Chen S, Ding J, et al. The association of pericardial fat with coronary artery plaque index at MR imaging: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Radiology 2011;261(1):109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thanassoulis G, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and risk factor correlates of high pericardial and intrathoracic fat depots in the Framingham heart study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;3(5):559–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iacobellis G, Leonetti F. Epicardial adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90(11):6300–6302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen O, Sharma A, Ahmad I, et al. Correlation between pericardial, mediastinal, and intrathoracic fat volumes with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, and cardiac risk factors. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16(1):37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363(14):1341–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jolly US, Soliman A, McKenzie C, et al. Intra-thoracic fat volume is associated with myocardial infarction in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Todd A, Satriano A, Fenwick K, et al. Intra-thoracic adiposity is associated with impaired contractile function in patients with coronary artery disease: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;35(1):121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iozzo P. Myocardial, perivascular, and epicardial fat. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S371–S379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Després JP. Body fat distribution and risk of cardiovascular disease: an update. Circulation 2012;126(10):1301–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Toribio M, Neilan TG, Awadalla M, et al. Intramyocardial Triglycerides Among Women With vs Without HIV: Hormonal Correlates and Functional Consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104(12):6090–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shah RV, Abbasi SA, Neilan TG, et al. Myocardial tissue remodeling in adolescent obesity. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2(4):e000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gibbons RJ. Noninvasive diagnosis and prognosis assessment in chronic coronary artery disease: stress testing with and without imaging perspective. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2008;1(3):257–269; discussion 269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gargiulo P, Dellegrottaglie S, Bruzzese D, et al. The prognostic value of normal stress cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6(4):574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Greenwood JP, Herzog BA, Brown JM, Everett CC, Plein S. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography in Suspected Coronary Heart Disease. Ann Intern Med 2016;165(11):830–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kwong RY, Ge Y, Steel K, et al. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Stress Perfusion Imaging for Evaluation of Patients With Chest Pain. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74(14):1741–1755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Würslin C, Machann J, Rempp H, Claussen C, Yang B, Schick F. Topography mapping of whole body adipose tissue using A fully automated and standardized procedure. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010;31(2):430–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ruijsink B, Puyol-Antón E, Oksuz I, et al. Fully Automated, Quality-Controlled Cardiac Analysis From CMR: Validation and Large-Scale Application to Characterize Cardiac Function. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13(3):684–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ambale-Venkatesh B, Yang X, Wu CO, et al. Cardiovascular Event Prediction by Machine Learning: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2017;121(9):1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.American College of Radiology. ACR manual on contrast media. Reston, Va: American College of Radiology, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hudsmith LE, Neubauer S. Detection of myocardial disorders by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5(Suppl 2):S49–S56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sinclair M, Peressutti D, Puyol-Antón E, et al. Myocardial strain computed at multiple spatial scales from tagged magnetic resonance imaging: Estimating cardiac biomarkers for CRT patients. Med Image Anal 2018;43:169–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eng J, McClelland RL, Gomes AS, et al. Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling and Age Assessed with Cardiac MR Imaging: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Radiology 2016;278(3):714–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheng S, Fernandes VR, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Lima JA. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2(3):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]