Abstract

Purpose of review

Despite increased survivorship and the subsequent need for chronic management of cancer, the association of self-management and palliative care is still emerging within cancer care. Routine and timely use of self-management strategies in the palliative setting can help reduce self-management burden and maximize quality of life. In this review, we consider the complementary relationship of self-management and palliative care and how they support living with cancer as a chronic illness.

Recent findings

Recent studies provide evidence of support among patients, family caregivers and healthcare professionals for integration of self-management interventions into palliative cancer care. As a guiding framework, components of the revised Self and Family Management Framework correspond to the provision of palliative care across the care trajectory, including the phases of curative care, palliative care, end-of-life care and bereavement. Additional work among self-management partners facing cancer and other life-limiting illnesses, that is patients, family caregivers and healthcare professionals, would be useful in developing interventions that incorporate self-management and palliative care to improve health outcomes.

Summary

There is an increasing acceptance of the complementarity of self-management and palliative care in cancer care. Their integration can support patients with cancer and their family caregivers across the care trajectory.

Keywords: cancer, chronic illness, framework, palliative, self-management

INTRODUCTION

Self-management refers to the activities in which a patient and their family caregivers collaborate to manage symptoms, treatments, lifestyle changes and psychosocial, cultural and spiritual consequences of the patient’s illness [1]. Improved treatments have extended survivorship for cancer, making it a chronic illness requiring self-management at home. Consequently, self-management support is critical for patients and family caregivers [2▪▪]. Routine use of self-management strategies and timely use of palliative care can reduce self-management burden and maximize quality of life, yet, the combination of self-management and palliative care is not widely recognized [3▪▪]. We review evidence supporting the complementarity of self-management and palliative care, as well as the revised Self and Family Management Framework (SFMF). Although we use the term, ‘self-management’, we note that self-management is performed by patients and family caregivers and is more completely termed ‘self- and family management’.

SHARED PRINCIPLES OF SELF-MANAGEMENT AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Several principles are central to self-management [4]. An overarching principle is improving quality of life through management of symptoms and physical and psychosocial consequences of chronic illness to improve wellbeing. Improved quality of life is related to patients shifting from a perspective of illness to health [5] by keeping the health perspective in the foreground of illness management. The health perspective is achieved through proactive self-management of physical and emotional aspects of illness and a focus on health promotion. In performing self-management, there is an interconnectedness of patient and family roles as illustrated in the SFMF: family can be a risk and protective factor (e.g. family structure) influencing patient self-management (e.g. decision-making) [6]. Patient and family education in self-management, knowledge of their individual and interactive roles and self-efficacy to perform roles are integral to self-management. Patient-family caregiver-provider relationships are likewise central, with finding the right provider and establishing good communication being facilitators of self-management [7▪]. Among the many self-management activities, identifying and setting goals and decision-making and problem-solving are core self-management skills that underlie other self-management activities such as medication management and advance care planning. Self-management is also an ongoing and dynamic process, with overlap of skill development and performance of self-management skills [8].

These principles of self-management are also central to palliative care per the World Health Organization definition of palliative care, which includes quality of life for patients and their families facing life-threatening illness, prevention and relief of suffering, affirmation of life, support for patients and their families, use of a team approach, and early and ongoing application over the course of illness [9]. Palliative care advocates taking care of the person as well as the disease. This integrative approach is supported in cancer care [10,11,12▪]. The goals and activities of self-management and palliative care are well aligned and reflect a conceptual connection with applications to cancer and other serious, chronic conditions.

STUDIES DEMONSTRATING INTEGRATION OF SELF-MANAGEMENT AND PALLIATIVE CARE

Several reviews support the effectiveness of self-management interventions in improving quality of life outcomes in cancer [13▪▪–16▪▪]. A PubMed literature search of articles from the past two years using the terms ‘self-management’, ‘palliative care’, ‘cancer’ and ‘support’ yielded quantitative [17▪–20▪] and qualitative [21▪–25▪] studies that validate the uptake of self-management in the palliative setting for adult patients with cancer (Table 1). Interventions target various aspects of self-management (e.g. self-efficacy, symptom management, health communication), using various delivery modes, including by nurses in person or by telephone, self-guided and eHealth, including web-based and mobile applications. The interventions we identified focus on self-management, are patient-centered, and incorporate essential elements of palliative care such as goal-setting and decision-making. In these select articles, improvement was demonstrated in self-management and health outcomes such as symptom management and burden, function, knowledge of care options, desired role in self-management and caregiver stress.

Table 1.

Studies demonstrating integration of cancer self-management in the palliative setting

| Theme | Ref. | Year | Country | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention studies | Koller et al. [17▪] | 2017 | Germany | The Anti-Pain intervention, composed of information, skill building and nurse coaching and delivered in-hospital and by telephone, was effective in improving function and self-efficacy among adult oncology inpatients of a palliative care consultation service. |

| Schulman-Green and Jeon [18▪] | 2017 | United States | The Managing Cancer Care: A Personal Guide intervention, composed of self-guided modules on self-management and goal-setting, care options, communication with clinicians and family caregivers, transitions, self-efficacy and symptom management, produced significant improvements in knowledge of care options and desired role in self-management among women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. | |

| Hochstenbach et al. [19▪] | 2016 | The Netherlands | A mobile and web-based intervention co-used by outpatients with moderate to severe cancer pain and registered nurses was reported as highly learnable, usable and desirable by patients. Nurses reported some challenges but were enthusiastic about and supportive of patient self-management. | |

| Steel et al. [20▪] | 2016 | United States | A web-based collaborative care intervention including a psychoeducational self-management website (symptom information/recording, journaling, chat room, audiovisual library, resource library) and a collaborative care coordinator skilled in cognitive behavioural therapy and psycho-oncology reduced depression, pain and fatigue and improved quality of life among patients, and reduced caregiver stress and depression. | |

| Qualitative studies | Cooley et al. [21▪] | 2017 | United States | Although patients desire face-to-face communication with clinicians about their cancer care, nominated components for an eHealth system to support patient-clinician communication included ability to track symptoms over time, access to web-based information, decision-support on when to call clinicians, peer support and access to medical records. Caregiver support to process copious cancer care information is essential. |

| Lie et al. [22▪] | 2017 | Norway | A shared care model involving oncologists, general practitioners and patients may best address patient needs. Patient education about late effects of cancer and follow-up care would support patient self-management. | |

| Slev et al. [23▪] | 2017 | The Netherlands | Nurses value self-management support for patients and family caregivers managing advanced cancer. Psychological support may be regarded as secondary to physical support but is an important aspect of palliative care. Collaborative goal-setting, follow up on self-management plans and support for informal caregivers require more attention. eHealth has advantages but was not felt to be a substitute for in-person care. | |

| Hughes et al. [24▪] | 2016 | England | Specialist palliative care professionals support patient self-management of advanced cancer pain, believing that it is desirable for patients to have some control over their pain and that self-management of pain is achievable when patients take ownership and are motivated. Patients’ self-management of pain could be problematic but improving patient knowledge and patient-clinician collaboration supports patient self-management. | |

| Stacey et al. [25▪] | 2016 | Canada | In tracking uptake of the pan-Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) protocols for nurse-delivered, telephone-based support of patient self-management of symptoms, nurses, patients and family members reported that protocol use could improve consistencies across clinical settings in guiding patient self-management. |

Three of the four intervention studies [17▪,19▪,20▪] addressed cancer pain. Hochstenbach et al. [19▪] demonstrated that patients’ pain could be monitored and feedback given with education and advice through a mobile device. Nurses supported patients remotely through a web application. Steel et al.’s [20▪] intervention included a website incorporating written and visual self-management strategies to reduce pain, depression, fatigue and improve health-related quality of life. Patients randomized to the intervention group were seen by a care coordinator during physician visits, with telephonic follow-up every 2 weeks. These results show promise in helping patients and their family caregivers gain access to resources through the web.

Participants in the qualitative studies included patients, family caregivers and healthcare professionals. Participants reported challenges with the learning curve in self-management education, the definition of self-management roles, variation in self-management skill level, and perhaps most significantly, high physical and emotional distress. However, despite high burden, patients were willing to engage in self-management to learn about their cancer care, to have some control over symptoms and other aspects of their illness and to work collaboratively on self-management with family caregivers and healthcare professionals. Participants were receptive to different delivery modes of self-management support and were enthusiastic about eHealth options to enhance self-management and increase access to self-management support [21▪,23▪]. Additional work is needed to support family caregivers in their dual role of enabling cancer self-management and engaging in family management, particularly during end-of-life and bereavement phases. These recent studies, hailing from a range of countries, demonstrate increasing global recognition of the relevance of self-management and palliative care in cancer care.

INTEGRATION OF CANCER SELF-MANAGEMENT INTO PALLIATIVE CARE OR VICE VERSA?

A consideration in the relationship of self-management and palliative care is which comes first. Is self-management to be integrated into palliative care, or is palliative care to be integrated into self-management? The critical consideration is where the patient presents on the care trajectory. A healthy patient may be self-managing effectively and only later need to integrate palliative care into the self-management plan, while a patient receiving palliative care may need to integrate new self-management strategies into their care. Different self-management practices, facilitators and barriers may be salient during curative, palliative-focused, end-of-life and bereavement phases of care [26▪,27▪,28▪▪]. Patients’ and oncologists’ perceptions of the content of goals of care conversations vary over time [29▪]. More research is needed on how self-management may vary by phase of disease; however, as multiple studies support early palliative care in cancer for patients [30▪▪] and family caregivers [31▪▪,32▪▪], it makes sense for self-management to also begin early and be tailored by phase of disease to ensure appropriate self-management over time.

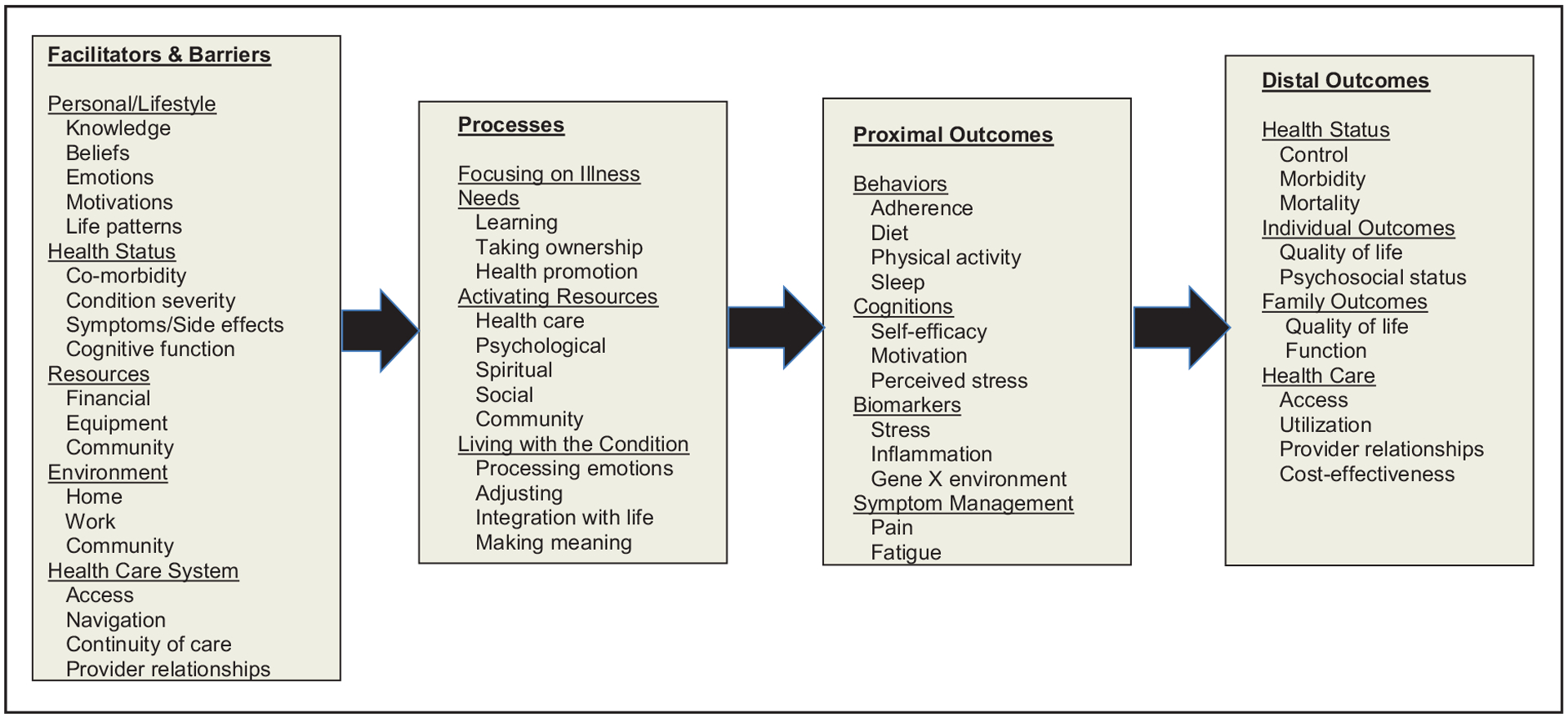

THE SELF AND FAMILY MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK AS AN ORGANIZING FRAMEWORK

The SFMF was created to guide research advancing self-management science [6]. The original version illustrated factors influencing self-management and potential outcomes. Individual and family self-management were depicted as interactive and as impacting health, patient, family and environmental outcomes. The SFMF was revised [33] (Fig. 1) based on emerging research on processes of and factors affecting self-management [7▪,8]. The revised SFMF details self-management processes, proximal and distal outcomes, and facilitators and barriers that may influence self-management abilities and outcomes.

FIGURE 1.

The revised Self and Family Management Framework. The revised Self- and Family Management Framework outlines facilitators and barriers to self-management, processes of self-management, proximal outcomes and distal outcomes and their relationships. Reproduced with permission from [33].

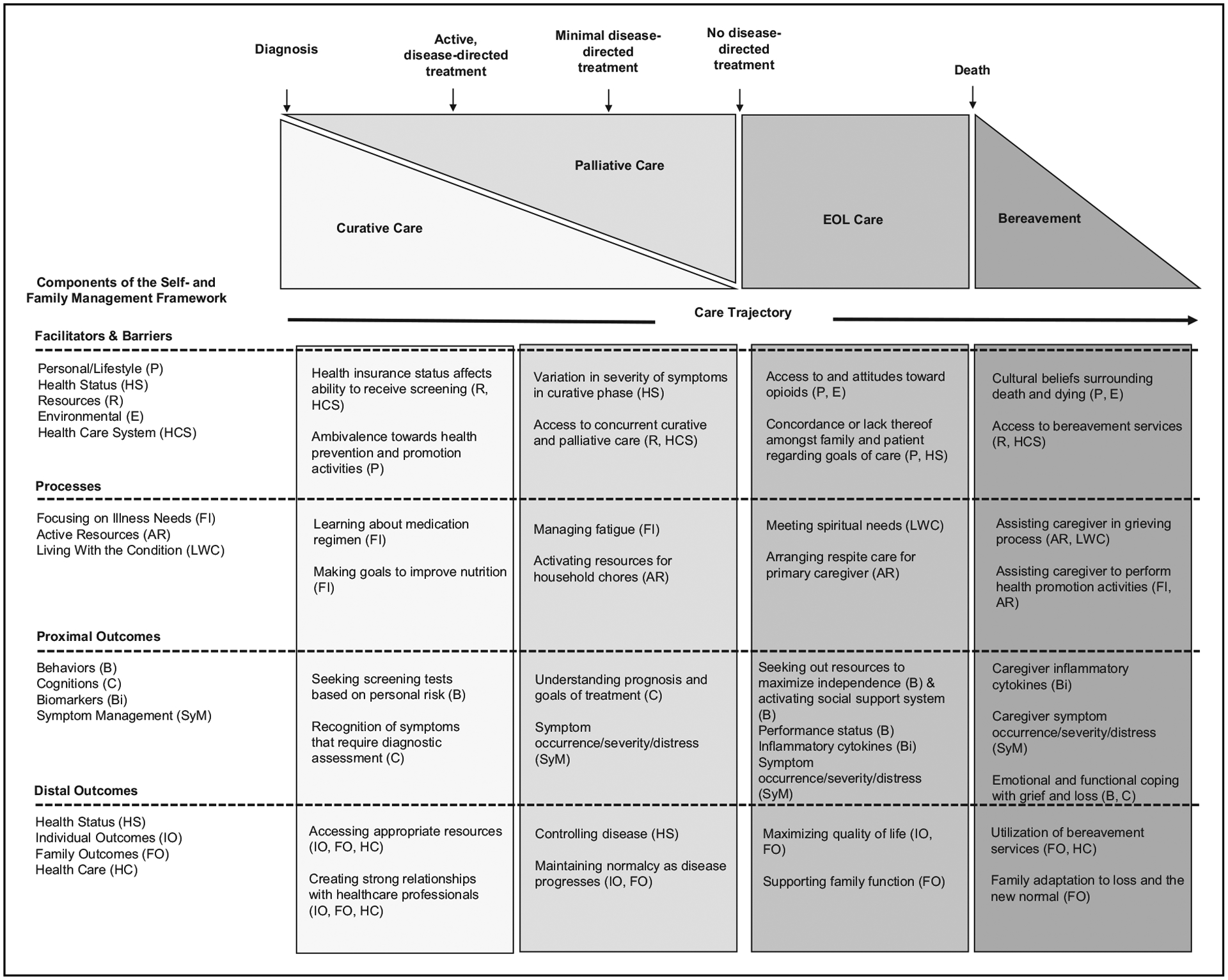

Components of the SFMF can be aligned with the provision of palliative care across the care trajectory (Fig. 2) [34]. The care trajectory spans overlapping phases of care, beginning with diagnosis and proceeding to the curative phase of care, a time of active, disease-directed treatment. The curative phase is concurrent with the palliative phase, during which efforts focus on disease control versus cure, on pain and symptom management, and on psychosocial and spiritual support. The curative and palliative phases have an inverse relationship, whereas the focus on curative efforts lessens, the focus on palliative care increases. The end-of-life phase is marked by comfort care only and is followed by the bereavement phase. In the following section, we review how components of the SFMF are expressed in each of these phases.

FIGURE 2.

Self and family management across the care trajectory. This figure illustrates how components of the Self and Family Management Framework, including Facilitators and Barriers, Processes, Proximal Outcomes and Distal Outcomes can be aligned with provision of palliative care across the care trajectory. Examples of self-management activities by phase of care are provided. Adapted from [34].

Facilitators and barriers

Facilitators and barriers to self-management include personal/lifestyle, health status, resources, environmental and healthcare system factors that are associated with self-management of chronic conditions [7▪]. These factors play an integral role in determining how effective self-management is and what interventions are indicated. They are at the core of patient-centred palliative care. Throughout palliative care, from the curative phase to hospice and end-of-life care, it is vital to examine facilitators and barriers in the initiation and maintenance of self-management. For instance, the sicker a patient gets (health status), the more self-management is required; yet, symptom severity can significantly affect the patient’s ability to self-manage, thereby increasing family responsibility [3▪▪]. In addition, patients may not recognize or may deny the severity of their disease and symptoms, which is a barrier to effective self-management. Palliative care can facilitate prognostic awareness, allowing patients to self-manage in a way that improves quality of life and decision-making while reducing family caregiver stress and depression [35▪▪].

Financial resources can also affect this dynamic, for example in the ability to hire a home health aide. Access to care (e.g. insurance) can affect ability to self-manage. Palliative care can help patients to better access care that meets their needs, reducing financial strain and unmet care needs [36]. Personal beliefs and the lived environment may affect the willingness of the patient or family to accept help.

Processes

Processes of self-management include focusing on illness needs, activating resources and living with a chronic illness [8]. When focusing on illness needs, patients and family caregivers may be learning about the illness, taking ownership of health needs and performing health promotion activities to optimize health. Activating resources involves putting into place the healthcare, psychological, spiritual and social resources integral to optimal self-management. Living with a chronic illness involves processing emotions, adjusting, integrating the illness into daily life and meaning making. These processes vary in intensity and complexity depending on the illness trajectory and the role that patients and family caregivers can assume in managing the illness.

During the curative phase, self-management efforts for patients and family caregivers are directed towards addressing illness needs, preventing complications and maintaining health. As the patient shifts from the curative to the palliative phase, prioritization of self-management tasks and skills may shift, for example less emphasis on health promotion activities and more on symptom management. Thus, during the palliative phase, patients and families may need to activate different resources to meet changing needs.

During the end-of-life phase, self-management priorities will shift dramatically. Symptom management and comfort care become a priority. Various resources are necessary to meet the physical, emotional and spiritual needs of the patient and family. Meaning making may heighten as the end of life nears. Among adults with advanced cancer, the transition from curative to palliative care has been reported as difficult [37▪▪]. During treatment, patients strove for a sense of normalcy, engaging in self-management and maintaining hope. Patients at the end of life reported optimizing coping, acknowledging self-limitations and impending death, needing better symptom management and experiencing profound exhaustion and helplessness. During the bereavement phase, the family caregiver becomes the central care recipient. Skills and knowledge learned by family caregivers can also be used for themselves. Thus, different self-management interventions are needed across the care trajectory.

Proximal outcomes

Proximal outcomes are the concepts or variables that mediate change in the distal, or long-term, self-management outcomes. Proximal outcomes are indicators of how well a patient has navigated the processes of self-management. Several proximal outcomes are described in the SFMF, including behaviours, cognitions, biomarkers and symptom management. In the context of palliative care, proximal outcomes can look very different at different phases of care.

Examples of behaviours and cognitions to consider include engagement in life, health-directed behaviours [38▪], skill and technique acquisition, health service navigation and social integration and support [39]. These outcomes can be evaluated at all phases of palliative care; however, the specifics of these behaviours and cognitions can vary across phases. For example, in early palliative care when the emphasis is on curing and/or controlling disease, behaviours and cognitions that demonstrate an understanding of the chronicity of the diagnosis and the expected disease trajectory are key proximal outcomes. When care shifts to being more palliative, behaviours and cognitions such as seeking out resources to maximize independence in the context of declining performance status [40▪] should be considered. At the end of life, behaviours and cognitions of interest may shift to those of the family caregiver, such as their ability to activate social support.

There are likewise expected variations across the care trajectory regarding biomarkers and symptom management. Symptoms and symptom management are outcomes that can be improved when increased survival may not be a realistic outcome; however, symptom monitoring has been shown to impact survival in metastatic cancer [41▪▪]. Symptoms can be measured across multiple dimensions, including prevalence, occurrence, severity, distress from individual symptoms or total symptom burden [42▪], or symptom interference. These concepts are potentially useful proximal outcomes across all phases of care.

Distal outcomes

Distal outcomes include health status, individual and family outcomes, and healthcare outcomes, and represent ultimate self-management aims. Distal outcomes largely align with palliative care outcomes across the care trajectory. Outcomes related to health status include disease control, morbidity and mortality. Control of disease is a key outcome once cure is not an option and recedes in importance towards the end of life [43▪▪]. Reducing morbidity is a desired outcome in terms of minimizing disease effects [44▪,45▪▪]. Palliative care may influence mortality to the extent that its early introduction into self-management can increase survival [30▪▪].

Individual and family outcomes of quality of life, psychosocial status and family function remain imperative self-management outcomes across the care trajectory [46▪,47▪]. Perceptions of what constitutes quality of life may shift over time [48▪]. For example, early in the palliative phase, maintaining employment may be an important quality of life indicator, while later being pain-free may be a patient priority, and lowered anxiety a family caregiver priority. Psychosocial status is relevant across the care trajectory as psychosocial needs, including emotional and social well being, are high, and how they are managed affects other care and symptom outcomes. For example, among individuals with head and neck cancer, one study found that depression, resilience and social support affected communication [49▪]. Family functioning is likewise a salient outcome across phases of care, extending into bereavement as the family must endure following patient death [50▪▪].

UTILITY OF THE SELF AND FAMILY MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK TO SUPPORT CANCER SELF-MANAGEMENT

Self-management interventions that are grounded in the SFMF may impact clinical changes, particularly around emphasis on patient and family caregiver education, so they understand their respective roles in self-management and can actively self-monitor. Healthcare professionals may use components of the SFMF in different ways, for example for assessment purposes to identify facilitators and barriers to self-management, self-management processes that may benefit patients and family caregivers and self-management outcomes important to them. Such assessments can drive treatment goals, spur learning and skill development, and help determine activation of resources.

CONCLUSION

Self-management and palliative care are integral components of cancer care that together can support patients and family caregivers across the care trajectory. The SFMF may be used to guide related research and clinical practice. Continued focus on the integration of self-management and palliative care in cancer care would be useful in developing and implementing interventions that improve cancer outcomes.

KEY POINTS.

Despite their alignment, integration of self-management and palliative care has not been well recognized.

Routine and timely use of self-management strategies in the palliative setting can help reduce self-management burden and maximize quality of life.

Evidence to support the linkage of self-management and palliative care is growing and gaining global recognition.

The Self and Family Management Framework may be used to guide research addressing self-management in the palliative setting.

Additional work is needed to develop interventions that integrate self-management and palliative care to support patients with cancer and their family caregivers across the care trajectory.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank David Collett, APRN, for his assistance with Fig. 2.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

- 1.Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Schol 2011; 43:255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.▪▪.Howell DD. Supported self-management for cancer survivors to address long-term biopsychosocial consequences of cancer and treatment to optimize living well. Curr Opinion Supp Pall Care 2018; 12:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of supported self-management programmes that enable cancer survivors to optimize health. This study not only provides evidence for self-management in cancer care but also suggests the need for standardization of self-management programmes to improve investigation of long-term health outcomes.

- 3.▪▪.Thorne S, Roberts D, Sawatzky R. Unravelling the tensions between chronic disease management and end-of-life planning. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2016; 30:91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important discussion of chronic illness as potentially life-limiting and therefore as appropriate for integration of palliative care. This study advocates a critical shift in conceptualization of chronic illness and healthcare delivery.

- 4.McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61:50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson BL. The koala has claws: applications of the shifting perspectives model in research of chronic illness. Qual Health Res 2003; 13:987–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grey M, Knafl K, McCorkle R. A framework for the study of self- and family management of chronic conditions. Nurs Outlook 2006; 54:278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.▪.Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Park C, et al. A metasynthesis of factors affecting self-management of chronic illness. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72:1469–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of qualitative literature that identified facilitators and barriers to patient self-management of chronic illness. Findings were later used to revise the SFMF.

- 8.Schulman-Green D, Jaser S, Martin F, et al. Processes of self-management in chronic illness. J Nurs Schol 2012; 44:136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. [Accessed 5 April 2018].

- 10.Zollman C, Walther A, Seers HE, et al. Integrative whole-person oncology care in the UK. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2017; 52:26–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polley MJ, Jolliffe R, Boxell E, et al. Using a whole person approach to support people with cancer: a longitudinal, mixed-methods service evaluation. Integr Cancer Ther 2016; 15:435–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.▪.Armstrong K, Lanni T Jr, Anderson MM, et al. Integrative medicine and the oncology patient: options and benefits. Support Care Cancer 2018; 26:2267–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes components of integrative medicine that support whole-person oncologic care.

- 13.▪▪.Howell D, Harth T, Brown J, et al. Self-management education interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25:1323–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study synthesizes evidence of self-management education interventions to improve symptoms and quality of life and describes the need to identify ‘core components’ of cancer self-management education to ensure consistent and effective cancer self-management support.

- 14.▪▪.Smith-Turchyn J, Morgan A, Richardson J. The effectiveness of group-based self-management programmes to improve physical and psychological outcomes in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2016; 28:292–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study compared physical and psychological outcomes among patients with cancer who did or did not participate in group self-management programs. It discusses problems in defining/labelling self-management programmes and determining ‘active ingredients’.

- 15.▪▪.Kim SH, Kim K, Mayer DK, et al. Self-management intervention for adult cancer survivors after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2017; 44:719–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review supporting the use of self-management interventions as a nursing intervention to improve health-related quality of life. This study discusses limitations of self-management interventions to address psychological outcomes as well as difficulties in comparing studies due to heterogeneity.

- 16.▪▪.Ugalde A, Haynes K, Boltong A, et al. Self-guided interventions for managing psychological distress in people with cancer: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2017; 100:846–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study explored evidence for use of self-guided cancer self-management interventions, finding short-term effects. It also suggests the need to identify the ideal delivery point in the disease trajectory, which patient group(s) will benefit, and optimal intervention content and delivery mode.

- 17.▪.Koller A, Gaertner J, De Geest S, et al. Testing the implementation of a pain self-management support intervention for oncology patients in clinical practice. Cancer Nurs 2017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A pilot randomized controlled trial of a self-management intervention focused on pain, which found improved function and self-efficacy among adult oncology inpatients of a palliative care consultation service.

- 18.▪.Schulman-Green D, Jeon S. Managing Cancer Care: a psycho-educational intervention to improve knowledge of care options and breast cancer self-management. Psychooncology 2017; 26:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A feasibility study of a psychoeducational intervention that found improved desired role in self-management and improved knowledge of palliative care among women with nonmetastatic breast cancer.

- 19.▪.Hochstenbach LMJ, Zwakhalen SMGV, Courtens AM, et al. Feasibility of a mobile and web-based intervention to support self-management in outpatients with cancer pain. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016; 2:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study established feasibility of an eHealth self-management intervention through high user ratings of learnability, usability, desirability and high completion rate.

- 20.▪.Steel JL, Geller DA, Kim KH, et al. Web-based collaborative care intervention to manage cancer-related symptoms in the palliative care setting. Cancer 2016; 122:1270–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study evaluated the efficacy of a collaborative care intervention targeting depression, pain, fatigue and quality of life among patients and family caregivers.

- 21.▪.Cooley ME, Nayak MM, Abrahm JL, et al. Patient and caregiver perspectives on decision support for symptom and quality of life management during cancer treatment: implications for eHealth. Psychooncology 2017; 26:1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study underscores the need for caregiver support of patients who may struggle with the complexities of cancer care, the potential of eHealth options as a means of informational support and the need for multiple modes of decision support.

- 22.▪.Lie HC, Mellblom AV, Brekke M, et al. Experiences with late effects-related care and preferences for long-term follow-up care among adult survivors of childhood lymphoma. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25:2445–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Long-term follow-up by and collaboration among specialists, general practitioners and patients is indicated to support self-management among adult survivors of childhood cancer.

- 23.▪.Slev VN, Pasman RW, Eeltink CM, et al. Self-management support and eHealth for patients and informal caregivers confronted with advanced cancer: an online focus group study among nurses. BMC Palliat Care 2017; 16:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Online focus groups with nurses revealed value of self-management support and eHealth for patients with advanced cancer.

- 24.▪.Hughes ND, Closs SJ, Flemming K, et al. Supporting self-management of pain by patients with advanced cancer: views of palliative care professionals. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24:5049–5057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An interesting description of the potential and pitfalls of patients’ self-management of cancer pain as reported by specialist palliative care professionals that may affect their integration of self-management into daily practice.

- 25.▪.Stacey D, Green E, Ballantyne B, et al. Implementation of symptom protocols for nurses providing telephone-based cancer symptom management: a comparative case study. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016; 13:420–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses uptake of symptom management protocols to support patient self-management of symptoms.

- 26.▪.Bennett MI, Mulvey MR, Campling N, et al. Self-management toolkit and delivery strategy for end-of-life pain: the mixed-methods feasibility study. Health Technol Assess 2017; 21:1–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes the patient-centred process of development of a self-management intervention with frank discussion of issues encountered and related solutions.

- 27.▪.Godfrey M, Price S, Long A, et al. Unveiling the maelstrom of the early breast cancer trajectory. Qual Health Res 2018; 28:572–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes how the ‘work’ of self-management may be different across the care trajectory.

- 28.▪▪.Kotronoulas G, Papadopoulou C, Burns-Cunningham K, et al. A systematic review of the supportive care needs of people living with and beyond cancer of the colon and/or rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017; 29:60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review classifies patients’ supportive care needs into a range of categories that underscores the need for multidisciplinary attention. Categories align with priorities in self-management and palliative care.

- 29.▪.Schulman-Green D, Smith CB, Lin J, et al. Oncologists’ and patients’ perceptions of initial, intermediate, and final goals of care conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 55:890–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes how desired content and timing of goals of care conversations may change over time with implications for self-management plans.

- 30.▪▪.Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 6:CD011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of the evidence for introduction of early palliative care that includes seminal studies in the area. This study found that although early palliative care interventions may be most, if mildly, effective among patients with advanced cancer, improvements may be clinically relevant for this group who experiences worsening quality of life.

- 31.▪▪.McDonald J, Swami N, Pope A, et al. Caregiver quality of life in advanced cancer: qualitative results from a trial of early palliative care. Palliat Med 2018; 32:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study emphasizes the inter-relatedness of patient and caregiver experiences of cancer. This study highlights the need for self-management and palliative care interventions that address both groups.

- 32.▪▪.McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B, et al. Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: cluster randomised trial. Ann Oncol 2017; 28:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study extends earlier work that has focused on effects of early integrated palliative care for patient to caregivers. It found positive effects of early intervention for cancer caregivers on caregiver satisfaction, but the authors were unable to determine effects on quality of life, suggesting the need for further investigation.

- 33.Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, et al. A revised self- and family management framework. Nurs Outlook 2015; 63:162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization: Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 804, 1–75. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.▪▪.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An important study evaluating the impact of early integrated palliative care in patients with newly diagnosed lung and gastrointestinal cancer. This study adds to the growing evidence on the benefits of integrating palliative care services earlier in the course of disease for patients with advanced cancer.

- 36.Brody AA, Ciemins E, Newman J, et al. The effects of an inpatient palliative care team on discharge disposition. J Palliat Med 2010; 13:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.▪▪.Dong ST, Butow P, Tong A, et al. Patients’ perspectives of multiple concurrent symptoms in advanced cancer: a semistructured interview study. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24:1373–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study provides rich qualitative data on the impact of patients’ having multiple concurrent symptoms and how this symptom burden negatively affects patient outcomes in the areas of autonomy, functioning and psychological status. The authors advocate for early integration of palliative care to facilitate self-management.

- 38.▪.Hagan TL, Cohen SM, Rosenzweig M, et al. The female self-advocacy in Cancer Survivorship Scale: a validation study. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 976–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A study describing the psychometric properties of a scale measuring the concept of self-advocacy in women with invasive cancer.

- 39.Elsworth GR, Osborne RH. Percentile ranks and benchmark estimates of change for the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: normative data from an Australian sample. SAGE Open Med 2017; 5:2050312117695716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.▪.Portz JD, Kutner JS, Blatchford PJ, et al. High symptom burden and low functional status in the setting of multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017; 65:2285–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes how high symptom burden is associated with decreased functional status in patients with advanced cancer and multiple comorbidities.

- 41.▪▪.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017; 318:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A RCT of a studying using patient-reported symptoms that demonstrated an increase in life-expectancy for patients with metastatic cancers.

- 42.▪.Mooney KH, Beck SL, Wong B, et al. Automated home monitoring and management of patient-reported symptoms during chemotherapy: results of the symptom care at home RCT. Cancer Med 2017; 6:537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Daily symptom monitoring and reporting along with nurse coaching for severe symptoms resulted in reduced symptom burden in patients receiving chemotherapy compared with enhanced usual care.

- 43.▪▪.Hopkins B, Gold M, Wei A, et al. Improving the transition to palliative care for patients with acute leukemia: a coordinated care approach. Cancer Nurs 2017; 40:E17–E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study explored the effectiveness of a supportive care plan programme to integrate palliative care and haematology among patients with acute myeloid leukaemia with the goal of improving patient understanding of treatment goals and associated communication. It discusses cancer centres’ vision for improved communication and decision making for patients with incurable disease.

- 44.▪.Odejide OO, Li L, Cronin AM, et al. Meaningful changes in end-of-life care among patients with myeloma. Haematologica 2018. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses high symptom burden among patients with myeloma and uses the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End-Results Medicare database to examine their hospice use. Results indicate an improvement in treatment, survival and end-of-life care in this population, but authors suggest the need for earlier goals of care discussions, bridge palliative care services and adjustment of the hospice model to support transfusion support.

- 45.▪▪.Tran K, Zomer S, Chadder J, et al. Measuring patient-reported outcomes to improve cancer care in Canada: an analysis of provincial survey data. Curr Oncol 2018; 25:176–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study advocates the use of patient-reported outcomes to examine and improve symptom burden over time. It also suggests system-level approaches such as increasing the number of cancer treatment sites that screen patients for symptoms, standardizing when and how frequently patients are screened, screening patients for symptoms during all phases of cancer care and assessing whether giving cancer care providers real-time patient-reported outcomes data lead to interventions that reduce symptom burden and improve patient outcomes.

- 46.▪.Song L, Dunlap KL, Tan X, et al. Enhancing survivorship care planning for patients with localized prostate cancer using a couple-focused mHealth symptom self-management program: protocol for a feasibility study. JMIR Res Protoc 2018; 7:e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study describes the protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial among patients with prostate cancer and their family caregivers to examine the feasibility of a survivorship care plan that integrates a symptom self-management mHealth programme into existing standardized care plans. The study illustrates the importance of addressing individual and family self-management outcomes around quality of life, symptom management, healthy behaviours and social support.

- 47.▪.Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 2018; 26:1585–1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A review of randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of self-management programme conducted with cancer survivors. This study illustrates the range of self-management outcomes over various time periods postdiagnosis.

- 48.▪.Tessier P, Blanchin M, Sébille V. Does the relationship between health-related quality of life and subjective well being change over time? An exploratory study among breast cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 2017; 174:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; An example of how self-management needs may change over time, in this case, social aspects of health-related quality of life.

- 49.▪.Eadie T, Faust L, Bolt S, et al. Role of psychosocial factors on communicative participation among survivors of head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; A cross-sectional study of survivors of head and neck cancer that investigated the effects of the psychosocial factors of perceived social support, perceived depression and resilience on communicative participation, with the clinical recommendation to use these patient-reported outcomes to inform patient counselling and communication interventions.

- 50.▪▪.Hudson J, Reblin M, Clayton MF, et al. Addressing cancer patient and caregiver role transitions during home hospice nursing care. Palliat Support Care 2018; 15:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study discusses role changes among patients and family caregivers during advancing illness and the need to negotiate conflicts (patient independence and patient and caregiver emotions) due to these transitions to achieve higher quality patient care and improved caregiver adjustment. Authors suggest that that nursing support in the form of problem-solving, mediating, leading discussions about conflicts, validating and reassuring can help facilitate these transitions, and that learning mediation skills should be part of nursing education.