SUMMARY

An effective vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is an unrealized public health goal. A single dose of the prefusion-stabilized fusion (F) glycoprotein subunit vaccine (DS-Cav1) substantially increases serum-neutralizing activity in healthy adults. We sought to determine whether DS-Cav1 vaccination induces a repertoire mirroring the pre-existing diversity from natural infection or whether antibody lineages targeting specific epitopes predominate. We evaluated RSV F-specific B cell responses before and after vaccination in six participants using complementary B cell sequencing methodologies and identified 555 clonal lineages. DS-Cav1-induced lineages recognized the prefusion conformation of F (pre-F) and were genetically diverse. Expressed antibodies recognized all six antigenic sites on the pre-F trimer. We identified 34 public clonotypes, and structural analysis of two antibodies from a predominant clonotype revealed a common mode of recognition. Thus, vaccination with DS-Cav1 generates a diverse polyclonal response targeting the antigenic sites on pre-F, supporting the development and advanced testing of pre-F-based vaccines against RSV.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

A single dose of the prefusion-stabilized fusion (F) glycoprotein subunit vaccine (DS-Cav1) increases serum neutralizing activity in healthy adults. Mukhamedova et al. evaluated RSV F-specific B cell responses before and after vaccination and reveal that DS-Cav1 generates a diverse polyclonal response targeting the antigenic sites on pre-F, supporting the development and advanced testing of pre-F-based vaccines against RSV.

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) causes a large global health burden, particularly in young infant and elderly populations. Nearly everyone is infected with RSV by 2 years of age, and the most severe disease occurs in infants less than 6 months of age, with peak hospitalizations at 2–3 months of age (Graham, 2017). Despite decades of research and vaccine clinical trials, there are no licensed vaccines for RSV (Mazur et al., 2018). The RSV fusion (F) glycoprotein is a class I fusion protein that mediates viral entry by transitioning from a metastable prefusion conformation (pre-F) necessary to initiate viral entry into host cells to a stable post-fusion conformation (post-F). Pre-F preserves neutralization-sensitive sites that are not present on post-F and is therefore the preferred conformation for vaccine antigens. Because of the metastable nature of RSV F, most prior protein vaccines had antigenic properties consistent with post-F and have elicited relatively modest increases in serum neutralizing activity (Mazur et al., 2018; Ruckwardt et al., 2019). Recently, a structurally stabilized pre-F subunit vaccine, DS-Cav1, has been shown to elicit a more than 10-fold boost in serum neutralizing activity in a phase 1 study of healthy adults (Crank et al., 2019; McLellan et al., 2013), suggesting a higher potential to protect from RSV disease.

The major antigenic sites are defined by structural domains of pre-F. The apex contains sites Ø and V, which are present only on pre-F and targeted by highly potent RSV-neutralizing antibodies (Corti et al., 2013; Graham, 2017; McLellan et al., 2013; Mousa et al., 2017; Xiao et al., 2019), including the prophylactic site Ø antibody nirsevimab (Griffin, 2020). Other antigenic sites (I, II, III, and IV) are found on pre- and post-F, but the neutralizing potency of antibodies to these sites depends mainly on accessibility and avidity of binding to pre-F. Likewise, serologic studies have demonstrated that the majority of RSV F-specific serum neutralization can be competed with pre-F protein, although some serum neutralization may target the G glycoprotein (Ngwuta et al., 2015). The RSV F-specific repertoire in healthy adults (Gilman et al., 2016) and young children (Goodwin et al., 2018) established by natural infection is highly diverse, targeting at least six antigenic regions on RSV F. However, changes in the human antibody repertoire induced by vaccination have not been examined at the single-B cell level.

To determine whether pre-F vaccination induces a repertoire mirroring the pre-existing diversity from natural infection or whether certain antibody lineages targeting specific epitopes predominate, we performed repertoire analysis of RSV F-specific antibodies in six DS-Cav1-vaccinated individuals before and after vaccination. Using a combination of antigen-specific memory B cell sorting, paired heavy- and light-chain sequencing of plasmablasts, and unpaired heavy and light chain sequencing of naive and memory B cell transcripts, we identified and characterized 555 RSV F-specific antibody lineages. Our findings demonstrate that vaccination with DS-Cav1 boosts a diverse set of B cell lineages recognizing the pre-F conformation, targeting all known neutralization sites of RSV F.

RESULTS

Identification of RSV F memory B cells before and after DS-Cav1 vaccination

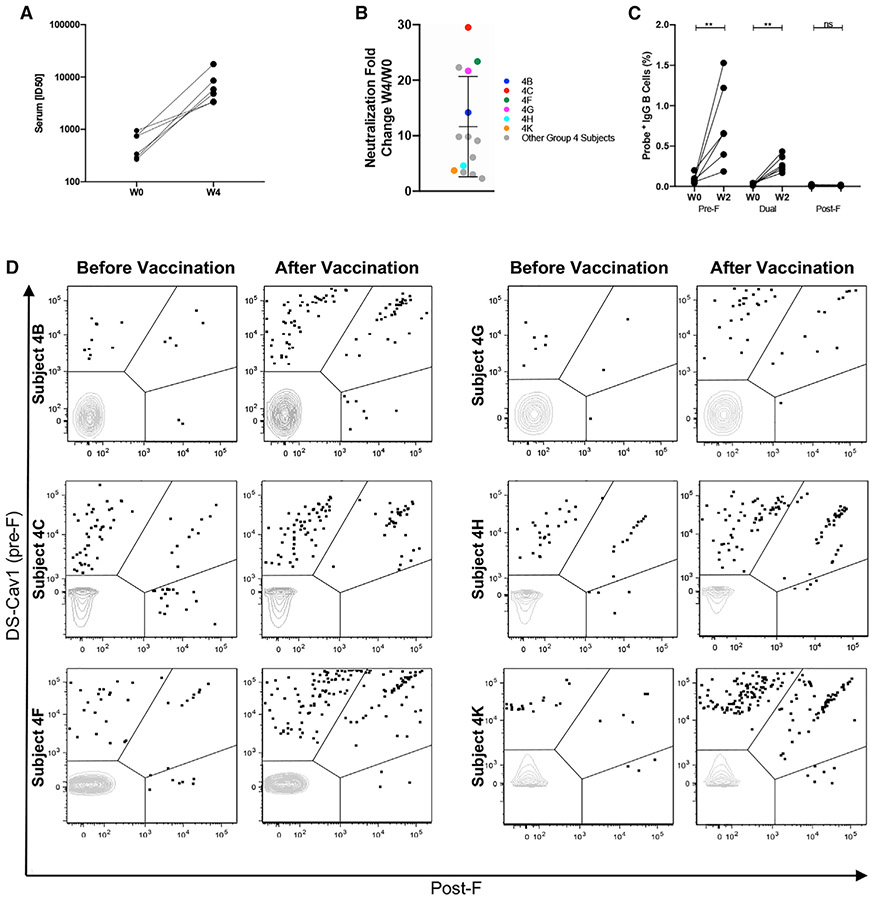

Six individuals were selected as representatives of the 15 subjects vaccinated with 150 μg of DS-Cav1 and alum adjuvant (Figures 1A and 1B). As expected, all six individuals had detectable serum neutralizing activity against RSV before vaccination because of natural infections (Figure 1A). Peripheral B cells from before and 2 weeks after vaccination were evaluated using fluorescently labeled pre-F and post-F probes (Figure S1A). Individual live CD19+ B cells that bound to a pre-F or post-F probe or were dually reactive were sorted for sequencing of the variable heavy (HV) and variable light (LV) chains. To focus on memory B cells, we excluded naive B cell sequences (immunoglobulin M [IgM]+/D+, CD27−) and sequences with somatic hypermutation (SHM) in the HV of 1% or less. DS-Cav1 immunization resulted in expansion of pre-F-reactive B cells (shown as B cells binding DS-Cav1 only or dually reactive) and a decreased proportion of B cells that bound only to the post-F probe (Figure 1D; Table S1). In addition, the frequency of IgG+ RSV F-specific B cells was higher after vaccination (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. RSV F memory B cells identified in DS-Cav1 vaccinees.

(A) Serum neutralization titers for six individuals vaccinated with 150 μg DS-Cav1 + alum. Titers are shown before vaccination (week 0) and 4 weeks after vaccination.

(B) Fold increase in serum neutralization titer 4 weeks after vaccination for all 15 subjects immunized with 150 μg DS-Cav1 + alum adjuvant. The six vaccinees studied in group 4 (4B, 4C, 4F, 4G, 4H, and 4K) are colored. Error bars indicate mean with standard deviation.

(C) The percentage of CD19+/CD27+ memory B cells with probe phenotype specified as pre-F-specific, dual, or post-F-specific before vaccination (week 0) and 2 weeks after vaccination. Statistical significance was determined using the Wilcoxon test.

(D) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) index plots for six vaccinees (before and 2 weeks after immunization) showing RSV F memory B cells reactive with the indicated fluorescently labeled probes DS-Cav1 or post-F. The x and y axes show MFI. Gate regions in each plot show B cells as pre-F-specific, dual, or post-F-specific binders.

Immune repertoire before and after vaccination

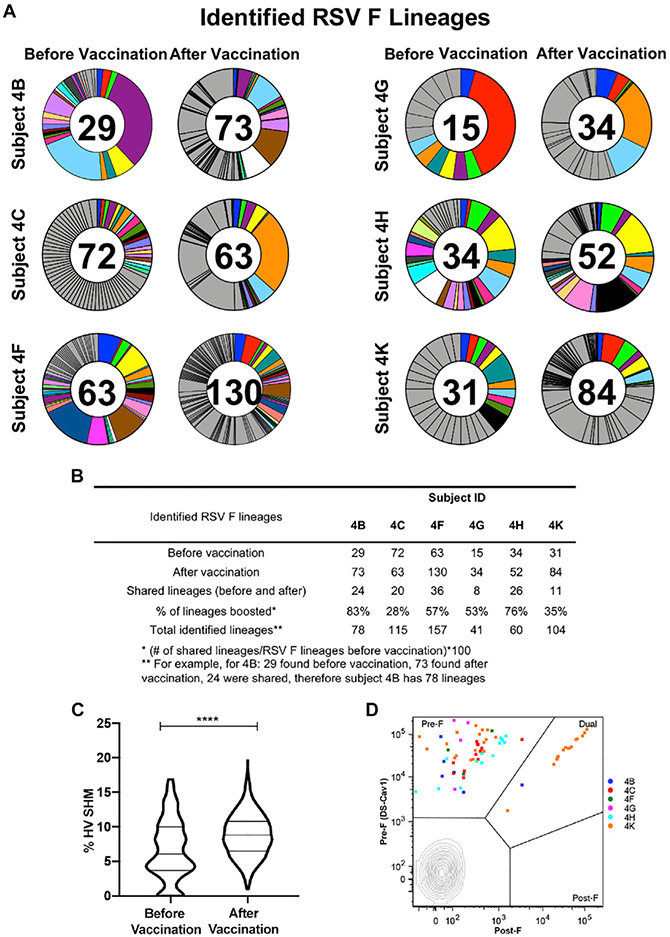

To gain insight into how the F-specific B cell repertoire changes following DS-Cav1 vaccination, we recovered and sequenced 857 heavy chains from probe-binding memory B cells obtained before and after vaccination (Figure S1A and S2). Sequences were evaluated to assign HV germline genes, identify the complementarity-determining region (CDR) H3 sequence, and calculate the percentage of SHM (Figure S2). The set of RSV F-specific lineages from each subject was defined from the sequences obtained from RSV F probe-binding B cells. We augmented this dataset with unpaired Illumina sequencing of bulk-sorted naive and memory B cells before and after vaccination (Figure S1B) and paired HV and LV (HV:LV) emulsion repertoire analysis of bulk-sorted plasmablasts 7 days after vaccination (DeKosky et al., 2013; Figure S1C). The Clonify algorithm (Briney et al., 2016) was used to identify clonally related sequences within the augmented dataset. For each of the six vaccinees, more lineages were identified after vaccination (34–130) than before vaccination (15–72) (Figure 2A). Vaccine-boosted RSV F memory B cell lineages, defined as those identified after DS-Cav1 vaccination that were also observed prior to vaccination, were found in all subjects and ranged from 30%–80% of the lineages identified per subject. In total, 857 probe-sorted sequences were assigned 555 distinct RSV F lineages, of which 125 were present before and after vaccination (Figure 2B). Among these 125 boosted lineages, the median HV SHM percentage was 6.1% before vaccination and 8.8% after vaccination—a small but statistically significant increase (Figure 2C). As expected, almost all of the 125 lineages were derived from B cells reactive with pre-F only or were dually reactive with pre-F and post-F. We further analyzed the phenotype of the antigen-specific B cells from the top three clonally expanded memory lineages in each subject and observed that none of these were solely post-F reactive (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. DS-Cav1 boosts pre-existing B cell lineages that target prefusion sites.

(A) Circle plots show RSV F-specific B cell lineages identified before and after vaccination with DS-Cav1. Lineages were identified from probe-sorted memory B cell heavy-chain sequences and augmented with data from plasmablasts and unpaired NGS. Each slice of the plot represents a lineage, with slice size proportional to the number of sequences for the lineage. Some lineages were found before and after vaccination, as indicated by the same color for that subject. The value in the circle indicates the number of lineages found before or after vaccination for each subject. Gray slices represent remaining lineages found only before or after DS-Cav1 vaccination.

(B) Summary of RSV F-specific lineages. For each subject, the number of lineages identified before and after vaccination is shown. Shared lineages are those with sequences identified before and after vaccination. Total identified lineages are the number of distinct RSV F lineages per subject.

(C) Violin plots showing all sequences from shared (boosted) lineages in six subjects before (n = 299) or after (n = 1,639) vaccination. Percent nucleotide divergence from the inferred germline heavy chain gene (% HV SHM) is shown on the y axis. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Mann-Whitney nonparametric test with p < 0.0001.

(D) Probe-sorted RSV F binding memory B cells from the top three clonally expanded lineages per subject are overlayed on a flow plot (18 of 125 shared lineages). Probe-sorted sequences are colored by subject. The x and y axes show MFI and the indicated antigen-specific probe used. Gate regions in each plot show B cells as pre-F- or post-F-specific or dual binding.

DS-Cav1 induces potent pre-F-specific antibodies

Thirty-five unique antibodies from five subjects were expressed and functionally characterized (Tables 1 and 2). We expressed the most prevalent boosted lineages in each vaccine recipient based on the highest number of plasmablast sequence reads.

Table 1.

Potent RSV F-specific antibodies isolated from DS-Cav1-vaccinated individuals targeting pre-F- and dual-specific epitopes

| mAb | RSV F Antigenic Site |

RSV-F Probe Binding |

IC50 (ng/mL) |

IC80 (ng/mL) |

HV | HV SHM (%) |

CDRH3 | LV | LV SHM (%) | CDRL3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 317.4B.L020.02 | Ø | pre-F | 7 | 24 | IGHV1-69 | 10.1 | CATDGYEVWTDDGVPEFDYW | IGKV3-20 | 4.6 | CQKYGRSPIAF |

| 317.4B.L004.04 | Ø | pre-F | 2 | 5 | IGHV3-74 | 10.4 | CGRRDETVITLAGVGRDLDVW | IGKV2-28 | 3.1 | CMQDLQTPTF |

| 317.4B.L006.01 | Ø | pre-F | 2 | 5 | IGHV3-7 | 7.6 | CARDWSGYSFGYDAFDIW | IGLV3-1 | 6.1 | CQAWDRTAYVF |

| 317.4K.L042.01 | Ø | pre-F | 209 | 710 | IGHV3-23 | 7.6 | CAKDGFVVITSAGFGLFDPW | IGKV1-33 | 5.0 | CQQYENVPITF |

| 317.4K.L055.02 | Ø | pre-F | 3 | 12 | IGHV5-51 | 10.4 | CARQVGGVLVTTPPPWYYYGMDAW | IGKV1-39 | 11.8 | CQQSYDTPLTF |

| 317.4F.L076.01 | Ø | pre-F | 4 | 9 | IGHV7-4-1 | 10.4 | CATESSVGSLETLDYW | IGLV2-8 | 5.2 | CSSYAGWNKVVF |

| 317.4F.L076.02 | Ø | N/A | 3 | 6 | IGHV7-4-1 | 12.2 | CATESSVGSLETLDYW | IGLV2-8 | 7.6 | CSSYAGWNKVVF |

| 317.4F.L038.03 | Ø | pre-F | 5 | 10 | IGHV5-51 | 11.8 | CARQATQWGPGNGAFDVW | IGKV2-40 | 14.1 | CMQRKDFPAAF |

| 317.4F.L034.05 | Ø | pre-F | 5 | 10 | IGHV1-69 | 10.8 | CAARDEAITRAGVGRDDYW | IGKV2-28 | 3.4 | CMQALQTSFTF |

| 317.4G.L025.01 | Ø | pre-F | 37 | 106 | IGHV4-30-4 | 8.3 | CARGGWWVNTDPPYMDVW | IGKV1-5 | 5.4 | CHQYNGYFPTF |

| 317.4F.L034.01 | Ø | pre-F | 138 | 355 | IGHV1-69 | 5.9 | CAARDEAITSVGVGRDDYW | IGKV1-5 | 2.9 | CQQYNSHSTF |

| 317.4F.L081.01 | Ø | pre-F | 4 | 11 | IGHV7-4-1 | 5.2 | CGGYDSGGFDSW | IGLV3-25 | 9.3 | CQSGDSSGLLF |

| 317.4K.L031.01 | V | pre-F | 5 | 16 | IGHV3-9 | 11.1 | CARDAYISGSSTYYYGLDVW | IGKV3-15 | 7.1 | CQQYNTWPLSF |

| 317.4K.L030.01 | V | pre-F | 7 | 21 | IGHV3-9 | 8.7 | CVRDSHYFDNSGSYTYGLDVW | IGKV3-15 | 11.1 | CQQYNNWPLTF |

| 317.4K.L013.02 | V | pre-F | 8 | 23 | IGHV1-18 | 8.3 | CARAGAVGCRAEEPCDINDYW | IGKV1-5 | 5.0 | CQQYKGYWTF |

| 317.4K.L008.05 | V | pre-F | 7 | 24 | IGHV1-18 | 9.4 | CVRSPPAGILDFDSW | IGKV2-30 | 4.8 | CMQGTHWPPTF |

| 317.4K.L008.06 | V | pre-F | 7 | 24 | IGHV1-18 | 10.4 | CVRSPPAGILDFDSW | IGKV2-30 | 4.1 | CMQGTHWPPTF |

| 317.4K.L008.02 | V | pre-F | 10 | 27 | IGHV1-18 | 3.8 | CARSPPAGILTFDFW | IGKV2-30 | 6.1 | CMQGTHWPPSF |

| 317.4K.L009.01 | V | pre-F | 13 | 46 | IGHV1-18 | 8.7 | CVRDVPVTAAALFDVW | IGKV2-30 | 5.8 | CMQPTHWPLTF |

| 317.4G.L009.01 | V | pre-F | 7 | 14 | IGHV3-15 | 8.5 | CTTGPFSISWYRAHFDDLYYYMDVW | IGKV1-33 | 6.8 | CQQYDTLPLSF |

| 317.4G.L012.01 | V | pre-F | 8 | 20 | IGHV4-59 | 4.6 | CAEGPAPFDYW | IGLV3-19 | 4.7 | CNSRYSSGSHWVF |

| 317.4B.L017.03 | V | pre-F | 9 | 21 | IGHV1-18 | 9.7 | CARDPPAVAAAMFDFW | IGKV2-30 | 4.4 | CMQGIHWPWTF |

| 317.4B.L058.01 | V | pre-F | 7 | 21 | IGHV4-59 | 4.2 | CARLSSGGFDYW | IGLV3-25 | 4.3 | CQSVDSSGTYWVF |

| 317.4B.L036.17 | V | pre-F | 3 | 8 | IGHV3-30 | 9.4 | CARGPVRGSSYYFDYW | IGLV3-21 | 5.7 | CQVWDSGTDQVVF |

| 317.4K.L036.03 | III | dual | 13 | 41 | IGHV3-11 | 9.7 | CARHAGSPGYYFDYW | IGLV1-40 | 4.5 | CQSYDRSLGGWVF |

| 317.4K.L036.01 | III | dual | 8 | 37 | IGHV3-11 | 10.4 | CARHAGSPGYFFDYW | IGLV1-40 | 10.4 | CQSYDSSLGGWVF |

| 317.4F.L017.01 | II | dual | 147 | 822 | IGHV2-5 | 10.3 | CVHGSGYDWGDDWFDPW | IGKV1-17 | 3.2 | CLQHNIYPYTF |

| 317.4F.L083.01 | II | dual | 179 | 822 | IGHV3-48 | 15.6 | CAREMVLTNSEYYYGMDVW | IGLV3-1 | 3.9 | CQAWDSSLRVF |

| 317.4B.L035.01 | IV | dual | p.n. | p.n. | IGHV3-30 | 7.6 | CARGDSSTGRGYYFDYW | IGLV6-57 | 4.1 | CQSYDASNHVF |

| 317.4B.L016.01 | IV | dual | n.n. | n.n. | IGHV1-69 | 11.5 | CARVPILEGETTAQRLFGEGWFDPW | IGLV1-47 | 5.3 | CASWDDSLRGPLF |

| 317.4K.L026.01 | IV | dual | p.n. | p.n. | IGHV2-70 | 8.6 | CARQSLYDRGGYYLRYFDSW | IGKV1-39 | 8.6 | CQQSYTRFSF |

| 317.4K.L054.03 | IV | dual | 126 | 401 | IGHV5-51 | 10.1 | CTTHGGGDRAMVYGTW | IGKV1-16 | 9.3 | CQQYDTYPLIF |

| 317.4F.L013.01 | IV | dual | 19,44 | 10,870 | IGHV1-69 | 6.6 | CASRHSGSYSFDYW | IGLV2-14 | 3.1 | CASFTSSDTLYVF |

| 317.4G.L029.02 | IV | pre-F | 20 | 40 | IGHV3-15 | 9.9 | CTTGPFSISWYRAHFDDLYYYMDVW | IGKV1-33 | 8.2 | CQQYDTFPLSF |

| 317.4G.L029.01 | IV | pre-F | 15 | 36 | IGHV3-15 | 9.2 | CTTGPFSISWYRAHFDDLYYYMDVW | IGKV1-33 | 6.8 | CQQYDTLPPSF |

p.n., partial neutralization; n.n., no neutralization.

Table 2.

Previously published antibodies used as controls for neutralization assays

| mAb | RSV F Antigenic Site | IC50 (ng/mL) | IC80 (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| D25 | Ø | 5 | 145 |

| Palivizumab | II | 84 | 167 |

| 101F | IV | 126 | 394 |

All 35 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) displayed high-affinity binding to DS-Cav1, confirming the integrity of the probe-based identification of RSV F-specific B cells. Thirty-two of 35 mAbs displayed detectable neutralization; 26 antibodies neutralized at an IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) of less than 50 ng/ mL, and 21 were highly potent with an IC50 of less than 10 ng/ mL. We found that many of these clonally expanded antibodies target antigenic sites present only on pre-F: 12 antibodies to site Ø and 12 to site V. Two site Ø antibodies were about 2-fold more potent than D25 (317.4B.L004.04 and 317.4B.L006.01 in Tables 1 and 2). Antibodies also targeted antigenic sites present on pre- and post-F: two to site III, 2 to site II, and 7 to site IV. Two of seven antibodies targeting antigenic site IV did not bind post-F, possibly because of contacts with β22, as suggested previously (Gilman et al., 2016), or quaternary interactions with the tip of the β3-β4 hairpin or between α2-α3, as seen with MRK-1654 (Tang et al., 2019) and AM14 (Gilman et al., 2015).

We used biolayer interferometry (Octet) to determine the binding affinity of each expressed antibody to DS-Cav1 derived from RSV subtypes A and B (A2 and B18537) (Table S8). Two potent site Ø-directed antibodies (317.4B.L004.04 and 317.4B.L006.01) against RSV A2 did not bind to B18537 DS-Cav1. We also measured the affinity of each antibody to the subtype B version of DS-Cav1 (B18537) containing substitutions identified previously in circulating strains of RSV in antigenic site V (L172Q/S173L) and in antigenic site Ø (I206M/Q209R) (Bin Lu et al., 2019). The double mutation in antigenic site V attenuated binding (106- to 102-fold change in binding in comparison with B18537) for 7 site V-directed antibodies, fully ablated binding for 2, whereas 3 were unaffected. Furthermore, binding of 6 of 12 site Ø-target- ing mAbs was ablated by the two substitutions in antigenic site Ø (I206M/Q209R); for 4 of 12 site Ø-directed antibodies, the binding affinity was not affected. Binding of antibodies targeting antigenic sites (I, II, III, and IV) were not affected by these specific substitutions.

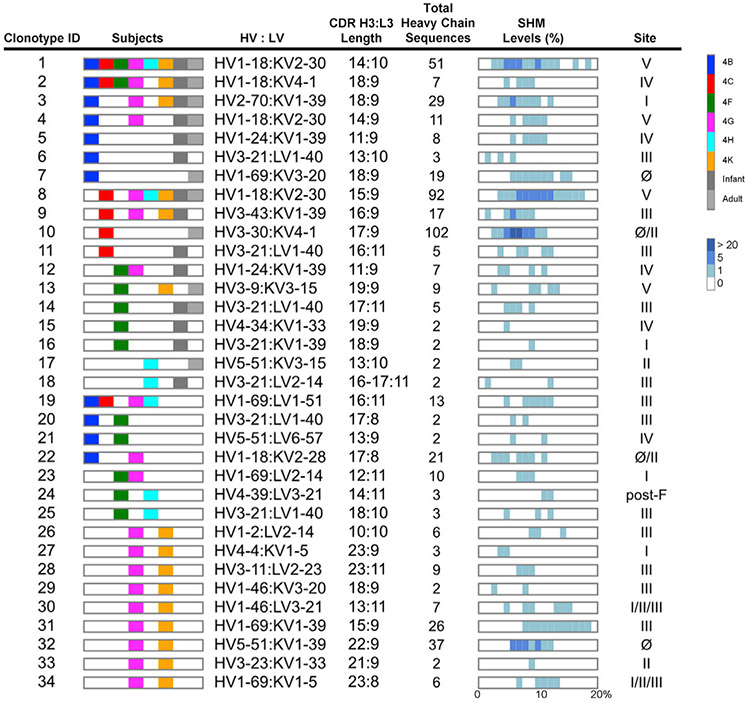

Public RSV F-specific antibody clonotypes identified among vaccine recipients

The RSV F-specific heavy and light chain sequence data from all six vaccinated subjects was evaluated for closely related sequences; i.e., the same HV, HJ, LV, and LJ genes; the same CDR H3 and L3 lengths; and 80% AA identity in the CDR H3 and the same light-chain germline gene usage and CDR L3 length. In total, 34 RSV F-specific public clonotypes were identified among the 6 vaccinees (Figure 3). When we included previously published sequence data from natural infection in adults and infants (Gilman et al., 2016; Goodwin et al., 2018), several of our public clones were similar to sequences found in these datasets. The most widely present clonotype targeted site V and was found in all six vaccinees and was identified previously in 3 of 3 healthy adults and 3 of 7 infants. The second most prevalent clonotype was found in 5 of 6 vaccinees as well as 1 adult and 1 infant and targeted site IV. We expressed and characterized at least one representative antibody from each public clonotype and determined that they collectively targeted all six major antigenic sites of the F glycoprotein. Twelve of 34 clonotypes targeted site III, followed in order by clonotypes to site IV, V, II, and Ø. Clonotype 24 targeted a post-F-specific site, and clonotype 10 targeted the site Ø and II regions of F. These data indicate that genetically similar RSV F-specific neutralizing antibodies are found in multiple subjects.

Figure 3. Identification of RSV F-specific public clonotypes.

Thirty-four public clonotypes were identified by augmenting probe-sorted memory B cell heavy-chain sequences with paired plasmablast and unpaired NGS data for all six subjects and by adding published RSV F-specific antibody heavy-chain sequences to the dataset. Public clonotypes are numbered 1–34. The second column shows subjects, each with a distinct color as shown in the key on the right, in which the clonotype was found. The third column shows the heavy- and light-chain germline gene pairing based on IMGT. The fourth column shows the CDR H3 and L3 amino acid length, respectively. The fifth column shows the total number of heavy-chain sequences identified for each clonotype. The sixth column shows the distribution of SHM within a clonotype, based on nucleotide divergence from the germline heavy chain gene. The rectangular box indicates SHM ranging from 0%–20% (bottom of the sixth column). The intensity of the blue hue corresponds to the number of heavy-chain sequences (as seen on the right in the bottom figure legend) at a specified SHM percentage. The last column indicates the antigenic site of RSV F recognized by the clonotype.

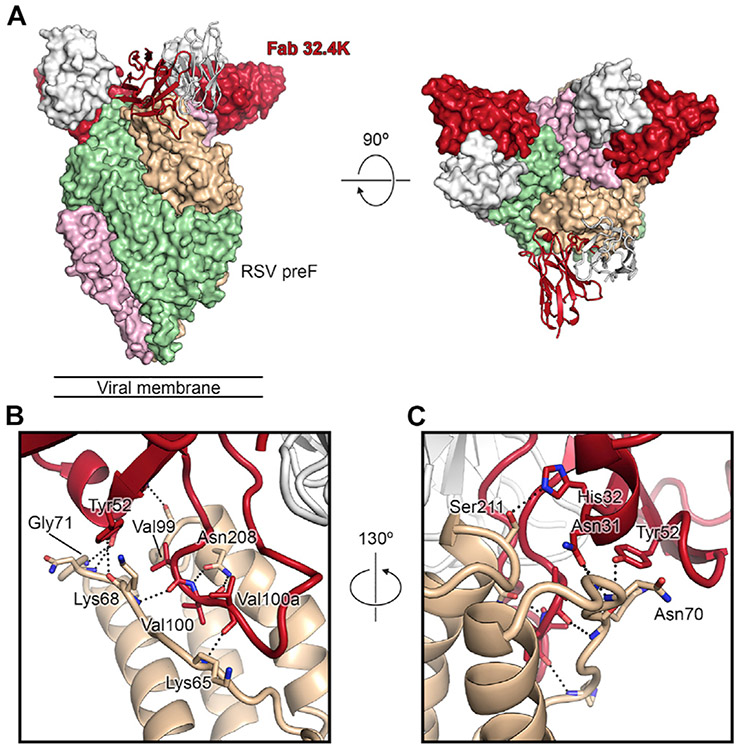

Structural basis of a potently neutralizing clonotype to site Ø

Because site Ø antibodies are generally highly potent, we sought to identify the molecular determinants of site Ø recognition by a public clonotype. Clonotype 32 (Figure 3) was found in two vaccinees (4G and 4K). We expressed a representative antibody (317.4K.L062.01) from clonotype 32 (referred to here as 32.4K) from subject 4K and determined an ~3.2-Å cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the Fab bound to DS-Cav1. Initial attempts to solve the structure were hindered by orientation bias, which was ultimately resolved by forming a ternary complex composed of pre-F, Fab 32.4K, and the site V Fab 317.4B.L017.01 described in Table 3, abbreviated here as 01.4B (Figure S4). This structure confirmed the results of the competition ELISA, with Fab 32.4K clearly bound to antigenic site Ø at the apex of pre-F (Figure 4A). Although the light chain of Fab 32.4K was angled away from DS-Cav1 and formed no significant interactions, the heavy chain of Fab 32.4K formed an extensive binding interface, burying 817 Å2 of surface area. The majority of this interface is formed by the CDR H3, which inserts itself between the α4 helix and the linker that connects the α1 helix to the β2 strand. Notably, the positioning of the CDR H3 is remarkably similar to that of the antibody D25, which was elicited by natural infection, although the overall binding angle differs between these two antibodies (Figure S4G). The Fab 32.4K CDR H3 contains a stretch of three consecutive valines (Val99, Val100, and Val100a), whose backbones form hydrogen bonds with the backbone of Lys65, the side chain of Asn208, and the backbone of Lys68, anchoring the CDR H3 in the gap between α4 and the α1-β2 linker (Figures 4B and 4C). Residues on CDR H1 and H2 also form hydrogen bonds to RSV F residues in this region. Because the CDR H3 forms extensive binding with pre-F (587 Å2), we computed the probability of generating the CDR H3 amino acid sequence motif present in clonotype 32 using the OLGA (optimized likelihood estimate of Ig amino acid sequences) algorithm (Sethna et al., 2019) with HV gene restriction and structure-based process to identify the CDR H3 sequence motif, as described previously (Kong et al., 2019). The mean frequency that would result in antibodies with the CDR H3 motif present in clonotype 32 was found to be 1.3E–7 ± 9.6E–8 (Figure S5C), a frequency lower than a number of other prevalent public antibodies to HIV-1 and influenza (Avnir et al., 2016; Joyce et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2013) and similar to recently described public HV2-70-derived influenza antibodies (7.8E–7 ± 1.2E–6) (Cheung et al., 2020; Figure S5). However, the binding affinity of germline-reverted 32.4K to DS-Cav1 was in the nanomolar range (1.1 nM) (Table S5), suggesting that the prevalent observation of this public class may occur because of the high affinity of the naive BCR to the site Ø epitope (Abbott et al., 2018).

Table 3.

Characterization of a representative antibody from each public clonotype

| Clonotype ID | mAb | RSV F Antigenic Site |

IC50 (ng/mL) |

IC80 (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 317.4B.L017.01 | V | 3 | 29 |

| 2 | 317.4K.L014.01 | IV | 98 | 363 |

| 3 | 317.4K.L100.01 | I | 64 | 742 |

| 4 | 317.4G.L031.01 | V | 17 | 45 |

| 5 | 317.4B.L061.01 | IV | 517 | 3,335 |

| 6 | 317.4B.L013.01 | III | 19 | 82 |

| 7 | 317.4B.L062.01 | Ø | 10 | 57 |

| 8 | 317.4C.L007.03 | V | 7 | 38 |

| 9 | 317.4C.L052.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 10 | 317.4C.L053.01 | Ø/II | n.n. | n.n. |

| 11 | 317.4C.L054.01 | III | 19 | 77 |

| 12 | 317.4G.L030.01 | IV | 39 | 152 |

| 13 | 317.4F.L023.01 | V | 10 | 18 |

| 14 | 317.4F.L084.01 | III | 20 | 91 |

| 15 | 317.4F.L082.01 | IV | 24 | 73 |

| 16 | 317.4F.L085.01 | I | p.n. | p.n. |

| 17 | 317.4H.L044.01 | II | p.n. | p.n. |

| 18 | 317.4H.L043.01 | III | 514 | 6,023 |

| 19 | 317.4B.L018.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 20 | 317.4F.L031.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 21 | 317.4F.L075.01 | IV | 95 | 451 |

| 22 | 317.4B.L011.01 | Ø/II | n.n. | n.n. |

| 23 | 317.4F.L013.01 | I | 1,126 | 38,895 |

| 24 | 317.4F.L064.01 | post-F | n.n. | n.n. |

| 25 | 317.4F.L027.01 | III | 44 | 118 |

| 26 | 317.4K.L057.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 27 | 317.4K.L058.01 | I | 192 | 680 |

| 28 | 317.4K.L034.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 29 | 317.4K.L059.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 30 | 317.4K.L015.01 | I/II/III | p.n. | p.n. |

| 31 | 317.4K.L060.01 | III | n.n. | n.n. |

| 32 | 317.4K.L062.01 | Ø | 14 | 59 |

| 33 | 317.4K.L061.01 | II | 67 | 1,002 |

| 34 | 317.4K.L017.01 | I/II/III | n.n. | n.n. |

p.n., partial neutralization; n.n., no neutralization.

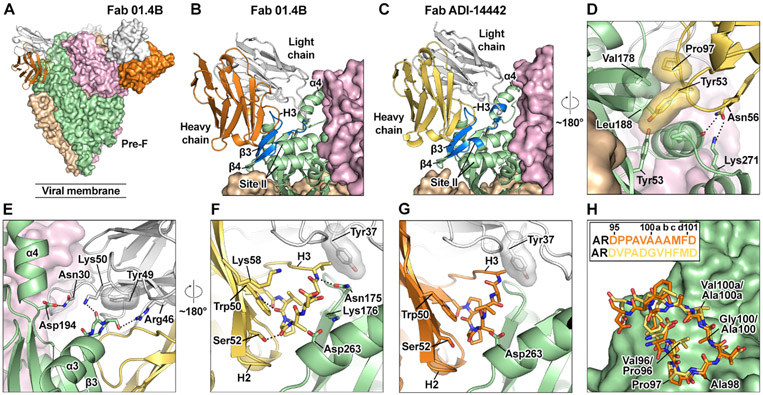

Figure 4. The 3.2-Å cryo-EM structure of pre-F bound by site Ø Fab 32.4K.

(A) The RSV F + Fab 32.4K (317.4K.L62.004) complex is shown as a molecular surface, with individual F protomers colored green, tan, or pink. Two 32.4K molecules are shown as molecular surfaces, and one is shown in ribbons, each with the heavy chain in orange and the light chain in white. The site V Fab 01.4B is not shown here for the sake of visual clarity (see Figure S4 for a full overview).

(B) Fab 32.4K heavy-chain contacts. RSV F and Fab 32.4K are shown as ribbon diagrams, and the green and pink RSV F protomers are not shown. Residues that form key interactions are shown as sticks, with oxygen atoms colored red and nitrogen atoms colored blue. Hydrogen bonds are shown as black dots.

(C) The view from (B), rotated by roughly 130° to show additional interactions.

Structural basis of site V recognition by the most prevalent public clonotype

The most prevalent public clonotype (clonotype 1) was the HV1-18:KV2-30 germline pairing, which was present in all six vaccine recipients and has also been identified in response to natural RSV infection, as noted above (Gilman et al., 2016; Mousa et al., 2017). To investigate the mode of recognition used by antibodies of this clonotype, we performed structural studies on two prototypic antibodies, each in complex with pre-F. The first, 01.4B, was isolated from vaccine recipient 4B. The second, ADI-14442, was isolated from a memory B cell of a healthy adult donor who had likely experienced multiple RSV infections throughout life (Gilman et al., 2016). Both antibodies are specific for pre-F, potently neutralize RSV, and recognize antigenic site V. Although clearly members of the same clonotype, the two antibodies differ in their level of SHM and CDR H3 sequences. We determined the cryo-EM structures of 01.4B and ADI-14442 in complex with prefusion F to 3.2-Å and 2.9-Å resolution, respectively (Table S4).

Both 01.4B and ADI-14442 interact with β3-β4 and the base of the α4 helix in site V as well as residues 262–265 associated with antigenic site II (Figures 5A-5C). The structure also revealed interactions between the germline-encoded CDR H2 and pre-F (Figure 5D). Tyr53 of CDR H2 fills a small cavity on the surface of pre-F that is formed by residues located on β3, β4, and the tip of antigenic site II. These residues are in close proximity in pre-F but separated by nearly 100 Å in post-F, explaining the strong preferential binding to pre-F observed in this class of antibodies. Pro97 of the CDR H3, which is highly conserved across the site-V-binding public antibodies described in this study, also appears to support this interaction by packing against Val178 on pre-F and Tyr53 of CDR H2. In the ADI-14442 structure, there is a hydrogen bond between CDR H2 residue Asn56 and Lys271 of pre-F. The side chain of CDR H2 residue Asn56 forms hydrogen bonds with residues on the tip of antigenic site II (Figure 5D). These CDR H2 residues are part of a YNGN motif that is unique to the IGHV1–18 germline and may favor use of this HV gene in recognition of site V.

Figure 5. Structural basis of site V recognition by clonotype 1 antibodies isolated after DS-Cav1 vaccination or natural RSV infection.

(A) Cryo-EM structure of 01.4B Fab in complex with pre-F. The three protomers of pre-F are shown as molecular surfaces colored tan, green, and pink. Two 01.4B molecules are shown as molecular surfaces, and one is shown in ribbons, each with the heavy chain in orange and the light chain in white. The constant domains of the Fabs were not modeled in the structure.

(B) Magnified view of the interface between 01.4B and pre-F, colored as in (A), except the third protomer of pre-F is shown in ribbons, with regions within 5.5 Å of 01.4B colored blue.

(C) The interface between ADI-14442 and pre-F, determined by cryo-EM, is shown with the same orientation and coloring as in (B), with the exception of the ADI-14442 heavy chain, which is colored gold.

(D) Further magnified view of the interface between the heavy chain of ADI-14442 and pre-F with an approximately 180° rotation about the trimeric axis relative to the orientation shown in (C).

(E) Magnified view of the interface between the light chain of ADI-14442 and pre-F.

(F) Magnified view of the ADI-14442 CDR H3 interactions with CDR H2, CDR L1, and pre-F with an approximately 180° rotation about the trimeric axis relative to the orientation shown in (E).

(G) Magnified view of the 01.4B CDR H3 interactions with CDR H2, CDR L1, and pre-F in the same orientation as in (F).

(H) Pre-F is shown as green molecular surfaces. The CDR H3s of 01.4B and ADI-14442 are shown as sticks colored orange and gold, respectively. The CDR H3 sequences are shown in the inset and are colored to match the structures.

Side chains of residues involved in hydrogen bonding or salt bridges are shown as sticks, with oxygen and nitrogen atoms colored red and blue, respectively. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are depicted as black dotted lines. Transparent molecular surfaces are shown for residues involved in hydrophobic interactions.

Germline-encoded residues in the light chain are also critical for forming interactions with pre-F (Figure 5E). In both structures, Tyr49 in the CDR L2 sits on top of the loop connecting α3 and β3. In the ADI-14442 structure, a hydrogen bond between framework residue Arg46 and Ser173 of pre-F is also present. The germline-encoded Lys50 of ADI-14442 CDR H2 forms a main-chain hydrogen bond with pre-F, an interaction that may be enhanced in 01.4B by a K50R substitution resulting from SHM (Figure S5). Finally, CDR L1 residue Asn30 forms a hydrogen bond with Asp194 at the base of α4. Similar to the interactions driven by the heavy chain, residues contacted by CDR L1 and L2 are in proximity in pre-F but separated by ~30 Å in post-F, concordant with the prefusion specificity of these antibodies. No contacts between CDR L3 and pre-F were visible for 01.4B or ADI-14442.

To further assess sequence signatures that might be characteristic of clonotype 1, we compared CDR H3 physiochemical position/properties of clonotype 1 sequences with private HV1-18:KV2-30 clones with the same CDR H3 length using a random forest algorithm. We identified distinguishing physiochemical properties at CDR H3 positions 6, 9, and 10. These indicated a bias toward the presence of a proline at position 6 and an alanine or other small residue at positions 9 and 10. The structures reveal that the presence of a larger residue at position 10 would be expected to clash with Tyr37 of the light chain (Figures 5F and 5G), explaining the preference for smaller residues at this position. The structures also demonstrated that the presence of a proline in position 6 likely serves two purposes. First, as highlighted above, Pro97 packs against pre-F Val178. Second, the torsion restraints of proline may favor the conformation of the CDR H3, which allows small hydrophobic residues at positions 9 and 10 to rest against the surface of pre-F. As a result, despite differences in sequence, the CDR H3 structures of 01.4B and ADI-14442 adopt a similar conformation and interact with prefusion F in a similar manner (Figure 5H). Although 01.4B and ADI-14442 are heavily mutated, very few of these substitutions occur in residues within the paratope, and most appear to have only subtle effects on the interaction with pre-F (Figure S5F and S5G). As performed for 32.4K, we calculated the mean theoretical frequency of antibodies with the CDR H3 motif present in the site V clonotype (Figure S5C). We found the frequency to be lower at 5.6E–7 ± 1.4E–7 than a number of other prevalent public antibodies to HIV-1 and influenza (Avnir et al., 2016; Joyce et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2013) but to be higher than recently described public HV2-70-derived antibodies (7.8E–7 ± 1.2E–6) (Cheung et al., 2020; Figure S5C). However, similar to what we observed for clonotype 32, the germline-reverted variant of 01.4B displayed high affinity (10.5 nM) for DS-Cav1 (Table S5).

DISCUSSION

Despite decades of research and a critical clinical need, an effective vaccine for RSV is not yet available. The DS-Cav1 subunit vaccine has shown promising immunogenicity in a phase I trial and is being developed further as a candidate vaccine. Compared with other clinically tested RSV F vaccine candidates that boost the F-binding antibody to a greater extent than neutralizing activity, the pre-F-stabilized immunogen boosting of neutralizing activity is proportional to boosting of F-binding antibodies, indicating a higher average antibody neutralizing potency (Crank et al., 2019; Ngwuta et al., 2015). To understand the molecular determinants of the response to this candidate RSV F vaccine, we performed a repertoire analysis of the B cell response to DS-Cav1 in six vaccine recipients. We observed that a single immunization boosted a diverse set of B cell lineages recognizing all known antigenic sites on pre-F. Among this diverse repertoire, we identified numerous public clonotypes, some present in the majority of vaccinees. Finally, we solved the structure of representative antibodies from the most dominant public clone as well as a potently neutralizing public clonotype to site Ø.

To understand the induced B cell repertoire at the single-cell level, we used antigen-specific probes to identify RSV F-specific memory B cells before and after vaccination. Sequences from these antigen-specific B cells formed our dataset of identified RSV F-specific antibody lineages and likely represent only a subset of the full RSV F repertoire in an individual. We expanded our analysis of these lineages with unpaired Illumina sequencing of bulk-sorted naive and memory B cells before and after vaccination and HV:LV emulsion repertoire analysis of bulk-sorted plasmablasts 7 days after vaccination. This full dataset facilitated an in-depth analysis of the RSV F-specific repertoire induced by DS-Cav1 immunization. Prior studies of natural RSV infection have documented a highly diverse repertoire of RSV F-specific antibodies (Gilman et al., 2016), and we confirm this result in the pre-vaccination samples from six subjects. Prior to this study, the effect of immunization with a pre-F-stabilized antigen on the RSV F B cell repertoire was unclear. Here we show that immunization with DS-Cav1 maintains the robust genetic diversity found in natural infection. We did not observe highly dominant clonotypes within each subject nor a dominant response to a specific antigenic site. Rather, the B cell response was diverse and targeted all known antigenic sites on RSV F.

Among the 555 RSV F-specific lineages identified, we found 125 that were present before and after immunization in a specific subject, and these were called boosted lineages. Most of these pre-existing lineages displayed substantial levels of SHM prior to vaccination with DS-Cav1, which likely explains the modest overall boost in SHM after immunization. We expressed IgG antibodies representing prevalent clonal lineages from five of six vaccine recipients; all antibodies bound to RSV F, and 32 antibodies displayed measurable neutralization. The most potent antibodies were to site Ø and V, and some of these displayed IC50 values as low as 2 ng/mL, which is approximately 2-fold more potent than mAb D25 (McLellan et al., 2013), the precursor to nirsevimab.

A site V-directed antibody (suptavumab, REGN2222) was evaluated in a phase III study in healthy preterm infants and failed to show clinical efficacy in reducing medically attended RSV infections. Although REGN2222 neutralized RSV subtype A viruses, it failed to neutralize subtype B viruses because of emergence of a subtype B strain carrying double substitutions in the site V antigenic region (L172Q/S173L) of the F glycoprotein. Substitutions in other antigenic sites, including site Ø, have also been observed in clinical isolates of RSV (Mas et al., 2018). Our results demonstrate that such substitutions can disrupt binding of a subset of antibodies directed against each site. However, the mutations in site V or site Ø do not affect binding of antibodies directed toward other sites. This highlights the approach of using a native prefusion RSV F that elicits a polyclonal neutralizing antibody responses to multiple antigenic sites.

Our in-depth repertoire analysis also enabled identification of 34 RSV F-specific public clonotypes; i.e., highly similar heavy- and light-chain sequences found in more than one subject. Six of the 34 clonotypes were found in at least 3 vaccine subjects, and, remarkably, the two most prevalent clonotypes were found in 5 and 6 of the vaccinees. Additionally, 18 of the clonotypes identified in our six vaccinees could be identified in previously published sequences from natural infection. This further highlights the common nature of public clonotypes to RSV F.

We solved a cryo-EM structure of potent antibody 32.4K from public clonotype 32 bound to antigenic site Ø of pre-F. This is the first determination of the structure of a public clonotype to antigenic site Ø. We found that Fab 32.4K mainly uses its CDR H3 to bind to pre-F in a manner similar to antibody D25. Although D25 and 32.4K adopt different angles of approach, their CDR H3s occupy the same cleft between the α4 helix and the link that connects the α1 helix to the β2 strand. Both of these CDR H3s make use of a short stretch of consecutive hydrophobic residues to wedge into this cleft, which is only present in the prefusion conformation, stabilizing pre-F and preventing the conformational rearrangements that are required to reach the post-fusion conformation. Furthermore, we determined the structure of two members of clonotype 1 targeting antigenic site V—one antibody was isolated from a naturally infected adult and one from a DS-Cav1 vaccine recipient. The structures revealed a similar mode of recognition for binding to pre-F that is dependent on germline-encoded residues in the heavy and light chains as well as the presence of a number of small residues in the CDR H3. Several clonotypes targeted site V: the genetically similar clonotypes 1, 4, and 8 (HV1-18:KV2-30) and clonotype 13 (HV3-9:KV3-15). Sequences that fall into one of these 4 clonotypes have been identified previously in naturally infected donors (Gilman et al., 2016; Mousa et al., 2017), further highlighting the commonality of these site V-directed clonotypes.

Previous studies of germline antibodies, including those targeting the CD4 binding site of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein and the stem region of influenza hemagglutinin, suggest that public clonotypes often exhibit at least one of two properties: increased recombination frequency or high germline affinity for antigen (Abbott et al., 2018). Our analysis of the generation probability of a specific CDR H3 sequence motif suggests that a high probability does not explain the prevalence of RSV F public clonotypes. However, the germline-reverted versions of clonotype 1 (01.4B) and clonotype 32 (32.4K) maintained nanomolar affinity for pre-F. Thus, our results suggest that HV1-18:KV2-30 and HV5-51:KV1-39 precursors may have a competitive advantage in germinal centers that facilitates their stimulation in response to natural infection and vaccination.

Our results demonstrate that vaccination with a pre-F-stabilized immunogen (DS-Cav1) boosts a diverse polyclonal repertoire of B cells that recognize all known antigenic sites on pre-F and did not boost post-F exclusive antibody lineages. These data help to explain the robust boost in serum neutralizing activity produced by DS-Cav1 vaccination and suggest that the diverse polyclonal repertoire induced by DS-Cav1 will cover RSV subtypes A and B and would be difficult to escape. We also identify vaccine stimulation of numerous public clonotypes with potent neutralizing activity. Structural analysis of representative antibodies from two clonotypes provides insights into the mechanism of neutralization and their common elicitation. The genetically diverse polyclonal neutralizing antibody response elicited by this pre-F-stabilized vaccine, together with identification of common responses among individuals, further supports development and advanced testing of pre-F-based vaccines against RSV.

Limitations of study

Two limitations of this study are the depth of the sequenced BCR human repertoire and the small subset of individuals studied. Previous work (Soto et al., 2019) found that the circulating B cell repertoire of each individual contains 9–17 million B cell clonotypes. When applying the same parameters to our data for clonotype assignment, we identified 120,000–230,000 B cell clonotypes per subject, resulting in an estimated ~1% sequencing of the human BCR repertoire. Although it is likely that a deeper depth of sequencing would allow identification of more RSV F-specific boosted lineages, we were limited practically in the number of B cells that could be isolated from these samples.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by lead contact

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

RSV F-specific probe-sorted sequences, and sequences of antibodies expressed in Tables 1, 2, and 3 have been deposited in NCBI GenBank: MW654567-MW655494. Unpaired Illumina NGS sequencing can be downloaded from NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the bioproject ID Bioproject ID: PRJNA701161. Atomic coordinates for the PR-DM–Fab 4K–4B-L107–01 and the PR-DM–ADI-14442 structures have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank and assigned PDBs 7LUC and 7LUE, respectively. Cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the EMDB and assigned codes EMD-23520 and EMD-23521.

METHOD DETAILS

Isolation of RSV F-specific B cell sequences

Before and after vaccination, cryopreserved PBMC were stained with a mixture of fluorescently labeled pre-F and post-F sorting probes and sorted on a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Aria II, RSV F-specific B cells were single cell sorted and indexed into 96-well plates containing lysis buffer. Sequencing of the immunoglobulin genes was performed by single-cell multiplex PCR as previously described (Doria-Rose et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2010).

Expression and purification of recombinant antibodies

100 mL cultures of Freestyle 293-F cells in Expi293 Expression Medium (2.56e6 cells/mL) were prepared for each Ab transfection using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher). Monoclonal antibodies were then purified using recombinant Protein-A Sepharose (GE Healthcare) in chromatography columns (BioRad) per manufacturer guidelines. Elution step was performed with 15 mL of IgG elution buffer (Thermo Fisher) and 800 μL neutralizing buffer (1M Tris-HCl). Finally, buffer exchange into PBS was performed using 30 kDa centrifugal tubes (Millipore Sigma).

Production of RSV F Fabs

Fabs were generated by cleavage of purified monoclonal antibodies with LysC enzyme (New England BioLabs) at 37°C overnight. For each reaction, 1 mg monoclonal IgG was mixed with 2 ug LysC enzyme. Cleavage was verified via SDS-PAGE analysis and Fab fragments were then separated from Fc fragments by passage of cleavage mixture through a Protein A column. The Fab was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 increase column (GE Healthcare).

Neutralization Assays

Neutralization assays were performed as previously described (Crank et al., 2019). NCI-H28 cells were seeded at a density of 2.4 × 104 cells/well in 384-well black optical bottom plates from ThermoFisher (Cat#142761). Serial 4-fold dilutions of monoclonal antibodies (starting at 1:10 with a total of 11 dilutions) were performed, in a final volume of 45 μL. An equal volume of recombinant mKate-RSV subtype A (strain A2) was added to the diluted samples and incubated at 37°C for 1 h (Hotard et al., 2012). After incubation, 50 μL of each diluted sample-virus mixture was added to the NCI-H28 cells and incubated for 37°C for 24 h. Fluorescence endpoints were recorded at 24 h using excitation at 588 nm and emission at 635 nm (SpectraMax M2e, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). The IC50 and IC80 titers for each sample were determined using a four-parameter non-linear regression curve fit with GraphPad Prism version 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). IC50 and IC80 values, calculated as mean of at least two independent experiments.

Generation of natively paired HV:LV from plasmablast cells:

For anti-RSV antibody response isolation, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from six healthy human volunteer seven days after immunization. PBMCs were stained with antigens (Table S1) and plasmablasts sorted CD3−CD8−CD14−CD56−CD19+CD27highCD38high (Figure S1C) using a FACS Aria II sorter (BD Biosciences). Sorted cells were sequenced as previously described (McDaniel et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Briefly, a flow-focusing nozzle was used to encapsulate a single B cell in an emulsion droplet containing lysis buffer and oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads (New England Biolabs) to capture single-cell mRNA. A Superscript III RT-PCR kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to perform a variable heavy (HV):Variable Light (LV) chain overlap extension RT-PCR. Nested PCR of the resulting amplicon was performed using KAPA HiFi DNA Polymerase (Roche). Sequencing of the paired HV:LV amplicons was performed using Illumina MiSeq 2x250 next generation sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis of HV:LV sequences was performed as described previously (DeKosky et al., 2015).

Preprocessing of NGS Data: USEARCH used to merge paired end reads and to perform quality filtration. V(D)J germline genes of filtered sequences were assigned using BLAST+ in SONAR (Schramm et al., 2016), reads with missing assignments, out-of-frame junctions, and/or stop codons were removed from the analysis. The retained V(D)J sequences were clustered at 99% nucleotide sequence identity to avoid possible PCR and sequencing error. Vaccinee’s preprocessed NGS reads and single cell sequences were combined with published RSV F-specific antibody sequences for public clonotype analysis.

Clonotype Analysis: For assessing the clonotypes, two informatic methods were applied to evaluate the clonotype. At the end, the outputs of informatic approaches were evaluated and merged for characterization. For the first method (SONAR) (Schramm et al., 2016) of performing basic quality control and annotating NGS and probe sorted sequences, we used previously published SONAR platform (Schramm et al., 2016). For the second method, the master sequences were analyzed by Clonify using default cut-off and split by “gene” to group sequences into clones (Briney et al., 2016). A customized python script to group CDR3 amino acids (the amino acids between conserved second “Cys” and “Trp”) shares 80% or higher sequence identity between published and donor’s sequences. The private clonotype (antibody clone in single donor) was defined by the antibody encoded with the same V and J germline gene and the CDR3 amino residues that share at least 80% sequence identity. For public clonotype, clonotype sharing between donors, additional D gene assignment on CDR H3 was included for high confidence of clonotype. D gene assignments is challenging because the segments of D gene alignment are relatively shorter than HV and HJ germline genes and high-level mutations on CDR H3. We accept different D gene assignments while it shares an identical segment of amino acid translation. For example, a triple Ala segment observed in CDR H3 can be encoded by HD6-13 and HD6-25. Both D germline genes will be accepted as one public clonotype.

Competition ELISA

Detailed methods for competition ELISAs have been previously published (Kong et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2016). Briefly, mAbs were biotinylated using an EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-biotinylation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, CA) and titrated on DS-Cav1-coated plates. Avidin D-HRP conjugate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and TMB (KPL, Gaithersburg MD) were used for color development. The optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was determined with SpectraMax Plus (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The concentration of biotinylated mAb in the linear range of the titration curve was chosen for competition ELISA. Unlabeled competitor mAbs were serially diluted and added to the DS-Cav1-coated plate. Following incubation for 30 min at room temperature, biotinylated mAbs were added, and OD readings were recorded using biotinylated mAb alone as a binding control. Percent inhibition of binding was calculated as follows:

KD determination

Dissociation constants were assessed with the FortéBio Octet HTX instrument (Molecular Devices). Streptavidin (SA) biosensors were hydrated in 1%BSA in PBS for at least ten minutes before use. Briefly, biotinylated pre-F and post-F proteins were immobilized on SA biosensors and dipped into buffer (1% BSA in PBS). The biosensors bound to antigen were then dipped into a 3-fold dilution series of Fab of interest for 5 minutes, and subsequently dipped into the 1% BSA in PBS buffer for 10 minutes in order to allow the Fab to dissociate from pre-F or post-F. All assay steps were performed at 30°C with agitation set to 1000 rpm. Data analysis was performed using the Octet analysis software (version 9.0) and fit to a 1:1 fit model.

Octet biolayer interferometry epitope binning using escape mutations (patch mutants) for antigenic site determination:

Patches for each antigenic site contain substitutions associated with viral escape or decreased antibody binding. Refer to Table S10 that includes mutations for each antigenic site, as well as the goal of each mutations and a reference to where the mutations were first described. In addition to competition ELISA, antibody antigenic site assignments were determined using biolayer interferometry (Octet) with a panel of His-tagged RSV F protein patch mutants on a ForteBio Octet HTX instrument. Recombinant RSV F proteins and analyte monoclonal antibodies were diluted to a working concentration of 5 μg/mL and 10 μg/mL, respectively, in buffer solution (1% BSA in PBS). 45 μL of protein, antibody, and buffer at working concentrations were added to 384-well tilted-bottom plates (ForteBio, Cat. no. 18-5080). Recombinant RSV F proteins were loaded on anti-Penta-His (HIS1K) biosensors (ForteBio, Cat. no. 18-5122) for 900 s, followed by 60 s of baseline in 1% BSA in PBS buffer. Monoclonal antibody association to F protein-loaded HIS1K biosensors was assessed for 600 s. To assess dissociation of antibody binding to F protein-loaded biosensors, tips were submerged 1% BSA in PBS buffer for 300 s. Response (nm shift) was quantified using the Data Analysis software (ForteBio). Complete abrogation of antibody binding or a > 75% reduction in response to individual or combinations of patch mutants were used to determine epitope bins. Percent reduction of binding to DS-Cav1 patch mutants was calculated with unmodified DS-Cav1 set as 100% binding.

Figure and plot generation

Heatmaps were generated using the Matplotlib plotting module (version 0.8.1) in Python (version 2.7.14). Web logos were plotted using WebLogo (version 3.7.1, PMID: 15173120).

Production of Fab ADI-14442

Plasmids encoding the heavy and light chain of ADI-14442 were co-transfected at a 1:1 ratio into FreeStyle 293-F cells. The clarified supernatant was concentrated using a tangential flow filtration cassette (PALL) before the Fab was purified using the CaptureSelect IgG-CH1 affinity matrix (Life Technologies). The Fab was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 increase column (GE Healthcare) or buffer exchange using a HiPrep 26/10 Desalting column (GE Healthcare) into 2mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 0.02% NaN3.

Crystallization and X-ray data collection

Fab ADI-14442 was crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 100 nL of Fab at 13 mg/mL with 50 nL of reservoir solution composed of 1.8 M ammonium sulfate, 0.09 M HEPES pH 7.5 and 0.05% ethyl acetate. Crystals were cryoprotected by addition of 1 μL of 3.4 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5 before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected to 2.9 Å resolution at the SBC beamline 19-ID (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory).

Data processing was carried out using software curated by SBGrid (Morin et al., 2013) and accessed through CCP4i (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994; Potterton et al., 2003). Data were integrated in iMOSFLM (Powell et al., 2017) and scaled and merged using AIMLESS (Evans and Murshudov, 2013). The unpublished crystal structure of the closely related Fab ADI-14402 was used to obtain a molecular replacement solution using PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007). Iterative refinement and manual model building were then carried out with PHENIX (Adams et al., 2002; Afonine et al., 2018) and COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004), respectively, to an Rwork/Rfree of 19.0%/23.1%.

Production of protein complexes for cryo-EM

The mammalian expression vector encoding the PR-DM (Krarup et al., 2015) variant of pre-F with a C-terminal HRV 3C cleavage site, 8x His-tag and StrepTagII was transfected into FreeStyle 293-F cells. Approximately 4 hours after transfection, 5 μM kifunensine was added to the cells. The secreted proteins were exchanged into PBS using tangential flow filtration and then purified using Strep-Tactin resin (IBA) and treated with 10% (wt/wt) EndoH to remove N-linked glycans. The proteins were then purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer containing 2 mM Tris pH 8, 200 mM NaCl and 0.02% NaN3.

To produce the ADI-14442 Fab–pre-F complex, purified pre-F was combined with a 1.5-fold molar excess of ADI-14442 Fab and incubated at room temperature for approximately 30 minutes. The complex was separated from excess Fabs by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare) in buffer containing 2 mM Tris pH 8, 200 mM NaCl and 0.02% NaN3.

To form the PR-DM–Fab 4K–Fab 4B complex, purified pre-F was combined with a 1.2-fold molar excess of both Fab 4K and Fab 4B. This mixture was incubated on ice for 10 minutes.

Cryo-EM data collection

A cryo-EM dataset of the PR-DM–ADI-14442 complex was collected on a Titan Krios operating at 300kV and equipped with a K2 Summit detector. C-flat holey carbon 1.2/1.3 grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) were plasma cleaned for 30 s using a Gatan Solarus 950 with a 4:1 O2:H2 ratio. 3 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution of the complex was deposited onto grids and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Scientific) set to 100% humidity and 4°C, with a blot time of 5 s and a blot force of −1. Data were collected at 22,500x magnification, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 1.075 Å. A total of 30 frames were collected for each micrograph, with defocus values ranging from −1.5 μm to −2.5 μm, a total exposure time of 9 s, and a total electron dose of ~48 e−/Å2.

The cryo-EM dataset of the PR-DM–Fab 4K–Fab 4B complex was collected on a Titan Krios operating at 300kV and equipped with a K3 detector using C-flat holey carbon 1.2/1.3 grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) plasma cleaned for 30 s with a Gatan Solarus 950 at a 4:1 O2:H2 ratio. 3 μL of a 0.7 mg/mL solution of the complex was deposited onto grids and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Scientific) set to 100% humidity and 4°C, with a blot time of 5 s and a blot force of 1. Data were collected at 22,500x magnification, corresponding to a calibrated pixel size of 1.047 Å. A total of 30 frames were collected for each micrograph, with defocus values ranging from −1.3 μm to −2.5 μm, a total exposure time of 4.5 s, and a total electron dose of ~36 e−/Å2.

Cryo-EM data processing

The PR-DM–ADI-14442 dataset was processed in Relion 3 (Zivanov et al., 2018). Laplacian-of-Gaussian-based automatic particle picking was used to pick a total of 730,836 particles from 2,134 micrographs. After two rounds of 2D classification, 2D class averages generated from a total of 118,944 particles were used for template-based picking in Relion 3 using 20 Å lowpass filtering. A total of 412,240 particles were picked. After 2D classification, 371,323 particles were used to generate an initial model which was then used for 3D refinement, resulting in a 3.5 Å map. Postprocessing, CTF refinement, and Bayesian polishing resulted in a final resolution of 2.9 Å. The previously determined structure of PR-DM and the ADI-14442 Fab structure determined here by X-ray crystallography were used as initial models. Manual model building was carried out using Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and refinement of the coordinates was performed using Phenix (Adams et al., 2002; Afonine et al., 2018). Additional model optimization was performed using ISOLDE (Croll, 2018), accessed through ChimeraX (Goddard et al., 2018).

For the PR-DM–4B–137 dataset was processed in cryoSPARC v2.15.0 (Punjani et al., 2017). Template-based particle picking was used to pick a total of 1,385,717 particles from 1,647 micrographs. After ab initio volume calculation, iterative 2D and 3D classification, this particle stack was curated down to 526,804 particles which were then used to calculate a 3.2 Å map, imposing C3 symmetry and using non-uniform refinement. Due to the relatively poor density at the interface between Fab 137 and PR-DM in this 3.2 Å map, two copies of Fab 137 were masked out and the subtracted particles were subjected to symmetry expansion. The resulting particle stack was used to calculate a new C1 3.3 Å map that exhibited enhanced features at the single remaining Fab 137 interface, despite the lower overall resolution. Model building was performed manually in Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and iterative rounds of model refinement were performed in Phenix (Adams et al., 2002; Afonine et al., 2018) and ISOLDE (Croll, 2018).

Fab affinity measurements for ADI-14576, ADI-14442 and variants

The affinity of ADI-14576, ADI-14442 and variants of each for pre-F were measured using SPR. Purified pre-F (DS-Cav1; McLellan et al., 2013) with a C-terminal 8x His-tag and Avi-tag was captured on the sample flow cell of an NTA sensor chip to ~80–230 RU per cycle using a Biacore X100 (GE Healthcare). The NTA chip was regenerated between each cycle with 0.35 M EDTA followed by 0.5 mM NiCl2. A buffer-only reference sample (HBS-P+ pH 8) was injected over both flow cells, followed by 2-fold serial dilutions of each antibody ranging from 25 nM to 1.6 μM to for ADI-14576 and the S31N variant of ADI-14576, from 37.5 nM to 600 nM for the 14576 HC: 14442 LC, and from 1.56 nM to 100 nM for the 14442 HC:14576 LC variant, the CDR H3 swap variant, and the CDR H3 swap variant with the S31N substitution. For each titration, one concentration near the center of the series was replicated. The data were double-reference subtracted and fit to a 1:1 binding model using Scrubber. For the ADI-14576 Fab, the ADI-14576 HC:ADI-14442 LC, and ADI-14576 + S31N, the off-rate of the interaction was too rapid to be accurately determined. For these antibody fragments the data were double reference subtracted and fit using a steady-state affinity model.

Construction of germline-reverted antibodies

01.4B and 32.4K antibodies were reverted to their predicted heavy chain (HV, HJ) and light chain (LV, and LJ) germline amino acid sequences and expressed as immunoglobulins.

Probability of calculating CDR H3 amino acid sequence

OLGA software was used to compute probability of having specific V-D-J recombination (Sethna et al., 2019) and used 13 heavy chain recombination models described in Cheung et al. (2020) for computing recombination frequency. We applied structural-based process to identify CDR H3 sequence motif described in Kong et al. (2019). Briefly, PDBePISA server used to calculate the buried surface area (BSA) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/), the CDR H3 motif was defined by the contact residues on CDR H3. The clonal members were further used to expand the compatible amino acids of motif. The probability of generating a given CDR H3 in clonotype 1 was computed by using IGHV1-18 germline gene, 97P[AV]X[AG][AV] motif on 14 amino acids long CDR H3. For clonotype 32, the computation was done by using germline IGHV5 51, 96VX{2}V[VL][VL][ATP][AESTYVP]X{4}YXY motif on 22 amino acids long CDR H3.

Bioinformatic analyses of physiochemical properties

CDR H3 amino acid sequences were first “featurized” using 30 amino acid physicochemical properties (Sharma et al., 2013). Distinguishing characteristics of public CDR H3 sequences were then determined by comparing the physicochemical properties at each position to those of private CDR H3 sequences of the same length using the R package, randomForest (Liaw, 2018). In total, 1000 trees were constructed for each random forest with an out-of-bag error rate less than 1% for each comparison.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| FITC anti-human IgD (IA6-2) | Biolegend | Cat# 348205; RRID:AB_10613638 |

| Percp-Cy5.5 anti-human IgM (G20-127) | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561285; RRID:AB_10611998 |

| BV421 anti-human IgG (G18-145) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 562581; RRID:AB_2737665 |

| BV510 anti-human CD3 (UCHT1) | Biolegend | Cat# 300447; RRID:AB_2563467 |

| BV510 anti-human CD8 (RPA-T8) | Biolegend | Cat# 301047; RRID:AB_2561378 |

| BV510 anti-human CD56 (5.1H11) | Biolegend | Cat# 362533; RRID:AB_2565632 |

| BV510 anti-human CD14 (M5E2) | Biolegend | Cat# 301841; RRID:AB_2561379 |

| BV510 Aqua dead cell stain kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# L34957 |

| BV605 anti-human CD27 (O323) | Biolegend | Cat# 302829; RRID:AB_11204431 |

| AF700 anti-human CD38 (HIT2) | Biolegend | Cat# 303523; RRID:AB_2228785 |

| ADI-14442 | Gilman et al., 2016 | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, recombinant proteins, and biosensors | ||

| rProtein A Sepharose Fast Flow | GE Healthcare | Ca# 17-1279-03 |

| Econo-Pac Chromatography Columns | BioRad | Cat# 7321010 |

| Amicon ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Unit | Millipore Sigma | Cat# UFC903024 |

| IgG elution buffer | Thermo Scientific | Cat# 21009 |

| IgG binding buffer | Thermo Scientific | Cat# PI21007 |

| Endoproteinase LysC | New England BioLabs | Cat# P8109S |

| Expi293 Expression Medium | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A1435103 |

| Recombinant Protein A Sepharose | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17-1279-03 |

| Streptavidin (SA) Biosensor Tips | ForteBio | Cat# 18-5021 |

| Ultrapure BSA | ThermoFisher | Cat#: AM2616 |

| Avidin D, Peroxidase labeled (Av-HRP) | Vector Laboratories | Cat# A-2004 |

| SureBlue TMB Microwell Peroxidase Substrate | Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories | Cat# 52-00-00 |

| Superdex200 10/300GL Column | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat# 28990944 |

| Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottom 96-Well Plates | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 44-2404-21 |

| Superase-IN | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# AM2696 |

| SSIII/Plat Taq mix | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# 12574026 |

| LiDS | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L9781-25G |

| DTT | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# 43819-5G |

| Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) 1M | Quality Biological | Cat# 351-006-101 |

| LiCl | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# L4408-100G |

| EDTA 0.5M Solution | VWR | Cat# 10128-442 |

| Span 80 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# S6760-250ML |

| Tween 80 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# P1754-25ML |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# X100-5ML |

| Mineral Oil | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# M5904-6X500ML |

| Magnetic Poly(dT) beads | NEB | Cat# S1419S |

| Diethyl Ether | Andwin Scientific | Cat# E138-500 |

| MgCl2 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# 208337-100G |

| KCl | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# P9541-500G |

| Qubit kit | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# Q32854 |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28706 |

| MiSeq Kits | Illumina | Cat# MS-102-2003 |

| RSV prefusion F (PR-DM) HRV 3C site-8x His-tag-StrepTagII | Krarup et al., 2015 | N/A |

| RSV prefusion F (DS-Cav1) thrombin site-6x His-tag-StrepTag | McLellan et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human: FreeStyle 293-F cells | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# R79007 |

| Human: Mesothelioma cells (H28) | ATCC | Cat# CRL-5820 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 7.01 Software | GraphPad Prism Software | N/A |

| PyMol Molecular Graphics System, v1.8.6 | Schrödinger | https://pymol.org |

| IMGT/V-Quest | IMGT | http://www.imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/vquest |

| FlowJo v9.9.3 | FlowJo | https://www.flowjo.com |

| SONAR | Schramm et al., 2016 | https://www.github.com/scharch/SONAR |

| Clonify | Briney et al., 2016 | https://github.com/briney/clonify-python |

| Python (v2.7.14) | Python | www.python.org |

| OLGA | Sethna et al., 2019 | https://www.github.com/statbiophys/OLGA |

| ForteBio Data Analysis 9.0 software | ForteBio, Inc | https://www.moleculardevices.com/ |

| R | 3.6.1 | https://www.r-project.org |

| M50 Pump Software | PL-2303 CheckChipVersion Tool Program v1.0.0.6 | https://www.vici.com |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.am.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| cryoSPARC v2 | Punjani et al., 2017 | https://cryosparc.com |

| Leginon | Suloway et al., 2005 | http://emg.nysbc.org/redmine/projects/wiki/Leginon_Homepage |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Goddard et al., 2018 | https://www.rbvi.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 2002; Afonine et al., 2018 | https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| ISOLDE | Croll, 2018 | https://isolde.cimr.cam.ac.uk/what-isolde/ |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of vaccinees | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| plasmid: DS-Cav1-HA-AviHis (RSV A2) | This paper | N/A |

| plasmid: post-F-HA-AviHis (RSV A2) | This paper | N/A |

| plasmid: RSV B18537DS-Cav1-HA-AviHis | Joyce et al., 2019 | N/A |

| RSV B18537 DS-Cav1-HA-AviHis (L172Q/S173L) | This paper | N/A |

| RSV B18537 DS-Cav1-HA-AviHis (I206M/Q209R) | This paper | N/A |

| Deposited data | ||

| RSV F Antibody sequences | This paper | Genbank: MW654567-MW655494 |

| Illumina MiSeq sequences of antibody transcripts | This paper | Bioproject ID: PRJNA701161 |

| RSV F + 32.4K + 01.4B cryo EM map | This paper | EMD: 23520 |

| RSV F + 32.4K + 01.4B atomic model | This paper | PDB: 7LUC |

| RSV F + ADI-14442 cryo EM map | This paper | EMD: 23521 |

| RSV F + ADI-14442 atomic model | This paper | PDB: 7LUE |

| Fab ADI-14442 atomic model | This paper | PDB: 7LUD |

| Virus strains | ||

| mKate RSV subtype A2 | NIH/VRC | N/A |

| Critical commercial sssays | ||

| ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A14525 |

| DNA gene synthesis and cloning | GenScript Biotech Corporation | N/A |

| Octet HTX System for Bio-Layer Interferometry | ForteBio | Part# 30-5102 |

| AviTag Kit | Avidity | Cat# BirA-500 |

| Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase | ThermoFisher | Cat# 18080093 |

| EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotinylation Kit | Life Technologies | Cat# 21425 |

| KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix | KapaBiosystem | Cat # KK2601 |

Highlights.

DS-Cav1 vaccination boosts diverse B cell lineages recognizing the pre-F form of RSV F

Vaccine-induced antibody lineages target all known antigenic sites on RSV F

RSV F-specific B cell sequencing identifies numerous pre-F-specific public clonotypes

Structural analysis of a site V public clonotype reveals common mode of recognition

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Nguyen and David Ambrozak for assistance with flow cytometry. We also thank the members of the Humoral Immunology Section, Viral Pathogenesis Laboratories, and the ImmunoTechnology Section, Vaccine Research Center, especially Azad Kumar for producing and providing pre-and post-F proteins and Deepika Nair for helping produce RSV F antigenic site mutants. We also thank Yuliya I. Petrova and Rosemarie Mason for helpful comments and guidance and Man Chen for running some of the serum neutralization assays. In addition, we thank Yaroslav Tsybovsky for informative nsEM structures. Support for this work was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the Vaccine Research Center, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. We also thank the volunteers who participated in the VRC 317 clinical trial.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.03.004.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

B.S.G., J.S.M., and P.D.K. are inventors on a patent entitled “Prefusion RSV F proteins and their use” (US Patent No. 9738689).

REFERENCES

- Abbott RK, Lee JH, Menis S, Skog P, Rossi M, Ota T, Kulp DW, Bhullar D, Kalyuzhniy O, Havenar-Daughton C, et al. (2018). Precursor Frequency and Affinity Determine B Cell Competitive Fitness in Germinal Centers, Tested with Germline-Targeting HIV Vaccine Immunogens. Immunity 48, 133–146.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, and Terwilliger TC (2002). PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 58, 1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonine PV, Poon BK, Read RJ, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, and Adams PD (2018). Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avnir Y, Watson CT, Glanville J, Peterson EC, Tallarico AS, Bennett AS, Qin K, Fu Y, Huang CY, Beigel JH, et al. (2016). IGHV1-69 polymorphism modulates anti-influenza antibody repertoires, correlates with IGHV utilization shifts and varies by ethnicity. Sci. Rep 6, 20842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Lu, Liu H, Tabor DE, Tovchigrechko A, Qi Y, Ruzin A, Esser MT, and Jin H (2019). Emergence of new antigenic epitopes in the glycoproteins of human respiratory syncytial virus collected from a US surveillance study, 2015–17. Sci. Rep 9, 3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briney B, Le K, Zhu J, and Burton DR (2016). Clonify: unseeded antibody lineage assignment from next-generation sequencing data. Sci. Rep 6, 23901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CSF, Fruehwirth A, Paparoditis PCG, Shen CH, Foglierini M, Joyce MG, Leung K, Piccoli L, Rawi R, Silacci-Fregni C, et al. (2020). Identification and Structure of a Multidonor Class of Head-Directed Influenza-Neutralizing Antibodies Reveal the Mechanism for Its Recurrent Elicitation. Cell Rep. 32, 108088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 50, 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D, Bianchi S, Vanzetta F, Minola A, Perez L, Agatic G, Guarino B, Silacci C, Marcandalli J, Marsland BJ, et al. (2013). Cross-neutralization of four paramyxoviruses by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature 501, 439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crank MC, Ruckwardt TJ, Chen M, Morabito KM, Phung E, Costner PJ, Holman LA, Hickman SP, Berkowitz NM, Gordon IJ, et al. ; VRC 317 Study Team (2019). A proof of concept for structure-based vaccine design targeting RSV in humans. Science 365, 505–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll TI (2018). ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol 74, 519–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky BJ, Ippolito GC, Deschner RP, Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Rawlings BM, Varadarajan N, Giesecke C, Dörner T, Andrews SF, et al. (2013). High-throughput sequencing of the paired human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain repertoire. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 166–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky BJ, Kojima T, Rodin A, Charab W, Ippolito GC, Ellington AD, and Georgiou G (2015). In-depth determination and analysis of the human paired heavy- and light-chain antibody repertoire. Nat. Med 21, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, et al. ; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2014). Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature 509, 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PR, and Murshudov GN (2013). How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman MS, Castellanos CA, Chen M, Ngwuta JO, Goodwin E, Moin SM, Mas V, Melero JA, Wright PF, Graham BS, et al. (2016). Rapid profiling of RSV antibody repertoires from the memory B cells of naturally infected adult donors. Sci. Immunol 1, eaaj1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman MS, Moin SM, Mas V, Chen M, Patel NK, Kramer K, Zhu Q, Kabeche SC, Kumar A, Palomo C, et al. (2015). Characterization of a Prefusion-Specific Antibody That Recognizes a Quaternary, Cleavage-Dependent Epitope on the RSV Fusion Glycoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Huang CC, Meng EC, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Morris JH, and Ferrin TE (2018). UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin E, Gilman MSA, Wrapp D, Chen M, Ngwuta JO, Moin SM, Bai P, Sivasubramanian A, Connor RI, Wright PF, et al. (2018). Infants Infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus Generate Potent Neutralizing Antibodies that Lack Somatic Hypermutation. Immunity 48, 339–349.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham BS (2017). Vaccine development for respiratory syncytial virus. Curr. Opin. Virol 23, 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin PMY (2020). Single-Dose Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Preterm Infants. N. Engl. J. Med 383, 698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotard AL, Shaikh FY, Lee S, Yan D, Teng MN, Plemper RK, Crowe JE Jr., and Moore ML (2012).A stabilized respiratory syncytial virus reverse genetics system amenable to recombination-mediated mutagenesis. Virology 434, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce MG, Bao A, Chen M, Georgiev IS, Ou L, Bylund T, Druz A, Kong WP, Peng D, Rundlet EJ, et al. (2019). Crystal Structure and Immunogenicity of the DS-Cav1-Stabilized Fusion Glycoprotein From Respiratory Syncytial Virus Subtype B. Pathog. Immun 4, 294–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce MG, Wheatley AK, Thomas PV, Chuang GY, Soto C, Bailer RT, Druz A, Georgiev IS, Gillespie RA, Kanekiyo M, et al. ; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2016). Vaccine-Induced Antibodies that Neutralize Group 1 and Group 2 Influenza A Viruses. Cell 166, 609–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong R, Duan H, Sheng Z, Xu K, Acharya P, Chen X, Cheng C, Dingens AS, Gorman J, Sastry M, et al. ; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program (2019). Antibody Lineages with Vaccine-Induced Antigen-Binding Hotspots Develop Broad HIV Neutralization. Cell 178, 567–584.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong R, Li H, Georgiev I, Changela A, Bibollet-Ruche F, Decker JM, Rowland-Jones SL, Jaye A, Guan Y, Lewis GK, et al. (2012). Epitope mapping of broadly neutralizing HIV-2 human monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol 86, 12115–12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krarup A, Truan D, Furmanova-Hollenstein P, Bogaert L, Bouchier P, Bisschop IJM, Widjojoatmodjo MN, Zahn R, Schuitemaker H, McLellan JS, and Langedijk JPM (2015). A highly stable prefusion RSV F vaccine derived from structural analysis of the fusion mechanism. Nat. Commun 6, 8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw A (2018). randomForest. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/randomForest/index.html. [Google Scholar]