Abstract

Most adults with cancer are over 65 years of age, and this cohort is expected to grow exponentially. Older adults have an increased burden of comorbidities and risk of experiencing adverse events on anticancer treatments, including functional decline. Functional impairment is a predictor of increased risk of chemotherapy toxicity and shorter survival in this population. Healthcare professionals caring for older adults with cancer should be familiar with the concept of functional status and its implications because of the significant interplay between function, cancer, anticancer treatments, and patient-reported outcomes. In this narrative review, we provide an overview of functional status among older patients with cancer including predictors, screening, and assessment tools. We also discuss the impact of functional impairment on patient outcomes, and describe the role of individual members of an interprofessional team in addressing functional impairment in this population, including the use of a collaborative approach aiming to preserve function.

Introduction and Definition of Functional Status

The majority of adults with cancer are over 65 years of age, and this cohort is expected to grow exponentially in the next decade [1–2]. Compared to younger adults, older adults are more likely to have comorbidities that increase their risk for adverse effects from anticancer treatments, including functional impairment [3–4]. Functional impairment involves deficits in a range of abilities related to meeting the needs of daily life, including physical, social, spiritual, psychological, and intellectual needs [5–6] and is prevalent among older adults with cancer [7–8]. Moreover, older adults with cancer have a higher prevalence of geriatric syndromes, including functional impairment, frailty, and falls, compared to those without cancer [9]. Frailty, a clinical syndrome, can be defined as a critical depletion of physiological reserve in which even minor stresses may lead to severe and irreversible compromise in functional status [10].

Functional status is a significant concern among older adults with cancer because it is associated with adverse cancer outcomes. While oncology clinical trials frequently use overall and progression-free survival as primary endpoints, functional impairment may be a more meaningful outcome for older adults. This is because it negatively affects quality of life, and older adults with cancer may value preservation of independence more than survival benefits [11–13]. Functional impairment also leads to institutionalization and increased use of healthcare services [14] and it predicts chemotherapy toxicity and shorter survival in older adults with cancer [15–17].

Healthcare professionals caring for older adults with cancer should be familiar with the concept of functional status and its implications. For example, understanding how to evaluate functional status to identify and implement suitable interventions that can optimize the patients’ treatment and/or supportive care trajectory and quality of life [18–20]. The International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) have developed guidelines that recognize functional status as a core domain of geriatric assessment (GA) and endorse its use in determining care for older adults with cancer [21–22]. Furthermore, because of the significant interplay between functional status, cancer, anticancer treatments, and patient-reported outcomes, clinicians should also prioritize communication amongst the interprofessional team involved in caring for older patients. Functional status should be a key priority for healthcare professionals and investigators in the field of geriatric oncology [23].

In this narrative review, we provide an overview of functional status among older patients with cancer, including predictors, screening, and assessment tools, discuss the impact of functional impairment on patient outcomes, and describe the role of individual members of the interprofessional healthcare team in addressing functional status issues in these patients, including the use of a collaborative cancer care approach aiming to preserve function.

Risk factors and predictors of functional status in older adults with cancer

A clearer understanding of the factors associated with functional impairment may improve therapeutic decision-making and inform interventions to optimize functional status. Previous studies of older adults with cancer have evaluated factors associated with functional status trajectories over two or more time points [7, 24–29]. These studies were heterogeneous, and many aimed to predict functional changes after cancer diagnosis, treatment initiation (e.g., surgery, radiation), and treatment completion [7, 25, 27]. Factors associated with functional resilience (e.g., recovery of function between two time points) have also been investigated [7]. These studies found that predictors of functional decline include patient/clinical characteristics, disease characteristics, and treatment-related factors [26–28]. Among patient-related factors, older age, non-white race, unmarried status, lower education status, lack of health insurance, smoking, low physical activity, low chemotherapy preference, and coping strategy are associated with functional decline [26–28, 30]. The role of sex/gender in functional decline following cancer treatment is unclear [25, 27, 31].

Several disease- and treatment-related factors have also been shown to predict functional decline. These include type of malignancy (e.g., lung, colorectal, or breast cancer), disease stage, cancer progression, and type of treatment received [26–27, 30]. Among clinical-related factors, baseline impairment in functional status/physical function, polypharmacy, depression, abnormal nutritional status, cognitive impairment, comorbidities, presence of specific symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, fatigue, weakness), and higher symptom burden are associated with functional decline [25–29, 32–35].

Older adults experiencing frailty can be particularly vulnerable to functional impairments and to the adverse changes in health status [36]. Frail older adults often have multiple chronic conditions, geriatric syndromes, difficulty maintaining functional independence, and increased vulnerability to cancer treatment toxicities [37–38], and they are also more likely to experience a decline in physical functioning over time compared to non-frail adults [39].

Nonetheless, functional impairment may not be easily detectable using routine approaches, which supports the role of a comprehensive geriatric and symptom assessment in older adults with cancer [15, 40–41].

Measurement instruments and tools for functional status assessments

There are two primary ways to measure functional status: patient self-reported measurements (or caregiver/proxy-report) and/or healthcare professional (such as nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and physicians) reported using performance-based measurements [42]. These categories are not mutually exclusive since self-reported tools may also be observations by healthcare professionals, that is, clinician reported.

Most patient self-reported measurements involve asking the patient about their ability to perform specific tasks as part of daily life, whereas performance-based measurement directly assesses the patient’s ability to perform certain tasks and activities. Performance-based measures and self-report measures provide complimentary information. Self-report measures may identify changes at lower levels of function (such as needing help with bathing or dressing) while performance-based measures may identify changes at a higher level of functioning sooner (e.g., changes in function such as slowing down during walking but no disability yet). For example, self-report measures may allow patients to report functional difficulties that clinicians would not detect during an office visit such as “I’m unable to open my pill bottles”. Meanwhile, performance-based measures may identify older adults who look fit for treatment without noticeable disability but have impaired balance. Thus, combining both may be even more informative [43]. Commonly used functional status instruments and performance measures are detailed in both Table 1.

Table 1:

Overview of Commonly Used Functional Status Self-Reported Measurements and Performance Tests in the Older Adult Oncology Setting

| Self-Reported Measurements | Performance Measurements |

|---|---|

| ADL (Katz index) IADL (Lawton scale) Barthel index (any version) Nottingham Extended ADL Scale ADL (subscale of the Medical Outcomes Study Physical Health) IADL (subscale of Older American Resources and Services Scale [OARS]) Medical Outcomes Study Physical Health Questionnaire (any version) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) - Global |

Timed Up and Go test Hand grip strength Short Physical Performance Battery Gait speed, gait assessment Chair stand test 6-minute walk |

Measurement instruments and tools for functional status assessments

The Katz activities of daily living (ADL) index and the Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale are functional status measurements recommended for older adults detailed in the ASCO guidelines [22, 44–45].

Katz index:

The Katz index assesses functional status as a measurement of the patient’s ability to perform ADL independently [44]. ADL include bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding, with patient responses scored in each domain. Functional decline corresponds to impairment in at least one of the six activities over two different time points, which may suggest the need for intervention. As an alternative to the Katz index, clinicians sometimes use the Barthel Activity Index, which is useful in rehabilitation for adults with stroke [46]. This index consists of 10 items, including bowel and bladder continence, feeding, grooming, dressing, transferring, toilet use, mobility, stairs, and bathing.

Lawton scale:

The Lawton scale measures IADL and includes more sophisticated activities [45], such as the ability to use the telephone, shop, cook, do housekeeping and laundry, take medications, use transportation, and manage finances. Adults are scored according to their highest level of functioning in that category, ranging from low function (dependent) to high function (independent). Based on this tool, a patient is deemed dependent when at least one activity is impaired. As an alternative to the Lawton scale, other measures for IADL include the subscale of Older American Resources and Services Scale (OARS) or the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures of physical function and participation in social roles and activities [47–49].

Physician assessments:

Two additional measures are widely used by oncologists to assess the functional status of patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status assigns scores ranging from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead) to assess function [50]. The Karnofsky Performance Status measure assigns scores ranging from 0 (dead) to 100 (perfect health) [51]. Despite their wide use, these tools are poor descriptors of function because functional impairment can occur alongside a good performance status [52].

Performance Measurements

Timed Get Up and Go (TUG):

The Timed Get Up and Go (TUG) is a simple test used to assess fall risk, physical mobility and physical reserve. It requires both static and dynamic balance [53]. With the TUG assessment, the patient is timed while rising from an armed chair, walking 3 meters, turning around, walking back, and sitting back down in the chair [54].

Handgrip strength (HGS):

Handgrip strength (HGS) measures upper extremity strength, which can be relevant information as upper extremity limbs are essential to ADL [55–56]. HGS can be also used as a proxy to assess overall strength and level of frailty [57–59]. Patients squeeze a dynamometer as hard as possible with their dominant hand. The final handgrip strength score, presented in kilograms (kg), is calculated as the average score of three successive attempts with rest in between [60].Clinical thresholds indicating impairment are available from the manufacturer and are specific based on right or left hand, sex, and age. Grip strength is predictive for several adverse outcomes of cancer treatment, including ADL impairment, frailty and mortality [35, 61–63].

Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB):

The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) measures lower extremity function, in particular, static balance, gait, and walking speed, which are important domains of functional ability [64–65]. SPPB includes three timed tasks (walking speed, standing balance, and chair stand tests) [66–67] and can be performed in any clinical environment with a walkway longer than 5 meters so the patient can walk comfortably while being timed. Clinically meaningful changes are defined as 0.1 m/sec. The chair stand test evaluates lower extremity strength while the patient gets up and down from sitting in a chair to full stand 5 times as quickly as possible. The balance test requires patients to hold their feet together, semi-tandem and tandem, each, for 10 seconds to assess fall risk due to balance issues.

Impact of functional impairments on patient outcomes

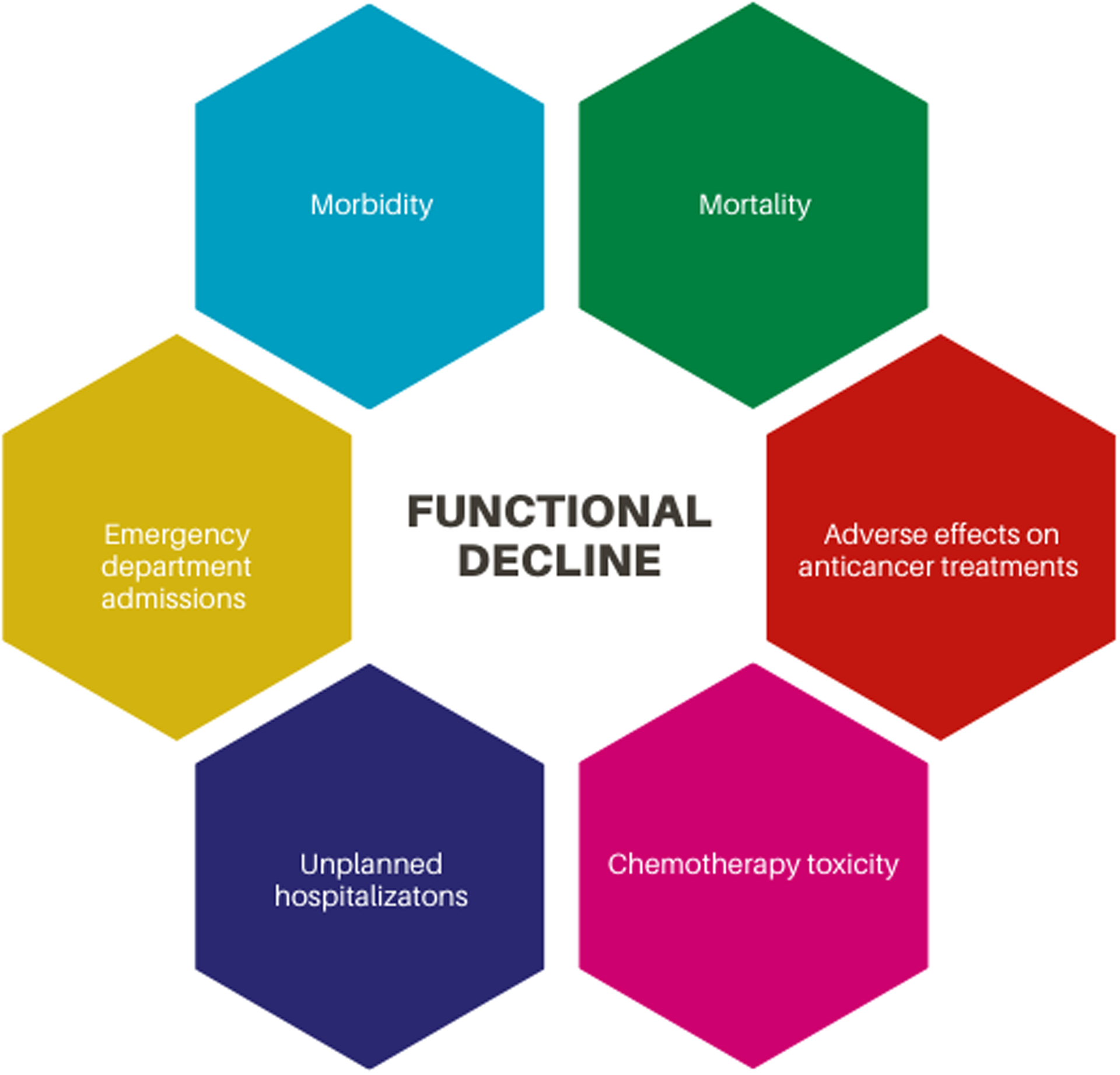

Many older adults with cancer present with functional impairments in ADL (17–19%), and many experience a decline in IADL after receiving cancer treatment (41–59%) [7–8]. Baseline functional status is key to inform therapeutic goals and expectations for cancer management. Functional status changes should be interpreted in the context of older individuals’ needs and goals rather than simply in the framework of their comorbidities. Frequently, impaired function can be the first sign of disease onset or inadequate social support. Monitoring functional status is crucial to adjust discharge plans and is particularly useful to follow the progress of patients with chronic conditions including cancer. The impact of functional decline on outcomes of older patients with cancer is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Impact of functional decline on outcomes of older patients with cancer

Two tools are available to assess the impact of functional status on treatment toxicity including the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) [17] and the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) toxicity calculator [16]. The CRASH tool has shown that limitations in IADL predict the risk of hematological and non-hematological toxicity [17]. Additionally, the CARG toxicity calculator has shown that the presence of falls in the previous 6 months or limitations in walking 1 block predicts the risk of grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity [16]. Aside from toxicity calculators, functional dependence defined as ECOG performance status of 2–4, was shown to increase the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in patients with ovarian cancer aged ≥ 70 [68]. In another study, among older adults with cancer and an ECOG performance status score of 0–1, 9% had restrictions in ADL and 38% had restrictions in IADL which demonstrated that older adults with an ECOG good performance score may have underlying functional impairment [69].

Interprofessional team member roles in assessing and managing functional status

Physicians and advanced practice providers

Physicians caring for older adults with cancer may include the primary oncologist (medical, surgical, or radiation), geriatric oncologist, geriatrician, palliative care physician, or primary care physician. Physicians can obtain information related to functional status directly through clinical encounters or by working closely with other team members (e.g., nurse, advanced practice provider, occupational therapist) trained in collecting these data, depending on local expertise and resources. Geriatric oncologists or geriatricians may assist with more comprehensive functional status assessment and co-manage patients alongside the primary oncologist. Physicians may use functional status information to guide treatment decision-making, assess impact of cancer and treatments, frame conversations with patients and caregivers, determine the need for and place referrals to relevant members of the interprofessional team.

Nurses

Nurses play a central role in the interprofessional team by collecting and synthesizing information related to functional status using the clinical measurement tools described above [70–72]. Nurses actively facilitate care coordination for older adults by working in collaboration with other members of the interprofessional team to implement recommendations that impact cancer care and treatment, which has potential to improve patient functional status [73–74]. Functional limitations uncovered during nurse-led functional assessment can trigger referrals to relevant interprofessionals including but not limited to physical therapy, occupational therapy, and/or social work [74]. Additionally, the nurse’s role includes fostering communication among interdisciplinary team members, which is vital to effective collaboration [70] as often several disciplines may be involved to address a single issue in the care of older adults in the oncology setting. The role of nursing includes bridging relationships between specialists and primary care providers through timely communication and sharing of pertinent information [75–76], and following up with older adults and their caregivers to support implementation of GA-informed recommendations [70].

Rehabilitation specialists

The cancer rehabilitation team may include an occupational therapist, physical therapist, speech and language therapist, physiatrist, rehabilitation psychologist, and rehabilitation nurse, among others [77]. Each team member has a scope of practice and guidelines that direct the evaluation and treatment of functional status and impairment. Patients benefit most when rehabilitation specialists work together to improve their activity participation and functional status [78–79].

Occupational therapists focus on what “occupies” time, in other words, the activities people engage in, from the basic (e.g., dressing, bathing, grooming) to the complex (e.g., working, managing money, medication schedules, higher-level cognitive tasks) [80]. Occupational therapists are trained in evaluation of function as a ‘means to an end’ and as ‘means towards intervention’. In occupational therapy, the evaluation and treatment are commonly structured within the activity itself and can range from evaluation of kitchen use and cooking, to grocery shopping or to basic self-care tasks such as re-training dressing skills; goals focus directly on function, ADL/IADL and engagement in life and social roles (e.g., father, leader, volunteer). Specifically, functional assessments evaluating the motor and cognitive processes observed in functional, daily tasks are the gold standard in occupational therapy evaluations. An occupational interview is used to develop a full profile and activity analysis as part of the plan of care [81]. In treatment, occupational therapists can adapt and create equipment by changing environmental factors in ways that allow for functional independence [82]. Occupational therapist can provide care throughout the cancer continuum from diagnosis through end of life [80, 83–84] thus patients experiencing functional impairment benefit from occupational therapy [85].

Physical therapists examine body systems to determine treatment and are experts in physical mobility and structural needs for movement. Focusing on body function, structures and activity allows physical therapists to evaluate a functional activity or task from a body systems perspective, and treat to the underlying impairment to allow for better function [86].

Speech and language therapists are specialists in production of speech, swallowing, and language. Improving speech production and language can positively affect IADL. For individuals with head and neck cancer or those on radiation treatment, speech and language therapists are critical in assisting, preventing, and/or improving structural issues related to jaw mobility (e.g., lockjaw) swallowing, and lymphedema. Furthermore, some speech and language therapists are trained in cognitive rehabilitation and can evaluate and treat cancer-related cognitive decline, especially as it relates to language and speech production difficulty (e.g., word recall) [87–88].

Prehabilitation, the provision of rehabilitation services at diagnosis, typically before surgery, can also prevent or limit the impact of treatment and improve functional recovery [89]. Individuals with lung, colorectal, and breast cancer who underwent prehabilitation prior to surgery had improved functional mobility for ADL/IADL and decreased hospital length of stay [90–93]. Prehabilitation has historically focused only on the period of diagnosis and primary therapy, instead of focusing on a prospective, longitudinal period throughout the entire cancer care continuum. However, researchers have called for future studies to examine the impact of a prospective surveillance rehabilitation model [77, 79]. This approach holds potential to address declines in function earlier when they are easier to treat [79].

Pharmacists

Functional impairment can affect the way patients are able to administer and manage their medications. One of the items on the Lawton scale for IADL includes the patient’s ability to take medications, which relies to some degree on both cognition and physical function [45]. In cases where cognitive impairment and functional impairment exists, the patient is not able to read and understand medication directions for safe self-administration, not be able to adhere to complex oral chemotherapy directions (e.g., take once daily for 21 days, then 7 days off), and not able to understand complex medication-related adverse events, which requires self-monitoring and reporting. In cases where functional impairment exists, the patient may not be able to independently open child-proof medication containers or self-administer injectable medications such as insulin.

Older adults with cancer are at a high risk of polypharmacy, with many meeting the definition for polypharmacy prior to the initiation of anticancer therapy [94–103]. The relationship between polypharmacy, functional impairment, and frailty has been closely examined and reported in the geriatric and geriatric oncology literature [27, 104–107]. Potential underlying mechanisms connecting polypharmacy to functional decline are summarized in Table 2 [104].

Table 2.

Proposed Mechanisms to Elucidate the Impact of Polypharmacy on Functional Status

| Factors | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Age-related regression of function reserve affects drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics | Reduced physiologic resilience and altered drug metabolism and/or drug clearance increases susceptibility to adverse drug reactions. Medication dose-adjustments may be warranted, if applicable. |

| Increased number of medical conditions increases the risk for drug-disease interactions and/or drug-geriatric syndrome interactions | A drug-disease interaction is an event in which a drug intended for therapeutic use causes harmful effects due to a comorbid disease, condition or syndrome (e.g., using diphenhydramine for seasonal allergies in a patient with cognitive impairment or a history of falls). |

| Increased number of medications increases the risk for drug-related toxicities or drug-drug interactions | Increased number of medications may lead to cumulative drug toxicity. The risk for drug-drug interactions approach 100% when 8 or more medications are used concurrently. |

| Use of medications in which the risk outweighs the benefit | Benzodiazepines and anticholinergic drugs (e.g., oxybutynin, amitriptyline) may interfere with memory, alertness, and orientation, leading to delirium, falls/fractures, and other adverse reactions. |

Pharmacists play a particularly important role in the inter-professional, patient-centered cancer care team by addressing polypharmacy and its impact on functional impairment. Oncology pharmacists have training and expertise to optimize outcomes by providing evidence-based, patient-centered medication therapy as part of team-based care [108]. Because polypharmacy may be a potentially modifiable risk factor for functional decline it is imperative that pharmacists and other members of the cancer care team can screen for polypharmacy using validated tools [109–111] in order to identify opportunities to deprescribe high-risk medications and/or unnecessary medications. Pharmacist-led pilot studies have proven to be effective at reducing polypharmacy [112–116], yet a critical need remains for randomized controlled trials that demonstrate successful and scalable medication interventions that preserve, reverse or delay functional impairment and frailty in older adults with cancer.

Dietitians

Malnutrition is a common but often overlooked side effect of cancer and anticancer treatments, affecting up to 80% of patients depending on the tumor type/stage and causing nearly one in five cancer-related deaths [117]. The malnutrition results from systemic inflammation that causes anorexia, tissue breakdown, and loss of muscle mass and strength (sarcopenia) and that can result in significant loss of body weight, alterations in body composition, and functional decline [118]. Furthermore, older adults with cancer may be malnourished before a diagnosis and treatment plan are established. Therefore, it is critical to incorporate a screening process utilizing the appropriate tools to identify malnutrition early in patients’ treatment. According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the 2-item Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), which measures appetite and recent unintentional weight loss, is valid and reliable for identifying malnutrition risks in adult oncology patients in the ambulatory/outpatient setting [119].

Any patient determined to be at risk of malnutrition should be referred to an oncology dietitian and evaluated for possible interventions. To diagnose malnutrition, at least 2 of the following 6 clinical characteristics must be present: insufficient energy intake, weight loss, muscle mass wasting (sarcopenia), body fat depletion, fluid accumulation, and grip strength [120]. If a patient has been diagnosed with malnutrition, an immediate and complete review of nutritional impact symptoms by a dietitian will help determine cause. These include loss/absence of appetite (anorexia), episodes of nausea and/or emesis, diarrhea and/or constipation, difficulty with chewing and swallowing (odynophagia, dysphagia), oral health, taste alterations (dysgeusia), early satiety, and fatigue. Any social challenges, including difficulty obtaining food and physical inability to cook meals, should be explored.

Dietitians can provide input throughout the entire cancer care continuum. Parenteral and enteral feeding and oral nutritional supplements may be considered. Dietitians may also introduce antiemetics, appetite stimulators, and other appropriate medications. An inter-professional, shared-care approach including dietitians may significantly improve the detection and management of malnutrition among older adults with cancer. Improving gait speed and chair stand, in combination with nutritional intervention, could be a target for interventions to improve function and prevent or improve malnutrition-related negative health outcomes.

Caregivers

As cancer care has moved predominantly to the ambulatory/outpatient care setting [121], caregivers (e.g., family or friends providing unpaid care) are often the main providers of day-to-day support to older adults with cancer [122]. This support is influenced by older adults’ prognosis, disease severity, and goals of care and may include direct care, assistance with ADL/IADL, case management, emotional support, companionship, and medication supervision, all of which help to recover and/or maintain functional ability [123–125]. Functional independence of older adults with cancer is a major predictor of their caregivers’ quality of life, with more functional impairment associated with higher caregiver burden [126–127]. Informal and formal interventions such as home health care and community support may improve outcomes for both older adults with cancer and their caregivers [128–129]. Caregivers can also turn to navigators and spiritual care specialists for meaningful support.

Navigators

Patient navigators have become increasingly relevant in oncology, especially for older adults and their caregivers facing challenges associated with anticancer treatments and with identifying and accessing age-appropriate services to optimize care [130]. Registered nurses are most suited for the role, although social workers, or a trained peer or lay navigators may also take over this role [131]. Navigators are expected to address a high level of complexity, including using knowledge of frailty and the aging process, being trained in assessing and managing chronic conditions, as well as being embedded in an interdisciplinary team [132]. An important task for navigators is linking adults to services that address functional decline [133–134]. These might include referral to occupational therapy, social work, and home nursing support.

Spiritual Care Specialists

Providing spiritual support is critical for the overall well-being and functioning of older adults. Participation in religious activity predicts higher self-rated health [135], better physical functioning [136–137], and less distress [138]. Furthermore, spiritual beliefs may help older adults cope with the impact of the disease on their physical and emotional functioning [136, 139]. Medical and psychosocial support services may support positive spiritual coping efforts, identify individuals for whom negative spiritual coping or distress is present, and assist them in resolving any underlying distress [140–141].

Conclusions

Preservation of functional status is the cornerstone of geriatric care and serves as an indicator of general well-being. As summarized in this review, a decline in function increases the risk of healthcare utilization, worsens quality of life, reduces independence, and increases risk of mortality. To improve health among older adults with cancer, the interprofessional team should proactively monitor their functional abilities and, when needed, arrange for therapeutic interventions that support their functioning and overall well-being.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jennifer Fisher Wilson for her assistance with editing this manuscript.

Conflict of interests

Dr. Puts is supported as a Canada Research Chair in the Care for Frail Older Adults. Dr. Battisti has received travel grants from Genomic Health and Pfizer and speaker fees from Pfizer. Dr. Loh is supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institute of Health (K99CA237744) and Wilmot Research Fellowship Award and has served as a consultant to Pfizer and Seattle Genetics. Dr. Pergolotti receives a salary from ReVital Cancer Rehabilitation, Select Medical, Inc.

References

- 1.Delivorias A and SG, EU Demographic Indicators: Situation, Trends And Potential Challenges. 2015, Europe’s Demographic Future Berlin Institut: https://epthinktank.eu/2015/03/20/eu-demographic-indicators-situation-trends-and-potential-challenges/. Accessed February 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancik R, Ries LA. Cancer in older persons: an international issue in an aging world. Seminars in oncology. 2004; 31(2):128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bultz BD, Carlson LE. Emotional distress: the sixth vital sign—future directions in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2006;15(2):93–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, De Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, Van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Annals of oncology. 2007;18(9):1437–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. 2001: Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TJ. Concept analysis of functional status. International journal of nursing studies. 2004; 41(4): 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurria A, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Allred JB, Cohen HJ, Arsenyan A, et al. Functional decline and resilience in older women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(5):920–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serraino D, Fratino L, Zagonel V. Prevalence of functional disability among elderly patients with cancer. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2001;39(3):269–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohile SG, Fan L, Reeve E, Jean-Pierre P, Mustian K, Peppone L, Janelsins M, Morrow G, Hall W, Dale W. Association of cancer with geriatric syndromes in older Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(11):1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huisingh-Scheetz M, Walston J. How should older adults with cancer be evaluated for frailty?. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(1):8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman SM, Hurria A, Jacobsen PB. Geriatric Oncology: An Overview. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(24):2521–2522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pergolotti M, Deal AM, Williams GR, Bryant AL, Bensen JT, Muss HB, Reeve BB. Activities, function, and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of older adults with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017; 8(4): 249–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams GR, Dunham L, Chang Y, Deal AM, Pergolotti M, et al. Geriatric Assessment Predicts Hospitalization Frequency and Long-Term Care Use in Older Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of oncology practice. 2019; 15(5): e399–e409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Cleave JH, Smith-Howell E, Naylor MD. Achieving a high-quality cancer care delivery system for older adults: Innovative models of care. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2016; 32(2):122–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, Owusu C, Klepin HD, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(25):3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, Lyman GH, Brown RH, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magnuson A, Lemelman T, Pandya C, Goodman M, Noel M, et al. Geriatric assessment with management intervention in older adults with cancer: a randomized pilot study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26 (2):605–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenis C, Baitar A, Decoster L, De Grève J, Lobelle JP, et al. The added value of geriatric screening and assessment for predicting overall survival in older patients with cancer. Cancer. 2018; 124(18):3753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Springall E, et al. Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(15):1134–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology. 2014;32(24):2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohile SG, et al. , Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline for Geriatric Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018; 36(22): 23264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puts MT, Tapscott B, Fitch M, Howell D, Monette J, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing older adults’ decision to accept or decline cancer treatment. Cancer treatment reviews. 2015;41(2):197–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajra A, McCall L, Muss HB, Cohen HJ, Jatoi A, et al. The preference to receive chemotherapy and cancer-related outcomes in older adults with breast cancer CALGB 49907 (Alliance). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2018;9(3):221–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amemiya T, Oda K, Ando M, Kawamura T, Kitagawa Y, et al. Activities of daily living and quality of life of elderly patients after elective surgery for gastric and colorectal cancers. Annals of surgery. 2007;246(2):222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenis C, Decoster L, Bastin J, Bode H, Van Puyvelde K, et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: a multicenter prospective study. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(3):196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Abbema D, van Vuuren A, van den Berkmortel F et al. Functional status decline in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer after cancer treatment: A prospective cohort study. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017; 8: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Decoster L, Vanacker L, Kenis C et al. Relevance of Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017; 16: e221–e229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppe S, Rainfray M, Fonck M et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31: 3877–3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bussiere M, Hopman W, Day A et al. Indicators of functional status for primary malignant brain tumour patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2005; 32: 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrick JL, Reeve BB, Kucharska-Newton AM et al. Functional status declines among cancer survivors: trajectory and contributing factors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014; 5: 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh R, Ansinelli H, Katz H, Jafri H, Gress T, et al. Factors Associated with Functional Decline in Elderly Female Breast Cancer Patients in Appalachia. Cureus. 2018;10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong ML, Paul SM, Mastick J et al. Characteristics Associated With Physical Function Trajectories in Older Adults With Cancer During Chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018; 56: 678–688.e671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galvin A, Helmer C, Coureau G, Amadeo B, Rainfray M, et al. Determinants of functional decline in older adults experiencing cancer (the INCAPAC study). Journal of geriatric oncology. 2019;10(6):913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owusu C, Margevicius S, Schluchter M, Koroukian SM, Berger NA. Short Physical Performance Battery, usual gait speed, grip strength and Vulnerable Elders Survey each predict functional decline among older women with breast cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(5):356–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. The lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritchie CS, Kvale E, Fisch MJ. Multimorbidity: an issue of growing importance for oncologists. Journal of oncology practice. 2011;7(6):371–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012. October;60(10):E1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirkhus L, Šaltytė Benth J, Grønberg BH, Hjermstad MJ, Rostoft S, Harneshaug M, Selbæk G, Wyller TB, Jordhøy MS. Frailty identified by geriatric assessment is associated with poor functioning, high symptom burden and increased risk of physical decline in older cancer adults: Prospective observational study. Palliative medicine. 2019;33(3):312–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohile SG, Xian Y, Dale W, Fisher SG, Rodin M, et al. Association of a cancer diagnosis with vulnerability and frailty in older Medicare beneficiaries. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101(17):1206–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohile SG, Epstein RM, Hurria A, Heckler CE, Canin B, et al. Communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment: a cluster-randomized clinical trial from the National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program. JAMA oncology. 2020;6(2):196–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Overcash J Integrating geriatrics into oncology ambulatory care clinics. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2015;19(4):e80–e86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kasper JD, Chan KS, Freedman VA. Measuring physical capacity: an assessment of a composite measure using self-report and performance-based items. Journal of aging and health. 2017;29(2):289–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wade DT, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? International disability studies. 1988;10(2):64–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fillenbaum GG, Smyer MA. The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. Journal of Gerontology. 1981;36(4):428–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jensen RE, Potosky AL, Reeve BB, Hahn E, Cella D, Fries J, Smith AW, Keegan TH, Wu XC, Paddock L, Moinpour CM. Validation of the PROMIS physical function measures in a diverse US population-based cohort of cancer patients. Quality of life research. 2015;24(10):2333–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hahn EA, Kallen MA, Jensen RE, et al. Measuring social function in diverse cancer populations: Evaluation of measurement equivalence of the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities short form. Psychol Test Assess Model. 2016;58(2):403–421 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American journal of clinical oncology. 1982. December 1;5(6):649–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH: The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Edited by MacLeod CM. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949:191–205. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jolly TA, Deal AM, Nyrop KA, Williams GR, Pergolotti M, Wood WA, Alston SM, Gordon BB, Dixon SA, Moore SG, Taylor WC. Geriatric assessment-identified deficits in older cancer patients with normal performance status. The oncologist. 2015;20(4):379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1991;39(2):142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pondal M, del Ser T. Normative data and determinants for the timed “up and go” test in a population-based sample of elderly individuals without gait disturbances. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 2008;31(2):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lycke M, Ketelaars L, Martens E, Lefebvre T, Pottel H, Van Eygen K, Cool L, Pottel L, Kenis C, Schofield P, Boterberg T. The added value of an assessment of the patient’s hand grip strength to the comprehensive geriatric assessment in G8-abnormal older patients with cancer in routine practice. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2019;10(6):931–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taekema DG, Gussekloo J, Maier AB, Westendorp RGJ, de Craen AJM. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age and Ageing. 2010;39(3):331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee L, Patel T, Costa A, Bryce E, Hillier LM, Slonim K, Hunter SW, Heckman G, Molnar F. Screening for frailty in primary care: accuracy of gait speed and hand-grip strength. Canadian Family Physician. 2017;63(1):e51–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Velghe A, De Buyser S, Noens L, Demuynck R, Petrovic M. Hand grip strength as a screening tool for frailty in older patients with haematological malignancies. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2016;71(4):227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pamoukdjian F, Paillaud E, Zelek L, Laurent M, Lévy V, Landre T, Sebbane G. Measurement of gait speed in older adults to identify complications associated with frailty: A systematic review. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2015;6(6):484–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mathiowetz V, Rennells C, Donahoe L. Effect of elbow position on grip and key pinch strength. The Journal of hand surgery. 1985;10(5):694–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bailey C, Asher A, Kim S, Shinde A, & Lill M (2018). Evaluating Hand Grip Strength Prior to Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation as a Predictor of Patient Outcomes. Rehabilitation Oncology. 2018; 36(3):172–179. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Velghe A, De Buyser S, Noens L, Demuynck R, Petrovic M. Hand grip strength as a screening tool for frailty in older patients with haematological malignancies. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2016;71(4):227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Y, Wang W, Liu T, Zhang D. Association of grip strength with risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer in community-dwelling populations: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2017;18(6):551–e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karpman C, Benzo R. Gait speed as a measure of functional status in COPD patients. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2014;9:1315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Middleton A, Fritz SL, Lusardi M. Walking speed: the functional vital sign. Journal of aging and physical activity. 2015;23(2):314–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pavasini R, Guralnik J, Brown JC, di Bari M, Cesari M, Landi F, et al. Short Physical Performance Battery and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC medicine. 2016;14(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of gerontology. 1994;49(2):M85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S, Provencal J, Weber B, Jacquin JP, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a GINECO study. Annals of oncology. 2005;16(11):1795–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA, Venturino A, Gianni W, Vercelli M, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. Journal of clinical oncology. 2002; 20(2):494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Overcash J, Momeyer MA. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Caring for the Older Person with Cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2017;33(4):440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.National Council of State Boards of Nursing. Nurse practice act, rules & regulations https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm (2017)

- 72.Brant J, Wickham R. Statement on the Scope and Standards of Oncology Nursing Practice: Generalist and Advanced Practice. Oncology Nursing Society; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Overcash J Geriatric oncology nursing: beyond standard care. InCancer and Aging 2013. (Vol. 38, pp. 139–145). Karger Publishers. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Overcash J Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: Interprofessional Team Recommendations for Older Adult Women With Breast Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Easley J, Miedema B, Carroll JC, Manca DP, O’Brien MA, Webster F, Grunfeld E. Coordination of cancer care between family physicians and cancer specialists: importance of communication. Canadian Family Physician. 2016;62(10):e608–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Camicia M, Chamberlain B, Finnie RR, Nalle M, Lindeke LL, et al. The value of nursing care coordination: A white paper of the American Nurses Association. 2013;61(6):490–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alfano CM, Pergolotti M. Next-Generation Cancer Rehabilitation: A Giant Step Forward for Patient Care. Rehabilitation nursing. 2018;43(4):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pergolotti M, Covington KR, Lightner AN, Bertram J, Thess M, Sharp JL, Spraker MB, Williams GR, Manning P. Outpatient cancer rehabilitation to improve patient reported and objective measures of function. 2020.

- 79.Pergolotti M, Deal AM, Williams GR, Bryant AL, McCarthy L, Nyrop KA, Covington KR, Reeve BB, Basch E, Muss HB. Older adults with cancer: a randomized controlled trial of occupational and physical therapy. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(5):953–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lyons KD, Newman R, Adachi-Mejia AM, Whipple J, Hegel MT. Content analysis of a participant-directed intervention to optimize activity engagement of older adult cancer survivors. OTJR: occupation, participation and health. 2018;38(1):38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trombly C Anticipating the future: Assessment of occupational function. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1993;47(3):253–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pergolotti M, Williams GR, Campbell C, Munoz LA, Muss HB. Occupational therapy for adults with cancer: why it matters. The oncologist. 2016;21(3):314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peoples H, Brandt Å, Wæhrens EE, la Cour K. Managing occupations in everyday life for people with advanced cancer living at home. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2017;24(1):57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Badger S, Macleod R, Honey A. “It’s not about treatment, it’s how to improve your life”: The lived experience of occupational therapy in palliative care. Palliative & supportive care. 2016;14(3):225–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rodríguez EJ, Galve MI, Hernández JJ. Effectiveness of an Occupational Therapy Program on Cancer Patients with Dyspnea: Randomized Trial. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics. 2020;38(1):43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pergolotti M, Lyons KD, Williams GR. Moving beyond symptom management towards cancer rehabilitation for older adults: Answering the 5W’s. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2018;9(6):543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clarke P, Radford K, Coffey M, Stewart M. Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2016;130(S2):S176–S180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nguyen N-TA, Ringash J. Head and neck cancer survivorship care: a review of the current guidelines and remaining unmet needs. Current treatment options in oncology. 2018;19(8):44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carli F, Silver JK, Feldman LS, et al. Surgical prehabilitation in patients with cancer: state-of-the-science and recommendations for future research from a panel of subject matter experts. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics. 2017;28(1):49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mayo NE, Feldman L, Scott S, et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2011;150(3):505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Minnella EM, Bousquet-Dion G, Awasthi R, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Carli F. Multimodal prehabilitation improves functional capacity before and after colorectal surgery for cancer: a five-year research experience. Acta Oncologica. 2017;56(2):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Minnella EM, Awasthi R, Loiselle SE, Agnihotram RV, Ferri LE, et al. Effect of exercise and nutrition prehabilitation on functional capacity in esophagogastric cancer surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA surgery. 2018;153(12):1081–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Piraux E, Caty G, Reychler G. Effects of preoperative combined aerobic and resistance exercise training in cancer patients undergoing tumour resection surgery: A systematic review of randomised trials. Surgical oncology. 2018;27(3):584–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharma M, Loh KP, Nightingale G, Mohile SG, Holmes HM. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use in geriatric oncology. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(5):346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prithviraj GK, Koroukian S,Margevicius S, et al. Patient characteristics associated with polypharmacy and inappropriate prescribing of medications among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nightingale G, Hajjar E, Swartz K, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led medication assessment used to identify prevalence of and associations with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among ambulatory senior adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1453–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Goh I, Lai O, Chew L. Prevalence and risk of polypharmacy among elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in ambulatory oncology setting. Current oncology reports. 2018;20(5):38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karuturi MS, Holmes HM, Lei X, Johnson M, Barcenas CH, Cantor SB, Gallick GE, Bast RC Jr, Giordano SH. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients with breast and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(14):3000–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Leger DY, Moreau S, Signol N, Fargeas JB, Picat MA, Penot A, Abraham J, Laroche ML, Bordessoule D. Polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications and drug-drug interactions in geriatric patients with hematologic malignancy: Observational single-center study of 122 patients. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2018;9(1):60–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lund JL, Sanoff HK, Hinton SP, Muss HB, Pate V, Stürmer T. Potential Medication-Related Problems in Older Breast, Colon, and Lung Cancer Patients in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2018;27(1):41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jørgensen TL, Herrstedt J. The influence of polypharmacy, potentially inappropriate medications, and drug interactions on treatment completion and prognosis in older patients with ovarian cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2020;11(4):593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Loveren FM, Imholz AL, van’t Riet E, Taxis K, Jansman FG. Prevalence and follow-up of potentially inappropriate medication and potentially omitted medication in older patients with cancer–The PIM POM study. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2020. July 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sweiss K, Calip GS, Wirth S, Rondelli D, Patel P. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use is highly prevalent in multiple myeloma patients and is improved by a collaborative physician–pharmacist clinic. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice. 2020;26(3):536–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Peron EP, Gray SL, Hanlon JT. Medication use and functional status decline in older adults: a narrative review. The American journal of geriatric pharmacotherapy. 2011;9(6):378–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gutiérrez-Valencia M, Izquierdo M, Cesari M, et al. The relationship between frailty and polypharmacy in older people: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018; 84: 1432–1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mohamed MPA, Xu H, et al. Association of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications with physical function in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Multinational and multidisciplinary conference; June 21–23; San Francisco, California. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pamoukdjian F, Aparicio T, Zelek L, Boubaya M, Caillet P, et al. Impaired mobility, depressed mood, cognitive impairment and polypharmacy are independently associated with disability in older cancer outpatients: The prospective Physical Frailty in Elderly Cancer patients (PF-EC) cohort study. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(3):190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. Journal of oncology practice. 2014;10(3):e142–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel, Fick DM, Semla TP, Steinman M, Beizer J, Brandt N, Dombrowski R, DuBeau CE, Pezzullo L, Epplin JJ, Flanagan N. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Samsa GP, Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Weinberger M, Clipp EC, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, Landsman PB, Cohen HJ. A summated score for the medication appropriateness index: development and assessment of clinimetric properties including content validity. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1994;47(8):891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.O’Mahony D, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Hamilton H, Barry P, O’Connor M, Kennedy J. STOPP & START criteria: a new approach to detecting potentially inappropriate prescribing in old age. European Geriatric Medicine. 2010;1(1):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Whitman A, DeGregory K, Morris A, Mohile S, Ramsdale E. Pharmacist-led medication assessment and deprescribing intervention for older adults with cancer and polypharmacy: a pilot study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2018;26(12):4105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Deliens C, Deliens G, et al. Drugs prescribed for patients hospitalized in a geriatric oncology unit: potentially inappropriate medications and impact of a clinical pharmacist. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nightingale G, Hajjar E, et al. Implementing a pharmacist-led, individualized medication assessment and planning (iMaP) intervention to reduce medication related problems among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yeoh TT, Tay XY, Si P, Chew L. Drug-related problems in elderly patients with cancer receiving outpatient chemotherapy. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2015;6(4):280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nipp RD, Ruddy M, Fuh CX, Zangardi ML, Chio C, Kim EB, Li BK, Long Y, Blouin GC, Lage D, Ryan DP. Pilot Randomized Trial of a Pharmacy Intervention for Older Adults with Cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Malnutrition ‘almost epidemic’ among patients with advanced cancer. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.healio.com/news/hematology-oncology/20170613/malnutrition-almost-epidemic-among-patients-with-advanced-cancer

- 118.Arends J, Baracos V, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, Calder PC, Deutz NE, Erickson N, Laviano A, Lisanti MP, Lobo DN, McMillan DC. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clinical Nutrition. 2017;36(5):1187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.EAL. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.andeal.org/template.cfm?key=4185

- 120.White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M, Group AM, Force AM, of Directors AB. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(5):730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kolodziej M, Hoverman JR, Garey JS, et al. Benchmarks for value in cancer care: an analysis of a large commercial population. Journal of oncology practice. 2011;7(5):301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schulz R, Eden J. Families caring for an aging America. . Washington, D. C.: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.National Cancer Institute. Family Caregivers in Cancer: Roles and Challenges (PDQ®). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Satariano WA, Ragheb NE, Branch LG, Swanson GM. Difficulties in physical functioning reported by middle-aged and elderly women with breast cancer: a case-control comparison. Journal of gerontology. 1990;45(1):M3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Loss of physical functioning among geriatric cancer patients: relationships to cancer site, treatment, comorbidity and age. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 1997;33(14):2352–2358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hsu T, Loscalzo M, Ramani R, et al. Factors associated with high burden in caregivers of older adults with cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(18):2927–2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Germain V, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Marilier S, et al. Management of elderly patients suffering from cancer: Assessment of perceived burden and of quality of life of primary caregivers. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2017;8(3):220–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WY, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, Miller KD, Alcaraz KI, Cannady RS, Wender RC, Brawley OW. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019;69(1):35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Cantril C, Haylock PJ. Patient navigation in the oncology care setting. Seminars in oncology nursing. 2013;29(2):76–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Guide to implementating navigation. Toronto, ON: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lynch MP, Marcone D, Kagan SH. Developing a multidisciplinary geriatric oncology program in a community cancer center. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2007;11(6):929–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Willis A, Reed E, Pratt-Chapman M, et al. Development of a Framework for Patient Navigation: Delineating Roles Across Navigator Types. Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. 2013;4(6). [Google Scholar]

- 134.Cook S, Fillion L, Fitch M, et al. Core areas of practice and associated competencies for nurses working as professional cancer navigators. Canadian oncology nursing journal = Revue canadienne de nursing oncologique. 2013;23(1):44–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, Crammer C, Zhou ES. Individual and dyadic relations between spiritual well-being and quality of life among cancer survivors and their spousal caregivers. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(7):762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P. Religion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(4):554–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Campbell JD, Yoon DP, Johnstone B. Determining relationships between physical health and spiritual experience, religious practices, and congregational support in a heterogeneous medical sample. Journal of religion and health. 2010;49(1):3–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Jim HS, Andersen BL. Meaning in life mediates the relationship between social and physical functioning and distress in cancer survivors. British journal of health psychology. 2007;12(Pt 3):363–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Magnuson A, Wallace J, Canin B, et al. Shared Goal Setting in Team-Based Geriatric Oncology. Journal of oncology practice. 2016;12(11):1115–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Balducci L The Older Cancer Patient: Religious and Spiritual Dimensions. In: Extermann M, ed. Geriatric Oncology. Cham: Springer; 2018:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Glazier SR, Schuman J, Keltz E, Vally A, Glazier RH. Taking the next steps in goal ascertainment: a prospective study of patient, team, and family perspectives using a comprehensive standardized menu in a geriatric assessment and treatment unit. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(2):284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]