Abstract

Published results of efficacy and effectiveness studies on complementary health approaches should lead to widespread uptake of evidence-based practices, but too often, the scientific pathway ends prematurely, before the best ways to improve adoption, implementation, and sustainability can be determined. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) supports the full continuum of the biomedical research pipeline, whereby a complementary health intervention moves from basic and mechanistic research through efficacy trials and through dissemination and implementation. Implementation science has traditionally been thought of as something that only happens after efficacy and effectiveness have been demonstrated, but it can be prudent to evaluate implementation measures earlier in the process. Implementation science assesses more than just barriers and facilitators; it evaluates specific implementation strategies and characterizes the extent that the intervention is modified within the context of the implementation strategy and health care delivery setting. The best choices for implementation science in complementary health interventions depend on the research questions. Implementation science that tests strategies to address implementation at multiple ecologic levels is a high priority to NCCIH.

Keywords: implementation science, dissemination research, complementary and integrative health

Introduction

Each year, billions are spent on health research, and hundreds of billions are spent on health, health care delivery, and public health interventions in clinical and community settings.1 Despite the sizable investment, available evidence from research studies often takes many years before being implemented into routine clinical practice.2,3 Much less is spent on research to understand how best to ensure that the lessons learned from research are relevant to inform and improve delivery of services and the utilization and sustainability of evidence-based tools and approaches.1 Published results of efficacy and effectiveness studies on complementary health approaches should lead to widespread uptake of evidence-based practices,4 but too often the scientific pathway ends prematurely, before the best ways to improve adoption, implementation, and sustainability can be determined.

For many years, health researchers may have assumed that tools and interventions deemed efficacious would be readily adopted and implemented; however, compelling evidence suggests that this has not been the case.2 Even when added information, tools, and interventions have been tested within clinical or community-based trials, the development of knowledge to support their broader dissemination and implementation (e.g., cost and financing of the intervention, practitioner training and coaching, availability of resources, integration into community or health care systems, delivery to vulnerable or difficult-to-reach populations, monitoring the quality of intervention delivery, and implementation of policies and guidelines) has often remained outside the scope of these large-scale pragmatic trials.5

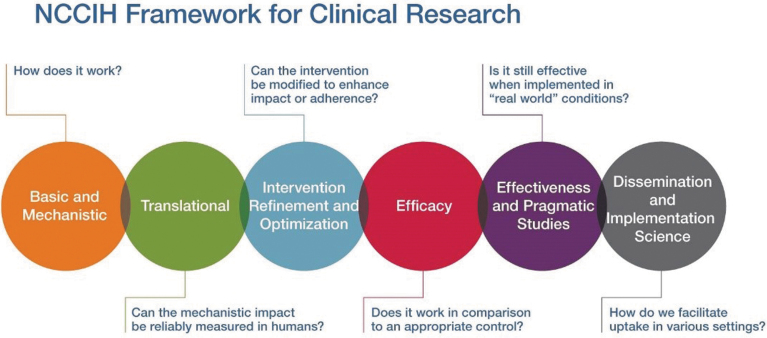

The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) supports the full continuum of the biomedical research pipeline, whereby a complementary health intervention moves from basic and mechanistic research through efficacy trials and through dissemination and implementation (Fig. 1). Basic and mechanistic research gives insights into which components of an intervention might be the causal agents of biologic and/or psychological effects. These mechanisms of action inform researchers about how and for whom an intervention works and under what circumstances. Rigorous efficacy research—the next step in the research pipeline—involves strict limitations on who may participate to minimize error, bias, and confounding. This emphasis on internal validity enhances confidence in interpreting positive results as indicating a causal relationship between the intervention(s) and outcome(s). The next step in the research pipeline is effectiveness research. In recent years, NCCIH has supported research using effectiveness methodologies such as the pragmatic clinical trial, which is designed to test interventions of known efficacy in real-world settings with an emphasis on external validity.6 In this type of research, there are few limitations on who may participate in an effort to match study participants to the population intended to benefit from the interventions.

FIG. 1.

Full continuum of biomedical research pipeline supported by NCCIH. NCCIH, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Color images are available online.

Dissemination and implementation research, the final steps in the research continuum, intend to bridge the gap between research, practice, and policy by building a knowledge base about how health information, effective interventions, and new clinical practices, guidelines, and policies are communicated and integrated for public health and health care service use in specific settings. While efficacy and effectiveness research are designed to answer the question, “which intervention(s) should we use,” dissemination research asks, “are the relevant clinicians and target population aware of the novel evidence-based intervention(s),” and implementation science focuses on, “how can these novel evidence-based intervention(s) be more widely and rapidly used in practice?”

It should be noted that for complementary and integrative health, the novel evidence-based intervention may be an existing intervention used in a novel setting (e.g., use of acupuncture in a hospital emergency department). The goal is to decrease the time between establishing the evidence base of interventions and the widespread uptake and adoption of these interventions.

Definitions

Dissemination research is the scientific study of targeted distribution of information and intervention materials to a specific public health or clinical practice audience. The intent is to understand how best to spread and sustain knowledge of the evidence-based interventions.7

Critical information is often lacking about how, when, by whom, and under what circumstances evidence spreads throughout communities, organizations, front line workers, and consumers of public health and clinical services. As a prerequisite for unpacking how information can lead to intervention or health service changes, there must be an understanding of how and why information on physical and behavioral health, preventive services, disease management, decision-making, and other interventions may or may not reach stakeholders.8

Implementation science is the scientific study of the use of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions into clinical and community settings to improve patient outcomes and benefit population health.9,10

Implementation science seeks to understand the contextual behavior of practitioners and support staff, organizations, consumers and family members, and policymakers as key influences on the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of evidence-based health interventions and guidelines (e.g., The Community Guide,11 the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,12 and the recommendations and guidelines of the federal government and of clinical and professional societies). Implementation science studies should not assume that effective interventions can be integrated into any service setting, and for consumer groups and populations, without attention to local context.

Furthermore, implementation science should not assume that a unidirectional flow of information (e.g., publishing a recommendation, trial, or guideline) is sufficient to achieve practice change. Relevant studies should develop a knowledge base about how interventions are integrated within diverse practice settings and patient populations, which will require more than the distribution of information about intervention effectiveness.

Differentiating Implementation Science from Implementation and Dissemination

Understanding the difference between implementation science and implementation and dissemination is key for successfully moving interventions through the research pipeline from the laboratory to clinical practice settings.

In the context of complementary health approaches, for example, there is much evidence to support efficacy and effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic low-back pain (cLBP),13 and clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Physicians recommend acupuncture as a first-line treatment for this condition14; however, there is very limited utilization or referrals in conventional health care settings for acupuncture to treat patients with cLBP.15

For this scenario, an example of an implementation question might be: If we start offering acupuncture for patients with cLBP in our clinic, do these patients experience a decrease in cLBP and an increase in quality of life? This is an efficacy/effectiveness question, which asks: What treatment should we use? By contrast, an implementation science question might be: Which strategies can we use to make acupuncture referrals easier, coach practitioners on the efficacy of acupuncture for cLBP, and encourage patients with cLBP to request acupuncture and initiate acupuncture as a treatment for cLBP? In this scenario, what is being tested are the different implementation strategies that focus on how we increase uptake and adoption.

Implementation Science for Complementary and Integrative Health

Patients typically engage in complementary health interventions as self-care, and many pay out-of-pocket for these interventions.16 Currently, there is a push to incorporate complementary health interventions into the U.S. medical system, but integration into conventional health care settings may not be ideal for all complementary health interventions.

It is important to be clear about whether the goal is to incorporate the approach(es) into the traditional health care system and/or to inform the public about what is available and how to access complementary health interventions on their own. The U.S. health care model has a long history of working in tandem with outside services such as smoking cessation and weight loss programs. Health care providers routinely counsel patients to stop smoking or lose weight and recommend resources available in the community to help accomplish their goals. Similarly, health care providers could also counsel patients to try yoga, Tai Chi, or other community-based complementary health programs.

Implementing complementary health approaches into the conventional health care system is not without barriers. One such barrier is that some empirically supported complementary health interventions may not be preferentially reimbursed.17 Patient expectations are another barrier that may have an impact on implementation. When patients visit a physician, they may expect to receive a prescription or undergo medical tests or procedures. However, if the physician instead recommends the patient to see an acupuncturist or try Tai Chi, the patient may perceive the referral as a reduced level of care.

In addition, underserved and under-researched populations have special considerations in implementation science approaches. Members of these populations are most likely to respond to advice from someone who looks like them, speaks their language, and meets them at their level.18 Barriers that can affect all populations, such as copays, transportation issues, and getting time off work for appointments and treatments, may be magnified in low-income communities.19,20

In contrast, not all cultural barriers perceived as difficult may be so in actuality; for example, recruiting low-income populations in some yoga trials has been less difficult than anticipated.21 Lack of a physician recommendation—or the perception that the physician does not support the use of an approach previously demonstrated to be effective—is another barrier to implementation. This may be changing, however, as a recent study showed that ∼50% of physicians recommend complementary therapies to at least some patients,22 which suggests an opportunity to further improve communication with physicians about the evidence supporting these therapies.

Implementation science has traditionally been thought of as something that happens only after efficacy and effectiveness have been demonstrated, but it can be prudent to evaluate implementation measures earlier in the process.23 Implementation science assesses more than just barriers and facilitators; it evaluates specific implementation strategies and characterizes the extent that the intervention is modified within the context of the implementation strategy and health care delivery setting.

Level of Evidence Needed

How much evidence is required to move an intervention to implementation? The answer to the question of what is “enough” evidence may be contextual. An individual health care provider may be willing to treat using an unproven intervention in response to a suggestion from a colleague, but federal agencies require far more rigor before issuing guidelines.

The following working definition for having sufficient evidence to move an intervention to implementation is meant to provide guidance as opposed to providing a set rule.

An intervention has sufficient evidence when multiple independent research studies have been conducted and24,25:

Results that indicate the intervention shows a clinically significant improvement compared to appropriate control condition(s) (demonstration of noninferiority to standard of care or other widely adopted treatments of demonstrated effectiveness)

Studies are adequately powered, and results are based on sound statistical methodology

Results are published in peer-reviewed journals

Studies demonstrated effectiveness in real-world health care setting

Results are generalizable to the target implementation populations (including health care systems, providers, and patients)

There is a demonstrated knowledge gap of the intervention's demonstrated effectiveness (dissemination science) and/or lack of adoption of the intervention by health care providers (implementation science).

Once the intervention has been determined to have sufficient evidence, it is time to start thinking about effective implementation strategies to scale up and scale out the intervention.

Methods/Measurement/Instruments

Implementation science frameworks

A multitude of frameworks and theories for implementation research have been published.26–28 They may be helpful for study design, and different frameworks are best suited for different purposes. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), published by Damschroder and colleagues in 2009, helps identify aspects and determinants of implementation that should be assessed during the planning process.29 The CFIR provides a menu of constructs, arranged across five domains, that can be helpful when identifying the implementation strategies to be tested. The domains are29:

Intervention characteristics (including essential, indispensable “core components” and an “adaptive periphery” that can be modified)

Inner setting (features of structural, political, and cultural contexts through which the implementation process will proceed)

Outer setting (the economic, political, and social context within which an organization functions)

Characteristics of individuals involved (including the dynamic interplay between individuals and the organizations within which they function)

Process for accomplishing the intervention (usually, an active change process aimed to achieve individual- and organizational-level use of the intervention).

This model may be particularly useful in identifying and developing strategies to work with existing facilitators and to overcome barriers to implementation. Use of the CFIR promotes the consistent use of constructs, systematic analysis, and organization of study findings. The model can be customized to a variety of settings and scenarios.30

There is a plethora of implementation strategies found in the literature. Many strategies were the same or highly similar, so an expert panel was convened to distill them into a more standardized listing. This group, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC), defined a list of 73 implementation strategies and created a crosswalk between ERIC and CFIR.31,32

Implementation science methods

Implementation science relies on qualitative and quantitative methods to understand the strategies and processes used to implement an evidence-based intervention, the barriers and facilitators to implementing the change, the uptake and adoption of the intervention, and how all of these may vary across different types of contexts.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative methods are essential in implementation science because they rigorously address “how” and “why” questions relevant to implementation outcomes such as feasibility, adoption, and sustainability.33,34 Different topics may be addressed at different time points; for example, feasibility is often addressed early.33 Types of approaches include in-depth interviews35; qualitative pilot studies; qualitative semistructured interviews and focus groups; participant observation33; and ethnography to capture implementation microprocesses, at the level of individual interactions.36 The choice of methods depends on the research questions being addressed.33

Quantitative methods

Quantitative methods are especially important for exploring the extent and variation of change (within and across units) induced by implementation strategies. These methods are used at later stages of implementation research and involve powered tests of the effect of one or more implementation strategies. These methods are likely to use a between-site or a within- and between-site research design with at least one quantitative outcome. Types of quantitative data collection include structured surveys; use of administrative records, including payor and health expenditure records; extraction from electronic health records; and direct observations. Study designs may be observational or experimental/quasi-experimental.

Quantitative studies in implementation science differ from efficacy or effectiveness studies in that they do not focus on health outcomes at the patient level. Instead, they look at outcomes at various levels within the system that support the implementation of an intervention, such as the health care provider, clinic, or health department.37 A variety of implementation outcomes, such as adoption, feasibility, implementation cost, penetration/reach, and sustainability, have been assessed quantitatively in implementation science studies.37

Mixed methods

The term “mixed methods” refers to the combination of at least one numerical (quantitative) research method and at least one non-numerical (qualitative) research method into a single study design. While this may seem simple, mixed methods research is complex, and deciding how to handle and prioritize the different data is crucial.38 The rationale for using mixed methods is that using a combination of methods can provide a better understanding than a single approach. Qualitative methods can provide deeper understanding of a scenario, such as understanding a success or failure of an attempt to implement an intervention, whereas quantitative methods can confirm or refute hypotheses and provide broader understanding about the predictors of successful or unsuccessful implementation.39

Study designs in implementation science

A variety of study designs are used in implementation science.25 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of various types are commonly used, but quasi-experimental or observational designs may be better choices in some situations. Concerns have been expressed about the possible overuse of traditional RCT study designs in implementation science because these designs maximize internal validity, while implementation science benefits from an increased emphasis on external validity. Therefore, designs that emphasize external validity may be better suited for answering some implementation science questions.40

Experimental studies

Randomized experimental study designs accounted for most study designs in a recent review of published protocols for implementation science.40 Because implementation science involves different questions and outcome measures than those of efficacy or effectiveness research, a variety of randomized designs and nonrandomized designs may be useful. Cluster randomized designs, in which sites or clinics rather than individual patients are the units of randomization, are common.40,41 When combinations of implementation strategies are being assessed, factorial or fractional-factorial designs that randomize sites or providers to different combinations of strategies may be used.41 For research on optimizing sequences of implementation strategies, a multistage variant of factorial design called the sequential, multiple-assignment, randomized trial (SMART) may be used.41

Some RCTs have hybrid implementation-effectiveness designs in which data are collected on effectiveness outcomes, as well as implementation outcomes.42 For example, a trial with the primary aim of determining the effectiveness of an intervention might also seek to understand the context for implementation. A trial designed to test the utility of an implementation strategy might also assess clinical outcomes associated with the intervention. Although these designs have advantages, such as encouraging consideration of implementation issues during the early stages of research on an intervention, it is important to remember that an intervention is not ready for implementation until multiple independent high-quality studies have demonstrated its effectiveness.

Quasi-experimental studies

The term “quasi-experimental” refers to a variety of nonrandomized intervention study designs. Quasi-experimental designs are frequently used when it is not feasible, for ethical or practical reasons, to randomly assign some participants to a control group.

Stepped-wedge designs may be used when it is important that all sites receive the intervention at some point during the trial. In this study design, sites receive the intervention in waves, starting at different time points. Data are collected from all sites throughout the study, so the sites that receive the intervention later serve as controls for the early-intervention sites, and lessons learned at early sites can be applied to later sites.41

One example of a quasi-experimental design is regression point displacement, in which the actual results of an intervention are compared with the expected results, which are calculated based on archival data for comparable groups of people. This study design is useful when there are a limited number of units to compare, such as only a few sites or communities.43

Another quasi-experimental design, the interrupted time series, relies on repeated data collections from intervention sites to compare outcomes with the preimplementation trend; this design is well-suited for situations in which an intervention has already been widely implemented, making it impossible to identify a control group.41

A third type of quasi-experimental design, the regression discontinuity design, takes advantage of real-world cutoff points (e.g., for age or blood pressure) that determine eligibility for an intervention; outcomes just above the cutoff point are compared with the outcomes just below it.44

Intervention optimization

Special study designs can be used to optimize interventions. The SMART design described earlier is one example. Another is the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST). MOST includes a screening phase, in which intervention components are accepted or rejected based on performance; a refining phase, in which the included components are fine-tuned and issues such as dosage are examined; and a confirming phase in which the optimized intervention is evaluated.45

NCCIH Future Directions in Implementation Science

The best choices for implementation science in complementary health interventions depend on the research questions. Implementation science that tests strategies to address implementation at multiple ecologic levels is a high priority to NCCIH (Table 1). In addition, to help move implementation science forward, there should be a framework for levels or grades of evidence for complementary health interventions, similar to or perhaps based on those of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force,12 The Community Guide,11 or the National Cancer Institute's Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs (formerly known as Research-Tested Intervention Programs).46 These frameworks have ways of identifying interventions that are “promising” or “emerging” even if they cannot yet be recommended for use.

Table 1.

Dissemination and Implementation Research Questions at Different Ecologic Levels

| Ecologic level | Examples |

|---|---|

| Provider level | What strategies are used to engage individual health care practitioners? What strategies are used to engage professional societies? |

| Patient level | How can patient populations be targeted to create “pull” strategies to adopt the novel intervention? |

| Community level | How can community leaders be engaged? What resources do advocacy groups have that can be leveraged to increase supply and demand for the novel intervention? |

| Health care system level | What are the systemic barriers and facilitators within the health care system to uptake and adoption of the novel intervention? |

| Payer level | How does the intervention align with the interests of third-party payers that might promote reimbursement? How much do out-of-pocket costs influence a decision to begin or continue using a novel intervention? |

| Legislative level | Are there legal barriers or facilitators to implementing a novel intervention? |

Adding to or refining Cochrane reviews to specify levels of evidence also may be helpful in identifying additional research that needs to be conducted. The goal is to maximize and build upon current evidence to shorten the time for widespread uptake and adoption of complementary health interventions. Investigators who conduct efficacy and effectiveness research should be aware of the benefits of including in their publications information on likely barriers to uptake and adoption. Outcome frameworks that include feasibility and adaptation of the intervention are helpful.

Identifying and engaging with key internal and external stakeholders is important when conducting efficacy and effectiveness research but becomes essential during dissemination and implementation.47 When engaging with stakeholders outside of the research community, it is important to use short, plain-language communications to describe successful implementation strategies for complementary health approaches. Making complementary health interventions available to low-income and underreached populations is also an important consideration for future implementation studies to address disparities in access.

Furthermore, evidence-based complementary health approaches could be included in prospective payment budgets. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Center could be one potential pathway for future research or partnership; however, Current Procedural Terminology codes do not exist for many complementary health interventions,48 which remains a barrier to conducting implementation studies.

Implementation of evidence-based complementary health interventions to reach all populations that would benefit equitably from these interventions and to continue moving complementary and integrative health fields forward is important to NCCIH.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shawn Stout for her exceptional assistance. The authors also thank the other participants in the NCCIH Implementation Science Working Group; Sara Rue, Christina Brackna, and Mary Beth Kester.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Moses H, 3rd, Matheson DH, Cairns-Smith S, et al. The anatomy of medical research: US and international comparisons. JAMA 2015;313:174–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearb Med Inform 2000:65–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, et al. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health 2009;36:24–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports; no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carroll JK, Pulver G, Dickinson LM, et al. Effect of 2 clinical decision support strategies on chronic kidney disease outcomes in primary care: A cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e183377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NIH Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory. About NIH Collaboratory. National Institutes of Health. Online document at: http://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/about-nih-collaboratory/, accessed September3, 2020

- 7. National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Cancer (TIDIRC) facilitated course. Online document at: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/training-education/tidirc/index.html, accessed September11, 2020

- 8. Fogarty International Center. Toolkit Part 1: Implementation science methodologies and frameworks. Online document at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/About/center-global-health-studies/neuroscience-implementation-toolkit/Pages/methodologies-frameworks.aspx, accessed September11, 2020

- 9. Fogarty International Center. Implementation Science news, resources and funding for global health researchers. Online document at: https://www.fic.nih.gov/ResearchTopics/Pages/ImplementationScience.aspx, accessed September8, 2020

- 10. National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Implementation Science. Online document at: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/, accessed September11, 2020

- 11. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Online document at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/, accessed September11, 2020

- 12. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Recommendations. Online document at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/, accessed September11, 2020

- 13. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly Jet al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: A systematic review for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ghildayal N, Johnson PJ, Evans RL, Kreitzer MJ. Complementary and alternative medicine use in the US adult low back pain population. Glob Adv Health Med 2016;5:69–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Stussman BJ. Expenditures on complementary health approaches: United States, 2012. Natl Health Stat Report 2016:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Humphreys K, McLellan AT. A policy-oriented review of strategies for improving the outcomes of services for substance use disorder patients. Addiction 2012;106:2058–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Disparities Report 2011. March 2012. Online document at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr11/nhdr11.pdf, accessed September14, 2020

- 19. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid Access in Brief: Adults' Experiences in Obtaining Medical Care. Washington, DC: MACPAC, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US), 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keosaian JE, Lemaster CM, Dresner D, et al. “We're all in this together”: A qualitative study of predominantly low income minority participants in a yoga trial for chronic low back pain. Complement Ther Med 2016;24:34–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stussman BJ, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Ward BW. U.S. physician recommendations to their patients about the use of complementary health approaches. J Altern Complement Med 2020;26:25–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, et al. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: Current and future directions. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1274–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Proctor EK, Powell BY, Baumann AA, et al. Writing implementation research grant proposals: Ten key ingredients. Implementation Sci 2012;7:96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Ann Rev Public Health 2017;38:1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Sci 2015;10:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tabak RG, Khoong, E, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:1873–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strifler L, Cardoso R, McGowan J, et al. Scoping review identifies significant number of knowledge translation theories, models, and frameworks with limited use. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;100:92–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. CFIR Research Team, Center for Clinical Management Research. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Online document at: https://cfirguide.org/, accessed September21, 2020

- 31. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, et al. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: Diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci 2019;14:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res 2020;283:112629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences. Qualitative methods in implementation science. Online document at: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-09/nci-dccps-implementationscience-whitepaper.pdf, accessed December3, 2020

- 35. Leeman J, Teal R, Jernigan J, et al. What evidence and support do state-level public health practitioners need to address obesity prevention. Am J Health Promot 2014;28:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nilsson G, Hansson K, Tiberg I, Hallström I. How dislocation and professional anxiety influence readiness for change during the implementation of hospital-based home care for children newly diagnosed with diabetes—An ethnographic analysis of the logic of workplace change. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith JD, Hasan M. Quantitative approaches for the evaluation of implementation research studies. Psychiatry Res 2020;283:112521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Res 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, et al. Mixed method designs in implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:44–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mazzucca S, Tabak RG, Pilar M, et al. Variation in research designs used to test the effectiveness of dissemination and implementation strategies: A review. Front Public Health 2018;6:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miller CJ, Smith SN, Pugatch M. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs in implementation research. Psychiatry Res 2020;283:112452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50:217–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wyman PA, Henry D, Knoblauch S, Brown CH. Designs for testing group-based interventions with limited numbers of social units: The dynamic wait-listed and regression point displacement designs. Prev Sci 2015;16:956–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Venkataramani AS, Bor J, Jena AB. Regression discontinuity designs in healthcare research. BMJ 2016;352:i1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): New methods for more potent eHealth interventions. Am J Prev Med 2007;32(5 Suppl):S112–S118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. National Cancer Institute. Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs (EBCCP). Online document at: https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/index.do, accessed December3, 2020

- 47. Taylor SL, Bolton R, Huynh A, et al. What should health care systems consider when implementing complementary and integrative health: Lessons from Veterans Health Administration. J Altern Complement Med 2019;25(S1):S52–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Parman C. Coding complementary and alternative medicine. Oncol Issues 2018;33:9–12 [Google Scholar]